In a context of aging populations, ensuring the financial stability of a pay-as-you-go pension system can be realized through three main options: increasing the contribution rates, lowering benefit amounts or extending the working life duration. In France, as in many countries, the third option has prevailed. During the last 15 years, several reforms have aimed at increasing the average retirement age. At the same time, the employment rate of older workers has achieved a steady and significant growth, with a sharp acceleration in recent years (Minni, Reference Minni2015). However, the relative contributions of the different reforms to this evolution, as well as underlying labor supply behaviors, remain unknown.

In this paper, we focus on one of the most emblematic recent reforms, the increase from 60 to 62 of the statutory eligibility age (SEA), the minimum age at which pension benefits can be claimed.Footnote 1 As many countries have implemented similar reforms in recent years, there is a growing body of literature evaluating their effects on the labor force participation of older workers. In theory, an increase in the SEA can have different effects.

First, this increase is likely to have a strong impact on employment. Due to credit constraints, individuals may not be able to smooth their consumption without delaying their exit from the labor force. It may also generate a negative wealth effect, as the maximum duration of benefits receipt decreases. Overall, individuals in employment may have a strong incentive to postpone retirement when the SEA increases. This is confirmed by recent evaluations of the employment effects of increases in the SEA, using a differences-in-differences approach (Staubli and Zweimüller (Reference Staubli and Zweimüller2013) for Austria, Atalay and Barrett (Reference Atalay and Barrett2015) for Australia, Cribb et al. (Reference Cribb, Emmerson and Tetlow2016) for the UK and Dubois and Koubi (Reference Dubois and Koubi2017) for France). The estimated effects on the employment rate vary from 6.5 to 20 percentage points, for a change of 1 or 2 years in the SEA. Manoli and Weber (Reference Manoli and Weber2016) extend the evaluation of the Austrian reform, using a regression kink design approach, and find that a 1 year increase in the SEA leads to a 0.4 year increase in the retirement age. Finally, Vestad (Reference Vestad2013) studies the effect of a symmetric reform in Norway, the decrease in the SEA from 64 to 62, and finds large employment effects (−33pp).

Besides an employment effect, increasing the SEA can also have an impact on other public insurance schemes, such as unemployment insurance (UI), disability insurance (DI) or sickpay insurance. These substitution effects may be of two different types. First, individuals already out of employment may not react to the incentives generated by the reform, and just stay longer on the bridge between employment and retirement. The decrease in retirement spending will then be counterbalanced by the increase in spending in other insurance schemes. Second, indirect substitution effects can also occur: when access to a given scheme is restricted, the relative ‘value’ of alternative routes increases and some individuals may manage to fall back on them. Therefore, workers who expected to retire at 60 may use alternative schemes to fill the gap until the new SEA. These substitution effects are rarely taken into account in the evaluation of pension reforms. Among papers studying changes in the SEA, only Staubli and Zweimüller (Reference Staubli and Zweimüller2013) and Vestad (Reference Vestad2013) thoroughly estimate the effect of the reform on alternative routes to retirement. They both find evidence of substitution between retirement and unemployment or sick leave. The magnitude of the effect, however, differs substantially: substitution effects equal the employment effect in the case of Staubli and Zweimüller (Reference Staubli and Zweimüller2013), and represent one-third of the effect in Vestad (Reference Vestad2013). More generally, substitution effects between public insurance schemes have been largely documented in the literature. For example, Duggan et al. (Reference Duggan, Singleton and Song2007) show that the decreasing generosity of social security benefits increases the take up of DI (between 0.6% and 0.9%). Karlström et al. (Reference Karlström, Palme and Svensson2008) study the effect of a tightening of the eligibility rules for DI among older workers in Sweden. They find no impact on employment, but a strong substitution effect into alternative routes such as unemployment or sickleave insurance systems.

In this paper, we investigate these two potential effects by studying the immediate impact of the 2010 reform of the French pension system on the labor force participation of older workers. This reform increased the SEA from 60 to 62, but we carry out a short-term evaluation focusing on the 60–61 increase. We implement a differences-in-differences approach, similar to the one used in the literature, and which allows a comparison of trajectories from work to retirement between cohorts facing different SEAs. To do so, we use the administrative records of the public pension scheme for wage earners of the private sector (Caisse nationale d'assuance vieillesse – Cnav). They provide complete records of the working trajectories that are required to isolate the effect of the increase in the SEA from other contemporaneous reforms of the pension system. Since these records contain information on periods spent in different public insurance schemes (unemployment, disability, sickness, pension), we are able to make a comprehensive assessment of the effect of the reform, taking into account potential substitution effects between different schemes.

We make the following contributions to the literature. We first make a precise evaluation of the French case. We expect the effect of the reform to be particularly strong for two reasons. First, as the French pension system offers high replacement rate at the SEA for individuals with a full career duration, the pre-reform share of individuals retiring exactly at the SEA is high compared with other countries, suggesting large employment effects of its increase. Second, as a large share of the population has already exited the labor force before the SEA, we expect large substitution effects of the reform toward other insurance schemes. We indeed find sizable effects on employment and strong substitution effects. The employment effect is important (+21pp, the highest found in the literature), but represents only 40% of the decrease in retirement rate induced by the reforms. The remaining part is due to crowding out from retirement to alternative public schemes, mainly UI. We then extend this analysis of substitution effects in two directions. In order to uncover the underlying mechanisms, we first estimate the effect of the reform conditional on the pre-SEA labor market status. We show that employment effects are concentrated on individuals who are still employed when reaching the SEA, and that substitution effects are driven by individuals already out of the labor force, rather than by direct substitution from work to alternative schemes. Second, we estimate the effect of the reforms on subpopulations and show that the employment effects are much stronger for individuals with strong pension incentives to retire as soon as possible, and much lower for individuals in poor health.

The paper proceeds as follows. We present the French institutional context regarding retirement and other insurance schemes in the following section. We describe the data and our identification strategy. Then, we present the results and conclude.

1. Institutionnal setting

1.1 Overview of the French pension system

In this section, we briefly sketch the French pension system and its main rules for pension benefits computation, focusing on the age parameters of the system.Footnote 2

The main public pension system in France is very comprehensive, providing benefits amounting to roughly 14% of GDP (COR, 2015). In this paper, we focus on the Régime Général (RG), the main scheme for wage earners of the private sector. It is the most important public pension scheme in France, covering more than two-thirds of the working population. Together with its complementary point-based public second pillar, it provides the main source of income during retirement, with a median replacement rate of last earnings of 75% for continuous careers.

In most pension systems, the computation of benefits depends on two key parameters: the minimum age at which one claim a pension (SEA); and the age at which workers are eligible for full pension benefits – usually referred to as the normal retirement age (NRA). The main peculiarity of the French pension system is that both the minimum age and the full pension age are individual-specific, as they do not only depend on age but also on work trajectories.

As in some countries (Austria, Germany, Norway, for instance), the minimum pension claiming age can be individual-specific. The driving idea is that earlier retirement should be possible for individuals with long career duration. This special scheme was implemented in France in 2003. It introduced the opportunity to retire before the statutory eligibility retirement age (SEA), set at 60 at the time, as early as age 56. Retirement before the SEA is subject to a triple condition of (i) age of first period of work, (ii) number of quarters validatedFootnote 3 in the system, D and (iii) number of quarters of contribution.Footnote 4

The age of eligibility for a full pension can be reached under two conditions: either a standard age condition or a working duration condition. Any worker is unconditionally eligible for the full rate pension if she has reached the NRA, which was equal to 65 before the 2010 reform. The full rate age (FRA) can also be reached before the NRA if the individual has (i) reached the minimum claiming age SEA and (ii) reached the required work duration for full rate D FR. It is then possible to claim a full rate pension from the SEA if the number of quarters contributed to the system is high enough (160 quarters in 2003).

1.2 Alternative pathways to retirement

As we analyze in depth the potential substitution between the pension scheme and alternative insurance schemes, we briefly present the main features of UI, DI and sickness leave insurance (SI) in France. Those schemes can be used to bridge the gap between work and retirement by providing temporary benefits before pension claiming. We focus on the dimensions that are relevant for substitution effects, namely eligibility conditions and the generosity of the replacement rates. The easier it is to enter these schemes and the more generous the replacement rates, the more important substitution effects might be. Another potentially important dimension to take into account is the impact of spells in those schemes on the level of retirement pension benefits. As periods spent in unemployment, disability or sickness leave generate rights for the computation of pension benefits, the detrimental effects of those spells on pension levels are limited.

1.2.1 Unemployment

UI is sometimes described as an unofficial pre-retirement scheme for older workers (Hairault, Reference Hairault2012). Indeed, the specificity of the unemployment legislation regarding older workers, and its interaction with the pension system, makes it a potentially important way of bridging the gap between employment and retirement. A worker becoming unemployed after 50 years can be covered by unemployment benefits for up to 3 years (the maximum duration is 2 years under age 50). This duration can even be extended to a maximum of 8 years.Footnote 5 Indeed, unemployment benefits cannot be claimed beyond the SEA in the general case. However, individuals who have reached this age and do not have the work duration required to receive a full pension can receive unemployment benefits until they reach the full rate (through age or duration criteria). As a result, incentives on the workers’ side are overall important, all the more so since replacement rates are relatively high (approximately 70% of the reference wage – Unédic, 2016).

However, entering the UI system is not in the first place an individual decision, as benefits cannot be claimed after a resignation. A worker must either agree with his employer on the termination of the contract, or be laid off in order to receive unemployment benefits. There is evidence of this kind of collusion behavior in French data, with spikes observed in the rate of entry in unemployment at an ‘optimal age’ for the worker (Cahuc et al., Reference Cahuc, Hairault and Prost2016 or Baguelin and Rémillon, Reference Baguelin and Rémillon2014).

1.2.2 Disability

The disability scheme in France is complex.Footnote 6 An individual can be considered as disabled after sickness or an accident (non-related to working conditions)Footnote 7 and if the ability to work is reduced by at least two-thirds.

The generosity of the scheme depends on the degree of impairment, with a replacement rate ranging from 30% to 70% (with maximum and minimum amounts). Another financial incentive to enter the disability scheme could stem from the fact that individuals recognized as disabled who reach the SEA are automatically eligible to a full rate pension, regardless of the number of quarters validated. The degree of disability is assessed by a referring physician from Social Security. We could then expect limited opportunistic substitution from work to disability. One could imagine, however, that the increase in the SEA would encourage potentially eligible individuals to claim disability benefits, in order to avoid working one additional year.

1.2.3 Sickness

The SI scheme is divided into two categories: short-term leave (up to 1 year) and long-term leave (up to 3 years). Replacement rates are equal to 50% of the previous wage. Any physician can prescribe a sickness leave but workers can be controlled by a referring physician from Social Security during their sickness leave to check whether they are at home and whether they still need to stop working. There is no eligibility condition linked to the pension system: any worker is eligible to SI.

1.3 Recent reforms

1.3.1 The increase in the SEA age

The reform we evaluate in this paper is the increase in the statutory retirement age from 60 to 61, implemented by the 2010 pension reform. The law was published in November 2010. There was mention of a possible increase in the SEA in press records from mid-2009, but neither the exact content of the reform nor its timing of implementation was known before October 2010.

The implementation of this reform is cohort-based: the parameters gradually increase with the year of birth of the individual. Cohort 1951 is the first impacted by the reform, as the SEA increases to 60 years and 4 months for individuals born in the second semester of the year. The SEA then gradually increases and reaches 62 for cohort 1955, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Evolution of the main parameters of the system EEA, SEA and NRA (leftscale) and D FR (rightscale)

In this paper, due to identification issues discussed in the next section, we focus on the first cohorts impacted by the reforms. As they were aged 58 or more when the reform was announced, we can consider that the reform was largely unanticipated for the first cohorts.

1.3.2 Contemporaneous reforms of the pension system

Over the last decades, several pension reforms have modified the main parameters of the system, and we must carefully take into account these simultaneous changes, as that may interact with the reform we consider. In this section, we present those reforms, and discuss the potential identification challenges they imply in a following section.

Along with the increase in the SEA, the 2010 reform also increased the NRA – the age of eligibility to a full rate pension regardless of the working duration. It was raised from 65 to 67, with the same phase-in as the SEA (Figure 1). As we focus on retirement behavior between 60 and 61, we consider as limited the potential interactions with this reform. A potential channel would go through a wealth effect, if the increase in the NRA decreases the social security wealth of a worker exiting from the labor force at age 60. The non-linearity of the French pension formula however strongly limits this effect. First, as previously explained, the FRA can be reached through either an age or a work duration condition. Any worker reaching the full rate work duration before the NRA will then not be impacted by its changes. Second, the penalty for retirement before the NRA is limited to 5 years (the gap between the SEA and the NRA), so that a worker with low work duration and facing a NRA of 66 will have the same pension rate whether she exits the labor force at 60 or 61. Overall, we then expect the wealth effect to be limited.

More worrisome are the potential interactions with the ‘long-career’-based early retirement scheme, which was also largely modified, with reforms in 2009, 2010 and 2012. The two phases of reforms can be summarized as follows. First, the eligibility conditions were progressively tightened: in 2009, with the increase in the required quarters validated and contributed; and then in 2010, with the increase in the early eligibility age to match the increase in the SEA. Then, in 2012, conditions were mildly relaxed: the definition of quarters contributed became less stringent, and more importantly the conditions for early retirement at 60 were strongly relaxed, in order to counterbalance the effect of the 2010 reform of the statutory age which set progressively the statutory retirement age at 62. Lastly, successive reforms in 1993, 2003 and 2014 have progressively increased the required duration for a full rate pension D FR from 37.5 to 43 years. As represented in Figure 1, the phase-in of this increase in D FR is cohort-based, and it interacts with the increase of the age parameters of the system. In the next section, we discuss the consequence of these interactions over our identification strategy and the choice of the control and treatment groups.

1.3.3 Reforms of the alternative pathways

Importantly, the legislative rules concerning the alternative pathways to retirement (unemployment, sickness leave and DI schemes) did not undergo any major change during the period we study. The only significant change occurred in 2009, when UI removed the job search exemption for older workers. It might have impacted the relative ‘value’ of unemployment compared with work and change incentives for a substitution effect but real responses to job search requirements are likely to be small at older ages especially in France where job search control is reduced to a monthly registration update. Consequently, we can consider that most of the substitution effects we observe come from a tightening on the retirement insurance side.

1.4 Data and identification strategy

1.4.1 The administrative social security dataset

Our empirical analysis is based on the French Social Security (RG) administrative records. We use a 1/20th sample of all workers affiliated at least once to the scheme. The data contain very precise longitudinal information on career and earnings but few demographic variables (except gender and nationality). They provide an exhaustive record of the individual career until 2015, but only contain the number of quarters that have been validated each year for the computation of pension benefits: work in the private sector, unemployment or sickness periods, disability or inactivity. Defining a work state for a given year is not straightforward, as individuals may have validated quarters of different types during this year. We attribute as yearly workstate the one for which the individual has validated the largest number of quarters for a given year.Footnote 8 As we only have yearly labor market status, the only way we can match a yearly status to the age-based status is to select individuals who are born in the first quarter of each selected generation.Footnote 9 We also focus on a sub-sample of people that are registered in the general retirement scheme at least once after 50 years old. This selection aims at taking out people such as civil servants, the self-employed or farmers that do not belong to the RG, but also people that are already out of the labor market at age 50.

1.4.2 Identification strategy

In this section, we present and justify the empirical strategy that allows us to identify the effects of the increase in the SEA on the labor market behavior of older workers. Following recent literature studying the changes in the SEA, our evaluation is based on a differences-in-differences strategy. As in Vestad (Reference Vestad2013), the dynamic dimension of the treatment is not based on time but on age. The treatment is defined as being under the SEA. We compare different cohorts who receive the treatment (being under the SEA) at different ages. All cohorts are treated at some point, but at some ages some cohorts are treated and some are not (e.g., 60). Our differences-in-differences strategy relies on the hypothesis that the evolution of patterns would have been the same in the absence of the increase in the SEA. A minimal condition for this hypothesis to be plausible is the pre-treatment parallel trends, which in this case corresponds to a parallel evolution of patterns before age 60 in the treated and control group. The main issue we face for the identification of the effect of the increase in the SEA is the interaction with contemporaneous reforms of the pension system.

First of all, we have to avoid long-career reforms contamination. Therefore, we restrict the sample to the 1950–52 cohorts, designating the 1952 cohort as the treated cohort. We also remove individuals eligible for the anticipatory retirement scheme which represent around 15% of the whole sample. This removal is needed also to satisfy the parallel trend assumption. Indeed, in the absence of an increase in the SEA, we need to ensure that the treated and control groups have the same evolution of labor force participation at early ages and more specifically between ages 59 and 60. People eligible for long-career retirement had a different pattern, due to the restriction on the scheme occurring in 2009. As explained previously, the ‘long-career’-based retirement measures have been relaxed at the end of 2012 to give the opportunity to retire at age 60 for people who have started to work at age 20 and who worked 40 years, whereas the 2010 reform set the retirement age at 61. We must restrict our sample to subgroups that are not simultaneously impacted by different reforms so we only keep the 1952 generation and not the following generations. This comes at the cost of a loss in generality and external validity of the results. It is however the only way to properly estimate the effect of the change in the SEA.

Finally, the increase in the required duration for a full rate pension can also threaten our identification strategy. In particular, this implies that a similar share of the consecutive cohorts would have retired at the statutory age of 60. This may be a rather strong assumption, all the more so for distant cohorts, with different labor market histories and exposed to different legislation. With the triple evolution of a later entrance on the labor market, less linear working trajectories and an increasing required duration for a full rate, more recent cohorts will reach age 60 with a working duration (D 60) further from their full rate duration (D FR). This in turn could imply a smaller proportion of retired individuals at age 60, even in the absence of other reforms. For example, under the hypothesis of a ‘full-rate seeking’ retirement behavior, the proportion of retired individuals at 60 would be exactly equal to the proportion of individuals who have validated D FR quarters at this age, hence it would decrease over time even without any change in the SEA. Table 1 presents the proportion of individuals reaching 60 with a work duration D 60 above the required duration D FR, for each generation of our sample.

Table 1. Work duration at 60 by cohort

Source: Cnav 1/20th sample.

As expected, the proportion of individuals reaching 60 with the requested number of quarters decreases over time. This implies that the hypothesis of a common trend assumption is less and less likely when we compare more and more remote cohorts. We therefore focus on generations as close as possible to each side of the reform: the cohorts 1950–1952. As summarized in Table 2, neutralizing the interaction with those reforms imposes two important restrictions to our main sample: (i) we selected only individuals that are not concerned by the long-based early retirement scheme and (ii) we focused on the first cohort impacted by the reform, namely cohort 1952.

Table 2. Summary of the empirical strategy

1.4.3 Descriptive statistics

The two groups do not display the same characteristics (Table 3). Individuals of the control group are on average more often men, have a longer work duration and higher earnings. The difference observable between the two groups is not necessarily an issue in the differences-in-differences setting, as what matters is the plausibility of the common trend assumption.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

Source: Cnav 1 = 20th sample.

Figure 2 presents the evolution of the proportion of individuals in each possible state (employment, retirement, unemployment, disability, sick leave and inactive) at ages 50–61, for the control and treatment groups. These two groups faced a different SEA, respectively, 60 and 61. In addition to giving an updated picture of the trajectories from work to retirement in France, these graphics give a first idea of the effects we want to measure, as well as an assessment of the validity of the parallel trend assumption at the center of our identification strategy.

Figure 2. Workstate trends by age: treatment vs. control group

First, we do observe rather parallel trends before age 60, the pre-reform SEA. Then, for each state, the increase in the SEA of one year appears to extend the pre-existing trend by one additional year. In addition to the straightforward substitution between retirement and employment at 60, we can observe that the proportion of individuals in unemployment, sickness leave, disability or inactivity also significantly increases at age 60. This is the sum of two distinct effects. First, we can assume that most individuals who were already out of employment before 60 are not returning to employment with the increase in SEA, and simply stay in their previous state 1 year longer. But there may also be some workers who would have retired at 60 and have fallen back on another state.

2. Results

The goal of the empirical strategy is to estimate the effect of the 2010 reform that increased the SEA from 60 to 61 for the generation 1952. We are not only interested in the effects on employment and retirement behavior, but also on the impact on potential substitution routes, such as unemployment, disability and sickness leave. We estimate the following differences-in-differences model:

$$Y_{iact} = \beta _0 + \beta _1X_{iat} + \beta _2\tau _a + \beta _3\delta _c + \beta _4\gamma _t + \beta _5\,{\rm under}\,{\rm SEA} + {\rm \epsilon} _{iact}$$

$$Y_{iact} = \beta _0 + \beta _1X_{iat} + \beta _2\tau _a + \beta _3\delta _c + \beta _4\gamma _t + \beta _5\,{\rm under}\,{\rm SEA} + {\rm \epsilon} _{iact}$$Y iact is a state dummy equal to 1 if the individual i, at age a, from cohort c, at time t is in the relevant state. X iat includes a set of individual controls (gender, country of birth, average earning before 50, number of quarters worked before 50 and number of quarters contributed before 50). δ c represent the cohort dummies (between 1950 and 1952), τ a are the age dummies (from 50 to 61) and γ t the time effects. The dummy underSEA is equal to one if the individual is below SEA, or zero otherwise. The coefficient before this dummy (β 5) is the main coefficient of interest, capturing the effect of the 2010 reform over employment behavior at the ages for which the reform changed the SEA that is only at 60 in this setting as we do not evaluate the further increase from 61 to 62.

As previously mentioned, two distinct cohorts have the same age at different dates, and we might want to take into account some potential determinants of labor force participation that are period-related. For example, if the macroeconomic context is more favorable in 2012 (when cohort 1952 reaches 60) than in 2010 (when cohort 1950 reaches 60), we will attribute the positive impact of the cycle of the employment rate cohort to the 2010 reform. The reforms under study have impacted different cohorts at different ages, and different cohorts reached a given age at different points in time, which we may want to take into consideration, in order not to attribute to the reform some effects of the macroeconomic context.

Therefore, we want to take into account the three dimensions namely, age, period and cohort (APC). We then face the well-known identification issue:Footnote 10 the perfect linearity between age, cohort and period terms makes it impossible to identify the three effects separately without any additional assumptions. One common way to circumvent this issue is to use a different time step (e.g., monthly age, quarterly date, yearly cohort) to generate (quite artificially) some non-linearities between the three dimensions. This method is not adapted to our yearly dataset. Three alternative broad types of solution will be tested in the empirical analysis. The first option is to refrain from imposing any additional parametric restriction and to completely omit the time dimension. The second solution is to impose a rather loose constraint on the period dimension, by normalizing the sum of the coefficients to be equal to zero (Deaton, Reference Deaton1997). Finally, we can include in the main specification a vector of time-varying explanatory variables (Z t), which can potentially capture the macroeconomic cycle effects we want to account for: the GDP growth rate and the global unemployment rate, for instance.

2.1 Main results

Table 4 presents the result of the estimation of equation (1) by OLS, with employment as the explained variable, and different specifications for the time dimension. We only present the differences-in-differences coefficient. Whatever the specification we use, the 2010 reform is estimated to increase the rate of employment by around 21 percentage points. Reassuringly, the estimates are not very sensitive to the specification of time variables.Footnote 11

Table 4. Effect of the increase of SEA on employment rates at age 60

Reading: Standard errors in parentheses. Significance level: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Notes: This table displays the estimate of the effect of SEAgen on employment rates (β 4 coefficient of equation (1)). Additional controls in columns (2)–(5) are gender, country of birth, average earning before 50, number of trimesters worked before 50 and number of trimesters contributed before 50.

Source: Cnav 1/20th sample.

The preferred specification with all the control and time variables is the Deaton specification, which relies on looser assumptions. We then estimate the model for all the possible routes (unemployment, sickness, disability, inactivity). Interestingly, the impact on the unemployment rate is of smaller magnitude than the impact on the employment rate (about 13pp) (Table 5). This confirms that unemployment is a standard route before retiring in France. Disability and sickness play a minor role (comparing to employment and unemployment), however they both represent one-sixth of the decrease in retirement rate at age 60. Overall, the 48pp decrease in retirement is distributed as follows: 40% in employment, one-third in unemployment, one-sixth in disability or sickness leave and the one-sixth in inactivity.

Table 5. Labor market outcome and DD estimate at age 60

Reading: Standard errors in parentheses. Significance level: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Notes: This table displays the estimate of the effect of SEAgen on different possible outcomes. All specifications include controls (gender, country of birth, average earning before 50, number of trimesters worked before 50 and number of trimesters contributed before 50), and use a Deaton specification for the year dummies. Reported pre-policy means are for individuals of cohorts 1950–1951 at age 60.

Source: Cnav 1/20th sample.

The magnitude of the effects we found are high compared with ones found in the literature, in particular concerning the employment effects. Our 21pp estimate is similar to the one found by Dubois and Koubi (Reference Dubois and Koubi2017), and bigger than the one found for similar reforms in other countries: +6.3 in the UK (Cribb et al., Reference Cribb, Emmerson and Tetlow2016), +7.7 pp in Australia (Atalay and Barrett, Reference Atalay and Barrett2015) and +12pp in Austria (Staubli and Zweimüller, Reference Staubli and Zweimüller2013). This is due to the high incentive to retire exactly at the SEA in France, for individuals eligible to a full rate pension through the work duration condition. Overall, it seems that there are large substitution effects from retirement to the relevant previous state: when the SEA increases, individuals that would have retired otherwise spend one more year in their current state. This may not be very surprising but it implies that the short-term impact of a reform of this kind depends largely on the impacted population: the bigger the share of non-employed individuals, the smaller the overall effects on employed individuals and the bigger the substitution effects from the retirement scheme to the other public insurance schemes. This is relevant from both the public finance and the individuals’ welfare point of view. First, the overall financial gains from the reform are reduced if a large part of the population is already out of the labor force, as it also increases spending on other public insurance schemes. We quantify this crowding out effect:Footnote 12 for every €100 saved in the pension system, 20 are spent in other insurance schemes. Second, as retirement pensions are on average higher than their counterpart in other schemes, postponing the transition into retirement could have a strong negative impact on the welfare of individuals that are on unemployment, disability or sickness leave. Increasing the SEA without any change in other insurance schemes is likely to have antiredistributive effects.

2.2 Effects on transitions

As emphasized in the introduction, the tightening of retirement paths are likely to be accompanied by a redirection toward other routes. Following Staubli and Zweimüller (Reference Staubli and Zweimüller2013), we can take advantage of the panel dimension of our dataset to study the transitions between different states. It is possible to estimate the effect of the reform over the persistence into states (e.g., individuals stay longer in employment or unemployment when SEA increases) and transition between states (e.g., increasing transition from work to disability and decreasing transition from work to retirement with the reform).

Potential transitions between states are not directly readable from Table 5. Indeed, we estimate substitution from retirement to other possible routes, but we are not able to differentiate between two types of substitution. As emphasized in Karlström et al. (Reference Karlström, Palme and Svensson2008), tightening the access to one route can have two types of substitution effects. The reduction of the inflows from different states to the restricted one can be decomposed in (i) direct effects of individuals staying one more year in their current state; (ii) indirect effects of individuals who will fall back on an alternative scheme to exit or stay out of employment. Table 6 makes it possible to distinguish these effects by comparing the transitions between ages 59 and 60 for the treated and control groups. In practice, we estimate equation (1) only for ages 59 and 60, and conditioning by the initial state at 59. In Table 6, the rows reflect the initial states, and the columns reflect the final states. We find a strong absorbing effect of the initial states that is substitution of type (i) in the previous distinction: the decrease in transition into retirement is mostly translated into continuation of the previous state. This is the case for 85% of the employment transition (0.35/0.41), 87% of the unemployment transition (0.59/0.67), 96% of the disability transition but only 39% for sickness, which is less of an absorbing state. We do find some evidence of substitution from non-work status to work, especially from sickness leave (29% of individuals in sickness leave return to employment instead of retiring) but also from unemployment (6%) and disability (3%). However, we also find non-negligible transitions from work to unemployment (7% of the decrease in transitions from work to retirement) or to sickness (2%). We also find important substitution of type (ii) for individuals that were in sickness leave at age 59. Even though a non-negligible proportion return to employment instead of retiring (29%), many enter unemployment (19%) or DI (9%). Overall, as employment is the main initial state for the population of interest, we have a more negative substitution (from work to other scheme) than positive ones (from other schemes to work). It should be pointed out however, that we measure very short-term effects of the reform. In the long-run, negative substitutions are potentially weaker if individuals have not initially planned to retire at 60. Similarly, positive transitions from non-work to work may be stronger in the long run, as labor supply and demand adapt to the new pension rules.

Table 6. Effect of the reform on transitions

Pre-reform means give the proportion of individuals in each state at 60 for untreated cohorts.

Reading: Standard errors in parentheses. Significance level: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Notes: This table displays the estimate of the effect of SEAgen on different outcomes. We consider only ages 59 and 60, and we condition on the initial status at 59.

Source: Cnav 1/20th sample.

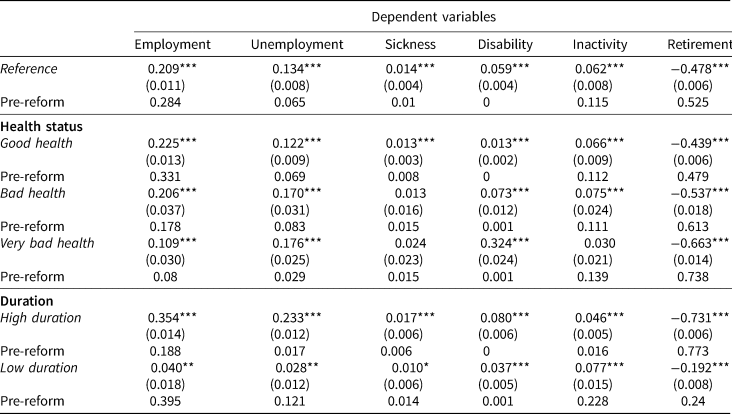

2.3 Heterogenous effects

We then try to exhibit the underlying mechanisms of the employment and substitution effects of the increase in the SEA by estimating our main model on different subgroups. The rational for the heterogeneity of the effect is the following: we expect the effect of the increase in SEA from 60 to 61 to be more important for categories who would have retired at 60 in the absence of reform. For example, a worker who planned to retire at 65 should not be impacted by the reform we evaluate. We then focus on groups that are likely to retire at the SEA: health-constrained individuals, workers who are already eligible for a full rate pension from the SEA. Results of this heterogeneity analysis are presented in Table 7. Following our previous analysis on transitions, we expect that individuals with poor health could be less reactive as they could be physically prevented from working one additional year. We define an individual with a bad health status as a person who has between one and four quarters validated as sick between 40 and 55 years old. An individual is said to be in very bad health if she has validated more than four quarters for sickness.Footnote 13 Consistent with what we expected, a very large proportion of these subgroups would have retired at 60. However, for persons with very bad health, employment increases only by 11pp, amounting to less than or equal to 17% of the decrease in retirement, suggesting a large substitution effect for this group. Indeed, unemployment and disability explained three-quarter of the decrease in retirement. Further analysis shows that there is little substitution from work to sickness or disability at age 60. People in very bad health are already out of the labor market in sickness leave or disability scheme at age 60. There are, however, large substitution effects from sickness to disability.

Table 7. Heterogeneous effects of the reform

Reading: Standard errors in parentheses. Significance level: ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Notes: This table displays the estimate of the effect of SEAgen for different populations (in lines) and different outcome variables (in columns). All specifications include controls (gender, country of birth, average earning before 50, number of trimesters worked before 50 and number of trimesters contributed before 50), and use a proxy specification for the year dummies. Reported pre-reform means are for individuals of cohorts 1950–1951 at age 60.

Source: Cnav 1/20th sample.

Lastly, we split our sample between individuals who have already reached their full rate duration D FR at age 60 (D 60 ≥ D FR), and those who have not (D 60 < D FR). We expect the effects to be more important for the former group. Intuitively, the effect of the increase in the SEA is likely to be more binding for individuals who are eligible for the full rate, as they would have been more willing to retire at 60 without the reform. For this population, a full rate-seeking retirement behavior will indeed predict a concentration of pension claiming exactly at the SEA, and a translation of this concentration with the increase in this age parameter.Footnote 14 For individuals reaching their full rate beyond 61, a full rate-seeking behavior will predict no effect of the reform we evaluate. In accordance with these assumptions, we find a much bigger impact of the 2010 reform for the group with relatively high work duration, with a 73pp decrease in the proportion of retirees at age 60. They drive most of the observed employment effect, but we also observe important substitution effects.

Note that the estimate of the reform is not only weaker for the D 60 < D FR group, it is also potentially biased. It is weak because by focusing on individuals with a relatively low career duration, we restrict our sample to individuals who reach their full rate at older ages. It implies in return that an increase in the SEA has a smaller impact, since an important proportion of this population would have retired beyond the new SEA without the reform. It may also be biased because the effect we measure can be the sum of different mechanisms. In addition to the increase in the SEA, the (small) increase in employment we observe can be attributed to the increase in the full rate duration D FR.Footnote 15 This population includes individuals who reach their full rate between the early retirement age and NRA, which have been identified by Bozio (Reference Bozio2008) as very elastic to the increase in D FR (cf. section ‘Institutional setting’). Part of the effect could also be attributed to a distance to retirement effect, related to the increase in the NRA, which can be the reference age for some individuals of this group. Overall, it implies that we are estimating a pure causal effect of the increase in the SEA only for the sub-sample of individuals who have reached their full rate duration at age 60.

3. Conclusion

In this paper, we studied the effect of an increase in the SEA. We find important employment effects of such a reform, but also non-negligible substitution effects toward other insurance schemes. The analysis of the effect of the 2010 reform showed that increasing the SEA is logically not effective for individuals that are already at the margin of the labor force. Very few non-employed individuals return to employment. As a result, increasing the SEA only amounts to extending the length of the bridge between work and retirement for this population. This may still generate some overall spending reduction, as retirement benefits are on average higher than their counterparts in other insurance schemes. On the one hand, the welfare loss for individuals that are maintained an additional year and in potentially difficult situations, should however be weighed against this reduction in spending. On the other hand, both reforms have shown that increasing the SEA enable to delay withdrawal from the labor force for individuals that are still in employment. The main results of this paper can thus be summarized as follows: increasing the SEA is very effective for individuals that are already employed, and not effective at all for those already withdrawn from the labor force. Two immediate remarks could mitigate this conclusion. First of all, we find evidence of substitution from work to alternative schemes such as sickness, disability or unemployment. In all likelihood, this kind of phenomenon will be more frequent as individuals age, so that any further increase in the SEA could be less efficient, even for employed workers. On the other hand, as we only estimate short-term effects of the reform, we do not measure potential beforehand impact of the reform: individuals exiting employment before the SEA may delay their exit, in order to limit the time spent on the bridge between work and retirement.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sylvie Blasco, Pascale Breuil, Yves Dubois, Thierry Kamionka, Malik Koubi, Jim Ogg and the two anonymous referees for their valuable comments.