Introduction

Epistaxis is a common problem, with a reported lifetime prevalence of 60 per cent.Reference Viehweg, Roberson and Hudson1 Although only a minority of patients seek medical attention, and even fewer require clinical intervention, severe epistaxis has the potential to result in a life-threatening situation. Epistaxis is often characterised based on the site of bleeding, with anterior bleeds accounting for 90–95 per cent of epistaxis and the remainder arising posteriorly.Reference Douglas and Wormald2 While there are many causes of epistaxis, most episodes are idiopathic. Other causes include trauma, medications, recreational drug use, and iatrogenic, haematological or vascular causes.

Atrial fibrillation is a common condition that can lead to devastating consequences such as ischaemic cerebral attacks. Anticoagulation therapy is used to prevent the occurrence of such thromboembolic events. The classic oral anticoagulation therapy is warfarin, a vitamin K derived medication. However, patients on warfarin are required to have regular blood tests to check their internationalised normalised ratio, to ensure that they are within the narrow therapeutic range. Low internationalised normalised ratios can lead to an increased risk of thromboembolic events, while supratherapeutic internationalised normalised ratios can result in catastrophic bleeding. Furthermore, warfarin has numerous interactions with foods and other drugs.

Newer or novel oral anticoagulation therapy, such as direct thrombin inhibitors and direct factor Xa inhibitors, offers some advantages over classic oral anticoagulants. Patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy do not require frequent laboratory monitoring of clotting parameters and there are also fewer interactions.Reference Chen, Viny, Garlich, Basciano, Howland and Smith3,Reference Ganetsky, Babu, Salhanick, Brown and Boyer4 Unfortunately, this means that there is no effective method of measuring the therapeutic effect of the drug. Furthermore, there is a lack of specific reversal agents for many novel oral anticoagulation treatments. Those that exist, such as idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal, are extremely costly.Reference Buchheit, Reddy and Connors5

The use of warfarin and its associated risk of epistaxis have been well-documented in the literature. Novel oral anticoagulation, on the other hand, remains a relatively new therapy. There is a lack of literature on its association with epistaxis and on the management of novel oral anticoagulation patients with epistaxis. This paper reviews the current literature on epistaxis in the context of novel oral anticoagulation use, in order to recommend guidelines regarding its management.

Materials and methods

A comprehensive search of published literature was conducted using the following databases: Medline, Pre-Medline, PubMed and Embase. The search terms included ‘epistaxis’, ‘novel oral anticoagulant’, ‘NOAC’ and ‘reversal’. This search identified 158 relevant articles published in the English language in the full historical range up to April 2019. Appropriate full-text articles were identified and reviewed. Reference lists were hand-searched for additional appropriate articles.

Results

Table 1 presents an overview of the studies on patients with epistaxis while on novel oral anticoagulation therapy.Reference Chen, Viny, Garlich, Basciano, Howland and Smith3,Reference Buchberger, Baumann, Johnson, Peters, Piontek and Storck6–Reference L'Huillier, Badet and Tavernier8

Table 1. Overview of studies on patients with epistaxis while on novel oral anticoagulation therapy

*Intervention being either dialysis, surgery or embolisation. †Combinations of anticoagulation therapy (classic and novel oral anticoagulants), or anticoagulation therapy with antiplatelets (up to two agents). ‡This study collectively presented intervention data together with admissions of over 4 days in duration. **This study calculated the median number of nights for duration of admission. NOAC = novel oral anticoagulant; COAC = classic oral anticoagulant; N/A = not applicable; PCC = prothrombin complex concentrate

Discussion

Epistaxis patients on novel oral anticoagulation

A retrospective study was recently performed in Germany to identify the impact of oral anticoagulant use on epistaxis, with a focus on novel oral anticoagulation therapy.Reference Buchberger, Baumann, Johnson, Peters, Piontek and Storck6 A total of 600 adult epistaxis patients (including 79 multiple presentations), with a median age of 66.6 years, presented to the ENT clinic or were admitted to the ward. Of these cases, 66.8 per cent were anticoagulated. The use of vitamin K derived anticoagulation therapy was three times more common than novel oral anticoagulation. Furthermore, recurrent bleeding without the need for surgical or radiological interventions was significantly associated with oral anticoagulant use. Patients who were on a combination of anticoagulation and antiplatelet medications most frequently had recurrent bleeding episodes (27.9 per cent), while those on novel oral anticoagulation therapy tended to relapse more than those on classic oral anticoagulants (14 per cent and 9.4 per cent, respectively). However, the authors found that severe epistaxis was significantly more likely to occur in non-anticoagulated middle-aged patients with posterior bleedings. Additionally, the anticoagulated patients in this study had significantly shorter durations of hospital stay when admitted and less serious clinical courses compared to non-anticoagulated patients. Therefore, the authors concluded that, while patients on oral anticoagulation therapy were over-represented in the epistaxis cohort, oral anticoagulation therapy is not associated with more complicated and severe courses of epistaxis, but rather with recurrent bleeding.Reference Buchberger, Baumann, Johnson, Peters, Piontek and Storck6

These findings are in contrast to those of Callejo et al.Reference Callejo, Martínez, González, Beneyto, Sanz and Algarra7 In their prospective study, epistaxis patients on dabigatran had an increased rate of transfusions and a greater need for haemostasis with surgery or embolisation, compared to acenocoumarol and no anticoagulation. However, their study included only 19 dabigatran patients, with 5 of them requiring hospital admission. The acenocoumarol group, on the other hand, had 59 presentations with 17 admissions. The authors concluded that, although there are fewer cases of severe epistaxis in patients on dabigatran, these episodes may be more difficult to control and may require more invasive methods.Reference Callejo, Martínez, González, Beneyto, Sanz and Algarra7

A subgroup analysis of the ‘ARISTOTLE’ (Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation) trial looked at the incidence of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving either apixaban or warfarin.Reference Hylek, Held, Alexander, Lopes, De Caterina and Wojdyla9 Major bleeding was defined according to the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria as: clinically overt bleeding, accompanied by a decrease in the haemoglobin level of at least 2 g/dl or transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells, occurring at a critical site, or resulting in death. The authors found that the rate of major haemorrhage among patients in the apixaban group was significantly lower than in the warfarin group (2.13 per cent per year vs 3.09 per cent per year). However, in the cohort of 18 140 patients, only 23 had their first major bleeding in the form of epistaxis. Twelve patients were on apixaban and 11 were on warfarin, and this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, the ‘RE-LY’ (Randomized evaluation of long term anticoagulant therapy) trial found that the rate of major bleeding was significantly lower in those receiving either 110 mg or 150 mg of dabigatran than in those on warfarin (2.71 per cent, 3.11 per cent and 3.36 per cent, respectively).Reference Connolly, Ezekowitz, Yusuf, Eikelboom, Oldgren and Parekh10

It is possible that epistaxis in patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy is less severe, as novel oral anticoagulation therapy does not have the narrow therapeutic range of action that warfarin has. Furthermore, novel oral anticoagulation therapy tends to have fewer drug interactions. Buchberger et al. concluded that patients who have epistaxis while on novel oral anticoagulation have no increased risk compared to the general population.Reference Buchberger, Baumann, Johnson, Peters, Piontek and Storck6 In fact, the former are more likely to have anterior bleeding, which is less likely to result in severe blood loss or prolonged admission. Although it is more probable that these patients will exhibit relapses than patients not receiving anticoagulation therapy, these relapses are unlikely to be of a severe nature.Reference Buchberger, Baumann, Johnson, Peters, Piontek and Storck6

Additionally, a recent retrospective study found that patients who have epistaxis while on novel oral anticoagulation therapy have a significantly shorter duration of hospital admission compared to those on vitamin K derived anticoagulation therapy (3.5 days and 4.5 days respectively).Reference L'Huillier, Badet and Tavernier8 Regardless, the authors suggested having a higher level of suspicion for those with epistaxis who are receiving novel oral anticoagulation therapy, as the bleeding may be more serious than epistaxis that occurs while on vitamin K derived anticoagulation therapy. Reasons for this include the lack of laboratory monitoring, antagonists and guidelines.Reference L'Huillier, Badet and Tavernier8

Investigations

It is the general consensus and recommendation that a full blood count is mandatory in severe epistaxis cases.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White11 However, some authors have concluded that there is no role for routine coagulation studies in patients admitted with epistaxis unless the patient is a child or takes warfarin.Reference Thaha, Nilssen, Holland, Love and White12,Reference Sandoval, Dong, Visintainer, Ozkaynak and Jayabose13 The importance of being aware of any underlying bleeding predisposition because of medications or congenital disorders cannot be understated, as the techniques used to control epistaxis may not be effective in cases of supratherapeutic anticoagulation.Reference Spielmann, Barnes and White11

In cases of severe bleeding with pronounced drops in haemoglobin and a high likelihood of needing either surgery or embolisation, patients on direct factor Xa inhibitors should be tested to determine their plasma levels of anti-factor Xa.Reference Buchberger, Baumann, Johnson, Peters, Piontek and Storck6,Reference Levy, Douketis and Weitz14 For patients on dabigatran, coagulation studies with activated partial thromboplastin time and thrombin time tests should be performed.Reference Levy, Douketis and Weitz14 Activated partial thromboplastin time increases with increasing dabigatran concentration, plateauing at higher drug concentrations. Furthermore, thrombin time is very responsive to the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran. Therefore, if a patient has a low activated partial thromboplastin time and low thrombin time, dabigatran is unlikely to be having a clinically important anticoagulant effect. On the other hand, reversal should be considered in an individual with a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time and major bleeding.Reference Levy, Douketis and Weitz14

Treatment

The appropriate application of first aid principles can effectively arrest minor episodes of epistaxis, avoiding the need for immediate medical attention. Simple first aid measures for dealing with epistaxis are poorly known by members of the public and even some health professionals.Reference McGarry and Moulton15,Reference Strachan and England16

A prospective study performed by Lavy on anticoagulated patients investigated the level of knowledge of basic first aid measures used to combat a nosebleed and methods of education in self-treatment.Reference Lavy17 All 60 patients were instructed on the correct first aid measures to take in order to arrest a nosebleed. Half of these patients were randomised to take home a printed sheet outlining the same measures. Six weeks following the provision of the advice, 27 of the 38 patients who returned the follow-up survey demonstrated a significant improvement in their knowledge of measures to assist in stopping a nosebleed. The author also found that those who were given a printed advice sheet in addition to the verbal advice had a significant improvement in recall rate compared to those who were given only verbal advice.Reference Lavy17

A proposed guideline was developed in 2012 for a stepwise approach to epistaxis management in the hospital setting.Reference Barnes, Spielmann and White18 This specified: initial management (assessment, resuscitation, preparation and examination), followed by direct therapy, tamponade and vascular intervention.Reference Barnes, Spielmann and White18

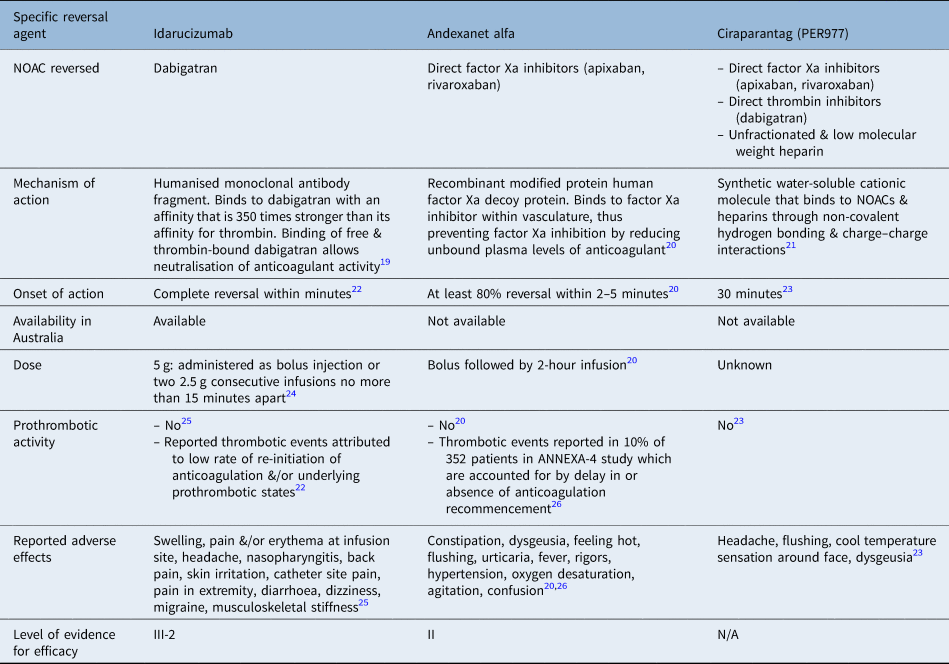

Consideration should be given to attempts to reverse anticoagulation and/or to cease anticoagulant therapy in cases of severe epistaxis. This needs to be assessed and discussed on an individual case-by-case basis, with the involvement of the ENT surgeon, treating cardiologist and haematologist. Tables 2 and 3 present an overview of the specific and non-specific reversal agents for common novel oral anticoagulation used in Australia.Reference Connolly, Ezekowitz, Yusuf, Eikelboom, Oldgren and Parekh10,Reference Schiele, van Ryn, Newsome, Sepulveda, Park and Nar19–Reference Chen, Sheth, Dadzie, Basciano, Howland and Smith32 Idarucizumab is an antibody antigen-binding fragment that binds to dabigatran with a 350-fold higher affinity than thrombin, resulting in an effective and immediate reversal of its anticoagulant effect.Reference Levy, Douketis and Weitz14 Currently, no agents to reverse the effect of other novel oral anticoagulation drugs have been approved in Australia. However, andexanet alfa has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the reversal of factor Xa inhibitors. Phase 3 trials are currently being performed on ciraparantag (PER977).

Table 2. Specific reversal agents for novel oral anticoagulation used in Australia

NOAC = novel oral anticoagulation; ANNEXA-4 = Prospective, open-label study of andexanet alfa in patients receiving a factor Xa inhibitor who have acute major bleeding

Table 3. Non-specific reversal agents for novel oral anticoagulation used in Australia

PCC = prothrombin complex concentrate

Idarucizumab completely reverses the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within minutes of administration.Reference Pollack, Reilly, Van Ryn, Eikelboom, Glund and Bernstein22 A randomised, controlled trial, in which 110 healthy volunteer males were given either idarucizumab or placebo, found that novel oral anticoagulation therapy had no effect on coagulation parameters or endogenous thrombin potential in the absence of dabigatran.Reference Glund, Moschetti, Norris, Stangier, Schmohl and van Ryn25 There were minimal adverse effects in the idarucizumab group, with only reports of mild swelling, pain and/or redness at the infusion site in two subjects. Two subjects also reported headaches as an adverse effect.

The ‘RE-VERSE AD’ (Re-versal effects of idarucizumab on active dabigatran) trial, a prospective single-cohort study of 503 patients, reported serious adverse effects, including delirium, cardiac arrest, sepsis, septic shock and cardiac failure.Reference Pollack, Reilly, Van Ryn, Eikelboom, Glund and Bernstein22 However, most of these events could be attributed to either the initial event or co-existing co-morbidities. This study also found a rate of thrombotic events of 4.8 per cent at 30 days and 6.8 per cent at 90 days. It is thought that the low rate of anticoagulation re-initiation as well as underlying prothrombotic states contributed to these events.Reference Pollack, Reilly, Van Ryn, Eikelboom, Glund and Bernstein22

If idarucizumab is not available, or the patient is on a factor Xa inhibitor anticoagulant, the use of non-specific reversal agents should be considered. The four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate contains factors II, IX, IX and X in high concentrations. Prothrombin complex concentrate is currently used to successfully reverse warfarin-induced anticoagulation, but there is a lack of clinical evidence regarding its use in novel oral anticoagulation associated bleeding. There is some evidence that prothrombin complex concentrate is effective at reversing the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors.Reference Di Fusco, Lucà, Benvenuto, Iorio, Fiscella and D'Ascenzo33 The use of prothrombin complex concentrate is therefore only recommended in cases where there are no specific antidotes available and in the circumstances of life-threatening bleeding that cannot be managed with supportive measures.Reference Levy, Douketis and Weitz14,Reference Di Fusco, Lucà, Benvenuto, Iorio, Fiscella and D'Ascenzo33

Although there is some literature on the efficacy of these specific and non-specific reversal agents, these are largely composed of case reports and observational cohort studies. The lack of randomised, controlled trials can be attributed to ethical concerns regarding the withholding of a reversal agent from a patient who may benefit from it.Reference Pollack, Reilly, Bernstein, Dubiel, Eikelboom and Glund24 A phase 3b–4 study is currently being performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of andexanet alfa use in patients with acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors.Reference Siegal, Curnutte, Connolly, Lu, Conley and Wiens20 Studies on non-specific reversal agents have thus far only been conducted on healthy volunteers to assess the safety of their use. Randomised, controlled trials or prospective clinical studies on the use of these agents in patients with acute bleeding are needed to assess their efficacy in these scenarios.

• Individuals on anticoagulation therapy are at increased risk of epistaxis

• Patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy are more likely to relapse than patients on classic oral anticoagulants or no anticoagulation therapy

• Epistaxis management recommendations are provided, including use of specific and non-specific reversal agents

• Clinicians need to be aware of the potential severity of epistaxis and increased likelihood of recurrence

Epistaxis management recommendations

Here, we describe our recommendations for epistaxis management in patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy.

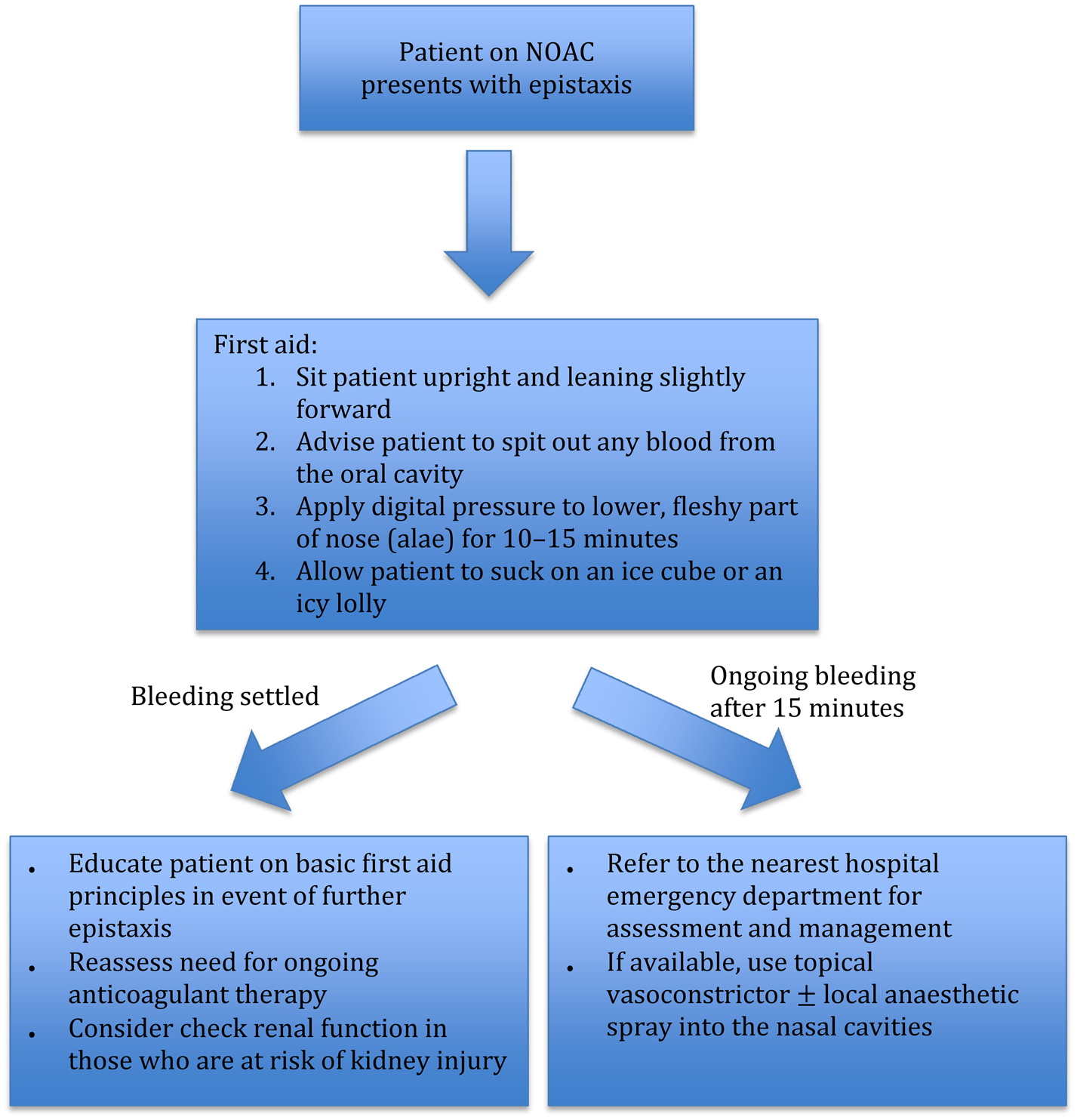

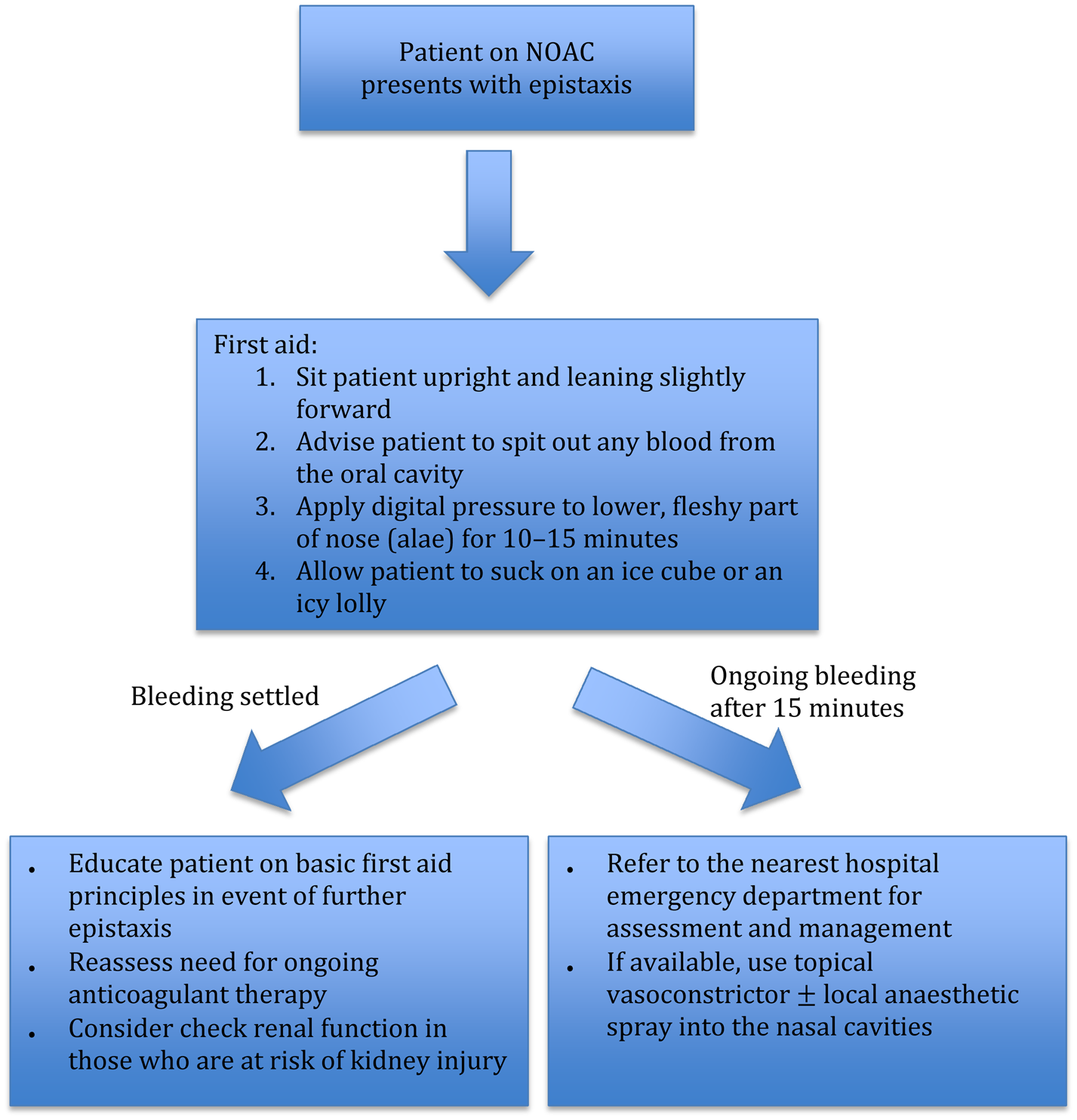

Figure 1 illustrates the basic first aid principles of epistaxis. We recommend the Dundee protocol for the management of adult epistaxis, as outlined by Barnes et al.Reference Barnes, Spielmann and White18 However, if the patient is on novel oral anticoagulation therapy, medical staff need to be aware of the potential for severe epistaxis and the increased likelihood of recurrence.

Fig. 1. Flow chart outlining first aid measures and management for epistaxis in the community setting. NOAC = novel oral anticoagulation

All epistaxis patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy presenting to the emergency department should be assessed and managed concurrently according to the ‘ABCDE’ (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure) principles. The timing of the last dose of novel oral anticoagulation should be obtained. We recommend getting intravenous access and sending blood samples for a full blood count, creatinine and coagulation studies, and ‘group and hold’ sample processing. Patients on oral factor Xa inhibitors should also have a specific anti-factor Xa assay performed.

If there is active, torrential bleeding or the patient is haemodynamically unstable, the treating team should consider early involvement of the haematologist and cardiologist regarding attempted anticoagulation reversal. For major, life-threatening haemorrhages, patients on dabigatran can be given idarucizumab for reversal of the anticoagulant effect. In the USA, patients on direct factor Xa inhibitors can be given andexanet alfa. However, using these reversal agents places the patient at risk of thrombotic complications. In cases where there are no specific novel oral anticoagulation reversal agents available, we recommend the use of non-specific reversal strategies (e.g. four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate or haemodialysis) only in consultation with the haematologist. The decision on whether novel oral anticoagulation therapy should be temporarily withheld needs to be made in consultation with the cardiologist, and in consideration of the individual patient's risks of bleeding and thrombotic events.

Upon discharge, all patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy should be given a written advice sheet on basic first aid manoeuvres in case they develop any further epistaxis.

Conclusion

Patients with epistaxis frequently present to the emergency department and are commonly referred for ENT review. All patients on novel oral anticoagulation therapy should be educated on basic first aid principles for epistaxis. Clinicians need to be aware of the potential severity of epistaxis and the increased likelihood of recurrence in these individuals. Patients with epistaxis should be managed in a stepwise fashion, in an attempt to control the source of bleeding. Idarucizumab is an effective, but expensive, reversal agent for dabigatran. There are currently no approved specific antidotes for factor Xa inhibitors. Involvement of the haematologist and cardiologist should be sought early in cases of severe epistaxis. Recommendations for epistaxis management for patients receiving novel oral anticoagulation therapy are outlined. Further high-quality studies are required to determine the efficacy and safety of andexanet alfa and ciraparantag, as well as the non-specific reversal agents.

Competing interests

None declared