In a New York Times Magazine interview with Frank Rich, Stephen Sondheim (b. 1930) told an anecdote as revealing as it was charming. Reminiscing about the New Haven opening of Carousel in 1945, when he was fifteen, the composer/lyricist recalled the emotional impact of the first act’s closing moments: ‘I remember how everyone goes off to the clambake at the end of Act One and Jigger just follows, and he was the only one walking on stage as the curtain came down. I was sobbing.’1 In the next paragraph, however, Sondheim displays a more characteristic caginess when considering why Carousel is his second favourite score. (Porgy and Bess is his favourite.) After suggesting that he might be drawn to Carousel ‘because it’s about a loner [the protagonist Billy Bigelow] who’s misunderstood’, Sondheim dismisses the thought, calling it ‘psychobabble’.2 Later in the interview, he returns to this somewhat defensive argument, noting that, after all, ‘the outsider is basic to a lot of dramatic literature. This country’s about conformity. And so nonconformity is a fairly common theme.’3

Nonconforming outsiders are indeed inherent in much dramatic literature. American musicals, however, have generally avoided them, and certainly their presence as protagonists in musicals before Carousel is rare. Even their existence as important supporting characters is unusual. Notable exceptions exist, of course. They include the mulatto Julie in Show Boat (1927), the discovery of whose racial heritage results in her dismissal from the showboat company and her subsequent tragedy, and Jud Fry in Oklahoma! (1943), whose angry isolation is voiced in the disturbing number ‘Lonely Room’. With the possible exceptions of Pal Joey (1940) and the opera-derived Carmen Jones (1943), however, musicals before Carousel were not about these outsiders. Instead, these were secondary characters whose conflict with society usually resulted in society’s triumph. Interestingly, each of these rather atypical works, with the exception of Pal Joey, had book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, Sondheim’s mentor and close personal friend. Only after Carousel, which was also written by Hammerstein, do we find the outsider increasingly cast as the principal figure in a musical, particularly a musical with a score by Stephen Sondheim. Perhaps, as Sondheim acknowledges, this is because the nonconformity of the outsider is ‘obviously something I feel, belonging to a number of minorities’.4 (Sondheim is Jewish and gay.) Or perhaps such observations really are psychobabble. Either way, Sondheim’s body of work for the musical theatre thus far suggests that his early emotional reaction to a work about a disenfranchised member of society, a nonconformist, was an indication of the theme upon which he since has written many variations, each of them in a distinct personal style. He seems always to have been attracted to characters whose actions place them outside mainstream society. Neuroses are plentiful in these musicals, and they are found in characters whose complexities often recall the loner who troubled and moved the young Sondheim.

Sondheim’s first Broadway shows were West Side Story (1957) and Gypsy (1959), for which he provided the lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s and Jule Styne’s scores, respectively, and even they are concerned with outsiders and/or the disenfranchised. Already Sondheim’s lyrics create sharply drawn characters who express, among other feelings, a frustration with, or even contempt for, mainstream society. West Side Story, for example, concerns several layers of social ostracism: a white gang (the Jets) aggressively treats a Puerto Rican gang (the Sharks) as outsiders from American society, and the Sharks deeply resent and violently challenge that status; both gangs are disenfranchised from society in general (in the clever lyrics of the number ‘Gee, Officer Krupke!’, the Jets chronicle their misfit status); and the lovers Tony and Maria are rejected by both gangs because of their relationship. Sondheim’s lyrics for the show create an expressive vernacular that emphasises the strained social relationships between the two gangs. Gypsy’s Mama Rose thumbs her nose at ‘respectable’ bourgeois society: ‘they can stay and rot’, she sings, ‘but not Rose’. Only at the end of the show, when Rose breaks down in ‘Rose’s Turn’, does the audience see the toll that this disenfranchisement has taken. Furthermore, both of these early works also feature a motive common to several of the later works: the outsider’s ability, or at least hope, to escape reality through dreams or dreamlike fantasy. West Side Story contains a dream ballet in which the two principal characters imagine a life in which none are outsiders; and Gypsy is full of Rose’s leitmotif ‘I had a dream’, with which she confronts various crises.

Many of Sondheim’s subsequent outsiders also express themselves in or through dreams, or in dreamlike detachments from reality. In Follies, for instance, the neurotic and emotionally frazzled characters take turns performing acts in an imaginary and nightmarish vaudeville. Much of the action of Company (1970) occurs in a timeless and dreamlike suspension of reality in which Robert, an emotionally detached bachelor, comes to grips with what he really wants from life. In the second act of Sunday in the Park with George (1984), the twentieth-century George is consoled and inspired by the dreamlike apparition of Dot, a character from another century (and another act), and in Assassins (1991) the characters fervently, if desperately, believe that ‘Everybody’s got the right to their dreams’.

A consideration of Sondheim’s scores as representations of the outsider provides an entrée to discussing some of their general and specific stylistic traits. These traits create what Sondheim scholar Steven Swayne has called Sondheim’s ‘multiple musical voices’, many of which are imitative or referential.5 Specifically, argues Swayne, Sondheim exploits this ‘range of musical voices in pursuit of his singular voice: the voice of character delineation’.6 While Sondheim’s principal purpose, therefore, is the clear depiction of individual characters, his means for achieving it are as diverse as the concepts for the shows in which those characters exist.

The introduction previously of the word ‘concepts’ in turn demands mention of the term ‘concept musical’, for it is often applied to Sondheim’s work in general and relates specifically to any discussion of his means of creating characters for a given show. Joanne Gordon sums up this term as follows:

Concept, the word coined to describe the form of the Sondheim musical, suggests that all elements of the musical, thematic and presentational, are integrated to suggest a central idea or image … Prior to Sondheim, the musical was built around the plot … The book structure for Sondheim, on the other hand, means the idea. Music, lyric, dance, dialogue, design, and direction fuse to support a focal thought. A central conceit controls and shapes an entire production, for every aspect of the production is blended and subordinated to a single vision … Form and content cannot really be separated, for the one dictates and is dependent on the other.7

In other words, Gordon continues, Sondheim ‘develops a new lyric, musical, and theatrical language for each work. Sondheim’s music and lyrics grow out of the dramatic idea inherent in the show’s concept and themselves become part of the drama’.8

Two compositional techniques especially facilitate Sondheim’s ability to change musical languages without losing his own ‘singular voice’: the use of motives, or short, recognisable musical ideas that sometimes represent non-musical concepts or characters and that are often used as structural cells for lengthier musical statements; and the use of pastiche, which is the presence of music and/or musical styles from various sources in a single work. While the first of these is observable as early as Company and, after Sweeney Todd (1979), becomes increasingly important, the second appears as a recognisable trait even earlier and is variously exploited by Sondheim in nearly all his works.

Company, then, serves as an early example of one way Sondheim uses motives to define the character of an outsider. Throughout Company, Sondheim uses a recurring motive, the ‘Robert’ or ‘Bobby’ motive, as a cell, or building block, for much of the score, as Stephen Banfield has demonstrated.9 (The motive, first sung to the words ‘Bobby, Bobby’, consists of a descending minor third followed by a descending major second. The initial pitch of each interval is the same.) What Banfield does not mention, however, is the careful utilisation of this motive in relation to Robert and the other characters, and as a musical symbol of Robert’s detachment from his married friends. It is heard almost immediately at the show’s beginning, and a development of it introduces the opening title song. After this, the motive is used between scenes and before, or as part of, musical numbers involving Robert and his married friends, a group from whom he is an outsider despite the mutual affection between them.

The motive does not introduce songs that involve characters or their observations without Robert, however. This is evident in ‘Little Things’, a commentary by the acerbic Joanne on another couple’s scene as well as on marriage in general, and ‘Sorry Grateful’, the men’s reflective answer to Robert’s question, ‘Are you ever sorry you got married?’ The motive neither introduces nor appears in songs that involve Robert on his own or without the couples, such as ‘Someone Is Waiting’, or ‘Barcelona’, his emotionally removed duet with a flight attendant. Although these numbers do not quote the motive, they are frequently built on it, often by inverting it, as Banfield points out. Perhaps the most dramatic use of the motive is in the dance sequence ‘Tick Tock’, omitted from the revised version of the show. In this number the audience hears taped dialogue of Robert and the flight attendant during sex. At a critical, post-coital moment, she says, ‘I love you’, and the motive is heard. It signifies what the couples all along have been wanting Robert to hear and experience; it represents their hopes fulfilled, as well as their presence in even his most intimate life. Robert, however, can only respond with ‘I … I …’, at which point the orchestra plays a dissonant fragment of the motive that signifies Robert’s inability to express what everyone else wants him to express.

The central character’s inability to respond reinforces his outsider status in the world of the married and emotionally committed. It is a telling moment, harking back to an earlier moment in the second act when, in the course of a production number, several couples perform a call-and-response tap dance break; when it is Robert’s turn, there is a call but no response. Robert’s motive, therefore, is expressive of the gulf between Robert and the couples, between Robert and thoughts of marriage and between Robert and any kind of emotional commitment. On his own Robert can only recall the motive by transforming it into something else. Woven into the show’s texture, the motive and its transformations, along with the accompanying lyrics, create a web that is present in some form throughout the show, and that defines Robert as a singular figure on the outside of a world of couples. This kind of motivic development is later greatly utilised by Sondheim, especially in Sunday in the Park with George and Into the Woods (1988).

Plate 17 Production of Company in 2001 at the Kansas City Repertory Theatre (formerly Missouri Repertory Theatre). Left to right: Kathy Barnett, Tia Speros, Cheryl Martin, Paul Niebanck, Lewis Cleale (as Robert, the ‘other’ who is unable to make a connection with his friends).

Sondheim’s use of pastiche appears even earlier, as previously noted. In Anyone Can Whistle (1964), his second produced show as both composer and lyricist,10 Sondheim made use of what he calls ‘traditional musical comedy language to make points. All the numbers Angie (Angela Lansbury, one of the show’s co-stars) sang in the show were pastiche – her opening number, for instance, was a Hugh Martin–Kay Thompson pastiche. The character always sang in musical comedy terms because she was a lady who dealt in attitudes instead of emotions.’11 Interestingly, Sondheim has also said of this show that, ‘Essentially the show is about, on one level, non-conformity and conformity in contemporary society.’12 Although the show ran for only nine performances, the score is original and often memorable, and it explores subjects like sanity, depression and twentieth-century fears with a decidedly musical theatre vocabulary.

Sondheim also uses the vocabulary of the musical theatre in Follies (1971). Because Follies, in the words of director/producer Harold Prince, ‘deals with the loss of innocence in the United States, using the Ziegfeld Follies … as its metaphor’,13 musical pastiche is a natural choice for realising that metaphor. Here, however, Sondheim gives resonance to characters who, unhappy with the present, look back to a past best recalled by its music and by their memory of having sung it. (The characters are former showgirls and their husbands, and the title refers to their former employment as well as to their personal delusions.) As Joanne Gordon observes, ‘The work is a voyage into the collective unconscious of America’s theatrical imagination. Nostalgia is not merely the mood, it is the subject matter.’14 To this end, Sondheim writes musical numbers that recall the past eras referred to in the script and for which the characters express nostalgia, as well as numbers that are ‘book’ songs sung by the characters in the unhappy present. Because the script calls for the representation of the characters in their past youthful days as well as their present middle age, Sondheim sometimes combines the two styles of writing and creates a surreal blend of past and present.

The pastiche numbers, however, are most effective in the last section of the show, a kind of musical revue–nervous breakdown in which each of the four principal characters expresses his or her individual neurosis. Sally, a former chorus girl who is now unhappily married to a travelling salesman and living a nondescript suburban life in the American Southwest, expresses her long-standing love for Ben, a friend’s husband whom she has quietly loved for years, in a Gershwin-like torch song. The rather mousy and decidedly unglamorous Sally stands alone in a circular spot, clad in a clinging silver gown evocative of Jean Harlow, and passionately sings ‘Losing My Mind’, one of Sondheim’s most powerfully emotional love songs. Her husband Buddy, on the other hand, sings a patter song about loving one woman (Sally) but finding affection only in the arms of another. The upbeat and funny vaudeville quality of the song, a baggy pants routine, barely masks Buddy’s desperate frustration with a lifetime of watching his wife love another man. Phyllis, Sally’s former best friend and the wife of the man Sally loves, has a production number that speaks of her schizophrenia: ‘The Story of Lucy and Jessie’ depicts Phyllis as a young woman, warm and loving but fearful of life, and as a middle-aged woman, classy but emotionally dead. The irony is that each wants to be the other. This number recalls both Cole Porter and Kurt Weill, especially ‘The Saga of Jenny’ from Lady in the Dark.

The final number in this follies of the mind is for Ben, Phyllis’s husband and the man loved by Sally. This is a top hat and tails number that also recalls Gershwin or, perhaps, the syncopated dance tunes of Irving Berlin. As Ben swaggers to the song, cane in hand and backed by the ensemble, he quite literally falls apart, forgetting his lyrics and losing control until the nightmare takes over and the revue literally explodes in a cacophony of musical fragments and shadowy images. Sondheim’s choice of material to parody in this final section of the show is what makes the numbers so effectively devastating, and it is his most powerful and successful use of pastiche up to that point. His portraits of the neurotic and troubled characters are almost painful to watch, and they are created with great sympathy for the individuals who yearn for a time that was not nearly as happy, or tuneful, as they like to remember.

The complex web of relationships that forms A Little Night Music (1973) is one of outsiders. Of all the characters, Henrik most exemplifies this state. He goes from being a misfit at the seminary to being a misfit at home to being a misfit at Mme Armfeldt’s estate. Indeed, before gathering with others at the estate for a weekend, Henrik notes that ‘the devil’s companions know not whom they serve, / It might be instructive to observe’. Henrik eventually does more than observe, however. Before the end of the weekend, and after contemplating suicide, he runs off with his father’s young bride, who also realises her emotional and chronological distance from her husband and the others. The flight of Henrik and Anne propels the plot to its conclusion, in which the various characters rediscover their relationships and their places inside – or outside, as the case may be – the society around them. Desirée, the principal female character, compares the group of adults to clowns in ‘Send in the Clowns’, Sondheim’s most famous song. After a statement of the song’s titular command, Desirée changes her mind. ‘Don’t bother’, she reconsiders, ‘they’re here.’

One of the most original creations for the musical theatre Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979) is filled with outsiders, colourful characters who are all dispossessed persons, outsiders in nineteenth-century London. Sweeney Todd, alias Benjamin Barker, a half-mad barber bent on revenge, comes to London to murder Judge Turpin; when the intended victim escapes Todd’s blade, Todd swears to kill all who visit his barber’s chair until he cuts Turpin’s throat.

In ‘Epiphany’ Todd’s inner need for revenge is awakened to some of the angriest and most disturbing music ever written for the musical theatre. In the subsequent duet ‘A Little Priest’, Todd and the resourceful Mrs Lovett, who loves him, devise a plan to solve both of their problems – Todd getting rid of his murdered bodies and Mrs Lovett finding a source of meat for her pies. The cannibalistic fantasy, with its grotesque lyrics that describe how members of various professions would taste, appears as a light-hearted waltz. The counterpoint between the lyrics and the music accentuates the macabre nature of the duet.

The idea of using the waltz idiom to accompany dark and menacing lyrics was of course nothing new. Sondheim himself had used it throughout A Little Night Music, but in Sweeney Todd the style took on an even more demonic character. This would become manifest in two numbers in Assassins, as we shall see: the opening sequence, where ‘Hail to the Chief’ is transformed into a waltz, and ‘Gun Song’, where the carefree waltz is the musical identifier in a number that celebrates the weapon of assassination.

In the fairy-tale-based Into the Woods (1987), Sondheim once again has nontraditional characters as the central figures in his musical. Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Jack (of beanstalk fame), Rapunzel and even Snow White appear in this musical about outsiders, all of whom have their own personal issues, working together to solve bigger problems. Encased in a larger tale of a baker and his barren wife who is under the spell of a witch, the stories of the familiar fairy tales are enhanced through their dramatic and musical treatment. Rapunzel’s Prince and his brother, Cinderella’s Prince, sing the waltz duet ‘Agony’, and the instructive ballads ‘No One Is Alone’ and ‘Children Will Listen’ have enjoyed lives of their own outside theatrical contexts. ‘No One Is Alone’ is a benevolent anthem to outsiders – people are never completely disconnected from others in their thoughts and actions.

Before turning our attention to Assassins, a veritable treasure chest of otherness that will occupy the rest of this chapter, we must acknowledge two other shows with scores by Sondheim that further demonstrate varied conditions of outsiders: Passion (1994) and Bounce (2003). The former concerns the life-altering and transformative love of a sick and physically unattractive woman – an outsider in every sense, from her physical to her emotional isolation from society – while the latter considers the troubled relationship of two entrepreneurial brothers who find it impossible to sustain themselves within the confines of society. The scores for these two shows inhabit different stylistic worlds, Passion rising to operatic heights through some of Sondheim’s most exquisite music and Bounce recalling a more traditional Broadway style not unlike the earlier Merrily We Roll Along. Despite their being wildly different, each of these shows nonetheless provided Sondheim with additional sets of characters whose status as outsiders he could musically confirm.

It is in Assassins, however, that Sondheim is at his best portraying the neurotic outsider. Nowhere in Sondheim’s work is this character type created with more explicit sympathy, humour or irony. Assassins is a troubling work that perplexed and even angered some critics and still has the power to disturb American audiences.15 In this piece all the characters are would-be or successful assassins of American presidents. They are also unhappy loners and, from society’s perspective, losers. In Assassins, furthermore, Sondheim and the playwright John Weidman suggest that, with the exception of John Wilkes Booth, none of these singular figures acts out of any specific political motivation. Instead, their acts are explosive expressions of their hopeless and powerless positions in a system that seems, to them, to have been designed for the well-being of someone else. Individually and as a group, these men and women feel cheated and deprived of a happiness they view as their right. They express these feelings in one of Sondheim’s most accomplished scores. How he gives voice to these outsiders, and how his technique for doing this is unique in this work, is fascinating.

Weidman and Sondheim, who had earlier collaborated on Pacific Overtures (1976), created Assassins after the model of a vaudeville-like revue, a choice that contributed in several ways to the successful presentation of the disenfranchised titular characters. It encouraged Sondheim to exploit pastiche in new and sophisticated ways. Previously, as noted, the composer/lyricist used familiar and traditional musical theatre song styles to underscore aspects of situations and characters. In Assassins, however, the reach of Sondheim’s stylistic net is much wider. The sources for his pastiche include pre-existent and often familiar pieces of music from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1980s. He also parodies familiar popular song styles from nineteenth-century parlour songs to 1980s pop love songs, as well as popular dance styles such as cakewalks, Sousa marches and hoe-downs. Non-musical sources include historical poems, lyrics, interviews and quotations. In addition, historical characters are interwoven throughout various eras to create relationships that would have been chronologically impossible. Such an extended use of historical materials, musical and textual, is unprecedented in Sondheim’s work. He exploits these sources to probe the troubled psyches of deeply disturbed, and disturbing, outsiders.

By taking the familiar vocabulary of American music and using it to give voice to the disenfranchised and the desperate, moreover, Sondheim uses pastiche to particularly ironic effect. Comfortable and sometimes comforting styles of American popular music are used to depict an underside of American society, a depiction that in turn causes discomfort. Sondheim recasts or de-familiarises the comfortable styles by using them for characters who make us squirm but whose disenfranchisement, we begin to see by the show’s end, is just as American as the ‘comfortable’ musical space it inhabits. When Sondheim uses popular song styles in ways that subvert the connotations they have carried for a century or more, he is taking a drastic stylistic step, one that cannot but disturb and unsettle American audiences. Sondheim thus creates a network of textual references to give individual numbers, and even the entire score, meanings they might otherwise lack. The whole work is a carefully spun web of various references that maintains cohesion in part through the manipulation of these references and the viewer’s assumed knowledge of them. This combination of references, demonstrated shortly, is adroit and powerful.

The vaudeville model for Assassins allows each character to have his or her appropriate turn, or specialty number, each following the other in no particular order and each in a different musical style. Giuseppe Zangara sings his Sousa-inspired number strapped in an electric chair, looking as if he might at any moment make a Houdini-like escape; Charles Guiteau sings and dances a jaunty cakewalk up and down the hangman’s scaffold; and Samuel Byck dictates monologues into his tape recorder as if performing stand-up comedy. This combination of seemingly unrelated styles and personalities is, of course, characteristic of American vaudeville, which was derived from, and often satirised, established genres of entertainment. The unrelated styles also allow the distinctness of each character from the others, as well as from society in general. The individual messages from the fringe are similar, but they are spoken with different musical vocabularies.

The choice of the vaudeville model no doubt also suggested the nonlinear structure for Assassins. Like Follies and, especially, Company, the show moves smoothly but non-chronologically through time. Sometimes its dejected historical characters meet in locations nonspecific to any one time period: a saloon in downtown New York City, for instance, that looks the same today as it did in 1900. Other times, however, the setting is almost painfully specific: the penultimate scene takes place in the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas, just before the assassination of President John Kennedy. Sondheim also creates extended musical scenes through collections of numbers related by dramatic content and musical styles. ‘How I Saved Roosevelt’ is a collection of closely related but meaningfully contrasted dances. ‘Gun Song’ is a collection of waltzes, each of which deals with a different aspect of handguns and features a character from a different era. These waltzes are stylistically diverse, but they are connected by a refrain and preceded, as well as followed, by a sombre ballad, also a waltz. ‘The Ballad of Guiteau’ mixes hymn, parlour song and cakewalk. Stephen Banfield has called these sequences ‘suites’.16

The focus of one of these suites (‘How I Saved Roosevelt’) is Giuseppe Zangara, an Italian immigrant who, in February 1933, attempted to kill President-elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Miami. He failed, but he managed to wound several others, including the mayor of Chicago, Tony Cermak, who subsequently died from his wounds. After Cermak’s death, Zangara’s life sentence was changed to death by execution in the electric chair. Zangara’s only political agenda was his simple if fervent anti-capitalism: he was neither an anarchist, a socialist nor even a communist. He bore no grudge towards any individual figure, including Roosevelt.

While ‘How I Saved Roosevelt’ creates a vivid portrait of Zangara, it also contrasts him with a group of patriotic Bystanders, as Sondheim calls them, all of whom claimed to have thwarted the assassination attempt. These individuals each received and enjoyed much attention in the press and became momentary celebrities for their claims of having saved FDR. The contrast of Zangara’s passionate anti-capitalism with the all-American absorption with self-promotion and celebrity in the press creates the bipolar perspective of the musical scene. When we add to this the fact that before Roosevelt’s appearance, a band gave a concert at Bayfront Park’s new bandshell,17 we have the makings of a musical number, and it is from here that Sondheim works his magic.

Through an onstage radio, we hear the activities at Bayfront Park: a performance of Sousa’s march ‘El Capitan’, an announcer’s description of the festive scene and then of the unsuccessful assassination. The announcer summarises the ensuing events, ending with, ‘We take you now to a group of eyewitnesses who will tell us what they saw.’ The lights come up on five Bystanders and, as the band resumes ‘El Capitan’, they begin singing.

Sondheim’s choice of ‘El Capitan’ is interesting. One of Sousa’s best-known marches, it, too, is a pastiche of unrelated musical numbers from Sousa’s most successful operetta, also titled El Capitan. This lighthearted work is also concerned with political insurrection and turmoil. After opening his number with a direct quote of the march’s four-bar introduction in 6/8 time, and thus emphasising the diegetic aspect of the march being played in Bayfront Park, Sondheim builds a melody related to Sousa’s, albeit more of a recognisable reminiscence than a direct quote. In the third strain of the march Sondheim changes the character through a shift to sustained quartal harmony (i.e. harmony based on fourths). This serves as Zangara’s introduction into the number, and the lights come up on him confined in the electric chair. In the middle of this section, after the minor mode unambiguously appears, Zangara’s music is transformed into a tarantella.

Whereas the character of the Sousa march indicates the patriotic American middle class and its capitalist system, the tarantella is, in this context, distinctly ‘other’ and foreign. Its heritage as a folk dance reflects Zangara’s poor Italian background and provides a clear contrast to the Sousa march’s more bourgeois origins. Since both are in 6/8 time, transition from one to the other is relatively simple.

After Zangara’s interlude, the strains of ‘El Capitan’ return, and the Bystanders begin again. After they sing the same musical material as in the opening section of the number, Sondheim takes another surprise turn and introduces ‘The Washington Post’, another Sousa march that operates on more than one level. The first, of course, is that the ‘The Washington Post’ represents the establishment press to whom the Bystanders are so eagerly and self-importantly telling their stories. The other level is that of yet another dance style. After its composition by Sousa in 1899, ‘The Washington Post’ was chosen by a group of dance instructors as suitable for a new and fashionable dance called the two-step, which in many places is still referred to as ‘The Washington Post’. This dance, then, implies another contrast in social class.

When the music yet again returns to ‘El Capitan’, a Bystander refers to Zangara as ‘Some left wing foreigner’. Zangara, however, refutes the term ‘left wing’ with a chilling section best described as a miniature mad scene. Here the orchestra plays dissonant snippets of the march melodies in counterpoint to Zangara’s increasingly higher, and increasingly intense, vocal line. After asserting ‘Zangara no foreign tool, / Zangara American! / American nothing!’ Zangara begins asking about the photographers. He sings, ‘And why there no photographers? / For Zangara no photographers! / Only capitalists get photographers!’ Odd though it is, this ranting is based on fact: in its report of Zangara’s execution in March 1933, Newsweek reported that Zangara said, ‘No camera man here? No one here to take picture? Lousy capitalists! No pictures! Capitalists! All capitalists! Lousy bunch! Crooks.’18

What Sondheim does with this outburst is particularly ingenious. Zangara’s diatribe about photographers equates him with the Bystanders, who are smitten with the press and excited by their importance to it. To point out this new, if fleeting, relationship between Zangara and the Bystanders, Sondheim again quotes the second strain of ‘El Capitan’ and has Zangara sing a counter-melody while the Bystanders sing the original melody. Zangara’s identifying tarantella, then, transforms into an integral section of the march. After Zangara asks, ‘And why there no photographers? /…/ Only capitalists get photographers’, he comments ‘No right! / No fair / Nowhere!’ as the Bystanders sing, ‘I’m on the front page – is that bizarre? / And all of those pictures, like a star!’ The implication is that, for at least this one moment in his life, Zangara envies the capitalist middle class more than perhaps he ever dreamed possible, even as he distinguishes himself from them. Because of Zangara’s presence on stage with the Bystanders, the original lyrics for this phrase in Sousa’s operetta are almost eerie: ‘Gaze on his misanthropic stare. / Notice his penetrating glare.’ As both Zangara and the Bystanders reach the end of the number, Zangara sings, ‘Pull switch!’ and a hum of electricity accompanies the number’s final cadence.

Sondheim again references and/or quotes other texts, musical and non-musical, in his portrayal of Charles Guiteau in ‘The Ballad of Guiteau’. On the surface an affable lunatic who shot James Garfield to preserve the country and promote the sales of his book, the singular Guiteau is given a pathetic and angry underside. This is done in part through recalling writings by the character as well as subsequent folk songs about him. (Indeed, the body of extant folk songs about political assassination in fact suggests that Assassins is the latest in a long line of works in popular genres about this aspect of the American character.)

On the day of his execution, Charles Guiteau wrote a poem that begins, ‘I am going to the Lordy; / I am so glad. / I am going to the Lordy / I am so glad. / I am going to the Lordy, / Glory Hallelujah! Glory Hallelujah! / I am going to the Lordy.’19 This poem intrigued Sondheim, who first encountered it in the short play by Charles Gilbert that inspired Assassins, and he opens Guiteau’s number with its first lines. They are sung hymn-like and unaccompanied, and Sondheim continues to use the line ‘I am going to the Lordy’ as a recurring refrain between the number’s sections. The contrast of Guiteau’s fervent yet hymn-like poem with the musical styles that follow it suggests Guiteau’s mental imbalance, a trait the audience has already seen. He is glib, frequently charming and completely insane.

Sondheim first contrasts Guiteau’s mad hymn with a parlour song in 3/4 time sung by the narrating Balladeer. The opening lines also recall the opening exhortation of the folk song mentioned earlier, which is, ‘Come all ye Christian people, wherever you may be, / Likewise pay attention to these few lines from me.’ Sondheim distils this to ‘Come all ye Christians, and learn from a sinner’.

Musically, Sondheim constructs a useful structure for all this textual reference. As noted earlier, the opening is an unaccompanied hymn sung by, and with lyrics by, Guiteau himself. Because the lights come up to reveal him at the foot of a scaffold, his reference to ‘going to the Lordy’ is amusing. The music, however, is a straightforward and almost austere hymn, sixteen bars of increasingly wider intervals. The initial hymn section segues into the Balladeer’s triple-time parlour song. The parlour song leads into a sixteen-bar cakewalk refrain for Guiteau, by the end of which he has danced himself one step closer to the hangman’s waiting noose. The upbeat character and tempo of the dance are reflected in Sondheim’s optimistic lyrics for Guiteau. Each refrain begins ‘Look on the bright side’ and continues with appropriately optimistic homilies that, along with the cheerfulness of the cakewalk, provide ironic contrast to the ominous scaffold on which they are delivered. The first two statements of the refrain are upbeat, but the third is slower, more resolute and accompanied by strong chords played on the beat, and ends abruptly after only four bars. At this point, Sondheim returns to the hymn. Now, however, it is played as a resolute and forceful dance: a danse macabre. At the end of the forceful hymn section, the Balladeer begins his refrain, this time in the previous fast tempo, and he and Guiteau sing an extended ending. As the refrain and the number are finally allowed to conclude, Guiteau is blindfolded and, as the lights black out and the final chord is played, the Hangman pulls the lever that releases the trap door under Guiteau.

The implications of the cakewalk, of course, are fascinating. The dance was originally a dance of outsiders, created by plantation slaves as a means of ridiculing their white owners. It was theatrical from its conception, with its prancing, high steps, its forward and backward bowing and its practice of dressing up in costume to impersonate others. Later, when the cakewalk was included in minstrelsy, it included acknowledgement of the audience. The cakewalk was eventually accepted by all of society, and it became quite popular with American and European dancers, white as well as black. Guiteau’s self-consciously theatrical performance of the number recalls the cakewalk of minstrelsy and its winks and bows to the audience, and the absurdity of its urgent cheerfulness, under the circumstances of its performance, suggests Guiteau’s insanity. The changing reception of the cakewalk, furthermore, suggests Guiteau’s desperate desire for the respectability he thought fame and success would bring. Interestingly, the nature of the cakewalk, in its origins and later as a popular dance, was competitive. The slave who best impersonated the masters was rewarded with a prize – a cake – and later dancers also competed for prizes and acclaim. In Assassins, the disenfranchised seek a prize withheld by society, and their increasingly angry demand for that prize culminates in the powerful musical number ‘Another National Anthem’. Guiteau’s cakewalk simply and subtly drives home the idea that he, like each of the characters, is waiting for a prize, but not necessarily the noose and trap door.

The skill demonstrated in the creation of these two musical numbers suggests why Stephen Sondheim is among the most accomplished and influential composer-lyricists of the American musical theatre. His mastery of the styles that inform the score for Assassins is nothing less than stunning, and each musical number displays a virtuosity similar to that found in ‘How I Saved Roosevelt’ and ‘The Ballad of Guiteau’. Even the musical interludes refer to music other than that in Assassins and at one point are self-referential: Samuel Byck’s first monologue, a humourous if unsettling message to Leonard Bernstein dictated into a tape recorder, ends with Byck singing Sondheim’s lyrics to ‘America’ from West Side Story. Sondheim then parodies Bernstein’s music for ‘America’ to close the scene. First quoting the number and then paraphrasing it, Sondheim uses his own work as a historical source. The moment is as chilling and ironic as it is amusing. Later, before the scene in the Texas School Book Depository, Sondheim uses actual recorded music – The Blue Ridge Boys singing ‘Heartache Serenade’ – to give the scene an especially eerie sense of reality that is made surreal when John Wilkes Booth appears before Lee Harvey Oswald.

Drawing on the body of American popular culture to give voice to the characters as well as to make critical commentary about them, Sondheim leaves the audience with the act of assassination as a collective cultural memory that uncomfortably lingers. The bitter observations of ‘Gun Song’, for instance, have the capability to haunt the viewer long after the final curtain. The communal desperation of ‘Another National Anthem’ fades into the quieter desperation of Lee Harvey Oswald, whose violent act, still vivid in the minds of many in the audience, is the climax of the show. There is no song for Oswald because his feelings have already been anticipated and expressed: he is the culmination of all the assassins and all the songs that have gone before him. Of course, he too is the victim of assassination, an act that provokes the final chorus of ‘Everybody’s got the right to be happy’.

This one score, perhaps the most indigenously ‘American’ of all Sondheim’s output given its sources, displays a master at a high point of his career. Assassins is representative of Sondheim’s work in its use of pastiche, its experiment with form and its representation of outsiders looking at a society that, for whatever various reasons, excludes them.

In all his work, Sondheim’s musical languages are varied yet identifiably his own; perhaps they are more like different accents of the same language than altogether different languages. His harmonic vocabulary is vast and he alters it somewhat with each project; but the end result is always recognisably his.20 His musical treatment, as well as the vocabulary of the lyrics in his own scores (Sondheim has criticised some of his earlier lyrics as inappropriate),21 displays an unerring sense of character as well as theatricality, and no false note or word appears in any of his mature work.22 Returning to his scores again and again, the listener is continually informed, surprised and entertained by them. In Assassins Sondheim’s musical pastiche is a tool for revealing aspects of the American national psyche, including the American proclivity for assassinating elected leaders. The initial and nervous critical reception of Assassins in the United States perhaps suggests that Sondheim reveals too much too clearly. Each of his works operates in similar, although outwardly different, ways.

The sensitivity that caused the fifteen-year-old Stephen Sondheim to cry at the first-act curtain of Carousel is still present in his maturity. Sweeney Todd, Into the Woods, Assassins and Passion are each as heartbreaking as they are disturbing and amusing. In Assassins Sondheim’s outsiders find a national anthem for all the ‘others’ as well as for themselves in a musical score of inordinate richness. In musical after musical Sondheim offers a moving reminder about those people who ‘can’t get in to the ball park’, and he offers this reminder in a most American way: through the voice of America’s own songs.

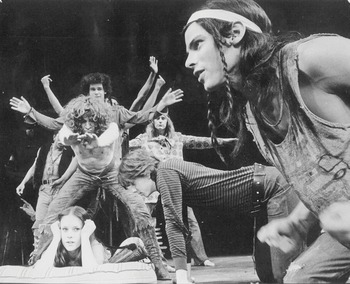

Can one recapture the excitement that A Chorus Line brought to Broadway? The Broadway musical seemed moribund in the middle of the 1970s. The big hits of the previous decade, such as Hello, Dolly!, Fiddler on the Roof and Man of La Mancha, had closed and the era of the great musical plays that followed the Rodgers and Hammerstein model was over. Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince combined for major artistic successes between 1970 and 1973 with Company, A Little Night Music and Follies, but their appeal was limited, as can be seen by the length of their runs and mixed commercial success. The rock musical had become a Broadway reality with Hair, Two Gentlemen of Verona and other shows, but rock was a new musical language that many in the traditional Broadway audience had not yet accepted. Creators of the musical theatre searched for a new mould that might combine new musical styles and contemporary thinking with tradition, building upon the genre’s proud history. A Chorus Line did all of this as a veritable celebration of Broadway dance and dancers, bringing new life to the genre and taking it into the colossal hit era of 6,000-performance runs.

Those who saw A Chorus Line during its original run will not easily forget it. The plot was minimal and somewhat artificial, but the characters were engrossing. We recognised types of people that we knew and with each part of their stories our fascination grew. The singing and dancing had a special immediacy because, within the world that the director Michael Bennett magically created, we knew that these characters would express themselves through music and movement.

The creators of A Chorus Line built upon decades of Broadway history when dance was integrated into the musical as a crucial part of character development and dramatic impact. It had taken years in musical comedy to integrate plot and significant aspects of the music, but by the time of Show Boat (1927) and Of Thee I Sing (1931), song placement had become more careful in some shows and plots sometimes advanced during songs. Although this trend could hardly be described as linear, by the time Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote Carousel (1945), songs were often an important part of the plot, and extended musical sequences were more common.

The integration of dance with a show’s plot was a slower process. Victor Herbert, a Broadway pioneer in several areas, wrote some of the first dance musicals, such as The Lady of the Slipper (1912).1 In such shows, Herbert used dance for spectacular effect and throughout entire scenes, surpassing its more common use for variety. The famous team of Vernon and Irene Castle was hired to show the latest ballroom steps, but they were dismissed in Philadelphia because part of their work seemed too suggestive. During the 1920s dances would follow a song, and various stage personalities offered dance specialties that had nothing to do with the plot. For example, according to Hugh Fordin, the Sunny star Marilyn Miller interrupted Oscar Hammerstein II as he described the plot, wondering when she would do her specialty tap number.2 There were a number of fine dancers on Broadway in the 1920s, including Fred and Adele Astaire, Ann Pennington and Marilyn Miller, who helped introduce dance as a way of describing their characters, but for the most part dance remained part of the musical’s quest for variety. Most shows included dances added solely for entertainment; A Connecticut Yankee and Show Boat were two exceptions. Dances designed by such leading choreographers as a Busby Berkeley were fairly predictable and resulted only in the credit line ‘dances by’.3

As Hollywood musicals appeared and confirmed the public’s interest in watching stars dance (perhaps a metaphor for what could not be shown), Broadway followed suit. Ethan Mordden describes the continued development of the character dance in ‘Clifton Webb’s unassuming soft shoe or Tamara Geva’s ballet glide’ and the continued popularity of the kick line.4 (The latter, of course, never died; A Chorus Line exploited the appeal of the long, shapely female leg and a line’s drilled precision.) By the second half of the 1930s, however, more ambitious dances appeared in shows, first and most famously in On Your Toes (1936), with a score by Rodgers and Hart and direction by George Abbott. George Balanchine, the famed Russian choreographer, worked on the show and was the first honoured with the credit line ‘choreography by’. His major contribution was the ballet ‘Slaughter on Tenth Avenue’, danced by Ray Bolger, Tamara Geva and George Church. Abbott remembered the segment as ‘one of the best numbers I’ve ever seen in the theatre, both musically and choreographically’.5 The show also included an intentionally over-the-top ballet in the first act, ‘Princess Zenobia’. The dances were part of a story about a vaudeville hoofer trying to make it in ballet. The dances were praised at the time, but, as Marian Monta Smith has noted, they were seen as an exception and the production had little immediate influence.6 Balanchine continued to work on Broadway into the 1950s, but there are few other shows for which his choreography had a lasting influence.7

It seems significant that George Abbott directed On Your Toes, because he went on to be a major influence on the continuing integration of the musical and on two important choreographers who later became directors. As extensive use of dance became part of the musical, the director emerged as the figure who assembled the show’s elements into a creative whole. By the 1960s, several of the most important directors were choreographers. Two of these, Jerome Robbins and Bob Fosse, worked with Abbott and learned to direct the book from him. The line continues with Hal Prince, who, although not a choreographer, also explored the musical’s greater integration. He began his Broadway career working for Abbott in the early 1950s and learned direction from both Abbott and Robbins.

The greater integration of dance, specifically ballet, into the musical required the willing cooperation of Broadway creators and understanding talent from the ballet world, a combination that came together in Oklahoma! Rodgers, Hammerstein and the producers Theresa Helburn and Lawrence Langner of the Theatre Guild sought to make ballet part of the show’s plot apparatus and hired Agnes de Mille as choreographer. She had handled Western themes with her 1942 ballet Rodeo, with music by Aaron Copland. De Mille’s work in Oklahoma! is legendary, from her insistence on real dancers and separate rehearsals to her battles with the director, Rouben Mamoulian.8 Such dances as ‘Laurey Makes Up Her Mind’ at the end of the first act changed Broadway history. De Mille’s dancers served as substitutes for most of the principal actors during the ballet and helped make convincing the notion of Laurie dreaming her way to a choice between Curley and Jud. De Mille’s use of counterpoint in her ballets, with characters doing different movements at the same time, added to the visual appeal.9

Broadway creators are nothing if not imitative, and several immediately capitalised on the new idea of taking the highbrow art of ballet into the middlebrow world of the Broadway musical. De Mille played a major role throughout the 1940s. She next worked on One Touch of Venus (1943), with music by Kurt Weill and lyrics by Ogden Nash, who coauthored the book with S. J. Perelman. A show about Venus coming to life invited fanciful ballets. De Mille contributed ‘Forty Minutes for Lunch’ in the first act, where Venus meets New York workers in Rockefeller Center, and ‘Venus in Ozone Heights’ as the second act’s dream ballet, where the goddess discovers suburbia. De Mille went on to Bloomer Girl (1944), with music by Harold Arlen and lyrics by E. Y. Harburg, where she contributed a ballet based on an ‘Uncle Tom’ show and a Civil War ballet in which female dancers expressed the feelings of those watching husbands and sons go off to war.

De Mille returned to work with Rodgers and Hammerstein as choreographer for Carousel, where her dances again played a major role in plot development. The opening ballet-pantomime introduces the setting and mood, and in the second-act dance, Billy Bigelow’s daughter expresses her frustration. De Mille next choreographed Brigadoon, Lerner and Loewe’s breakthrough hit, including atmospheric Scottish dances and the chase ballet in the second act. De Mille became the first choreographer-director in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Allegro (1947), where she tried to unify a rambling plot, a singing Greek chorus and many musical numbers calling for motion. She included a fantasy ballet where, in a manner reminiscent of Our Town, characters both living and dead appear. The show would have challenged any director, but it did give de Mille a chance to develop comfort with all types of stage motion.

Agnes de Mille’s peers, who helped dance become a more important part of the Broadway musical, included, among others, Jack Cole, Michael Kidd and Jerome Robbins. Cole helped establish the Broadway vernacular dance tradition with his imaginative use of steps from ethnic and ballroom dances and acrobatics, often set to big band music.10 He also added ballets to shows, such as his slow-motion softball game in Allah Be Praised (1944). Michael Kidd choreographed Finian’s Rainbow (1947), Guys and Dolls (1950) and Can-Can (1953), showing an admirable range; his major success as a choreographer-director was Li’l Abner (1956). Jerome Robbins, one of Broadway’s most important choreographers, was the first dancer to become a truly successful director.

Jerome Robbins straddled ballet and Broadway for much of his career, but worked little on Broadway from the mid-1960s to the 1980s. His first major ballet was the popular Fancy Free in 1944, created with the composer Leonard Bernstein. They brought the ballet’s energy, references to vernacular music and dance and a plot concerning three sailors on leave in wartime New York City to Broadway in On the Town, which also involved the lyricists and book writers Betty Comden and Adolph Green and director George Abbott. Much about the show was memorable (see Chapter 11), especially its frenetic energy and constant motion. In her autobiography Distant Dances, Sono Osato, a ballet dancer who played Ivy Turnstiles, describes her work with Abbott and Robbins.11 Abbott directed the book scenes, but Robbins had a free hand with the dances. The two major ballets were ‘Miss Turnstiles’ and ‘Gabey in the Playground of the Rich’, the latter a dream ballet near the end of the show. Both helped propel the story. Osato danced the latter ballet with a dancer substituting for the actor who played Gabey. Abbott allowed Robbins to show how dance could be incorporated in varied situations, helping lead finally to shows such as West Side Story.

Robbins continued to work on Broadway as well as in ballet and modern dance. In 1945 he contributed the ballet ‘Interplay’, with music by Morton Gould, to the vaudeville Concert Varieties.12 In December of that year, Billion Dollar Baby opened, starring the dancer Joan McCracken with choreography by Robbins. Far more famous is Robbins’s work with George Abbott during the 1947–48 season, including High Button Shoes (1947) and Look, Ma, I’m Dancin (1948). Abbott directed and wrote High Button Shoes, a fast-paced farce built around Phil Silvers. The score was Jule Styne’s first for Broadway. He considered himself a songwriter, but Robbins convinced him to score the ‘Mack Sennett Ballet’, where Keystone Kops and a bear chased the leads. All finally land in a pile topped by a flag-waving policeman. The number was repeated in the retrospective Jerome Robbins’ Broadway (1989). Look, Ma I’m Dancin was a vehicle for Nancy Walker conceived by Robbins. Walker played a brewery heiress who becomes a patron for a ballet company and finally dances with it, a hilarious possibility given her clowning skills. Robbins’s ‘Sleepwalker’s Ballet’ was one of the highlights in a show that ran for only six months because of Walker’s ill health. Robbins also worked with Abbott on Call Me Madam, a vehicle for Ethel Merman with a score by Irving Berlin, but the show is remembered more for its star and score than for its dancing. Abbott reports that Robbins started rehearsals early to create his dances, but the major number was removed before opening night. Abbott reveals his faith in spoken materials, predictable for one of the genre’s best book directors: ‘Time and time again the ambitious dance effort will fail, whereas something conceived for practical purposes and on the spur of the moment will be a success. This is equally true of songs.’13 Abbott’s type of show, the fast-paced comedy, however, was in decline, as dance became a more integral part of the musical.

In 1951 The King and I opened, a much-loved show by Rodgers and Hammerstein that included Robbins’s lengthy ballet ‘The Small House of Uncle Thomas’, which offers interesting commentary on the plot’s theme of East meeting West. The dance also appeared in Jerome Robbins’ Broadway.

In 1954 Abbott gave Robbins billing as co-director for The Pajama Game (considered later), partly because of his success at working with such dancers as the star Carol Haney. The show’s choreographer was Bob Fosse, and other important newcomers to Abbott’s team were the producers Hal Prince and Robert E. Griffith, who later produced West Side Story.

Robbins earned his first full credit as a Broadway director in Bells Are Ringing, a show with little important dancing, music by Jule Styne, lyrics by Comden and Green and a delightful star in Judy Holliday. It ran for two years. At this point Robbins was ready to spread his wings by taking on both direction and choreography. He realised this ambition the following year with West Side Story.

West Side Story (1957) marks the full integration of dance into the Broadway musical and the true arrival of the choreographer-director. Plans for a modern version of Romeo and Juliet involving Robbins, Bernstein and Arthur Laurents had started as early as 1949.14 Their original thought was that the lovers should be Catholic and Jewish and the story should occur around the time of Easter and Passover, but they were unable to work together with any consistency and the project was shelved. Bernstein and Laurents ran into each other in Beverly Hills in August 1955 and decided to move the story to New York’s West Side and pit gangs of Puerto Ricans against the white ‘Americans’.15

As director and choreographer, Robbins was responsible ultimately for the full integration of each element into a dramatic whole. He believed in method acting, dividing the cast into the two gangs and forbidding them to socialise on the set. His intensity in rehearsal was legendary. Carol Lawrence, who played Maria, remembers working with Robbins: ‘You have to understand that Jerry Robbins was the motivating force in all of this. He was the eternal perfectionist. The fact that one can never attain perfection did not deter him for a second. That was what he wanted and if he ended up killing you in the interim, well that was okay too!’16

West Side Story was cast from a pool of dancers. Even the romantic leads, Carol Lawrence and Larry Kert, had extensive dance training. In effect, Robbins choreographed every movement in the show. Dance provided motion in the action sequences (such as in the ‘Prologue’ and ‘The Rumble’), and served as an expressive device both for inarticulate characters (‘Dance at the Gym’ and ‘Cool’) and in numbers designed to release tension (such as in ‘I Feel Pretty’ and ‘Gee, Officer Krupke!’).17 How dependent the show was on dance became clear when the company arrived at the Washington theatre for its out-of-town try-out and discovered that the stage was significantly smaller than at the Winter Garden in New York, for which it was choreographed. Carol Lawrence remembers that Robbins had to rework the ballets and ‘there was so much dance, almost nothing but dance in the show.’18

Bernstein wrote the dance numbers as well as the songs. Robbins was a close collaborator, often suggesting musical changes and at times making them himself. Bernstein showed notable command of Latin dances and various types of jazz, producing a score that still sounds contemporary. Especially effective moments include the mambo in the ‘Dance at the Gym’ and the rich references to cool jazz in the song ‘Cool’. Bernstein uses melodies from the songs in dance sequences to great dramatic effect, such as the tune ‘Maria’ in the ‘Maria Cha-Cha’ of the ‘Dance at the Gym’ sequence, heard there before Tony sings the song for the first time. The song ‘Somewhere’ also appears in dance passages, tying the dream sequence between Tony and Maria to the show’s plot.19

West Side Story was Bernstein’s last important Broadway show, but Robbins continued to work there consistently into the mid-1960s. Two of his West Side Story collaborators – Arthur Laurents and Stephen Sondheim – joined the composer Jule Styne on Gypsy in 1959. Choreography was far less important here than in some of his previous shows, but Robbins again showed his deft staging touch, beautifully evoking vaudeville and burlesque while allowing room for one of Ethel Merman’s greatest roles. His next show was Fiddler on the Roof (1964), another triumph of mood and atmosphere in a book musical. Along with the set designer Boris Aronson and the costume designer Patricia Zipprodt, Robbins convincingly recreated the Jewish shtetl of Anatevka. Robbins designed some of his most imaginative dances, using both Jewish and Russian elements to add to the show’s true-to-life quality. Two memorable sequences included a joint dance by Jewish and Russian characters in the inn and the bottle dance at the wedding. Robbins’s next, and last, Broadway show was the anthology Jerome Robbins’ Broadway of 1989.

The next great choreographer-director in the line of Agnes de Mille and Jerome Robbins was Bob Fosse (1927–87), a dancer from Chicago who began his career in vaudeville and burlesque.20 As noted earlier, George Abbott was important to Fosse’s career development, hiring him as choreographer in The Pajama Game (1954). Unlike Robbins, Fosse came to Broadway through the world of ballroom and ethnic dances, showing the influence of Jack Cole’s jazz-dancing techniques. Fosse’s dances for The Pajama Game, especially in ‘Hernando’s Hideaway’, kept up the frenetic pace popularised by Abbott and Robbins. For the star Carol Haney, with whom Fosse had worked in Hollywood, he created ‘Steam Heat’, which she danced with Peter Gennaro and Buzz Miller. The show bubbled over with major dance numbers, including ‘Once a Year Day’, ‘7½ Cents’, and ‘I’ll Never Be Jealous Again’. Fosse also worked with Abbott in Damn Yankees (1955), which included a number of dances based upon typical baseball moves and ‘Who’s Got the Pain?’, conceived for Gwen Verdon, Fosse’s third wife and frequent collaborator. Fosse also worked on the film versions of The Pajama Game (1957) and Damn Yankees (1958). In 1956 Fosse assisted Robbins with the choreography for the Broadway show Bells Are Ringing, including the number ‘Mu Cha Cha’. Fosse’s last show with Abbott was New Girl in Town (1957): their break-up was caused by Abbott’s moral objections to Fosse’s dream ballet in a bordello. Fosse often cultivated the suggestive in his dance routines, perhaps an influence from his days in burlesque. Christine Colby Jacques, a dancer who worked with Fosse on Dancin’, notes that he often ironically parodied suggestive movements:

The ‘American Women’ section in Dancin (1978), presented three women with long-stemmed roses in their mouths. With hips thrust forward, hands on hips and elbows squeezed together in back, they took three long, exaggerated steps across the stage. Their feet came together, and looking over their shoulders out toward the audience, each woman swayed her hips side to side ever so slightly in an up, even tempo. The impact was a clear, yet comical comment on the pouting and sensual manner women sometimes use to manipulate men. So much of Fosse’s choreography reflects a tongue-in-cheek look at ourselves, whether it’s sensual movement or gestural movement … Fosse directed us to think of ourselves as little girls with sway backs and protruding little bellies, sucking our thumbs.21

Fosse became Broadway’s third important choreographer-director in the late 1950s, starting with Redhead (1959), a vehicle for Gwen Verdon, including the dances ‘Pick-Pocket Tango’ and ‘The Uncle Sam Rag’. Fosse shared director’s credit with Abe Burrows in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (1961), where Fosse did the ‘musical staging’.

Fosse’s next show was Little Me (1962), starring Sid Caesar. Among the dances was the effective ‘Rich Kid’s Rag’. His next major work was for Gwen Verdon in Sweet Charity (1966), which Fosse conceived, directed and choreographed. His dances included ‘I’m a Brass Band’ for Gwen Verdon (with the male chorus performing his trademark posture of locked ankles and a backward lean), ‘Big Spender’ for the hostesses at the Fandango Club and ‘The Rich Man’s Frug’, a satire of recent dance fads in discothèques. Fosse struggled through the film version of Sweet Charity, but resurrected his career by directing the highly successful film adaptation of Cabaret (1972), winning the Oscar for best direction. He also directed and choreographed the film All That Jazz (1979), which many considered Fosse’s autobiography and included brilliant dancing segments.

Fosse’s last three Broadway shows included some of his most popular work. Pippin (1972) had an anemic plot, enlivened by Fosse with characters based upon commedia dell’arte clowns and several large-scale song and dance numbers, and assisted greatly by the energy and gregarious personality of Ben Vereen. Chicago (1975) was yet another show starring Gwen Verdon, joined by Chita Rivera. They played murderesses who form a nightclub act. Fosse’s staging was lean and effective with dance an integral part, led by Verdon and Rivera, who allowed Fosse to parody their fading youth in brief costumes and suggestive poses. The show is a series of vaudeville acts, each advancing the plot, with a band on stage. Fosse’s choreography made frequent use of the soft-shoe and Charleston, emphasising the 1920s setting. Dancin’ (1978) was Fosse’s answer to A Chorus Line: another show about dancing conceived in a workshop situation. Using music by many composers dating back to Bach, Dancin’ includes no plot and little singing. Critics offered mixed reactions but the audience did not, propelling Dancin’ to a run of 1,774 performances. The show was a monument to Fosse the entertainer and his eleventh Broadway hit in a row. His final Broadway show was the unsuccessful Big Deal (1986). A retrospective of Fosse’s work, Fosse, ran on Broadway and in the West End and toured in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Richard Maltby Jr, Ann Reinking and Chet Walker conceived it with the assistance of Gwen Verdon. Reinking has had a successful career as a choreographer, for example, following Fosse’s work in the hit revival of Chicago that ran for years on Broadway (starting in 1996) and in the West End (starting in 1997).

Another of Broadway’s important choreographer-directors was Gower Champion, who started as a Broadway dancer in the 1940s. He went to work in Hollywood, and then returned to Broadway as choreographer-director of Bye Bye Birdie (1960), a fairly simple show whose major dance was the wild ‘Shriners’ Ballet’. His next show was Carnival (1961), where Champion brought the audience into the action by dispensing with the curtain and using aisles for entrances and exits. The memorable choreography included the ‘Grand Imperial Cirque de Paris’. Champion’s biggest hit was Hello, Dolly! (1964). Although more famous for the title song and Carol Channing’s inimitable presence, the show benefitted enormously from Champion’s staging, which included extensive business from the dancers. He made Channing the centrepiece whenever possible and crafted one of the greatest entrances in theatre history with the hilarious ‘Waiter’s Gavotte’ before Dolly Levi descends the stairs at the Harmonia Gardens (see illustration in Chapter 10). The extensive use of choreography was also found in ‘It Takes a Woman’ and ‘Before the Parade Passes By’. Champion’s career continued for another fifteen years with both hits and flops, including I Do! I Do! (1966), The Act (1977) and 42nd Street (1980). The latter was an unabashed return to the days of tap-dancing chorus complete with story and music from the 1933 movie by the same name. Champion died the day the show opened.

Although not a choreographer-director, Hal Prince has played a major role in the development of the musical since the 1950s.22 Like Robbins, he learned his craft from George Abbott. He played a role in several of Abbott’s shows during the 1950s and emerged from the older man’s shadow when he produced West Side Story with Robert E. Griffith in 1957. Following Griffith’s death in 1961, Prince produced such shows as She Loves Me (1963) and Fiddler on the Roof (1964). He made his directing debut with Cabaret (1966), a book show that he treated like a concept musical, with an inspired staging that commented on the story through the cabaret entertainment. Its run of 1,166 performances did much to establish Prince as one of the most sought-after new directors. In 1970 he began his artistically successful collaboration in concept musicals with Stephen Sondheim in Company (1970), Follies (1971) and A Little Night Music (1973), three shows without conventional plots where staging played a huge role. Prince pushed staging nearly to extreme limits in Follies, helping to create the spectacular effect of a theatre crumbling, but at the same time losing $685,000 during the one-and-a-half-year run. In the 1980s and 1990s, Prince worked on some of Broadway’s biggest successes with scores by Andrew Lloyd Webber, but his artistic vision had the most influence in the 1960s and 1970s, when he played a major role in the continuing integration of music, dance and drama in the musical. Like Robbins, he wielded great power in a production and helped make the director one of Broadway’s most important figures.

The next important choreographer-director was Michael Bennett, creator of A Chorus Line. From a young age he showed great interest in dance and made his professional debut while still in his teens in a stock production of West Side Story. He later toured Europe in the show and became intimately familiar with his idol Robbins’s work. Bennett became a Broadway gypsy in the early 1960s but worked in no memorable shows. He choreographed stock productions and achieved his first Broadway credit in A Joyful Noise (1966), which ran for twelve performances.23 Critics praised Bennett’s work, as they did his dances for Henry, Sweet Henry (1967), also a flop. Bennett finally worked on a hit in Promises, Promises (1968), directed by Robert Moore. The final version of the show included only one major dance number, but, as Ken Mandelbaum reports, ‘Bennett was able to make an enormous contribution to the show by weaving scene into scene, staging marvelous “crossovers”, with secretaries spinning through revolving doors in stylised movements reminiscent of … “go-go” steps.’24 Promises, Promises was the first show where Donna McKechnie was Bennett’s principal female dancer. She eventually became for Bennett what Gwen Verdon was to Bob Fosse. Bennett and McKechnie were also married for a time.

Bennett’s next show as choreographer was Coco (1969), a vehicle for Katherine Hepburn directed by Michael Benthall. With both star and director working on their first musical, Bennett’s role was very large. He choreographed dances around a largely stationary, charismatic star and worked on book scenes; Mandelbaum called Coco Bennett’s ‘unofficial directorial debut’.25 He gained valuable experience in the concept musical Company (1970), working with Hal Prince. Bennett had considerable influence on the show’s staging, especially in the musical numbers, such as ‘You Could Drive A Person Crazy’, ‘Side By Side By Side’, ‘What We Would Do Without You’ and ‘Tick Tock’, Donna McKechnie’s memorable solo dance. Bennett wanted to direct, but worked with Prince on Follies (1971), this time billed as co-director. Reviewers recognised his important contribution to the show’s staging, especially in numbers like ‘Who’s That Woman?’ Walter Kerr wrote in the Sunday Times: ‘Michael Bennett’s dazzling dance memories and perpetually musical staging are as seamlessly woven into [Sondheim’s musical] personality as they are into Prince’s immensely creative general direction.’26

Bennett had become highly regarded for his imaginative staging ideas and was ready to direct on his own. Before A Chorus Line he directed two non-musical plays and Seesaw (1973), a troubled musical that he took over in Detroit and brought to Broadway for a respectable ten-month run. Bennett received full artistic control over the show and brought in his usual assistant choreographer Bob Avian along with the dancers and choreographers Tommy Tune, Baayork Lee, Thommie Walsh and others, several of whom later worked in A Chorus Line. Seesaw had a successful national tour and made Bennett a major player in the Broadway community.

A Chorus Line started with Bennett’s inspiration to do a show about dancers, a group he did not believe received its due on Broadway.27 Along with Tony Stevens and Michon Peacock, with whom Bennett had worked in Seesaw, he arranged a meeting to discuss with eighteen colleagues on 18 January 1974. It was an extraordinary evening on which many felt moved to tell their life stories.28 Bennett recorded the tales, as well as the conversations at the second such session on 8 February. After initial work with the tapes by Stevens, Peacock and the dancer-writer Nicholas Dante (whose story became the character Paul in the show), Bennett bought the rights to the raw material for A Chorus Line.

Bennett, Avian and Dante held more interviews and framed the show as an audition where dancers were encouraged to tell their stories. Early in the process Bennett decided to cast the show before even writing it and sold the workshop idea to Joseph Papp of the New York Shakespeare Festival. Papp agreed to pay Bennett and the dancers each $100 per week and let them work in his Newman Theater. Workshops had been used in plays for years, but A Chorus Line was the first musical produced through this method.

Bennett assembled his creative team. The co-writers were Bennett and Dante. Marvin Hamlisch became the composer and Edward Kleban the lyricist, both writing songs in the workshop. The first workshop, beginning in August 1974, lasted five weeks of fourteen-hour days, and after auditions included several of Bennett’s favourite dancers. At the end of the workshop, however, they had only staged a few numbers. A second workshop began in late December, for which Bennett brought in writer James Kirkwood to help Dante with the script. The second workshop yielded a workable show. Kirkwood recalled the process:

The material – book, music, lyrics, and staging concepts – changed daily … the show became structured and focused. The key to this was the invention of the character of Zach. In the first workshop, there had been an amorphous God-like figure billed only as ‘Voice.’ There was now an actual director character leading the audition, one who would soon be given a past involving one or more of the characters.29

Along with the character Zach came Cassie, his ex-lover, a small plot around which the remainder of the show could form. The workshop was highly collaborative, contributing to the final product’s seamlessness. It is impossible to sort out who was responsible for each contribution. For example, Bennett often asked another dancer, such as Avian, McKechnie or Baayork Lee, to design steps that he could edit.

Formal rehearsals began in March 1975 with the first preview on 16 April 1975. The buzz around Broadway was that the show was a sure hit, and tickets at the tiny Newman Theater (299 seats) were scarce. The public remained infatuated with the show through the official off-Broadway opening on 21 May 1975 and the move to the Shubert Theatre for its Broadway opening on 19 October 1975. A Chorus Line ran for fifteen years, paving the way for the megamusicals of the 1980s and 1990s, but without the huge stage effects that mark many of those shows.

Bennett brought to A Chorus Line rich Broadway experience as a dancer, choreographer and director, and the vision to forge an unconventional show. Placing the story in the context of an audition gave the audience the feeling of peeking backstage, even though the device was essentially unrealistic. Of course no Broadway director would have cared about the life stories of auditioning dancers, but these real-life vignettes did help to give the show a sense of truth.

Although some of his signature numbers in other shows involved elaborate costumes and sets, Bennett realised that A Chorus Line would work best with a nearly bare stage and rehearsal clothes as costumes. He satisfied the audience’s craving for Broadway glitz in the closing number, ‘One’, performed by the entire cast in full costume, but that seemed appropriate because the chorus had been chosen and it was time for the show to open. What is missing in the closing number is the star behind whom one assumes the chorus might be dancing.

The show’s intensity came from its rapid pace and lack of intermission. In earlier shows Bennett had used ‘cinematic’ techniques of directing, fading from one scene to another through action on stage, as in the dancing secretaries between scenes in Promises, Promises. Such continuity and rapid pacing have long been part of the musical comedy, and were a major part of George Abbott’s work in the 1930s. Prince and Bennett used the technique in Follies, and in A Chorus Line one finds its full realisation. The curtain never does go down during the show. Bennett had found success with montage scenes before, and designed his masterpiece in the long ‘Hello Twelve, Hello Thirteen, Hello Love’ (Martin Gottfried notes that it is one-fifth of the length of the script30), where the characters explore the pains of adolescence. Much of the show’s action seems to occur in real time, a huge tribute to Bennett’s direction.

Another major factor in the show’s success is its saturation with dance and the various levels at which the audience perceives the dancing. One expects dancers to demonstrate their talent at an audition, so the audience accepts it as the show’s basic language and revels in watching those auditioning learn the steps, some succeeding and others cursing their efforts. Dance enters the characters’ stories as they are told, such as the delightful tap dance ‘I Can Do That’, in which Mike tells of his early and natural talent. Finally, dance allows characters to express deeper feelings, especially Cassie in ‘The Music and the Mirror’, McKechnie’s memorable solo number in which she shows that Cassie has the talent to be a solo dancer, even if that career has not worked out. Soon thereafter, the audience learns the difference between solo and chorus dancing, as Zach berates her for not dancing in unison with the others.31

Sometimes lost in the excitement about the show is the music, but this is partly because of the convincing way that songs and dance music are integrated with the rest of the show. In an essentially plotless musical a song cannot advance the narrative, but it can fit in with the dramatic concept of the moment, and all songs do. Most help tell a character’s story, the only real exceptions being ‘What I Did For Love’ and ‘One’. Some have criticised ‘What I Did For Love’ as Marvin Hamlisch’s crass attempt at a hit song. The lyricist, Edward Kleban, hated it and wanted something different,32 but the song is meaningful. After telling the most dramatic story of any of the characters, Paul falls and re-injures a knee. His career might be over. Zach asks the dancers what they will do when they can no longer dance. Diana’s reaction is this song, which, in the musical language of a 1970s pop anthem, answers the question by stating that one works for love of the art.