INTRODUCTION

Despite more than a century of archaeology in Belize and the central Maya lowlands, many aspects of the past in this part of Mesoamerica still elude us and continue to provoke lively discussions. Among the most pressing, perplexing, and debated topics are those related to the first humans in these regions and the appearance of the first people who can be called “Maya.” To assist in addressing these topics, in addition to other questions concerning the preceramic and early ceramic-using people of Belize and the central Maya lowlands, seven articles in this Special Section, titled “The Preceramic and Early Ceramic Periods in Belize and the Central Maya Lowlands,” summarize and expand upon much of what we currently know about the first humans and the first Maya.

This introduction to the Special Section provides a brief summary of early research into the preceramic in Belize and the central Maya lowlands (the term “preceramic” is used to refer to all periods before the appearance of pottery rather than Iceland's [Reference Iceland1997:177, 204] specific Late Archaic phases). It also provides a current chronology used by archaeologists to define the Paleoindian through the Terminal Early to Early Middle Preclassic periods and discusses significant aspects of both the preceramic and early ceramic people in Belize and the central Maya lowlands. For the Paleoindian and Archaic periods, a brief discussion of early human remains and aDNA is provided, followed by a summary of preceramic lithic technology, subsistence strategies of preceramic peoples (including early cultigens), occupation patterns, lithic production locales, and possible evidence for early ritual behavior. Evidence associated with the appearance of the first Maya in these regions is discussed in terms of archaeological remains and language. Notably, our consideration of archaeological evidence for the first Maya includes early horticulture, specifically involving maize, the first appearance of ceramics, early traces of villages, evidence for increases in both socioeconomic and ideological complexity, and traces of emerging social inequality. The transition from proto-Mayan to early Mayan languages is explored using multiple lines of evidence to demonstrate the connections of the Mayan lexicon to the preceramic past, including early food production and domesticates. In light of the current archaeological and linguistic information about the Maya, we summarize various explanations for the origins of the earliest Mayan speakers and their diverse connections to preceramic people.

EARLY RESEARCH AND THE PRECERAMIC IN BELIZE AND THE CENTRAL MAYA LOWLANDS

Prior to the 1980s, there was minimal evidence for preceramic people in the central Maya lowlands (MacNeish and Nelken-Terner Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983a; Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin1984). What little was known of the Paleoindian and Archaic was based on a few fluted points and scatters of chipped stone from the highlands of Guatemala and Honduras, most of questionable date (e.g., Brown Reference Brown1980; Coe Reference Coe1960; Gruhn et al. Reference Gruhn, Bryan and Nance1977; Hayden Reference Hayden1980). Concerning the paucity of evidence for a preceramic in the Maya lowlands, Marcus (Reference Marcus1983:457) noted at the time:

While Maya archaeologists assumed the Lowlands must have been occupied in preceramic times, they did little to test this assumption during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s while preceramic sites were being excavated in Tamaulipas, Tehuacán, Oaxaca, the Grijalva Depression, and the Basin of Mexico.

Following four years of fieldwork in northern Belize in the early part of the 1980s, under the auspices of the Belize Archaic Archaeological Reconnaissance (BAAR) Project, MacNeish and Nelken-Terner (Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983a, Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983b) proposed a tentative six-phase preceramic sequence of stone tools for Belize. It began with the Late Paleoindian/Early Archaic Lowe-ha phase, which included fluted points and stemmed bifaces that were possibly as early as 9000 b.c. The subsequent Sand Hill phase (7500–6000 b.c.) also contained stemmed bifaces that are recognized as Lowe points today (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Shafer and Kelly1980; Kelly Reference Kelly1993). This early typology was built on seriation and included cultural phases with their own distinctive chipped and ground stone technologies that extended throughout the Archaic to as late as about 2000 b.c. Based on excavations at nine stratified sites, the testing of four sites, and the identification of about another 100 preceramic locations, there was much speculation by MacNeish and Nelken-Terner (Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983b:63; Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin1984) about the changes in settlement types, subsistence practices, and mobility of these earliest peoples over time. However, in the early 1980s, the possibility of a significant preceramic occupation in Belize and the BAAR typology were both met with some reservation:

It must be emphasized that this preceramic sequence is a seriation, with no single site having more than two components in stratigraphic superposition, and most sites consisting only of surface material. The interpretation of the sites as preceramic […] and the dynamic model interrelating the sites, are, although plausible, based at present mainly on artifact morphology and interregional analogy (Hammond Reference Hammond1982:355).

A main concern about the proposed BAAR chronology was its paucity of supporting radiocarbon dates. The work by BAAR overlapped with that of the Colha Project Regional Survey, which focused on areas within the Northern Belize Chert-bearing Zone (NBCZ), including Ladyville, Sand Hill, and Lowe Ranch (Figure 1; Hester et al. Reference Hester, Shafer and Kelly1980; Kelly Reference Kelly1993; Shafer et al. Reference Shafer, Hester, Kelly, Hester, Eaton and Shafer1980). The search for preceramic sites in the NBCZ continued from 1987 to the mid-1990s at Colha and the Kelly site, with the Colha Preceramic Project producing additional evidence for a Late Archaic presence in northern Belize, including stone tool production locations (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Iceland, Hudler and Shafer1996; Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Kelly Reference Kelly1993). Excavations and coring at sites in the region between the Río Hondo and New River of northern Belize revealed Archaic levels associated with chipped stone, notably a Lowe point and a constricted uniface, maize and manioc pollen, and evidence for deforestation (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996). As the work of Hester, Shafer, Kelly, and Iceland, among others, continued in northern Belize, there was increased awareness that the original BAAR sequence needed significant modification. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, excavations by Rosenswig and Masson (Reference Rosenswig and Masson2001; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2004, Reference Rosenswig2015; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014) demonstrated that preceramic human occupation was more widespread than previously known, including evidence for possible living floors. Although there was some mention of diagnostic artifacts, including a Lowe point and constricted adzes, in central Belize (see Iceland Reference Iceland1997), excavations into Archaic deposits occurred only in the mid-2000s, with the work of Lohse (Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007, Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006) at Actun Halal. Both Brown (M. K. Brown et al. Reference Brown, Jennifer Cochran and Mixter2011) and Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2017) also encountered preceramic lithic debitage in paleosols beneath Maya occupations in central Belize. Despite some surface finds (Stemp and Awe Reference Stemp and Awe2013; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Prufer and Helmke2016; Weintraub Reference Weintraub1994), preceramic occupations had been suspiciously absent in southern Belize. However, the work by Prufer (Reference Prufer2018; Prufer and Kennett Reference Prufer, Kennett, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019, Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021) in three rockshelters south of the Maya Mountains has provided some of the oldest dated deposits with stone tools and human remains in the central Maya lowlands.

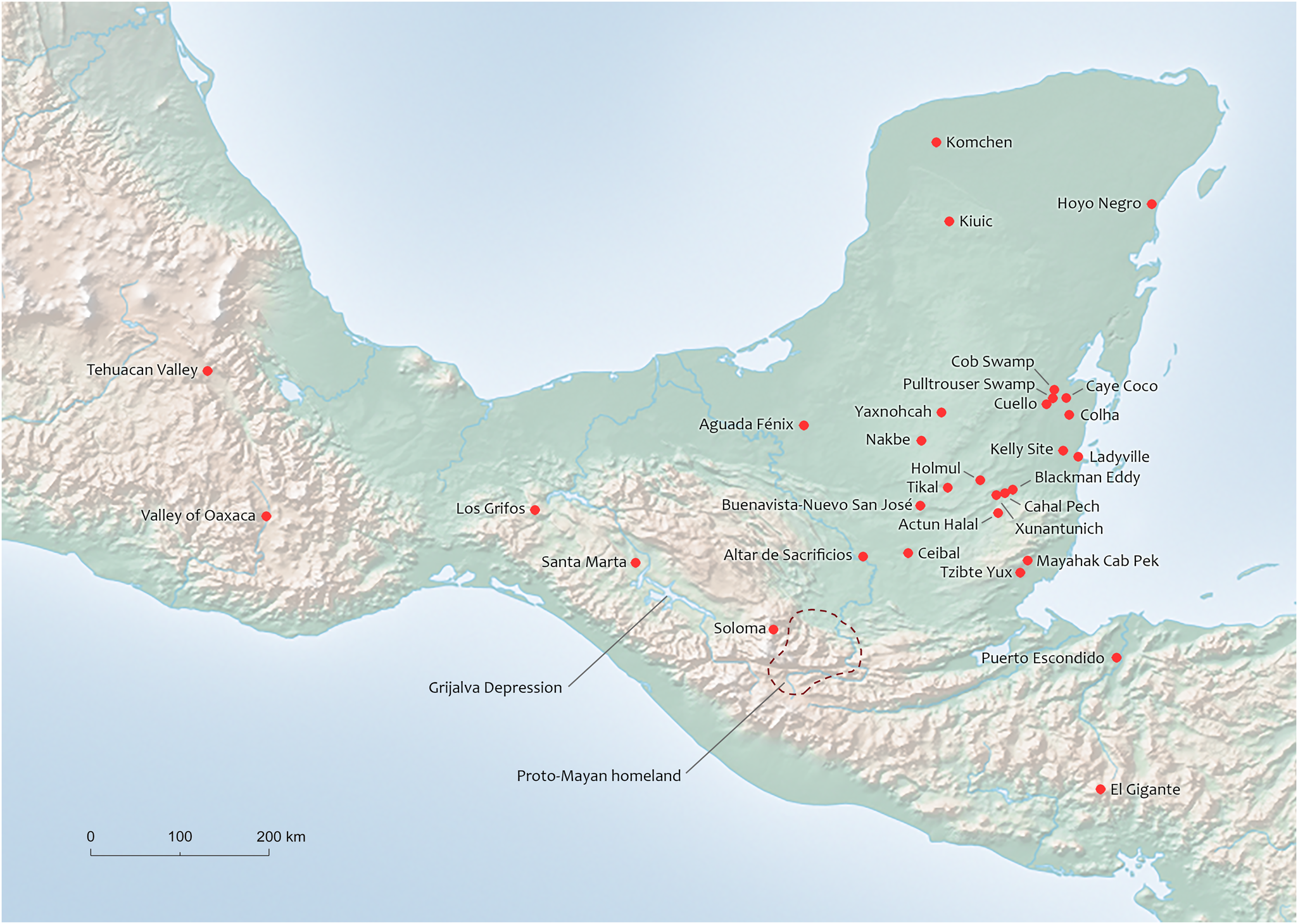

Figure 1. Map of Mesoamerica showing the sites and locations mentioned in the text. The postulated proto-Mayan homeland is also outlined. Map by Helmke.

THE PRECERAMIC AND EARLY CERAMIC CHRONOLOGY

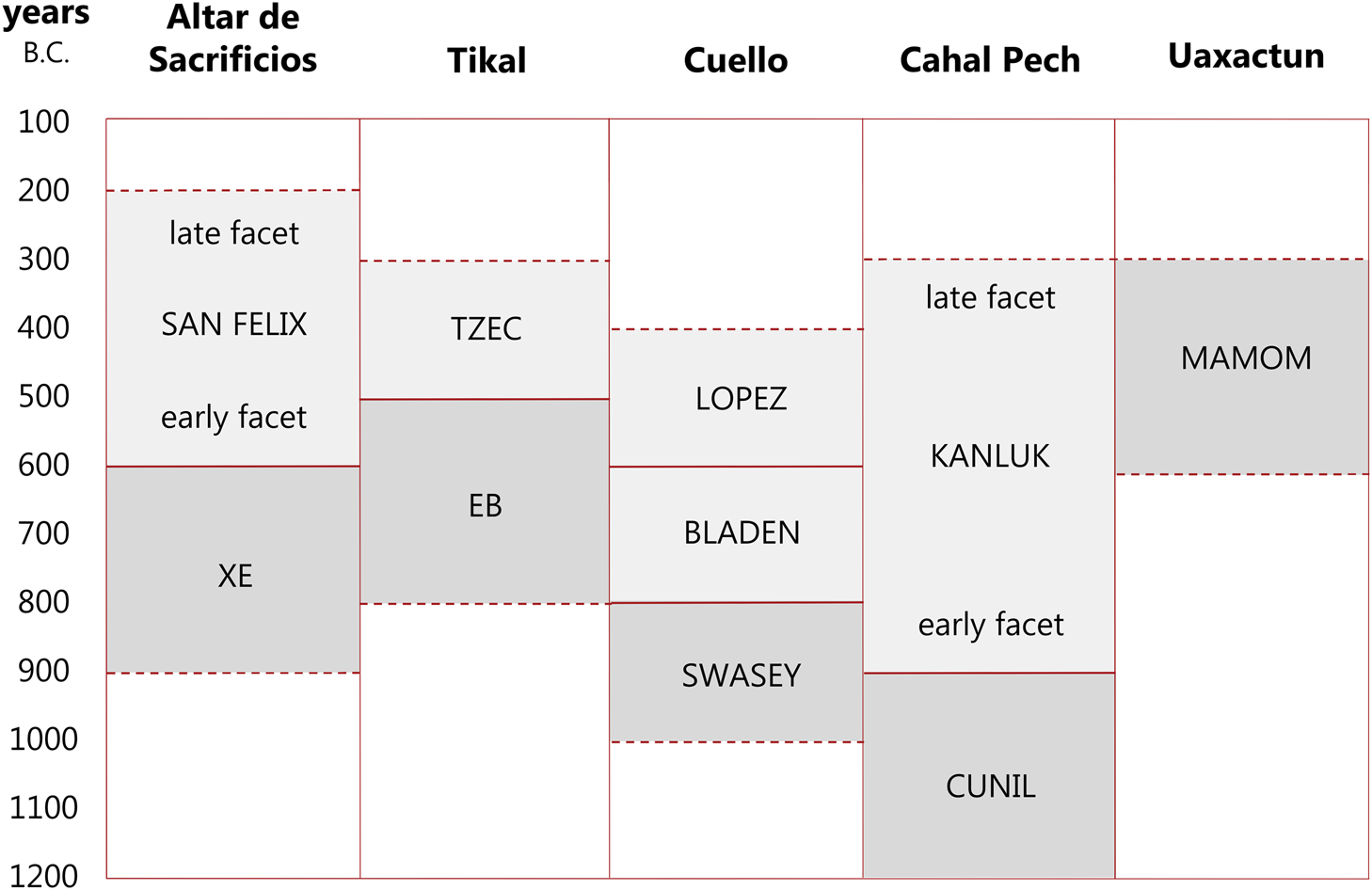

Whether crossing the Bering land bridge or traveling by boat down the Pacific coast of the Americas, the first migrants to enter the “New World” ultimately arrived in Mexico and Central America at least by the Late Pleistocene (ca. 11,000 b.c.) (Acosta Ochoa Reference Acosta Ochoa2010; Acosta Ochoa et al. Reference Acosta Ochoa, Pérez-Martínez, Ulloa-Montemayor, Suárez and Ardelean2019; Chatters et al. Reference Chatters, Kennett, Asmerom, Kemp, Polyak, Blank, Beddows, Reinhardt, Arroyo-Cabrales, Bolnick, Malhi, Culleton, Erreguerena, Rissolo, Morell-Hart and Stafford2014; Cooke Reference Cooke1998; González et al. Reference González, Huddart, Israde-Alcántara, Domínguez-Vázquez, Bischoff and Felstead2015; González González et al. Reference González González, Sandoval, Núñez, Olguín, Ramírez, del Río Lara, Erreguerena, Morlet, Stinnesbeck, Maza, Sanvicente, Leshikar-Denton and Erreguerena2008a, Reference González González, Sandoval, Mata, Sanvicente, Stinnesbeck, Avilés, de los Ríos-Paredes and Aceves2008b, Reference González González, Terrazas, Stinnesbeck, Benavente, Avilés, Rojas, Padilla, Velásquez, Acevez, Frey, Graf, Ketron and Waters2013; Stinnesbeck et al. Reference Stinnesbeck, Becker, Hering, Frey, González, Fohlmeister, Stinnesbeck, Frank, Mata, Benavente, Olguín, Núñez, Zell and Deininger2017; Waters et al. Reference Waters, Stafford and Carlson2020; Zeitlin and Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin, Zeitlin, Adams and MacLeod2000; see Flannery Reference Flannery2009; Flannery and Hole Reference Flannery and Hole2019). Until recently, there were few radiocarbon dates for the preceramic in the central Maya lowlands overall (Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Kelly Reference Kelly1993; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin1984). Preceramic sites and isolated surface finds were mainly identified by diagnostic stone tool types, heavily patinated debitage, and the lack of pottery (e.g., MacNeish and Nelken-Terner Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983a, Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983b; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2004, Reference Rosenswig2021; Rosenswig and Masson Reference Rosenswig and Masson2001; Stemp and Harrison-Buck Reference Stemp and Harrison-Buck2019). Historically, the preceramic chronology that most archaeologists referenced for the central Maya lowlands was based on stone tool types and some radiocarbon dates from northern Belize (see Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Jacob Reference Jacob1995; Jones Reference Jones1994; Kelly Reference Kelly1993; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996). This chronology divides early occupation into the Paleoindian period (ca. 11,500–8000 b.c.) and the Archaic period (ca. 8000–900 b.c.). The Archaic is further subdivided into the Early Archaic (8000–3400 b.c.) and the Late Archaic (3400–900 b.c.), the latter of which consists of an Early Preceramic phase (3400–1900 b.c.) and a Late Preceramic phase (1500–900 b.c.) in northern Belize (Figure 2; Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006:222, Figure 8; Zeitlin and Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin, Zeitlin, Adams and MacLeod2000).

Figure 2. Preceramic and early ceramic Belize Archaic Archaeological Reconnaissance (BAAR) chronologies and technologies in Belize and the central Maya lowlands. Chart by Helmke.

The earliest ceramics, such as Swasey/Bolay phase pottery from northern Belize (Andrews and Hammond Reference Andrews and Hammond1990; Kosakowsky et al. Reference Kosakowsky, Sagebiel and Pring2018; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021) and Cunil phase pottery from central Belize (Awe Reference Awe1992; Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Cheetham Reference Cheetham and Powis2005; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Awe, Brown, Brown and Bey2018), have been dated to the Early to Middle Preclassic (ca. 1200/1000–1000/800 b.c.). Therefore, the 900 b.c. date for the end of a “preceramic” Late Archaic may be too recent for some sites. Moreover, dates for the first pottery in other parts of Mesoamerica, such as the Tronadora complex (ca. 2000 b.c.) from northwest Costa Rica (Hoopes Reference Hoopes1994), the Barra phase (ca. 1900 cal b.c.) from the Soconusco region of Chiapas (Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2006), the Espiridión phase (ca. 2000 b.c.) in Oaxaca (Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2015), and the Baharona phase (ca. 1600 b.c.) along the Caribbean coast of Honduras (Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001), are presently earlier than those in the central Maya lowlands and are also chronologically within the Belizean Archaic.

THE PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC PERIODS

The First People: Who Were They?

There are few skeletons from preceramic contexts from the central Maya lowlands (Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Hoggarth and Marshall2021a). As such, we do not have a good sense of population composition or changes in demography over time as preceramic hunter-gatherers gave way to early settled Maya populations (Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, López Pérez and Ebert2021b). Despite some controversies over dating these human remains, there is incontrovertible evidence for people in the region as early as around 13,000 to 12,000 years ago, based on dated human remains from caves in the Yucatan Peninsula (Arroyo et al. Reference Arroyo, Luna, Chatters, Rissolo, Chávez, Nava and Barba2015; Chatters et al. Reference Chatters, Kennett, Asmerom, Kemp, Polyak, Blank, Beddows, Reinhardt, Arroyo-Cabrales, Bolnick, Malhi, Culleton, Erreguerena, Rissolo, Morell-Hart and Stafford2014; González González et al. Reference González González, Sandoval, Mata, Sanvicente, Stinnesbeck, Avilés, de los Ríos-Paredes and Aceves2008b, Reference González González, Terrazas, Stinnesbeck, Benavente, Avilés, Rojas, Padilla, Velásquez, Acevez, Frey, Graf, Ketron and Waters2013; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Méndez, de Saint Pierre, Aspillaga and Politis2015; Posth et al. Reference Posth, Nakatsuka, Lazaridis, Skoglund, Mallick, Lamnidis, Rohland, Nägele, Adamski, Bertolini, Broomandkhoshbacht, Cooper, Culleton, Ferraz, Ferry, Furtwängler, Haak, Harkins, Harper, Hünemeier, Lawson, Llamas, Michel, Nelson, Oppenheimer, Patterson, Schiffels, Sedig, Stewardson, Talamo, Wang, Hublin, Hubbe, Harvati, Delaunay, Beier, Francken, Kaulicke, Reyes-Centeno, Rademaker, Trask, Robinson, Gutierrez, Prufer, Salazar-García, Chim, Gomes, Alves, Liryo, Inglez, Oliveira, Bernardo, Barioni, Wesolowski, Scheifler, Rivera, Plens, Messineo, Figuti, Corach, Scabuzzo, Eggers, DeBlasis, Reindel, Méndez, Politis, Tomasto-Cagigao, Kennett, Strauss, Fehren-Schmitz, Krause and Reich2018; Stinnesbeck et al. Reference Stinnesbeck, Becker, Hering, Frey, González, Fohlmeister, Stinnesbeck, Frank, Mata, Benavente, Olguín, Núñez, Zell and Deininger2017; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Hoggarth and Marshall2021a). These remains point to genetic connections to ancient North and South Americans, and link indigenous peoples to ancient Eurasians.

These genetic data support reconstructions of a complex process of multiple migrations into the lowlands from North and South America (Chatters et al. Reference Chatters, Kennett, Asmerom, Kemp, Polyak, Blank, Beddows, Reinhardt, Arroyo-Cabrales, Bolnick, Malhi, Culleton, Erreguerena, Rissolo, Morell-Hart and Stafford2014; Posth et al. Reference Posth, Nakatsuka, Lazaridis, Skoglund, Mallick, Lamnidis, Rohland, Nägele, Adamski, Bertolini, Broomandkhoshbacht, Cooper, Culleton, Ferraz, Ferry, Furtwängler, Haak, Harkins, Harper, Hünemeier, Lawson, Llamas, Michel, Nelson, Oppenheimer, Patterson, Schiffels, Sedig, Stewardson, Talamo, Wang, Hublin, Hubbe, Harvati, Delaunay, Beier, Francken, Kaulicke, Reyes-Centeno, Rademaker, Trask, Robinson, Gutierrez, Prufer, Salazar-García, Chim, Gomes, Alves, Liryo, Inglez, Oliveira, Bernardo, Barioni, Wesolowski, Scheifler, Rivera, Plens, Messineo, Figuti, Corach, Scabuzzo, Eggers, DeBlasis, Reindel, Méndez, Politis, Tomasto-Cagigao, Kennett, Strauss, Fehren-Schmitz, Krause and Reich2018; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019; Roca-Rada et al. Reference Roca-Rada, Souilmi, Teixeira and Llamas2020; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Hoggarth and Marshall2021a; also see Ochoa-Lugo et al. Reference Ochoa-Lugo, de Lourdes Muñoz, Pérez-Ramírez, Beaty, López-Armenta, Cervini-Silva, Moreno-Galeana, Meza, Ramos, Crawford and Romano-Pacheco2016 for connections between prehispanic Maya and East Asian populations). However, some of the remains indicate no biological connection between the earliest humans in Mesoamerica and the ancestors of the people who would become the Maya (Chatters et al. Reference Chatters, Kennett, Asmerom, Kemp, Polyak, Blank, Beddows, Reinhardt, Arroyo-Cabrales, Bolnick, Malhi, Culleton, Erreguerena, Rissolo, Morell-Hart and Stafford2014; Posth et al. Reference Posth, Nakatsuka, Lazaridis, Skoglund, Mallick, Lamnidis, Rohland, Nägele, Adamski, Bertolini, Broomandkhoshbacht, Cooper, Culleton, Ferraz, Ferry, Furtwängler, Haak, Harkins, Harper, Hünemeier, Lawson, Llamas, Michel, Nelson, Oppenheimer, Patterson, Schiffels, Sedig, Stewardson, Talamo, Wang, Hublin, Hubbe, Harvati, Delaunay, Beier, Francken, Kaulicke, Reyes-Centeno, Rademaker, Trask, Robinson, Gutierrez, Prufer, Salazar-García, Chim, Gomes, Alves, Liryo, Inglez, Oliveira, Bernardo, Barioni, Wesolowski, Scheifler, Rivera, Plens, Messineo, Figuti, Corach, Scabuzzo, Eggers, DeBlasis, Reindel, Méndez, Politis, Tomasto-Cagigao, Kennett, Strauss, Fehren-Schmitz, Krause and Reich2018). Moreover, current genetic evidence provided by skeletons from southern Belizean rockshelters paints a complex picture of incipient development. The aDNA data from these skeletons indicate that preceramic people buried in southern Belize possess some ancestry associated with modern people from lower Central America and northern South America (Posth et al. Reference Posth, Nakatsuka, Lazaridis, Skoglund, Mallick, Lamnidis, Rohland, Nägele, Adamski, Bertolini, Broomandkhoshbacht, Cooper, Culleton, Ferraz, Ferry, Furtwängler, Haak, Harkins, Harper, Hünemeier, Lawson, Llamas, Michel, Nelson, Oppenheimer, Patterson, Schiffels, Sedig, Stewardson, Talamo, Wang, Hublin, Hubbe, Harvati, Delaunay, Beier, Francken, Kaulicke, Reyes-Centeno, Rademaker, Trask, Robinson, Gutierrez, Prufer, Salazar-García, Chim, Gomes, Alves, Liryo, Inglez, Oliveira, Bernardo, Barioni, Wesolowski, Scheifler, Rivera, Plens, Messineo, Figuti, Corach, Scabuzzo, Eggers, DeBlasis, Reindel, Méndez, Politis, Tomasto-Cagigao, Kennett, Strauss, Fehren-Schmitz, Krause and Reich2018; Roca-Rada et al. Reference Roca-Rada, Souilmi, Teixeira and Llamas2020). Migrants from these regions (who were part of the initial Clovis population [Anzick] who moved into Central and South America) appear to have traveled north again and intermixed with populations already in Belize in the Early Archaic.

Based on human (and plant) genetic evidence, populations from regions in lower Central America and northern South America contributed to the first people in the central Maya lowlands (Kistler et al. Reference Kistler, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Domic, Bergström, George, Harper, Allaby, Hirth and Kennett2020; Posth et al. Reference Posth, Nakatsuka, Lazaridis, Skoglund, Mallick, Lamnidis, Rohland, Nägele, Adamski, Bertolini, Broomandkhoshbacht, Cooper, Culleton, Ferraz, Ferry, Furtwängler, Haak, Harkins, Harper, Hünemeier, Lawson, Llamas, Michel, Nelson, Oppenheimer, Patterson, Schiffels, Sedig, Stewardson, Talamo, Wang, Hublin, Hubbe, Harvati, Delaunay, Beier, Francken, Kaulicke, Reyes-Centeno, Rademaker, Trask, Robinson, Gutierrez, Prufer, Salazar-García, Chim, Gomes, Alves, Liryo, Inglez, Oliveira, Bernardo, Barioni, Wesolowski, Scheifler, Rivera, Plens, Messineo, Figuti, Corach, Scabuzzo, Eggers, DeBlasis, Reindel, Méndez, Politis, Tomasto-Cagigao, Kennett, Strauss, Fehren-Schmitz, Krause and Reich2018; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019, Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021). This constitutes an important heritage, as today's Maya demonstrate a significant genetic connection to these early migrants from lower Central America and South America (see Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Hoggarth and Marshall2021a).

Lithic Technology

The Paleoindian period in Mesoamerica was mainly defined by the presence of stone tools, specifically fluted lanceolate (or Clovis-style) and fishtail (or Fell's Cave-style) bifaces, that are similar to dated examples from North and South America (Acosta Ochoa et al. Reference Acosta Ochoa, Pérez-Martínez, Ulloa-Montemayor, Suárez and Ardelean2019; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Holliday, Bright, Graf, Ketron and Waters2013; Morrow and Morrow Reference Morrow and Morrow1999; Nami Reference Nami2021; Waters et al. Reference Waters, Amorosi and Stafford2015, Reference Waters, Stafford and Carlson2020). There are a few fluted points from highland Chiapas and Guatemala that have been dated to the Paleoindian period (see Acosta Ochoa Reference Acosta Ochoa, Nichols and Pool2012:133; Acosta Ochoa et al. Reference Acosta Ochoa, Pérez-Martínez, Ulloa-Montemayor, Suárez and Ardelean2019:99; Santamaría and García-Bárcena Reference Santamaría and García-Bárcena1989), but most are undated or of questionable date (Brown Reference Brown1980; Bullen and Plowden Reference Bullen and Plowden1963; Coe Reference Coe1960; Gruhn et al. Reference Gruhn, Bryan and Nance1977; Hayden Reference Hayden1980; Méndez Salinas and Lohse Reference Méndez Salinas, Lohse, Arroyo, Palma and Aragón2010). Similarly, there are no radiocarbon dates for the three fluted lanceolate points and four fluted fishtail points from Belize (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Kelly and Ligabue1981; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; MacNeish and Nelken-Terner Reference MacNeish and Nelken-Terner1983a; MacNeish et al. Reference MacNeish, Wilkerson and Nelken-Terner1980; Pearson and Bostrom Reference Pearson and Bostrom1998; Valdez and Aylesworth Reference Valdez and Aylesworth2005; Weintraub Reference Weintraub1994; see Supplementary Material 1). The presence of both fluted lanceolate and fishtail points in the central Maya lowlands, as well as the “fishtail”-like traits on some lanceolate points from Belize (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Kelly and Ligabue1981; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006:216; Pearson Reference Pearson2017:216–217; Valdez and Aylesworth Reference Valdez and Aylesworth2005), suggests migration into the region from both the north and the south.

Recent excavations in the Mayahak Cab Pek and Tzibte Yux rockshelters (Prufer Reference Prufer2018; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019, Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Prufer and Helmke2016) in southern Belize have provided some radiocarbon dates associated with an alternately beveled biface point fragment (10,450–10,085 cal b.c.) and three, possibly four, stemmed points called Lowe (8275–6650 cal b.c.; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021). These discoveries indicate a much earlier age for the first appearance of edge beveling and stemmed and barbed bifaces than the Late Archaic date (2500–1900 b.c.) previously proposed for Lowe points; that age is based on two radiocarbon dates possibly associated with three of these points recovered from Ladyville 1 and Pulltrouser Swamp in northern Belize (Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996).

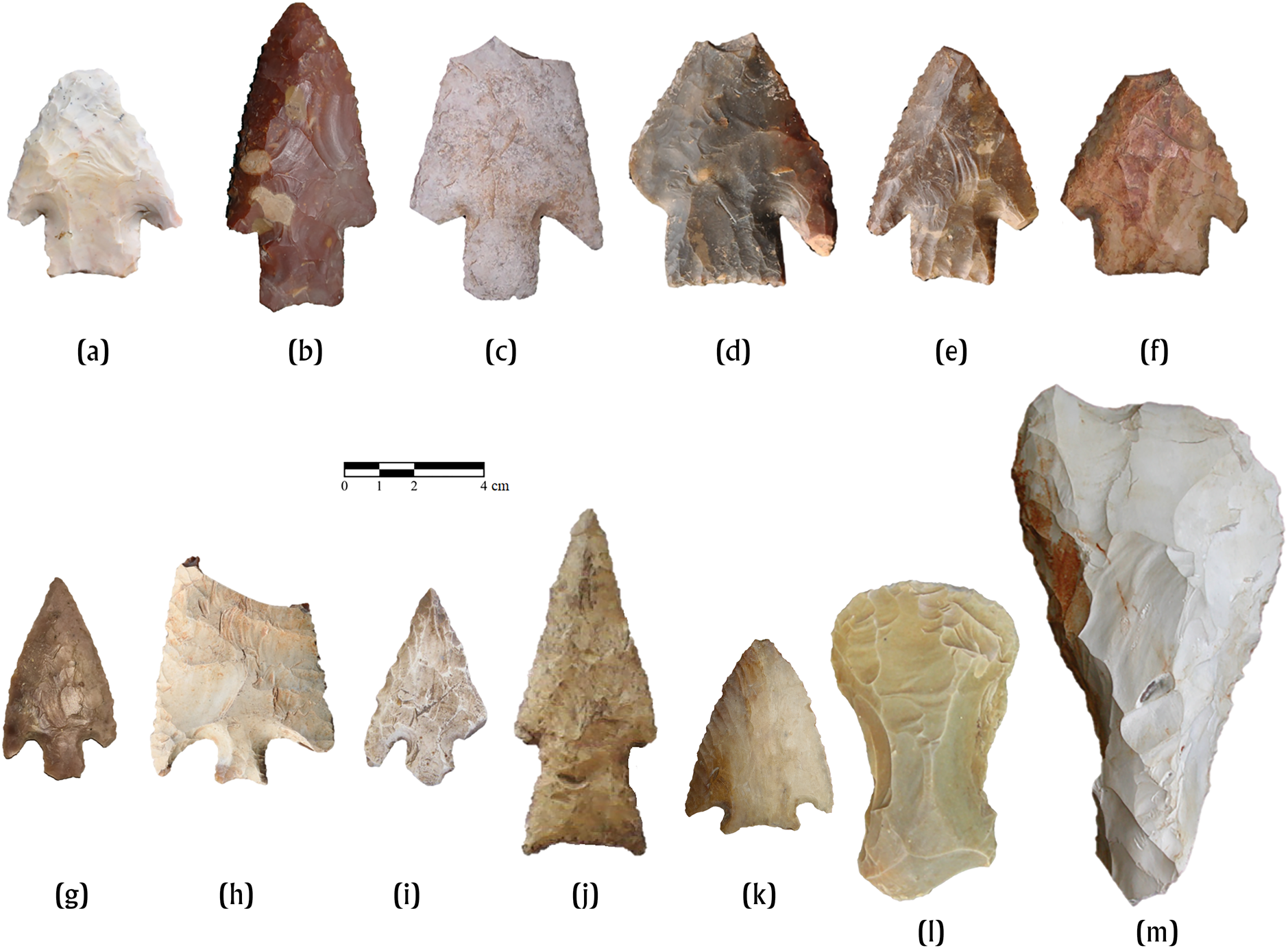

The new dates from southern Belize suggest that stemmed, barbed, and alternately beveled Lowe points (Figures 3a–3f) first appear in Belize in the Early Holocene and should be considered Late Paleoindian to Early Archaic in age; however, their relationships to fluted lanceolate and fishtail points and other stemmed points in Belize are not clear. It is possible that other stemmed points from Belize, specifically Sawmill, provisional Allspice, and provisional Ya'axche', are also earlier, but they remain to be dated (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Shafer and Kelly1980; Kelly Reference Kelly1993; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Stemp and Awe Reference Stemp and Awe2013; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Prufer and Helmke2016; see Supplementary Material 1; Figures 3g–3k). Relatedly, the whole stemmed points and point fragments with basally thinned or fluted stems from the Esperanza phase (ca. 9200–7600 b.c.) in El Gigante rockshelter, Honduras, provide additional support for an Early Archaic date for stemmed points in southern Mesoamerica (Iceland and Hirth Reference Iceland, Hirth, Lohse, Borejsza and Joyce2021; Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Webster, Culleton, Harper, Kistler, Scheffler and Hirth2017; Lohse Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020:16; Scheffler Reference Scheffler2008; Scheffler et al. Reference Scheffler, Hirth and Hasemann2012). For most of the Early Archaic, there are few sites with examples of lithic technology, although expedient tools were being used (Acosta Ochoa Reference Acosta Ochoa2010; Acosta Ochoa et al. Reference Acosta Ochoa, Pérez-Martínez, Ulloa-Montemayor, Suárez and Ardelean2019; Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014; Scheffler Reference Scheffler2008). By the middle of the Early Archaic (ca. 6000 b.c.), bifacial point technology seems to have disappeared throughout much of the central Maya lowlands (Acosta Ochoa et al. Reference Acosta Ochoa, Pérez-Martínez, Ulloa-Montemayor, Suárez and Ardelean2019; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Scheffler et al. Reference Scheffler, Hirth and Hasemann2012:604–605).

Figure 3. Diagnostic Archaic period lithics from Belize, including (a–f) Lowe points; (g–i) Sawmill points; (j) a provisional Allspice point; (k) a provisional Ya'axche' point; and (l–m) constricted adzes. Photographs by Awe, Stemp, L. McLoughlin, Satoru Murata, and Gabriel Wrobel.

Around the beginning of the Late Archaic (ca. 3400 b.c.), other diagnostic tools, including blades, macroblades, and pointed unifaces, appear in northern Belize (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Iceland, Hudler and Shafer1996; Iceland Reference Iceland1997, Reference Iceland and Powis2005; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Zeitlin and Zeitlin Reference Zeitlin, Zeitlin, Adams and MacLeod2000:87). Macroblades, as well as small bifacial celts, continued to the end of the Late Archaic in northern Belize; forms of these tools are also found in Middle Preclassic contexts at Colha (Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Potter Reference Potter, Thomas R. and Shafer1991; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014; Stemp and Harrison-Buck Reference Stemp and Harrison-Buck2019). However, these tool types appear to be absent in central Belize, where there was a reliance on expedient lithic technology near the end of the Late Archaic into the Preclassic periods (M. K. Brown et al. Reference Brown, Jennifer Cochran and Mixter2011; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2015, Reference Horowitz2017; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Kathryn Brown and Garber2018a).

A diagnostic tool type from the latter half of the Late Archaic is the constricted adze used on wood and in soil (Gibson Reference Gibson, Hester and Shafer1991; Hudler and Lohse Reference Hudler and Lohse1994; Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Stemp and Harrison-Buck Reference Stemp and Harrison-Buck2019; see Supplement Material 1; Figures 3l and 3m). These tools have been assigned a date range of approximately 2200–900 b.c., based on radiocarbon dates from Colha and Pulltrouser Swamp in northern Belize (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Iceland, Hudler and Shafer1996; Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996) and Actun Halal in central Belize (Lohse Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020; see also Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007:Table 1; Lohse Reference Lohse2010:340, Figure 13 for RC date Beta-221898). Constricted unifaces and one constricted biface have been found in northern and central Belize (Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Murata Reference Murata2011; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014; Stemp and Awe Reference Stemp and Awe2013; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Kathryn Brown and Garber2018a), but have not been reported from elsewhere in the central Maya lowlands. The use of constricted adzes indicates that early inhabitants of Belize were starting to clear the forest to create open spaces for farming as they transitioned to more settled lifestyles.

Subsistence: Hunting, Gathering, and Early Cultigens

Current evidence indicates that the first people who arrived in Central America in the Late Pleistocene adapted to increasingly warmer and wetter environments. They began to exploit new biota that accompanied the transition to the Holocene and the development of dense tropical broadleaf forests in later millennia (Hodell et al. Reference Hodell, Anselmetti, Ariztegui, Brenner, Curtis, Gilli, Grzesik, Guilderson, Müller, Bush, Correa-Metrio, Escobar and Kutterolf2008; Grauel et al. Reference Grauel, Hodell and Bernasconi2016; Piperno and Pearsall Reference Piperno and Pearsall1998; Piperno and Smith Reference Piperno, Smith, Nichols and Pool2012; Prufer and Kennett Reference Prufer, Kennett, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020; Winter et al. Reference Winter, Zanchettin, Lachniet, Vieten, Pausata, Ljungqvist, Cheng, Lawrence Edwards, Miller, Rubinetti, Rubino and Taricco2020). Preserved plant remains from preceramic sites in Belize and Guatemala are quite limited. Currently, there are no plant remains dated from the Paleoindian to the middle of the Early Archaic period (ca. 11,500–4500 b.c.) in these regions. However, starch grains, pollen, and macrofossil evidence from the Santa Marta rockshelter in Chiapas, Mexico indicate the likely consumption of wild plant resources and possibly semi-domesticated species, such as green tomato, nance, figs, and possibly cacao, as well as teosinte (Acosta Ochoa Reference Acosta Ochoa2010). The remains of maguey/agave, hog plum, avocado, mamey (Pouteria sapota), mesquite beans, and acorns have also been recovered from El Gigante rockshelter in Honduras in the Early Archaic (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Webster, Culleton, Harper, Kistler, Scheffler and Hirth2017; Scheffler Reference Scheffler2008; Scheffler et al. Reference Scheffler, Hirth and Hasemann2012).

Although relatively little is known about the fauna from preceramic sites in the central Maya lowlands, skeletal remains provide clues to subsistence as early as the Late Pleistocene. The remains of horse, peccary, and spectacled bear in Actun Halal suggest the consumption of these Terminal Pleistocene Ice Age mammals; however, associations with nondiagnostic chipped stone tools are tenuous (Griffith and Morehart Reference Griffith, Morehart and Awe2001; Griffith et al. Reference Griffith, Ishihara, Jack and Awe2002; Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007; Lohse and Collins Reference Lohse and Collins2004; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006). Excavations in the Santa Marta rockshelter revealed the bones of deer, peccary, rabbits, snakes, iguana, and tortoises, as well as the shells of the freshwater snail known as jute (Pachychilus sp.) (Acosta Ochoa Reference Acosta Ochoa2010). Also found in Actun Halal were the bones of the common agouti, in association with a small quantity of chert debitage from deposits dating to near the end of the Early Archaic (Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007, Reference Lohse2010:323, Table 1, Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020), and deer, birds, turtles, crab, and snails have been reported from El Gigante in Honduras (Scheffler Reference Scheffler2008; Scheffler et al. Reference Scheffler, Hirth and Hasemann2012). Moreover, the stratified rockshelters of southern Belize indicate that jute was an important dietary resource beginning in the Early Archaic (Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019).

The use of plant domesticates, based on the recovery of starches and pollen from Archaic sites in northern and central Belize, began around 4500 b.c., with increased use by around 3400 b.c. (Blake Reference Blake2015; Jones Reference Jones1994; Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007, Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig2021; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014). Collectively, the floral remains from sites in northern and central Belize suggest a diet of wild plant resources and the incorporation into the diet of cultigens such as maize and manioc, in addition to chili pepper, squash, and beans, during the transition from the end of the Early into the Late Archaic (beginning before ca. 3000 b.c.). Relatedly, the earliest maize in the El Gigante rockshelter, Honduras, dates to the Late Marcala phase (4340 and 4020 cal b.p.); however, the majority of the botanical remains consist of wild plant foods (Kistler et al. Reference Kistler, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Domic, Bergström, George, Harper, Allaby, Hirth and Kennett2020:33125).

The increasing reliance on cultigens like maize and manioc in the Late Archaic (ca. 3000–1500 b.c.) coincides with evidence for forest disturbance and deforestation, as well as landscape modification, in northern and central Belize, and the Peten and Petexbatun regions of Guatemala (Jacob Reference Jacob1995; Jones Reference Jones1994; Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007, Reference Lohse2010, Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Rosenmeier et al. Reference Rosenmeier, Hodell, Brenner, Curtis and Guilderson2002; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2021; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014; Wahl et al. Reference Wahl, Byrne, Schreiner and Hansen2006). Dietary reliance on maize may have been even more widespread in the lowlands than previously assumed. Pollen from soil cores from Basil Jones on Ambergris Caye indicates use of maize in offshore coastal locations as early as the Late Archaic (2900 b.c.; Bermingham et al. Reference Bermingham, Whitney, Loughlin and Hoggarth2021). A constricted uniface was recovered at Laguna de Cayo Francesa on Ambergris Caye as well, perhaps suggesting that more land clearance for growing food was occurring on the caye in the preceramic than previously thought (Iceland Reference Iceland1997:215; Stemp and Harrison-Buck Reference Stemp and Harrison-Buck2019:195).

Human remains provide additional clues regarding preceramic diet. For example, it has been suggested that the extensive dental caries in the teeth of Naia, a Paleoindian female adolescent from Hoyo Negro, Mexico, may have been due to consumption of fruit and possibly honey (Chatters et al. Reference Chatters, Kennett, Asmerom, Kemp, Polyak, Blank, Beddows, Reinhardt, Arroyo-Cabrales, Bolnick, Malhi, Culleton, Erreguerena, Rissolo, Morell-Hart and Stafford2014). Carbon and nitrogen isotopes in bone collagen and bone apatite from human skeletal remains from southern Belize indicate no maize in the diet prior to around 2750 cal b.c. (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Prufer, Culleton, George, Robinson, Trask, Buckley, Moes, Kate, Harper, O'Donnell, Ray, Hill, Alsgaard, Merriman, Meredith, Edgar, Awe and Gutierrez2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021). Significant amounts of vegetable protein, however, came from tropical forest plant resources. Increased consumption of maize is demonstrated between 2750 and 2050 cal b.c., with consumption on par with that observed among the Maya in the Classic period based on isotopic signatures and bone apatite data (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Prufer, Culleton, George, Robinson, Trask, Buckley, Moes, Kate, Harper, O'Donnell, Ray, Hill, Alsgaard, Merriman, Meredith, Edgar, Awe and Gutierrez2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021). Dental calculus from Archaic human remains in northern Belize provides additional evidence for plant foods, including beans, squash, sweet potato, yam, amilito, and llerén, as well as palms, grasses, and other herbaceous plants (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2018:216, Figure 5; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021).

By the Late Archaic, faunal remains from northern and central Belize indicate a wide range of prey, including common agouti, armadillo, snakes, turtles, freshwater fish, freshwater mollusks, and possibly white-tailed deer. This evidence suggests a broad-spectrum diet that included both aquatic and terrestrial animals of various types and sizes, in addition to plant foods (Iceland and Hester Reference Iceland, Hester, Peregrine and Ember2001:293; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019; Stemp and Harrison-Buck Reference Stemp and Harrison-Buck2019). Overall, Archaic period diets appear to rely on a diverse range of wild plant and animal resources, with an increasing number of cultigens, particularly maize and manioc, with the transition from the Early to Late Archaic period (Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig2021; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996).

Preceramic Living Spaces

For the most part, there is little evidence for preceramic occupation across the central Maya lowlands. Evidence from Chiapas, at Los Grifos and Santa Marta rockshelters, indicates the use of these locations beginning in the Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene (Acosta Ochoa Reference Acosta Ochoa2010, Reference Acosta Ochoa, Nichols and Pool2012; Acosta Ochoa et al. Reference Acosta Ochoa, Pérez-Martínez, Ulloa-Montemayor, Suárez and Ardelean2019:99; García-Bárcena and Santamaría Reference García-Bárcena and Santamaría1982; Santamaría Reference Santamaría, García-Bárcena and Sánchez1981). In southern Belize, three rockshelters south of the Maya Mountains indicate human occupation in the Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene (Prufer and Kennett Reference Prufer, Kennett, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019, Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021). In Honduras, occupation in the Holocene is demonstrated in El Gigante rockshelter (Scheffler Reference Scheffler2008; Scheffler et al. Reference Scheffler, Hirth and Hasemann2012). It is also possible that Actun Halal in central Belize was used in the Terminal Pleistocene, based on the presence of faunal remains and some informal chert tools (Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006). It is difficult to know whether a pattern of rockshelter use at this time suggests preferential selection of these locations by early hunter-gatherers or if, instead, preservation is simply better in rockshelters. Clearly, the karst geology of these regions is a significant factor in the discovery of early human occupations there. The use of rockshelters into the Early Archaic and, eventually, the Late Archaic continues to be demonstrated in these same locations; however, occupation is not continuous (Lohse Reference Lohse, LeCount, Jones, Beach and Hallock2007, Reference Lohse2010; Lohse et al. Reference Lohse, Awe, Griffith, Rosenswig and Valdez2006; Prufer and Kennett Reference Prufer, Kennett, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Meredith, Alsgaard, Dennehy and Kennett2017, Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019, Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Scheffler Reference Scheffler2008; Scheffler et al. Reference Scheffler, Hirth and Hasemann2012).

Although exceptionally rare, the use of open-air sites in the Archaic period can be demonstrated in northern Belize. At Caye Coco, patinated stone tools and debitage are associated with a possible living floor, including two pits and a posthole, dated to the Early Archaic to Middle Preclassic periods (Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2004, Reference Rosenswig2021; Rosenswig and Masson Reference Rosenswig and Masson2001; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014). The recovery of patinated lithics, including two Lowe points near a hearth feature dated to the Late Archaic, suggests the existence of a campsite of some sort at Ladyville 1; however, the contextual association of the hearth and the points is questionable (Kelly Reference Kelly1993:215). A pit feature has been reported from aceramic deposits in Puerto Escondido, Honduras (Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001). The rarity of preceramic sites across the central Maya lowlands, notably in Guatemala, has been addressed in a number of ways. It may be that these regions were not inhabited until the preceramic/ceramic transition or that, in dense tropical forest environments, preceramic occupation sites have just not been found yet. Alternatively, the lack of data may simply reflect the lack of projects targeting preceramic human occupation.

Preceramic tool production workshops also have been identified in northern Belize. At Colha, aceramic deposits dated to the Late Archaic contained large quantities of patinated chert, indicating in situ production of macroblades and small blades, as well as constricted unifaces, pointed unifaces, and bifacial celts (Hester et al. Reference Hester, Iceland, Hudler and Shafer1996; Iceland Reference Iceland1997, Reference Iceland and Powis2005). At the Kelly site, lithic evidence suggests specialized quarry production of constricted unifaces and small blades (Iceland Reference Iceland1997, Reference Iceland and Powis2005). Furthermore, Kelly (Reference Kelly1993:216) noted small, finely flaked end-scrapers in association with Sawmill points and knapping debris at Ladyville 32 in northern Belize. However, none of these locations has evidence for any human settlement. In central Belize, use of a quarry near the end of the Late Archaic period is suggested by the recovery of patinated lithics in an aceramic paleosol at the site of Callar Creek (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2015, Reference Horowitz2017).

Ritual Activity

There is little evidence for clearly demonstrated ritual activity among preceramic people in the central Maya lowlands. What appears, in some instances, to be the deliberate placement of individuals in caves and rockshelters may be connected to mortuary ritual of some kind based on interment or body position (González González et al. Reference González González, Sandoval, Núñez, Olguín, Ramírez, del Río Lara, Erreguerena, Morlet, Stinnesbeck, Maza, Sanvicente, Leshikar-Denton and Erreguerena2008a, Reference González González, Terrazas, Stinnesbeck, Benavente, Avilés, Rojas, Padilla, Velásquez, Acevez, Frey, Graf, Ketron and Waters2013; Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Prufer, Culleton, George, Robinson, Trask, Buckley, Moes, Kate, Harper, O'Donnell, Ray, Hill, Alsgaard, Merriman, Meredith, Edgar, Awe and Gutierrez2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Alsgaard, Robinson, Meredith, Culleton, Dennehy, Magee, Huckell, James Stemp, Awe, Capriles and Kennett2019, Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Stinnesbeck et al. Reference Stinnesbeck, Stinnesbeck, Mata, Olguín, Sanvicente, Zell, Frey, Lindauer, Sandoval, Morlet, Nuñez and González2018; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Hoggarth and Marshall2021a). This practice is difficult to confirm given the few examples recovered and the overall conditions of the remains themselves.

THE EARLY CERAMIC PERIODS

As noted by Lohse (Reference Lohse, Hutson and Ardren2020:12): “In the Maya world, the co-occurrence of ceramics, permanent construction (in the sense that the physical traces are lasting even if the duration of occupation remains unknown), and farming together commonly signals the end of the Archaic.” However, significant shifts in subsistence, settlement, and technology were occurring neither simultaneously nor consistently across the central Maya lowlands. Rosenswig (Reference Rosenswig2015:120–121) reminds us that, throughout Mesoamerica, food production, sedentism, and ceramics developed by degrees and cannot be documented simply as present or absent. However, a consequential global climatic “drying” event may have served as a significant ultimate cause for these kinds of adaptations near the end of the Archaic period (Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig2021). From the end of the preceramic into the earliest ceramic periods (ca. 1200–900 b.c.) in Belize, Guatemala, and southern Mexico, aceramic hunter-gatherers had already developed some reliance on domesticates. Subsequently, communities of pottery-making people began to appear in the archaeological record at sites dating to slightly different times; however, few Early Preclassic settlement locations are known in the central Maya lowlands. In these same areas, such as Ceibal (formerly Seibal) (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015), some of the earliest ceremonial architecture began to be built by the Middle Preclassic. In some cases, such as at Aguada Fénix, Tabasco (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Bauer, Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020), the construction of public or monumental architecture appears to precede the development of many other hallmarks of the early Maya. Sociopolitical, socioeconomic, and subsistence changes, including evidence for increasing population, higher maize yields, the appearance of non-domestic or ceremonial structures, exotic trade goods, and the beginnings of a centralized ideology and ritual, can be seen in the Middle Preclassic (1000–400 b.c.) (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Lohse Reference Lohse2010).

Early Maya Food and Farming

The disappearance of stemmed stone points, the appearance of constricted unifaces, and a reliance on expedient flake technology likely reflect changes in both mobility patterns and subsistence requirements from hunting to early horticulture (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Leonard, Jones and Maschner1998; Nelson Reference Nelson1991:76; Parry and Kelly Reference Parry, Kelly, Johnson and Morrow1987:285; Shott Reference Shott1986:19–34; Tomka Reference Tomka and Andrefsky2001:222–223; Torrence Reference Torrence and Bailey1983:13). Similar trends have been noted in North America (Koldehoff Reference Koldehoff, Johnson and Morrow1987; Odell Reference Odell1985; Sullivan and Rozen Reference Sullivan and Rozen1985) and Mesoamerica (Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Webster, Culleton, Harper, Kistler, Scheffler and Hirth2017; Marcus Reference Marcus1995:6–7; Prufer and Kennett Reference Prufer, Kennett, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Kathryn Brown and Garber2018a), as mobile hunting and gathering gave way to horticulture. By the end of the Late Archaic, a horticultural lifestyle can be observed archaeologically in Belize and the wider central Maya lowlands, with evidence for cultivation based on pollen, starch grain, phytolith, and charcoal evidence for domesticated plants, such as maize, manioc, beans, chili pepper, bottle gourds, and squash, and increasing deforestation to create milpas for planting (Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Blake Reference Blake2015; Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Iceland Reference Iceland1997; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig2021; Rosenswig et al. Reference Rosenswig, VanDerwarker, Culleton and Kennett2015; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021). During the development of the Preclassic, we see much more evidence of landscape modification in the form of canals, raised fields, and terraces (Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021). Although initial ditching for wetland cultivation in northern Belize appears to begin in the Middle Preclassic (ca. 1000 b.c.), dating these landscape modifications and agricultural features has proven to be a difficult task (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996). The dates are often skewed to the Classic, but whether the late date is the date of reuse, major reclamation, or initial use remains to be determined, case by case, canal by canal.

Early Maya villagers continued to employ diverse subsistence strategies—relying on wild plants and wild animals, as well as incorporating domesticates such as maize, manioc, and a range of fruit and orchard crops (Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021; Marcus Reference Marcus and Flannery1982; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, López Pérez and Ebert2021b). As new data suggest that semi-sedentary groups coexisted for centuries with mobile hunter-gatherers (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015), rather than a rapid agricultural revolution characterizing the end of the Archaic and the beginning of village life in the Preclassic period, it was more likely a longer and gradual shift that occurred at different times at various sites. This sequence suggests that plant remains alone cannot be used to distinguish between mobile and sedentary populations. Food-producing and attendant social practices are more complex than is often assumed and subsistence systems are generally additive (i.e., wild plant collecting is not abandoned, but augmented by the growing reliance on domesticates).

Although Late Early Preclassic villagers at Cuello and Cob Swamp clearly consumed maize, isotopic data from their skeletons suggest that maize was not yet an important component of their diet (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Tykot et al. Reference Tykot, van der Merwe, Hammond and Orna1996; van der Merwe et al. Reference van der Merwe, Tykot, Hammond, Oakberg, Ambrose and Katzenberg2000; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, López Pérez and Ebert2021b). By the Middle Preclassic, maize increasingly became a significant cultigen, but a mixed diet with differing reliance on wild resources occurred at different times throughout the lowlands. For example, isotopic data demonstrate that maize constituted only about 30 percent of the diet at Cuello; whereas, at Cahal Pech, there were differences in the amount of maize consumed by people living in the site core versus those in the periphery (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Hoggarth, Awe, Culleton and Kennett2019).

There was still a major reliance on wild plant and animal foods (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996), yet, as noted above, pollen and starch grains from northern Belize and isotopic data from skeletons from southern Belize, as well as dated maize cobs from Honduras, point to an earlier intensification of and dietary reliance on maize as a domesticated crop prior to the appearance of ceramics (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Prufer, Culleton, George, Robinson, Trask, Buckley, Moes, Kate, Harper, O'Donnell, Ray, Hill, Alsgaard, Merriman, Meredith, Edgar, Awe and Gutierrez2020; Kistler et al. Reference Kistler, Thakar, VanDerwarker, Domic, Bergström, George, Harper, Allaby, Hirth and Kennett2020; Prufer et al. Reference Prufer, Robinson and Kennett2021; Rosenswig Reference Rosenswig, Pearsall, Masson, Culleton and Kennett2014, Reference Rosenswig2015, Reference Rosenswig2021). Nevertheless, ceramics suggest the use of maize in association with a special preparation technique (Blake Reference Blake2015). As such, evidence for consumption of maize may be demonstrated by the appearance of ceramic colanders in the Early to Middle Preclassic period at sites such as Blackman Eddy and Cahal Pech (Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Brown Reference Brown2003:Figure 5.3; Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021; Cheetham Reference Cheetham, Staller and Carrasco2010; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004:36, Figure 3.5b). These colanders were used to drain and rinse softened corn kernels in the process of making nixtamal (boiled, lime-treated maize).

By the Middle Preclassic, the presence of domesticates (maize, beans, squash), wild fruits (nance, hogplum, guava, soursop), tubers (manioc, sweet potato), and cacao (Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021) is documented in many locations; however, maize may still not have been a dietary staple in all parts of the Maya lowlands (Cagnato Reference Cagnato2021; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Hohmann, Powis and Garber2004; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Stanchly, White, Healy, Awe and Longstaffe1999; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, López Pérez and Ebert2021b). Reliance on a wide variety of both local land and aquatic animals, such as deer, dog, peccary, armadillo, agouti, rabbit, turtles, birds, reptiles, fish, and freshwater mollusks, is also widely demonstrated in the Early Middle Preclassic at sites in northern and central Belize (Awe Reference Awe1992; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Masson Reference Masson and Emery2004; Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope, Jones, Jacob, Piperno, deFrance, Lentz, Gifford, Danforth and Kathryn Josserand1996; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Stanchly, White, Healy, Awe and Longstaffe1999; Shaw Reference Shaw and White1999; Stanchly Reference Stanchly, Healy and Awe1995, Reference Stanchly, Healy and Awe1999; Stanchly and Burke Reference Stanchly and Burke2018; Wing and Scudder Reference Wing, Scudder and Hammond1991), although specific species consumed varied from location to location. It is possible that certain species, such as deer and dog, may have served ritual purposes given associations with the Maya elite in later times (Pohl Reference Pohl, Leventhal and Kolata1983; Stanchly and Awe Reference Stanchly and Awe2015).

Early Pottery

Although pottery developed earlier in the Soconusco and Oaxaca regions of Mexico, as well as along the Caribbean coast of Honduras (see above), there were differences between sites and regions in terms of when pottery appeared and people committed to a fully sedentary life. While the dating of the first appearance of pottery is still controversial (Ball and Taschek Reference Ball and Taschek2003; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013, Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Lohse Reference Lohse2010), most scholars agree that pre-Mamom pottery begins to appear intermittently across the central Maya lowlands by at least 1000 b.c., if not earlier, with deposits recovered from sites in Belize, the Peten of Guatemala, and neighboring areas (Figure 4; Supplementary Material 2). By this time, several ceramic complexes had appeared, including Xe and Real in the Pasión River Valley (Adams Reference Adams1971; Willey Reference Willey and Bullard1970; Willey et al. Reference Willey, Culbert and Adams1967) and the Middle Usumacinta (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Bauer, Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020), Eb in the north and central Peten (Culbert Reference Culbert1993; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019), Swasey and Bolay in northern Belize (Kosakowsky Reference Kosakowsky1987; Kosakowsky and Pring Reference Kosakowsky and Pring1998; Kosakowsky et al. Reference Kosakowsky, Sagebiel and Pring2018; Valdez Reference Valdez1987, Reference Valdez, Hester, Shafer and Eaton1994; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021), Cunil (Awe Reference Awe1992; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Awe and Brown2009), Kanocha (Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004), and early facet Jenney Creek in the Belize River Valley (Gifford Reference Gifford1976; Sharer and Kirkpatrick Reference Sharer, Kirkpatrick and Gifford1976), as well as Ek and Ch'oh Ek in the Yucatan (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Bey, Gunn, Kathryn Brown and Bey2018), Ch'ok in Campeche (Robert M. Rosenswig, personal communication 2020; see Ek Reference Ek2015 for Champotón 1A), and Macal in the central Karstic uplands (Debra S. Walker, personal communication 2021; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Reese-Taylor and Hernandez2017). Rice (Reference Rice2019:2) has recently identified two “Pre-Mamom” complexes at Nixtun-Ch'ich' in the Peten, with the earliest, K'as, dating to 1300/1200–1100 b.c. based on two AMS radiocarbon assays.

Figure 4. Early ceramic complexes in Belize and Guatemala. Graph by Sullivan and Helmke.

The first pre-Mamom ceramic sequence to be defined and discussed in detail was the Xe complex (900–600 b.c.) at Altar de Sacrificios (Adams Reference Adams1971), followed by the Real complex at Ceibal (Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975; Willey Reference Willey and Bullard1970). The Eb complex at Tikal was first recorded during the University of Pennsylvania excavations and was originally found at only two locations: from the lowest level of cultural materials in a pit cut into bedrock located in a north–south trench that bisected the North Acropolis, and in the fill at the bottom of a chultun in the southeast quadrant of the site (Coe Reference Coe1965; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019). Ceramic data from Cuello (Andrews Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Andrews and Hammond Reference Andrews and Hammond1990; Kosakowsky Reference Kosakowsky1987; Kosakowsky and Pring Reference Kosakowsky and Pring1998; Pring Reference Pring1977) have played a significant role in our understanding of Early Middle Preclassic pottery in northern Belize. While the Swasey complex was originally defined based on flawed radiocarbon dates (Andrews Reference Andrews, Clancy and Harrison1990; Andrews and Hammond Reference Andrews and Hammond1990; Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Pring, Wilk, Donaghey, Saul, Wing, Miller and Feldman1979; Marcus Reference Marcus1983), subsequent calibrated AMS dates put Swasey “between 1000–800 bce” (Kosakowsky et al. Reference Kosakowsky, Sagebiel and Pring2018:131). Early Middle Preclassic pre-Mamom pottery was reported for the Maya site of Colha in northern Belize as well. As originally conceived by Adams, the Early Middle Preclassic pottery was given Xe type names. The initial term used to refer to this early pottery at Colha was “Xe-sey,” a term combining Xe and Swasey. As the analysis progressed, it was decided to use type names from locally established analyses. Upon establishing the Bolay complex, it was placed in the Swasey sphere based on named types. An intriguing aspect of Colha is in Archaic activity, perhaps occupation, near the site center and Cobweb Swamp. With an Archaic presence, some dates from the Early Preclassic (ca. 1127 b.c.) (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2018; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021), and an Early Middle Preclassic occupation, Colha may eventually serve to confirm some of the earliest Maya pottery production in the region.

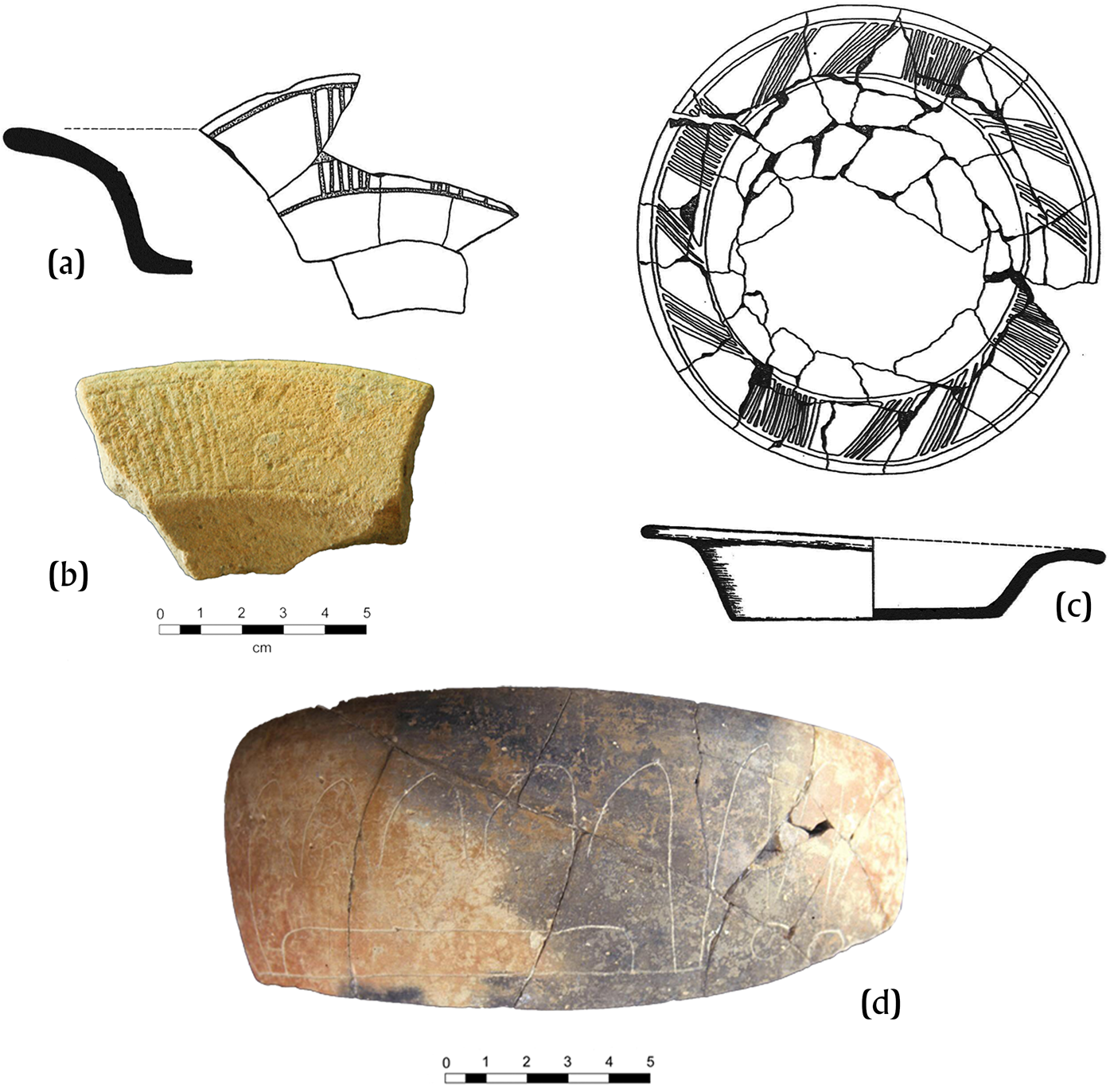

The Cunil ceramic complex was first reported by Awe at Cahal Pech, based on a sample of approximately 250 sherds, two partial vessels, and a set of radiocarbon dates that placed the Cunil phase between 1200 and 900 b.c. (Awe Reference Awe1992; see also Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Culleton, Awe and Kennett2016). The original excavations recovered Cunil pottery from the lowest levels of Structure B4 in sealed deposits, from mixed deposits in the site core, and from the peripheral Tolok and Tzinik settlement groups. Later excavations (Healy and Awe Reference Healy and Awe1995, Reference Healy and Awe1996) recovered additional ceramic evidence from Structure B4, as well as in Plaza B at Cahal Pech (Cheetham and Awe Reference Cheetham and Awe1996; Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002; Ebert Reference Ebert2017; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Horn Reference Horn2015; Peniche May Reference Peniche May2014; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Awe and Brown2009). Common Cunil forms include flat-bottom plates, and dishes with outsloping walls and wide, everted rims, as well as bowls. These everted rims are typically decorated with grooved post-slip and sometimes zoned-incised lines that depict different motifs (Figures 5a–5c). Finer post-fired incised lines on incurving bowls are also observed in the assemblage on Kitam Incised sherds (Figure 5d). Since Awe's original identification and description of Cunil pottery, other pre-Mamom complexes have been documented at lowland Maya sites, including Kanocha at Blackman Eddy (Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004), Muyal at Xunantunich (M. K. Brown et al. Reference Brown, Jennifer Cochran and Mixter2011; LeCount et al. Reference LeCount, Yaeger, Leventhal and Ashmore2002; Strelow and LeCount Reference Strelow and LeCount2001; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Awe, Brown, Brown and Bey2018), K'awil at Holmul (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and de Estrada2016), Macal at Yaxnohcah (Debra S. Walker, personal communication 2021; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Reese-Taylor and Hernandez2017), Real 1 at Ceibal (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015), Buenavista at Buenavista-Nuevo San José (Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017), Ek at Komchen, Ch'oh Ek at Kiuic (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Bey, Gunn, Kathryn Brown and Bey2018), and Ch'ok along the Río Champotón drainage (Ek Reference Ek2015; Robert M. Rosenswig, personal communication 2020), ushering in a whole new wave of research into the origin of pottery-making communities and early Maya villages (Brown and Bey Reference Brown and Bey2018; Lohse Reference Lohse2010; Sullivan and Awe Reference Sullivan, Awe and Aimers2013; Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Awe and Brown2009, Reference Sullivan, Awe, Brown, Brown and Bey2018). While these pre-Mamom ceramic complexes share some attributes, it is important to note that several of them reflect significant regional differences.

Figure 5. Cunil flat-bottom plates and dishes with outsloping walls and wide everted rims, including (a) Baki Red (Awe Reference Awe1992:229); (b) Uck Red Group from Kaxil Uinic (courtesy of Brett Houk); (c) Zotz Zoned Incised: Zotz Variety (Awe Reference Awe1992:231); and incurved-rim bowls, including (d) Kitam Incised. Drawings and photographs courtesy of Awe.

Settlements and Villages

By the beginning of the Terminal Early to Early Middle Preclassic, there is more evidence for open-air occupation locations than in the preceramic. In general, the structures appear quite simple in design and construction. This raises questions about the degree of sedentism versus mobility in the central Maya lowlands at this time. At sites in northern and central Belize, including Cuello, Colha, Blackman Eddy, Cahal Pech, Barton Ramie, K'axob, and Pacbitun, postholes in bedrock, associated with tamped floors, or low earth and marl platforms indicate the existence of long-since vanished apsidal pole-and-thatch houses (Awe Reference Awe1992; Cheetham Reference Cheetham, Healy and Awe1995; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Gerhardt and Hammond Reference Gerhardt, Hammond and Hammond1991; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Hohmann, Powis and Garber2004; Hohmann and Powis Reference Hohmann, Powis and Healy1999; Hohmann et al. Reference Hohmann, Powis, Arendt and Healy1999; McAnany Reference McAnany and McAnany2004a; Potter et al. Reference Potter, Hester, Black and Valdez1984; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Healy and Hohmann2009; Sullivan Reference Sullivan1991; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021; Willey et al. Reference Willey, Bullard, Glass and Gifford1965). Fragments of pole-impressed daub from house walls have been recovered at some sites (Awe Reference Awe1992; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004). Clay-lined hearths and low stone retaining walls point to increased investment in place at some sites. Subsequent construction atop these living floors included plastered architecture and platforms, demonstrating more social complexity, increased ceremonialism, as well as possible changes in function (Awe Reference Awe1992; Coe and Coe Reference Coe and Coe1956; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Gerhardt and Hammond Reference Gerhardt, Hammond and Hammond1991; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Hohmann, Powis and Garber2004; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Healy and Hohmann2009; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021).

In northeastern Guatemala, Nakbe provides evidence for early structures in the form of packed earthen floors and postholes in bedrock, which are similar to examples from northern Belize (Hansen Reference Hansen and Houston1998, Reference Hansen and Powis2005). Postholes and plaster floors have been reported at Middle Preclassic Altar de Sacrificios as well (Willey Reference Willey1973). However, the sites of Buenavista-Nuevo San José, Caobal, Ceibal, El Mirador, El Palmar, and Nixtun Ch'ich' possess evidence for sedentary occupation that is more ephemeral. At these sites, early surface preparation atop cleared bedrock consisted of layers of clay/clayey soil and crushed limestone that was eventually covered by plaster surfaces (Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Doyle Reference Doyle, Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017; Hansen Reference Hansen, Traxler and Sharer2016; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013, Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015; Rice Reference Rice2009, Reference Rice2019; Rice et al. Reference Rice, Pugh and Nieto2019). Although lacking the evidence for actual houses, radiocarbon dates or ceramics from the clay deposits at these sites in Guatemala suggest occupation around the beginning of the early ceramic period. Moreover, Early Middle Preclassic (ca. 1000–700 b.c.) ceramics from other Guatemalan sites, such as Cival, Holmul, Tikal, Uaxactun, and Yaxha (Callaghan and Neivens de Estrada Reference Callaghan and de Estrada2016; Culbert Reference Culbert1993; Culbert and Kosakowsky Reference Culbert and Kosakowsky2019; Rice Reference Rice1979; Smith Reference Smith1955) indicate an early Maya presence, despite the absence of excavated dwellings.

Notably, in Guatemala, Ceibal demonstrates the use of formal architecture for the construction of a ceremonial complex (an early E-group) in the absence of a recognizable residential settlement at the site (cf., Platform Sulul). Inomata et al. (Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015) note that this pattern might suggest that a mobile lifestyle may have persisted longer than previously thought and that the construction of communal architectural structures may be associated with populations with different levels of mobility. Alternatively, it may mean that less complex and ephemeral residential architecture, such as that reported at Puerto Escondido, Honduras, has yet to be discovered at the site. At Nixtun Ch'ich', the construction of early formal architecture, such as platforms and, later, an E-group, in the Early Middle Preclassic is documented above the clay “residential” surfaces (Rice Reference Rice2019; Rice et al. Reference Rice, Pugh and Nieto2019). Early formal architecture is further demonstrated at the site of Aguada Fénix in southern Mexico, where Inomata et al. (Reference Inomata, Triadan, López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Bauer, Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020) discovered a large artificial plateau/platform with associated causeways, dated to approximately 1000–800 b.c. The monumental architecture at Aguada Fénix suggests communal construction in the absence of other indicators of inequality or centralized authority that developed later in the Middle to Late Preclassic periods (ca. 800–350 b.c.).

In Honduras, the site of Puerto Escondido demonstrates the development of early village life based on evidence for ephemeral structures and early pottery dating to around 1400 b.c. Subsequently, the use of ovens for pottery production is documented around 1150–1100 b.c. (Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001, Reference Joyce and Henderson2007).

Socioeconomic and Ideological Complexity

Based on current evidence, there is still much that is unknown about the socioeconomies and ideologies of the early Maya. Nevertheless, the development of greater socioeconomic and ideological complexity in Belize and the central Maya lowlands can be demonstrated by craft production, trade in exotic materials, and different forms of ritual activities, as some examples. Some lithic craft production in the Middle Preclassic likely occurred at Colha, based on the distribution of its tools, such as macroblades, bifacial celts, wedge-form adzes, and T-shaped adzes, to nearby sites in northern Belize (Potter Reference Potter, Thomas R. and Shafer1991; Shafer and Hester Reference Shafer and Hester1991). The biface and adze forms reflect an increased need for tools used for land clearance and field maintenance associated with horticulture. Lack of standardization within tool forms and the absence of identifiable workshops suggest toolmaking occurred within residences alongside other domestic activities (Potter Reference Potter, Thomas R. and Shafer1991:28). However, stone tool production exceeded the needs of the local community and production was likely organized as a “cottage industry” (Shafer and Hester Reference Shafer and Hester1991:82).

The use of drills made from burin spalls, debris from marine shell bead manufacture, and shell beads and other ornaments are represented at a number of Middle Preclassic sites throughout northern and central Belize, including Colha, Blackman Eddy, Cahal Pech, K'axob, and Pacbitun (Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Buttles Reference Buttles1992; Cochran Reference Cochran2009; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Hohmann, Powis and Garber2004; Hester and Shafer Reference Hester and Shafer1984; Hohmann Reference Hohmann2002; Isaza Aizpurúa and McAnany Reference Isaza Aizpurúa and McAnany1999; Lee and Awe Reference Lee, Awe, Healy and Awe1995; Micheletti et al. Reference Micheletti, Crow and Powis2018; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Healy and Hohmann2009; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Sullivan, Buttles and Aebersold2021). Marine shell beads have been excavated from the Middle Preclassic at sites in Guatemala, such as Tikal (Moholy-Nagy Reference Moholy-Nagy and Pohl1985, Reference Moholy-Nagy, Haynes, Ceci and Bodner1989) and Ceibal (Sharpe Reference Sharpe2019). The presence of marine shell at inland sites clearly indicates a long-distance exchange system of some kind in the Middle Preclassic.

Along with marine shell, other items made from exotic materials begin to appear in the early ceramic periods, including greenstone and obsidian. Greenstone appears in the form of polished celts, beads, triangulates, and in other symbolic or ritual forms in the Early to Middle Preclassic in Belize (Awe Reference Awe1992; Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Hammond Reference Hammond and Hammond1991a; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Hohmann, Powis and Garber2004; Micheletti et al. Reference Micheletti, Crow and Powis2018; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Horn, Iannone, Healy, Garber, Awe, Skaggs and Howie2016) and in the Middle Preclassic in Guatemala (Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Pinzón and Palomo2017a; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2006; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015). The earliest Maya obsidian tools in Belize, appearing first as hard-hammer flakes, then as prismatic blades, date to the transition from the Early to Middle Preclassic (ca. 1000 b.c.) (Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Awe and Healy Reference Awe and Healy1994; Ebert and Awe Reference Ebert and Awe2018; Johnson Reference Johnson and Hammond1991), with similarly early obsidian appearing as flakes and blades in northeastern Guatemala (Aoyama Reference Aoyama2017; Aoyama and Munson Reference Aoyama and Munson2012). In Early to Middle Preclassic Belize and Guatemala, the obsidian originated in highland Guatemala, with the El Chayal and San Martín Jilotepeque sources being dominant (Aoyama Reference Aoyama2017; Aoyama and Munson Reference Aoyama and Munson2012; Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Triadan, Pinzón, Palomo, MacLellan and Sharpe2017b; Awe and Healy Reference Awe and Healy1994; Awe et al. Reference Awe, Ebert, James Stemp, Kathryn Brown, Sullivan and Garber2021a; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Dreiss and Hughes2004; Castellanos and Foias Reference Castellanos and Foias2017; Ebert and Awe Reference Ebert and Awe2018; Hammond Reference Hammond and Hammond1991b; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Bauer, Hernández, Beach, Cagnato, Aoyama and Nasu2020: Supplementary Material 3; Kersey Reference Kersey2007; McAnany Reference McAnany and McAnany2004b; Rice et al. Reference Rice, Pugh and Nieto2019; Stemp et al. Reference Stemp, Awe, Kathryn Brown and Garber2018a). Many of these trade items made from exotic materials have been recovered from some of the earliest dedicatory and termination deposits/caches in the central Maya lowlands, often in association with one another (Awe Reference Awe1992; Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Pinzón and Palomo2017a, Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Triadan, Pinzón, Palomo, MacLellan and Sharpe2017b; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Awe, Garber, Brown and Bey2018; Garber et al. Reference Garber, Kathryn Brown, Awe, Hartman and Garber2004; Healy et al. Reference Healy, Hohmann, Powis and Garber2004; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Horn, Iannone, Healy, Garber, Awe, Skaggs and Howie2016). Deposits like these speak to an increase in the complex cultural customs among the early Maya associated with emerging socioeconomic or ideological practices that seem to presage more developed social inequality, accumulation of wealth, and power among emerging elites.