1 Introduction

Globally, women migrant workers make up 41.6 per cent of the world's estimated 164 million international migrant workers (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018). Over half of women migrant workers (53.9 per cent) originate from South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific. A significant proportion of women migrant workers also originate from sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. Over half of women migrant workers are employed in North America and Northern, Southern and Western Europe. As a proportion of the female labour force, women migrant workers also make up a high number of the labour force in the Arab states and in Central and Western Asia (ILO, 2018).

Gender plays a significant role in labour migration, influencing the reasons why an individual migrates, the migration opportunities available to them and their ultimate working conditions (Hennebry and Petrozziello, Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019). Women migrant workers are disproportionately employed for labour that is undervalued and unprotected in low-paid and informal sectors (Bastia and Piper, Reference Bastia and Piper2019). A clear example of this is the significant proportion of women working in the largely informal sector of domestic work, with women making up 74 per cent of the world's 11 million migrant domestic workers, for example (ILO, 2015). Gender inequality intersects with the low status of migrant workers, resulting in reduced bargaining power for women in the migrant labour market and precarious and insecure migration (Pearson and Sweetman, Reference Pearson and Sweetman2019).

Whereas the motivation for migration is commonly poverty and lack of opportunity at the individual or micro level, the financial benefits of migration are recognised as having the potential to positively impact the national economy of home states at the macro level (Bastia and Piper, Reference Bastia and Piper2019, p. 19). In 2019, the remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries overtook foreign direct investment, reaching a record USD $554 billion (World Bank Group, 2020). The capacity for remittances to contribute to the growth of national economies also extends to countries of destination. In the US and Europe, the impact of migrant workers on growing labour forces is recognised as having both direct and indirect benefits to the economic growth of states (OECD, 2014).

Whilst it is estimated that women's remittances make up half of global remittances (IFAG, 2017),Footnote 1 it is also understood that there are differences in the manner and impact of the contribution that women migrant workers make to development both in economic and non-economic terms. In particular, while women migrant workers typically earn less than men, they remit a higher proportion of their earnings (UN Women, 2020). This is despite paying higher transfer fees due to a heavier reliance on money-transfer business (a tendency that is related to the continued barriers facing women accessing formal banking systems) (UN Women, 2017a).

In addition, research indicates that the remittances of women migrant workers will more likely be directed towards paying for the food, education and health of family members (UN Women, 2013c; Orozco et al., Reference Orozco, Lowell and Schneider2006). This may be the result of a higher care burden (Yeates, Reference Yeates2011) or less access to the financial or productive resources that make investment possible (UN Women, 2017a). Notwithstanding the reasons, directing remittances towards supporting the health and educational well-being of individuals can have different developmental outcomes than those related to the investment in productive resources (investment for growth being the common focus of the developmental benefits of remittances) (ILO and UN Women, 2015; UN Women, 2013b).

Whilst the focus on the contributions that women migrant workers make to development is primarily limited to their financial remittances (Bastia, Reference Bastia2013), our understanding of the gendered dynamics of these contributions remain limited by lack of data. Remittance data are not disaggregated by sex and do not capture the remittances sent through unofficial channels (UN Women, 2020). In the absence of this sex-disaggregated data, the World Bank has advised that a way to estimate the true value of remittances is through representatives’ surveys of remittance senders and receivers (World Bank, 2016). At the time of writing, however, a UN Women policy brief found that only eleven countries had published nationally representative household surveys that reported the sex of remittance senders or the value of remittances received per household (UN Women, 2020).

The narrow focus on the economic benefits of migration also fails to recognise any broader interaction between women's labour migration and development, in particular in relation to social and political dimensions. These can range from the positive social and political impacts that a change in gendered power dynamics can have on countries of origin, where migration affords women the ability to be the primary earner, challenging the traditional gendered roles for them and their family members (UN Women, 2013b). Similarly, where migrant women are seen to have elevated the wealth or status of their families, or communities, they may be able to exert more agency and control over decision-making (Temin et al., Reference Temin2013). In countries of destination, the labour of women migrant worker frees up women to enter the productive labour market, which can have positive impacts on the economy and for social and gender norms (UN Women, 2013a). There are also broader impacts on families and communities at home, which would benefit from being better understood. Where women leave behind young children, they can often feel pressure to continue their care duties at home, resulting in their migration being characterised by a transnational care burden, which can manifest as an increased emotional, physical and financial pressure (Yeates, Reference Yeates2011). That such issues related to care, for example, are considered in the discourse on women's migration more so than in discourse on migration/male migration is also in itself potentially reflective of gendered notions of migration more than gendered realities (Bastia and Piper, Reference Bastia and Piper2019).

Despite the dynamics of migration and the contribution of migrant workers being gendered, migration policy and governance remain largely gender-blind, in that they do not address the different motivations, labour-market forces and normative experiences of migration (Piper, Reference Piper2006). To make migration policy governance gender-responsive, the principles of gender equality, rights and empowerment must be incorporated, and gender-based barriers to accessing safe and regular migration for decent work must be identified and proactively addressed (UN Women, 2018). Recognising and responding specifically to women's needs through migration policies is the most effective way to ensure equitable and positive migration outcomes.

Since 2015, both the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) have set out the global agenda for inclusive growth and sustainable development, and the framework for safe, orderly and regular migration tied to achieving that agenda. Together, these instruments seek to capitalise on the contributions that migration can make to positive development outcomes. In order to do so comprehensively, they need to address the gendered dynamics of women's labour migration (Bastia and Piper, Reference Bastia and Piper2019) and the multidimensional nature of the contributions that women migrant workers make to development.

This paper sets out to understand the extent to which the SDGs and the GCM recognise and respond to this need both on paper and in practice. This understanding is explored through a content analysis of selected parts of the text of the SDGs and a review of the GCM as relevant to the situation of women migrant workers. Where relevant, the content analysis and review are set alongside provisions from the international legal framework that address the promotion and protection of the rights of women migrant workers.

In analysing the extent to which the SDGs and GCM recognise and respond to the gendered dynamics of migration as it relates to women migrant workers in practice, the paper first takes a content-analysis approach to reviewing a selection of Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) submitted by states to report on implementation of the SDGs. In the absence of similar reports for the GCM, the paper looks into the mechanism established for implementation and monitoring. In both cases, the paper finds that, where the content of the SDGs and GCM provides potential to address the gendered dynamics of migration and realise the rights of women migrant workers, the indications are that this potential is not being operationalised in practice.

Finally, with a view to increasing transparency and accountability concerning the global agenda's commitment to women, the paper identifies a need: to invest in the collection and analysis of multidimensional data to inform gender-responsive labour-migration governance and interventions; and to increase the role of civil society in monitoring and reporting through the SDGs and GCM and through the bodies monitoring the relevant international legal conventions

2 Protecting women migrant workers’ rights through the global development agenda

Developed within three years of each other, the SDGs and the GCM provide a global development agenda that is elaborated to detail how to manage migration for sustainable development. Through the content analysis of selected sections, this paper looks at the extent to which the frameworks recognise and respond to the gendered dynamics of migration and seek to realise the rights of women migrant workers.

2.1 Using the SDGs as an entry point for protecting women migrant workers’ rights for development

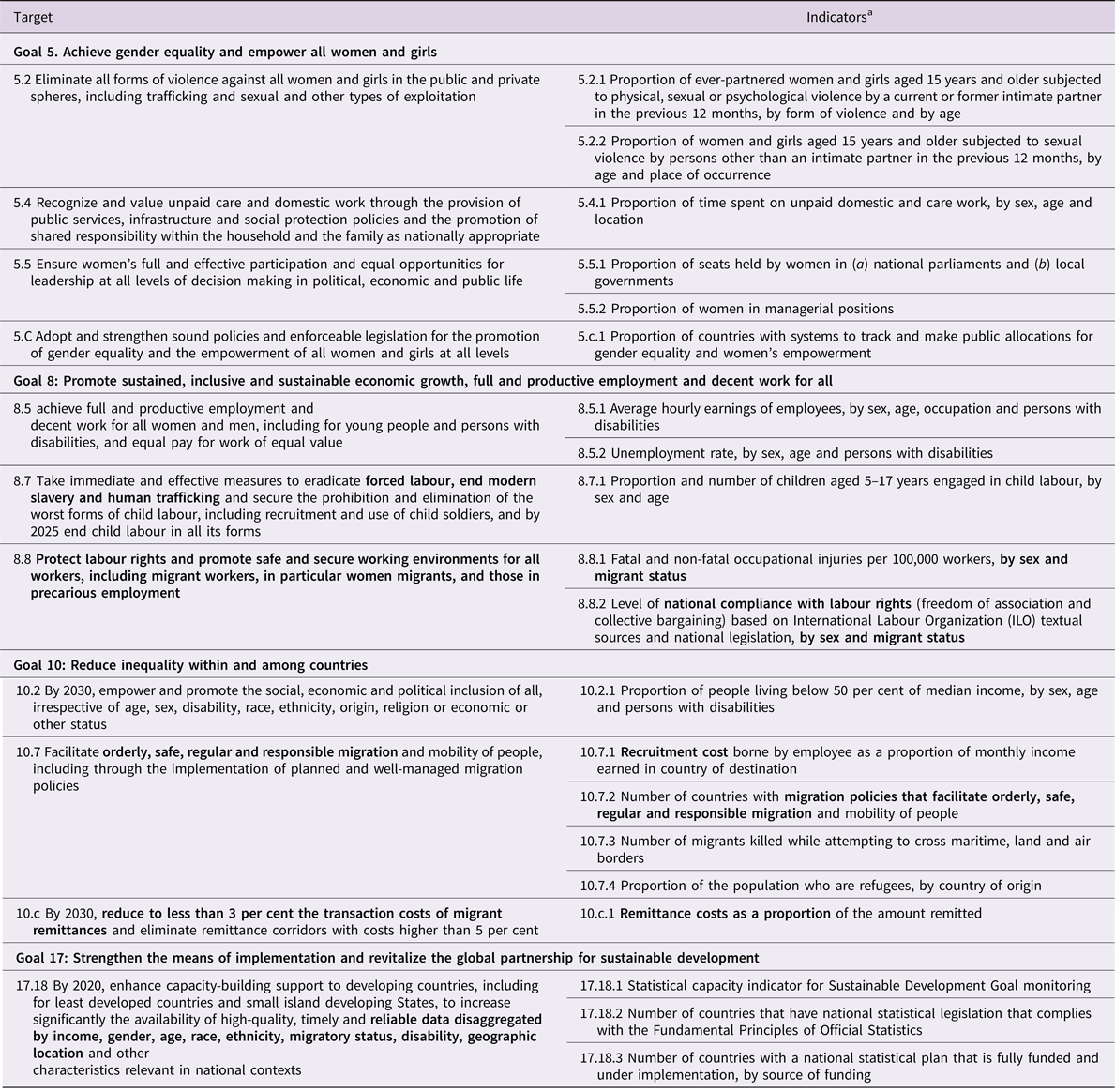

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development commits to equal access and equal opportunities for women, and to ensuring safe, orderly and regular migration for all. Despite the express recognition of the contribution that women and migrants make to development (UNGA, 2015, paras 20, 29), however, only Target 8.8 on the protection of labour rights explicitly refers to women migrant workers. Nonetheless, many of the seventeen SDGs and 169 targets are applicable to this constituency. For example, the targets under Goal 5 that relate to achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls can be specifically applied to migrants; and the targets under Goals 8 and 10 that address migrant workers can be specifically applied to women. The applicability of goals and targets to women and migrants is further promoted through the overarching instruction of the SDGs that data collection be disaggregated by certain characteristics, where relevant, including sex and migratory status. This instruction is partially operationalised under Target 17.18, which addresses the need to develop the capacity of developing countries in relation to data collection and disaggregation. The SDGs therefore set out a framework that provides the potential for states and other actors to design and implement policy interventions that realise the labour and human rights of women migrant workers, in order that women migrant workers can make their contributions to development through safe and regular migration opportunities for decent work as set out in Table 1.

Table 1. Table of selected targets and indicators from SDG Goals 5, 8, 10 and 17

a Sustainable Development Goal indicators should be disaggregated, where relevant, by income, sex, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability and geographic location, or other characteristics, in accordance with the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics.

Under Goal 5, Target 5.2 seeks to eliminate all forms of violence against women (VAW), including trafficking. A definition of VAW has been provided by the UN treaty body responsible for monitoring states parties’ compliance with the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).Footnote 2 The CEDAW Committee clarifies in its General Recommendation 19 on violence against women that discrimination includes gender-based violence – that is, ‘violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty’.Footnote 3

VAW and women's migration intersect in multiple ways and are inherently interlinked to the extent that the UN Secretary-General publishes a regular report on violence against women migrant workers, the latest being published in 2019 (UNGA, 2019b). VAW, in particular domestic violence, can be a key motivation behind women's migration (UNGA, 2019b, p. 4); it can also be a central experience of women migrants during migration. VAW can be perpetrated against migrant women by a range of actors including migration intermediaries (immigration officials, recruitment brokers), employers and institutions (including public authorities) (GAATW, 2010). It is estimated that 60 to 80 per cent of migrant women and girls travelling through Mexico to the US are raped at some stage of their journey.Footnote 4 Women migrant domestic workers are at a high risk of verbal, mental, physical and sexual abuse as well as slave-like employment conditions (UNGA, 2019b, p. 8). This risk is particularly high due to domestic workers often being the sole employee, living and working in the private residence of the employers and often unprotected by labour laws (ILO, 2016a). This risk is further exacerbated where the immigration status of the migrant domestic worker is tied to their employer (UNGA, 2019b). The particular dangers facing domestic workers, and the need to ensure that their rights are protected, resulted in the elaboration of ILO's Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (C189), which includes provisions specifically addressing the need for effective protection against all forms of abuse, harassment and violence.Footnote 5

The Secretary-General's report makes it clear that discrimination and restrictions on the empowerment of women heighten their vulnerability to violence, limit their capacity to escape potential abuse and reduce their options for regular migration, which in turn increases the likelihood of women using irregular migration channels (UNGA, 2019b). Such factors, including restrictions on freedom of movement or access to opportunities to safe and decent work, also increase women's risk of falling victim to trafficking (UNGA, 2019b), including for forced labour.Footnote 6 Forced labour itself, when the result of such gendered restrictions and limitations, can also be seen through the frame of VAW.Footnote 7

Because the gendered drivers that perpetuate women migrant workers’ risks to VAW, forced labour and trafficking are rooted in the same structural inequalities that restrict women's access to regular migration, the interventions that seek to maximise women's access to safe and regular migration for decent work can reduce risks.Footnote 8 For example, in response to reports of migrant women experiencing exploitation in domestic work, the government of Myanmar issued a ban on women migrating for domestic work. In the absence of addressing any of the root causes of migration and the structural drivers that limited women's labour migration to migration for domestic work, this ban resulted in women migrating irregularly and being more exposed to trafficking and forced labour as a result (ILO and UN Women, 2017). In contrast, Bangladesh replaced a ban on women's migration with a migration law specifically including provisions on non-discrimination; similarly, in bilateral agreements and MOUs, the Philippines provide that domestic workers receive a decent wage and have access to support services (ILO and UN Women, 2017). Interventions that increase women's access to safe and regular migration for decent work is key to reducing their exposure to exploitation, forced labour and trafficking practices.

Target 5.4 seeks to recognise and value unpaid care and domestic work. As of 2015, globally there were 11.5 million international migrant domestic workers, of whom around 8.5 million (73.4 per cent) were women (ILO, 2015). Domestic work largely continues to be seen as labour that is primarily provided by women, drawing on innate and natural qualities of caring that women are seen to process (Williams, Reference Williams, Michel and Peng2017). As a form of reproductive labour that is largely provided for free, it is not considered as having any market value (Duffy, Reference Duffy2007; Yeates, Reference Yeates2011). As a result, domestic work is both highly feminised and low-paid.Footnote 9 As women in more developed economies have been encouraged into the productive market, the demand for domestic workers has increased; this has been exacerbated by ageing societies that further increase the demand for domestic and care work that is increasingly purchased from migrant women (Holliday et al., Reference Holliday, Hennebry and Gammage2018). In seeking to recognise the value of care and domestic work, Target 5.4 provides the potential to address the value of the domestic work provided by women migrant workers by seeking to provide value to the work itself. This target has the opportunity to increase the accepted value of the labour itself in combatting the idea that, because care and domestic work is commonly unpaid, it has no value. This in turn has the potential to increase the value of this work when purchased from a domestic or care worker.

Goal 8 seeks to promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. In addressing the goal of full and productive employment, Target 8.5 includes reference to equal pay for work of equal value. The gender pay gap sees women migrant workers being paid less across the board. This is often the result of women's labour-market insertion into feminised sectors (such as domestic work) or roles that are considered as having less value. In these sectors, such as manufacturing, agriculture and construction, women migrant workers will be more commonly employed in roles considered lighter, less technical and less skilled. This equates to also being less well paid. Indeed, women's specific roles in these sectors can often be considered as secondary or subordinate to men's jobs. For example, women may be employed to sort the crop that men are harvesting (UN Women, 2017b); on construction sites, women may not even be employed in a specific job, but taken on to support and help their husbands’ employment (ILO, 2016b). In particular in agriculture, construction and manufacturing, migrant women can find that they are paid less than their male counterparts for work of equal value.

Target 8.7 seeks to eradicate forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking. As set out above, these are all issues that interconnect significantly, in particular, in relation to the structural inequalities faced by women migrants, which can leave them at higher risk of these extreme forms of labour.

As identified above, Target 8.8 is unique among the SDG targets in that it identifies women migrant workers specifically with reference to the need to ensure that workers are protected by labour rights and safe and secure working conditions. Gendered barriers to accessing safe and regular migration for decent work leave women working in precarious and insecure situations, facing multiple labour-rights abuses. These range from working in sectors (including as irregular migrants in the informal sector) that do not benefit from protection under labour law, experiencing exploitative labour conditions and lacking access to freedom of movement, association or access to support or services. The CEDAW Committee's General Recommendation 26 on women migrant workers recognises this risk and provides that states should ensure that occupations dominated by women are protected by labour laws and that such laws include mechanisms for monitoring workplace conditions, including wage and hour regulations, health and safety codes, and holiday leave (GR 26, para. 26(b)). Precarious migration and employment status can also make fear (or reality) of unemployment, arrest, detention and deportation a factor in increasing the risk of exploitation and abuse (ILO and UN Women, 2017).

Goal 10 seeks to reduce inequalities within and among countries. Towards this goal, the facilitation of orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration through the implementation of migration policies is identified under Target 10.7. Target 5.c seeks to adopt and strengthen sound policies for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women. When taken together, these two targets establish a broader target of migration policy that promotes gender equality and the empowerment of women migrant workers. The need for evidence-based, gender-responsive and human rights-based migration policies is identified as a core common responsibility for all states engaged in labour migration under CEDAW General Recommendation 26 on women migrant workers (GR 26, para. 26). Globally, the extent to which policies and programming are effectively gender-responsive is limited (UN Women, 2013b). A lack of gender-responsive migration governance can manifest as gender-based bans on migration that directly restrict the migration of women, leaving them to pursue migration irregularly and heightening their vulnerability to trafficking (ILO and UN Women, 2017). Key to developing gender-responsive policies and programmes are accurate, sex-disaggregated data. Data collection and disaggregation by sex are not, however, common practice and many sources of data on international migration do not take sex into account in collection or reporting (UN Women, 2017c).

Target 10.c seeks to reduce remittance transactions costs to less than 3 per cent and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 per cent. As discussed above, this is a particular issue for women migrant workers who continue to pay higher transaction fees to remit their earnings (UN Women, 2020). The CEDAW Committee's General Recommendation 26 addresses this need by providing that states establish measures to provide information and assistance to women to access formal financial institutions to send money home and to encourage them to participate in savings schemes (GR 26, para. 24(g)).

2.2 Addressing the gendered dynamics of migration for women migrant workers in the GCM

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration was developed in 2018 and came out of the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, which responded to the so-called ‘refugee and migration crisis’ of 2015 (UNGA, 2018). The GCM ‘rests’ on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the other core international human rights treaties including CEDAW and the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, as well as other instruments including the Trafficking Protocol and the ILO conventions on promoting decent work and labour migration (GCM, para. 2). Furthermore, the GCM is ‘rooted’ in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (GCM, para. 6). Migration is recognised as a source of prosperity, innovation and sustainable development in a globalised world, and knowledge and analysis of migration are identified as the key to improving policies that can unlock the potential of sustainable development for all (GCM, para. 10). Sustainable development is identified as one of the ten cross-cutting and interdependent guiding principles, which expresses the aim of the GCM to leverage the potential of migration for the achievement of all SDGs. Another of the guiding principles is gender-responsiveness, through which the GCM commits to ensuring that the specific rights and needs of women (in addition to men, girls and boys) are respected, properly understood and addressed (GCM, para. 15). As such, the GCM may be viewed as an elaboration of the SDGs’ global development agenda in particular in reference to the protection of women migrant workers’ rights.

The GCM expressly references gender within fifteen of its twenty-three objectives, including promoting gender-responsive remittance transfers (Objective 20)Footnote 10 and access to basic services (Objective 15),Footnote 11 as well as expressly acknowledging gender-specific risks such as sexual and gender-based violence (Objective 7)Footnote 12 and issues such as women migrant domestic workers (Objective 6).Footnote 13 The GCM's objectives go further than identifying just those issues that directly impact the rights of migrant workers (and, for the purposes of this analysis, specifically women migrant workers) by including objectives that have an indirect impact through addressing the broader structural environment that influences migration experiences.

The first objective of the GCM is to collect and utilise accurate and disaggregated data as a basis for evidence-based policies. This objective sets out eleven actions, including: elaborating and implementing a comprehensive strategy for improving migration data; building national capacities; integrating migration-related topics into national censuses as well as labour and household surveys. This critical connection between the systematic collection and analysis of labour and migration data and research, and the development of evidence-based labour-migration policy and practice is identified in the CEDAW Committee's General Recommendation 26, which further provides that data be disaggregated by gender and other relevant characteristics (GR 26, para. 23(c)).

In calling for minimisation of the adverse drivers and structural factors that compel people to leave their country of origin, Objective 2 speaks to the factors that may make women's migration a necessity, not a choice, including poverty and violence. In framing this objective around structural factors, the GCM provides the scope to address the broader environment of discrimination and inequalities that influence women's motivation to migrate and the increased risks associated with migration by necessity.

Providing accurate and timely information at all stages of migration, as provided for under Objective 3, and enhancing the availability of regular migration pathways can also be particularly relevant to women migrant workers. Research for Viet Nam, for example, indicates that the majority of information accessed by women before migration is from friend and family networks and recruitment actors (many of whom are unregulated), which results in potential migrants receiving unreliable information that can lead them into irregular pathways (Harkins et al., Reference Harkins, Lindgren and Suravoranon2017). In this scenario, the ability to access accurate information and regular pathways is greater for potential men migrants.

Objective 23 concerns the strengthening of international co-operation and global partnership for safe, orderly and regular migration. It calls for the application of a human rights-based, gender and disability-responsive approach in reviewing relevant policies and practices to ensure that they do not create, exacerbate or unintentionally increase vulnerability of migrants. Furthermore, it requires the development of gender-responsive migration policies (GCM, para. 23(a), (c)).

To the extent that the GCM further elevates gender and women migrant workers’ rights in the global development agenda, this has been linked with the advocacy efforts of civil-society organisations, supported by international organisations such as UN Women and the ILO (Bastia and Piper, Reference Bastia and Piper2019; Hennebry and Petrozziello, Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019). Equally, however, where the GCM has not taken the opportunity to more expressly strengthen the rights of women migrant workers (e.g. through calling for access to sexual and reproductive health care), this has been linked to the need to secure agreement from states with more conservative views on gender and women's rights (Hennebry and Petrozziello, Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019). Additionally, the narrow focus on economic remittances as the key contribution to development is a missed opportunity to reflect the broader contributions that women make to sustainable development (Hennebry and Petrozziello, Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019), for example through their social and political remittances.

3 Addressing the gendered dynamics of migration for women migrant workers through the SDGs and GCM in practice

The SDGs and GCM together comprise a global development agenda that reinforces the positive role that women migrant workers play in their contributions to sustainable development and elaborates a framework for the protection of their rights towards the goal of sustainable development. On paper, this framework provides states with the potential to strengthen data collection and analysis towards establishing evidence-based and gender-responsive migration-governance frameworks. This paper now turns to looking at whether, in the five years since the SDGs were established and the two since the GCM, this potential has been realised in practice.

3.1 Addressing the gendered dynamics of migration for women migrant workers through implementation of the SDGs

The SDGs took a new approach to measuring implementation of a global agenda. Rather than reviewing implementation at the global level, the SDGs introduced a ‘country-led’ approach to collecting and measuring data. This approach manifests through VNRs and was intended to recognise country ownership of interventions and results, and promote accountability to citizens (UNGA, 2015). The principles guiding follow-up and review included provision that the reviews focus on the poorest, most vulnerable and those furthest behind (UNGA, 2015, para. 74(e)).

The primary method for monitoring results against the SDGs is by collecting and reporting data against the indicators included in the SDGs (UNGA, 2017). Where the language of the goals and targets of the SDGs provides the potential to better understand and address the situation of women migrant workers, the language of the indicators often narrows this potential. An example is Target 5.2, where the target itself makes reference to trafficking, but the language of the indicators refers to intimate-partner violence and non-intimate-partner sexual violence. Reporting against these indicators would not invite, therefore, any data on trafficking unless the act itself involved intimate-partner violence or sexual violence. Even then, the reporting would more accurately be described as reporting data on violence in trafficking, rather than trafficking itself. Similarly, references to forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking are not present in the indicators for Target 8.7, which focuses entirely on child labour. A review of the indicator language reveals in fact that there are only five indicators that require provision of any data relevant to women migrant workers. The indicators under Target 8.8 measure the number of occupational injuries and the level of national compliance with labour rights, expressly by sex and migrant status. The indicators under Target 10.7 measure data on the cost of recruitment and the number of countries with migration policies. Indicator 10.c.1 measures the cost of remittances as a proportion of the amount remitted. The disaggregation by sex and migrant status under the indicators under Goal 10 is not expressed, but implied under the general instruction for data disaggregation.

An important element of the VNR approach is that it gives countries the ability to identify the targets that they will focus on. In the first four years of implementation, 158 VNRs were submitted by 142 states (UNDESA, 2019). The voluntary and optional nature of the VNRs, coupled with the limited number of indicators that actively measure progress for women migrant workers, presents a potential scenario in which no states measure data on the progress of women migrant workers. Indeed, a keyword search for ‘migration’ in the Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform that houses the VNRs returns seventy-four VNRs. This indicates that only half of the VNRs have any likelihood of measuring progress for women migrant workers. Of the indicators that could be applied to women migrant workers, only half of them require data collection disaggregated by sex and migrant status, further reducing the potential that these data will be collected.

Ultimately, whilst the SDG targets can be taken together to create a framework with the potential to promote and protect the rights of women migrant workers, the details of the indicators and voluntary nature of reporting may mean that women migrant workers are excluded from SDG implementation at the national level or that the interventions benefiting them are not reported. With the situation of women migrant workers making them some of the most excluded from society, this goes against the very core intention of the SDGs to ensure that no one will be left behind and to endeavour to reach the furthest behind first.

To get a sense of how the SDGs are being applied in practice, this paper reflects on a content analysis of the VNRs reported against the SDGs in the five years since adoption, using key search terms to identify and illustrate the scope of application to women migrant workers. Content analysis is a method of research that examines the content of texts to identify characteristics embedded within messages (Holsti, cited in Kassarjian, Reference Kassarjian1977). These characteristics can be analysed to draw inferences as to the intention and objective of the text. The analysis used here is largely content analysis in its simple form, collecting and then analysing data based on word frequency. It does, however, extend in places to focusing on what conclusions can be drawn from the presence of words in the context of the text (de Sola Pool, Reference de Sola Pool1959).

The content analysis looked at twenty countries that have submitted reports since 2015. The country selection was based on (1) whether the country had reported, (2) whether the country was (or had recently) experienced significant inward or outward migration and (3) the geographic location of the country (in order to achieve a geographic spread). The author as a practitioner in migration was primarily able to identify countries with significant labour-migration dynamics and follow-up research (including media and UN and development actor reporting) confirmed whether these were countries that were experiencing migration contemporaneously as a country of origin or destination. The countries include ten countries that are predominantly countries of origin for migrant workers and ten that are predominantly countries of destination. The countries broadly cover the range of continents and include countries from the Global North and the Global South. One methodological limitation is that the content analysis was only undertaken in English, meaning that countries reporting in French and Spanish were not selected. This resulted in the countries of origin being more weighted to South and Southeast Asia than countries in Africa and Central and South America. The ten countries of origin included in the content analysis were Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Viet Nam. The ten countries of destination were Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Qatar, Singapore and Turkey.

The data collection asked two questions. The first was: To what extent do the VNRs include data against the selected indicators disaggregated by migratory status and sex (the indicators being those identified above, namely, 8.8.1, 8.8.2, 10.7.1, 10.7.2 and 10.c)? The first question sought to identify VNRs where the state had chosen to report against these specific indicators and, further, where they had chosen to disaggregate the data reported by sex and migrant status. The second question was: To what extent are references to migrants or migration in the VNRs gender-neutral or specifically referring to women? For this second question, the data were collected through content analysis of the VNRs looking for specific words. The first set of words were ‘migrant’ and ‘migration’. Subsequent reviews included the words ‘foreign’ and ‘overseas’. These four words were used to identify the paragraphs and sections in the VNR narratives and data reporting that referenced migrants. The analysis made note of each episode in which there was reference to migrants and migration (or foreign or overseas, where relevant to migration). An episode was considered as a section of text that contained either a single reference or multiple references – that is, where the word was repeated in a paragraph, this was counted as one episode. The episode was then subject to a second layer of analysis, which was to identify whether the episode was gender-neutral or whether it included specific reference to women. The results are set out in Table 2.

Table 2. Content analysis of twenty Member State Voluntary National Reviews of SDG implementation

a The entire ‘Migrants’ section is gender-neutral.

b Search term ‘Overseas’ was also applied.

c Search term ‘Foreign’ was also applied.

d Search term ‘Foreign’ was also applied.

3.1.1 To what extent do the VNRs include data against the selected indicators disaggregated by migratory status and sex?

The overall finding under this question was that none of the reviewed VNRs included any data against the selected indicators, either at all or disaggregated by migratory status. Put another way, there were no data reported on the number of occupational injuries experienced by migrants (indicator 8.8.1) and no data reported on the level of national compliance with labour rights as related to migrants (indicator 8.8.2). There were also no data on the recruitment or remittance costs (indicators 10.7.1 and 10.c.1, respectively) and no data on migration policies (indicator 10.7.2). In the absence of data on migrants, there were as a consequence also no data on migrants disaggregated by sex.

For the countries of origin, half of the VNRs included no data reporting at all or none under SDG 8 or 10. For those countries of origin that did include reporting of data under SDGs 8 and 10, there were no relevant data on migrants or against the indicators specific to migrants. For SDG 8, this was not particularly surprising, as the indicators related to labour rights, meaning reporting was limited to labour conditions for nationals. For Goal 10 indicators, however, it was reasonable to expect some level of reporting around recruitment and remittance costs – issues that are particularly relevant to countries of origin. Where countries did reference remittances, this was in relation to measuring remittance as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and not measuring how much migrants themselves were paying to remit money. Indeed, in this regard, the majority of country-of-origin VNRs identified the importance of remittances to their GDP.

For countries of destination, seven included no specific data at all. Of the three VNRs that included data against SDG indicators under Goals 8 and 10, none reported any specific data on migrants or against the indicators specific to migrants – that is, in relation to Goal 8, the data reported were not disaggregated by migrant status and so did not identify the extent to which they related to migrants; and, in relation to Goal 10, the data were reported under the indicators that did not relate expressly to migrants and were not disaggregated by migrant status against the indicators that were reported against.

For the countries selected for this analysis, we can see that there was none that selected to report data related to labour migration, whether disaggregated by sex or not. Given the migration dynamics of the selected countries, this is surprising. It would be useful to undertake further analysis to understand whether there are data relevant to the indicators that are not being reported or whether there are just no data for those indicators. In any event, this does illustrate low levels of reporting related to labour migrants’ rights, facilitation of safe regular and responsible migration, and reduction of remittance costs under the SDGs.

3.1.2 To what extent are references to migrants or migration in the VNRs gender-neutral or specifically referring to women?

The overall finding from this question was that, whilst the majority of VNRs included reference to migrants, migration or foreign (sometimes overseas) workers, references were largely gender-neutral. Only a few episodes made specific mention of women.

For the countries of origin only, one country's VNR featured no episode including the search words (migrant, migration or foreign). One country had only one episode. The other eight country VNRs had multiple episodes including the search words, at between four and nine episodes. Of these episodes, 50 per cent or over were gender-neutral, meaning that they referred to migrants or migration with no specific reference to gender or the sex of migrants as a variable or issue relevant to the topic. In the VNRs of three countries of origin, all of their episodes were gender-neutral. Half of the country-of-origin VNRs made some specific reference to women in the context of migrants and migration but references to both women and migration were limited to two episodes per VNR.

Of the references to women migrants that were identified, three references were to gender-responsive responses through policies and programmes. Other references to women migrants included their ‘exposure’ to unsafe migration and the impact of women's outward migration on the need for greater social care in countries of origin. References to addressing remittance systems were gender-neutral. This indicates that, where states are considering gender in their implementation of the SDGs on migration, it is largely limited to addressing the needs of women as victims of migration (i.e. victims of exploitation, forced labour or trafficking) or women as carers. These are both common gendered frames for the way in which women in migration are viewed and, whilst they may relate to interventions that are realising the rights of women, it is likely to be in a protective and restrictive way. It is the three references to gender-responsive policies and programmes that have the most potential to realise women's rights in terms of realising human and labour rights in a way that manifests as greater access to safe and regular migration for decent work.

For the countries of destination, only one country's VNR featured no episodes including the search terms. Of the remaining nine, all included multiple episodes (three VNRs included two to three episodes; four included six to seven episodes; and two included 12 and 14 episodes). Of the nine VNRs with multiple episodes, between 80 and 100 per cent of episodes were gender-neutral in eight of the reports – that is, the majority of episodes referencing migrants or migration were gender-neutral. Out of the ten VNRs, five VNRs included episodes that made specific reference to women. Of these VNRs, three included just one episode that related to women and two included three episodes. The majority of the references to women migrants related to responding to their health and social needs. One VNR included specific reference to strengthening laws for migrant domestic workers. The inclusion of reference to the health and social needs of women migrant workers is certainly not a negative; it is noticeable, however, that, for countries of destination that could be addressing the labour-market insertion and labour rights of women migrant workers, only one VNR addresses this.

3.2 Addressing the gendered dynamics of migration for women migrant workers in the GCM

The GCM provides a non-legally binding framework to facilitate international co-operation among all relevant actors on migration (GCM, para. 7). Whilst the Compact rests on the main international human rights law instruments and is to be implemented in a manner that is consistent with international law (GCM, paras 2, 41), nothing in the GCM creates any additional legal obligations on states (Carrera et al., Reference Carrera2018). Instead, the GCM is considered a ‘menu of policy actions and best practices, from which States may draw’.Footnote 14 The GCM does, however, establish frameworks for both implementation and reporting. The UN Secretary-General is directed to establish a UN Network on Migration (GCM, para. 45) to ensure effective and coherent system-wide support to implementation, including through the establishment of a capacity-building mechanism that allows stakeholders to contribute technical, financial and human resources to strengthen capacity and foster multipartner co-operation (GCM, para. 43). In terms of reporting, states are directed to report at the International Migration Review Forum (IMRF), which shall take place every four years and serve as the primary inter-governmental platform for states to discuss and share progress on all aspects of the GCM, including as it relates to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (GCM, para. 49). States are also encouraged to develop national responses for the implementation of the GCM and to conduct regular and inclusive reviews (GCM, para. 53). There is no express reference to gender-responsive implementation or monitoring in the Implementation or Follow Up sections of the GCM.

Tasked with the mandate to ensure system-wide support to implementation, the UN Migration Network (led by the IOM) will play a key role in identifying priorities for operationalising the GCM. Incorporating a proactively gender-responsive approach to the work of the Network will be critical in ensuring that implementation meets the needs of women migrant workers. As identified by Hennebry and Petrozziello (Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019), however, the absence of UN Women from the core group of UN agencies in the Network may prove problematic. This is especially the case in view of the role that UN Women has played in making space for civil-society organisations to raise the unrepresented voices of migrant women at the international level (Hennebry and Petrozziello, Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019). In addition, neither the resolution on the IMRF (UNGA, 2019a) nor the Migration Multi-Partner Trust Fund has identified proactive gender-responsive work streams or funding. The structure for the IMRF is based on four roundtables that cover multiple GCM objectives (UNGA, 2019a). These four groupings of objectives also form the basis of the survey conducted to inform regional review of implementation.Footnote 15 The four categories are (1) ensuring that migration is voluntary, orderly and regular; (2) protecting migrants through rights-based border governance; (3) supporting the integration of migrants and their contribution to development; and (4) improving value-driven and evidence-based policy-making and public debate, and enhancing co-operation on migration. The extent of the reporting state's integration of the guiding principles (including gender-responsiveness) into implementation is dealt with through a list of boxes to be ticked, with a request for further information – that is, tick yes or no to whether the guiding principle ‘gender-responsive’ has been integrated and then provide an explanation of the integration.

The extent to which the reporting state has taken a gender-responsive approach to implementation of the GCM is ultimately treated as a separate and standalone element of implementation; there appears to be no expectation to report how implementation under each of the objectives of the GCM is gender-responsive. The setup of this survey may be indicative of the approach that will be taken to operationalising the GCM objectives themselves, namely with gender-responsive as an ancillary issue. If Hennebry and Petrozziello (Reference Hennebry and Petrozziello2019) are correct in their suggestion that the language on gender-responsiveness in the GCM is further ahead than the knowledge base and capacities for implementation, then the separate reporting of gender-responsive implementation will do little to compel states to improve such knowledge base and capacity. The consequence of this will likely be ‘business as usual’, with implementation of the GCM as regards women migrant workers being both minimal and piecemeal.

3.3 Data collection and accountability

In the case of both the SDGs and the GCM, operationalising the agenda for women migrant workers could benefit from improving both the evidence base and the reporting. Evidence-based governance has been identified as key to sustainable development and not possible without sufficient, reliable statistics to identify need and monitor progress (UNFPA, 2014). Placing a greater priority on states collecting and analysing data disaggregated by sex could help to identify where there are gaps in implementation and ensure that policy and practice developed to operationalise the agendas are evidence-based. As identified by the Head of the Demographic and Social Statistics Branch of UN Statistics Francesca Grum, there remain several critical challenges to be addressed in filling the data gaps, including insufficient capacity on the part of states to produce, analyse and communicate data.Footnote 16 Specifically, the need to improve sex-disaggregated data was identified by the OSCE as essential to promoting the right of women migrant workers.Footnote 17 The need for a ‘gender data revolution’ has been met with some suspicion by feminist scholars who are concerned about a narrow focus on measurement; it may indeed be that the methodologies of data collection for evidence-based policy may need to be assessed to ensure that the complexities of gender subordination are captured (Fuentes and Cookson, Reference Fuentes and Cookson2019). At the moment, however, the indications from the SDG reporting and the GCM framework for reporting are suffering from a lack of gender data, resulting in gender-blind operationalisation of these two frameworks and, as a result, the global development agenda.

In the context of the GCM implementation and review, the UN Network on Migration set six Thematic Workstream Priorities, one of which is to develop and implement a global programme to build and enhance national capacities in data collection, analysis and dissemination.Footnote 18 Identified in a list of potential future thematic work streams is developing a global programme to strengthen migration-related data, disaggregated by sex, age, gender, disability and other grounds, and collect gender statistics. There is no current timeline for this work stream, its development being dependent on the Network's capacity expanding or completion of current work streams. In 2019, UN Women produced a snapshot of gender equality across the SDGs (UN Women, 2019). The analysis across countries demonstrated the intersecting nature of the forms of discrimination and disadvantage experienced by women. Disaggregation of data by sex alone often fails to adequately reflect the groups of women and girls who are most deprived (UN Women, 2019). UN Women advocate for a multidimensional and multisectoral approach to data collection and analysis, accompanied by qualitative work to understand root causes (UN Women, 2019). They further recommend investment in high-quality and timely data that are disaggregated across sectors and layers. In operationalising the thematic work stream on disaggregated data, through this multidimensional and multisectoral lens, there may be an opportunity to strengthen data that can effectively inform evidence-based gender-responsive migration governance.

It has been observed that VNRs are often seen as a hasty attempt to pull together a report to present in New York, rather than a true reflection of national efforts to implement the SDGs (Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2017). Similarly, the role of civil society in the preparation of the VNRs is described as being one of ‘variability’ (ODI, 2018). The nature of reporting may, therefore, result in efforts to address the rights of women migrant workers and opportunities to engage in national dialogue on these matters being missed. One suggestion is to make the cycles of VNR reporting clearer to national stakeholders, along with a system to engage in the reporting process (ODI, 2018). Such a system could be informed by the shadow reporting practices that accompany the submission of national reports by states parties to the UN treaty bodies that monitor states’ compliance with the human rights treaties they have ratified. In the case of the CEDAW Committee reviews, civil-society shadow reporting has been seen to increase the likelihood of recommendations addressing women migrant workers’ labour and human rights (Elias and Holliday, Reference Elias and Holliday2018). Effective engagement of a broad range of stakeholders, especially civil-society actors, in the monitoring and reporting of GCM implementation could improve the extent to which states are held accountable to the GCM's commitments to gender and women migrant workers’ rights.

4 Conclusion

The analysis in this paper shows that, whilst both the SDGs and GCM establish a global development agenda that provides the potential for states to strengthen their evidence base to establish gender-responsive migration policies, this potential is not being realised in practice. This is in part due to the voluntary nature of implementation and reporting that has resulted in many key migration countries including limited reference to migration in their reviews, with only a handful making reference to women migrant workers or gender-responsive policies and programmes. That the GCM requires reporting on the extent to which implementation is gender-responsive as separate from the reporting under the objectives essentially siloes that reporting. The siloed nature of the ‘gender-responsive’ guiding principle in reporting on GCM implementation is likely to result in a continuation of the trend that implementation of the GCM as regards women migrant workers will be minimal and piecemeal.

A focus on improving capacities for multidimensional data collection and analysis may be one way of gaining greater understanding of the situation of women migrant workers and their contributions to development. This can in turn guide migration governance. In addition, greater transparency and inclusion, especially of civil-society and non-government actors, when it comes to the VNRs under both the SDG and GCM frameworks could result in a constructive shadow process, akin to that used to complement states’ reports to UN treaty bodies. In any event, further research and discussion are still needed on how to realise the rights of women migrant workers through the development agenda. We know enough to know that, if we are ignoring the dynamics of women's labour in our development agendas, the aspiration of inclusive growth and sustainable development will remain just that.

Conflicts of Interest

None. The author is a Member of the Expert Working Group on addressing women's rights in the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration and was involved in drafting the Recommendations for Addressing Women's Human Rights in the Compact. The paper is written in the author's personal capacity and the views expressed do not represent the views of the Expert Working Group.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is extended to Alan Desmond for bringing these papers together and for editorial support.