Introduction, Rationale, and Methodological Approach

With the advent of the first urban century, when more than 50 per cent of the world's population since 2008 has come to live in cities (UN Reference United2008: 2)—those centres of intense societal flux and renegotiation of identities, racial identification, and territoriality continue to remain a source of both security and contestation among nation-states. In Southeast Asia, whose populations share in the prosperity brought by the growth of neighbouring East Asian economies, questions of cultural reach and hegemony resurface sooner or later as against the homogenising influence of those still-hazy twin phenomena of globalisation and urbanisation (Douglass Reference Douglas2000: 2315). In particular, countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, despite their occasional spats over emergent national space (e.g. the 1963–1966 Konfrontasi) or cultural icons (e.g. protests in Indonesia in 2009 over Malaysia's accidental use of the Balinese Temple Dance pendet, among other artefacts) (Chong Reference Chong2012: 2–3), remain relatively secure with their shared regional identity and their largely mutually-intelligible forms of Bahasa. Their language and similar icons are also used by nearby smaller states like Singapore and Brunei Darussalam, which partake too of the Dunia Melayu that stretches from the Straits of Melaka (Malacca) to Irian Jaya.

However, when such issues of identity, of being Malay (or Mongoloid, or Caucasian-Semite for that matter), have tended to calcify in a globalising context of national borders chafing against mongrel regions where neither identity nor homeland has ever predominated, sooner or later, a countervailing movement emerges. Such movements, led by critical scholars or revolutionaries, inspire radical rethinking, and may later instruct institutional, educational, and societal reform. This is especially true when the roots of problematic state-defined (and therefore relatively recent) identity-labelling prove to be more pliant when assailed. Such sociocultural roots may have even been more geographically dispersed during colonial and precolonial times, thus still holding potential for the regeneration of a different understanding of place-based citizenship or cross-border affinities versus recent jingoist social engineering. This study locates itself in that countervailing surge by calling for a more expansive historical and geographical investigation of an age-old Malayness, as it may have applied, and still does, to a particular nation-state at the regional periphery of the Malay sphere.

If one were to take the longer view as the case in point of this study and eschew more recent nationalisms that are defined narrowly, the Malay world, arguably, has had at least one other member,Footnote 1 the Philippines. The Filipinos, it shall be shown, have often thought of themselves as Malay, and as rooted in a bygone Malay world (without prejudice to the present one), either as a result of historically-recognised physiological and linguistic affinities with their neighbours, the relations of their Muslim minorities to the latter's kindred polities, past inter-governmental rapprochement, or because of post-independence formal education and diplomatic discourse.

Why should this matter? From a research perspective, at least three grounds are germane to problematising the assertion that the Philippines and its peoples have shared in and continue to qualify as subjects for discourse on the still-inchoate Malay region:

(1) First, there was, and arguably, there still is, a corpus of Spanish works (apart from colonial records in the yet not-fully-digitized Archives of the Indies in Seville, as well as related Portuguese accounts like João de Barros’ and Tomé Pires’ chronicles) dating from at least the seventeenth century that was written by “Malayistas” (e.g. De Rivadeneyra Reference De Ribadeneyra1601; De Morga Reference De Morga1609; Retana Reference Retana1891). These writings showed Iberian understandings of Malayness and were well-established as a skein of valuable historical and anthropological discourses by the nineteenth century, when emerging native Filipino literati began to adopt and selectively challenge the discourses of such Iberian Malayists and other Europeans (Donoso Reference Donoso2016: 414). For the purposes of this article, it has been observed that this corpus faded into obscurity, sustained by dwindling works of Hispanic Filipinistas and latter-day Filipinologists who made the linguistic transition to English letters, precisely when Spain lost territorial control of the Philippines in 1898 (this author's emphasis). If, therefore, present experts consider canon-building to be de rigueur for the perpetuation of Malay discourses, then a space should be reopened for this scholarly tradition, which cannot be separated from its geographic bases, the Philippines and short-lived Iberian settlements in the Moluccas (Spain) and Formosa (Spain), not to mention Melaka (Portugal) and Timor Leste (Portugal).

(2) Second, vis-à-vis the not-uncommon prefatory admission that borders of the Malay world are difficult to fix (Milner Reference Milner2008: x, 1, 10; Barnard and Maier Reference Barnard2018 [2004]: ix), the Philippines has never lain wholly outside nor too distant from the putative domains of Malay culture, as even a layperson can conclude by looking at maps. This makes it unconvincing and debatable as to why “Straits Malayness” (to borrow from Collins: 168, in Barnard Reference Collins and Barnard2018 [2004]) and polemics on Malay studies should end at an invisible geographic curtain drawn between the Philippine archipelago and the former Dutch East Indies and British Malaya. Even lead voices in anglophone scholarship on Southeast Asia (e.g. Reid Reference Reid2010; Andaya Reference Andaya2008) inevitably mention the Philippines in passing, or include its southern reaches in their maps of the Malay world or the colonies that would come to define the latter (e.g. Barnard Reference Barnard2018 [2004], and Milner Reference Milner2008 respectively). Yet little else is said in-depth about the Philippine archipelago's pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial relations with other Malay polities, even if spatially, Mindanao in the southern Philippines was barely farther from the Malaysian and Indonesian sides of Borneo than Singapore, and the southwest territories of Sulu lay “below the wind” (i.e. within the leeward direction, or equatorial doldrums), which would then qualify the latter's inhabitants as subjects of Malay negeri, following current scholarship (Rivers Reference Rivers2005: 1–2, 8–11; Milner in Barnard Reference Barnard2018 [2004]: 242–243). Pursuant to logics of geographic proximity, areas that would later become part of the Philippines should be given a fair hearing of evidence, if only to complete the regional picture's northeast quadrant and tell the story/stories of how they separately or collectively lost, gave up, or retained some of their links and claims to Malayness.

(3) Third, a complete narrative requires at least one setting. However, different narratives demand more or wider settings. Responding to the work of Curaming (Reference Curaming, Mohamad and Aljunied2011), who attempted to historicise the Filipino identity versus narrow conceptions of Malayness, and noting a lacuna in anglophone Malay Studies that treats of historic geopolitics and emergent identities-in-space as applied to the Philippines, this study pushes the case for a physically-expanded Malay world based on the longevity and locations of Malayness in the experience of the populous Filipino ethnie (after Smith Reference Smith2008: 19, 30). A central problem is that relatively non-rigid phenomena like ethnicity, along with language and other group markers are seldom identified by others in their core geographic locations (unless approached from the air, which was impossible till the twentieth century). They are rather progressively “discovered” by foreign investigators starting from the periphery, where ethnicity fades away rather than disappears abruptly. Since learning has proceeded by moving from a still-relatable edge to a putative centre, this can be the basis for challenging the later sloughing-off of the periphery, once the core—in this case, of Malayness, has been found and fixed by some researchers. This article strengthens the view that scholarship must be brought to bear on the idea of the Philippines as part of a region in which Filipinos could be or were once considered as a part of the story of the Malays. This is necessary to provide a locus either to the attempt to impose a single narrative (to see events as linked and to impose a conceptual unity and inevitability in history—say culminating in Straits Malayness, with Philippine Malayness being shed along the way), or to provide different or counter-narratives (to emphasise specificities because of discontinuities, including a Philippine chapter or story).

From a more practical and present-day standpoint, Malay essentialists may wish to reconsider that Filipinos collectively make up the other “elephant in the room” by literally taking up geopolitical space in a region where shifting understandings and disputed appropriations of being Malay seem confined to the spaces that emerged from the former British and Dutch colonial territories. Though it may appear transgressive, this article reminds the reader that whether or not privileged circles allow the core issue (that the Filipino is, or was Malay, somewhere) to be scrutinised, reality on the ground can overtake debate in startling forms, such as in the way intellectual discourses have sprouted around the limited analogies of Turks being European, or Cape Malays being African—which have in other countries and epochs, become the basis for the real phenomena of discrimination and unequal resource allocation. If other scholarship (Ricci Reference Ricci2013; Beaujard Reference Beaujard2011) has ventured to push the geographic limits of even a vestigial Malayness to the Indian Ocean and Africa's southern seaboard, then certainly, for the sake of thoroughness, academic debate on the still modest corpus of Malay studies should not exclude a push northeastward, accompanied by a discussion of Philippine dynamics, if only to respond to the clarion call as enunciated by Curaming's writings.

Just to appreciate how large this Philippine “elephant in the room” is, one must consider that not even counting their substantial diaspora communities, there are over 102,250,000 Filipinos living in the 300,000 km2 that make up the Philippines (over 341 persons per 1 km2), most of whom have been formally enculturated to appreciate, if not assert, their “Malay” roots. This may be opposed to approximately 30,752,000 Malaysians in 330,396 km2 (some 93 persons per 1 km2) 5,697,000 Singaporeans in 718 km2 (about 8,310 persons per 1 km2), and 429,000 Bruneians in 5,765 km2 (over 74 persons per 1 km2), who altogether make up roughly 36,878,000 Malays under the somewhat exclusive Muslim-Malay label, with the foregoing figures based on the latest completed updates (c. 2016).Footnote 2 By sheer numbers alone, Filipinos of whom some 80 per cent are Christianised (say 80,000,000) cannot be written off as an insignificant presence making claims to Malay identity, and a non-Islamic one at that, whether now or in the recent past. Rather, they have the potential to overturn present definitions, and as a sovereign nation they may not be dictated upon to shake off their partiality for the Malay co-label. They far outnumber any exclusivist populations, and though their archipelago may seem perched off-centre from the Malay-centric equator, it projects an invisible tug, like a black hole in space, in the form of fleeting but persistent declarations that lay notional claim to a thoroughgoing Dunia Melayu, and whose gravity signals a need for academic enlightenment.

As a Southeast Asian people who inhabit an older Westphalian-type nation-state, Filipinos have tended to be prolific and peripatetic, migrating from country to country, in the same way as the ancient Malays from whom the Filipinos claim descent. Others have nevertheless denied their connections with those ancient Malays. As for the other roughly 260,581,000 Indonesians, most of whom are also Muslim, hence fitting a current Malaysian definition of “who is Malay”, their leaders do not dispute too vociferously the Philippine claims. This is also perhaps because their society tends to be comfortable in Indonesia's own melting pot traditions. Or rather, as a reviewer of this paper put it, it would be more correct to say that their leaders, along with those of Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei, have tended to ignore or trivialize Filipino claims while growing accustomed to their own home-grown citizen-labels. Nonetheless, to ignore the identity claim of the hundred millions of marginalized Filipinos, as problematised in scholarly discourse, is to signal a lack of comprehensiveness—in so far as it ignores the extant scientific and non-English archival literature of a people who have consistently seen themselves at some level, in their home territory, as Malay, both in verifiable emic or etic accounts. It is to be dismissive of a potential source of comparison and understanding of the manner and reasons for which identities are formed, negotiated, shared, and perpetuated backward or forward through space and time.

Given the foregoing grounds and aim of this research, the author developed a geohistorical framework in which the following are embedded: (1) a review and constructive critique of the work of R. Curaming, who is a current voice in Southeast Asian studies for the analytics of the Filipino as Malay, to which this work adds reasons for appending the Philippines to the problematised terrain; (2) a listing and commentary on selected historical sources of the label “Malay”, especially as found in Iberian sources and ascribed by outsiders to Filipinos and their fellow-ancestors versus practices of self-ascription in space; (3) persistence of Hispano-Filipino appropriations of Malayness through the American and post-colonial periods, not only in its older racial-descriptive sense, but also by nationalists who followed the differing trajectories of states in insular Southeast Asia; (4) the fact of Muslim polities in Mindanao with a history of links to the Straits area, geopolitical contestation, and negotiation of identities; and (5) a commentary on post-colonial policies and educational instrumentation of the Malay identity in the Philippine diplomatic and geopolitical contexts. An analysis and discussion of the implications of relocating or collocating a Filipino version of Malayness follows, as a logical consequence of accepting an expanded regional understanding of places and spaces inhabited by Malays.

Review of Related Literature

Of Space, Difference, and Inequality

This study opens its theoretical frame with two concepts that relate geospatial and sociological identity. The first is the idea of third space as elaborated epistemologically by Homi Bhabha (Reference Bhabha1994) and spatially by Edward Soja (Reference Soja1996), and refers to that expression of difference, or of cultural positionality in a specific space and time that can be construed as a performance of hybridity. This third space links the I and You in language but is itself an ambivalent space of enunciation that breaks away from hierarchical claims of purity in cultural discourse. In this study, different situations and assertions of those who claim Malay identity can be shown to be constitutive of, or in flux in such a third space, or a regional space of encounter, where an amalgamated sense of self has undergone long exploitation by different colonisers and post-colonial states and whose geospatial realm has been the South China Sea (which itself is a contested term today). In so far as it is a region of overlap named in antiquity by different nations, it may also be recognised as the more outstretched “Sea of Malayu/Melayu”, a term dating back to Arabic sources of the eleventh century and described as a voyaging corridor of people(s) after whom such maritime space was named (Andaya and Andaya Reference Andaya, Andaya, Jones and Marion2014). The second is the sociological construct of inequality, especially ascriptive inequality explained as a result of how social group distinctions are generated, maintained, and legitimated, vis-à-vis problems of verification (Reskin Reference Reskin2003: 3–4). It may be shown that while motives are varied and unobservable, visible processes for creating Malayness have had their own self-serving geopolitical and spatial rationales. This is consistent with early theorising on stratification in social systems, which has shown that there is no complex society that is “classless”, and that prestige and duties are distributed by the government, which sets and enforces norms, and defines a people in contradistinction to other polities (Davis and Moore Reference Davis and Moore1945: 242, 246). In relation to both concepts, it shall be examined how the hybridisation or creation of a regional third space serves to counter assertions of homogeneity and inequality, or at least the perception of being a class apart. If the Philippines were to be considered as lying in a Malay region, then it could become a space for challenging positionalities and actions to erect inflexible borders and purist notions of racial identity.

Shifting Ideas of Race vis-à-vis Colonial Territoriality and Malay Traces in the Philippines

The notion of race has had numerous definitions since it began to be used in the fifteenth century by Europeans in their drive to explore then-unknown lands and to subjugate the latter's inhabitants. As a stand-alone concept, race is distinguished by its assignment of a person to a given social group based on a mix of physical characteristics (Dein Reference Dein2006: 68). Its historic assumption of the biological basis of difference has long been shown to be untenable, so that it remains rather as a social construct employed in times past as the basis for determining superiority of one group over another, or what is called an essentialist reading (Morning Reference Morning2009; Kottak Reference Kottak2007; Dein Reference Dein2006). Although the latter understanding has long been dismissed from serious academic theorising, the social construction of race has continued to influence social actors and the study of their actions. In other cases related to race, early conceptions of pluralism drew on ideas of stable integration of ethnic groups rather than political consensus (Burawoy Reference Burawoy1974: 521–522). Later, there were attempts to disengage or recast racial essentialism that were fraught with built-in bias, considering that leading academics were from developed, majority-white countries, and it was not until the 1980s that social class became a more common explanation for race-associated behaviours (Takeuchi and Gage Reference Takeuchi and Gage2003: 439–440). As Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva1999: 899–900) explained, while race is not an essential social category, it has proven to be highly malleable and is still a principle of organisation, albeit one adapted by socio-political agents to their contextual intentions. In relation to this study, the core issue is that racial categorisation and location have continued to prove inadequate and open to challenge from both inside and outside the Malay region.

More recent work since the 2000s on the idea of “Malayness”, not necessarily with all the trappings or baggage of racial rhetoric ab initio, has shown that being Malay has been, until the early twentieth century, largely a fluid concept, admitting of more nuances and homelands than in past political and academic discourse, but oft omitting the Philippines as part of the region of study. One may take as an example the works contained in Contesting Malayness (Reference Andaya and Barnard2018 [2004]) edited by Timothy Barnard, not one of which treats of a possible Philippine angle to the otherwise multifaceted debate on Malay identity and its physical origins, as decried by Curaming (Reference Curaming, Mohamad and Aljunied2011: 242). This was despite the writings’ being otherwise refreshingly critical of narrow formulations in identity appropriation; for example in the way Vickers (Chapter 2) pointed out that there is no centre of the Malay apart from the role provided by policies, practices, and sciences of the Portuguese, Dutch, and British, such that it becomes impossible to separate a “true” Malay identity from colonial labels (Vickers Reference Vickers and Barnard2018: 53–54). Noticeably however, he may have added the Spaniards too, which would have directed his readers’ curiosity to the Philippines. In a similar vein, Anthony Reid (Reference Reid2001) narrated the definitional permutations of Malayness in detail, first in terms of descriptive and later, prescriptive categories used by colonial authorities and postcolonial governments. However, he left out Filipino constructions of the term. Mentioning a progression of locations, but again leaving out even parts of the Philippines likely to have been frequented by Malay-speaking mariners, Andaya (Reference Andaya and Barnard2004: 58–59) traced the linguistic origins of Malay identity from west Borneo through its gradual socio-political recruitment in networks of seafaring communities, its incorporation into their ways of doing and living, thence into the Melayu identity of the Srivijaya polity, and its culmination as an integrating identity and language of trade and literature in fifteenth century Melaka. There, it was henceforth recognized by the first-comer Portuguese, and later by other Europeans as a demonym, toponym, and a regional lingua franca—though not necessarily in that order. In the same anthology by Barnard, but also in his own book Leaves of the Same Tree (Reference Andaya2008: 49), Leonard Andaya explained how Malayu/Melayu as a political entity and as a place emerged to supplant the Srivijayan polity, citing the epic poem Desawarnana (also known as Nagara-Kertagama) from the Majapahit court, written in around 1365, which showed the actual conceptualisation of Melayu as associated with Sumatra. Yet, Andaya somehow indirectly exhibited a connection to the Philippines when he mentioned that the most distant evidence of Srivijayan influence was the inscription in Old Malay on a copper plate dating back to 900 AD found in Laguna in Bulakan province (sic), or more precisely, found in the river of Lumban municipality, in Laguna province—although the places inscribed on the copper plate itself refer to locations in nearby Bulacan province, which lies even farther north of Laguna (Postma Reference Postma1992: 185, 195, latter italics by this author; N.B. about 50 kilometres northwest). Such analyses can be used to assert at least two widely-accepted notions about the people who were Malays either as named by non-Malays, or by self-ascription: (1) that their social and linguistic spheres of influence were vast, reaching as far as Luzon in the Philippines, and (2) that their geospatial centre has shifted and even multiplied throughout the centuries, moving from insular to peninsular Southeast Asia, where it was thereafter pinned by colonial assertions and postcolonial manoeuvring, even if its cultural influence has remained in peripheral areas as far west as South Africa (Mandivenga Reference Mandivenga2000: 347–348) and as far east as the Moluccas (Maluku) where a sultanate at Tidore extended influence even farther to the coast of New Guinea (Warnk Reference Warnk2010: 112). As more scholarship comes to the fore, it is not unlikely that other locations influenced by Malayness may emerge, because of the seafaring characteristics of those who historically either called themselves Malay or were labelled by others with that name.

Locations of Malayness and its Colonial Appropriation

At present, the most reputable dictionaries of the EnglishFootnote 3—and upon random search by the author, other European languages, define the term “Malay” as either (1) an inhabitant of Malaysia, Indonesia, or Brunei, or of the Malay peninsula, and adjacent islands of Southeast Asia, as well as (2) the language of such a person as shared with others akin to himself. Thus, the geographical understanding of the word Malay has come to be circumscribed by the boundaries of the countries that used to be British or Dutch colonies, situated roughly between latitudes 10o north of the equator and 10o south of the equator, extending from Sumatra to Papua.

By virtue of size and precedent in modern times, the contemporary nation-state that lays most apparent nominal claim to being the socio-political centre of Malay identity is Malaysia. The Malaysian Federal Government, since its succession of the Transitional Federation of Malaya (1948) and Declaration of Independence dated 31 August 1957, and especially after the 1969 racial riots where there was pressure to support the ketuanan Melayu (Bass Reference Bass1970: 152), has undertaken a program to legislate and propagate, territorially, an unambiguous Malay identity for its originally disparate peoples, along with corresponding patriotic rhetoric on duties and obligations of citizens. To this end, Malaysian nationalists and their critics often quote the Malaysian constitution as the bedrock of their assertiveness, in particular, Article 160:

“Malay means a person who professes the religion of Islam, habitually speaks the Malay language, conforms to Malay custom and—

(a) was before Merdeka Day born in the Federation or in Singapore or born of parents one of whom was born in the Federation or in Singapore, or is on that day domiciled in the Federation or in Singapore; or

(b) is the issue of such a person.”

By this definition, in addition to some birth and residence requirements, a minority of Christian, Buddhist, and tribal/animist Malaysian citizens were excluded from the category, as well as other inhabitants, who may not have matched the socially-constructed designation at the time of independence. However, the designated “non-Malay” inhabitants of Malaysia at the time were given a chance to register and be accepted as citizens from 1957 through 1970, a fact that continues to be contested in recent times by Islamic groups that tend towards a narrower reading of citizenship as being coincident to Malayness (Palansamy Reference Palansamy2017: 1). Such imposition departed from loosely-applied colonial designations, even while consciousness of nationhood did not percolate immediately to the grassroots, where individuals continued to identify with their own ethnic groups or handily used more than one group affiliation depending on whichever a given social situation required.

For perspective, as recently as in 1958, just after Malaysian independence from British rule, a Filipino scholar traveling through insular Malaysia noted that natives referred to their own nationalities as “Iban, Dusun, or Bisayan…among others; moreover, Malay was not used in a racial sense, as it was then, until now being used, in the Philippines, but more in a religious sense, as being identical with being an adherent of Islam, although the rest of the people were keenly aware of their cultural diversity despite being of the same race” (Bernad Reference Bernad1971: 574–575). The same author contrasted this with his visit to contemporaneous Singapore, which, after separating from Malaysia in August 1965 and being populated by a majority of ethnic Chinese, had, in five years, so reinforced a national identity that citizens were observed to self-identify as “Singaporeans”. This had taken place in a regional space that had once been comprehended, and thereafter been designated by its western colonists, as a motherland of the Malays.

However, such a primeval Malayan homeland was never discovered as a spontaneous unitary polity by outsiders visiting the region. Like most nation-states in present day Southeast Asia, and to a lesser extent Thailand, which remained uncolonised but was territorially hemmed-in and influenced by European powers, Malaysia's predecessor, British Malaya, was a colonial construct assembled and delineated with strategic politico-cultural intent, as when the erstwhile governor Stamford Raffles commissioned his friend, the scholar John Leyden, to rewrite the translation of the major Malay text Sejarah Melayu, as the “Malay Annals”. This document was first composed in Malacca around 1436 (Wolters Reference Wolters1970: 154–70) and referred to the originator “kings of Rum” who came to the east (Braginsky Reference Braginsky2013: 373); it recasts what was previously a genealogy of rulers into an embellished 1821 publication in which the Malays were elevated from nation to race (Reid Reference Reid2001: 202; Shamsul Reference Shamsul2001: 363). Before this, Raffles had begun to develop his idea of Malayness in writing. For example, in the journal Asiatic Researches of 1816, Raffles wrote thus:

I cannot but consider the Malayu nation as one people, speaking one language, though spread over so wide a space, preserving their character and customs, in all the maritime states lying between the Sulu Seas and the Southern Oceans. (1816: 103 in Shamsul Reference Shamsul2001: 363)

After the establishment of the Straits Settlements in 1824, Raffles’ concept of “Malay nation” gradually became “Malay race”, an identity that was accepted by both the colonial power and in due time, by the Malays themselves (Shamsul Reference Shamsul2001: 363). More recent scholarship has been less timid about criticising Raffles’ revisionism and perhaps, deliberate glossing over of cultural differences to resonate with political and administrative ideals. An example is Aljunied's (Reference Aljunied2005: 5) assertion that Raffles was likely still unsure whether there was any difference between the two religions (Buddhism and Hinduism) as practiced by some of the Malays, although both were seen as promoting a social order in line with British interests, even if these were in decline in relation to the already widespread adherence to Islam.

In contrast, one may observe that unlike its neighbour, the Indonesian state apparatus has been known for a looser and therefore somewhat more inclusive, cultural rein over its peoples, presumably including those who self-identified as Malays, at least prior to state formation on 17 August 1945. Its motto, the Javanese “Bhinekka Tunggal Ika” (Unity in Diversity), belies any pretensions to pre-existing monoculturalism. Successive Indonesian governments have also been known to make effective use instead of symbolic physicality, especially through strategically placed monuments in Jakarta and other major cities in order to co-opt Hindu-Javanese iconography and the semantics of young heroism into nation-building and tourist projects (Evers Reference Evers2005: 1, 6; Nas and Boender Reference Nas and Wellmoet2002: 262–263), rather than use a “Malay” mould.

As a form of counter-discourse versus narrowly-defined locations of Malayness, more recent scholarship since the 1990s has carved a niche for those who wish to push or relocate the boundaries of the “Malay”, or unearth older conceptions that have been buried under constraints of postcolonial noetic territoriality. To begin with, one must recall how the cultural womb of the Malay language itself, supposedly in the vicinity of the Riau archipelago of present-day Indonesia, has itself been undergoing a flux. These islands, which were rich in natural gas, used to be a strong basis of Malay power, but because of western intervention, their sultans were either deposed or killed in the nineteenth century, and they are presently undergoing a socioeconomic takeover by mainland Indonesian interests (Al Azhar Reference Al1997: 767). Even as Riau Malays have seen their old identity as diffusing to newer centres of power or as borrowed instrumentality, the Malay world is being stretched in other ways. Research by Versteegh (Reference Versteegh2015: 285) and Mandivenga (Reference Mandivenga2000: 347–348) argued in favour of a Malay foothold in South Africa by “Cape Muslims”, and more convincingly, archival evidence discussed by Ricci (Reference Ricci2013) located a historical Malay community in Sri Lanka, which, in the 1860s could claim to have published the first Malay newspaper. In keeping with the geographically-expansive tempo of such studies, there is now opportunity to ask if there were other centres of cultural resurgence and contestation, such as those embodied for example, by even relatively powerless cliques like Filipino ilustrados who were already pushing a vibrant discourse on Malayness as the colonial era fell into decline (Mojares Reference Mojares2013: 108–109; Curaming Reference Curaming2017: 331–332). This article has been written in keeping with that small but well-researched groundswell of scholarship that allows such other voices to dialogue with the present generation of specialists.

While the Malay identity of the Philippines is worn lightly by most Filipinos and may not seem self-evident nowadays except to scholars and statesmen who see its instrumental value as a theoretical gadfly and a politico-diplomatic rallying point, respectively, and despite the earlier foregoing circumscription of Malayness by latter-day European colonists, there are two unassailable facts by which the Philippines manages to get its foot in the door, as it were, in the Malay world. First, there has always been a recorded lineage, or tarsila, between the Muslim Filipinos in the southwest region of Mindanao island and Malay aristocracy. This refers to the bloodline of Shariff Mohammad Kabungsuan, who was supposedly the youngest among the progeny of Shariff Ali Zein Ul-Abidin, a noble of Johor and married to a daughter of Iskandar Zulkarnain, mythic first Sultan of Melaka. Kabungsuan arrived in around 1515 as an Islamic missionary in Mindanao, possibly pushed by the dispersion caused by the Portuguese capture of Melaka in 1511 (Majul Reference Majul2009 [1973]: 23; Francia Reference Francia2010: 35). In a similar fashion, and of even older lineage, is the Muslim heritage in Sulu, starting with the sultanate's founding in the mid-1400s by Sharif Ul Hashim Syed Abu Bakr, also purportedly from Johor or Melaka (Tremml-Werner Reference Tremml-Werner2015: 95; Majul Reference Majul2009 [1973]: 6). Modern-day territorial claims of the Sulu clans upon parts of North Borneo, where they have kindred, provide the basis for the stance of the independent Philippine Republic—but these latter are still unsettled and touchy issues, meant for coverage in another article.

The second relationship, just as durable, albeit bare of claims to pedigree, is the persistence of sea-faring people who have maintained kinship and Malay-like language across national borders. The Sama-Bajau and various subgroups of the Orang Laut and Samal peoples are scattered across the littorals and islands of Malaysia, Indonesia, and the southern Philippines, and arguably represent the original mobile manifestation of the Malay race. In a sense, they have always inhabited undefined space between latecomer nation-states and have negotiated such spaces through their command of language and interregional people-skills. It is to this agency of regional communication, therefore, that this article now turns, to advance the argument for a wider pan-Malay sphere.

On Malay Language and Culture(s): A Prior Lingua Franca

Long before national boundaries were constituted, the Malay language, its cognates, and its Austronesian antecedents from Formosa (after Bellwood Reference Bellwood1991; Blust Reference Blust1995) were spoken in varying degrees throughout maritime Southeast Asia, serving as the lingua franca of exchange between islands. This is tellingly revealed, yet often as a footnote to history, in the account of Enrique de Malacca or Enrique the Black, the Malay slave who accompanied Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the world for the Spanish crown, and who found that he could converse with some of the natives encountered in what would later become the Philippines (Pigafetta Reference Pigafetta1999 [c.1524]). Enrique, who fell afoul of his Spanish masters soon after Magellan's death at the hands of the Cebuano chieftain Lapu-lapu, has since been recast in the Malay world and romanticised in Malay-speaking media sources as “Panglima Awang”,Footnote 4 which, aside from promoting him to petty chieftain status (Malay: “panglima”, also used in the Sulu area of the Philippines), tends to de-emphasise, or even obscures the fact that he was fluent in a tongue of that archipelago, or at least in a form of Malay speech belonging to a space of antiquity shared by commanderies of the Visayan islands where the Spaniards first made their Philippine landfall.

By the time the English-speaking colonists had established a presence in Southeast Asia in the 1800s, enough scholarly interest had developed in the cultures therein, which led to the pioneering Malay Studies of the eighteenth-century scholar William Marsden, who proposed Hindu influences on what he considered as an ancient Malayo-Polynesian language (Carroll Reference Carroll2011: 269–270). Another scholar whose seminal works shaped an anglophone understanding of a broader “Malay” language was John Crawfurd (Reference Crawfurd1848: 364) who held that shared vocabulary diffused progressively from west to east, including to the Philippines, with language being “immemorially the common medium of communication throughout all the islands.…”

Beyond explaining how the character of the language itself had also contributed to its own spread, as it had a simple structure, soft sound, and easy pronunciation (Crawfurd Reference Crawfurd1869: 125), he also described the physical typology of the region's people, unequivocally opening his discourse with the following words: “The Malayan race is the prevailing one in the Malay and Philippine Archipelagos [this author's emphasis], or from the 19th degree of north to the 10th degree of south latitude…” (Crawfurd Reference Crawfurd1869: 119).

Later scholars such as the Creole studies pioneer Hugo Schuchardt (1842–1927) laboured to show that the use of Malay as a sort of “Latin of the Pacific” was not so much due to corruption of some proto-Malay, but was rather the natural result of the sub- and super-stratification of mingling speech over time (Matauschek Reference Matauschek2014: 251). What emerges thus is a realisation that language itself was constitutive of a communal space, with words shared between Bahasa variants and languages of the Philippine archipelago.Footnote 5 Digging deeper then, one might well ask where the original geographical locus or the multiple shared loci of this sphere were—before it was named and bordered by competing socio-political hegemons.

Stepping Backward Farther: Pre-colonial Provenance of “Malay”

While it is not necessary to repeat here at length what has already been elaborated by historian Anthony Reid (Reference Reid2010), a few details are worth recalling about the oldest known geographic provenance of Melayu/Malayu, to emphasise the antiquity of the term as stemming from a particular site, albeit one larger than the present Malaysia. Scholars generally agree with the hypothesis that “Melayu Kulon” (Javanese: “West Melayu”) in the account of C. Ptolemy of second-century Egypt was likely on the Golden Chersonese, which would either be south of present-day Myanmar, possibly on the Malay peninsula, or on Sumatra, with linguistic and logical interpretation favouring the latter (Wheatley Reference Wheatley1955: 64). It should be remembered that the Golden Chersonese itself was considered by Indian mariners as Suvarna-bhumi, or Suvarna-dvipa, the “golden land”, which was their destination in peninsular Southeast Asia (Majumdar Reference Majumdar1955: 6–7). More definitive are the seventh century Chinese records of the Buddhist monk Yijing, where “Malayu” is a kingdom north of Srivijaya, which some scholars located in Sumatra, while a later source dating back to 1730 used “Melayu” (wu-lai-yu) rather than “Jawa” to refer to the same broad cultural area (Reid Reference Reid2001: 297). Ergo, given the foregoing accounts, it is probable that ancient Asian polities had already begun to use a label for either the location(s) or the language and its speakers.

The Need for Other Voices: Why Malayness of the Filipino Seeks a Place in the Discourse

The author may properly transition to a discussion of fieldwork findings here with the theoretical contribution of R. Curaming, in order to situate this article as both its foil and its dégagement. That is, this study serves first to enliven debate by illuminating where the aspects of such Philippine claims may sustain critique. Second, this study avoids echoing only Curaming's arguments in favour of tacking from another angle, where the historical and the geospatial components combine to lodge the Filipino view at the clamorous periphery of Malay studies, though also partially complementing what has already been established by the aforementioned author. Curaming (Reference Curaming, Mohamad and Aljunied2011: 261–263) showed how the attempts made by different scholars to interpret aspects of Malayness have led to two strains of treatment. First, there are those who foreground the fragmentary and contingent nature of history's particularities, or who historicise, and lead readers to the conclusion that being Malay is not a fixed state, which he hopes will lead one to investigate why different individuals or groups at different times have considered the Philippines as a part of the Malay world. Second, there are scholars (and politicians) who are invariably forced to draw upon the same limited set of evidence from the past, hence also historicalising narratives, or producing a unifying inevitability, that when followed to the present, tends to lead to a preponderance of Malaysia, and to a lesser extent Brunei, Indonesia, and Singapore as the natural fruition of a Malay-centric unfolding of history. However, if one were to pay close attention to the fleeting mentions and graphics of the Philippines in the same texts reviewed by Curaming, one may realise that more can be asserted about the off-centre parts of the Malay world's mosaic. In such cases, separation and distancing in time and space become fertile ground for planting others’ viewpoints, and convergent historiography alone is as vulnerable as Curaming's lone voice decrying narrow Malay-centrism. Such spaces of mixed identity, even if impermanent, should come to be recognised because they represent a more realistic shading away of ethnicity rather than abrupt dichotomies of identity that are not empirically valid on the ground.

There are two points where Curaming's work thus far on the Filipino-as-Malay may expose an Achilles’ heel. First, in attempting to historicise identity by demonstrating how other scholars’ works can be read differently to admit a more far-reaching Malayness, it seems that he inadvertently sets in motion, or at least boosts the project of constructing a counter-hegemonic location for Malayness from a non-Straits-centric viewpoint. Going over the same literary terrain he cited, this author would like to point out the following, as important expositions in support of this project: (1) In Timothy Barnard's book Contesting Malayness (Reference Barnard2018 [2004]), James T. Collins (168–169, Chapter 9) reminded his readers of “the fact of Borneo”, declaring it in his opening sentence as the “geographic centre of the Malay world”, and proceeded to expound on the Malay/Dayak identity and language intermingling along three river tributaries in Kalimantan. Using his perspective, Borneo's centrality would place the Philippines on better footing, distance-wise, as a likely location of Malayness, in comparison to peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Heather Sutherland (102, Chapter 4 of Barnard Reference Sutherland and Barnard2018 [2004]) affirmed the same point when she described the donning of identity by Makassarese in dealing with the Dutch East India Company (VOC), in the following words:

Being Malay was to possess a cultural and social passport…. The combination of Malayness with more locally grounded identities offered the opportunity to capitalize upon these wider linkages, without abandoning more narrowly-focused solidarities.

The same strategy, it should be noted, has also been used by inhabitants of the Philippines in their rhetoric on Malayness, which makes one wonder why the negotiations of one group should be considered in a text on Malayness, and not that of another. Still on the first point reviewing Curaming's commentary, this author notes that Anthony Reid's book, which actually mentions the Philippines more than a couple of times, indirectly underscores a “deep ocean ‘Eastern Route’ linking the Philippines and eastern Indonesia with Fujian” (Reid Reference Reid2010: 85), whose fading away caused the elite of Brunei and Manila to reorient trade to Melaka and Siam. This would have placed the latter, also called “Luzons” by the Portuguese, within an earlier comprehension of the Malay sphere, which even then was an arena of mixed entities who were assimilated by Melaka, and thereafter became a source of “Malay” diasporas.

While Curaming's diligence in enumerating dates, locations, and authors is laudable, his approach, like that of authors whom he cites, is not essentially geographical or place-emphatic, and in this sense is open to support by this author and future scholars in its attempt to “provincialize” (Curaming Reference Curaming2017, borrowing from Chakrabarty [Reference Chakrabarty2000: 329]) notions of Malayness versus the dominant forms located in the former British and Dutch territories. Why is this unhighlighted counter-centre, or the expansion of the Malay geographical sphere important for scholarship? Because, among points to be analysed further down, it provides an additional setting and problematises the proper location of a Malay periphery in relation to the currently asserted centre. This author's research can be situated at this juncture, in its attempt to reinterpret the locations of Malayness or hybridised quasi-Malayness, semi-Malayness, and proto-Malayness as objects-in-space worthy of study because of their sheer prolificacy even in the sixteenth century. These form a more robust collective root belying current nation-state appropriations of Malayness and invalidating any sociopolitical claims or assumptions of narrowly determined ancestry, ex post facto, or for that matter, narrowly-determined domains of theorising.

Second, Curaming may be chided for not pushing his own advantage further, if his four posted works in Bahasa (standard Malay) and his employment in Brunei are any indication that he may be one of the few scholars who can better access and interpret material on the pre-colonial and colonial connections of the Muslim polities of Sulu, Maguindanao, Brunei, and even Manila to other Malay urban centres. In light of this, he may yet be regarded as a keyholder of the Filipino-as-Malay discourse among living Southeast Asian scholars, provided that he and other like-minded scholars succeed in including the Philippines among candidates for scholarly exegesis. For example, he mentioned in his 2011 book chapter only Marahomsalic (Reference Marahomsalic2001) as a nod to the Muslim Malays of the Philippines, who may have been more convinced of their Malay rather than their Filipino identities in many cases. This may be deduced on the basis of their centuries-long inhabitation of that liminal region of western Mindanao, where some mixture of “Malayness” plays as active a role in emancipatory local politics as it does in say, the Muslim areas of isthmian Thailand. It would seem too that there were other, older writings accessible to Curaming, such as those of Ileto (Reference Ileto1971) and Majul (Reference Majul2009 [1973]) that could have been artfully combined with his own Malay-language sources to produce a fresh reinterpretation of Philippine linkages to the Malay world.

Given his Filipino background and training in Asian Studies, it would appear that Curaming's strongest suit has been the ability to leverage the panoply of accounts from recent history that touch upon manifestations of Malayness in the Filipino experience and worldview vis-à-vis his past and present readings of other scholars’ critical works on Southeast Asia. His corpus, as listed on Google Scholar and verified in databases (Scopus and Proquest) available to this author, consists of at least 48 works, of which at least 3 touch upon the Filipino-as-Malay theme (“Filipinos as Malay: Historicising…” 2011; “Rizal and the Rethinking of the Analytics of Malayness…” 2017; and “Official History Reconsidered: the Tadhana Project…” 2018). In such writings, he introduced a counter or parallel discourse to the theoretical delimitations of Malayness. As he (2011: 265) asserted: “Granting that Filipino Malayness is contrived and superficial, it remains crucial to the analytics of Malayness to account for a full range of forms which Malayness takes”.

This author must respond to this with a mirroring proposition: granting that Filipino Malayness is neither here nor there, it remains equally crucial to the analytics of Malayness to account for the full range of sites in which Malayness in a purebred or hybrid form was, and still is, manifested. It is to these locations that the reader now proceeds.

Findings

Iberian Initiation of Southeast Asia: “Malaio/ Malayo” is Named and Brought to Europe

The Malay world was located and drawn physically into the sphere of European colonisation by two competing Iberian monarchies: Portugal and Spain. In a bid to access the spices of India, to break through the trade monopolies of the pre-Italian city-states and to circumvent Muslim hold over the Middle East and Central Asia, those two powers sailed explorers into the unknown, finding America in the process, and after crossing the Pacific, carved parts of Southeast Asia into Lusitanian and Hispanic realms, beginning with the Portuguese capture of Malacca in 1511. It is around this time that malaio entered Portugal's lexicon. Although the first Portuguese observers acknowledged the cosmopolitan nature of Malacca (with chronicler Tomé Pires reporting 83 languages spoken in the city), Melayu/Melayo was not only acknowledged as the language of trade in Asia, but also as the native tongue of the Malaios of Malacca (Skott Reference Skott2014: 131). At this early stage, it would be safe to infer that there was no rigid usage of “race” as a differentiating concept, indeed no necessity for it, as European explorers needed only descriptive terms when they first probed afield.

There would have been no complications assigning identity later, if the Portuguese alone had ventured forth. But by 1521, the Spanish expedition of Ferdinand Magellan had found a way to Asia by sailing west from Europe and around South America, circumnavigating the world on its onward journey. By 1565, the Spaniards had arrived again to colonise the islands found along the way. Spain's presence in the Philippines was problematic, at least initially, to its erstwhile rival, Portugal, and later to other European challengers who were carving their socioeconomic spheres and ways of understanding Asia (Padron Reference Padron2009: 22), especially because Spain, more than other colonisers, pushed the proselytization of its subjects into Roman Catholicism and had more human resources to lead and conscript Filipino troops, missionary acolytes, and navigators in short-lived expeditions, just as its officials pursued the more banal activities of profiting from spices in the Moluccas and lucrative trade with China and Japan. On the face of it, therefore, it is unsurprising that there was communication between the Portuguese and Spanish empires. For one thing, there is the obvious matter of the “Union of the Crowns” effected between Spain and Portugal in 1580–1581, through which Philip II of Spain became the ruler of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, a state of affairs that continued under his successors Philip III and Philip IV until the “Restoration” of the House of Braganza in 1640. (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam2007: 1360). This implies that in the history of the Spanish conquest of the Philippines, knowledge and names for the peoples and places of Southeast Asia were exchanged between European mariners, who were not necessarily either Spanish or Portuguese. The use of the Spanish term Malayo to refer to the people that they conquered in and around the archipelago which would later become the Philippines would have been a pragmatic use of language, especially if borrowed from their nearby Portuguese co-subjects. It is possible to draw a midway conclusion at this point: the designation “Malaio”/ “Malayo”, equivalent to the English “Malay”, was used by western colonisers to describe the ancestors of Filipinos within the same century that it was being used by Iberians to label the precursors of the Malaysians and Indonesians, at least 200 years before the British Raj or the British East India Company ever established a homogenising presence and similar linguistic assertions about more specific locations in Southeast Asia.

In so far as human agency is a necessary factor of spreading ethno-geographic understanding, it must be mentioned that not only Spanish terms like Malayo travelled with the conquistadors, but also the colonial subjects themselves. They reached the far corners of the “Spanish Lake”, as the Pacific Ocean was regarded in the late 1500s (Schurz Reference Schurz1922: 181–182), for it is certain that Malayo troops were garrisoned in Spain's short-lived outpost in Formosa (Borao Reference Borao2007: 4–5, 9; Mawson Reference Mawson2016: 381–382), revolutionaries were exiled to the Marianas to live among Malay settlers (Joaquin Reference Joaquin2005: 144; Quimby Reference Quimby2011: 23), and a small community of Malay Filipinos, most likely including mariners of the galleon trade, resided in Mexico (Guzmán-Rivas Reference Guzmán-Rivas1960: 48–49; Carrillo Reference Carrillo2014: 83). There were no distinct “Filipinos” yet in the 16th and 17th centuries, as the natives only began assuming the former creole appellation for themselves at the cusp of their first bid for independence in the late nineteenth century. Hence, in all these aforementioned sites, the Malayos (derogatorily also called Indios) as Spanish subjects served functions and lived out roles analogous to the British-transplanted Malays in Sri Lanka and South Africa.

As for the transmission of the term “Malay” to English, along with all its connotations, there could have been any of several routes. The most logical, direct route would have been through communication occasioned by pre-existing relations between the English and Portuguese crowns that had begun in the 1380s when the Duke of Lancaster and King João I entered into an alliance to throw off Castilian expansionism. The Anglo-Portuguese treaty is still in existence, having been temporarily voided during the Union of Crowns (Palenzuela Reference Palenzuela2003: 10–11). For the purposes of the argument in this study, the link that had been formed with Portugal, however tenuous, could have provided English mariners and royalty with insider information on the disposition and naming of lands and peoples of the Orient. Nonetheless, by the 1600s, the English and Dutch East India companies had been established, and expeditions were sent to Southeast Asia, that would then provide first-hand knowledge. In due course of time, the interlopers found ways to ensconce themselves by engaging with pre-state societies in Southeast Asia. These petty chiefdoms were sometimes antagonistic and called on Europeans as arbiters to resolve disputes, a situation that the Dutch took advantage of by seizing the Moluccas and expanding Batavia (Hui Kian Reference Hui Kian2008: 293), and which the English followed, by entering into a treaty with the Sultanate of Sulu because both parties had interest in trade and the need to counter Spanish expansion southwards. This is corroborated by the evidence of Spanish archival records from the 1600s that begin to mention the presence of Malayos in Malasia, in connection with the comings and goings of Dutch corsairs (Consejo de Indias 1616: Informaciones sobre los corsarios holandeses; Consejo de Indias 1696: Aviso a Cruzat de noticias sobre reinos vecinos de Filipinas).

The term Malay, as originally applied to subjects of the Iberian crowns, thereafter came to be used by anglophone colonisers. One curiosity of translation, for example, from the time the Spanish and Portuguese forces still held sway in Southeast Asia, is a dictionary by Thomas Bowrey, who used the Iberian language term in his “Dictionary of English and Malayo, Malayo and English” (Reference Bowrey1701). It showed a map with Borneo as the geographic centre, and Mindanao and Palawan in the Philippines just as prominent as the Malay peninsula. As the Dutch, and later the British empires grew in strength, they coined or modified existing names for their subjects, further subcategorising the latter, as in the case of British Malaya, to suit administrative needs. For example, the word “race” as used by British enumerators first appears in their 1891 census, and as per the advice of the census author in 1901, it was mandated to replace “nationality” as a wider and more exhaustive expression; such that notably, in 1891, “Manilamen” (presumably Filipinos) were placed under the racial category of Malays (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1987: 561, 563).

Ascription of the Filipino as Malay during the Spanish Colonial Period, 1565–1898

At this juncture, the reader may begin to appreciate how the designation of Malay came to be owned by the inhabitants of the Philippines as well, for the Spanish rulers did use Malayo in a racial-descriptive sense, albeit without restrictive territorial connotations as may have been reinforced by latter-day colonial administrators. It is unnecessary to trace the lexical usage through Spain's 333-year reign. Thus, this author shall take periodic examples to show how the Malay designation evolved, while also incorporating nuances. The work of the government official—and notably non-friar, Dr Antonio De Morga, published around 1609 in Mexico, is enlightening, especially after its annotated redaction in 1890 by José Rizal, the foremost in the pantheon of Filipino heroes. In the Hispano-centric account of events, it appears that Malayo as a term was employed to describe both Filipino natives and similar-looking Asians, as when the Spaniards embroiled themselves in Cambodian court intrigues, and referred to the allies of a Khmer lord to be leading an army of Malays (De Morga through Rizal Reference De Morga1890 [1609]: 47).

It is around the nineteenth century that British borrowing is evidenced by the 1868 translation of Lord Henry E. J. Stanley of Alderley, from whom, in a reflexive turn, Rizal retranslated into his Spanish annotation of Morga the references of Stanley, for instance in the footnote (De Morga through Rizal Reference De Morga1890 [1609]: 49) on the word Laksamana, which in Tagalog (the root idiom of a language later to be called “Filipino”, for reasons of political inclusivity) means admiral, as it does too in Malay. These annotations have been confirmed in the book's preface by Austrian scholar Ferdinand Blumentritt, a professional correspondent of Rizal, who is often quoted or paraphrased by Filipino cultural institutions as having declared: “not only is Rizal the most famous man of his own people, but the greatest man the Malayan race has produced” (this author's emphasis; Romulo, in Sichrovsky Reference Romulo1983: 1). Here then, in addition, was a nineteenth-century Austrian understanding of Filipinos as a part of a larger racial category, which remains accepted (if uncritically) as part of the past nationalist literature in the Philippines.

Rizal himself, a relatively productive writer in comparison to his peers, in the year before had published his Sobre La Indolencia de los Filipinos (“On the Indolence of the Filipinos”), which he wrote as a defence against European criticism of his fellow countrymen. Notably, in drawing upon his own historical knowledge as a member of the ilustrados, or educated class, he referred to his compatriots as Malays. For instance:

Los malayos filipinos, antes de la llegada de los europeos, sostenían un activo comercio, no sólo entre sí, sino también con todos los países vecinos.

[Before the arrival of the Europeans, the Malayan filipinos sustained an active commerce, not only amongst themselves, but also with all the neighbouring countries.]

Indeed, Rizal and his fellow ilustrados could not have been referring to themselves alone as Malays when they founded a secret society in 1889 called Rd.L.M., a group reportedly committed to “the redemption of the Malays” (Redención de los Malayos), since his colleagues recalled that Rizal was then excited about Multatuli's anticolonial novel, Max Havelaar (1860) and talked about the misfortunes of the Javanese (Mojares Reference Mojares2013: 115, citing Rizal's correspondences in the 1800s). This was about the time that the same circle of friends founded Indios Bravos [“Brave Natives”] in Paris in 1889, a propaganda organisation that turned the derogatory Spanish appellation of Indio on its head, and had for its goals, inter alia, “…the liberation of the Malay peoples from colonial rule, a pledge to be made good first in the Philippines, later to be extended to the inhabitants of Borneo, Indonesia, and Malaya” (Coates Reference Coates1992 [1968]: 175, citing Rizal's correspondence in the 1800s). At the least, such actuations were in keeping with a gregarious Filipino state-of-mind, willing to see a shared suffering among adjacent colonised Southeast Asians, who could be co-classified as Malay, to borrow from the Spaniards’ erstwhile labelling.

Given the influence of Rizal, especially after he was executed by the Spaniards in 1896, and, as some argue (Kramer Reference Kramer2006: 334–335) because of his post-mortem recruitment by the colonising United States as a pacifist epitome of the Filipino citizen, his writings were taken up by generations of nationalists and activists for different purposes, integrating, it may be surmised, his notion of the Filipino as Malay in a broad racial sense. This understanding was uncoupled from an enforced comparison to the Iberian phenotype, therefore less entangled in any socioeconomic and political reservation, as may have been extant in the Dutch and British spheres.

The American Colonial Era: Persistent Malay Labels and Affinities in a Vaster Territory

Depending on how one appreciates it, the American colonisation of the Philippines either confounded or enriched the Filipinos’ own understanding and acceptance of themselves as Malay within a territory that was consolidated to form its present borders, following the annexation of the Sulu Sultanate, done from 1899 to around 1935 by gunboat diplomacy and actual island battles. The Americans deployed knowledge that was logically inherited both from their former British ancestors and learned from their own investigations of their new colony, as embodied by the 55-volume commissioned work undertaken by Emma Blair and James Alexander Robinson, “The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898”. This opus relied on primary European sources and picked up the Malay appellation of the Philippine natives, although by that time, the citizens had already begun to see themselves as being “Filipino”, and yet, “of the Malay race”.

More mundane but just as telling an example are the memoirs of Antonio Luna, the acerbic revolutionary general whose career spanned both major colonial eras in the Philippines, and who led armed resistance against both Spain and the United States. For example, in his Impresiones, Luna (Reference Luna1891: 3) wrote in self-reflection:

[My type, decidedly Malay, that had called attention in Barcelona, excited the curiosity of Madrid's residents in a notorious manner.]

Sometime between the 19th and 20th centuries, the five-race typology of naturalist-anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840) entered the Philippine sociological understanding. Based on the visual evidence of their physicality alone, most Filipinos would come to be categorised by others as “brown”. While it is no longer politically correct nor academically appropriate to employ this simplistic frame, the notion of belonging to the “brown race”—ergo, Malayan, has persisted in self-ascribed Filipino political and nationalist rhetoric; this, despite the paternalistic reference to Filipinos as the “Little Brown Brothers” of the Caucasian Americans (the white race), as first attributed to the erstwhile military governor of the colony and later president of the United States, W. H. Taft (Bernardo Reference Bernardo2014: 5).

At around the same time, Filipino nationalists such as Wenceslao Vinzons, who would later be executed in 1942 by the Japanese for his guerrilla activities, also cited their Melayu connection when, like the Spanish colonisers, Americans propagated a discourse on the primitive Filipino. As Reid (Reference Reid2010: 99) and Curaming (Reference Curaming, Mohamad and Aljunied2011: 251–252) narrated, Vinzons as a student leader in the University of the Philippines spearheaded the establishment of Perhempoenan Orang Malayoe, an organisation whose membership was drawn from interested Filipinos and foreign students in Manila who came from southern Siam, the Malay Peninsula, the Dutch East Indies, and Polynesia. Available accounts indicate that Malay served as a ceremonial language and that such activities helped support Vinzon's vision for the formation of what he would later call “Malaysia Irredenta”, or a restored pan-Malay polity, which hearkened back to a communistic, if imagined, geographic affiliation in antiquity. In addition, the organisation's avowed objectives included the study of history and culture of Malay civilisations and the promotion of solidarity among “brown people”. Again, one must notice how this echoed the young revolutionaries of Rizal's generation and how the colour trope resurfaced and was used unabashedly as an exhortation to solidarity among perceived kinsmen who occupied adjacent colonial spaces. As for the Filipinos themselves, who had been classified by Spanish colonizers as Malayo/Melayu, theirs was a Malay label long before the English and Dutch colonial powers named their own subjects and overseas territories. This is a fact worth insisting on and echoing in the scientific literature, because it demonstrates an apogee of Malayness even if such predecessor “Malayos” were relegated to the northeast periphery. Rather than reject the term, the United States’ colonial authorities allowed the mainstreaming of a blithely assumed “Malayness” by the governed. The Filipinos, in turn, anglicised what their intellectuals had already adopted from Iberian name-designators, whose ancestors had first come into a fluid region where traders were often Malayo/Malaio to one degree or another, irrespective of the nationality or creed that their descendants assumed as additional mantles in the centuries to come. As the process of translation began, it was yet subverted by such local cultural insurgency as Rafael (Reference Rafael2016: 55) pointed out: “Filipinised English consisted of dressing English in the clothes of Malay sound patterns”.

Consistent with the fin-de-siecle zeitgeist, a tempo of pan-Malay nationalism developed in a wider cultural space which showed how shifting understandings were employed or altered to suit political ends. The idea of Melayu Raya or a greater Malay identity was concurrent with the writings of Indonesian leftists and journalists such as Mas Marco, Tirto Adi Soerjo, and Tan Malaka who envisaged a pan-Malay region consisting of the Philippines, Malaya, and Indonesia whose people spoke Malay languages (Villareal Reference Villareal2013: 287). By the time World War II broke out in the region, and when the first stirrings of independence were happening in the Dutch East Indies and Malaya, it could thus have been said that key figures in the respective colonial societies had also begun to experiment with concepts of a shared ethno-regionalism.

From Sultanates to Bangsa Moro: The Fact of Muslim Polities in the Philippine Archipelago

Aside from the lineage tracing the clans of Sulu and Maguindanao to Melaka or Johor, it must be remembered that when the Spanish conquest commenced in 1565, precolonial Manila itself was a Rajahnate, ruled by Rajah Sulayman, who had blood ties to the Bruneian ruling class (Aguilar Reference Aguilar1987: 155–156). Apart from being nominally Muslim, he and the residents of his polity would then have qualified for the kerajaan of Malayness listed by anglophone scholars (Kahn Reference Kahn2006: 35–36; Milner: 243–244 in Barnard Reference Barnard2018 [2004]). Yet even after Manila was taken by the Spaniards and rapidly Christianized, Muslim polities persisted in Mindanao, carrying on trade with their kindred in Southeast Asia. At this point, the problematization of James Francis Warren of the Sulu Sultanate vis-à-vis Chinese imperial lockdowns and British expansionism becomes instructive. Resonating well with the geographic viewpoint of this study, Warren's writings characterise Sulu as a “Zone”, not just in the spatial sense, but as a meeting ground and arena of potential antagonisms that transformed the Tausug society of what he calls a “Malayo-Muslim” state with Bornean dependencies, which came to be part of the world system of commerce that prevailed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Warren Reference Warren1997: 182, 196). Sustained by a trade in slaves, spices and firearms, the dominant sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu, in turns, became adept at playing off European—and later American interests against one another, to ensure their political and economic survival, as Majul (Reference Majul and ar Adib1966: 313) described, citing such details as the exploratory talks in 1840 between the British Consul General at Borneo James Brooke and the Sultan of Sulu; French offers to purchase Basilan Island from its sultan around 1844–1845; and Muslim representation in the Philippine Commonwealth government following Sultan Kiram's abdication in 1915. As Majul convincingly explained, the development of Islam in the southern Philippines should be seen as the logical geographic extension of dar-ul-Islam spreading from what would later become Malaysia (Reference Majul and ar Adib1966: 307–308). If that were so, then it should be plausible to investigate the likelihood that past and even present understandings of Malayness be extended to Mindanao, carried along with Islam, notwithstanding the subsequent creation of modern nation-state borders. This is likely, since after consolidating the present Philippine territory, Americans kept their Christian and Muslim subjects apart early in the colonial period, to live according to their own cultural logics (Vartavarian Reference Vartavarian2018: 144). Interestingly, the latest, and now most politically-sophisticated manifestation of the Philippine Muslim-Malay identity has been the passage of the Bangsamoro Basic Law by the Philippine Senate in May 2018, granting autonomous power to Muslim-majority provinces, and notably recruiting the identity label from the Malay word for race/nation: “bangsa” combined with the Spanish label for Muslim/Moor: “moro”. Given the historic operation of such subaltern agency within Philippine borders, which are consubstantial with the negotiations of Malay (and non-Malay) principalities in the British and Dutch spheres, how then, can present-day critics or geopolitical purists continue to deny an expanded discussion of Malay connections that are properly located within the Philippine experience and territorial borders of the Filipino nation-state?

Post-Colonial Geopolitical Cleavages, Malayness Elsewhere, and in Public Education

Back in the Philippines, which by 1946 had become independent again (after a fleeting emancipation in 1898), the impetus towards forming what could otherwise have been a hybrid Malay regional space took on a more hegemonic complexion, especially as Malaysia and Indonesia, and later Singapore, were still embroiled in emancipatory struggle. By July 1962, then President Diosdado Macapagal, who in his youth was a contemporary of the late Vinzons, called for the formation of a Confederation of Greater Malaya, “to supersede the British-proposed Federation of Malaysia”. The Confederation would include the Philippines, Malaya, Singapore, and the three Borneo territories and, at some later stage, it could be opened to Indonesia as well. It would thereafter be referred to as MAPHILINDO (Malaysia-Philippines-Indonesia). Emphasis was placed on the merits of an “Asian project” as distinct from a European one (Vellut Reference Vellut1964: 33). The diplomatic entreaty, however, was not entirely altruistic, as the heirs of the Sulu Sultanate had requested the Philippine Government to intervene in the British moves to bring into being the Federation of Malaya against objections that a portion of Sabah should have been repatriated to the aristocracy of Sulu. It is from this point onwards that a divergence was cultivated between the “Malays” of Malaysia and the Philippines, as they were drawn apart geopolitically into the formation of their respective nation-states, following a rebuff of Philippine overtures to form a more encompassing regional entity. Had MAPHILINDO been accepted, then it could have been, according to the frame of this research, constitutive of a supra-national third space that is permissive of cultural blending apart from narrow nationalist identity-formation.

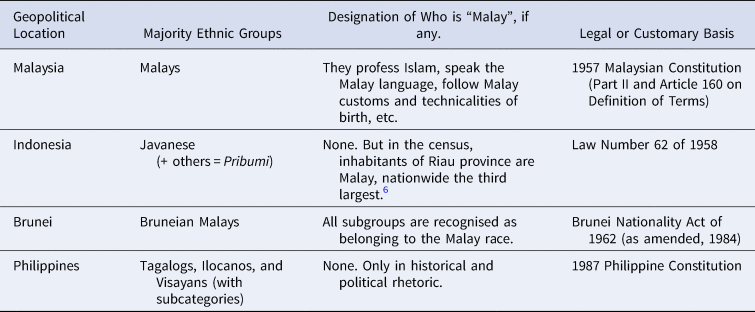

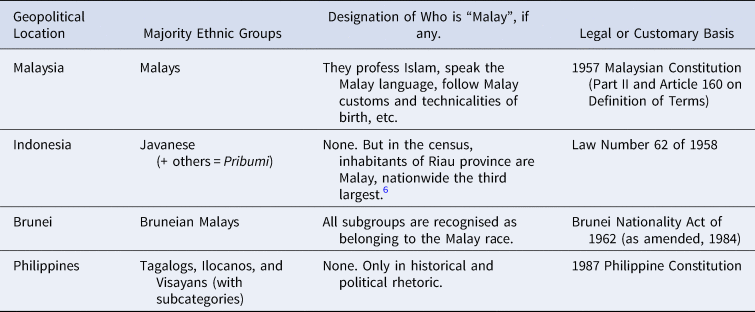

As seen in Table I, a cross-cutting “Malayness” is no longer as commonplace as it was in the past. It has been reduced to a mere ethnic group census designation in Indonesia, and a rhetorical, historic vestige of pan-regionalism in the Philippines. The designation “Malay” remains a major ethno-linguistic category in Singapore, and an all-encompassing supra-categorisation in Brunei and Malaysia. Malaysia's appropriations do not, however, cause the preceding discussion on the Philippine usage to become irrelevant, but rather highlight that social construction of Malay identity has changed across time and space. At the same time, as Filipino historian Zeus Salazar pointed out, the Filipinos began to be cut-off from the Malay world in the 1660s, with the widening and deepening of Hispanization, albeit leaving out frontier areas like Mindanao and Palawan, which thereafter have kept a tenacious cultural and geographical linkage to the Dunia Melayu (Salazar Reference Salazar1998: 89–91).

Table I. Locations and Definitions of “Malay” in Southeast Asian Polities

Despite the gradual severance from older manifestations and processes in the Dunia Melayu, Philippine education retained a geographic understanding of shared Malayness, starting, for instance, in Spanish secondary school lessons that taught that the Philippines was part of the somewhat fluid Malasia (one of four divisions of Oceania, together with Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia), and that Filipinos were part of the “Malay” race (Mojares Reference Mojares2013: 108). Resil Mojares (Reference Mojares2013) went on to describe how such tutelage led, by the nineteenth century, to an expanded sense of being Malay and spurred the first Filipinos to apply themselves to the study of the Southeast Asian region by the 1880s, the most prominent of them being José Rizal (1861–1896), Pedro Paterno (1858–1911), Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera (1857–1925), and Isabelo de los Reyes (1864–1938). Subsequently, Filipinos have continued to use the term Malay in self-ascription, adhering more to its descriptive sense, with the greatest impact achieved through the public education system that had started out as a legacy of American colonial rule. Teodoro A. Agoncillo (1912–1985) who wrote History of the Filipino People (1st edition c. 1960, to 8th edition 1990), unequivocally instructed: “…The Filipino belongs to a mixture of races, although basically he is Malay” (Agoncillo Reference Agoncillo1990: 4), as did Gregorio F. Zaide (1907–1988), who wrote Philippine History and Government (Zaide, 1st edition c. 1974 to 6th edition Reference Zaide2004). One eminent Filipino historian, O.D. Corpuz (1926–2013) also did not hesitate to refer obliquely to the Malay origins of the Filipinos in his Roots of the Filipino Nation (1st edition circa 1989, 2nd edition 2005), when he remarked about the mixing of native and foreign bloodlines: “…This racial infusion produced a Filipino nation that was multiracial rather than a purely Malay people.…” (Corpuz Reference Corpuz2005: xvi). The writings of these three scholars alone, along with other imitators, have been drilled into at least four generations of Filipino students, starting every decade since the 1970s, and have thus favoured the more expansive and inclusive understanding of a pan-regional Malayness as a refrain utilised in popular discourse that sees no inherent ideational or practical conflict between being wholly Filipino, and also being categorically Malay, in the racial or linguistic senses. As Curaming himself (2017: 417, 445) concluded, there was no strong hegemonic attempt to “standardize” such history textbooks, or at least there was no effective one that suggested that the lingering of a Philippine “Malayness” was less contrived and rather spontaneously diffused and accepted.

More accurately, it would seem that people who were lumped together previously with Malays by the Europeans, like the Khmer, Lao, or Kinh, have each gained their own names and geographic homelands in Philippine history books, while the Malay realm continues to be roughly coterminous with insular Southeast Asia. None of the Constitutions of the Philippines has mentioned “Malay” in the proprietary racial or parastatal sense. Nevertheless, this does not imply a permanent casting-off. Quite to the contrary, the recurring use of the term in popular and academic discourse can neither be denied nor ignored: it persists as a historical keepsake, a cultural refrain. For these reasons, it is discussed herein in scholarly exegesis in order to articulate its tangential nature, and its counter-centric geographical nature, and in this sense is perhaps like that stubborn notion of race, shorn of biological pretentions, but potent as a sociolinguistic bellwether.