INTRODUCTION

The boundary-stone studied here, a well-known inscription from Karnari (Archanes, Crete), provides the best evidence of the so-called ‘Lands of Capua’ on Crete. Attention has thus far focussed upon it as evidence for an Italian colony possessing land on the island. However, the reading of its text proposed here makes it possible to resolve the question about the designation of the procurator in charge of the arbitration to which it refers. This enables us to revisit the wider juridical process and compare it with information provided by Roman land surveyors. It also sheds new light on the juridical category of the ‘Lands of Capua’ (praefectura Campana) on Crete and the fiscal situation, administration and management of these Cretan lands that belonged to Capua. The Roman prefecture system provided a way of administering communal land leased in exchange for rent (ager vectigalis). This article is divided into two parts: the first concerns the Karnari boundary stone and its relationship with the ‘Lands of Capua’; the second concerns the judicial process surrounding this boundary dispute.

THE ‘LANDS OF CAPUA’ ON CRETE AND THE KARNARI INSCRIPTION

The pre-Augustan and Augustan context for the relationship between Campania and Crete

The Karnari inscription dates to the era of Domitian. That was the time of the final resolution of a long-term problem that began with Augustus’ assignation of land on Crete to Capua. Indeed, the special situation of the ‘Lands of Capua’ on Crete began with Augustus, and it is worth looking first at the links between Campania and Crete and the reasons behind his decision to give these lands.

The relationship between the region of Campania in Italy and the Greek islands of the Aegean Sea is well known (Fig. 1). Capua was one of the most important towns in Campania, and there is a significant body of evidence regarding the Campanians’ enormous commercial interests in Greece from at least the second century bce. For instance, numerous inscriptions reveal the permanent residency of Campanians on Delos, as evidenced by the presence of religious organisations known as collegia (Diaz Ariño Reference Díaz Ariño2004, 464) devoted to Apollo, Hermes, Poseidon or the lares compitales, as well as trade associations of olive oil and wine merchants (cf. Salviat Reference Salviat1963; Flambard Reference Flambard, Coarelli and Musti1982; Díaz Ariño Reference Díaz Ariño2004). Onomastics reveal the Italian and specifically Campanian origins of the magistrates of these organisations (D'Isanto Reference D'Isanto1993, 20). In addition, a conlegium (!) mercatorum (traders’ association) linked to long-distance trade (Salviat Reference Salviat1963; Flambard Reference Flambard, Coarelli and Musti1982; Díaz Ariño Reference Díaz Ariño2004, 453, n. 48) appears to have been related to commercial expeditions to Delos.Footnote 1

Fig. 1. Map of Capua and Knossos (author).

Following the fall of Delos in 88 bce, Italian business people settled on Crete, and specifically Gortyn. They did not form a large community, but some of them had permanent residence there.Footnote 2 These permanent Italian residents maintained their bonds with Italy though trade, fulfilling a Cretan demand for Italian goods (Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky and Chaniotis1999; Reference Baldwin Bowsky2002a; Reference Baldwin Bowsky2006). At this time, Roman campaigns between 69 and 67 bce concluded with the conquest of the island and the settlement of Metellus in 66 bce.Footnote 3

It is difficult to determine whether the Roman colony at Knossos was founded by Caesar or Augustus: scholarly opinion in this respect is divided. Biundo (Reference Biundo2003, 135; Reference Biundo2004, 402; also Perl Reference Perl1970, 342, and Pautasso Reference Pautasso1994–5) suggests that it was founded in Caesar's time and that the confiscation was made from its divided and allocated land (called subseciva). There is, however, no evidence for a Caesarean foundation. Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre2013, 262 and n. 149; Rigsby Reference Rigsby1976, 329) also believes in an Augustan foundation, suggesting that the colony was founded by Augustus after the battle of Actium in 31 bce.Footnote 4 It would not have been possible to found the colony earlier, as this part of the Empire was controlled by Mark Antony, and Knossos and other parts of Crete had openly pro-Antonine sympathies. Thus, the foundation was probably carried out after the recovery of the island from the influence of Cleopatra, but before 27 bce, when Octavian became Augustus. The appointment of Marcus Nonius Balbus as governor of Crete,Footnote 5 the appearance of the first colonial coins after Actium, the (theoretical) date of the assignation of the Capuan lands and the evident change in the epigraphy of the Augustan context point to it being an Augustan colony associated with the political reorganisation of the rest of this province.Footnote 6

In the Augustan period, the relationship between Campania and Crete became stronger. Velleius Paterculus (2.81.2) and Cassius Dio (49.14.5) explain that after the battle of Philippi in 42 bce, in which Octavian and Mark Antony fought against Brutus and Cassius, Octavian settled his veterans in Italy. He ordered some public lands in Capua to be confiscated in return for the gift of an aqueduct (Aqua Iulia) and declared that Capua would possess new public lands on the island of Crete. Dio tells us that these lands were at Knossos. They are normally referred to as the ‘Lands of Capua’ on Crete. It is hard to believe that Octavian would have been able to assign any lands on an island that was under Mark Antony's control up until the time of the battle of Actium in 31 bce.Footnote 7 Accordingly, the assignation of these lands must also be placed only after Actium.Footnote 8

It is difficult to pinpoint the beginning of the relationship between Capua and Crete but the proxeny inscriptions at Gortyn (ICr IV 216; cf. Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky2006, 386) suggest an earlier interest. However, the epigraphic repertoire of Italians on Crete prior to Octavian is not as explicit and revealing as that for Delos and has its origins only at Gortyn, not Knossos.Footnote 9 There is no definite evidence of Roman names at Knossos before the Augustan period (cf. Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky and Dabrowa2001). From the time of Augustus onward, the evidence of Italian onomastics dates to just before, or the time of, the foundation of the colony of Knossos.Footnote 10 These immigrants probably came from the south of the Italian peninsula, a region where Greek was still commonly used in daily life and where there were important wine traders (Marangou-Lerat Reference Marangou-Lerat1995, 13–18; Reference Marangou-Lerat and Chaniotis1999). Similarly, there is plenty of evidence of Greek wine in Italy and specifically in Campania from the first century ce.Footnote 11 However, Campanian ceramics were very popular imports at a lot of sites around the Aegean at this time, and therefore their presence does not necessarily indicate a special connection or a permanent Italian community living there. It does, however, indicate close trading links and strong interregional network connections.

The island of Crete underwent territorial reorganisation at some point between the mid-first century bce and the mid-first century ce (Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky and Dabrowa2001; Reference Baldwin Bowsky and Dabrowa2002b; Papaioannou Reference Papaioannou and Westgate2007; Hayden Reference Hayden, Livadiotti and Simiakaki2004; Hingley Reference Hingley2005, 10–15; Sweetman Reference Sweetman, Glowacki and Vogeikoff-Brogan2011; Reference Sweetman2013; Gallimore Reference Gallimore2019, 611–12). However, during the Augustan period we can identify several specific and important political and administrative decisions: as we have seen already, it may be at this time that the colony of Knossos was founded, the ‘Lands of Capua’ were assigned and Gortyn became the provincial capital (Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky and Dabrowa2002b; Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre2013, 264; Chevrollier Reference Chevrollier, Francis and Kouremenos2016, 14). The province was restructured after Actium (the island of Crete and the mainland of Cyrene were joined to create the province of Crete and Cyrenaica).Footnote 12

Why did Octavian decide to give these lands to Capua? It is relevant that the part of Crete where Capua enjoyed possession of land was, and still is, a famous wine-producing region particularly well-suited to producing income. The associated objectives of punishingFootnote 13 Crete and Knossos for pro-Antonine sympathies, the need to compensate Capua for the expropriation, and the importance of the wine trade in both Campania and Knossos could have been reasons for Octavian to assign Knossian lands to Capua. Classical sources speak of this as compensation for the lands confiscated in order to settle a new veteran colony in Campania, in Capuan territory (again, Velleius Paterculus 2.81.2 and Cassius Dio 49.14.5). But why did Capua not receive other lands on the Italian peninsula or the Italian islands instead of this distant Cretan exclave? We know of the complexity of the public lands of Capua.Footnote 14 This colony had other properties, also in the form of prefectures,Footnote 15 that were much more proximate than Knossos. The decision to assign these Cretan lands to Capua was motivated not only by the interests of Capua, but also by Octavian's political plan. This project had two phases: the first was the foundation of a colony called Iulia Nobilis CnossusFootnote 16 after the battle of Actium but before Octavian became Augustus (between 31 and 27 bce);Footnote 17 this was a civilian Roman colony that included some veterans (Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky and Dabrowa2001; Reference Baldwin Bowsky2002a; note that partisans of Antony were specifically settled away from Italy); secondly, the assignation of lands to Capua was due to the commercial and particularly the viticultural interests of Capuan traders in the Aegean.

Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre2013, 262–4) has suggested that this foundation was not a simple settlement, but part of a complete territorial restructuring when Crete and Cyrenaica were joined into a single province, along with the restructuring of other eastern provinces after the battle of Actium. Before the battle, the eastern provinces were under the control of Mark Antony. Cicero provides useful information about how the commander awarded fiscal exemption to the Cretan towns and wished to free the island of Crete: ‘But how blind avarice is! An official notice was posted late in time exempting the richest communities in Crete from taxation and decreeing that, after the proconsulship of Marcus Brutus, Crete should cease to be a province’ (Cicero, Philippics, 2.38.97, tr. Shackleton Bailey Reference Shackleton Bailey2010).

Other sources, such as Plutarch (Life of Antony 36.3) and Cassius Dio (49.32.5), explain that Mark Antony gave Cleopatra and her children some possessions on Crete.Footnote 18 Lefebvre proposed that the choice of Marcus Nonius Balbus (PIR 1 N 102) (already governor of the island) as patron of the province was a way for the Cretan towns to reconcile with Augustus. This title was awarded to a person close to the princeps and was given to Nonius because he had supported Octavian during the period when the latter had been tribune of the plebs in 32 bce (see Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre2013). His activities can be seen in some arbitrations in central Crete (Baldwin Bowsky Reference Baldwin Bowsky1987), and he is honoured on five inscriptions found at Herculaneum dedicated by Knossos, Gortyn and the Cretan Koinon (CIL X 1430; 1431; 1432; 1433; 1434). Biundo (Reference Biundo2004, 402–3) proposed that this fiscal exemption given by Mark Antony to Cretan towns (including Knossos) was still valid for the whole province of Crete and Cyrenaica on the basis of Augustus’ edict (FIRA 1.68), dated 3–6 ce and found on an inscription in Cyrene (see Purpura Reference Purpura2012, 433–86, no. 6.4, lines 55–62). The ‘Lands of Capua’ were likewise exempt from fiscal obligations owing to the status of Capua as an Italian colony privileged under Italian law, as was the revenue (vectigalia) deriving from public property that was partially or totally rented out to Knossian colonists or the Greek inhabitants of Knossos (who had the statues of incolae: see Brélaz Reference Brélaz2017) that accrued to the towns and colonies.

A new reading of the inscription identifying a boundary between Capua and Plotius Plebeius

Having discussed the origins of the ‘Lands of Capua’ and the reasons for their assignment, we turn to the Karnari inscription. Pierre Ducrey (Reference Ducrey1969, 846–52, no. 3 = AE 1969–70, 635) published this inscription, which had been found in Karnari near Archanes, less than ten kilometres from Knossos. It is the most important piece of archaeological evidence for the ‘Lands of Capua’ on Crete. The most recently published picture of the inscription was taken by Géza Alföldy in 1993 and can be seen in the Epigraphic Database Heidelberg.Footnote 19 There is, however, no evidence that the epigraphist revisited the text or reconsidered its implications.Footnote 20

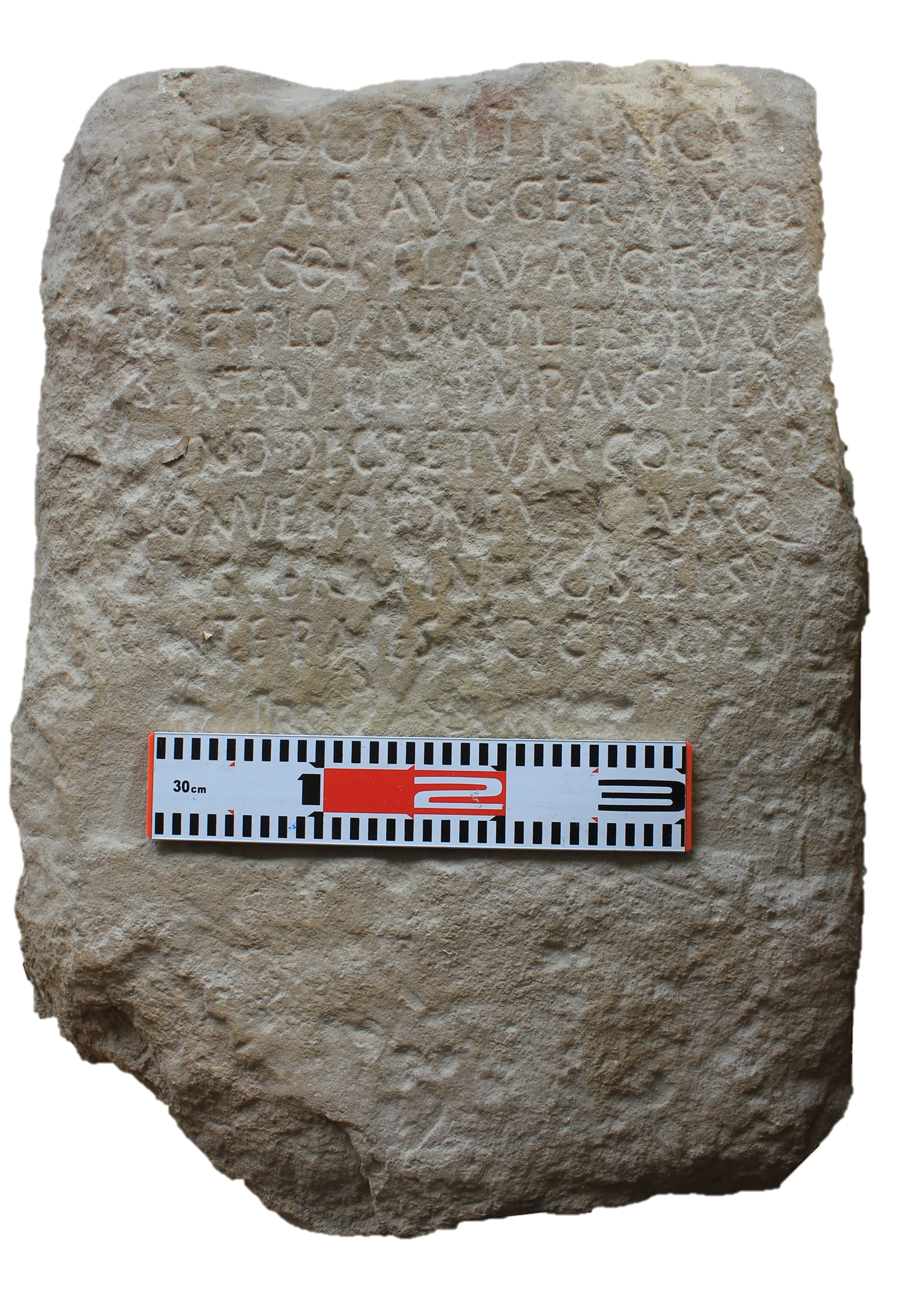

In my Empire-wide study of the boundary stones of Italy and Italian towns, I included the boundary stoneFootnote 21 from Karnari (Archanes) (Fig. 2). In November 2018, I had the opportunity to carry out an epigraphic autopsy of the inscription and observed some differences from Ducrey's reading.

Fig. 2. Boundary stone between Capua and Knossos (author, Nov. 2018).

It is a boundary stone made of brown limestone from local quarries in Knossos,Footnote 22 height 71 cm, width 47.5 cm, thickness 15.5 cm. The inscribed area of the front face has been smoothed and polished while the lower area and other faces are rough. The front face is weathered. Some erosion has affected mainly the upper corners. There are minor chips on some of the letters, as well as various minor nicks, scratches and areas of incrustation.

Eds Ducrey Reference Ducrey1969, 846–52, no. 3 (= AE 1969–70, 635 = Šašel Kos Reference Šašel Kos1979, no. 3). Roman square capitals. Letter height: line 1: 4 cm; lines 2 to 10: 2–3 cm. The inscription is currently kept at the portico of the store room of the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (epigraphic store, catalogue number E 324). Autopsy España-Chamorro, 20th November 2018.

1 ỊMP(ERATORE) ⋅ DOMITIANO

CAESAR(E) AUG(USTO)⋅GERM(ANICO)⋅X⋅CO(N)S(ULE)

Ị(N)TER ⋅ COL(ONIAM) ⋅FLAV(IAM) ⋅ AUG(USTAM) ⋅ FELIC(EM)

C̣AP(UAM) ET PLO(T)IUM ⋅ PLEB[E]IUM

5 [EX]SENTEN(TIA) TỊṬỊ ⋅ IMP(ERATORIS)⋅ AUG(USTI)⋅ ITEM

[SEC]UND(UM) ⋅ DECṚETUM ⋅ COL(ONIAE) ⋅ CAP(UAE)

[EX] C̣ONVENTIONE ⋅ ỤṬ[R]ỊUSQ(UE)

[PAR]Ṭ[I]S ṬERMINI POSITI SUN[T]

AG[E]NTE ⋅ P(UBLIO) ⋅ [M]ESS[I]O CAMPANO

10 PROC(URATORE) C̣ẠṂP̣(ANIAE)

1. [I]mp(eratore) Ducrey || 3. [i]nter Ducrey || 4. Ploṭium Plebeium Ducrey || 5. Tiṭi Ducrey || 7. [c]onventione u[tri]usq(ue) Ducrey || 8. Partis [t]ermini p̣ositi Ducrey || 8. ạgente Ducrey; Mess[i]io Ducrey || 10. [C]a[es]ạṛịṣ Ducrey

Interpuncts in lines 1, 2, 5 (between Titi and Imperatoris) and 7 omitted in Ducrey's edition.

Translation:

When the emperor Domitian Caesar Augustus Germanicus was consul for the tenth time. Between Colonia Flavia Augusta Felix Capua and Plotius Plebeius, according to the decision of the emperor Titus Augustus and following the decree of Colonia Capua, according to the agreement of both parties, boundary markers were placed, through the agency of Publius Messius Campanus, procurator of Campania.

The most important change suggested by this new interpretation of the inscription is in the final line (Fig. 3). Ducrey proposed reading it as proc(uratore) [C]a[es]aris.Footnote 23 This is the least visible part of the text, but a physical autopsy undertaken with different light orientations and by touching the letter traces leaves no doubt that the new reading is correct: the procurator Caesaris (imperial procurator; see Faoro Reference Faoro2011) becomes a procurator Campaniae (procurator of Campania; see Faoro Reference Faoro2017) with historical consequences for the interpretation of the so-called ‘Lands of Capua’. The title of this office is similar to others (i.e. tractus Campaniae – Campania region), only the abbreviations differ (Camp.,Footnote 24 Campan. Footnote 25 or without abbreviation).Footnote 26

Fig. 3. Corrected text (detail, author, Nov. 2018).

This new reading is important for several reasons. It is the only evidence of this post outside Italy and the first in chronological terms; it also gives us more information about the function of these magistracies. Furthermore, it enhances our understanding of the juridical aspects of the ‘Lands of Capua’ on Crete and their historical consequences, including types of land exploitation.

The procurator Campaniae on Crete

The ‘Lands of Capua’ were managed by a procurator Campaniae who would have been in charge of administering Campanian lands and solving the problems related to this region, including the extraterritorial possessions of the colonies.Footnote 27 By contrast, a procurator Caesaris would have been primarily in charge of the imperial financial interests within a specific provinceFootnote 28 and thus should not be linked to the ‘Lands of Capua’. The ancient land surveyor Siculus Flaccus tells us that a temporary magistrate, not a permanent one, managed praefectures,Footnote 29 which suggests that the ‘Lands of Capua’ would have been the responsibility of the procurator Campaniae. This is another indication that the model of the prefecture was deeply embedded and long-term (cf. España-Chamorro Reference España-Chamorro and Dubbini2019, 256–8).

We do not know the exact origin of the office-holder, Messius: his cognomen Campanus is very common in Campania and specifically in Capua (AE 1987, 260; CIL X 3803, 3903, 4158, 4233, 4338, 4425; and in general Kajanto Reference Kajanto1982, 190), but the name Messius is only attested once in Capua at the end of the second century, in the name of the magister P. Messius Q.l. [---] (CIL I2, 2506 = ILLRP 713), who shares the praenomen Publius even though they were a century apart. The assignment of this post not to an imperial freedman, but to an eques (a member of the Roman equestrian order)Footnote 30 in the first years of Domitian's reign can be analysed in light of the later comparanda. The inscription says nothing of the specific role of Publius Messius.Footnote 31 There is, however, evidence for procurators of other regions in Italy who did not have a specific task, such as the procurator of Calabria (M. Bassaeus Axius) or the procurator of Lucania (Q. Calpurnius Modestus). Both were equites, but the second-century ce date is significantly later than the Karnari stone (see CIL X 1795 = ILS 1401; CIL XIV 161 = ILS 1427). Many differences can be detected between this Domitianic procurator and other examples from the second and third centuries. These regional procurators specialised in the different Augustan regions of Italy (Campania as part of Region I with Latium; Calabria as part of Region II with Apulia; Lucania a part of Region III with Brutii), and their geographical names were frequently preceded by the words pars, regio or tractus, meaning that this procurator was in charge of only part of the region (Camodeca Reference Camodeca and Pupillo2007, 161 n. 27; cf. Arnaldi, Cassieri and Gregori Reference Arnaldi, Cassieri and Gregori2013, 67–8, and also Nonnis Reference Nonnis, Demougin and Caballero2014, 189–91).

The designation of an eques as procurator Campaniae in the Flavian period appears to have been part of a response to a generalised problem; it can be understood in the context of the land restitution programme carried out by Vespasian in order to return the occupied subseciva (unused land) to the colonies. Land surveyorsFootnote 32 tell us that this was a widespread problem. Vespasian's son (Domitian) allowed the land users to keep the land through the practice of usucapio (acquisition of the ownership of something by virtue of uninterrupted possession). In this context, Messius Campanus probably had to apply the same regulation as in Italy and also probably in other land disputes related to Capua.Footnote 33

One of the most interesting aspects of this new reading is that it is the first chronological attestation of a procurator Campaniae. This office must have differed greatly in status from the procurators attested in the second and third centuries ce. The fact that Publius Messius was not a freedman but an eques must have corresponded to his special mission, as it could not have been entrusted to a freedman or a senator. Fiscal and patrimonial issues were regulated by an equestrian, whereas senators were sent on special missions where civil and criminal cases needed to be resolved; an interesting example is the case of Iulius Planta in the Tabula Clesiana (see Faoro Reference Faoro2017). The equestrian status of our procurator is, therefore, perfectly comprehensible within the problematic case of the praefectura Campana.

In the specific case of Campania, we know of only three more examples of this position; the title is different, but again this could be due to their different dates. All are dated to the second century ce and were imperial freedmen: Ismarus, procurator Campa[niae]; Acastus, procurator provinciae Mauretaniae Tingitanae et tractus Campaniae (procurator of the province of Mauretania Tingitana and the region of Campania); and T. Aelius Aug.l. [---], procurator tractus Campaniae (procurator of the region of Campania: see Ward-Perkins Reference Ward-Perkins1961, 87, no. 3; CIL X 6081; Lanciani Reference Lanciani1883, 237, no. 669). Publius Messius Campanus is, therefore, the first known procurator Campaniae. This is a very valuable piece of evidence because it sheds light on the earlier phase of these regional procurators and shows remarkable differences with those of the second and third centuries, indicating the evolution of this post.

The ‘Lands of Capua’ as the praefectura Campana

The ‘Lands of Capua’ have been barely studied from the administrative point of view. The direct link of the procurator with Capua makes it possible to review the juridical category and administration of these lands. Taking the information provided by land surveyors into consideration, we can link this special piece of land as a prefecture and have a better idea of this engagement with the Italian colony, its context in Roman territorial administration, and its legal and fiscal aspects.

The question of the juridical category of these lands has yet to be investigated. From the moment they were transferred from Knossos to Capua, they had to be assigned as part of the public lands (ager publicus) of the colony of Capua, categorised in a way defined by the land surveyors. The general scholarly consensus is to think of this kind of exclave as lands subject to Roman taxation (ager vectigalis) and a part of the public places (loca publica) of Capua, based on information from Velleius Paterculus, who only indicates that the expropriated lands of Capua had been public lands (Velleius Paterculus 2.81.2). In line with this, the lands assigned to Capua on Crete could also have been public. However, these public lands must have been under special administration, as they belonged to the type of extraterritorial unit described by the land surveyors as ‘prefecture’ (praefectura). This was a special modelFootnote 34 used to administer scattered plots outside the boundaries of the land assigned to a colony at the time of its foundation (represented in the work of Hyginus Gromaticus; see Fig. 4). Any land could have fallen into this categoryFootnote 35 when it was taken from another town, either when the territory granted to a colony was insufficient or, as in other scenarios such as the case here, it was compensation for a confiscation. The so-called Lands of Capua could, therefore, be called a praefectura Capuensis or better still praefectura Campana.

Fig. 4. Diagram of praefecturae according to Hyginus Gromaticus (Thulin Reference Thulin1913, Lam. 16, figs 78, 79).

Some authors (Laffi Reference Laffi1975, XLII; Keppie Reference Keppie1984, 91 n. 25) have claimed that the use of prefectures as an administrative tool was a temporary solution for land management (see Biundo Reference Biundo2004). In the case of Crete, however, this does not hold, as is demonstrated by evidence from the time of Augustus through to Domitian. Cassius Dio (cf. Biundo Reference Biundo2003, 136) wrote about this topic in the third century ce without mentioning any change in the juridical situation and stating that it was still used in his time. Thus, the praefectura Campana was apparently managed by Capua for at least three centuries.

This system of external landed property was common to Italian towns. In some cases, we also know of land that belonged to Italian towns (mainly colonies like Capua) in provincial contexts far away from their assigned land. One famous case is that of Teanum and its properties and pagus (an extra-urban community linked to the colony) in the ager of Carthage (Proconsular Africa, CIL VIII 25966). Other Italian cases are mentioned by Cicero (Letters to Friends 13.7–11): the towns of Atella and Arpinum had lands in Gallia Cisalpina, while the town of Regium had properties outside Italy, although we do not know where they were located (see Biundo Reference Biundo2004, 374–6). We also find interesting cases involving provincial towns: Augusta Emerita (Lusitania) is one of the best studied examples because we know of at least four prefectures from literary sources and epigraphy.Footnote 36 There is another example relating to the prefecture of UcubiFootnote 37 (Baetica), again far away from the main colony. Other examples could be the colony of Arelatum (Gallia Narbonensis) and the town of Serdica (Moesia Inferior), which had external properties within the juridical system of the prefecture far from their urban centre (España-Chamorro Reference España-Chamorro2017, 121–5).

What exactly is a Roman prefecture? Based on evidence from land surveyors, we can envisage two different systems of prefectures:Footnote 38 (a) land divided and assigned to veterans with a cadastral map showing the assignation and (b) public properties that belonged to the colony within the juridical responsibility of a public person.Footnote 39 This system envisaged the colony as a juridical entity that could receive lands in the form of a prefecture. There are contradictory indications in Siculus Flaccus’ texts (De Condicionibus Agrorum 160.5–7), but we can observe that sending magistrates to the prefectures reveals a jurisdictional and administrative dependency, but not a patrimonial one. A patrimonial dependency is only possible in the case of forests and pasture lands, not public rented land as in this case. These properties can be considered as public places and would have been governed under public law. As for the praefectura Campana, these lands were not simply directly assigned to veterans by means of a colonial foundation, as happened for example in Augusta Emerita. Consequently, we can consider that they were divided in order to rent them out.Footnote 40 Renting them subject to Roman taxation was one way of exploiting these distant lands because it ensured a long-lasting system of rental yields. So as to avoid boundary disputes, the plots were probably recorded on a cadastral mapFootnote 41 kept in the Capua archive.Footnote 42 The maps allowed these new lands to be controlled, even if they were not measured like the divided and assigned plots. Indeed, there is no sign of a grid in the topography of the Knossos valley. In the context of a boundary dispute, the cadastral map of the Knossos territory was probably consulted by the proconsul and presented to Titus in order to secure the restoration of taken lands. The procurator would probably have consulted his Capuan counterpart to gain a broader, clearer idea before going to Crete.

This model of prefecture does not conflict with considering these lands as public property of the colony divided as communal land leased in exchange for rent (ager vectigalis). On the contrary, this was a very common arrangement for land division in provincial towns (Paci Reference Paci1999, 64) and a common way of managing extraterritorial lands.Footnote 43 Biundo (Reference Biundo2003, 134–5) wondered whether these lands were considered in the same terms as the Italian properties, which would mean that they had fiscal exemption. In this way, lessors would pay not only the incomes to Capua, but also the tribute as in rent-paying land. The new link with the procurator Campaniae as opposed to Caesaris proves that these lands were considered Italian land from the administrative, juridical and fiscal points of view, and explains why Publius Messius Campanus was involved in order to protect the interests of Capua on Crete. As previously mentioned, the general problem of the restitution of subseciva in the Flavian period probably involved Messius Campanus in other similar Italian problems due to its charge.

Another important aspect is the management of these lands. Perhaps the famous inscription found in Capua (CIL X 3938 = ILS 6317) that mentions a treasurer and controller of public revenue from Crete is key to understanding this aspect. The function of this person was certainly related to the collection of the income due to the praefectura Campana. Velleius Paterculus indicates that these lands produced 1,200,000 sesterces annually (Panciera Reference Panciera2006, 756–7; cf. Paci Reference Paci1999, 71 n. 44).

THE BOUNDARY DISPUTE AND ROMAN LAW

The juridical process and the property dispute between a public entity and a private owner

Having analysed the procurator and the juridical category of lands, it is now time to explore the dispute. The new interpretation enhances our understanding of the whole legal process by enabling a reconstruction of its chronological development from Augustus to Domitian. Contextualising this specific dispute within Roman law and the information provided by land surveyors, we can categorise the Karnari inscription as a boundary dispute between a public entity (Capua) and a private owner (Plotius Plebeius). This allows us to further evaluate the historical significance of the Karnari inscription.

The juridical process

Unique aspects of the Karnari boundary stone inscription enhance our understanding of the juridical process. Normally, such inscriptions mark the final stage of a long property dispute process. We rarely find any information in them about the judicial process prior to the resolution. In this case, however, some clues allow us to reconstruct that process and in particular the role of the arbiter (the Emperor Titus) and the public pleader (who both represented Capua and carried out Domitian's verdict). The new reading demonstrates the latter's position as an Italian magistrate specific to Campania. The chronology of this dispute can be reconstructed as follows:

• The dispute took place around 79–80 ce, if not before, to judge from the date of Titus’ brief reign;

• Plotius Plebeius brought his complaint to the provincial governor of Crete-Cyrenaica, who remitted the case to the Emperor Titus;

• Consequently, Capua promulgated a decree delegating the juridical power to Publius Messius Campanus, who was procurator Campaniae;

• The arbitration took place over the following years and the resolution occurred in the summer of 81 ce at the latest, again to judge from the date of Titus’ brief reign;

• The boundaries were established during the tenth consulship of Domitian (84 ce). Publius Messius Campanus applied the imperial decision at that time.

It is interesting that the date of this boundary stone, 84 ce in the tenth consulship of Domitian, matches that of another found on the opposite side of the Mediterranean in Cisimbrium, Hispania.Footnote 44 The boundary stones from Karnari (Archanes) and Cisimbrium (Priego de Córdoba) are the first such examples in Domitian's reign.Footnote 45 Presumably, Domitian first resolved old, unfinished cases before moving on to other territorial disputes. We also know of Domitian's involvement in issues surrounding recurrent boundary disputes. One is the sacred land of the temple of Artemis in Ephesus (Engelmann Reference Engelmann1999, 143–6 no. 4; Elliot Reference Elliot2004, 172 no. 61.9), a conflict that began in the time of Augustus and ended under Trajan. Another unresolved case was that of the prefecture of Ucubi, which began under Vespasian.Footnote 46 Two later pieces of evidence under Domitian seem to be unrelated to previous cases.Footnote 47 Finally, another interesting inscription from Rhytion (ICr I 49.1, in Greek), also on Crete, records a resolution under Hadrian concerning another arbitration that was active in the reign of Domitian and goes back as far as Augustus and probably Metellus in the mid-first century bce.

The Cretan boundary stone states that both parties came to a mutual agreement. This is preceded by the expression ‘according to the verdict’, the most common method throughout the Empire of referring to boundary verdicts (Elliot Reference Elliot2004, 28). However, mutual agreement does not seem to be the case here, as the imperial authority became involved in the judicial process. Aichinger (Reference Aichinger1982, 195) proposed that the presence of two different jurisdictions was a reason to involve the emperor. In fact, disputes between two different provinces or jurisdictions, as we see in this case, had to involve the emperor.Footnote 48 We can see this from other boundary stones, including those from Augusta Emerita, for example. The new reading goes a step further as it shows that the agreement was not literally made by local people,Footnote 49 but required the procurator Campaniae to travel from Italy to Crete, and also involved the emperor. Messius was also sent to Crete by the emperor himself on a special and atypical mission concerning a longstanding problem. For arbitration trials between towns, the resolution (sententia) had to do with the substance and the effects, while the decretum indicated who performed the arbitration and how it was carried out, with prior knowledge of all the circumstances from both parties (Cortés Bárcena Reference Cortés Bárcena2013b, 275).

Further peculiarities are illustrated in this text. Firstly, it is a Latin inscription in a region that predominantly used Greek for both public and private epigraphy,Footnote 50 and it shows once again that Latin was the language used for inscriptions involving imperial authority. Secondly, this boundary stone is related to an exclave, which means it involved non-contiguous territory. This piece of land is in fact more than 1150 km from the juridical centre to which it belonged (see Fig. 1). Thirdly, and most importantly, is the relationship between the two parties of the dispute. New studiesFootnote 51 of boundary stones allow us to divide them into different juridical categories. This example can be included among the disputes between a public entity (Capua) and a private owner (Plotius Plebeius) (cf. Castillo Pascual Reference Castillo Pascual1996, 184–5; Cortés Bárcena Reference Cortés Bárcena2013b, 244), discussed by the land surveyors (Aegenius Urbicus in Lachmann Reference Lachmann, Lachmann, Blume and Rudorff1848, 84.29–85.4 = Thulin Reference Thulin1913, 45.16–22) in the Roman treatise on land surveying. However, compared to other kinds of disputes (between a public entity and a private owner), the epigraphic evidence for these is scarce because disputes among such parties usually reached a resolution without the intervention of imperial officials (arbitri).

We can see a great deal of variety in the relatively few examples of boundary stones related to this kind of dispute that features imperial involvement. The closest parallel is a dispute from the province of Macedonia between the colony of Philippi and a private landowner, Claudianus Artemidorus,Footnote 52 which was also resolved by the Emperor Trajan himself (judging by the expression used in the text).Footnote 53 Another very similar boundary dispute is that of Kalaat-es-Senam (Le Kef, Tunisia) in Africa Proconsularis.Footnote 54 This territorial dispute between the territory of the Musulamii, an imperial assignation of land to an ethnic group (España-Chamorro Reference España-Chamorro, Salcedo, Benito and España-Chamorro2018), and the landowner Valeria Atticilla is remarkably similar to that of the Karnari (Archanes) boundary stone. Not so far away, in Sidi BouzidFootnote 55 (Fedjana, Algeria), in the province of Mauretania Caesariensis, there is yet another boundary stone between a community of Tabianenses (the town of Tabia or the castellum Tabianense) and land attributed to the veteran Surus. It presents a similar juridical category, but with a very different text. The last piece of evidence is from Dalmatia, between a territory assigned to a legion and a private forest.Footnote 56 In all of these cases, the texts and their chronology vary considerably. The only aspect in which they concur is the order in which the parties to the dispute are mentioned: the public party is mentioned first and the private party second (cf. Gascou Reference Gascou1992, 60 n. 22).

The public party: a hitherto unattested cognomen Flavia for the colony at Capua

This document is also very important as it contains the only attestation of the cognomen Flavia in the official name of Capua. Ducrey (Reference Ducrey1969, 848–9) and Rigsby (Reference Rigsby1976, 320) believed that this could be testimony to a commemorative title symbolising the pietas of Vespasian after he had pardoned the colony for their support for Vitellius. Another theory also mentioned by Ducrey (Reference Ducrey1969, 848–9) is that, for some reason, this title was given to Capua by Domitian and was removed after he died and was condemned to oblivion by the Senate.

Keppie (Reference Keppie1984, 96), however, has proposed that it is not possible to consider the clemency of Vespasian after he sent the legio III Gallica hiemandi causa there, in order to contain possible riots and any subsequent damage in the colony. Pliny, however (Natural History 14.62), tells us that VespasianFootnote 57 gave the Sullan colony of Urbania to Capua in the form of a contributio (see Laffi Reference Laffi1966). This demonstrates a Vespasianic programme to settle veterans from the Jewish Wars in Capua, aimed at strengthening his position as emperor, as Augustus did. This would have been a good reason for giving Capua the cognomen Flavia. This new evidence makes Capua the third colony with the cognomen Flavia in Campania. The others were Puteoli, colonia Flavia Augusta, and Paestum, colonia Flavia Prima. There is no Flavia cognomen for Nola, colonia Felix Augusta, but thanks to the land surveyor's information we know of a new colonial re-foundation in the age of Vespasian.Footnote 58

Why, then, is the cognomen Flavia present for Capua only in this inscription? It is not necessarily the case that its disappearance indicates Domitian's intervention.Footnote 59 We can see other cases of erased cognomina, e.g. Puteoli, named colonia Neronensis Claudia Augusta Puteoli before Vespasian (Ginsberg Reference Ginsberg, Augoustakis and Littlewood2019, 30), or Arausio, colonia Iulia Firma Secundanorum, renamed colonia Flavia Tricastinorum by Vespasian (Gilman Romano Reference Gilman Romano and Fentress2000, 102 n. 64). The closest example of this kind of name change is at Corinth, where we can see the same process (Gilman Romano Reference Gilman Romano and Fentress2000, 104 n. 79): initially named colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis, it was re-founded and thus renamed by Vespasian as colonia Iulia Flavia Augusta Corinthiensis. This was the official name only for a short time (70/77–96 ce). After Domitian's death, the colony reverted to its earlier name. Accordingly, it seems that the cognomen Flavia present in this Cretan inscription corresponds to Vespasian, as in the other colonies in Campania and Corinth. The reason for the disappearance of the title in Capua and Corinth is not clear. Gilman Romano (Reference Gilman Romano and Fentress2000, 104 n. 79; Reference Gilman Romano, Williams and Bookidis2003, 291) has proposed that, in the case of Corinth, its re-foundation was never completed, and therefore it reverted to its former name. Given the absence of other evidence, we might entertain the notion that the process was the same for Capua.

The private party: Plotius Plebeius

We do not know exactly where the property of Plotius Plebeius was situated, but apparently the boundary stone was found on the limit between the private property of Plebeius and the public property of Capua. The nearest town in the area is Knossos, and the other party in the dispute was the colony of Capua, whose public lands were located in the former territory of Knossos, according to classical authors. Thus, there is no doubt that the property of PlotiusFootnote 60 belonged to the territory of Knossos. Further evidence is the prosopography of the area. One of the first magistrates (duumvir) of the Augustan colony of Knossos was a homonymous Plotius Plebeius, known from the numismatic evidence (see Münsterberg Reference Münsterberg1911, 125 = RPC 1.978) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Coin of the Augustan duumvir Plotius Plebeius (RPC 1.978) (Münzkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin).

According to the inscription, the second Plotius Plebeius was a member of the colonial elite, nearly a century after the magistrate named on colonial coinage. Both seem to have been from the same family, and they apparently did not move away from Knossos. There is further evidence for two other landowners in and around the Capuan lands: closed water pipes from Rhaukos and Asites that name a Va(r)ro (ICr I xxvii.4; SEG XXIII 531), and an inscription naming a slave of M. Claudius Thettaliskos at Karnari (Kritzas Reference Kritzas, Carinci, Cucuzza, Militello and Palio2011). There is no evidence of problems with them or other landowners in the area.

The territorial area of the praefectura Campana (Lands of Capua)

By comparison, the extent of the praefectura Campana is not well defined (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, the proposal put forward by Rigsby (Reference Rigsby1976, 326–7) with some clarification from Baldwin Bowsky (Reference Baldwin Bowsky1987) gives us some idea. Such problematic pieces of land had to be limited mainly by natural features.Footnote 61 The northern border is relatively clear: it stretches from Mount Iuktas and the Archanes valley,Footnote 62 Karnari (the findspot of the boundary stone of this article) and Lycastus;Footnote 63 Asites and Rhaukos could mark the possible maximum extension to the north-western border. It is probable that the prefecture was limited by the Giofiros River to the west, and also by a natural corridor that directly linked Knossos to Gortyn. Perhaps both, river and corridor, were taken as boundary elements.Footnote 64 We have no epigraphic or archaeological evidence to fix a limit in the southern part, although the mountains between Roukani and Arkadi would have been a good natural feature. The eastern border is also complicated, but perhaps the mountains next to Partheni would have been a suitable limit. Thus, the fertile parts of the valley and the plateaux amount to around 50–60 km2. This calculation roughly coincides with Biundo's (Reference Biundo2003, 136) calculation, which estimated that 1,200,000 sesterces a month could correspond to c. 20,000 iugera of productive land, i.e. around 50 km2 (Figs 7 and 8).

Fig. 6. The extension of the praefectura Campana (author).

Fig. 7. Archanes valley landscape looking south (author, Nov. 2018).

Fig. 8. Archanes valley landscape looking north towards the coast (author, Nov. 2018).

CONCLUSIONS

This new reading allows me to propose a different version of this important text with a number of significant historical consequences. This first attestation of a procurator Campaniae, and also the first one outside of Italy regarding the management of the Lands of Capua, gives us a clue as to the extent of the jurisdiction of these procuratores and their involvement in the arbitration processes. It also proves that these lands had the juridical status of Italian land from the administrative, legal and fiscal points of view. There are, however, many differences between this early equestrian procurator and the already-known second- and third-century procurators who were imperial freedmen.

The new approach helps us to understand this unprecedented situation and also makes it possible to reconstruct the legal process. This boundary dispute must be understood in the category of a dispute between a public entity and a private owner, and also of one between a province and Italian land. Comparing this dispute with the information provided by land surveyors, we must think of the juridical management of a prefecture, which could have been called praefectura Capuensis, praefectura Campana or, from the Capuan point of view, praefectura Cnosiensis or Cretensis.Footnote 65

As we have seen above, the Roman prefecture system ensured the correct administration of the new public land and converted it into communal land leased in exchange for rent (ager vectigalis). No fixed settlement of veterans has been attested in these lands; instead, it was rented to Greek citizens from Knossos (Tzamtzis Reference Tzamtzis and Czajkowski2020, 253). The assignation of these distant lands was linked to Cretan wine production. In fact, archaeological evidence in Campania has demonstrated an active trade in these wines from the first century ce, and this may have been a very good way of compensating the colony of Capua for the expropriation of its land. This constituted a continuation of late Hellenistic trade and transhipment, one that may have been put to new uses in the imperial period. Gallimore (Reference Gallimore2019) has shown that infrastructure development and increased economic connectivity by the mid-first century ce had an impact upon not only Knossos but also all of Crete.Footnote 66 Perhaps the praefectura was, in the end, a long-lasting factor in the maintenance of the Campanian–Cretan and/or Capuan–Knossian relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is based upon my postdoctoral project (Corpus Terminorum Italiae Antiquae – CoTIA), recently awarded the Géza Alföldy Stipend – Research Award – 2020 by the Association Internationale d’Épigraphie Grecque et Latine (AIEGL). I have received funded support both from the Escuela Española de Historia y Arqueología en Roma (EEHAR-CSIC) and also my IdEx project (Initiatives d'excellence) at the Institut Ausonius (Bordeaux). I thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and stimulating comments. I am grateful to the Co-Editor, Peter Liddel, for his patience and understanding. This paper has also received numerous helpful comments from Lina Girdvainyte as well as Alberto Dalla Rosa, Gian Luca Gregori, Carolina Cortés Bárcena and Sophia Zoumbakis.