Introduction

Government policy performance is an important source of political trust. When governments perform well, the public is inclined to have high levels of trust toward them (Weatherford Reference Weatherford1992; Hetherington Reference Hetherington2005; Yang and Holzer Reference Yang and Holzer2006). This principle can also be applied to authoritarian systems. Empirical studies have found that the performance of China’s government in promoting economic growth bolsters public trust (Chen Reference Chen2004; Lewis-Beck, Tang and Martini Reference Lewis-Beck, Tang and Martini2014; Tang Reference Tang2005, Reference Tang2016; Zhai Reference Zhai2016, Reference Zhai2021). However, existing literature excessively stresses the positive effects of economic performance on the public’s trust in government. That is to say, it neglects the fact that government performance is confined not only to the economic field but also in social and political fields that equally affects public trust (or distrust) in the government (Zhai Reference Zhai2019, Reference Zhai2022). For example, performance regarding the control of corruption and the protection of people’s civil liberties and political rights are important to citizens’ evaluation of government. In particular, the Chinese public has gradually shifted its attention from basic economic security to quality-of-life issues, engendering new challenges for the one-party state. Air pollution and food safety have drawn widespread public concern, and these quality-of-life related problems have far-reaching political influence (Wike and Parker Reference Wike and Parker2015; Wu, Yang and Chen Reference Wu, Yang and Chen2017; Han and Zhai Reference Han and Zhai2022).

Examining the effects of government policy performance on political trust must account for the multilevel governmental system. In China, central–local relations are determined by the authoritarian unitary system. The central government possesses the power to appoint local government officials and to distribute resources between the central and local governments (O’Brien and Li Reference O’Brien and Li2006; Cai Reference Cai2008; Fan Reference Fan2015; Han and Zhai Reference Han and Zhai2022). Based on central–local government relationships, the effects of government performance on political trust may vary across different levels of government. Local governments risk losing public trust in certain policy domains, whereas the central government loses public trust in other areas. Apart from government’s economic performance, the relationship between government performance in other policy domains and central–local political trust has been inadequately researched. This investigation involves central–local government relationships in China and is relevant to the survival or decay of authoritarian systems.

This study established a theoretical framework to examine complex relationships between government performance in various policy domains and central–local political trust. First, we adopted a noneconomy-centred perspective, considering government performance in various policy domains. It is important to consider government policy performance in the fields of income inequalities, political corruption, environmental protection, food safety, and education. Public evaluations of these policy issues influence their level of political trust. Hence, we examined citizens’ evaluations of government policy performance in these fields. Second, we did not view “government” as a single entity. Instead, we examined the effects of government performance in various policy domains on public trust in local and central governments, respectively. It is unclear whether government performance in various policy domains has identical or differentiated effects on public trust in local and central governments. We were interested in possible variations among different levels of government. Third, we examined three major central–local political trust patterns: parallel trust, pyramidal trust, and hierarchical trust. Hierarchical trust is particularly beneficial to the survival of China’s one-party system, while pyramidal trust has the opposite effect. We examined the effects of government performance in various policy domains on the three central–local political trust patterns. The results show variations in the effects of government performance on these different central–local political trust patterns. These findings have important political implications for China’s political future.

Different policy issues and public attribution of administrative responsibility to central–local levels

Multiple theories have sought to explain political trust in China. The cultural approach attributes sources of political trust to Confucian cultural heritages (Shi Reference Shi2014; Zhai Reference Zhai2018). The political control approach views trust in government as the outcome of state censorship of the media such as information control and sophisticated framing (Wu and Wilkes Reference Wu and Wilkes2018). Among these factors, government performance is particularly relevant. China has undergone rapid economic development in the past few decades, and ordinary people’s standard of living has improved substantially. Moderate levels of satisfaction with government’s economic performance have helped increase the Chinese public’s trust in government. However, government performance is not merely confined to the economic realm. Rather, it comprises various policy domains, ranging from social to political. Previous studies have demonstrated that, when evaluating practical government performance, the public distinguishes between policy outputs in the economic and political fields (Bratton and Mattes Reference Bratton and Mattes2001; Chu, Bratton, Lagos, Shastri and Tessler Reference Chu, Bratton, Lagos, Shastri and Tessler2008; Zhai Reference Zhai2019). The present study examined government performance in various noneconomic policy domains, such as income inequalities, political corruption, environmental protection, and so on.

First, in terms of wealth distribution, China’s Gini coefficient has surpassed that of the USA (Xie and Zhou Reference Xie and Zhou2014). Widening income disparities have reached very high levels (among the world’s worst), triggering widespread public discontent and even mass protests (Lin Reference Lin2016; Zhou and Jin Reference Zhou and Jin2018; Lei Reference Lei2020). Unsatisfactory performance in ameliorating income inequality may have negative effects on the public’s trust in government. Second, corruption is associated with government’s political performance, becoming an important element of public evaluation (Saich Reference Saich2016; Habibov et al. Reference Habibov, Fan and Auchynnikava2019). Beginning in 2012, President Xi Jinping launched a high-profile crackdown on government corruption. The paradox of an anticorruption campaign is that, on the one hand, punishment of corrupt officials helps the current administration obtain public support. On the other hand, disclosing corruption makes people aware of the issue’s severity. Thereby, the untrustworthiness of the government is underscored. The anticorruption campaign is a double-edged sword, and its effects require systematic evaluation. The above-mentioned income inequality and political corruption are important policy domains of government performance (which are unrelated to economic growth). They affect public trust in the government.

Moreover, improvement of average citizens’ standard of living has promoted a gradual shift in attention, from basic economic security to quality-of-life issues (such as environmental pollution and food safety problems). Air pollution, such as PM 2.5 (particulate matter with diameters of 2.5 micrometers or less), has aroused public concerns about personal health. In a Pew’s survey, 76% of Chinese people ranked air pollution as a problem, indicating that it is one of the public’s top concerns (Gao Reference Gao2015; Kahn Reference Kahn2016). As a result, ordinary people have begun to doubt the government’s capability and efforts in tackling this issue (Zheng Reference Zheng2015; Lo Reference Lo2017). Food safety is another concern that imposes new challenges to government performance. Melamine-tainted milk powder, the gutter oil incident, illegal use of Sudan dye as a colour additive, and various food safety scandals have resulted in growing public concern and fury (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Pieniak and Verbeke2013; Han and Zhai Reference Han and Zhai2022). Thus far, the effects of government performance in these quality-of-life areas on public trust have not been fully investigated. Some studies address government performance in a certain policy domain, yet do not incorporate results with performance in other policy domains. Therefore, it is impossible to systematically examine their overall effects on public trust in government. The present study examined the effects of government performance in various policy domains (including economic, social, and political) on public trust.

Citizens’ evaluations of government policy performance may vary across different levels of government. The political hierarchy has multiple levels of government (Lieberthal Reference Lieberthal1995), with central–local government relations controlled by an authoritarian unitary system. Within the formal political system, the central government has dominant power over local governments. Personnel control and resource control are two major means by which this authority is exerted. The central government has the power to appoint and promote local governments’ officials, as well as the power to evaluate local governments’ performance (O’Brien and Li Reference O’Brien and Li2006; Cai Reference Cai2008; Han and Zhai Reference Han and Zhai2022). The careers of local government officials depend on the evaluation of the central government. These assessments are not necessarily capability based. Connections play an important role in officials’ promotion, creating room for patron–client relationships and corruption. There are no true elections; thus, government officials choose to respond to upper-level governments rather than to ordinary people. In addition, the central government has the final say on resource allocation between itself and local governments. Tax sharing and fiscal transfer further strengthen the dominant role of the central government (Wang and Ma Reference Wang and Ma2014; Fan Reference Fan2015). Delegating part of the fiscal and policy-making power to local governments is both pragmatic and instrumental. The true aim is to provide incentives for local governments to promote economic development. Decentralisation never means a pluralist power structure and independent local governments. Moreover, it does not indicate a weakened capability of the central government to control local governments (Zhang Reference Zhang, Garnaut, Golley and Song2010). Despite certain degrees of fiscal decentralisation and social autonomy, an authoritarian political system with high levels of political control remains intact in China (Li Reference Li2010; Choi Reference Choi2016; Chung Reference Chung2016).

Although China has a unitary government, a division of power exists between the different levels of the government. The concentration of power means the concentration of responsibility and blame (Weaver Reference Weaver1986; Cai Reference Cai2008). The one-party system relies heavily on the politics of central–local relations. The multilevel government system reduces pressure from popular resistance forces by granting a certain degree of power to local governments and allowing them to handle several instances of resistance (Cai Reference Cai2008; Han and Zhai Reference Han and Zhai2022). On the one hand, citizens’ attribution of responsibility to the different government levels is affected by perceptions of the formal administrative structure. In general, the central government plays a leadership role in policy-making and conducts top-down supervision. The local government implements various policies. In most cases, both central and local governments have separate responsibilities in a specific policy domain. On the other hand, the central government tends to shift citizens’ dissatisfaction toward local governments to avoid public blame. Local governments are responsible for a wide range of activities, such as the enforcement of regulations and public service delivery. Moreover, political control such as media censorship prohibits criticism of the central government and leads citizens to attribute administrative responsibility to local governments. In particular, when a specific government performance is severely unsatisfactory, the Chinese public complains and blames local governments. This attribution of responsibilities to different levels of the government helps enhance the resilience of the authoritarian political system.

This study established a framework to examine citizens’ evaluations of government policy performance based on the perceived administrative responsibility of different government levels. Further, this framework enables the investigation of the effects of their evaluation of government performance in various policy domains on central–local political trust. As shown in Figure 1, aside from the economy, government policy performance is considered in several policy domains, including environmental protection, income inequalities, and political corruption. Citizens’ political trust is divided into trust in the central and local governments. Political trust is affected by the perceived administrative responsibility of the two levels of government by the citizens. Three parties are believed to assume administrative responsibilities for various policy performances: the central government, local governments, and both the central and local governments. The attribution of administrative responsibility depends on citizens’ perception of the level of government that bears primary responsibility for specific public policy issues.

Figure 1. The theoretical framework for the effects of government performance in various policy domains on political trust in multilevel governments.

Because of the multilevel government system, people disburse responsibility across different levels of government (Ferrer Reference Ferrer2020; Han and Zhai Reference Han and Zhai2022). Such stratification creates indeterminacy as to which level of government is responsible for a specific policy area (Li Reference Li2010). The public attributes major responsibility for various policy domains to either the local or central government, based on individuals’ perceptions of which level should bear chief accountability. For example, citizens may attribute major responsibility for different policy domains to either the central or local government, respectively. Examples of these areas include environmental protection, corruption, and food safety. Moreover, the effects of government policy performance on public trust in government vary across different levels of government. Unsatisfying government performance in a certain policy domain may undermine public trust in local governments, but does not affect trust in the central government, and vice versa. Nevertheless, these are not simple either or questions; rather, it is possible for both local and central governments to lose public trust due to poor performance in a particular policy domain. Empirical examination is required to assess specific effects of performance in various policy domains on public trust in local and central governments, respectively.

Public trust in different levels of government and central–local political trust patterns

Public trust varies across different levels of government. In most countries, public trust in local governments is higher than in the central government. Diverging from this pattern, the Chinese public tends to have a higher level of trust in the central government than in local ones (Li Reference Li2004, Reference Li2016; Chen Reference Chen2017; Wu and Wilkes Reference Wu and Wilkes2018). This Chinese exception to the central–local political trust pattern is labelled as “hierarchical trust.” The Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) has documented the dynamics of public trust in China’s local and central governments over the past two decades. We analysed the data from four waves of ABS. The results are presented in Figure 2. The number of Chinese people trusting the central government has been above 90% since the 2000s. The number of people trusting local governments has fluctuated between 60% and 80%. Longitudinal, empirical evidence demonstrates that public trust in the central government has consistently been higher than in local governments.

Figure 2. Public trust in the local and central governments in China (2002–2016).

There are various reasons for such central–local political trust pattern. First, authoritarian political culture constructs a benevolent image of central authorities, kindly caring for ordinary people’s welfare (Pye Reference Pye1988; Perry Reference Perry2008; Zhai Reference Zhai2017). “Central policies are very good, but they are all distorted when they reach lower levels” (Li Reference Li2004, 232). Under the socialisation of authoritarian culture, ordinary people believe that central authorities make policies favourable to people’s interests. In contrast, they see local governments as violating these policies and harming people’s welfare. Second, the multilevel structure of government cultivates such hierarchical trust. Local policy processes and outcomes can be affected by nonlocal factors and actors (Laffin Reference Laffin2009). Beyond their actual performance, low levels of public trust in local governments are related to China’s power structure and power division. Local governments must deal with various issues, including public sentiment and unpopular policies. In addition, arbitrary means of addressing these issues exacerbate public distrust in local governments (Cai Reference Cai2008; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Yang and Chen2017). Less satisfying performance is a major reason for lower trust in local governments. Third, the CCP’s ruling strategies political control may account for hierarchical trust (Wu and Wilkes Reference Wu and Wilkes2018). When social problems occur, the CCP stresses that the party stands behind with the people, blaming local authorities for betraying people’s confidence (Li Reference Li2004; Steinhardt Reference Steinhardt2017). Ultimately, the Chinese public has a higher level of trust in the central government than in local ones.

The multilevel government system engenders further examination of central–local political trust patterns. Previous studies have attempted to construct central–local political trust patterns in accordance with the differences between trust in local governments and trust in the central government (Li Reference Li2016; Wu and Wilkes Reference Wu and Wilkes2018). Accordingly, central–local political trust relationships are divided into three patterns. Trust in the local government is a) equal, b) higher, or c) lower than in the central government. These three central–local political trust patterns were termed parallel trust, pyramidal trust, and hierarchical trust (Wu and Wilkes Reference Wu and Wilkes2018). We used this typology to analyse the effects of government performance in various policy domains on people’s adherence to specific central–local political trust patterns.

The central–local trust pattern has important political implications. As previously stated, hierarchical trust is dominant in China. High levels of hierarchical trust can explain seemingly paradoxical phenomena in China’s politics. During the past few decades, a variety of protests have arisen. Particularly in the early 1990s, the labour movement was rampant in major cities (Lee and Friedman Reference Lee and Friedman2009). Workers who had been made redundant from the previously dominant state-owned corporations (SOCs) walked out in protest when they were declared bankrupt. In rural regions, there have been protests on a number of issues, such as tax collection, land expropriation, and corruption in village committees (Bernstein and Li Reference Bernstein and Li2000; Guo Reference Guo2001; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2002). In urban areas, the middle class has been mobilised to protect the environment. They consider themselves to have a natural “right” to enjoy a healthy environment. A famous case was the protests in Xiamen (Amoy), Fujian Province, which successfully forced the government to relocate a chemical plant. Some observers viewed this rising tide of popular protests as a challenge to both political stability and the legitimacy of the CCP’s rule (Chang Reference Chang2001; Gilley Reference Gilley2004; Pei Reference Pei2012, Reference Pei2016). However, these protests target local governments and specific officials rather than the central government. Accordingly, they have not shown signs of lethal threat to the authoritarian regime (Lee and Friedman Reference Lee and Friedman2009; Perry Reference Perry2009; Wasserstrom Reference Wasserstrom2009). Moreover, grassroots protests even utilise the central government’s regulations or policies to stress the legitimacy of their activities, a practice known as “rightful resistance” (O’Brien and Li Reference O’Brien and Li2006). Hierarchical trust indicates that, in the midst of growing social contestation, the Chinese public has a heavy reliance on (and trust in) the central government.

Citizens’ level of satisfaction with government performance may affect different central–local political trust patterns. Maintaining high levels of hierarchical trust is beneficial to the maintenance of the CCP’s authoritarian rule. Thus far, it is unclear how government performance in various policy domains affects central–local political trust patterns. Does government performance in a certain policy domain facilitates hierarchical trust, pyramidal trust, or parallel trust? As there are variations in government performance in different policy domains, specific and separate effects should be examined. If government performance in a certain policy area increases pyramidal trust, or suppresses hierarchical trust, a real threat to the CCP’s rule is indicated. Such a tendency would mean that the public is withdrawing its trust in the central government. Declining trust in the central government endangers the survival of China’s authoritarian system.

Data and methods

Data

We use the Chinese data set of the fourth round of the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS).Footnote 1 The survey was conducted by face-to-face interviews from July 2015 to March 2016. The Census Yearbook from the National Statistics Bureau was used as the basic source to select the primary sampling units (PSUs) and a total of 125 PSUs were drawn across the nation. A representative sampling method of probability proportional to size (PPS) was applied to randomly select respondents. Residents aged 18 years and above in the sampled community were recruited. The response rate was 67.65%. In mainland China, 4,068 valid samples were obtained with a mean age of 48.27 years (standard deviation (SD) = 16.31 years).

Measures

Trust in government was measured at the central and local levels. Following previous studies (Tolbert and Mossberger Reference Tolbert and Mossberger2006; Yang and Holzer Reference Yang and Holzer2006), trust in government was measured by asking respondents to indicate the extent of their trust in central and local governments on a six-point scale from 1 (strongly distrust) to 6 (strongly trust).

According to Wu and Wilkes’ (Reference Wu and Wilkes2018) methods, a variable of the central–local political trust pattern was created using a three-point scale, from 1 to 3. The categories of this variable represent three types of central–local political trust patterns. Those whose trust in the local government was equal to their trust in the central government were assigned to the first group and coded as 1 (parallel trust). Those whose trust in the local government was higher than their trust in the central government were assigned to the second group and coded as 2 (pyramidal trust). Those whose trust in the local government was lower than their trust in the central government were assigned to the third group and coded as 3 (hierarchical trust). This variable was a nominal variable, with the scores representing different categories (rather than numeric values). When used as a dependent variable, multinomial logistic regression estimation is an appropriate method for conducting analysis (Tutz Reference Tutz2011).

Government policy performance was measured by multiple indicators in various policy domains: economic growth, environmental protection, income inequality, political corruption, employment, food safety, public health, and primary/middle school education. Respondents were asked to evaluate government performance in these policy domains on a scale from 1 (very good) to 10 (very bad). Higher scores indicate greater levels of dissatisfaction. Government policy performance was the country-specific items that were designed by the Chinese survey team.

Information access, family economic situation, party membership, and political efficacy are relevant to people’s attitudes towards governments. Hence, they were controlled for in the regression analyses. Information access was measured by two different types of information sources: the Internet and mass media. Internet use evaluates how frequently respondents use the Internet. Responses were coded on a nine-point scale from 1 (never) to 9 (several hours a day). The variable of mass media was measured by asking respondents the frequency of their following mass media news on a six-point scale from 1 (never) to 6 (several times a day). Family economic situation was evaluated by respondents’ household economic situation. The answers were coded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good). Higher scores indicate a better economic situation. Party membership was measured by party affiliation with the Chinese Communist Party on a dummy scale, with 0 indicating “not a member” and 1 indicating being a communist party member. Political efficacy reflects ordinary people’s confidence in their capability to understand and participate in politics. Political efficacy was measured by asking respondents to what degree they agreed with the following statements on a four-point scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree): “People like me do not have any influence over what the government does.” The higher scores indicate a greater level of political efficacy.

Age, gender, education, and residence were controlled in the regression analyses. Age and education were two continuous variables. Education was measured in years of schooling. Gender was coded on a dummy scale, with 0 indicating male and 1 indicating female. Residence was measured by a rural–city binary variable (rural), with 0 indicating living in the city and 1 indicating living in a rural area.

Table A1 shows an overview of descriptive statistics of variables.

Results

Based on the analytical framework presented in Figure 1, we first analyse evaluations of government policy performance based on the attribution of administrative responsibility between the central and local governments. Next, we analyse the varying effects of evaluations of government policy performance on political trust at the central and local levels. The results demonstrate how the perceived administrative responsibility of the two government levels affects political trust.

Evaluations of government policy performance based on attribution of administrative responsibility between local and central governments

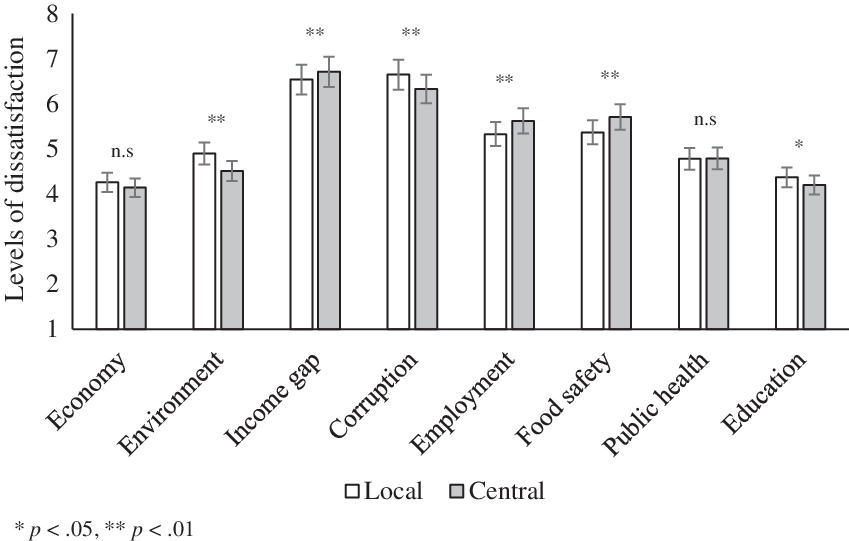

The multilevel government system divides administrative responsibility between local and central governments. Public evaluation of government policy performance may vary, based on differences in attribution of responsibility to either the local or central government. Therefore, we examined differences in public evaluation of government performance between people who attributed major responsibility to local governments, and those who attributed responsibility to the central government (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Public dissatisfaction with government policy performance in China.

First, the public’s evaluation of government performance varies in line with their attribution of responsibility to different levels of government. We performed a t-test, and the results showed that there was a significant gap in public evaluations of government performance in multiple fields; namely, environmental protection, income inequalities, corruption, employment, food safety, and primary/middle school education. This gap was most pronounced between those who attributed major responsibility to local governments and those who attributed responsibility to the central government. The results indicate that citizens separate administrative responsibility at the central and local levels and evaluate government policy performance based on the perceived administrative responsibility of the two levels of government.

Second, people who attributed major responsibility to local governments tended to have high levels of dissatisfaction with government performance in a) environmental protection; b) corruption; and c) primary/middle school education. These percentages were greater than in their counterparts who attributed major responsibility to the central government. Interestingly, while most Chinese people believed the control of corruption was the central government’s responsibility, they were more satisfied with the status of corruption than those who attributed responsibility to local governments. The latter were the minority, yet they had higher levels of dissatisfaction with the government’s ineffectiveness at controlling corruption. Figure 3 indicates that local governments are under greater pressure due to public discontent with their poor performance in environmental protection, corruption, and primary/middle school education.

Third, people who attributed major responsibility to the central government tended to have higher levels of dissatisfaction with government performance in the fields of income equalities, employment, and food safety than their counterparts who attributed responsibility to local governments. Although income gaps, employment, and food safety involve the joint administrative responsibility of both the central and local governments, poor performance in these public policies generates more negative impacts on the central government. Those who attributed responsibility to the central government were more dissatisfied with government performance in these policy domains. The results indicate that these people were more critical of the central government regarding income inequalities, employment, and food safety.

The effects of government policy performance on political trust

The Chinese public’s dissatisfaction with government policy performance may erode political trust in the government. However, it was unclear whether varying policy performance has identical or differentiated effects on public trust in the local and central governments. Table 1 shows the effects of government policy performance in different domains on public trust in both local and central governments. First, political corruption particularly eroded public trust in local governments, while its effect on the central government was insignificant. Second, dissatisfaction with economic growth eroded public trust in the central government, while their negative effects on the local government were not significant. Third, government policy performance in the fields of environmental protection, food safety problems, public health, and primary/middle school education undermined public trust in both local and central governments.

Table 1. Public trust in the local and central governments

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, two-tailed test.

These results have important political implications. By taking the multilevel government system into consideration, this study identified differentiated effects of government policy performance on public trust in local and central governments. Previous studies identified the destructive effects of corruption on political trust (Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Catterberg and Moreno, Reference Catterberg and Moreno2005; Chang and Chu Reference Chang and Chu2006). Our study proves that corruption indeed undermines political trust, but to a large extent this negative effect was confined to local governments. As Saich (Reference Saich2011) stated, Chinese citizens view the problem as arising from “poor implementation at the local level or the incompetence or venality of local officials.” The empirical evidence did not show that public dissatisfaction with corruption significantly reduced political trust in the central government. Results indicate an interesting aspect of the Chinese people’s political psychology. On the one hand, they attributed major responsibility for suppressing corruption to the central government. On the other hand, their dissatisfaction with the state of corruption did not significantly undermine trust in the central government; rather, it reduced trust in the local government. Such mass psychology reflects that the Chinese public actually views corruption as a problem of local governments. Ordinary people tended to believe that the central government is benevolent and responsible, expecting it to control and punish corrupt officials in local governments.

Even though the central government attempted to shift responsibility to local governments, the outcomes did not develop as the central government expected. Public concerns about environmental protection, food safety problems, public health, and primary/middle school education undermine public trust in the central and local governments. Thus, the central government must develop an understanding of the political implications posed by these social issues. In addition, poor performance in the fields of economy particularly undermined public trust in the central government. The political implication of this attribution is that slowing economic growth will damage public trust in the central government. In the Chinese people’s eyes, slowing economic growth indicates incapability of the central government to promote economic development, and the citizens become concerned about their worsening personal prospects.

The effects of government policy performance on central–local political trust patterns

Government policy performance affects the public’s trust in the central and local governments. At the same time, it may have a distinct association with central–local political trust patterns. As previously stated, central–local political trust has three patterns: parallel trust, pyramidal trust, and hierarchical trust. Hierarchical trust is the most prevalent in China (see Figure 2). We further examined how government performance in various policy domains affects the Chinese public’s central–local political trust patterns. Table 2 presents the findings.

Table 2. Multinomial logistic regression of hierarchical, pyramidal, and parallel trust

Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, two-tailed test.

Setting parallel trust (i.e. levels of trust in the local and central governments are equal) as a reference baseline, people who were dissatisfied with government performance regarding food safety adhered to a pattern of pyramidal trust (i.e. trust in local governments was higher than in the central government). People who were dissatisfied with corruption and primary/middle school education tended to have a pattern of hierarchical trust (i.e. trust in the central government was higher than in local governments).

Relationships between government performance in various policy domains and central–local political trust patterns provide further explanations for the results presented in previous sections. Dissatisfaction with government performance regarding food safety was positively correlated with pyramidal trust. As previously stated, such a pattern of political trust is rare in China. Food safety problems have drawn increasing public attention, and Chinese citizens have developed high levels of dissatisfaction with government performance in this field. Thus, public dissatisfaction with food safety problems will likely promote an increase in the pyramidal trust pattern. Such a shifting pattern indicates that the central government is at risk of further losing public trust. In addition, political corruption was positively correlated with the pattern of hierarchical trust. This finding is consistent with the results in Table 1, which shows that corruption contributes to declining public trust in local governments, rather than in the central government. The Chinese public has greater trust in the central government, expecting it to curb corruption. Dissatisfaction with government performance in the field of primary/middle school education was also positively correlated with hierarchical trust. The people’s high level of trust in the central government means that they also expect it to improve education.

Discussion and conclusions

Using the latest national survey data, this study examined the Chinese public’s central–local political trust. The multilevel government system separates administrative responsibility for public policy issues between the central and local governments. Hence, citizens attribute major responsibilities of government performance to different levels of government. This study analysed how the perceived administrative responsibility of the two levels of government affects citizens’ evaluations of various government policy performances and their political trust. The results identified the fields in which the Chinese public was least content with government policy performance: the income gap, corruption, food safety, and employment. Clearly, these problems were not only economy related but also involved social and political fields. An economy-centred perspective limits understanding of the Chinese public’s evaluation of government performance. In particular, in the fields of enlarging income inequality and rampant corruption, the Chinese public had high levels of dissatisfaction with government performance. Even though the government has adopted some redistribution policies to curb the increasing income gap (and Gini coefficients also show a downward trend), the public remains dissatisfied with the current situation. The Xi administration launched high-profile anticorruption campaigns, expecting to obtain public support. However, evidence shows that the public still maintains a high level of dissatisfaction with the state of corruption in China’s politics.

The perceived administrative responsibility of different levels of government affects evaluations of government policy performance. Citizens who attributed administrative responsibility to the local government were highly dissatisfied with policy performance in the fields of environmental protection, political corruption, and education. Contrastingly, those who attributed administrative responsibility to the central government were highly dissatisfied with the policy domains of income inequalities, employment, and food safety. These findings imply that governments at the central and local levels face public discontent according to different policy issues. Citizens have differentiated the perception of administrative responsibility for various public policies between the two levels of government. Therefore, the central and local governments should have different emphases on improving public policy to obtain citizens’ approval.

As the perceived administrative responsibility of different levels of government varies, evaluations of government policy performance in various policy domains had differing effects on political trust at the local and central levels. Local governments particularly lost trust for public dissatisfaction with corruption, while the central government lost trust for less satisfying performance in the fields of economy. Public dissatisfaction with government performance regarding environmental protection, food safety, public health, and primary/middle school education eroded trust in both local and central governments. The results indicate that performance in certain policy domains affected political trust in only the local or central government, while government performance in other domains affected both. Moreover, this study examined the relationships between government performance in various policy domains, and central–local political trust patterns in China. As previously stated, we analysed three patterns of political trust (parallel, pyramidal, and hierarchical), based on the relationships between local and central governments. Setting the pattern of parallel trust as a reference baseline, the public’s dissatisfaction with food safety tended to facilitate pyramidal trust, while dissatisfaction with corruption and primary/middle school education tended to increase hierarchical trust. The results indicate that government performance in various policy domains affects not only public trust in the local and central governments but also affects the Chinese public’s central–local political trust patterns.

The empirical evidence helps us understand complex relationships between government policy performance and political trust in different levels of government in authoritarian China. The findings observed in China may differ from those in democracies. The top-down economic policy and the local implementation explain why economic performance affects trust in the national government. In addition, state-owned media always blames local implementation, which ensures that the blame does not go up to the national level. Therefore, corruption primarily undermines trust in local governments. In democracies, however, national governments do not have the political power to transfer blame to local governments and maintain trust in the national government at the cost of local governments.

Furthermore, the findings show that local governments in China are under extraordinary pressure. The pressure lies in worsening budgetary conditions (Smith Reference Smith2010; Chung Reference Chung2016). Additionally, a majority of the Chinese public tends to attribute responsibility in most policy domains to local governments. In the authoritarian unitary government system, the central government exerts dominant power in central–local relations. Its purview ranges from the appointment of officials, to distribution of public funding, and the evaluation of local governments’ performances. However, the central government retains a majority of public finance, leaving limited resources to local governments. As a result, local governments have a variety of work to do, but lack sufficient financial resources. Moreover, the CCP attempts to prevent public discontent with the central government, which could threaten its authoritarian rule. The CCP shifts responsibility to local governments, placing them on the front line to confront public discontent. As a result, the Chinese public attributes responsibility for a majority of policy domains to local governments, and blames them for unsatisfying performance.

The well-known Chinese exceptionalism in central–local political trust patterns (i.e. hierarchical trust) is associated with government policy performance, which has been overlooked by previous studies. We found relationships between government performance in various policy domains and central–local political trust patterns in China. Corruption contributes to facilitating hierarchical trust (see Table 2). Corruption has caused widespread public discontent, and is seen as posing a threat to the legitimacy of the CCP’s rule. However, negative effects of corruption on public trust in government were observed only at the local level (see Table 1). Previous studies state that the Chinese tended to attribute corruption only to local officials (Saich Reference Saich2016). In Chinese political culture, political leaders in Beijing are always benevolent whereas local officials cheat the formers and do not faithfully implement beneficial policies drafted by the central government. Most corrupted officials prosecuted in the anticorruption campaign operated at the local level, which generates an impression according to which political corruption was a predominantly local phenomenon. Moreover, the central government displays a resolution of eradicating corruption and performs as a protector of the people. Therefore, corruption undermined trust in the local government, but did not have a significant effect on public trust in the central government. It is worth noting that corruption assists in facilitating hierarchical trust. Such a tendency is more favorable to the central government. In other words, the central government benefits by maintaining a certain degree of public dissatisfaction with corruption. The reason for this is that continual uncovering of corruption cases draws public attention to poor political performance at local levels, thereby presenting an image of the central authority’s anticorruption efforts as just and fair. Local government corruption cases induce ordinary Chinese people to believe that the central government plays an indispensable role in curbing corruption. As a result, dissatisfaction with corruption breeds hierarchical trust.

However, this study shows that the central government cannot always avoid blame and risks losing public trust. Although the central government attempts to manipulate the public’s perception of administrative responsibility on different levels of government, there were some unintended outcomes for the central government. Regarding performance in economy, environmental protection, food safety, public health, and education, poor performance in these domains eroded public trust in the central government. The results imply that the interactive effects of policy performance on public trust between the central and local levels of government. Local governments’ incompetence and wrongdoing also weaken the central regime’s legitimacy (Chen Reference Chen2017). Even though more central control does not necessarily guarantee improved policy outcomes (Kostka and Nahm Reference Kostka and Nahm2017), the results help explain the recent move toward recentralisation of environmental governance and food safety regulation.

Moreover, slowing economic growth particularly damages trust in the central government. Our study found that public dissatisfaction with the country’s economic growth suppressed the tendency to trust the government at the central level, and this negative effect was not observed on local governments. Although Chinese people generally trust the central government more than local governments, slowing economic growth will lead ordinary people to withdraw their trust in the central government. This is the most undesirable outcome for the CCP leadership, because losing public trust in the central government directly threatens its rule. Decelerating economic growth has lasted more than a decade, and the recent Sino-USA trade war is further worsening China’s economy. A continuous trend of slowing economic growth will contribute to a foreseeable decline in trust in the central government.

Regarding central–local political trust patterns, it is also premature to argue that the CCP has gained ascendency in manipulating the public’s trust in the government. This study sheds light on the fragility of hierarchical trust. Public dissatisfaction with the food safety situation promotes the pyramidal trust pattern (i.e. trust in local governments is higher than in the central government). Food safety problems have been most salient in recent years. Numerous horrifying food safety incidents have been disclosed, enraging the public. Food safety problems have transcended the scope of public health and have far-reaching social and political influence. As the Chinese public has shifted attention from basic economic security to quality-of-life issues, the central government risks losing public trust for rampant food safety problems. In such situations, the public will no longer trust the central government more than local governments.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HQCQWX

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article.

Financial support

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) through grant ref: 71874109.

Conflict of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1. Descriptive statistics