Introduction

Iatrogenic damage to the chorda tympani is a well recognised complication of middle-ear surgery.Reference Clark and O'Malley1 The overall reported prevalence of related symptoms after such surgery is between 15 and 22 per cent,Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3 although chorda tympani injury occurs more often. The consequences of injury are variable, prognosis is difficult to predict, and prevention is sometimes controversial.

This article follows on from a systematic review of the clinical anatomy of the chorda tympani (see below), and aims to summarise our current knowledge about iatrogenic injury to the chorda tympani and the implications for clinical practice.

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was undertaken using the electronic databases Medline, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library and the search engine Google Scholar. English language and human studies were selected using the search term ‘chorda tympani’ and its subheadings, focusing on articles relevant to iatrogenic injury. Secondary references were retrieved from primary sources, and animal data included where relevant.

Results

These are best considered as a series of clinical questions, as follows.

Where and when does chorda tympani injury occur?

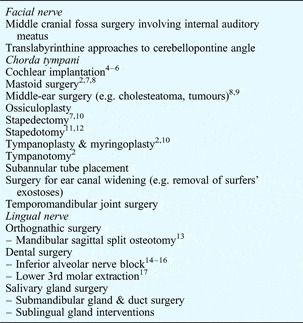

The lengthy course of the chorda tympani exposes it to the risk of injury in a variety of surgical procedures (Table I), most commonly during middle-ear surgery. The frequency of injury is difficult to determine and depends on the surgical procedure and technique, underlying pathology, and method and timing of detection. In one study of 107 patients undergoing middle-ear surgery for chronic otitis media, the chorda tympani was inadvertently divided in 20 (19 per cent) cases.Reference Lloyd, Meerton, Di Cuffa, Lavy and Graham4

How is the chorda tympani injured?

The chorda tympani may be injured by a variety of mechanisms including transection, stretching, ischaemia, thermal injury, excessive handling and desiccation. Nerve transection may be accidental or deliberate. Stretching is a common mechanism,Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19 such as when raising a tympano-meatal flap during myringoplasty.Reference Yeo and Loy10 Animal studies have shown that the intraneural microcirculation is interrupted when nerves are stretched by 15 per cent or more of their resting length.Reference Lundborg and Rydevik20 Various authors have reported thermal injury from bone drillingReference Yeo and Loy10 or diathermy, and drying from the microscope heat or overhead lightsReference Clark and O'Malley1, Reference Bull7 or from prolonged exposure without moistening.Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3, Reference Rice21

What are the effects of chorda tympani injury?

The classic features of chorda tympani injury are loss or alteration of taste with or without dryness of the mouth, both of which are related to the main functions of the nerve. In one study of 140 middle-ear operations, 15 per cent of patients reported post-operative taste disturbances: 71 per cent had altered taste, 29 per cent had loss of taste, and 19 per cent had concomitant dryness of the mouth.Reference Michael and Raut2 Several authors have also described somatosensory symptoms such as numbness and tinglingReference Bull7, Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19, Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22–Reference Perez, Fuoco, Dorion, Ho and Chen26 and post-operative touch-evoked dysgeusia,Reference Chen, Bodmer, Khetani and Lin27 following chorda tympani damage.

Injury to the chorda tympani does not necessarily cause symptoms. Some patients are asymptomatic, whilst others can have transient or permanent symptoms.Reference Clark and O'Malley1–Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3 Numerous factors influence which of these three outcomes occurs, the most important being whether the chorda tympani has been sectioned or is grossly intact.Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3, Reference Yeo and Loy10, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19, Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22, Reference Chilla, Bruner and Arglebe28–Reference Sone, Sakagami, Tsuji and Mishiro30 Others include the type of surgery,Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Gopalan, Kumar, Gupta and Phillipps31 the age of the patient,Reference Sone, Sakagami, Tsuji and Mishiro30, Reference Terada, Sone, Tsuji, Mishiro and Sakagami32 whether the injury is unilateral or bilateral,Reference Bull7, Reference Catalanotto, Bartoshuk, Ostrom, Gent and Fast33 and the underlying disease.Reference Clark and O'Malley1, Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Griffith9, Reference Terada, Sone, Tsuji, Mishiro and Sakagami32, Reference Sakagami, Sone, Tsuji, Fukazawa and Mishiro34

Anatomical variables are also likely to affect the outcome, i.e.: the extent to which inhibition of other taste nerves is released after chorda tympani injury;Reference Catalanotto, Bartoshuk, Ostrom, Gent and Fast33, Reference Kveton and Bartoshuk35, Reference Lehman, Bartoshuk, Catalanotto, Kveton and Lowlicht36 the extent of regeneration of the ipsilateral chorda tympani;Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19, Reference Saito, Shibamori, Manabe, Yamagishi, Igawa and Ohtsubo37 and the degree of reinnervation by the chorda tympani or glossopharyngeal nerve.Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22, Reference Chilla, Nicklatsch and Arglebe29, Reference Tomita, Ikeda and Okuda38 In addition, there is a variable subjective adjustment to taste impairment.Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22, Reference Chilla, Nicklatsch and Arglebe29

Specific symptoms, and their prevalence and prognosis, will now be discussed.

Taste

Changes in taste can be categorised as dysgeusia, a ‘perversion of the sense of taste’ or, less commonly, as ageusia, a ‘lack or impairment of the sense of taste’.Reference Yeo and Loy10 Chorda tympani injury most often causes dysgeusia, which typically manifests as an intermittent metallic taste on the side of the tongue ipsilateral to the injury, but which may be sensed all over the tongue or confined to its tip.Reference Clark and O'Malley1, Reference Bull7 Loss of appetite may be a consequence.Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11 Dysgeusia can also manifest as increased saltiness or decreased sweetness perception,Reference Yeo and Loy10, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19 or as taste disturbance with specific foods only (particularly tea and coffee).Reference Bull7 Ageusia affecting the ipsilateral side of the tongue most often occurs after unilateral transection of the chorda tympani,Reference Bull7 although the patient may find it difficult to accurately localise the taste impairment.Reference Rice21 The surface of the denervated side of the tongue becomes smooth and pale, with associated atrophy of the fungiform papillae.Reference Bull7, Reference Just, Gafumbegete, Kleinschmidt and Pau39, Reference Negoro, Umetmoto, Fukazawa and Sakagami40 Rarely, patients complain that food is only tasted when it reaches the back of the tongue just before swallowing.Reference Bull7

In a small sample of 20 patients, Yeo and LoyReference Yeo and Loy10 found that post-operative dysgeusia was associated with a much higher incidence of permanent taste disturbance, compared with ageusia.

Various factors influence the development of gustatory symptoms, as follows.

Nerve transection versus lesser injury

Opinion is divided on whether the chorda tympani should be preserved or cleanly divided if it is injuredReference Yeo and Loy10 or mobilised (e.g. whilst obtaining surgical access to the oval window). In the past, most surgeons elected to leave the nerve intact in cases of suspected injury.Reference Wiet, Harvey and Bauer41 Of seven studies that have assessed this question, four advocated preservation of the chorda tympani,Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3, Reference Yeo and Loy10, Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11, Reference Moon and Pullen24 two advocated section of the nerve,Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Lloyd, Meerton, Di Cuffa, Lavy and Graham4 and one concluded that there was little difference between these two options.Reference Rice21 Recent evidence shows that between 16 and 73 per cent of patients report subjective disturbances of taste after ear surgery in which the chorda tympani has been manipulated,Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22, Reference Gopalan, Kumar, Gupta and Phillipps31 and that these symptoms persist in 3 to 29 per cent of cases.Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3, Reference Lloyd, Meerton, Di Cuffa, Lavy and Graham4 After the chorda tympani has been severed, 10–95 per cent of patients report symptoms,Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11 which persist in 0–50 per cent.Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11, Reference Gopalan, Kumar, Gupta and Phillipps31 This wide range of outcomes is due in part to the distorting effects of small studies on the data, and also to the differing intervals after which symptom persistence is defined; the true incidence is likely to be towards the lower end of these ranges (Tables II and III). Overall, the majority of studies show that section of the chorda tympani is more likely to lead to post-operative gustatory symptoms, and these symptoms are more likely to persist, than if the nerve is preserved. For example, one study of 55 patients recorded a mean symptom duration of 6.7 months in patients in whom the chorda tympani had been sectioned, compared with 3.4 months in patients in whom it had been preserved.Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11

Table II Subjective gustatory symptoms after middle-ear surgery with chorda tympani preservation

Post-op = post-operative; pts = patients; HL = hearing loss; mth=months; CT = chorda tympani; y = years; NS = not specified

Table III Subjective gustatory symptoms after middle-ear surgery with chorda tympani transection

Pts = patients; y = years; mth = months; NS = not specified

The severity of chorda tympani manipulation also affects the prevalence of symptoms. Mueller et al. Reference Mueller, Khatib, Naka, Temmel and Hummel25 reported that taste function was impaired in 47 per cent of patients after minor manipulation of the nerve, compared with 56 per cent of patients after major manipulation. Gopalan et al. Reference Gopalan, Kumar, Gupta and Phillipps31 reported similar findings: 7 per cent of patients developed symptoms following handling of the chorda tympani, and 28 per cent after stretching of the nerve. Chorda tympani damage may be so minor as to go unnoticed.Reference Lloyd, Meerton, Di Cuffa, Lavy and Graham4 Thus, Saito et al. Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3 found that 2.8 per cent of patients developed symptoms when the chorda tympani had not knowingly been touched.

Type of surgery

The type of middle-ear procedure appears to affect the frequency of chorda tympani damage and therefore the incidence of post-operative taste disturbance.Reference Michael and Raut2 In one study of 140 patients undergoing middle-ear operations,Reference Michael and Raut2 subjective taste disturbance was recorded in 45 per cent after tympanotomy, 11 per cent after myringoplasty and 2 per cent after mastoidectomy. Whilst three-quarters of patients had recovered within one year, the duration of symptoms was longest in the tympanotomy group. In another study of 93 patients, Gopalan et al. Reference Gopalan, Kumar, Gupta and Phillipps31 found chorda tympani related symptoms in 57 per cent after tympanotomy, 6.5 per cent after myringoplasty and 15 per cent after mastoidectomy; again, functional recovery was slower in the tympanotomy group. Both authors commented that the high incidence of gustatory symptoms after tympanotomy may be due to the chorda tympani being previously unaffected by disease in these cases; therefore, a change in function would be more noticeable.

Patient age

Sone et al. Reference Sone, Sakagami, Tsuji and Mishiro30 found that recovery of electrogustometry thresholds six months after middle-ear surgery with preservation of the chorda tympani was significantly more likely in patients aged 20 years or younger, compared with older patients. This is consistent with the observation that electrogustometry thresholds increase with advancing age.Reference Terada, Sone, Tsuji, Mishiro and Sakagami32 This deterioration in taste function with age prompted Terada et al. Reference Terada, Sone, Tsuji, Mishiro and Sakagami32 to suggest that less attention needs to be paid to the chorda tympani during middle-ear surgery in patients over the age of 60 years.

Underlying disease

In its path across the tympanic membrane, the chorda tympani may be directly affected by middle-ear diseases such as cholesteatoma or chronic otitis media,Reference Clark and O'Malley1, Reference Hansen, Anthonsen, Strangerup, Jensen, Thomsen and Caye-Thomasen5, Reference Gedikli, Dogru, Aydin, Tuz, Uygur and Sari18 as shown by histological changes in the nerve.Reference Gedikli, Dogru, Aydin, Tuz, Uygur and Sari18 In such cases, iatrogenic nerve injury causes less post-operative taste disturbance than that caused (at least short term) by surgery for a non-inflammatory condition (Table IV).Reference Clark and O'Malley1, Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Sakagami, Sone, Tsuji, Fukazawa and Mishiro34 Electrogustometric assessment in patients with a cholesteatoma has shown pre-operative threshold elevations of approximately 45 per cent.Reference Yaginuma, Kobayashi, Sai and Takasaka42 Studies in patients with chronic otitis media indicate that inflammation and advancing age have additive detrimental effects on electrogustometry thresholds.Reference Terada, Sone, Tsuji, Mishiro and Sakagami32

Table IV Subjective post-operative gustatory symptoms by underlying pathology

Pts = patients; post-op = post-operative; CT = chorda tympani; mth = months; wk = weeks; COM + perf = chronic otitis media with perforation

Inhibition of other taste nerves

Damage to the chorda tympani is understood to release inhibiting influences on other taste nerves, which tends to compensate for any taste deficiency.Reference Catalanotto, Bartoshuk, Ostrom, Gent and Fast33, Reference Kveton and Bartoshuk35 Thus, unilateral anaesthesia of the chorda tympani enhances the response to taste stimulation in areas of the tongue innervated by the ipsilateral glossopharyngeal nerve.Reference Catalanotto, Bartoshuk, Ostrom, Gent and Fast33, Reference Lehman, Bartoshuk, Catalanotto, Kveton and Lowlicht36 This may be one explanation for why some individuals experience no taste disturbance even after bilateral chorda tympani injury.Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19

Regeneration and reinnervation

Saito et al. Reference Saito, Shibamori, Manabe, Yamagishi, Igawa and Ohtsubo37 found evidence of regeneration of the chorda tympani in 42 per cent of 52 patients undergoing reoperative middle-ear surgery 11 to 65 months after chorda tympani transection. Regeneration was present in all five patients who had originally undergone end-to-end nerve repair, but in only 17 of 47 patients (36 per cent) in whom a nerve gap defect had been present; recovery of electrogustometry thresholds occurred in more than 70 per cent of cases with regeneration. Evidence of nerve regeneration was more likely in children; this is in keeping with the higher recovery rates seen in younger patients.Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19

Recovery of taste may be the result of reinnervation of taste buds by the contralateral or ipsilateral chorda tympani or glossopharyngeal nerve. Whilst chorda tympani regeneration has been documented in experimental animals,Reference Guagliardo and Hill43 little is known about its extent in humans.

Subjective adjustment to taste impairment

Patients with a permanent taste disturbance may to a variable extent adapt to this dysfunction over time, and either stop noticing the deficit or stop complainingReference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22, Reference Chilla, Nicklatsch and Arglebe29 (although one patient still reported symptoms 21 years after chorda tympani transection).Reference Bull7 This is supported by observations that the recovery of electrogustometry taste threshold is slower than that of subjective taste,Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19, Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22, Reference Miuchi, Sakagami, Tsuzuki, Noguchi, Mishiro and Katsura23 and the fact that the chorda tympani supplies only 15 per cent of all taste buds.Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22 Recovery is probably also influenced by the extent to which alternative taste pathways, such as the greater superficial petrosal nerve, are recruited.Reference Rice21

In most cases of unilateral chorda tympani injury, taste symptoms are not particularly troublesome, particularly in the context of successful middle-ear surgery.Reference Bull7 This is illustrated by one patient's remark, after successful stapedectomy: ‘I would rather hear than taste normally’.Reference Bull7 It is the small proportion of cases in which symptoms persist or impact on the patient's occupation (e.g. in the case of a professional chef) that cause most distress.Reference Bull7, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19 Symptoms of taste disturbance after bilateral chorda tympani injury are similar to those following unilateral damage, but may be more pronounced.Reference Bull7

Salivation

Unilateral chorda tympani injury can reduce basal salivation such that the patient notices a dry mouth. Indeed, transtympanic chorda tympani ablation was previously used to control sialorrhoea in patients with neurological handicap. As with disturbances of taste, outcome is variable and dependent on several factors.

Nerve transection versus lesser injury

Chilla et al. Reference Chilla, Bruner and Arglebe28 found that ipsilateral submandibular gland salivary flow was significantly decreased after chorda tympani injury, but not enough to cause symptoms. When the patients were retested four years later, submandibular salivary flow remained diminished, but only in those whose chorda tympani had been divided.Reference Chilla, Nicklatsch and Arglebe29

Unilateral versus bilateral injury

In a large study of 126 patients in whom the chorda tympani was deliberately divided during unilateral middle-ear surgery, 30 per cent reported a dry mouth, which in most was persistent for more than a year.Reference Bull7 However, symptoms were typically mild. After bilateral transection, dryness of the mouth was marked in 50 per cent of patients, tended to be persistent, and was described as ‘very annoying’ but not severely distressing.Reference Bull7

Two studies have investigated the long term effects of unilateral chorda tympani injury on target salivary glands. The first used ultrasound imaging, and found that the volume of the denervated submandibular gland was significantly smaller, compared with the contralateral gland, one year later.Reference Miman, Sigirci, Ozturan, Karatas and Erdem44 However, this was because the contralateral gland was larger than in healthy controls (i.e. it had hypertrophied), rather than the ipsilateral gland being smaller. In the second study, the ability of the denervated gland to take up, concentrate and secrete radioisotope was significantly reduced.Reference Yagmur, Miman, Karatas, Akarcay and Erdem45 Therefore, it seems that unilateral chorda tympani damage impairs the function of the ipsilateral submandibular salivary gland but does not cause atrophy.Reference Yagmur, Miman, Karatas, Akarcay and Erdem45

Despite these measurable changes, in most cases of unilateral transection any effect on salivation is subclinical.Reference Yeo and Loy10, Reference Chilla, Bruner and Arglebe28 Paradoxically, one study documented a few patients who reported a subjective increase in salivation after unilateral chorda tympani injury.Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22 Bilateral chorda tympani transection reduces salivary flow more significantly, but some recovery is possible.Reference Yeo and Loy10 Chorda tympani transection was previously used as a treatment for disabling sialorrhoea.Reference Miman, Sigirci, Ozturan, Karatas and Erdem44 However, this procedure became redundant following the realisation that drooling was not so much a problem of hypersalivation but related more to neuromuscular incoordination,Reference Meningaud, Pitak-Arnnop, Chikhani and Bertrand46 and following demonstration of the efficacy of botulinum toxin therapy.Reference Benson and Daugherty47

General sensory symptoms

Alterations in general lingual sensation after chorda tympani injury are comparatively uncommon, but include tingling, numbness, burning or a sensation of anaesthesia.Reference Bull7, Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19, Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22–Reference Perez, Fuoco, Dorion, Ho and Chen26, Reference Sone, Sakagami, Tsuji and Mishiro30 The incidence of these symptoms is very variable, ranging from 3 per cent (in one large study of 126 patients after unilateral chorda tympani transection)Reference Bull7 to 46 per cent (in other studies).Reference Perez, Fuoco, Dorion, Ho and Chen26 Tongue numbness was specifically recorded in 42 per cent of 67 patients in whom the chorda tympani was preserved during middle-ear surgery, and in 16 per cent of 37 patients in whom it was sectioned; in most cases this symptom resolved within six months.Reference Sone, Sakagami, Tsuji and Mishiro30

The pathogenesis of general sensory symptoms has been reviewed elsewhere (see our chorda tympani clinical anatomy review).Reference McManus, Dawes and Stringer48

Tactile dysgeusia

Chen et al. Reference Chen, Bodmer, Khetani and Lin27 described persistent post-operative dysgeusia evoked by touch in seven patients with chorda tympani injury complicating middle-ear surgery. Application of a cotton-tip to the ventral aspect of the pinna and tragus and the posterolateral aspect of the external auditory canal resulted in dysgeusia limited to the ipsilateral side of the tongue. The authors attributed this phenomenon to aberrant reinnervation of taste fibres within the injured chorda tympani by somatosensory fibres. The gradual onset of tactile dysgeusia (three weeks to eight months) supports this hypothesis. Only one of the patients reported the symptom as ‘frequently annoying’.

What steps can be taken to prevent iatrogenic chorda tympani injury?

A good understanding of normal and variant chorda tympani anatomy may help to avoid some instances of iatrogenic injury.

If the chorda tympani is encountered, preservation of the nerve appears preferable to transection, in terms of the frequency and persistence of resultant symptoms. BullReference Bull7 found that, overall, 51 per cent of patients whose chorda tympani had been preserved at stapes surgery had related symptoms, and that these symptoms were still present one year later in 7 per cent. Of the 126 patients whose chorda tympani had been sectioned at stapes surgery, 80 per cent were symptomatic and 32 per cent had persistent complaints.

Avoiding diathermy injury, desiccation and excessive handling of the nerve are general prophylactic measures. Other preventive strategies have been discussed in relation to specific procedures or approaches, namely cochlear implantation,Reference Kronenberg and Migirov49, Reference Taibah50 stapes surgeryReference Wiet, Harvey and Bauer41 and tympanotomy.Reference Bull7 In the case of bilateral surgery, several authors have recommended pre-operative taste testing, and waiting for the electrogustometry threshold to be restored to normal on the operated side prior to operating on the contralateral ear.Reference Miuchi, Sakagami, Tsuzuki, Noguchi, Mishiro and Katsura23, Reference Mueller, Khatib, Naka, Temmel and Hummel25

Comment

Despite a reasonable body of literature on iatrogenic chorda tympani injury, meaningful comparison between studies is difficult because they differ in their aims, patient characteristics, sample size and methodologies. Some have relied on subjective taste disturbance whilst others have focused on objective measures such as electrogustometry, yet the correlation between these two outcome measures is not good.Reference Yeo and Loy10, Reference Mahendran, Hogg and Robinson11 Unsurprisingly, subjective taste disturbance resolves more rapidly than the electrogustometry taste threshold.Reference Saito, Manabe, Shibamori, Yamagishi, Igawa and Tokuriki3, Reference Nin, Sakagami, Sone-Okunaka, Muto, Mishiro and Fukazawa19, Reference Berteretche, Eloit, Dumas, Talmain, Herman and Tran Ba Huy22

These are not the only reasons why it is difficult to determine the true prevalence of taste symptoms after chorda tympani injury. It is likely that patients do not associate taste with an ear operation,Reference Bull7 especially if the primary goal of surgery (e.g. improved hearing) has been achieved.Reference Clark and O'Malley1 Therefore, taste disturbance may be under-reported.Reference Hansen, Anthonsen, Strangerup, Jensen, Thomsen and Caye-Thomasen5, Reference Bull7 Gopalan et al. Reference Gopalan, Kumar, Gupta and Phillipps31 found nearly half of the symptomatic patients in their study were unaware of their symptoms until asked specifically.

From a medicolegal perspective, it remains debatable whether taste should be tested routinely prior to middle-ear surgery.Reference Landis and Hummel51 However, patients should be warned of possible taste disturbance as a complication of surgery. In a survey of British otorhinolaryngology surgeons reported in 2003, nearly half did not routinely discuss chorda tympani injury and taste impairment as a possible complication of myringoplasty or tympanoplasty.Reference Saravanappa, Balfour and Bowdler52 This is similar to the proportion of patients advised about this complication of ossiculoplasty, reported five years earlier.Reference Dawes and Kitcher53 Instead, consent tends to focus on the more important otological, intracranial and facial nerve complications.Reference Michael and Raut2

Conclusion

The diversity of chorda tympani functions, and the range of factors modifying the response to injury, results in a broad and variable spectrum of symptoms following iatrogenic injury. However, complaints are sufficiently common, troublesome and, in some cases, persistent to merit care being taken to preserve the chorda tympani in middle-ear surgery and to warn patients pre-operatively about this potential complication.Reference Michael and Raut2, Reference Mueller, Khatib, Naka, Temmel and Hummel25 This is particularly important if surgery is bilateral. Chorda tympani transection is more likely to cause sequelae than injury to an intact nerve.

Acknowledgement

Lauren J McManus was funded by a University of Otago Faculty of Medicine scholarship.