Introduction

The October 5, 1946 cover of the Saturday Evening Post features an image by Norman Rockwell, the popular mid-century artist and illustrator. It depicts Willie Gillis Jr., Rockwell's fictional everyman American soldier. The Post introduced Willie to its readers at the start of World War II with an illustration of Willie entering the war as a private. He would grace the cover of the magazine nine more times before being pictured finally, in this image, at war's end.

Willie is in college, studying, perched a bit awkwardly in a dorm room window—his military-issued helmet and bayonet hanging over head—looking out over a leafy campus. This image of transition into higher education would strike many modern viewers as a fitting and familiar close to the average GI's story: A veteran returns from war and makes use of the GI Bill to pursue the American Dream.

The general arc of this story has become widely understood as a quintessential twentieth-century American phenomenon: the use of college education as a means of upward mobility; the federal government using its fiscal might to expand college access; and the development of mutually beneficial compacts between universities and government agencies. Yet published accounts of this story are without a crucial and revealing chapter about the complex administrative work required to transform enlisted soldiers into qualified college students.

While prior accounts of the GI Bill present this transition as an inevitable consequence of the bill's passage, upon closer scrutiny the logistics of its implementation were no simple matter. If, as Rockwell intended, Willie was like the average military man of his era, he would have entered military service without his high school diploma: 59 percent of white World War II veterans and 83 percent of black veterans were not high school graduates. Twenty-six percent of white veterans and 55 percent of black veterans had not attended high school at all (Mettler Reference Mettler2005: 56; Smith Reference Smith1947: 250). That so many returning veterans had minimal academic preparation points to the work that was necessary to allow veterans to transition from the military into college. This work ultimately required careful negotiation at the interstices of higher education, the federal government, and the armed forces.

To recognize this contingency is to raise the question of how it was overcome with so little fanfare that it so far has ceased to be part of the official GI Bill story at all. The question is made further intriguing by the fact that both sociological theory and historical context suggest institutional coordination of this type should not have been easy. Sociologists have long understood that the varied institutional sectors of modern societies are characterized by different logics of action, legitimation, and authority (Scott Reference Scott2008). These differing logics can make institutional coordination difficult and create conditions for cultural and organizational conflict (Friedland and Alford Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991) and, at times, for hybridity and innovation (Armstrong and Bernstein Reference Armstrong and Bernstein2008; Clemens Reference Clemens1993). When adjacent or overlapping institutional sectors are highly formalized, interested parties tend to protect their turf by specifying rules, procedures, and other means of defining reality on the terms of their own domain (Heimer Reference Heimer1999).

This generic potential for institutional conflict and protectionism was heightened by the specific historical context of World War II: the American tradition of local control of public education and institutional autonomy in higher education; and the general wariness of expanding federal and military power, especially when set against the backdrop of the rise of totalitarian governments in Europe. Conditions were ripe for interinstitutional quarreling because the GI Bill involved the federal government granting veterans an unprecedented educational benefit through officially nongovernment entities—universities. Who would make the rules for such an arrangement, on whose terms? As we will show, such questions were very live ones for American educators in this time and context.

To explain how those questions were ultimately resolved, we present a historical argument that recasts the implementation of the GI Bill as a project of interorganizational coordination among military and civilian, state and quasistate actors. In doing so, we speak to a central issue in the literature on American political development (APD): the technical mechanics through which interorganizational coordination was accomplished in the evolution of the twentieth-century US state. Specifically, we show how the transition to college was made legitimate for hundreds of thousands of veterans who had not entered or finished high school but who nevertheless were encouraged to take advantage of the federal-government tuition subsidies provided by the GI Bill. This feat was accomplished by a network of military officials, higher education leaders, philanthropists, and psychometricians who together created, disseminated, and endorsed the Tests of General Educational Development—the GED. Emerging after several years of focused negotiation and administrative tinkering at the close of World War II, the GED became the culturally and legally acceptable means for veterans without high school diplomas to have their academic worthiness certified for college entry.

In illuminating how recourse to a standardized test solved the problem of veteran demobilization and GI Bill utilization, we expand prior institutional accounts of the GED (Quinn Reference Quinn, Heckman, Humphries and Kautz2014) and draw on and extend the sociology of measurement. It is well known that measurement is often a key component of interorganizational cooperation, as in the creation of nested standards (Bowker and Star Reference Bowker and Star2000; Lampland and Star Reference Lampland and Star2009), the integration of complex administration and evaluation processes (Desrosières and Naish Reference Desrosières and Naish2002; Stevens Reference Stevens2007), and the creation of markets (Carruthers and Stinchcombe Reference Carruthers and Stinchcombe1999; Cronon Reference Cronon1991; Fourcade Reference Fourcade2011). In facilitating commerce across organizational borders, measurement often fulfills symbolic purposes as much as technical ones (Carruthers and Espeland Reference Carruthers and Espeland1991; Espeland and Stevens Reference Espeland and Stevens2008). Such purposes can either challenge or reinforce established hierarchies of power and prestige (Espeland Reference Espeland1998; Porter Reference Porter1996).

Beyond these technical and symbolic capacities, we highlight measurement's diplomatic potential. Where most of the literature on measurement stresses its power to impose or efface institutional distinctions, we emphasize its potential to demarcate them while allowing for interorganizational coordination. Measurement is diplomatic when it facilitates transactions across institutional distinctions while recognizing and honoring those distinctions. By providing a measure of high school equivalency, the authors of the GED facilitated transactions across the institutional logics of higher education and the military. In doing so, they enabled one of the most profound accomplishments of the twentieth-century US welfare state (Skocpol Reference Skocpol2003).

Like other forms of diplomacy, diplomatic measurement is predicated on reciprocal recognition of differences among negotiating parties. The ultimate settlement includes both the recognition of differences and the enablement of transactions across them. The accomplishment of the GED required universities to acknowledge the worthiness of military experience as a means of educational development, and military and federal officials to acknowledge academic—not veteran—status as the basis for college entry.

By illustrating how the accomplishment of the GED settled potential institutional conflicts posed by the GI Bill, we hope to build a more general case for diplomatic measurement as part of the repertoire of organizational techniques developed during APD. The GI Bill was by no means unique in the interorganizational challenges it posed. Indeed, the germinal contribution of APD has been to note that the American state as distributed “associational” (Balogh Reference Balogh2015), and, at times, “submerged” (Mettler Reference Mettler2011; cf. Mayrl and Quinn Reference Mayrl, Quinn, Orloff and Morgan2017) because of its reliance on a complicated mix of state and quasistate actors to enhance government power while remaining “out of sight” (e.g., Balogh Reference Balogh2009). A consequence of this decentralized state has been the ongoing challenge of coordinating activity between and across institutions. While scholars have noted the importance of legal proceedings (Balogh Reference Balogh2009; Novak Reference Novak1996) and specific institutions like schools and universities (Loss Reference Loss2012; Steffes Reference Steffes2012) that contributed to and benefited from this coordination, our case highlights measurement as an important additional mechanism.

To develop our argument, we rely on a range of empirical sources. The largest is the organizational archives of the American Council on Education (ACE), a nonprofit membership organization representing a wide variety of education and industry interests in education policy, which are housed at the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University. The originating purpose of ACE was to coordinate the response of higher education institutions to the war effort during World War I. It took the primary role in disseminating information about the GED after World War II, popularizing its use by secondary schools and colleges, and securing its legal recognition from state departments of education and licensing boards. Given ACE's position at the center of the complex network of organizations involved in the production and dissemination of the GED, the ACE archives provide the primary empirical base for this study. We rely additionally on archival records of the Joint Army and Navy Committee (JANC) on Welfare and Recreation located at the National Archives branch (College Park, MD); select materials from the US Armed Forces Institute housed at the University of Iowa; and the archival holdings of San Diego State University's historical test collection. These sources comprise documents, memoranda, subcommittee reports, and intra- and interorganizational correspondence providing rich insight into how diverse audiences viewed the acute challenges of the war effort and the potential of the GED to ease the problem of demobilization and readjustment. In our use of these materials, we draw upon and extend the original research conducted by Hutt (Reference Hutt2013).

Tensions at the Borders of Education and Government

The GI Bill was unprecedented in many respects and is rightly noted as a landmark piece of social legislation (Frydl Reference Frydl2009; Mettler Reference Mettler2005). The bill, signed into law in June 1944, extended a series of benefits to World War II veterans including unemployment benefits, access to low-interest mortgages, college and vocational school tuition benefits, and a monthly living allowance. Though administering a law of this scope and complexity—one that touched on so many different sectors of American society—was a considerable challenge, the interorganizational uncertainties it presented were hardly new. In this section, we examine some of this prior history by considering the ways in which the relationship between universities and the military during World War I framed the major concerns and responses to World War II veteran demobilization. University administrators, in particular, came away from the experience feeling that they had ceded too much of their authority and compromised their academic mission in their desire to accommodate military officials and support the war effort. These antecedents revealed how latent tensions between federal, military, and educational actors and the perceived “lessons learned” after World War I informed subsequent discussions of how best to handle demobilization after 1945.

Though American involvement in World War I was short, the brush with military and federal authority lingered vividly in the memories of American educators. At the secondary level, school officials struggled with how best to demonstrate their patriotism and commitment to the war effort while preventing the militarization of public education (Giordano Reference Giordano2004; Zeiger Reference Zeiger2003). While the US Secretary of War Lindley Garrison called for American schools to make preinduction military training a standard part of the school curriculum and many state legislatures enacted laws to that effect (Bell Reference Bell1917), educators were deeply split about the wisdom of these types of programs. Throughout August and September 1916, the New York Times dedicated a page of its Sunday paper to letters from secondary school principals from around the country expressing their views on the value of “preparedness instruction” (e.g., “Can Schools Give Military Training?” 1916; “Should Schools Give Military Training?” 1916).

Many of the principals expressed a desire for “universal military training” for youths starting at age 12, arguing that “the government should provide instruction, uniforms, and arms for all reputable secondary schools willing to take up military training” (Long Reference Long1916). Other prominent educators, like Leonard Ayres of the Russell Sage Foundation, argued that despite its widespread adoption “there is probably no other form of vocational training in our public schools yielding results of such meager practical value” (Ayres Reference Ayres1917: 157). The National Education Association, having decried efforts to introduce military training as “reactionary and inconsistent with American ideals” in 1915 (“Danger: The Illogical Pronouncement” 1915: 71), later moderated its position by distinguishing between its opposition to military training from its support of physical exercise that would include activities with obvious martial value like posture, discipline, and marching drills (Report of the Committee on Military Training in the Public Schools 1917)—a view echoed by many others in the debate (e.g., Marshall Reference Marshall1915). After the war, educators continued to worry about the precedent that had been set and actively lobbied to limit its influence. No less than John Dewey lent his name to the Committee on Militarism in Education that called for an end for military training in high school and compulsory military training in public colleges, though with admittedly mixed success (Barnes Reference Barnes1927; Hawkes Reference Hawkes1965; Lane Reference Lane1926; Neiberg Reference Neiberg2000).

Administrators of American colleges and universities were likewise conflicted about the proper approach to the American war effort. Beyond the philosophical questions about the proper wartime role of universities and scholars in a democratic society (Gruber Reference Gruber1975), higher education administrators had to contend with the practical, financial implications of the war efforts. Following US entry into World War I, colleges and universities saw a precipitous decline in the number of enrolled students (Capen and John Reference Capen and John1919: 46–47). This decline, along with a more general concern about maintaining the pipeline of American elites for commissioned military roles, led to the creation of a program called the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Under SATC, students could remain enrolled in college while completing military basic training. Though short-lived, the program had an outsized and enduring influence on university-military relations. Students at the time griped that SATC really stood for “Stuck at the College” (Friley Reference Friley1919: 63). Other critics complained that Congress had placed the War Department in charge of directing the training of college-aged men—a task for which it had neither expertise nor the capacity to coordinate among the implicated institutions (Capen and John Reference Capen and John1919: 49).

Some college officials believed that allowing the military to establish training beachheads on their campuses was essentially an attack on their institutional autonomy and professional status. As Texas A&M registrar Charles Friley described it, the War Department supplied its own officers “to relieve the college officials of all responsibility,” which had the effect of reducing academic officials to “mere office boys to camp commandants.” Yet having accepted the basic institutional arrangement, college officials could do little but swallow their pride and hope for a swift end to the war. As Friley (Reference Friley1919: 64), speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association of College Registrars, summed up the experience:

For the first time in history, probably, immovable bodies, represented by academic authority, were pitted against irresistible forces, represented by military authority. In some places both forms of energy were quite rapidly converted into heat; but in most cases the academic authority withdrew temporarily, with the idea probably, that prudence was the better part of valor.

It was not just academic authority that had given way to military imperatives during the war. Academic standards had also begun to bend in the name of military deference. After World War I, many college and university leaders believed that their support of the war effort required that they honor veteran service through the provision of academic credit. Schools like Harvard, Stanford, Berkeley, and the University of Illinois allowed students who were close to completing their course of study (seniors in the case of Harvard) to allow their military service to stand in for their remaining units (“Digest of Report of Committee on Officers’ Training School Courses” 1919). Considering both the tradition of veterans’ privilege (Skrentny Reference Skrentny1996) and colleges’ own role as sites of military training and instruction, college officials also found themselves being asked by returning veterans to grant academic credit for military instruction. The lack of an existing policy or precedent for such requests resulted in colleges adopting a wide array of policies with, in the evocative words of one registrar, “the delightful lack of uniformity of American institutions” (ibid.: 18). Though the issue was belatedly raised, and a recommendation made, at the meeting of the American Association of College Registrars in 1919, many felt that the opportunity to secure a uniform response through a policy recommendation had come and gone. On each campus, “[A]lready a body of precedents and working rules have been established” (ibid.). The result was the widespread practice that came to be referred to disparagingly as “blanket credit”—with veterans offered a set amount of credit for their time served in the military and, perhaps additionally, specific training courses.

The policy of blanket credit, combined with a lack of consensus on the academic value of military experience, ultimately proved troublesome for colleges as it allowed veterans to shop for the schools that would most generously credit their military service with academic spoils. Indeed, college leaders’ desires to avoid the return of blanket credit profoundly shaped their response to World War II veterans. Recognizing that the magnitude of the matter would be much larger this time around, academic leaders and their professional associations vowed not to repeat the mistakes of the prior war.

Beyond the challenges posed by the entangling of the martial and academic values of schooling, there were additional concerns over the growing influence of the federal government on education generally. The strong American tradition of local control of education made all centralizing efforts, even those initiated by state governments, subject to skepticism and contestation (e.g., Steffes Reference Steffes2012). This independence was even more closely guarded in higher education, where institutional autonomy and self-governance were both culturally and legally ingrained (Stevens and Gebre-Medhin Reference Stevens and Gebre-Medhin2016). The greatly expanded federal government of World War II made many academic leaders uneasy.

Despite their widely distributed governance, US schools at all levels adjusted their educational programs to support the war effort in the early 1940s. The National Association of Secondary-School Principals (NASSP) advised school leaders to think about ways to adjust school schedules to accelerate graduation timetables for high school seniors (e.g., Angus and Mirel Reference Angus and Mirel1999; National Association of Secondary-School Principals 1943). Universities took on increasingly large roles in assisting the American war effort through the conduct of military research and the training of military personnel. As others have explained in detail, the federal government relied substantially on colleges and universities to pursue various components of the war effort, establishing strong financial and programmatic ties between higher education and the federal government (e.g., Loss Reference Loss2012). While these new relationships were largely welcomed by academic leaders, they also produced anxiety about federal encroachment on institutional autonomy, and a new conviction that discretion over academic matters remain firmly in the hands of universities (e.g., Geiger Reference Geiger1993; Lowen Reference Lowen1997).

Finally, the encounter with fascist and totalitarian states abroad had a profound effect on how Americans viewed their own government. The ambivalent use of the term dictator, common in the 1920s, was traded for a meaning unambiguously evil (Alpers Reference Alpers2003). The highly centralized bureaucratic states exemplified by Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Soviet Union became a stylized “other” against which American policy making was defined (e.g., Gerstle Reference Gerstle1994). The contrast between democratic and totalitarian governments was painted nowhere more starkly than in depictions of their educational systems. The United States had no ministry of education or national curriculum that all young people were required to receive. This decentralization stood in contrast to what, in the American imagination at least, was the highly bureaucratic and centralized character of German schools that aided Nazi efforts to indoctrinate German youth. The specter of totalitarianism and the imagery of the Hitler Youth were powerful tropes that stalked even modest federal efforts to encourage wartime curricular adaptations. Special care was taken to use permissive rather than compulsory language, as in the case of the high school Victory Corps program that was offered up as a “[n]ation-wide framework of organization into which schools may, if they desire, fit their various existing local student war organizations” (Education for Victory, October 1, 1942, 3, quoted in Ugland Reference Ugland1979: 440).

For many the issue was not whether the federal government would exert its influence but how best to direct and manage that influence to preserve the independent, democratic character of American schooling. This is evident in a report by the Education Policies Commission, published in 1944 but in the works since the war's outbreak (Education Policies Commission n.d.). The volume, entitled Education for All American Youth, considers the postwar challenges of the school system. It identifies these challenges as stemming primarily from the relationship between the federal government and local schools and explores them by offering a “hypothetical” dystopian future picture of American education in which the federal government controls every aspect of school curriculum, teacher selection, and school personnel decisions. In an obvious allusion to contemporary events in Europe, the history reports that in this hypothetical future educators saw the steady growth and influence of federal power but failed “to direct educational developments in more desirable directions” (Education Policies Commission 1944: 2). The result was a complete federal takeover of the education system, with the curriculum becoming a direct extension of federal politics. Leaving little to the imagination, the authors spelled out the ominous consequences, explaining that in this hypothetical future, national elections,

history, government, and economics [curriculum] were quietly revised . . . [and] these new courses were prescribed for nationwide use in the federal secondary schools, junior colleges, and adult classes in 1954. Strict inspection was established by the Washington and regional offices of the [Federal Department of Education] to see that all teachers and youth leaders followed the new teaching materials exactly. (ibid.: 9)

As with all good cautionary tales, this one includes both a bleak portrait of the future and a clear prescription for how to avoid it. In this account, the crucial mistake is the mismanagement of federal influence by American educators. The danger posed by the federal government is not its financial involvement but rather that the government has leveraged its considerable resources to supplant existing institutions entirely: “It was the lack of federal assistance to the local and state school systems that created the necessity for our present system of federal control” (ibid.: 5; emphasis in original). In other words, and however paradoxically, a proper defense against federal control was to harness the power of the federal treasury to strengthen existing education infrastructure.

Concern about the need to embrace federal financial involvement in higher education while not relinquishing academic control was not isolated to histories of a hypothetical future. It was a very real worry for schools performing research on federal grants. Few were as enthusiastic about receiving federal government money for research than Stanford University, and yet Stanford took great care to mark the limits of government encroachment on its authority. Stanford officials lobbied to ensure that the federal government and its research agencies awarded grants to individual researchers, not to specific schools or departments. As Rebecca Lowen notes, such an arrangement “suggested, in form if not in fact, that the university was not a supplicant to the government but that the parties involved had reached a mutual agreement” (Reference Lowen1997: 47).

Such tensions were very much in the minds of those tasked with figuring out how best to cope with the demobilization and reintegration of some 16 million World War II veterans. As American educators understood them, prior experience counseled against passivity and in favor of coordinated efforts to actively manage government intervention in higher education, lest academic standards give way to militarism or legislative fiat. From the very beginning of the war, educators and their professional organizations were prepared to preserve, as best they could, the distinct logic of academic merit even as it became intertwined with military and federal initiatives.

Maintaining Distinctions

While prior experience alone would likely have encouraged the vigilance of many working at the intersection of government, the military, and higher education, the particularities of American military service during World War II served to heighten concern. In particular, as Christopher Loss has argued (Reference Loss2005), military officials became convinced that continuing education was crucial to the mental health, morale, and general effectiveness of servicemen. The military made the provision of educational opportunities an important focus of its Committee on Welfare and Recreation and led to one of the largest educational enterprises ever attempted when it created the US Armed Forces Institute (USAFI).

The USAFI represented a joint venture between the military and the University of Wisconsin, together with 85 nonprofit and for-profit schools, to provide high school and college-level correspondence courses to men and women serving in the American military anywhere in the world. USAFI was an important human-resources component of the war effort, with more than 1.25 million servicemen and women enrolling in courses by the end of the war (Loss Reference Loss2005). Even as schools began participating in this project, college administrators took steps to delineate the military context from the academic content of the courses. While most schools were willing to rely on the tests devised by the USAFI to determine satisfactory completion of the correspondence classes, they were less clear on how to assess the value of military experience. In January 1942, the National Conference of College and University Presidents on Higher Education and the War passed a resolution entitled “Credit for Military Experience” advising that “credit be awarded only to individuals, upon completion of their service, who shall apply to the institution for this credit who shall meet such tests as the institution may prescribe” (“Credit for Military Service” 1942; Tyler Reference Tyler1944). They hoped the policy would head off preemptive offers of “blanket credit” by colleges looking to buoy enrollments with returned veterans and instead lay down a marker for making credit conditional on some form of academic assessment.

In a flurry of correspondence between ACE and school officials about the best way to meet the challenge of crediting military service, the overriding concern was the return of blanket credit and the challenge it posed to institutional integrity (e.g., Brown Reference Brown1942; Brumbaugh Reference Brumbaugh1942, Reference Brumbaugh1943b; Goldthorpe Reference Goldthrope1943; Wiley Reference Wiley1943; Zook Reference Zook1942). One upshot of this correspondence was the publication of ACE's widely circulated pamphlet Sound Educational Credit for Military Experience (1943). The pamphlet urged schools and colleges “individually and through regional and other associations” to “go publicly on record as soon as possible” in “opposing indiscriminate blanket credit for military experiences” (American Council on Education 1943: 21; emphasis in original).

Beyond opposition to blanket credit, the overwhelming message of these communications was, as University of Chicago Dean of Students A. J. Brumbaugh put it, an urgent need to develop a set of tools and processes “to aid[e] institutions to maintain reputable academic standards and at the same time give due recognition to education gained through various informal and formal education programs provided by the military agencies” (Brumbaugh Reference Brumbaugh1943a). Such mechanisms, yet to be developed, would help ensure that higher education presented a united front to the challenge of maintaining academic standards amid calls for deference to military service. Simply put: Educators sought to define the specific organizational arrangements and procedures that would be used to accredit the educational attainment of servicemen.

That work had begun, in part, by October 1942 when E. G. Williamson, Dean of Students of the University of Minnesota; Ralph Tyler, Chairman of the Department of Education at the University of Chicago; and E. F. Lindquist, a psychometrician at the University of Iowa, convened a special meeting at the behest of the military to consider how best to coordinate educational activities between civilian educators, military educational officers, and their respective institutions, as well as the value of various test batteries for this purpose. The minutes of that meeting reflect a keen sensitivity to the challenges of interorganizational coordination and the need to maintain institutional distinctions. When it came to advising soldiers about their educational paths based on existing and yet to be developed tests, “Should this be transmitted to the soldier as well as to [the] school or college?” (Army Institute 1942: 3). The committee considered how this information should be routed: “whether [the] recommendation should come from [the] Army, Advisory Committee [of the Army Institute], or American Council on Education”—the three options reflecting the full range of options between total, joint, and no military jurisdiction (ibid.: 3).

It was ultimately decided that in all cases emphasis had to be placed on the maintenance of civilian control. Even as the US military encouraged its troops to avail themselves of USAFI, and even used academic progress therein as a basis for promotions, it stressed both to servicemen and civilians that the military was not in the education evaluation business. This deference did not mean military officials were uninterested in the academic recognition servicemen would receive for military training. Military officials frequently stated that civilian educators could do more to help the military evaluate the educational value of military programs, framing such evaluation in terms of duty. An indicative letter was sent from Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1944) to Paul Elicker of NASSP:

The Navy Department has frequently been asked to place an educational value on the various courses . . . in order that academic institutions may award proper credit to Naval personnel who successfully complete them. . .. It is the policy of the Navy department neither to give, nor to recommend, academic credit for courses completed during Naval service.

To underscore the point, he continued:

The Navy Department does not award degrees or diplomas. This function is performed by the colleges and secondary schools of the country. The Navy Department believes, therefore, that these institutions should assume responsibility for appraising educational programs for which academic credit is to be awarded.

The “appraising of educational programs” is precisely the role that the USAFI and its network of civilian educators began to take on as the war progressed. Throughout these efforts, the organization took great pains to emphasize that, even while the USAFI represented a joint military-civilian partnership, the creation and accreditation of materials remained strictly in civilian hands. As Ralph Tyler put it in a widely circulated article explaining the function of the USAFI, he, as the university examiner of the University of Chicago, served as the head of the test construction group for the USAFI (Tyler Reference Tyler1944: 59). He also assured educators that his staff “includes not only experienced examiners from the University of Chicago Board of Examinations but also a number of examiners drawn from other institutions,” to which he added “an examiner working in a particular field is one who has had his graduate training in that field” (ibid.: 59). NASSP similarly assured its members that the USAFI materials originated with civilian educators and were not intended to supplant the work of civilian institutions: “The War and Navy Departments realize that the educational experiences provided by military service differ in many respects from that provided in the usual curriculums of secondary schools and colleges” (National Association of Secondary School Principals 1943: 26). In any case, the decision to award credit or standing remained with individual institutions and not with the military: “The school, and not the Armed Forces Institute, will always be the accrediting agency” (ibid.: 25; emphasis in original). Emphatic, categorical statements like this one may have been a necessary response to reports from the field indicating that “letters from Veterans Administration officers regarding the granting of credit were rather mandatory in tone” (Advisory Committee for the Armed Forces Institute 1944b), as well as more general fears that the military was overstepping its bounds or that academic autonomy might be eroding (e.g., Rosenlof Reference Rosenlof1945; Williamson Reference Williamson1945).

Even after the USAFI had been established and procedures for the distribution of materials, recording, and reporting had been developed, the delicate balance between military and civilian jurisdiction had to be actively maintained. In 1944 the navy sought to streamline the process by “discontinu[ing] the use of any middleman between service personnel and the institution at which they want accreditation” (Osborne Reference Osborne1944a)—believing that the continued use of a USAFI involved “unnecessary delays” and that “Navy educational service officers are trained and competent educators, qualified to administer the tests” without additional civilian support (Advisory Committee for the Armed Forces Institute 1944a). The result was a stern rebuke from both army and civilian officials who warned “if the Navy persists in holding to the position it has taken . . . it will be subjected to a great deal of criticism from academic institutions throughout the country because of its reversal of its previously agreed upon policy” (Osborne Reference Osborne1944b; see also Spaulding Reference Spaulding1944). The civilian Advisory Committee to the USAFI (n.d.: emphasis in original) replied that:

[S]ince much time and effort has been expended in establishing acceptance of the Armed Forces Institute as the agency for facilitating accreditation . . . to introduce any other method at this time will produce confusion, weaken the position that has been attained, arouse protests from and jeopardize the cooperation of civilian agencies.

Though the navy would ultimately back down and accept the inherited arrangement after the USAFI promised to make testing materials more readily available, flare-ups like these underscored the need for active management of these relationships and the perceived need for mechanisms to safeguard civilian control over academic matters.

In 1945, members of the USAFI Advisory Committee began discussing plans for the continuation of accreditation activities after the likely shuttering of the USAFI at war's end. They agreed that any new committee be entirely under civilian control. As one member explained in a handwritten letter to John Russell, then Executive Director of Joint Army Navy Committee on Welfare and Recreation, “I think that the recommendation for a permanent civilian accreditation office is admirable and so wired you today. And I agree that it must be non-governmental” (Marsh Reference Marsh1945). In particular, they imagined that the future group would be housed at the ACE, which had extensive experience working at the intersection of federal, military, and academic interests (Marsh Reference Marsh1945; Rosenlof Reference Rosenlof1945).

We call out these empirical details to show that distinctions between the federal military apparatus and higher education were the subject of explicit discussion during World War II. Academic leaders wanted the tasks, financial support, and prestige associated with federal patronage, but they also jealously guarded academic jurisdiction over education and its certification. Even as civilian educators enjoyed official control over academic matters involving servicemen during the war, their communications betray anxiety that once their charges passed from servicemen to veterans, academic autonomy might give way to veterans’ privilege. In many respects, however, the civilian handling of military correspondence courses represented the simplest portion of the problem posed by those who were both servicemen and students. After all, correspondence courses bore all the traditional markers of traditional academic study: discrete course topics, assignments, and evaluations. And during wartime, soldiers were only preliminarily high school or college students, unable to redeem any accrued credit until after discharge.

As the war ended, the nation's universities shifted attention from the provision of educational materials to servicemen to the task of absorbing them into official student rolls. This new focus became urgent with the passage of the GI Bill in 1944. Given the limited formal academic preparation of so many veterans (recall that more than half of white veterans had not graduated high school, and a quarter of those had never attended), simply having all vets enroll directly as college students threatened to undermine colleges’ and universities’ discretion over academic worthiness. But excluding morally deserving veterans ran the risk of a school being labeled unpatriotic in public, and likely fiscally irresponsible behind closed doors given the amount of federal money at stake. The challenge was to find a culturally acceptable and academically respectable way to vet servicemen's academic skills and certify them as academically worthy of enrollment. The high school diploma had by this time become the marker of worthiness for college entry (Wechsler Reference Wechsler1977), but because the majority of World War II veterans did not have one, the USAFI went in search of a substitute.

A Diplomatic Measure

In October 1942, USAFI had approached famed University of Iowa testing expert E. F. Lindquist for assistance with developing a battery of tests to establish the equivalent of a high school education and a set of national norms for its use (Army Institute 1942). Lindquist had led the creation of the Iowa Tests of Educational Development (ITED), which were used around the country to conduct scholarship competitions for high school students seeking to go to college (Peterson Reference Peterson1983). Lindquist was the author of the popular textbook, Statistical Analysis in Educational Research (Reference Lindquist1940), and was a widely regarded expert on the topic.

The Iowa Tests had been designed to measure students’ general academic capacities regardless of the specific schools they had attended. Lindquist's initial proposal to USAFI was to adapt the Iowa Tests to fit the current and somewhat analogous situation of assessing the academic capacities of returning GIs (Army Institute 1942). Ralph Tyler and other members of the committee charged with considering the issue agreed that Lindquist's was their best available solution. To prepare the test for use by the military, Lindquist and USAFI staff condensed the basic structure of the ITED from nine subject areas to five: correctness and effectiveness of expression; interpretation of reading materials in the social studies; interpretation of reading materials in the natural sciences; interpretation of literary materials; and general mathematical ability. These would comprise the battery of the GED (American Council on Education 1945).

Taken together the tests were, according to Lindquist, “designed especially to provide a measure of a general educational development . . . resulting from all of the possibilities for informal self-education which military service involves, as well as the general educational growth incidental to military training and experience as such” and to “provide a measure of the extent to which the student has secured the equivalent of a general (nontechnical) high school education” (Lindquist Reference Lindquist1944: 364). In its final form, the test took 10 hours to administer.

Using a standardized test to answer a fateful administrative question was hardly a new idea. Due in large part to the extensive deployment of testing by the American military to sort personnel, and to the widespread use of IQ testing in the 1920s, the basic legitimacy of such techniques for making decisions about people was well established by the 1940s (Carson Reference Carson2007; Gould Reference Gould1996; Kevles Reference Kevles1968). The lingering problem for Lindquist was how to anchor his new test to traditionally accepted measures of schooling so that educators, colleges, and employers would consider the GED a valid measure of specifically academic attainment.

To address this matter, Lindquist's team decided to norm the test by administering it to graduating high school seniors nationwide and use that data as the basis for recommending a passing score for GIs. This testing was done between April and June 1943 and, with some requests for assistance sent out on military letterhead, involved the cooperation of 814 public (nontechnical and nontrade) high schools and 35,432 seniors. This number comprised a geographically representative group of seniors who were only months, or in some cases weeks, away from graduation (American Council on Education 1945: 8). From their scores, the USAFI decided it would calculate a set of regional and national norms that could serve as the basis for decisions about the appropriate “cut score” for the new exam.

An important feature of these norms was that they were reported in terms of GED scaled scores, not raw scores. This meant that the reported scores reflected the percentile of achievement, not the actual number of questions a test taker had answered correctly. The specific conversion between raw score and scaled score depended on the form of the test, but in each case a scaled score of 50 represented the median national score, with each 10 points on the scale representing one standard deviation (ibid.: 8). The benefit of such a scaled score was that it allowed for the ready comparison of a student's achievement across each of the five test segments and could easily be used to compare the relative achievement of students from across cities, counties, and states. While the scaled scores offered clear indication of relative achievement, the underlying measure—the test taker's absolute level of achievement—disappeared.

It is not clear from the available historical evidence that all the interested parties recognized the possibility that these scaled scores might conceal as much information they revealed. We do know that ACE (the nonprofit membership organization that drew members from across the education spectrum including national education associations like NASSP, universities, technical schools, and state departments of education) took the lead in disseminating information about the GED and other USAFI programs to education leaders nationwide. With funding from the Carnegie Foundation and the US military, ACE established the Committee on the Accreditation of Service Experiences (CASE) to spearhead this effort. CASE ultimately recommended a GED cut score of a minimum scaled score of 35 on each test of the GED or an average scaled score of 45 on all five tests (American Council on Education 1945). It is not clear from the historical record exactly what factors were considered in determining that the score of 35 would be the official cut score. However, it is evident from subsequent materials disseminated by CASE that they put considerable—at least rhetorical—stock in the fact in setting a score of 35, they had set a bar above the level of achievement of 20 percent of graduating high school seniors (e.g., Detchen Reference Detchen1947).

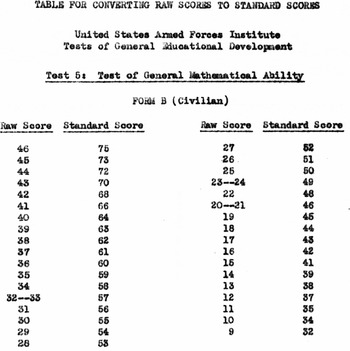

The documentation available through CASE, including the published Examiner's Manual, indicates that these scores corresponded to the seventh percentile of achievement for graduating high school seniors nationally (American Council on Education 1945: 4). However, the Examiner's Manual does not provide indication of what a scaled score of 35 corresponds to in terms of absolute level of achievement. To determine this, we compared the raw score to scaled score conversion tables for Form B of the GED, the form initially made available to states for their use. A reproduction of this document appears in figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Conversion table for GED Test, Form B, Test 5: Test of General Mathematical Ability. The recommended cut score was a Standard Score of 35, meaning a soldier had to answer 11 out of 50 questions correctly.

Following this simple procedure, we learned that for many of the tests the cut scores had been set remarkably close to the level of random guessing. On the mathematics test, examinees had to answer 11 of the 50 questions (22 percent) correctly to achieve the cut score of 35 recommended to states by CASE (US Armed Forces Institute 1944a, 1944b). With each question on the math test offering five possible answers and no deduction for wrong answers, an examinee guessing randomly would be expected to get a score of 11 or higher approximately 42 percent of the time. If a test taker could correctly answer any of the questions, his or her odds of passing improved substantially. The odds of passing the other tests in the GED battery by guessing randomly or by answering several questions and guessing on the remainder were similarly favorable. Attaining the CASE recommended cut score for the tests in reading materials in social studies, literary expression, and natural sciences required correctly answering 26, 28, and 28 percent of questions, respectively. With four answer choices offered for each question, these percentages involved answering one to three questions correctly above the level of chance (USAFI 1944b). On some later forms of the GED battery, examinees did not even have to rise to the level expected by chance because the cut score on certain subtests was set below the level of chance (Bloom Reference Bloom1958).

Thus, despite the effort that went into creating, norming, and attaining legal recognition for the GED, the result was a test that nearly all who took were likely to pass. Indeed, nearly all of those who took the test did pass it. According to an evaluation study of the GED program conducted in 1951, the pass-rate for veterans who took the GED between 1945 and 1947, estimated at more than a million veterans, 92 percent could reach the recommended cut score (Dressel and Schmid Reference Dressel and Schmid1951: 6). There was no limit on the number of times that a veteran could sit for the test, so that any who did not reach the cut score on their first or second tries were free to try again. Despite this decidedly low academic bar, the test gained near universal acceptance. By 1946, 44 of 48 states issued diplomas or equivalency certificates based on the GED (Commission on Accreditation of Service Experiences 1946) and 80 percent of colleges surveyed were willing to accept GED high school scores as the basis for admission (Dressel Reference Dressel1947).

The Tests of General Educational Development, together with the diplomas they conferred, became the official mechanism through which colleges would recognize and receive veterans. Though the GED represented a deviation from the direct categorical benefits provided by the rest of the GI Bill provisions, it nevertheless preserved the sanctity and unique value of military service. Soldiers qualified to take the GED by virtue of their military service even while states prohibited—at least initially—nonveterans from taking the test or receiving an equivalency diploma (Commission on Accreditation of Service Experience 1946). The creators of the GED also defined the test's measurement task in terms of quantifying the specifically military contribution to the individual's general educational development. As W. W. Charters (Reference Charters1947: 16), who had served during the war as a USAFI Advisory Board member and was formerly the director of the Bureau of Educational Research at Ohio State and member of the War Manpower Commission, explained:

The unknown land that lay between the military and the schools was academic credit returned veterans for their war experiences. After these men and women had spent months in a tense and gripping environment, had encountered many different cultures scattered over the globe, and lived under the radically different conditions of Army and Navy life, it was logical to assume that they had grown in general maturity, in the mastery of many techniques, in information and attitudes and that these could be translated into academic credits.

What was at stake in providing this translation was, in Charters's estimation, nothing less than “securing for the returning veterans full and fair academic credit for military experience” (ibid.: 17).

The GED made military training and academic attainment functionally commensurate while also distinguishing them symbolically. It psychometrically transformed military service into academic fitness. One of the most powerful rhetorical arguments, frequently made by GED proponents, was that recognition of the GED was an important part of honoring both academic and military standards. For example, NASSP (1943: 23) explained to its members:

A sound educational plan for completing graduation requirements through the proper accreditation of military experience leaves no place for special types of diplomas. These youth under consideration deserve the right to a first-class and a full-value diploma and the proper means of attaining it.

In other words, to do right by soldiers was to hold them to traditional standards of merit and the appropriately academic (“proper”) means of securing it.

Providing this means in the form of a standardized test affirmed both the meritocratic logic of higher education and the role of academics as the exclusive adjudicators of such merit. In light of concern that the massive expansion of the federal government during the war might result in excessive influence after war's end, a test that translated martial skills into academic fitness offered a comforting combination of scientific rigor and institutional neutrality. Indeed, the preservation of academic jurisdiction prevented the effort from being recoded as overt state action that might undermine academic autonomy and standards. Few people could accuse higher education of becoming a federal government fiefdom if academic leaders judiciously maintained academic measurement as a required screen. The fact that the level of the cut score virtually assured passage to those veterans willing to submit themselves to testing only underscores the point. As with so much diplomacy, maintaining appearances was essential.

Notwithstanding the concerted griping of a few academic elites who feared the dilution of academic prestige and quality by a massive influx of veterans (e.g., Eckelberry Reference Eckelberry1945), colleges nationwide swelled their enrollments to take in the federally funded students, resulting in total enrollment increases of 50 percent over prewar levels and allowing veterans to make up roughly half of all enrolled college students by 1947 (Bound and Turner Reference Bound and Turner2002). Yet, far from representing the co-optation of colleges by the federal government, the GED was seen as a great example of interinstitutional cooperation and coordination. As Charters put it, the GED program “demonstrated that the schools and military are able to work together so that they can cooperate in a joint program that is centered upon the welfare of the individual veteran rather than merely upon their own institutional programs” (Reference Charters1947: 19).

Still, as we saw with in the navy's earlier failed attempt at interorganizational diplomacy, the work required careful choreography and constant vigilance. The layered governance of the GED continued after the war as well: the military retained ownership of the test; ACE “rented” the test from the military, contracted with individual state education departments to create testing centers for its administration, and published “cut score” recommendations to states and schools; the University of Chicago housed, printed, and distributed the tests to the testing centers; and states subsidized the cost of taking the test to make it more widely available for veterans and, later, adults (Barrows Reference Barrows1948). The complexity of managing this ongoing arrangement proved too much even for the famed Educational Testing Service (ETS), which took over some of ACE's responsibilities for overseeing the GED in 1948 only to give those responsibilities back six years later (Whitworth Reference Whitworth1954). On our view, this complexity was hardly a design flaw but, rather, a negotiated outcome of the diplomacy that transformed soldiers into students in mid-twentieth-century America.

Diplomatic Measurement in American Political Development

In recounting how administrative leaders in government, the military, and higher education negotiated a mutually reasonable means for enabling war veterans to enroll in college, we have emphasized the distinctive role of measurement as a mechanism for managing tensions at the borders between institutional domains. The Tests of General Educational Development facilitated the movement of soldiers from military to higher education through federal generosity while respecting the traditional limits and institutional logics of the different domains. The details of its development and implementation strongly suggest that the GED served both a technical and ceremonial function by providing a display of academic and psychometric rigor while ensuring the successful passage of nearly all veterans.

The academic measures comprising the GED were diplomatic in that they facilitated transactions across institutional distinctions while recognizing and honoring those distinctions. While prior accounts of measurement in other organizational contexts have emphasized its ability to obfuscate, erode, or even erase institutional distinctions (Espeland Reference Espeland1998; Scott Reference Scott1998), the historical emergence of the GED suggests an additional way in which measurement can be deployed to enable cooperation across social and organizational difference. In the case of the GED, administrators in government, the military, and academia worked in tandem with established scientific experts to craft measures that were regarded as mutually acceptable for marking a highly consequential transaction: the flow of soldiers and financial subsidy from martial to civilian jurisdiction.

Diplomatic measurement shares some important qualities with Lampland's (Reference Lampland2010) “false” and “provisional” numbers. Lampland argues that the utility of such numbers is their capacity to provide the basis for subsequent planning, strategizing, or rationalizing of procedures rather than to provide stable referents. Likewise, the chief value of diplomatic measurement is the facilitation of other organizational work. The GED provided a recognition of military service and a plausible basis for college entrance even while it was a tepid measure of academic ability. The test did not produce false numbers in Lampland's sense, but its scores were similarly ceremonial. What mattered was that soldiers took the test, not how they scored. Indeed, as we described in the preceding text, the norming and reporting protocols accompanying the GED ensured that almost no one knew more than that soldiers had passed the exam. Tellingly, almost all of them did.

Our work also contributes to Porter's classic (Reference Porter1996) insight about quantification as a common purview of rising or “weak” elites, who often use numerical technologies to challenge incumbent authorities. In the case of the GED, numerical expertise accreted between two sets of sovereigns: government and military leaders on one side, academic leaders on the other. In our case, quantification enabled these parties to broker a truce regarding the “unknown land that lay between the military and the schools.” In doing so, they created new opportunity for E. F. Lindquist, ETS, and the larger occupation of psychometrics. There were arguably three elite parties in this story: the established ones from government and academia, but also ambitious players in a rising techno-scientific profession. As Lindquist and his colleagues labored to fulfill a highly visible government contract, they probably also burnished their own prestige as authors of a settlement between two of the most prominent institutions of their time (see also Abbott Reference Abbott1995).

Though our notion of diplomatic measurement is derived from the specific historical context of the relationship between higher education, government, and the military during World War II, it has broader applications especially for those studying the historical development and function of the American state. Our account highlights the value of Mayrl and Quinn's (Reference Mayrl, Quinn, Orloff and Morgan2017) general insights about recognizing state boundary management as an essential aspect of governance. To understand how a distributed government could coordinate across institutional domains effectively, it is important to examine systems developed to evaluate worth and worthiness across organizational distinctions. These are where acts of diplomatic measurement are likely to occur. In a manner parallel to citizen passports, diplomatic measures at once acknowledge sovereign borders and enable movement across them.Footnote 1

The post–World War II General Equivalency Diploma is hardly the only instance of diplomatic measurement in the history of APD. For example, the Federal Housing Authority drew largely on criteria for lending by industry professionals and private organizations even as it redefined the home lending credit market and who was eligible to participate in it (Gelfand Reference Gelfand1975; Hyman Reference Hyman2011; Stuart Reference Stuart2003; Thurston Reference Thurston2015). More recently, the federal government-backed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac set the FICO score (below 660) that would determine whether an individual's loan was considered prime or “subprime”—a decision with important consequences for who received mortgages and how they were handled by the government and financial markets (Poon Reference Poon2009). In that case, as in ours, the ultimate assessment of worthiness happened under criteria ostensibly dictated by autonomous organizations and professionals.

Similarly, the market for student loans and financial aid in higher education has long been governed by measurement treaties between students, schools, government agencies, and a variety of public and private lenders over time. The federal government makes continued receipt of Pell Grants contingent upon (among other things) enrollment in an accredited school, the absence of a criminal record, and something called “satisfactory academic progress” (Bennett and Grothe Reference Bennett and Grothe1982; Schudde and Scott-Clayton Reference Schudde and Scott-Clayton2014). The US Department of Education allows schools to determine satisfactory academic progress in a variety of ways, but it requires that they include some measure of the quality and pace of academic pursuit (https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/eligibility/basic-criteria)—usually the maintenance of a 2.0 GPA and degree completion within 150 percent of the published time frame (Satisfactory Academic Progress 2015, 34 CFR § 668.34). The need for colleges, employers, lenders, and loan servicers to verify enrollments and degree progress has fed the expansion of an independent nonprofit organization, the National Student Clearinghouse, for the express purpose of handling these tasks. The entire apparatus of government subsidy for college educations is predicated on measures of individual and organizational fitness jointly fashioned by government, academic, and third-sector officials.

Brokered measures such as these may be put in the service of any number of ends: minimizing the visibility of government action (Mayrl and Quinn Reference Mayrl and Quinn2016; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1991), obfuscating the interconnectedness of state, quasistate, and nonstate institutions (Lowen Reference Lowen1997) and, as we have shown in the case of the GED, enlisting parties from heterogeneous organizations into larger joint ventures. These utilities make diplomatic measurement a vital mechanism linking components of the plural and ever-evolving American institutional order.