I. INTRODUCTION

More than half of the adults in the world have no access to basic financial services.Footnote 1 Instead, they rely on informal mechanisms for saving and protecting themselves against risk, such as pawning possessions, buying livestock as a means of saving, and using moneylenders for credit.Footnote 2 Such measures are often both risky and expensive.Footnote 3

Mobile money facilitates access to financial services. Mobile money can be broadly defined as the use of mobile networks to receive financial services and execute financial transactions.Footnote 4 Typically, this is done through the storage of electronic money (‘e-money’) units in servers that can be accessed through a mobile phone.

The combination of e-money and mobile technology allows consumers to benefit from the wide coverage of mobile network operators (‘MNOs’). This has helped to improve the lives of many people in developing countries by providing access to financial services while reducing cost and improving security.Footnote 5

Mobile money continues to promote financial inclusion.Footnote 6 At the end of 2014, 16 markets already had more mobile money accounts than bank accounts, compared to nine in 2013.Footnote 7 There are more than 103 million active mobile money accounts globally with 255 services in 89 countries, with a particularly strong presence in sub-Saharan Africa, and expansion expected in other developing regions.Footnote 8

As mobile money grows, some questions will become more pressing: Are customers’ funds sufficiently protected against theft or the insolvency of their e-money provider; and are proper regulatory frameworks in place for the MNO's custody and management obligations?

In 2014, two of us published an article where we proposed the use of trust law to protect mobile money customer funds in common law jurisdictions.Footnote 9 Many civil law countries offer great potential for increased financial inclusion through the use of mobile money.Footnote 10 Although fund protection is a pressing issue in civil law countries, it is less readily resolved than under the common law. Some jurisdictions have tried to replicate the effects of the common law trust with local legal structures, there being no exact equivalent in civil law jurisdictions.Footnote 11 Whether precise replication is possible, or even desirable, is beyond the scope of this paper.Footnote 12

Whereas the common law trust regulates both rights in personam (eg customer rights against the provider of e-money services) and rights in rem (eg customer rights over funds), the civil law makes a sharp distinction between the Law of Obligations (for rights in personam) and the Law of Property or ‘Real’ Rights (for rights in rem). Consequently, legal institutions conceived to regulate one type of right may fall short on other rights. Providing e-money customers in civil law countries with similar protection to that provided by the common law trust requires analysis of different legal mechanisms. The complexity of this challenge determines the structure of the present article.

Section II describes the basic structure of an e-money transaction and identifies the main functions that a desirable legal mechanism would need to fulfil to protect e-money customers’ funds effectively. We also describe how the common law trust fulfils those functions and why protecting e-money customers’ funds in a civil law jurisdiction will require the analysis of different legal mechanisms.

Section III develops the inquiry in civil law jurisdictions, drawing on examples from both developed and developing countries.Footnote 13 The purpose is to develop a ‘civil law benchmark’ of legal institutions that (1) could constitute a firm basis for e-money, and (2) could be compatible with the civil law tradition, broadly understood. This section explores two legal mechanisms: one rooted in the Law of Property (the fiduciary contract) and another one rooted in the Law of Obligations (the mandate contract). Neither mechanism fulfils all necessary functions by itself. Nevertheless, regulators could try to combine them to fill the relevant gaps by enacting legislation. Alternatively, they could rely on insurance contracts as a fall-back option to cover the risks that e-money customers face.

Section IV explores different strategies available to regulators and discusses a series of issues to bear in mind when attempting to protect customers’ funds through regulation. The interaction of new regulations with existing legal rules could hinder competition between different providers or make cross-border recognition more difficult. Insufficient resources and customers’ vulnerability could also limit the effective implementation of any regulation. Section V concludes.

II. E-MONEY: TRANSACTION STRUCTURE AND RISKS FOR CUSTOMERS’ FUNDS

A. The Structure of an E-Money Transaction

Mobile money involves the transfer of e-money through mobile phones. E-money is typically defined as stored monetary value which is represented by a claim on the issuer and issued on receipt of funds for the purpose of making payment transactions and accepted by a person other than the issuer.Footnote 14

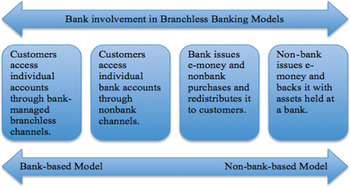

Different countries have developed different e-money business models, largely dependent on the type of entities providing the e-money service (‘Providers’). Different business models can be classified depending on the level of involvement of banks and non-bank institutions.

Figure 1: Bank-based versus non-bank-based modelsFootnote 15

In a bank-based model, customers have a direct contractual relationship with a bank, or with a non-bank agent contracting on behalf of a bank.Footnote 16 In some of these cases the services have been characterized as bank deposits, subject to deposit guarantee,Footnote 17 and restricted to institutions with a banking license.Footnote 18

In non-bank-based models, customers do not have a direct relationship with a bank, and thus do not need a bank account to make financial transactions.Footnote 19 In several developing countries, MNOs have become important non-bank Providers of e-money services.Footnote 20 Users buy a SIM card with the mobile money application for their phone, which has an electronic account associated to it. The non-bank Provider issues electronic value that customers purchase with legal tender, which the Provider will often store in a bank account. Customers can use this mechanism to deposit money into (‘cash in’) or withdraw money from (‘cash out’) their account. They will normally do so through specific access points such as agents of the Provider or Automated Teller Machines (ATMs). They can also use their mobile phone applications to send money to or receive money from other service users. The aggregate balance in each user's account is referred to as the ‘customers’ funds’.Footnote 21 The model is depicted in the diagram below.

Figure 2: Basic mobile e-money modelFootnote 22

Given the limited scope of banks in developing countries, particularly in rural areas, the provision of e-money services by non-bank institutions has great potential for fostering financial inclusion. However, it also brings legal challenges for the protection of customers’ funds: in these cases, e-money will normally be characterized as a sui generis financial product and thus will not be covered by protection mechanisms applicable to more traditional financial products such as deposit insurance. This paper explores how civil law jurisdictions can address these challenges.

B. Risks to Customers’ Funds, and Legal ‘Functions’: How the Common Law Fulfils the Functions and What the Challenges Are for Civil Law Systems

There are three main risks to customer funds that occur as a result of the transaction structure outlined above. These risks determine the functional characteristics required for any legal solution to be effective.

First, if the e-money Provider or bank where the Provider holds its customers’ funds becomes insolvent, customers bear the risk of not being able to recover their funds (‘insolvency risk’). The funds may be used to repay privileged creditors, or distributed pari passu among ordinary creditors of the insolvent institution. Any legal mechanism aiming to protect customers’ funds from insolvency must therefore fulfil the function of ‘fund isolation’.Footnote 23 This type of protection raises three issues:

• whether the legal mechanism employed has the effect of segregating customers’ assets from the assets of the Provider if the latter becomes insolvent;

• if the assets backing the customers’ accounts are held in a financial institution, whether those assets will be protected from the insolvency of the institution;Footnote 24

• whether customers will have preferential rights over separate assets, or pro rata rights over a single asset pool (segregated from the Provider's and the bank's assets).

Second, customers may not be able to cash out their e-money accounts upon request (‘liquidity risk’), if the ratio between e-money issued and customers’ funds is greater than 1:1. Regulation should thus safeguard customers’ funds by constraining the Provider from using those funds for its own purposes. This function is closely connected to fund isolation.

Third, customers’ funds may be lost due to ‘operational risks’ such as fraud, theft, misuse, negligence or poor administration.Footnote 25

The response to these risks in common law countries is closely associated with the legal institution of the trust. Two of us have proposed that a trust relationship could protect e-money customers against these risks: the Provider could act as trustee of the customers’ funds (ie trust assets) for the benefit of the customers (ie ‘beneficiaries’).

Figure 3: The application of a common law trust to e-moneyFootnote 26

The features of the trust fit the mobile money industry well.Footnote 27 A trust can fulfil the previous functions, and protect against (at least some of) the customers’ risks in holding e-money. First, a trust isolates customers’ funds from other assets held by the Provider. Typically, the Provider is the legal owner of the customers’ funds because these are kept in one or more accounts in the name of the Provider, not the customers’.Footnote 28 However, the assets are held in a separate account where customers are the beneficiaries.Footnote 29 Isolation from the financial institution's insolvency, and segregation of customer accounts, may be a more complex issue, and will depend on whether the Provider accounts are also trust accounts.

Second, trust law can safeguard customers’ funds from liquidity risk. Trustee duties can either be explicit (in the contract) or implied (by law)Footnote 30 and may require the provider/trustee to maintain a 1:1 ratio between e-money and funds on deposit in the trust account; invest customers’ funds in liquid assets; diversify its portfolio; and prevent it from using customer funds for its own purposes.Footnote 31

Third, trusts can be used to minimize operational risk in two ways. The trust deed can require the Provider to have the trust accounts audited regularly; and can provide for a third party (typically the relevant regulator) to serve as the Protector and monitor the Provider's compliance with its duties as trustee as customers may not have the capacity to monitor the trustee themselves.Footnote 32

Table 1. Functions for the protection of mobile money customers

Civil law countries raise more difficult issues, as there is no ‘civil law trust’. The most obvious reason for this is that the trust originated as a device to separate a specific asset, or group of assets, from the assets of the fiduciary, while facilitating the management of those assets by that fiduciary. Thus, trusts blur the line between bilateral obligations and property rights in a very ‘un-civilian way’.Footnote 33

Such incompatibility is far from widely accepted, however.Footnote 34 Legal structures such as the fiducie in France and the fideicomiso in Latin American jurisdictions have often been regarded as the civil law equivalent of, or at least as bearing a close resemblance to, common law trusts.Footnote 35 Furthermore, trusts set up in common law countries can be subject to recognition by means of the Hague Convention of 1985 on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on their Recognition (‘the Hague Trusts Convention’), although very few states have ratified the Convention.Footnote 36

The second, and less obvious, reason is that the Anglo-Saxon trust has evolved over centuries and its contours and tenets are well established and readily enforced across common law jurisdictions. The legal term ‘trust’ is easily recognizable, and associated with a series of rights and safeguards which are common across common law jurisdictions. This degree of consistency cannot be taken for granted for all private law institutions in civil law countries.

Thus, the quest is not for an equivalent of the trust, but for an institution, or combination of institutions, which can serve customers’ needs in the specific context of e-money, be sufficiently recognizable to be readily enforceable, and provide adequate rules to accommodate evolving situations. We now proceed to explain the relevance of such ‘recognizability’ and rules.

C. The Problem in Legal Terms: Default Rules and Mandatory Rules

This subsection examines two types of legal rules that fulfil the above functions required to limit the risks to e-money customers: ‘mandatory rules’ and ‘default rules’. Both common law and civil law jurisdictions recognize freedom of contract and pacta sunt servanda (ie that the terms agreed upon in a contract will be enforced by the courts). However, there are instances where the solution enforced by the courts may be ‘contrary to’, or ‘outside’ what the parties have agreed. Solutions ‘contrary to’ the agreement are contained in mandatory rules, and solutions ‘outside’ what the parties have agreed are contained in default rules.Footnote 37

The rationale for mandatory rules is difficult to apply in each case, but easy to explain. A strict enforcement of the terms of the contract in full presumes that (a) the parties are rational, (b) that they are fully informed, and (c) that all parties whose interests are at stake are involved. Regarding (a) and (b), mobile money customers may lack financial experience or financial education. Fully enforcing the terms of the contract could thus lead to results that are inefficient, in terms of resource allocation, or be seen as unfair.

The rationale for default rules is subtler, yet even more important, as even very sophisticated Providers cannot foresee all possible contingencies. Courts will enforce contract terms as a ‘plan A’, but default rules act as a ‘plan B’, in case a contingency arises that is not covered by the contract.

Civil law courts first try to ascertain the contract's ‘meaning’ or the parties’ ‘wishes’,Footnote 38 but at times are required to resort to default rules. To select the most suitable default rules civil law judges try to subsume the facts into one of the existing categories of legal transactions, by asking the following kind of question:

Which of the relationships envisaged in the law that have an element of custody or safeguarding (deposit, mandate, etc.) most closely resembles the relationship the Provider has with its customer? Footnote 39

Judges will have to choose between rules for fiduciary transactions, mandates, deposits or loans as default rules, which may result in different degrees of protection depending on the chosen institution.

The process followed by a civil law judge is summarized in the following decision tree:

Bearing this in mind, a Provider could simply steer clear of mandatory rules, and try to draft the contract in terms that not only stipulate the explicit solutions to specific problems, but also broader, background rules, to cover unexpected contingencies. However, this decision tree does not sufficiently take into account two important factors.

First, it does not acknowledge that it is a judge who decides whether there is a clear solution in the contract, or whether the contract can be interpreted to provide such a solution. A judge is not a contracting party, nor ‘neutral’ about her preferences between ‘contract solutions’ and ‘legal solutions’. In case of conflicting interpretations of the contract the judge may be tempted to hold that the contract was not clear enough to derogate from the legal rules she knows.Footnote 40

Second, in civil law countries this tendency to resort to the default rules of existing institutions is often reinforced by the doctrine of the causa. Causa resembles common law consideration but has further implications and, under some views, requires a judgment of correspondence or adequacy between the socio-economic function of the contract, and the socio-economic function of one of the contract ‘types’ (deposit, mandate or loan).Footnote 41 In the absence of a contractual provision, courts will tend to use the rules of the institution relied upon by the parties, as default rules.

In exercising in personam jurisdiction resulting from the Provider–customer agreement, this exercise may simply result in a more obstinate reliance by courts on legal institutions, rather than contract terms. However, in relation to fund isolation, the available structures of rights in rem under a civil code may result in the invalidity of the customer's claim over the funds, since, for rights in rem the doctrine of numerus clausus prevails.Footnote 42

If the structure of rights envisaged in the contract and those envisaged in one of the legal institutions contemplated in the civil codes do not correspond, it can create friction between the law and the goals of the contract (at best), or render the customer's rights over the funds ineffective against Provider's creditors (at worst). It is therefore critical to analyse the structure of rights in the existing figures contemplated under the civil codes. That is the purpose of Section III.

III. THE PROTECTION OF CUSTOMERS’ FUNDS IN CIVIL LAW JURISDICTIONS: A COMBINATION OF DIFFERENT LEGAL INSTRUMENTS

Civil law systems distinguish between rights in personam and rights in rem. Different legal instruments provide the default rules (and some mandatory rules) for the customer–Provider relationship, while other instruments provide rules for the relationship of the customer with the funds. On this basis, we examine ‘proprietary alternatives’ (mainly the rules on fiduciary transactions introduced in some civil law countries) (A), and then ‘contractual/obligational alternatives’ (mainly the rules on mandate) (B). The former falls short on remedies against the Provider, whereas the latter falls short of proprietary protections. We therefore also examine the possibility of specific regulatory interventions (C) that define e-money as a type of relationship of its own, similar to what has been done in the case of other financial transactions.

A. Proprietary Alternatives: The Fiduciary Transaction

1. Basic transaction

Perhaps the legal instrument that bears the closest resemblance to the trust in a civil law jurisdiction is the fiducia.Footnote 43 The fiducia encompasses a wide array of applications. Some jurisdictions regulate fiducia expressly; others only recognize it but do not have express legal provisions to regulate it; while some jurisdictions do not recognize it at all. Moreover, where the fiducia is recognized, it may be referred to by different names; and, even among those using the same name, its legal structure and effects may vary across jurisdictions.Footnote 44 It may be recognized as a product of the parties’ free willFootnote 45 or may arise by operation of the law.Footnote 46 The formalities required for its constitution may be more or less stringent. It may be limited to commercial transactions, or it may cover a broader range of situations, including successions, tax and charitable purposes.Footnote 47 Some jurisdictions may also impose restrictions on who has capacity to act as fiduciary.Footnote 48

This paper focuses on applications of fiducia that are achieved by an inter vivos deed. We will refer to them as ‘fiduciary transactions’. A fiduciary transaction can be broadly defined as an arrangement under which one party—the settlor—conveys property to another—the fiduciary—and the latter agrees to use that property for a specific purpose. The fiduciary agrees to transfer the fiduciary assets to one or more beneficiaries upon fulfilment of the agreed purpose.Footnote 49 When using the fiduciary assets, the fiduciary will be subject to a series of duties agreed upon with the settlor or determined by law.

Generally, fiduciary contracts fulfil two purposes: a) the administration of the fiduciary assets by the fiduciary; and b) the provision of security for one or more obligations of the settlor. The use of fiduciary contracts in the context of e-money services would normally fall within the first category. Typically, in order to guarantee that customers will be able to recover their funds, the Provider will settle a fiduciary contract by transferring the funds to a fiduciary institution that will hold the assets for the benefit of the customers (ie the beneficiaries).Footnote 50Figure 4 depicts this situation.

Figure 4: Fiduciary transactions in the context of e-money (I)

In some jurisdictions, customers will transfer the funds to the Provider under a fiduciary contract, which holds the Provider as a fiduciary.Footnote 51 If the Provider does not have the necessary infrastructure to assume safeguarding duties it will normally deposit the customers’ assets with a financial institution, which may not have fiduciary duties under the law. This potentially undermines the protection of customers’ funds. Figure 5 depicts this situation.

Figure 5: Fiduciary transactions in the context of e-money (II)

Alternatively, the Provider could be considered the beneficiary, and the bank the fiduciary. In order to protect the customers’ interest in the funds the customers and the Provider could enter into a second fiduciary contract, where the Provider would be the fiduciary, and customers the beneficiaries.

2. Fulfilment of functions

a) Fund isolation

The legal implications of the settlor's transfer of property to the fiduciary are particularly relevant when examining the effects of the fiduciary's insolvency on customers’ funds. While some jurisdictions recognize the validity and effects of such transfers, others do not.

There are various ways in which a fiduciary can hold property rights over fiduciary assets. Some jurisdictions conceive fiduciary assets as a patrimonyFootnote 52 of the fiduciary, separate from her personal patrimony. In these cases, when the fiduciary is involved in an insolvency proceeding, the fiduciary assets do not form part of the insolvent estate. The fiduciary contract is terminated and the assets are transferred to the beneficiary.Footnote 53 In some cases, legislators have introduced express provisions to guarantee the isolation of those assets.Footnote 54

Some jurisdictions allow creditors of the fiduciary patrimony to have recourse against the settlor's patrimony when the former is insufficient to satisfy all claims.Footnote 55 This issue can be addressed through contractual provisions limiting what creditors of the fiduciary patrimony can claim.Footnote 56 Contractual solutions, however, are far from perfect.Footnote 57

A more innovative approach is that of the fiduciary assets constituting an independent patrimony from those of the settlor, the fiduciary and the beneficiary. In Quebec, for example, ‘a fiducie involves the constitution of a patrimony by appropriation (patrimoine d'affectation), that is to say a patrimony dedicated to a purpose, and the [fiduciary] is characterized as an administrator of the property of another person’.Footnote 58 The settlor, fiduciary and beneficiary do not have any property rights over the assets.Footnote 59 Consequently, in the event of the fiduciary's insolvency, the fiduciary contract is not necessarily terminated like in the previous cases.Footnote 60

Some civil law countries accompany the rules stipulating the existence of a separate patrimony with insolvency protections that permit the separation of fiduciary assets upon the fiduciary's insolvency,Footnote 61 whereas others even provide for the replacement of the fiduciary on an interim basis, when insolvency proceedings may jeopardize the performance of its duties.Footnote 62

In the context of e-money services, this analysis poses different questions depending on how the fiduciary contract applies to the e-money transaction. Under the first formula described in Section IIIA.1, the Provider (ie settlor) enters into a fiduciary contract with a financial institution (ie fiduciary) under which the latter manages the customers’ funds (ie fiduciary assets) for the benefit of the former's customers (ie beneficiaries). If property over the funds were transferred to the fiduciary, customers’ interests in the fiduciary assets would only be protected against insolvency risk if those assets were separated from the fiduciary's patrimony. If there were no transfer of property under the fiduciary contract, the protection of customers’ interests in the fiduciary assets would require the segregation of those assets from the patrimony of the Provider.

Under the second formula, property over the customers’ assets would necessarily have to be transferred to the fiduciary for the fiduciary contract to fit the structure of the e-money transaction.Footnote 63 Protecting customers’ interests in the assets would require segregating the fiduciary assets from the personal patrimony of the Provider. If the Provider were to deposit the assets with a bank, protection of customers’ funds would also require segregating the fiduciary assets from the bank's patrimony. However, as mentioned above, this would need to be expressly included in the fiduciary contract between customer and Provider.

b) Fund safeguarding

Fund safeguarding relates to the personal obligations imposed on the fiduciary by legal institutions in civil law countries. However, some of those personal duties are inextricably linked with the fund isolation function outlined above. In particular, fund isolation can be rendered very difficult if there are no duties and limits on the way the fiduciary stores and manages the customers’ funds. Some of the fiduciary laws studied include express provisions requiring fiduciaries to keep fiduciary assets segregated,Footnote 64 while in jurisdictions where there is no express stipulation the duty can be deduced from the autonomy of the fiduciary patrimony,Footnote 65 and the fiduciary's mandate to manage that patrimony to fulfil the terms of the fiduciary contract.Footnote 66

Parties to a fiduciary contract can agree on duties that will bind the fiduciary's use of the fiduciary assets for the projected purpose.Footnote 67 Although such fiduciary duties could also be determined by law, most statutes generally refer to the duty of the fiduciary to serve the terms of the fiduciary contract, or its duty to act with necessary diligence.Footnote 68 When fiduciary duties are not expressly included in the law, courts may find certain duties implicit in the adequate safeguarding of assets—but only if the transaction is conceived as one where the fiduciary acts in the beneficiary's interest, as opposed to simply holding different interests in a patrimony.

Under a common law trust, beneficiaries have an equitable right in the trust assets that allows them to trace the proceeds resulting from the assets transferred in an unauthorized disposition in breach of fiduciary duties.Footnote 69 The status of beneficiaries’ claims in such cases is more problematic, as the law of subrogation in rem, which fulfils a similar function to tracing, is nonetheless less developed.Footnote 70 When the assets are money in bank accounts, however, the protection may be similarly weak.Footnote 71

Beneficiaries under fiduciary contracts have other rights available to protect their interests. Typically they have a right to information about the fiduciary's use of the fiduciary assetsFootnote 72 and a right to substitute the fiduciary under certain circumstances.Footnote 73 Some jurisdictions specifically provide that the settlor and the beneficiaries may take action against the fiduciary to compel him to perform his obligations, to refrain from any harmful action to the fiduciary patrimony or the beneficiaries’ rights, and to impugn any fraudulent acts.Footnote 74 In other jurisdictions, however, beneficiaries have very limited rights to protect the fiduciary assets.Footnote 75

Fiduciary contracts could provide for specific rules to ensure that the Provider always has a 1:1 ratio between the total outstanding amount of e-money issued (or ‘e-float’) and the customers’ funds backing it. There are three main categories of rules that could serve this purpose: a) the parties could expressly restrict the Provider's right to use customers’ funds;Footnote 76 b) the Provider could be required to manage customers’ funds within very narrow parameters, eg investing the cash in highly liquid assets such as bank deposits or highly rated government securities;Footnote 77 and c) the parties could agree that the Provider will diversify the assets in which it will invest the customers’ funds.

These rules can form part of the fiduciary duties included in the relevant fiduciary contract, determining how the fiduciary will manage or dispose of the assets to fulfil the purpose agreed in the contract. These duties can be expressed explicitly in the fiduciary contract, in specific e-money regulation, in fiduciary legislation or in general law. They can also be implied by the courts to ‘fill a gap’ in the fiduciary contract, particularly in those jurisdictions where the fiduciary contract has been recognized and developed by case law.

c) Protecting customers’ interests against operational risks

The fiduciary duties under a fiduciary contract can also serve as a protective mechanism against the operational risks described in Section IIB. Fiduciary contracts can provide for two mechanisms to reduce operational risk with regards to e-money customers’ funds.

First, the fiduciary may be required to keep records of the accounts where it keeps the fiduciary assets and to have those accounts audited by an authorized auditor.Footnote 78 These requirements may be expressly included in the fiduciary contract or may be provided by law. The fiduciary contract could even designate a specific auditor or describe the process of designation.

Second, the parties may provide for a third party expert to monitor the fulfilment of the fiduciary's duties, especially those relating to fund safeguarding and auditing. Normally, parties will specify in the terms of their agreement whether the settlor or beneficiary can delegate their supervisory powers over compliance of fiduciary duties to a third party (‘the Protector’).Footnote 79 However, some jurisdictions expressly provide that the settlor and any beneficiaries have the ability to do so.Footnote 80

Additionally, the fiduciary has a duty to account to the settlor and/or beneficiary for the management of the fiduciary assets.Footnote 81 The parties could agree that such duty to account is to be subject to the review of a third party expert.Footnote 82 However, this would seemingly provide less protection against the mismanagement of customers’ funds by the Provider because the third party expert would focus only on the accuracy of the information provided by the Provider, not on the Provider's compliance with its fiduciary duties. Nevertheless, allowing a Protector to intervene in the supervision of the Provider's compliance with its fiduciary duties is important as e-money customers in developing countries are likely to have very low levels of financial literacy.Footnote 83 This could prevent them from monitoring the Provider effectively and leave room for the latter to act opportunistically and to jeopardize the safety of customers’ funds.

Protectors would need a solid financial and/or technological background and a deep understanding of the financial services and mobile industries in the relevant jurisdiction. The role could be done by public institutions such as e-money regulators, or alternatively by central banks and securities regulators.Footnote 84 It could equally be performed by private institutions such as auditors, banks, law firms or technology consultants.

Where a private entity undertakes the role of Protector, there is a concern that the third party expert may act in its own interest rather than in the interest of e-money customers. It is therefore useful to query whether the role implies the assumption of fiduciary duties by the third party expert towards e-money customers. The parties could so agree under respective agreements. Mandatory rules could also specify the application of fiduciary duties to protect the interests of e-money customers. In the absence of any such agreement or of any mandatory rules, the question would be answered on a case-by-case basis. While courts are likely to resort to default rules to fill any gaps in the parties’ agreement, it may be difficult to effectively appoint a protector if the law is scant on the duty to account and fiduciary duties.

B. Contractual/Obligational Alternatives: The Mandate Contract

Under a mandate contract, one party (the agent) commits to act on behalf of another (the principal) for a fee, unless otherwise specified.Footnote 85 The agent is liable to fulfil the mission mandated by the principal in the capacity and under the circumstances specified in the contract. The mandate contract provides a basic foundation for other, more complex, legal mechanisms such as deposit and loan contracts, as well as fiduciary mechanisms.

In the context of e-money services, the mandate contract cannot be used as the sole institution to regulate the relationship between the customer and the Provider. By purchasing e-money from the Provider, the customer relinquishes proprietary rights over the funds in exchange for the right to dispose of the e-money. The customer would thus not have the legal capacity to mandate the Provider to dispose of funds that she no longer owns.

Nevertheless, the mandate contract could regulate the relationship between the Provider and a bank. The Provider could mandate the bank to keep custody of the customers’ funds in accordance with a series of duties specified in the contract. Like the fiduciary under the fiduciary contract, the agent would be bound by the duties specified by the parties in the contract or the enhanced good faith duties provided by law. Such quasi-fiduciary responsibility vis-à-vis the principal could potentially provide e-money customers protection against liquidity and operational risk. The mandate contract, however, would not provide protection against the risk of the Provider or the bank becoming insolvent. The segregation of those assets would require an express legal mandate or the creation of a separate patrimony from that of the Provider or the bank. These are, precisely, the characteristics of the fiduciary contract. If the agent became insolvent, the assets would not fall into the agent's insolvent estate because they never left the principal's patrimony.Footnote 86

The mandate contract cannot, per se, effectively protect e-money customers against the risk of the Provider's insolvency. However, as a legal mechanism de minimis, mandate contracts provide an important body of default rules that regulate the duties of the Provider towards the customer, arising from the statutory duties of an agent to act in the interest of the principal,Footnote 87 and to exercise due care and skill.Footnote 88

Under certain circumstances, fiduciary contracts can effectively isolate customers’ funds in the event of the Provider's insolvency, as well as provide customers with protection against insolvency risks, protection against certain operational risks, and the flexibility to introduce extra duties. Their main handicap is their lack of general background rules regulating the duties of the fiduciary towards the customer. This is the gap that other private law arrangements, such as the mandate contract, are able to fill. Interestingly, some countries that have defined fiduciary transactions by focusing on the relationship of the parties with each other rather than on the assets have done so by using the mandate and commission contracts as a model.Footnote 89 This approach could be the blueprint for mobile e-money transactions.

To hold that the mandate's shortcomings can be corrected by means of better contractual clauses would be wrong for two reasons. First, a contract cannot predetermine the protection of a right upon insolvency unless the right created by the contract belongs to one of the categories that enjoy insolvency protection.Footnote 90 Second, courts confronted with a difficult case of fund isolation (eg upon the Provider's or the bank's insolvency) would lack background principles with which to determine whether customers’ funds have been properly ring-fenced.Footnote 91 Consequently, a mandate contract would not be suitable on its own to regulate e-money services;Footnote 92 at best, it could provide the basis for the Provider's duties vis-à-vis its customers, but not for the rights over the funds.

C. Regulatory Alternatives: Regulating Functional Duties Directly and/or Requiring Insurance

The mechanisms and their respective drawbacks described above reveal the difficulty of providing a single solution for the effective protection of e-money customers’ funds in civil law jurisdictions. In light of this difficulty, policymakers have two alternatives. First, the functions outlined above could be regulated directly, eg under an e-money statute or regulation. Second, in the absence of such direct regulation, regulation could protect customers’ funds indirectly by, for instance, requiring insurance.

1. Direct regulation of functional duties

The first solution would be to introduce a specific piece of legislation requiring Providers to adopt some of the protective mechanisms described in Section IIIB, eg fund isolation, fund safeguarding and protection against certain operational risks. Direct regulation could also grant e-money customers the right to monitor the Provider's compliance with these duties, or require the appointment of a Protector to do so.Footnote 93 In the European Union, Directive 2009/110/EC of 16 September 2009 (the ‘E-Money Directive’) is an interesting example of direct regulation in this regard.Footnote 94 The 2007/64/EC Payment Services Directive also provides for specific safeguarding requirements (in case the Provider undertakes other activities), with a specific mandate to avoid commingling of funds, and protection against the Provider's other creditors in the event of insolvency, but without specifying in advance the property arrangements through which this must be achieved.Footnote 95

An explicit regulatory solution looks to be the best option as specific rules can be promulgated to afford the specific protections, and allocation of rights and obligations, required. The challenge, however, is that the specific legal rules also need to be flexible enough to accommodate new situations as the market evolves and new problems arise. Such flexibility depends on whether the rules can be subject to the kind of interpretation exercise described in Section IIC, as well as on how they interact with other rules. Furthermore, if the duties are regulated in functional terms, this implies that the parties and the courts will still be left with the question of what is the private law arrangement that supports the regulatorily imposed duties. It is difficult to consider a regulatory approach as the sole solution, but, as we argue below, the regulatory approach will most likely form a key part of the solution to protecting e-money customers.

2. Insurance

Regulators could also require the insurance of e-money customers’ funds against any of the risks identified in Section IIB. This is an approach also adopted in the European Union for payment services.Footnote 96

The requirement to insure customers’ funds could be legislated to strengthen the protection that existing legal instruments would provide to customers’ funds, or to protect customers’ funds where no legal instrument in the relevant jurisdiction fulfils the functions identified in Section IIIA. Regulators would have to decide whether insurance would be provided by the market or by public institutions.

Although an insurance policy, either as a complementary or a stand-alone mechanism, would ensure effective protection to e-money customers’ funds, there are important issues to consider.

First, the e-money market conditions may not be ideal for the viability of an insurance scheme, for example, where the number of potential e-money customers is small.Footnote 97

Second, one could expect Providers to pass on the cost of mandatory insurance to customers. This could have a serious impact on the demand for e-money services and on its potential as a tool for financial inclusion. One should expect the cost of insurance covering all the risks described in Section IIB to be higher than insurance used as a complementary mechanism to compensate for specific deficiencies.

Third, in the event of the Provider's insolvency, insurers may refuse to compensate customers until the end of the insolvency proceedings, which may impose hardship on impecunious e-money customers. Additionally, given the lack of sophistication of many e-money customers it will be important to ensure easy access to financial compensation.

Fourth, insurance may create moral hazard, as Providers would have fewer incentives to comply with the protection rules described above. Effective monitoring by the competent authorities, as described in Section II, will be essential.Footnote 98

Fifth, insurance will only give customers a personal claim for damages against the insurance company in the event of the Provider's insolvency. This protection is not legally as strong as that provided by other mechanisms where customers remain the owners of their funds or where those funds, despite being owned by the Provider, are separated from its personal patrimony.Footnote 99

Finally, insurance will not eliminate counterparty credit risk for e-money customers. Insurance, effectively, will substitute the risk of the Provider becoming insolvent with the risk of the insurer becoming insolvent. Any insurance scheme should rely on financially robust insurance companies or ensure sufficient public funds to cover the potential losses of customers. Where the insurance industry is not very strong or where the government may be in a situation of financial hardship, access to compensation must be made available through other means.

Table 2 provides a summary of our findings in relation to the different legal mechanisms available to regulators in civil law countries to protect e-money customers’ funds.

Table 2. The protection of e-money customers’ funds under civil law

The table shows there is no single mechanism that will effectively protect e-money customers against the three risks identified in Section IIB; so we anticipate any regulatory strategy to include a combination of different legal mechanisms. In this context, the interaction of the rules applicable to such mechanisms will be crucial to provide effective protection. We turn to all these questions now.

IV. A ROADMAP OF LEGAL STRATEGIES FOR E-MONEY

The previous sections discussed the benefits and risks of using different approaches as a background for e-money systems. None of the private law alternatives (fiduciary or mandate contracts) adequately fulfils all the necessary functions, which would make a specific regulatory intervention preferable. We now use the previous analysis to provide a broader menu of policy choices. First, we begin by exploring the options available to regulators to protect e-money customers’ funds (A). Second, we introduce additional arguments about how regulatory certainty should be weighed against the need to foster competition between e-money models and the legal compatibility of rules, both on a domestic and a cross-border basis (B). Finally, we address issues of regulatory capacity and financial literacy that, in practice, limit regulatory intervention (C).

A. Summary of the Options Available to Regulators

1. Fund isolation

The first priority for policymakers should be to guarantee the isolation of customers’ funds. Policy strategies will vary depending on whether fiduciary contracts are recognized in the relevant jurisdiction and on the treatment given to fiduciary assets receiving such recognition.

Where fiduciary contracts are recognized in the relevant jurisdiction and fiduciary assets are separated from the personal patrimony of the fiduciary, Providers should rely on fiduciary contracts to protect customers’ funds. Lawmakers could include statutory requirements for those Providers to hold customers' assets under a fiduciary contract (or including it as a preferred model to safeguard customers’ funds). Several civil law jurisdictions have implemented this regulatory strategy, often within the broader framework of e-money regulation.Footnote 100

In jurisdictions where fiduciary contracts are recognized but the separation of assets from the fiduciary's personal patrimony is unclear, it will be important for regulators to clarify customers’ protection against the risk of the fiduciary's insolvency. Direct regulation could be of general reach (for all fiduciary contracts) or narrower in scope (eg only affecting fiduciary contracts for e-money accounts). Alternatively, in countries where private law arrangements are difficult to amend without upsetting the whole civil code system this could be done by introducing specific provisions in the relevant insolvency laws, which would give e-money customers a right to segregate their assets from those of the insolvent estate.Footnote 101 Yet another possibility would be to introduce ring-fencing requirements to require Providers, for example, to carry on their e-money business through a separate legal entity, which would hold the latter's funds under a fiduciary contract.Footnote 102 Regulators could also require Providers to subscribe to an insurance policy to cover the risks for customers’ funds. This alternative could be complementary to the fund isolation strategies outlined above, or be enacted as a stand-alone option.

Where fiduciary contracts are not recognized, there are limitations on the necessary protective mechanisms private parties can create to make e-money work. In such a context, legislation could be passed that expressly contemplates e-money as a new type of admissible private law arrangement, without making a broader statement about the admissibility of fiduciary transactions as a whole.Footnote 103 Such legislation could also rely on the enhanced good faith duties of mandate, but should introduce specific fund isolation protection in case of insolvency.

However, there may be reasons why the protection of e-money customers’ funds may not justify a full reform of the relevant legal system.Footnote 104 In such cases, those countries cannot entirely rely on an institution like the mandate, because it presumes, rather than regulates, the separation of funds between principal and agent. The patrimonial relation would normally be seen as a loan or a deposit. This would create some friction, due to the lack of background rules on segregation of assets by the borrower (Provider) under the loan, and the lack of background rules that authorize the depositary (Provider) to dispose of the assets under the deposit.

The following table provides a summary of the options available to legislatures for the protection of customers’ funds against the risk of the fiduciary becoming insolvent:

Table 3. A summary of policy options to achieve fund isolation

2. Fund safeguarding and protection of customers’ interests

The second policy priority is to ensure fund safeguarding and to protect customers from operational risk. Some rules on fiduciary transactions provide broad conduct duties, but many do not.Footnote 105 Even if such duties could be seen as implicit background duties, they may not foster market confidence if their content is too broad and they are able to be derogated from by contract. Specific statutory rules could provide the minimum content of the relationship between Provider and customer necessary to protect the latter's funds. Such content would not be subject to derogation or waiver in the contract.Footnote 106

Such minimum content could include specific safekeeping duties for Providers eg to deposit customers’ funds in a separate bank account or to invest customers’ funds in safe, low-risk securities, such as government bonds, in the name of the customers.Footnote 107 Regulatory provisions could also specify further the content of safekeeping duties,Footnote 108 and be connected with insolvency rules that provide protection upon the Provider's insolvency (eg rights of separation or priority rights). Such sets of duties would also support fund isolation, and would be of particular importance in countries that do not recognize fiduciary transactions.

Again, another regulatory alternative would be to require Providers to subscribe to an insurance policy that covers the losses of customers’ funds in the event that the Provider becomes illiquid or it is not able to return the customers’ funds for any reason other than insolvency. This alternative could be complementary to the regulatory strategies outlined in the previous paragraphs or it could be enacted as a stand-alone option.

In Section III we considered private law and regulatory solutions as alternatives to achieve the same end: one would be driven by the choices of market participants, the other by legislative mandate or regulatory design. However useful that division may have been for illustrating the different choices, in reality it would be rare for a country to adopt an ‘e-money legislative strategy’ that is not a ‘mixed’ strategy, in the sense that it combines (a) reliance on the parties’ ability to craft a menu of contractual solutions for market needs, with (b) specific regulatory rules that are tailor-made for the needs of the e-money industry, and (c) private law rules that provide the background for both contract solutions and regulatory rules.

The previous discussion holds important lessons for policymakers as well as for private parties. Rather than an exercise where we seek the best institution to fulfil the necessary functions the answer may lie in a combination of institutions. Fiduciary transactions are the best private law solution in terms of fund isolation, and in countries that recognize them they should provide the basis for e-money relationships. However, fiduciary transactions provide limited comfort in relation to liquidity and operational risks given the lack of specificity beyond the most basic fiduciary duties. Mandate contracts, on the other hand, which say nothing about segregation, provide a more sound and flexible basis for operational duties. Thus, the ideal solution should involve some combination of mandate and fiduciary transactions. Legislation could make a reference to the mandate to fill the possible gaps of the fiduciary's duties in a fiduciary transaction. For private parties this could involve different permutations, which could also give grounds for the Providers to compete between themselves.Footnote 109 In any event, requiring the Provider to subscribe to an insurance policy could always be contemplated as a complementary fall-back option.

B. How Can Legislatures Grant Protection while Fostering Competition between Different E-money Models and Ensuring Cross-border Compatibility?

If the main problem of private law background rules is their lack of certainty (as they are designed for a wide variety of cases) the problem of regulatory rules is their lack of flexibility. Thus, it is important for policymakers to consider the trade-offs between certainty and rigidity, an analysis that is particularly useful when comparing regulatory solutions with private law solutions, but which can also be applied to evaluating the different private law solutions.

Let us begin with regulatory solutions. Regulatory rules are typically mandatory, and their scope of application is normally accompanied by a ‘reserve of activity’ clause, meaning that the provisions under the specific act will be applicable only to the entities expressly authorized to provide the regulated service.Footnote 110

This requires active engagement by the financial supervisor, which must be up to the task. This is particularly important considering that, in many cases, the zeal by which supervisors control compliance ex ante (ie before granting the authorization) is greater than that exercised when controlling compliance ex post (ie fulfilment of segregation, safeguarding and management duties).

If the supervisor appointed is the central bank, or a similar banking supervisor, the system is most likely to be bank-biased. In particular, the procedures for authorization will tend to mirror the characteristics required for the authorization of financial institutions, which will enjoy an advantage in terms of experience with compliance procedures, and, in many cases, access to the supervisor.

Even assuming that the supervisor runs the ex ante authorization without any bias, it is unclear how it would apply conduct rules ex post. Regulatory rules are considered public law rules for enforcement purposes. This means that, unlike private law rules, their breach entails public enforcement action, which curtails the possibility of constructing rules that regulate the parties’ duties flexibly, or imply duties not expressly contemplated in the law.

In addition to enforcement action by supervisors there is also the possibility that the rules are interpreted by civil courts. However, the more specific and self-contained the regulatory rules are, the more difficult it will be for the judge to draw an analogy with the broader laws of ‘fiduciary transactions’ or ‘mandate contracts’. Regulatory rules provide a more certain answer to the contingencies envisaged in those rules, but may leave great uncertainty in the face of unforeseen contingencies.

Furthermore, some rules may actually require classification of the relationship pursuant to private law rules. Insolvency rules, which are the flip side of segregation rules under property rights, normally require that the right of the parties (in this case, the customers) belongs to one of the categories of property/security rights, or, generically, in rem rights to dispense enhanced protection upon the insolvency of the Provider. Absent a smooth connection between regulatory rules and private law rules the insolvency court may well conclude that, although the parties’ arrangement was regulated by financial provisions, it did not fulfil the requirements under private law to be granted segregation protection.Footnote 111

A country could, of course, introduce safe-harbor rules that expressly protect customer funds without specifying under what private law arrangement they are considered protected. But this would raise uncomfortable questions, if, for example, a Provider identified and ring-fenced the funds, but did not fulfil all formal requirements (under regulatory provisions or private law). In that case, should the court rely on substance, and conclude that customers deserve protection, or on formal requirements under regulatory provisions, and leave customers unprotected? Regulatory provisions do not come with clear guidance for hard cases, and introducing specific insolvency provisions without relying on existing private law categories is not a sound long-term strategy. Insolvency courts should be able to make sense of all provisions taken together, and the more exceptions that exist without clear justification, the more sophisticated the courts need to be.

A regulatory approach constitutes a fundamental step towards ascertaining the Provider/custodian duties in e-money services.Footnote 112 We argue that to be really effective, such rules should be seamlessly connected with private law institutions and contract provisions. Otherwise, they will (a) fail to address new situations, thereby requiring new reforms at best, or leading to the ossification of the system at worst; and (b) introduce restrictions on competition between different e-money models. This is especially true if financial rules introduce a bank-bias, which can place the MNO-led model in a particularly precarious position.

Given this conclusion there is no reason for us to stop at regulatory provisions when analysing the ‘certainty versus rigidity’ dimension. All rules, both public and private, can be subject to the same scrutiny. Under this premise what matters is how easily the legal rules and institutions can fit together, and be used as ‘building blocks’ to give support to e-money. The issue is not qualitatively different from the interoperability of technologies: if legal rules are compatible, network effects are enhanced and the value of the network increases.

In a context of great uncertainty, it may make sense for the law to ‘standardize’ some options, especially in the initial stages, but policymakers should be aware of the costs of standardization, leave room for competition, and enhance network effects by allowing different models (based on different institutional structures) to operate with each other.

Cross-border payments, in particular, can only occur if protocols and standards (including legal standards) are compatible. Obstacles to this will exist if, for example, the rules that grant protection to customer funds require (a) the Provider to be a certain type of entity, or be authorized by the domestic regulator; (b) the Provider to employ a specific private law mechanism to safeguard funds; or (c) the Provider to have the assets subject to custody arrangements under the laws of the country.

This requires a second closer look at the use of fiduciary transactions. Many civil law countries, despite contemplating the fiducia as a private law institution, introduce the requirement that only financial institutions can be fiduciaries.Footnote 113 This makes the fiduciary approach half-regulatory, half-private law. It also means that ensuring fund isolation in e-money in those countries will be difficult unless a financial institution is enlisted into the scheme. This poses problems for the MNO-led model. If the law requires the fiduciary to be a financial institution the options are to (a) not use the fiduciary transaction, in which case the protection of funds via a deposit/loan would be precarious in case of the Provider's insolvency; or (b) rely on fiduciary transactions involving a financial institution, in which case there would be a problem with the characterization of the Provider's role. Should the provider be the beneficiary, or only the agent subscribing fiduciary contracts on behalf of customers?

In this second case, problems can arise with the compatibility of the laws of fiduciary transactions and the laws of mandate. If laws on fiduciary transactions are not flexible, and contemplate a direct fiduciary relationship between the fiduciary (the bank) and the beneficiary, and the Provider adopts the role of an agent, the protection of that Provider's position would be weak. This would impair the model of MNO-as-Provider and contribute to the ‘bankarization’ of e-money.Footnote 114 However, if the Provider acts as the beneficiary, customers would be protected in the event of the bank's insolvency, but not that of the Provider. Thus, restricting the role of the fiduciary to a subset of institutions is not a good idea if the goal is to promote compatibility of rules and competition. To promote safety it would be better to legislate safekeeping characteristics that the fiduciary needs to fulfil, and the contents of the duty to account.

Even if a country does not restrict the fiduciary's role to financial institutions other rigidities can exist. Patrimonial separation may make it easy to insulate the funds, but make it more difficult to grant customers rights over them.Footnote 115 Also, the introduction of fiduciary transactions via statutory reform is an important first step, but does not automatically create the body of principles that serve as background criteria for hard cases. If the principles underlying such rules are not completely clear, judges may search for solutions in adjacent property/security rights, such as the pledge, which may be unsuitable for mobile e-money purposes.

The issue can be even more complex in a cross-border context. Customers seeking protection of their funds in a scenario where the fiduciary is located outside their territory may need, as a prior step, the recognition of patrimonial separation by the laws of a country different from the laws of the country under which the rights were created. Some institutions, like the mandate, are flexible enough, and widespread enough, to enjoy cross-border recognition (it should not be difficult for the courts of one country to recognize a foreign entity as the agent of a customer located in their territory).

But fiduciary transactions are something new and, arguably, an exception. Thus, the question is whether, by enacting statutory provisions that regulate fiduciary transactions a jurisdiction is committed to give recognition to fiduciary transactions created under the laws of a different country, which may entail different rights and duties. A court confronted with a request for the recognition of the patrimonial separation resulting from a fiduciary transaction subject to foreign law may (a) adopt a pragmatic stance, and acknowledge every transaction that is validated as such by a registry entry or legal opinion in the foreign country; (b) rely on the nomen iuris, and recognize it if it is denominated as fiducia or something similar; or (c) subject it to a test of functional equivalence (to see if all the elements considered relevant by its domestic law are present). If the recognition is sought in a country that does not recognize fiduciary transactions under its domestic law, the problem may be even more difficult. The Hague Trusts Convention was supposed to resolve these cross-border problems but has been ratified by few States.Footnote 116

Thus, the suitability of fiduciary transactions should not allow us to overlook the associated rigidities. Such rigidities will be present not only in the extreme case where the Provider goes insolvent, but also in cases where the customer wants to make its e-money units ‘portable’, or usable in different countries. Fund protection should be the same across borders, and not lose strength with every degree of separation. Thus, the legal device employed needs to be carefully considered when building the ‘infrastructure’ for fund safeguarding and fund management between Providers and banks beyond the specific agreement between customers and Providers.

C. Other Variables Shaping Regulation of E-money: Supervisory Capacity and Customers’ Vulnerability

In considering strategies to implement e-money systems within their territory lawmakers should be aware of the different legal mechanisms that serve as alternatives (see Section III). They should also place those legal mechanisms within a wider regulatory context and be aware of how different rules interact to enhance certainty and to avoid hindering competition (see Section IVA). In this final subsection, we explore other variables that will shape the capacity of policymakers to regulate e-money: supervisory resources (1) and customers’ vulnerability and ability to discern between options (2).

1. Supervisory capacity

The first of these restrictions is of great importance to assess the feasibility of certain models. Where resources are constrained, regulators may want to consider ex ante supervision through licensing, as well as off-site supervision through reports, licensing/authorizations,Footnote 117 or the possibility of supervisory authorities effectively ‘delegating’ some of their supervisory duties to the private sector. Enhanced supervision models, which rely on the active ex post monitoring of the Providers’ performance duties, require more resources. The possibility of public institutions’ direct provision of some of the services, such as the management of the accounts, may also need to be evaluated on this basis.

2. Customers’ vulnerability

Although some of the mechanisms examined herein provide fund isolation protection, regard must be given to the situation and vulnerability of customers in each case. If e-money services are regulated as a fiduciary contract, the effective protection of customers’ funds may be subject to customers’ ability to recover their funds quickly and inexpensively. The fact that many customers live in rural areas and without easy access to technology could hinder effective protection.

Additionally, delays in insolvency proceedings and the associated high legal costs can critically weaken the effectiveness of fund isolation protection. It is important for legislatures to explore not only whether customers have an insolvency protection, but whether customer funds can be separated from the insolvent estate.

V. CONCLUSION

The mobile money industry is growing quickly and has the potential to improve the lives of many people in developing countries. As the industry develops, the need to protect customers’ funds becomes more acute, particularly given the vulnerability of a great proportion of e-money customers.

In Section II we saw that trust law may effectively protect e-money customers’ funds in common law jurisdictions. In civil law jurisdictions, however, there are no such clear-cut solutions. To facilitate the inquiry we identified three necessary functions that a legal instrument should fulfil to protect customers’ funds effectively: a) fund isolation; b) fund safeguarding; and c) protection of customers’ interests against operational risks.

Section III demonstrates that the civil law division between Law of Obligations and Law of Property creates important challenges in the quest for a viable alternative to the trust. Proprietary alternatives, such as the law of fiduciary transactions, could provide deficient protection against liquidity and operational risks because some jurisdictions do not adequately regulate fiduciary duties. At the same time, while obligational/contractual alternatives such as the mandate contract do provide a sound regulation of fiduciary duties, they do not provide effective fund isolation. Policymakers may feel tempted to resort to regulation to bridge the gaps between the two mechanisms, or even to rely on insurance as a fall-back option. However, there are important drawbacks to these direct interventions.

Section IV uses these conclusions to elaborate a broader menu of policy choices. The ideal private law structure would combine fiduciary transactions and mandates by cross-referencing the regimes in statute, or using both mechanisms to fulfil different functions. Specific regulatory intervention could also define the Provider's duties more specifically. The advantages of regulatory intervention, however, should be weighed against its rigidities. Policymakers should give careful consideration to the interaction of new regulation with existing statutes and private law rules: by enhancing certainty through direct intervention regulators could impose a specific model of mobile money services that could hinder competition and cross-border recognition. Finally, issues of regulatory capacity and customer vulnerability should be borne in mind in planning the transition from early to more advanced stages of implementation of e-money.