Distinctions into in-groups and out-groups are a universal feature of human societies. Humans display in-group favoritism, which supports cooperation and successful collective action, and out-group prejudice, which often triggers conflict and violence. Yet classifications of others into in- and out-groups are not fixed, but change over time and across contexts. A long tradition in the social sciences studies the forces driving out-group prejudice (Allport Reference Allport1954; Blumer Reference Blumer1958) and changes in social group boundaries (Barth Reference Barth1969), usually focusing on the interaction between two groups. Significantly less work exists that generalizes the focus to multigroup relations in diverse societies.

In this paper, we attempt to fill this gap by studying the effects of immigration on intergroup relations in a society with multiple minorities. While the effects of immigration have received much attention, we know relatively little about how immigrants affect natives’ views of racial or other minority groups. Extant work suggests that the size and characteristics of one minority group can change how majority members view other minorities, but the direction of this effect remains indeterminate. On the one hand, new groups may divert natives’ prejudice from existing excluded minorities. On the other, attitudes can be driven by generalized ethnocentrism, with all culturally distant groups being lumped together in the minds of natives (Kinder and Kam Reference Kinder and Kam2010).

We propose a framework that accommodates both possibilities and predicts when and how attitudes toward existing minorities change in response to the arrival of new groups. Building on self-categorization theory in social psychology (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987; Reference Turner, Oakes, Haslam and McGarty1994), we hypothesize that individuals categorize others as in- or out-group members based on shared attributes. We introduce the concept of affective distance as a primary determinant of which attributes will emerge as relevant for social categorization. Affective distance is a summary term for an individual’s feelings toward members of different groups relative to their own in-group. Like social status, it captures a group’s relative perceived quality or value (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986).

In our framework, an increase in the size of one group changes the way the majority classifies other groups, depending on the combination of group size, affective distance, and shared attributes. Existing out-groups are reclassified as in-groups, and viewed more positively, when they differ from the growing group in terms of key attributes that distinguish the latter from the majority and when their affective distance from the majority is lower relative to that of the growing group.

We provide evidence consistent with this theoretical framework in the context of the United States by investigating the influence of Mexican immigration on whites’ attitudes toward Blacks. We combine census demographic data between 1970 and 2010 with survey data on attitudes toward various minority groups from the American National Election Study (ANES), the General Social Survey, the Cooperative Elections Study and with data on hate crimes from the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Uniform Crime Reporting system.

We implement a difference-in-differences design that leverages changes in Mexican immigration across states over time, accounting for states’ time-invariant characteristics and for time-variant factors that affect all states within the same census division. To assuage remaining endogeneity concerns, we predict Mexican immigration exploiting the distribution of ethnic enclaves across states in 1960. This strategy builds on the empirical regularity that immigrants tend to locate in areas with an extant immigrant network. We perform several checks to support the identifying assumption that time-varying unobservables correlated with 1960 Mexican shares are not the crucial driver of changes in racial attitudes.

Using this empirical design, we find that Mexican immigration substantively reduces anti-Black prejudice among whites. The increase in the share of Mexican immigrants experienced by the average US state between 1970 and 2010 can explain up to 55% of the increase in feelings of warmth (as captured by a feeling thermometer) expressed by whites toward Blacks during the same period. Attitudinal changes among whites have implications for racial policy preferences, which become significantly more liberal in states that receive more Mexican immigrants. These changes are specific to government interventions that promote Black–white equality, and are not driven by a general increase in liberal ideology. Whites’ attitudes toward Hispanics deteriorate with increasing shares of Mexican immigrants, suggesting that whites become more positive toward Blacks, but not more tolerant of minorities in general. These findings hold regardless of the contextual unit used to measure Mexican group size—from state to county to census tract—and across a number of different attitudinal surveys. Attitudinal changes are reflected in behavioral patterns, with anti-Black hate crimes registering a larger drop in counties that receive more Mexican immigrants.

Interpreted through the lens of our theoretical framework, Mexican immigration improves attitudes and behaviors of native-born whites toward Blacks because Mexicans have a higher affective distance from whites than do Blacks. Consistent with this hypothesis, using the feeling thermometer in the ANES as a proxy of affective distance, we show that whites have cooler feelings toward Hispanics than toward Blacks for every single survey year between 1980 and 2010.

The data allow us to test three additional implications of the theory. First, the inflow of relatively more distant groups (in our case, Mexican immigrants) increases the salience of attributes along which those groups display maximal difference from the majority (immigration status instead of race). Consistent with this prediction, white respondents in states experiencing a larger increase in the share of Mexicans become more likely to mention immigration policies and less likely to mention race relations as the country’s most important problem.

Second, prejudice against Blacks decreases the most for whites whose baseline views of Hispanics are particularly negative relative to their views of Blacks. In support of this prediction, the effects of Mexican immigration on attitudes toward Blacks are larger in states with larger baseline (i.e., preimmigration) differences in thermometer ratings between Mexicans and Blacks.

Third, our theory delivers general predictions for how increases in one immigrant group’s size will affect whites’ attitudes toward any other minority group. The direction of effects depends on the relative affective distance of the growing immigrant group and on whether other groups are classified as out-groups based on race or immigrant status. Consistent with this, inflows of distant groups (such as Hispanics or Arabs) increase the salience of immigration and negatively affect attitudes toward other groups perceived as foreign (such as Asians). Inflows of less distant groups (such as Asians), if anything, reduce the salience of immigrant status as a relevant group boundary.

We complement our analysis with an original survey experiment designed to provide direct evidence that the improvement of whites’ attitudes toward Blacks results from recategorization. White respondents primed with the size of the Hispanic population in the US express warmer feelings toward Blacks and hold less stereotypical views of them, confirming our observational findings on the effects of changes in Hispanic population. Crucially, primed respondents also become more likely to view Blacks as “American,” consistent with our hypothesized recategorization mechanism.

Our study contributes to four strands of literature. First and most broadly, the fluid nature of group boundaries in multiethnic and multiracial societies has been extensively studied by scholars in both comparative and American politics. To factors like group mixing and shifting self-identification (Davenport Reference Davenport2018; Reference Davenport2020), instrumental identity choices (Laitin Reference Laitin1995; Posner Reference Posner2005), we add a new theoretical channel through which group categories can change, that of context-dependent classification based on relative distances between groups. Our framework formalizes insights from social identity theory and is close in spirit to Shayo (Reference Shayo2009), but our focus and empirical application are on how individuals classify others rather than on how they view themselves.

Second, we contribute to the literature on racial and ethnic politics in the US context. A majority of works in that literature focus on Black–white relations (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Bobo Reference Bobo1983; Glaser Reference Glaser1994; Kinder and Mendelberg Reference Kinder and Mendelberg1995; Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears2005), with a smaller but growing set of studies examining interminority relations (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Gay Reference Gay2006; Hutchings and Wong Reference Hutchings and Wong2014; Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Carter, Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally, Scotto, Kendrick, Lackey and Cotton2006; Reference McClain, Lyle, Carter, DeFrancesco Soto, Lackey, Cotton, Nunnally, Scotto, Jeffrey, Grynaviski and Kendrick2007; Meier et al. Reference Meier, McClain, Polinard and Wrinkle2004; Oliver and Wong Reference Oliver and Wong2003; Roth and Kim Reference Roth and Kim2013). Less attention has been paid to the role that other minorities play in affecting whites’ attitudes toward African Americans. One notable exception is Abascal (Reference Abascal2015), who finds that whites primed with Hispanic growth are less likely to allocate money to Blacks in a dictator game. Our findings suggest the opposite effect is possible, though the direction of the final outcome depends on whites’ baseline relative views of different out-groups. Our paper provides new evidence that the increase in the numbers of immigrant minorities may ameliorate white Americans’ prejudice toward Black Americans and identify conditions under which this is likely to happen.

Third, our study contributes to a large literature in the social sciences studying the effects of minority group size on majority prejudice starting with Blumer (Reference Blumer1958) and Blalock (Reference Blalock1967). We add to this literature in two ways. First, we emphasize the importance of affective distance as a factor that determines majority reactions to minority inflows jointly with group size. Our results indicate that increases in size alone are unlikely to affect prejudice when groups are relatively close to the majority in terms of affective distance. This is consistent with existing observations that certain immigrant groups are more likely to trigger perceptions of threat than others (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Ha Reference Ha2010; Newman and Velez Reference Newman and Velez2014). Second, most of the literature examines how increases in the size of a group affect the majority’s views toward that group. We instead shift the focus to the majority’s views toward other minorities and thus to the broader implications of growing minority size in a multigroup society. In this respect, we also add to a small set of studies examining cross-group spillovers of attitudes.Footnote 1

Finally, our study addresses the politics of immigration. To date, much of this research focuses on the effects of immigration on native backlash and anti-immigrant sentiment (see Hainmueller and Hopkins [Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014] for a review). We examine instead how immigration of one group shifts native-born individuals’ attitudes toward other minority groups. In work closely related to ours, Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2010) finds that the anti-Muslim rhetoric that followed September 11 triggered backlash against all immigrant groups. Our study places this finding in a broader context by showing that spillovers of attitudes from one minority to others can be positive or negative, depending on groups’ relative perceived distances from the majority.

Conceptual Framework

We rely on self-categorization theory (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987; Reference Turner, Oakes, Haslam and McGarty1994), which studies how individuals classify themselves and others into in- and out-groups. Such categorization has tangible implications because prejudice is higher toward members of the out-group (see, for example, Bernhard, Fischbacher, and Fehr Reference Bernhard, Fischbacher and Fehr2006; Duckitt Reference Duckitt1994; Shayo Reference Shayo2020). Social categorization takes place on the basis of shared attributes. The more attributes are shared by two individuals, the more likely it is that one categorizes the other as member of their in-group. Because people have multiple attributes and share similarities in some but not in others, the relevant question is which attributes determine social categorization.

Self-categorization theory posits that this is context-dependent. The same person can be classified as a member of the in-group or the out-group, depending on with whom they are compared. This concept is known as comparative fit (McGarty Reference McGarty1999). More precisely, classification is assumed to follow the rule of maximization of the meta-contrast ratio, defined as the ratio of across-category differences over within-category differences (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987, 47). Intuitively, this implies that humans form categories of stimuli, so that within-category differences are small (i.e., a given category is sufficiently homogeneous) and across-category differences are large (i.e., categories are sufficiently different from each other). Experimental evidence suggests that humans do follow such a heuristic for categorization (Tajfel and Wilkes Reference Tajfel and Wilkes1963; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987).

To capture relevant differences between individuals, we use a summary measure, which we term affective distance. Affect is a heuristic of decision making (Zajonc Reference Zajonc1980) based on an emotional response. Affective distance from a person or a group of people can be driven by many factors, such as the group’s perceived competence or quality or the degree to which it is perceived to be threatening or in competition with the in-group (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986).

Formally, consider the set I of individuals within an area. Each

![]() $ i\in I $

is characterized by a vector of J binary attributes. Denote by

$ i\in I $

is characterized by a vector of J binary attributes. Denote by

![]() $ {\delta}^i $

each individual’s affective distance from the in-group and by

$ {\delta}^i $

each individual’s affective distance from the in-group and by

![]() $ {I}_j^i $

an indicator equal to 1 if individual i differs from the in-group along the

$ {I}_j^i $

an indicator equal to 1 if individual i differs from the in-group along the

![]() $ {j}^{th} $

attribute. Then, the attribute used by each individual to categorize others into in- and out-group solves

$ {j}^{th} $

attribute. Then, the attribute used by each individual to categorize others into in- and out-group solves

$$ \underset{j}{\max }{R}_j=\frac{\frac{\underset{i}{\Sigma}{\delta}^i{I}_j^i}{\underset{i}{\Sigma}{I}_j^i}}{\frac{\underset{i}{\Sigma}{\delta}^i\left(1-{I}_j^i\right)}{\underset{i}{\Sigma}\left(1-{I}_j^i\right)}}, $$

$$ \underset{j}{\max }{R}_j=\frac{\frac{\underset{i}{\Sigma}{\delta}^i{I}_j^i}{\underset{i}{\Sigma}{I}_j^i}}{\frac{\underset{i}{\Sigma}{\delta}^i\left(1-{I}_j^i\right)}{\underset{i}{\Sigma}\left(1-{I}_j^i\right)}}, $$

where Rj is the meta-contrast ratio for attribute j; Rj can be thought of as the salience of attribute j for in-group–out-group distinctions.

Defining a group k as the set of individuals with common attributes, we can rewrite the above problem in terms of group-level categorization for K groups:

$$ \underset{j}{\max }{R}_j=\frac{\frac{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{\delta}^k{n}^k{I}_j^k}{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{n}^k{I}_j^k}}{\frac{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{\delta}^k{n}^k\left(1-{I}_j^k\right)}{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{n}^k\left(1-{I}_j^k\right)}}, $$

$$ \underset{j}{\max }{R}_j=\frac{\frac{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{\delta}^k{n}^k{I}_j^k}{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{n}^k{I}_j^k}}{\frac{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{\delta}^k{n}^k\left(1-{I}_j^k\right)}{\underset{k\in K}{\Sigma}{n}^k\left(1-{I}_j^k\right)}}, $$

where

![]() $ {\delta}^k $

denotes the average affective distance of members of group k from the in-group and nk

is the size of group k. The numerator is a weighted average of affective distances across all out-groups

$ {\delta}^k $

denotes the average affective distance of members of group k from the in-group and nk

is the size of group k. The numerator is a weighted average of affective distances across all out-groups

![]() $ k\hskip1.5pt \in \hskip1.5pt K $

, with the weights corresponding to each group’s relative size. The denominator is a weighted average of affective distances across all in-groups

$ k\hskip1.5pt \in \hskip1.5pt K $

, with the weights corresponding to each group’s relative size. The denominator is a weighted average of affective distances across all in-groups

![]() $ k\hskip1.5pt \in \hskip1.5pt K $

. Maximization thus implies choosing the attribute that makes the out-group most different and the in-group most similar in terms of affective distance. Section A in the Online Appendix provides a concrete example of how this classification rule operates in the case of three groups (white Americans, Black Americans, and Mexican immigrants) and two attributes (nativity and race) that we focus on in the empirical part of the paper.

$ k\hskip1.5pt \in \hskip1.5pt K $

. Maximization thus implies choosing the attribute that makes the out-group most different and the in-group most similar in terms of affective distance. Section A in the Online Appendix provides a concrete example of how this classification rule operates in the case of three groups (white Americans, Black Americans, and Mexican immigrants) and two attributes (nativity and race) that we focus on in the empirical part of the paper.

Equation 1 makes clear that both relative size and affective distance matter for categorization. We derive testable predictions for the effects of increasing size of a group of given affective distance on the salience of different attributes determining in-group–out-group divisions and on the categorization of other groups.

Specifically, consider a group l with

![]() $ {I}_m^l=1 $

,

$ {I}_m^l=1 $

,

![]() $ {I}_j^l=0 $

, and

$ {I}_j^l=0 $

, and

![]() $ {\delta}^l>0 $

. The above formula implies the following results:

$ {\delta}^l>0 $

. The above formula implies the following results:

Prediction 1 (Salience).

A large enough increase in the size of group l increases the salience of attribute m and decreases the salience of attribute j as long as

![]() $ {\delta}^l>{\delta}^k $

for all k∈K\l.

$ {\delta}^l>{\delta}^k $

for all k∈K\l.

This follows directly from the fact that

![]() $ \frac{\partial {R}_m}{\partial {n}^l}>0. $

Intuitively, an increase in the size of a group distant in terms of affect shifts the basis of social categorization to the attribute along which that group differs from the in-group. When an immigrant group that is perceived as distant or threatening grows in size, immigrant status becomes the salient cleavage in a society.

$ \frac{\partial {R}_m}{\partial {n}^l}>0. $

Intuitively, an increase in the size of a group distant in terms of affect shifts the basis of social categorization to the attribute along which that group differs from the in-group. When an immigrant group that is perceived as distant or threatening grows in size, immigrant status becomes the salient cleavage in a society.

This implies the following for other groups in the society.

Prediction 2 (Recategorization).

(a) For any group k with

![]() $ {I}_m^k=0 $

and

$ {I}_m^k=0 $

and

![]() $ {I}_j^k=1 $

that is categorized as out-group, a large enough increase in the size of group l leads to recategorization if

$ {I}_j^k=1 $

that is categorized as out-group, a large enough increase in the size of group l leads to recategorization if

![]() $ {\delta}^l>{\delta}^k $

. The threshold for recategorization is decreasing in the difference

$ {\delta}^l>{\delta}^k $

. The threshold for recategorization is decreasing in the difference

![]() $ {\delta}^l-{\delta}^k $

.

$ {\delta}^l-{\delta}^k $

.

(b) Consider a group k with

![]() $ {I}_m^k=1 $

and

$ {I}_m^k=1 $

and

![]() $ {I}_j^k=0 $

, where j solves Equation 1 so that group k is categorized as in-group. Then a large enough increase in the size of group l leads to recategorization if

$ {I}_j^k=0 $

, where j solves Equation 1 so that group k is categorized as in-group. Then a large enough increase in the size of group l leads to recategorization if

![]() $ {\delta}^l>\overline{\delta_j} $

, where

$ {\delta}^l>\overline{\delta_j} $

, where

![]() $ \overline{\delta_j} $

is the numerator of

$ \overline{\delta_j} $

is the numerator of

![]() $ {R}_j $

.

$ {R}_j $

.

(c) Consider a group k with

![]() $ {I}_m^k=1 $

and

$ {I}_m^k=1 $

and

![]() $ {I}_j^k=0 $

, where m solves Equation 1 so that group k is categorized as out-group. Then a large enough increase in the size of group l leads to recategorization if

$ {I}_j^k=0 $

, where m solves Equation 1 so that group k is categorized as out-group. Then a large enough increase in the size of group l leads to recategorization if

![]() $ {\delta}^l<\overline{\delta_j} $

, where

$ {\delta}^l<\overline{\delta_j} $

, where

![]() $ \overline{\delta_j} $

is the numerator of

$ \overline{\delta_j} $

is the numerator of

![]() $ {R}_j $

.

$ {R}_j $

.

Part (a) of Prediction 2 follows directly from Prediction 1 and the fact that, when the increase in nl is large enough, Rm becomes larger than Rj and attribute m arises as the determinant of classification into in- and out-group. Intuitively, an increase in the size of an out-group of high affective distance draws the majority’s attention to the attribute that distinguishes that group from the majority and away from other attributes. The differences between majority and groups previously classified as out-groups based on attribute j are thus de-emphasized. This leads to recategorization of existing minorities from out- to in-group status. In the case of immigration and race, an increase in the salience of immigrant status reduces the importance of skin color as a group classifier and thus reduces prejudice of whites against Blacks.

It follows from 2(a) that an increase in the size of an out-group can accentuate existing dimensions of difference between the majority and other out-groups when that group is of lower affective distance to the majority than existing out-groups. When an expanding group is perceived as less threatening than other groups (e.g., Asian immigrants), its comparison with racial minorities does not decrease, and may even increase, prejudice against the latter.

Parts (b) and (c) of Prediction 2 concern groups that share relevant attributes with the group that is growing in size. When affective distance of the growing group is high, and attention is drawn to attributes distinguishing that group from the majority, other groups may see a change in their classification from in- to out-groups if they share said attributes. Conversely, if affective distance is low, groups categorized as out-groups based on the distinguishing attribute of the growing group may find themselves recategorized as in-groups.

Context and Group Size

What is the relevant spatial unit for measuring group size nk ? Extant theory provides only partial guidance to answering this question. The answer depends on the perceptions of group size formed by in-group members (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Bowers, Williams and Simmons2012). Yet it is not clear which spatial unit individuals consider when forming relevant perceptions. When asked to estimate group size in their local community, individuals provide estimates that are best predicted by size at the level of the zip code (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Velez, Hartman and Bankert2015; Velez and Wong Reference Velez and Wong2017). However, people might not always think about their local community or real-life exposure to a racial or ethnic group when assessing its size. Social and informational environments—such as traditional and social media—may be equally important in influencing people’s perceptions. Such forces operate at larger scales, such as media markets, states, or even at the national level (Huckfeldt and Sprague Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995).

Regardless of the relevant context for perception formation, recategorization is more likely to happen when the group growing in size is further away from the in-group in terms of affective distance. To the extent that affective distance reflects threat, it is likely to peak at larger contextual units, like the metropolitan statistical area or the state (Ha Reference Ha2010; Oliver and Wong Reference Oliver and Wong2003; Tam Cho and Baer Reference Cho, Wendy and Baer2011). Several studies in the social sciences suggest that perceptions of threat in response to diversity are maximized at units equal to or larger than 500,000 people, with little variation in effects by population size once that threshold is reached (Kaufmann and Goodwin Reference Kaufmann and Goodwin2018). Instead, effects of positive intergroup contact are more prevalent among studies that examine lower levels of aggregation closer to the neighborhood (Ha Reference Ha2010; Tam Cho and Baer Reference Cho, Wendy and Baer2011).Footnote 2

Given this discussion, we expect stronger recategorization at larger levels of aggregation, where growing groups are more likely to be perceived as affectively distant and where size perceptions are influenced by media and social environments likely to further heighten perceptions of threat (Massey and Pren Reference Massey and Pren2012; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). Yet, the mechanism we posit should operate also at lower levels of aggregation. As long as the distance of a group is larger than that of existing out-groups, increases in its size at any spatial unit relevant for people’s perceptions should lead to recategorization of other groups. In our empirical analysis, we focus on the state level, but we also evaluate effects at different contextual units, from the county to the census tract.

Data and Empirical Strategy

Data

We construct a state-level panel of Mexican and overall immigration using data from the US census (Ruggles et al. Reference Ruggles, Flood, Goeken, Grover and Meyer2019) for each decade between 1970 and 2010. Given census data availability, and for the demographic data to closely match the instrument for predicted immigration introduced below, we focus only on the foreign-born and not the population of second-generation immigrants.

We complement these data with state-level demographic characteristics (Manson et al. Reference Manson, Schroeder, Van Riper and Ruggles2019; Ruggles et al. Reference Ruggles, Flood, Goeken, Grover and Meyer2019). To assess whether immigrant inflows from Mexico affect whites’ attitudes, we rely on survey data from the ANES (2015). The ANES is an academically run nationally representative public opinion survey conducted every two or four years since 1948. We focus primarily on attitudes toward African Americans, but we also examine attitudes toward Hispanics and Asian Americans when investigating the mechanisms behind our main results. Because the data on immigrant population are decadal but the ANES is conducted every two years until 2000, and every four years thereafter, we map immigration to survey responses in the years closest to and centered around the year when immigrant numbers were recorded. For example, the 1980 Mexican share is mapped to survey responses in 1978, 1980, and 1982.

We use two measures of whites’ racial attitudes. The first one is the feeling thermometer. The scale of responses ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating warmer feelings. The feeling thermometer has the advantage of having been consistently asked over time throughout our period of study. We construct a second measure of attitudes by combining the feeling thermometer with variables capturing stereotypical views of Blacks. Specifically, we focus on whether the respondent believes that Blacks are hard-working, intelligent, violent, or trustworthy (items coded on a 1 to 7 scale). We recode all items so that higher values indicate lower prejudice and create an index out of all standardized items (including the feeling thermometers) to reduce noise and avoid multiple hypothesis testing. We construct similar measures for Hispanics and Asian Americans.

We focus on the state level because this is a relevant unit of analysis from a theoretical standpoint and because it presents a number of empirical advantages. First, county level ANES data are sparser, and the repeated cross-section of counties that one can follow over time is not nationally representative. Second, selective migration of whites in response to Mexican immigration, which is a likely confounder of any estimates of immigration on attitudes, is significantly less pronounced at the state level than at the level of smaller spatial units. Finally, as explained in more detail in the next section, the instrument for Mexican immigration relies on the initial distribution of Mexican enclaves prior to the change in the immigration regime in 1965. This information is accurate and complete at the state level but not at lower levels of aggregation. Despite these empirical shortcomings, we show that our results are unchanged at the county and census tract levels. We present these data as they become relevant.

Table B.1 in the Online Appendix presents summary statistics for all variables used in our analyses. The exact wording and years of availability of ANES survey questions are reported in Tables B.2 and B.3 in a detailed appendix available with replication materials.

Empirical Strategy

We start from a generalized difference-in-differences design. We compare changes in racial attitudes across states experiencing differential changes in the fraction of Mexican immigrants over time, absorbing any time-invariant state and any time-varying census division characteristics.

Focusing on white respondents, we estimate

where Mrst is the fraction of the total population that is born in Mexico in census division r and state s in time t. The main parameter of interest, β 1, captures the influence of Mexican immigration on attitude Yirts for individual I; γrs and μrt represent state and decade by census division fixed effects. Their inclusion implies that β 1 is estimated from changes in Mexican immigration within a state over time as compared with other states within the same division in the same decade. To account for the potential correlation between Mexican and overall immigration to the US, we control for Srst —the share of (non-Mexican) immigrants in a state and decade. Finally, we control for a set of baseline individual-level characteristics (age, age squared, and gender) collected in the vector Xirst. We cluster standard errors at the state level.

This approach differences out all time-invariant unobservable characteristics of states that could affect both immigrant location choices and racial prejudice. However, local time-varying factors may still be influencing both immigrants’ settlements and the social integration of minorities. To overcome these concerns, we predict the number of Mexican immigrants settling in a given state over time using a version of the shift-share instrument commonly adopted in the immigration literature (Card Reference Card2001). The instrument assigns decadal immigration flows from Mexico between 1970 and 2010 to destinations within the US proportionally to the shares of Mexican immigrants who had settled there in 1960, prior to the change in the immigration regime introduced in 1965. We predict the number of non-Mexican immigrants using a similar approach and averaging across immigrant origin countries. Details on the construction of the instrument are provided in Section C of the Online Appendix. The first stage relationship, which is strong, is displayed in Figure C.1 and Table C.1.

The primary identifying assumption behind the instrument is that places that received more Mexican immigrants before 1960 are not on differential trajectories in terms of changes in whites’ attitudes or other factors correlated with the latter (Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin, and Swift Reference Goldsmith-Pinkham, Sorkin and Swift2020). We provide multiple pieces of evidence in support of this assumption.

Main Results

Affective Distance

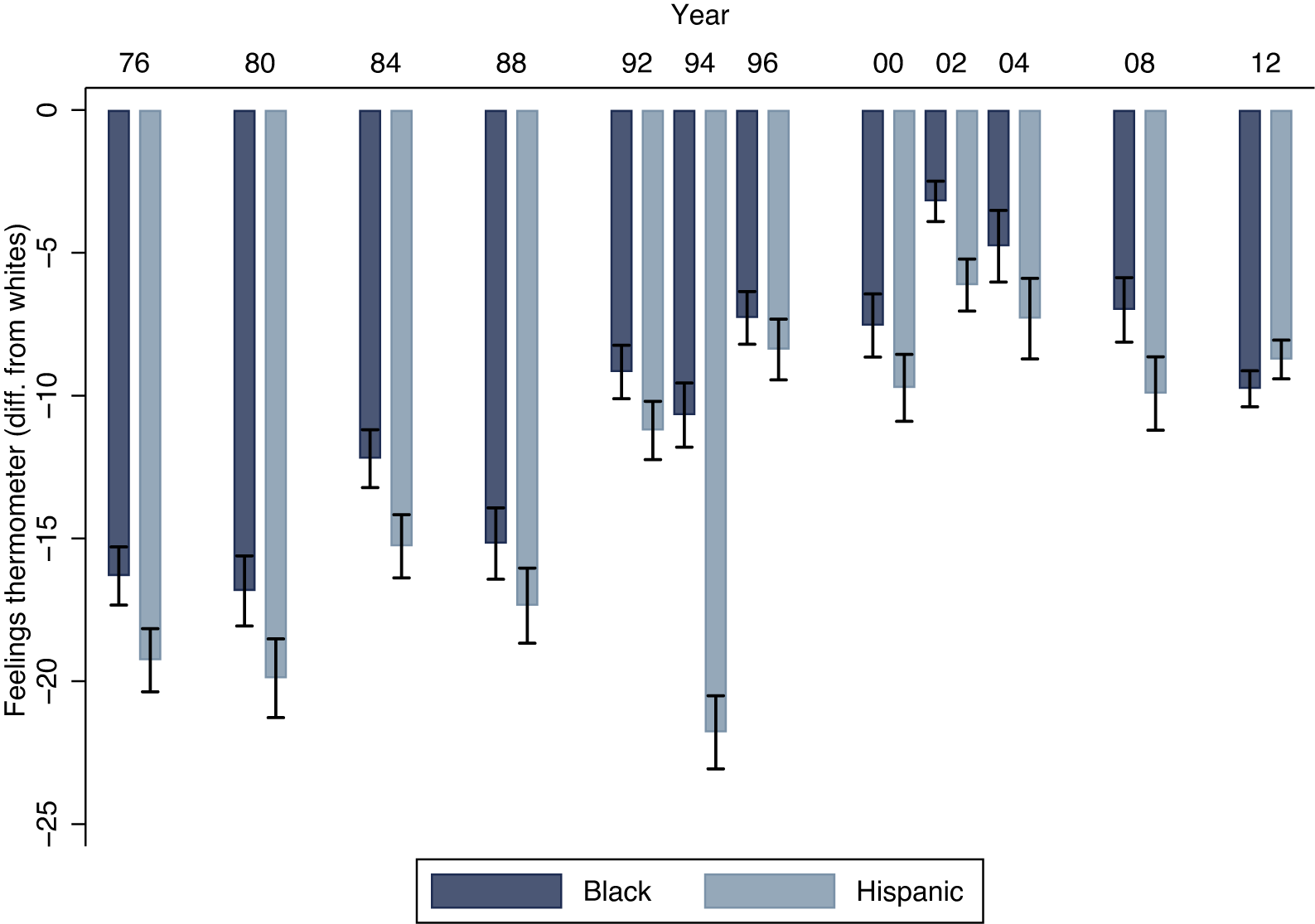

A fundamental premise in our argument is that Mexican immigrants have a higher affective distance from native whites than do Blacks. Using thermometer ratings relative to the white in-group as a measure of affective distance supports this assumption. Figure 1 plots whites’ relative thermometer ratings of Blacks and Hispanics for ANES years in which all thermometers for all three groups are available. Whites consistently express warmer feelings toward Blacks than toward Hispanics, and the differences between the two groups are always statistically significant.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Feeling Thermometer Ratings of White ANES Respondents

The high affective distance of Hispanics from whites traces its origins to the 1970s. The large influx of undocumented Mexican immigrants that followed the abrupt ending of the Bracero program was exploited by opportunistic politicians to construct a narrative around a “Latino threat” (Massey and Pren Reference Massey and Pren2012). Since that time, Hispanic immigration has captured a disproportional amount of media attention (Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013). Other factors, such as the direct proximity of Mexico to the US, have also contributed to perceptions of Mexican immigration as a unique challenge for American society and culture (Huntington Reference Huntington2004), possibly explaining the patterns in Figure 1.

Effects on Attitudes

Table 1 presents our main results. The 2SLS estimates suggest that Mexican immigration increases both the feeling thermometer (column 2) and the average of standardized whites’ racial attitudes (column 4). The OLS coefficients are negative, implying that Mexican immigrants moved to states where whites’ racial views were improving more slowly over time.Footnote 4

Table 1. Effects on Whites’ Attitudes toward Blacks

The magnitude of the estimates is substantive. A one-percentage-point increase in the Mexican share raises the Black feeling thermometer by 1.3% relative to its baseline mean. Between 1970 and 2010 the fraction of Mexicans increased, on average, by 2 percentage points. According to our estimates, this accounts for about 55% of the average increase in both the Black thermometer (2.85) and average attitudes (0.14) over the same time frame.

We conduct several checks to verify that these estimates represent causal effects, reported in detail in Section D.1 of the Online Appendix. Our results are robust to allowing states to be on differential trajectories depending on a number of 1960 characteristics potentially correlated with Mexican shares, such as racial composition or urbanization (Table D.2). Falsification tests and permutation exercises confirm that 1960 Mexican shares do not alone drive the evolution of racial attitudes we estimate (Table D.4 and Figure D.1). Our results go through after accounting for potential bias due to spatial interdependence (Table D.5), for the potential influence of outliers (Figure D.2 and Table D.6), and for serial correlation in the instrument for predicted immigration (Table D.7).

Our results are somewhat larger in states with below-median share of Blacks in 1970, but improvements in attitudes are driven primarily by states with below-median residential segregation (Table D.13). This indicates that immigration changes racial attitudes particularly for whites who are more likely to be exposed to and interact with Blacks. This heterogeneity is also consistent with our framework. States with lower segregation in 1970 may have been characterized by more positive racial attitudes among whites and thus lower affective distance between Blacks and whites at the start of our study period. This increases the likelihood of recategorization (Prediction 2(a)).

We examine whether changes in attitudes also translate into policy preferences. Ex ante, it is unclear what to expect. Policy preferences related to race are crucially shaped by factors such as political ideology and views on the role of government, which may be harder to change and orthogonal to racial attitudes. Table D.15 in the Online Appendix documents that Mexican immigration increases support for government interventions that advance racial equality, such as fair employment practices or preferential hiring. These patterns are specific to race-related policies and not part of a broader package of more liberal views spurred by immigration (Table D.16).

Can our results be explained by a broader improvement of whites’ attitudes toward minorities? In Table 2 we estimate the effects of Mexican immigration on attitudes toward Hispanics and find this to not be the case. The 2SLS estimates, reported in columns 2 and 4, indicate that Mexican immigration increases whites’ prejudice toward Hispanics.Footnote 5 These patterns are consistent with Prediction 2(b) of our theoretical framework and suggest that Mexican immigration leads whites to change the definition of the in-group so as to include Blacks and exclude Hispanics.

Table 2. Effects on Whites’ Attitudes toward Hispanics

Factors beyond recategorization, could explain our findings. In Section D.3 of the Appendix, we rule out several prominent alternatives. Changes in racial attitudes are not driven by changes in the numbers of Black or white residents (Table D.8). Using data from the 2004 ANES panel study, we provide evidence against selective out-migration of whites with more anti-Black and less anti-Hispanic attitudes (Table D.10). We show that our results are not driven by the effect of September 11 on anti-immigrant sentiment (Table D.11). We also assess the possibility, identified by prior work (Green, Strolovitch, and Wong Reference Green, Strolovitch and Wong1998; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2009; Reference Hopkins2010; Newman Reference Newman2012; Newman and Johnson Reference Newman and Johnson2012), that changes instead of levels of Mexican group size drive changes in attitudes. We do not find strong evidence that changes in group size have a larger effect on racial prejudice than size itself (Table D.12), but our identification strategy does not allow us to cleanly distinguish between the two.

A likely pathway for the results we observe is that changing political discourse or media narratives contribute to a shift in attention from race-related issues to immigration and the role of Hispanics in the US. Massey and Pren (Reference Massey and Pren2012) document an explosion of media mentions of Hispanic immigration in the period we study. Rising volume of media coverage of Hispanics could crowd out mentions of other groups, increasing perceptions of threat from the former and reducing them for the latter. We view this mechanism as consistent with our framework. Media reports are responsive to readers’ demand (Gentzkow and Shapiro Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2010), and the increased focus on Hispanics is as much a driver as it is an outcome of white Americans’ anxiety about immigrant population growth. Indeed, Valentino, Brader, and Jardina (Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013) show that media coverage of Hispanics mirrors trends of immigration from Latin America, suggesting that the media respond to real demographic changes in the US population. According to our framework, increases in the size of an immigrant group endogenously increase the salience of immigration. Increased media mentions are both a reflection of this endogenous salience and an amplifying mechanism for its effects on group recategorization and prejudice.

Local-Level Evidence

Studies on local demographics and majority attitudes frequently yield conflicting results depending on the spatial unit of analysis (Pottie-Sherman and Wilkes Reference Pottie-Sherman and Wilkes2017; Tam Cho and Baer Reference Cho, Wendy and Baer2011). To avoid aggregation bias—the “modifiable aerial unit” problem (Fotheringham and Wong Reference Fotheringham and David1991)—the literature emphasizes the importance of choosing units of analysis that closely correspond to the theoretical mechanisms analyzed (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Velez, Hartman and Bankert2015; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Bowers, Williams and Simmons2012). We argued that the state is a relevant unit for perceptions of group size, particularly those perceptions that trigger macrothreat. Yet other contextual units may be relevant for size perceptions at the local community level (Velez and Wong Reference Velez and Wong2017), and those perceptions could also affect recategorization. We investigate these possibilities empirically.

We estimate a county-level variant of Equation 2, controlling for state by decade (rather than division by decade) fixed effects. That is, we restrict comparisons to counties within the same state that experience differential increases in their Mexican populations. County-level estimates are similar to those of the state-level analysis (Table E.3 in the Online Appendix). A one-percentage-point increase in the share of Mexicans raises the feeling thermometer for Blacks by 1.1% relative to the baseline mean, very close to the 1.3% effect estimated at the state level. The effect on the summary measure of attitudes is somewhat smaller and less significant than the equivalent state-level estimate, but it still amounts to 10% of the average increase in the mean during the period of interest—a substantive effect. Attitudes toward Hispanics worsen in response to increasing Mexican group size, with the magnitude of the effect for the Hispanic thermometer corresponding to 1.3% of the baseline mean—not far from the 5.8% estimated at the state level. Similar results obtain in a county-level panel of attitudes from the General Social Survey (Table E.4). The consistency of estimates across state and county-level analyses is perhaps not surprising given that similar mechanisms may operate at both levels of aggregation (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann and Goodwin2018).

We also examine a contextual unit smaller than the county, the census tract.Footnote 6 Using data from the Cooperative Election Study between 2007 and 2018 and estimates of local demographics from the American Community Survey, we find that Mexican population size significantly reduces symbolic racism (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981) and prejudice and negatively, though not significantly, influences immigration policy preferences (Table E.6). These estimates compare census tracts within the same county, conditional on the evolution of a number of tract-level demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, thus representing particularly stringent local estimates of the effect of Mexican immigration on attitudes. Details on this analysis are provided in Section E.2 of the Online Appendix.

Taken together, our results suggest consistency of effects across spatial units. For the remainder of the analysis, we focus attention on state-level estimates that provide us empirically with the most traction to test additional empirical implications of our framework.

Testing the Mechanisms

Increase in the Salience of Immigration

As per Prediction 1, Mexican inflows lower prejudice against Blacks because they reduce the salience of race and increase that of immigrant status. We provide evidence for this mechanism by exploiting ANES responses to the question “What do you think are the most important problems facing the country?” This is an open-ended question, but the ANES reclassified the answers of respondents into broader categories. We focus on two categories that do not change over time: immigration policies and racial problems. For the latter, we can further identify the exact position the respondent takes on various racial issues and whether it indicates positive or negative attitudes toward African Americans (e.g., supports vs. opposes fair employment practices). We construct an indicator for respondents who mentioned a category as the single most important problem facing the country at the time.

Table 3 shows that Mexican immigration significantly increases the share of white respondents who mention immigration policies as the most important problem in the country. The share of respondents who mention race-related problems and place themselves in opposition to the expansion of rights for Blacks decreases (columns 3–4). Conversely, the share of those who mention race-related problems and express support for Black–white equality increases (columns 5–6). As immigration becomes a salient problem, white Americans appear to shift their attention to issues that unite Black and white Americans rather than divide them.

Table 3. Most Important Problem in the Country

Effects Increasing in the Difference of Affective Distances

Prediction 2(a) states that the effect of immigration on attitudes toward Blacks is higher the more distant immigrants are perceived to be by whites, compared with Blacks. We test this empirically by exploring heterogeneity patterns within the ANES sample.

We construct state-level averages of the difference in thermometer values between Blacks and Hispanics in 1980—the first survey decade for which attitudes on Hispanics began to be systematically collected. Larger values indicate that white respondents have warmer feelings toward Blacks than they do toward Hispanics. We then interact the effect of the share of Mexicans with this variable. Table 4 presents heterogeneous effects by baseline difference in affective distance between Blacks and Hispanics. The results indicate that a significantly larger improvement in whites’ feelings toward Blacks comes from states whose residents viewed Mexicans more coolly than Blacks in 1980 (column 2). A similar positive, though not statistically significant, interaction effect is found for average prejudice (column 4).Footnote 7

Table 4. Effects by Baseline Difference in Black–Hispanic Thermometer Ratings

Generalized Cross-Group Effects

Beyond a prediction for the effect of Mexican immigration on whites’ attitudes toward Blacks, our framework has broader implications for how the growth in the size of one group affects the majority’s attitudes toward other social groups. Prediction 2(b) implies that growth in the size of immigrant groups of higher affective distance from whites not only leads to recategorization of nonimmigrant out-groups as in-groups but also has the opposite effect on other immigrant groups, increasing prejudice against them. Furthermore, Prediction 2(c) predicts that growth in the size of immigrant groups that are less distant, in terms of affect, from whites than are Blacks, does not decrease, and may even increase, prejudice toward the latter. In this section, we provide evidence supportive of both patterns.

The left panel of Figure 2 plots the effects of the share of Mexicans on whites’ average attitudes toward different groups. The first two estimates correspond to 2SLS coefficients from Tables 1 and 2. The third estimate shows how an increase in the Mexican share affects whites’ attitudes toward Asians. Consistent with Prediction 2(b), Mexican immigration has negative effects on attitudes of whites toward groups perceived as foreign-born.

Figure 2. Cross-Group Effects by Affective Distance and Shared Attributes

Note: The figures plot 2SLS coefficient estimates and 90% confidence intervals for the effect of group size from Equation 2 for each of the groups indicated in the subplot titles. The dependent variable is the average of attitudes of white ANES respondents toward each of the groups indicated on the y-axis. Full estimates are reported in Table D.17 in the Online Appendix.

The particular effects of Mexican immigration on whites’ views of other groups result from the fact that Mexicans’ relative affective distance from whites is high. Inflows of relatively less distant groups de-emphasize immigrant status as a classifier and, if large enough, may have the effect of redirecting prejudice away from immigrants.

Next to Central and South America, Asia was the second largest immigrant-sending region during the 1970–2010 period. Figure 3 reveals that white respondents have warmer relative feelings toward Asian Americans than they do toward either Blacks or Hispanics. This lower distance can be a result of Asian Americans being on average more educated and highly skilled or perceived as less of a threat than other minorities.Footnote 8

Figure 3. Average Thermometer Ratings of White ANES Respondents

The influence of Asian immigration on whites’ attitudes toward Blacks is consistent with this ranking.Footnote 9 The middle panel of Figure 2 shows that an increase in the share of Asian immigrants has no effect on whites’ attitudes toward Blacks. Instead, effects on attitudes toward Hispanics and Asians are positive, consistent with prediction 2(c).

Finally, we examine how inflows of another group of high relative affective distance affects minority recategorization. After September 11, the ANES introduced questions on thermometer ratings of Muslims. This group’s ratings relative to whites are more negative than those of Hispanics (Figure 3).Footnote 10 In the right panel of Figure 2, we measure the Muslim (primarily Arab) share of the population as the share of people born in any of the following countries or regions, which we can identify in all decades in the census: Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Turkey, Egypt, or unspecified countries in North Africa. Arab immigration slightly improves whites’ attitudes toward Blacks and worsens those for Asians. This is consistent with recategorization operating as in the case of Hispanic immigration: increased salience of foreign-born status as a classifier leads to reclassification of immigrant groups as out-groups and racial minorities as in-groups, with divergent effects on whites’ attitudes for each type of group.Footnote 11

Micro-Level Evidence on Reclassification

The previous sections show that immigration changes whites’ attitudes, but they only test our theory indirectly by providing evidence consistent with the framework’s implications. To establish the posited mechanism more directly, we conduct an online survey experiment priming respondents with the share of Hispanics in the US population. This allows us to tailor the questions we ask so as to examine not only whether whites’ racial attitudes change but also whether Blacks are more likely to be perceived as in-group members when the size of the Hispanic population becomes more salient.

Our survey experiment was conducted online in a sample of 499 white non-Hispanic respondents recruited through Lucid Theorem. The survey opened with two questions asking respondents to provide their best estimate of certain demographic characteristics of the US population. All respondents were asked to estimate the number of US residents. Respondents in the treatment group were asked to estimate what share of the US population consists of people of Hispanic origin. Respondents in the control group were instead asked to provide their best guess on the average age of US residents. We did not provide respondents with the correct answers to these questions, as we do not want to estimate the effect of information or of correcting misperceptions. Our goal was to lead respondents to reflect on the size of the Hispanic population.

We collected a number of outcomes that mirror the survey questions we analyze in the previous sections. We asked respondents to rate their feelings toward each of five groups in the US (Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, Muslims, whites) using a feeling thermometer, with identical wording as in the ANES. We also asked for respondents’ agreement with a number of statements associating groups with the same stereotypical attributes recorded in the ANES: intelligent, hardworking, trustworthy, violent. To measure recategorization, we followed Levendusky (Reference Levendusky2018) and included an additional item asking participants to rate how well the attribute “American” describes each group. Details on variables, sample characteristics and success of randomization can be found in Section F of the Online Appendix.Footnote 12 Our theory predicts that priming the size of the Hispanic population would lead white respondents to recategorize Blacks as Americans and express more positive attitudes toward them.

The upper-left panel of Figure 4 plots our measure of affective distance, thermometer ratings relative to whites, for respondents in the control group. All groups are viewed as more distant than whites. Consistent with patterns in the ANES, Muslims are viewed as most distant. Unlike patterns in the ANES, Asians are the second most distant group and Hispanics are viewed very similarly to Blacks.Footnote 13 The ranking of groups in terms of how American they are perceived to be is less surprising: the top-right panel of Figure 4 shows that whites rank highest, followed by Blacks. Asians and Hispanics are in the same position, whereas Muslims are perceived as the least American of all five groups.

Figure 4. Priming Respondents with Share of Hispanics in the US

Note: The top two subfigures plot averages among respondents in the control group. The bottom figures plot standardized beta coefficients of treatment effects on a principal component of attitudinal measures (left) and on perceptions of groups as American (right), with and without the inclusion of baseline controls. Thin and thick lines denote 95% and 90% confidence intervals, respectively. For more details on the experimental setup, sample, and estimation process see Section F of the Online Appendix.

The bottom panel of the figure displays the effects of the treatment. Priming respondents with the size of the Hispanic population increases positive attitudes toward Blacks, measured as the principal component of the thermometer and all four stereotypes. It also significantly increases ratings of Blacks as American. No statistically significant effect is estimated for any other group, and magnitudes for Blacks are always larger than those for other groups.Footnote 14 Interestingly, the treatment does not worsen attitudes toward Hispanics or other immigrant groups, nor does it lead respondents to perceive them as less American, possibly because immigration is already a salient group classifier in respondents’ minds.

Mexican Immigration and Changes in Whites’ Behavior

Our analysis so far relied on attitudinal variables, as the theoretical mechanism we propose is one of changes in perceptions and attitudes. Here, we turn to real-world behavior. Besides being of substantive interest, the use of behavioral outcomes addresses potential concerns that our effects are driven by social desirability bias changing differentially across groups. To assess whether reduction in anti-Black prejudice among whites implies changes in behavior, we examine rates of prejudice-motivated violence.

We use data on hate crimes available between 1992 and 2016, compiled by the FBI as part of the Uniform Crime Reporting program, distributed by the Inter-University Consortium for Social Research at the University of Michigan (FBI 2018). The data comprises all reported hate crimes, defined as “criminal offenses that are motivated, in whole or in part, by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity” (FBI 2015, 5).

Section G of the Online Appendix provides more details on the dataset. It is important to highlight two relevant features of the hate crimes measure here. First, FBI records are not accurate measures of bias-motivated violence, and likely underestimate violence, though overreporting is also a possibility (Freilich and Chermak Reference Freilich and Chermak2013). At the same time, they constitute the most complete dataset of hate crimes and the only dataset that allows for systematic comparisons across minority groups, space, and time. Second, hate crimes are an extreme measure of prejudice and as such may not necessarily reflect changes in the average behavior among whites. They capture the behavior of “extreme” individuals—those with high levels of prejudice or propensity to violence. There is no obvious reason why our framework of recategorization should not equally apply to this population, in which case hate crimes are a valid and informative behavioral measure.

These data contain information on the race of the perpetrator and on the crime’s motivating bias. Based on the location of the reporting agency, as provided through the Originating Agency Identifier, incidents are matched to counties. We average crimes across decades and estimate a county-level version of Equation 2, controlling for state by decade fixed effects. The dependent variable is hate crimes against Blacks per 100,000 people. The construction of the instrument for Mexican immigration follows the procedure detailed in Section E.1 of the Online Appendix.

Table 5 reports the results. The 2SLS estimates in Panel A indicate that Mexican immigration reduces anti-Black hate crimes (column 2). This effect is higher relative to the baseline mean when restricting attention to crimes committed by white offenders (column 4). Effects on hate crimes against Latinos are noisily estimated, but if anything they tend to increase in response to Mexican immigration, especially when focusing on white offenders (columns 2 and 4, Panel B). In Section G of the Online Appendix, we subject these estimates to several robustness checks similar to those of our baseline analysis and additionally verify that they do not reflect overall reductions in criminality in response to Hispanic immigration (Table G.5).

Table 5. Mexican Immigration and Hate Crimes

Note: Beta coefficients reported. Standard errors clustered at the county level are reported in parentheses; Conley standard errors using a distance cutoff of 500 km are reported in curly brackets.

The effects are substantive in magnitude. The coefficient in column 4 suggests that a one-percentage-point increase in the Mexican share leads to six fewer anti-Black hate crimes per 100,000 people, or 108% of the baseline mean. For the average county in our sample, our estimates imply that an increase in the share of Mexicans leads to about nine fewer hate crimes per 100,000 people against Blacks and 2.5 more hate crimes against Hispanics, though the latter quantity is not statistically significant.

Discussion and Conclusion

Due to rising immigration, over the past five decades the US and Europe have become increasingly diverse. How does this trend contribute to shaping social group boundaries in these societies? To answer this question, we introduce a conceptual framework where group boundaries are endogenous and context dependent and provide evidence for it by studying how Mexican immigration in the US between 1970 and 2010 influenced native whites’ attitudes toward African Americans.

We provide evidence in support of recategorization, whereby Mexican immigration induces whites to reclassify Blacks as “American” and thus as members of their in-group. This does not mean—either conceptually or in our data—that Blacks are assigned the same classification whites reserve for other whites. For clarity, our framework makes a stylized distinction between “us” and “them” and assumes in-group homogeneity in terms of affective distance. Yet in-groups can be heterogeneous. Carbado (Reference Carbado2005) discusses how Blacks have historically participated in an American identity, without necessarily being granted either formal citizenship—during the period of slavery—or equality—during the period of Jim Crow and later. In other words, whites have historically viewed Blacks as American, an identity that they were less willing to confer to other groups like Asians or Latinos. At the same time, Black American identity may be understood in terms of marginalization and “[remain] directly linked to racial subordination” (Carbado Reference Carbado2005, 645). In our data, Blacks are viewed by whites as more American than other groups, but they are not assigned the same degree of American identity or the same affective distance as whites are. We highlight that recategorization may take place without a complete elimination of racial group boundaries erected by prejudice and discrimination.

A complementary explanation behind whites’ reactions toward Blacks in response to Mexican immigration is that of uniting against a common enemy. Lab-based evidence in evolutionary psychology indicates that coalitional considerations determine the importance of race as a social category (Kurzban, Tooby, and Cosmides Reference Kurzban, Tooby and Cosmides2001). However, a coalitional theory does not explain why majority members would form coalitions with certain groups (Blacks) but not others (Asians).

A distinct, but related, framework is the common in-group identity model (Gaertner et al. Reference Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman and Rust1993), which predicts that priming a superordinate group identity can reduce out-group prejudice.Footnote 15 In our context, Mexican inflows may prime a superordinate “American” identity, thereby reducing the importance of race as a social cleavage. Yet the fact that non-Mexican immigration does not have the same effect necessitates that this theory be extended with additional assumptions in order to explain our empirical findings in their entirety.

Our conceptual framework helps reconcile conflicting results in the literature. On the one hand, Rasul and McConnell (Reference Rasul and McConnell2021) find that September 11, and the associated Islamophobic reaction among Americans, worsened attitudes toward Hispanics. On the other, Fouka, Mazumder, and Tabellini (Reference Fouka, Mazumder and Tabellini2021) find that 1915–1930 Black in-migration to the US North, and the associated increase in racism among northern whites, improved the relative standing of (white European) immigrants. Our framework can explain these seemingly contradictory findings. By raising the salience of dimensions related to immigration and foreign-born threat, September 11 had negative spillovers on all groups differing from natives on such dimensions, including Hispanics.Footnote 16 Instead, by raising the salience of skin color, Black in-migration to the US North reduced the importance of ethnicity as a dimension relevant for social categorization, thus helping white immigrants.

Finally, we highlight implications of our study that travel beyond the US context. A large constructivist tradition in ethnic politics (Chandra Reference Chandra2006; Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2000; Posner Reference Posner2005) examines the conditions under which ethnicity emerges as a relevant cleavage in a society. This literature has focused primarily on group members’ identification with their own ethnicity. Our study highlights a complementary dimension to in-group identity that matters for the salience of ethnicity: majority attitudes toward minorities. We suggest that whether majorities discriminate on the basis of ethnicity or of another attribute is endogenous to the composition of out-groups in a society, primarily in terms of perceived affective distance from the majority. When the affective distance of majorities from groups differing on the basis of ethnicity is large, ethnicity endogenously emerges as a basis for discrimination or allocation of privileges in a society. Ethnicity can then become salient because members of ethnic groups rationally choose their ethnic identity—as the constructivist literature suggests—or because majorities discriminate on the basis of ethnicity—as our framework would indicate. We leave the full development and empirical test of this idea to future work.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001350.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials for this study are available at the American Political Science Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LH67QU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Shom Mazumder who contributed to earlier versions of the project and left our collaboration due to professional reasons. We are also grateful to Mina Cikara, Tom Clark, Lauren Davenport, Elias Dinas, Ryan Enos, Hakeem Jefferson, Ross Mattheis, David Laitin, and Alain Schläpfer, as well as seminar participants at ASREC 2019, the Immigration Research Frontiers and Policy Challenges Conference at U Penn, IPES 2019, the ASSA 2020 Annual Meetings, the Hoover Institution, IPERG Barcelona, NYU Abu Dhabi, Emory, and Washington University at St. Louis for helpful comments and discussions. Ludovica Ciasullo, Silvia Farina, Pierfrancesco Mei, Filippo Monterosso, Ludovica Mosillo, Gabriele Romano, Gisela Salim Peyer, and Arjun Shah provided excellent research assistance. All errors are the authors’ own.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.