Introduction

The human gut microbiome comprises up to 100 trillion microbes, consisting of at least 150 times more genes than the whole human genome(Reference Rosenbaum, Knight and Leibel1). Recent decades have seen a surge in research surrounding the cross-talk between gut microbiota and their host, the interactions between which have been implicated in a multitude of physiological processes and pathologies, from regulation of appetite signalling(Reference Fetissov2) to gut barrier function(Reference Tehrani, Nezami, Gewirtz and Srinivasan3) and modulation of host immune responses(Reference Louis, Hold and Flint4).

Gut bacteria can modulate the digestibility and absorbability of dietary substrates, thereby influencing energy-harvesting efficiency(Reference Turnbaugh, Ley, Mahowald, Magrini, Mardis and Gordon5–Reference Tschöp, Hugenholtz and Karp8). The emerging understanding of the intimate relationship between intestinal microbiota and host metabolism has sparked considerable interest in the gut microbiome as a novel target for counteracting the chronic, positive energy balance in obesity. Obesity is a disease that has reached pandemic levels globally in the last 50 years and is a major public health issue, contributing to >70 % of premature deaths(Reference Blüher9).

This scoping review explores the potential for therapeutic modulation of gut microbiota as a means of prevention and/or treatment of obesity and obesity-associated metabolic disorders. This review focuses on interventional approaches which have been shown to affect the composition and function of the intestinal microbiome, including dietary strategies(Reference Sonnenburg and Bäckhed10,Reference Sonnenburg, Xu and Leip11) , oral probiotic treatment(Reference Degirolamo, Rainaldi, Bovenga, Murzilli and Moschetta12), faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)(Reference Khoruts and Sadowsky13,Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14) and bariatric surgery(Reference Liou, Paziuk, Luevano, Machineni, Turnbaugh and Kaplan15,Reference Zhang, DiBaise and Zuccolo16) (Fig. 1). It goes on to consider opportunities for perinatal intervention, given the high susceptibility of the microbiome to metabolic alterations as it is established and evolves during early life(Reference Cox Laura, Yamanishi and Sohn17,Reference Cox and Blaser18) .

Fig. 1. Summary figure of interventions which demonstrate potential for altering the composition of the obese microbiome, and characteristic features of the obese microbiome. MAC, microbiota-accessible carbohydrates; NCCDs, non-communicable chronic diseases. Figure adapted from Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg 2019(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45).

The obese microbiome – an overview

The link between gut microbiota and obesity became a subject of scientific interest when it was observed that germ-free mice, which lack gut microbiota, have reduced adiposity and better glucose and insulin tolerance than their conventional counterparts(Reference Bäckhed, Ding and Wang7). Germ-free mice are unable to process food efficiently, but gain weight following gut colonisation with almost any microbial population(Reference Rosenbaum, Knight and Leibel1,Reference Bäckhed, Ding and Wang7) . When germ-free mice are colonised with specified microbial populations (i.e. gnotobiotic mice), they gain weight despite decreased energy intake and increased energy expenditure relative to germ-free controls(Reference Bäckhed, Ding and Wang7). This counterintuitive phenomenon suggests that inoculation of germ-free mice with microbiota confers increased capacity to harvest calories from ingested food(Reference Rosenbaum, Knight and Leibel1). In 2006, pioneering work from Jeff Gordon’s lab found that transfer of microbiota from obese to germ-free mice resulted in a significantly greater increase in body fat compared with gut colonisation with microbiota from lean donors(Reference Turnbaugh, Ley, Mahowald, Magrini, Mardis and Gordon5). This led to the suggestion that microbiome composition is a key driver of energy host balance, and that the apparent capacity of the ‘obese microbiome’ (i.e. microbiota from obese donors) to harvest more energy from the diet is a transmissible trait(Reference Turnbaugh, Ley, Mahowald, Magrini, Mardis and Gordon5). Since these preliminary findings suggested exciting potential for microbiome-related therapies to affect metabolic health, the past 15 years have seen a growing body of research which seeks to determine how our gut microbiota may alter the way we absorb, metabolise and store energy.

In humans and mice, over 90 % of the distal gut microbiota comprises species from two bacterial phyla: the Bacteroidetes and the Firmicutes(Reference Turnbaugh, Bäckhed, Fulton and Gordon19). The obese phenotype is often cited as being associated with an increased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes phyla in the gut microbiome, as observed in both mice(Reference Ley, Bäckhed, Turnbaugh, Lozupone, Knight and Gordon20) and humans(Reference Turnbaugh, Hamady and Yatsunenko21). Though the association between obesity and the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes versus Firmicutes is often heralded as a robust finding, human and animal studies have yielded conflicting results about the precise nature of associations between obesity and microbiome composition(Reference Finucane, Sharpton, Laurent and Pollard22–Reference Ley25). An analysis comparing results of highly cited studies found that the variation in relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes was much greater between studies than between lean and obese subjects within any individual study(Reference Finucane, Sharpton, Laurent and Pollard22). Differing trends in Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratios with increasing body mass index (BMI) have been reported in men versus women(Reference Haro, Rangel-Zúñiga and Alcalá-Díaz26), and even in studies where obesity is associated with an increased F/B ratio, the association is not necessarily constant – F/B ratio has been seen to increase with BMI up to 33 and subsequently decrease when BMI > 33(Reference Haro, Rangel-Zúñiga and Alcalá-Díaz26). Important sources of inter-study variation include methodological differences such as bacterial sequencing methods, bacterial sample source (e.g. duodenum versus faeces) and differences in BMI categories in different countries(Reference Castaner, Goday and Park27). Furthermore, the obese microbiome has been shown to have markedly reduced microbial diversity in faecal metagenome analysis comparing human twin pairs discordant for obesity(Reference Turnbaugh, Hamady and Yatsunenko21), though this too is not consistently demonstrated(Reference Finucane, Sharpton, Laurent and Pollard22). As yet, it seems that there is no simple taxonomic signature of obesity in the human gut microbiota. Indeed, a taxonomic signature alone may be of little significance without accompanying functional analysis at the species level, since closely related taxa can have widely varying functions whilst distantly related taxa may function similarly(Reference Finucane, Sharpton, Laurent and Pollard22).

Much of our current understanding of the role of host–microbe interactions in obesity is derived from studies on germ-free mice. Although germ-free mice can survive on a standard diet, the lack of an established gut microbiome is associated with a plethora of physiological abnormalities such as underdeveloped intestinal morphology(Reference Al-Asmakh and Zadjali28), decreased basal metabolic rate(Reference Al-Asmakh and Zadjali28) and reduced immune resistance to infection(Reference Round and Mazmanian29). Immune-mediated components may play an important role in the mechanisms underlying microbiota-driven weight gain. Indeed, the introduction of gut bacteria in germ-free mice seems to trigger the formation of isolated lymphoid follicles and cause structural changes in intestinal epithelial cells which line the gut and act as a physical barrier between gut luminal contents and underlying cells of the immune system(Reference Round and Mazmanian29). As well as triggering changes in intestinal morphology and physiology, the commensal gut bacteria themselves provide ‘colonisation resistance’ which intestinal pathogens must overcome in order to establish infection(Reference Round and Mazmanian29). Colonisation of germ-free animals with some commensal bacteria species has been shown to be protective against intestinal bacterial pathogens(Reference Maier and Hentges30,Reference Zachar and Savage31) . Given the intimate and dynamic relationship between the immune system and the microbiota, it is likely that weight gain associated with gut colonisation is at least in part immune-mediated, especially in the context of gnotobiology.

One of the hallmarks of obesity is a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation. The presence of excess nutrients seems to drive activation of specialised immune cells and lead to an unresolved inflammatory response within adipose tissue(Reference Gregor and Hotamisligil32). Studies in conventional mouse models and humans suggest that the microbiota may play a role in modulating obesity-associated inflammation. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or ‘endotoxins’ are bacterial cell wall components thought to be involved in the initiation of obesity-associated inflammation(Reference Boulangé, Neves, Chilloux, Nicholson and Dumas33). Studies investigating LPS, which activates the host’s innate immune system through macrophage surface receptor Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), demonstrate increased levels of circulating LPS in mice fed a high-fat diet(Reference Cani, Amar and Iglesias34) and increased TLR4 activation in obesity-prone rats with altered gut microbiota(Reference de La Serre, Ellis, Lee, Hartman, Rutledge and Raybould35). Similar findings have been shown in humans, with obese and type 2 diabetic subjects showing higher baseline circulating LPS levels than non-obese controls, as well as a greater rise in LPS levels after eating a high-fat meal(Reference Harte, Varma and Tripathi36). Obesity-prone rats treated with antibiotics show decreased levels of LPS and TNF-α expression in the intestine, alongside a reduction in body weight and improvements in glucose tolerance(Reference Cani, Bibiloni and Knauf37,Reference Membrez, Blancher and Jaquet38) , whilst TLR4-knockout mice seem to be protected against insulin resistance induced by a high-fat diet(Reference Shi, Kokoeva, Inouye, Tzameli, Yin and Flier39). It has been suggested that obesity-associated endotoxemia may be in part driven by microbiota-induced increases in gut permeability, causing LPS translocation and a subsequent increase in circulating LPS levels(Reference Cani, Amar and Iglesias34).

Another potential key player in obesity-associated inflammation may be short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs are derived from gut microbial fermentation of indigestible dietary polysaccharides and serve as the main energy source for colonocytes as well as being substrates for lipid storage and regulating appetite via G-protein-coupled receptor signalling(Reference Rosenbaum, Knight and Leibel1). SCFAs have a well-characterised anti-inflammatory effect on colonic epithelium and immune cells, as demonstrated in a study by Maslowski et al. in which mice deficient in GPCR 43, a receptor known to be stimulated by SCFAs, showed exacerbating or unresolving inflammation in models of colitis, arthritis and asthma(Reference Maslowski, Vieira and Ng40). Germ-free mice produce almost no SCFAs(Reference Maslowski, Vieira and Ng40), and it has been suggested that adiposity seen in gnotobiotic mice may be partly due to the increased availability of SCFAs brought about by the transplanted bacteria which could in turn increase energy harvesting from ingested foods(Reference Rosenbaum, Knight and Leibel1). SCFAs have also been shown to reduce the release of inflammatory cytokines(Reference Maslowski, Vieira and Ng40) which may in turn enhance hypothalamic sensitivity to the satiety hormone leptin(Reference de Git and Adan41).

Despite a wide consensus that gut microbiota composition is linked to host energy balance, the host–microbe mechanisms underlying this complex process in humans remain elusive, as human studies have been primarily epidemiological(Reference Rosenbaum, Knight and Leibel1). Microbiome communities are complex networks of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses and protozoa – all of these components, together with their metabolites, could contribute to the obese phenotype, exerting either individual or synergistic effects(Reference Walter, Armet, Finlay and Shanahan42).

Your microbiome is what you eat: gut populations are plastic

The gut microbiome is plastic and adaptable in the face of a changing nutritional environment. A large increase in fibre intake can substantially alter microbiota composition and function over 1–2 days, as might be expected for a complex microbial community that must adapt to rapid turnover during day-to-day dietary variation(Reference Sonnenburg and Bäckhed10). The influence of dietary alteration on microbiome composition has been recognised since the early twentieth century, when Herter and Kendall used culture-based methods to demonstrate that protein-dominated diets could shift the bacterial microbiota in monkeys and cats, increasing abundance of proteolytic bacteria and decreasing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species(Reference Bested, Logan and Selhub43,Reference Herter and Kendall44) . Germ-free mice colonised with human microbiota and fed a fibre-rich diet show significant up-regulation of bacterial genes involved in polysaccharide metabolism(Reference Sonnenburg, Xu and Leip11). However, when a no-fibre diet is given, enrichment of bacterial genes involved in degradation of glycans from the surrounding host mucus is observed(Reference Sonnenburg, Xu and Leip11). This demonstrates the flexibility of the gut microbiota to undergo functional adaptations when confronted with dietary change.

Recent decades have seen the human microbiota undergo substantial remodelling in industrialised societies, coincident with increased antibiotic use and sanitation, and industrialisation of food production(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45). The modern ‘Western diet’ consists of processed foods rich in fat, sugar, protein and additives, with relatively sparse amounts of micronutrients or dietary fibre(Reference Cordain, Eaton and Sebastian46,Reference Yatsunenko, Rey and Manary47) . Dietary fibres which are indigestible by the host but can be broken down by gut bacteria-derived enzymes are termed microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs)(Reference Daïen, Pinget, Tan and Macia48). MACs serve as the major energy source for colonic bacteria(Reference Sonnenburg Erica and Sonnenburg Justin49). MAC deprivation in modern Western diets seems to favour shifts in gut microbial compositions to enrichment of mucus-degrading microorganisms(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45,Reference Sonnenburg Erica and Sonnenburg Justin49) , emergence of antibiotic-resistant species(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45), and loss of seasonally volatile species due to the stable homogeneity of the industrialised diet(Reference Smits, Leach and Sonnenburg50) (Fig. 1). This contrasts starkly with the microbiome of individuals from an isolated Yanomami Amerindian village with no known previous contact with Western people, whose faecal, oral and skin bacterial microbiome were found to exhibit the highest diversity of bacteria and genetic functions ever reported in a human group(Reference Clemente, Pehrsson and Blaser51).

It has been proposed that we currently face a mismatch between our recently altered microbiota and the more slowly evolving human genome(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45,Reference Blaser52) . Molecular signals generated by microbial taxa which have become extinct in the ‘industrialised’ microbiome are likely to have influenced the evolution of the human genome(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45). It is speculated that loss of these microbial signals might explain physiological abnormalities including dysregulated immune function and a chronic baseline of inflammation which may drive the increased prevalence of non-communicable chronic diseases such as metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis and autoimmune disease(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45). In a Colombian population in the midst of Westernisation, gene sequencing of stool samples found that microbiomes dominated by pathobionts such as Escherichia coli and Enterobacter hormaechei were associated with increased BMI and waist circumference, as well as an increased risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease, relative to individuals whose microbiomes comprised taxa associated with diets rich in fibre and complex carbohydrates(Reference de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, Corrales-Agudelo, Velásquez-Mejía, Carmona, Abad and Escobar53). Germ-free mice fed a low-fibre diet exhibit lower species diversity in their gut microbiota compared with their high-fibre-fed counterparts. This effect is partially reversible upon returning to a normal diet(Reference Sonnenburg, Smits, Tikhonov, Higginbottom, Wingreen and Sonnenburg54). The loss of diversity is compounded with each subsequent generation of mice maintained on a low-fibre diet, and the ability to recover is reduced, suggesting extinction of some microbial species associated with low fibre intake(Reference Sonnenburg, Smits, Tikhonov, Higginbottom, Wingreen and Sonnenburg54,Reference Martens55) .

In a 1-year dietary intervention study in which twelve obese people were assigned to either fat-restricted or carbohydrate-restricted low-calorie diets, the percentage weight loss of participants was correlated with increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and not with changes in dietary calorie content(Reference Ley, Turnbaugh, Klein and Gordon56) (Table 1). These changes were phylum-wide and not due to increases or losses of specific bacterial species – indeed, bacterial species-level diversity within individuals’ microbiota remained constant over time(Reference Ley, Turnbaugh, Klein and Gordon56). The association of obesity with profound, phylum-wide changes in microbiota composition despite inter-individual differences in species-level composition might suggest that the factors which drive phylum-wide microbiota shifts operate on highly conserved bacterial traits common to many species within each phylum(Reference Ley, Turnbaugh, Klein and Gordon56). Although dietary fibres can drive changes in microbiota composition, the baseline composition of an individual’s microbiome will influence the extent of change possible. A study in which fourteen participants with metabolic syndrome were put on a standardised diet found that two of the participants demonstrated a markedly reduced ability to digest orally administered resistant starch(Reference Walker, Ince and Duncan57). It was suggested that the low starch fermentation rate in the two diet-unresponsive individuals could be partially attributed to markedly low numbers of Ruminococcus bromii-related taxa in their colonic microbiota at baseline(Reference Walker, Ince and Duncan57). Host genetics add a further layer of complexity to individual energy balance. Concordance rates of body adiposity between monozygotic twins is double that of dizygotic twins(Reference Stunkard, Foch and Hrubec58), despite showing similar degrees of co-variation in microbiota composition(Reference Turnbaugh, Hamady and Yatsunenko21).

It has been proposed that re-establishment of ‘compatibility’ between the microbiome and the human genome might require a controlled ‘re-wilding’ process in which microbial species and/or functions now absent or sparse in industrialised microbiomes are re-established through increased consumption of foods which support engraftment of these species in the gut(Reference Sonnenburg and Sonnenburg45). Using mice colonised with different human microbiota, Shepherd et al. demonstrated that introduction of Bacteroidetes ovatus or NB001, a commensal species which utilises porphyran (a polysaccharide abundant in seaweed) resulted in a predictable rise in levels of NB001 when the mice were fed seaweed(Reference Shepherd, DeLoache, Pruss, Whitaker and Sonnenburg59). The introduction of porphyran into the diet rescued NB001 from undetectable levels even in mice with the most resistant microbiota(Reference Shepherd, DeLoache, Pruss, Whitaker and Sonnenburg59). Although the utility of this particular polysaccharide system may only apply to individuals colonised with competing porphyran users (e.g. a limited subset of the Japanese population), these results provide an intriguing proof-of-concept for controlling strain engraftment into the gut microbiome, using select pairs of nutrients and their cognate utilisation systems to stimulate blooming of select bacterial species(Reference Shepherd, DeLoache, Pruss, Whitaker and Sonnenburg59).

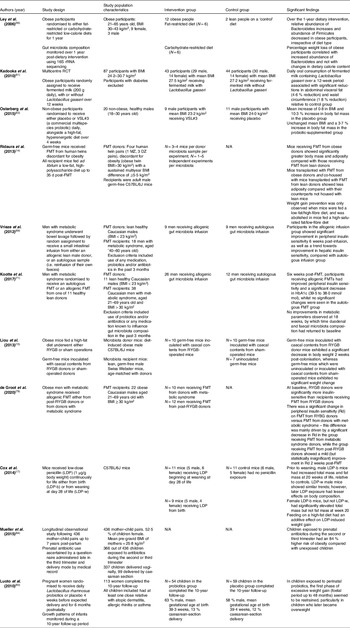

Table 1. Summary of characteristics of studies examining the effects of different interventions on metabolic outcomes such as body weight, fat mass and insulin sensitivity

rRNA, ribosomal RNA; RCT, randomised controlled trial; FMT, faecal microbiota transplant; MZ, monozygotic; DZ, dizygotic; BMI, body mass index; LDP, low-dose penicillin.

Probiotics for weight loss: credible or a con?

Another potential means of microbiota manipulation is oral consumption of viable bacterial strains. So-called probiotic dietary supplements are a multi-billion dollar industry, claiming efficacy for ameliorating a wide range of diseases ranging from irritable bowel syndrome and sepsis to dermatitis and depression(Reference Suez, Zmora, Segal and Elinav60). The rationale for therapeutic use of probiotics is to introduce selected bacterial strains associated with health benefits into the microbiome. Given the emerging links between obesity and associated shifts in microbiome composition(Reference Ley, Bäckhed, Turnbaugh, Lozupone, Knight and Gordon20,Reference Turnbaugh, Hamady and Yatsunenko21) , it has been speculated that probiotics may serve as therapeutic agents in the context of obesity and associated metabolic disorders(Reference Kadooka, Sato and Imaizumi61). However, the mechanisms of action underlying the capacity of administered microorganisms to colonise the host gastrointestinal mucosa remain poorly understood. This is in part due to the limitations of analyses such as stool assessment, or in vitro cell studies which are unlikely to represent the complex host–microbiome interactions underlying the colonisation process in vivo (Reference Suez, Zmora, Segal and Elinav60). Despite the popularity of probiotic supplements, decades’ worth of research on the efficacy of probiotics in treating disease have spawned conflicting claims which remain inconclusive(Reference Suez, Zmora, Segal and Elinav60).

Some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have suggested that probiotics lower BMI and visceral fat mass. A multicentre RCT involving eighty-seven adults found that daily oral consumption of fermented milk containing Lactobacillus gasseri over a 12-week period was associated with significant reductions in abdominal visceral fat (4·6 % reduction) and waist circumference (1·8 % reduction)(Reference Kadooka, Sato and Imaizumi61) (Table 1), both parameters known to be closely correlated with high risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease(Reference Giordano, Frontini and Cinti62). In another RCT, twenty non-obese males were participants to receive either placebo or VSL#3 (a commercial multispecies probiotic) daily, alongside a high-fat, hyperenergetic diet over 4 weeks(Reference Osterberg, Boutagy and McMillan63) (Table 1). The authors claimed that VSL#3 supplementation protected participants from gaining body mass and fat mass, based on a mean increase of 0·8 in BMI and 10·3 % increase in body fat mass in the placebo group versus an unchanged mean BMI and a 3·7 % increase in body fat mass in the probiotic-supplemented group(Reference Osterberg, Boutagy and McMillan63). However, the small sample size (placebo group N = 11, probiotic group N = 9) and inclusion of only young, lean male participants in the study means that such results can hardly be extrapolated to an obese population.

In 2018, Borgeraas et al. published a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs conducted to examine the effects of probiotic supplementation on body weight, BMI and fat mass, comprising fifteen studies, 957 participants (63 % women) all with a mean BMI > 25 (i.e. overweight or obese) and ranging from 18 to 75 years of age(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64). Meta-analyses including thirteen studies found that, compared with placebo, the probiotic-supplemented groups showed greater weight loss (weighted mean difference −0·60 [95 % CI −1·19, −0·01] kg]) and greater reduction in BMI (weighted mean difference −0·27 [95 % CI −0·45, −0·08] kg m−2)(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64). Though these differences were statistically significant, the actual effect sizes were small(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64). In the seven studies reporting fat mass as an outcome, the effect of probiotic supplementation on fat mass was not significant (−0·42 [95 % CI −1·08, 0·23] kg)(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64). Sensitivity analyses showed that the effects of probiotic supplementation were reduced when restricting analyses to include only subjects clearly classified as overweight or obese – in these cohorts, BMI reduction was smaller (weighted mean difference −0·14 [95 % CI −0·45, −0·18] kg m−2), as was weight loss (weighted mean difference −0·25 [95 % CI −1·06, 0·56] kg)(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64). One-third of the studies included in this review included two or multiple species of probiotics in the test supplement(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64). Every unique probiotic strain will have a different therapeutic potential, so meta-analyses that assess all bacterial strains together are of limited utility. Furthermore, many studies testing efficacy of probiotic supplements are appreciably underpowered(Reference Borgeraas, Johnson, Skattebu, Hertel and Hjelmesaeth64).

A 2017 systematic review by Crovesy et al. analysed fourteen RCTs (1067 participants in total) examining the effects of Lactobacillus probiotic supplementation on body weight and/or fat mass in participants aged 19–60 years(Reference Crovesy, Ostrowski, Ferreira, Rosado and Soares-Mota65). Two studies reported weight gain in the Lactobacillus-supplemented group, whilst three showed no difference in body weight between groups(Reference Crovesy, Ostrowski, Ferreira, Rosado and Soares-Mota65). Nine studies did observe weight or fat loss in the probiotic-supplemented group, although some studies included additional weight loss interventions alongside probiotic supplementation including a hypoenergetic diet in two studies and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) in another(Reference Crovesy, Ostrowski, Ferreira, Rosado and Soares-Mota65), making it difficult to attribute any clinical outcome to probiotics alone.

Most currently available probiotic preparations have not been formulated with a specific metabolic target, and most lack the density or complexity required to influence an established gut microbiota. It is therefore not surprising that currently available probiotic treatments have not conferred clinically significant health benefits for patients with obesity or associated metabolic disorders. A lack of understanding of the mechanisms of action underlying gut colonisation by administered probiotics makes it difficult to design probiotic studies that fulfil a particular therapeutic goal. Research efforts to develop rationally designed microbiome-targeted therapies by identifying candidate organisms that confer a metabolic benefit have a better chance of yielding clinically useful therapies.

Faecal microbiota transplantation: a future in obesity treatment?

FMT involves transferring the whole faecal microbial community from a healthy donor into the intestinal tract of a recipient, in order to modify intestinal microbial composition and function(Reference Khoruts and Sadowsky13). Arguably, FMT is the most persuasive experimental tool to demonstrate a causal role for gut microbiota in human disease(Reference Walter, Armet, Finlay and Shanahan42). Indeed, FMT showed the role of manipulating the gut microbiota in both treating and preventing disease associated with C. difficile (Reference Gupta, Allen-Vercoe and Petrof66) and is now an established trreatment for patients with recurrent or refractory C. difficile infections(Reference Khoruts and Sadowsky13,Reference Cuevas-Sierra, Ramos-Lopez, Riezu-Boj, Milagro and Martinez67) . Preclinical studies have shown that FMT can reverse obesity in mice(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14), so it is an attractive microbiome-targeting therapy for obesity, although studies in humans remain few.

In a fascinating study by Ridaura et al., germ-free mice received FMTs from human twins discordant for obesity(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14). Despite all mice being fed the same low-fat/high-fibre diet, mice receiving FMT from obese donors showed significantly greater body mass and adiposity compared with their counterparts receiving FMT from lean donors(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14) (Table 1). Mice are coprophagic, so share the microbiome of cohabiting mice. The authors therefore carried out an experiment in which mice respectively transplanted with lean and obese microbiota were co-housed(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14). Mice transplanted with FMT from obese donors and co-housed with mice transplanted with FMT from lean donors showed less adiposity compared with their counterparts not housed with lean mice(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14). Faecal metagenome analysis pre- and post-co-housing showed that the microbiota of obese-phenotype mice were successfully invaded by bacteria (largely of the Bacteroidetes phylum) from the microbiota of the lean-phenotype mice when these mice were co-housed(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14). The invasion of obese mice with ‘lean microbiota’ was sufficient to reshape their microbiota and prevent the development of increased body mass and obesity-associated metabolic phenotypes(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14). Importantly, this effect was diet-dependent – weight gain prevention was only observed when mice were fed a low-fat/high-fibre diet, and was abolished in mice fed a high-saturated fat/low-fibre diet(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14). These findings support the concept that therapeutic establishment of a defined ‘lean’ microbiota could be an effective way of preventing obesity, with the important caveat that a concomitant healthy diet would be necessary(Reference Pedersen, Clément and Gewirtz68).

In one of the few human studies investigating the efficacy of FMT in an obesity-related context, eighteen men with metabolic syndrome were randomly assigned to receive a small intestinal infusion from either an allogenic lean male donor, or an autologous sample (i.e. reinfusion of their own faeces)(Reference Vrieze, Van Nood and Holleman69) (Table 1). Relative to the autologous group, subjects in the allogenic group showed significant improvement in peripheral insulin sensitivity 6 weeks post-infusion, as well as a trend towards improvement in hepatic insulin sensitivity(Reference Vrieze, Van Nood and Holleman69). Of note, men in the allogenic group showed significant increases in butyrate-producing bacteria in both faecal and duodenal samples, leading the authors to suggest a role for butyrate in contributing to improvement in insulin sensitivity(Reference Vrieze, Van Nood and Holleman69), as observed in mice(Reference Gao, Yin and Zhang70).

More recently, the same group carried out another study in which thirty-eight men with metabolic syndrome were randomised to receive an autologous FMT or an allogenic FMT from one of eleven healthy lean donors(Reference Kootte, Levin and Salojärvi71) (Table 1). At six weeks post-FMT, participants receiving allogenic FMTs exhibited metabolic improvements, including improved peripheral insulin sensitivity and a significant decrease in HbA1c (39·5 to 38·0 mmol/mol), whilst no significant changes were seen in the autologous FMT group. Although half the subjects receiving allogenic FMT showed clinically relevant improvements at six weeks, these metabolic improvements were transient – no metabolic changes were observed at eighteen weeks, by which time duodenal and faecal microbiota composition had returned to baseline(Reference Kootte, Levin and Salojärvi71). The short-lived nature of the metabolic improvements seen in the allogenic FMT group is perhaps due to the host immune system developing resilience, which, together with lifestyle factors such as diet, may drive the intestinal microbiota composition back to baseline(Reference Greenhill72).

Whilst FMT is being increasingly used clinically to treat recurrent Clostridium difficile infections, it is worth noting that the data remain limited on the full range of possible adverse effects of this treatment(Reference Alang and Kelly73). A notable case report is that of a 32-year-old female who underwent FMT for recurrent C. difficile and reported unintentional rapid weight gain of 15·4 kg over 16 months, increasing her BMI to 33 from a baseline of 26, despite a medically supervised diet and exercise programme(Reference Alang and Kelly73). There are many confounding factors at play here, not least the recipient’s long-standing diarrhoeal infection and treatment with an extensive cocktail of antibiotics before and after FMT, and the lack of any microbiome sequencing data comparing the patient and donor is a key limitation. Nevertheless, the observed increase in BMI to 34·5 at 36 months post-FMT (from a baseline BMI of 26) raises the possibility that the FMT played a causal role in this substantial and long-lasting weight change(Reference Alang and Kelly73), which would align with Ridaura et al.’s findings in animal models(Reference Ridaura, Faith and Rey14).

So far, the apparent metabolic benefits of allogenic FMT seen in obese human cohorts show some promise, although human studies remain limited in the sample size and range of patient phenotypes included. Further randomised clinical trials should extend selection criteria to a range of obese phenotypes beyond those with metabolic syndrome and explore a broad range of clinically relevant outcomes, such as long-term glycaemic control, truncal weight loss, or onset of obesity-associated co-morbidities. Additionally, it is worth noting that the two RCTs cited above(Reference Vrieze, Van Nood and Holleman69,Reference Kootte, Levin and Salojärvi71) included male participants only. Given evidence that microbiota composition differs by sex in a BMI-specific manner(Reference Haro, Rangel-Zúñiga and Alcalá-Díaz26), it is important that we obtain sex-specific data on the efficacy of microbiome-targeted interventions for obesity.

Does microbiome modulation contribute to metabolic improvements after bariatric surgery?

Bariatric surgery, which results in malabsorption and improved satiety, is the ultimate therapeutic resort for morbidly obese patients and is superior to any other weight-loss intervention(Reference Giordano, Frontini and Cinti62,Reference Meijnikman, Gerdes, Nieuwdorp and Herrema74,Reference Ryan, Tremaroli and Clemmensen75) . Within days after surgery, patients show improvement in metabolic parameters such as fasting glucose levels(Reference Meijnikman, Gerdes, Nieuwdorp and Herrema74), before any significant change in weight. These early effects of bariatric surgery are thought to be driven by altered glucose homeostasis in the duodenum and by calorie restriction. Indeed, BMI- and HbA1c-matched patients undertaking either a very low-calorie diet or RYGB show insignificant differences in β-cell function and weight loss 3 weeks after intervention(Reference Jackness, Karmally and Febres76). However, it is thought that the longer-term durability of weight reduction and glycaemic control post-gastric bypass is attributable to other factors, such as altered incretin hormone secretion or bile acid malabsorption(Reference Vella77), which induce significant alterations in microbiome composition(Reference Meijnikman, Gerdes, Nieuwdorp and Herrema74).

In mouse models of RYGB, pre- and post-surgical faecal metagenome analysis found that RYGB led to a sustained alteration of the gut microbiota within 1 week of surgery(Reference Liou, Paziuk, Luevano, Machineni, Turnbaugh and Kaplan15) (Table 1). There were substantial increases in proportions of Verrucomicrobia and Proteobacteria phyla(Reference Liou, Paziuk, Luevano, Machineni, Turnbaugh and Kaplan15), mirroring microbiota changes seen in humans post-gastric bypass surgery(Reference Zhang, DiBaise and Zuccolo16). Germ-free mice inoculated with caecal contents of RYBG-operated mice showed significantly greater reduction in fat mass relative to those inoculated with microbiota from sham-operated donors(Reference Liou, Paziuk, Luevano, Machineni, Turnbaugh and Kaplan15), suggesting that gastric bypass surgery confers a shift in microbiota composition which renders the host less predisposed to weight gain. In a human study, subjects with metabolic syndrome receiving allogenic FMT from post-RYGB donors (RYGB-D) showed a mild improvement in peripheral insulin sensitivity (33·9 to 36·2 µmol/kg/min) 2 weeks post-FMT(Reference de Groot, Scheithauer and Bakker78) (Table 1). At baseline, RYGB donors were significantly more insulin-sensitive than RYGB-D FMT recipients(Reference de Groot, Scheithauer and Bakker78); hence, these data suggest that healthy metabolic characteristics can be successfully acquired through FMT.

Exciting as such findings may be, they reflect a short time frame and there remains a lack of data which capture microbiome evolution at several time points after surgical intervention(Reference Cani79). Aron-Wisnewsky et al. followed twenty-four severely obese patients at 1, 3 and 12 months post-bariatric surgery and found that microbial gene richness (MGR) is only partially restored in most patients, who retain a low MGR despite exhibiting weight loss or major metabolic improvements(Reference Aron-Wisnewsky, Prifti and Belda80). MGR improvement seems to reach its peak at 1 year and shows no further improvement 5 years after surgery(Reference Aron-Wisnewsky, Prifti and Belda80), leading the authors to suggest that additional interventions such as specialised diets or FMT should be considered before or after bariatric surgery in severely obese individuals, in order to boost MGR(Reference Aron-Wisnewsky, Prifti and Belda80).

Some studies using RYGB mouse models have provided = insight into the mechanisms driving microbiome modulation post-bariatric surgery. RYGB-operated mice and gnotobiotic mice receiving RYGB microbiota show greater propionate and lower acetate production compared with sham-operated controls(Reference Liou, Paziuk, Luevano, Machineni, Turnbaugh and Kaplan15). Propionate has the highest known affinity of any SCFA for the GPR41 receptor, and GPR41-knockout mice show reduced energy expenditure and increased adiposity(Reference Bellahcene, O’Dowd and Wargent81). Another proposed mechanism for microbiota-driven weight change points to the profound increase in total circulating bile acids that follows bariatric surgery. As well as aiding lipid digestion and absorption, bile acids contribute to regulation of several metabolic processes by binding to the farnesoid X receptor (FXR). Obese FXR-knockout mice failed to maintain initial weight loss after vertical sleeve gastrectomy (a common bariatric surgical procedure), whilst their wild-type counterparts maintained weight loss over 11 weeks(Reference Ryan, Tremaroli and Clemmensen75). Caecal microbiota abundance of Bacteroides was reduced in wild-type gastrectomy mice compared with sham-operated controls, but did not differ among FXR-knockout mice(Reference Ryan, Tremaroli and Clemmensen75). The authors suggested that FXR signalling may link altered bile acid homeostasis to post-operative changes in gut microbial composition, potentially being an important mediator in the maintenance of weight loss following gastrectomy(Reference Ryan, Tremaroli and Clemmensen75). Further mechanistic studies such as these are warranted, as the discovery of metabolic pathways on which the complex microbiota network converge could reveal powerful therapeutic targets for microbiome modulation.

Nipping obesity in the bud: perinatal prevention of obesity

The establishment and maturation of the intestinal microbiota begins in pregnancy. The neonatal microbiota is highly susceptible to perturbations such as delivery route(Reference Dominguez-Bello, Costello and Contreras82), antibiotic treatment(Reference Cox and Blaser18) or dietary changes(Reference Cox and Blaser18,Reference Luoto, Kalliomäki, Laitinen and Isolauri83) . Much of an individual’s founding microbiota is acquired at birth and matures gradually, reaching adult-like complexity by about 3 years of age(Reference Cox and Blaser18). Microbiota disturbances during these early years have been associated with negative metabolic effects such as obesity in later life. There has been speculation about whether medical advances such as caesarean section deliveries, antibiotics and formula milk feeding might contribute to the obesity pandemic(Reference Cox and Blaser18).

Early life represents a window of metabolic vulnerability. Mice administered low-dose penicillin (LDP) at birth show greater weight gain than unexposed mice, or mice exposed to LDP at weaning(Reference Cox Laura, Yamanishi and Sohn17) (Table 1). Feeding on a high-fat diet has an additive effect on LDP-related weight gain, demonstrating the synergistic effects of dietary excess and early microbiota disturbance(Reference Cox Laura, Yamanishi and Sohn17). Notably, LDP-related metabolic disturbance is sustained in adulthood beyond cessation of antibiotic treatment – LDP-treated mice develop adult-onset obesity, despite recovery of the microbiota 4 weeks after stopping antibiotic treatment(Reference Cox Laura, Yamanishi and Sohn17). These findings support the idea that even transient microbiome disturbances in early life can have long-lasting metabolic effects.

The long-term metabolic impact of early-life antibiotics has similarly been observed in humans. A longitudinal study following 436 mother–child pairs up to 7 years post-partum showed that children exposed to prenatal antibiotics during the second or third trimester had an 84 % higher risk of obesity compared with unexposed children(Reference Mueller, Whyatt and Hoepner84) (Table 1). There were, however, significant limitations in this study, including lack of information about postnatal antibiotic use or medical indications for prenatal antibiotic use, as well as a high drop-out rate(Reference Mueller, Whyatt and Hoepner84). Similar studies which incorporate longitudinal faecal metagenome analysis would be informative in determining whether microbiota composition could in part explain the intriguing relationships observed between childhood obesity and prenatal antibiotic use or delivery method. Infancy may be a critical therapeutic window for prevention of obesity. In a perinatal probiotic intervention study which tracked growth patterns of infants during a 10-year follow-up, 113 women were randomised to receive Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotics or placebo 4 weeks before expected delivery and for 6 months postnatally(Reference Luoto, Kalliomäki, Laitinen and Isolauri83) (Table 1). In children exposed to perinatal probiotics, the first phase of excessive weight gain (foetal period up to 48 months) seemed to be restrained, particularly in children who later became overweight(Reference Luoto, Kalliomäki, Laitinen and Isolauri83). The authors concluded that probiotic-induced microbiota modulation in early life may restrain excessive weight gain in early infancy(Reference Luoto, Kalliomäki, Laitinen and Isolauri83), although of course a multitude of hereditary and environmental factors are also likely to be at play. Large-scale longitudinal studies which take into account a range of confounding factors influencing weight development will be important for informing anti-obesity interventions during the perinatal window of opportunity.

Technical challenges and emerging technologies for microbiome research

Gnotobiotic mice may provide the best experimental system for interrogating the effect of microbiota on metabolic function, but they are not humans with pre-existing gut microbiota. The relationship between a newly introduced gut microbiome and a surrogate host is likely to differ from that of a host and microbiome which have co-evolved over millennia(Reference Walter, Armet, Finlay and Shanahan42). Human microbiota-associated models (i.e. germ-free mice which have been inoculated with human microbiota) are intended to replicate human microbiome phylogenetic composition(Reference Al-Asmakh and Zadjali28), but many taxa fail to colonise in germ-free recipients(Reference Zhang, Bahl and Roager85). As well as having several physiological abnormalities(Reference Al-Asmakh and Zadjali28), human microbiota-associated mice lack human-specific factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease phenotype or human genotype which are integral influencers of microbiome composition(Reference Walter, Armet, Finlay and Shanahan42).

Exciting developments for microbiome research include in vitro bioreactors which mimic the human gastrointestinal tract, and ex vivo organoid models derived from human intestinal tissues. These platforms enable in vitro culture of human gut microbes, enabling highly controlled investigation of gut–microbiota interactions in real time(Reference Maruvada, Leone, Kaplan and Chang86). Human intestinal organoids resemble foetal intestines, providing a useful platform for studying early microbial colonisation and establishment, as well as the impact of nutrition or antibiotics on microbiome development during early life(Reference Maruvada, Leone, Kaplan and Chang86).

Gastrointestinal microbiomes are studied using metagenomic sequencing, typically of faecal samples. Traditional methods relied upon an amplicon sequencing strategy using the 16S rRNA gene as a phylogenetic marker. This method of analysis is largely limited to taxonomic classification at the genus level and provides almost no functional information(Reference Rausch, Rühlemann and Hermes87). Cutting-edge studies now use shotgun metagenomics, which can assess the entire genomic content of any microbiome sample, achieving precise strain-level classification and directly determining functional properties(Reference Forster, Kumar and Anonye88). Computational methods of metagenomic sample analysis derive genomes from de novo assemblies. This approach has limited capacity for distinguishing closely related bacterial taxa and may include assembled genomes which are incomplete or represent chimeric species(Reference Forster, Kumar and Anonye88). Given that multiple strains of the same bacterial species may exist in an individual’s microbiome, there is clearly a need to optimise the resolution of metagenomic analyses(Reference Forster, Kumar and Anonye88). The best available means of obtaining high-quality reference genomes is from pure cultures(Reference Forster, Kumar and Anonye88). Progress is being made in this area, with reference-based metagenomic analysis being used to compile the Human Gastrointestinal Bacteria Culture Collection. This is a set of 737 whole-genome-sequenced bacterial isolates that has increased the previous collection of human gut-derived bacterial genomes by 37 % and revealed 105 novel species(Reference Forster, Kumar and Anonye88).

Conclusions

Whilst the gut microbiome may have an important role to play in the establishment and maintenance of the obese phenotype, it is only one among a multitude of biological, psychological and social factors driving a chronic, positive energy balance. The increased supply of cheap, calorie-dense foods, together with improved food distribution and pervasive food marketing have been major drivers of the obesity epidemic over the past four decades(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall89). Since major contributors to the rise of obesity occur at a population level, it is probable that effective solutions will be beyond the scope of individual actions, such as banning unhealthy food marketing to children(90), reducing the cost of healthy foods(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall89), or implementing national food and agricultural policies that align with promotion of public health(91).

This review has explored the mounting evidence that microbiome composition is intimately and dynamically connected with host energy balance and metabolism. Interventional studies in obese populations have demonstrated metabolic improvements effected by microbiome-modulating treatments such as FMT, as well as highlighting the role of microbiome modulation in well-established anti-obesity interventions such as dietary change or bariatric surgery. However, with an evidence base that is largely derived from rodent studies and a lack of mechanistic insight into bacterial colonisation of the human gut, the question of how therapeutic manipulation of gut microbiota might effectively prevent or promote the reversal of obesity in humans is far from answered(Reference Turnbaugh92). Shotgun metagenomics now enables characterisation of human microbiomes at strain-level resolution, yet there remains a pressing need for a continued, global effort to collate genome sequences of cultured gastrointestinal bacterial isolates from individuals across diverse communities. This will be critical to understanding bacterial function at the strain level, paving the way for rational design of microbiome-based therapeutics. Longitudinal efficacy studies will be needed, involving faecal metagenomic analysis of large cohorts. As the complex relationship between microbiome composition and host metabolism is unravelled, it appears probable that microbial manipulation will provide a novel strategy as an effective treatment for obesity.

Acknowledgements

This scoping review is an adaptation of an essay titled ‘Flora and Fat: The gut microbiota as a therapeutic target for obesity’ written by Stephanie Santos-Paulo. The essay was the winning entry for the Oxford Medical School’s 2020 Sidney Truelove Prize for Gastroenterology. Simon Travis was the judge for the prize entries.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

Stephanie Santos-Paulo reports no conflicts of interest.

Simon Travis reports outside the submitted work receipt of grants/research support from AbbVie,

Buhlmann, Celgene, IOIBD, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, Takeda, UCB, Vifor, and Norman

Collisson Foundation; consulting fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena, Asahi,

Astellas, Biocare, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Buhlmann, Celgene,

Chemocentryx, Cosmo, Enterome, Ferring, Giuliani SpA, GSK, Genentech, Immunocore,

Immunometabolism, Indigo, Janssen, Lexicon, Lilly, Merck, MSD, Neovacs, Novartis,

NovoNordisk, NPS Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Proximagen, Receptos, Roche, Sensyne, Shire,

Sigmoid Pharma, SynDermix, Takeda, Theravance, Tillotts, Topivert, UCB, VHsquared,

Vifor, and Zeria; speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Ferring, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer,

Shire, and Takeda; no stocks or share options.

Robert Bryant has received Grant/Research support/Speaker fees (all paid to employer for research support): AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Shire, Takeda, Emerge Health; shareholder in Biomebank.

Sam Costello has received Grant/Research support/Speaker fees: Ferring, Janssen, Shire, Microbiotica, shareholder in Biomebank.

Samuel Forster is a shareholder in Biomebank.

Authorship

Stephanie Santos-Paulo is the primary author of this paper. She conducted the literature review and wrote the majority of the text.

Robert Bryant, Samuel Costello and Samuel Forster read several drafts of the paper, providing extensive feedback and suggestions as well as making minor edits to the content.

Simon Travis read the final draft of the paper, providing extensive feedback and suggestions as well as making minor edits to the content.