INTRODUCTION

When the U.K. hospice movement began, much of the psychosocial work was undertaken with patients who were in the end stages of their disease. More recently, both psychological and medical expertise to control pain and other symptoms has been used much earlier in a patient's illness with a beneficial effect on quality of life. Some early studies suggested that psychosocial interventions could influence survival, for example, Spiegel et al.'s (Reference Spiegel, Bloom and Kraemer1989) study on psychosocial interventions in breast cancer. Goodwin et al. (Reference Goodwin, Leszcz and Ennis2001), in a large multicenter study replicating the Spiegel et al. study, found that, although a psychological intervention (supportive-expressive group therapy) did not prolong the survival of the women, it improved mood and the perception of pain, with a greater effect being found in those women who were more distressed at the beginning of the intervention. Temoshok and Wald (Reference Temoshok and Wald2002) analyzed the methodological issues in the Spiegel et al. and Goodwin et al. studies (including issues of sampling, randomization, interpretation, and the adequacy and validity of psychosocial constructs and measures) to assess what might be causing these changes and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to be able to generalize from either study for or against the notion that psychosocial interventions can affect survival in breast cancer. Other studies have reinforced the benefit of complementary and alternative medicine approaches on spiritual well-being and quality of life, pain, anxiety, and depression. For example, Targ and Levine (Reference Targ and Levine2002) found that both standard cognitive-behavioral group work and meditation, imagery, and ritual were beneficial to women with breast cancer in terms of psychological variables, but their study does not report medical outcomes.

One aspect of psychosocial interventions that may occur close to the end of a patient's life to give the patient greater choice over where the death and dying occurs (home or hospice) involves a brief admission to the hospice or attendance of a course of focused sessions in the Day Therapy center. The patient's symptoms can be brought under greater control and psychological, total pain issues, and relationship/familial issues can be addressed. This may result in an improvement in quality of life for the patient and enable him or her to return home or it may clarify the patient's wish to stay in the hospice. Either way, this can result in an improved bereavement experience for the family caregivers after the death.

While these debates on psychosocial interventions continue, we wished to introduce a new approach into the Day Therapy setting that could potentially have a beneficial effect on the patients' quality of life. We expected the effect to occur as staff and patients completed a brief questionnaire together, anticipating that it would facilitate the discussion of problematic areas and impact on integration and communication with their family and caregivers. This article outlines the implementation of the Mood and Symptom Questionnaire (MSQ) currently in use at a Supportive and Palliative Care Centre in the United Kingdom and describes the effects on patients and the staff.

METHOD

How Was the Tool Developed and What Are Its Objectives?

The MSQ was originally designed by members of the hospice Complex Pain Management Team to address some of the issues that the McGill pain questionnaire (Melzack, Reference Melzack and Metzack1983) omitted. It has been elaborated through further use in the unit and consists of visual analog scales covering 10 psychosocial issues (worry about pain, expressing feelings, anxiety, frustration, irritation, anger, control, depression, worry about loss of dignity, and intimacy). Visual analog scales are particularly appropriate for measuring the intensity or magnitude of sensations and subjective feelings and are often used in pain research. Each scale usually consists of a straight line of predetermined length with a short, easily understood phrase at each end that describes the variable being measured. The questionnaire has been used since 2004 primarily as a clinical tool in both the Day Therapy and In-patient settings and data are reported on the 75 patients who have completed it so far. There was a very rapid acceptance of the MSQ as a standard clinical tool in the Day Therapy setting by both the staff and the patients and this article represents an initial evaluation of its use in that setting.

The patient and a staff member complete the form together so that the visual analog scale can be marked and, at the same time, issues can be discussed in greater depth if the patient shows a willingness to do so. Verbatim comments are written down on the form. Responses to the questionnaire can highlight patients who need specialized psychotherapeutic interventions or family work. These interventions can be performed by a range of individuals within the team depending upon the level of input needed. Other issues that are highlighted as problem areas can be dealt with by focused work in an individualized program (often 12 weeks) in the Day Therapy setting.

The Setting

In common with other palliative and supportive care centers, the Day Therapy unit offers a safe, relaxing environment where the patient can meet with people who are coping with similar life changes. It allows space to be oneself and express any fears or anxieties safely and in confidence. The Day Therapy Team consists of six therapists (complementary and creative therapists, occupational and physiotherapists, staff nurses) and volunteer helpers. Counseling and spiritual carers are present and there are a number of complementary and creative therapies available in addition to nursing, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy assessment and support. Patients attend Day Therapy once a week and are organized into approximate age groups attending on different days so that a younger, older, and middle-aged group can be together.

A key aim is the management of anxiety, breathlessness, fatigue, and pain, addressed through relaxation, massage, psychosocial interventions, and individualized creative work. Each patient follows a personalized intervention program in order to build on areas of good coping, reduce maladaptive coping, and address relationship and family issues.

The patients in the study ranged in age from 18 to over 80 years old. There were more women than men in the group (n = 25 men). In keeping with the ethnicity of the local area, they were largely Caucasian. Few patients refused to complete the questionnaire; one might speculate that this is a reflection of the fact that patients seen in Day Therapy are at a less advanced stage in their illness than in-patients and have more psychological resources available.

RESULTS

The use of the MSQ was threefold. First it was used to record patient responses to a series of questions. Second, it facilitated discussion of the issues between staff and patients and also in the wider patient discussion groups. Third, it proved to be a very useful staff training tool. In this section we outline our preliminary evaluation of the tool by looking at changing patient scores over two time points with descriptive statistics and with a clinical vignette of a personalized intervention. We also look at the patients' comments to assess validity of the tool, and we end this section with a second clinical vignette to show its use in staff training.

Descriptive Statistics for All Patients

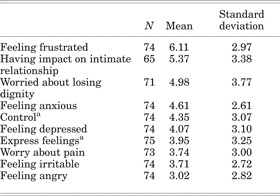

The MSQ consists of a series of 10 visual analog scales asking about pain, expression of feelings, anxiety, frustration, irritability, anger, control, depression, dignity, and intimacy. Responses are recorded on a 0–10 scale. If a patient has completed the questionnaire more than once, then the baseline responses can be compared to later scores to assess change. Table 1 shows the 75 patient responses at baseline, showing that the scores ranged from highest for “feeling frustrated” to lowest for “feeling angry.” Other constructs that are moderately high are the impact of the illness on intimacy, and worries about loss of dignity. These scores are represented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Mean scores on constructs, time 1, n = 75.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

a aScores on two constructs reversed so low score is always better.

Changes over Time

Where patients have completed two MSQs their responses can be plotted at two time points to assess change. This is usually done at the beginning of the 12-week program and at the end. Figure 2 shows how responses have changed following interventions for 20 patients who have completed two MSQs. Change scores are significantly different for two constructs: Feeling Frustrated (p = .011, X = −2.537) and Worry about Pain (p = .017, X = 2.396).Footnote 1

Fig. 2. Mean scores at two time points, n = 25.

A clinical vignette can also show how a patient's thoughts and feelings may change between two time points following an intervention, and this example also illustrates the difficulties of working with patients in declining health.

Clinical Vignette 1

The MSQ responses for this patient were recorded over a period of 3 months nearing the end of her life, and they reflect her increasing frailty and advancing disease.

On the first questionnaire, the patient indicated that she felt panic-stricken and extremely depressed (both marked at the most extreme level). Although she said that she expressed her feelings well, she was actually unable to engage in any conversation about her psychological state or the cancer or make any further comments about the questions. In light of these MSQ responses, interventions were planned to address the two most worrying areas relating to panic and depression with recognition that she might not be as good at exploring and understanding her feelings as she thought.

During her Day Therapy attendance, she became able to talk more about her situation and become more reconciled to her death. She developed good anxiety management skills and, most importantly, she became able to talk with family about the cancer.

The second questionnaire showed that worry about pain and levels of anxiety and depression decreased, a good result from the targeted interventions. Levels of frustration, irritability, effect on intimate relations, and worry about losing her dignity had, however, increased. She felt less in control of the situation and was expressing her feelings less. Her level of anger was unchanged. On the face of it this does not seem to be a good outcome of treatment; however, when we look at it in more detail, it became clear that there had been a major shift in her perception of her situation.

Her levels of frustration and irritability had increased but she recognized that this was because the disease was progressing and she could now do less. Her level of anger was the same but had a changed quality that was more bearable. She used to be angry because of the illness but now it was at herself because she couldn't “do things”. She felt far more out of control of the situation and this was indeed reality. Although she felt that she expressed her feelings less, that was linked with the fact that she no longer socialized much. She had always been very sociable but no longer felt like it and was less able. She was, however expressing her feelings in more depth with her family.

Finally, the impact of the illness on her intimate relationships had changed, but this was in a positive way because she said, “I feel closer to my family because I am now able to sit them down and talk to them with lots of hugs and kisses.”

She died shortly after this but without the panic and extreme depression that had been recorded at the first time point.

This patient's responses accentuate the clinical value of the questionnaire and highlight that they have to be interpreted in light of the clinical picture in relation to a single patient. They are not meant to be absolute quantitative measures that can be used for interpatient comparison, although in the broadest terms we can see some improvement in some constructs across the larger group. In this case, they were of value in identifying and targeting those problems causing most distress to someone with little intervention time remaining, thus enhancing quality of end of life.

Patient Verbal Responses

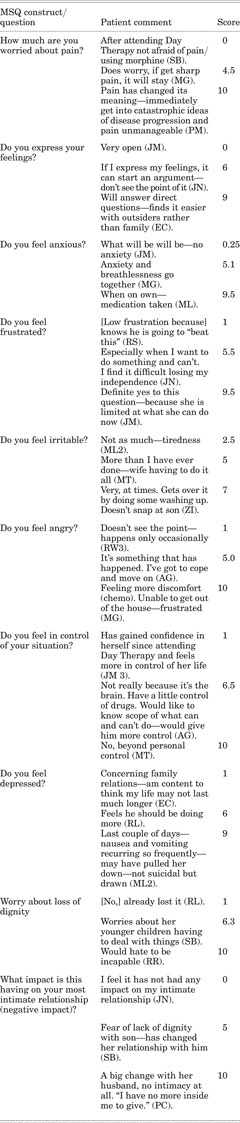

We have begun validation of the questionnaire by assessing whether patient responses broadly correlate to the scores on the questionnaire. In Table 2, illustrative high, low, and medium score quotations for each construct are shown to demonstrate how patients' comments are reflected in a numerical score. For two of the constructs (control and expressing feelings) the scoring was reversed so that a low score is indicative of the positive end of the pole.

Table 2. Example comments from patients (low scores reflect positive attitude)

A Staff Training Tool

In the early stages of its implementation, the staff had difficulty seeing the value of the questionnaire, but with training and over time, they have not only seen its value in facilitating discussions, but they have requested additional meetings with the medical psychotherapist in order to discuss the patients' responses on the MSQ. We have subsequently realized that the staff rapidly increased their knowledge and understanding of psychological issues related to the patients' total pain experience by working on and discussing the questionnaires with colleagues and more experienced staff.

Once a month, staff members meet as a group with the medical psychotherapist, who has a psychoanalytic background, to discuss any patients whom they identify as having particular issues that need to be addressed. Occasionally the staff notices clear dissonance between the score on the visual analog scale and the emotion that the patient is displaying either openly or subconsciously. Prior to the completion of the MSQ as a standard procedure, these dissonances were not always noted or picked up. The medical psychotherapist may well be able to identify ways for the Day Therapy staff to intervene and move forward with the patient. She or a psychological therapist with appropriate experience may arrange to see the patient one on one for a number of sessions if this is appropriate. The following vignette illustrates the impact of the medical psychotherapist's involvement on individual case management.

Vignette 2

While reviewing completed forms with Day Therapy staff, one questionnaire stood out as it was undated, unsigned, and filled in less fully than the others. Specifically there was no comment of any type on it, neither patient quotes nor staff notes. In addition, the patient had been offered 6 weeks of Day Therapy sessions rather than the usual 12, as it was felt that she would not make use of the time.

These discrepancies were pointed out to the staff and queried. In response they described a patient who had been referred as palliative with advanced COPD, but who was not as breathless as would be expected and was only rarely using her oxygen. At home she spent all her time sitting down being waited on, and in Day Therapy she did not engage, was very passive, and never moved from her chair. She was clearly getting under the skin of the staff and they were angry, as they felt that she was taking up a valuable place inappropriately.

The intensity of the staff response was extremely unusual. The psychotherapist involved considered that a psychodynamic explanation could be relevant and that it related both to staff views and to the psychological state of the patient. In psychodynamic terms, the hypothesis was that staff members were responding to projections from the patient who was unconsciously afraid of facing her painful life situation and wanted to avoid thinking or talking about it.

It is of note that she had been on antidepressants for some time, but, despite changes in formulation and dose, there had been no clinically significant change in her presentation. The patient had been similarly distant at a previous hospice. By unconsciously encouraging the staff to dislike and dismiss her, expect nothing of her, and to leave her alone, she was able to remain unchallenged and unforthcoming.

This possible interpretation was discussed with the staff, and a new treatment plan was subsequently put into place. The patient was then offered the full 12-week program. The staff approach was to actively challenge her passivity, for example, by getting her to walk down to the tea room herself rather than allow her to be waited on by staff or other patients. Psychologically, her expectations of both illness and quality of life were also challenged and alternatives explored.

By the end of the program, she was engaging more with staff and patients. She now walked into and around the hospice whereas previously she had used a wheelchair. She was able to talk to staff about her illness and about difficulties within her family. She was also talking more freely to her family and was being less demanding of them. She had initially been referred because her husband was not coping at home, but he now felt more able to manage and had time to give to their daughter who was also ill.

She confirmed the psychodynamic hypothesis in part by stating that she did not like to talk about things that were unpleasant and caused her distress. She was now able to tell her specialist respiratory nurse that she did not need oxygen and she felt happier and ready to move on. The staff attitudes had also changed significantly and she was no longer getting under their skin.

These changes were reflected in the scores on her two questionnaires, with eight scales showing a positive change at the second time point. In addition, the MSQ was fully dated and annotated, and the patient was identified by her abbreviated Christian name, which she prefers to use, indicating greater patient engagement and staff empathy. The notes showed her articulating her worries and anger and indicated how she was more able to think about her family.

There was one construct where the change was not positive:

Depression set in and I felt suicidal. This coincided with moving—felt left. I move around as much as I can without causing discomfort. I don't see the point in causing discomfort.

This is an interesting comment. On discussion it became clearer that the “moving” and “felt left” were to do with a change of location—she moved house to be near her daughter and this seems to have precipitated depression and loneliness. She then links this house move with moving parts of her body—a major problem in management was that she did not move from her chair. The two have been psychodynamically and psychosomatically linked.

Clinically the experience of staff and family was that she was, in reality, expressing feelings better. Psychodynamically, this actually fits, in that, if she was trying to unconsciously deflect any exploration of her feelings, it would be a valid psychological defence to believe that she already was in touch with and expressing her feelings adequately, which therefore did not need further attention.

In challenging her immobility and encouraging her ability to walk and move, the staff was also helping to treat her depression. She also used the term discomfort, which can be seen to have two meanings, as physical and emotional discomfort, and this links back to the original psychodynamic hypothesis. The “felt left” comment also has a link with a sense of abandonment by the medical services, which she described on admission. Her memory of the previous hospice was that she had seen a doctor on every visit, which was not happening here. This was not the case in reality, as we discovered when we liased with them.

Thus, the MSQ also gave some understanding of the psychodynamic/psychosomatic situation, which could then be used in planning care.

DISCUSSION

First, these findings indicate that the MSQ is a useful tool with a number of different foci. The numerical data (validated effectively by the verbatim patient responses) indicate the scores for the group at a number of time points on key constructs. It is interesting to note that these are low; only at one point do they go above 6 out of 10, and the mean scores for most constructs are below 5. This is indicative, perhaps, of where the patients are on the illness continuum when they attend Day Therapy. Although they are terminally ill, having gone through a number of prior difficult transitions involving hope of a cure and repeated disappointment and decline, they may have become more accepting.

When patients have completed the questionnaire more than once, it is possible to look at changes in the scores on constructs over time. It is interesting to note that there is some change occurring notably in feelings of frustration and worry about pain. This may reflect the positive outcome of the interventions in Day Therapy. That the other constructs have not changed to a significant degree over the time or, indeed, that one or two have risen slightly (impact on intimacy, loss of dignity) is not itself negative, but it shows an expected change, bearing in mind the increasing illness and further decline in health.

A second focus of the tool is in clinical work, and here the main value of the questionnaire comes through the discussions that patients and staff have. These discussions start at an individual level, as indicated by the comments recorded by the patients, and indicate their willingness to talk about the issues raised through working on the questionnaire. There is a secondary benefit, too, to all the patients; these initially individualized discussions can be extended to a group level if appropriate, so everyone benefits from the open atmosphere.

Discussions about sex and intimacy are often hard, even for people with chronic illness (McInnes, Reference McInnes2003), and extending these discussions to a palliative setting can be especially difficult, as it may often be perceived as a taboo subject (Hordern, Reference Hordern, Aranda and O'Connor1999; Hordern & Currow, Reference Hordern and Currow2003). As Cort et al. (Reference Cort, Monroe and Oliviere2004) note, however, it is essential to regard sexuality and intimacy as fundamental, integral aspects of palliative care.

In our work, the staff often noted that the question that was asked about intimacy was initially misinterpreted. The question was often perceived as being about sex, which can be significant for many patients, and so it was sometimes important to be able to discuss this issue further. This was an area that was sometimes difficult for the staff to raise, yet seeing a question on paper in black and white allowed this to happen more naturally if the patient felt it was something they did want to talk about.

The question about intimacy is not specifically about sex, though, and it can also be about physical or emotional togetherness that does not involve sex. This conflation of the two elements of intimacy is something that can then be discussed with patients with very beneficial results. The intimacy question sometimes highlights problem areas for patients, allowing them to raise support needs or worries and ask for advice. Alternatively, it shows that for some, the illness has brought the family closer.

Another essential topic is dignity (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002; Enes, Reference Enes2003), which may also be difficult to raise without specific prompts or a designated intervention such as the Dignity Psychotherapy intervention (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2004). The importance of addressing dignity is acknowledged in the hospice by the inclusion of a question on the MSQ and through the intervention of the Rosetta Life project, which allows patients to record important aspects of their life history in whichever way is most appropriate (written, oral, artistic, musical, etc.) as a means of forging a link between creative practice and spiritual development as an essential principle of holistic care (see www.RosettaLife.Org for more informationFootnote 2).

As a clinical tool, the MSQ may be able to identify other issues that may be addressed in a straightforward manner, and so it has pragmatic value. It is not always necessary to have high-level psychological interventions to make a big difference to patients' lives; small things can be addressed that have a big impact. Bearing in mind that the U.K. National Health Service is resource poor in terms of personnel, time, and money, a tool that brings out problems that can be addressed by the team is of great value. This was illustrated by Vignette 1.

The patients varied in their ability and desire to respond and open up about the issues raised on the questionnaire. Mostly, if they felt secure, they elaborated on a problem area. On other occasions the patient curtailed the discussion element of the process and his or her responses were given in the form of numbers only. We sometimes found that patients felt more willing to open up and discuss problem areas on a second or third occasion of completing the form. Once the use of the tool had been established, we tried to ensure that an attempt was made to have the same member of staff assist with the questionnaire. This allowed for a discussion with the patient to be focused on changes over time and on what had brought these changes about.

Third, related to this last point, the use of the tool to raise the knowledge and skills base within the team has been very important. We have seen that although the staff was initially unsure about introducing the tool within the Day Therapy context, believing questionnaires and open discussions about these issues to be inappropriate with dying patients, the staff began to not only freely use the questionnaires but they also acknowledged the value of it and have incorporated some of the psychological constructs into their own team or individual work with patients as a matter of course.

CONCLUSION

The MSQ has proved to be of value in a Day Therapy setting in a hospice in the way that it opens communication between the patients and the staff and also between patients in group discussions. The willingness and ability of both patients and staff to discuss issues such as intimacy, fear of pain, and loss of control has improved since the introduction of the tool in 2004. Its use when patients are coming to terms with the inevitability of their illness and decline may prove well timed and patients still have a number of weeks during which the difficult issues can be explored further.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge all the patients and staff at Arthur Rank Hospice who have contributed in their different ways to this article.