“A conjur woman, they say, can change reality . . .”

—Romare Bearden, 1964Footnote 1Introduction: “Like a ventriloquist, with his fist in the speaker's back”Footnote 2

The strange power of sample-based hip hop remains enigmatic some thirty years past what many see as its heyday. I sit here now in 2020, headphones pulled tight, reacquainting myself with a song from that period: K-Solo's “Everybody Knows Me” (1990). In some senses, the production, by Parrish Smith of EPMD, is unremarkable in the sweep of innovation that consumed its moment.Footnote 3 Responsible for no great aesthetic pivot or shift—the reign of the James Brown sample, for instance, or the densely layered “wall of noise” aesthetic popularised by Public Enemy—it has evaded the historiographer's compass. Yet, absorbed now in the economy of these dark shifting layers, I hear this record as in its way exemplary. If, as ethnographer Joseph Schloss observes in his book Making Beats, the sample “flip” (i.e., the process of “substantial alteration of intellectual material”) is both a core ethical responsibility and aesthetic value in sample-based hip hop, drawing value in part from the imagination with which a source is recast, “Everybody Knows Me” is, I am struck, a model of this will to transform.Footnote 4

Interweaving fragments from at least five songs diverse in genre, mood, texture and tonality, the production seems to transform the air around its elements, creating from them improbable unity. Most conventional, perhaps, in relation to hip hop's foundational priority for the break,Footnote 5 I hear Joe Quarterman and Free Soul's “I'm Gonna Get You” (1974), a bright, fast-shifting, major key psychedelic soul track, from which Smith takes a measure of tense violin trills and pushes them right back in the mix.Footnote 6 In Stevie Wonder's whimsical “Boogie on Reggae Woman” (1974), he finds an ominous bounce of electronic bass cleaved by a hi-hat that sounds to me like a Geiger counter. He cribs a James Brown “Watch me!” scream (“Super Bad” [1970]) and relieves Steely Dan (“The Royal Scam” [1976]) of a single doomy grand piano hit. The layers coalesce and subtract in taut antiphony, collaged against jarring orchestral stabs and jabbing ghost notes in a 104bpm drum machine pattern. Then, every verse or so, Smith deploys a blast of heightened tension: a one-bar Fender Rhodes piano phrase borrowed from Bob James's “Valley of the Shadows” (1974), which, paradoxically, acts as a moment of relief in its original.

The point is not that “Everybody Knows Me” creates a stylistically cluttered fusion music from these elements—a jazz-funk-psychedelic-soul-free-rock-reggae-Moog-rap. It manifestly does not. Smith sublimates these origins, even while their fragments are obviously present. Rather, taking his artfully chosen moments of borrowed tension, Smith imagines them into a new vision: a track that seems to magnify particular qualities in the MC's accompanying revenge fantasy. So, while, lyrically speaking, K-Solo serves comeuppance to past wrongdoers in the form of their having to witness his rise to fame (a common hip hop trope), the beat lends his words a menacing cinematic verité—an effect markedly different from Biz Markie's similarly themed but goofy “The Vapors” (1988). We feel the internal torment and psychological isolation driving Solo's rise as the pointillist disharmony of “Valley of the Shadows” pans ear to ear. In this much, Smith's arrangement perhaps recalls the internalised conventions of film scoring, where disharmonious string sounds, dark weights of minor key sonic matter, the sudden introduction of clashing harmonic and timbral registers, and the disorienting use of the stereo field, are used to evoke fear and unease—hear, for instance, Quincy Jones's In Cold Blood (1967). In no small part due to this sonic environment, we are invited to hear Solo as a man under siege: one last-straw from becoming a modern-day Bigger Thomas, even as he appears to reach for the top.Footnote 7

That this foreboding mood is in part forged from source materials as playful and buoyant in their original as “Boogie on Reggae Woman” and “I'm Gonna Get You” is both remarkable and testimony to the uncanny powers of transformation that, following from Schloss, I want to argue were at the heart of rap's collage-based aesthetics in the golden age of hip hop sampling. Like the best of his peers, Smith's multi-layered borrowing all but changes the weather, and, perhaps, metaphorically, we could argue it does. But can we, and is it appropriate to think of this, I wonder, as a kind of magic?

The Politics and Poetics of Conjure: “Crazy in tempo with the universe”Footnote 8

In this article, I want to reconsider these collage-based approaches to borrowing, which prospered in the relative sampling free for all of 1988–91 and still inform sample-based producers on hip hop's underground today,Footnote 9 as part of a deeper and politically grounded history of transformative Black American art and expression. Thus, while Adam Krims memorably described the disorientations of sample layering as the “hip-hop sublime,” my approach is to view them as a particularly Black American kind of alchemy.Footnote 10 From this perspective, the collage-based juxtapositions and dramatic transformations of reality effected in such recordings—their alternative worlds often only more immersive in the LP-length flights of invention some of their producers achieved simultaneously reimagining the hip hop album form—reflect the deeper transformative current in Black American history that Theophus Smith theorizes as “conjuring culture”: a tradition of quasi-magical transformation born of virtuosic imagination and connection making, and saturated with a politics of refusal and becoming.Footnote 11

The sample-based producer, like the conjure woman of Romare Bearden's epigraph, not only perceives new syncretic possibility; s/he quite literally changes reality. And, as with other Black American bricolage-based art—from Bearden's photomontages and jazz pianist Bud Powell's Afromodern refigurations of genre and pianism, to Jimi Hendrix and Marvin Gaye's impositions of Black subjecthood on “The Star Spangled Banner,” painter Faith Ringgold's scathing subversion of the US flag, and the fantastical repurposing of found objects in performance artist Rammellzee's “Garbage Gods” body armor assemblages—this will to transform is political.Footnote 12

For sure, it does not always involve explicitly political statements, the kind associated with the sometimes too neatly dichotomous idea of “conscious rap.” What I have in mind is more like the politics of virtuosity Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. locates in bebop, with its self-fashioning “virtuoso geniuses creating fanciful sound flights”; or the cultural production Richard Iton and Michelle D. Commander both term the “Black Fantastic,” its “flights of the imagination,” according to Commander, providing “powerful tools by which many African-descended communities have sustained themselves.”Footnote 13 Here, to transform that which already exists, and to do so in ways that dazzle with seemingly impossible wit and invention—such being a constant in Smith's idea of conjuring culture—is both to assert an artistic identity, and to display a brilliance that symbolically, and in some regards literally, negates the negations of white supremacy.Footnote 14

As with the concept of fugitivity in recent Black American cultural studies, this will to transcend the gravitational pull of existing reality and to reveal one's humanity with artistry and stylized aplomb is, arguably, “first and foremost . . . a practice of refusing the terms of negation and dispossession” that have been imposed on Blackness since the Middle Passage.Footnote 15 To this end, bell hooks describes the brilliance of Afromodern male artists like Bearden, Louis Armstrong, and John Coltrane as “alchemical,” transforming “their pain into gold . . . [and] using their imaginations to transcend all the forms of oppression that would keep them from celebrating life.”Footnote 16 The parameters here are both internal, creating a space where Black artists are able to be “self-defining,” and external, in that the impact of their art can “transform a world beyond themselves.”Footnote 17

In Smith's idea of conjuring culture, bricolage-based transformation becomes the guiding metaphor for a similar politics. At its most literal, Smith sees conjuring—the Afro-magical medicinal practice used as a survival strategy during slavery—as a form of literacy and meaning management, a reading of the world of objects and signs for alternative uses and meanings, as in the conjure doctor's therapeutic assembly of symbolically meaningful materials (e.g., “herbs and roots, powders and grave dirt, insect and animal products . . . human body effects . . . clothing, fluids and other paraphernalia”).Footnote 18 Interrogating these repertories for recombinative possibilities, the conjuror uses a feat of the imagination to correlate a new “system of correspondences.”Footnote 19 The desired transformation of reality not only registers in the changes to the objects and their relationships, but also in an enactment of therapy arising from the process: the upliftment of spirits, the shamanic stimulation of some new insight, the opening of a new frontier of self-belief, a reinforcement of community, etc.

For Smith, this “conjurational” impulse has remained at the heart of a sophisticated centuries-long cultural and hermeneutic tradition central to Black Americans’ quests for transcendence. Encompassing “black people's ritual, figural, and therapeutic transformations of culture,” this impulse has been continually reinvented up to the present day.Footnote 20 If Smith's interest here is primarily theo-political—the syncretic mythopoetry of the Nation of Islam, for instance, or the sermons of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, both of which “conjure God for freedom”Footnote 21—he argues the same processes take place across Black American aesthetic culture, including in those forms that are secular, modern, and commercially distributed.Footnote 22

To illustrate this by reference to an earlier musical generation, consider, for instance, the magical space created in Curtis Mayfield's performance of the Carpenters’ “We've Only Just Begun.” A combination of productive ambiguity, contextual cues, and culturally embedded Black performance tropes seems to turn this ubiquitous romantic pop ballad into a fortifying anthem for post–Civil Rights Black freedom.Footnote 23 As with other conjurational performances, this transformation at once seeming impossible, yet somehow inevitable, creates an ecstatic space and an affirmation beyond the one contained in its coded message. This rests on the imaginative facility of the act itself; in the elegance of Mayfield's transliterative flight, the sense it achieves of defying the inevitability of, and perhaps even superseding, a song already taken to mean one thing by millions of Americans. In conjuring the Carpenters for freedom, Mayfield thus recalls the same “mental and creative prowess” with which Ramsey Jr. argues bebop was able to counter dehumanizing white supremacist messages about the supposed unreason of Black Americans.Footnote 24

I want to explore the idea that the sample-based producer at this key hip hop juncture did something similar. Indeed, with bricolage the crux of their method, it is tempting to see key producers as prime exemplars of conjuring culture; as the architects of what Smith might term “ecstatic” musical spaces that “exceed normal conditions,” their groove-based collaging of fragments that are recognizable as already having existed in another form, stimulating an uncanny sense of “standing out from oneself.”Footnote 25 Crucially though, I want to suggest there were other changes simultaneously going on in hip hop from 1988 to 1991 that provided a kind of multiplier effect. If these conjurational feats of the imagination were able to transform one's mood at the song level, hip hop's forceful emergence as an album form from 1988 engineered them to take flight. In this period of unprecedented innovation, the same producers innovating sample-based beat-making conjured the album form for new artistic possibilities. They pushed toward song suites and concept albums. They employed structuring conceits like the skit,Footnote 26 and sound design tactics mimicking those of the cinema. Creating an absorbing immediacy, the sample-based rap album achieved a more encompassing sense of lifeworld,Footnote 27 and became a rich conduit for the imaginative virtuosity of the hip hop generation.

For innovators like the Bomb Squad (Public Enemy, Ice Cube, Son of Bazerk), Prince Paul (De La Soul), and others, the rap album was now often “more” than just a rap album. It could at once take on the characteristics of a radio show, a simulated game show, a talking comic book, a picaresque novel, an Afrofuturist vaudeville, or a visit to the movies, and, through any of these, invoke a multitude of stories and critiques from marginalized young Black perspectives. The rap album thus became an experimental intermedial experience as well as an intertextual one; and, crucially, often a narrative form in a quite explicit sense. The result, I hope to demonstrate, was a multilayered artform that revealed a similarly multilayered Black genius, the parameters of which are conjurational.

Introducing Daniel Dumile: “Bow! Look mom no hand / Studied black magic for years out in no man's land”Footnote 28

Taking these ideas as my starting point, I want to explore the transformative poetics of a frequently overlooked album from 1991, KMD's Mr. Hood. Indeed, plenty of albums already canonical of this experimental moment would make fine case studies. Platinum certified records like Public Enemy's It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988), De La Soul's 3 Feet High and Rising (1989), or Ice Cube's AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted (1990) all conjure distinctive sonic worlds with a variety of mood-altering effects. And, like Mr. Hood, their fields of vision accumulate song-by-song, fragment-by-fragment in prodigiously inventive bricolages that never lose sight of the core pragmatic value to sound “good.”Footnote 29 So why dwell on Mr. Hood, which sold only in the region of 130,000 copies and has never been subject to major reassessment?

The answer in part is subjective: despite its relatively small profile, I consider Mr. Hood to be, in some respects, the most ambitiously imaginative album of its era and a paragon of wit in sample transformation. My reasoning for this will become clearer. The other important reason is that the album has cast a long, but little acknowledged, shadow on hip hop. As the group in which a teenage MF DOOM (born Daniel Dumile in 1971 and deceased in 2020, but in 1991 known as Zevlove X) first recorded, KMD's Mr. Hood marked the introduction of an MC/producer who came to exert an outsized influence on underground rap. During his lifetime, Dumile, who debuted as a solo artist with Operation: Doomsday in 1999, was variously described as a “folk hero” for “disenfranchised hip hoppers” and as having earned a “cult-like following” with “hyper-imagist raps” that blend “Old English chivalry and pop dustbin references.”Footnote 30 As rap's best-known maker of concept albums, plotting a course through a variety of non-linear ideas, he consistently displayed the kind of multilayered genius I am concerned with here.

Certainly, hip hop has ubiquitously embraced the language and imagery of magic and, by extension, the super-heroic, but Dumile did so more signally than most. His solo output, cloaked in layers of self-aware persona play, conspicuously mined the fantastic worlds of Marvel and Godzilla for metaphor. It draws too on a variety of secret knowledges, including the “Astro Black” mysticism of Sun Ra. Moreover, framing his creative process in quasi-supernatural or shamanic terms as coming from a “[zone] somewhere beyond; like past the mind,” he appeared to view himself as a conjuror of sorts.Footnote 31 Invoking the altered state of his ideal listener, he suggested his motivation in making music was to create moments of transcendent wonder:

[I see it] the same way a magician would get you to go “Oh, so how did you do that?!” Like somebody pulls a trick and everybody's smiling, that's the joy of it. … That's what I'm here to give them: the feeling to be about to smile.

By constructing an audacious musical event, as he does when he flips an unexpected sample, juxtaposes samples from styles deemed incompatible, or verbally collages an archaic English phrase into a Black New York linguistic flow, Dumile seeks to create a transformation of spirit in his audience and enhance his own status as a performer of magic with this disruption of reality. This is the mark of a conjuror, and it defined Dumile's output.

Critics have almost universally conceived this second act of Dumile's career as a break from his KMD past, in part because it followed a wilderness period of personal upheaval that began with the 1993 death of his younger brother and partner in KMD, Dingilizwe Dumile, a.k.a. Subroc. In crucial respects, though, Mr. Hood is a prototype. Conceived primarily with Subroc with the input of a third vocalist Alonzo “Onyx the Birthstone Kid” Hodge under the influence of the surreal radio montages of early-1980s hip hop broadcasters the World's Famous Supreme Team, Mr. Hood is the progenitor of DOOM's magical style. Above all, it predicts the phantasmagoric use of samples from cartoons and other children's sources on solo albums like Operation: Doomsday and Mm..Food (2004). In this approach, verbal samples are rarely just sonic color. They become an integral part of a record's musical aesthetic and meaning-making.

In this much, some of the most strangely moving passages in MF DOOM's early output come when Dumile encodes hammy dialogue samples from the Fantastic Four television series telling the story of disfigured Marvel supervillain Dr. Doom with a poignant metaphor for his own resilience and sorrow: an oscillation of mood and perspective that creates a strange magic akin to Mayfield's conjure of “We've Only Just Begun.”Footnote 32 This surreal blurring of fantasy and reality, spun folklorically into modern Black allegories, is a Dumile hallmark, and it is fully formed and particularly audacious on Mr. Hood. “It's a lot of formulas we both came up with,” Dumile explained in 1999, reflecting on this formative period and partnership, “and Sub came up with a lot [of production formulas] that I still use today.”Footnote 33

Teenhood: “Place of rest is Doom's room where we loot the tune / And add a sonic kick boom”Footnote 34

The Dumile brothers, just nineteen and seventeen when they recorded Mr. Hood, by most accounts were symbiotic during childhood. Having moved frequently between Manhattan and Long Island, their active imaginations were hewn, partly through necessity, on a formative combination of comic books, hip hop, and Black American Islamic mysticism. The latter was encouraged by a strongly race-conscious family environment. Their father, a teacher in the New York school system, exposed the boys to thinkers such as Marcus Garvey and Elijah Muhammad. Their Muslim mother, meanwhile, raised her sons according to the teachings of Islam.Footnote 35 In the years before Mr. Hood, with a growing minority of hip hop generation New Yorkers turning to the secret knowledges of Black “street Islam” sects, this had segued into the teenage Dumile brothers tuning their minds to the esoteric knowledge of Malachi Z. York, a reservoir of ideas that continued to influence Dumile throughout his career. (York's dense mythopoetry weaves Black empowerment narratives into bold re-readings of religious texts, expressed using folkloric motifs of space travel, cloning and shape-shifting.)Footnote 36 Comics also provided an influential adolescent escape, according to Dumile. A self-professed “more nerdy kind of guy,” the Marvel Universe offered both brothers a way “to go into another world, [that was] especially [potent] when you're not in with the in-crowd.”Footnote 37

By 1985, with these preoccupations bubbling, the brothers had begun to take hip hop seriously. They purchased a rudimentary recording setup and embarked on the experimentation that would lead to Mr. Hood.Footnote 38 They spent long days in Dumile's bedroom collaging sounds and writing raps as “long insects crawled in from the lawn outside.”Footnote 39 It was toward decade's end, with an affiliation to up and coming rap group 3rd Bass, which would lead them to be courted by key golden age hip hop A&R Dante Ross at Elektra, that the brothers began to envisage an album that would unfold like a screenplay. Their ideas were emboldened by comics, which inspired the belief that “you can talk about anything, there's no [rule] like ‘you can only talk about this’ or ‘this would be too way out for anybody.’”

In 1990, to gage their potential, Ross secured KMD nightly access to SD50, the studio he shared with Geeby Dajani and John Gamble at the Westbeth Artists Housing complex in Manhattan's West Village.Footnote 40 They used the unusual creative freedom this gifted them to assemble a first draft of Mr. Hood.Footnote 41 Dumile later recalled, “we'd travel all the way from Long Island on the train, get out there like 11:30 . . . then walk through this dark-ass basement maze. It looked crazy in that building, you know, but it was fun.”Footnote 42 The results impressed Ross enough that he signed the group, though he was frustrated that their fastidiousness had caused recording to spiral over five months, effectively locking him out from working in his own studio. For Gamble, who engineered the sessions, his abiding impression, however, was of the clarity of the Dumile brothers’ vision, as their fragmentary materials emerged into the imaginative tour de force Mr. Hood:

I had no idea how the stuff they were looping was going to make any sense. But then I saw the genius of those tracks, as I watched them unfold. They were truly on some next level shit, even at a young age. It was all mapped out in their heads.Footnote 43

Released in March 1991, Mr. Hood creates an unusually rich and multi-layered lifeworld, even by the standards of this heterogeneous moment. While musicologists inarguably have tended to see rap from this period through the dominant lens of the Bomb Squad and Public Enemy, KMD offer something quite different. Public Enemy's power, we might argue, however mesmeric and formally surreal, is in the way it gestures toward reality. It Takes a Nation of Millions seems to aspire to a radical mimetic poetry. Its subject is the metaphoric Black metropolis under attack: musical loops sound as sirensFootnote 44 or whistling bombs,Footnote 45 guitars as electricity crackling in the air.Footnote 46 Meanwhile, verbal samples, taken from documentary sources, conspire to create an impression of channel-hopping verité. Loren Kajikawa has described this deliberately dissonant aesthetic as having repositioned the break “as a noisy signifier of resistance and confrontation.”Footnote 47

It would be a disservice to describe the breathtaking Nation of Millions, with its wide-reaching social praxis, as “protest music,” just as it would be to describe Richard Wright's book Native Son as a “protest novel.” However, like Native Son, Nation possesses a “brutal realism” that is visceral and all-consuming.Footnote 48 It centers the listener in the thick of a dystopian urban present among the onslaught of structural and political discontents experienced by young Black men in post–Civil Rights United States. Revolutionary praxis occupies our field of vision.

Mr. Hood, by contrast, is sly, surreal and indirect, and seemingly preoccupied with a more philosophical question about its Blackness: how are we to live?Footnote 49 Musically, developing in bold, mood-shifting strokes, it wrings a brightly hued absurdism from the jukebox Black pop of the Dumiles’ parents’ generation, most obviously, the “gritty R&B organ and guitar” sounds of acts like Shirley Ellis, Little Wink, and Booker T & the MGs.Footnote 50 The record's immediate lifeworld is a vividly realized everyday teenage urban Black America, presented as rich, many sided and superabundant with meaning. Yet, the light tone it perhaps at first conveys is a strategic deception, a form of “yessing” designed to mask more subversive intent.Footnote 51

As Dumile contemporaneously told the British magazine Hip-Hop Connection, KMD modelled the album on what he called “the Sesame Street concept,”Footnote 52 alluding to the Children's Television Workshop educational puppet show founded on the remit to “master the addictive qualities of television and do something good with them.”Footnote 53 KMD set out to incorporate “humor with education, with confrontation, with touchy subjects that people don't want to hear about.”Footnote 54 The resulting record is unique in tone—tuneful, witty, ambiguous, and caustically funny—and a picaresque satire on race in the United States, whose deceptively upbeat mood is charged with pathos and palpable anger.

To this end, Mr. Hood, more directly than most of its peers, envisages itself as a tale of sorts. If, as Ishmael Reed claimed in the 1970s, the new intermedial literary reality meant a novel could be the six o'clock news,Footnote 55 Mr. Hood retools the rap album as a kind of folklore, or as a tale told in the episodic, humorous, and sometimes magical, life-learning literary register Ernst Georg-Richter contemporaneously defined as “the New Black Picaresque.”Footnote 56 Using skits and intricately plotted transitional passages, which emerge from the fabric of the songs themselves, the Dumiles plot a compelling narrative. Part parodic redemption narrative, part meditation on teenage experiences of Blackness in post–Civil Rights United States, and overtly concerned with transcendence through self-knowledge, the album is structured around the misadventures of a mythic figure known as Mr. Hood.

This most vivid example of the Dumiles’ magical sampling praxis will be explored in more depth in the final sections of this article. For now, it is enough to note the Dumiles splice this fictive New York drug dealer to life from composite phrases subverted from a vintage language-learning LP, editing him into an episodic journey designed to confront him with his own moral choices and inspire him into upliftment. Over the course of this quest, the producer-conjurors insert Hood into a series of surreal but deadpan realist interactions that take place in sacred and profane spaces of a Black American every-town—the jewelry shop, a quasi-Islamic Black Nationalist storefront oration, a barber shop game of the dozens, etc. By journey's end, in a characteristically ironic joke, Hood can be heard testifying his redemption from the congregation of one of Black American folklore's most troped figures, the “confidence man” preacher.Footnote 57

As with the songs they frame, these narrative passages are overtly conjurational. Their virtuosic bricolage imposes a new imaginative order on what, even by the standards of its day, is a diverse set of elements. The Hood composites are put in play with KMD's own voice acting and raps, with verbal fragments excised from pre-existing rap recordings, instrumental elements from the 1968–1974 era of Black American pop, and dialogue hijacked and subverted from far and wide in twentieth century US children's culture from Sesame Street and Disney films to children's story records. Spliced into the album's song flow, these segments unfold from the cartoonishly shifting moods of the Dumiles’ song productions, a layering that might segue from what Hua Hsu terms the “slapstick funk” of choicely truncated Isley Brothers samplesFootnote 58 to historic Black sounds less commonly evoked in 1991's hip hop soundscape—humming, moaning, the blues, jazz xylophones, etc.

The resultant clashing of textures, temporalities, meanings, and media evokes a dizzying “strange magic” similar to the one Rachael DeLue finds in the collage-based recompositions of that most famous conjuror of Black American visual art, Romare Bearden.Footnote 59 Our recognition of the “literal real” in Bearden's work—that is, the fragments of photographs, press clippings, and more—at once seems to “[render] null the physical, gravitational limits of the material world,” according to DeLue, making our experience of his art “feel all the more bizarre and unexplained, enchanted even.” In this much, Mr. Hood, like the tender scenes of Black domestic life we see depicted in a collage such as Bearden's “Interior: 1969” (Figure 1), is immediately recognizable as a kind of realism; yet, it is a realism from which we are continually pulled back into a surreal recognition of its artifice, of the fragments it is composed of, and the alternative realities they once inhabited. This is why I refer to these conjurational aesthetics as phantasmagoric, inferring dream-like states, the creation of illusions, and fast-moving spectacles composed of many elements.

Figure 1. Romare H. Bearden, Interior, 1969. ©Romare Bearden Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020.

For some thinkers, such aesthetics are inherently political when performed by Black subjects ambivalently situated in US modernity. Ralph Ellison perceptively found a critique embodied in Bearden's method, which chimed with Bearden's own belief that “As a Negro” he did not “need to go looking for . . . the absurd, or the surreal,” because he had “seen things that neither Dali, Becket, Ionesco or any of the others could have thought possible.”Footnote 60 Ellison maintained Bearden's combination of techniques was “itself eloquent of the sharp breaks, leaps in consciousness, distortions, paradoxes, reversals, telescoping of time and surreal blending of styles, values, hopes and dreams which characterize much of the Negro American history.”Footnote 61

This politics of form speaks loudly to the golden age rap album generally, but particularly to the self-conscious way Mr. Hood goes about distorting reality.Footnote 62 However, on Mr. Hood this is layered with the Dumiles’ satiric stance on much of the material they sample. On the track “Who Me? (With an Answer from Dr Bert),” we hear Sesame Street's Bert, magicked for anti-racist allyship, put a hex on US culture's resilient “Sambo” archetype, instructing Zev to “pick up a crayon . . . [and] draw a circle around him.”Footnote 63 Racist artifacts such as Peter Pan Records’ 1971 story LP Little Brave Sambo are abducted from the near past of popular culture and brought to life in a magical urban reality where crack and Reaganomics complicate its protagonists’ racialized everyday dilemmas. As with Amy Abugo Ongiri's analysis of Darius James's 1992 novel Negrophobia, the Dumiles turn this material back against itself, as if a form of inoculation, “eviscerating the historical past by exposing the ugly innards of its symbolic logic, compressing time in such a way that the past is perpetually present but also perpetually asynchronous.”Footnote 64 The ghosts of US racism are thus rendered a real and taunting presence in this vividly bricolaged lifeworld, illuminating their continued relevance in the psychic landscape of late-twentieth century racism.

While these abductions from B-movies and children's media evinces the Dumiles’ hyper-literacy in 1970s and 1980s US media culture, the album is, of course, no less embedded in decades, sometimes centuries-deep Black tradition; and these histories too are embodied in Mr. Hood's soundscape. Sampled into the record's magical any-town, historic figures like Malcolm X and Gil Scott-Heron seem to take on a sentient role. Shana Redmond has compellingly described the captured “cacophony of individual neighborhood voices” in Public Enemy's “Fight the Power” as an animating force, and in a similar way the Dumiles use these voices to provoke, cajole and rally.Footnote 65 Yet, here, they are often more than the “apparitional . . . hype man” of Redmond's description.

The Dumiles’ verbal samples frequently enter into the kind of “uncanny call-and-response” between live and sampled events that Loren Kajikawa describes “granting sudden authority to . . . sampled material” in some hip hop texts.Footnote 66 This dynamic is unusually heightened in Mr. Hood's bricolage. At its zenith, the Dumiles ventriloquize their borrowed voices into literal conversations between human and sample. Not only does this produce surreal collisions of temporal and physical plains, it achieves for these voices an anthropomorphic illusion of life. Elsewhere, the relationship between sample and the internal reality of Mr. Hood's world grants an omniscient voice-from-the-skies quality as if the spiritual warfare the Dumiles believe young Black people to be under has bled into the fabric of reality.Footnote 67

The sum result is a thick, hallucinatory intertextuality that critics found particularly novel in 1991. Hip-Hop Connection played to the record's meandering, uncanny quality, describing it as “a warped walk through America's urban landscape with Sesame Street's Ernie and Bert and the idiot Mr. Hood for company.”Footnote 68 The Source, meanwhile, characterized KMD as existing in “a nether world of cartoon fantasy, bugged out Sesame Street influences, the teachings of Islam, hangin’ out with your crew, and eclectic, original hip hop flavor.”Footnote 69

Thinghood: “Oh, no! (Who, me?)”Footnote 70

In the transition from “Figure of Speech” into “Bananapeel Blues” is a soundbite of Malcolm X taken from his widely sampled “Fire & Fury Grass Roots Speech.” It offers a good example of how even the most conventional sounding verbal samples on Mr. Hood are sometimes more sophisticated than they at first seem, partly because their role is often to signal a narrative development. But this is also due to their poetic treatment. Elevating the use of phrase-sampling to a form of sound poetry, the Dumiles typically edit to transform meaning, pitch, and rhythm-texture. Taking here the starting point of X's phrase “you are nothin’ but an ex-slave,” the Dumiles perform a deceptively simple series of erasures. They repeat different configurations, teasing X's words into what we might read as a layered, rhythmically mesmerizing commentary on Black America's core ontological bind: the everyday alienation W. E. B. Du Bois termed “double-consciousness.”Footnote 71

Du Bois's analysis of Black selfhood in white supremacist culture is pertinent to a key theme in Mr. Hood's treatment of race, and worth pausing on a moment. That theme is the baffled hurt/outrage of teenage Black boys as they grapple with coming of age in a culture that reduces them to thinghood. KMD's subject here is neither the spectacular racism of police brutality nor the structural racism of political systems. Mr. Hood instead deals with US life at a mythic level. It is more interested in probing, mocking, and pushing back against, and, ultimately, in creating a virtuosic line of flight from, the pervasive, everyday ways the US's mythic apparatus finds to chip away at, and to throw into conflict, young Black people's sense of identity and self-worth.

In Du Bois's terms, this is ordinary teenhood behind “the veil,” the metaphoric optic interface that works, in Charles Lemert's description, by “blinding those who wish not to view the other [while] limiting the others in ways that affect in the deepest what they think of themselves.”Footnote 72 It is this optic and ontological conundrum, but also a strange perceptual privilege related to the conjuror's special talent for reading, that KMD are most obviously concerned with, and which Du Bois articulates with famous beauty in the Souls of Black Folk:

The Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with the second-sight in this American world—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.Footnote 73

“Figure of Speech's” refiguring of X's speech creates a key point of development in Mr. Hood's exploration of this theme and breathes new life into the song's final half-minute. Here, each phrase is repeated at two-bar intervals. The song's tuneful layering of musical fragments all taken from Le Pamplemousse's 1977 disco B-side “Monkey See Monkey Do” concurrently peel back to create an appropriately stark mood of reckoning:

This is a simple but clever conjure. By erasing the word “slave” and refiguring “ex” as “X,” Malcolm X's words are, in effect, brought to life and made to speak directly to Zevlove X (a.k.a. X) who as MC takes the lead on this and most of Mr. Hood's tracks. This seems an audacious move; perhaps as close as hip hop circa 1991 gets to inserting oneself into a conversation with God, given X's elevated standing in hip hop's popular imagination at the turn of the 1990s. Through these variant erasures, Malcolm X is made to extend his original statement into a de facto psychodrama voicing the struggle for Black selfhood. This pivots between two positions: a double-edged affirmation of Zev's self and/or of his fugitive identity as a Black Muslim (“You are X”) and an unambiguous statement of the social erasure arising from his Blackness (“You are nothin’ but an X”). As the final drum fill resolves to a rare and dramatic moment of silence in the album, the conclusion seems both bleak and total: it is futile, X might believe, to attempt to create an autonomous identity faced with the ontological violence performed by “those who wish not to view the other.”Footnote 74 To attempt, that is, to rise above the veil.

The narrative purpose here, it seems, is to set up the scathing rebuke of white exceptionalism that follows in “Bananapeel Blues.” In borrowing Malcolm X's moral authority, editing his words into a particularly stark iteration of his message, and having them emerge echoing into an emphatic rupture in the album's musical fabric, thereby embodying the ontological nothingness on which Malcolm X is made to end, the Dumiles conjure a powerful and finely balanced punctuation point in their narrative, snapping into focus the everyday psychic brutality of white supremacy.

Conjuring Hood: “Shadowbox that ass and teleport y'all”Footnote 75

In his memoir Root for the Villain, rapper and producer Jay “J-Zone” Mumford writes, “There's nothing like watching an episode of Bewitched! and hearing Dick York say something in his nerdy voice, then flipping his phrase out of context into something X-rated.”Footnote 76 Such all-out transformation of a verbal utterance, subverting both its meaning and sentiment, goes beyond the more-restrained poetic reworking of Malcolm X we hear in “Figure of Speech.” We can understand the latter as endorsing even while it diverts: a change of meaning, but not of underlying sentiment or politics.Footnote 77 What Mumford describes, by contrast, is an auditory spirit possession, a wholesale reinvention of linguistic intent, which, through creative re-reading, audaciously relocates the original speaker as a meaningful participant in an alien landscape thematically, temporally, and socially. The result is a brazen form of the “reverse troping” that Felicia Miyakawa describes some producers performing, using “snippets of borrowed material to comment on new texts and music.”Footnote 78

Mr. Hood is built around perhaps the most ambitious and imaginative example of this kind of creative re-reading in golden age hip hop. Assembling their anti-hero Mr. Hood from cleverly spliced verbal samples, the Dumiles imagine the protagonist of their morality tale entirely from fragments subverted from a mid-century language-learning LP. In doing so, the 1960s voice actor whose literal voice we hear is conjured out of time, place, and context, and resuscitated with deadpan absurdity in realist scripted action set in crack-era New York. This is a lifeworld he is made to inhabit in multilayered poetry with the Dumiles’ surreal cast of anthropomorphized verbal samples, KMD's live voice acting and raps, diegetic and non-diegetic sound effects, and a richly expressive bricolage of music samples. It is in the signaled artifice of this layering that Mr. Hood's Beardenesque strange magic goes into overdrive. We hear deliberate discontinuities of texture and temporality, of distinctions between “live” embodied presence and sonic archivality. Styles of speech and related stereotypes of race, class, and generation are thrown into playful confusion, particularly as they pertain to the accepted conventions of what it means to be “hood.”

Speaking to the sustained improvisational play that yielded their protagonist, Daniel Dumile recalled that he and Dingilizwe (a renowned hip hop community barber who earned spare cash “cutting names in the back of the head and all of that”Footnote 79) obtained the record in partial payment for a haircut. Produced by Pan American Airlines as a giveaway to enable holidaymakers to learn Spanish, Dumile said it had initially seemed “a weird record to get.”

It was a dude who'd say something in English and then say it in Spanish, so you'd know how to say it. So, it had a lot of phrases—common phrases—that you would need to maybe survive in a Spanish speaking country for a week, so that was enough.Footnote 80

Like Albert Murray's blues hero, who “uses his inner resources and the means at hand to take advantage of the most unlikely opportunities,”Footnote 81 the Dumiles began to decipher in these scenarios a wealth of material that could be taken out of context and “flipped” into comic and narrative action.

He was saying some things in English that really bugged [me] out. “I would like to buy some gold rings.” When I imagined that in my mind, I saw a hood [i.e., a street-level criminal] buying gold rings. There's another one where he says, “Your shirt is dirty”—I figured someone's frontin’ on his shirt. That's how we got Mr. Hood.Footnote 82

That such lines were delivered, not in the registers the Dumiles associated with the hoods and hustlers of the same popular stereotype they used Mr. Hood to satirize but in a clear-voiced and formal manner with a “hint of an accent,” “made it even a little bit more-funny,” according to Dumile.Footnote 83

The voice of this spliced trickster-picaro is the first sound we hear on Mr. Hood. With the composite skit/song “Mr. Hood at Piocalles Jewelry/Crackpot,” he is immediately inserted into a richly imagined everyday scenario, which quickly sets up the dramatic, sonic and social relationships that drive the album. It is important here to achieve a close sense of how the Dumiles bricolage their magical narrative between multiple layers of semiotic material. Announcing “let's enter this jewelry shop,” Mr. Hood's voice is noticeably bathed in crackle and enunciated in the antiquated mid-Atlantic American English favored by 1940s newscasters. We hear him as conventionally “white” and audibly archival, belonging to a period long since past. Though this is signaled as a work of cultural necromancy, immediately the action cuts to the clarity of a modern studio recording and a tense negotiation on the inside of the shop. A young Black hip hop generation New Yorker (Zevlove X), alive in the text, is unsuccessfully trying to pawn a “14k def bracelet” (i.e., a stylish gold bracelet). A hint of desperation plays at the edges of his voice, underscored by a tensely-coiled bassline rumbling diegetically from the stereo (a pitched down loop of the first bar of Eddie Floyd's 1968 paean to second chances, “Bring It on Home to Me”).

The shopkeeper, Piocalle, who is played for laughs with indeterminate fake-European accent, attempts to shoe Zevlove X from his shop (“This is not a pawn shop, this is Piocalle's jewelry!”). Immediately as he pauses to dismiss the unwanted hawker, a bluesy, downward-meandering two-bar guitar figure fills the space and begins to loop. In what might be a Dumilean joke, it has been excised from the aptly-titled “Hobo” (another Eddie Floyd recording). But it is also an example of how Mr. Hood's bricolage employs culturally sedimented musical tropes as “telling effects,”Footnote 84 here to cartoonishly signal Zev's broke dejection. Piocalle immediately changes his tone, however, to welcome his incoming “favorite customer,” the “white-voiced” Mr. Hood. This is the first of the aural reaction shots the Dumiles create as a device to breathe life into their reanimated protagonist and weave him into the fabric of their surreal environment.

It is in naturalistic conversation that this voice from the cultural dead begins to talk back, his surreal discontinuity apparently available only to the listener:

Hood: I would like to see some gold rings.

Piocalle: Ah yes, we have these stupid-fat gold rings, perfect for your masculine hands.

Hood: Some earrings for my wife.

Piocalle: How about these elephant studded diamond earrings, perfect for the woman of your dreams.

Hood: And a watch for my cousin.

Piocalle: Ah yes, we have a Rolex for just under three-thousand, seven-hundred and ninety-two.

Hood: That is a beautiful watch.

Zevlove X [indignant]: No, actually, it's two-thousand, three-hundred and thirty-six green!

Hood [to Zev]: Many thanks for your help.

Zevlove X: Yeah, he's always trying to jerk people.

Hood: My name is Mr. Hood. What is your name?

In the ensuing scene, as with all Mr. Hood's explicitly dramatized material, the Dumiles weave together these verbal and musical layers, mixing live and reanimated archival fragments to set up a story, which, in turn, sets up a critique. Pan-Am's original language learning scenario, almost certainly recorded with the foreign trinket-buying of (white) beneficiaries of the American Dream in mind, is thus conjured into the starting point for a satirical critique of the social destructiveness of the crack economy for Black American communities at the turn of the 1990s. Jewelry, and the two protagonists’ differing relationships to it, becomes a key piece of symbolism for their contrasting moral perspectives and relationships to society. For Zevlove X, pawning his bracelet because “this rhymin’ for nickels business ain't makin’ it,” his jewelry is dually invested with his dignity and symbolic capital as a rapper. Losing it represents a dream curtailed and his frustrated ability to provide through honest means. Negated like this by Piocalle, Zev emerges as a Capra-esque “little man” in a Du Boisian bind, an invisible outsider-looking-in on the trappings of late-Capitalist success, forced to hock this glittering semaphore of presence to pay the bills.

There is little doubt that in constructing this multifarious collage, the way the Dumiles choose, combine, and transform musical samples is responsible for creating a mood that brings out particular qualities in the action. This is not the exhilarating wall of discordant noise we hear in Public Enemy's “Welcome to the Terrordome” or the tense paranoia of K-Solo's “Everybody Knows Me.” Rather, there is something self-consciously cartoonish in the way musical layers often appear to signify and lampoon in these narrative passages. The progression from the angsty foreboding of “Bring It on Home to Me” to the exaggerated dejection of “Hobo,” to the smooth resolve of Johnny Guitar Watson's “Superman Lover,” to its cruel interruption by a slapstick glissando of taunting orchestral sound effect likely excised from a 1960s sitcom soundtrack, tells its own story. It strategically constructs Zevlove X, in tune with the verbal action inside Piocalle's, as somewhat infra dig, yet determined to prevail. In this much, the Dumiles’ approach to using musical samples, while no doubt primarily oriented to sounding good, can also here be compared to the knowing performances of particular jazz musicians in the vaudevillian tradition. In that context, W. T. Lhamon Jr. describes “Jazz players’ light mockings of blues singers” such as Bessie Smith, which, as the work of Samuel Floyd Jr. reminds us, is a form of musical signifying, and this fulfils a similar purpose.Footnote 85

Similarly, “Bananapeel Blues” with its loosely rhymed vocal riffing on the analogic sermonizing of Gil Scott-Heron's “H2O Gate Blues” (1974), and its churchified vocal call-and-response, soul claps and deeply sardonic tone, is given a particular mood by its sampled blues piano arrangement. An unconventional sample choice, it tipsily rolls along in a shuffle rhythm undergirded by a booming two note sub-bass kick drum pattern, eschewing altogether rap's conventional rhythmic motor: the breakbeat. This layering of the blues, the church, and Scott-Heron (the historic bard of Black dissent) bequeaths the song a mythic “down-homeness,” creating a (cartoonishly heightened) aura of historically inalienable hard-won truth for its pro-Black message. Resolving to a surreal final minute, the Dumiles bricolage a giddying fever dream of musical sound: voices pile on voices (hollers on scats on inexpert doo-wop style harmonies), while Scott-Heron, pitched up to a cartoonish babble, is made to repeat the composite phrase, “Now tell me/how much more evidence do the citizens need?” for a full fifty seconds. Stabbing piano rolls, elastically phrased electric bass fills and clattering drum parts coalesce with this into a manic reverie. We have arrived, it suggests, at a point of thematic exhilaration.

Yet, as “Piocalles Jewelry” shows, this production of meaning is not always via the sound itself. Whether through some magic of the text set in motion by the Dumiles’ bricolage, or through a more knowing process entered into consciously, it is possible within this track, as elsewhere on the album, to find phantom meanings encoded in its sample sources.Footnote 86 As the disparity between Zevlove X and Hood vis-à-vis the symbolism of jewelry plays out, the Dumiles’ sampling of “Bring It on Home to Me” takes on a hidden layer of poignant poetry. Not only is this song (written and originally performed by Sam Cooke) composed from the perspective of someone looking for a second chance, as Zev clearly is (to Mr. Hood: “where you work at? They hiring?”). Its quest to win back an absented lover is framed by one of the more transactional tropes in Western romance—the equation of demonstrating one's love with gifting jewelry (Floyd: “I'll give you jewelry, ha! and all my money”). This subtext, and Zev's manifest exclusion to that end, throws Mr. Hood and Zevlove X into a relief that undercuts “Piocalles”’ comic absurdity. The largesse that makes Hood visible and valued in this modern US capitalist space, and Zev inversely invisible, hinges on Hood's ability to spend thousands of dollars on jewelry as gifts for his loved ones.

In this light, Zev's exclusion symbolically extends beyond matters of personal subsistence. He is, more emotively, excluded from the ability to provide, or to express his devotion through the capitalist language of love. But there is another factor shading this power play. Following a cleverly manipulated conversation of inferences that culminates in Mr. Hood apparently offering to sell to Zev a “spoon” of cocaine (i.e., a small “bump” of the drug customarily snorted from a miniature spoon), we quickly deduce that Hood's money is a form of blood money; he is a participant in the crack trade.

With this tension and its implicit critique of US capitalism, the Dumiles’ remarkable bricolage guides the listener to see in one's mind, without having to be told, the potential seductions of the street for young people, like Zev, struggling to live productive and self-defining lives. In doing this, it suggests an unexpected empathy for Hood that is consistent with the album's characteristic both/and thinking. We're enabled and even encouraged to see Hood at once as villain and victim.

In her essay “Gangsta Culture,” bell hooks forcefully argues that “mass media in patriarchal culture has already prepared [Black males] to seek themselves in the street” via its crude range of stereotyped depictions of Black masculinity.Footnote 87 It is this limiting white gaze and the associated forms of internalized racism that KMD suggest arise from it (in short, the veil) that, more than anything, the group makes Mr. Hood's focus, and attempts to exorcize in its present-day morality tale. Quickly established as the album's moral center, and a trickster figure who resists criminal temptation, Zevlove X looks on Hood with a compassion similar to that advanced by hooks, or to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s guiding praxis (as described by Charles Johnson) to “love something not for what it presently was . . . but for what it could be.”Footnote 88 The album follows Zev as he attempts to usher his new “white-voiced” friend Mr. Hood on a journey to redemption (or, a parody of redemption) delivering folkloric parables in songs across the album. These are aimed at enlightening him to a deeper self-knowledge of his predicament as a Black man in the United States; to a sense of spiritual being and self-worth; and, ultimately, to a better version of self. In these respects, if not all, Zev comes to figure the “enlightened individual black men” hooks envisions as the gangsta's virtuous opposite in late-capitalist United States,

who make no money or not enough money [and] have learned to turn away from the marketplace and turn toward being—finding out who they are, what they feel, and what they want out of life within and beyond the world of money.Footnote 89

In the album's final ironic twist, Zev's best efforts are rewarded by Mr. Hood (this figure magicked into absurd life by the real Daniel Dumile and his brother Dingilizwe) not with the Black Nationalist better self Zev envisages for him, but by his joining the congregation of the pimp-strutting trickster-pastor Preacher Porkchop.Footnote 90

The whiteness of Hood: “All these are just metaphors, they describe symbols in folklore”Footnote 91

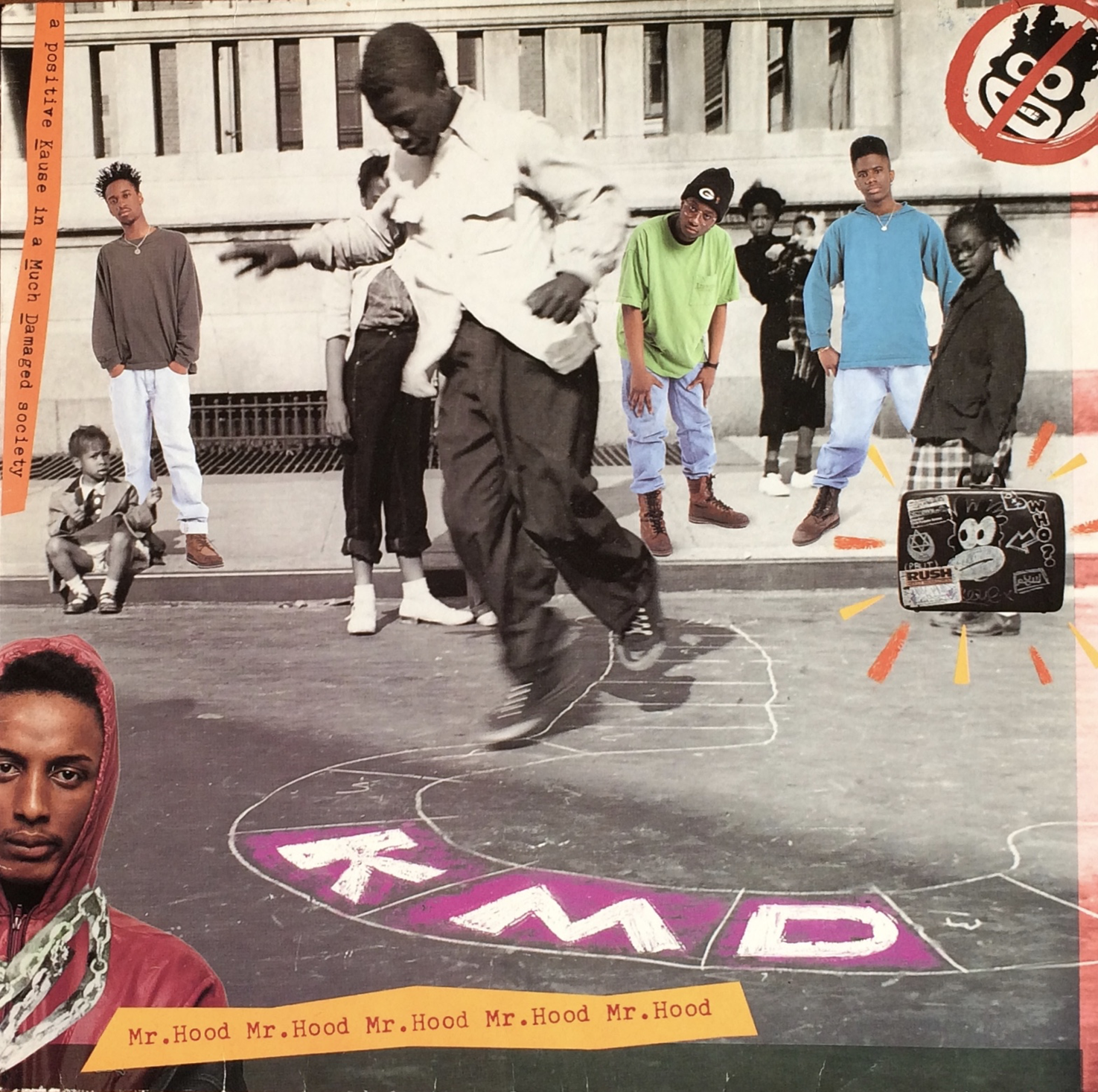

Some commentators have interpreted Hood in all these scenarios as a “clueless, white-as-starched-napkins” interloper.Footnote 92 But to do so is to miss the magical leap the Dumiles invite us to take with them, not in spite of his “white voice,” but precisely because of it. In this most audacious transformation, we are almost certainly meant to read the personhood the Dumiles conjure from Pan-Am's mid-Atlantic, mid-century, middle-class-pursuit-acting-out white voice artist as “Black.” As my analysis suggests, the other characters in Mr. Hood's lifeworld respond to him so, with Hood displaying Black cultural competencies (playing the dozens, testifying, etc.). The redemption Zevlove X envisages for Hood is also clearly conceived along Black Nationalist lines. This racialization is born out in the album's artwork which homages the Dumiles’ cultural necromancy by bringing the three KMD members to life in a Brooklyn street scene circa 1950 spliced into photographer Arthur Leipzig's Question Mark Hopscotch. Foregrounded front-left we find a fourth time-traveler from 1991: a hooded Black teen, thick gold chains montaged around his neck, the album's title ticker-taped at his shoulder. This is Mr. Hood, our “white-voiced” protagonist (Figure 2).

Figure 2. KMD Mr. Hood. Art direction: Carol Bobolts/Red Herring Design; Band photography: Arthur Cohen; Vintage photography: ©1950 Arthur Leipzig. Elektra Records, 1991.

There is a comedic pleasure, of course, in hearing the composite “your mother likes to visit the old churches” sutured in this middle-aged, stiff white voice into a game of snaps. But the class and race ventriloquism of the Dumiles’ conjure is not simply an entertaining incongruity and textural disruption. Like much in Mr. Hood, it is also perhaps a metaphor. In 1990–1991 as this visionary album was being pieced together, the mass media that hooks critiques for its horizon-limiting racist depictions of Black males had entered a particularly virulent period of antiblackness. In this historic moment, a half-decade into the social turmoil wrought in given New York neighborhoods by the trade in crack and its associated violence, hip hop generation Black Americans were frequently stereotyped as functionaries of the crack trade, collectively pathologized as a contemporary “boogie man” at the center of a wider discourse of social breakdown. Writing four months before Mr. Hood's release, in the immediate wake of 1990's Central Park jogger case convictions, Joan Didion described a thriving modern-day media discourse of teenage Black monstrosity, with news sources portraying “a city taken over by animals.”Footnote 93 The ultimately exonerated teenage Black victims of this miscarriage of justice, dubbed the “wolfpack” in the media, became a racialized lightning rod for what Didion articulated as the “growing and previously inadmissible [middle-class white] rage with the city's disorder.”

Mr. Hood recognizes the bleak continuity between this portrayal of Black people as animals in its technologized media age with the historic mechanisms of slavery, which required Blacks to be viewed as not fully human. This is reflected throughout the album's engagement with the language and artifacts of historic racism: the soundbites it attempts to inoculate us against, the historic tropes it seizes to discuss present discontents, and in its invocation of folklore, which H. Nigel Thomas pertinently reminds us was a means for enslaved Black people to “affirm their humanity.”Footnote 94 That history remains deep and always living in Mr. Hood is obvious from the ubiquity of the “Sambo” figure, which stalks the album's themes, lyrics, and imagery.

Yet, KMD's Sambo is not precisely the figure of childlike compliance seen in the historic usage specific to slave society.Footnote 95 It has expanded to a more generalized form that perhaps sheds light on Mr. Hood's surreal racialization. The important characteristic, as with Ellison's evocation in Invisible Man, is that the Sambo has internalized and enacted racist white society's ways of seeing Blackness, either becoming those characteristics or self-consciously performing them, as in Tod Clifton's subversive Sambo doll puppet show in Ellison's most famous set-piece.Footnote 96 By this definition, KMD's ubiquitous Sambo can be read as akin to hooks's gangsta, internalizing or coming to embody the kind of white fantasies about Blackness that prospered in a moment when crack put a particular pall on racist discourses of Black monstrosity. This, of course, puts Mr. Hood's white voice in a new light. Might that voice, in fact, be a surreal strategy to symbolize his compliance to the racist white gaze? Is Mr. Hood, conjured as he is from fragments, the Dumiles’ Sambo doll—a knowing, and ultimately therapeutic, performance of 1991's racist white fantasies about teenage Black boys? And, if so, what does that make the spectacular feat of the imagination that created him?

Conclusion: “Anything is possible in my church!”Footnote 97

“Taking the hump with style is the genius of our survival. Not only do we adapt, we finesse.”

—A.R. FlowersFootnote 98I have little doubt that with Mr. Hood KMD performed a vivid kind of alchemy. To riff on hooks but to fold onto others already mentioned in this article, the Dumiles employed their imaginations to take flight on this album. They used it as an opportunity to imaginatively transcend the limitations of a culture that would deny their brilliance, and which cross-threaded their own ordinary comings of age with the surreal realization that, as Black teens, society viewed them as less-than. Mr. Hood turns this pain into gold. And, in turn, it is through KMD's virtuosic, multi-layered will-to-transform—at once typical and atypical of their hip hop moment—that their own brilliance is spun into being. In their hands, rap's evolving sampling techniques became the mode through which the Black pop of the 1960s and 1970s could be conjured for comic pathos, creating a new funk that was simultaneously part cartoon. Aware too of myth's power to shape reality, they conjured the album form itself to create a new mode of storytelling: a modern-day intermedial folklore that makes KMD's fable of teenage Black transcendence feel like a Brer Rabbit of the Roland TR-808 era.Footnote 99 And, then there is the transformative wit with which they bricolaged fragments of pop culture ephemera into that tale, providing its magical textures and uncanny portals into the history of race.

In this much, KMD's reanimation of superficially banal flotsam of the American Dream to create their protagonist Mr. Hood, and to use it to speak so inventively to their own exclusion, exhibits a virtuosity of the imagination, first, but also of sampling micro-surgery. By the measure of Daniel Dumile's own aim to create moments of transcendent wonder, and of the altered states generated in Theophus Smith's conjuring culture, this creative act goes to work on the listener's spirit by seeming to perform the impossible—a core aspiration in all aspects of hip hop creativity, as it is of Black American aesthetic culture historically.

In 1993, after Dingilizwe Dumile was killed in a tragic road accident, his brother marked his wake by playing “Garbage Day 3,” the harrowing sound collage that Dingilizwe conceptualized to open KMD's would-be sophomore album, Bl_ck B_st_rds. Edging closer to the sometimes more subliminal overlapping narratives Daniel later used in his solo work, it pulls their techniques into a bad trip of babbling hard-boiled mid-century voices punctuated by gunshots and racial epithets. The aim, apparently, was not narrative coherence or satire, but, to paraphrase Ralph Ellison's famous reading of the blues, a poetic fingering of the “jagged grain” of the Dumiles’ brutalized experience.Footnote 100

“It's like watchin’ [the past three years] real fast,” Daniel assessed in 1994. “All the things that really fucked shit up [after Mr. Hood]. Shit got crazy for a little while, tell you the truth.”Footnote 101 His sister Kinetta Powell-Dumile provided Dingilizwe's eulogy. Speaking to the talents that enabled the nineteen-year-old to co-create these fantastic transformative collages, she gravitated to perceptual qualities that once might have seen Dingilizwe labelled a conjuror: “Subroc . . . thought what others couldn't perceive to think. He knew what others couldn't begin to know. He understood what others couldn't begin to understand. He did what others wouldn't try to do. … And now he still stays one step ahead of us.”Footnote 102

The conjuror like the alchemist pointedly defies the accepted order of things. Like High John the Conqueror described as “making a way out of no way” and “hitting a straight lick with a crooked stick,”Footnote 103 the conjuror is seen to perform the impossible; to operate beyond the constraints of Western scientific rationality. Thus, to invoke the magical in artistic contexts is a way to speak about what contemporary thinkers like Fred Moten and Tina M. Campt term fugitivity.Footnote 104 It is to make sense of art that creates a line of flight, via a combination of imaginative brilliance and the “supernatural skill” Albert Murray suggests has always framed Black culture heroes,Footnote 105 from everyday racist structures into an alternative future. In this much, the conjuror, like Ishmael Reed's neo-hoodoo artist, works “Juju upon [the] oppressors” and frees “fellow victims from the psychic attack launched by demons of the outer and inner world.”Footnote 106 To liberate one's imagination, one might deduce, is to circumvent the veil.

As early as 1933, Zora Neale Hurston noted Black American culture's impetus to creative reinvention as evidence of this will to human sovereignty.Footnote 107 It is to this history born of adversity in slavery and Jim Crow, and rendered continuingly meaningful in the post–Civil Rights era, that hip hop godfather Kool Herc explicitly attributes the musical recycling he introduced in 1973, which ultimately yielded the sophisticated transformative sample-based poetics discussed in this article:

Just like back in the days when the masters throw away the chicken back, and also the pig feet, you pick it up and make something out of it, that's what I did with the record. They wanted to throw it away, I thought, pick it up, turn it into somethin’, and now everybody gotta put a drum beat in their record.Footnote 108

As I have argued, golden age rap's sophisticated transformations of sonic material belong in a rich historic lineage of fugitive Black American practices. Smith's concept of conjuring culture provides a particularly apt metaphor through which to reinscribe this history. But, just as pertinently, it offers a multi-layered, multi-directional, and usefully phenomenological way of conceptualizing the golden age rap album's rich ways of making meaning, with its emphasis on virtuosic rereading, on the awakening of new potential through bricolage, on the magic of transformation, and the routes this offers toward transcendence. Perhaps, to this end, Mr. Hood's most profound therapy is not in the astringent laughter its satire of racist and limiting depictions of Blackness can provoke, but, rather, in the imaginative virtuosity it employs to contradict them. Caught in the brilliance of the album's most audacious of tricks, the creation of Mr. Hood himself, maybe Daniel Dumile would have recognized in his audience “the feeling to be about to smile.”

Appendix 1

Mr. Hood: track by track

1. “Mr. Hood at Piocalles Jewelry/Crackpot”

Skit/Song. Location: Jewellery shop. Mr. Hood meets Zev as Hood shops for gifts. Establishes Zev is down on his luck and Mr. Hood a drug dealer. Leads Zev to “Crackpot,” parable about misadventures of local drug dealer.

2. “Who Me? (With an Answer from Dr. Bert)”

Song. Intro: Hood admits he wants “something more.” Zev starts Afrocentric pride monologue. Interrupted by samples from children's story mocking him as an “impractical dreamer” and “small ragged negro boy.” Cartoon glissando. Bystander announces, “Uh oh, Z-L's Xercisin’ his right to get hostile!” Zev raps about disconnect at realizing he is subject of racist barb and goes through fallacies of “Sambo” stereotype. Outro: conversation with Bert from Sesame Street. Bert suggests Zev put a hex on Sambo by “[drawing] a circle round him.” Zev reminds him “you gotta rock that hum shit for me later,” setting up song 6.

3. “Boogie Man!”

Song. Onyx's solo rap. Appropriates racialized “boogie man” trope to describe his own prowess/comment on US culture's fear of Black males.

4. “Mr. Hood Meets Onyx”

Skit. Location: Zev's house. Mr. Hood arrives to meet the crew. Makes unreasonable demands (“I would like a bottle of wine”). Game of snaps breaks out between Hood and Onyx. Tempers fray when Hood tells him “Your mother likes to visit the old churches.” Before leaving, Hood arranges to come back for haircut from Subroc. Sets up tracks 5 and 12.

5. “Subroc's Mission”

Song. Subroc's solo rap. Commentary on daily activities as barber, producer, and student of Islam. Outro: he's interrupted by samples from vintage goofball comedy: a client trying to fast-talk him (“If you give me a haircut I promise not to pay you,” etc.).

6. “Humrush”

Song. Opens on samples of Sesame Street's Bert and Ernie practising “the exciting art of humming.” They are part of KMD's crew: hum becomes basis for sparse hip hop beat with prominent sub-bass kick/one-finger piano bassline. KMD address their integrity, belief in unity, evasion of stereotypes, etc. with affirmations from Bert and Ernie.

7. “Figure of Speech”

Song. Freestyle track: coded allusions to Black American Islamic mysticism. Key outro: samples of Malcolm X speak directly to Zev. Confronts him with idea that as a Black man in America, he is viewed as “nothin’.” Sets up pivotal next song.

8. “Bananapeel Blues”

Song. Location: storefront congregation. Blues track w/ hollers, soul-claps, etc. Zev in preacher mode (homages Gil Scott-Heron's “H2Ogate Blues”). Scathing rebuke of white exceptionalism using Nuwaubian Nation's inversion of Curse of Ham. Outro: extended section with Scott-Heron repeating “Now tell me / How much more evidence does a citizen need?” Implied dialogue with Malcolm X in previous song.

9. “Nitty Gritty”

Song. KMD with Brand Nubian now unambiguous in promoting Black Islamic knowledge for upliftment. Closes on missionary statement (implicitly to Hood) to “raise up the dead.” Outro: dialog between sung elements of Shirley Ellis's “Nitty Gritty” and Q-Tip from A Tribe Called Quest rapping “It's the nitty gritty.” Cuts to Tip: “more like trial and error/it's the trial and error / more like trial and error.” Introduces next song.

10. “Trial ’n’ Error”

Song. Intro: dialogue between children's story records and Sesame Street's Big Bird addresses life-learning and reinvention: “Well, I bet if you really tried” / “I could never do that” / “Well, I bet if you really tried” / “Aw, I made a mistake,” etc.

11. “Hard Wit No Hoe”

Song. Folkloric allegory about interracial relationships coded in tale about farmers neglecting tools.

12. “Mr. Hood Gets a Haircut”

Skit. Location: Subroc's room. Mr. Hood arrives for his haircut. Hood asks to hear “folklore records.” Subroc plays next song.

13. “808 Man”

Song. Intro: Boys on street discussing rap songs: “I bet you wonder where [KMD] got the bass from?” Zev raps Brer Rabbit style tale about nightclub adventure gone awry. Uses “teachings of Mr. Hood” to outwit “giant” [i.e. street thug] and capture his boom.

14. “Boy Who Cried Wolf”

Song. Zev believes he has given Hood pause for thought: “I see you're rootin’ for the words that I'm doodlin’, I'm just a pusher of this thing called knowin’. . . start to build and you're growin’. . . It's up to you to decide, from the fruit that history [his tree] provides.”

15. “Peachfuzz”

Song. KMD on street attempting to woo girls: musings on youth, racialized struggles to get by, the role of status symbols in perceived attractiveness, the muddling of manhood with pimp image/other socially destructive behaviors. (“Hear this clear, I'm a man I tell ya / No dreams or drugs like the slugs will I ever sell ya”).

16. “Preacher Porkchop”

Skit/Song. Hood's ironic redemption in Preacher Porkchop's congregation (“They also said that a preacher could not pimp strut! . . . But I said wrong!,” etc.). As Porkchop initiates a beat-switch from the pulpit (i.e., a switching of path), Hood can be heard to start testifying “Yes. Yes. I understand.”

17. “Soulflexin’”

Revue-style outro song. Each MC flexes their skills resolving to themes about how they're “Soulflexin’.” Outro: shout outs as if credits rolling (“And my man Geeby be soulflexin’ / And the engineer Gamz be soulflexin’,” etc.).