INTRODUCTION

Researchers have argued that entitlement perceptions among employees are increasing (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017) and consequently, this has evoked a growing interest in this phenomenon from academia and from managers (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009; Fisk, Reference Fisk2010; Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010; Brouer, Wallace, & Harvey, Reference Brouer, Wallace and Harvey2011; Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017). In line with Westerlaken, Jordan, and Ramsay (Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017), we define employee entitlement as an excessive self-regard of one’s abilities at work linked to a belief in the right to privileged treatment without consideration of all the factors involved in determining rewards and remuneration in that context. Human Resources practitioners have identified excessive entitlement of employees as a pervasive and pernicious ongoing social issue (Fisk, Reference Fisk2010) and one that needs to be addressed and understood, particularly in a work environment (Hurst & Good, Reference Hurst and Good2009; Byrne, Miller, & Pitts, Reference Byrne, Miller and Pitts2010). Specifically, many are of the view that excessive entitlement perceptions can undermine the link between effort and performance. If an entitled employee believes their entitlement to be justified without a consideration of their actual performance and achievements, then managing such employees using standard performance management techniques typically employed in business, such as linking rewards to performance, becomes problematic (Kuvaas, Reference Kuvaas2006; Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers, & De Lange, Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and De Lange2010; Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden, & Hu, Reference Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden and Hu2014). In a team environment, heightened individual entitlement may create conflict between the highly entitled individual’s expectations and the group expectations, which may distract the individual and the team in terms of their overall performance and result in them focusing on equity issues instead. While the negative outcomes of excessive entitlement have been well documented (see Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017 for a review), a recent argument has emerged that entitlement may also be linked to positive behaviors at work (Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017). Based on this notion, our study seeks to explore the relationship between entitlement perceptions and potential positive outcomes including affective commitment and citizenship behaviors. Doing so, we answer the call by contemporary authors (Fisk, Reference Fisk2010; Harvey & Dasborough, Reference Harvey and Dasborough2015; Miller & Gallagher, Reference Miller and Gallagher2016; Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017; Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017) encouraging researchers to expand our understanding of employees’ entitlement perceptions, thereby contributing to the growing body of research on this phenomenon.

Entitlement

Despite recent interest in employee entitlement as an individual trait, forms of psychological entitlement have been evident for decades. As Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline, and Bushman (Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004) explain, the 1970s were known as the ‘Me Decade,’ the 1980s as the ‘Greed Decade,’ and the 1990s as the ‘New Gilded Age.’ The name of each of these decades suggests that aspects of entitlement have existed in society for some time. In contemporary research, we find an increase in research on entitlement among employees born between 1980 and 2000, often referred to as ‘Gen Y’ (Laird, Harvey, & Lancaster, Reference Laird, Harvey and Lancaster2015). Recently, researchers have argued that entitlement perceptions are rising at work with some individuals expecting praise and reward, without offering the equivalent performance (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009). Although, there is both anecdotal (Holderness, Olsen, & Thornock, Reference Holderness, Olsen and Thornock2016) and empirical evidence (Trzesniewski, Donnellan, & Robins, Reference Trzesniewski, Donnellan and Robins2008) supporting this broad view of increasing entitlement by employees, more detailed research is required to understand this phenomenon. Moreover, it is important to understand that although entitlement is not a new construct, the increasing prevalence at work of entitlement perceptions may have significant consequences for managing individuals.

Definitions of entitlement

Entitlement has been defined differently across a variety of disciplines. In sociology, it has been broadly linked to social justice and examined in relation to equity, deservingness, privileges, fairness, and the procedures, distribution and retributive actions of people (Lerner, Reference Lerner1987). Psychopathological interpretations of entitlement have focused on narcissistic personality disorder and consequentially measured entitlement as a subscale of narcissism (Raskin & Terry, Reference Raskin and Terry1988). Within this discipline, entitlement is one of the factors that support the formal diagnosis of clinical and subclinical narcissism (DSM-5 American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Grubbs and Exline (Reference Grubbs and Exline2016) argue that there is a pathological aspect to entitlement. Rejecting this view, Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004) has argued for measurement of entitlement as a nonpathological, stand-alone trait outside the enveloping definition of narcissism. Despite continuing support for this research, some researchers have expressed concerns over the conceptualization of entitlement as a stable personality trait and encourage the measurement this construct in a more reliable, valid manner reflecting the context in which it occurs, for instance as work entitlement (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017).

Moving to examine entitlement in a work context, Harvey and Martinko define employee entitlement as a ‘desire for preferred treatment and rewards without regard to performance levels’ (Reference Harvey and Martinko2009: 461). Drawing on Kerr (Reference Kerr1985), Fisk (Reference Fisk2010) argued that excessive entitlement reflects unfounded beliefs around an individual’s legitimate right to special privileges, better treatment, and more status when they have not earned these rights. Drawing on these broad definitions and in line with Westerlaken, Jordan, and Ramsay (Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017), we define employee entitlement as an excessive self-regard linked to a belief in the right to privileged treatment at work without consideration of all the factors involved in determining rewards and remuneration in that context. We have adapted Westerlaken’s original definition by removing the notion of an automatic right, as we acknowledge that entitled employees can remain entitled, but at the same time may increase (or maintain) their effort to ensure their rewards maintained.

Research on entitlement at work

Entitlement perceptions have been strongly linked to self-serving attribution biases (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009). This bias emerges from an attitude that explains positive outcomes as a result of own attributes, and negative outcomes as a result of external, uncontrollable variables (Miller & Ross, Reference Miller and Ross1975). Harvey and Martinko (Reference Harvey and Martinko2009) also found low levels of cognitive elaboration among highly entitled employees, which explains the ability to maintain inflated self-perceptions, even in the face of objective evidence to contradict this perception (e.g., during performance appraisal). In other research, entitled employees were found to engage more frequently in political behaviors (e.g., undermining and self-promotion; Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010) and have a heightened sense of abuse from supervisors leading to deviant behaviors and self-justified retributive acts such as taking time off work without approval (Harvey, Harris, Gillis, & Martinko, Reference Harvey, Harris, Gillis and Martinko2014). Research suggests that entitled employees are more active in coworker abuse (Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010) and are more frequently in conflict with supervisors leading to decreasing job satisfaction among colleagues (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009).

Miller and Gallagher (Reference Miller and Gallagher2016) conducted a study finding that higher levels of entitlement predicted lower job satisfaction, and that unless rewarded disproportionate to their work effort, entitled employees tend to be dissatisfied and ‘less-than-helpful’ within their organization. Harvey and Dasborough (Reference Harvey and Dasborough2015) highlight that research has found that entitlement among coworkers has primarily undesirable, workplace outcomes like heightened job frustration (Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010), which in turn can lead to coworker abuse and undesirable political behavior. Research also has uncovered a significant negative relationship between employee entitlement and reciprocity, violating established rules of social exchange theory (Blau, Reference Blau1964) and the psychological contract (Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017), which results in negative behaviors and attitudes espoused in the workplace (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004; Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009).

On the other hand, however, entitlement researchers have found that highly entitled employees have a strongly optimistic view of the world and themselves, and have an expectation those life events will go their way (Paul, Niehoff, & Turnley, Reference Paul, Niehoff and Turnley2000). This positive view may contribute to explaining the higher prevalence of interpersonal conflict with their supervisors (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009) as entitled employees shun challenging criticism of their views. It may also explain why they tend to respond with destructive replies to the feedback that does not confirm the view they have of themselves (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline and Bushman2004).

In contrast, Brummel and Parker (Reference Brummel and Parker2015) found a positive relationship between entitlement and organizational citizenship behavior individual (OCBI) and as such, they argue that entitlement may not suppress individuals’ perceived helping behavior in the workplace. Our review of the literature suggests that the potential for entitlement to have a positive influence on work-based outcomes has not been examined in any detail, beyond the Brummel and Parker (Reference Brummel and Parker2015) study.

Despite the focus on negative workplace behaviors, we contend that the optimistic nature of some entitled employees may have a positive contribution to the workplace. It may be that entitled employees may also have higher engagement with their workplaces as their higher self-regard fuels their views of their centrality and criticality to the organization. In the next section, we outline our theoretical model and develop hypotheses to test these ideas.

HYPOTHESES

In developing our model, we draw on Self-Consistency Theory (Korman, Reference Korman1970). Korman (Reference Korman1970) argues that individuals are motivated to behave consistent with their perceived self-image, and as such, they will engage in activities that enforce this self-image. Examining this theory in relation to entitlement, we argue that when considering their entitlement perceptions, individuals create a specific view of their self-image and their value to the organization which is then reflected in their sense of entitlement. We note that self-image is a broader concept and contains more factors than self-esteem. Self-image is established by individuals through their own actions (Bem, Reference Bem1967, Reference Bem1972), and as Bem proposes ‘Individuals come to “know” their own attitudes, emotions, and other internal states partially by inferring them from observations of their own overt behavior and/or the circumstances in which this behavior occurs’ (Reference Bem1972: 2). One’s self-image incorporates a person’s self-esteem and the degree to which the individual focuses on themselves as being important and may contain aspects of attitudes such as their expectation of rewards. Heightened self-image may result in individuals seeing themselves as being important to the organization, which may, in turn, lead to high expectations of the rewards that should accrue to them as result of their membership of the organization – regardless of their actual performance in that organization.

In general, Jordan, Ramsay, and Westerlaken (Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017) note that the extant research has viewed high entitlement as problematic, with links to negative work behaviors, particularly if those entitlement expectations are not met by the organization. However, they also note that organizations also often have employees who may have high entitlement, but are also able to achieve high performance. The question then becomes whether there are positive outcomes that can emerge from such highly entitled employees and raises the issue of whether a sense of entitlement can also contribute toward positive behaviors at work?

Although there are a range of positive workplace outcomes that we could examine, we have specifically decided to focus on affective commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) as two factors that allow an individual to have a positive impact on a workplace. Although some studies have examined the link between entitlement and citizenship behavior (see Hochwarter, Meurs, Perrewé, Todd Royle, & Matherly, Reference Hochwarter, Meurs, Perrewé, Todd Royle and Matherly2007; Brummel & Parker, Reference Brummel and Parker2015), a literature search found no studies that examine the links between entitlement perceptions among employees and affective commitment to the organization. Research on affective commitment suggests that employees who are scoring high on their affective commitment to the organization also have higher organizational performance (Ostroff, Reference Ostroff1992). Affective commitment also implies emotional attachment toward the organization from the employee. As affective commitment and citizenship behavior are important for organizational prospering and thriving (Katz & Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1978; Grant & Ashford, Reference Grant and Ashford2008), examining the relationship to entitlement provides an interesting avenue for investigation.

Additionally, we are interested if there are factors that moderate this relationship. Previous findings suggest that entitlement is enacted using negative political behavior (Harvey & Harris, Reference Harvey and Harris2010). Research conducted on self-monitoring (SM) individuals, however, has found that SM (which involves personal behavior designed to promote one’s position in a social group) alleviates the adverse effects of political perception, among employees that are involved in OCBs (Blakely, Andrews, & Fuller, Reference Blakely, Andrews and Fuller2003). Also, research has indicated that high SM behavior resulted in conscientious and courteous attitude toward other members of the organization (Shaffer, Li, & Bagger, Reference Shaffer, Li and Bagger2015). Drawing on critiques by Jordan, Ramsay, and Westerlaken (Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017) challenging a sole focus on the negative outcomes of entitlement, we see the benefits of moving this research to examine positive outcomes and on that basis, we are also interested in assessing the potential moderating role of personality (such as SM) in these relationships.

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCB)

OCB refers to employee behavior that goes beyond the formal employee–employer contract, which promotes organizational effectiveness, and that is not explicitly recognized by the formal reward system (Organ, Reference Organ1988). OCB as a construct, therefore, captures extra effort and dedication toward the organization by the employee and seeks to explain actions that are not performed based on motivation to obtain immediate rewards or avoid punishment (Shore & Wayne, Reference Shore and Wayne1993). Citizenship behaviors are believed to produce tangible benefits for the organization (Wei, Reference Wei2012). Podsakoff, Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Maynes, and Spoelma (Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2014) conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the positive outcomes of OCB further and found that product quality, customer service, profitability, organizational performance, and overall effectiveness and success of the organization had a significant relationship to OCB. Furthermore, Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff, and Blume (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2009) found positive results in regards to employee performance and reward decisions, and a negative relationship with absenteeism, intention to leave and actual turnover.

Theoretically, Williams and Anderson (Reference Williams and Anderson1991) separate OCB into two parts, individual-focused behaviors and organization-focused behaviors. OCBI consists of altruism, cheerleading, peacekeeping, and courtesy efforts aimed at helping other individuals in the organization. Organizational-focused citizenship behavior organizational (OCBO) includes factors such as conscientiousness, sportsmanship, and civic virtue directed toward the benefit of the organization (Williams & Anderson, Reference Williams and Anderson1991).

Entitlement and OCB

In relation to entitlement, there have been empirical findings that examine the relationship between entitlement and OCBs. For instance, Brummel and Parker (Reference Brummel and Parker2015) found a nonsignificant relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs directed toward the organization, and a significant positive relationship between psychological entitlement and OCBs directed toward individuals. As noted earlier, this study focused on deservingness as a construct and used a broad social measure of deservingness (sample item ‘I deserve to be happy’) to measure entitlement. In contrast, Priesemuth and Taylor (Reference Priesemuth and Taylor2016) found that the relationship between psychological entitlement (using a general entitlement scale) and OCBs was nonsignificant. These mixed findings suggest that further research is required to understand the relationship between work entitlement and positive work outcomes.

Acknowledging these findings, we argue, that entitled individuals may seek to make a contribution to the organization by enacting OCBs to maintain their entitlement perceptions. In line with our theoretical framework of Self-Consistency Theory (Korman, Reference Korman1970), we note that entitled individuals may develop a self-image that supports the view that they are critical and central actors in an organization. We also note that actions on behalf of the organization (such as poor performance management practices where all employees are not given objective, constructive, and accurate feedback on their performance) may provide the employee with information that may enhance their view of their criticality and centrality in the organization. Therefore, we argue that entitled employees can justify their entitlement perceptions and the fact that they deserve more rewards than others by perceiving themselves as making a greater contribution to the organization as a whole to achieve organizational success (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009). As noted by others, for the entitled individual, considering themselves to be in a position to be able to benefit the organization as a whole can arguably be seen as a reward or a privilege of only a handful of people in the organization has a right to (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017), separating them from the others in the organization, but linking organizational success with their own success and commensurate rewards. On this basis, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1a : Employee entitlement will be positively related to OCBO.

Entitled employees have been described as being more prone to being in conflict with their supervisors as a result of them ‘stepping above their rank’ (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey and Martinko2009). The motivation for such actions may come from an inflated self-image and their perceived importance to the organization. Potentially, an entitled employee may find what they lack in formal recognitions (e.g., title or role), can be experienced through social interactions with their colleagues when sharing their knowledge with the colleagues that they perceive to be less important or knowledgeable than themselves. Although from an equity perspective, it could be argued that entitled employees may already consider themselves to be doing more than their colleagues, the employee’s self-image and views on what they have to do to maintain their entitlement perceptions may result in them helping others. It could be argued that the belief that entitled employees have about their contribution compared to others may result in them only helping others if it can help themselves as well. We argue based that an employee’s self-image and the entitlement expectations associated with that self-image will result in the entitled individual being willing to engage in helping behaviors toward others, particularly if this helps to maintain their value to the organization and their entitlement perceptions. Therefore

Hypothesis 1b : Employee entitlement will be positively related to OCBI.

Affective organizational commitment

Organizational commitment has been conceptualized and measured in a wide range of different studies and is one of the most frequently studied organizational variables (Kell & Motowidlo, Reference Kell and Motowidlo2012). Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991) note three components that measure organizational commitment: normative commitment, which reflects commitment, based on perceived obligation toward the organization, for example, the norms of reciprocity; continuance commitment, which reflects the perceived costs, both economic and social, of leaving the organization; and finally, affective commitment which reflects the employees’ positive emotional attachment to the organization (Meyer, Allen, & Smith, Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993). Research suggests that of these three components, affectively committed employees identify strongly with the organizational goals, and consequently strive to ensure the success of the organization to which they are committed (Ha & Ha, Reference Ha and Ha2015).

Affective commitment is the aspect of the three-component model that is expected to have the strongest positive relation to positive work outcomes (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002) and therefore this is the focus of our study. A body of research that has found that more satisfied employees usually experience greater affective commitment (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham1990; Mathieu & Farr, Reference Mathieu and Farr1991; Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1997) and that more committed employees are less likely to leave voluntarily (e.g., Mowday, Porter, & Steers, Reference Mowday, Porter and Steers1982; Allen & Meyer, Reference Allen and Meyer1990; Palich, Horn, & Griffeth, Reference Palich, Horn and Griffeth1995). There is also evidence that satisfied, committed employees contribute to better organizational performance (Ostroff, Reference Ostroff1992).

Entitlement and affective commitment

In terms of previous research examining the link between affective organizational commitment and entitlement perceptions, Cihangiroğlu (Reference Cihangiroğlu2012) conducted a study to investigate potential correlations between a general personality measure of narcissism (which included an entitlement subscale) and organizational commitment. This research found there was found no significant relationship between entitlement perceptions and affective organizational commitment. We argue, however, that entitlement perceptions (particularly if these entitlement perceptions are met) may increase an employee’s sense of connection to the organization resulting in increased affective commitment. Affective commitment among employees is positively related to perceived organizational support (Rhoades, Eisenberger, & Armeli, Reference Rauthmann2001). Drawing on the Self-Consistency Theory (Korman, Reference Korman1970), this leads us to believe that employees who have a heightened ‘sense of self’ may be more likely to establish affective commitment to any organization for whom they work as they value an organization that they perceive to value them. Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002) found evidence of a link between increased job involvement and affective commitment and, therefore, if entitled employees see themselves as essential employees, then we argue that this supports the plausibility of entitled employees being positively affectively committed to that organization. Furthermore, Self-Consistency Theory primarily finds self-conceptions critical for survival because they enable individuals to predict and control the nature of their social reality (Swann, Griffin, Predmore, & Gaines, Reference Swann, Griffin, Predmore and Gaines1987), and this arguably shares similarities to what affective committed employees experience in their desire to identify with the organization (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). We then argue that self-focused and excessively self-regarding entitled employees will find it desirable to have their self-perception aligned with the interests of the organization, and as such, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2: Employee entitlement will be positively related to an employee’s affective commitment.

Self Monitoring (SM)

SM is a social psychological construct that investigates expressive behavior and self-presentation and self-control guided by situational cues to achieve social appropriateness (Snyder, Reference Snyder1974). Snyder described two types of people who monitor their behavior, high self-monitors and low self-monitors. In more recent research, this continuum has been challenged with research suggesting multifaceted components underlying the construct (Lennox & Wolfe, Reference Lennox and Wolfe1984; Hallahan & Lloyd, Reference Hallahan and Lloyd1987; Briggs & Cheek, Reference Briggs and Cheek1988; Lennox, Reference Lennox1988). A revision of the theoretical foundations for SM was offered by Lennox and Wolfe (Reference Lennox and Wolfe1984). They investigated the construct further and argued that four out of five of the original components correlate with social anxiety. On this basis, they promoted a narrower and more specific definition of SM stating that it emerged in two forms: protective SM (modifying one’s behavior to get along with others); and, acquisitive SM (modifying one’s behavior to get ahead in a social group) (Lennox, Reference Lennox1988). Research suggests that the acquisitive and protective dimensions are independent and have divergent networks of relations to other psychological and external variables, and as such ought to be conceptualized and assessed separately (John, Cheek, & Klohnen, Reference John, Cheek and Klohnen1996).

Following recommendations by Jenkins (Reference Jenkins1993) and Mobley, Griffeth, Hand, and Meglino (Reference Mobley, Griffeth, Hand and Meglino1979), we use SM as a moderator, as it is a personality trait and suitable to analyze the relationship between variables further. In our study, we choose to focus on the acquisitive aspect of SM exclusively (Lennox & Wolfe, Reference Lennox and Wolfe1984), as it has more appropriate theoretical alignment with research suggesting entitled individuals want to promote themselves and see themselves as leaders (Harvey & Dasborough, Reference Harvey and Dasborough2015). Arkin (Reference Arkin1981) interpreted the protective SM domain as a fear of social rejection, while acquisitive SM was motivated by the hope of gaining social rewards or success which would fit with the entitled employee’s expectations of rewards and preferential treatment.

Research has investigated SM as a moderator between self-rated traits and OCBs and has found this to be an appropriate construct for this purpose (Shaffer, Li, & Bagger, Reference Shaffer, Li and Bagger2015). Findings suggest that high self-monitors are concerned about the situational appropriateness of their behaviors and that high SM behavior resulted in conscientious and courteous attitude toward other members of the organization (Niehoff & Moorman, Reference Niehoff and Moorman1993). Moreover, Chang, Rosen, Siemieniec, and Johnson (Reference Chang, Leach and Anderman2012) found that high SM reduced the negative effects of being involved in office politics when considering the OCB of highly conscientious employees. In line with our theoretical framework of the Self-Consistency Theory (Korman, Reference Korman1970), we note that SM may be a skill that can be used to enhance one’s personal agendas. Assuming that entitled employees are investing efforts to espouse their inflated self-perceptions in their work environment, we propose SM as a moderator between entitlement perceptions among employees and their subsequent behavior. On this basis, we argue that:

Hypothesis 3a : The relationship between employee entitlement and OCB is moderated by SM perceptions such that the relationship will be stronger for employees high in SM.

As argued in relation to affective organizational commitment, there is little empirical evidence on investigations between entitlement and affective commitment. Examining the relationship between SM and affective commitment, however, Jenkins (Reference Jenkins1993) found that employees who scored higher on affective commitment and lower SM values were more likely to remain employed by that organization. Furthermore, Özalp Türetgen, Unsal, and Dural (Reference Özalp Türetgen, Unsal and Dural2017) found evidence of a significant relationship between managers SM and their subordinates affective commitment. SM is also related to individuals’ self-rated, work-related outcomes, such as their job involvement and organizational commitment (e.g., Day, Shleicher, Unckless, & Hiller, Reference Day, Shleicher, Unckless and Hiller2002; Day & Schleicher, Reference Day and Schleicher2006). Rauthmann argued that entitled individuals require ‘basic skills in perceptual sensitivity and behavioral plasticity (i.e., self-monitoring) to smoothly navigate through interpersonal situations and effectively manipulate others’ (Reference Rhoades, Eisenberger and Armeli2011: 507). We, therefore, argue that to promote themselves in organizations, entitled employees may acquisitively self-monitor their behavior to promote their affective commitment (and therefore their criticality) to their organization. Our hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3b: The relationship between employee entitlement and affective commitment is moderated by SM perceptions such that the relationship will be stronger for employees high in SM.

METHOD

Participants

We conducted a purposive sampling process with snowballing, targeting individuals above the age of 18 years, who were currently employed or had previous work experience. To achieve a diverse sample, we gathered participants through bulletin boards, online fora, and various social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn) recruiting those of working age with work experience. Of 555 surveys distributed, we received 167 responses (a response rate of 30.04%) with the respondents being Norwegian (38.9%), Australian (25.1%), American (7.2%), British (6.0%), and others (22.8%). The participants comprised 84 males and 83 females, ranging from the age of 18–65 years, the mean age was 29.5 (SD 9.2) years. Respondents reported between 0.5 and 10 years work experience, and the mean work experience being 8.73 (SD 8.3) years.

Procedure

Data were collected using a single administration online survey, and to encourage participation we used monetary incentives to recruit participants (Simmons & Wilmot, Reference Simmons and Wilmot2004). Two randomly selected participants were selected to receive an online Amazon gift-card to the value of $50AUD at the end of the study. The study was approved by a University Human Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained through completing the survey. To address the issue of Common Method Bias, we varied the scales when administering the survey by using scales of varying lengths and using different anchors for the scales (Spector, Reference Spector2006). Based on our results (discussed later), we consider that the impact of method consistency was minimal as we have a mix of significant and nonsignificant results.

MEASURES

Independent variable

Entitlement

Perceived employee entitlement was assessed using the validated 18 item Measure of Employee Entitlement scale (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017). This scale focuses on the inflated self-perceptions of worth to the organization and the expectation that the individual receives preferential treatment or more resources than others, specifically in relation to work. The Measure of Employee Entitlement has three subscales. Reward as a right represents the expectation that compensation, reward, and recognition are given as a reflection of the entitled individuals perceived worth without regard to their actual performance or achievements (eight items, e.g., ‘I expect regular pay increases regardless of how the organization performs’ and ‘I expect a bonus every year’). Self-focus represents the direct conscious attention that the employee directs at themselves and the desire for preferential treatment (five items, e.g., ‘Employers should accommodate my personal circumstances’ and ‘I deserve preferential treatment at work’). Excessive self-regard represents the heightened the sense of value that the employee believes that they bring to the organization (four items, e.g., ‘I only want to work in positions that are critical to the success of the organization’ and ‘I want to only work in roles that significantly influence the rest of the organization’) (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017). The measure uses a 6-point Likert-scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree.’

Moderating variable

SM

The Acquisitive Self-Monitoring Scale (Lennox & Wolfe, Reference Lennox and Wolfe1984) contains 13 items that measures two components: ability to modify self-presentation (seven items, e.g., ‘In social situations, I have the ability to alter behavior if I feel that something else is called for’) and sensitivity to expressive behavior in others (six items, e.g., ‘My powers of intuition are quite good when it comes to understanding others’ emotions and motives’). We specifically focused on acquisitive SM as it assesses the way in which individuals approach each social encounter with the aim to gain interpersonal rewards (Arkin, Reference Arkin1981; Lennox, Reference Lennox1988). Lennox (Reference Lennox1988) refers to levels of self-esteem among acquisitive self-presenters and their optimistic mindset on acquiring social gains based on their self-presentation. The measure uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Yes, strongly agree’ to ‘No, I strongly disagree.’ This measure has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of SM in previous research (Lennox & Wolfe, Reference Lennox and Wolfe1984; Bearden, Netemeyer, & Teel, Reference Bearden, Netemeyer and Teel1989).

Dependent variables

OCB

OCB was measured with 16 items developed by Lee and Allen (Reference Lee and Allen2002). The scale measures two aspects of citizenship behavior. The first factor is defined as OCBI (eight items, e.g., ‘Give up time to help others who have work or nonwork problems’). The second factor is defined as OCBO (eight items, e.g., ‘Demonstrate concern about the image of the organization.’). The measure uses a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to always. This measure has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of OCB in similar research (Lee & Allen, Reference Lee and Allen2002; Piccolo & Colquitt, Reference Piccolo and Colquitt2006).

Affective organizational commitment

Affective commitment was measured using six items developed by Meyer, Allen, and Smith (Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993). A sample item of this scale is ‘I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own.’ The measure uses a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘No, I strongly disagree’ to ‘Yes, I strongly agree.’ This measure has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of affective organizational commitment in similar research projects (Meyer, Allen, & Smith, Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993; Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1997; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002).

Control variables

Previous research has shown that demographic variables such as gender and age (Zenger & Lawrence, Reference Zenger and Lawrence1989) and work experience (Laird, Harvey, & Lancaster, Reference Laird, Harvey and Lancaster2015) influences people’s attitudes toward colleagues, and thus, might impact on their entitlement perceptions and how this relates to their organizational behaviors. Control variables collected included gender (1=male, 2=female), age and the work experience of participants.

RESULTS

Prior to analyzing our data, we ran Harman’s 1-factor test to assess if our data were influenced by Common Method Bias. The results of this were that a single factor only accounted for 27.54% of the variance which minimizes our concerns over our results being significantly affected by Common Method Bias. We also note that our correlation matrix (Table 1) reveals a mix of significant and nonsignificant relationships, which again suggest that our results are not severely affected by Common Method Bias. Table 1 outlines the mean, standard deviation, α reliability, and correlations of the different variables. All measures were found to be reliable. Examining the main direct relationships for the variables, total entitlement was not significantly correlated with OCB (r=−0.03, ns) and was not related to affective commitment (r=0.13, ns). Table 1, however, shows that the employee entitlement dimension of excessive self-regard is significantly positively related to OCBO (r=0.24, p<.01) and OCBI (r=0.20, p<.05) and that reward as a right (r=0.17, p<.05) and self-focus (r=0.15, p<.05) were related to affective commitment. These results provide partial support for Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 2.

Table 1. Mean, SD, bivariate correlations and reliability of study variables

Note. OCB=organizational citizenship behavior.

Cronbach α reliabilities on the diagonal; n=167.

Significance at *p<.05; **p<.01.The bolded values are the totals for each variable (unbolded sub totals).

As expected, the control variables age (r=0.23, p<.01) and work experience (r=0.21, p<.01) were significantly linked to affective organizational commitment, while excessive self-regard (r=−0.15, p<.05) had a negative relationship with work experience. Regarding the moderating variable, we found SM to be positively significantly related to employee entitlement total (r=0.18, p<.05), OCB total (r=0.30, p<.01), OCBI (r=0.31, p<.01), and OCBO (r=0.23, p<.01). The subscale of SM, the ability to modify self-presentation had a negative significant relationship with affective organizational commitment (r=−0.20, p<.01).

Hierarchical regression analysis

To further examine the effect of the moderating variable, we used moderated hierarchical regression analysis (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986) to test the relationship between the independent variables, the moderating variables, and the dependent variables. This analysis was conducted in three steps, using work experience as a control variable in the initial step, after that, adding the independent and the moderating variable separately to the model and in the last step adding the interaction of these two variables. The independent variable and moderating variables were mean-centered prior to entry in Step 2 to avoid multicollinearity (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991), and prior to entry in Step 3 the interaction term between the IVs was computed.

OCBO

We found two models (presented in Tables 2 and 3) that yielded significant results with OCBO as a dependent variable. Table 2 shows a variance of 12% for excessive self-regard being moderated by SM in predicting OCBO, and the interaction effect between them was found to be significant (β=0.15, p<.05). This finding suggests that entitled employees with higher self-regard use their acquisitive SM when engaging in OCBO. Examining SM in greater detail, Table 3 shows a variance of 11% for excessive self-regard being moderated by sensitivity to expressive behavior in others in predicting OCBO. The interaction effect between these variables was found to be significant (β=0.15, p<.05). This result suggests that when enacting OCBO in the organization that entitled individuals with high self-regard specifically focus on the reactions of those around them.

Table 2. Excessive self-regard and self-monitoring on organizational citizenship behavior organizational (OCBO)

Note. n=167.

Significance at *p<.05; ***p<.001.

Table 3. Excessive self-regard and sensitivity to expressive behavior in others (STEBIO) on organizational citizenship behavior organizational (OCBO)

Note. n=167.

Significance at *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

The significant interaction of excessive self-regard and SM on OCB was followed-up with a simple slopes analysis (see Figure 1). The simple slopes analysis revealed that employees have an excessive self-regard that significantly predict OCBO when SM total was high (β=0.34, p=.001), but that OCBO was not significant when SM total was low (β=0.094, p=.344), providing partial support to Hypothesis 3a.

Figure 1 Interaction between excessive self-regard (ESR) and self-monitoring (SM) on organizational citizenship behavior organizational

The significant interaction of excessive self-regard on sensitivity to expressive behavior in others was followed-up with a simple slopes analysis (see Figure 2). This analysis revealed that employees have an excessive self-regard that significantly predict OCBO when sensitivity to expressive behavior in others was high (β=0.38, p=.001), but that OCBO was not significant when sensitivity to expressive behavior in others was low (β=0.13, p=.186). Similar to the previous regression analysis, this provides partial support to Hypothesis 3a. Furthermore, this analysis identifies the specific aspect of SM that moderates the relationship between excessive self-regard and OCBO.

Figure 2. Interaction between excessive self-regard (ESR) and sensitivity to expressive behavior in others (STEBIO) on organizational citizenship behavior organizational

Affective commitment

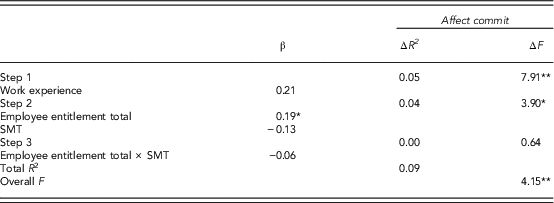

We found no significant interactions between employee entitlement, its subscales, and moderation between SM and its subscales, on affective commitment. In Table 4, we present the regression of employee entitlement total and SM total on affective commitment which was nonsignificant.

Table 4. Employee entitlement total and self-monitoring total (SMT) on affective commitment

Note. n=167.

Significance at *p<.05; **p<.01.

DISCUSSION

Our data provide some insights to help us to unpack the phenomenon of entitlement. The data also reveal a discrepancy between the results and our hypotheses, and as such, this requires explanation. We found no significant relationship between the overall construct of employee entitlement and the aggregated measure of OCB. Further investigations of the subscales of entitlement perceptions and the construct of OCB, as well as the subscales, however, reveal interesting findings. Excessive self-regard positively correlated with OCB, and furthermore, with both subscales of organizational OCB (partial support for Hypothesis 1a) and individual OCB (partial support for Hypothesis 1b). We predicted this based on previous research (Hochwarter et al., Reference Hochwarter, Meurs, Perrewé, Todd Royle and Matherly2007; Brummel & Parker, Reference Brummel and Parker2015), but note that our research differs as it uses a measure of employee workplace entitlement, rather than general measures of deservingness. The positive finding in relation to OCBI may support our notion that individuals who are highly entitled see themselves as important and central to the organization. Indeed, this view is supported by Settoon and Mossholder (Reference Settoon and Mossholder2002) who found that network centrality was linked to helping behaviors. Following our arguments, it seems that entitled employees may voluntarily participate in activities that are commonly associated with altruistic behavior to help others as a way of demonstrating their importance to the organization.

Another interesting finding (but not predicted) was that excessive self-regard was negatively linked to work experience. Thus, our results suggest that work experience matters in getting a realistic view of one’s abilities. In considering this finding we note the Dunning–Kruger effect (Kruger & Dunning, Reference Kruger and Dunning1999), which argues that people of low ability suffer from a cognitive bias by overestimating their own abilities in relation to the abilities of others around them. Work experience may provide employees with a range of experiences to test their abilities, and this may, in turn, lead to a more accurate assessment of their value to an organization which may drive their subsequent entitlement perceptions. This is supported by previous research which links work experience to self-assessed abilities during change (Gravill, Compeau, & Marcolin, Reference Gravill, Compeau and Marcolin2006).

To further investigate our findings, a moderated regression analysis of this relationship was conducted where SM was used as a moderator to examine the relationships between the variables. We argue that employees, who highly self-monitor their behavior, and more specifically, the expressive behavior among their colleagues, may adapt their own citizenship behavior accordingly. Recent research by Huang (Reference Huang2017), supports this assertion in relation to the operationalization of political skills (of which SM is a factor) and an employee’s promotability.

These findings in relation to SM have several implications. Our findings could lend support to a recent argument about entitlement being a latent activated trait (Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017). Our findings suggest that there is a relationship between individuals’ monitoring their colleague’s behavior and their own entitlement perceptions. If this is so, this entitlement could be situationally activated. This also means that managers may be able to effectively manage entitled employees by pointing out the reactions of others in the workplace to their behavior. Our research suggests that employees who have excessive perceptions of their abilities are still able to contribute to the organization. These individuals, if managed properly, can engage in both OCBI and OCBO.

Although previous research has found lower enactment of citizenship behaviors at work because of entitlement perceptions (Hochwarter et al., Reference Hochwarter, Meurs, Perrewé, Todd Royle and Matherly2007), our data suggest that there are specific aspects of entitlement that contribute to the higher enactment of citizenship behaviors. Entitlement perceptions among employees are an important aspect that managers need to facilitate and align with the organizational goals. Clearly there is a need for a more in-depth investigation into the relationship between entitlement and citizenship behavior (Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2013).

In regards to the relationship between affective commitment and employee entitlement, our findings initially suggest that there is no significant relationship between the overall construct of employee entitlement and affective commitment. Further examination of the subscales of entitlement, namely reward as a right and self-focus resulted in a weak correlation between these and affective commitment. The positive correlation between one’s expectations to be rewarded as a right and affective commitment can be explained. Positive emotions are generated based on the identification and similarities we have between our own emotions and the ones the organization holds (Chang, Leach, & Anderman, Reference Chang, Rosen, Siemieniec and Johnson2015). If entitled individuals were identifying themselves with the organization (I am proud to be a member of an organization that would have me as a member), there is a possibility that the employee sees this as reciprocated from the organization.

Another interesting positive correlation we found was between self-focus and affective commitment. Our results suggest that employees with excessive self-focus were also positively emotionally attached to the organization. Although self-focus inherently is associated with egocentric tendencies (Raskin & Terry, Reference Raskin and Terry1988), a more contextual explanation of this finding is that entitled employees could potentially consider themselves as central to any organization and their behavior emerges from this perception. On this basis, they invest emotional commitment, and in return there is an expectation of exclusive rewards, disregarding the relativeness of their own contribution to the contribution of their colleagues (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017).

Our data, in general, provide some support for the idea that entitlement perceptions can have a positive effect on organizational attitudes. Excessive self-regard as a personality trait (not to be confused with high self-esteem) is an opportunity for supervisors to achieve increased citizenship behavior and, thereby, a noncontractual positive contribution from entitled employees. There have been studies on psychological entitlement that have outlined that entitled employees are able to maintain their inflated self-perceptions due to their ability to find self-serving attributional biases as well as relatively low levels of cognitive elaboration (Harvey & Dasborough, Reference Harvey and Dasborough2015). Instead of attempting to change this perception and behavior among excessively self-regarding employees, a manager may assess the environment surrounding this employee and cautiously support these views if they lead to desired behaviors.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. The first limitation relates to the sampling frame used in this research; the second emerges from the research design as a single administration survey increasing the potential for common method bias inflating our results and the third relates to the adequacy of the measures used.

In terms of our sampling methodology, we were seeking a broad sample representative of the working population. The use of purposive sampling and limiting the recruitment process to web-based platforms, however, may have skewed our results (Evans & Mathur, Reference Evans and Mathur2005). Although there is an ongoing debate among scholars around the generalizability of a sample collected using web contacts (Wilson & Laskey, Reference Wilson and Laskey2003), we note that the respondents had significant work experience. To address this concern and confirm our findings, future research may need to collect data from consistent work environments (across a range of different organizations) to test our hypotheses.

A second limitation emerges from the use of a single administration surveying methodology increasing the potential for common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Maynes and Spoelma2003). To address this issue in our design phase, we applied several strategies to avoid or minimize any potential common method bias. Specifically, we used different length Likert scales with different anchors (Spector, Reference Spector2006) and randomized order of questions. It is notable that we tested our data using Harman’s 1-factor test and found that our results would not be explained by a common factor. We also note that our data yielded several nonsignificant results. By default, this may indicate a low probability of this bias occurring in this specific study. In future research, the use split-administration surveys with dependent and independent variables collected over time or the collection of objective data could be used to overcome this concern (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Maynes and Spoelma2003).

A third potential limitation of this study emerges from the use of a relatively new measure of work entitlement (Westerlaken, Jordan, & Ramsay, Reference Westerlaken, Jordan and Ramsay2017). The lack of significant results may be an indication that further development is required of the Measure of Employee Entitlement scale. Although we found the measure to be reliable, this is a new measure of entitlement and as such more research using the scale is encouraged to further validate the measure.

CONCLUSION

Harvey and Dasborough (Reference Harvey and Dasborough2015) defined entitlement research as a ‘low-hanging fruit’ with the potential to help to address the gap between academics and practitioners due to its practical implications. We hope our research helps increase both academic’s and manager’s understanding of entitlement by examining the impact entitlement has on positive organizational outcomes.

Theoretically, we have contributed to an expanded appreciation of employee entitlement by suggesting that entitlement is not always linked to negative outcomes. Indeed, researchers need to consider that entitled employees may indeed contribute to organizational outcomes. Our research also supports the increasingly common notion that employee entitlement perceptions are multifaceted and each of these dimensions tells us something about the entitled individual (Jordan, Ramsay, & Westerlaken, Reference Jordan, Ramsay and Westerlaken2017). Clearly, our results also indicate the importance of acknowledging the different factors that contribute to entitlement to better understand the impact on work-related variables.

From a practitioner’s perspective, we have demonstrated that it is important for managers to understand that employees who expect rewards as a right and who have higher levels of self-focus still can provide a positive contribution to the organization. Although not a core aspect of our research, our data suggest that some aspects of entitlement are linked to the length of experience at work. If, as we argue, entitlement perceptions are activated by specific cues, then supervisors who are aware of this may be able to manage these perceptions within their workplace. Indeed, assuming feedback is a part of the experience, with the proper feedback managers may be able to facilitate these entitlement perceptions for a better organizational outcome. Clearly, further research is warranted if we are to be able to understand the key implications of entitlement and attain a universal interpretation of its effect on the organizational environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the editor and the reviewers for their guidance and suggestions towards improving our manuscript.