Peru presents an adverse environment for the construction of ethnic parties and the political representation of indigenous peoples. Certainly, at the national level, no party represents the interests of indigenous peoples, whether ethnic or traditional, and no affirmative action exists, either in the form of quotas or seats reserved to ensure effective indigenous political representation. At the subnational level, however, the situation is more varied. Although there are no local ethnic parties (Madrid Reference Madrid2012; Paredes Reference Paredes, Meléndez and Vergara2010), the provinces show a significant variation in terms of descriptive and substantive representation of indigenous peoples. The objective of this article is to explain this territorial variation, a topic that has received scant attention in contemporary comparative literature.

After the fall of Alberto Fujimori’s authoritarian regime in 2000, Peru returned to democracy and soon enacted decentralization reforms. These democratic reforms unfolded amid indigenous demands that were increasingly gaining attention at the international level. In response, the Peruvian state introduced and gradually implemented an indigenous quota of 15 percent on electoral ballots at the subnational level. Scholars have noted that this quota is an inadequate instrument to achieve effective indigenous representation (Htun Reference Htun2004), given that its institutional design is weak, discourages the creation of ethnic parties, and ultimately fragments the indigenous movement (Espinosa de Rivero Reference de Rivero2012). In this context, local actors have nonetheless responded with varying degrees of success.

This article argues that in contexts of social conflicts and strong polarization, indigenous organizations build political unity, achieve greater cohesion and community support, and ultimately strengthen their overall political position and representation. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, generally speaking, indigenous peoples in Peru have experienced high levels of local conflict, due to the expansion of extractive industries in their territories (Bebbington et al. Reference Bebbington, Lingan and Scurrah2008; Arellano-Yanguas Reference Arellano-Yanguas2014). These socioterritorial conflicts have created opportunities for local expression, and in many cases, have even spurred the creation of platforms for local collective action (Paredes Reference Paredes2016).Footnote 1 The existence of cohesive organizations in combination with election ballots featuring indigenous leaders with political capital has resulted in substantive indigenous representation in the provinces. Thus, this article argues that political representation is explained by the combination of these two factors.

In theoretical terms, this article problematizes the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation, showing that these two dimensions are not necessarily linked to each other.Footnote 2 Although there are cases in which they are related, this article focuses particularly on counterintuitive cases in which these two dimensions are rather independent. In this sense, this study shows that high descriptive representation is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition to explain substantive representation. This finding concurs with the literature on gender quotas. Recent studies show that the low presence of women in office does not prevent their substantive representation; conversely, the latter is not guaranteed by a high descriptive representation of women (Güneş Ayata and Tütüncü Reference Ayata and Tütüncü2008).

This article proposes a descriptive typology that combines the descriptive and substantive political representation of indigenous peoples, not only to explain but also to contrast the differences among the respective types of cases. The subnational comparative method is used (Snyder Reference Snyder2001), which allows for keeping institutional variables constant. This article presents results from case studies from four provinces in Peru, two from the Andes and two from the Amazon. This helps control for sociocultural differences between indigenous peoples of both regions and account for variation of indigenous political representation within these regions, particularly in substantive representation.Footnote 3

These cases illustrate different levels of representation at the provincial level and shed some light on the causes of these differing results. The data presented in this article were derived from fieldwork, including interviews with main indigenous political actors in the respective provinces.Footnote 4 They are complemented by a review of secondary literature.

The study proceeds to examine the Peruvian state’s response to growing indigenous demands and the design and complicated implementation of the indigenous quota at the subnational level throughout the country. It draws from the literature on gender quotas and ethnic political parties in new democracies to propose a new theoretical framework. This framework combines sociostructural variables with the characteristics of political leaders to explain variations in the political representation of indigenous peoples. The article proposes a typology that brings together descriptive and substantive representation, using four case studies to demonstrate the interrelation between these forms of representation, as well as the importance of the proposed theoretical variables. The article concludes by summarizing the main research findings, problematizing the Peruvian state’s institutional response to the demands of indigenous people, and proposing new topics for future research.

The Peruvian State’s Weak Response to Indigenous Demands

The creation of the Quota of Native Communities, Peasants, and Native Peoples and its implementation by the Peruvian state at the subnational level fits squarely within the succession of legal innovations at the national, international, and continental levels with respect to indigenous peoples, innovations that have turned indigenous peoples into subjects of rights (Sieder Reference Sieder, Lennox and Short2016).Footnote 5 Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), approved in 1989, recognized the collective rights of indigenous peoples in international legislation for the first time (Sieder 2002; Van Cott Reference Van Cott2000; Yrigoyen Reference Yrigoyen2011) and influenced the wave of multicultural constitutional reforms that took place in the 1990s.

During the same period that these constitutional reforms emerged, policies for indigenous political representation experienced changes as well. According to Aylwin (Reference Aylwin2014), two broad policy categories have developed in relation to the political rights of indigenous peoples in Latin America. On the one hand, governments adopted policies that promote participatory rights of indigenous peoples. These imply the possibility of gaining proportionally fair representation. For this, electoral jurisprudence, electoral districts, and electoral laws are used. The subnational indigenous quota approved in Peru in 2002 belongs to this first type of political innovation. On the other hand, governments also introduced policies that promote rights to autonomy. Such policies seek to protect traditional indigenous institutions, organizations, and practices, and the ability to make decisions about priorities in indigenous territories, such as standards for prior consultation or indigenous autonomy (Rodríguez-Garavito Reference Rodríguez-Garavito2011).

The Introduction of Peru’s Indigenous Quota

The indigenous quota was introduced after the fall of the Fujimori regime (1990– 2000), amid the country’s transition to democracy under President Alejandro Toledo (2001–2006). Toledo’s administration introduced the quota, to be applied at the subnational level to “native communities and indigenous peoples,” as part of broad constitutional reforms intended to promote decentralization and modify electoral rules.

During his election campaign in 2001, Toledo highlighted his indigenous heritage and promised increased government responsiveness to the demands of these peoples (Thorp and Paredes Reference Thorp and Paredes2010). Toledo originally put forth a proposal for ambitious constitutional reform that intended to feature a chapter dedicated to the rights of indigenous peoples, but in the end, the reform held little significance (Alza and Zambrano Reference Alza and Zambrano2014). However, during the consultation process, the Decentralization Commission, which represented civil society organizations and indigenous peoples, proposed a series of constitutional reforms that sought to create special electoral districts with reserved seats in legislative bodies at both the national and subnational levels (Chueca 2018). This would effectively guarantee the representation of indigenous people in Congress and both regional and provincial councils (Htun Reference Htun2004; Van Cott Reference Van Cott2005). However, this measure was rejected by most of the political parties represented in Congress, who justified their opposition by asserting that such a precedent would allow other groups to claim similar rights.

In the face of this opposition, Congressman Javier Diez Canseco, representing a leftist political party, defended the inclusion of an indigenous quota in the constitutional reform bill, arguing that it was similar to the existing gender quota (Chueca 2018). In 1997, the Peruvian government adopted the Organic Election Law (No. 26859), which incorporated, for the first time, a gender quota of 25 percent.Footnote 6 This quota was also incorporated into the Municipal Election Law (No. 26864) adopted the same year.

In 2002, the approval of Law No. 27680 amended Article 191 of the Peruvian Constitution, elevating the indigenous quota to constitutional status. This reform required that at least 15 percent of candidate slots on the ballot be reserved for representatives of “native communities and native peoples,” in provinces and districts where such communities existed. This constitutional reform had an immediate effect on both the Municipal Election Law (No. 26864) and the Regional Election Law (No. 27683), which were, respectively, amended and promulgated in 2002.Footnote 7 However, although these laws established the guidelines necessary to incorporate the indigenous quota’s minimum percentages, the percentage requirements were not applied during the subnational elections of 2002. This was because the wording of Article 191 of the Constitution, which proposed that the quota be applied “where there is an indigenous population,” ignored the limited capacity of the Peruvian government to identify such areas (Del Castillo Reference Del Castillo2012).Footnote 8

In the 2006 elections, the National Electoral Board (Jurado Nacional de Elecciones, JNE) established that the quota would be applied in 11 (out of a total of 25) departments (regions) where “native communities” existed.Footnote 9 By using the term native, the quota mainly applied to indigenous communities of the Amazon.Footnote 10 This decision excluded the indigenous communities of Peru’s Andean regions, which had been legally reclassified as “peasant communities” during the country’s agrarian reform, led by the military regime of President Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968–75). After the 2006 elections, the National Institute for the Development of Andean, Amazonian, and Afro-Peruvian Peoples (Instituto Nacional de Desarrollo de Pueblos Andinos, Amazónicos y Afroperuanos, INDEPA) requested that the quota be extended to Andean communities.

The quota’s exclusive application to “native communities” breached the constitutional mandate that it be applied to all indigenous peoples, which should have included Andean peasant communities. In response to this allegation, in 2010 the JNE issued resolutions No. 200 and No. 247, which corrected the previous exclusionary interpretations, allowing for incorporation of several Andean peasant communities in subsequent municipal and regional elections.

The identification of provinces where the quota should be applied improved from 2010 to 2014, largely due to the adoption of 2011’s Law of Prior Consultation of Indigenous Peoples (No. 29785) and the creation of the Database of Indigenous or Native Peoples.Footnote 11 This database has developed over time, resulting in an increase in the number of provinces that qualifed for the application of the indigenous quota in 2018, in both the Andes and the Amazon. As such, the number of provinces where the quota has been implemented has grown from 30 in 2010 to 95 in 2014 and 131 out of the total of 195 provinces for the 2018 elections.Footnote 12

The population of Peru’s provinces varies greatly, and as a result, the number of elected councilors in provincial governments also differs significantly. The provinces that employ the quota choose between 5 and 15 councilors; therefore, the number of indigenous candidates that political parties must place on the election ballot ranges from 1 to 3. In the provinces with 5 government council members, the ballot features a place for one native candidate. At the other end of the spectrum, provinces with 15 council members, the ballots contain 3 of these candidates. Throughout the rest of the provinces, the ballot has places for 2 indigenous candidates.

Quota vs. Reserved Seats

As proposed by Htun (Reference Htun2004), unlike gender groups, reserved seats are preferable for the representation of ethnic groups. While (gender) quotas are more suitable for groups that crosscut partisan divides, reserved seats are more useful for constituents who fall firmly within a partisan group (such as ethnicity). Groups, such as indigenous peoples, make claims on collective rights (e.g., territory, communal justice, language, among others). Reserved seats can empower the entire group more directly, by strengthening both the bonds within the group and their collective demands (Htun Reference Htun2004, 450). In a sense, Peru represents a unique case, since most of the countries analyzed by Htun (Reference Htun2004) that have affirmative action laws for ethnic representation have a number of seats reserved at the legislative level. In Latin America, Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela have a certain number of seats (between one and seven) in the legislative chambers reserved for indigenous representatives (Fuentes and Sánchez Reference Fuentes and Sánchez2018).Footnote 13 These legal provisions also exist at the subnational level (Angosto Fernández Reference Ferrández and Fernando2012, 159–60).Footnote 14

The negative consequences of quotas, as opposed to reserved seats, are clear. Several authors (Htun Reference Htun2004; Van Cott 2005) have shown that quota systems discourage the formation of indigenous parties and thereby weaken (at least theoretically) the political representation of indigenous people. Van Cott (Reference Van Cott2005) observes that indigenous people’s efforts become splintered, resulting in isolated negotiations with existing parties in order to obtain a place on the ballot. In many cases, members of the same organizations or community end up competing against one another (Agurto Reference Agurto2003; Van Cott Reference Van Cott2005, 165–66). This can lead to the fragmentation of indigenous movements (Espinosa de Rivero Reference de Rivero2012) or the search for indigenous candidates who might not represent indigenous movements. Existing parties do not necessarily seek indigenous representation, but in most cases, reluctantly comply with the quota.

Given the lack of a placement mandate for ordering the candidates on the ballot, indigenous candidates, in many cases, end up serving as “filler” candidates (Espinosa de Rivero Reference de Rivero2012).Footnote 15 In a context where Peruvian legislation lacks reserved seats at the national level and tends to fragment indigenous organizations at the subnational level, the country’s indigenous quota is clearly constrained in its ability to promote indigenous peoples’ representation.

Quota Design and the Presence of Indigenous Councilors

Not only did the choice to implement an indigenous quota run counter to prevailing logics of political representation (Htun Reference Htun2004), but its design has also been shown to be relatively weak, resulting in critical limitations. As the literature on gender quotas maintains, the robustness of the institutional design of such quotas often varies greatly (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2009; Caminotti and Freidenberg Reference Caminotti and Freidenberg2016). This can simultaneously impact their effectiveness. In the case of Peru’s indigenous quota, the problems that have arisen are a result of the low required percentage of indigenous candidates on the ballot, the absence of a placement mandate, and the possibility of overlapping of different quotas.

First, the law stipulates that at minimum, 15 percent of candidates must come from indigenous communities. This percentage is considerably low, both in comparison to the percentage required by the country’s gender quotas (30 percent) and in relation to the overall number of the indigenous population in the provinces.Footnote 16 The current trend with gender quotas is to move toward parity (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2016); that is to say, half of a given ballot list consists of men and half consists of women. In contrast, the fixed 15 percent indigenous quota at the provincial level does not reflect the proportion of the overall indigenous population in these provinces.Footnote 17 For example, in provinces such as Condorcanqui (Amazonas), whose population is 91 percent indigenous, and Huarmey (Áncash), where indigenous people constitute only 6 percent of the total population, Peruvian law mandates that the same number of indigenous candidates be reserved on the election ballot.

Second, Peru’s indigenous quota law inherited a significant flaw from earlier electoral quota designs: it does not include a clear and systematic procedure for listing candidates’ names—a placement mandate—on the ballot. Consequently, indigenous candidates’ names generally appear last on election ballots (Pinedo Bravo Reference Enith2010), which makes indigenous candidates appear more as a “filler” for the ballot and leaves them little chance of being elected.Footnote 18 For example, in the Amazonian province of Bagua, on most provincial council election ballots, indigenous candidates appear listed eighth and ninth out of a total of nine candidates. Therefore, even if these parties won and obtained the automatic majority of council members, these indigenous candidates would not be elected to the council.Footnote 19

Third, the electoral legislation stipulates that the three existing electoral quotas (which pertain to gender, youth, and indigeneity) can overlap. In other words, a single candidate who meets the gender, youth, and indigenous criteria can satisfy all three quotas at once. This reduces the effectiveness of quotas and the possible representation of minorities, given that in many cases, young, indigenous women are put forth as candidates.Footnote 20 In the last subnational elections of 2014, only six of these candidates were successful, which suggests that these candidacies are particularly susceptible to being “filled” only to meet electoral regulations.

As a result of the weak design of the quota, its minimal objectives have been met with only limited success. In the 2014 elections, 116 indigenous councilors were elected, which corresponds to only 68.64 percent of the 169 required candidacies throughout all the provinces where the quota applied.Footnote 21 Only 44.57 percent (41 out of 92) of the provinces met (or exceeded) the minimum number of indigenous candidates on the ballot, as required by law. That is to say, if the quota of a given province requires two seats reserved for indigenous candidates on the electoral ballot and in the end, at least two indigenous candidates were elected (from one or different political parties), for the purpose of this article, the quota is considered “fulfilled.” Results also show variation by territory. For example, in provinces where two indigenous candidates were required on the ballot, it can be seen that between zero (Condorcanqui) and four (Carabaya) indigenous candidates entered the council, as per the quota. These results show, on the one hand, the weakness of the quota in practice, and on the other, the need to investigate possible explanations for the quota’s efficiency or inefficiency that extend beyond institutional factors.

Consequently, despite the quota’s weakness, Peru’s provinces show varying results in terms of indigenous (descriptive) representation. Contrary to prevailing scholarly skepticism toward the general effectiveness of the quota (Espinosa de Rivero Reference de Rivero2012), descriptive representation varies by territory, and even meaningful substantive representation can be found in terms of an indigenous people’s collective rights agenda.Footnote 22 Findings suggest that the effects of state policies regarding subnational indigenous representation are conditioned by local contexts and that actors adjust differently to the same institutional regulations. These findings coincide with arguments presented by Giraudy et al. (Reference Giraudy, Moncada, Snyder and Giraudy2019) about the divergent effect that statelevel policy has on subnational territories and the agency of the subnational actors, who can adopt, challenge, and even modify national-level policies and initiatives.

Indigenous Political Representation and Quotas: Theoretical Considerations

The literature on indigenous representation in Latin America has shown that there has been relatively little success in building successful and lasting indigenous party organizations. This sentiment is captured by scholars such as Madrid (2016, 308), who argues that in Latin America, “ethnic parties had more difficulties in obtaining support than ethnic parties in other regions [of the world].” In the context of Latin America, Peru is considered a particularly adverse case for the emergence of ethnic parties (Van Cott 2005; Martí i Puig 2008).

Various scholars have asserted that ethnic parties in Peru have generally had a minimal presence and have experienced limited success at both the national and the subnational levels (Madrid Reference Madrid2012; Paredes Reference Paredes, Meléndez and Vergara2010).Footnote 23 This is due to both institutional obstacles and circumstantial influences, as well as to specific factors related to indigenous actors themselves (Dávila Reference Dávila2005). Consequently, it comes as no surprise that there are currently no indigenous parties at the subnational level, given that the indigenous quota appears to undermine the objective of increased indigenous representation by dispersing indigenous leaders across various political parties.Footnote 24

However, despite the absence of indigenous parties, instances of indigenous political representation have begun to emerge in some provinces of the country. What factors, then, explain the subnational variation of indigenous representation in Peru? To better understand this disparity and to help shed light on descriptive and substantive representation, this article draws on the literature on gender quotas, an area that has received significant theoretical attention from scholars. At the same time, this debate is informed by Hale’s notion of “political capital” of political parties and their leaders in developing democracies (Reference Hale2006). The point of departure for literature on gender quotas is Pitkin’s seminal work on political representation (Reference Pitkin1967), which first conceptualized descriptive and substantive representation.

In short, descriptive representation is understood as correspondence between political representatives and their constituents in terms of their personal characteristics (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008). In this sense, it can be observed that political representatives are a reflection of those they represent. Following from this, descriptive representation then implies that a certain group or minority will have a numerical presence in the legislative body.

For its part, substantive representation is concerned with how much political representatives act on behalf of their constituents. In other words, it asks to what degree the agendas and preferences of constituents are reflected in the actions of their representatives. In a basic sense, substantive representation has two dimensions, related to procedural aspects and policy outcomes (Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Jennifer2008, 399–400). The debate around these dimensions is related to whether a political representative must achieve substantive results, in terms of adoption of public policies or other practical accomplishments (policy outcomes), or simply establish an agenda and propose projects (procedural aspect), irrespective of whether their projects or policies are approved or adopted into law and implemented. Generally speaking, current literature has been rather lenient, accepting either of these two dimensions as an indicator of substantive representation.

The two types of representation have different theoretical underpinnings. On the one hand, the literature has offered a series of factors that help explain descriptive representation and the effectiveness of quotas, predominantly related to institutional variables (e.g., the design of the electoral system), the strength of the quota design, and associated circumstantial variables (e.g., culture and socioeconomic conditions) (Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009; Krook Reference Krook2010; Caminotti and Freidenberg Reference Caminotti and Freidenberg2016; among others). However, the preceding explanations have been drawn primarily from analysis conducted at the national level (or meant to be generalized at the national or cross-national level); rarely have these findings been applied at the subnational level in a single country.

On the other hand, there is little consensus around the explanations of substantive representation. More important, scholarly debates have moved away from analysis of the causal relationship between descriptive and substantive representation toward a more fruitful debate that attempts to grasp the conditions under which the substantive representation of women occurs (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008; Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2008). In this sense, the literature has stressed the importance of “critical actors”— broad alliances that promote women’s interests and contextual variables that may influence such interests (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009). However, scholars generally disagree on who exactly is encompassed by the idea of “critical actors” and at what moment they emerge.

These approaches are particularly useful, as they emphasize the importance of feminist movements and women’s organizations in promoting their agenda and fostering their relationships with legislators (Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers Reference Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers2007). In the context of indigenous representation, social movements, and their relationship with political parties, scholars have largely recognized the key role that indigenous organizations play in political representation (Van Cott 2005). However, in the context of Peru, the indigenous movement at the national level has seen a substantial fragmentation, which is reflected and even more pronounced at the country’s subnational level (Paredes Reference Paredes, Meléndez and Vergara2010).

Relatedly, the literature on political parties in Latin America (and other regions) recognizes the importance of conflicts (and their duration over time) in both the formation and success of political parties (Levitsky et al. Reference Levitsky, Loxton and Van Dyck2016a; Eaton Reference Eaton2016; Reilly Reference Reilly2001). In the case of indigenous populations in Latin America, local conflicts (e.g., those related to mining and environmental issues) serve as crucial incentives for the political articulation of these movements, ultimately helping to generate cohesive indigenous organizations. This cohesion is manifested through the emergence of a common political platform at the provincial level, which helps unite indigenous peoples’ organizations and concentrate their collective actions. These cohesive organizations become critical vehicles for promoting substantive demands of indigenous peoples, and eventually their candidates can introduce this agenda to their provincial councils. Consequently, indigenous representatives in the provincial council are accountable not only to their (indigenous) voters but also to their indigenous organizations, in line with what the literature on the substantive representation of women suggests (Childs and Lovenduski Reference Childs, Lovenduski, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Laurel Weldon2013).

The literature on gender quotas also stresses the importance of contextual and intersecting factors at play in a given country during a given period of time (Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers Reference Beckwith and Cowell-Meyers2007) and highlights the need to understand the nuances of particular situations, and ultimately to separate substantive representation from descriptive. Thus, as Krook (Reference Krook2010, 235) acknowledges, most substantive representation studies have analyzed few cases, since such studies require in-depth contextual knowledge to understand the processes that have shaped observed changes and the promotion of a substantive agenda.

In the context of an inadequately designed quota system, it is hard to overemphasize the importance of the placement of individual candidates’ names on the election ballot, as well as their experience and personal trajectory. The literature on “political capital” (Hale Reference Hale2006) offers a theoretical approach that helps to understand how a candidate’s political standing influences the negotiation of his or her placement on the ballot.

Political parties offer two forms of political capital (Hale Reference Hale2006, 12), understood as a “stock of assets that can be devoted to the generation of political success” and that constitute incentives that enable parties to attract politicians to join their organization. On the one hand, the parties have “ideational capital,” understood as sets of principles and ideas with which the party identifies, which have generated a certain reputation among voters, which facilitate the creation of a certain brand or party label, and which should ultimately guide a candidate’s actions once the parties are governing. On the other hand, “administrative capital” represents the material, financial, and organizational resources candidates can avail themselves of in their interactions with voters (Hale Reference Hale2006, 12–15).

However, in Peru, the party system has largely broken down, as a result of the authoritarian rule of the Fujimori regime. Many political parties have been weakened, if they have not disappeared altogether, opening a political vacuum and fostering personalism in Peruvian politics (Levitsky and Cameron Reference Levitsky and Maxwell2003; Sánchez Reference Sánchez2009). As Zavaleta (Reference Zavaleta2014) shows, contemporary regional parties and movements are largely devoid of political capital and have instead morphed into “coalitions of independent candidates.” As a result, parties’ political capital has been replaced by “party substitutes.” This concept refers to “campaign technologies” that candidates use to substitute for the political capital historically provided by political parties in order to generate a “recognizable public image” and provide administrative resources (Zavaleta Reference Zavaleta2014, 68–73). These party substitutes often take the form of private companies, the media, or local political operators.

Given that the Peruvian political environment is averse to the formation of ethnic political parties, indigenous candidates generally do not even form what might be called indigenous coalitions of independent candidates. In fact, indigenous leaders “are selected [by political parties as candidates] using nondemocratic practices and without considering their commitment to their people or their ability to interpret and express [their] demands” (Desco 2010). What allows indigenous candidates to counteract these deficits is their own political capital, which serves as a party substitute, in Zavaleta’s term, and which ultimately helps convert them into interesting candidates for political parties (in the absence of ideological and administrative resources).

Indigenous candidates’ political capital is influenced by their trajectory as indigenous leaders, political experience, reputation, capacity to mobilize constituents, and organizational networks, as well as their material and financial resources.Footnote 25 This accrued capital serves as a bargaining chip in the negotiation with political party leaders and provides indigenous candidates with leverage to obtain a better placement on the ballot (Paredes Reference Paredes2015). Consequently, candidates with more experience obtain higher placement on the ballot list, giving them more immediate visibility to voters and increasing their chances of being elected—increased by the winning party’s automatic majority (50 percent + 1) of councilor seats.

However, political capital not only varies among candidates but can also vary greatly depending on the context of a given province. This is because, unlike gender quotas, where the percentage of women across provinces is relatively uniform, the percentage of indigenous population across provinces often varies significantly. Therefore, the amount of political capital a candidate can leverage in negotiation with political parties is largely contingent on the number of potential indigenous voters in their region. Correspondingly, in provinces where indigenous people comprise only a relatively small minority of the total population, the influence of a candidate’s political capital is diminished (and vice versa) (Zavaleta et al. Reference Zavaleta and Ragas2017).

The Theoretical Argument

The literature on gender quotas and political parties at the subnational level is also useful for understanding indigenous representation at the subnational level. Its theoretical contributions can help scholars understand how indigenous representation can be achieved even in a context hostile to indigenous political parties. The present article proposes a dual theoretical argument, dependent on the type of representation that constituents hope to achieve.

The first part of the argument relates to descriptive representation. It claims that this type of representation is explained mainly by the political capital of the indigenous candidates.Footnote 26 Meanwhile, little is explained by the variables outlined by the literature on gender quotas.Footnote 27 Given the weakness of the indigenous quota, its instrumentalization, and the fragility of political parties at the subnational level, aspiring indigenous candidates with substantial political capital can leverage this clout with political party leaders to attain favorable placement on the ballot, which, in turn, increases their chances of winning election. However, this relationship is mediated by the number of the indigenous voters in relation to the province’s total number of potential votes, given that limited indigenous presence can decrease the power of a candidate’s political capital and therefore have a negative impact on descriptive representation (Zavaleta et al. Reference Zavaleta and Ragas2017).

The second part of the argument refers to substantive representation. This article argues that this is the result of two necessary conditions that together are sufficient: the political capital of a candidate and the presence of cohesive indigenous organizations in the local political arena. This claim features two elements. On the one hand, in successful cases, leaders who join the council often represent those organizations whose agenda centers on a common political objective. In turn, those organizations usually hold the candidate accountable in terms of the proposals they put forward (or even get enacted) on the council.Footnote 28 On the other hand, the absence of organizational cohesion and articulation (resulting, in many cases, from a local conflict) explains the lack of substantive indigenous representation in cases that have potential for important descriptive representation.

The relationship between these two factors produces an explanatory typology (table 1). As proposed here, only the combination of candidates with political capital and cohesive indigenous organizations produces substantive representation (cell 1). In turn, although the presence of political capital is not enough for substantive representation, it can result in descriptive representation (cells 1 and 2) in contexts where a low indigenous population in the province does not diminish political capital. In other words, in certain cases, the combination of factors in cells 1 and 2 can produce descriptive representation.

Table 1. Explanatory Typology of Substantive Indigenous Representation

aThis combination of variables can produce descriptive representation depending on the proportion of the indigenous population in relation to the province as a whole.

Source: Authors

To analyze the descriptive and substantive representation in Peruvian provinces, the following criteria are proposed. On one side, in line with the literature on gender quotas, numerical criteria, drawn from the number of councilors who gained a seat on the provincial council as a result of the quota, are used to measure descriptive representation. The criteria established here consider the number of councilors elected in relation to the number of indigenous candidates required to appear on a political party’s candidate list in each province, as legally mandated by the quota. In consequence, descriptive representation is considered to exist when as many indigenous candidates are elected to the council as are required to appear on each ballot. If this requirement is not met, no indigenous representation is achieved.Footnote 29

On the other side, also drawing from the literature on gender quotas, the measurement of substantive representation is context-dependent (Zetterberg Reference Zetterberg2008). Given the heterogeneity among Peruvian provinces, it is understandable that the political demands across provinces are also equally heterogeneous. Therefore, it is very difficult to analyze indigenous demands by applying any deductive or universal criteria. Consequently, it is difficult to fully grasp advances in representation without doing fieldwork in the locality. In particular, the evaluation presented in this article is based on interviews with and information provided by principal local actors.Footnote 30

In this context, substantive representation refers to the promotion of indigenous interests and political agenda. Representation is considered to have been achieved when a council member(s) successfully advances any portion of an indigenous agenda proposal or achieves any change in provincial institutional structure or function that favors indigenous interests.Footnote 31 Although indigenous agendas and desired reforms are specific to each territory and locality, they are materialized through local public policies, new programs that serve the interests of indigenous people, or implementation of institutional changes in subnational governments. In practical terms, these advances are usually accomplished through joint collaboration between the municipal government and local indigenous social organizations, working to obtain resources and projects related to the interests of indigenous groups (e.g., negotiating with mining companies), drafting participatory budgets with communities, and making decisions via joint assemblies, and by the creation of special municipal offices for indigenous communities. Alternately, if the council member does not promote this agenda, there is considered to be no substantive representation.

Indigenous Representation at the Provincial Level in Peru

This article proposes a new typology of representation based on two forms of representation, descriptive and substantive (table 2). Here, the combination of these two dimensions questions the supposed association between a high level of descriptive representation and a high level of substantive representation, often treated as an explicit assumption by the literature (Just Reference Just2017). The four cases analyzed in this article represent the theoretical and empirical combinations of these two dimensions and allow for further analysis as to why, in some cases, these forms of representation do not occur simultaneously.

Table 2. Typology and Case Selection

Source: Authors

The selection of cases was largely determined by the dependent variable (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005), in order to explore the causal mechanisms that lead to the four (theoretically possible) results. Also, the selection was informed by two additional criteria. First, two cases from the Amazon region and two cases from the Andean region were analyzed, taking into account the differences between indigenous peoples across these regions, such as their organizational traditions, relationship with the state, and integration into the market economy (Greene Reference Greene2006).Footnote 32

Second, within these two regions, two cases were selected that have at least some degree of substantive indigenous representation (Carabaya and Tambopata). In the Andean region, the province of Carabaya (Puno) (see map 1) shows high values on both dimensions, and as such, represents a prototypical (ideal) case, with a high presence of indigenous council members and indigenous demands having been carried out. To provide contrast to the case of Carabaya, the case of Quispicanchi (Cusco) was chosen, given its high descriptive representation and sociocultural similarities with the Puno province; however, with substantive representation all but absent. Therefore, this pair of cases allows for the exploration of why high descriptive representation does not necessarily guarantee representation of indigenous interests.

Map 1. Quispicanchi and Carabaya

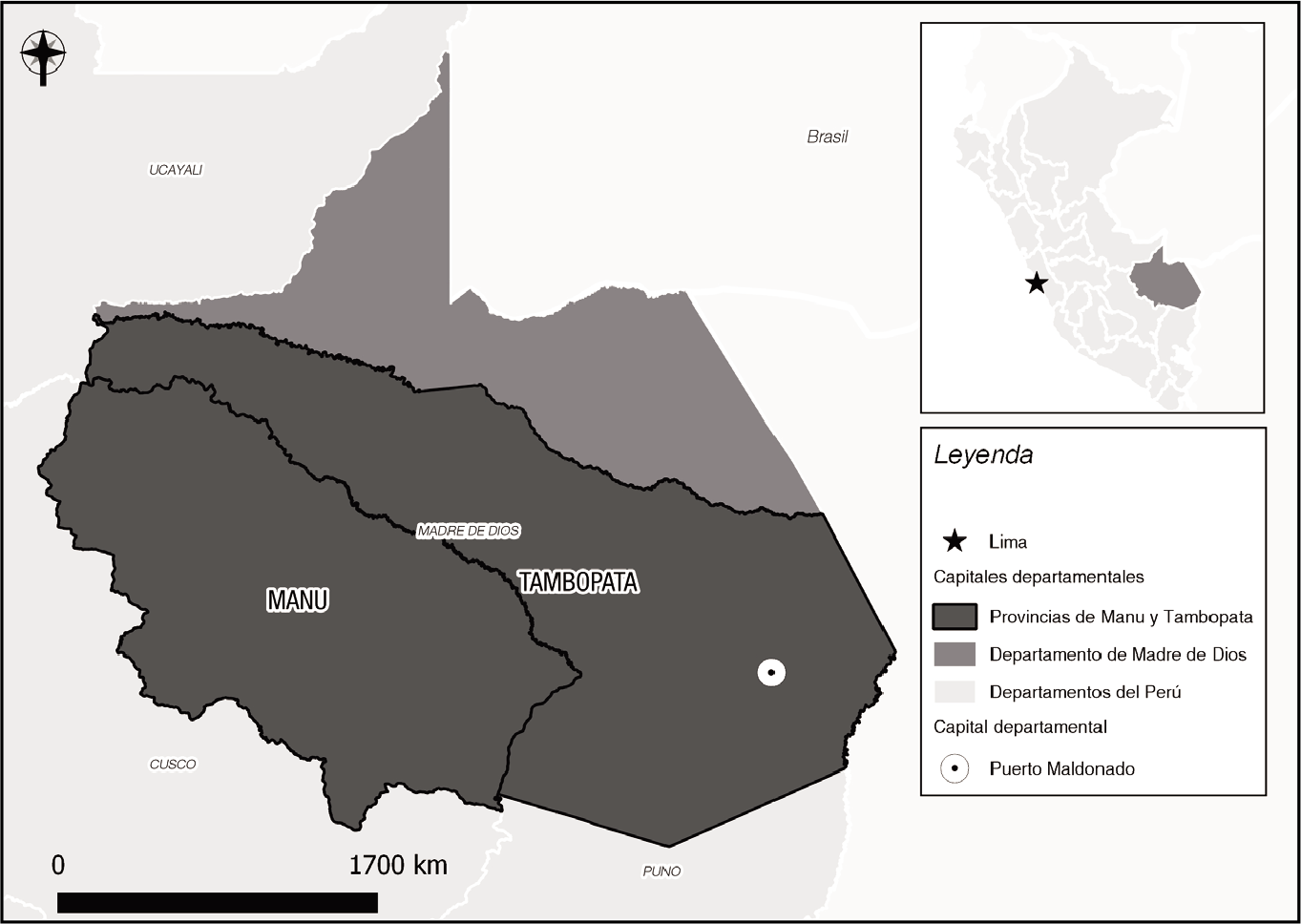

The Amazon region proved more difficult to find cases with substantive representation. Tambopata (map 2) is one of the few provinces where progress has been made in forwarding indigenous demands. Moreover, the case was selected because of its low descriptive representation and the very low presence of indigenous people, where it would be expected that the substantive representation of their interests would be correspondingly low. In comparison, the case of Manu complements the cells of the typology, as it is a socioculturally similar province to Tambopata and also features a high indigenous population. However, it has experienced low representation in both dimensions. Therefore, this pair of cases makes it possible to investigate the reasons for substantive representation in Tambopata, which, a priori, seems improbable, given the low presence of indigenous population and the low descriptive representation in the provincial council.

Map 2. Tambopata and Manu

The analysis presented here focuses particularly on the counterintuitive cases. On the one hand, descriptive representation does not necessarily guarantee high substantive representation (table 2, cell 2). In several cases, such as Quispicanchi, the presence of numerous indigenous councilors did not necessarily lead to the advancement of the indigenous agenda in the province. On the other hand, important substantive representation can occur despite the low presence of indigenous councilors (cell 3), who obtained a seat on the provincial councils as a result of the quota. The Tambopata case is representative of this latter scenario, as despite the presence of just one indigenous councilor, important institutional innovations at the provincial municipal-level government were achieved.

Intuitive cases are located in cells 1 and 4 of the typology. Regarding the former (cell 1), a high presence of indigenous councilors has led to the promotion of interests of their social organizations. The case of Carabaya illustrates the most logical combination of the typology, which is representative of the relationship proposed by the theory. As for the second intuitive case (cell 4), it shows the relationship of low descriptive and low substantive representation. In the case of Manu, the absence of indigenous representatives on the council hinders the development of an agenda that reflects the interests of their organizations, even in provinces with relatively large indigenous populations. However, it is argued that this may be due to both the weakness of indigenous organizations and their lack of cohesion and to these organizations’ decision to abstain from participating in institutional electoral policy.Footnote 33

Analyzing the two counterintuitive cases (Quispicanchi and Tambopata) demonstrates the article’s main argument and how the combination of factors, such as the presence of social conflicts and indigenous leaders’ organizational trajectory in their respective provinces, helps explain the results in terms of substantive representation (table 3). The two intuitive cases (Carabaya and Manu) are not developed here for limitations of space, but are presented in the online appendix.

Table 3. Comparison of the Four Cases

aThe descriptive representation in this case obtained the maximum instrumentalization of the quota.

Source: Authors.

Quispicanchi

The province of Quispicanchi in Cusco (Southern Andes) is an example of the (theoretically) paradoxical combination of high descriptive representation and low substantive representation. In the 2010 and 2014 regional elections, two of the nine provincial councilors belonged to indigenous communities, gaining access to the council as a result of the quota.Footnote 34 These councilors had held leadership roles in their peasant communities, organizations such as rondas campesinas, and one had been mayor of their district (Interviews 1, 2, 3).Footnote 35 However, at least the councilors elected for the 2010–14 period, interviewed for the research conducted here, had not succeeded in leading significant advances of an indigenous agenda. Therefore, this case represents an example of a double “instrumentalization of the quota.” On the one hand, indigenous leaders with experience can negotiate with political parties to gain an advantageous placement on the ballot list, given their knowledge and support in the communities. On the other hand, political parties agree to place these indigenous leaders on the ballot in order to meet the quota, which may, at the same time, increase the party’s number of overall earned votes.

The instrumental use of the quota owes a lot to the social landscape of this province, as social relations in Quispicanchi are very fragmented. Local organizations, such as the rondas campesinas, the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Agrarian Federation (FARTAC), or the Cusco Departmental Federation of Peasants (FDCC), have all failed to articulate a political project around a common indigenous agenda. This has largely been due to the historical absence of an exogenous conflict, which catalyzed these groups to coalesce into a more cohesive coalition (Asencio Reference Asencio2016). Without a common enemy or conflict, indigenous leaders are called on individually by different political organizations, missing crucial opportunities to represent a more cohesive indigenous movement that promotes their demands. On the contrary, after winning the election, only one out of the three councilors remained associated with the same indigenous organization as before their election (Interview 1). Therefore, we might conclude that parties value only candidates’ individual political capital.

The lack of cohesion and the fragmentation of social organizations has not been the only difficulty. Indigenous associations have generally possessed few resources of their own, and as a result, have often relied on their connections with political parties, social movements, or nongovernmental organizations involved in peasantrelated issues (Asencio Reference Asencio2016). These types of dynamics are exemplified by the frameworks of FARTAC and FDCC. The resources indigenous leaders have secured from these organizations have allowed the former to deploy a series of initiatives, establish communication networks, develop a pro-peasant agenda, and provide fundamental training to local leaders of rural origin. At the same time, organizational dysfunction has nonetheless resulted in conflicts of leadership.

Consequently, the leaders of various indigenous organizations maintain that the council members do not represent the interests of peasant communities, and as such, descriptive representation still does not guarantee the establishment of a political agenda that reflects their demands (Interviews 5 and 12). The president of the ronda of the Vilcanota Valley supported this idea, maintaining that discrimination against peasant communities and their institutions is still prevalent (Interview 4). In this context, community leaders explained that in order to move their projects forward, it is more useful to engage directly with authorities, such as the mayor, bypassing entirely negotiations with the council (Interview 12). Under these conditions, indigenous agendas have little chance of being prioritized or supported by the council members, instead depending heavily on the mayor’s discretion to advance proindigenous causes.

Tambopata

The province of Tambopata (Amazon) serves as a contrasting case to Quispicanchi. Tambopata features a seemingly paradoxical situation of low descriptive representation combined with high substantive representation. Owing to their high levels of political capital, indigenous leaders have managed to participate in the last two elections (2010, 2014), with a male indigenous candidate one year and a female indigenous candidate the other. Although the quota requires at least two indigenous candidates on the ballot, only one indigenous representative entered the provincial council each of these two years: Alcimo Valles Pacay and Natalia Bario Visse.Footnote 36 This illustrates how a candidate’s political capital can be dampened when the indigenous population is low in relation to the province as a whole (16 percent).

In spite of these limiting factors, these individual representatives (low descriptive representation) have nonetheless managed to advance the agenda of indigenous peoples. Their main achievement has been the creation of a special municipal office for indigenous communities in the Municipality of Tambopata (Interview 6). This Deputy Management Office, which continued to function during the political cycle following the 2014 election, helps channel the demands of indigenous groups and maintain a constant dialogue between them and the provincial government.

These outcomes fit into the proposed theoretical argument, since they both have distinct leadership trajectories, as well as the support of and an engaged dialogue with their community organizations. The candidates for the provincial council not only were nominated and supported by their indigenous organizations, but also possessed past leadership experience. The councilor elected in 2010 had more than eight years of leadership experience in various roles in his community and related organizations. Although the case of Quispicanchi also demonstrates that personal experience is necessary to win election to the provincial council, indigenous organizations still must function cohesively in order to enact their collective agenda via the elected candidates This is what the case of Tambota shows. According to a Tambopata council member elected in 2010, the candidates in this province are generally strong for their cohesion to their communities, and therefore they do not depend exclusively on the political parties (Interview 6). In other words, the candidacies of indigenous councilors follow a strategy designed by indigenous organizations, whose objective it is to increase their political influence in the province.Footnote 37

Tambopata is part of the Amazonian department of Madre de Dios, where provincial indigenous organizations converge as members of the Native Federation of the Madre de Dios River and its Tributaries (FENAMAD). In Tambopata, the main members of this regional federation are the Indigenous Council of the Lower Zone of Madre de Dios (COINBAMAD) and the Indigenous Forest Association of Madre de Dios (AFIMAD). These associations’ location at Puerto Maldonado (the departmental capital) affords them a great logistical advantage, as they are more easily able to access the crucial resources and networks located there. Both COINBAMAD and AFIMAD have significant autonomy and greater control over their leaders, which has largely allowed these organizations to set their own agendas.

The most urgent demands of both organizations revolve around illegal mining and community land titling. These two issues have been at the center of critical and longstanding conflicts in the province, related to territorial security and the possession and legal restructuring (saneamiento legal) of land ownership between indigenous communities and settlers. To a large extent, these types of conflicts have served as the centripetal force, catalyzing the organizational articulation and cohesion of indigenous community associations like COINBAMAD.Footnote 38

Conclusions

This article has sought to explain the territorial variation in indigenous representation at the subnational level in Peru. In a context of a weak indigenous electoral quota, it has shown that representation depends particularly on the trajectory and experience of indigenous leaders who apply for candidacy via the quota. Additionally, representation is dependent on each province’s sociopolitical environment, where the presence of a conflict involving indigenous people evokes the support of local communities and catalyzes the cohesion of provincial indigenous organizations. Using a novel typology that combines the descriptive and substantive dimensions of political representation, this article has argued that high substantive representation occurs in provinces where social conflict strengthens indigenous organizations and their representatives capitalize on their own professional trajectory, capable of promoting an indigenous agenda at the provincial level.

As Htun (Reference Htun2004) has argued, the Peruvian state imposed a form of affirmative action that was institutionally weak while discouraging the creation of indigenous political parties. However, this article has revealed that in various provinces there is significant substantive representation of indigenous interests at the provincial government level, despite the absence of ethnic parties. This article has also argued that substantive representation is not necessarily dependent on high descriptive representation. As the case of Tambopata shows, the presence of only a few indigenous leaders on the council can lead to significant progress on the indigenous agenda. This is due to the organizational support provided by indigenous movements and their ability to negotiate with the political parties (and the candidate and the mayor) with which they affiliate. By contrast, the case of Quispicanchi illustrates how high descriptive representation is not sufficient to promote indigenous demands, given the absence of organizational support. These theoretically and empirically counterintuitive cases show that the relationship between these categories is more complex than previously posited by the extant literature.

The constant changes in the implementation and application of the quota show that the Peruvian state’s administration has been erratic, despite gradual expansion in the quota’s territorial coverage. However, this institutional affirmative action (indigenous quota) is not adequate to fully represent indigenous interests, since in many cases it weakens and undermines attempts to build ethnic parties. According to Htun (Reference Htun2004), as well as scholarly literature on Peru, the indigenous quota contributes to fragmentation and internal tensions in indigenous organizations. Therefore, if the cohesion of indigenous organizations depends on the presence of sociopolitical conflicts, the weakening of such social strife or the depletion of indigenous organizations could also weaken the substantive representation of indigenous peoples. Although ethnic political parties do not seem absolutely critical for indigenous political representation, their existence could prove a stabilizing force for such interests, contributing to representation that is steadier and that operates securely, irrespective of local influences.

In this sense, the Peruvian state should, at the very least, seek a stronger quota (with a higher percentage) that reflects the presence of indigenous people in each province and includes a systematic procedure for listing candidates’ names on the election ballot (placement mandate). That would prevent the instrumentalization of the quota and the phenomenon of “filling” candidacies. In an optimal scenario, the state would propose implementing reserved seats at the subnational levels while facilitating the formation of ethnic parties, as indigenous authorities desire (Espinosa de Rivero Reference de Rivero2012). Certainly, any institutional reform should provide for the extension of this institutional affirmative action at the national level, where indigenous representation is almost nonexistent.Footnote 39

In conclusion, this article calls on scholars to address the questions that have been left unanswered here. Since the research employed for this article has been principally inductive, further analysis is needed of indigenous representation in other provinces. In particular, it is necessary to gain a better grasp of the legitimacy and power of local indigenous organizations, their relationship with political organizations in the region, and the candidates who file for election as a result of the quota. This is even more important after the prohibition of district and provincial parties’ candidacies, since representation will fall exclusively on national parties or regional movements.

This raises the question, what impacts will these changes have on indigenous representation? Likewise, more research is required on the role of economic resources at the local level and the extent to which their greater availability contributes to negotiating leverage with political parties. Further research is also needed about the particular agendas of local indigenous organizations, in order to understand the how much these organizations’ interests and agendas converge or diverge, all of which complicates their cooperation at the national level.

Interviews

1. Councilor, Quispicanchi. Urcos, Cusco. September 2013.

2. Councilor, Quispicanchi. Urcos, Cusco. September 2013.

3. Councilor, Quispicanchi. Urcos, Cusco. September 2013.

4. President of Vilcanota Valley Rondas Headquarters, Quispicanchi. Urcos, Cusco. October 2013.

5. Assistant Manager of Development Office, Municipality of Quispicanchi. Urcos, Cusco. October 2013.

6. Councilor, Tambopata. Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios. October 2013.

7. President of COINBAMAD in Province of Tambopata. Puerto Maldonado, Madre de Dios. October 2013.

12. President of FARTAC (Federación Agraria Revolucionaria Túpac Amaru), affiliated with the CCP (Peruvian Peasant Confederation). Quispicanchis. September 2013.

Chueca, Adda. 2018. Author interview. Lima, September 7.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting materials may be found with the online version of this article at the publisher’s website: Appendix.