INTRODUCTION

It is my firm conviction that we can, and should, make this beautiful country of ours more prosperous and improve the quality of life of every Ghanaian … Indeed, we can, and should, build a Ghana that is prosperous enough to stand on its own two feet; a Ghana that is beyond dependence on the charity of others to cater for the needs of its people … My fellow Ghanaians, we can, and should, build a Ghana Beyond Aid. (President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, 6.3.2018)

On 5 November 2010, Ghana, a country that has been described as a ‘success story’ of aid effectiveness over the past three decades attained the status of a lower-middle income country (LMIC) with a per capita income of US$1,305. This was caused by more than a 60% upward adjustment of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from the initial estimate of GH₵25.6 billion to GH₵44.8 billion (Jerven & Duncan Reference Jerven and Duncan2012). The LMIC accolade coupled with the quest for economic and social transformation and reducing the country's dependence on official development assistance (ODA) (hereafter aid) by the current president of Ghana, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, has ushered in a new narrative of ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’ (GhBA).Footnote 1 The GhBA is part of the President's vision of actualising and using the country's resources in becoming a prosperous and self-reliant nation (Government of Ghana 2019). In fact, the President in his address on Ghana's 61st Independence Day celebration on 6 March 2018 described the GhBA as ‘a national and non-partisan call to harness effectively our own resources and deploy them effectively and efficiently for rapid economic and social transformation’ (Government of Ghana 2019: 8).

The call for GhBA is informed in part by arguments that although aid has played a significant role in Ghana's development, the country needs more than aid to achieve the desired level of economic transformation and development (see for example Hughes Reference Hughes2005; Whitfield & Jones Reference Whitfield, Jones and Whitfield2009; Adams & Atsu Reference Adams and Atsu2014). This resonates with arguments that seek to question the role of aid especially in many LMICs as aid typically accounts for a limited share of GDP and government revenue and plays a marginal role in development (Carbonnier & Sumner Reference Carbonnier, Sumner and Carbonnier2012). Moreover, the GhBA vision is fuelled by assumptions that limited economic transformation has been caused by a number of socio-economic and political challenges which has created entrenched path dependencies especially on ODA for the country (Brown Reference Brown2017; Whitfield Reference Whitfield2018). However, as Carbonnier & Sumner argue (Reference Carbonnier, Sumner and Carbonnier2012: 4), alleviating poverty, inequality and underdevelopment depends largely on domestic policies in LMICs ‘through political engagements rather than technical approaches’. Against this background, the Government of Ghana claims that the GhBA vision focuses on: (a) developing a national transformation agenda; and (b) reducing dependence on external aid but not rejecting aid. As part of efforts to promote economic transformation, the GhBA vision seeks to create opportunities for export diversification, industrial strenthening and upgrading that focuses on manufacturing and high-value services. In addition, it seeks to align external donor support with national priorities in promoting development. This, it is argued, will enhance the country's ownership of its development priorities (Government of Ghana 2019).

Against this backdrop, GhBA has generated a lot of attention among policymakers, politicians, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), mainstream media outlets and the Ghanaian public. This has garnered several stakeholder meetings and conferences (e.g. Moving beyond aid-revenue mobilisation G20-Compact with Africa) to discuss ways of ensuring Ghana's transition from aid dependence to ‘beyond aid’ (Government of Ghana 2017). For example, a GhBA Committee headed by the Senior Minister, Yaw Osafo Maafo, has been formed and a Charter and Strategy document launched in April 2019. Although GhBA has received a lot of attention in Ghanaian political and policy circles in recent years, relatively little is known about public perceptions and perspectives on GhBA. In particular, Ghanaians' understanding of GhBA and its associated implementation challenges remains poorly understood. At the moment, there has been little or no sustained empirical research on public perceptions on how the GhBA vision by the government is being understood and received by the general public. This article therefore addresses this knowledge gap. In doing so, it asks the following questions: How is GhBA understood from the viewpoint of the Ghanaian public? What are the underlying rationale behind the GhBA and potential challenges that stand to affect its actualisation?

Understanding public perceptions of GhBA is crucial because its successful implementation depends on the active participation and involvement of Ghanaians. As highlighted by the President of Ghana, achieving the GhBA vision requires attitudinal changes associated with the mindset of dependency and doing things differently by embracing the spirit and values of patriotism, honesty, respect, volunteerism and self-reliance (Government of Ghana 2019). For this reason, it is important to know the perceptions of people to whom the development vision will apply in order to win their support in its implementation. The Ghanaian citizenry are key stakeholders whose commitments are required in realising this development vision. Therefore, examining the perceptions and perspectives of the Ghanaian public about GhBA is crucial in informing policy decisions that will help to promote its implementation. This study is therefore timely and appropriate because of its potential to help policymakers and stakeholders involved in the implementation of the GhBA to know the perceptions and perspectives of the Ghanaian citizenry on the challenges and actions needed to move forward the policy agenda of GhBA. An examination of public perceptions and perspectives about GhBA is also important as the vision reflects the narrative of ‘beyond aid’ in many LMICs especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Carbonnier & Sumner, Reference Carbonnier, Sumner and Carbonnier2012; Janus et al. Reference Janus, Klingebiel and Paulo2015; Kumi Reference Kumi2017).

To the best of my knowledge, this article is the first to document public perceptions and perspectives about beyond aid narratives in SSA. In doing so, this article makes significant contributions to the empirical literature on beyond aid narratives by providing evidence from Ghana about how the country intends to wean itself off aid by utilising its own resources to achieve structural economic transformation and self-sufficiency in the implementation of its development agenda. The findings in this article have broader implications for Ghana and other aid-dependent countries given the relative decline in the importance of foreign aid in recent years (Moyo Reference Moyo2009; Mawdsley et al. Reference Mawdsley, Savage and Kim2014; Janus et al. Reference Janus, Klingebiel and Paulo2015).

Ghana presents an interesting example for examining the narrative of beyond aid gaining traction among many SSA countries in recent years. Most importantly, Ghana has played an active engagement role in development cooperation initiatives such as the Accra Agenda for Action and Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, which demonstrates its established relationships with development partners (Brown Reference Brown2017). Again, it has maintained a high profile of an aid recipient country which makes the Ghanaian context similar to that of many SSA countries experiencing changes in their level of dependence on external donor funding and support. Ghana is, therefore illustrative of the growing number of LMICs seeking to reduce their dependence on aid through the deployment of national resources and promoting structural transformation and development.

In this article, I argue that while GhBA is crucial for maintaining and promoting Ghana's ownership of national development priorities and structural transformation, mechanisms for propelling the beyond aid agenda are largely absent. The empirical findings suggest that at the moment, there are no clearly defined benchmarks for the GhBA vision. More significantly, constraints including the politicisation of development policies and agendas stand to undermine the realisation of GhBA. To this end, I suggest that achieving GhBA requires building a national consensus devoid of party politics around the national development agenda. Until this is done, the GhBA vision will continue to be a rhetoric of the ruling elites.

This article is structured as follows: I present a review of the literature on aid effectiveness and beyond aid narratives. This is followed by the research methodology and then an examination of how the GhBA vision is being understood by Ghanaians, its underlying rationale and the potential challenges that stand to affect its implementation. The last section discusses the findings and its implications.

AID EFFECTIVENESS AND BEYOND AID NARRATIVES

The literature on aid–growth nexus especially in SSA has received much attention (see for example Adams & Atsu Reference Adams and Atsu2014; Ojiambo et al. Reference Ojiambo, Oduor, Mburu and Wawire2015; Kumi et al. Reference Kumi, Ibrahim and Yeboah2017). However, there is fierce debate on the real effects of aid in promoting growth and development. Some scholars have demonstrated that aid has a positive impact on economic growth by bridging the saving–investment gap, mainly through complementing and supplementing domestic resources as well as increasing investments and human capital development (Hatemi & Irandoust Reference Hatemi and Irandoust2005; Duc Reference Duc2006; Minoiu & Reddy Reference Minoiu and Reddy2010).

On the other hand, some commentators have raised concerns about the effectiveness of aid in promoting growth and development (see Easterly Reference Easterly2005; Moyo Reference Moyo2009). The argument is that there is a marginal or negative relationship between aid and economic growth, due partly to donor interests and inappropriate recipient policies (Young & Sheehan Reference Young and Sheehan2014). Fungibility of aid also adds to its ineffectiveness because of its ability to crowd out private sector development and the lowering of competitiveness which negatively affects traded goods (Rajan & Subramanian Reference Rajan and Subramanian2011). Aid inflows are also known to have the potential of increasing rent-seeking among government officials (Duc Reference Duc2006). Dependence on aid also reduces ownership of a country's development priorities due to the imposition of donor demands and agenda (Whitfield & Jones Reference Whitfield, Jones and Whitfield2009; Brown Reference Brown2017). In addition, aid is harmful to country-owned development mainly because of its ability to shield incumbent leaders from the consequences of their negative actions (Booth Reference Booth2012). Foreign aid is known to have negative effects on institutional quality in low-income countries (Asongu Reference Asongu2013). For these reasons, it has been argued that reliance on aid alone will not be enough to promote growth and development in many developing countries (Ratha et al. Reference Ratha, Mohapatra and Plaza2008). A third strand of scholars argue that the relationship between aid, economic growth and development is mixed, mainly because of the role played by country-level factors including policy environments in determining and shaping the effectiveness of aid (Burnside & Dollar Reference Burnside and Dollar2000; Adams & Atsu Reference Adams and Atsu2014).

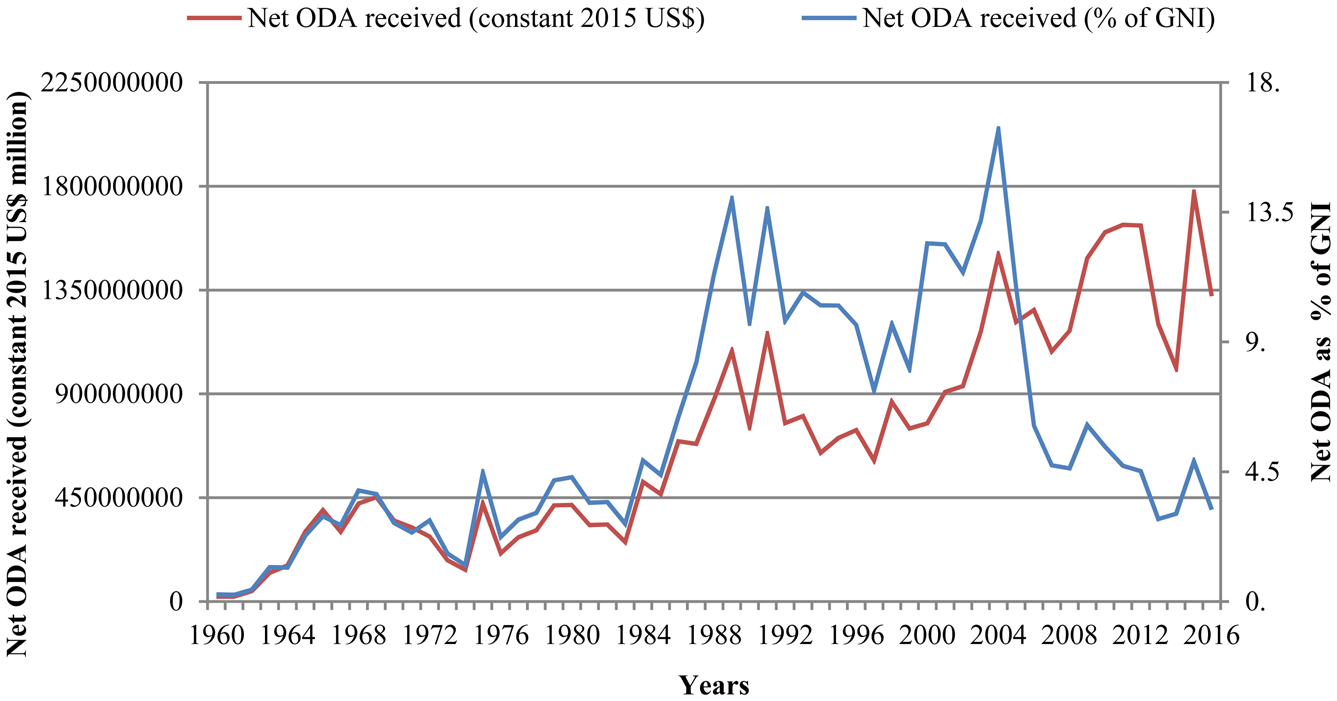

Despite the various debates on the effectiveness of aid, in recent years, what is evident is that the wider aid architecture is rapidly changing (Carbonnier & Sumner Reference Carbonnier, Sumner and Carbonnier2012). This transformation is caused in part by complex interlocking factors including the emergence of new development actors including Brazil, Russia, China, India and South Africa (BRICS) and the ascendancy of South–South cooperation, shifts in the geography of poverty, fiscal austerity in many development assistance committee (DAC) countries and the graduation of many developing countries into lower-middle income status following successive economic growth (Sumner Reference Sumner2013; Mawdsley et al. Reference Mawdsley, Savage and Kim2014; Kumi Reference Kumi2017). Many countries have graduated into LMIC status which has pushed them above the eligibility criteria for international development assistance. A typical example is the case of Ghana which has been experiencing a reduction in the inflow of donor funding. For instance, in 2009, net ODA accounted for about 6.1% of GDP but it declined steadily to 3.1% in 2016 with a further decline projected in the coming years (see Figure 1). Some commentators therefore argue that Ghana has transitioned from a highly donor-dependent country (NDPC & UNDP 2015; Brown Reference Brown2017). This has resulted in the increasing emphasis on the diminishing relevance of aid in what has been termed a ‘post-aid world’, ‘the end of ODA’ or ‘beyond aid’ (Mawdsley et al. Reference Mawdsley, Savage and Kim2014).

Figure 1. Trends in ODA inflows to Ghana between 1960 and 2016.

As part of beyond aid narratives, aid dependent countries are recognising the complementarity of aid to other development policies such as trade, technology, industrialisation and innovative development financing (Mawdsley et al. Reference Mawdsley, Murray, Overton, Scheyvens and Banks2018). In doing so, they are seeking to utilise their national resources with the view to guaranteeing room and autonomy to pursue their own development vision. This, it is argued, will help countries seeking to structurally transform their economies to break out of aid dependence (Whitfield & Jones Reference Whitfield, Jones and Whitfield2009; Whitfield Reference Whitfield2018). Therefore, in line with beyond aid narratives, many LMICs including Ghana are now seeking opportunities to utilise their own resources with or without the support of donors to promote their development vision.

However, to properly understand beyond aid narratives including the GhBA vision, it has to be situated within the context of the country's political economy. In particular, given Ghana's contentious electoral politics (see Bob-Milliar & Paller Reference Bob-Milliar and Paller2018), discussions of a GhBA vision through the promotion of structural transformation is fuelled in part by political incentives. For instance, Whitfield (Reference Whitfield2018) documents how the New Patriotic Party (NPP) under the leadership of President Kufuor proclaimed the Golden Age of Business as a way of distinguishing himself from the harsh stance of J.J. Rawlings and the National Democratic Congress (NDC) towards the private sector. Similarly, it could be argued that the GhBA vision is part of the economic policy agenda of the President and his NPP-led administration. The economic policy of the NPP focuses on the creation of an enabling environment for the active participation of the private sector in development through the use of national resources. The objective is to create jobs, increase industries and boost agricultural productivity in the country (Mensah et al. Reference Mensah, Bawole, Ahenkan and Azunu2019).

The rationale of economic policy initiatives such as ‘One District, One Factory’ and ‘One Village, One Dam’ was to distinguish the NPP from the NDC as the party of the centre-right following the run-up to the 2016 presidential and parliamentary elections which increased the election chances of the NPP (Bob-Milliar & Paller Reference Bob-Milliar and Paller2018).

As Whitfield (Reference Whitfield2018) argues, when governments in Ghana attempt to expand production, the state becomes the manager or owner of such productive investments. In fact, state interventions in the market through industrial policies such as ‘One District, One Factory’ have the potential of spurring private sector investments. In addition, due to the competitive nature of Ghanaian electoral politics, during the 2016 election campaign, the NPP accused the NDC of mismanaging the Ghanaian economy through dumsor (energy crisis), youth unemployment, unsustainable debt levels and unbridled corruption. The NPP 2016 campaign manifesto therefore proposed a radical transformation of the economy through policies including ‘One Village, One Dam’, ‘Free Senior High School (Free SHS)’ and rode on them to win the election (Bob-Milliar & Palmer Reference Bob-Milliar and Paller2018). For this reason, upon his assumption of office in January 2017, Nana Akuffo-Addo came up with the GhBA vision that seeks to promote structural transformation of the Ghanaian economy. The GhBA vision focuses on five main goals: wealth, inclusive, sustainable, empowered and resilient (WISER) Ghana. The GhBA vision is to create ‘… a prosperous and self-confident Ghana that is in charge of her economic destiny; a transformed Ghana that is prosperous enough to be beyond needing aid, and that engages competitively with the rest of the world through trade and investment’ (Government of Ghana 2019: 20).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This exploratory study draws on qualitative field research in understanding the perceptions and perspectives of Ghanaians on GhBA. The findings in this article draw on two data collection exercises. The first phase of data collection took place between April and July 2017, when 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted with CSOs, government officials and local donor representatives in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. For government officials, interviewees were selected from the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC), Department of Social Welfare (DSW) and Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation (MESTI). The aim of interviewing these government officials and bureaucrats was to seek their perspectives on their role and participation in the implementation of the GhBA vision. The interviews also sought to understand their perceptions on the driving factors and rationale behind the GhBA vision and its implications for Ghana's development.

While it would have been useful to interview government officials at the Office of the Senior Minister and the Ministry of Planning responsible for actualising the policy agenda of GhBA, getting access was a challenge and therefore officials from MOF, NDPC, DSW and MESTI were interviewed who provided useful insights on GhBA. Aside from government officials, Ghanaian development practitioners working for six bilateral and multilateral donor agencies, three international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and two philanthropic organisations were also interviewed. The aim was to explore their reactions, perceptions, understanding and implications of GhBA on Ghana's relationship with development partners. In addition, the interviews were useful in assessing the receptivity or the extent to which interviewees are aware of the GhBA vision.

The second phase of data collection took place between September and October 2018. It adopted a purposive sampling framework involving 30 semi-structured interviews and informal conversations with seven local academics at four public universities and eight key informants with considerable experience and understanding of Ghana's political landscape, foreign aid and development cooperation. In addition, 15 interviews were conducted in Accra with the general public or ‘ordinary citizens’ (e.g. masons, carpenters, taxi drivers, pharmacists, surveyors and bankers), development consultants and civil servants at the Ghana Cocoa Board, Social Security and National Insurance Trust and Ghana Revenue Authority. The aim of the semi-structured interviews and informal interviews was to explore the domestic interpretation, meaning and potential challenges associated with the implementation of the GhBA from the perspectives of the Ghanaian public and key stakeholders (Given Reference Given2008). This helped in identifying the similarities and differences emerging from the discussion between different segments of the Ghanaian public. While GhBA is often presented as a ‘unified national development vision’, the differences in interpretation and meaning have added to the complex nature of GhBA.

This research also drew insights from a media review of key stories relating to GhBA (e.g. Graphiconline, Myjoyonline, CitiFMonline, GhanaWeb), and published policy statements in relation to GhBA between September 2017 and December 2018. For the media review, a census count of major news media on GhBA was examined in tracking the debates and the identification of emerging themes from the discussions on GhBA. The interviews and secondary data were triangulated and validated to secure an in-depth understanding of the GhBA vision. This enhanced the validity and rigour of the research findings. Data analysis involved the use of discourse and content analysis. Discourse analysis was used in understanding how interviewees framed, made meanings and understood the GhBA vision (Given Reference Given2008). This helped in understanding differences and commonalities in meanings and interpretation ascribed to the GhBA vision. The secondary materials were subjected to content analysis. In the next section, I present the research findings.

KEY FINDINGS

Public understanding of Ghana beyond aid (GhBA)

The aim was to examine the views of interviewees about their understanding of GhBA. Although GhBA is an emerging concept, interviewees demonstrated that it has gained attention and represents an important issue within the Ghanaian political and economic landscape. While the Government of Ghana has conceptualised GhBA as a national development vision, interviewees explained that GhBA is a complex phenomenon with no widely shared understanding. In what follows, I highlight the key themes that emerged from the data analysis on how interviewees understood GhBA.

Declining significance and reduced dependency on foreign aid

A general understanding of GhBA by interviewees was related to the declining importance of foreign aid for Ghana's long-term national development. Fourteen interviewees explained that Ghana has depended heavily on foreign aid over the past decades, however, they tended to think of aid as a short-term facilitator rather than a major catalyst for promoting development in the long term. Arguing along similar lines, President Nana Akuffo Addo, during his speech on Ghana's 61st Independence Anniversary, stated that:

Nobody needs to spell it out to us that the economic transformation we desire will not come through aid. We have been on that trajectory for most of the past sixty-one years, and it has not happened … Aid was never meant to be what would bring us to the status of a developed nation.Footnote 2

There was a general perception among interviewees that foreign aid and external support has failed to bring about the needed economic and social transformation for Ghana's development. A key issue that interviewees felt had led to this included conditionality with its associated loss of ownership in the setting of national development priorities. A typical example cited was the conditions attached to the recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) Extended Credit Facility loan which has led to the placing of an embargo on public sector recruitment.Footnote 3 To put the discussion into context, the Mahama-led NDC government went to the IMF in 2014 for a bailout following the macroeconomic crisis (i.e. high public debt and huge wage bills) experienced after the 2012 general elections. While interviewees considered the IMF Extended Credit Facility as development aid (i.e. a concessional loan), it is important to clarify that it was actually a three-year stabilisation arrangement signed between the IMF and the government aimed at restoring debt sustainability and macroeconomic stability in order to foster a return to high growth and job creation. This notwithstanding, the majority of interviewees attributed the government's compliance with the loan conditionality to the country's dependence on donor resources. Similarly, a government official at the Ministry of Finance explained that for some Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) that are dependent on donor resources for their operational expenses, donors continue to act as influential stakeholders in shaping the priorities of the MDAs they support, which raises concerns about the country's ownership over its development priorities.Footnote 4

Against this backdrop, it was explained that GhBA is therefore aimed at reducing the country's dependence on foreign aid through, for example, the mobilisation of domestic resources. One interviewee explained this as follows:

Ghana beyond aid [GhBA] is all about domestic resource mobilisation. The President wants us to rely less on aid in the long-term by mobilising domestic resources in developing the country. I always say that foreign aid is not the solution for Ghana's development.Footnote 5

The above statement resonates with the government's view that GhBA is about transforming and growing out of dependence on aid but not rejecting aid in its entirety. For example, a government official at the NDPC explained that the transformation envisioned in GhBA requires a mixture of domestic resource mobilisation and foreign private investments.Footnote 6 The official explained that as part of the GhBA vision, foreign aid and external donor support will be aligned to the country's strategy for economic transformation. This statement affirms the position of the government in the GhBA Charter that ‘any aid (concessional loans or grants) will have to be aligned with Ghana's transformation strategy and priorities in order to be accepted into the budget’ (Government of Ghana 2019: 13).

On domestic resource mobilisation (DRM), as part of efforts to ensure the utilisation of national resources for development, interviewees explained that the government is taking measures to broaden the tax base and increase DRM through the introduction of a Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN), national identification card and digital property addressing system. Speaking about the linkage between the TIN and DRM, an official at the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) explained that although the majority of Ghanaians are potential taxpayers, only a small minority are registered with the GRA. There are an estimated 6.1 million potential taxpayers in Ghana, but only about 1.5 million are registered with the GRA. In particular, many informal workers are non-tax payers. The government therefore aims to use the TIN as a mechanism for ensuring that all potential taxpayers become duly registered.Footnote 7

Interviewees were clear in sharing their understanding of GhBA as a mechanism to reduce the country's dependence on foreign aid while harnessing its own human and natural resources. They expressed the view that it is important for the government to run the economy on national resources, including revenues from oil, cocoa and timber, rather than being dependent on foreign aid. However, the consensus was also that GhBA does not mean that the country will not be taking external donor resources and support; rather it will be complementing the government's resources. Thus, GhBA considers foreign aid as complementary rather than a supplementary resource for national development. This understanding by interviewees aligns with the government's position that GhBA is not about rejecting donor support. However, according to a senior officer at the Ministry of Finance, although in recent years, Ghana has been experiencing aid reduction and donor withdrawal, the country has put in place mechanisms for addressing the funding gaps arising from the declining levels of foreign aid. Ghana becoming a lower-middle income country has also made negotiating donor conditionality much harder. He explained that donor funding volatility affects government's long-term planning. Against this background, GhBA serves as a transitional policy for ensuring that in the absence of donor funds, Ghana will be prepared to take its destiny into its own hands:

It is a fact that since Ghana's transition into lower-middle income status, our access to concessional funding, grants and even technical assistance have gone down. So we can't rely on donors to develop our country for us. If we don't do something now, a time will come that the aid they give us will dwindle. So it's better we start from somewhere with the GhBA vision.Footnote 8

Indeed, some interviewees argued that the country should be able to cater for certain basic social services such as health, education, sanitation and water resources without the support of donors. By doing so, they felt that this will restore some sense of self-respect for the country in the eyes of donors. According to interviewees, donors tend to disrespect the views of government officials mainly because of the country's dependence. For instance, a government official explained that ‘because they are bringing the money, they think that, they can call the shot, change things when they want and disrespect your views’.Footnote 9

GhBA as the economic policies of the NPP-led government

During interviews, when asked about their understanding of GhBA, some interviewees responded in the affirmative that it was about NPP government's economic policy initiatives such as Planting for Food and Jobs (increasing agricultural productivity, farm income and job creation), One Village, One Dam (the government's programme to build 570 irrigation dams in Northern Ghana) and One District, One Factory (the district industrialisation programme). According to interviewees, GhBA is understood as the economic policies and vision of the president and his NPP government aimed at transforming the economy from the production and export of raw materials to industrialisation. It was also emphasised that the economic policy agenda of the NPP government focuses on building a stronger business-friendly economy and restoring macroeconomic stability through monetary and fiscal discipline.

According to interviewees, as part of the economic policy agenda of the NPP government, GhBA relates to addressing unemployment problems through job creation. They maintained that while Ghana has witnessed sustained economic growth, this has not been matched by new entrants into the labour market. As one key informant explained, the ‘jobless growth has had devastating effects, especially on the unemployed youth’.Footnote 10 Government initiatives such as One District, One Factory and the establishment of the Nation Builders Corps are geared towards the creation of jobs for unemployed graduates and the youth in general. However, concerns were that while such initiatives are aimed at helping Ghana achieve its long-term development vision, they are considered in the words of one interviewee an ‘NPP slogan’ and therefore simply a political language for politicians.Footnote 11 The interviewee further explained that although GhBA was not explicitly mentioned in the 2016 manifesto of the NPP, the party promised to harness Ghana's resources for national development. For example, in their manifesto, the NPP explicitly stated that ‘our overall vision for Ghana is the development of an optimistic, self-confident and prosperous nation, through the creative exploitation of our human and natural resources’.Footnote 12 Some interviewees therefore felt that GhBA provides an opportunity for the country to reduce its dependence on foreign goods and external resources. One respondent suggested that this aligns with the government's economic policy objective of adding value to raw materials and the domestication of the Ghanaian economy through industrialisation.Footnote 13

GhBA as attitudinal change towards development

A section of interviewees explained that GhBA should not be understood as a national development plan with projects earmarked for implementation. Rather, it was to be seen as a vision that requires a fundamental change in attitudes and the way development is pursued in the country. For example, a government official at the NDPC explained that ‘GhBA is different from our national development plan in the sense that it focuses on changing the way we think about development. It's about the mindset of the people’.Footnote 14 In their explanations of GhBA, some interviewees felt that it was about changing the mindset and behaviour of dependency to one focusing on values that create the enabling environment for propelling development. For instance, an interviewee argued that a ‘bad attitude’ was one of the main hindrances to Ghana's development. To this end, the interviewee argued that ‘now it is more of attitudinal change than physical infrastructure. For Ghana to develop, it is not just about the economic policies but we need to have the right attitude. We have attitudinal issues towards our development problems.’Footnote 15 This statement echoes the assertion by President Nana Akuffo Addo that achieving the GhBA vision requires ‘embracing the discipline and change in mindset and attitudes that will enable us to do things differently and in a better way’ (Government of Ghana 2019). A key concern raised by some interviewees was that successive governments in Ghana have failed to address the country's development problems mainly because of the attitude of ‘business as usual’ and ‘I don't care spirit’ as one interviewee stated. Accordingly, some interviewees explained that the GhBA vision is about promoting values including a high sense of patriotism and civic responsibility among Ghanaians where the national interest is put above individual interests. It also involves the promotion of honesty and integrity as well as the spirit of volunteerism among the citizenry.

However, it was suggested by many interviewees that instilling a sense of patriotism and nationalism into citizens is difficult, especially in contexts like Ghana where the political settlement system is characterised by a ‘winner-takes-all’ mentality which makes individuals not associated with the ruling elites feel alienated from the governance of the country. As interviewees explained, this arises because the ruling elites are unwilling to relinquish their power and interests and often resist policies that serve the good of the wider society. The feeling of alienation is succinctly captured in the words of an interviewee:

Here in Ghana, if you don't know the big men [ruling elites], what you say does not matter. You can talk and talk, but it doesn't go anywhere. It's not what you're saying that they will take … Everybody is thinking about his or her interest that is why we're not moving forward.Footnote 16

An interesting observation was that although GhBA is presented as a national development vision, it was more popular among educated than uneducated Ghanaians. Analysis of interview data indicates that this was partly due to the fact that educated Ghanaians were more exposed or had information on GhBA from both print and electronic media (e.g. newspapers, radio and television discussions and online news portals) compared with their uneducated counterparts. Even among the educated elites, those with Development Studies and Economics backgrounds or practical experience with economic and political issues were more assertive in their description of GhBA than those from other disciplines. For instance, interviewees with backgrounds in Business and Commerce often understood and explained GhBA as measures to add value to Ghana's exports and also deepen trade relationships with neighbouring countries. For example, a senior officer at the Ghana Cocoa Board reported that GhBA is about harnessing the country's trade potentials with countries such as Côte d'Ivoire by adding value to the cocoa exports in addition to promoting the development of the private sector to bring about the needed growth.Footnote 17 This suggests that the perceptions and perspectives of GhBA is different among the various segments of interviewees as some were more exposed to information on GhBA than others. In what follows, I present findings on the different perceptions and perspectives of the Ghanaian public on the underlying rationale and interests of GhBA.

Rationale and underlying interests of GhBA

Interviewees reported that the NPP government is keen to promote GhBA as part of efforts to reassure the donor community that Ghana is committed to meeting its part of the Compact for Leveraging Partnerships for Shared Growth and Development (hereafter, Compact) signed with development partners for the period 2012–2022. During an interview, a key informant working for a bilateral donor agency indicated that GhBA was a ‘face-saving strategy by the government in its relationship with donors'.Footnote 18 It was explained that GhBA was a deliberate attempt by the NPP government to buy time with donors following the country's failure to honour the Compact. According to two officials at the Ministry of Finance and the Department of Social Welfare, the Compact was supposed to serve as a framework for guiding the relationship between the Government of Ghana and development partners. Among its objectives include the promotion of inclusive economic growth and sustained poverty reduction through the mobilisation of alternative development finance including domestic resource mobilisation.Footnote 19 The Compact was based on the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA) 2010–2013 and the Ghana Aid Policy and Strategy (GAPS) 2011–2015. However, it was suggested by donor representatives and government officials that the NDC administration shirked its responsibilities soon after signing the Compact with development partners. Also, although the government drafted the GAPS, its implementation according to an official at the Ministry of Finance is yet to be realised. To this end, the interviewees argued that successive governments have not been decisive in pursuing the Compact and attributed this to a lack of interest and political diplomacy. When asked about what accounted for the failure of the government to implement the Compact, an government official explained:

It's a very big question because with technical diplomacy, you are likely to have consistency in our engagement with donors but the political side, you can't predict. It hinges much on who is your Minister and what is the direction of the government, as to whether they favour grants or capital market activities. Our political diplomacy has gone down and largely, it has affected our inflows drastically.Footnote 20

Interview data revealed that the aim of the Compact is to put in place strategies for ensuring the effective and strategic use of external donor funding to promote Ghana's medium- and long-term development priorities following the country's transition to LMICs. Donor and government officials explained that the Compact serves as a framework that guides their relationship and it is informed by the principles of the Aid Effectiveness Agenda. The Compact's aim is to make Ghana an aid-free country by 2020. For this reason, it could be argued that GhBA aligns with donors’ interests and Ghana's long-term development priority of weaning itself from donor dependence. However, concerns were raised by interviewees that GhBA is a misplaced priority because the government has consistently failed to honour its responsibilities of the Compact. They maintained that given the tendency by the governing elites to use foreign aid in furthering their own interests (e.g. using donor-sponsored projects to impress their constituents), weaning Ghana from donor support is a daunting task because the political elites are not committed to doing so due to the benefits they enjoy from foreign aid. For example, a CSO leader argued that while achieving GhBA is possible, doing so will not be in the best interests of the governing elites because they often use donor funds to defray mismanaged domestic revenues.Footnote 21 Against this background, some interviewees felt that GhBA was a rhetoric employed by the NPP government in order to stay in the good books of donors.Footnote 22 It is therefore not surprising that the GhBA vision has led some donor representatives, including the US Ambassador to Ghana, Robert Jackson, to praise the current President as ‘more visionary than some recent Ghanaian leaders’ while the IMF has also praised him for promoting GhBA.Footnote 23

While the GhBA vision was perceived by a section of interviewees as a deliberate attempt by the government to buy time with donors, some also felt it could serve as an opportunity for promoting ownership of national development priorities. They saw GhBA as a long-term rather than a short-term development vision aimed at allowing the country to take control of her needs without falling prey to donor priorities, as one interviewee explained:

While GhBA might not be perfect, we need to start from somewhere so that we can have a say in how we want our country to develop over the coming years. Donors should not always impose their priorities on us … GhBA is a clear demonstration of leadership by the President to ensure that we own our development process.Footnote 24

The statement above suggests that ownership of national development priorities requires strong, disciplined and visionary leadership by the governing elites. This creates opportunities for the governing elites in winning the space to formulate and implement development plans based on national preferences. Some interviewees explained that GhBA is a demonstration and an understanding of domestic visions of development that guarantees ownership of the development agenda.

Despite this, there was scepticism among a section of interviewees about ownership claims associated with GhBA. It was explained that while Ghana has over the years had similar development visions, such as the Ghana Vision 2020 and the 40-Year National Development Plan (2018–2057), their actual implementation has been a challenge. A concern raised was that given the competitive nature of the Ghanaian electoral process, development policies are abandoned when there is a change of government. Interviewees explained that this has been a key feature of Ghanaian electoral politics where lack of continuity of a previous government's projects by the incumbent has become the norm. According to interviewees, this was partly due to electoral incentives and the tendency for politicians to claim credit for development projects, hence increasing their chances of winning votes. In fact, each government embarks on policies they perceive will distinguish them from their opponents. By doing so, the aim is to increase their chances of political survival.

In this regard, some interviewees felt that GhBA and its related economic policies of the NPP such as One Village, One Dam and One District, One Factory were to make the party more popular among the Ghanaian populace, hence increasing their chances of being elected in the 2020 general election. As an interviewee explained, politicians prefer to focus on short-term policies with the potentials for political payoffs.Footnote 25

Perceived barriers to the implementation of GhBA

This section explores the perceptions of interviewees on potential barriers to the effective implementation of GhBA. The findings focus on the absence of policy direction, politicisation of the national development agenda and lack of a national consensus on GhBA.

Ghana beyond aid and absence of policy direction

A recurrent theme was that while GhBA is an emerging issue, it suffers from a definitional ambiguity because it encompasses many issues that have been lumped together. The majority of interviewees said that there was a lack of clear policy documents to which Ghanaians could refer in relation to GhBA.Footnote 26 They expressed the view that no single policy instrument and document clearly defines the modalities and priorities of GhBA. This, interviewees argued, raises questions about the policy direction of the government on Ghana's vision of moving beyond aid:

My worry about GhBA is that the President and his people have failed to tell us what they mean by beyond aid. Are they talking about all the projects sponsored by NGOs from the Western countries? Or it's about donor grants and concessional loans? At the moment, we don't know. I think it's important for the President to define what he is calling GhBA.Footnote 27

Another interviewee stated:

I want to see the policy document for GhBA that I can refer to. When you ask the politicians: is there any document on GhBA? They always say no. Then, the question is: what is your policy direction? It has been over a year now and there is no document, even an abstract on GhBA … Now people are fed up with the political rhetoric.Footnote 28

An analysis of media reports revealed that the absence of a policy document creates difficulty in making GhBA a national development vision. According to the First Deputy Speaker of Ghana's Parliament, Joseph Osei Owusu, there is an urgent need for a policy direction on GhBA: ‘Once we are soaking on explaining what GhBA is, won't it serve all of us if we put something together as a document to guide all of us … So let's stop couching it here [and] let's concretise it for the country’.Footnote 29

A key informant also explained that although GhBA is presented as a unified policy agenda by the President and his NPP government, there are fragmentations and factional splits among the ruling elites in the party on what GhBA entails and it therefore creates problems in reaching a consensus on GhBA.Footnote 30 The interviewee went on to explain that given the high level of elite fragmentation within the NPP, it is difficult to find mutual interests aimed at driving the implementation of the GhBA vision. The issue of the lack of cohesiveness among the ruling elites of the NPP government on GhBA was a recurrent theme mentioned by interviewees. This was confirmed by analysis of media stories on GhBA. For instance, some leading members of the NPP, including Andrew Awuni, a former presidential spokesperson under the Kufuor administration, criticised the GhBA vision by arguing that: ‘if it were a project, there should have been actionable plans with timelines. How long is it going to take, 10-years, 20-years … or is it just a proclamation or statement?'.Footnote 31 Such statements expose the differences and fragmentations among members of the NPP on GhBA. For this reason, the lack of a policy direction for GhBA has led to several criticisms by the former president, John Mahama, who argued that:

There are many other things that this government [NPP] is doing in an ad-hoc manner. It is as if they are governing in a manner called government as you go because for every programme that is rolled out, there is no policy, there is no guideline.Footnote 32

The statement reflects concerns raised by some academics interviewed during this research. They explained that the lack of a clearly defined policy direction does not help in meaningfully interrogating the issues underpinning GhBA. It also speaks to the importance of knowledge in the conceptualisation of GhBA. While GhBA has now become a ‘local parlance’ for most Ghanaians, a notable consensus is that there is an apparent lack of understanding among interviewees about what GhBA entails. Interviewees found it difficult to understand and comprehend the key tenets and pillars underlying GhBA due to the absence of policy documents and direction.Footnote 33 This was exemplified in discussions with both political elites and ordinary Ghanaians including taxi drivers, masons and businesswomen on the streets of Accra.

Party politics and the politicisation of GhBA

Political ideas play an important role in shaping the design and implementation of national development agenda. Interviewees explained that because GhBA is a political idea about the vision of the NPP government for Ghana's development, the agenda could not be devoid of partisan politics:

I don't like how GhBA is politicised. You know in Ghana, you can't do anything without attaching politics to it. The idea is very good, but my problem is the way the politicians are going about it as if, if it works, only NPP people will benefit and not Ghanaians in general.Footnote 34

Speaking about how the nature of partisan politics affects national development, another interviewee added:

Let's forget about GhBA because it can only last for 4–8 years as it is a politically motivated idea. This is a country where our development agenda is centred on political party manifesto. So it becomes challenging to move beyond the 4–8 year term when the party leaves office. Many development policies and projects are always abandoned when there is a new government.Footnote 35

The above statement illustrates how GhBA has been embroiled in politics which is mostly around the inter-coalitional rivalry between the NPP and the opposition parties. An analysis of media discussions on GhBA revealed that while the NPP and its sympathisers perceive the concept as a better developmental vision for Ghana, leaders of opposition parties have discredited it by calling it names such as ‘political slogan’, ‘political agenda’ and ‘political rhetoric’. This demonstrates the importance of party ideological differences and its effects on the formulation of a national vision for development. For example, the immediate Vice President, Kwesi Amissah-Arthur, maintained that GhBA remains a political rhetoric.Footnote 36 Arguing along similar lines, leading opposition members including Bernard Monarh, Chairman of the PNC, indicated that ‘it [GhBA] is only a slogan’ while Felix Kwakye Ofosu, a Former Deputy Communication Minister in the NDC government, argued that GhBA was:

couched to hoodwink people into thinking that this government is on to something serious … and indeed the sloganeering has intensified. It has moved a notch higher, and it's assuming unbelievable proportions … Today he [the president] says there's going to be GhBA. The president appears to be mongering hope … what we require now in this our country is not lofty rhetoric.Footnote 37

Lack of national consensus on GhBA

According to interviewees, the lack of a national consensus is influenced in part by politicisation and the absence of policy direction for GhBA. They explained that the ideological divide and ‘endless’ political debates between the two dominant political parties (NDC and NPP) are unhelpful for national development. They further maintained that because GhBA is a national vision and requires a long-term process, its design and implementation cannot be achieved within the first or second term (4–8 years) of any political party. In this regard, it is important to rally the nation together irrespective of political, ethnic and religious differences. A recurrent issue raised by interviewees was that GhBA requires a multi-partisan and inclusive approach aimed at promoting national consensus on Ghana's development priority and agenda. Also, it is important to clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the MDAs in moving the GhBA vision forward because they act as designers and implementers of policies. Against this backdrop, in their attempt to involve stakeholders in the discussion of GhBA, CSOs, development partners, policymakers and government have organised stakeholders’ meetings on the framing of GhBA.Footnote 38

However, some interviewees (e.g. masons, taxi drivers and market women) expressed concern about the lack of proper consultations with the grassroots on their views on what GhBA should entail. At the moment, the discussions are mostly dominated by politicians, academics, CSO representatives and some private sector actors.Footnote 39 This is also because GhBA is in its infancy. However, in June 2018, the government set up the GhBA Charter Committee tasked with the responsibility of developing a charter for the vision. The Committee had representatives from government ministries, trade unions, teachers associations, industry players, students and other key stakeholders. Following their consultative stakeholder processes, the GhBA Charter was launched in April 2019.Footnote 40 In ensuring that GhBA becomes a national development vision, interviewees explained that it requires the government to develop strategies such as public education on the strengths and benefits of GhBA to citizens. This would help in positioning the agenda in the minds of citizens and requires taking into consideration contextual factors such as individuals’ socio-cultural backgrounds so that the agenda will be well understood by all Ghanaians, irrespective of their background.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This article's starting point is that in recent years, many lower-middle income countries are seeking to reduce their dependence on aid by structurally transforming their economies, which is leading to what is being termed ‘beyond aid’ (Janus et al. Reference Janus, Klingebiel and Paulo2015). However, discussion of public perceptions on how countries are preparing themselves to move beyond aid has received relatively little attention in the literature. This article contributes to our understanding of the changing nature of development cooperation and beyond aid narratives in Ghana.

This article highlights that while GhBA is an indication of the decreasing importance of aid in Ghana's long-term vision for development, there is lack of clarity on the meaning and understanding of the concept among most Ghanaians. This article has demonstrated that the Ghanaian public understood GhBA differently in terms of declining significance and reduced dependency on foreign aid, economic policies to structurally transform the economy from dependency on the export of raw materials to manufacturing and high value services, job creation and the creation of enabling environment for the private sector. In addition, it was understood as a vision aimed at changing the attitudes of Ghanaians towards development by promoting a sense of patriotism and nationalism. This demonstrates the difficulty in conceptualising beyond aid narratives across different contexts. The lack of clarity on the meaning of GhBA affirms the argument in the existing literature that the conceptual debates on beyond aid are in their early stages of development (Janus et al. Reference Janus, Klingebiel and Paulo2015).

However, the findings in this article demonstrate that in Ghana, the narrative of beyond aid focuses on issues including structural economic transformation and industrialisation policies. In fact, the discussions of beyond aid have neglected how countries are seeking to promote structural economic transformation and also take ownership of their development agenda through the utilisation of their own resources and ingenuity (Ratha et al. Reference Ratha, Mohapatra and Plaza2008; Janus et al. Reference Janus, Klingebiel and Paulo2015). In the case of Ghana, GhBA forms a key part of the government's roadmap for structural transformation and reflects the wider vision of Agenda 2063 for Africa over the next five decades. In this regard, the emphasis on a socio-economic transformation agenda by the NPP government in Ghana is not new (see Whitfield Reference Whitfield2010). Notwithstanding, as Whitfield (Reference Whitfield2018) highlights, the lack of mutual interests between ruling elites and investors creates difficulty for such industrial policies to produce any meaningful results. As this article highlights, economic policies that seek to structurally transform the economy and promote industrialisation such as GhBA are often promoted on the basis of political expediency of distinguishing the NPP administration from their political opponents.

This article has further demonstrated that the increasing emphasis on GhBA resonates with the wider attacks and criticisms of the effectiveness of aid (see Moyo Reference Moyo2009). The research findings suggest that some Ghanaians are sceptical about the extent to which foreign aid could help in promoting Ghana's long-term development. This is consistent with Adams & Atsu's (Reference Adams and Atsu2014) study that found that foreign aid has a negative effect on economic growth in Ghana in the long term. It is worth mentioning that the failure of aid to bring about the needed economic growth is caused by several external and country-specific factors including bad governance, policy environments, quality of governance structures and the architecture of the aid system (Burnside & Dollar Reference Burnside and Dollar2000).

The findings further highlight ownership of national development priorities as an underlying rationale for the GhBA vision. By reducing the country's dependence on external resources, it is assumed that this will create room for manoeuvre for the government to set its own development policies and implement them with its own resources. However, given that GhBA is in its early stages, the key question which remains unanswered is the extent to which GhBA will lead to ownership of policymaking processes. At the moment, while discussion of GhBA is gaining much prominence, the government still depends on financial and technical resources from donor agencies, especially in tax-related assistance as part of its effort to boost DRM. Support for DRM in Ghana by donors has received much attention because of the assumption that it reduces aid dependency and encourages good governance by strengthening political accountability relations between government and citizens. In doing so, the mobilisation of domestic resources has been touted as a key pillar of GhBA (Government of Ghana 2019). In addition, some donors continue to influence and shape the priority of some MDAs that are dependent on them for operational expenses. For this reason, it could be argued that despite the emphasis on GhBA, donors are intricately entwined in the decision-making and policy processes in Ghana. The involvement of donors, especially the IMF, in the policy processes of GhBA such as the maintenance of fiscal discipline and macroeconomic stability raises critical questions about the ownership of national development policy claims underpinning it. This finding corroborates existing studies on donor involvement in development policymaking and its unintended consequences in recipient countries (Hayman Reference Hayman and Whitfield2009; Whitfield & Jones Reference Whitfield, Jones and Whitfield2009; Brown Reference Brown2017).

Results from the analysis further show that while GhBA is a vision for long-term development, there is no legal framework and policy direction guiding the agenda. The lack of a binding legal framework for Ghana's national development policies may be linked to the nature of a political system where the country's development is based on the manifesto of political parties (Whitfield Reference Whitfield2018). In this regard, development policies and plans are mainly built on short-term political considerations. This is largely due to the politicisation of national development along party lines. Competitive clientelism within the Ghanaian political landscape exposes ruling elites to high vulnerability of losing elections and intra-elite contestations and fragmentations. In this regard, they tend to focus on short-term projects that have the potential of ensuring their political survival through vote winning (Oduro et al. Reference Oduro, Mohammed and Ashon2014; Whitfield Reference Whitfield2018). For instance, a critical analysis of the priority programmes (i.e. agricultural modernisation (e.g. Planting for Food & Jobs, One Village, One Dam), industrialisation (e.g. One District, One Factory), infrastructure, private sector and entrepreneurial development, social interventions (Zongo Development Fund, Free SHS), domestic resource mobilisation and protecting the public purse) of GhBA suggests that they could be political initiatives to appeal to voters in the coming general elections (Government of Ghana 2019).

The research findings suggest that subjective perceptions of the absence of policy direction, politicisation and lack of national consensus are important impediments to the realisation of GhBA. Politicisation creates difficulty in building consensus on national development issues. This is consistent with the observation by Gyimah-Boadi & Prempeh (Reference Gyimah-Boadi and Prempeh2012: 101) that ‘toxic politics’ does not create space for engaging in ‘principled policy-based disagreements’ on important national development issues. Party politics could have negative implications for national development and democracy if not managed well. This could lead to divisions along political lines where individuals’ allegiance is towards their political party rather than serving the national interests. It also promotes polarisation and fragmentation of electorates as they become less willing to engage in bipartisanship and compromise with opposing views. Polarisation and electoral fragmentation have been key features of Ghanaian electoral politics in recent years (Bob-Milliar & Paller Reference Bob-Milliar and Paller2018).

In conclusion, besides pointing to the changing nature of the aid landscape in many LMICs, this study highlights the desire of the governing elites to promote development through structural economic transformation by reducing their dependence on foreign aid. While the growing emphasis on moving beyond aid is a welcome development, this study highlights a number of potential challenges that requires addressing in order to realise the goal of GhBA. Based on the findings, there is the need for building a national consensus on the future of Ghana's development. This will require the government to come up with clear policy directions for promoting an inclusive national development as part of the GhBA vision. For Ghana to realise its dream of moving beyond aid, coordination between government and different development stakeholders including CSOs, the private sector and philanthropic organisations is much needed. Although it is not yet time to assess the achievement of GhBA and its wider effects on development cooperation, reducing aid dependency amidst the quest for structural economic transformation raises important questions, such as: will a ‘donor darling’ country ever move beyond aid? At the moment, it appears that discussion of GhBA is unfolding and evolving, but whether the ruling elites can wean the country from foreign aid and be in charge of its own socio-economic destiny remains to be seen.