Introduction

Our article discusses two Polish translations of Saʿdi's Golestān, one by Samuel Otwinowski and the other by Wojciech Biberstein-Kazimirski (hereafter Kazimirski) published in 1879 and 1876 respectively. We are interested in the cultural mobility and oral transmission of wisdom literature between the Muslim and Christian worlds as well as the different skopoi (purposes of the translation) and the translation strategies adopted by both translators: the literarily gifted dragoman Otwinowski and the precise scholar Kazimirski.

Though published in 1879, Otwinowski's translation was originally completed in the first half of the seventeenth century and is assumed to be the first or at least one of the very first renderings of Saʿdi's work into a European language.Footnote 1 It was made during a period of intense but turbulent political contacts between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (hereafter Poland) and the Ottoman Empire (hereafter Turkey), whereas Kazimirski rendered the Golestān in a completely different cultural and political atmosphere while making ends meet as an exile in Paris following the partition of Poland in 1795. The histories of their creations are micro-histories of a single displaced object and, as Stephen Greenblatt says, such peculiar, specific and local micro-histories constitute the overall cultural relationship between unexpected times and places.Footnote 2

Otwinowski’s translation should be the subject of our interest to the same extent as various material goods imported from the East, mainly men’s clothing, carpets, weapons and other items for personal use,Footnote 3 especially as the transfer of cultural systems is more challenging than the mass transfer of wealth.Footnote 4 In seventeenth-century Poland the adaptation of the products of material culture from the East was not accompanied by an adaptation of the products of its intellectual culture, since literary inspiration was sought in the West.Footnote 5

Kazimirski’s rendering, on the other hand, was made by a nineteenth-century orientalist educated in the West, and may be conceived of as an outcome of the academic movement of the Oriental Renaissance.Footnote 6 Completed and published in Paris, it was accurate, well-researched and richly footnoted and was thus aimed at satisfying a Polish readership’s epistemic thirst for knowledge of eastern culture.

Otwinowski and his Giulistan

Otwinowski was born between 1575 and 1585 into a family that belonged to a community of the anti-trinitarian wing of the Polish Reformation (so-called Polish Brethren).Footnote 7 Around 1604 he found himself in Istanbul where for six years he studied oriental languages, mainly Turkish as well as the basics of Arabic and Persian essential for translating Ottoman correspondence.Footnote 8 After returning to Poland, he began his state service, first as a translator on the Polish–Turkish border and then as a dragoman in the Crown Chancellery of Sigismund III Vasa (1587–1632) and, most likely, Władysław IV Vasa (1632–48). He probably died circa 1650.

His interests went beyond diplomatic issues and included historical,Footnote 9 folkloreFootnote 10 and literary topics. The fruit of the latter is a translation of the Golestān entitled Giulistan to jest Ogród różany [Giulistan That Is the Rose Garden] completed between 1604 (first journey to Istanbul) and 1640 (end of work as a dragoman).Footnote 11 However, as mentioned above, it was only published in 1879 as Perska księga na polski przełożona od Jmci Pana Samuela Otwinowskiego Sekretarza J. Kr. Mci, nazwana Giulistan to jest Ogród Różany [A Persian Book Translated into Polish by Dear Sir Samuel Otwinowski, Secretary to His Royal Highness, called Giulistan That Is the Rose Garden] by Wincenty Korotyński and Ignacy Janicki. It is impossible to say what happened to this manuscript from the time of its creation until 1841, when it was donated to Józef I. Kraszewski.Footnote 12 Even then it was still largely unknown: Kazimirski did not provide any information about it in the comments to his translation published in Paris in 1876.Footnote 13 It was for this reason that the editors of the Otwinowski’s translation wanted to “restore Otwinowski’s place in history and literature,”Footnote 14 as they were convinced that it was the first rendition of the Golestān into a European language and of a higher literary quality than its nineteenth-century counterpart. Their edition was based on a manuscript comprised of eighty-three cards from a collection of silva rerum Footnote 15 destroyed during World War II. It is therefore impossible to say whether this was the original manuscript or, as both suggested, a copy.Footnote 16

Initially, it was believed that Otwinowski translated the Golestān directly from Persian but it has since been established that his command of the language was too poor and he must have used a Turkish translation.Footnote 17 There are some linguistic features indicating a translation by relay:

(1) The Persian noun golestān was rendered in Polish as giulistan, i.e. its Turkish pronunciation gülistân.

(2) The name Muhammad appears as Me[c]hmet[/d],Footnote 18 which is the Turkish rendition of the Arabic Muḥammad and which was borne by six Ottoman sultans. This version was never applied to the prophet, called Muhammet by the Turks,Footnote 19 but the graphical forms of Mehmed and Muhammet are identical. Otwinowski followed the local pronunciation, which may also suggest a rather poor command of Arabic. The usage of Me[c]hmet[/d] is somewhat surprising as the western European form Ma[c]homet was more common in Polish at that time.

(3) The Polish orthography of (Arabic-)Persian names indicates a Turkish language filter, e.g. Kiey-Husrew ← Tr. Keyhüsrev instead of the expected Kej-Chosraw.Footnote 20

(4) A few Middle Eastern toponyms appear in their Turkified versions, e.g. Misyr ← Tr. Mısır instead of Mesr or Egipt.Footnote 21

(5) The usage of a few Turkish terms, not found in the Persian original, that had been previously adopted into Polish, e.g.: bajram “festival,”Footnote 22 in the sense of ʿīd al-ʾaḍḥā “the Festival of Sacrifice” ← Tr. kurban bayramı “t.s.”Footnote 23

Along with these linguistic features, there are traces of cultural elements that point to translation by relay: “1) ethnicities not mentioned in the Persian original, e.g. Bulgarzyn “Bulgar”;Footnote 24 (2) Istanbul (consistently called Konstantynopol “Constantinople”) is the background of some stories.Footnote 25

For these reasons in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Polish researchers accused Otwinowski of inaccuracy, distortions resulting from misunderstanding, taking too many liberties in his interpretation, and omissions, especially in Chapter 5 and 8. Their reservations were based on Kazimirski’s and western European translations.Footnote 26 Although they noticed discrepancies between the two Polish renderings,Footnote 27 there was never a question as to whether both translators had the same Persian text at their disposal. Meanwhile, the inaccuracies in Otwinowski’s translation, which were perceived as the traces of the translator, indicate rather that the intermediate text, i.e. the Turkish translation, must have been far from the original. The fact that we do not have this intermediary text does not allow us to identify whether minor changes had already made their appearance in the Turkish translation or if these came later in the Polish one, or during its rewriting into the silva rerum. This is the case for example when we read: “Gdybym widział dobrego, że nad studnią chodzi, / Nie wytrwałbym, bo przestrzedz takiego się godzi [If I had seen a good man that was going around a well, / I would not proceed to warn him as it is right to do so],”Footnote 28 where “good” substitutes “blind,” since in the original we find: “But if I see a blind man near a well / It is a crime for me to remain silent.”Footnote 29

For a long time, discrepancies between the original and the translation were considered to reduce the value of the latter.Footnote 30 However, the value of Otwinowski’s translation lies in its lively and vibrant language, as well as in its interesting translation strategy consisting of four elements: (1) archaization; (2) the use of genres developed in Polish literature; (3) domestication; and (4) foreignization. Due to these four elements Otwinowski was able to familiarize the Polish readership with the culturally alien and geographically distant work of Saʿdi. The appropriateness of his translation in relation to the original is not just to be defined in terms of its faithfulness. It should be considered in terms of his recreation of the universal character of Saʿdi’s Golestān. When looking for the paradigms that guided Otwinowski, we would do well to recall Horace’s maxim nec verbum verbo curabis reddere fidus interpres, because while working with the Turkish translation he skillfully rendered the style of the original. In his own version he implemented, somewhat unconsciously, the basic assumptions of the modern Nidaesque understanding of dynamic equivalence. Presumably, if his work had been published in print shortly after its creation, being close to the esthetic expectations of the seventeenth-century Polish readership, it would have had a measurable impact on the work of later poets and writers.

It was Janicki who pointed out that Otwinowski’s language was quite outdated for the times he lived and worked in. Janicki explained this by his long stay in Turkey and the lack of contact with living Polish language.Footnote 31 Such an assertion is difficult to accept since Otwinowski’s translations of Ottoman correspondence do not differ from the language norm of that time. He must have been driven by something else when he decided to age the Polish. There are two issues at stake: (1) a willingness to highlight a certain stylistic tonality; and (2) the urge to refer to well-known literary patterns. Firstly, archaization allowed Otwinowski to emphasize the didactic and moralizing character of the Golestān. Secondly, it could enhance the translation to better incorporate it into the natural habitat of Polish culture, i.e. to create the sense of “at-homeness” which is, as Greenblatt writes, “often claimed to be the necessary condition for a robust cultural identity.”Footnote 32

Archaization is closely related to the use of genres developed by Polish literature during the height of its development in the sixteenth century. Otwinowski combined the rhymed epigram, known in Polish as fraszka, and a type of tale, the powieść, related to the oral genre of the gawęda.Footnote 33 This inventive and precise solution enabled the domestication of the translation, helping him to bring the text closer to its audience.Footnote 34 The gawęda is a specifically Polish epic genre written in prose and verse. It has the character of a free, unpretentious story of varying length and is connected to the transformation of folk oral tradition into a written form.Footnote 35 As a genre it was informed by the literary esthetics of Romanticism, but its beginnings should be sought in the Baroque and Enlightenment culture of family or communal feasts, when various stories similar to those that constitute the Golestān were told in public and in private. Viewed in this context, Otwinowski’s priority is clearly the adaptation of the original text to its target culture. This can be compared to Du Ryer’s strategy of domestication (as opposed to Gentius’ academic approach). Otwinowski’s translation, like Du Ryer’s, Ochsenbach’s and Olearius’ renditions, is aimed at a wider audience, but though he partly domesticates the text, he does not eliminate the Muslim context of the original, as was the case of Du Ryer’s and (based on Du Ryer’s version) Ochsenbach’s Gulistan.

With regard to the domestication of Golestān, three levels can be distinguished: (1) linguistic; (2) literary; and (3) cultural.

On the linguistic level, domestication involved using the lexical resources of the Polish language, without weighing the translation down with terms unknown to a wider audience. Therefore, although the ethnonyms “Arab(in)”Footnote 36 appear in Otwinowski’s work, it is Turczyn “Turk” that is considered to be a Muslim par excellence,Footnote 37 e.g. “Ja przez księgi Mojżeszowe przysięgam, / jeśli źle przysięgam, niech Turczynem zostawam [I swear by the book of Moses / if I swear badly, let me be a Turk],”Footnote 38 while in the original we read: “The Jew said: ‘I swear by the Pentateuch / That if my oath is false, I shall die a Moslem like thee.’”Footnote 39

Accommodation to native lexical resources also caused the most common term for a Muslim ruler to be the noun cesarz “emperor,”Footnote 40 even if there appears the word sułtan “sultan,”Footnote 41 or padyszach “padishah, king.”Footnote 42 The custom of addressing Turkish sultans as emperors was widespread before and during the time of Otwinowski, as evidenced by, inter alia, fragments of the Pamiętnik Janczara (Janczar’s Memoirs),Footnote 43 which he knew and developed.Footnote 44

Domestication on a literary level was manifested by a bold procedure in the form of conscious disguised quotations of Kochanowski’s epigrams.Footnote 45 The fact that Otwinowski made use of them aroused the interest of the first researchers who were seeking an indirect influence of Saʿdi’s work on Polish poets before they could even have gained the opportunity to get acquainted with it thanks to Otwinowski’s translation. Janicki was the first to write about this and the idea was developed by Marja Wrześniewska, who believed that Otwinowski translated the Golestān because fragments of it were supposed to be known to Poles traveling to Turkey and Persia.Footnote 46 They were thought to have brought home with them anecdotes from the Golestān and told them to their relatives or friends. As evidence she pointed out one of Kochanowski’s most popular epigrams Na zdrowie (On Noble Health): “Szlachetne zdrowie / Nikt się nie dowie / Jako smakujesz / Aż się zepsujesz [O, noble health / Thou – all our wealth! / None thy taste cost / Till thou art lost].”Footnote 47 Kochanowski supposedly became acquainted with Saʿdi’s work thanks to his friend Andrzej Bzicki, who lived in Istanbul in the middle of the sixteenth century. However, he could have been likewise inspired by a paean in honor of Hygiea by Ariphron of Sikion (fifth/fourth century BC),Footnote 48 not Saʿdi, who wrote: “thus also a man does not appreciate the value of immunity from a misfortune until it has befallen him.”Footnote 49 The fact that Otwinowski rendered the quoted fragment changing its form but preserving the message: “nikomu zdrowie nie smakuje, aż jakiéj choroby skosztuje [health does not taste good to anyone / until he tastes disease]” is proof of an in-depth knowledge of Polish literature as well as of a literary mind.Footnote 50

Similar theses have been put forward concerning Story 10 from Chapter 4: “How knowest thou what is in the zenith of the sky / If thou art not aware who is in thy house?,”Footnote 51 which in Otwinowski’s translation reads as follows: “Jako ty widzieć możesz co się dzieje w niebie, / Kiedy nie wiesz, że w domu masz [kurwę] u siebie [How can you see what is going on in the sky / When you do not know that you have a (whore) at home]”Footnote 52 and vividly resembles Kochanowski’s epigram Na matematyka (On a Mathematician): “Ziemię pomierzył i głębokie morze, / Wie, jako wstają i zachodzą zorze; / Wiatrom rozumie, praktykuje komu, / A sam nie widzi, że ma kurwę w domu [H's measured … the earth and fathomed the depths / He kens whence the sun rises and whither it sets / The wind’s nature knows and futures foretells / He just can't see there's a whore in the house where he dwells].”Footnote 53 Can the coincidence between Kochanowski’s epigram and the story in the Golestān serve as an argument in the discussion regarding Saʿdi’s influence on Polish artists? Not necessarily. We may be rather dealing here with a wandering motif which developed independently in two distant regions of the world.

Cultural accommodation involved the removal of some symbols of Islamic culture which could have been more difficult for the Polish audience to understand. Hence, there is in Otwinowski’s translation no mention of the Kaaba: “O Arab of the desert, I fear thou wilt not reach the Ka’bah / Because the road on which thou travellest leads to Turkestan,”Footnote 54 as he proposed a different solution: “Boję się Arabinie, iżeć zbłądzić przyjdzie, / Bo droga, którą bieżysz, nie do Mechy idzie [I am afraid, oh Arab, that you will get lost / because the path you are going / does not lead to Mecca]”Footnote 55 replacing the Kaaba with Mecca. It is an example of dynamic equivalence when extra-textual factors force the translator to make changes in the text. The Kaaba of course is not Mecca but it is in Mecca, so the journey to Mecca also means the journey to the Kaaba. It is also an example of the preservation of the original religion but expressed in a way that is intelligible to the target audience.Footnote 56

Another example of cultural domestication is the consistent use of the term Bóg “God” instead of Allah (Pl. Alla[c]h), e.g. “Więc góra Tur między górami najmniejsza, ale przed oblicznością Bożą najwiętsza i najwdzięczniejsza [So the Tur (sic) mountain between the mountains is the smallest, but before God’s face it is the largest and the most grateful]”Footnote 57 which in the original is: “The smallest mountain on earth is Jur [sic!]; nevertheless / It is great with Allah in dignity and station.”Footnote 58 The fact that Otwinowski did not use the adapted term Alla[c]h (← Tr. Allah ← Ar. Allāh) at all may be proof of a deliberate act and willingness to emphasize the universal character of the Golestān—the noun Alla[c]h appears in the Polish literature at least from the sixteenth century and could easily have been used by Otwinowski.Footnote 59

Accommodation on a cultural level also involved what Święcicki criticized as a temptation to smooth out the translation.Footnote 60 Otwinowski was tempted by Polish esthetics and morality, especially in a considerably shortened Chapter 5 in which he replaced homoerotic threads with heteronormative ones, e.g. “W mieście Hemedan nazwaném, był kady (wójt) uczony, ale młody. Ten rozmiłował się jednego kowala w onémże mieście mieszkającego córki [In the city named Hemedan there was a qadi (vogt) learned but young. He was in love with the daughter of a blacksmith of that city],”Footnote 61 while the original refers explicitly to a boy: “It is related that the qazi of Hamadan, having conceived an affection towards a farrier-boy.”Footnote 62 What guided Otwinowski in selecting stories to translate from Chapter 5 (only eleven of an original twenty-three) was a different view of morality: some topics may have seemed distasteful to most of his audience, and so were altered or completely removed. If we consider the main goal of the Golestān to be moral education, then it would have made sense for the translation to adapt the text to the target culture’s moral codes.Footnote 63

The opposite of domestication is foreignization, i.e. externalization of the interest in elements of social and cultural life of different communities that are unusual from the European point of view. Otwinowski’s foreignization involved primarily the preservation of local color. The protagonists were not transferred to life in Poland, they remained in Damascus, Istanbul, “Indian Khorasan,” Syria or Iran. Foreignization concerned also Islamic terminology, but this is well balanced in terms of amount—an example of this balance is his choice to maintain Islam in the text, but also adapt the reference to the Kaaba and translate Allah. Nevertheless, researchers accused Otwinowski of not adding a glossary of oriental terminology. One question arises here: was mufty “mufti,” the term that Janicki put in his glossary attached to the edition of Otwinowski’s translation, really completely unknown to potential seventeenth-century readers? In the silva rerum it was underlined and in print it is in italics, but we do not know whether it was Otwinowski who wanted to replace it with another word or whether an anonymous copyist considered it problematic.Footnote 64 The first evidence of this lexeme in Polish dates back to the sixteenth century and it must be remembered that the perspective of nineteenth-century researchers differed from the knowledge of the seventeenth-century intended readers.Footnote 65 The long-lasting border with Turkey as well as regular diplomatic contacts with Persia left their traces in Polish in the form of borrowings from Asian languages. It is also difficult to presume that Otwinowski made his translation with a view to educating his audience about the Islamic cultures, since he did not treat the Golestān as a source of knowledge about the Orient, but rather as a timeless and universal work.

Otwinowski’s translation stands to a certain extent in contrast to the widely maintained assumption that cultural exchanges between Poland and the Middle East lacked a literary dimension.Footnote 66 Rather than practical obstacles, it was the perception of religious differences that limited intellectual exchange, since Poles looked at Muslims with great aloofness and often reluctance. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Poland, frequently called the antemurale christianitatis, native and translated texts of a clearly anti-Islamic character were circulating and the growing conflict with Turkey only fueled an anti-Muslim spirit.Footnote 67

Where did Otwinowski’s translation come from? There is no agreement on this. Some researchers believe that the affiliation to the Polish Brethren, which shaped the worldview of the entire Otwinowski family, was not without significance.Footnote 68 It is a fact that members of the Reformed churches were much more active in their contacts with the Muslim East. Hence, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in times of counter-reformation propaganda, the Polish Brethren especially were accused of favoring the enemies of Christianity.Footnote 69 The fact that his translation was largely devoid of elements directly referring to Islam, apart from the most basic ones such as e.g. Alkoran (Tr. Alkoran ← Ar. al-Qurʾān) “Quran,” indicates that the universal character of Saʿdi’s work was more important to him.

Otwinowski probably did not make his translation only for his fellow worshippers, assuming that he remained an Arian until the end of his life is not so certain, as he served the pro-Catholic Sigismund III (and perhaps also Władysław IV) and most likely converted to Catholicism. The Golestān as a universalist text had to be for Otwinowski a work that both entertained and taught everyone at the same time. That is why the Giulistan is more than just a collection of rudimentary factual pieces of information about the Orient. It is a collection of timeless, supra-local and supra-cultural practical advice on how to act morally and ethically, how to live in a manner that does not harm others and how not to become too proud of oneself. Since the whole is interwoven with humorous anecdotes and concluded with humorous epigrams, the form and nature of which were known to the audience at that time thanks to Rej or Kochanowski’s work, the final outcome is very suitable for any seventeenth-century Polish nobleman who liked to discuss varying topics during family and neighborly meetings.

Otwinowski’s translation was in manuscript form, but we do not know what became of it. It is also impossible to say today how, when and by whom it found its way into the silva rerum. However, it is puzzling that somebody decided to rewrite it for their own needs—the tradition of creating a silva rerum was a response to the decline of printing culture in the seventeenth century. Various texts were (re)written and exchanged with family and friends. Hence the question of how far Otwinowski’s translation could have traveled, even though it did not appear in print.Footnote 70 However, the fact that it lay forgotten for 200 years contradicts the thesis regarding its mobility. Unlike Persianischer Rosenthal or Rosarium Politicum, which inspired western European artists, Otwinowski’s translation did not affect Polish Baroque or Enlightenment ones. It did not find a place for itself in the Polish literary tradition, and its artistic potential was not used in any way by subsequent generations of artists. Thus, Otwinowski’s translation was not as mobile as some researchers imagined it to be. Did it appear too early for Polish culture, which was not ready to assimilate a landmark of eastern literature? Not necessarily. The fact that the translation remained unanswered by Polish culture was primarily influenced by various factors; inter alia, in 1647 the Sejm closed the printing houses belonging to the Polish Brethren, deepening the decline of printing culture in Poland, and between 1650 and 1655 Swedish troops ravaged the country, exacerbating a growing internal crisis. We can postulate that it was the victim of unfortunate circumstances rather than an isolated example of the adaptation of a product of a foreign intellectual culture that was ahead of its time, as Irena Turowska-Barowa claimed.Footnote 71 After all, at roughly the same time, Piotr Starkowski and Kazimierz Zajerski published their translations of the Quran, both unfortunately missing today.Footnote 72

Kazimirski and his Gulistan

The second translation of Saʿdi’s Golestān into Polish was by Kazimirski. His rendering was published in Paris in 1876, three years before the one by Otwinowski. The plight of Kazimirski’s efforts resembles to a certain extent that of Robert Falcon Scott’s Antarctic expedition: having published his allegedly unprecedented translation into Polish, he discovered, with some disappointment, that he had been anticipated in his endeavor by no less than two and a half centuries. Moreover, it turned out that the Baroque translation, though incomplete and inaccurate, was esthetically superior to Kazimirski’s.

Wojciech (Adalbert) Feliks Ignacy de Biberstein Kazimirski (1808–87) was a Polish orientalist, translator and lexicographer born in Korchów near Lublin during the period of Polish partition between Prussia, Russia and Austria. He began his studies of oriental languages in Warsaw in 1828. His first teacher was Luigi Chiarini, a professor in the theological faculty at the University of Warsaw, an Italian priest and linguist, and an outstanding specialist in Hebrew. Then, supported by the Polish nobleman, Tytus Działyński, he pursued his studies in Berlin, focusing mainly on Sanskrit, taught by Friedrich Wilken. In the meantime he dreamt of studying Arabic and Persian with Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy in Paris. Yet, at the outbreak of the November Uprising of Poles against the czar of Russia in 1830, Kazimirski returned to Warsaw and became involved in the Polish struggle for independence. After the defeat of the Polish army in 1831, he emigrated to France and settled in Paris. In 1839–40 he went to Iran and Turkey and served as a translator for the French diplomatic mission in Iran. During that time, he started using his cognomen (geonomen) de Biberstein. After his return to Paris, he was employed in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He died in Paris in 1887.Footnote 73

Among Kazimirski’s works, one should make special mention of the two-volume Dictionnaire arabe-français (1846–47, 1860, 1875), Dialogues français-persans (1833), and Początki języka perskiego: Rozprawa [The Beginnings of the Persian Language: A Dissertation].Footnote 74 Kazimirski was the first European to discover the poetry of the Medieval Persian poet Manuchehri-ye Dāmqāni (tenth/eleventh century). He published in 1876 a French translation of his poems entitled Divan-e Manuchehri. He is also the author of the earliest critical edition of Manuchehri-ye Dāmqāni’s divan entitled Menoutchehri: Poète persan du 11éme siécle de notre ére (du 5éme de l’hégire) (1886). Kazimirski’s other renditions include a translation of the Quran into French entitled, Le Koran: Traduction nouvelle faite sur le texte arabe (1840, 1841, 1844, 1848, 1850, 1852, 1855, 1865, 1869, 1876, 1880), translations from The Thousand and One Nights as Enis el-Djelis ou l’histoire de la belle Persane: Conte des mille et une nuits (1846), and, last but not least, his rendition of Saʿdi’s Golestān into Polish: Saadi: Gulistan, to jest ogród różany Sa’dego z Szyrazu [Gulistan, which is a Rose-garden by Sa’adi from Shiraz] (1876), dedicated to Tytus Działyński.

Kazimirski’s love of Sa’adi’s writings began when he was in Berlin. However, his project to translate the Golestān was put on hold until he received a grant from the Polish count Jan Działyński (the son of Tytus). The publication itself was supposed to improve the financial conditions of the Polish exile. In a letter to his friend he confessed: “Apart from the aesthetic pleasure derived from undertaking this work, I had in mind the idea of scraping together some pennies (if it sold out) in order to print a little work on the East written in French.”Footnote 75

Kazimirski meticulously studied the Persian text and spent three years on its rendition. He compared the available translations, as his ambition was to surpass all of them in terms of accuracy of translation and the academic quality of the commentaries concerning eastern customs and concepts.Footnote 76 The translator hoped that the Polish reader “could measure and estimate the differences in worldview between the East and West and their ways of expressing them.”Footnote 77 As an orientalist, he hoped that his painstaking endeavor would be appreciated, particularly in the academic milieu: “Should in the future any other work from the Muslim East become the subject of academic study or translation, I would have the right to be proud that the present translation of the Golestān, which gently familiarises the reader with the East and its outlook, thus far alien to him, has allowed him to appreciate more easily the beauties which he will encounter [in this book].”Footnote 78

Thus, Kazimirski conceived translation as the creation of a bridge between cultures which were ostensibly different but ultimately shared some ethical concepts. He felt especially qualified for such a mission as one of the few well-educated nineteenth-century Polish orientalist endowed with both a good command of Persian and an extensive knowledge of Muslim culture.Footnote 79

In the introduction to his translation, Kazimirski shared some of his concerns with the reader, expressed mostly in rhetorical questions:

Before publication […] once again I posed myself the following questions: “Does this literary piece of the East deserve translation?,” “Will it provide an intellectual benefit for Polish readers?” and “Bearing in mind such a great difference of imagery and style between West and East, is a rendition of this small Persian work feasible?” and last but not least, “Will it be received well by its readers?” I am able to answer all the questions but the last, and I do not dare to elicit the answer.Footnote 80

The translator then advertised the Golestān as a literary work of endless relevance and beauty:

It is rare that in the history of literature a purely literary piece retains all of its elementary value and freshness for the nation it was conceived in. Changes in social life, gradual evolution, the instability of imagery, and inconstancy of language in search of its ultimate form often condemn to obsoleteness works of the intellect once popular and admired by their contemporaries.Footnote 81

Praising the vivacity of Saʿdi’s work, Kazimirski compared the Golestān to Dante’s Divine Comedy, a medieval work exceptional in the history of European literature which, then as now, still maintained its popularity and comprehensibility among all European nations and which also stimulated competitive translations.Footnote 82 The translator invoked the words of Saʿdi, aware of the ageless nature of his writings: “Uszczknij listek z mego różanego ogródka, bo ten zawsze będzie świeży” [Take a leaf from my rose-garden, as it always remains fresh]”:Footnote 83

Another feature which makes the Golestān parallel with the Divine Comedy is the richness of content. Dante’s masterpiece, alternating between the sublime and the earthly, the horrific and the comical, the scientific and the personal, resembles to a certain extent Saʿdi’s work as it is also full of variety and humanistic in its message. Kazimirski’s translation, meant to introduce the Eastern perspective to Polish readers, emphasized, at the same time, the universality of the Golestān and despite “the difference of imagery and style between West and East,” the spiritual and intellectual vicinity of the work conceived in the Muslim world, foreign in appearance, but familiar in substance:

A God-fearing, pious, saintly man will encounter in this work by a Muslim writer, thoughts, expressions and ideas which correspond to his way of thinking, will notice that in the East people were apt to tear off the mask of hypocrisy, a man of worldly wisdom and common sense will find there an echo of his own observations; a skeptical ambiguity and paradoxes formulated as proverbs, which we call the people’s book of wisdom; a lover of jokes and farces will laugh at the anecdotes, whereas a deeply virtuous man will discover numerous expressions of empathy and higher aspirations. A few pages of this alluring work should probably be omitted, but then who would not wish to delete many pages from [the works of] classical writers: the divine Plato, the sweet Anacreont, the good Xenophon or even the pure Vergil?Footnote 85

Although the nineteenth-century orientalist declared his disapproval of the sexual content of a few pages in the Golestān, he did not censor the problematic Book 5 on love and youth, and rendered it in extenso.

After praising the virtues of the Golestān, Kazimirski goes on to mention previous translations of the work, starting with those in Latin by Gentius and Olearius and also refers to the one prior to theirs, an inadequate rendition by Du Ryer. Finally, the Polish translator concludes:

From Gentius’ translation, many anecdotes, stories, parables and sayings were transmitted to European writings without knowledge of their origin, and then were put into circulation under the names of others. In the preceding and present century the translations have multiplied. There are three in French and four in English, there are German and Russian renditions and there are certainly more in other languages. However, so far there has been no Polish translation, which, given the vicinity of Poland to parts of the East, and the existence of centuries-old diplomatic and trade relations, it is surprising that nobody was inspired to become more closely acquainted with Eastern languages and literatures and why knowledge of the East should have always been mediated by the West. Especially when this work deserved translation for so many reasons. I must confess that I felt flattered by the thought of being the first to render it directly from Persian to Polish.Footnote 86

Ironically, what the Polish exile failed to study carefully were the magazines issued in the partitioned Poland, which mentioned the existence of Otwinowski’s manuscript.Footnote 87 There are several reasons which justify his ignorance. Primarily, he had limited access to Polish publications and two brief remarks made by Kraszewski in his magazine, Athenaeum, in 1841 and 1842, were not widely known. Secondly, facing the cultural hegemony of nineteenth-century western Europe, he must have suffered from a sort of eastern European inferiority complex, which made him assume a priori the non-existence of a Polish counterpart of western translation efforts and ignore the intellectual activity of the former generations of Polish dragomans and missionaries, whose written accounts served as valuable reference material on eastern culture in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 88 Last but not least, his acquaintance with Asian languages and literatures was mainly mediated by western sources and western academic centers, the forerunners of modern philological studies.Footnote 89 Absolutely confident (or convinced a priori) of the huge gap between knowledge of eastern literature in Poland and western Europe, he felt eager to overcompensate for it and, thus, to deliver the best philological translation of an oriental masterpiece (and bestseller) to a Polish audience, a work that would surpass the relatively accurate and complete nineteenth-century European renderings of Saʿdi’s work, such as Karl Heinrich Graf’s Rosengarten (1846) or the extensively commented French translations of Nicolas Sémelet (1834) and Charles-François Defrémery (1858).Footnote 90

Kazimirski’s translation of the Golestān remains a product of the demand for universal humanism aimed at getting acquainted with the “foreign” and “different” which, at least in the case of the Orient, was perceived and presented not as contradictory but rather as complementary to the Occident.Footnote 91 He addressed his rendition to an “enlightened but non-academic” readership with a classical educational background.Footnote 92 His philological translation may serve as a Polish paragon of the Oriental Renaissance, based on the study of eastern languages and integration of oriental literature which was, as Raymond Schwab argues, an organic continuation of the first Renaissance, which had allowed European intellectuals to rediscover Greek and Latin sources.

A considerable part of Kazimirski’s edition is of an informative character. The translation itself is 220 pages, slightly more than half of his edition of Golestān (382 pages). The remaining parts comprise: an introduction (15 pages), a comprehensive biography of Saʿdi (24 pages),Footnote 93 which is anticipated by a short lecture on the history of Persian literature and language; commentaries to 622 footnotes (113 pages), a short polemic on etymological issues with a Polish orientalist in Russia, Antoni Muchliński and his book Źródłosłownik wyrazów [Etymological Dictionary] (3 pages),Footnote 94 and last but not least, an index of “important things” (personal names, toponyms, important topics and concepts; 7 pages). Judging by the extent of the introductory and explanatory parts of Kazimirski’s Golestān, they constitute the organic component of his work. It shows that apart from disseminating eastern moral teachings and providing amusement, the translator’s goal was to familiarize the reader with oriental culture and to satisfy the epistemic needs of a nineteenth-century readership, well-educated in western and Classical literature and eager to complete their education with a basic knowledge of the East. Kazimirski’s attitude to the Golestān shows a shift in the treatment of eastern literature during the Oriental Renaissance: it is not fully assimilated, but fulfills the esthetic and epistemic pleasures of an intellectually sophisticated audience and its thirst for knowledge of an exotic, but at the same time familiar, Other. This Other is not only geographically closer to central and eastern Europeans than western Europeans, but it is also closer to them in its religious life. This can be witnessed, for instance, in the attitude towards sacrum (religiosity, either Muslim or Catholic), the affirmation of a “noble” poverty (Pers. darvishi cf. Pl. cnota ubóstwa), or the ability to do without (Pers. qenā’at cf. Pl. skromność, poprzestawanie na małym).

Still, though his rendition received positive reviews as a philological endeavor, it failed to gain wider popularity. Just after its publication in 1876, it was praised for its completeness and faithfulness. The indisputable strength of Kazimirski’s rendition was the addition of the informative introduction and commentaries.

One of the translation’s first reviewers, Lucjan Siemieński, praised the general educational value of Kazimirski’s rendering but, for the same reason, he also questioned the validity of translating the whole content of Chapter 5 “which is not among the most beautiful passages of the book.”Footnote 95 He also disapproved of the “unnecessary promotion” of the practice of dissimulation (taqiyyeh) among Polish readers. Siemieński, himself an outstanding translator of literary masterpieces (including the Greek Odyssey or the Persian story of Bizhan and Manizheh from the Shahnāmeh),Footnote 96 appreciated the esthetic values of the translation:

In praise of the translator we should add, … that the rendition, though highly faithful, has lost neither its natural rhythm, nor the clarity intrinsic to our language. … Mr. Kazimirski’s verses are far from ‘wooden;’ they sound like poetry and possess poetic harmony [sic]. … Therefore this translation differs from many other translations into so called “blank verse,” which are deprived of metre and melody, have no poetic flair and resemble an assemblage of words which produce a cacophony, and often convey the meaning so awkwardly, that a reader must struggle to grasp it.Footnote 97

Nevertheless, though Kazimirski’s translations of Saʿdi’s versified punchlines “sounded like poetry,” they were, in point of fact, unrhymed.Footnote 98 He considered himself a scholar and not a poet and was not ready to risk his academic authority by composing what may well have turned out to be bad poetry. Therefore, he remained faithful to his goal of rendering the precise meaning of the verses, leaving aside the potential esthetic value of rhymed translation. His accuracy is also witnessed in the distinction he made between Persian and Arabic verses by adding the abbreviations w.p. (Persian verse) and w.a. (Arabic verse), which preceded his blank-verse renderings.

After the publication of Otwinowski’s translation, some critics compared both works and re-evaluated the esthetic values of Kazimirski’s rendition. According to an extremely severe review by Święcicki, Kazimirski’s Golestān, albeit assiduous and faithful to the original, is devoid of artistic merit. The majority of his blank verse is stiff and lacks poetic features.Footnote 99 Święcicki’s remark is only partly justified, as the main shortcoming of Kazimirski’s versed translations is the lack of rhyme. This disadvantage becomes the translator’s cardinal sin only when contrasted with Otwinowski’s smooth, rhymed verses. In conclusion to his assessment of the philological translation, Święcicki does justice to Kazimirski’s efforts by claiming that though his rendition fulfills epistemic functions and may serve as a reference for Poles studying Persian, it would hardly win widespread popularity. On the other hand, the language of the Baroque version of the Golestān is so smooth that it barely sounds like a translation. Therefore, Otwinowski’s rendition compensates for its shortcomings by being of greater artistic merit.

Otwinowski vs. Kazimirski

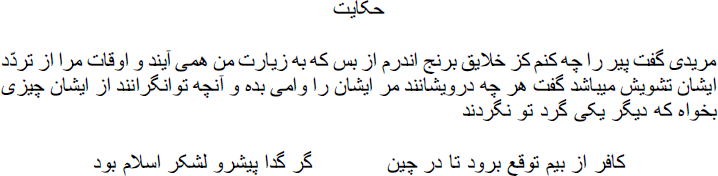

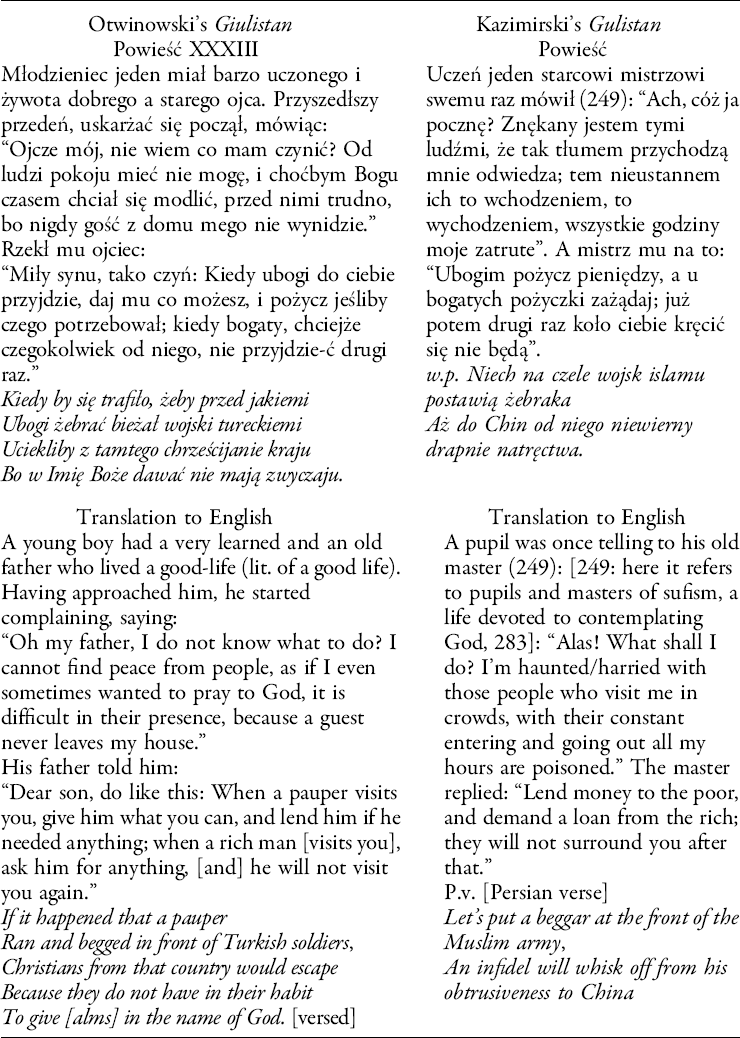

For the purposes of comparing the two translation strategies we have chosen a short story from Book 2 Dar axlāq-e darvišān (The Morals of Dervishes).Footnote 100

As we can see on the basis of this example, both translations of Saʿdi’s hekāyat (rendered in Polish as powieść, a term which today refers to the genre of the novel) are more extensive than the original highly concise story.Footnote 101 Otwinowski’s translation is far more elaborate and inaccurate, but at the same time it renders the meaning of the original story. By using the strategy of cultural domestication, he rendered the Muslim/Sufi terms of morid and pir as a “young boy” and a “a very learned and an old father who lived a good-life.” In this dynamic equation, the spiritual relationship between a pupil and his sufi master is replaced by a kinship, and the three adjectives describing the physical, spiritual and moral qualities of the father (old, very learned and who lived a good life), inserted in the text, spared him the necessity of referring to the religious context of the term pir. This omission of the religious context of the story is compensated later in the words of a boy who would sometimes pray to God, but is disturbed by others. Kazimirski, on the other hand, translates morid to “pupil” (Pl. uczeń) and pir to “his old master” (Pl. starcowi mistrzowi swemu) and adds a footnote explaining the Sufi context of the relationship of two protagonists of the story.Footnote 102 He also slightly archaizes the sentence by using an old-fashioned, inverted syntax (a pronoun swemu after a noun mistrzowi, similar to Persian order). What is peculiar to Otwinowski’s version is a translation of a distich which he conveys by a quatrain (with rhyme scheme aabb) corresponding to one of the variants of the Polish poetic genre of the fraszka. In his version of the poem, originally a “Muslim army” (lashkar-e eslām) is rendered as “Turkish soldiers,” whereas an infidel (kāfer) is translated to “Christians” (plural), and escaping to China (chin), the extremes of the Persian perception of the East, is replaced by escaping from one’s country in the West (i.e. a Christian one). The genuine eastern context of the verse is visibly westernized (“Turkified”) and the mischievous allusion to the avarice of infidels (who do not give alms) is aimed directly at Christians. This fragment underpins the assumption of the originally Turkish basis of Otwinowski’s translation. Quite astonishingly he maintains its message, which in the Christian context becomes self-deprecating.

Though his narrative is more elaborate than the original, Otwinowski also uses verbal ellipses which approximate his mode of writing to an oral style of story-telling and, at the same time, the conciseness (ijāz/ekhtesār) of Saʿdi’s own diction. Also Kazimirski, though by and large faithful to the genuine Persian text, introduces some devices, such as the exclamation Ach! (Alas!), to make the narrative sound more dramatic. Quite surprisingly, given his modus operandi, he does not comment here on the Muslim obligation of almsgiving (zakāt) which can be inferred by a competent reader from the original and is mentioned by Otwinowski in his poem (Because they do not have in their habit / To give [alms] in the name of God).

Conclusions

In conclusion, these two Polish renderings of Saʿdi’s Golestān, Otwinowski’s seventeenth-century translation by relay and Kazimirski’s nineteenth-century scholarly translation, exemplify different types of cultural transfer between East and West. The former as a dragoman lived in a Muslim country and was able to engage with Asian languages through oral as well as written culture. He sought dynamic equivalence, presenting what he saw as the universal message of the Golestān in a domesticated version which would appeal to the Polish nobility familiar with Kochanowski’s verses. The diction of his rendering is close to oral story-telling and the versified translations of even singular beyts are transformed into the Polish epigrammatic rhymed genre of the fraszka. This intensifies the didactic message and the amusing effect of Saʿdi’s punchlines and makes the stories, at least potentially, integrate well into the Polish broad genre of gawęda or powieść, suitable to be read for amusement and retold for enjoyment in the social gatherings of the Polish gentry. Unfortunately, due to unfavorable historical circumstances, it remained largely unknown until its rediscovery in the nineteenth century. While Otwinowski’s rendering is steeped in the Polish-Turkish context, Kazimirski’s translation seems more involved with a western European background. As a Polish exile, educated in Warsaw, Berlin and Paris, Kazimirski views his endeavor within the context of the German and French faculties of oriental studies, which were steeped in a philological approach. His aim is to deliver the most comprehensively glossed rendition of Saʿdi’s work in western scholarship showing that he could, as a Polish scholar, equal the western European authorities of the day.Footnote 103 Thus, he focuses mainly on familiarizing a Polish readership with Muslim and Persian culture, extending the Oriental Renaissance from France to Poland. Though it is not completely deprived of literary merits, it satisfied the epistemic demands of a well-educated Polish readership and may still serve as a reference for Polish students of Persian today.

ORCID

Mateusz M. Kłagisz https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0807-3290

Renata Rusek-Kowalska https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6513-9236