Introduction

Due to their richness in endemic species, oceanic islands are notable for their unique biodiversity (Myers et al., Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, Da Fonseca and Kent2000). With a peripheral situation within the Mediterranean Basin hotspot, the Canary Islands harbour the highest levels of endemism; for example, about 50% of their native flora and terrestrial invertebrates are endemic species (Juan et al., Reference Juan, Emerson, Oromí and Hewitt2000; Reyes-Betancort et al., Reference Reyes-Betancort, Santos Guerra, Guma, Humphries and Carine2008). This volcanic archipelago is located approximately 100 km off the north-western African coast in the Atlantic Ocean. It is comprised of seven main islands, whose geological history is well known, including the chronological sequence of island emergence (Ancochea et al., Reference Ancochea, Hernán, Huertas, Brändle and Herrera2006). The main islands present an east to west gradient in their formation, the oldest emerging around 20 million years ago (Mya) (Fuerteventura) and the youngest around 1.2 Mya (El Hierro) (Juan et al., Reference Juan, Emerson, Oromí and Hewitt2000; Ancochea et al., Reference Ancochea, Hernán, Huertas, Brändle and Herrera2006). Several studies have looked at the Canary Islands to study parasites and relationships with their hosts (e.g. Foronda et al., Reference Foronda, Figueruelo, Ortego, Abreu and Casanova2005; Roca et al., Reference Roca, Carretero, Llorente, Montori and Martin2005; Feliu et al., Reference Feliu, López, Gómez, Torres, Sánchez, Miquel, Abreu-Acosta, Segovia, Martín-Alonso, Montoliu, Villa, Fernández-Álvarez, Bakhoum, Valladares, Orós and Foronda2012; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., Reference Pérez-Rodríguez, Ramírez, Richardson and Pérez-Tris2013; Illera et al., Reference Illera, Fernández-Álvarez, Hernández-Flores and Foronda2015; Padilla et al., Reference Padilla, Illera, Gonzalez-Quevedo, Villalba and Richardson2017), some reporting exclusive forms and cryptic diversity (Foronda et al., Reference Foronda, López-González, Hernández, Haukisalmi and Feliu2011; Roca et al., Reference Roca, Jorge and Carretero2012; Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Perera, Carretero, Harris and Roca2013, Reference Jorge, Perera, Poulin, Roca and Carretero2018).

Haemogregarines (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina) are a ubiquitous group of heteroxenous parasites, which infect haematophagous invertebrates (definitive host) and all types of vertebrates (intermediate host) (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Telford, Reference Telford2009). A growing number of studies uncovering unknown diversity have increased interest in these parasites, otherwise constrained by the limited information and their taxonomy uncertainty (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Carranza and Harris2016a, and references within). Within the Canary Islands, a few studies have reported the presence of haemogregarines infecting reptiles (Oppliger et al., Reference Oppliger, Vernet and Baez1999; Martínez-Silvestre, Reference Martínez-Silvestre, Mateo, Silveira and Bannert2001; Foronda et al., Reference Foronda, Santana-Morales, Orós, Abreu-Acosta, Ortega-Rivas, Lorenzo-Morales and Valladares2007; Megía-Palma et al., Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2016; Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Rato, Perera and Harris2016), one alluding to the existence of possible multiple species based on morphological differences (Bannert et al., Reference Bannert, Lux and Sedlaczek1995). Recently, the first study on the genetic diversity of haemogregarines infecting reptiles across the archipelago confirmed the existence of marked genetic differences (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). In that study, we screened the three lizard host genera inhabiting the archipelago: Gallotia Boulenger, 1916 (Reptilia: Lacertidae); Chalcides Laurenti, 1768 (Reptilia: Scincidae) and Tarentola Gray, 1825 (Reptilia: Phyllodactylidae). We identified nine new 18S rRNA haemogregarine haplotypes (labelled A, B1, B2, C, D1, D2, E, F and T; and divided into seven haplogroups: A, B, C, D, E, F and T), a high diversity considering the small geographic area and number of host groups. Moreover, the different haemogregarines were highly specific to their lizard hosts and had different distributions: five of the haplogroups (A to E) infected Gallotia spp. hosts throughout the archipelago, while haplogroup F infected only Chalcides from one locality in Tenerife and haplogroup T only infected Tarentola from La Gomera and La Palma (Fig. 1). Besides the genetic differences, infection levels also varied across the three host genera (prevalence: 69.7% in Gallotia, 4.9% in Tarentola and 3.3% in Chalcides). Given their high host-specificity, geographical distribution and phylogeny, we concluded that these parasites colonized and probably co-diversified with their lizard hosts. Moreover, the data also suggested the biological distinctiveness of these haplogroups. To ensure that such haplogroups correspond to separate evolutionary entities here we use an integrative approach based on genetics, morphology, host range, geographic distribution, frequency of occurrence, parasitaemia and effect on host erythrocytes. We also sequence a longer fragment of the 18S rRNA to provide additional diagnostic characters, which is the only genetic marker available for these haemogregarines (Modrý et al., Reference Modrý, Beck, Hrazdilová and Baneth2017; Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). Finally, with all these lines of evidence gathered, we describe the Canarian haemogregarines as seven new species.

Fig. 1. Map of the study area and distribution of the seven haemogregarines infecting the Canarian lizards (as identified by Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). Different shapes correspond to the three host genera infected, while different colours correspond to the seven haemogregarine haplogroups and species here described, all of the genus Karyolysus. Additionally, for Gallotia, the circle is also a pie chart expressing the proportion of haplogroups from sequenced samples. The asterisks signal the type-localities of the haemogregarine their colour corresponds to. Lastly, the arrow on the world map indicates the location of the Canary Islands.

Materials and methods

In a previous paper, we screened the blood slides of 825 individuals from non-threatened lizard species of the Canary Islands for the presence of haemogregarines. Hosts belonged to four species of Gallotia lacertids (406 individuals), four species of Tarentola geckoes (266), and three species of Chalcides skinks (153). Samples were collected from 46 locations across the seven main islands of the archipelago, and in 27 of them more than one lizard genus occurred in sympatry. Full details on collection, slide screening and parasite genetic characterization can be found in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). We analysed only sequenced samples from this previous work (with single infections) to explore further differences among the seven haplogroups identified in parasitaemia levels, gametocyte morphology and the deformation caused on infected erythrocytes. Prior to analysis variables were tested for normality and homoscedasticity and transformed logarithmically. All statistical analyses were conducted in R v3.4.3 (R Core Team, 2017).

Resequencing of the 18S rRNA

To genetically characterize the Canarian Haemogregarines, Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018) used the pair of primers HepF300 and HepR900 (Ujvari et al., Reference Ujvari, Madsen and Olsson2004) to amplify a 600 bp fragment of the 18S rRNA. In the current work we tested two other primers, which combined with the previous pair produced an amplicon of around 1700 bp, the majority of the 18S rRNA (Netherlands et al., Reference Netherlands, Cook, Du Preez, Vanhove, Brendonck and Smit2018). The set of primers HAMF (Criado-Fornelio et al., Reference Criado-Fornelio, Ruas, Casado, Farias, Soares, Müller, Brumt, Berne, Buling-Saraña and Barba-Carretero2006) and HepF300 produced a 900 bp fragment, providing 300 extra bases to the 5′ end of the 600 bp fragment previously obtained, while 2868 (Medlin et al., Reference Medlin, Elwood, Stickel and Sogin1988) and HepR900 amplified a 1400 bp product, adding 800 bp to the 3′ end of the previous fragment. In total, we selected 28 representatives of the seven haemogregarine haplogroups to determine the genetic variation within the longer 18S rRNA fragment. For each haplotype, two haemogregarines per island where it occurred were sequenced, except for haplotypes B2 (from La Palma and Tenerife), D1 from Tenerife and D2 in which only one sequence of each could be obtained due to the reduced number of infected samples available.

Polymerase chain reaction conditions were similar to those used for the HepF300 and HepR900 primers, with adjustments to the annealing temperature (57 °C for the first set of primers, and 58 °C to the second) and the extension time (1 min, and 1 min and 30 s, respectively). The amplified products were purified and sequenced by an external company (Genewiz, UK). The retrieved sequences were first compared with the GenBank database, and then aligned with the corresponding previously obtained 600 bp fragment to confirm they were identical. Representatives of each haplotype were selected and aligned using the MAFFT algorithm (Katoh and Standley, Reference Katoh and Standley2013). The produced 1698 bp alignment was used to calculate the number of nucleotide differences and the uncorrected pairwise distances (p-distances) between haplotypes in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016). A phylogenetic network was also produced using the statistical parsimony approach implemented in TCS (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Posada and Crandall2000) and displayed graphically using tcsBU (Múrias Dos Santos et al., Reference Múrias Dos Santos, Cabezas, Tavares, Xavier and Branco2015). Phylogenetic trees were not constructed given the limited comparative genetic data available. The ten new sequences were uploaded to GenBank: nine were submitted as updates to the existing 18S rRNA haplotypes from the previous papers (KU680457.2 and MG787243.2–MG787251.2, to be updated upon manuscript acceptance), while the new haplotype (B3) was submitted as a new sequence (MK396906).

Gametocyte morphology

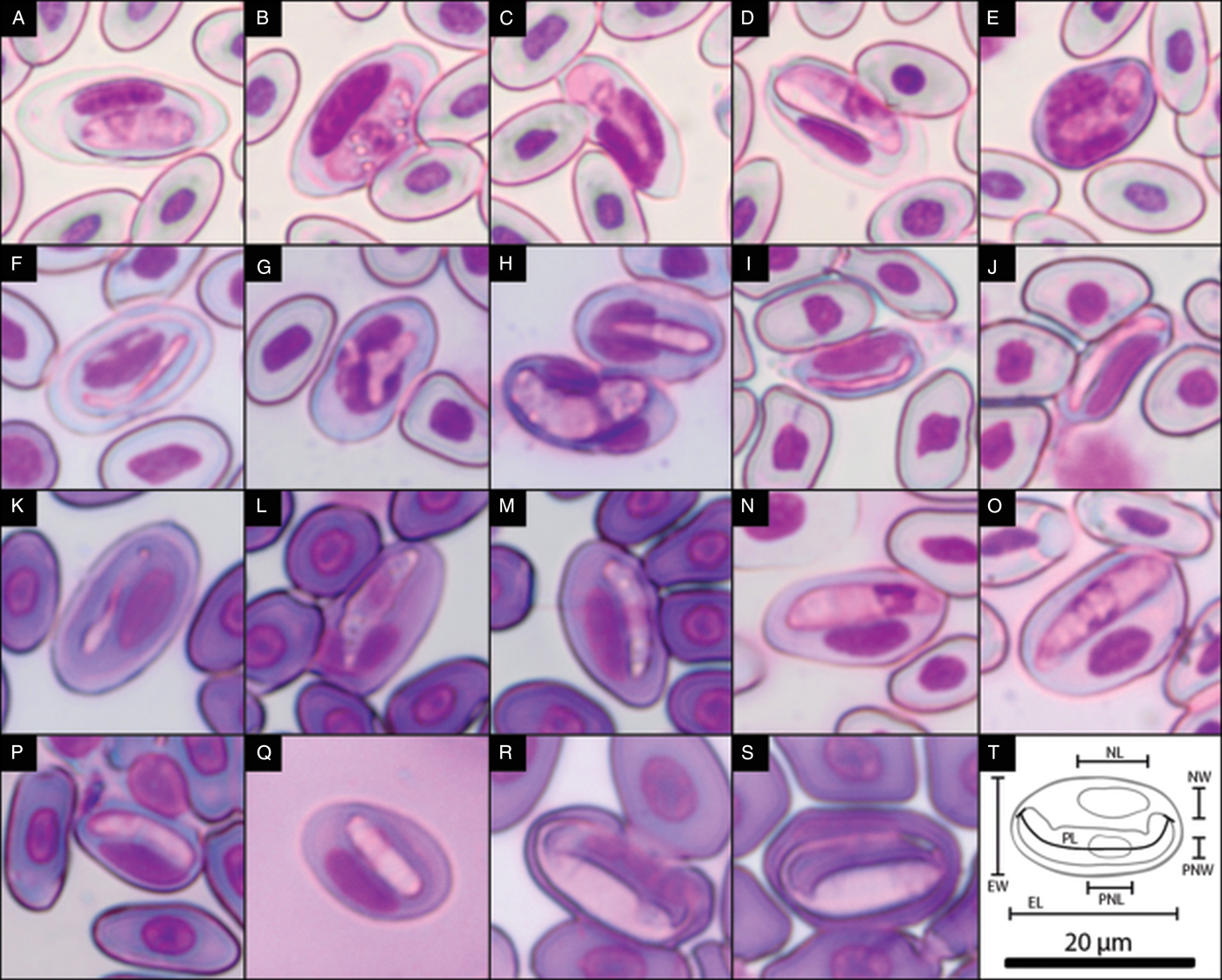

For the morphological analysis, 50 gametocytes of each haemogregarine haplogroup were randomly selected from five host individuals, ideally from the same location (the type-locality). However, this was not always possible due to the quality of the slides and the limited number of infected hosts (further details are available in the species description section of the Discussion). In these cases, 50 gametocytes were counted among the slides available. Photographs were taken at 1000× magnification under an Olympus CX41 microscope with an in-built digital camera (SC30; Olympus, Hamburg, Germany), using cell^B software (Olympus, Münster, Germany) (e.g. Fig. 2A, F, I–K and N–S). Measurements were then performed in ImageJ v. 1.50b software (Abràmoff et al., Reference Abràmoff, Magalhães and Ram2004). The features measured were length, width, area and perimeter of the gametocyte cells and of their nuclei (Fig. 2T). Additionally, the perimeter/area ratio was also calculated to assess differences in shape complexity (i.e. a higher ratio indicates a narrower form, while a lower ratio indicates a rounder shape). In some cases, the parasite nucleus was not well defined, specifically all individuals from haplogroup T and 18% of the parasites measured from the remaining haplogroups. Therefore, statistical analyses were performed on two datasets: one with all seven haplogroups but excluding nucleus measurements, and another including all measurements but excluding haplogroup T. In order to obtain a general indication regarding haemogregarine morphological variation without a priori information on the haplogroups, we ran a Principal Component Analysis (PCA, function prcomp; Venables and Ripley, Reference Venables, Ripley, Venables and Ripley2002). Then, we ran permutational Multivariate Analyses of Variance (permMANOVA, function adonis, package vegan, with 999 permutations; Anderson, Reference Anderson2001), and permutational pairwise contrasts (function pairwiseAdonis; Arbizu, Reference Arbizu2017) to investigate differences among haplogroups at a multivariate level. Additionally, we tested each variable individually using permutational analyses of variance (permANOVA, function aovp, lmPerm package; Wheeler and Torchiano, Reference Wheeler and Torchiano2016) and a-posteriori pairwise contrasts (function pairwisePermutationTest, package rcompanion; Mangiafico, Reference Mangiafico2018). Pairwise contrasts were corrected for multiple statistical testing using the Bonferroni correction.

Fig. 2. Photographs of the blood stages of the seven Canarian haemogregarines. (A) Gametocyte of haplotype A, (B–D) other developmental stages of haplogroup A, (E) gametocyte of haplotype A infecting a leukocyte, (F) gametocyte of haplogroup B, (G and H) other developmental stages of haplogroup B, (I and J) gametocytes of haplogroup C, (K) gametocyte of haplogroup D, (L and M) other developmental stages of haplogroup D, (N and O) gametocytes of haplogroup E, (P and Q) gametocytes of haplogroup F, (R and S) gametocytes of haplogroup T and (T) schematics of the measurements taken to assess the morphological differences between haplogroups (length and width of the parasite gametocyte (PL and PW, respectively) and its nucleus (PNL and PNW), and of the erythrocyte (EL and EW) and its nucleus (NL, NW). Also measured were the area and perimeter of the parasite and erythrocyte and their nuclei.). The scale bar applies to all photographs.

Gametocyte effect on erythrocyte morphology

To determine whether parasites provoke distortions to the host cells, we measured the length, width, perimeter and area of 50 infected and 50 randomly chosen uninfected mature erythrocytes and their respective nuclei. Given that the three host groups have different erythrocyte size and shape (results not shown), we could not perform direct comparisons of the level of distortion between haplogroups. For this reason, we compared differences in the morphology between infected and non-infected erythrocytes separately within each haplogroup, using permutational multivariate and univariate contrasts (with the same functions described above). Additionally, we calculated the percentage of difference in area of the host erythrocytes and their nuclei to describe the level of distortion provoked by each haplogroup.

Parasitaemia assessment

We estimated parasitaemia levels as the percentage of haemogregarine-infected erythrocytes per 2500 erythrocytes (Amo et al., Reference Amo, López and Martín2005; Maia et al., Reference Maia, Perera and Harris2012; Damas-Moreira et al., Reference Damas-Moreira, Harris, Rosado, Tavares, Maia, Salvi and Perera2014). Blood smears were photographed at 400× magnification again using cell^B software. Counts were performed using the Cell Counter plugin from software ImageJ v. 1.50b. For more details, see Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). To determine whether parasitaemia values differed among haemogregarine haplogroups, we performed permANOVAs (function aovp, R package lmPerm, with 5000 permutations) and permutational pairwise a-posteriori contrasts to know which haplogroups were different (function pairwisePermutationTest, R package rcompanion).

Results

Genetic diversity based on the longer 18S rRNA fragment

The additional 1100 bp of the 18S rRNA retrieved similar diversity as reported in the previous paper (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). The haplotype network shows ten haemogregarine haplotypes (Fig. 3A). However, in addition to the nine haplotypes previously reported, it also uncovered an additional haplotype in El Hierro. This new haplotype, named B3, is closely related to haplotypes B1 and B2 (Fig. 3A), with the central region of the 18S rRNA being identical to the former, where most of the variation occurs, and published in the previous study (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). Among the ten detected haplotypes, there was a total of 90 variable sites in the 1698 bp alignment (31.1% of which occurred in the first 301 bp, 45.6% in the central 569 bp, and 23.3% in the remaining 825 bp). The highest p-distance values were between haplotype T and the other nine haplotypes (ranging from 0.037 to 0.040, Table S1). Within these, haplotype A is the most divergent (0.012–0.017) from haplotypes B1-F. The most similar haplotypes were B1 and B2 (0.001), and D1 and D2 (0.001). See Table S1 for all p-distances and the number of nucleotide differences.

Fig. 3. Genetic and morphological differences of the seven haemogregarine haplotypes of the Canary Islands. (A) Phylogenetic network of the haemogregarine haplotypes infecting lizards of the Canary Islands using a 1698 bp alignment of the 18S rRNA. Black nodes represent mutations, while coloured ones correspond to the sequences of Canarian haemogregarines. (B and C) PCA scatterplot of the measurements taken from gametocytes of the seven haemogregarines. Colours correspond to each haemogregarine haplogroup (as identified in the network), and ellipses are the 95% confidence intervals. The analysis was performed on two datasets: all haplogroups not including nucleus measurements (B) and all measurements but excluding haplogroup T (C).

Parasite morphology

The seven parasite haplogroups differed in their gametocyte morphology (see Fig. 2 for photographs and Table S2 for more details on measurements). The PCA showed variation in parasite morphology across the multivariate space, with a partial clustering congruent with the molecular data (Fig. 3B and C). Notably, regarding infections in Gallotia spp., the haplogroups found in sympatry (haplogroups A and E, and haplogroups B and D) did not overlap in the multivariate space (see Fig. 3C), when all measurements were included. For the dataset excluding the measurements of the nucleus, the first component of the PCA accounted for 68.3% of the total variation and was mainly driven by the area and width of the parasite cell, while the second component, which represented 30.1% of the total variance, was driven instead by the cell length and perimeter (Table S3). When all parasite cell and nucleus measurements were included (but excluding haplogroup T), the first component of the PCA (65.9% of the total variation) was mostly driven by measurements of the nucleus, along with cell width, area and perimeter/area ratio. Similarly to the other dataset, cell length and perimeter were again the most important factors driving variation for the second component (20.8% of the total variation) (Table S3). The permMANOVA confirmed the morphological differences among genetic entities for the two datasets (excluding parasite nucleus: df = 6, SS = 28.117, F = 303.49, P < 0.001, all pairwise comparisons P < 0.05; and including nucleus measurements: df = 5, SS = 63.802, F = 247.28, P < 0.001, all pairwise comparisons P < 0.05). The differences were also significant for individual ANOVAs of all measurements for both datasets (P < 0.001, Table S4).

Erythrocyte distortion

For all the genetic entities analysed, gametocytes provoked distortion in the infected erythrocytes, both in size and shape of the host cell and its nucleus (P = 0.001 in all cases, see Fig. 2A–S for photos, Table S5 for measurements and Table S6 for statistical results). In general, infected erythrocytes increased in area and became rounder (Table S6). This happened for all haplogroups except for C, for which erythrocytes also increased in length, but became narrower instead, not having a significant variation in their area. The cell nucleus was also affected, increasing in length for all haplogroups and decreasing in width for most (likely due to the displacement of the nucleus to the side by the parasite). The exceptions were haplogroups E and F, for which the width of host erythrocyte's nucleus was not significantly altered. The haemogregarines also differed in the level of distortion of the host erythrocyte (Table S5). For instance, haplogroup C was the one that provoked the least distortion to erythrocytes’ area (6% increase), but the most to their nuclei (87%). On the other hand, haplogroups E and F provoked the greatest erythrocyte area increase (74%), but less regarding respective nuclei areas (58 and 55%).

Parasitaemia

The seven haplogroups presented differences in their parasitaemia values (df = 6, SS = 15.878, P < 0.001, Fig. 4), although not always significant for the pairwise comparisons (Table S7). Haplogroups T (which infects geckos) and F (which infects skinks) presented respectively the highest (1.42%) and lowest (0.07%) mean parasitaemia values, while for the haplogroups infecting Gallotia (haplogroups A to E), values ranged from 1.15% (for A) to 0.13% (for E). It should however be noted that sample size was quite disparate between haplogroups (e.g. 44 infected individuals for haplogroup B, and only three for haplogroups E and F). Infections by haplogroup B in two Chalcides and Tarentola individuals were also measured. Parasitaemia values were 0.02 and 0.04%, respectively, while in the genus Gallotia the mean value was 1.38%.

Fig. 4. Boxplots of the parasitaemia values for the seven haemogregarines, per genus of lizard hosts. The vertical axis is in logarithmic scale and black dots represent the mean values. Imposed are scatterplots of the individual data points (with a slight adjustment for better visualization), where colours correspond to the haemogregarine haplogroups as identified in the horizontal axis.

Discussion

New genetic data and taxonomical placement

In a previous work, we identified seven different entities infecting the lizards of the Canary Islands, with distinct genetic composition, frequency of occurrence, geographical distribution and host ranges (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). In the current study, we corroborate their distinctiveness based on gametocyte morphology, effect on host erythrocyte and parasitaemia levels. Additionally, we sequenced a longer fragment of the 18S rRNA and uncovered a new haplotype. This new haplotype shares the same central region of the 18S rRNA with haplotype B1 (and one nucleotide difference with B2) and, as such, we consider it within haplogroup B. This new haplotype B3 represents a further example of the diversity of these haemogregarines, and possible divergence by isolation among islands and/or host species. According to the current data, the sister haplotypes B1 and B2 occur in Gallotia galloti (Oudart, 1839) from Tenerife and La Palma, while haplotype B3 infects Gallotia caesaris Lehrs, 1914 from El Hierro. Except for this discovery, the results from the phylogenetic network and p-distance analyses were congruent with the previous study, as the same groups of haplotypes were uncovered. The minimum p-distance between haplogroups was 0.003 (haplogroups E and F), which despite being a small value, is notable given that the 18S rRNA is a slow-evolving gene. In fact, a difference of one or two base pairs in this gene has been used in the past as a threshold for species description (O'Dwyer et al., Reference O'Dwyer, Moço, Paduan, Spenassatto, da Silva and Ribolla2013). Nonetheless, we chose not to consider genetic distances as a species discrimination feature on its own, but rather when supported by multiple additional evidence.

Recently, Karadjian et al. (Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015) proposed a new classification for the terrestrial haemogregarines into four genera, based on phylogenetic analyses and life history traits: Hepatozoon Miller, 1908; Karyolysus Labbé, 1894; Hemolivia Petit, Landau, Baccam and Lainson, 1990; and the newly created Bartazoon Karadjian et al., Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015. However, Maia et al. (Reference Maia, Carranza and Harris2016a) considered this reassignment as premature given that data and sampling are still limited, such that the monophyly of some of these groups is still in doubt (Haklová-Kočíková et al., Reference Haklová-Kočíková, Hižňanová, Majláth, Račka, Harris, Földvári, Tryjanowski, Kokošová, Malčeková and Majláthová2014; Kvičerová et al., Reference Kvičerová, Hypša, Dvořáková, Mikulíček, Jandzik, Gardner, Javanbakht, Tiar and Široký2014). The haemogregarines infecting Canarian lizards cluster within the ‘Karyolysus’ clade (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018), although haplogroup T is part of a distinct haemogregarine lineage relative to the remaining Canarian haplogroups. This lineage is only known from gecko hosts (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Harris, Carranza and Goméz-Díaz2016b; Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Rato, Perera and Harris2016) and, while closely related to Karyolysus, it remains unclear if it should be placed in this genus, as has been suggested (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2016). Described species of the genus Karyolysus infect acarines and lizards as definitive and intermediate hosts, respectively (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Telford, Reference Telford2009). Currently only 11 species of Karyolysus are recognized (Svahn, Reference Svahn1975; Smith, Reference Smith1996; Van As et al., Reference Van As, Davies and Smit2013; Haklová-Kočíková et al., Reference Haklová-Kočíková, Hižňanová, Majláth, Račka, Harris, Földvári, Tryjanowski, Kokošová, Malčeková and Majláthová2014), including the recently reassigned Karyolysus paradoxa (Dias, 1954) (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2016). This is a low number given that this group of parasites is widespread, genetically diverse and infects several groups of reptiles, namely lacertids, skinks, varanids, snakes and possibly geckos (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Carranza and Harris2016a). The genus gets its name from the severe distortion, sometimes along with lysis, of the nucleus of the erythrocyte caused by the parasite gametocyte (Telford, Reference Telford2009). Our results show that the Canarian haemogregarines distort the erythrocyte cell, with the nucleus being often enlarged and rarely fragmented. Another study has also reported this deformation of erythrocytes by haemogregarines infecting Gallotia bravoana Hutterer, 1985, leading the authors to presume the parasites were of the genus Karyolysus (Martínez-Silvestre et al., Reference Martínez-Silvestre, Mateo, Silveira and Bannert2001). In light of the present results (namely, their phylogenetic relationships, effect on the host erythrocyte and host associations), we consider that the haemogregarines infecting lizards of the Canary Islands do belong to the genus Karyolysus.

Comparison with other studies

The presence of different forms of haemogregarines infecting Gallotia was already suggested in the past (Bannert et al., Reference Bannert, Lux and Sedlaczek1995), and our study further confirms this. In their descriptive study, Bannert et al. (Reference Bannert, Lux and Sedlaczek1995) identified eight morphotypes but did not give a generic designation. Their observations are mostly congruent with our results in terms of gametocyte shape, host species and location, though their measurements differ from ours. This disparity might be due to the inclusion of different stages or co-infections, differences in blood slide preparation (Hassl, Reference Hassl2012), and/or instrumental bias. Although the forms seem to correspond to our haplogroups, only the combination of molecular tools, for the identification of the development stages, with morphology, biogeography and infection data provided a refined identification and characterization.

To our knowledge, no haemogregarine species has been previously described from any of the Canarian lizard species or from the archipelago itself. In Europe and North Africa, several haemogregarine species have been reported in various reptiles, including Tarentola, Chalcides and Psammodromus Fitzinger, 1826 (Saoud et al., Reference Saoud, Ramadan, Mohammed and Fawzi1995; Smith, Reference Smith1996; Van As et al., Reference Van As, Davies and Smit2013; Rabie and Hussein, Reference Rabie and Hussein2014; and references within), all closely related to the Canarian lizards. Most of these parasites have been placed within the genera Hepatozoon or Haemogregarina Danilewsky, 1885, given the low disruption of the infected erythrocyte, among other characteristics. Indeed, the Canarian haemogregarines are genetically different from those detected to date in closely related host groups (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Harris and Perera2011, Reference Maia, Perera and Harris2012; Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Rato, Perera and Harris2016, Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). This is not surprising giving that lizard hosts colonized the archipelago several million years ago, where they subsequently speciated (Carranza et al., Reference Carranza, Arnold, Mateo and Geniez2002, Reference Carranza, Arnold, Geniez, Roca and Mateo2008; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Carranza and Brown2010). Thus, we consider that the Canarian haemogregarines as distinct entities representing further examples of the endemic diversity within the Canary Islands, already notorious in other groups (Juan et al., Reference Juan, Emerson, Oromí and Hewitt2000; Sanmartín et al., Reference Sanmartín, Van Der Mark and Ronquist2008; Illera et al., Reference Illera, Spurgin, Rodriguez-Exposito, Nogales and Rando2016).

Description of the new species

In light of the combined evidence (which includes molecular data, distribution, host-specificity, gametocyte morphology and effect on host erythrocytes), we describe as species the seven distinct entities that infect the lizards of the Canary Islands. Table 1 presents a summarized version of these descriptions. Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of the haplogroups and location of the type localities, Fig. 2 contains photos of the life stages in the lizard blood, Fig. 4 shows variation in parasitaemia, Table S2 contains the measurements taken from the gametocytes and Table S5 shows the measurements of infected and non-infected erythrocytes. The referred cases of cross infections between host groups and of co-infections of different haplotypes within the same host individual were identified genetically. For further information, including additional locality information, haplogroup frequency and phylogenetic relationships, refer to Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). All specific epithets are masculine.

Table 1. Summary descriptions of the seven new haemogregarine species infecting lizards of the Canary Islands

Phylum: Apicomplexa Levine, 1970

Class: Conoidasida Levine, 1988

Order: Eucoccidiorida Léger & Duboscq, 1910

Suborder: Adeleorina Léger, 1911

Family: Karyolysidae Wenyon, 1926

Genus: Karyolysus Labbé, 1894

Karyolysus canariensis n. sp.

Type-host: Gallotia atlantica.

Other hosts: Tarentola angustimentalis Steindachner, 1891 (detected by Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Rato, Perera and Harris2016), likely an occasional cross-infection).

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: Nazaret-Teguise, Lanzarote (29°02′47″N, 13°33′43″W).

Other localities: Widespread in the easternmost islands of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura.

Type-material: Hapantotype, one blood smear of a G. atlantica individual from the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343345.

Representative DNA sequences: This species is represented by a single haplotype, haplotype A, for the 18S rRNA gene. A 1698 bp sequence of this gene is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787243.2 [isolated from the type-host G. atlantica by Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018)]. Additionally, a sequence isolated from the cross-infected T. angustimentalis (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Rato, Perera and Harris2016) is also available under the accession number KU680457.2.

Etymology: Named after the Canary Islands archipelago, as it was the first haemogregarine species genetically characterized from this geographical region.

Description: Mature gametocyte: oval in shape with round edges; it can be slightly curved in the middle; cytoplasm has a cloudy appearance, staining pink to purple; nucleus central to distal, sometimes not clearly visible (Fig. 2A); mean cell measurements = 12.12 × 4.19 µm, mean nucleus measurements = 3.35 × 3.12 µm (n = 50, from five host individuals from the type-host species and type-locality). Effects on host cell: encapsulated by a large membrane that includes the erythrocyte nucleus; erythrocyte clearly affected, much larger in size, cell membrane looks thinner and many times is ruptured; nucleus is also larger, distorted and displaced to the side, and frequently fragmented into two. Other stages commonly found (Fig. 2B–D). Found on rare occasions infecting lymphocytes (Fig. 2E).

Remarks: Originally referred to as haplogroup A by Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). It has been found in ten of the 11 (91%) locations sampled for Gallotia lizards in Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. It presents a mean parasitaemia of 1.15 ± 1.52% (mean ± standard deviation), ranging between 0.04 and 7.28% (n = 27). It can be found co-infecting the same host individual together with haplogroup E (described below as Karyolysus atlanticus). Although both haemogregarines co-exist in the same islands, K. canariensis is more common.

Karyolysus galloti n. sp.

Type-host: Gallotia galloti.

Other hosts: Also found infecting G. caesaris from El Hierro, although in lower prevalence. Additionally, occasional cross-infections were detected in a Chalcides coeruleopunctatus Salvador, 1975 individual from El Hierro, and in a Tarentola delalandii (Duméril and Bibron, 1836) individual from Tenerife.

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: Erjos, Tenerife (location 18: 28°19′40″N, 16°48′13″W).

Other localities: Highly prevalent across the western islands of La Palma and Tenerife, not so commonly found in El Hierro.

Type-material: Hapantotype, one blood smear from a G. galloti host from the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343346.

Representative DNA sequences: This species includes three haplotypes (B1, B2 and B3) for the 18S rRNA gene. Sequences are 1698 bp long isolated from the type-host G. galloti. The most prevalent haplotype, B1, is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787244.2, haplotype B2 under MG787245.2, and haplotype B3 under MK396906.

Etymology: Named after the specific epithet and the genus of the type-host species.

Description: Mature gametocyte: filiform, curved or bent on one of the edges; clear cytoplasm that stains light pink; very small nucleus central or slightly towards one of the edges (Fig. 2F); mean cell measurements = 16.89 × 2.68 µm, mean nucleus measurements = 2.96 × 1.00 µm (n = 50, from four individuals of the type-host species and type-locality). Host erythrocyte affected, larger in size, cell membrane looks thinner and is sometimes ruptured, occasionally seen encapsulated by a large membrane that includes the erythrocyte nucleus. The nucleus of the host erythrocyte is larger and displaced to the side, but not fragmented. Other stages are identifiable (Fig. 2G and H).

Remarks: Originally reported as haplogroup B in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). It has been found in 14 out of the 16 (88%) locations sampled for Gallotia lizards in El Hierro, La Palma and Tenerife. In the two latter islands, it has been found in more locations than the co-occurring haplogroup D (described below as Karyolysus gomerensis), which in turn is more frequent in El Hierro. Co-infections with both these haemogregarine species have been detected (in eight of 16 localities sampled for Gallotia individuals). Karyolysus galloti has a mean parasitaemia in the genus Gallotia of 1.38 ± 3.58%, ranging between 0.02 and 24.64% (n = 48).

Karyolysus stehlini n. sp.

Type-host: Gallotia stehlini.

Other hosts: None known to date.

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: Aldea Blanca, Gran Canaria (27°50′23″N, 15°28′43″W).

Other localities: Two other localities in the central island of Gran Canaria.

Type-material: Hapantotype, one blood smear from a G. stehlini host of the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343349.

Representative DNA sequence: This species is represented by a single haplotype, haplotype C, for the 18S rRNA gene. A 1698 bp sequence of this gene is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787246.2.

Etymology: Named after the specific epithet of the type-host species, which in turn was named after Hans Georg Stehlin, a palaeontologist and geologist who collected the lizard holotype.

Description: Mature gametocyte: filiform; curved in the middle; clear light pink cytoplasm; nucleus is normally placed centrally, small and sometimes not visible (Fig. 2I and J); mean cell measurements = 13.52 × 1.84 µm, mean nucleus measurements = 3.81 × 1.28 µm (n = 50, from four individuals of the type-host species and type-locality). Infected erythrocyte not much larger, but generally longer and slightly narrower, cytoplasm looks darker, and cell membrane is almost always ruptured. The nucleus of the host erythrocyte is larger and displaced to the side, never fragmented. No other stages were identified.

Remarks: Originally referred as haplogroup C in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). It has been found in three out of seven (42.9%) locations sampled for Gallotia lizards in Gran Canaria. It presents a mean parasitaemia of 0.31 ± 0.51%, ranging between 0.02 and 1.40% (n = 7).

Karyolysus gomerensis n. sp.

Type-host: Gallotia caesaris.

Other hosts: Gallotia galloti.

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: South of Parque Majona, La Gomera (28°07′32″N, 17°09′43″W).

Other localities: Across the western islands, although less common in Tenerife and La Palma than in La Gomera and El Hierro.

Type-material: Hapantotype, one blood smear of a G. caesaris adult host from the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343347.

Representative DNA sequences: This species presents two sister haplotypes for the 18S rRNA gene, both sequences are 1698 bp long. Haplotype D1 is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787247.2, isolated from a G. caesaris host. Haplotype D2 was only found in one instance in La Palma and corresponds to the GenBank code MG787248.2, isolated from a G. galloti host.

Etymology: Named after the island where the type locality is situated.

Description: Mature gametocyte: filiform to oval; slightly curved in the middle; granulated light pink cytoplasm; central nucleus (Fig. 2K); mean cell measurements = 13.42 × 2.76 µm, mean nucleus measurements = 3.69 × 1.79 µm (n = 50, from five individuals of the type-host species and type-locality). Sometimes seem encapsulated by a large membrane that includes the erythrocyte nucleus. Host erythrocyte affected, larger and rounder, cell membrane thinner but not ruptured. The nucleus of the host erythrocyte is larger, appears more granulated, is displaced to the side, and occasionally divided in two connected fragments. Other stages observed (Fig. 2L and M).

Remarks: Originally referred to as haplogroup D in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). Found in 13 of the 21 (61.9%) locations sampled for Gallotia lizards in El Hierro, La Gomera, La Palma and Tenerife. It is less frequent than K. galloti in Tenerife and La Palma, while in El Hierro it is most frequent, and it is the only haemogregarine detected in La Gomera. This species and K. galloti can be found co-infecting the same host individuals. Karyolysus gomerensis has a mean parasitaemia of 1.16 ± 0.15%, ranging between 0.02–0.56% (n = 31).

Karyolysus atlanticus n. sp.

Type-host: Gallotia atlantica.

Other hosts: None known to date.

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: Yé, Lanzarote (29°11′52″N, 13°29′02″W).

Other localities: Present in several locations of the easternmost islands of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote.

Type-material: Hapantotype, one blood smear from a G. atlantica individual of the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343344.

Representative DNA sequence: This species presents only one haplotype, haplotype E, for the 18S rRNA gene. A 1698 bp sequence of this gene is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787249.2.

Etymology: Named after the specific epithet of the type host species.

Description: Mature gametocyte: oval with a pointy proximal end and a more round distal end; can be slightly curved and sometimes bent in the proximal end; cytoplasm is granular, staining in different pink tones; nucleus is proximal to distal (Fig. 2N and O); mean cell measurements = 17.41 × 4.68 µm, mean nucleus measurements 4.96 × 4.24 µm (n = 50, from two individuals of the type-host species from two locations). Host erythrocyte much larger in size, with a darker cytoplasm, cell membrane looks just a bit thinner and is never ruptured. The nucleus of the host erythrocyte is not much larger, is displaced to the side and is not fragmented. No other stages identified.

Remarks: Originally referred as haplogroup E in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). It has been found in seven of the 11 (63.6%) locations where Gallotia lizards were sampled in Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. It presents a mean parasitaemia of 1.33 ± 0.16%, ranging between 0.04 and 0.32% (n = 3). It is less common than the sympatric K. canariensis (haplogroup A), being frequently found in co-infections (only three host individuals found with single infections).

Karyolysus tinerfensis n. sp.

Type-host: Chalcides viridanus (Gravenhorst, 1851).

Other hosts: None known to date.

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: Mesa del Mar, Tenerife (28°30′02″N, 16°25′12″W).

Other localities: None known to date.

Type-material: Hapantotype: one blood smear of a C. viridanus host individual from the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343350.

Representative DNA sequence: This species presents only one haplotype, haplotype F, for the 18S rRNA gene. A 1698 bp sequence of this gene is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787250.2.

Etymology: Named after the legendary Guanche mencey (tribal king) Tinerfe, for whom the island of Tenerife, which includes the type locality, gets its name.

Description: Mature gametocyte: oval shape with round edges; can be slightly curved; cloudy cytoplasm in pink to purple tones; nucleus proximal to distal, many times not clearly visible (Fig. 2P and Q); mean cell measurements = 12.53 × 3.38 µm, mean nucleus measurements 3.74 × 2.94 µm (n = 50, from three individuals of the type-host species and type-locality). Host erythrocyte very enlarged and rounder, cytoplasm looks lighter, cell membrane is occasionally thinner but not ruptured. The nucleus of the host erythrocyte is larger, displaced to the side, not fragmented. No other stages identified.

Remarks: Originally referred to as haplogroup F in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). Very low prevalence (only found in three host individuals from 153 skinks sampled in the archipelago). It has a mean parasitaemia of 0.07 ± 0.08%, ranging between 0.02 and 0.16% (n = 3).

Karyolysus makariogeckonis n. sp.

Type-host: Tarentola delalandii.

Other hosts: Tarentola gomerensis Joger & Bischoff, 1983.

Vector: Unknown.

Type-locality: Piedra Alta, La Palma (28°43′60″N, 17°43′47″W).

Other localities: Only found in two other sites in La Gomera.

Type-material: Hapantotype: one blood smear of a T. delalandii individual from the type locality, deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States of America, under the barcode number AMNH_IZC_00343348.

Representative DNA sequences: This species presents only one haplotype, haplotype T, for the 18S rRNA gene. A 1698 bp sequence of this gene is deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession number MG787251.2.

Etymology: Named after the subgenus of the host species, which in turn is named after the Macaronesia island system (that includes the Canary Islands).

Description: Mature gametocyte: shape is fusiform with elongated tapered edges, frequently surrounding the erythrocyte's nucleus; cytoplasm has a cloudy appearance, staining light pink; the nucleus is not visible (Fig. 2R and S); mean cell measurements = 12.54 × 4.80 µm (n = 50, from five individuals of the type-host species and type-locality). Host erythrocyte slightly enlarged, cell membrane not affected. The nucleus of the host erythrocyte is longer, thinner and displaced to the side, but not fragmented. No other stages identified.

Remarks: Originally referred to as haplogroup T in Tomé et al. (Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). It presents a mean parasitaemia of 1.42 ± 1.63%, ranging between 0.04 and 4.36% (n = 6).

Identification of the invertebrate hosts

Unfortunately, some information concerning the haemogregarines here described is still missing, most notably the identity of their definitive invertebrate hosts. Knowledge on the invertebrate hosts is crucial to better understand the transmission, host-specificity and dispersal of these parasites. Haemogregarines have a heteroxenous lifecycle, during which the vertebrate host (where merogony takes place) becomes infected by ingestion of the parasitized invertebrate (where syngamy and sporogony occur) (Telford, Reference Telford2009). For Karyolysus species, mites are the suspected invertebrate host, specifically mites of the genus Ophionyssus Mégnin, 1883 (Svahn, Reference Svahn1975; Telford, Reference Telford2009; Haklová-Kočíková et al., Reference Haklová-Kočíková, Hižňanová, Majláth, Račka, Harris, Földvári, Tryjanowski, Kokošová, Malčeková and Majláthová2014; and references within). Three species of Ophionyssus mites have been described parasitizing Gallotia spp. (Fain and Bannert, Reference Fain and Bannert2000, Reference Fain and Bannert2002): one from Lanzarote, another from Gran Canaria and the last from the four western islands. This distribution is congruent with the geographical distribution of the haemogregarines and the three main lineages of their Gallotia hosts (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Carranza and Brown2010). Furthermore, their role as vectors for haemogregarines has already been suggested (Bannert et al., Reference Bannert, Lux and Sedlaczek1995, Reference Bannert, Karaca and Wohltmann2000). Regarding the skinks, Ophionyssus spp. mites infect several species of these lizards around the world, but so far they have not been detected infecting Canarian skinks (Fain and Bannert, Reference Fain and Bannert2000), so we have no hypothesis regarding the possible identity of their invertebrate host. Finally, the genus Geckobia Mégnin, 1878, a mite specialist on geckos (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Pfliegler and Sciberras2012; Fajfer, Reference Fajfer2012), has two described species infecting the Canarian Tarentola spp. from the four western islands (Zapatero-Ramos et al., Reference Zapatero-Ramos, Gonzalez-Santiago, Solera-Puertas and Carvajal-Gallardo1989). There is no data suggesting the association of these mites with haemogregarines, but we consider them the primary suspect for definitive hosts of K. makariogeckonis (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Peirce, Heath, Brunton and Barraclough2011). In all cases, further studies are necessary to ascertain the role of mites in the lifecycle of the Canarian haemogregarines. Additionally, other invertebrates also need to be investigated, along with the use of alternative transmission pathways including via predation. This has been suggested for haemogregarines by both experimental (Sloboda et al., Reference Sloboda, Kamler, Bulantová, Votýpka and Modrý2008; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing and Little2009) and genetic studies (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Maia and Harris2013, Reference Tomé, Maia, Salvi, Brito, Carretero, Perera, Meimberg and Harris2014; Maia et al., Reference Maia, Álvares, Boratyński, Brito, Leite and Harris2014), and a demonstrated adaptation of species of Sarcocystis Lankester, 1882 infecting Canarian lizards (Matuschka and Bannert, Reference Matuschka and Bannert1987, Reference Matuschka and Bannert1989; Bannert, Reference Bannert1992).

Final remarks

Here, we integrated several sources of evidence to support the description of seven novel haemogregarine species. Accurate characterization of parasites is crucial for studies regarding parasite adaptation or effects on the host, some of which have been conducted on Canarian haemogregarines (Oppliger et al., Reference Oppliger, Vernet and Baez1999; García-Ramírez et al., Reference García-Ramírez, Delgado-García, Foronda-Rodríguez and Abreu-Acosta2005; Megía-Palma et al., Reference Megía-Palma, Martínez and Merino2016). Indeed, our results show differences between species regarding parasitaemia values and effect on the host erythrocyte, both important factors for the health of the host (Caudell et al., Reference Caudell, Whittier and Conover2002; Amo et al., Reference Amo, López and Martín2005; and references within). As such, we recommend genotyping at least a random subset of the samples or, if using microscopy, to look for morphological differences, which could alert to the presence of distinct haemogregarines. We also recommend the assessment of all potential hosts and parasite outgroups when studying host–parasite associations and describing new haemogregarine species. For instance, K. canariensis was first reported infecting geckos (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Rato, Perera and Harris2016), but after a detailed screening we found that the previous report is most probably a cross-infection, with this haemogregarine actually being almost exclusively found in Gallotia lizards (Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Pereira, Jorge, Carretero, Harris and Perera2018). Lastly, our descriptions constitute new contributions to the phylum Apicomplexa, for which it is estimated that only 0.1% of the species have been described (Morrison, Reference Morrison2009; Votýpka et al., Reference Votýpka, Modrý, Oborník, Šlapeta, Lukeš, Archibald, Simpson and Slamovits2017). Moreover, these endemic parasites infect hosts, who are endemic themselves and some are considered endangered species. The described haemogregarines can thus be relevant for conservation efforts, as they are part of the natural parasite communities inhabiting the Canarian herpetofauna. Deparasitations are routine procedures in conservation programmes, despite the poor understanding of their consequences and the known role of parasitism in host-fitness, ecosystem dynamics and biodiversity distribution (Prenter et al., Reference Prenter, MacNeil, Dick and Dunn2004; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Dobson and Lafferty2006; Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Dick and Dunn2012). Future work on these parasites should focus on sampling the endangered host species as well as the recently introduced reptiles in the Canary Islands, identifying the invertebrate vectors, and developing faster evolving markers to clarify their phylogeny and allow the assessment of evolutionary processes at finer scales.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182018002160

Author ORCIDs

Beatriz Tomé 0000-0003-3649-2759.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cabildos Insulares (Island Authorities) from Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera and El Hierro of Spain for the lizard collection permits; the Centro Insular para la Cría en Cautividad del lagarto gigante de La Gomera (Gallotia bravoana) and the Centro de Recuperación del Lagarto Gigante de El Hierro. Several other people helped develop this work, including M. López-Darias, B. Fariña, Z. Tobias, A. Martínez-Silvestre, A. Kaliontzopoulou, and a special thanks to Fátima Jorge for her valuable contribution. We also acknowledge Juan Carlos Illera for his comments on an early version of this manuscript, and an anonymous reviewer of a previous paper for suggesting the PCR primers used in this study. Lastly, we acknowledge the contribution of the anonymous reviewers, whose comments helped to improve this manuscript.

Financial support

BT is funded by a Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) PhD grant (PD/BD/52601/2014), and this study is part of her thesis dissertation. DJH and AP are funded through FCT contracts (IF/01257/2012 and IF/01627/2014) under the Programa Operacional Potencial Humano – Quadro de Referência Estratégico Nacional from the European Social Fund and Portuguese Ministério da Educação e Ciência. MAC is supported by project NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000007. This study was funded by the IF exploratory project IF01257/2012/CP0159/CT0005, and by PTDC/BIA-BDE/67678/2006 and PTDC/BIA-BEC/105327/2008 both by FCT and FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-007062 and FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-008970 COMPETE program, respectively.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Regarding ethical consideration on animal sampling and handling, all samples were collected under permits issued by the environmental authorities of the Canary Islands (Cabildos Insulares of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera and El Hierro), and of Morocco (Haut Commissariat aux Eaux et Forêts et à la Lutte contre la Désertification).