Lean management (“Lean”; also Lean strategy, Lean systems, Lean philosophy) has been adopted by thousands of businesses and organizations throughout the world. Universities offer academic majors and minors in Lean. Noncredit certification programs in Lean for employers are a thriving cottage industry for many universities and other organizations (e.g., Lean Enterprise Institute). The popularity of Lean has inspired an army of Lean consultants and trainers who work with companies to help implement Lean initiatives. There is a growing body of scholarship evaluating the impact of Lean on organizational effectiveness and factors that are thought to moderate or mediate the influence of Lean on organizational performance (e.g., Balzer, Francis, Krehbiel, & Shea, Reference Balzer, Francis, Krehbiel and Shea2016; Bhamu & Sangwan, Reference Bhamu and Sangwan2014; Jasti & Kodali, Reference Jasti and Kodali2015; Samuel, Found, & Williams, Reference Samuel, Found and Williams2015; Stone, Reference Stone2012). Yet despite the continued growth of Lean 30 years after it was first introduced to a worldwide audience (Krafcik, Reference Krafcik1988; Womack, Jones, & Roos, Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990), the industrial and occupational (I-O) psychology community has largely ignored the Lean research literature as well as ceded applied work in Lean to other organizational practitioners (Balzer, Smith, & Alexander, Reference Balzer, Smith and Alexander2009). This article reviews the development and growth of Lean and highlights research, practice, and consulting opportunities for the field of I-O psychology to contribute to this ubiquitous management and operations philosophy. Our hope is to motivate I-O psychologists to participate in the Lean research and practice domain, as well as to stimulate critical thinking on their roles with popular management trends. We believe that I-O psychology could gain influence by engaging in popular management trends, though in this article we concentrate on Lean because of our personal experience and because we believe Lean has been especially ignored by I-O psychologists. In I-O psychology, there has been much made about the scientist–practitioner gap, though in most cases the gap that is discussed is between I-O psychologists employed in academia versus I-O psychologists employed in private and public organizations (e.g., Anderson, Herriot, & Hodgkinson, Reference Anderson, Herriot and Hodgkinson2001). In this article, we discuss the gap between I-O academics and practitioners with Lean researchers and practitioners. As we will demonstrate, this gap is quite large.

What is Lean? As is common with other popular management paradigms, there is no single accepted definition of Lean (see Balzer et al., Reference Balzer, Smith and Alexander2009). In an analysis of a related management paradigm, total quality movement, Hackman and Wageman (Reference Hackman and Wageman1995) discussed this lack of precision: “As is inevitable for any idea that enjoys wide popularity in managerial and scholarly circles, total quality management (TQM) has come to mean different things to different people” (p. 310). Despite a lack of a single agreed-upon definition, common threads have been identified across various efforts to define Lean (e.g., Emiliani, Reference Emiliani2015; Liker, Reference Liker2004; Monden, Reference Monden1994; Shah & Ward, Reference Shah and Ward2007; Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2003; Womack et al., Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990):

Respect for people through the engagement and empowerment of employees and self-development of leaders

Pursuit of perfection through the reduction or elimination of all forms of waste to improve the flow of processes, services, and activities while consuming the fewest resources

Meet or exceed the expectations of the customer served by the process or activity while at the same time benefit the employees and organization

Analyze, change, and assess improvement using a formal and structured approach modeled after the scientific process

Leadership commitment to a long-term strategic and operational system

For the purposes of this article, Lean is defined as a comprehensive management system grounded in respect for people and ongoing continuous improvement to create mutual gains for the customer, employee, and organization through the application of widely accepted operational and problem-solving practices. Although there are many similarities with other process improvement systems (e.g., TQM and Six Sigma), we will distinguish Lean from these other systems in a later section.

As defined, Lean includes many areas of research and practice central to the field of I-O psychology: management practices, organizational culture, leadership, work design, training, teamwork, decision making, organizational effectiveness, work motivation, employee engagement, attitudes, organizational change and development, and assessment of organizational interventions. Although the fields of engineering, operations management, quality systems, and other related disciplines have contributed significantly to the business application of Lean, there is virtually no published research on Lean in mainstream I-O psychology journals. There is a dearth of evidence-based research by the field on the psychosocial aspects of Lean that would enrich the understanding of Lean, whether and why it works, and how best to implement it. Thus, this focal article hopes to inform and challenge our field to apply the scientist–practitioner model to the design, implementation, and evaluation of Lean.

This article begins with a brief history of Lean. Evidence will then be presented to show the broad application of Lean in businesses and organizations while also showing the limited role that I-O psychology has played in this development. After briefly speculating on why I-O psychology has had such a limited role in the development and application of Lean, we propose a number of key areas where I-O psychology can make major contributions to the understanding, application, and evaluation of Lean in the workplace. Finally, we conclude that ignoring Lean limits I-O psychology’s influence on one of corporate America’s farthest-ranging organizational interventions.

The development and implementation of Lean

A brief history of Lean

The term “Lean” was first introduced by Krafcik (Reference Krafcik1988) and then expanded upon in the seminal book by Womack, Jones, and Roos (Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990), The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production. This book followed a 5-year exploration of the differences between the large-scale, mass production approach of U.S. automobile manufacturers and the Japanese manufacturing approach demanding smaller scale production to remain profitable in a low-growth environment and more varied vehicle preferences by customers. Womack et al. (Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990) used the term Lean (initially called the Toyota Production System [TPS]) to describe the operational practices Toyota used to remove wasteful overproduction and excessive inventories through small batch production with higher product quality (i.e., a leaner operation with less waste). The development of TPS began during the rebuilding of Japanese industry following World War II and was influenced by Deming’s work on quality control and quality management (Deming, Reference Deming1986) as well as scientific management (Taylor, Reference Taylor1914), sociotechnical systems (Trist & Bamforth, Reference Trist and Bamforth1951), and quality of work life (Hackman & Suttle, Reference Hackman and Suttle1977; Stein, Reference Stein1983).

Through the vision and intellectual contributions of its designers (e.g., Monden, Reference Monden1983, Reference Monden1994; Ohno, Reference Ohno1988), TPS offered a radically different approach to manufacturing—an approach that redesigned both employee jobs and work. In addition, leadership was expected to exemplify the TPS pillars of continuous improvement and respect for people. TPS’s success in manufacturing was soon expanded to other areas of operation, including sales, customer service and support, research and product development, order management, and (external) supply chain management (Liker, Reference Liker2004). Following Womack et al.’s (Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990) introduction of TPS as “Lean” to a broader audience, Lean continued to evolve in both its application to virtually all for-profit and nonprofit business and industry sectors (e.g., health care, government, construction, service, education).

Implementing Lean

The “Lean House”

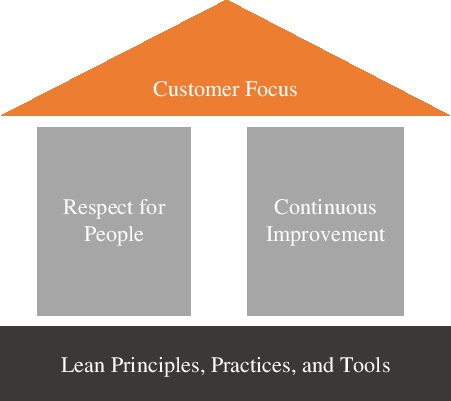

The Lean House is a visual metaphor commonly invoked by Lean practitioners to communicate that Lean is a comprehensive management system. Figure 1 presents an example of a Lean House. As in a constructed house, each of the structural components of the Lean House (i.e., roof, walls, and foundation) is critical, and they all work together as a system. The roof represents the aspirational goals of Lean as determined by the customer: best quality, lowest cost, and greatest value to the customer. The walls (or pillars) are essential to support the focus on customer and reflect the core beliefs or culture of the organization. The “continuous improvement” pillar demands that customer satisfaction and operational methods be benchmarked not against peer or best-in-class comparisons but against perfection to support a culture of relentless, ongoing improvement. The “respect for people” pillar is a critical feature of Lean. In contrast to other improvement strategies that may pursue goals that negatively impact employees or customers (e.g., ignoring employee development, safety, and morale or saving cost at the expense of customer satisfaction), a Lean system strives to achieve organizational goals in ways that are best for the organization, employees, and customers (i.e., nonzero sum outcomes). The foundation reflects elements of Lean principles, practices, and tools critical to the implementation of Lean and expected of all members of the organization from line employees to senior management. Foundational elements might include understanding how Lean applies to all areas, processes, and jobs of the organization; the importance of physically observing work to identify the best solutions to improve it; applying the scientific method to problem solving; and establishing visual management display systems (e.g., progress toward goal success, identification of a critical equipment problem, or status of a production process).

Figure 1. Example of Lean house.

Lean principles and practices

Lean principles and practices direct the successful implementation of the Lean pillars (continuous improvement and respect for people) to make incremental, and often transformational, progress toward Lean goals. Liker (Reference Liker2004) identified 14 principles reflecting four broad categories used by the TPS thought to be essential to the implementation of Lean: (a) Management decisions should be based on enabling long-term success, even if they come at the expense of short-term financial goals; (b) create a quality culture that stops to fix problems so they are not passed along to your customer; (c) grow leaders who thoroughly understand the work, live the philosophy, and teach it to others; and (d) reach decisions slowly by consensus after thoroughly considering all options and then implement decisions rapidly. Finally, the principles and practices typically include the organization’s accepted approach to continuous improvement. In the jargon of Lean, for example, “kaizen” events (also known as a rapid improvement workshop or rapid improvement event) and daily Lean huddle meetings often become the accepted way of doing Lean for a given organization.

Lean tools

Lean tools provide specific techniques for individuals or groups of employees to implement Lean. This set of tools is an amalgamation of tools imported from other improvement philosophies (e.g., Motorola’s Six Sigma: control charts and process capability measurement for variation analysis); tools developed over time by organizations implementing TPS/Lean (e.g., workload leveling to improve flow and reduce burden, value stream mapping, Deming Plan-Do-Check-Act; Deming, Reference Deming1986; Hines & Rich, Reference Hines and Rich1997; Liker, Reference Liker2004; Monden, Reference Monden1994).

Lean in businesses and organizations

Over time, Lean has spread to virtually every business and industry sector in the United States and throughout the world. Using the 2017 US government North American Industry Classification Systems (NAICS) industrial classification as the framework, examples for each sector, drawn from the published literature, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Lean application—examples across NAICS categories

Across NAICS categories, numerous examples of the implementation and impact of Lean are found. Table 2 provides three examples of Lean implementation and outcomes: Wiremold, a manufacturing company where Lean efforts were originally focused (Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2003); Amazon, which reflects the evolution of Lean to nonmanufacturing settings (Onetto, Reference Onetto2014); and ThedaCare, an example from the health care industry that has increasingly embraced Lean to improve patient quality results and financial performance (Miller, Wroblewski, & Villafuerte, Reference Miller, Wroblewski and Villafuerte2014).

Table 2. Examples of Lean implementation and outcomes

* Note. As is common with large scale organizational change such as Lean, benefits are attributed to the intervention and rarely consider other alternative causes such as history effects, Hawthorne effects, etc.

In sum, Lean has been applied across a wide range of for-profit and nonprofit businesses and organizations, attesting to its robust appeal and growth. A growing number of books provide a more detailed discussions of the application of Lean in manufacturing (Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2003), service industries (Swank, Reference Swank2003), health care (Graban, Reference Graban2009), office operations (Locher, Reference Locher2011), higher education (Balzer, Reference Balzer2010), and other business and industry sectors.

The limited presence of Lean in I-O psychology

Despite the widespread use of Lean, the I-O psychology research and practice literature has largely not addressed Lean. Several analyses support this position:

The authors identified ten books considered seminal in the Lean literature (Deming, Reference Deming1986; Liker, Reference Liker2004; Liker & Convis, Reference Liker and Convis2012; Monden, Reference Monden1983; Ohno, Reference Ohno1988; Rother, Reference Rother2010; Rother & Shook, Reference Rother and Shook2003; Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2003, Reference Womack and Jones2005; Womack et al., Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990). Collectively, these books were cited a total of 57,545 times according to Google Scholar (as of May 4, 2017). In contrast, these books were cited in the top 10 I-O journals (Zickar & Highhouse, Reference Zickar and Highhouse2001) only 42 times, with only 10 citations since 2007.

Jasti and Kodali (Reference Jasti and Kodali2014) conducted a literature review of empirical research on Lean manufacturing. None of the 178 research articles published from 1990–2009 were in mainstream I-O journals (i.e., the complete set of I-O journals used in Zickar & Highhouse, Reference Zickar and Highhouse2001). Similar findings were reported by Bhamu and Sangwan (Reference Bhamu and Sangwan2014) in their review of the Lean literature for the period 1988–2012.

Stone (Reference Stone2012) reviewed the Lean literature for the period 1970–2009. Three of the 193 articles and books included were published in mainstream I-O journals (i.e., one in the Journal of Applied Psychology and two in Human Relations).

Balzer et al. (Reference Balzer, Smith and Alexander2009) reported few empirical studies published in mainstream I-O psychology journals examining the impact of Lean on worker perceptions, attitudes, or behaviors; notable exceptions were Birdi et al. (Reference Birdi, Clegg, Patterson, Robinson, Stride, Wall and Wood2008) and Parker (Reference Parker2003). An electronic search of the SIOP conference programs for the previous 5 years identified no papers or presentations on Lean.

There has been a plethora of I-O psychology–related handbooks in recent years. In a review of these handbooks, there is either no mention of Lean or just a passing reference (e.g., Kozlowski, Reference Kozlowski2012, has 42 chapters on organizational psychology–related topics spread across 1,427 pages; Lean manufacturing has one brief mention on only one page out of the total volume).

An informal review of undergraduate I-O psychology textbooks found only a few instances where Lean was mentioned (e.g., Muchinsky, Reference Muchinsky2006).

I-O psychologists’ limited interest precludes the field from playing a significant role in the design, application, and assessment of Lean in businesses and organizations. In his article titled “The Psychology of Lean Production,” Womack (Reference Womack1996) lamented that the psychological impact on workers and supervisors during the transition from mass production to Lean production is not well understood. He argued that research is needed to understand how changes to the organization of work, traditional career paths, and personal accountability for work processes that accompany Lean implementation affect employees and supervisors.

The neglect of lean by I-O psychologists could be a “two-way street,” with Lean researchers also neglecting I-O psychology. As a quick test of this, we reviewed all 259 articles published in one of the leading Lean research outlets, International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, and found that 10.8% of those articles cited at least one article published in top 10 I-O journals (i.e., Zickar & Highhouse, Reference Zickar and Highhouse2001), with 87 I-O articles cited total. These results suggest that Lean researchers are familiar with I-O psychology research, but also that there would also be room for growth in I-O psychology’s influence on Lean. Consistent with Rynes’s (Reference Rynes and Kozlowski2012) analysis of the general gap between I-O psychology scientists and practitioners in which she concluded that both sides were partially responsible for the gap between science and practice, our analysis suggests that both sides might be responsible for the gap between I-O psychology and Lean.

There is some promise in reducing the gap, though, as attention appears to be shifting to a deeper understanding of the human aspect of Lean. Rother and Liker (Reference Rother and Liker2015) stated, “In its first 25 years there have been many definitions of ‘Lean’ typically centered around cost reduction or tool/technical in nature. But the idea of ‘Humans striving to better flow value to a customer’ is a mindset that should perhaps underlie all of them, and may be a better place to start our thinking” (p. 6). Rother (Reference Rother2010) also stated that Lean is above all a “human endeavor,” with individuals and groups expected to effectively implement Lean principles, practices, and tools. Ignoring the role of people reduces Lean to a mere cost-cutting exercise, with minimal focus on continuous improvement and even less so on respect for people. Stone (Reference Stone2012) concluded, “The final void within lean literature was the ‘human factor’” (p. 121). Balzer et al. (Reference Balzer, Smith and Alexander2009) identified numerous areas where I-O content knowledge and strength in measurement, research methodology, and statistics could help address conceptual and methodological challenges and identify evidence-based best practices that improve organizational performance and advance the well-being of people at work. Overall, the continued growth of Lean demands research into the individual and group (and employee and leader) under Lean management and operations, and the I-O psychology community is well-positioned to provide this much-needed support. Contributions from the discipline of I-O psychology would complement and enhance the current work by other professional disciplines to help guide business and organizations that are considering or implementing Lean.

Why has I-O psychology played such a limited role in the understanding, development, and application of Lean?

What may be contributing to the limited presence of Lean in I-O psychology? In this section, we enumerate some speculations about why I-O psychologists have not played a leading—or supporting—role in Lean research and practice.

Concern that Lean is just another management fashion

Dunnette (Reference Dunnette1966) famously inveighed against fads, fashions, and folderol in psychology. He defined fads as “those practices and concepts characterized by capriciousness and intense, but short-lived interest” (Dunnette, Reference Dunnette1966, p. 343), fashions as practices characterized as “the thing to do” (p. 343), and folderol as practices characterized by “excessive ornamentation, nonsensical and unnecessary actions, trifles and essentially useless and wasteful fiddle-faddle” (p. 343). Since that time, management and organizational scholars have studied more scientifically the diffusion of management fads. Abrahamson (Reference Abrahamson1996) defined management fads as “transitory collective beliefs that certain management techniques are at the forefront of management progress” (p. 254). Using examples such as quality circles and employee-stock-ownership programs, Abrahamson showed that these programs and techniques have cycles of heightened activity followed by neglect. As a counterargument to this hypothesis, Lean is embraced by many industries and academic disciplines as well as embraced by both the private and the public sector. As documented by Stone (Reference Stone2012), one can see that the research surrounding Lean has trended in an upward direction with the highest number of research papers written in the 2006–2009 time frame. Furthermore, Samuel, Found, and Williams (Reference Samuel, Found and Williams2015) indicate a positive trend in Lean publications, with 2013 being the highest volume of publication since Lean articles began to appear in 1987. Lean is embarking on 4 decades of notoriety, and the interest is growing, suggesting that Lean is not a fad and will not soon be replaced by the next flavor of the month. Published literature reviews and the volume of published research volume alone suggest otherwise.

Ignoring management trends may allow I-O psychologists to focus on foundational aspects of human behavior, though it lessens their influence when they refuse to engage in shaping these trends and making them more rigorous and conceptually sound. In other management trends, such as TQM, organizational scientists have engaged more (see Hackman & Wageman, Reference Hackman and Wageman1995; Waldman, Reference Waldman1994).

Lean versus other process improvement strategies

The absence of a common definition of Lean (Bhamu & Sangwan’s [Reference Bhamu and Sangwan2014] literature review noted 33 distinct definitions) contributes to the variety of models for implementing Lean, resulting in differences in the depictions of the Lean house, lists of Lean principles and practices, and overlap in the application of Lean tools. One particular point of confusion is how Lean differs from other process improvement strategies designed to improve manufacturing quality such as Six Sigma (6σ; Harry & Schroeder, Reference Harry and Schroeder1999), total quality management (TQM; Deming, Reference Deming1986), and theory of constraints (TOC; Goldratt, Reference Goldratt1989). This is further complicated when these improvement strategies are combined (e.g., Lean Six Sigma or Lean Sigma). As shown in Table 3, whereas there are clearly areas of overlap among the different improvement strategies, Lean maintains some distinct differences from the others. For example, both Lean and TQM work to improve quality through process improvement, though traditionally TQM has emphasized quality (Hackman & Wageman, Reference Hackman and Wageman1995) without acknowledging the strong role of customer expectations in defining quality. As described in the seminal work of Womack et al. (Reference Womack, Jones and Roos1990), the varied preferences of customers were a driving force that lead to the development of Lean.

Table 3. Comparison of improvement strategies

In contrast to TQM, Six Sigma, and TOC, and as noted in our earlier definition, Lean proposes a continuous pursuit of perfection to eliminate waste and to improve flow while also promoting respect for people to the joint benefit of customers, organizations, and employees. For example, process reengineering depended primarily on external consultants to reengineer existing work processes to improve organizational efficiency (Hammer & Champy, Reference Hammer and Champy1993), whereas Lean focuses on building processes improvement skills among all employees that improve efficiency, customer service, and employee development and engagement. Clarification of the Lean “construct” may help the field of I-O psychology see natural connections with its own areas of interest (e.g., employee well-being, leadership, teamwork, and organizational culture and climate).

The quality of Lean research falls short of the standards of I-O journals

Most authors publishing in the area of Lean come from disciplines outside I-O psychology and the social sciences (e.g., operations research, system engineers, quality systems, etc.). Their background and training in one or more areas of research design, psychometrics, and statistics may be less than expected by I-O psychologists, and this weakness may be evident in manuscripts submitted to I-O journals with some level of standards in all three areas. In addition, increasingly I-O psychology journals have an emphasis on theory, and most Lean-based research is more practice focused. Thus, Lean manuscripts might be rejected by I-O journals and ultimately submitted to and published in journals outside mainstream I-O psychology where the emphasis on those areas of scientific and theoretical rigor important to I-O psychology is less. This hypothesis, however, seems less tenable as a reason for the lack of Lean articles in I-O journals in that we have seen no evidence that I-O journal editors have served as gatekeepers to exclude Lean. Although it is true, from our experience, that most Lean articles fail to meet our methodological and theoretical standards, there would still be room for I-O psychologists to collaborate with Lean researchers to bring our methodological expertise to this area. So far, that synergy has not happened.

Overall, limited exposure to Lean in mainstream I-O journals, I-O conferences, and among I-O colleagues results in limited awareness and interest in what Lean is, how it is directly relevant to the field of I-O psychology, and vast opportunities to collaborate with researchers and practitioners outside of I-O psychology (where I-O skills in measurement, design, and statistics would be in high demand). There are numerous opportunities where I-O psychology can contribute to the understanding (e.g., how does standard work impact employee engagement and performance?), application (e.g., under what conditions will the implementation of organization-wide Lean be successful?), and evaluation of Lean (e.g., Is there clear evidence that Lean provides the expected ROI?). As a first step to better engage our field, the following section provides a number of examples where I-O psychology can make major contributions to the understanding, application, and evaluation of Lean.

Areas where I-O psychology can make contributions to the understanding, application, and evaluation of Lean

In this section, we highlight several topics where the field of I-O psychology can contribute to critical issues surrounding Lean. The topics chosen are identified by the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology as specific areas of scientific knowledge for the discipline. Although not all inclusive, we hope that this sample of topics offer insights and stimulate the field’s interest in Lean.

Employee health and well-being

I-O psychologists and occupational health psychologists have significant expertise in increasing the health and well-being of employees by reducing stress, promoting workplace safety, and studying ways to promote healthy behaviors at work (Society for Occupational Health Psychology, 2017). One common criticism of Lean is that increased efficiency and productivity come at the expense of employee well-being (Mehri, Reference Mehri2006).

Research on Lean provides inconsistent evidence about whether employee health and well-being improve or decline due to Lean (e.g., Egan et al, Reference Egan, Bambra, Thomas, Petticrew, Whitehead and Thomson2007; Koukoulaki, Reference Koukoulaki2014; Sprigg & Jackson, Reference Sprigg and Jackson2006). A recent review by Koukoulaki (Reference Koukoulaki2014) examined the impact of Lean on employee health and well-being based on 36 case studies. Koukoulaki reported that only three Lean implementations (all from the service sector) showed consistently positive effects on employee health and well-being; 13 cases reported mixed or null effects. The majority of case studies (N = 20), primarily in the automotive sector, reported negative effects on employee health and well-being. Similar conclusions were reported in Bouville and Alis (Reference Bouville and Alis2014); Cullinane, Bosak, Flood, and Demerouti (Reference Cullinane, Bosak, Flood and Demerouti2013); Knight and Haslam (Reference Knight and Haslam2010); and Mehri (Reference Mehri2006). Limitations in research design (e.g., case studies with no statistical tests) and poor implementation of Lean (e.g., failure to align management style with Lean principles, as noted by Koukoulaki, Reference Koukoulaki2014) may temper any conclusions from this limited research.

Conceptually, the implementation of Lean is intended to reduce workplace stressors by reducing customer complaints (due to bad processes), avoid overburdening employees with work that is unnecessary and unproductive, and provide employees with role clarity and greater control over their work (Liker, Reference Liker2004; Liker & Convis, Reference Liker and Convis2012). In support of predictions that the implementation of Lean will positively affect employee well-being, some researchers have focused on employee participation and autonomy. Von Thiele Schwarz, Nielsen, Stenfors-Hayes, and Hasson (Reference Von Thiele Schwarz, Nielsen, Stenfors-Hayes and Hasson2017) reported that the participatory and visual problem-solving techniques that are part of kaizen events have positive effects on well-being. Westgaard and Winkel (Reference Westgaard and Winkel2011) noted that group autonomy and participation in a Lean environment alleviated the negative effects of Lean on well-being; Cullinane, Bosak, Flood, and Demerouti (Reference Cullinane, Bosak, Flood and Demerouti2017) also found that autonomy (in the form of job crafting) enhanced job engagement in the Lean workplace, which in turn is likely to reduce perceived stress. Although the amount and type of autonomy available to workers in Lean systems are disputed (Jackson & Mullarkey, Reference Jackson and Mullarkey2000; Parker, Reference Parker2003), the autonomy and participation of workers can be positively affected by the introduction of Lean and may provide an avenue to enhancing employee health and well-being.

Additional relevant research questions that I-O psychology could help address include the following:

How much participation in Lean implementation is needed to preserve or enhance employee health and well-being? For example, does participation in organization-wide training on Lean principles and practices enhance positive employee outcomes, or is more intense, active participation in a rapid improvement workshop needed to achieve health and well-being benefits?

What Lean principles and practices lead to enhanced employee health and well-being in Lean workplaces? For example, are improvements in employee work processes sufficient to enhance employee health and well-being, or do the benefits come from the engagement and empowerment of employees to change their own work processes?

At what point in Lean implementation, and ongoing support of Lean, is participation more critical for promoting health and well-being? For example, does a high degree of participation among front line employees during lean implementation enhance employee health and well-being?

Leadership

I-O psychology has had a prominent history of studying the characteristics and traits of successful leaders, how leaders are influenced by their environment, and behaviors and strategies that leaders can use to implement change. Leadership is regularly invoked as fundamental to Lean success (Liker, Reference Liker2004; Liker & Convis, Reference Liker and Convis2012; Rother, Reference Rother2010; Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2005). Lean relies on leaders to empower individuals and teams to implement process improvements and sustain a focus on customer value. Lean leaders are expected to act as champions for Lean in their organizations: modeling Lean values and behaviors, teaching and mentoring Lean to subordinates to innovate and solve problems on their own, and advocating for staff as they question assumptions, collect data, and develop improvements. Some authors have focused on phases of Lean implementation and the unique leader behaviors needed to gain process improvements at each phase (e.g., Tortorella, de Castro Fettermann, Frank, & Marodin, Reference Tortorella, de Castro Fettermann, Frank and Marodin2018). Other authors begin with specific Lean principles and values, such as respect for people or continuous improvement, and associate leadership characteristics with those principles and values (van Dun, Hicks, & Wilderom, Reference Van Dun, Hicks and Wilderom2017).

Lean leadership is typically conceptualized as a unique set of values and behaviors with limited reference to extant theories or models of leadership. One notable exception is a study by Sosik and Dionne (Reference Sosik and Dionne1997), where, using cross-sectional survey data, they found a relation between Lean leader behaviors and transformational leadership. Kim and Hochstatter (Reference Kim and Hochstatter2016) and Laohavichien, Fredendall, and Cantrell (Reference Laohavichien, Fredendall and Cantrell2009) also reported positive correlations between transformational leadership and the effectiveness of Lean implementation using surveys with cross-sectional convenience samples. In contrast, van Assen (2016) studied the relations between Lean practices (e.g., visual management, setup reduction) and use of Lean tools (e.g., kaizen improvement tools, root-cause analysis tools) with type of leadership and management behaviors that promote improvement (e.g., timely feedback on employee improvement ideas). His cross-sectional survey using a convenience sample of 190 organizations found a strong connection between Lean practices and tools with improvement behaviors by management, as well as with a measure of empowering leadership (Conger, Reference Conger1989); relationships with transformational leadership and servant leadership were not significant. Overall, results suggest the need for more research on the relationship among leadership theories and practices, Lean principles and practices, and employee attitudes and behavior (and organizational effectiveness).

The complexity of leadership highlights the need to more clearly define how leadership influences Lean (or vice versa). Relevant research questions could include the following:

Do leadership models and practices influence the adoption of Lean? Are high leader–member exchange theory (LMX) leaders more likely to have a successful lean implementation?

What leader behaviors most influence the successful implementation of Lean and predicted positive outcomes both for employees and the organization? What transformational leadership behaviors (e.g., individualized consideration) most influence the successful implementation of Lean?

Do individual differences among leaders predict which leaders will provide initial and sustained support for Lean over time? Do the components of authentic leadership (e.g., self-awareness) influence the long-term successful implementation of lean initiatives?

Are there important constructs that mediate the relationship between leader support for Lean and employee acceptance of Lean? For example, does trust in management mediate the relation between transformational leadership and employee engagement in lean implementation?

Teamwork

I-O psychology has widely documented the potential and peril of teams, including research on how to form and manage teams, what types of tasks are best suited to teams (rather than individuals), and factors, such as technology, that can impact team performance. The role of teams is central in a Lean organization: ad hoc, rapid-improvement event teams plan, implement, and evaluate improvements to work processes to reduce waste and the flow of work; existing teams responsible for a specific work process meet daily to review yesterday’s performance metrics, solve any problems, and communicate information to support today’s performance; and work is redesigned using flexibly staffed “work cells” where the size of the team and members’ assigned tasks adjust to immediate demands of the customer (Liker, Reference Liker2004; Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2003). Therefore, the study of team formation, composition, process, and effectiveness in Lean organizations should be an important area of study. Some Lean scholars and practitioners (e.g., Martin, Reference Martin2012) assume that team effectiveness is assured by the successful implementation of Lean. Others (e.g., Womack & Jones, 1996) assert that poor team design, poor team leadership, and poor teamwork skills persist in Lean organizations, and their negative impact on performance and culture are underestimated by Lean practitioners.

Lean scholarship on teams is in the nascent stages of addressing these and other issues. Delbridge, Lowe, and Oliver (Reference Delbridge, Lowe and Oliver2000) reported that the allocation of responsibilities among Lean team members, including middle managers, technical specialists (e.g., electricians, tool makers), team leaders, and shop floor operators, is related to the success of Lean implementations. Procter and Radnor (Reference Procter and Radnor2014) and Ulhassan, Westerlund, Thor, Sandhal, and von Thiele Schwarz (Reference Ulhassan, Westerlund, Thor, Sandahl and Von Thiele Schwarz2014) provide both arguments and evidence that initial dysfunction within teams limits the success of Lean implementation. Wilkens and London’s (Reference Wilkens and London2006) study of continuous quality improvement teams at eight hospitals using survey data and evaluations of team performance effectiveness (based on interviews with team leader and facilitator) provided preliminary evidence that the content expertise (e.g., “Educates the team on problem-solving process”) and facilitation skills (e.g., “Helps team members avoid being sidetracked”) of the team facilitator are associated with team performance. Finally, van Dun and Wilderom (Reference Van Dun and Wilderom2016) provided empirical evidence from 25 Lean teams that indicated leader values appear to affect information sharing by team leaders who, in turn, affect the functioning within Lean teams.

Incorporating team research from I-O psychology to aid in the understanding of Lean provides numerous opportunities for research:

What characteristics (e.g., experience, skills, personality, etc.) should be considered when selecting employees to serve on a Lean or rapid improvement event team? Do employees high in openness to experience generate more ideas during a rapid improvement event?

How do team members and team leadership, independently and jointly, affect the success of Lean implementation? For example, are leader-led or self-directed teams more effective in the practice of daily Lean team meetings?

Climate and culture

I-O psychologists have a long history of researching the influence of organizational culture and climate on employee performance, attitudes, and well-being. Aspiring and successful Lean organizations recognize the important role organizational climate and culture play in creating a long-term and sustainable work environment committed to respect for people and continuous improvement (Liker, Reference Liker2004; Womack & Jones, Reference Womack and Jones2005). Although some authors report that Lean is robust to organizational culture (Hardcopf & Shah, Reference Hardcopf and Shah2014), more evidence suggests that Lean success is dependent on organizational practices and values that align with Lean principles and values (Padkil & Leonard, Reference Pakdil and Leonard2015). Bortolotti, Boscari, and Danese (Reference Bortolotti, Boscari and Danese2015) found that that successful Lean manufacturing plants, compared to less successful plants, had cultures that reflected higher levels of institutional collectivism, future orientation, and humane orientation and lower levels of assertiveness.

Taking an anthropological view, Van Landeghem (Reference Van Landeghem, Modrák and Semano2014) suggested that cultural differences between Japan, where Lean originated (i.e., Toyota Production System), and Western cultures make it unlikely that Lean would be successful when implemented there. This would imply that that US organizations using Lean would have poorer performance than the same companies using Lean in Japanese culture. However, Lacetera and Sydnor (Reference Lacetera and Sydnor2015) found, contrary to this hypothesis, that Japanese automakers’ production facilities in the US were similar in productivity and quality compared to those automakers’ Japanese facilities. Hence, evidence is suggestive that organizational culture may be more influential than national culture in creating Lean organizations.

Differences in conceptualizing climate and culture in the Lean literature are reflective of early debates within the I-O literature, and climate and culture research in I-O has advanced significantly over the years. I-O psychology can contribute to understanding the role of organizational climate and culture in organizations currently practicing Lean or those considering its implementation:

What is the role of climate and culture in a Lean workplace? For example, do organizational climate and organizational culture have similar or different roles in the successful implementation of Lean?

Do variations of climate or culture exist across successful Lean operations? For example, is there a preferred climate and culture “profile” to support an organization’s transition to Lean?

Can the implementation of Lean management practices create a new Lean climate and culture? For example, does the new Lean climate and culture impact the organizational climate and culture?

Other areas of I-O psychology contributions to Lean

In addition to the topics above, there are many other areas where the field of I-O psychology can contribute to Lean: job and work design, job performance, training and development, organizational design, motivation and reward practices, organizational development and change, and communication practices are just some of the I-O areas of expertise that could help inform Lean research and practice. For example, research in judgment and decision making (JDM), especially managerial decision making, may benefit Lean researchers and practitioners. As psychologists have known for a long time that individual decisions often fail to conform to rational economic person-standards, research on biases and heuristics would be useful in trying to understand why Lean systems often fail to perform as expected. I-O psychology might also contribute in the areas of training and individual differences. Training research and techniques can be used to help employees adapt to new processes and techniques as part of Lean implementation, as well as to judge the efficacy of various training programs. Research on individual differences could be useful in understanding and appreciating why some employees might adapt better under Lean systems. Lean practitioners often ignore individual differences, preferring to focus on work. As psychologists, we appreciate both the importance of systems and individual differences, and our work on measurement of personality and ability could be useful in helping organizations select employees likely to succeed in a Lean system as well as identify individual training needs.

Furthermore, I-O psychology’s expertise in psychological measurement of relevant workplace constructs is an area from which Lean could benefit. Lean practice often focuses on objectively measured criteria such as time reduced, percentage of defects, and wait time. More difficult to measure constructs such as customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and creative problem solving, all embedded in Lean’s nomological net, would be challenging to assess or develop by individuals without a background in psychology or measurement. In general, our expertise of developing reliable and valid measures of psychological constructs could be a real asset to Lean practitioners and help them include constructs that they have neglected in favor of others more easily measured. Similarly, Lean researchers’ expertise lays in the design of experiments and statistics for the study and improvement of machines and equipment, process capability, and quality of parts; their background in designing studies to understand, predict, and change individuals, groups, or organizations is more limited. I-O psychology’s expertise in research design and methods can help conduct essential research to document statistically significant and generalizable findings on the benefits of Lean. Cascio (Reference Cascio1995), in a review of directions I-O psychologists should take, concluded: “Thousands of change efforts are initiated every year. If the field is to maintain a scientific basis for its continued existence, then it is essential to evaluate change efforts to determine which interventions have the greatest impact on which organizational variables” (p. 937). I-O psychologists applying our research and psychometric expertise in collaboration with Lean researchers and practitioners might make Lean research more palatable for traditional I-O psychology journals.

Conclusions: An invitation to I-O psychology

Throughout this article, we argue that I-O psychologists have missed opportunities to introduce Lean in their research activities, forgoing potential research collaborators and losing out on significant consulting opportunities for practitioners. As cited earlier, I-O psychologists are urged to be wary of management fads and fashions (Dunnette, Reference Dunnette1966), though we would underscore that the Lean literature has persisted for 30-plus years, defying trends of typical management fashions. As some management fashion scholars (e.g., Abrahamson, Reference Abrahamson1996; Bort & Keiser, Reference Bort and Kieser2011) have suggested, fads may promote innovation by removing assumptions and allowing researchers to “experiment with different innovations on the basis of this fashion” (Bort & Kieser, Reference Bort and Kieser2011). So even if Lean fits the definition of a management fashion, I-O psychologists who systemically ignore a sizeable management literature miss an opportunity for research and practice innovation. Although this article focuses on the relative neglect of Lean by I-O psychologists and the potential role that they can play, we do believe that a similar case could be made for other management practices. By partnering by other types of organizational consultants, I-O psychology can ensure that management practices are not just influenced by the latest trends but remain evidence based.

One criticism about Lean that we feel is a big barrier for pursuing Lean research and practice is the complex number of terms, the adoption of catchy phrases for otherwise mundane organizational constructs, and its confusion and overlap with other management techniques such as Six Sigma, with its black belts and other accruements. Lean and related techniques can seem to be characterized by Dunnette’s “excessive ornamentation” (Reference Dunnette1966, p. 343). We remind readers, however, that good ideas that are well-accepted by most I-O psychologists are often distorted in the popular media and in the hands of businesspeople who are willing to take good scientific ideas and use them in unvalidated ways. Charlatans who promote the use of personality tests inappropriately do not weaken overall our core belief that personality is an important predictor of work outcomes. We urge I-O psychologists to see past the external marketing and find ways that they can use I-O evidence-based practices to improve Lean. We hope this article convinces some I-O psychologists to incorporate Lean in their research and practice. By systematically ignoring management trends, such as Lean, we lessen our influence. Ignoring a particular management trend might seem like a prudent short-term strategy, though largely ignoring a management trend that has persisted for 30 years seems like a bad long-term strategy. We urge I-O psychologists to engage with Lean researchers and practitioners by presenting our traditional I-O research in Lean contexts, such as contributing to Lean conferences, publishing in Lean-focused journals, and engaging with practitioners who frame their work within the Lean realm. Just attending conferences in our own specialty areas and publishing journals that only I-O psychologists read will lead to isolation. We urge I-O psychologists to be both critical and constructive in this engagement.

Womack (Reference Womack1996) commented ironically that “the analysis of lean production in comparison with the previous dominant industrial paradigm of mass production is perhaps weakest in the area of applied psychology!” (p. 119). In the last 20 years, the neglect of Lean by I-O psychologists has not improved this noted shortcoming. We hope that this article will spur interest by I-O psychologists to (re)visit the Lean literature with fresh eyes. We strongly believe that I-O psychologists’ knowledge and methodological expertise can help improve Lean systems and reinvigorate Lean research and practice.