Introduction

Over the past 10 years, the organic sector has expanded continuously in Europe due to policy support and a growing market demand for organic productsReference Willer and Kilcher1. Many farmers convert to organic farming each year, in line with this development. Nevertheless, the total number of organic farms has not increased constantly in Europe. In several countries, the number of organic farms decreased in some years of the past decade. This holds true for Austria (1999–2001, 2006, 2007), Denmark (2003–2006, 2008, 2009), Finland (2001, 2003–2006, 2008), Netherlands (2003–2006), Switzerland (2006–2009) and the United Kingdom (2003, 2005, 2008, 2009)2.

However, these data provide no information about how many organic farmers gave up completely and how many farmers reverted to conventional agriculture (in this article, the term reversion stands for farms which were once certified organic but deregistered from organic certification and control in order to continue farming conventionally). Besides, the figures representing the total number of organic producers per year include dropouts and newcomers simultaneously. Therefore, high fluctuations caused by a large number of farmers leaving organic certification while at the same time many others newly registering for it are not necessarily conspicuous as long as the overall number is still increasing.

Against this background, this article aims (i) to give an overview of the extent of reversion to conventional agriculture in Europe based on statistics, (ii) to conceptualize the decision to revert in the form of a theoretical model, (iii) to compare farmers’ reasons to revert to conventional farming based on existing studies, and (iv) to identify further research needs.

In the following sections first an overview of the extent of reversion in Europe and the USA is given based on official statistics as well as on results of studies. Subsequently, the theoretical model is described, which is applied in order to understand the reversion decision. This is followed by a review of the research results about the reasons for reversion. Finally, some conclusions for further research are drawn.

Dimensions of Reversion

Official statistics on reversion

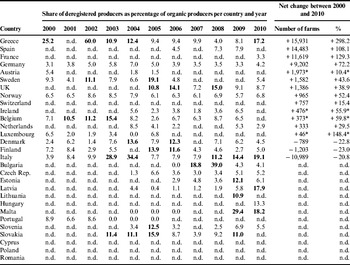

The statistical data are supplied by the European statistical database Eurostat, which gives an overview about the entrants and dropouts in organic farming. For some countries, however, only the total number of organic farms per year is available without the respective share of newly converted farms and the number of those who reverted. For some other countries, the data are completely missing. In addition, it has to be noted that the statistics regarding deregistration only give a total figure of all the deregistered farms and do not differentiate between the reversions to conventional agriculture and farmers giving up farming altogether. Due to the amount of missing data, it is difficult to report the overall trends across countries over time. Nevertheless, some interesting developments can be observed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Share of deregistered producers and net change from 2000 to 2010 in European countries.

n.d.=no data.

* =net change calculated between 2000 and 2009 as data for 2010 were not yet available.

Source: Own compilation following2.

In Greece, there were several years with an extremely high percentage of reversions, especially 2002, where 60% of all organic farmers reverted. Not surprisingly, the total number of Greek organic farms actually decreased in 2002, as well as in 2007, 2008 and 2010. Looking at the whole period between 2000 and 2010, however, reversions were more than compensated for by a large number of new conversions to organic farming. The overall number of organic farms in Greece has therefore increased by almost 16,000 farms during this time, which represents a growth of nearly 300%. A large net increase of over 10,000 organic farms, which represents a growth of more than 100% between 2000 and 2010, also happened in Spain and France. For these countries, however, there are hardly any data available regarding reversions or new conversions in the intermediate years.

Germany and Norway had steady dropout rates, always remaining under 10% of all organic farms per year. Over the 10-year period, both countries had a net increase in the number of organic farms, which lay above 50% in Norway and above 70% in Germany. In Belgium, dropout rates varied considerably between 15% in 2003 and 3% in 2005. Nevertheless, the overall number of organic farms increased over the period between 2000 and 2009 by almost 60%.

In Denmark, Finland and Italy the total number of organic farms decreased since 2000. The largest net decrease happened in Italy with almost 11,000 fewer organic farms in 2010 than in 2000, which represents a decrease of about 20%. In Italy, the largest deregistration rates appeared in 2003 and 2004. Similarly decreases of more than 20% over the 10-year period can be observed in Finland and Denmark, although the overall number of organic farms is much lower in these countries.

Evidence of reversion from the literature

The dimensions of reversion in the respective countries were determined in the examined studies either by asking current organic farmers about their intentions regarding the prolongation of organic farming, by surveying ex-organic farmers or by analyzing national statistical data about deregistered producers.

When asked about their intentions concerning the continuance of organic farming or planned reversion to conventional agriculture, there were very similar results in different European countries and in different years. In an early study in Germany in the 1990s, 14% of the interviewed organic farmers were determined to revert after the expiration of the first organic program, whereas 36% were undecidedReference Hamm, Poehls and Schmidt3. Ten years later in a Danish study, 13% considered reversion within the following 5 yearsReference Risgaard, Langer and Frederiksen4.

An interesting course of studies was conducted in Austria: In a survey in 1999, 13% of the interviewed organic farmers were determined to revert and 23% were undecidedReference Kirner and Schneeberger5. Of those farmers who participated in the follow-up survey 3 years later, 13% had actually reverted. The reverted farmers were mostly those who had indicated earlier that they planned to revert, but also some who had originally been undecided or intended to stay organicReference Kirner, Vogel and Schneeberger6.

More accurate indicators of reversion are therefore figures of farms which already reverted to conventional agriculture. The reviewed literatureReference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7–Reference Sierra, Klonsky, Strochlic, Brodt and Molinar14 gives various figures regarding the number of deregistered farms in the respective countries (see Table 2). However, in most cases the statistics only describe the deregistered producers in general and do not differentiate between the reverted farmers, namely those who once farmed organically and are now farming conventionally, and those farmers who once farmed organically and gave up farming completely. The termination of the whole farming enterprise is a general problem of agriculture in the context of overall structural change, which is not the focus of this article. A comparison between different countries is furthermore difficult due to a very heterogeneous reference framework, as some authors report deregistered producers per country and year, others over a period of several years or only those deregistered from one certification body.

Table 2 Deregistered farms and total number of farms.

n.d.=no data.

Source: own compilation.

Framework

In order to conceptualize the decision to revert a farm, a theoretical model based on decision theory is developed. Decisions can be understood as a choice between different options, which aim to achieve certain goals. According to Mintzberg et al.Reference Mintzberg, Raisinghani and Théoret15, the process of decision-making consists of the following activities which are not necessarily made in a sequential order: (i) identification of problems and opportunities, (ii) definition and clarification of options, and (iii) evaluation and choice between alternatives. Putting this into the context of reversion, the decision to return to conventional farming is the choice of an alternative to organic farming. It is therefore a correction of a previous decision (to convert the farm) based on an ex-post evaluation of the conversion decision and an ex-ante evaluation of maintaining the organic status. (This refers to the situation in which a farmer first converts and later reverts the farm. Cases in which a reversion is due to new farm management are not taken into account.) A reversion occurs if the ex-post/ex-ante evaluation leads to a negative judgment of the organic status and/or if the net utility of conventional management is expected to be higher in the future. Following these thoughts, reasons for the decision to revert can be divided into (i) unmet expectations, (ii) promising alternatives, and (iii) the judgment of transaction costs.

Key elements of post-evaluation are expectations connected to the conversion. From the literature it is known that farmers convert to organic farming for various reasons. PadelReference Padel16, for example, divides the reasons for conversion to organic farming into farming related and personal motives (Table 3). The farming related motives consist of animal husbandry, technical reasons and/or financial motives. Personal health and general concerns such as the state of the environment or food quality are personal motives for conversion.

The relative importance of the different motives varies. In a Canadian study it was found that ‘health and safety concern and environmental issues are the predominant motives for conversion, while economic motives are of lesser importance‘Reference Cranfield, Henson and Holliday17. Several other studies also emphasize that socialReference Mzoughi18, health, or environmental reasonsReference Cranfield, Henson and Holliday17, Reference Koesling, Flaten and Lien19, Reference Best20 play a significant role. Nevertheless, in other studies it was found that subsidiesReference Dabbert, Häring and Zanoli21–Reference Daugbjerg, Tranter, Hattam and Holloway24 and supposedly higher profitsReference Dabbert, Häring and Zanoli21, Reference De Cock25 are the driving factors for converting to organic farming. Since conversion-related motives are connected to specific expectations, reversion to conventional farming methods can be explained by unmet expectations and a perceived lower utility of the organic system than expected. In this context, utility can be defined as the sum of economic benefits and the value to act according to one's personal beliefsReference Mann and Gairing26. In algebraic terms, the relationship between expected and effective utility of organic farming can be formulated as follows, with ![]() $E(U_{{\rm org}} )_{t_0} $ as expected utility before the conversion and

$E(U_{{\rm org}} )_{t_0} $ as expected utility before the conversion and ![]() $(U_{{\rm org}} )_{t_1} $ as effective utility after the conversion:

$(U_{{\rm org}} )_{t_1} $ as effective utility after the conversion:

A simple example is the expected profit under organic management. If the farmers are not able to obtain premium prices and yields decrease substantially, the profits can be lower under organic management than initially expected. In this case, the expectation that a conversion to organic farming would solve financial problems is not fulfilled.

Unmet expectations do, however, not necessarily lead to reversion. For this, it is also relevant that the conventional system represents a realistic alternative. It is important to bear in mind that the net utility of either organic or conventional farming is not static over time. Changing framework conditions can decrease the utility of the organic system (e.g. due to new organic regulations which are difficult to implement) and/or increase the utility of conventional management (e.g. due to rising conventional prices). Another element of the decision to revert is therefore based on an ex-ante evaluation of alternative (non-organic) management strategies and the expectation that they will lead to a higher utility. A reversion becomes likely if the expected utility of future conventional farming ![]() $E(U_{{\rm con}} )_{t_{_2}} $ is higher than the expected utility of maintaining the organic status in the future

$E(U_{{\rm con}} )_{t_{_2}} $ is higher than the expected utility of maintaining the organic status in the future ![]() $E(U_{{\rm con}} )_{t_{_2}} $. In algebraic terms, this can be formulated as

$E(U_{{\rm con}} )_{t_{_2}} $. In algebraic terms, this can be formulated as

A third element is related to transaction costs. Reversion to conventional farming could, for example, mean that specific machinery used for organic management techniques has no or only little use under conventional management. In fact, all conversion-related investments can be counted as transaction costs. Besides, if an organic farm receives organic support payments under agri-environmental programs of the EU, a reversion before the end of the 5-year contract period implies that the farmer has to reimburse the payments received under the current management contract. High transaction costs are therefore an important barrier for reversion in EU countries.

Thus, the utility of reversion U rev can be divided into three elements: (i) the difference between expected and effective utility of the organic system with respect to economic performance, animal husbandry and technical problems, personal health, nature conservation and environment, food quality and other aspects; (ii) the difference between the expected utility of conventional and organic farming in the future; and (iii) the transaction costs of reversion TCrev.

From a theoretical point of view, a reversion would be useful for a farmer if the utility U rev has a positive value.

Empirical Evidence on Farmers’ Reasons for Reversion

Approach

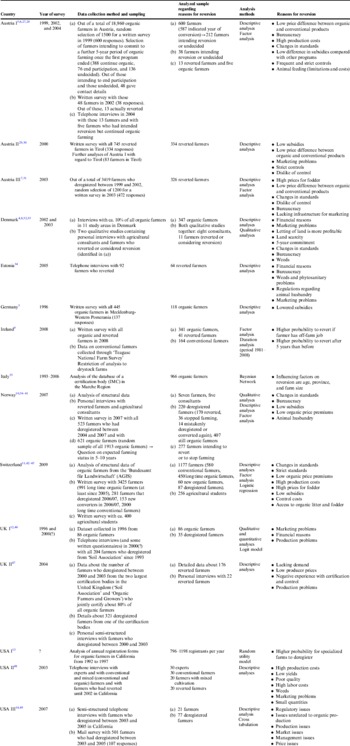

In order to reveal farmers’ reasons for reverting to conventional farming methods, a thorough literature research was conducted in scientific journals, databases, library catalogues, gray literature, project reports and online publications. In total, 12 relevant studies were identified from six EU-countries (Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Italy and the United Kingdom) and two non-EU-countries (Norway and Switzerland). Additionally, three studies dealing with reversion of organic farms in the USA were found. Since the organic certification and support policies in the USA differ substantially from the situation in Europe, the reasons for reversion in the USA are discussed here only marginally. An overview of the studies is given in Table 4Reference Hamm, Poehls and Schmidt3–14,Reference Schermer27–49.

Table 4 Studies about deregistered organic farmers.

Deregistered: farmers who quit organic farming but it is unknown whether they quit farming altogether or continued with conventional farming.

Reverted: farmers who quit organic farming and continued with conventional farming.

Reasons for reverting from organic to conventional farming

Researchers facing the phenomenon of reversion used different approaches by surveying farmers and consultants or analyzing organic registration data. The most commonly used survey method to identify reasons for reversion was a written or telephone survey with all or a sample of farmers who deregistered during a certain period, asking about their reasons in retrospect, e.g. in AustriaReference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7, Reference Schermer29–Reference Schmid31, EstoniaReference Ploomi, Luik and Kurg34, the United KingdomReference Rigby and Young12, Reference Rigby, Young and Burton46 and the USAReference Sierra, Klonsky, Strochlic, Brodt and Molinar14. In IrelandReference Läpple9 and NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10, Reference Lien, Flaten, Koesling and Løes36, Reference Koesling and Løes40, Reference Løes, Flaten, Lien and Koesling41, researchers surveyed organic and deregistered farmers simultaneously, in Switzerland additionally conventional farmersReference Reissig, Ferjani and Zimmermann11, Reference Reissig, Ferjani and Mann42–Reference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann45. Kirner et al. (AustriaReference Kirner, Vogel and Schneeberger6, Reference Kirner, Vogel and Schneeberger28), Kaltoft and Risgaard (DenmarkReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8), Koesling et al. (NorwayReference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37, Reference Koesling, Løes, Flaten and Lien38), Harris et al. (United KingdomReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47) and Sierra et al. (USAReference Sierra, Klonsky, Strochlic, Brodt and Molinar14, Reference Sierra, Klonsky, Strochlic, Brodt and Molinar49) used a qualitative survey with farmers and/or agricultural consultants to accompany quantitative results. In GermanyReference Hamm, Poehls and Schmidt3, AustriaReference Kirner and Schneeberger5, Reference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27 and NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10, organic farmers were asked whether they intended to continue organic farming during the next 5–10 years or after the current organic program ended. In AustriaReference Kirner, Vogel and Schneeberger6, Reference Kirner, Vogel and Schneeberger28, this study was complemented by a follow-up survey to determine the actual farming status some years later. Harris et al. (United KingdomReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47) and Klonsky and Smith (USAReference Klonsky, Smith, Hall and Moffitt13) on the other hand analyzed registration records in order to find determinants for reversion in the structural data of farms. Koesling and LøesReference Koesling and Løes50 already presented a comparison of reasons for reversion in Austria, Denmark, Estonia, and Norway.

Analyzing the literature, the farmers’ reasons for the reversion of their farms can be roughly classified into economic motives, difficulties regarding certification and control, and problems with production techniques and the macro environment of the organic farm (see Table 4). For most farmers, however, the decision to revert is a result of different factors, including various additional individual or personal ones.

Economic reasons

Nearly all studies point out that economic problems are the main reason for most organic farmers to revert. Agricultural consultants in Denmark explained that only a few organic farmers would consider reversion at all if the overall economic basis was betterReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8. Harris et al. (United KingdomReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47) and Läpple (IrelandReference Läpple9) also found that some farmers apparently reverted only due to economic necessities.

According to Schneeberger et al.Reference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27, the difference between organic subsidies and payments through other environmental programs in Austria was too small. Ferjani et al.Reference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann44 also reported that organic subsidies and direct payments were too low and uncertain in Switzerland. In a German study, Hamm et al.Reference Hamm, Poehls and Schmidt3 found that one-third of the surveyed 118 farmers had converted mainly due to attractive organic subsidies in a certain extensification program. Consequentially, when asked about the continuance of organic agriculture under another program with reduced subsidies, only 50% were determined to continue, whereas the other half was either undecided or determined to resign from certification. In Denmark, some farmers stated that they only converted to organic in order to use organic subsidies for the further development of their farms (e.g., build new stables). They had never planned to continue with organic farming beyond the first 5-year periodReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8.

Several authors suggested that producer prices for organic products were generally not sufficient to compensate increased production costs (e.g. in AustriaReference Kirner, Vogel and Schneeberger6, Reference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7, SwitzerlandReference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann45 and NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10, Reference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37). When asked in detail, farmers complained about insignificant organic price premiums compared to conventional products, whereas the additional time and effort as well as prices for purchased fodder or seeds were too high (AustriaReference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7, Reference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27). They also mentioned difficulties to obtain organic fodder and seeds. Ploomi et al. (EstoniaReference Ploomi, Luik and Kurg34) reported that some farmers reverted because they experienced a higher workload for organic methods and simply did not have enough workforce.

Flaten et al. (DenmarkReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10) found that specialized farms generally had more economic problems and a higher likelihood to revert than diversified farms. Risgaard et al. (DenmarkReference Risgaard, Kaltoft and Frederiksen33) explained that marketing of organic products was much more challenging than that of conventional products and therefore an organic farmer needed to be interested not only in producing but also in marketing his products.

Certification and standards

Difficulties with certification, control and organic standards are also the major reasons for reversion. Obviously, regulations as well as certification and control processes vary between different systems, even within the EU. Nevertheless, many similarities were found regarding farmers’ perception of certification, standards and control. In Austria, for example, these problems were the second most important reason after economic aspectsReference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27. The economic aspect of certification and control, namely the certification and control costs, were also very important in some cases (United KingdomReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47 and SwitzerlandReference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann44). The burden of fixed control and certification costs can be a problem especially for small farms (AustriaReference Schmid31 and United KingdomReference Rigby, Young and Burton46).

Many farmers complained about a huge amount of bureaucracy when asked about the certification and control process (AustriaReference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27, DenmarkReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8, EstoniaReference Ploomi, Luik and Kurg34 and NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10, Reference Koesling and Løes40). According to Darnhofer et al. (AustriaReference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7), farmers also perceive the everyday documentation of procedures as too complex. Besides, farmers criticized frequent changes in organic regulations and necessary adaptations they have to make to conform to regulations (AustriaReference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7, NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10 and SwitzerlandReference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann44). The frequent changes resulted in insecurity and frustration (AustriaReference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27, Reference Schmid31 and DenmarkReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8), especially when farmers perceived the alterations to be scientifically unjustified (NorwayReference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37). In addition to the overall unpredictable political framework, organic farmers felt that the security of their future income was at risk. Changing regulations can cause enormous difficulties, in particular for organic farms with animal husbandry, especially in cases when the modification of stables necessitates high and long-term investments (AustriaReference Schmid31, EstoniaReference Ploomi, Luik and Kurg34 and NorwayReference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37).

Many farmers complained about very strict or highly complicated regulations that are hard to fulfill (AustriaReference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27, NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10, SwitzerlandReference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann44 and United KingdomReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47). Others generally did not like their farms to be inspected (AustriaReference Darnhofer, Eder, Schmid and Schneeberger7, Reference Schmid31). One of the main reasons for farmers to revert in the United Kingdom was negative experience with the certification and control processReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47. In Denmark, farmers said that dissatisfaction with control procedures was not generally a reason for reversion, it was only in those cases when the inspector was too strictReference Kaltoft and Risgaard32.

Furthermore, for many farmers the commitment to the certification period of 5 years (as stated by organic EU-Regulations in order to receive organic subsidies) was too long, and farmers wanted more flexibility. Some stated that the first 5-year period was acceptable, but the commitment to the next 5 years was too much (AustriaReference Schmid31 and DenmarkReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8). Generally, there is a higher likelihood to revert after the first 5-year period than during the first 5 years, otherwise farmers would have to reimburse the subsidies received (IrelandReference Läpple9).

Production techniques

Problems regarding organic production techniques were mentioned frequently in the analyzed studies, but interestingly, they only played a minor role in most cases (e.g., AustriaReference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27, Reference Schmid31). A Danish publication even stated that problems regarding production techniques cannot be viewed as an important reason for reversionReference Risgaard, Kaltoft and Frederiksen33. Nevertheless, several authors pointed out some problems with organic plant production and animal husbandry that led to reversions. Rigby et al. (United KingdomReference Rigby, Young and Burton46), for example, mentioned problems with production techniques especially with access to technical information. Ploomi et al. (EstoniaReference Ploomi, Luik and Kurg34) stated that, as organic cultivation required more knowledge, the lack of special knowledge about organic production methods sometimes led to problems.

The major difficulties named by farmers regarding plant production were weeds (AustriaReference Schneeberger, Schachner and Kirner27, NorwayReference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37 and SwitzerlandReference Ferjani, Reissig and Flury43), phytosanitary problems (EstoniaReference Ploomi, Luik and Kurg34) as well as sufficient nutrient supply for the cultivated plants (NorwayReference Koesling and Løes50). These problems resulted in low yields (NorwayReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10) or poor quality due to which the products were not marketable. Nevertheless, the agricultural consultants in Denmark mentioned that weeds were not as problematic as the farmers anticipated before the conversion to organic farming. Interestingly, Kaltoft and RisgaardReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8, Reference Kaltoft and Risgaard32 reported in their qualitative study that Danish farmers did not intend using pesticides after resuming conventional farming. Nevertheless, some farmers outsourced spraying to avoid doing it themselves.

In animal husbandry, the major difficulties were access to sufficient amounts of organic litter and fodder (e.g., SwitzerlandReference Ferjani, Reissig and Flury43). In Norway, obtaining enough straw for litter was a problem because many organic farms are not located in regions where most of the grain is cultivated. These farms often had difficulties in obtaining enough organic feed grain as well. The necessity to feed 100% organic fodder and the obligation to build free stall barns led to reversions especially for organic dairy farms, because they did not receive premium prices for their milkReference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37.

Macro environment

In several studies it was found that the macro environment of the farm poses difficulties, especially regarding production and marketing of organic products. Large organic processors in Denmark (e.g., mills) were too far away from the producers and did not accept small quantities, which resulted in farmers selling their produce to smaller, local conventional millsReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8, Reference Kaltoft and Risgaard32. Rigby et al.Reference Rigby, Young and Burton46 mentioned the same problem in the United Kingdom, where long distances to wholesalers and processors, like abattoirs or packers, proved to be a problem. SchmidReference Schmid31 found that good regional infrastructure for marketing organic products resulted in more organic farms in Austria, whereas in regions with poor infrastructure there were large numbers of reversions. Some farmers in the United Kingdom who reverted mentioned a general lack of demand for their organic productsReference Harris, Robinson, Griffiths and Robinson47. In Norway, especially vegetables were difficult to market locally at a premiumReference Koesling, Loes, Flaten and Lien37.

In Denmark, the scarcity of agricultural land sometimes resulted in reversion. When farmers wanted to grow and intended to increase their herd size, they needed access to more land. In cases where it was not possible to expand, the decision was between staying organic without increasing herd size or growing and reverting to conventional production, because the existing acreage was not sufficient to fulfill the organic regulations or to produce enough organic fodderReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8.

Conclusions

Although several studies with the focus on organic farmers reverting to conventional agriculture already exist, there is still a lack of knowledge regarding this phenomenon. As it appears, there is neither a uniform pattern of steady increase or decrease in the number of organic farms per country, nor certain years in which large-scale deregistration occurred in several countries simultaneously. It would be of great interest to divulge the reasons behind different phenomena in the respective countries or via a cross-country research project.

Obviously, the farmers’ reasons for reversion depend on the specific situation in each country. Nevertheless, there are many similarities and common reasons for reverting to conventional agriculture. In general, the literature review gives the impression of unmet expectations in several fields. Apparently, the farmers’ expectations regarding economic performance, implications of the certification and control system as well as the adoption of organic management techniques may differ considerably from reality. More research is needed to explore whether better preparation and more information on various aspects of organic farming and marketing before conversion could contribute to lower reversion rates and the form in which this information should be communicated.

Although the final causes for reversion are manifold and most farmers stated a combination of reasons for reversion, the literature review shows that economic problems are the crucial factor in most cases. If frustration with the economic performance of organic management is the main reason for reversion, it seems likely that for these farmers economic motives played a major role in the decision to convert to organic farming as well. It remains to be investigated whether the farmers who claim to have converted mainly out of other, non-economic motivations (see Table 3), are more likely to continue organic farming despite economic difficulties.

Likewise, an analysis of the utility of converting to organic farming and reverting to conventional farming in relation to economic aspects would give further insights into the decision-making process. Hence, it could be determined whether the decision to revert is mainly due to unmet economic expectations or appears to be an economic necessity in order to maintain the farming business. To this effect, an objective evaluation of the economic situation of organic and reverted farms and their actual market environment (regarding marketing, processing, prices, subsidies, etc.) presents a possibility for further researchReference Lampkin, Foster and Padel51–Reference Gerrard and Padel55.

Another frequently mentioned difficulty apparently was the problematic and interfering bureaucracy which farmers encounter with organic certificationReference Padel56. Considering that many reverted farmers plan to continue using organic farming methods without certification, which subsequently results in not being able to market their products as organic products and therefore not receiving premium prices or organic subsidiesReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10, the burden farmers associate with documentation and control should not be underestimated. Legislation bodies and certification organizations should contemplate measures regarding bureaucratic redtape which may help reduce or at least simplify the procedures involved.

The theoretical model suggests that an evaluation of the possible future utility of organic and conventional management also contributes to the decision to revert. In this context, the role of private or official advisory services becomes apparent. It needs to be further investigated to what extent professional consultation and guidance could influence and improve the future prospects of organic management. As already mentioned by Reissig et al.Reference Reissig, Ferjani and Mann42, control on organic farms could not only be used to critically supervise farming practices but also establish better contact and offer support and suggestions for improvement.

The institutions concerned with organic legislations should also ensure stable and predictable regulations for the futureReference Ferjani, Reissig and Mann45. The uncertainty that farmers associate with organic regulations leads to a higher risk perception regarding future organic management compared with the conventional alternative. Any changes should therefore be announced in advance to enable the farmers to implement the changes, especially in cases when considerable investments are required (e.g., regarding animal husbandry).

Access to land is another important key issue, which will have an increasing impact on the relative utility of organic management in the future. In the past few years, high prices of land tenure (as a result of high prices for energy crops) were an impediment for organic farmers to develop their farms in GermanyReference Sanders, Offermann and Nieberg57 as well as in other countries as wellReference Kaltoft, Risgaard and Holt8. The energy farmers are capable of paying much higher prices and might easily outplay the organic farmers when it comes to land tenure. If an investment into the production of renewable energies is economically much more promising than organic production, farmers might be tempted to revert to conventional agriculture and to turn to production of energy crops instead. As long as there is heavy governmental support for renewable energy sources, resulting in a much higher expected utility of conventional farming compared with organic farming, this might be counterproductive for the expansion of organic agriculture.

Considering the attempts of many governments to support the expansion of organic farming area by offering attractive subsidies for conversion, and considering the large dropout rates in many countries, it seems promising to take measures to prevent organic farmers from reverting rather than merely trying to recruit new onesReference Flaten, Lien, Koesling and Løes10. More knowledge is necessary to ascertain why farmers’ expectations are not fulfilled, especially with regard to the loss of transaction costs for first converting to organic and later reverting to conventional agriculture. More research is also needed regarding the consequences of possible negative impact of the word of mouth communication of reverted farmers on the image of organic farming and the effects of reverting farmers on other organic farmers. Besides, discontented organic farmers might prevent conventional farmers from converting to organic farming techniques.

Apparently, the farmers’ decision to convert to organic farming is not necessarily a ‘fundamental’ one-way decisionReference Padel16, Reference Midmore, Padel, McCalman, Isherwood, Fowler and Lampkin58, but a decision that might be put into question after some years. A comparison between organic farmers deciding to remain organic and farmers choosing to revert with respect to the farms’ economic, infrastructural and other relevant circumstances, would give further indications of the critical success factors. A deeper understanding of the influencing factors and changes that are necessary for farmers to remain organic should be an important objective for on-going research. The information could be gained by qualitative research methods such as focus group discussions and expert interviews with representatives of farmers’ organizations and advisory services.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this research provided by the Federal Institute for Agriculture and Food (BLE) on behalf of the German Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (BMELV). We also appreciate many helpful comments and suggestions that we received from the reviewers on an earlier version of this manuscript.