Introduction

Both patients and members of the public are increasingly involved in many domains of the healthcare system, including health technology assessment (HTA) (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1–Reference Whitty4). Patient and public involvement (PPI) in HTA has emerged as an imperative for more informed, transparent, accountable, and legitimate decisions about health technologies (Reference Abelson, Giacomini, Lehoux and Gauvin5–Reference Gauvin, Abelson and Lavis9). In recent years, several efforts have been initiated around the world to achieve PPI in HTA (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10–Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12). The rationale behind patient involvement in HTA is that patients—referring to individuals with personal experience of a health issue and their informal caregivers, including family and friends (13)—can give their perspectives on experiences, attitudes, beliefs, values, and expectations about health, illness, its effects, and the use of health technologies (Reference Facey, Boivin, Gracia, Hansen, Scalzo and Mossman6;Reference Pivik, Rode and Ward14). Thus, patient involvement in HTA should help produce care that is responsive to their needs and values (15;16). Along with providing experiential knowledge, it is believed that involving patients in health decision making will promote a sense of empowerment and contribute to more efficient solutions regarding the distribution of scarce health resources (Reference Pivik, Rode and Ward14–Reference Segal17). Therefore, patient involvement in HTA allows considering their needs and values in decisions regarding health technologies, which could increase their relevance (18).

Abelson and collaborators (Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12) highlight the principal reasons for involving the public—referring broadly to citizens and patients—in HTA, including: (i) to gain public support for funding the work of HTA agencies (Reference Drummond, Tarricone and Torbica19;Reference Menon and Stafinski20); (ii) to ensure that the assessment adopts a broader health condition perspective, rather than the narrower technology perspective characteristic of more traditional HTAs (Reference Menon and Stafinski20); (iii) to avoid potential conflicts between individual patient interests with the desire to distribute resources fairly (Reference Menon and Stafinski20); and (iv) to provide context for the research, which improves the usefulness of assessments for decision makers (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Lepage-Savary, Gagnon, St-Pierre and Rhainds7).

Despite the general consensus on the need to involve patients and the public in HTA, questions remain about the best strategies for involving them into the structures and activities of HTA agencies and hospital-based HTA units (Reference Facey and Hansen21;Reference Moran and Davidson22). In 2011, Gagnon and collaborators (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Lepage-Savary, Gagnon, St-Pierre and Rhainds7) published a systematic review aiming to describe international experiences of PPI in HTA. As this field has rapidly evolved in recent years, decision makers and researchers need more recent evidence on the impact of PPI in HTA (Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23). Hence, this paper aims to synthesize knowledge on how patients and the public have been involved in HTA activities over the last decade and to propose a framework to assess the impact of PPI in HTA.

Conceptual Framework

We used a framework developed by our team (Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Légaré, Piron and Gagnon24) to organize data collection and analysis regarding PPI in HTA (Figure 1). This framework is presented as a logic model, which is a visual illustration of a program's resources, activities, and expected outcomes. The framework has three main components: (i) resources (inputs), activities, and results (outputs); (ii) evaluation criteria of PPI issued from general frameworks for evaluating PPI (Reference Rowe and Frewer25;Reference Rowe, Marsh and Frewer26) and our initial systematic review of PPI in HTA; and (iii)contextual factors as highlighted by Abelson and colleagues (Reference Abelson, Montesanti, Li, Gauvin and Martin27). This framework allows looking at the relationship between the process and the outcomes of PPI in HTA and the influence of the context in which this involvement takes place.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework to evaluate patient and public involvement (PPI) in health technology assessment (HTA).

We used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman28) guidelines to perform and report this systematic review (See PRISMA checklist in the Supplementary material).

Methods

Search Strategy

We undertook a literature search in the following databases: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of science, and Business Source Premier, covering 1 March 2009 (the date of the last search in the previous review) to 31 December 2019 using the following concepts: “HTA”; “INAHTA”; “Public involvement”; “Patient Satisfaction/Education/Preferences”; “Patient-Centered Care/Shared decision making/Professional-Patient Relations” (See Supplementary material for the PubMed full electronic search strategy). Relevant references from studies selected for extraction were followed up and obtained for assessment. We also contacted three authors for which study abstracts were available for potentially eligible published or unpublished studies. Other literature was identified through discussion with experts in the field through contacts of the team members.

Study Selection

We used the following inclusion and exclusion criteria, based on those used for the initial systematic review:

Type of studies: Only papers describing qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods empirical research were included. Editorials, commentaries, as well as opinion articles were excluded.

Types of participants: We included patients, consumers, service users, informal caregivers, public, citizens, and all similar terms in order to be as inclusive as possible, given the lack of terminology consensus about these terms. However, we used either patient, informal caregiver, or member of the public when describing the population of interest to avoid confusion.

Types of interventions: The study had to describe, in whole or in part, any experience of patient or public involvement practice in the field of HTA. We did not include studies that were related to PPI in general, such as surveys of PPI among HTA agencies. The interventions of interest in this review are PPI activities. Thus, when more than one publication reported a same study involving the same participants and presenting the same PPI activities, we included only the most recent publication. However, if different participants and/or different PPI activities were described in publications related to a same study, we included all relevant publications.

Data Collection Process

First, one reviewer (MTD) screened titles. Then, pairs of two reviewers (MPG and MTD; MPG and GM) independently screened abstracts for possible inclusion in the review. After a first selection of potentially relevant articles, full copies of these papers were retrieved and allocated to two reviewers among all authors (MPG, MTD, TGP, JPG, GM, and VB) who screened them independently, using the set of inclusion criteria. We ensured that papers written by some of the authors (MPG, MTD, and TGP) were reviewed by other authors without conflict of interests or by a research associate not involved in the publication (AL, see Acknowledgments).

Data Extraction

We used the template developed for our initial systematic review to extract information. We extracted information on the type of patient or public involvement in HTA, based on Gauvin's model (Reference Gauvin, Abelson, Giacomini, Eyles and Lavis29), information about factors facilitating or limiting patient participation, and impact on clinical interventions, costs, and perceptions of other stakeholders. We further enriched this template by adding attributes related to the type of participants, information related to the context of involvement, and short-term results. For each retained study, data extraction was done independently by two reviewers among all authors (MPG, MTD, TGP, JPG, GM, and VB), and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion during a meeting involving all reviewers.

We extracted study characteristics including: country of the study, year and language, main objective, methodological approach, study design, and data collection strategy. Study description included: the type of technology (nature, life cycle), the domain/type and the stage of involvement, the level of involvement, and the use of a theoretical model. The type of participants included: members of the public, patients, and other stakeholders (e.g., decision makers, healthcare providers, HTA staff, etc.). We also extracted the main findings of the studies. The outcomes of interest were the documented impact of PPI on the HTA process and recommendations, as well as the barriers and facilitators to PPI.

Quality Assessment

We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to assess the quality of studies for this update (Reference Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths and Johnson-Lafleur30). We used this tool because, to the best of our knowledge, it is the only one that allows to concomitantly appraise the methodological quality of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies, using a valid and usable specific set of criteria.

Results

Study Selection

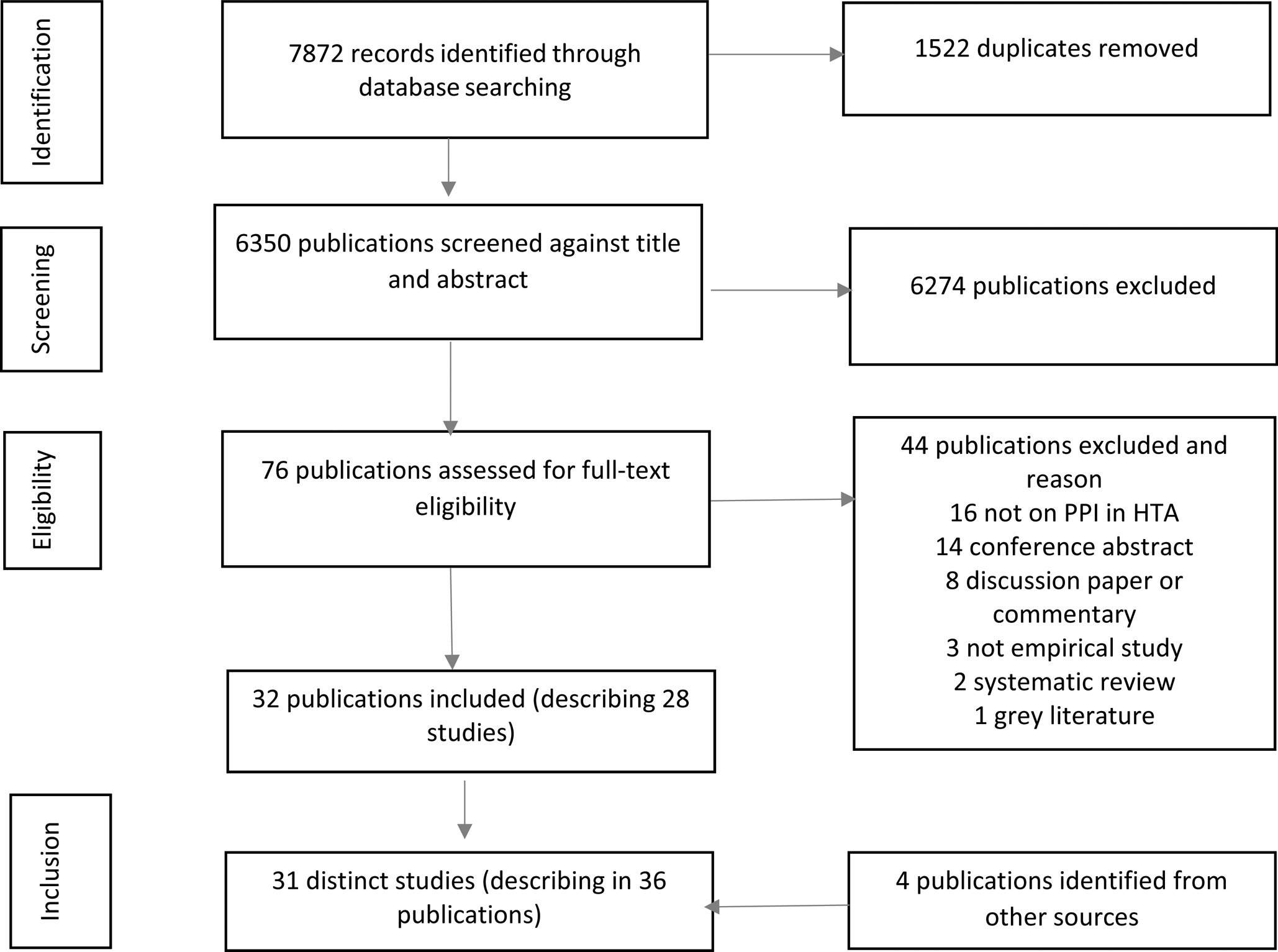

A total of 7872 records were identified by the main search strategy. Of these, thirty-two publications (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Légaré, Piron and Gagnon24;Reference Brereton, Ingleton, Gardiner, Goyder, Mozygemba and Lysdahl31–Reference Bae, Hong, Kwon, Jang, Lee and Bae57), referring to twenty-eight studies, met the inclusion criteria. Discussions with experts in the field and follow-up of relevant references from studies selected allowed us to identify four more publications (Reference Brereton, Wahlster, Mozygemba, Lysdahl, Burns and Polus58–Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard61). This yielded the inclusion of a total of thirty-one distinct studies, described in thirty-six publications. The study selection process is outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram. PPI, patient and public involvement; HTA, health technology assessment.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Study characteristics are presented in Table 1. A large number of included studies (12/32) were conducted in Canada (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Légaré, Piron and Gagnon24;Reference Boothe33;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;42;43;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50;Reference Poder, Carrier and Bédard51;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60), followed by Australia (4/32) (Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47;Reference Whitty, Ratcliffe, Chen and Scuffham55;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60), Italy (3/32) (Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Gillespie40;Reference Lo Scalzo, Abraha, Bonomo, Chiarolla, Migliore and Paone48), England (3/32) (Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Moreira49;Reference Simpson, Cook and Miles53), Germany (2/32) (Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Danner, Hummel, Volz, van Manen, Wiegard and Dintsios35), and Finland (2/32) (Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46). The remaining studies were conducted in Austria (Reference Ettinger, Mayer, Stanak and Wild36), Ireland (Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52), Scotland (Reference Kelly, Fearns and Heller-Murphy45), South Korea (Reference Bae, Hong, Kwon, Jang, Lee and Bae57), Spain (Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44), and one from more than one country (Reference Brereton, Ingleton, Gardiner, Goyder, Mozygemba and Lysdahl31).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

The following results are presented according to the categories of our analytical framework and cover: (i) the types of resources mobilized; (ii) the types of involvement activities; (iii) the types of patient or public involved; (iv) the short-term results of PPI; and (v) the barriers and facilitators to PPI.

Types of Resources Mobilized for Patient or Public Involvement

Resources mobilized for PPI included information resources in almost all of the included studies (see Table 1). Other studies described time resources (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Gillespie40;Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Lo Scalzo, Abraha, Bonomo, Chiarolla, Migliore and Paone48;Reference Poder, Carrier and Bédard51;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59), material resources such as computers, meeting rooms and office supplies (Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Moreira49;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59), human resources (Reference Bombard, Abelson, Simeonov and Gauvin32–Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46–Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Legare, Piron and Gagnon54;Reference Whitty, Ratcliffe, Chen and Scuffham55;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard61), and financial resources (Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Moreira49;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard61).

Specific human resources were dedicated for PPI in the majority of studies (17/32). Six studies (Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Moreira49;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59) reported the use of material resources, and only four studies (Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Moreira49;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard61) reported the use of financial resources. With respect to informational resources, written information such as evidence brief (Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12), e-mail invitation (Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59), and draft of the recommendations (Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46) were the most used. Staff for the provision of care (Reference Moreira49), support person (Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Legare, Piron and Gagnon54), patient recruiter (Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52), and discussion facilitator (Reference Bombard, Abelson, Simeonov and Gauvin32;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard61) were reported as human resources.

Types of Patient or Public Involvement Activities

The studies reported two main types of patient or public involvement in HTA activities. In the first type, participants give their view on the topic under study (draft of HTA recommendations, a framework or a test, etc.) (Reference Brereton, Ingleton, Gardiner, Goyder, Mozygemba and Lysdahl31–Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Ettinger, Mayer, Stanak and Wild36;42–Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44;Reference Moreira49;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50;Reference Whitty, Ratcliffe, Chen and Scuffham55;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59). In the second type, they are directly involved in different stages of the HTA process, often at the same table with other stakeholders in working groups, and/or participants receive information about the HTA being conducted (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Bombard, Abelson, Simeonov and Gauvin32;Reference Danner, Hummel, Volz, van Manen, Wiegard and Dintsios35;Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39–Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46–Reference Lo Scalzo, Abraha, Bonomo, Chiarolla, Migliore and Paone48;Reference Poder, Carrier and Bédard51;Reference Simpson, Cook and Miles53;Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Legare, Piron and Gagnon54;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60).

Type of Patient or Public Involved

All studies reported the total number of participants, but the number per group was not clear in three studies (Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Moreira49;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52). This number varied from 4 to 949. Five studies included the participation of members of the public only (Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12;Reference Bombard, Abelson, Simeonov and Gauvin32;Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60), fourteen studies included the participation of patients only (Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Brereton, Ingleton, Gardiner, Goyder, Mozygemba and Lysdahl31;Reference Danner, Hummel, Volz, van Manen, Wiegard and Dintsios35–Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Gillespie40;42;43;Reference Kelly, Fearns and Heller-Murphy45;Reference Lo Scalzo, Abraha, Bonomo, Chiarolla, Migliore and Paone48–Reference Poder, Carrier and Bédard51;Reference Simpson, Cook and Miles53), whereas both members of the public and patients were involved in twelve studies (Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Boothe33;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Legare, Piron and Gagnon54;Reference Bae, Hong, Kwon, Jang, Lee and Bae57;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59).

The involvement of other stakeholder groups such as healthcare professionals and managers was also mentioned in ten studies (Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Boothe33;Reference Danner, Hummel, Volz, van Manen, Wiegard and Dintsios35;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50–Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52).

Short-Term Results of Patient or Public Involvement

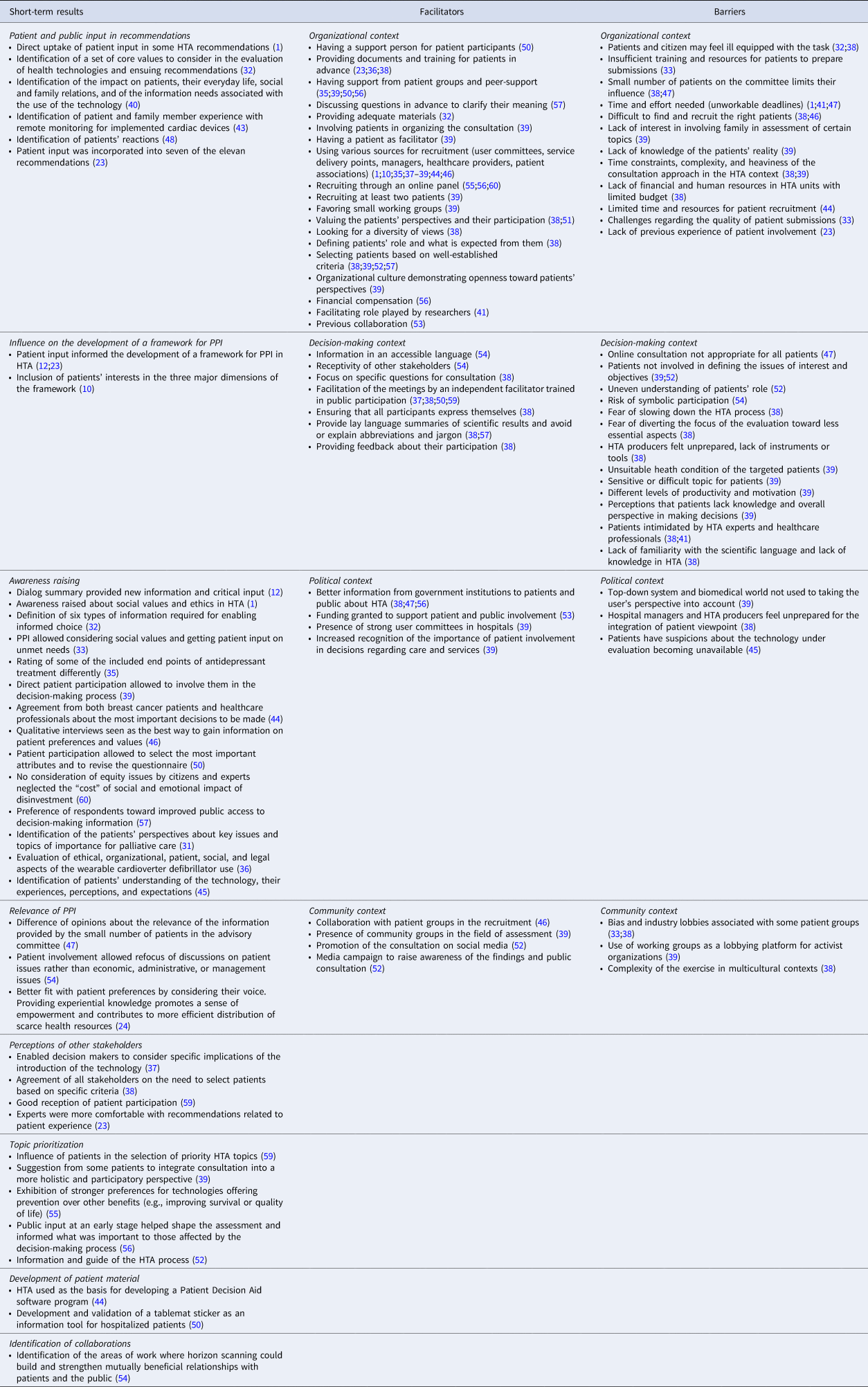

In this review, we focused on short-term results that are those obtained within 1–3 years after the intervention. Five studies reported the input of PPI in HTA recommendations (Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Bombard, Abelson, Simeonov and Gauvin32;Reference Boothe33;Reference Gillespie40;Reference Lo Scalzo, Abraha, Bonomo, Chiarolla, Migliore and Paone48), whereas three studies reported this input in the development of a framework for PPI (Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23). Several studies (15/32) reported awareness raising in decision making at different stages of the HTA process following PPI (Reference Abelson, Wagner, DeJean, Boesveld, Gauvin and Bean12;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Brereton, Ingleton, Gardiner, Goyder, Mozygemba and Lysdahl31–Reference Boothe33;Reference Danner, Hummel, Volz, van Manen, Wiegard and Dintsios35;Reference Ettinger, Mayer, Stanak and Wild36;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Kelly, Fearns and Heller-Murphy45;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Moreira49;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50;Reference Bae, Hong, Kwon, Jang, Lee and Bae57;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60). Two studies discussed the relevance of PPI activities (Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Légaré, Piron and Gagnon24;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47), and five studies analyzed the perceptions of stakeholders regarding patient involvement (Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Boothe33;Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59). Among other impacts, five studies reported the influence of patients at different stages of the HTA process (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Whitty, Ratcliffe, Chen and Scuffham55;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Gagnon, Wale, Wong-Rieger and McGowan59), one study reported the development of a software program (Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44), another study led to the development and validation of a tablemat sticker (Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50), and one study identified possible collaborations (Reference Simpson, Cook and Miles53). These results are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Examples of short-term results, barriers and facilitators related to PPI in HTA

Barriers and Facilitators to PPI in HTA

Among the thirty-two included studies, twenty-six reported data on barriers and facilitators. Table 2 presents the examples of the barriers and facilitators that were reported, according to the context in which they were identified (organizational, decision making, political, and community).

The two barriers most often cited were related to the organizational context (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47). For example, three studies reported the difficulty to find and recruit the right patient interested by the topic and available (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46), and three others argued that the time and efforts needed could represent a barrier for PPI activities (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47). Other barriers were related to the political and community contexts, such as the fear that patient groups could act as lobbyists for the industry (Reference Boothe33;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39), and the lack of preparedness for healthcare professionals and managers for including the patient perspective (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39).

We also identified four main facilitators of PPI reported in the studies. Half of them were related to the organizational context (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Brereton, Ingleton, Gardiner, Goyder, Mozygemba and Lysdahl31;Reference Boothe33;Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Danner, Hummel, Volz, van Manen, Wiegard and Dintsios35;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Hämeen-Anttila, Komulainen, Enlund, Mäkelä, Mäkinen and Rannanheimo41;Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Simpson, Cook and Miles53;Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Legare, Piron and Gagnon54). For instance, ten studies reported varied sources of recruitment (user committees or patient associations, service delivery points, managers, healthcare providers, research networks) to facilitate participant enrolment in the HTA process (Reference Abelson, Bombard, Gauvin, Simeonov and Boesveld1;Reference Bastian, Scheibler, Knelangen, Zschorlich, Nasser and Waltering10;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23;Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Izquierdo, Gracia, Guerra, Blasco and Andradas44;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Poder, Carrier and Bédard51). The two other facilitators were related to the decision-making context (Reference Fratte, Passerini, Vivori, Dalla Palma and Guarrera37;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47;Reference Poder, Beffarat, Benkhalti, Ladouceur and Dagenais50;Reference Poder, Carrier and Bédard51;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56;Reference Street, Callaghan, Braunack-Mayer and Hiller60). Regarding the political context, better information targeting patients and the public about HTA from governmental institutions appears as a facilitator for PPI in four studies (Reference Boothe33;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56). Finally, four studies identified facilitators in the community context (Reference Cockcroft, Britten, Long and Liabo34;Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Rhainds and Coulombe39;Reference Kleme, Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, Airaksinen, Enlund, Kastarinen and Peura46;Reference Ryan, Moran, Harrington, Murphy, O'Neill and Whelan52), such as the collaboration of patient associations and community groups in the recruitment, and the use of social media.

Discussion

Involving patients and the public in HTA is now recognized as a way to ensure that the evaluation is made on issues of importance to patients, thus improving the relevance and the quality of decisions (Reference Poder, Safyanik, Fournier, Ganache, Pomey and Gagnon62). We found several experiences of PPI in HTA documented in the literature over the last decade (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Lepage-Savary, Gagnon, St-Pierre and Rhainds7).

The majority of studies found in this update are from Canada, Australia, and Italy. In the previous review, the UK and the U.S. were the most represented countries (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Lepage-Savary, Gagnon, St-Pierre and Rhainds7). Additionally, this review found an example of PPI in HTA from an emerging country (South Korea) (Reference Bae, Hong, Kwon, Jang, Lee and Bae57).

Consistent with the previous review, the two main forms of PPI in HTA are when patients and the public are consulted to collect their perspectives to inform HTA or when they directly participate in the HTA process (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Lepage-Savary, Gagnon, St-Pierre and Rhainds7). As we found previously, patients and the public are still mostly consulted than directly involved in the HTA process. As underlined in our previous work, this may be due to a lack of guidance for HTA producers to integrate patients and members of the public into their work processes (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Poder, Safyanik, Fournier, Ganache, Pomey and Gagnon62). Additionally, the commitment of different stakeholders, among which governments and community organizations, is needed in order to facilitate PPI in HTA. This review highlighted some facilitators and barriers to PPI related to the wider political and community context. For instance, the need to inform the general public about HTA is recognized by several authors as a potential lever to facilitate PPI in HTA (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Gagnon, St-Pierre, Gauvin and Rhainds38;Reference Lopes, Street, Carter and Merlin47;Reference Wortley, Tong and Howard56). Providing clear guidance and policies to support PPI in HTA, including a recognition of the investments it needs in terms of time, human, and material resources, will also facilitate its integration into practices.

This review is in line with previous studies, suggesting that there is evidence that PPI impacts the HTA process in several ways, but structured methods to perform PPI evaluation are lacking (Reference Gagnon, Desmartis, Lepage-Savary, Gagnon, St-Pierre and Rhainds7). Evaluating the impact of PPI in HTA remains a major methodological challenge because of the various dimensions that should be considered (Reference Facey, Bedlington, Berglas, Bertelsen, Single and Thomas2;Reference Pomey, Brouillard, Ganache, Lambert, Boothroyd and Collette23).

In this review, we applied an evaluation framework (Reference Tantchou Dipankui, Gagnon, Desmartis, Légaré, Piron and Gagnon24) in order to map the context of involvement when considering different components that affect PPI in an integrated way. Using this framework made it possible to better organize the types of impacts that could be related to PPI in HTA. Thus, our results support the applicability of this framework to evaluate PPI in HTA. We were rather able to highlight the short-term results of PPI that are described in most of the studies, but also some long-term results such as those reported in the study by Moreira on the history of patient involvement in the Alzheimer Society in the UK, which allowed an assessment of the impact of involvement over time (Reference Moreira49). The fact that most studies discussed short-term results of PPI in HTA can be explained by the relative novelty of this practice. With the practice of PPI in HTA becoming mainstream, it will be possible to better measure the medium- and long-term impacts of involvement on several dimensions and, ultimately, to gather stronger evidence on its benefits. To do so, we recommend that HTA bodies that are implementing PPI make sure that they document their process based on an evaluation framework and make their results available to others. The use of the GRIPP checklist (Reference Staniszewska, Brett, Mockford and Barber63) should be encouraged for reporting PPI in HTA but also when designing these activities.

The main contribution of this systematic review is twofold. First, this update shows that PPI is growing in the field of HTA and expanding to several countries. However, strong evidence on the impact of PPI, especially on the long term, is lacking. It is important that studies evaluate the impact of PPI in HTA in a robust manner, using appropriate frameworks, and disseminate their findings. Second, this review confirms the applicability of our evaluation framework to map the different components affecting PPI in an integrated way. Using this framework, it was possible to highlight the short-term results of PPI reported in the included studies, but also to foresee impacts that may happen over a longer period of time, when PPI practice in HTA is more common and institutionalized. We, thus, recommend further validation of the proposed framework by using it to guide the evaluation of PPI in HTA.

Study Limitations

This updated systematic review has some limitations. First, we made the choice to report only the findings from the most recent studies (published since 2009) in this review. As the field of PPI in HTA evolves rapidly, earlier experiences of PPI could be less informative in the actual context. Second, we did not specifically search for studies published in the grey literature, apart from those referenced in included studies. Thus, it is likely that many PPI experiences reported in HTA reports have not been captured. However, considering the large body of HTA reports published around the world in several languages would be very demanding. Additionally, we did not formally consult international experts in the field, but this was done informally through our contact network and at HTA meetings. Consequently, some valuable international studies may have been overlooked. Third, despite the fact that we assessed study quality based on the MMAT tool (Reference Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths and Johnson-Lafleur30), it has not been considered when interpreting the results. As the aim of this review was to get a broad overview of PPI in HTA, we decided to keep all studies in the analysis. This limitation opens avenues for further research that could consider the quality of evidence in the interpretation of the results.

Fourth, although we included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies, we did not explore the quantitative impact of PPI in this review. The use of experimental designs to assess the effectiveness of PPI is still very limited; thus, it is not possible to provide quantitative estimations such as effect size. Given the limited quantitative data available, a narrative synthesis was deemed more appropriate to answer the review question. However, further research could use relevant metrics to provide quantitative evidence in this field.

Finally, we did not directly seek the input of patients or members of the public in this review. This is an important limitation because we lack their perspective regarding what are the important outcomes of PPI in HTA. Future primary studies and reviews about the impact of PPI in HTA should involve patients and the public in their design to ensure that all important outcomes are captured.

Conclusions

The number of published studies on PPI in HTA has increased over the last years, but few of these experiences reported their impacts. It is essential to pursue the development of best practices and guidelines for PPI in HTA, to report PPI experiences using the GRIPP checklist, and to ensure rigorous evaluation in order to highlight its impact on the HTA process, recommendations, and outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462321000064.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a planning and dissemination grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; grant #PHS354915). MPG holds the Canada Research Chair in Technologies and Practices in Health. TGP is a member of the FRQS-funded Centre de recherche de l'IUSMM and a fellow of the FRQS. We acknowledge the contribution of Ms. Amélie Lampron in data analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by a planning and dissemination grant from the CanadianInstitutes of Health Research (CIHR; grant #PHS354915). MPG holds the CanadaResearch Chair in Technologies and Practices in Health. TGP is member of theFRQS-funded Centre de recherche de l’IUSMM and fellow of the FRQS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.