Introduction

Many studies have documented changes in marriage patterns among Africans in South Africa in recent decades, specifically an increase in age at first marriage and a decline in marriage rates (see Garenne et al. Reference Garenne2001; Hunter Reference Hunter, Richter and Morrell2006; Kalule-Sabiti et al. Reference Kalule-Sabiti, Amoateng and Heaton2007; Hosegood et al. Reference Hosegood, McGrath and Moultrie2009; Posel & Casale Reference Posel and Casale2013). These trends are particularly pronounced among isiZulu-speakers who live mostly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. In this article we investigate links between a distinguishing feature of African marriage, the custom of bridewealth, and these marriage outcomes, drawing from both quantitative and qualitative data. We focus specifically on the practice of bridewealth in contemporary Zulu society.

The custom involving the provision of marriage payments, in cattle or cash, from the groom’s family to the parents of the bride is widely practiced in southern Africa and has various names among African language speakers: ilobolo in Zulu, roora in Shona, and bohali in Sesotho. Historically the practice was an essential part of marriage negotiations and the wedding itself, and was known to retain significance for the duration of the marriage. Evans-Prichard (1931:36) suggested the term “bridewealth” in order to avoid the implication that ilobolo was a matter of wife purchase and to recognize that the practice served to transfer wealth between families and generations. This term has become widely accepted, and we employ it interchangeably with the isiZulu term ilobolo.

Structural similarities exist among different bridewealth systems, but each ethnic group has its own culturally idiosyncratic practices specific to local conditions (see Kuper Reference Kuper1982; Gluckman Reference Gluckman and Radcliffe-Brown1950; Vilakazi Reference Vilakazi1962; Guy Reference Guy and Walker1990). In South Africa, it was only in the former colony of Natal (now incorporated into the province of KwaZulu-Natal and home to the majority of Zulu people in South Africa) that the payment of ilobolo was formalized. The payment, as determined by the Natal Secretary for Native Affairs Theophilus Shepstone in 1869, was ten cattle for the daughters of commoners (plus the ingquthu beast for the mother), fifteen for the daughters of brothers and sons of a hereditary chief, twenty for the daughters of an appointed chief, and no limit for the daughters of a hereditary chief (Welsh Reference Welsh1971:83).Footnote 1 The payment of ilobolo was later codified when the first version of the Natal Code of Zulu Law was promulgated in 1878 and later revised in 1891 (South African Law Commission 1997). Most noteworthy in this context is the provision that ten cattle had to be delivered on or before the day of the marriage.

This article makes use of a combination of quantitative and qualitative data to explore the relationship between contemporary bridewealth practices and marriage outcomes among African adults, specifically isiZulu-speakers. The quantitative data, which are in the public domain, were collected from large and representative household surveys conducted regularly between 1995 and 2008 by the official statistical agency in South Africa (Statistics South Africa) and by the Southern African Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU), as well as from a survey of social attitudes among South African adults conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council in 2005. Qualitative data were drawn from in-depth interviews conducted with forty Zulu respondents in order to determine how the custom of ilobolo is valued, whether it has changed over time, and the relationship between ilobolo and marriage outcomes.

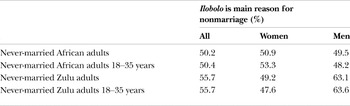

Although African marriage rates are low and falling, most noticeably among isiZulu-speaking adults, the quantitative data show no evidence of low marriage aspirations. Rather, half of the never-married respondents and 60 percent of isiZulu-speaking male respondents identified ilobolo as an impediment to marriage, with many seeing this as the principal way in which ilobolo had changed in recent years.

We do not argue that ilobolo is the only reason that most Zulu people stay unmarried. However, our qualitative data demonstrate that frequently the way ilobolo is practiced, and particularly the amount that is requested relative to men’s opportunities in the South African labor market, can contribute to delayed marriage and nonmarriage. At the same time, our interviews affirm that the custom remains widely endorsed in contemporary Zulu society, even among those who acknowledge a commercialization of the practice and who recognize that the need to pay ilobolo may reduce the likelihood of marriage. We argue that it is precisely because the custom is so highly valued and observed that large marriage payments would inhibit marriage.

Marriage Decline and Ilobolo

Historically, nonmarriage among Africans in South Africa seems to have been rare (Preston-Whyte Reference Preston-Whyte, Krige and Comaroff1981), and marriage typically took place early (Garenne et al. Reference Garenne2001). However, at least since the 1960s and particularly in recent decades, both a falling marriage rate and an increase in age at first marriage have been noted and discussed in a number of studies, as the coverage of the population census has increased and as more comprehensive sources of demographic microdata have become available (Garenne et al. Reference Garenne2001; Hunter Reference Hunter, Richter and Morrell2006, Reference Hunter2010; Kalule-Sabiti et al. Reference Kalule-Sabiti, Amoateng and Heaton2007; Hosegood et al. Reference Hosegood, McGrath and Moultrie2009; Posel & Casale Reference Posel and Casale2013).Footnote 2 These microdata reflect self-reported measures of marriage and therefore capture all forms of marriage, including customary and civil weddings.

Although this article focuses on the effects of bridewealth practices, the falling marriage rates cannot be attributed only to this factor. Among the several reasons offered for the decline, a key explanation concerns the ravaging effects of apartheid policies on family structure. At the same time as Africans, and men in particular, were pulled and pushed into mining and other industrial employment, their settlement at places of work was restricted (Mayer & Mayer Reference Mayer and Mayer1974; Nattrass Reference Nattrass1976; Beinart Reference Beinart and Mayer1980). Migrants frequently were housed in single-sex hostels, and influx control regulations limited the possibility that partners could migrate, leading to prolonged periods of separation between couples and an undermining of long-term relationships (Hunter Reference Hunter, Richter and Morrell2006). In her research on ilobolo practices among Africans living and working in the Durban Metropolitan Area in the 1980s, De Haas found that the “single most important factor in delaying marriage . . . was the critical lack of accommodation in towns” (1987:41). Other factors that have been highlighted include rising levels of education and increased economic opportunities for African women, which may have reduced both the need and the desire to marry early, if at all (Garenne et al. Reference Garenne2001). It is also possible that in recent decades the HIV epidemic in South Africa has contributed to the fall in marriage rates, although this has not been explored in the literature (see Hosegood Reference Hosegood2009) and was not a subject discussed with our own interviewees.Footnote 3

However, several historical and anthropological studies have drawn a link between changes in ilobolo practices and changes in marriage. One of the key original functions of ilobolo was to compensate the bride’s family for the transfer of her productive and reproductive labor power to the family of her husband (Guy Reference Guy and Walker1990). This compensation was not intended to profit the woman’s family financially, but rather was embedded in the relations of reciprocity between the two kin groups (Steyn & Rip Reference Steyn and Rip1968). To signal the importance of marriage in creating kinship bonds that endured over time, ilobolo frequently was paid in installments, with an initial payment before marriage and subsequent payments after the birth of a child (Yates Reference Yates1932). Men typically were not expected to pay ilobolo using only their own resources, and they received help from their fathers who would contribute cattle from their herds. In “traditional” Zulu culture a man who could not afford ilobolo could also offer a symbolic payment of stones, with the agreement that the cattle paid for the marriage of the groom’s first daughter would belong to the father-in-law (Dlamini Reference Dlamini1994). In such a case, only one cow needed to be slaughtered as a symbol for the ancestors to accept the newly married couple.

With the advent of colonialism, the development of the migrant labor system and the extension of the money economy recast the generational basis of ilobolo (Welsh Reference Welsh1971; McClendon Reference McClendon1995; Hunter Reference Hunter2010). After 1846 the hut tax was introduced in Natal, forcing young men into migrant labor to maintain their fathers’ homestead by paying taxes. Furthermore, colonial land dispossessions diminished stock farming capacity, which resulted in the inability of fathers to provide ilobolo for their sons (Hunter Reference Hunter2010). At the same time, some fathers expected increasing ilobolo payments for their daughters, perhaps regarding ilobolo as a way out of poverty. During the first half of the 1800s, the number of cattle paid for ilobolo in Natal rarely exceeded five, but by the late 1860s fifty head of cattle were not unusual for a commoner’s daughter and a hundred for a woman of royal blood, making marriage an unattainable goal for many young Zulu men (Welsh Reference Welsh1971). The possibility for the “abuse” of ilobolo provides one explanation for Shepstone’s decision to formalize the payments (Dlamini Reference Dlamini1994).

The Natal Code in 1878 added a provision to Shepstone’s ruling specifying that all cattle be paid before or at the start of marriage. This requirement would have been expected to delay marriage until the total ilobolo amount had been saved, although the historical record suggests that this provision was not observed consistently. While some fathers insisted on full cattle payment before a wedding, others were willing to “lend” their daughters to suitors on receipt of some head of cattle; still others allowed ilobolo to represent a promise to pay sometime in the future (see Dlamini Reference Dlamini1994). Zulu men also introduced imvulamlomo (mouth-opener) ceremonies, whereby the groom would offer a token payment or bring a present for the father of the prospective bride in order to decrease the ilobolo amount to be paid (see Hunter Reference Hunter2010).

By the 1970s, according to research conducted by Moeno (Reference Moeno1977), the requirement of full payment before marriage still had not been commonly adopted in rural areas. But in towns and cities, where payment was now in cash rather than in cattle, there was a greater expectation that ilobolo had to be settled before marriage, and marriage therefore was often delayed. More contemporary research also suggests that ilobolo is seen increasingly as a practice that can delay or even prevent marriage. For example, in Shope’s interviews with six hundred rural African women, including women from KwaZulu-Natal, many “acknowledge[d] that it has become more difficult for men to secure the money for lobolo; it may take ten to 15 years” (2006:68).

Several studies also refer to the rising costs of ilobolo and a commercialization of the practice (Hosegood et al. Reference Hosegood, McGrath and Moultrie2009), particularly in KwaZulu-Natal.Footnote 4 In Burman and van der Werff’s Reference Burman and van der Werff1993 study, respondents, including isiZulu-speakers in KwaZulu-Natal, “described families as exploiting each other by making excessive demands” (1993:119). Shope (2006:68) argues that ilobolo now involves “an economic imperative,” with respondents indicating a tendency for families to use ilobolo for “material advancement.” Although national microdata on bridewealth payments over time are not available, data collected in the 1998 wave of the KwaZulu-Natal Income Dynamics Study (KIDS 1998) suggest that in KwaZulu-Natal the average real value paid between 1985 and 1998 was approximately R20,000, representing about thirteen times the average monthly real earnings of African men during that period (Casale & Posel Reference Casale and Posel2010).

Even if ilobolo payments have not risen considerably in real terms, men’s ability to afford ilobolo has fallen as the payment has become more of an individual responsibility and as unemployment rates have grown. De Haas (Reference De Haas1987) reports that in 1980‒81, of 291 men who married according to customary rites in the Durban magisterial district, only one received assistance from his father. The decline in paternal support is associated partly with the payment of ilobolo in money (rather than in cattle) and more recently, with changes in family formation (including the absence of fathers in many households).

Alongside this generational shift has been a decline in employment opportunities for young men. The increase in unemployment was particularly dramatic in the first decade after apartheid. From 1995 to 2003, for example, the number of unemployed African men and women in South Africa rose by over 4.2 million, while the number of Africans in employment increased by a far more modest 1.6 million jobs (Casale et al. Reference Casale, Muller and Posel2004:994).Footnote 5 Unemployment rates in KwaZulu-Natal are among the highest in South Africa. For all Africans in the country, the unemployment rate grew from 36.3 percent in 1995 to 49.5 percent in 2003; in KwaZulu-Natal specifically, the unemployment rate increased from 39.5 percent to 51 percent.Footnote 6 The rise in unemployment rates has also been marked among younger Africans (35 years or younger) of marriageable age (Kingdon & Knight 1997).

Following the dismantling of apartheid, legislation has brought increased access to education among Africans, raising the expectations of young African men to be the economic providers in the family. However, declining opportunities in the postapartheid labor market have compromised their ability to meet these expectations, leading to a “crisis of African masculinity” according to a number of scholars (Campbell Reference Campbell1992; Morrell Reference Morrell1998; Hunter Reference Hunter2004; Waetjen Reference Waetjen2006). In KwaZulu-Natal, part of this general predicament, according to Hunter (Reference Hunter, Richter and Morrell2006, Reference Hunter2007), and a contributing factor in low marriage rates, is men’s inability to pay ilobolo.

Another contributing factor has been a gradual dislodging of the links among ilobolo, marriage, and reproduction (Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, de Wet and Stadler2001; Garenne et al. Reference Garenne2001). Traditionally, in the event of a premarital pregnancy, the woman would marry the father of the child and the “rights” to the child, signified by the child’s clan name, would be transferred to the father’s descent group through ilobolo. As rates of premarital pregnancy have risen, however, men have been able to claim rights to children through the payment of inhlawulo (or damages) to the mother’s family (see Hunter Reference Hunter2010). The payment of inhlawulo does not grant the father the right to live with his child, but the cost of inhlawulo is considerably lower than the ilobolo payment, making it perhaps a more attractive option to men. Hunter’s research also suggests that young unmarried women today are more likely than women of previous generations to give their children the father’s clan name even without the payment of inhlawulo, perhaps with the assumption that they are better positioned in the long run to make claims on the father and his family.Footnote 7

Notwithstanding these changes, however, studies also document that the custom of ilobolo remains highly valued, even in urban areas. De Haas finds that ilobolo in Durban in the 1980s was “increasingly seen as the distinguishing mark of a black as opposed to a white marriage” (1987:50). This observation is corroborated by subsequent research, which documents the importance of ilobolo as a source of African identity and pride in both rural and urban contexts (Walker Reference Walker1992; Burman & van der Werff Reference Burman and van der Werff1993). Although comparative studies on bridewealth practices have not been conducted across the different ethnic groups in South Africa, there is evidence to suggest that the custom is particularly supported and observed among Zulu people. Burman and van der Werff for example, found that 70 percent of the Zulu respondents in their study expected the custom to survive in the future, compared to 50 percent or less of other respondents (Burman & van der Werff Reference Burman and van der Werff1993:117).

This literature therefore demonstrates the existence of two opposing trends. On the one hand, ilobolo has become more difficult to pay, related to a growing commercialization and individualization of the practice, as well as to high and rising rates of unemployment, particularly among younger adults. On the other hand, the importance of ilobolo in marriage is being reaffirmed as a marker of Africanness. This tension may be an important explanation for low African marriage rates, despite the reported desire of the majority of Africans to marry. Among isiZulu-speakers in particular, high rates of unemployment, and possibly even more widespread support for the custom, may be an important part of the explanation for why marriage rates in this population group are the lowest in the country.

Marriage Rates and Attitudes to Marriage and Ilobolo: Evidence from Quantitative Data

Among African adults (18 years and older) in South Africa, marriage is not the norm. Demographic microdata drawn from a range of representative household surveys suggest that Africans are less likely to be (or to have been) married than to have never married. Furthermore, there has been a clear decline in marriage rates from 1995 to 2008, the period over which comparable national data are available, with the percentage of “ever-married” people falling by ten percentage points to 38 percent in 2008 (see figure 1).Footnote 8

Figure 1. Percentage of “Ever-Married” African Adults

Sources: Stats SA (1995, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007); SALDRU (2008); authors’ calculations.

Note: The data have been weighted to represent population estimates. Adults are aged 18 years and older. “Ever-married” adults include those who are currently married as well as those who are divorced or widowed. Zulu adults cannot be distinguished from other ethnic groups in the 1995 data.

Among all the ethnic groups in South Africa, marriage rates are lowest among isiZulu-speakers.Footnote 9 By 2008, only three out of every ten Zulu adults were or had been married. Marriage rates are also considerably lower in urban areas, such that among Zulu urban dwellers only one out of every four Zulu adults was ever-married in 2008.Footnote 10 Marriage patterns among Africans are also distinctive because the age at which first marriages occur is much higher than for other populations. In 2008, for example, the percentage of non-Africans who were ever-married rose dramatically among twenty-five- to twenty-nine-year-olds (by over forty percentage points), whereas it increased far more modestly among Africans of the same age cohort, and by even less among Zulu adults specifically (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of “Ever-Married” Adults by Age, 2008

Sources: SALDRU (2008); authors’ calculations.

Note: The data have been weighted to represent population estimates.

Interestingly, the evidence for low and declining marital rates among African adults has not been accompanied by any apparent attitudinal or aspirational changes in regard to marriage. In the 2005 South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) (HSRC 2005), 81 percent of all never-married African adults either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statement, “I would like to get married someday.”Footnote 11 There was only a small gender difference but a somewhat larger age difference; among a younger cohort, ages eighteen to thirty-four years, the approval of marriage among never-married adults increased to 89 percent.Footnote 12 Very low marriage rates among Zulu adults specifically are also not reflected in attitudinal differences to marriage: never-married Zulu adults are as likely as all African adults to report wanting to marry (see table 1).

Table 1. Attitudes to Marriage among African Adults, South Africa, 2005

Sources: HSRC (2005); authors’ calculations.

Note: The data have been weighted to represent population estimates. Adults are aged 18 years and older.

Nor does the increased scope for cohabitation apparently explain the declining marriage rates. Available nationally representative microdata from 1995 to 2008 indicate that the percentage of African adults (18 years and older) who are cohabiting but not married increased more than twofold, although this was from a very low base of 4 percent. Cohabitation rates are higher in urban areas than in rural areas and have risen by more (to almost 13 percent), suggesting that there is greater freedom to form cohabiting relationships in an urban setting.Footnote 13 Nonetheless, data from the SASAS 2005 also indicate that for most unmarried African men and women cohabitation is not viewed as an acceptable alternative to marriage, both among urban dwellers (64 percent) and rural dwellers (65 percent) (Posel & Casale Reference Posel and Casale2013; see Posel & Rudwick Reference Posel and Rudwick2014 for further discussion on attitudes to cohabitation in the context of ilobolo).Footnote 14

By contrast, the issue of bridewealth, according to the quantitative data, is indeed a particularly salient factor in the decline of marriage. The 2005 SASAS included only one question on attitudes to ilobolo, in which respondents were asked to respond to the statement: “The payment of ilobolo is the main reason why people do not get married these days.” Because the statement limits ilobolo to “the main reason” for nonmarriage, responses may underestimate the importance of this factor.Footnote 15 Nonetheless, half of all never-married African adults either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statement. The percentage was higher among never-married Zulu adults, but particularly among Zulu men, more than 60 percent of whom identified ilobolo as the main reason for nonmarriage (see table 2).

Table 2. Ilobolo as the “Main Reason” for Nonmarriage: Attitudes among African Adults, 2005

Sources: HSRC (2005); authors’ calculations.

Note: The data have been weighted to represent population estimates. Adults are aged 18 years and older.

Available nationally representative quantitative data therefore describe high and increasing rates of nonmarriage among Africans, although the clear majority express positive marriage aspirations. In addition, Zulu male adults, in particular, view ilobolo as the main reason for nonmarriage. Since the 2005 SASAS did not ask precise or follow-up questions about ilobolo as a constraint to marriage, we conducted qualitative research to probe attitudes to ilobolo among Zulu adults and to investigate the possible relationship between ilobolo and low marriage rates.

Attitudes to Marriage and Ilobolo: Evidence from Qualitative Data

The most recent in-depth qualitative study on ilobolo with a focus on the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal (De Haas Reference De Haas1987) dates back twenty-five years, before the transition to democracy and the resulting political and socioeconomic changes that accompanied this transition. In this section, we analyze qualitative data collected in forty semistructured interviews conducted from November 2010 to February 2011 with individual isiZulu-speakers based in the eThekwini region (Durban Metropolitan Area) of KwaZulu-Natal. The respondents all live in an urban setting, and the qualitative data therefore do not speak directly to the practice of, and attitudes to, ilobolo in rural areas. However, a division between urban and rural in South Africa, and in this province specifically, is far from rigid. Several of the respondents retained ties with family in rural areas, and among some married respondents the customary marriage ceremony had occurred in a rural setting.

An equal number of male and female and married and unmarried Zulu adults were interviewed. The respondents ranged from twenty-four to sixty-two years of age, and their socioeconomic characteristics varied widely. A few respondents reported no individual income, while the highest earning respondent reported a monthly income in excess of R30,000 (approximately U.S.$3,000). Formal educational attainment was equally varied, ranging from no or very little schooling to possession of a doctoral degree. Although only half of the participants (ten male and ten female) were married, almost everyone we interviewed had at least one child. Ilobolo had been paid by the prospective husbands for all the married females in the sample, and all but one of the married men had paid ilobolo (the exception had married a non-Zulu woman while living abroad).

In the lengthy, open-ended interviews, almost all of which were conducted in isiZulu and often in the interviewee’s home, we collected information on a multitude of aspects relating to marriage and ilobolo. We broadly analyze the responses to selected questions on the way ilobolo is practiced, but the analytical focus here is to interrogate to what extent the custom is valued and if the practice of ilobolo is perceived as a constraint to marriage.

The Value of Ilobolo as a Custom

Ilobolo has not been a legal requirement for Zulu marriage since 1932 (De Haas Reference De Haas1987). However, the overwhelming majority of our participants viewed the payment of a negotiated ilobolo amount as a necessary precondition for the formal recognition of a union, whether in a customary or a civil/church marriage, and for the setting up of an independent household. Most respondents regarded ilobolo as a custom of paramount importance to Zulu people in general and to themselves in particular.

Respondents were asked, among other questions, to rank the importance of ilobolo as a custom on a Likert scale from 1 (“not important”) to 10 (“very important”). A clear majority gave a ranking of 8‒10; of forty interviewees, only four ranked the importance of ilobolo as 5 or lower, and one respondent refused to provide a ranking for the custom because he did not “believe in it [ilobolo].” Although a few other respondents found the rating scale inappropriate, they nonetheless indicated that ilobolo was a salient Zulu tradition. Even individuals who struggled to identify the current purpose and functions of the custom viewed ilobolo as having strong cultural value and as the sine qua non for a “proper” Zulu marriage. Many interviewees argued along the lines of this comment: “To me, it [ilobolo] is simply important because it’s our culture. It’s something that shows to us, the Zulu people, who we are.”

All but three of the respondents also expected the custom to be maintained in the future. Two of these participants ranked the custom as “very important” but felt that the future of ilobolo was threatened either by generational change or by adverse economic change. Only one of the five participants who did not identify ilobolo as an important custom also did not expect the custom to survive in the future. Responses from the other four participants, as well as from a number of other interviewees, reflected what has been described as the “collectivist nature” of Zulu culture (e.g., De Kadt Reference De Kadt1998; Mkhize Reference Mhize, Morrell and Richter2006; Rudwick & Posel Reference Rudwick and Posel2014a). Even when respondents did not personally value ilobolo as important, or even when they expressed reservations about aspects of the custom, almost all felt that the custom would survive because of a Zulu cultural duty to observe it, and most did not believe that they had personal agency in deciding whether or not to practice it.Footnote 16 Hence the respondent who refused to rank ilobolo as a custom because he did “not believe in it” had nevertheless paid ilobolo when he himself married, even though he had experienced great hardship in saving money to do so.

Aside from this man, a consistently negative attitude toward ilobolo was noted from only one other interviewee, an unmarried female, who generally regarded ilobolo as an obstacle to marriage that forced women into illegitimate pregnancies. Another woman, who was married and experienced abuse in her marriage, felt that ilobolo had lost its purpose. She explained that originally ilobolo was an integral part of the important Zulu social tradition of ukuhlonipha (respect), but that “modern” life had dislocated this connection and that today a married woman for whom ilobolo has been paid does not necessarily receive appropriate treatment from her husband.Footnote 17

The interviews confirmed that successful ilobolo practice is a symbol of pride and respect, not only for the groom and bride, but also for their parents and relatives. In simple terms, women regard the payment of ilobolo as a reward for their good conduct and as proof of their own value as well as the worth of their grooms, while many men interpret the ability to pay ilobolo as a marker of their Zulu manhood and capability as a “provider.” These gendered constructions are consistent with Hunter’s notion of “provider love,” whereby a man’s ability to provide for a wife, signaled by the payment of ilobolo, has become entwined with romantic love (2010:42). The practice of ilobolo, as one respondent put it, is part of a sense of “doing things proper.” Hence, from a Zulu cultural perspective, having paid ilobolo or having had ilobolo paid for you improves the status of an individual and of his or her family in Zulu society. It is this profound anchoring of ilobolo in the Zulu cultural and social system that provides the custom with such saliency. However, like most customs, ilobolo is not static, and while certain assumptions are shared widely, it is practiced with considerable variation.

Individualization, Idiosyncrasy, and Commercialization

One of the most striking features of ilobolo in contemporary Zulu society is the highly individualized and idiosyncratic nature of the custom. The idiosyncratic ways in which ilobolo is practiced today are exemplified through the diversity in how the negotiations occur, the vast range of payments and number of gifts to extended family members of the groom and the bride, and the duration of the process. Furthermore, the participants in this study varied greatly in their interpretations of the current functions of ilobolo, and most ascribed multiple functions to the custom. Many respondents highlighted its cultural value, and some associated particularly a spiritual meaning to the practice, even viewing the nonpayment of ilobolo as spiritually dangerous for the future marriage because this would anger the ancestors. Several respondents referred to the role of ilobolo in establishing bonds between the two families and as signaling the husband’s respect for his wife and for her parents (see Rudwick & Posel Reference Rudwick and Posel2014a).

Nevertheless, a number of commonalities were evident. Among the married men we interviewed, very few reported that their parents had provided financial help, and only two indicated that their siblings or extended families had contributed toward their ilobolo payments. A fifty-five-year-old male who had married twice and whose father had assisted with paying ilobolo for his first marriage claimed that according to Zulu culture, the father of the groom should always contribute to the ilobolo payment for the first wife. Two others who were of similar age (55‒62 years) expressed similar views. However, most of the married men reported that their fathers had not been able to assist them, either because they were deceased or because they lacked the financial means to do so. Under these circumstances, several of the younger men felt that it was no longer the responsibility of their fathers to contribute to the payment and suggested that it was a task that they as Zulu men had to accomplish on their own. This sense of individual responsibility and its association with Zulu manhood and masculinity was particularly evident in the responses of male participants to the question of whether they would, or had, borrowed money to pay ilobolo. Almost all the men emphatically replied “no,” with the dominant view captured in the following response from a married man: “No, I worked damn hard for all the money. No one helped me out on this. It was my own duty. But this is the way ilobolo works, a man must work hard for it.” According to another respondent, the ability to pay ilobolo from one’s own income and savings was a sign that a man was “ready to get married.”

In this context, we also discussed whether a woman could possibly assist her partner financially by contributing to the payment, thereby shortening the time taken to save for ilobolo. Several, particularly male, respondents were indignant at the suggestion, with one informant, a man who acted as an umkhongi (ilobolo negotiator) for many marriages, saying that if the wife contributes, she would have “lobola’d” herself and “people would be laughing.”Footnote 18 Almost all participants emphatically stated “this is not done” (“akwenziwa lokhu”), although some acknowledged that there might be instances when this occurs, and a few women reported that they would be willing to assist their partners indirectly by contributing more to mutual living costs while their partners saved for ilobolo. There is also some evidence that a bride may bargain with her parents either to decrease the amount of ilobolo or even to raise it if she feels that the initial decision devalues her (see Rudwick & Posel Reference Rudwick and Posel2014b for further discussion).

When asked whether they would want ilobolo paid for their daughter, the large majority of interviewees responded in the affirmative, with some, who emphasized their daughters’ happiness as their first priority, also viewing the payment of ilobolo as evidence of the future husband’s ability and commitment to provide financially for his family. Very few parents openly admitted that they wanted to make a financial gain from their daughters, but almost all felt that a mere symbolic payment was not an acceptable option. However, although the vast majority stressed that the amount of money involved should be of minor importance, our interviews also indicate that Zulu mothers and fathers do have, or have had, distinct monetary expectations of the ilobolo process.Footnote 19 Many respondents identified the function of ilobolo in terms of compensation to parents. However, in contrast to the evidence from earlier studies (Radcliffe-Brown Reference Radcliffe Brown1929; Gluckman Reference Gluckman and Radcliffe-Brown1950; Ogbu Reference Ogbu1978; Kuper Reference Kuper1982; De Haas Reference De Haas1987; Guy Reference Guy and Walker1990), this compensation does not refer to the real or symbolic loss of the daughter’s productive and reproductive labor power. Rather, our respondents consistently identified the importance of compensating parents for the efforts and costs involved in raising a daughter.Footnote 20 Several of the single mothers, for instance, who had struggled to raise their children, interpreted the ilobolo payment as a reward or payback for the hardship they had endured during pregnancy and in order to provide child-care and education for their children.Footnote 21 One such interviewee, whose monthly salary did not exceed R2,000, specified that she expected a payment of at least R45,000 for her daughter, arguing that after her past financial struggles she should now be able to benefit from her daughter’s marriage. Other interviewees voiced similar sentiments, presenting ilobolo as a reward for the daughter’s upbringing.

There were some exceptions to this general point of view, however, particularly from four of the five respondents who did not rank ilobolo as an important custom in their lives. One married female interviewee, whose husband had found it very difficult to pay ilobolo, did not want her daughter’s future husband to struggle in the same way and said she was willing to accept a small “gift.” Similarly, the married male respondent who had experienced great hardship in saving for ilobolo reported that he would not expect payment and hoped only that his daughter “loves somebody and that somebody wants to marry her.” The two other respondents, an unmarried female and an unmarried male, suggested that the ilobolo payment should rather be used by the married couple themselves, either as a deposit on a house or to establish a trust fund for the couple’s children. The fifth interviewee, an unmarried female, accepted the fact that her son would have to pay it because “we’ve got to accept other people’s desires.”

Almost all the participants, including those who expected sizeable ilobolo payments for their daughters, also acknowledged that a certain commercialization of the custom had occurred, a development consistently viewed as regrettable. In response to a question about what had changed in the practice of ilobolo, the large majority echoed the reply that the custom had become “more expensive.” This was attributed particularly to the payment of ilobolo in money rather than in cows, to increased economic hardship, and in some cases, to the “greed” of parents. One young woman who was engaged to be married, and who embraced ilobolo as “our culture,” captured the general sentiments of the participants: “There have been so many changes, we all know that. I think if we still paid with cows, things would be better. But today, there are some people who just so much need money that they ask for anything.” Because there is no fixed monetary rate for a cow, payment in money rather than in cattle increases the scope for negotiating the size of the ilobolo payment. While the custom of ten cows (and one for the bride’s mother) is maintained as the standard payment, the monetary equivalent of the cattle is open to interpretation. This fluidity provides space for parents to negotiate a higher rate for the cattle, and while the vast majority repudiated this practice for themselves, some identified cases where ilobolo payments were larger for women with higher educational and professional credentials.

Most current Zulu ilobolo negotiations described by the interviewees are also only the beginning of a lengthy process that involves the exchange of gifts between the two families. In addition to ilobolo, the groom pays for gifts (izibizo) that are given to the family of the bride. To signal reciprocity, a substantial amount of food (umbondo) and a number of gifts (umabo) are also given by the family of the bride to the family of the groom, which frequently are financed using part of the ilobolo payment. When asked what has changed in the practice of ilobolo, several participants referred specifically to an “abuse” in the practice of umabo, with the groom’s family asking for very expensive gifts such as stoves and refrigerators, rather than the customary gifts of bedding and grass mats (see De Haas Reference De Haas1987).

Almost all the participants agreed that ilobolo does not have to be paid in full by the time of the wedding and referred to the well-known isiZulu proverb, “amakhoti akaqeda” (women do not get finished), meaning that the payment for women never ends. The man who had acted as an umkhongi in several marriages claimed that the full payment of ilobolo before the wedding fails to signal the groom’s commitment to harmonious future relations with the bride’s family. Nonetheless, we became aware of numerous cases in which either the groom or the bride’s parents insisted on the total amount being paid before the wedding. For the parents, this eliminates the risk that once the marriage has taken place, the remaining ilobolo amount will not be paid; for the groom, the motive seems to be a desire to settle all financial obligations to the bride’s parents so they can make no future claims on his income.

The full payment of ilobolo before marriage increases the economic requirements for men to marry. But our interviews show that even where negotiations were very amicable and the ilobolo payments were not made in full, the amount paid before marriage typically required men to save for a considerable period of time.

Ilobolo and Marriage: Desired but Unattainable

The overwhelming majority of the unmarried interviewees, both female and male, reported wanting to get married. When they were asked whether they thought the practice of ilobolo had made it more difficult for them to marry, most women responded in the affirmative. One participant who also did not rank ilobolo as an important custom declared that “ilobolo should be over and done with because it is not good. . . . Our daughters are getting old, having unclaimed children at home. I would not have had my baby at home if this ilobolo thing was not there. A lot of people would have been married.” However, several respondents who did rank ilobolo as a very important custom expressed similar views. One claimed that ilobolo “delays everything, where you end up not being married because maybe the person who wants to marry you can’t afford [it].” Another said that “the reason we are not married, and we get old in our mothers’ homes, is because of ilobolo. I wish it can be stopped—but they will never do that because it is culture.” The shift from the first person to the third person in the last sentence is noteworthy, suggesting that the individual does not perceive herself to have personal agency in matters of Zulu culture.

The view of ilobolo as an impediment to marriage was acknowledged less often and less emphatically in the interviews with unmarried men, possibly because of the strong association between the ability to pay ilobolo and masculinity. Almost all the unmarried men who were interviewed pointed to the rising costs or the commercialization of ilobolo, but few attributed their unmarried status to having to pay ilobolo. Rather, most of the men indicated that they did not feel financially ready to get married, and that they wanted to be in a better socioeconomic position by the time of marriage. The ability to pay ilobolo was taken as one sign of this more general readiness. As one unmarried male respondent commented, “I would be in a marriage, but not happy.” However, one participant also acknowledged that his relationship had ended because his fiancée considered that the process encompassing the first ilobolo negotiation, the initial payment, and the actual planning for the wedding was taking too long.

In earlier research, De Haas (Reference De Haas1987) found little support from her respondents that the payment of ilobolo forced couples to postpone marriage. In contrast, we find far more recognition, particularly among unmarried Zulu women, that the payment of ilobolo may delay or even prevent marriage. However, for the most part, this is not accompanied by a rejection of the custom. On the contrary, even those who voiced reservations during the interviews about the commercialization of the custom and the difficulties of marrying still acknowledged ilobolo as an important Zulu custom which most feel obliged, and often proud, to maintain for complex cultural, social, and spiritual reasons.

Conclusion

In contemporary South African society, only about a quarter to a third of isiZulu-speaking adults are or have been married, although most isiZulu-speakers report positive marriage aspirations. The reasons for the low marriage rate are complex and varied, but in this study we present evidence that the current practice of ilobolo, in addition to the other economic costs of marrying, may be part of the explanation.

Ilobolo payments have become increasingly difficult to pay partly because many men now assume this responsibility without financial support from their fathers. Ilobolo is also perceived as more expensive than it was in the past, both because of the change to payment in money rather than in cattle and also because of the increasing demands of parents. Whether ilobolo payments actually have increased over time or whether this is mostly a subjective perception is unknown, since no microdata are available to track these trends. It is possible, therefore, that respondents only perceive ilobolo as being more expensive now because of very poor labor market opportunities for African men in recent decades. Nevertheless, microdata collected in a 1998 household survey for KwaZulu-Natal (KIDS 1998) corroborated reports from respondents that ilobolo is typically much larger than the mean monthly earnings of African men.

Although ilobolo is viewed as increasing the economic requirements for marriage, our interviews document widespread respect for ilobolo as a custom, which in most cases is embraced by Zulu adults as a distinguishing feature of an African marriage and as an integral aspect of Zulu culture. However, while all respondents disapproved of the increasing commercialization of the custom, we found that many Zulu mothers and fathers also have clear monetary expectations of ilobolo for their daughters, framed mostly in terms of compensation for the efforts and costs of raising a daughter. A very low ilobolo payment is perceived as signaling a lack of respect for, or appreciation of, the wife’s parents, and also by implication, the wife herself. Thus several of the women we interviewed also had very definite views about how much they were “worth” or what amount of ilobolo should be paid for them. Men (and women) also linked the payment of ilobolo to Zulu masculinity, a relationship that has been strengthened by the generational shift in the responsibility to pay ilobolo. For women, the value of ilobolo therefore attests both to her worth as a woman and the worth of her prospective husband, while for men the ability to pay ilobolo is taken as a marker of Zulu masculinity and a sign that a man is financially ready to marry. These associations between the value of ilobolo and the worth of parents, wives, and husbands may help to explain why ilobolo demands have not fallen in response to low marriage rates and high rates of unemployment.

The interviews in this study also reveal that for the clear majority of respondents, marrying without the payment of ilobolo would not be possible or desirable. Even among individuals who expressed some skepticism about the value of the practice, very few indicated that they had the personal agency to decide whether or not to follow this custom. Ilobolo therefore remains a defining feature of a Zulu marriage, explaining why high ilobolo demands are likely to constrain marriage in Zulu society.

Low marriage rates have significant implications for the nature of family formation in South Africa. Although in some cases unmarried men are able to claim rights to children through the payment of “damages” to the mother’s family, the father does not have the right to live with the mother and his child unless ilobolo also has been paid. Respect for ilobolo as a custom, therefore, may also help explain why, in the context of high rates of nonmarriage, cohabitation rates have not increased more (Posel & Rudwick Reference Posel and Rudwick2014) and why the majority of African children in South Africa grow up in households where their fathers are not resident (Posel & Devey Reference Posel, Devey, Richter and Morrell2006).

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers and editors for their insightful comments and suggestions, and Magcino Shange for her research assistance. The research on which this paper is based was funded by grant income attached to a South African Research Chair, funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and administered by the National Research Foundation (NRF).