Introduction

The eating disorders provide one of the strongest indications for cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). This bold claim arises from two sources: first, the fact that eating disorders are essentially cognitive disorders and second, the demonstrated effectiveness of CBT in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, which has led to the widespread acceptance that CBT is the treatment of choice (NICE, 2004). Eating disorders are essentially cognitive disorders as they have as their distinctive core feature an over-evaluation of shape and weight and their control, which results in those with these disorders judging their self-worth largely or exclusively in these terms. This over-evaluation is shared across anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, the two disorders recognized by DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and occurs in most cases of those who fall within the DSM residual category, eating disorder not otherwise specified (eating disorder NOS). In addition to being the treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa, CBT is also widely used to treat anorexia nervosa, although this application has not been adequately evaluated (Wilson, Grilo and Vitousek, Reference Wilson, Grilo and Vitousek2007). Recently, its use has been extended to eating disorder NOS, a diagnosis that applies to over 50% of cases (Fairburn, Cooper, Bohn, O'Connor, Doll and Palmer, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Bohn, O'Connor, Doll and Palmer2007), and emerging evidence suggests that it is just as effective with these cases as it is with cases of bulimia nervosa (Fairburn et al., in press). In this article the cognitive behavioural approach to the understanding of eating disorders will be described and a summary of the evidence supporting the theory and treatment will be provided. The treatment derived from this model will be briefly outlined and a number of challenges for the future will be identified.

The development of the cognitive behavioural account of the maintenance of eating disorders

From its origins in the 1980s when a cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of the newly recognized and supposedly “intractable” bulimia nervosa was first developed (Russell, Reference Russell1979), the treatment has been theory-based (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn1981). As with most evidence based CBT, the theory that underpins treatment is concerned with the processes that maintain the disorder rather than with an account of its development. Initially, in accordance with the DSM scheme for classifying eating disorders that encourages the view that the eating disorders anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are distinct clinical states each requiring their own form of treatment, the theory focused on the maintenance of bulimia nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, and Cooper, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Cooper, Brownell and Foreyt1986). This theory has been extensively studied and the treatment derived from it, CBT-BN (Fairburn, Marcus and Wilson, Reference Fairburn, Marcus, Wilson, Fairburn and Wilson1993b), has been endorsed by NICE (2004) as the leading treatment for bulimia nervosa on the basis of evidence derived from over 70 randomized controlled trials.

Recently, the cognitive behavioural account of the maintenance of bulimia nervosa has been enhanced and extended to all eating disorders (Fairburn, Cooper and Shafran, Reference Fairburn, Cooper and Shafran2003). The transdiagnostic theory of Fairburn and colleagues and the enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy based on it (CBT-E) were developed in response to two major challenges. First, as noted earlier, patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder NOS have many features in common, most of which are not seen in other psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, studies of their course indicate that most patients migrate between these diagnoses over time (Milos, Spindler, Schnyder and Fairburn, Reference Milos, Spindler, Schnyder and Fairburn2005.) This temporal movement, together with the shared but distinctive psychopathology, challenges the view that there are a number of distinct eating disorders and suggests rather that common “transdiagnostic” mechanisms are involved in the persistence of eating disorder psychopathology (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Stice, Cooper, Doll, Norman and O'Connor2003). Second, despite its status as the leading treatment for bulimia nervosa it was clear by the end of the 1990s that CBT-BN needed to be improved, since less than half of the patients entering treatment were making a full and lasting recovery (Wilson and Fairburn, Reference Wilson, Fairburn, Nathan and Gorman2007). As a result, the cognitive behavioural theory has been extended to embrace four additional maintaining mechanisms that, in certain patients, interact with the core eating disorder maintaining mechanisms and constitute obstacles to change (see below).

The transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural theory

According to the cognitive behavioural view it is the distinctive and well-recognized dysfunctional scheme of self-evaluation shared by patients with eating disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) that is of central importance in maintaining these disorders. Whereas most people evaluate themselves on the basis of their perceived performance in a variety of domains of life, people with eating disorders judge themselves primarily in terms of their shape and weight and their ability to control them. Other clinical features can be understood as stemming directly from this “core psychopathology”, including the extreme weight-control behaviour (viz., the dieting, self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse and over-exercising), the various forms of body checking and avoidance, and the preoccupation with thoughts about eating, shape and weight (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008).

The only feature that is not obviously a direct expression of the core psychopathology is binge eating, which occurs in many patients with eating disorders whatever their DSM diagnosis (Cooper and Fairburn, in press). The cognitive behavioural theory proposes that binge eating is largely a product of attempts to adhere to multiple extreme, and highly specific, dietary rules. These patients’ tendency to react in a negative and extreme (dichotomous) fashion to the almost inevitable breaking of these rules results in even minor dietary slips being interpreted as evidence of poor self-control and personal weakness. Patients respond to this perceived lack of self-control by temporarily abandoning their efforts to restrict their eating. This produces a highly distinctive pattern of eating in which attempts to restrict are repeatedly interrupted by episodes of binge eating. The binge eating maintains the core psychopathology by intensifying patients’ concerns about their ability to control their eating, shape and weight and by encouraging further dietary restraint, thereby increasing the risk of further binge eating (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008).

Three further processes also maintain binge eating. First, life difficulties and associated mood changes increase the likelihood that patients will break their dietary rules. Second, since binge eating temporarily ameliorates such mood states and distracts patients from thinking about their difficulties it can become a way of coping with these difficulties. Third, if the binge eating is followed by compensatory vomiting or laxative misuse, this also maintains binge eating because patients’ mistaken belief in the effectiveness of such “purging” undermines a major deterrent against binge eating. They do not realize that purging has little effect on energy absorption (Cooper, Murphy and Fairburn, in press).

Patients with anorexia nervosa share the distinctive core psychopathology of those with bulimia nervosa and eating disorder NOS. The major difference is that in anorexia nervosa under-eating predominates and therefore patients become extremely underweight while in cases of bulimia nervosa and eating disorder NOS body weight is usually unremarkable because the overeating and under-eating tend to cancel each other out. The extreme low weight that occurs in anorexia nervosa has certain secondary physiological and psychological consequences that contribute to patients continuing to under-eat. For example, delayed gastric emptying results in a sense of fullness, even after eating modest amounts of food, and secondary social withdrawal magnifies patients’ isolation from the influence of others (Garner, Reference Garner, Garner and Garfinkel1997).

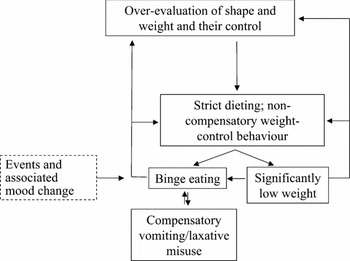

The processes that maintain bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa also seem to maintain the clinical presentations seen in eating disorder NOS (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Stice, Cooper, Doll, Norman and O'Connor2003). Figure 1 provides a “transdiagnostic” representation (or “formulation”) of the core processes involved in the maintenance of eating disorders.

Figure 1. The transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural formulation of maintenance of eating disorders (adapted from Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008)

As mentioned earlier, in addition to the core eating disorder maintaining mechanisms, the theory underpinning CBT-E proposes that there are additional external (to the core eating disorder) mechanisms that, when present, maintain the disorder and are obstacles to change. The role of each of these additional mechanisms (“clinical perfectionism”, “core low self-esteem”, “mood intolerance” and interpersonal “interpersonal difficulties”) in the maintenance of eating disorders will be briefly discussed.

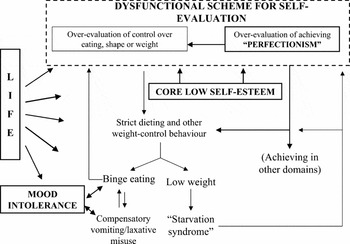

Perfectionism frequently co-occurs with eating disorders (Wonderlich, Reference Wonderlich, Fairburn and Brownwell2002; Bulik et al., Reference Bulik, Tozzi, Anderson, Masseo, Aggen and Sullivan2003), it has been identified as a specific risk factor for the development of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Doll and Welch, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Doll and Welch1999) and it has been suggested that it may impede the successful treatment of Axis 1 disorders particularly in cases where the domain in which the perfectionism is expressed overlaps with that of the disorder (Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn, Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002). The psychopathology of perfectionism is similar to the core psychopathology of eating disorders in that both are examples of dysfunctional systems of self-evaluation. In cases where perfectionism is a clinical problem there is often an interaction between the two forms of psychopathology with perfectionist standards being applied to attempts to control eating, weight and shape. As in other expressions of perfectionism (Shafran et al, Reference Shafran, Cooper and Fairburn2002), there is a fear of failure (e.g., in those with eating disorders, a fear of “fatness” or losing control over eating), frequent and selective attention to performance (e.g. frequent weighing and shape checking) and self-criticism based on negatively biased appraisals of performance. As illustrated in Figure 2 showing the extended “transdiagnostic” representation (or “formulation”) of the processes involved in the maintenance of eating disorders, the resultant negative self-evaluation leads to more determined striving to meet demanding goals (e.g. controlling eating, shape and weight) and thereby serves to maintain the eating disorder.

Figure 2. The transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural formulation of the maintenance of eating disorders with the external maintaining mechanisms (adapted from Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Stice, Cooper, Doll, Norman and O'Connor2003)

Clinical experience and research evidence indicate that low self esteem is common amongst patients with eating disorders and may predate their onset (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, Bohn and Hawker, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, Bohn, Hawker and Fairburn2008). There is also evidence from research on bulimia nervosa that low self-esteem is associated with a poor response to treatment (Fairburn, Peveler, Jones, Hope and Doll, Reference Fairburn, Peveler, Jones, Hope and Doll1993c). Low self esteem does not necessarily obstruct change; indeed it may change with the successful treatment of the eating disorder without being explicitly targeted. However there is a subgroup of patients who have “core low self-esteem” where it appears to maintain the eating disorder by two main processes. First, it leads patients to strive particularly hard to control their eating shape and weight in order to improve their self-evaluation (see Figure 2) and second, more generally, the unconditional and pervasive nature of these patients’ negative view of themselves creates hopelessness about their capacity to change.

A subgroup of patients with eating disorders have what may be termed “mood intolerance”, that is they are either extremely sensitive to certain emotional states and have difficulty tolerating them or they experience unusually intense moods or both (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, Bohn, Hawker and Fairburn2008). While this intolerance is generally of adverse moods, there may be sensitivity to all intense mood states including positive ones. This intolerance leads patients to engage in behaviour to cope with or neutralize these moods. As binge eating (Stice, Reference Stice1994; Waller, Reference Waller, Fairburn and Brownwell2002) self-induced vomiting and over-exercising all potentially have the ability to modulate mood, these behaviours are likely to be maintained in patients who have an eating disorder and are mood intolerant (see Figure 2).

Most patients with eating disorders have difficulties with their relationships and in many these improve markedly once the eating disorder improves even if they have not been specifically targeted in treatment (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, Bohn, Hawker and Fairburn2008). However in some patients interpersonal difficulties contribute significantly towards maintaining the disorder. Interpersonal events may lead to an intensification of dietary restraint to such an extent that patients may cease to eat for a period or they may trigger episodes of binge eating, vomiting, laxative misuse or over-exercising (see the influence of “life” in Figure 2). In addition long-term interpersonal difficulties undermine self-esteem (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Stice, Cooper, Doll, Norman and O'Connor2003), which, as noted, earlier may result in further striving to achieve valued goals such as success at controlling eating, shape and weight. It should also be noted that disturbed interpersonal functioning predicts poor response to treatment (Agras et al., Reference Agras, Crow, Halmi, Mitchell, Wilson and Kraemer2000).

The transdiagnostic theory highlights the full range of processes that need to be addressed in the treatment of eating disorders and it is this theory which underpins the practice of CBT-E. In some cases only certain of the core processes are active (for example, in most cases of binge eating disorder), but in others (for example, cases of the binge-eating/purging subtype of anorexia nervosa) most are operating and, similarly, one or more of the four external maintaining mechanisms are not invariably present.

Evidence for the cognitive behavioral account

There is considerable research evidence supporting the cognitive view of the maintenance of eating disorders (Vitousek, Reference Vitousek and Salkovskis1996) including descriptive and experimental studies of the clinical characteristics of these patients (Shafran, Fairburn, Robinson and Lask, Reference Shafran, Fairburn, Robinson and Lask2003; Shafran, Lee, Payne and Fairburn, Reference Shafran, Lee, Payne and Fairburn2007; Shafran, Lee, Cooper, Palmer and Fairburn, Reference Shafran, Lee, Cooper, Palmer and Fairburn2007) and the research on dietary restraint and ‘counter-regulation’ (a possible analogue for binge eating) (Polivy and Herman, Reference Polivy, Herman, Fairburn and Wilson1993). There is also strong indirect support from a large body of clinical trials indicating that cognitive behaviour therapy based on this model has a major and lasting impact on bulimia nervosa (NICE, 2004) and emerging evidence that this is also true of eating disorder NOS (Fairburn et al., in press). “Dismantling” the cognitive behavioural treatment for bulimia nervosa by removing procedures designed to produce cognitive change attenuates its effects and results in patients being markedly prone to relapse (Fairburn, Jones, Peveler, Hope and O'Connor, Reference Fairburn, Jones, Peveler, Hope and O'Connor1993a). Direct support comes from studies that have shown that dietary restraint mediates the treatment's effect on binge eating (Wilson, Fairburn, Agras, Walsh and Kraemer, Reference Wilson, Fairburn, Agras, Walsh and Kraemer2002) and that continuing over-evaluation of weight and shape in those who have recovered in behavioural terms is predictive of subsequent relapse (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Peveler, Jones, Hope and Doll1993c, Reference Fairburn, Stice, Cooper, Doll, Norman and O'Connor2003).

Transdiagnostic cognitive treatment of eating disorders

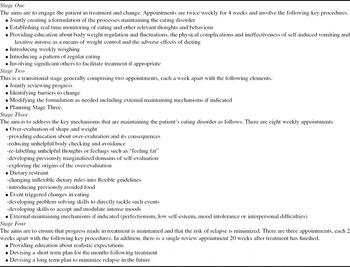

Full details of CBT-E as well as details about assessment are provided elsewhere (Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008). The treatment is outpatient-based and involves 20 individual treatment sessions over 20 weeks for the 80% or more of patients who are not significantly underweight (body mass index over 17.5). The remaining patients with a body mass index of 17.5 or below receive 40 sessions over 40 weeks. There are two forms of CBT-E: a focused form (CBT-F) that focuses exclusively on eating disorder psychopathology, and a broad form (CBT-B) that also addresses the external obstacles to change. Preliminary findings indicate that overall the two forms of treatment are equally effective but that for those patients who have two of the four external mechanisms judged by their therapist after 4 weeks of treatment to be a “moderate” or “major” clinical problem (about 40% of patients), the broad form was superior to the focused form. For the remaining 60% of patients, the focused form of treatment was superior to the broad form. These findings are consistent with the theory underpinning CBT-E and with our clinical experience. Brief details of the content of the four stages of the 20 week treatment are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. The core elements of enhanced cognitive behavioural treatment

Underweight patients

When treating patients who are underweight three main modifications to the treatment are required: the motivation of these patients needs to be enhanced, their state of starvation needs to be corrected, and significant others are more likely to be involved. As a result treatment is considerably longer.

Future directions

Both the cognitive behavioural treatment of eating disorders and the theory on which it is based have been extensively evaluated and enhanced. There is emerging evidence to suggest that CBT-E is applicable to the great majority of cases of eating disorders. However, at least three important challenges remain.

Two of these challenges concern the treatment itself. First, treatment needs to be made more effective. Despite its successes, CBT-E does not help everyone. There is an urgent need to understand the reasons for treatment failure in order to improve it further. The second related challenge is to better understand how treatment works. Knowledge of the active ingredients of treatment would provide the basis for further enhancing these and omitting redundant ones. It might also suggest ways to simplify treatment, generally, or in particular cases. A third challenge concerns dissemination of the treatment. There is an urgent need to understand how this is best achieved.

Acknowledgments

ZC is supported by a Wellcome programme grant (046386).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.