Introduction

Since the emergence of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Syria, media reports have proliferated, covering news of its atrocities, including the destruction of Syrian cultural heritage.Footnote 1 Many of the reports of such destruction have been based on videos broadcast by ISIS on its social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube as well as on information that has come from scattered activists in regions under the group’s control.Footnote 2 Much scholarly research has focused on ISIS’s spectacular destruction of heritage,Footnote 3 and this research has included work on its practices, attempts to understand and analyze its behavior,Footnote 4 and, in particular, investigations into the relationship of its ideologies to cultural heritage.Footnote 5 Other investigations have considered the amount of money that ISIS has made by selling antiquities and through antiquities trafficking.Footnote 6 These works have been based on the information available, including, for example, incomplete media reports or public information in auction catalogues. Little verifiable information has come directly from non-ISIS sources inside Syria due to the lack of traditional media presence, a result of the extreme security situation.

ISIS has not been the only actor responsible for the destruction of cultural heritage in Syria, however; many sites have been damaged or looted by forces from the Assad regime,Footnote 7 Iranian militia,Footnote 8 and the Al-Nusra Front / Jabhat al-Nusra, which is known as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham.Footnote 9 Nonetheless, this article will focus on the region of Manbij and on ISIS as a case study for several reasons. The city of Manbij (ancient Hierapolis) is one of the archaeologically richest areas of Syria. Important archaeological sites in the region are preserved from different periods, ranging from the Neolithic site of Tell Halula, a village of early farmers in the valley of the Euphrates (7750 bc), which is 25 kilometers northwest of Manbij;Footnote 10 Emar, a Bronze Age site (3200 to 1150 bc), which is close to the modern city of Meskene;Footnote 11 the Seleucid site of Jebel Khalid on the west bank of the Euphrates;Footnote 12 and the Roman site of Shash Hamdan located a few kilometers downstream from the Tishreen Dam (Figure 1).Footnote 13 Most of these sites were looted and vandalized by ISIS.Footnote 14 In this rich archaeological region, the establishment of the Diwan Al-Rikaz by ISIS and, specifically, the division known as Qasmu Al-Athar has had a deliberate and direct role in the destruction and looting of Syrian culture heritage. Working with a team of archaeologists there, I was able to document many of the sites after ISIS undertook or enabled their destruction, including at the site of Meshrefet Anz (Khirbet Al-Anz).Footnote 15

Figure 1. A map of the sites listed in the research; white line indicates Aleppo governate (Source: author 2019).

The Day After (TDA) is a non-governmental organization with which I work that seeks to support a democratic transition for Syria.Footnote 16 Under its vice chairman, Amr Al-Azm, who is a professor at Shawnee State University, TDA has contributed key scholarship on the excavation and trade of Syrian heritage by ISIS.Footnote 17 Al-Azm has also written in general about the Antiquities Office in Manbij and about ISIS’s organization and fiscal control of illicit excavation and trade in Syria.Footnote 18 As a former member of the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) of Syria, and a Syrian native of this region, my clan relations and existing networks enabled me to be part of a team of archaeologists in 2013. Initially, we had worked under the DGAM in 2012 and 2013. When ISIS took control the region in 2014, this team was developed and expanded to document ISIS’s activities against Syrian cultural heritage on behalf of TDA’s Heritage Protection Initiative (HPI).Footnote 19 I was a team leader documenting the looting and destruction of archaeological sites in Manbij on behalf of the HPI, which also existed in other Syrian provinces, working with volunteers for the documentation and protection of Syrian cultural heritage.

Through my work on the ground in Syria during ISIS’s control of Manbij, as well as through my continuing contacts there, this article provides a new understanding of ISIS’s use of heritage based on observations made at the time they controlled the region. In addition to documenting the structure of ISIS’s Qasmu Al-Athar and its functions, it is possible to observe a shift over time in ISIS’s behavior concerning antiquities, from destruction for its own sake to looting as a source of financial income. In conclusion, I will summarize the results of this research and provide some recommendations to researchers and specialists in the field of heritage preservation.

Manbij before ISIS

By July 2012, the Free Syrian Army (FSA)Footnote 20 and the Islamic factions had imposed control over the city of Manbij and its countryside. They expelled the security services loyal to the regime, established alternative security units and a new judicial apparatus to extend state and law authority, but these factions could not unite into one body. Conflicts ensued, causing chaos in the areas that they controlled. There were thefts, kidnappings, and other abuses against the civilian population. The region suffered from insecurity and a lack of institutions and basic services. This chaotic situation encouraged the antiquities looters to carry out digs in the absence of regulatory institutions to impose effective control, which led the increase of opportunistic looting causing damage in some archaeological sites in the region.Footnote 21

ISIS in Manbij

ISIS fighters took control of the city of Manbij on 23 January 2014, after reaching an agreement with the FSA, under which ISIS stopped bombing civilians and the FSA turned over the city. I witnessed this event, and ISIS passed in front of my house on Aleppo road, coming from Al-Bab city. The fighters were masked and waved the flags of the Islamic state. From the first days of its control of the city, ISIS’s forces began to control government centers, schools, and bakeries and turned them into administrative centers. For example, it converted the Zidane Henedel Secondary School to the seat of the Shari’a court, the Saraya Building in the middle of Manbij was used as an office for Civil Status and Civil Registration and Municipality, the Arab Cultural Center in Manbij was converted to a police station and a security headquarters, the building of the Manbij Hotel was converted into a large prison (Figure 2), and ISIS seized the mills and bakeries in the city with guards armed with heavy weapons. Barriers and checkpoints were erected in the entrances of the city. The municipality started cleaning the streets, fixing the sidewalks, and tree planting. On 28 January, I went to the Manbij souq (marketplace) where the crowds were all talking about ISIS, and I heard many of my friends and shop owners discussing with each other that the fighters of Aldawla (a local name for ISIS) were strong, united, and highly organized: they had courage in the eyes of Manbij’s people. Indeed, the local people saw how just 200 fighters from the Islamic state had forced more than 1,600 fighters of the FSA and Islamic factions to withdraw from the city.

Figure 2. Aerial photograph of Manbij indicating some of the institutions that ISIS converted to administrative and security headquarters: (1) Saraya of Manbij; (2) the Hotel of Manbij; (3) the postoffice of Manbij; (4) the prison of ISIS; (5) the Arab Cultural Centre; (6) the Park of Almansour; (7) the Manbij Souq; (8) the Zidane Henedel School; (9) the Seven Fountains Square; (10) Automated Bakery (Source: Google Earth 2019).

The control of the security forces in the Manbij area and its countryside was one of the most important elements that distinguished ISIS from the FSA and the Islamic factions; Manbij now had ISIS as a unified authority, which oversaw all its institutions, and the citizens of the city were initially pleased with this situation. But the majority of educated individuals were fearful and doubtful of ISIS’s intentions. When I met many teachers and ex-government employees in Manbij, they told me about how ISIS was fighting against the FSA and how they had killed a large number of revolutionaries in the city of Al-Bab and in Al-Raqqa. I heard their opinions about ISIS: they believed that ISIS was part of the Assad regime. They told me about the timing of ISIS’s appearance on the scene in Syria and its assassinations of leaders in the FSA who had defeated the regime. These educated people incited people to civil disobedience against ISIS on 18 May 2014 by, for example, closing shops, having a general strike, and joining small protests in the souq. After these protests, ISIS arrested many former government employees and detained others that did not show allegiance to it.

ISIS did not rule by the sword alone. They wielded power through two complementary tools: brutality and bureaucracy.Footnote 22 In Manbij, relying on local expertise from former employees and through security apparatus and intelligence operations that consisted of Syrians and foreigners, ISIS was able to establish an administrative structure that served to manage its areas of control. These administrative offices were given the Islamic nomenclature of ministries and offices, but they differed greatly in their behavior and structure and in the way in which they served Muslims, not working like true Islamic institutions to ensure justice and peace but, rather, collecting taxes and slaughtering innocent people. There is no doubt that ISIS wanted to deceive the people with the names of their organizations. ISIS looked like a state from the outside, with an institutional structure to serve the citizens of the Caliph, but the truth was that all the institutions were aimed primarily at extracting the citizens’ money, and, to do so, it used very similar tools to other corrupt authoritarian regimes. For precedent, they needed to look no further than the Assad regime in Syria, which uses slogans such as “unity,” “freedom,” and “socialism” but, in fact, rules in a sectarian and racist way and has utilized Syria’s wealth to serve its ruling family—a model followed by ISIS in claiming that it wanted to revive the Islamic caliphate.Footnote 23 But ISIS killed thousands of Muslims, ruled on a sectarian basis, and looted the region’s wealth. It also implemented an “emergency law”: in order to control its territories, the behavior of ISIS was similar to the emergency law that the regime has used in Syria for decades and is still using it to this day.Footnote 24 By virtue of the “laws” of ISIS, the power to implement its rule was given to foreigners who were not professionally qualified to enforce them.

ISIS began to make accusations against many individuals who it deemed to be problematic, often educated people who it suspected might be sympathetic to the FSA, on ready-made charges, such as that of spy or infidel. ISIS called the FSA apostates. This definition allowed the fighters of ISIS to arrest, kidnap, or kill any civilian or soldier of the FSA without an order from the judiciary or a trial because they were apostate or kafir (infidel). These actions continued what the regime of Bashar al-Assad had been doing, if more openly: Assad’s civilian opponents have been routinely accused of espionage on behalf of Israel or the United States. This brutal oppression of dissent was an Assad family tradition, and, as is well known, more than 30,000 civilians were killed in Hama by Hafez al-Assad’s army on charges of sympathizing with the Muslim Brotherhood Movement.Footnote 25

The second example of the similarity between the Assad regime and ISIS in the control and governance of its territories is Al emni (the intelligence agents): their function is to gather intelligence about everyone who lives inside the “Islamic State.”Footnote 26 ISIS spreads its agents throughout the region it controls, including the villages, in order to collect and transfer all the news that is happening in these areas. This is the same method that has been used by the Assad regime, in which 15 branches of security in Syria monitor people’s behavior and opinions.

In my opinion, the most important point of similarity between the ISIS system of administration and that of the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria (as well as in Nur al-Maliki in Iraq, perhaps because most the staff are shared by these two regimes)Footnote 27 is that the administrative orders and written correspondence or media propaganda of the regime do not reflect actual conduct on the ground. According to their internal institutions on television, the number of projects launched by the Assad regime every day is approximately 10, but, on the ground, there is nothing to report. For example, a new Aleppo Museum project was meant to replace the existing Aleppo Museum, which had long been suffering, in particular, with problems from water damage, which had caused parts of the building to sink and floods and high humidity to damage the collections. The Assad government had talked for more than 15 years about addressing this issue, including when Bashar Al-Assad himself visited the Aleppo Museum in 2005.Footnote 28 During this visit, he promised that the project would start very soon, but, to this date, nothing has happened on the ground. ISIS has also been trying to show through its media the existence of institutions working to build the Caliphate state. But all that these institutions actually did was to manage the existing infrastructure (including, for example, power stations, dams, mills, agriculture, and oil), which it inherited from the al-Assad and Maliki regimes. ISIS has sought to facilitate the looting and exploitation of existing resources in the region, not to build a state with infrastructure and development projects, and because those living in ISIS’s territory know this fact, ISIS has had to turn to professional media propaganda in order to introduce itself to the world as a state.Footnote 29

ISIS also has relied on the administrative divisions of the regime of al-Assad but has modified some of the place names and introduced older names inspired by Islamic culture. For example, in the region of Manbij, the town of Meskana was changed to become Maslama, which was named for a relative to the Muslim leader Habib bin Muslim al-Fehri. ISIS divided its areas into wilayat and sectors and established the dawawin (ministries), offices, and departments of these ministries. After taking full control of the area, it began to tighten its security and impose its extremist ideology on the local people. ISIS changed the imams of mosques in Manbij and replaced them with the extremist imams from Tunisia and Egypt, banned smoking and the trade of tobacco, and forced women and men to dress in an approved ISIS style—for instance, for women, wearing a face covering and, for men, growing a beard and shaving their mustaches. People have tried to express their opposition through civil disobedience, but ISIS has forcibly oppressed this action. For example, an audio recording posted on YouTube records a dialogue between Emir Manbij and his fighters demonstrating ISIS’s brutality in suppressing a civil strike, where ISIS fighters broke shop locks, looted their contents, and arrested the owners.Footnote 30 ISIS also began to apply al-hudud, the punishment stipulated in the Qur’an but interpreted by ISIS’s own reading of the text. Immediately after the civil disobedience, ISIS began to paint all the walls and the entrances of the cities in black and wrote their extremist slogans on the walls.

ISIS arrested the soldiers of the FSA, who surrendered their weapons to ISIS fighters upon entering Manbij, as well as confiscating their money and homes. Many were executed in the public squares of Manbij and its suburbs. Although ISIS sought to apply sharia as a basis for governance (again according to their own particular reading of Islam), the mechanisms it used to do so were still being formed and were therefore not consistent or predictable, which resulted in popular dissatisfaction with its governance. Different emirs interpreted and applied rules differently, causing resentment among some populations. ISIS also became more brutal in its dealings with its constituents, leading people to complain about it privately. In a way, the group trapped itself: it turned to violence so often that it could not de-escalate without losing credibility.Footnote 31 The scenes of murder, crucifixion, beheadings, and forced amputation of hands were almost daily practices in the Manbij area. The mosques became centers for promoting extremism, and Al-Hisbah cars (vehicles of the Islamic religious police) circled the streets to monitor people’s behavior.

All of this background information is relevant because the looting of antiquities also followed this model: ISIS invested and looted all the resources in the region through an existing infrastructure and used experienced staff to conduct the looting. Both were inherited from the Assad regime.Footnote 32 Existing structures of permissions and permits were used to provide taxation infrastructure for the antiquities. This taxation of antiquities looting was among the key resources for providing direct funds for ISIS. In the eighth part of ISIS 2020, a series of briefings about the current status of the Islamic state by authors from different parts of the region, a conversation is recorded between Husham al-Hashimi and Abdul Nasser Qardash, the highest-ranking ISIS leader incarcerated in Iraq, in which Abdel Nasser confirms that ISIS stopped destroying antiquities when they realized that they could sell them: “We did not need to grow hashish, cocaine, or Indian hemp. We had an obscene abundance of antiquities. We tried to transfer the relics to Europe to sell them, but we failed in four major attempts. This is especially true for Syrian relics, which are well known and documented as a world heritage. So, we resorted to destroying them and punishing those who trade in them.”Footnote 33 Indeed, the trafficking of antiquities may have become the second-most-important source of revenue for the group, according to the Congressional Research Service.Footnote 34

Of course, it is evident that ISIS was not the only party that looted and destroyed Syrian archaeological sites: the Assad regime is documented as having done so as well, damaging sites such as the Cracs des Chevaliers, the Um al-Zanar Church in Homs, the Museum Ma’arat al-Nu’man in Idlib,Footnote 35 and the al-Omari Mosque in Daraa.Footnote 36 Hezbollah, an ally of the Assad regime, which has a long history in the arms and drug trade,Footnote 37 has undoubtedly benefited from its networks in Syria and abroad in looting Syrian archaeological sites. Jabhat al-Nusra and extremist factions have contributed to the looting and destruction of archaeological sites through the granting of permits to dig as well as by using archaeological sites as training centers for the use of weapons. For example, on 4 October 2017, a Jabhat al-Nusra fighter destroyed an archaeological wall of the Simbol Monastery in Idlib governorate because the flag of the revolution was raised above the wall.Footnote 38

Many other Syrians, unfortunately, also have damaged archaeological sites, whether out of poverty, ignorance, or greed. Some of them have worked in the trade of antiquities, and some of them have worked as mediators between traders and the archaeological digs, while others have worked in smuggling pieces inside or outside Syria. There are also individuals known as antikajı,Footnote 39 who are Syrians known to be interested in antiquities for financial gain—in other words, looters who worked covertly before the conflict. In Syria, their means of recovery ranged from metal bars to detect voids in the ground and metal detectors to magical/superstitious or religious invocations. Such groups communicate with each other and benefit from their experiences throughout Syria, and sometimes recruit experts from outside Syria. When these regions were no longer within the control of the Assad regime, these groups began to operate more easily and actively but remained semi-covert. When ISIS took control of the region, these groups found in ISIS a new partner to work with, and their expertise was sometimes exploited by ISIS and other organizations for their knowledge and networks.Footnote 40

ISIS’s destruction was different, however, because of the systematic way in which it was organized. When ISIS entered Manbij, one of our informants told us that ISIS fighters had broken some of statues in the public park of Manbij, and, during one of our visits to the city center, we found that ISIS had turned the archaeological bath from the Ottoman period into the headquarters of the media office. Later, ISIS founded the Diwan Al-Rikaz (usually translated as the Department of Underground or Natural Resources) in Syria, which was responsible for collecting precious resources from underground, such as oil, gas, phosphate, and cement. Antiquities were not part of the work of the Diwan Al-Rikaz during the first four months of ISIS’s control of the region, but they did regulate them. During that time, digs were conducted by groups that were given permission from the Diwan Al-Rikaz to search for ancient “treasures,” rather than antiquities, within the city.Footnote 41 During this period, the concept that the Diwan Al-Rikaz had of al-Athar (antiquities) meant only gold and precious metals such as gold or silver, precious stones, and coins. They did not yet care to monetize other archaeological objects such as pottery, mosaics, or stone statues, and our informants confirmed to us that ISIS destroyed the faces of the mosaic in the Syriac Church (Figures 3 and 4) and that they broke some of the statues in the Park of Manbij as noted already (Figure 5). ISIS conducted several digs to search for treasures within the city of Manbij—for example, under the Hall of the Sondos, in an area known as the citadel in the middle of Manbij, and in the Roman and Byzantine tombs south of Manbij. During this time, any emir or leader in any town or sector in ISIS’s territory was able to give a verbal or written license to dig for al-Rikaz (treasures).

Figure 3. Mosaic near the Syriac Church of Manbij before the faces were destroyed (the photo was taken by an ISIS intermediary who sent it to the author on 22 December 2015).

Figure 4. Mosaic in Figures 3 after the faces were destroyed by ISIS (the photo was taken on 26 August 2017 and sent to the author on 15 July 2019).

Figure 5. Statues of the main street of Manbij. Some of these statues had been defaced by/under ISIS and have now been collected and re-erected along a main road in the city (photo taken by one of my volunteer team members on 15 July 2019).

ISIS continued every effort to extract money from taxes on al-Rikaz, eventually expanding its remit. Then, in September 2014, ISIS established its Qasmu Al-Athar, which marked an important turning point in the destruction of antiquities that supposedly contradicted its ideology and in the looting of pieces that were consistent with its ideology (that is, treasures), and this led to the full exploitation of all archeological sites and artifacts in its territory. This shift in policy may be traced to a number of motivations. First, ISIS may have realized that the money stolen from banks and the revenues from oil sales could not be replenished and, indeed, would diminish over time.Footnote 42 Especially after the formation of the international coalition led by the United States in September 2014, therefore, other sources of income needed to be activated. In the words of one analyst, “ISIS has been creative in coming up with new sources of revenue. Antiquities weren’t even on my radar a year ago, and now look where they are, ISIS could come up with revenue sources that we aren’t even thinking about.”Footnote 43 Second, the concept of al-Rikaz evolved to include all ancient artifacts. I believe the development of this concept was due to the arrival of new foreigners and Iraqi staff to Manbij area who had experience in antiquities. One of the workers who dug with ISIS told me that the method of digging changed and that they began to care about all that was extracted, even the pottery that was considered cheap. Third, increased demand for digging licenses to search for ancient treasures raised the percentage of the profits that the Diwan Al-Rikaz received from the discovered pieces, which prompted them to develop this source of revenue.Footnote 44 Fourth, the appearance of a large number of dealers, mediators, and smugglers in ISIS-controlled areas, who were willing to take advantage of the digging licenses, served to revive the market in antiquities and enable the retrieval of antiquities to become a viable economic activity for many people in the Manbij area, who often lacked other means.

In order to maximize antiquities as a source of income, ISIS issued its Administrative Order no. 5 on 13 September 2014, giving exclusive responsibility for antiquities to the Qasmu Al-Athar. This order stipulated that it was prohibited for any brother of the Islamic state to excavate antiquities or give a permit to anyone from the public without receiving a stamped permit issued from the Antiquities Division of the Diwan Al-Rikaz. Any previous assignment or permit given to any one was then considered null, no matter who the issuing source might have been, and any holder of such a permit must report to the Antiquities Division of the Diwan Al-Rikaz to obtain a new and official permit.Footnote 45

During unstructured interviews in 2015 with a number of laborers who worked with the digging workshops run by ISIS during this time, they told me that they were no longer able to go to work in Lebanon because of the regime’s restrictions and the security forces that would arrest them and force them to fight on the fronts. They could not go to Turkey because ISIS had prevented them from traveling without its consent. The workshops provided job opportunities for young people with daily wages ranging from 1,500 to 2,000 Syrian pounds (between US $5 and 7), which was enough to buy one meal for a family of five people. Three of the 15 workers I met told me that they had worked within ISIS workshops and other independent workshops that were licensed by ISIS and were paid only if they found something, but others worked on a daily wage that did not depend on results. After the completion of the digging, they sold the artifacts and were paid 20 percent of the value by the Qasmu Al-Athar. Thus, the work in digging and trading in artifacts became a source of income for many young people who were prevented by ISIS from leaving these regions and going to the “infidel” countries like Turkey and Lebanon to work.

While there is no text in the Koran or the Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad ordering or urging the destruction of monuments, ISIS used the incident of the Prophet’s destruction of the idols in the Kaaba and Mecca to justify its own destruction of heritage sites. Thus, at the same time that they were licensing and taxing antiquities looting, they were destroying other antiquities for supposedly ideological reasons. Some antiquities, such as statues as well as ancient temples, Sufi mausoleums, and other supposed symbols of idolatry and polytheism, were targeted for destruction. For example, in Manbij, the statues that were in the city’s garden and many of the Sufi mausoleums were destroyed by ISIS, including Sheikh Aqil’s shrine in the south of Manbij and the shrine of Sheikh Aruda at Mount Aruda in the southern part of the city (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The shrine of the Sheikh Aruda before ISIS (two images at top) and after ISIS invaded (image below) (photo taken by the author in 2019).

ISIS’s ideology came from its adherence to Salafism, an extremely conservative sect of Sunni Islam that focuses on a so-called return to the ways of the ancestors with a more fundamentalist approach to Islamic religion. ISIS has strongly applied the standards of Salafist Islam to its citizens in the Caliphate state. However, when it comes to finances, ISIS has been extremely hypocritical, and its extremism has turned into a pragmatic approach that is ready to deal with all kinds of so-called infidels. Large deals (involving oil, wheat, and food) have been established between ISIS and the Assad regime through Hussam Ahmad al-Katerji, a powerful businessman and member of the Syrian People’s Assembly (Syrian Parliament), and ISIS has facilitated the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partîya Karkerên Kurdistanê [PKK]) and the People’s Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel) to access markets controlled by the regime. ISIS has allowed convoys to cross its lands, despite considering both the Assad regime and the PKK to be apostates and infidel.Footnote 46 ISIS was arresting or killing all those who were sympathetic to, or dealing with, the Assad regime and PKK while simultaneously dealing with all these groups itself, for transactions worth millions of dollars.Footnote 47 Thus, it is possible to see ISIS’s relationship with, and regulation of, antiquities as part of its larger modus operandi, which has aspects that have sometimes been contradictory and motivations that are sometimes ideological, propagandistic, political, and financial.

The Qasmu Al-Athar of Manbij and Its Functions

The Qasmu Al-Athar of Manbij (QAM) within the Diwan Al-Rikaz was initially located in the Manbij Hotel behind the cultural centre in the middle of Manbij and subsequently moved to another building opposite the Park of Almansour. All the ISIS offices changed locations regularly, probably because of security precautions, to avoid targeting by the international coalition, and, by 2016, the QAM moved to a flat on Al-Bareed Street and then to a flat north of the Dawwar Alsab’a Bahrat (Seven Fountains Square) on North Althalatheen Street in the west area of Manbij (Figure 7). During this time, I remained in Manbij. Through a number of informants, including many meetings between February and May of 2015 with antiquities dealers, middlemen and workers who worked with QAM on digging works and through an informant who personally knew the director of the QAM, I obtained information on their work.

Figure 7. The exterior of the Qasmu Al-Athar in Manbij, as written on the banner in Arabic: “Diwan Al-Rikaz – Qasmu Al-Athar – Wilayat of Aleppo (photo was taken by the author on 12 August 2015).

The QAM had seven staff members—a director, an assistant director, and five staff members—and each of them was responsible for one of the subdistricts, which, according to the administrative division of the Assad regime, were Manbij, Abu Kahf, Abu Qilqil, al-Khafsah, and Maskana. The director’s name was Abu Qaswara, who was a Syrian from the Manbij area.Footnote 48 The staff members each supervised the granting of permission for digging, the transportation of antiquities, follow-up “excavation” work, the administration of all trade in antiquities, communication with experienced antiquities traders in the region, the collection of artifacts, and the confiscation of antiquities that were extracted or transferred without prior written permission from the QAM. This information obtained from verbal interviews matches that the documentary evidence gathered from other sources. For instance, a document from the Abu Sayyaf Archives describes the functions of the QAM as being the marketing, excavation, exploration, and identification of new sites as well as the exploration and identification of known sites.Footnote 49

Through unstructured interviews with people who obtained digging licenses from the QAM, which I conducted when I was in Manbij between 25 February 2015 and 27 May 2015, I obtained further information on their policies and administration. In this section, I will detail what I was told about the structure and regulation of these licenses. The policy of the Diwan Al-Rikaz was based on granting digging licenses to the citizens of the Islamic state in return for al-khums (one-fifth). In Sunni Islam tradition, a khums includes a 20 percent tax paid on business profit and on minerals extracted in regions under the control of the state. Khums is different and separate from other Islamic taxes such as zakat (tax), which is one of the Five Pillars of Islam; zakat is a religious duty for all Muslims who meet the necessary criteria of wealth to help the needy) and jizya (a “head tax” or “poll tax” that is paid by non-Muslim populations to their Muslim rulers), which means that those who hold licenses must pay 20 percent of the price of the discoveries as tax to ISIS.Footnote 50 The applicant is required to pay between 50 and 100 thousand Syrian pounds to the QAM before starting any digging to ensure the payment of workers’ wages for those who dig and for the staff of the QAM supervising the digging. The permit holder is responsible for appointing the workers and paying them and for paying supervisors from the QAM. The supervisor was often one person and, more rarely, two people. The fee was deposited with the head of the QAM who was the director and accountant at the same time, ostensibly to protect the rights of workers and supervisors.

The people who received digging permits from the QAM all reported the same information: the license itself was granted free of charge. The land to be excavated had to be the property of the applicant or ISIS property. If the land was not the property of the applicant, they must obtain the written consent of the landowner. It was also stipulated that the digging must not cause any harm to any Muslim.Footnote 51 If the applicant requested any kind of assistance from the QAM (digging tools, a bulldozer, expert consultants, workers, or the use of a metal detector), they were charged fees for these services that had to be paid in cash to the QAM in accordance with the prior arranged agreement between the parties. The representative of the QAM informed the QAM of all the results of the digging, either verbally or in writing.

The applicant had to bear all the expenses of the work from start to finish and undertake to pay the legal share of the earnings to the QAM, which would be 20 percent of the value of the discoveries. An informant who knew Abu Qaswara personally told me that Abu Qaswara was the individual responsible for determining the value of the artifacts and that he depended on Internet sites that display the prices of artifacts online. According to the same informant, Abu Qaswara and his team had experience in antiquities and could distinguish between originals and fake artifacts; they also sometimes consulted experts from Egypt, Iraq, and Morocco. However, in determining the price of the artifacts, their expertise was weak.

After recording the artifacts that had been discovered to the QAM’s office, the applicant was given a period of between two and three months to sell the artifacts. The piece was sold through the QAM, which took a 20 percent share and an additional percentage as a commission. If the applicant could not sell the pieces during this period, the pieces were handed over to the QAM, which in turn searched for buyers inside and outside Syria at a higher rate of commission. If the buyer was outside the borders of the state, the Diwan Al-Rikaz facilitated the transfer of artifacts to the nearest point within the Islamic state. Punishments existed for looters who acted without receiving permission, and anyone who dug an archeological site or transported antiquities without the approval of the QAM had their digging tools and artifacts confiscated and was punished by flogging.

In establishing the Qasmu Al-Athar, ISIS attempted to emulate the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums in the Assad regime. In each sector (region), ISIS has established a Qasmu Al-Athar, which is similar to the subdirectorates in each governorate of the regime. The organizational structure of the Qasmu Al-Athar is also very similar in terms of the division of government directorates, comprising the Department of Administration, the Department of New Site Exploration, the Department of Excavation, and the Department of Marketing. This information was contained in one of the documents found in the Abu Sayyaf Archives.Footnote 52 The informants and documentation gathered here show that ISIS has succeeded in designing a system of government that combines its extremist ideology with a dictatorship. It has drawn on local expertise, university students who have left their universities because of the war, unemployed university graduates of all disciplines, and former government employees who have left the institutions of the Assad regime and who have experience in administrative and institutional work. ISIS also has benefited from the employment of some of the guardians of archaeological sites who were working in the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums and had knowledge of archaeological sites and treasures. ISIS also has recruited local experts who knew the area well, and some of them have worked in excavation with foreign archaeological missions and have experience in excavation and antiques. ISIS also has benefited from the government buildings of the Assad regime and made them offices for its administration, changing the names of institutions to Islamic names.

The management of all activities related to antiquities in these facilities was improved after Qasmu Al-Athar became the exclusive authority. Before ISIS took over the system, activity was random and any emir, wali, military commander, or fighter in ISIS could grant a license to dig for the search of antiquities and treasures, but once the Qasmu Al-Athar became the exclusive authority for all activities related to antiquities, any previous assignment or permit was considered null, and any holder of such a permit had to report to the Qasmu Al-Athar to obtain a new and official one. ISIS prohibited any excavation, trade, or transfer of antiquities without the approval of the Qasmu Al-Athar. ISIS has also imposed sanctions on those who violated its instructions.

The Documents and Evidence of ISIS’s Antiquities Administration: Permits and Receipts

In addition to the testimonies gained verbally that are discussed above, the team of volunteers with whom I worked collected a number of documents proving ISIS’s administration through the Diwan Al-Rikaz and the Qasmu Al-Athar in facilitating the looting of antiquities, a number of which I will discuss here (photos and full translations appear in the appendix of documents that follows this article). Specimen 1 is a digging license given to a person in a village in Manbij that allowed him to search for antiquities and al-Rikaz. Through another one of the documents, Specimen 2, it can be seen that ISIS had begun to allocate a budget for the QAM in order to enable it to carry out its own digging, which had previously depended on the collection of taxes from those who were digging themselves and selling artifacts.

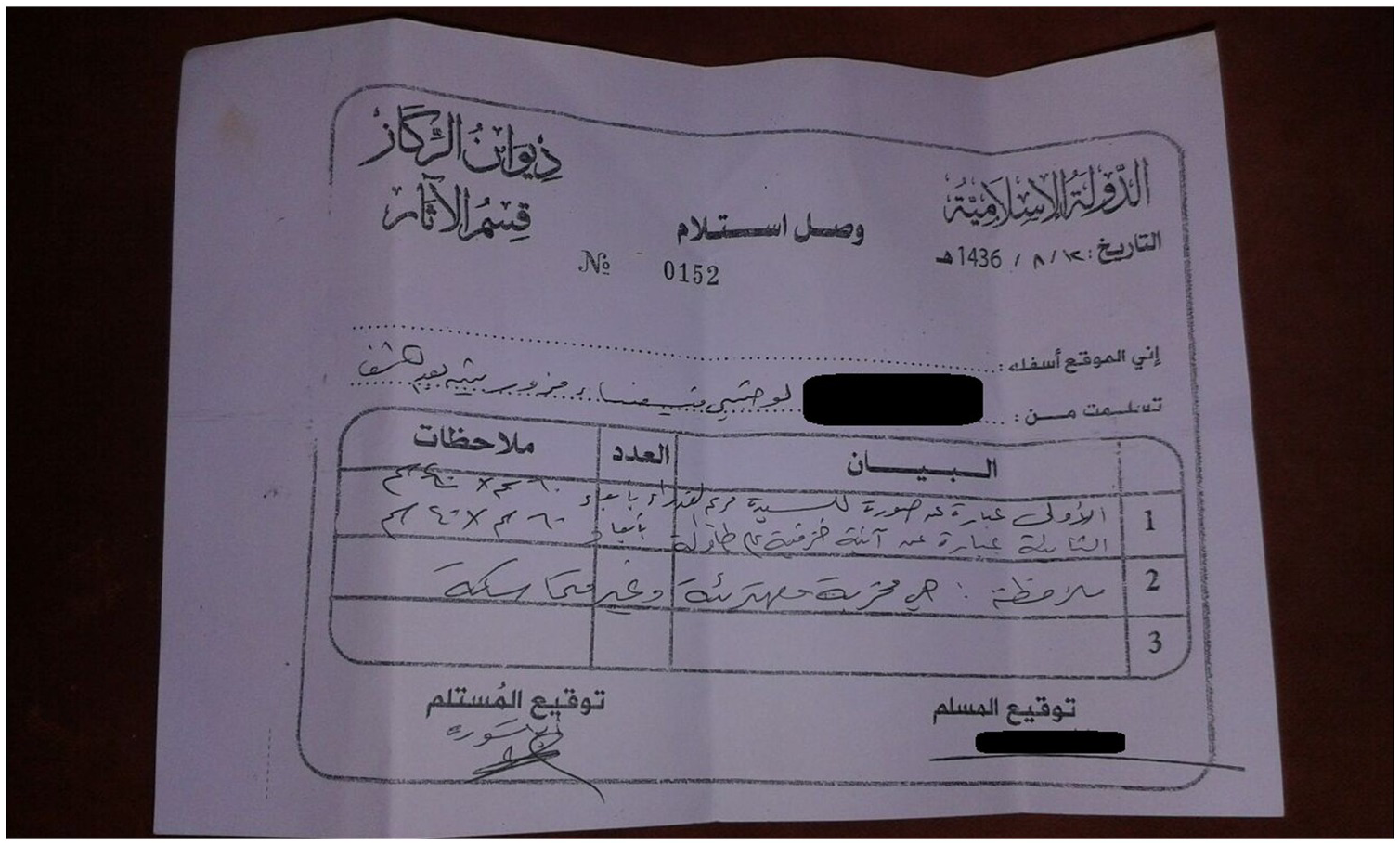

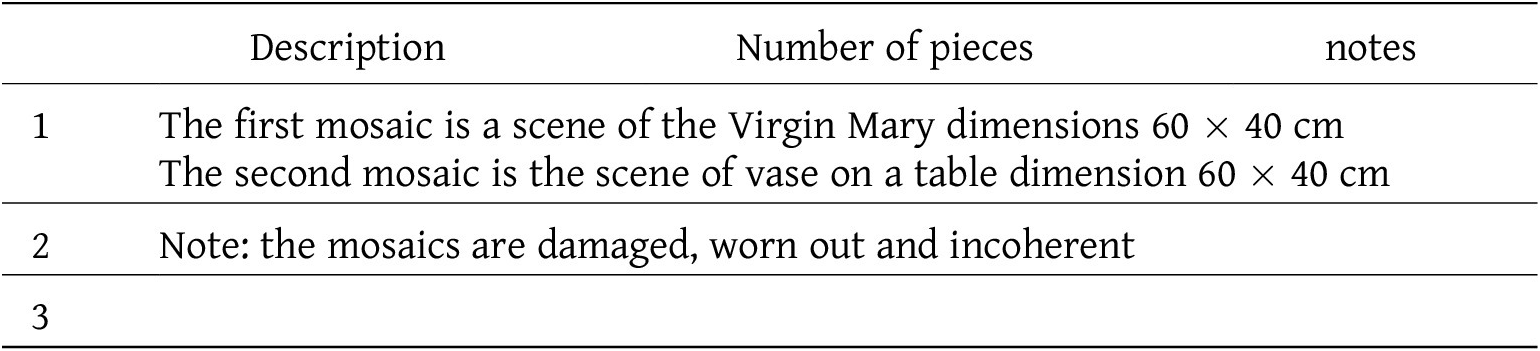

ISIS wanted to take full control of the antiquities market in its regions. It collected hundreds of artifacts by urging people to hand over their artifacts that had been extracted without ISIS’s permission or knowledge. In the event of trafficking or the possession of any artifact by any citizen without the knowledge of the QAM, it would be confiscated and the offender would be punished with a penalty ranging from a fine to flogging or imprisonment. Many people thus handed over artifacts to the QAM, and everyone who delivered an artifact to the organization was given a receipt. This receipt proved that the holder had handed these pieces in in order not to be punished. In Specimen 3, it is further evident that ISIS was responsible for collecting artifacts in this area. This example documents an instance where an inhabitant of a village near Manbij handed in two mosaic panels to the QAM, and the receipt was issued to demonstrate that they held no antiquities for which ISIS could hold them liable because to do otherwise would be considered illegal.

Other licenses demonstrate the high level of regulations of activities related to antiquities looting and the extent of the related bureaucracy. For example, Specimen 4 shows a license for a bulldozer owner to use his bulldozer on behalf of the QAM at the sites of Meshrefet Anz (Khirbet Al-Anz) and Um Hdjara under the supervision of Abu al-Hasan, who was responsible under the QAM in the area of Maskana, south of Manbij. Without the permission of ISIS, even the bulldozer owner would have been under immediate mortal threat if they did not have written proof that they were operating with approval. Specimen 5 shows the approval of Abu Al-Hassan to extend the digging for an additional month at a site, based on prior approval from the QAM, further documenting the bureaucracy of site permissions.

These documents from Manbij are part of a broader pattern that is visible throughout Syria. ISIS has been preventing any digging or trade in antiquities without its consent or supervision to ensure that it is able to extract related revenues. For example, on 2 July 2015, ISIS militants in Manbij intercepted two men smuggling funerary sculptures from Palmyra to the north Syrian border. They confiscated the smuggled artifacts and destroyed them in the public square and punished the smugglers.Footnote 53 No doubt, this action was intended to send a message to all those working in the antiquities trade to obey orders and work under the supervision of the QAM: ISIS social media accounts released photographs depicting militants destroying the Palmyrene funerary busts (Figures 8 and 9). Militants were shown displaying the statues to a crowd gathered in the central town square and then breaking the statues with sledgehammers.Footnote 54 Indeed, after Palmyra fell into ISIS’s hands in May 2015, the Diwan al-Khidamat (Department of Services) issued a notification prohibiting the moving of, and dealing in, artifacts found in the town of Palmyra outside the borders of Wilayat Homs. Similarly, some receipts recovered from the Abu Sayyaf raid refer to antiquities sold in Wilayat al-Kheir (Deir ez-Zor province).Footnote 55 Three documents issued by the Diwan-Al Rikaz in Syria published by Ayman Jawad al-Tamimi also confirm that ISIS was monitoring the trade of antiquities and was confiscating smuggled objects as well as granting licenses for drilling and the use of metal detectors.Footnote 56

Figure 8. The destruction of the Palmyrene statues in Manbij’s public square by ISIS on 2 July 2015 (courtesy of the Syrian Human Rights Committee, “ISIS Destroy Palmyra Ruins,” 3 July 2015, https://www.shrc.org/en/?p=25317 [accessed 22 April 2021]).

Figure 9. The destruction of the Palmyrene statues in Manbij’s public square by ISIS (photo courtesy of R. Gladstone and M. Samaan. “ISIS Destroys More Artefacts in Syria and Iraq,” New York Times, 3 July 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/04/world/middleeast/isis-destroys-Artefacts-palmyra-syria-iraq.html [accessed 22 April 2021]).

With the creation of the Qasmu Al-Athar, ISIS was making every effort to be able to extract money from antiquities. It began to conduct surveys to determine which archaeological sites in which to work, taking advantage of the presence of local antiquities dealers as well as experts from Morocco, Iraq, and Egypt. In Manbij, this process began with the Syriac Church in the industrial area east of Manbij, where a Syrian-French expedition headed by Justine Gaborit and Humam Saad had carried out emergency excavations in 2009 and 2010.Footnote 57 ISIS used a bulldozer on the site of the church in order to look for mosaics that they had been informed had been found, causing extensive damage to the archaeological site (Figures 10 and 11).Footnote 58

Figure 10. ISIS bulldozing the area excavated by the French expedition in the industrial area (the photo was taken by a volunteer team member on 6 August 2015).

Figure 11. ISIS’s destruction of archaeological layers in the area excavated by the French expedition in the industrial zone (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 6 August 2015).

The teams under the direction of the QAM began to spread throughout the region. For example, digging was undertaken at the sites of Jebel Khalid, the Shash Hamdan tomb and its surroundings, and the tombs of Emar, Jabel Um Al-suruj, Tell Arab Hassan, Dur Dada, and Tell Meshrefet Anz. Each team consisted of at least 10 workers who were distributed at different parts of the site. At the large sites, the teams used a bulldozer to remove the rubble. They dug trenches inside the site after which the workers followed with hand digging once the archaeological layers were revealed. The scale of the destruction was enormous, destroying walls and the archaeological layers, but they were successful for the QAM because thousands of artifacts were found in this manner. I later documented some artifacts that one of the intermediaries told me were from Tell Meshrefet Anz. We also attempted to document many of these sites after they were destroyed in an attempt to provide witness to the destruction, but many remain undocumented. Workers were prevented by ISIS from bringing their phones to the digging sites, and it was therefore impossible to document the acts of looting directly. We succeeded in documenting only three sites between 9 September 2015 and 3 October 2015, and the remaining sites were documented after the completion of digging by ISIS.

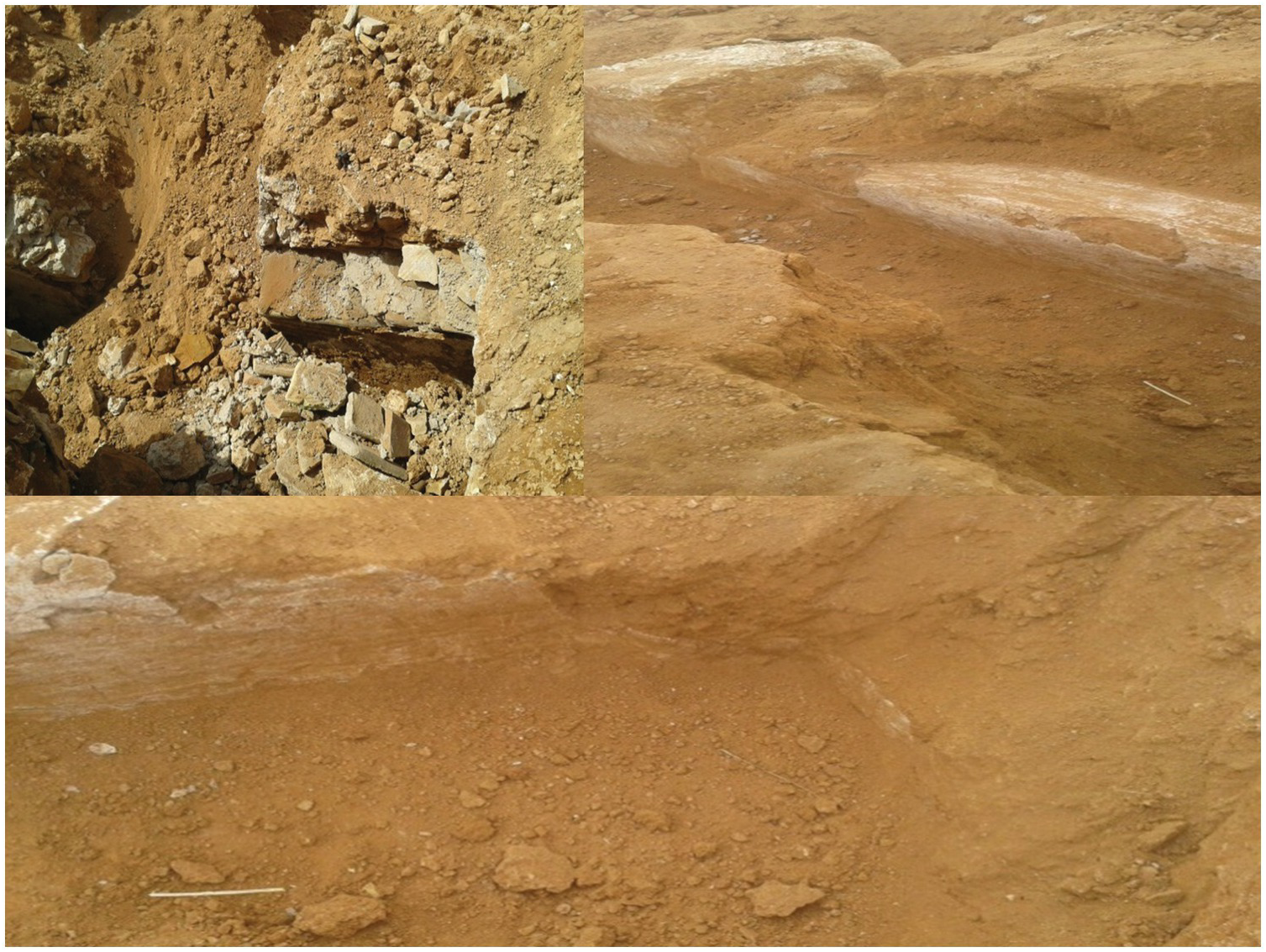

Meshrefet Anz Site (Khirbet Al-Anz)

One of the archeological sites that we documented during this work was the site of Meshrefet Anz. Meshrefet Anz is located 75 kilometers to the south of Manbij, 11 kilometers south of the town of Maskana, and 10 kilometers west of Lake Al Assad (see Figure 1). It is an archaeological tell site that rises four meters from the surface of the village and occupies the southwest corner of the village of the same name. Due to its large size, the site was subject to several acts of vandalism and looting by the Diwan Al-Rikaz. In November 2014, the site was subjected to large-scale bulldozing by ISIS in the search for what they considered to be treasure. Due to the large size of the hill and the amount of landfill, the QAM extended the work for another month under the supervision of Abu Al-Hassan, beginning on 10 December 2014 and ending on 8 January 2015. The text of the permit extension notes that Abu Al-Hassan was allowed to continue the digging for one more month based on the previous permission, which lasted from 17.02.1436 until 17.03.1436 Hijra (equivalent to 10 December 2014 until 8 January 2015) (see Specimen 5).

An informant told us about these works at the site and the number of artifacts that ISIS had pillaged from it and the surrounding sites on the Euphrates, so we began to gather information about the subject, but we could not get photographs that documented the damage. However, we were able to document one of ISIS’s warehouses that was packed with collected artifacts from different locations in the Euphrates area (Figures 12, 13, 14, and 15). After a long process of coordination, we managed to communicate with the informants from the area who started working with us to document violations against the antiquities in the area of Maskana south of Manbij and specifically to document the activity with photographs. At the beginning of August 2015, a resident of the village told the QAM that there was a landslide in front of his house beside the site of Meshrefet Anz. And, indeed, on 19 August 2015, ISIS returned to work at the site of Meshrefet Anz. Specimen 2 shows that the QAM received funding from the Diwan al Rikaz on 16 August 2015. While the Specimen 4 shows that the QAM contracted a bulldozer owner on 20 August 2015 to work on the sites of Meshrefet Anz and Um Hjara.

Figure 12. One of ISIS’s warehouses that, according to our informants, was packed with collected artifacts from different locations in the Euphrates area (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 17 September 2015).

Figure 13. One of ISIS’s warehouses (the same as pictured above in Figure 12) that, according to our informants, was packed with collected artifacts from different locations in the Euphrates area. The photo shows different types and sizes of pottery vessels (photo taken by one of my volunteer team members on 17 September 2015).

Figure 14. Another location within the same ISIS warehouse that was packed with collected artifacts from different locations in the Euphrates area. In this photo, different types and sizes of pottery vessels and small human and animal figurines are visible (photo taken by one of my volunteer team members on 17 September 2015).

Figure 15. Another location within the same ISIS warehouse, showing different types of bronze weapons (the photo was taken by a volunteer team member on 17 September 2015).

A member of our documentation team visited the site during the digging and, with the help of one of the workers, was able to take pictures and document the destruction at the site. The photographs were taken secretly so the angles of the pictures are not clear enough to reveal the full extent of the vandalism that had occurred on the site. Despite their limitations, they remain useful as a record, testifying to what was going on in one of Syria’s heritage sites under the occupation of ISIS. It seems that ISIS has benefited from its previous experiences and so is developing and accelerating its looting. After conducting a survey in the area of the collapse with a metal detector, it chose two focus points at the site. At point A (as noted on Figure 16), it instructed the first group of workers to dig in the area of the collapse. At point B (on Figure 17), the second group chose a location at the bottom of the tell so that the quantity of soil backfill was limited in order to reach the artifacts more quickly. At point A (the collapsed area), photos taken on 11 and 12 September 2015 where the landslide had occurred reveal the likely presence of a Byzantine burial site, covered with a slab made of white limestone that was carved with a cross (Figure 18). According to the information obtained later from the workers, it was found that the tomb it decorated was built of red brick and contained four graves. The ISIS workers destroyed the cross and the structure of the tomb and destroyed four inhumed skeletons. Later, ISIS’s digging revealed a large portion of the associated church, and it became evident that the tomb was part of a religious complex, located near the southeastern corner of the church directly under its foundations, and that the tomb’s entrance was at a lower level of the same structure.

Figure 16. Meshrefet Anz, “Point A” before the digging began (photo taken by one of my volunteer team members on 11 September 2015).

Figure 17. Meshrefet Anz, “Point B.” The digging at the bottom area of the tell (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 18. Likely a Byzantine tomb covered with a slab made of white limestone, decorated with a carved cross (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

After bulldozing the hill at the bottom of the tell area, the QAM’s workers surveyed the area with a metal detector (Figures 19 and 20). They used a backhoe to dig trenches (Figure 21), which revealed multiple archaeological levels; a layer of black ashes on the whole level of the church, ranging from 10 to 50 centimeters in some areas (Figure 22), and, in the apse area, a layer of brown pottery tiles appeared, which were each 35 centimeters square. Under the panel, we can see two levels (Figure 23). The ISIS workers began digging with axes, mattocks, and shovels. Based on the description of one of the workers as well as one of our team members, who photographed the excavation work, we can summarize the results of these excavations, despite ISIS’s lack of concern for the archaeological results, which could not be monetized.

Figure 19. Metal detectors in use by ISIS’s digging teams (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 20. The photo shows Abu al-Hasan, the representative of the Qasmu Al-Athar and the digging work at the sites of Meshrefet Anz and Um Hjara in the Maskana area, next to him appears a metal detector (photo was taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 21. Digging trenches with a backhoe at Meshrefet Anz (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 22. A layer of black ash across a building that is probably a church, indicated by arrows. Digging trenches with a backhoe at Meshrefet Anz (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 23. Two levels of masonry under the white panel indicated in Figure 19 (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

The excavation revealed a building foundation for a church measuring approximately 40 meters long and about 22 meters wide (Figure 24). The walls are built of stones covered with a layer of white plaster (Figure 25). In the northeastern corner, a curved wall with a radius of about two meters can be seen (Figure 26), and a white limestone platform (probably the base of the altar) was discovered in the southern section of the middle of the floor of this curved wall. It is about 70 centimeters long, 40 centimeters wide, and 12 centimeters thick, with an inscription in ancient Greek, of which several letters are clear. At the corners of the panel are four square cavities with a depth of 15 centimeters, a length of 20 centimeters, and a width of 20 centimeters that comprise the bases of pillars to carry the altar (Figure 27). The digging also revealed the existence of drainage channels, but, unfortunately, it was completely destroyed by the bulldozer (Figure 28).

Figure 24. The plan of the church according to a description provided by one of the workers in 2015 and by one of the members of our volunteer team (photo taken by a volunteer team member in 2019).

Figure 25. Photographs indicating plaster levels and plaster-covered walls (photo taken by volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 26. The curved wall in the northeastern corner (photo taken by volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 27. A white limestone platform with an inscription in ancient Greek (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

Figure 28. The destruction of ceramic drainage channels due to the digging work of a bulldozer (photo taken by a volunteer team member on 12 September 2015).

The site of the Meshrefet Anz may be used as a model to understand how the QAM has looted archaeological sites in Manbij and its surrounding countryside since the photographs document the extent of the damage to the site. These photos record how the QAM has completely destroyed the structure of the burials as well as the walls of the church and the limestone block with its inscription. Except for the trail of receipts for ISIS’s authorization of its work, and the photographs and information gathered by our group, this heritage site was unrecorded. The land was bulldozed, and the drainage pipes were completely destroyed. ISIS used all available means to loot and destroy the site with the use of manual digging, heavy machinery, and metal detectors.

Conclusions

ISIS established the Qasmu Al-Athar to control all activities related to archeological sites and antiquities. The plundering of antiquities is no longer limited to the collection of taxes by granting licenses to citizens wishing to dig for treasures in exchange for al-khums (that is, 20 percent of the price of the artifacts discovered). The QAM is now employing a cadre of experts in antiquities, each of them responsible for an area in Manbij—not those who have a knowledge of archaeology but, rather, those with a knowledge of the international antiquities market as well as local amateurs.

A range of other information on the operation of ISIS’s antiquities work was gathered from people who regularly interacted with them during 2015. The Qasmu Al-Athar has executive powers and financial resources to monitor all activities related to the revenues generated from antiquities and their regulation. All the emirs and other leaders within ISIS have been prohibited from interfering with work or activities related to archaeological sites and antiquities, which was delegated entirely to the Qasmu Al-Athar. No other part of the administration has any power or ability to intervene or to grant permits for digging or receiving artifacts. The Qasmu Al-Athar has become the supreme authority responsible for activating this source of funding by increasing digging work and by granting digging licenses to citizens, providing all expertise and facilities for them as well as the equipment and heavy machinery. The Diwan Al-Rikaz also has allocated a monthly budget to the Qasmu Al-Athar to conduct its own digging. The Qasmu Al-Athar is responsible for facilitating the movement of artifacts within its territories as well as evaluating the price of pieces and confiscating contraband antiquities or those found without the knowledge of the Department of Antiquities. This digging work is also organized by requesting the holder of the license to pay the amount of 100,000 Syrian pounds to the Qasmu Al-Athar to guarantee the payment of workers as well as its own experts and supervisors. ISIS ensured this payment in order to secure the salaries of the Qasmu Al-Athar staff from public digging because its own budget was earmarked for the digging works of Qasmu Al-Athar.

These findings corroborate and compliment the findings of other studies that utilized informants within Syria during the crisis. For example, a study by Neil Brodie and Isber Sabrine demonstrates how ISIS benefited from Syrian and Turkish smuggling networks and how officers and civilians from the Assad regime were involved in looting and smuggling artifacts from ISIS regions to the Turkish and Lebanese borders. These informants were in communication with an ISIS official who was responsible for overseeing activities related to illegal excavation and trade. This official confirmed the use of heavy machinery at sites in ISIS-occupied territory and suggested that ISIS employed 35 digging gangs, each gang composed of 45 members who work on-site in ten-person shifts. Most material was transported out through Turkey, sometimes in fuel trucks. Border guards need to be bribed, and criminal gangs on the Turkish side of the border were also paid off, and ISIS sold some material to a Syrian army officer who was able to arrange for ongoing trade and transport.Footnote 59

The collection of documents, observations, and information collected in Manbij between 2014 and 2016 presented in this article does not cover all the activities that ISIS carried out with regard to the destruction and looting of Syrian cultural heritage, but they provide us with some very important details about the nature of this activity. While the deliberate destruction of certain archaeological sites by ISIS is well known, it is because this destruction was deliberately promoted by ISIS. In the case of the site of Meshrefet Anz, it is evident that other motivations can also be present, with a similar result: the destruction and bulldozing of important archaeological sites.

The importance of documenting the site of Meshrefet Anz, even when such documentation is imperfect, comes from the evidence it provides with respect to the destruction and looting. Many such sites, which were otherwise unknown, will now remain that way. The true extent of the damage, and how many other archaeological sites have been similarly treated, is nearly impossible to ascertain, and doing so will become more difficult over time. Despite the efforts to document what has happened to archaeological sites via satellite, the lack of documentation from the ground means much information is lost about the seriousness and extent of the real destruction and the looting of dozens, if not hundreds, of archaeological sites in Manbij and the surrounding countryside. This demonstrates the urgent need to expedite the survey and documentation of the archaeological sites in the area of Manbij that were destroyed by ISIS in order to determine the extent of the destruction and looting suffered, while it is still possible to trace the physical impacts and while witnesses to the crimes committed by ISIS against Syrian heritage in this region are still present. The experience of documenting archaeological sites during the civil war in Lebanon confirms that a careful search and systematic recording strategies designed for sites destroyed by conflict or looting can provide us with much more information than previously imagined.Footnote 60

The spectacular destructions of archaeological sites in Syria by ISIS, especially at Palmyra, has gained the lion’s share of media and academic research focus. In fact, as I have demonstrated in this article, the vast majority of damage and destruction of archaeological sites in the region of Manbij has been incidental and taken place during the recovery of objects for the antiquities market. The looting of antiquities under ISIS in the Manbij area was transformed from a random, clandestine individual action into organized and systematic work with the significant participation of the local community under ISIS’s supervision, protection, and facilitation. The documents also show that the Qasmu Al-Athar has provided all necessary facilities to loot archaeological sites in order to obtain more financial resources. These facilities have included digging licenses, the use of metal detectors, heavy digging machines, and drilling supervision. This increased interest in organizing activities related to the looting of archaeological sites represents a clear recognition of antiquities as a source of revenue, especially after the difficulties faced by the oil sector due to the American-led coalition.

ISIS has institutionalized the looting and destruction of archaeological sites, through the establishment of its Diwan Al-Rikaz and the Qasmu Al-Athar. The Qasmu Al-Athar has contributed to the organization and accelerated looting primarily to collect as much money as possible. In the search for objects that can be sold, dozens of archaeological sites in the Manbij area and its surrounding countryside, covering all historical periods, have been destroyed, from prehistory to the Bronze Age and from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic periods. Some of these sites were previously unknown or unrecorded, and their loss for Syria’s heritage is immeasurable.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA), United Kingdom. For further information about CARA, visit https://www.cara.ngo/. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Jennifer A. Baird, professor of archaeology at Birkbeck University in London for all her valuable advice, suggestions, experience, and unwavering guidance during this research.

Appendix: Documents

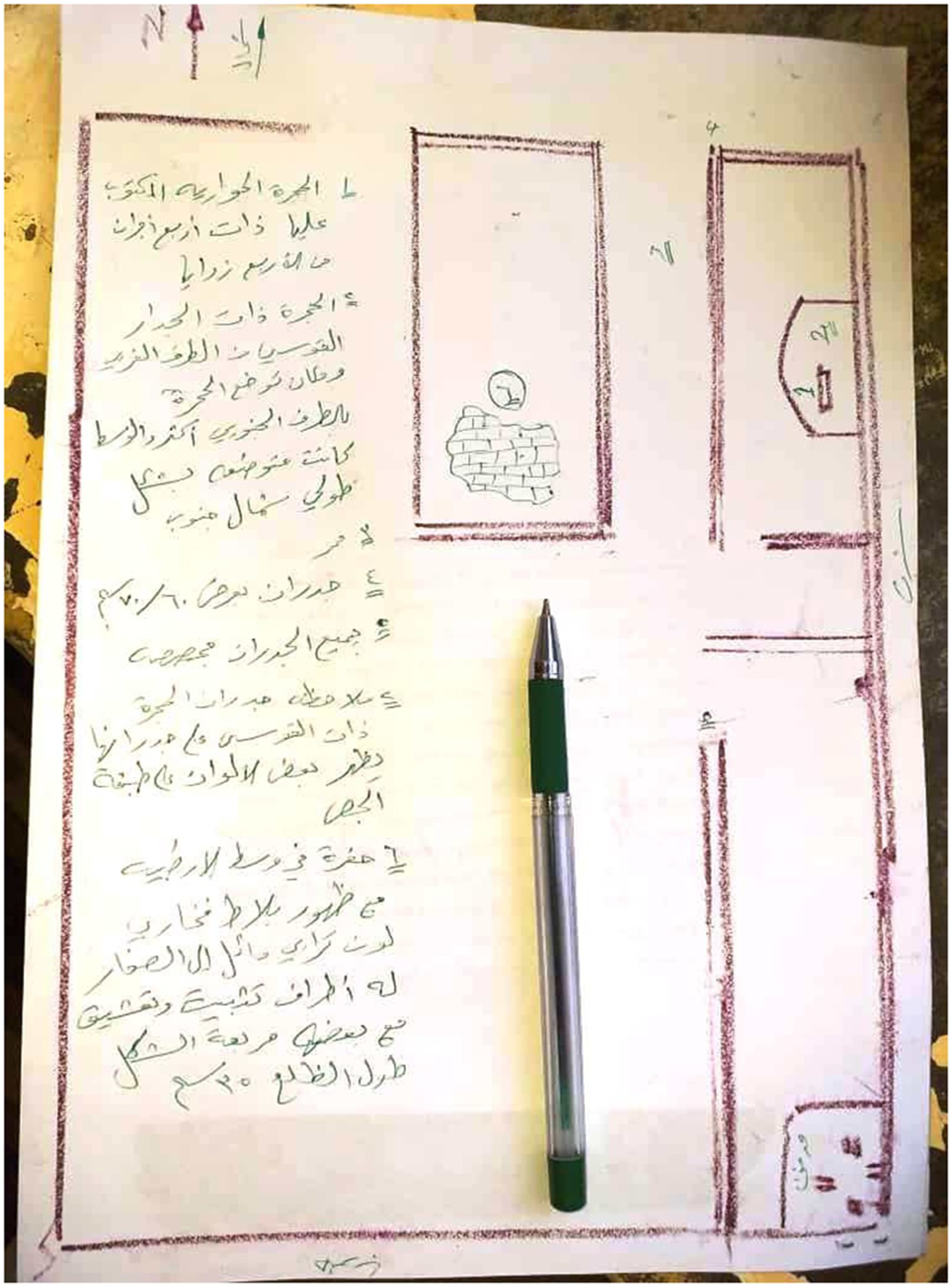

Specimen A

License digging for Al-Athar and Al-Rikaz

Date of issue: 09/01/1436 A.H, equivalent to 02/11/2014 A.D

Date of photo: 06/02/2015

Description: At the top right corner appears the flag of ISIS. The flag shows the seal of the prophet Muhammad within a white circle (Muhammed is the messenger of Allah), with the phrase above it, "There is no god but Allah". On the left of the flag are three lines of writing: In the name of God the Most Gracious, the Ever Merciful/The Islamic state/Succession on the platform of prophecy. The text then specifies the location (Aleppo State), Licence Number and Date. In the middle of the permit we see handwriting in blue which is text of the license. The name of the license holder and the name of the village was concealed here to protect their identity. Then we can see the date of issue and the name of director of Qasmu Al-Athar and his signature. In the below stamp of the Qasmu Al-Athar in blue written on it, at the top, Islamic State. In the middle, “There is no god but Allah and Seal of Muhammad within a circle (Muhammed is the messenger of Allah)”. At the bottom of the stamp there says “Idarit al Athar” (another name for the Department of Antiquities).

Translation of main text:

[In seal] In the name of God the Most Gracious, the Ever Merciful.

Succession on the platform of prophecy

In the name of God the Most Gracious, the Ever Merciful.

The brother [The name of the license holder, redacted] is allowed to dig for antiquities and al-Rikaz in [redacted] village. Provided that it does not cause harm to Muslims. 02/11/2014

Abu Qaswara [followed by his signature and the stamp of Department of Antiquities in blue]

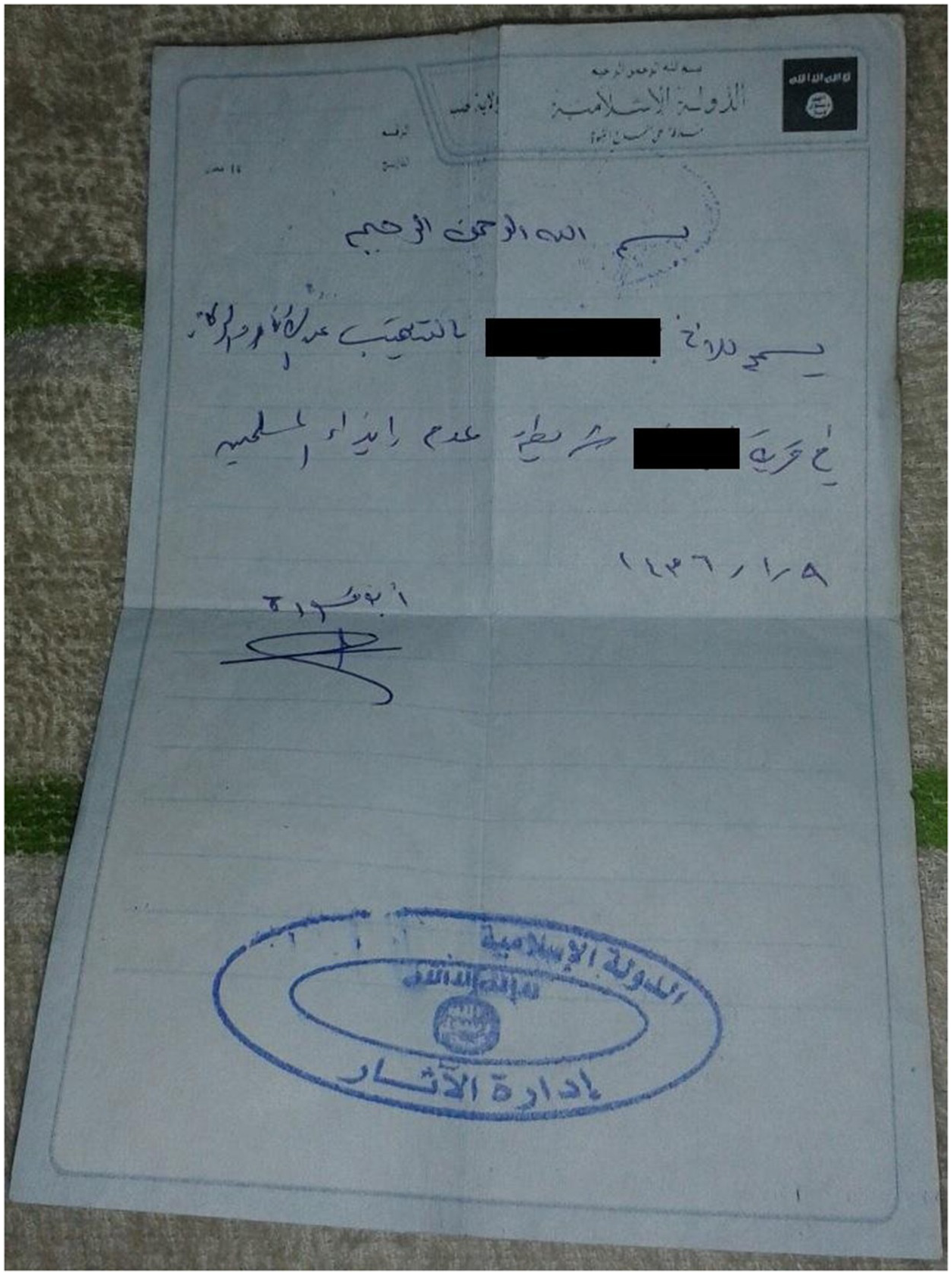

Specimen B

This document is the receipt of payment from the Emir of the Diwan Al-Rikaz in Syria (Abu Mujaheed Altounisi) to the Director of the Qasmu Al-Athar (Department of Antiquities) in Manbij.

Date of issue: 30/10/1436 A.H., equivalent to 16/08/2015 A.D.

Date of photo: 24/10/2015

Description: At the top right corner appears the phrase “Islamic State” immediately below the date of issue.

In the left corner of the top is the phrases Diwan Al-Rikaz / the Qasmu Al-Athar. In the middle, the receipt of payment and its number.

The handwritten text is the name of the sender, the recipient and the amount in the Syrian Pound and their signatures. The stamp of the Diwan Al-Rikaz/ Antiquities, Western States (Syria) – Al- Emir in red.

Translation:

The Islamic State, Diwan Al-Rikaz - Department of Antiquities

Receipt of payment No. 0083

Date 16/08/2015

I am signed below Abu Mujaheed Altounisi, I handed the Brother Abu Qasoura Al-Ansari

Amount written in $

the Amount in number in $

The amount is written in Syrian pounds two hundred thousand Syrian pound

Amount in number in Syrian pounds 200 000 Syrian pound

Note: Petty Cash for the month of November

Signature of the recipient

Stamps of the Islamic state/Diwan Al-Rikaz/ Antiquities - Western States (Syria) – Al- Emir, Signature of the giver

Notes: The writing must be clear, beautiful and understandable to others

The numbers must be in Arabic 1,2, 3 and not in HindiFootnote 61

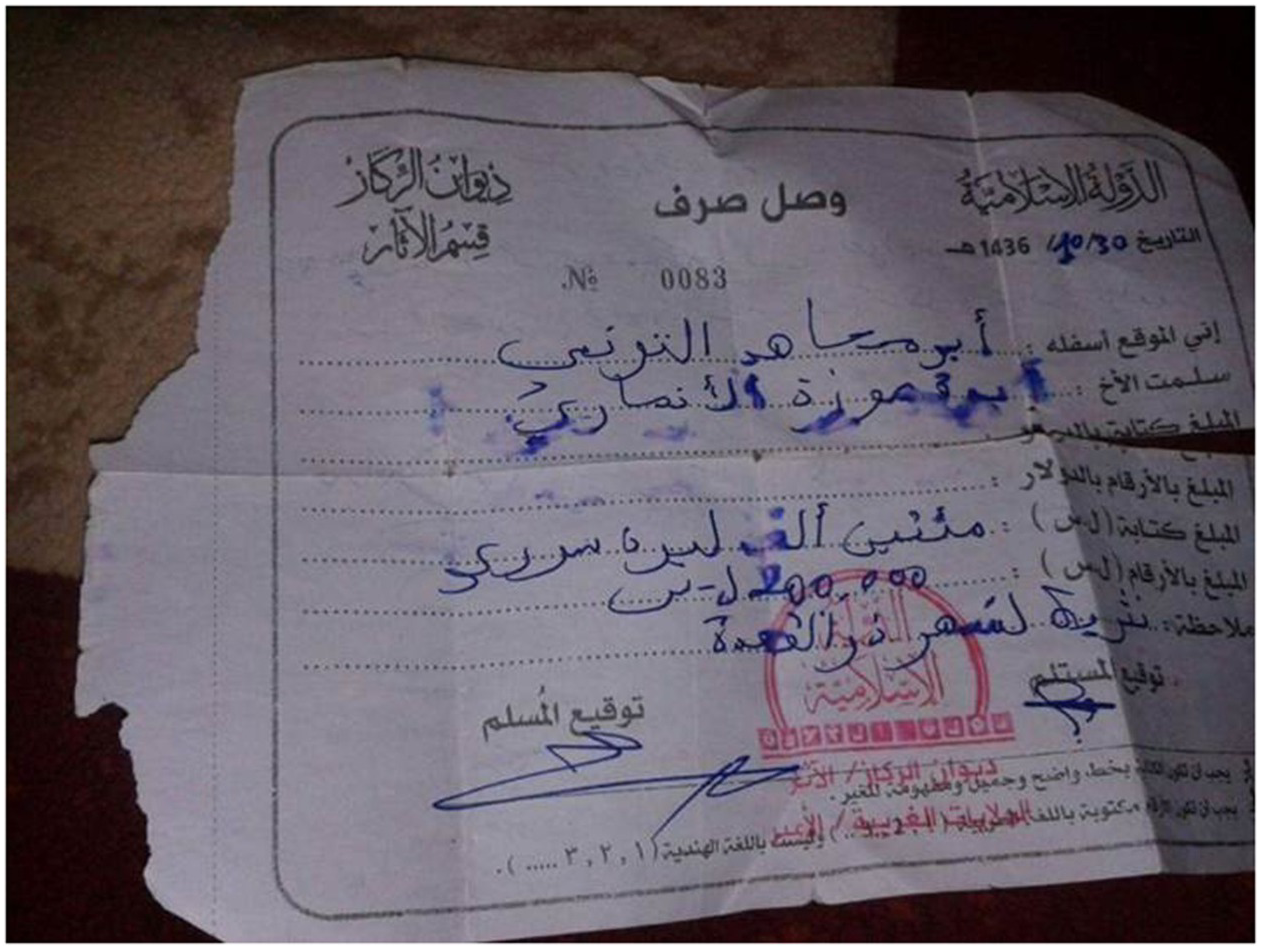

Specimen C

This document is a receipt for two fake mosaics. Where a Manbij resident handed over two fake mosaics to the antiquities department of Manbij.

Date of issue: 12/08/1436 A.H, equivalent to 31/05/2015 A.D.

Date of photo: 31/07/2015

Description: At the top right corner appears the phrase “Islamic State” immediately below the date of issue. In the left corner of the top is the phrases Diwan Al-Rikaz/Department of Antiquities. In the middle is the receipt of payment and its number. The phrases in the table are the descriptions of the two mosaic. At the bottom of the document at the left appears the name of Abu Qaswara the director of Department of Antiquities in Manbij and his signature.

Translation:

Islamic State

Diwan al-Rikaz

Department of antiquities

Date: 31/05/2015

Receipt NO 0152

I signed below ……… I received from [name of person delivering items] two fake mosaics after checking

The name of deliverer and his signature the recipient Abu Qaswara and his signature

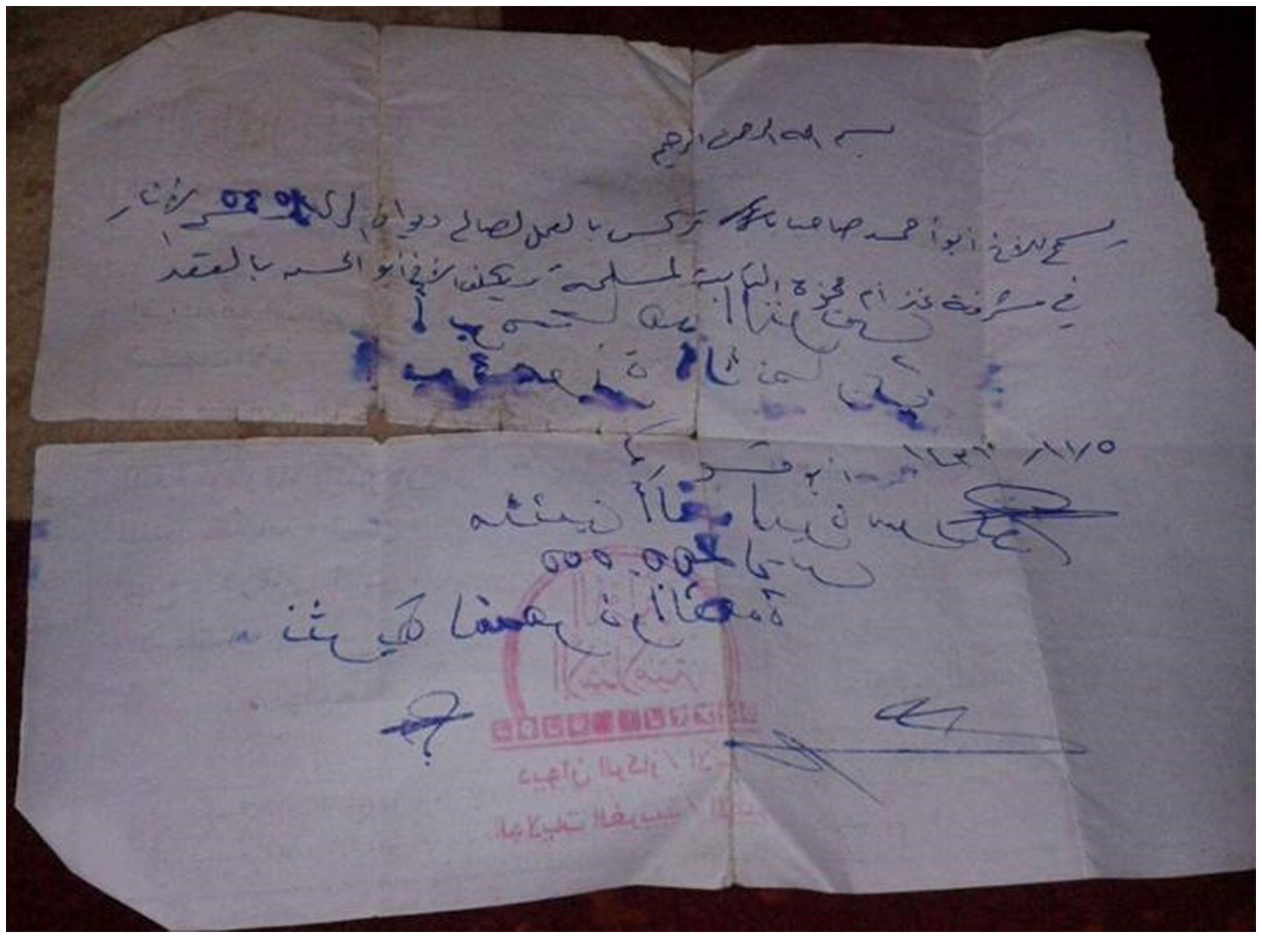

Specimen D

This document is a permission from Abu Qaswara to a bulldozer owner to work on behalf of the Qasmu Al-Athar in the site of Meshrefet Anz (Khirbet Al-Anz) and Um Hjara.

Date of issue: 05/11/1436 A.H equivalent to 20/08/2015 A.D.

Date of photo: 24/10/2015

Description: The permission was handwritten on the back of Specimen B. The document is a letter from Abu Qaswara to Abu al-Hasan, the responsible of the Antiquities Department and the digging work at the sites of Meshrefet Anz and Um Hjara in the Maskana area (Maslama area according to ISIS) south of Manbij. It says that Abu al- hassan will be responsible to prepare the contract with the bulldozer owner. At the end of the letter is the name of Abu Qaswara, head of the Department of Antiquities in Manbij and his signature.

Translation:

In the name of God the Most Gracious, the Ever Merciful.

Brother Abu Ahmed who has bulldozer is allowed to work on behalf the Diwan al-Rikaz - Department of Antiquities in Misherfet Anz - Um Hjara. The brother Abul Hassan is in charge of the contract.

Abu Qaswara [His signature]

Specimen E

This document is a license to extension of digging one more month.

Date of issue: 17/02/1436 A.H, equivalent to 10/12/2014 A.D.

Date of photo: 31/07/2015

Description: At the top right corner appears a flag of ISIS, the flag shows the Seal of the Prophet Muhammad within a white circle ( Mohammed is the messenger of Allah), with the phrase above it, “There is no god but Allah”. On the left of the flag is three lines writing: In the name of God the Most Gracious, the Ever Merciful/The Islamic state/Succession on the platform of prophecy.

In the middle of the permit, we see handwriting in blue, which is the text of the permit to dig. Then we can see the date of issue and the name of director of Qasmu Al-Athar and Al-Rikaz at Aleppo state, and his Signature. In the below, the stamp of the Qasmu Al-Athar in blue written on it, at the top, Islamic State. In the middle, There is no god but Allah and Seal of Muhammad within a circle (Mohammed is the messenger of Allah). At the bottom of the stamp there is the phrase Department of Antiquities.

The permit does not give the site name (Meshrefet Anz) because it is an extension, but the document was supplied by a team member who worked at the site. The licence remained at the site in order to verify the permission in case of a visit from members of ISIS who were not aware of existing permissions.

Translation:

The brother Abu Alhasan, is allowed to continue the digging one more month based on the previous permission, start from 10/12/2014 until 08/01/2015.

This is a mandate from us

Abu Qasswara

Director of Diwan Al-Riqaz - Antiquities in the State of Aleppo

10/12/2014

[Signature]

Stamp of the Islamic State in blue - Department of Antiquities