The courts and wealthy homes of the Sultanate states of India amassed substantial libraries. However, surviving works are relatively scarce, and any researcher working on the art of the book hopes for a discovery that will help shed light on an often obscure era of Indian art history. Between the collapse of the Delhi Sultanate following Timur's invasion and the establishment of Mughal rule was a period of just over a hundred years with no centrally controlled government, often called the ‘long fifteenth century’. Once considered bereft of artistic endeavour, this period's output is now being increasingly recognised for its diversity, ambition, and invention. This discussion seeks to demonstrate the Indian provenance of a previously unpublished manuscript: a copy of Firdausī's Shāhnāma dated 843/1440, currently in the Khuda Bakhsh Library in Patna (3787–3788). This copy of the Shāhnāma is closely related to a group of illustrated manuscripts produced in Shiraz, yet was owned by a Sultanate ruler in the state of Gujarat, Sultan Muḥammad Shāh, who reigned from 846/1442.Footnote 1 Such a juxtaposition makes the manuscript particularly noteworthy and questions previously held assumptions on manuscript production in Shiraz during the Timurid period and on the reception of Persianate literary and artistic culture in the Sultanate states of South Asia.

The study of material culture in fifteenth-century South Asia, specifically manuscript production, has been gathering momentum recently.Footnote 2 Of the small corpus of illustrated Persian manuscripts that survive, a particular group with a possible, but not certain, Sultanate provenance is still largely overlooked by scholars working on Persian manuscripts that originated from either Iran or South Asia. Barbara Brend has been a pioneer in this field with her studies of an Anthology in the Chester Beatty LibraryFootnote 3 and the Mohl Shāhnāma,Footnote 4 where she considers these manuscripts from multiple viewpoints. Her arguments that these two particular manuscripts are of Sultanate origin remain entirely plausible.

Robinson was the first to assemble a body of possible Sultanate manuscripts of various texts, previously thought of as provincial Persian.Footnote 5 Fraad and Ettinghausen published a preliminary survey of Sultanate painting, setting out the key criteria that may indicate an Indian provenance.Footnote 6 These authors argued that manuscripts that display ‘outmoded’ traits, specifically in their paintings, calligraphy, or illumination, suggest an Indian association; many of the ‘outmoded’ visual traits identified are those associated with Shiraz. There are five other copies of the Shāhnāma dating from circa 1430–50 (besides the Mohl Shāhnāma) that they attributed to the Indian Sultanates: a Shāhnāma in the National Museum in New Delhi;Footnote 7 two in the John Rylands Library;Footnote 8 and two dispersed Shāhnāmas, one of which has distinctive, large, almost square-shaped illustrations.Footnote 9

This article will challenge the notion that ‘outmoded’ traits are the only criteria for a Persian manuscript's possible Sultanate origin. It will be shown that both manuscripts containing ‘outmoded’ elements and those exhibiting only current modes of manuscript production were in circulation in India during the long fifteenth century between Timur's invasion in 1398 and Humayan's return to India in 1555.Footnote 10 During these years, several states held sway in the northern subcontinent, the most dominant being Delhi, Jaunpur, Malwa, Bengal, and Gujarat. A wide range of books was composed, written, illustrated, imported, and collected in each state. Many different modes were assimilated into book-making practices, resulting perhaps most conspicuously in strikingly diverse painting styles.

Introducing the Patna Shāhnāma

The Patna Shāhnāma comprises two volumes, with 561 folios in total. The text is written in black ink in a small and neat nasta′līq script in 25 lines divided into four columns.Footnote 11 There is substantial damage to the opening folios, and the entire manuscript has suffered from worming and damp conditions. A colophon at the end of the second volume on fol. 561v mentions the Shāhnāma was completed in 843/1440.Footnote 12

Most copies of the Shāhnāma begin with a preface, one of four main iterations. The preface in the Patna manuscript, beginning on fol. 1v, is the earliest of the four versions, which includes an introduction thought to have been written by Abū Manṣūr al-Mu‘ammarī for a prose version of the Shāhnāma in 346/957.Footnote 13 It has been suggested that the preface found in Shāhnāmas of possible Sultanate origin may determine their provenance. The argument centres around two main issues: the insertion of an episode mentioning Firdausī welcomed to the court of the Delhi Sultan; and whether the preface is the ‘Bāysunghurī’ text or an earlier version.Footnote 14 It is interesting to note that the preface of our manuscript is the earlier Abū Manṣūrī version;Footnote 15 the same preface as the Mohl Shāhnāma, of possible Indian origin. However, this does not necessarily confirm an Indian provenance for these manuscripts as there are other examples produced in Iran that post-date Bāysunghur that still use the older version.Footnote 16

There are two distinct types of illumination employed in the Shāhnāma. The title panels (ʿunwāns)Footnote 17 resemble the blue-and-gold floral style that evolved in Shiraz in the latter half of the fourteenth century and continued until at least the mid-fifteenth century.Footnote 18 The style was exported to Ottoman and Mamluk territories and to Yemen and India.Footnote 19 Titles are in gold outlined in black against a background of delicate scrolling arabesques within a cusped-edged cartouche. The area around the cartouche is painted blue with gold sprigs of leaves dotted with small white and red flowers.Footnote 20

The illuminated double-page (fol. 1v–2r, Figure 1)Footnote 21 marks the opening to the preface in the first volume and is illuminated in the colourful palmette-arabesque style that appeared in the early 1430s, but is found more consistently in the decade after Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān's death (1435–36/1444–45).Footnote 22 The upper and lower panels contain gold kufic inscriptions against scrolls of robust white arabesques against a blue background. The panels to the left and right contain lobed cartouches, filled with geometric designs of palmette-arabesques; the central cartouche features split-palmettes in a distinctive vibrant orange-red, set against a blue background. These colour combinations, along with areas of gold on black, are characteristics of this new style.Footnote 23

Figure 1a and b. Illuminated double page, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fols. 1v–2r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

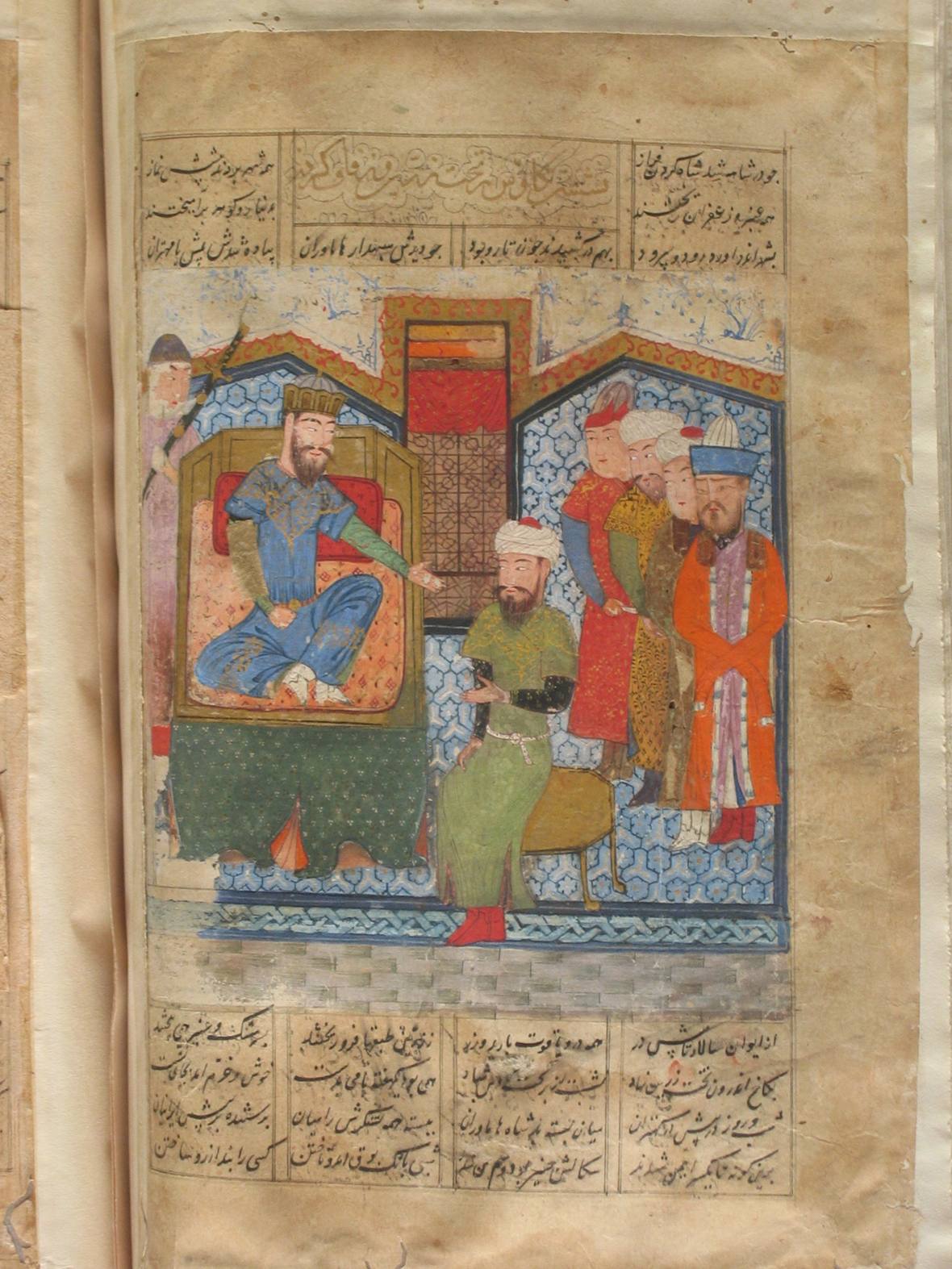

There are 48 illustrations: 32 in the first volume and 16 in the second.Footnote 24 The illustrations usually occupy half or two-thirds of the text panel. The action of each scene takes place in the foreground, and context is provided by the interior of a palace with a set formula of a tiled dado punctuated by a narrow window (Figure 2), or by a simple landscape setting with a high horizon (Figure 3).Footnote 25 Large tear-shaped seal impressions, stamped in the margins, occur on 46 folios scattered throughout the two volumes (Figure 4).Footnote 26 This seal impression bears the full name of Sulṭān Muḥammad Shāh, ruler of the State of Gujarat from 846/1442 until 855/1451, including Ghiyāth al-Dīn, the title he took when he ascended the throne,Footnote 27 which tallies with existing coins inscribed with his titles.Footnote 28

Figure 2. ‘The King of Hamavaran Pretends to Serve Ka'us’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 78v. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

Figure 3. ‘Salm Flees and Is Killed by Manuchihr’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 32r. © Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna.

Figure 4. Seal, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 436r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

The Shiraz connection: manuscripts and artists travelling east to India

A brief historical introduction to the Shiraz connection with Gujarat

Efficient trading networks had operated in the Indian Ocean littoral for centuries.Footnote 29 A close connection between Gujarat and cities in Persia was established through trade long before the Delhi Sultan ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Khaljī conquered part of Gujarat in 1297. When Gujarat became independent in 1407, Muslim traders and religious figures continued to settle in the region.

Many regions in Iran had trade and diplomatic links with the Sultanate states of fifteenth-century India, including direct communication between the Timurid royal family in Iran and certain rulers of the Indian Sultanates.Footnote 30 However, it is commonly understood that Shiraz was one of the key regions to export artists and manuscripts to South Asia.Footnote 31 There are two main factors as to why this was the case: first, Shiraz appears to have had a long history of ‘commercial’ production, beginning in the early Injuid period in circa 1330 and continuing at least into the sixteenth century;Footnote 32 secondly, there was ongoing travel and migration between these regions due to the movement of intellectuals, merchants, Sufis, and pilgrims. When the region became more stable after the establishment of the Gujarat Sultanate in the early fifteenth century, forts, city walls, and even entire towns were constructed. Extensive provision was made for merchants and others to settle in the region.Footnote 33 As Samira Sheikh points out, migration and mobility were the norm in Gujarat for all those engaged in trade, pilgrimage, and politics, from at least the twelfth century to the end of the fifteenth.Footnote 34

The network of well-worn routes used by traders, religious figures, and diplomats facilitated the movement of scribes and craftsmen trained in all aspects of the arts of the book, including artists. They migrated to India and augmented the artistic communities already in existence there. Aḥmad Shāh, a ruler of Gujarat (813–846/1411–42), had his reign chronicled by the poet Ḥūlwī Shīrāzī, who records that the ruler Aḥmad himself was a fine poet and wrote in Persian verse.Footnote 35 Another migrant from Shiraz to the Gujarati court wrote the Taqvīm dar Nujūm in 844/1441, which he dedicated to Aḥmad Shāh.Footnote 36 In the preface, the anonymous author of this text explains that he was from Shiraz and had wanted to go to India for some time, but ‘bad luck’ and fear of the sea had prevented him until then.

The Patna Shāhnāma and Timurid manuscripts from Shiraz

Visual evidence of the movement of Persian manuscripts, scribes, and artists from Shiraz to Sultanate India during the fifteenth century and earlier can be tracked relatively easily in some instances; for example, several manuscripts that were produced in the court of Mandu in the 1490s, such as the Ni‘matnāma and Miftāh al- Fuẓalā, reference Turkman manuscripts.Footnote 37 The presence of Shirazi traits are not just detected in Sultanate manuscripts with Persian texts but also, albeit more tentatively, in Jain painting; their distinctive solid red background relates to Injuid manuscripts.Footnote 38 Another example is an early fifteenth-century Qur'an known to have been in the library of Maḥmūd Shāh (r.1459–1511), Sultan of Gujarat, from a seal impression dated 893/1488;Footnote 39 the illumination can be related to fourteenth-century Shirazi Qur'ans, although it was most likely produced in Gujarat.Footnote 40

All aspects of the Patna Shāhnāma, including the page layout, calligraphy, illumination, and illustrations, resemble manuscripts produced in the late 1430s and 1440s in the region of Shiraz. There are 22 known illustrated copies of the Shāhnāma produced in or associated with the Shiraz orbit between 1435 and 1450, including those of possible Sultanate origin.Footnote 41 Of this broader group, the Patna manuscript is particularly close to those Shāhnāmas produced outside the royal court that show a clear debt to an illustrated Shāhnāma of circa 1430, commissioned by Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān, Timurid governor of Shiraz from 1414 (Bodleian Library, Oxford, Ouseley Add. 176).Footnote 42 These Shāhnāmas have been described as ‘post-Ibrāhīm’ as they were produced after his death in 1435.Footnote 43

The Patna Shāhnāma has many features in common with the Bodleian manuscript.Footnote 44 First, the Bodleian Shāhnāma of Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān also contains illumination in two distinct styles. A densely illuminated Qur'an, attributed to Gujarat from around 1430–50, also combines styles from both Timurid Herat and Shiraz, along with features of local Bihari Qur'ans.Footnote 45 Many post-Ibrāhīm manuscripts can be divided roughly between those that follow the Shiraz blue-and-gold theme and those that consist of elements more recently derived from Herat illumination.

Of the 48 illustrations in the Patna manuscript, only seven illustrate the same episodes as those in the Bodleian Shāhnāma. Both manuscripts include ‘Rustam Lifts Afrasiyab from His Saddle by His Belt’ with similar compositions: a high horizon, although that in the Patna rises to point, while that in the Bodleian describes a gentle curve;Footnote 46 figures are relatively large; and the barren landscape, scattered with small, neatly placed tufts of grass (Figure 5). In the Patna scene, Rustam has a more muscular and dynamic appearance than his Bodleian counterpart.

Figure 5. ‘Rustam Lifts Afrasiyab from His Saddle by His Belt’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 65r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

Many of the folios in the Bodleian Shāhnāma have stepped text panels, a distinctive feature of Shirazi manuscripts also found in our Patna Shāhnāma. In an analysis of the layout of the folio in Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān Shāhnāma, Elaine Wright observes the frequent use of stepped text-blocks results in more effective integration of text and image, often serving both a textual and compositional function.Footnote 47

Twenty-nine illustrations in the Patna manuscript have a stepped edge while the rest have straight-edges, often with a detached verse as part of the painting.Footnote 48 Most have a shallow step, two lines deep, with one or two verses spread over two columns. The folio depicting ‘Rustam Pulls the Khāqān of Chin from His Elephant’ is the only one that features a deep step, only one column in width, with three verses (fol. 185r; Figure 6). It is the most eye-catching page layout, with perhaps the most inventive illustrated page for its interplay of text and image. The three verses in the stepped area of this folio, or break-line verses, describe Rustam throwing his lasso around the Khāqān of Chin's neck; thus, the artist has followed the text closely.Footnote 49 At the base of the painting is a further verse describing the Khāqān dragged off his elephant, so the reader does not have to turn the page to find out what happens next. This carefully considered page layout is further emphasised by the artist who has arranged the composition so that the elephant's feet appear to be trampling on the text where he is mentioned.

Figure 6. ‘Rustam Pulls the Khāqān of Chin from His Elephant’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 185r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

Other features of the Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān Shāhnāma and the Patna manuscript have commonalities: aspects of the iconography and compositions of the illustrations, the layout of the page, and the interplay between text and image. However, the Patna artist drew on the Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān legacy without directly referring to this manuscript. The Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān Shāhnāma, being part of the royal collection, would have had a limited audience. However, after Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān's death, the court artists dispersed, and there was a rapid increase in the number of high-quality commercial manuscripts produced in Shiraz and a move away from court patronage.Footnote 50 The Patna manuscript can be associated more directly with this group of Shiraz manuscripts of the late 1430s and 1440s.

One such example is a copy of the Shāhnāma dated 839–41 (1436–37), previously owned by the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava.Footnote 51 Robinson determined that three artists worked on this manuscript, one of whom most likely came from the royal atelier, and that the manuscript was begun before Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān died and then completed elsewhere, possibly even India.Footnote 52 Although the compositions in these two copies of the Shāhnāma are not identical, they share a relatively high number of similar subjects, and there are common traits in both iconography and composition. The Dufferin and Ava Shāhnāma has the same page layout as the Patna manuscript, and most of the post-Ibrahim Shāhnāmas, with 25 lines to the page divided into four columns.Footnote 53 The page layout shows an integrated arrangement of image and text, as noted above in the Patna folios, but with more imaginative use of the margins.

Another manuscript that closely compares with our Patna Shāhnāma is a copy of this text in Leiden University Library dating to 1437 (840).Footnote 54 The sizing and page layouts are close,Footnote 55 and the illustrations have common aspects in composition and details. Take the illustration of ‘Rustam and the White Div’ (Figure 7); the artist of the Leiden version of this scene uses a similar formula for the composition, allowing some variation in the landscape details. The Leiden miniature lacks the frothy rocks of the Patna version and instead has a landscape covered in red flowering plants.Footnote 56 Ulad and Rakhsh are placed in the margin in the Leiden version. For popular images such as this, the basic formula was repeated in many post-Ibrāhīm manuscripts and probably originated with the Bodleian version.Footnote 57

Figure 7. ‘Rustam Slays the White Div’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 74r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

Still further Shāhnāmas, of similar and later date, contain parallel iconographical details and compositions, such as a Shāhnāma of 1441, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.Footnote 58 However, the closest comparison with our Patna Shāhnāma is an illustrated copy of this text in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, with some loose folios in the British Museum in London, which is undated but probably produced in the late 1430s.Footnote 59 In the illustration of ‘Salm Flees and Is Killed by Manūchihr’ (Figure 3), the two leading figures in the battle strike a similar pose as those in the same scene in the British Museum illustration, including the more unusual position of having Manūchihr's horse in front of Salm's (Figure 8).Footnote 60 The rendering of the horses themselves is also alike. Improvisation was confined to secondary features such as lesser figures, the landscape, and decorative details.

Figure 8. ‘Manuchihr Kills Salm’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, circa 1438–89. Source: British Museum, 1948.10-09.049 © Trustees of the British Museum.

Another painting in the Cambridge manuscript of ‘Rustam Lifts Afrasiyab from His Saddle by His Belt’ (fol. 22v; Figure 9) is virtually identical to the same subject illustrated in the Patna manuscript (fol. 65r; Figure 3), discussed above. Most figures in the Patna version of this episode are replicas of those in the Cambridge painting. Rustam thrusts his arm up in the same manner with his left arm held away from his body. The few differences between these two paintings are the extraneous details. The paintings look similar at first glance, and on closer inspection, the measurement from the top of Afrasiyab's helmet to the edge of the caparison over Rustam's horse is identical in both scenes.Footnote 61 Therefore, it seems clear that the striking similarity is the result of the Patna artist making a copy of either the Cambridge illustration itself or an identical model.

Figure 9. ‘Rustam Lifts Afrasiyab from His Saddle by His Belt’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, circa 1438–39. Source: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS 22-1948, fol. 22v © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

A note on the repetition of images

It is notable that although these ‘post- Ibrāhīm’ manuscripts contain many repetitions in their illustrations,Footnote 62 each manuscript displays original compositions and choices of subject.Footnote 63 Indeed, the Patna illustrations have a fresh and vigorous look. In an analysis of a group of royal manuscripts produced in Herat in the fifteenth century, Adamova concludes that the artists were following set rules for repetition and invention to demonstrate proficiency at reproducing well-known compositions and an ability to invent new interpretations of the text.Footnote 64 In studies of non-courtly Shiraz manuscripts, it has been suggested that repetition was due to the need for swift production.Footnote 65 However, those responsible for planning Shiraz Shāhnāmas for the market were also following an established protocol of repetition and invention. The Shiraz illustrations correspond on many levels, ranging from copying a group of figures to repeating the majority of the composition. Nevertheless, each manuscript included only a small number of copies of earlier compositions, with the remainder of the paintings being original compositions; therefore, the planning of each illustrative cycle was not entirely dissimilar to courtly manuscripts.Footnote 66

Within the post- Ibrāhīm group of manuscripts, the source for copied compositions is frequently the Cambridge Shāhnāma. This manuscript served as a type of copybook, or perhaps copies or pounces of certain paintings were circulated.Footnote 67 However, just one painting within the Patna Shāhnāma is modelled on an illustration in the Cambridge Shāhnāma, and only seven of its 48 paintings illustrate scenes also included in the Cambridge manuscript. It is surprising that copying was not more frequent in making commercial manuscripts, as this would have reduced production times. Perhaps manuscripts containing a combination of recognisable scenes and new compositions were more valued and therefore easier to sell.Footnote 68 It is quite likely that soon after its production in Shiraz, the Cambridge Shāhnāma was taken to India, where it was acquired much later by Percival Chater Manuk, a high court judge in Patna and a pioneer collector of Indian painting.Footnote 69

The artists working on this particular group of manuscripts were not necessarily all from the same workshop. Indeed, the Patna manuscript was probably not produced in the same city or even country. However, artists trained in the Shirazi style usually included both copied and original illustrations in their manuscripts. Extensive research by Sims and Wright has shown that the manuscripts associated with Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān and their antecedents have significant historical value, even if their aesthetic value is not of the same calibre as contemporary Herat painting.Footnote 70 Sims also points out that the importance of post-Ibrāhīm Shirazi manuscripts lies in the fact that their style was to have an impact from India to Turkey.Footnote 71 The burgeoning number of manuscripts has been attributed to the death of Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān, when artists left the royal atelier to seek employment elsewhere.Footnote 72 I would extend this argument to suggest that the potential market in the Indian Sultanates was a contributory factor in the high number of manuscripts produced at this time.Footnote 73 Alongside the market for manuscripts in India there was a demand for artists and calligraphers to relocate and work for local patrons.

Manuscripts are portable objects and might be collected, gifted, and read far from their original place of production. It is vital to consider the future life of each manuscript ‘post-production’ in the context of Sultanate India, rather than focus entirely on its place of origin. A considerable number of manuscripts with Persian texts from the Shiraz orbit, now in private and public collections worldwide, were collected in India (see Appendix C).Footnote 74 In order to fully understand the art of the book in the Indian Sultanates, we need to consider where and how manuscripts were collected and commissioned across the South Asian Sultanate states. While this article is largely intended to provide evidence of a Shiraz-style manuscript's India provenance, this research also reflects on the production and movement of a particular group of Shāhnāma manuscripts produced in post-Ibrahim Shiraz, and others besides.

Evidence for the Indian origin of the Patna Shāhnāma

Two striking elements point to an Indian provenance for the Patna Shāhnāma, despite its Shiraz connections. First, the number and form of the elephants depicted. In the Patna manuscript, there are three depictions of elephants: ‘Rustam Lassoes Kāmūs’ (fol. 177r; Figure 10), ‘Rustam Pulls the Khāqān of Chin from His Elephant’ (fol. 185r; Figure 6), and ‘Hormuz Giving Bahrām Chūbīna Command of the Army’ (fol. 489v). The episode where Kāmūs is pulled from his horse by Rustam was an unusual choice for fifteenth-century Shāhnāmas.Footnote 75 The Patna scene shows Kāmūs riding an elephant rather than the horse referred to in the text. The Mohl Shāhnāma is the only other Shāhnāma from the first half of the fifteenth century to feature this scene, and here Kāmūs is also riding on an elephant who has a similar stance, with one of the forelegs stretched forward and the other bent back at the knee.Footnote 76 Along with some other observations, it was the gait of this particular elephant that Barbara Brend noted as one argument for an Indian origin of this manuscript.Footnote 77

Figure 10. ‘Rustam Lassoes Kamus’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 177r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

The form of the three white elephants in the Patna paintings is unlike those shown in Persian painting and is instead more realistically depicted with a domed forehead. Contemporary Shirazi versions, on the other hand, usually feature large frilly edged ears, bulbous feet, and decorative adornments; for example, the elephant in the Leiden Shāhnāma of 1437, mentioned above.Footnote 78 In short, none of the post-Ibrāhīm paintings of elephants resemble the more realistically depicted Patna Shāhnāma elephant.

By contrast, the form of elephant found in the Patna illustrations, with a domed forehead, small ears, and foreleg bent at the knee, is found in Indian painting from the fourteenth century onwards. A Jain yantra (sacred diagram), painted on cloth in Gujarat in 1447, has an elephant with a comparable outline to the elephants in the Patna illustrations, even though the skin is painted or covered with ornaments in the Gujarat version.Footnote 79 Painted at the same time as the Shāhnāma, in the nearby state of Mandu, the Kalpasūtra of 1439 contains elephants whose heads have a similar profile, with a high-domed forehead.Footnote 80 The same type of elephant also appears in the Sultanate copy of the Ḥamzanāma.Footnote 81 Like the Mandu Kalpasūtra, the elephant in the Ḥamzanāma also wears rings around its ankles and has a painted trunk. This form can be seen later in Mughal paintingsFootnote 82 and even in Kashmir paintings four centuries later.Footnote 83

The second visual element that suggests an Indian connection are the textiles depicted in many of the illustrations in the Patna manuscript. The variety of patterns on clothes, armour, and the interiors is a notable feature of the Patna illustrations not found in contemporary Shirazi painting. Caparisons on certain horses in the Patna Shāhnāma feature designs ranging from simple lines to rows of scrolls or diamond shapes (Figures 7, 10–12). In contrast, horses depicted in both the Bodleian and Cambridge Shāhnāmas, for example, have caparisons of similar form, sometimes in monochrome colours, or they feature lines and strokes to represent the joins and seams of the horse covering.Footnote 84

Some of these designs in the Patna illustrations find echoes in contemporary Gujarat textile designs. Gujarat has a block-printing textile industry that dates back to at least the eleventh century and is still well-known today. Under the independent sultans of the fifteenth century, the industry was thriving, and exports grew considerably.Footnote 85 The caparison on the three horses in the foreground of fol. 32r (Figure 3) and the horse on the left of fol. 135v (Figure 11) feature alternate rows of vine scrolls and finials. Suhrāb's horse on the right of the illustration on fol. 88r (Figure 12) also features scrolls and finials in a distinctive colour scheme of orange against a yellow background. This design resembles fragments of contemporary cloth from Gujarat that survive in the Newbury Collection in Oxford (Figure 13).Footnote 86 Another block-print design found on Garshāsp's horse on fol. 30r, composed of repeated diamond shapes in friezes alternating with finials, can also be paralleled with a Gujarati textile design.Footnote 87

Figure 11. ‘Giv, Son of Gudarz, Finds Kay Khusrau’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 135v. © Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna.

Figure 12. ‘Sūhrab in Combat with Gurdāfarīd’, Shāhnāma of Firdausī, dated 843/1440. Source: Khuda Bakhsh Library, Patna, no. 3787, fol. 88r. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

Figure 13. Blue and white textile, block-printed resist, dyed blue, fifteenth century, made in Gujarat. Source: Ashmolean Museum, Newberry Collection, EA 1990.131, © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

A further factor indicating an Indian origin is the thin brown paper, a type usually associated with India and also used for the suspected Sultanate Mohl Shāhnāma. A proper scientific study of paper used in fifteenth-century manuscripts has not yet been carried out; this study, preferably in collaboration with conservators, would help clarify the similarities and differences between paper made in Iran and South Asia.

All the elements that constitute the Patna manuscript derive from the Shiraz orbit of the 1430s and 1440s: illumination, page layout, calligraphy, and illustrations. However, the well-defined elephants and the links to Gujarat textiles strongly suggest an India link. The Patna manuscript must have resulted from the arrival of an artist from the Shiraz region migrating to India seeking patronage after the royal atelier had disbanded following Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān's death. The few Indian elements in the Patna manuscript probably resulted from the impact of an Indian environment on an artist who was otherwise trained in the Shiraz mode. Alternatively, he was working in tandem with an artist familiar with local traditions.

The main criteria used by Robinson, Fraad, and Ettinghausen to assert the Indian provenance of the group of Persian manuscripts mentioned above were the presence of unusual characteristics in the illustrations that seemed out of line with contemporary Persian painting.Footnote 88 However, unusual characteristics alone cannot prove an Indian origin. Furthermore, being entirely in line with contemporary Shiraz painting does not exclude the possibility of an Indian provenance; as we have seen, the Patna Shāhnāma does fit with contemporary manuscripts from Shiraz. Access to literature and artists from Iranian cities was not confined to the years of the Delhi Sultanate but continued into the fifteenth century in regional centres.

Persianate culture in the Indian Sultanates, and the reception of the Shāhnāma

During the fourteenth century, the political frontiers within India were in constant flux with new urban centres established; these new settlements facilitated the spread of Persianate culture through the circulation of Persian texts.Footnote 89 There was an increased interest in Persian literature among the elite across South Asia, particularly during the reign of the Tughluqs.Footnote 90 Muḥammad ibn Tughluq (r.725–752/1325–51) was famed for his knowledge of Persian literary works and was keen on the Shāhnāma.Footnote 91 The upsurge in lexicography at this time indicates that Persian classics were popular. Dictionaries were needed to explain obsolete or unfamiliar words and expressions used in classical literature. The Farhang-i Qawwās was the earliest Persian dictionary produced in India and was compiled by Fakhr al-Dīn Mubārak Shāh, who stated that the Shāhnāma is the zenith of all literary achievements.Footnote 92

The focus of this study is the Shāhnāma. However, there were, of course, numerous other popular texts from many genres and other literary texts in circulation, such as the the Ḥamzanāma Footnote 93 and the Khamsa of Niẓāmī, seen above, and the Būstān of Sa'dī.Footnote 94 Of the many Persian works written in India, well-known illustrated manuscripts include Amīr Khusrau's Khamsa, composed between 1298 and 1302,Footnote 95 and the Ni‘matnāma, mentioned above, written in Mandu in the late 1490s, for Sultan Ghiyāth al-Dīn and completed in the reign of his son Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh (r. 1500–1510).Footnote 96

The earliest surviving Shāhnāmas produced in India, aside from the Patna Shāhnāma under discussion, are two illustrated copies dating to circa 1450–75.Footnote 97 The Indian origin of these two manuscripts is apparent due to their close correlation with Indic material culture. The first of these manuscripts survives as only six Shāhnāma paintings, which are removed from their text and now reside in the Bharat Kala Bhavan Museum in Varanasi (Figure 14).Footnote 98 The other is a dispersed copy, often called the ‘Jainesque Shāhnāma’, as the paintings were executed by an artist trained in the Jain tradition.Footnote 99 The Varanasi Shāhnāma forms part of a small group of nearly identical manuscripts; the others in the set being copies of the Khamsa of Niẓāmī.Footnote 100 The paintings accompanying these texts have a consistent and unique style with elements related to both Indic and early fourteenth-century Persian illustrative traditions.

Figure 14. Shāhnāma of Firdausī, circa 1450–75. Source: Bharat Kala Bhavan, Varanasi, 9943. Photo: Emily Shovelton.

The Varanasi paintings and the Jainesque Shāhnāma illustrations have no obvious visual connections with our Patna manuscript and instead demonstrate how Persianate literary works in South Asia were absorbed and reinterpreted through Indic visual culture. The prevalence of Persianate literary and visual arts had been well established during the centuries of Delhi Sultanate rule. However, under the Sultanate states of the fifteenth century, material culture reflects diverse ‘local’ traditions rather than a more unified vision emanating from one dominant central court. A case in point is the appearance of the Sufi romances, or so-called prema-kahānī, between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries.Footnote 101 These embody the transcultural environment at this time as the stories are based on the Persian genre of Sufi poetry but adopt local folk stories and Hindu mythology and deities. One such text was the Chandāyan, a vernacular romance composed by the Chishti Sufi Maulānā Dā’ūd in 1379 in Avadhī, a local eastern dialect of Hindavī text, and written in the Arabic script. Several copies were produced with illustrations in various styles that reflect this cross-cultural dialogue.Footnote 102

These two copies of the Shāhnāma further testify to the fluidity of cultural traditions; both show how a Persian text was remade in India with illustrations that reflect overlapping local and ‘foreign’ elements.Footnote 103 The boundaries between different cultural traditions were not clear-cut, and iconography and ideas flowed in multiple directions. Consider the Kālakācārya-kathā, probably made in Mandu in circa 1430–40, now in the Lalbahi Dalpatbhai Institute, Ahmadabad.Footnote 104 This manuscript was the product of a thriving and wealthy Jain community. Nevertheless, certain elements from Persian and Arabic illustrated literature were assimilated into these Jain paintings. The variety of illustrative interpretations of the Shāhnāmas produced in South Asia show that different illustrative traditions were not bound to a single language or text, and diverse audiences across the subcontinent appreciated the text.

The Patna Shāhnāma and Indo-Persian culture in the Sultanate state of Gujarat

The Bahmani dynasty in the Deccan was the first Sultanate state to declare independence in 1347.Footnote 105 Following the sack of Delhi in 1398 by Timur, other provincial governors took advantage of the absent Sultan, seized control, and established their independence.Footnote 106 The governor of Gujarat, Ẓafār Khān, declared Gujarat to be a sovereign state in 1407 and entitled himself Muẓaffar Shāh (r. 1407–11).Footnote 107 Interestingly, this seemed to have been Timur's tactic. Digby surmises that there were two main aims behind Timur's campaign in India: first, to wipe out central authority and thereby reduce the threat from the East to Timur's realm; and, secondly, to establish subsidiary alliances with less powerful chieftains and governors across the country.Footnote 108

The seal impressions found on multiple folios in our Patna Shāhnāma bear the name of Muḥammad Shah, ruler of Gujarat from 1442–51. Other than describing him as a pleasure-loving ruler who preferred courtly life to the battlefield, sources do not provide much detail on his life and character.Footnote 109 His father, Sultan Aḥmad Shāh (813–846/1411–42), founded a new capital city Ahmadabad, which soon attracted merchants, poets, Sufi sheikhs, and scholars from all over India, as well as from Persia, Egypt, and beyond.Footnote 110 Aḥmad Shāh and future rulers and the elite in Gujarat patronised literature in Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrit.Footnote 111

Muḥammad Shāh grew up in this environment and courtly life for him would have encompassed diverse literary and religious traditions;Footnote 112 a Brahman writer mentions that he visited Muḥammad Shāh's court in Ahmadabad and impressed all the scholars there.Footnote 113 Rather than marry into the family of a Sultanate ruler or noble, he was the first Sultan from Gujarat to marry the daughter of a local chieftain, Rā’i Har of Idar. She was known as a great beauty who charmed the Sultan into restoring the fort of Idar to her father.Footnote 114 Although there had been Persian-speaking communities in Gujarat for centuries by then, the use and spread of the language was more significant under the independent Sultanate state. Take epigraphic inscriptions; in the early fourteenth century, long Sanskrit inscriptions would be followed by short rudimentary texts in Persian. This changed during the fifteenth century when most combine Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrit,Footnote 115 with the Persian section usually being the most lengthy.Footnote 116

We cannot know for sure what it was about the Shāhnāma that interested Muḥammad Shāh. However, presumably the story resonated for any ruler trying to establish or maintain sovereignty in Sultanate India, where Persian was the language of politics and elite culture. In Gujarat, with such close links to Iran, the epic tales of past rulers must have had particular relevance. Muḥammad Shāh, a ‘pleasure-loving’ ruler interested in courtly culture, most likely enjoyed the entertaining stories and appreciated them from a literary perspective as a mirror for princes. The Patna Shāhnāma is dated 843/1440,Footnote 117 and Muḥammad Shāh came to the throne in 1442; therefore, the seal impressions were added two years, if not more, after the manuscript was completed.

Conclusion

This brief examination of the Patna Shāhnāma and its historical context establishes a close connection between the production of illustrated manuscripts in the Iranian world and South Asia, perhaps earlier than is often assumed. The manuscript differs from other near-contemporary Shāhnāmas produced in South Asia. Instead, it echoes Shirazi styles, thus demonstrating that many different modes were assimilated into painting practices in fifteenth-century India, both from prior and contemporary traditions. Previous art historical discussions of codicology and painting styles often assume that the arts of the book in India at this time tend to display only ‘outmoded’ rather than ‘current’ traits. This viewpoint needs to be reconsidered. Moreover, the term ‘outmoded’ when applied to South Asian manuscripts is redundant as the Persian model was not always the prime initiator for painting in India. Any so-called outmoded trait in South Asia painting has been selectively absorbed and transformed into a current trend in its new context.

Considering the Patna Shāhnāma in an Indian courtly context also demonstrates that the development and consumption of intellectual and artistic pursuits in the complex transcultural world of the Indian Sultanates cannot be explained through the dichotomy of provincial versus courtly. Muḥammad Shāh's ownership of this Shāhnāma demonstrates that ‘provincial’ styles were enjoyed in the court. The dialogue often employed by historians of centre and periphery cannot be applied to the Indian Sultanates;Footnote 118 lines usually drawn between courtly and provincial material culture were blurred during the fifteenth century when multiple provincial courts ruled South Asia.

The Patna Shāhnāma was most likely made in India by an itinerant Shirazi artist. Alongside craftsmen, manuscripts themselves were likely to have travelled to India at this time. The Patna Shāhnāma dates to the most prolific decade in the first half of the fifteenth century for the production of Shiraz manuscripts (838–48/1435–45), after the death of Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān. It has been suggested that these manuscripts were made in Shiraz for the open market and possibly for export. This could be regarded as a resurgence of commercial production that began in Shiraz during the Injuid period of the 1330s and continued to grow under the Turkmans in the second half of the fifteenth century when Shiraz became a major centre of this kind of activity.Footnote 119

In a Sultanate context, manuscripts’ use and earliest owners can be as significant as the exact place of production. The impetus behind the high level of production in the 1430s to 1440s in Shiraz was likely due not only to the death of Ibrāhīm-Sulṭān but also to the hospitable environment of South Asia. The immigration of artists, and the export of manuscripts, to India from many different regions in the Iranian world would continue later in the century to Malwa, Bengal, and the Deccan. A similar and much better-known influx occurred under the Mughals from the second half of the sixteenth century onwards.

The independent state of Gujarat was founded in 1391 and consolidated during Aḥmad Shāh's reign. By the 1440s, Gujarat and neighbouring Malwa and other states were now fully established and had both the economic resources to encourage an active cultural life and a need to promote themselves. Patronage of Persian literature, and collecting works, was expected of any Indo-Persian ruler. Adding this copy of the Shāhnāma to the corpus of fifteenth-century material sheds new light on the relationship between Iranian and South Asian production and patronage of Persian manuscripts and leads to a more nuanced understanding of patterns of production in Iran and their reception in South Asia.

Appendix A: Shāhnāma of Firdausī, Khuda Bhaskh Library, Patna, 3787 and 3788

48 miniatures

Volume I (3787)

1) fol. 10v: ‘Praise of Sultan Mahmud’

2) fol. 20r: ‘Faridun defeats Zahhak’

3) fol. 30r: ‘Combat between Shiruy and Garshasb’

4) fol. 32r: ‘Manuchihr kills Salm’

5) fol. 38b: ‘Rudaba's companions contrive to see Zal’

6) fol. 44a: ‘Sam before Manuchihr’

7) fol. 48r: ‘Zal visits Manuchihr’

8) fol. 57r: ‘Combat between Barman and Qubad’

9) fol. 65r: ‘Rustam lifts Afrasiyab from his saddle by his belt’

10) fol. 67v: ‘Kay Ka'us listens to singer extolling Mazandaran’

11) fol. 74r: ‘Rustam slays the White Div’

12) fol. 78v: ‘The king of Hamavaran pretends to serve Ka'us’

13) fol. 84r: ‘Battle between Pilsam and the army of Iran: Pilsam flees on hearing of Rustam's arrival on the battlefield’

14) fol. 88r: ‘Suhrab in combat with Gurdafarid’

15) fol. 93v: ‘The first battle between Rustam and Suhrab’

16) fol. 96r: ‘Rustam wounds Suhrab and discovers his identity’

17) fol. 97v: ‘Rustam mourns Suhrab’

18) fol. 106v: ‘Afrasiyab relates his dream to Garsiwaz’

19) fol. 115v: ‘Siyawush meets Farangis’

20) fol. 125r: ‘Murder of Siyawush’

21) fol. 128r: ‘Piran takes Kay Khusraw to Afrasiyab’

22) fol. 135v: ‘Giv, son of Gudarz, finds Kay Khusrau’

23) fol. 142v: ‘Kay Khusrau enthroned’

24) fol. 157v: ‘Battle between the Iranians and Turanians’

25) fol. 177r: ‘Rustam lassoes Kamus’

26) fol. 185r: ‘Rustam pulls the Khaqan of Chin from his elephant’

27) fol. 196r: ‘Rustam kills the Demon Akhwan’

28) fol. 200r: ‘Bizhan comes to Manizha's tent’

29) fol. 212v: ‘Rustam and Bīzhan before Kay Khusrau’

30) fol. 222r: ‘Bizhan kills Human’

31) fol. 235r: ‘Piran is slain by Gudarz’

32) fol. 267r: ‘Capture and execution of Afrasiyab and his brother Garsiwaz’

Volume II (3788)

1) fol. 282v: ‘Gushtasp and the dragon’

2) fol. 321v: ‘The battle between Rustam and Isfandiyar’

3) fol. 325v: ‘Rustam shoots Isfandiyar in the eyes with a forked arrow’

4) fol. 340v: ‘Death of Rustam’

5) fol. 367v: ‘Ilyas and Khidr at the well of life’

6) fol. 372b: ‘Iskandar dies and his coffin is carried to Iskandariya’

7) fol. 393r: ‘Shapur and Taʾir's daughter preside over Taʾir's execution’

8) fol. 396r: ‘Capture of Caesar’

9) fol. 402r: ‘Bahram Gur's mount tramples Azada’

10) fol. 403r: ‘Yazdagird killed by a white demon horse’

11) fol. 414r: ‘Bahram Gur kills the dragon which had devoured a youth’

12) fol. 435r: ‘Accession of Qubad’

13) fol. 489v: ‘Hormuz giving Bahram Chubina command of the army’

14) fol. 493v: ‘Bahram Chubina kills the fleeing Sava Shah’

15) fol. 498v: ‘Bahram Chubina is sent woman's clothes by Hurmuzd’

16) fol. 538v: ‘Khusrau Parviz visits Shirin in her castle’

Appendix B: Shāhnāmas from the Shiraz orbit, circa 1430–50

1) 831/1427–28, National Museum, New Delhi, no. 54.60. 89 illustrations

2) circa 1430–35, Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Ouseley Add. 176. 42 illustrations

3) circa 1435, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS 22-1948 (25 illustrations) and London, British Museum, 1948.10-09.48-52. 5 illustrations

4) circa 1430–40, John Rylands Library, Manchester, Pers.MS933. 100 illustrations, only 4 contemporary

5) 839–841/1436–37, Current whereabouts unknown. Ex-collections: Sidney Churchill; the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava; the Aga Khan. 58 illustrations

6) 841/1438, British Library, London, Or.1403 (ex-Collection Jules Mohl). 93 illustrations

7) 844/1441, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Supplément persan.493. 52 illustrations

8) 844/1441, Dār al-Kutub, Cairo, MS59. 15 illustrations

9) 845/1441, The Art and History Trust, currently on loan to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington DC (the ‘Soudavar’ Shahnama), MS Cat.27. 24 illustrations

10) circa 1440–50, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, S86.0177, 0148-49, 0151. 5+ illustrations

11) circa 1440–50, Staaliches Museum fur Volkerkunde, Munich (ex-Preetorius Collection, 77-11-281, and Nasser D. Khalili Collection, MSS845. 2 illustrations

12) 847/1443, Tehran, Gulistan Palace Library, Ms.2173 (formerly Ms.475). 14 illustrations

13) 848/1444, Current whereabouts unknown Ex-Kevorkian XXV (Sotheby's, London, 12/6/67, lot 189). 14 illustrations

14) 848/1444, Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris, Supplément persan.494 (and Cleveland, 45.169 and 56.10). 21 illustrations

15) 849/1445, St. Petersburg, Oriental Institute, Academy of Sciences, C1654, 29 illustrations

16) 853/1449, Riza Abbasi Museum, Tehran, Ms.1971. 18 illustrations

17) circa 1450, St. Petersburg, Archives of Academy of Sciences, C.52, 31 illustrations

18) circa 1450, John Rylands Library, Manchester, Pers.MS9. 42 illustrations

19) 855/1451, British Library, London, Or.12688 (ex-Collection Erskine of Torrie, the ‘Dunimarle’ Shahnama,). 80 illustrations

20) 855/1451, Turk ve Islam Eserleri Muzesi, Istanbul, no. 1945. 63 illustrations

21) circa 1450–60, Current whereabouts unknown (ex-Sohrab Hakim Collection, Bombay), 103 illustrations

22) late 1420s to early 1430s, Dispersed, 3 folios in the Smithsonian Institute, Washington DC, S.1986.144-46

Appendix C: Shāhnāmas produced in Iran, circa 1430–50, previously or currently in Indian collections

Shāhnāmas now accepted as of Sultanate origin

Shāhnāmas of Sultanate origin