The major disruptor of normative development is antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence (Dishion & Patterson, Reference Dishion, Patterson, Cicchetti and Cohen2006). The vast majority of children seen in mental health clinics are those presenting with some form of problem behavior, ranging from oppositional defiance in childhood to delinquent behavior and drug use in adolescence. Adolescent problem behavior is often embedded in their involvement in their peer groups (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, Reference Dishion, McCord and Poulin1999). Research over the past 60 years has indicated a strong association between children's antisocial behavior and that of their peers (Arnold & Hughes, Reference Arnold and Hughes1999). When adolescents enter a deviant peer group, they often increase their rates of school truancy and dropout, placing themselves in even more contact with each other, which leads directly to increased rates of delinquency (Coie, Terry, Zakriski, & Lochman, Reference Coie, Terry, Zakriski, Lochman and McCord1995). Children's association with deviant peers in adolescence becomes one of the strongest proximal risk predictors for growth in subsequent delinquency (Tremblay, Masse, Vitaro, & Dobkin, Reference Tremblay, Masse, Vitaro and Dobkin1995) and substance use (Price, Drabick, & Ridenour, Reference Price, Drabick and Ridenour2019). The effect of the deviant peer group on individuals’ behavior is evident in other social contextual research on gang involvement (Thornberry & Krohn, Reference Thornberry, Krohn, Stoff, Breiling and Maser1997) and on the influence of aggressive children in classroom settings as well (Barth, Dunlap, Dane, Lochman, & Wells, Reference Barth, Dunlap, Dane, Lochman and Wells2004). These findings have raised questions about the effectiveness of group interventions that aggregate antisocial youth.

One of the success stories of translational research is the development, testing, and refinement of prevention and treatment of antisocial behavior (Weisz & Kazdin, Reference Weisz and Kazdin2010). One of the several intervention programs that has been developed and tested is the Coping Power program, based on a contextual social-cognitive model of children's functioning (Lochman & Wells, Reference Lochman and Wells2002). This intervention program was one of the first to show that interventions targeting children's self-regulation could have a significant short- and long-term effect (3–4 years postintervention) on reducing multiple forms of antisocial behavior (e.g., Lochman et al., Reference Lochman, Baden, Boxmeyer, Powell, Qu, Salekin and Windle2014; Lochman, Boxmeyer, et al., Reference Lochman, Boxmeyer, Powell, Qu, Wells and Windle2009; Lochman & Wells, Reference Lochman and Wells2003, Reference Lochman and Wells2004; Lochman, Wells, Qu, & Chen, Reference Lochman, Wells, Qu and Chen2013), and improving their academic outcomes (Lochman et al., Reference Lochman, Boxmeyer, Powell, Qu, Wells and Windle2012). The 1-year follow-up effects on substance use and delinquency have been found to be mediated by program-induced changes in children's attributional biases, outcome expectations for aggression, internal locus of control, and consistent parental discipline (Lochman & Wells, Reference Lochman and Wells2002). The intervention effects have been found in clinic as well as school-based settings, and in other cultural environments (Helander et al., Reference Helander, Lochman, Högström, Ljòtsson, Hellner and Enebrink2018; Ludmer, Sanches, Propp, & Andrade, Reference Ludmer, Sanches, Propp and Andrade2018; Muratori, Milone, et al., Reference Muratori, Milone, Manfredi, Polidori, Ruglioni, Lambruschi and Lochman2017, Reference Muratori, Milone, Levantini, Ruglioni, Lambruschi, Pisano and Lochmanin press; Mushtaq, Lochman, Tariq, & Sabih, Reference Mushtaq, Lochman, Tariq and Sabih2017; Zonnevylle-Bender, Matthys, van de Wiel, & Lochman, Reference Zonnevylle-Bender, Matthys, van de Wiel and Lochman2007). These randomized trials generally show that the Coping Power intervention resulted in improvements in multiple indices of problem behavior compared to a control group, and to have at least equivalent effects with other forms of individualized intervention.

Despite the overall success of this intervention strategy, concern about negative peer effects suggest that refinement of the intervention may be needed for some children, and some aspect of the intervention delivery may be potentially ineffective or iatrogenic. Several strands of intervention research have suggested that aggregating high-risk children into groups is potentially iatrogenic (Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, Reference Dodge, Dishion and Lansford2006). The Cambridge–Sommerville study had found 30-year iatrogenic effects on adult adjustment (criminal behavior, alcoholism, and mental health problems) as a function of randomization to the multicomponent intervention condition (McCord, Reference McCord, Martin, Sechrest and Redner1981, Reference McCord, McCord and Tremblay1992). The yoked control design enabled the reanalysis of long-term outcomes of intervention youth who were involved in summer camps, in comparison to their yoked controls. In a later study, a follow-up of the Adolescent Transitions Program found that youth randomized to a cognitive-behavioral group focusing on self-regulation resulted in improvements in observed family interaction, but unfortunately, also resulted in increases in youth reports of smoking and teacher reports of problem behavior at school at 1-year follow-up (Dishion & Andrews, Reference Dishion and Andrews1995) and at 3-years follow-up (Poulin, Dishion, & Burraston, Reference Poulin, Dishion and Burraston2001). Analyses of the iatrogenic group conditions revealed that subtle dynamics of deviancy training during unstructured transitions in the groups predicted growth in self-reported smoking and teacher ratings of delinquency (Dishion & Tipsord, Reference Dishion and Tipsord2011). Thus, some group interventions may escalate, rather than reduce, youth behavior problems. Research about deviant peer influences was sufficiently worrisome to lead some researchers to suggest caution when aggregating high-risk youth in clinical, educational, or correctional settings (Dodge et al., Reference Dodge, Dishion and Lansford2006; Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Dishion and Burraston2001).

However, other research has not found evidence for iatrogenic deviancy training effects within group interventions for disruptive youth (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Caron, Ball, Tapp, Johnson and Weisz2005), and there are certain advantages for using group-based intervention. The benefits fall into at least four areas. First, working with children in groups is more cost-effective than individually delivered intervention (Mager, Milich, Harris, & Howard, Reference Mager, Milich, Harris and Howard2005). This is an important consideration at all levels of mental health service delivery, and could certainly be a factor, from a public health perspective, in making preventive interventions readily available to a broad spectrum of the population. Second, group reward systems and peer reinforcement can play an important role in assisting children to attain intervention-related goals, and thus to generalize behavioral improvements resulting from intervention to children's real-world school and home settings (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Dishion and Burraston2001). As children practice self-regulation and social problem-solving skills in groups, these skills can affect how children perceive stressful and frustrating situations in their home and community, as well as at school, leading to potentially similar rates of behavioral improvement in both home and school settings (e.g., as in Mushtaq et al., Reference Mushtaq, Lochman, Tariq and Sabih2017). Third, groups can permit children to develop prosocial leadership skills (Flannery-Schroeder & Kendall, Reference Flannery-Schroeder and Kendall2000). Fourth, the group format permits children to practice learned social and behavioral skills (Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Dishion and Burraston2001). Inclusion of peers in small group interventions facilitates opportunities for practice of social and emotional skills, feedback about social and emotional skill performance, and fosters children's abilities to generalize use of skills with peers (Lavallee, Bierman, Nix, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, Reference Lavallee, Bierman and Nix2005). Activities such as peer role-playing, modeling, and reinforcement of adaptive behavior are only available within small group formats (Mager et al., Reference Mager, Milich, Harris and Howard2005).

While many agree that the potential for deviancy training in group interventions for disruptive youth may occur, despite these potential benefits, there has been a lack of well-controlled studies to confirm whether iatrogenic effects are due to a group format rather than other factors. One of the complexities of interpretation in the studies on iatrogenic effects is that the studies that do find negative effects were not designed with this scientific goal and are often limited in design and method (see Dishion & Tipsord, Reference Dishion and Tipsord2011). To conclusively address this concern, Lochman, Dishion, et al. (Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015) designed a study to randomly assign aggressive youth to receive the same intervention content (in this case Coping Power) in either group or individual formats and to examine potential individual characteristics of the youth that might moderate intervention effects. Because of the existing evidence base for group-administered Coping Power, Dishion and Lochman believed this approach provided a unique and unprecedented opportunity to rigorously compare the effects of group versus individual formats. Even though there were no overall negative iatrogenic effects of the program in the prior studies, and were significant prevention effects, the group format may have minimized the strength of the intervention's potential effects. Lochman, Dishion, et al. (Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015) found that although children in both conditions demonstrated significant reductions in teacher- and parent-reported behavior problems through the end of a follow-up, 1 year after the intervention ended, the degree of improvement on teacher-reported outcomes was significantly greater for children receiving the individual version of the program. The results indicated that the group format had particularly weak effects on teacher-rated conduct problems for certain types of children with particularly poor inhibitory control. Thus, we began to consider more carefully the characteristics of children and of the intervention process that might indicate which factors predict outcomes for aggressive children seen in group interventions.

Youth Characteristics and In-Session Behaviors That Moderate Group Effects

As discussed above, some youth respond relatively weakly to group-based interventions, while other youth do well in group-based interventions and may benefit just as much as they might in an individual intervention. However, little research exists indicating which youth do well in a group-based versus individually formatted intervention. Identifying specific characteristics of the individual may help us to predict which type of intervention would be best for a particular child, thus maximizing the cost-benefit ratio. Consistent with an emerging emphasis to identify moderators of intervention effects on treatments for youth (e.g., La Greca, Silverman, & Lochman, Reference La Greca, Silverman and Lochman2009), this study examined whether specific individual characteristics and in-session behaviors moderated responses to group versus individual interventions, thus beginning the slow process of identifying “what works for whom” (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Belsky, Crowley, Latendresse, Aliev, Riley and Dodge2015).

Inhibitory control

Inhibitory control is a temperamental trait that indicates a tendency to be cautious and controlling of one's personal behavior and involves conceptualizing future consequences and goal setting (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Gatchalian, & McClure, Reference Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Gatchalian and McClure2012). Children with low levels of inhibitory control may be less able to resist intense angry reactions to frustrations and to resist short-term positive gratification they may receive for engaging in externalizing behaviors (e.g., meeting social goals for dominance and revenge; receiving peer attention for engaging in the behavior; Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015). Children's inhibitory control has been shown to be a relevant factor in reducing high-risk boys’ substance abuse initiation (Pardini, Lochman, & Wells, Reference Pardini, Lochman and Wells2004) and delinquency (Hinnant & Forman-Alberti, Reference Hinnant and Forman-Alberti2018), and making them less sensitive to other risk factors in their environment, such as deviant peer effects (Hinnant & Forman-Alberti, Reference Hinnant and Forman-Alberti2018).

Prior research with the current sample

Regarding response to intervention, Lochman, Dodge, et al. (Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015) found that children's levels of inhibitory control, based on parent-rated temperament ratings, moderated the main effect of group versus individual intervention format on teacher-rated externalizing problems. Children in the group condition with high baseline levels of inhibitory control were found to have the greatest reductions in teacher-rated externalizing behavior in comparison to children in the group condition with low levels of inhibitory control and to children in the individual condition. In contrast, baseline levels of inhibitory control did not differentially influence the course of teacher-rated externalizing problems for children receiving individual sessions.

Oxytocin receptor gene

The oxytocin system is relevant to children's social functioning as it is associated with various aspects of social cognition and behavior in both human and animal studies. Oxytocin has been found to be important for attachment, bonding, trust, and social motivation (Gordon, Martin, Feldman, & Leckman, Reference Gordon, Martin, Feldman and Leckman2011). It also influences how individuals respond to others; intranasal oxytocin administration has been found to improve emotion recognition (Guastella et al., Reference Guastella, Einfeld, Gray, Rinehart, Tonge, Lambert and Hickie2010) and increase the amount of time attending to the socially informative eye region of the face (Andari et al., Reference Andari, Duhamel, Zalla, Herbrecht, Leboyer and Sirigu2010). Because of its important role in social cognition, the oxytocin system may influence how an individual responds to the social aspects of a group-based intervention. Although increased awareness of social stimuli and affiliative behavior is typically viewed as advantageous, in the context of a group-based intervention, in which the other members of the group are at risk for aggression, this could potentially be detrimental as it may promote attachment to deviant peers and increase the likelihood of acting out in order to gain social approval from these peers. Conversely, youth with lower levels of social awareness may benefit from the opportunities provided by the group context to practice social skills and become more aware of the emotions and perspectives of others.

Prior research with the current sample

The current study focuses specifically on the variation in a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the oxytocin receptor gene, rs2268493, which has been associated with social responding and behavior in a number of previous studies. In our previous study, Glenn et al. (Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer and Qu2018) found that children's genotype on the oxytocin receptor gene SNP rs2268493 significantly moderated the intervention format effect on teacher-rated externalizing problems. In the group format, children carrying the G allele were less responsive to the intervention than children in the individual format, as indicated by teacher ratings of problem behavior 1 year later. In contrast, children with the A/A genotype showed reductions in externalizing behavior regardless of intervention format.

Autonomic nervous system (ANS) functioning

With regard to children's emotion regulation, the separate effects of the ANS branches can provide specific information about children's capacities for emotion regulation and interpersonal behavior (Jiminez-Camargo, Lochman, & Sellbom, Reference Jimenez-Camargo, Lochman and Sellbom2017; Kassing, Lochman, & Glenn, Reference Kassing, Lochman and Glenn2018), and their self-control and sensitivity to reward and punishment (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) prepares the body to respond to a perceived stressor with a “fight-or-flight” response (Muñoz & Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, Reference Muñoz and Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous2011). SNS activity is typically indexed with skin conductance level (SCL), which indicates the degree of electrodermal activity that occurs and measures how the skin conducts electricity. SCL reactivity indicates a change in SCL from a baseline level to a period after a perceived stressor and indicates an activation of the SNS's “fight-or-flight” response, with accompanying increases in heart rate, oxygen flow, and perspiration (Boucsein, Reference Boucsein2011). Higher SCL activation has been conceptualized as facilitating behavioral inhibition through the production of fear and anxiety (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2001). Research has indicated that low levels of skin conductance reactivity are associated with higher levels of youth problem behaviors (Posthumus, Böcker, Raaijmakers, Van Engeland, & Matthys, Reference Posthumus, Böcker, Raaijmakers, Van Engeland and Matthys2009). Jimenez-Camargo et al. (Reference Jimenez-Camargo, Lochman and Sellbom2017) found that lower SCL reactivity was concurrently related to more externalizing behavior problems within the at-risk aggressive sample to be examined in the current study.

In contrast to the activation quality of the SNS, the parasympathetic nervous system functions by returning the body back to baseline after a fight-or-flight response (Bubier, Drabick, & Breiner, Reference Bubier, Drabick and Breiner2009). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) has been found to be a valid and reliable peripheral marker of the parasympathetic nervous system's role in facilitating self-regulation (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). RSA refers to the ebbing and flowing of heart rate across the respiratory cycle and has been described as a measure of the vagal brake, which rapidly mobilizes or calms a person (Porges, Reference Porges1995). High RSA at rest can indicate the vagal brake is engaged and is associated with prosocial behavior (Porges, Reference Porges1995; Kassing et al., Reference Kassing, Lochman and Glenn2018), but high RSA reactivity indicates that the vagal brake is not engaged and is associated with anxiety and social maladjustment (Gazelle & Druhen, Reference Gazelle and Druhen2009) and problem behaviors (Vasilev, Crowell, Beauchaine, Mead, & Gatzke-Kopp, Reference Vasilev, Crowell, Beauchaine, Mead and Gatzke-Kopp2009). Low RSA reactivity, in contrast, is a statelike response to a stressor and promotes self-regulation and coping. Research has found that children in a community sample with higher RSA reactivity had more externalizing behaviors and greater increases in delinquency symptoms over time (El Sheikh, Hinnant, & Erath, Reference El-Sheikh, Hinnant and Erath2011). Similarly, but within the at-risk sample of aggressive children noted previously, Jimenez-Camargo et al. (Reference Jimenez-Camargo, Lochman and Sellbom2017) found that high RSA reactivity, along with low SCL reactivity, were associated with more concurrent externalizing behavior.

Prior research with the current sample

Regarding group versus individually administered interventions, Glenn et al. (Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Kassing and Romero2019) found that baseline SCL influenced responding to the intervention regardless of format, whereas baseline RSA differentially influenced responding to the format of the intervention. For children receiving the group intervention, those with low baseline RSA showed less improvement in their rates of proactive and reactive aggressive behavior than those with high RSA. This study did not examine the role of SCL and RSA reactivity in predicting differential outcomes. As noted above, RSA and SCL reactivity assesses children's response to stressors and have been found to be related children's social and behavioral maladjustment (Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, Reference Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp and Mead2007; Jimenez-Camargo et al., Reference Jimenez-Camargo, Lochman and Sellbom2017). For these reasons, and because RSA reactivity to specific emotions, rather than baseline RSA, has been found to moderate children's response to intervention for early onset aggression (Gatzke-Kopp, Greenberg, & Bierman, Reference Gatzke-Kopp, Greenberg and Bierman2015), the current study will examine the role of RSA and SCL reactivity as moderators, rather RSA and SCL baseline as examined in our earlier studies (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Kassing and Romero2019).

In-session behaviors

The current study also sought to examine how group leaders’ and individual children's behaviors during sessions impact the children's outcome behaviors. To understand which youth increase smoking and delinquent behavior following the Adolescent Transitions Group intervention, videotapes of the sessions were coded for each youth's deviancy training and other negative and positive behaviors. Observations of youth revealed that those youth who engaged in deviancy training during unstructured sessions were more likely to increase their smoking and delinquent behavior at school (Dishion, Poulin, & Burraston, Reference Dishion, Poulin and Burraston2001).

Therapist effects have been found to have notable effects in psychotherapy research (Magnusson, Andersson, & Carlbring, Reference Magnusson, Andersson and Carlbring2018), but little attention has been paid to therapists’ abilities to deliver evidence-based treatments and to best train them (Fairburn & Cooper, Reference Fairburn and Cooper2011). One of the most neglected areas in group intervention research has been that of therapist effects on groups (Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer, & Burlingame, Reference Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer and Burlingame2010), especially with children. With adult group treatment clients, there is some evidence that clients who report the best effects have therapists (a) who provide appropriate structure and (b) who have warm, nonhostile interpersonal clinical skills (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer and Burlingame2010). Therapists’ ability to regulate their emotional reactivity, triggered by clients, provides an effective model to the clients for their own emotional regulation (Pavio, Reference Pavio2013), and it has been proposed that group leaders’ management of their emotional presence in groups is an important element of group treatment (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer and Burlingame2010). Thus, a key dimension of adult leadership of youth intervention groups is anticipated to be clinical skill, which can be defined as adult regulation of their own emotions during groups to create a safe and secure setting for youth engagement (Stewart, Christner, & Freeman, Reference Stewart, Christner, Freeman, Christner, Stewart and Freeman2007).

Prior research with the current sample

Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell, and Qu (Reference Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell and Qu2017) found that children's and leaders’ behaviors during group intervention sessions for aggressive children served as important predictors of children's behavioral functioning, especially in the school setting, from preintervention through a 1-year follow-up after the intervention was completed. Children's in-session negative behaviors predicted their externalizing behaviors in the home and school settings through the follow-up year. Leaders’ group management skills did not emerge as a predictor of outcomes; however, therapists’ use of clinical skills (e.g., warmth and nonreactivity) predicted less decrease in children's teacher-rated conduct problems.

The Current Study

In the current study, we will extend our study of the same set of moderators through a long-term follow-up of these at-risk aggressive youth. We will determine if the social, cognitive, and emotional factors that moderated intervention format in the short-term following intervention will moderate and predict children's externalizing behavior outcomes at a long-term follow-up, 4 years after the completion of intervention and when the youth had completed their first year of high school. Based on our prior findings, we hypothesize in the current study that children's preintervention inhibitory control, their variant of the oxytocin receptor gene, and their RSA and SCL reactivity will moderate the long-term teacher-rated externalizing behavior outcomes for children seen in group intervention versus those in individual intervention. Children with poor inhibitory control, with the G/G genotype, and with high SCL reactivity and high RSA reactivity are expected to have weaker reductions in teacher-rated externalizing behavior problems than similar children receiving individual intervention. It is also hypothesized that, within the group format condition, children would have greater reductions in teacher-rated conduct problems if their therapist had greater clinical skill and if the individual children had displayed fewer negative behaviors during the group sessions. The current study will also explore research questions examining whether the same moderators and predictors can generalize to parent-rated externalizing problems.

Method

Sample

Children included in the analyses were drawn from a randomized controlled trial examining the relative effectiveness of group and individual formats of Coping Power (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015). The randomized controlled trial involved 360 children recruited from 20 elementary schools. Recruitment involved screening by teachers and parents for eligibility; because teacher screenings have been found to be more predictive of later externalizing problems (Hill, Lochman, Coie, Greenberg, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, Reference Hill, Lochman, Coie and Greenberg2004), they were considered the primary screening and were more stringent whereas the parent screening was used to exclude children who showed few signs of aggression in the home setting. Fourth-grade teachers completed the Reactive and Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (Dodge, Lochman, Harnish, Bates, & Pettit, Reference Dodge, Lochman, Harnish, Bates and Pettit1997) on each student in their classrooms. Ratings were compiled across all 20 schools, and a cutoff score corresponding to the 25th percentile was determined, indicating moderate to high levels of aggressive behavior.

A randomized list of eligible children was created for each school, and families were contacted according to their placement on the list. Study procedures were described to families over the phone, and face-to-face assessments were scheduled for interested families. The Behavior Assessment System for Children—2nd Edition (BASC-II; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus1992) Aggression scale (parent rated) was the second screening. Children whose parents rated them within the average range or above on the BASC aggression scale were invited to enroll in the study. Families were contacted and assessed until 6 children were enrolled at each school. Of the 1,131 students eligible from the teacher screening, 499 were successfully contacted. Of those, 139 were excluded because they did not schedule or missed the initial appointment (45), did not pass the parent screening (41), declined to participate (32), moved (15), were a sibling of another participant (3), or had cognitive limitations (3). Assignment to condition was made at the school level. Schools were paired on demographic factors (percent receiving free or reduced-price lunch and percent minority) and, within the pairs, one school was randomly assigned to either Group Coping Power (GCP) or Individual Coping Power (ICP).

Three annual cohorts were recruited, resulting in a total sample of 360 participants. The mean age at Time 1 assessment was 10.17 years (range of 9.17–11.79), and 65% of the sample were boys. The race and ethnicity of the sample was 78.1% African American, 20.3% Caucasian, 1.4% Hispanic, and 0.3% other. The family income for the sample was below $15,000 for 29.9% of the sample, in the $15,000–$29,999 range for 31.8% of the sample, in the $30,000–$49,999 range for 20.5% of the sample, and above $50,000 for 17.6% of the sample.

All 360 participants are included in the current study's analysis of inhibitory control as a moderator, and the full 180 GCP youth were included in the analyses of therapist and child behaviors within group sessions predicting outcomes. However, because of data collection difficulties, smaller subsets of the sample were available to be used in analyses of the oxytocin genotype and of the psychophysiological moderators. Of the full sample, 94.4% (n = 340) completed the physiological measurements prior to the intervention. However, recording errors during baseline or the first block of the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) reduced the available sample for these two moderators. The final sample for psychophysiological assessments included 242 participants for RSA (117 ICP, 125 GCP) and 302 participants for SCL (143 ICP, 159 GCP). Of the total sample, 71.4% (n = 257) provided a DNA sample that was successfully genotyped for rs2268493 (128 ICP, 129 GCP).

Intervention

Coping Power is an evidenced-based manualized intervention (Lochman, Wells, & Lenhart, Reference Lochman, Wells and Lenhart2008) designed to target key social-cognitive deficits in children with aggression. It addresses social information-processing distortions (e.g., hostile attributional biases) and deficiencies (e.g., dominance and revenge-oriented social goals; problem solving that relies on direct action strategies rather than verbal assertion or help seeking). It also addresses tendencies to become overaroused, especially when angry, when social problems are perceived. Using cognitive-behavioral strategies, children are taught to use social problem solving, goal setting, and emotional regulation skills. The full curriculum includes a parenting component, but it was not implemented in this study. For both ICP and GCP conditions (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015), students attended 32 weekly meetings at school, beginning in the late spring of fourth grade and continuing through fifth grade. Twenty Coping Power leaders were responsible for delivering content, plus several coleaders. All Coping Power leaders were involved in the delivery of both conditions. Coping Power leaders were doctoral- and master's-level clinicians, and advanced graduate students in clinical or school psychology. Leaders participated in a 6-hr initial training. To ensure high fidelity implementation, two doctoral-level psychologists who each had more than 8 years of experience implementing Coping Power met with the interventionists weekly to monitor and provide feedback on program implementation. The interventionists also received detailed supervisory feedback on video-recorded GCP and ICP sessions on a monthly basis to ensure that program implementation remained consistent and of high quality, across interventionists and across the two intervention formats. Interventionists also completed a measure of fidelity after completing each ICP and GCP intervention session, rating whether they had covered each session objective “completely,” “partially,” or “not at all.” GCP leaders and ICP leaders indicated that they “completely” or “partially” completed 91.07% and 86.43% of objectives, respectively.

GCP

GCP groups included the six children enrolled in the project at each GCP school. Sessions were scheduled for 50–60 min and were co-led by a Coping Power staff member and another clinician (e.g., graduate student of school counselor). Group leaders remained the same throughout children's involvement in the program. The majority of the groups were mixed gender; 2 of the 30 groups consisted of all boys. The GCP and ICP curricula covered the same content, though specific activities were tailored for each condition (e.g., children in GCP had opportunities to practice specific skills through role-plays with their peers and receive feedback from their peers at the end of each session). Children in GCP also participated in monthly individual meetings (approximately nine individual sessions total, lasting 15- to 30-min each), consistent with the standard Coping Power curriculum, which were included to build rapport, assess comprehension of material, and address individual issues.

ICP

Children in the ICP condition met one-to-one with a Coping Power staff member for 32 30-min sessions, which included interactive activities (e.g., role-plays) between the student and the Coping Power leader, rather than with peers (as in GCP).

Procedure

Questionnaire data

Preintervention (Time 1) measures were completed with children and parents at the time of enrollment. Students and parents completed midintervention assessments (Time 2) in the summer after fourth grade. Postintervention assessments (Time 3) were completed in the summer after fifth grade. One-year follow-up assessments (Time 4) were completed after sixth grade, 2-year follow-ups after seventh grade (Time 5) and 4-year follow-ups after ninth grade (Time 6). Most assessments took place in participants’ homes. Children and parents were interviewed separately by research staff members blind to the children's condition assignment. Parents received $50 for each assessment interview and children received $10. Teachers received $10 for each student assessed in Times 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Physiological measures

Physiological measures were collected at preintervention (Time 1). A BioLog™ recorder was administered to measure heart rate and skin conductance. It was attached to participants through bioelectric and transducer input assemblies. Interviews were conducted in various locations (e.g., participant's home, research office, or public library). Due to the variability of location conditions and the lack of a controlled environment, interviewers were instructed to record the temperature (M = 74.1, SD = 4.1) and humidity (M = 46.6, SD = 8.3) level at the time of the physiological assessment. Temperature and humidity are two environmental factors that influence electrodermal activity through hydration of the stratum corneum (outermost layer of the epidermis; Cacioppo, Tassinary, & Berntson, Reference Cacioppo, Tassinary and Berntson2007). Boucsein (Reference Boucsein2011) suggested a room temperature of 73.4 ◦F. However, a range of room temperatures has been represented in the literature. For example, Venables and Christie (Reference Venables, Christie, Prokasy and Raskin1973) utilized a laboratory temperature range between 68 ◦F and 86 ◦F. Temperature and humidity are entered in the current analyses as control variables.

To measure heart rate and interbeat intervals (collected to determine RSA), one electrode was placed above the right collarbone, another behind the left knee, and a reference electrode was placed on the right side of the neck. To measure SCL, electrodes were placed on the volar surface of the distal phalanx of the first and third fingers on the participant's nondominant hand.

Following the placement of the electrodes, each participant watched a 128-s video. The video depicted Hawaiian scenery and was meant to be neutral and unlikely to elicit an emotional reaction. We elected to have participants watch a video rather than sit quietly because it gave them something to watch and attend to, thus minimizing the likelihood that they would fidget or talk. Baseline RSA and SCL were calculated using data collected during the last 60 s of the video, giving them time to acclimate to the testing equipment.

After the video, participants were instructed to play the IGT (Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, & Anderson, Reference Bechara, Damasio, Damasio and Anderson1994), a 25-min computerized decision-making task specifically designed to invoke stress. The task consisted of five blocks of 20 cards for a total of 100 cards. Prior to playing the computerized task, instructions were read to the participants. At that time, participants were made aware that they would gain or lose money each time they selected a card from one of the four available decks (decks A, B, C, and D). They were provided a starting balance of $2,000 in virtual play money and were told the goal of the task was to earn as much money as possible. After each card draw, money was earned. After some cards were drawn, participants were both given money and asked to pay a penalty. Turning cards from decks A or deck B yielded a win of $100; turning from deck C or deck D yielded a win of $50. Though decks A and B yielded a higher gain, they cost more in the long run due to high penalties. Penalties were determined by a preprogrammed schedule unknown to the participant.

RSA was derived from techniques in the manual Inter-Beat-Interval Editing for Heart Period Variability Analysis: An Integrated Training Program with Standards for Student Reliability Assessment (Porges, Reference Porges2007). This manual was designed for use alongside the CardioEdit and CardioBatch computer programs. Porges's vagal tone method of calculating RSA is empirically supported (Denver, Reed, & Porges, Reference Denver, Reed and Porges2007). For a detailed description of the Porges–Bohrer method, see Lewis, Furman, McCool, and Porges (Reference Lewis, Furman, McCool and Porges2012). The first procedure involved cleaning interbeat interval data collected using the Biolog. As per procedures outlined in the manual, each participant's heart rate data was hand edited using the CardioEdit program in order to remove any unwanted artifacts. Artifacts are errors in the interbeat interval data that are likely due to the digitizing process of the data or to physiological anomalies. After data cleaning, RSA was extracted from one of the predominant rhythms exhibited in the data via computations of the participant's heart period series using the CardioBatch computer software. Baseline RSA was based on the 60-s baseline period. SCL data was processed using Ledalab. Artifacts were removed and the average skin conductance level over the 60-s period was calculated.

SCL and RSA were measured for the duration of the 25-min IGT. To create reactivity scores for each block, average values of RSA/SCL during each block were subtracted from baseline values. During the first block, the participants were largely getting accustomed to the frustrating task, so the first block reactivity scores were used in analyses given that they are likely more representative of reactivity.

DNA

Following their enrollment in the main study, families were given the option to participate in a supplemental study involving the collection of DNA from children. Parents and children signed consent and assent forms specific to the DNA collection procedures. Families who chose not to participate in the DNA collection continued in the main study as planned.

Child DNA was collected via buccal cells by brushing the inside of the cheek with a buccal brush. Participants were instructed to gently rub the inside of each cheek with separate buccal brushes for approximately 30 s. The brushes were then placed in individual plastic cylinders marked with the participant's study ID number for storage and transport. Following collection, the cylinders were temporarily stored in a research lab refrigerator, and then they were transported to the Genomics Core Facility at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for genotyping. Parents and children each received $5 for participating in the collection of DNA. Information about genotyping of the SNP rs2268493 can be found in Glenn et al. (Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer and Qu2018). The distribution of genotypes was G/G (N = 14), G/A (N = 52), and A/A (N = 191).

Measures

BASC (Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus1992)

The BASC is a behavior problem checklist that was completed by children's teachers and parents, and that has demonstrated strong reliability and construct validity (Doyle, Ostrander, Skare, Crosby, & August, Reference Doyle, Ostrander, Skare, Crosby and August1997; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus1992). The externalizing composite scores have good internal consistency for teacher and parent ratings (Chronbach's alpha of .80–.89; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus1992), and were used in the current study.

Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire–Parent Report (Rothbart, Ellis, Rueda, & Posner, Reference Rothbart, Ellis, Rueda and Posner2003)

This measure was used to assess the child characteristic of inhibitory control. Internal consistency for this subscale was good in prior Coping Power samples (α = .78; Pardini et al., Reference Pardini, Lochman and Wells2004).

Cognitive-Behavioral Group Coding System

A behavioral coding system was developed to rate child and leader behavior during Coping Power group sessions; coder training, reliability procedures, and coding details are included in the paper by Lochman, Dishion, et al. (Reference Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell and Qu2017) that used this measure. The Cognitive-Behavioral Group Coding System utilizes a macro rating scale in which the interactions between each participant and all other participants are recorded in a matrix. Separate ratings were made for the behavior of each child participant and each group leader during the first 10 min, middle 10 min, and last 10 min of each session, and the ratings were aggregated for analyses. Children and leaders are coded on each item individually for each time segment. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Child-rated behaviors include positive child behaviors (e.g., showing involvement and interest in group discussion and activities; initiating positive and friendly interactions with other group members; other children initiating reciprocal positive and friendly interactions toward this child) and negative child behaviors (e.g., deviant talk, exhibiting off-task, inattentive behavior; engaging in silly or disruptive behavior; demonstrating a negative, hostile attitude; exhibiting verbal or physical aggression; and appearing to trigger these negative behaviors in other group members). Leader-rated behaviors include group management skills (e.g., leader sets clear expectations and rules for group behavior; enforces rules for group behavior effectively; provides strategic reinforcement for desired behaviors, provides consequences for rule violations, adheres to an agenda/manages group time effectively; quiets the children and elicits their attention effectively; provides clear rationale for new topics and activities; provides clear instructions; reviews key teaching points; actively assesses children's comprehension, creates “teaching moments,” leader elaborates the content beyond the manualized material) and clinical skill (e.g., leader's tone is warm and positive; leader demonstrates professionalism in dress, behavior, and level of self-disclosure; leader is overly rigid, reverse scored; leader appears frustrated, angry, or irritable, reverse scored). There was acceptable to excellent internal consistency for the positive behaviors variable (.90) and for the negative behaviors variable (.77). Excellent internal consistency was evident for the leaders’ group management variable (.92). Good internal consistency was found for the clinical skills variable (.84).

Analytic strategy

For this study, a three-level linear growth curve model was constructed by using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) 7.0 with full maximum likelihood estimation method (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). The times of measurement was Level 1, individual child characteristics was Level 2, and nested within the intervention units (i.e., school) was Level 3. The individual growth trajectories were fitted in the Level 1 model. Each child's outcome scores were modeled as a function of time. For teacher outcomes, the data collection dates at each wave were very close in time. Therefore, the time variable for teacher outcomes is 0 at baseline, 1 at postintervention, 2 at 1-year follow-up, 3 at 2-year follow-up, and 4 at 4-year follow-up. For parent outcomes, the data collected with each wave were spread across several months, so we took the actual time interval from baseline as the time variable, setting baseline to zero. Each of the growth parameters in the Level 1 model has a substantive meaning and was estimated in the Level 1 model. The intercept was initial status at baseline. Time slope was the linear or quadratic change rate over time in each growth trajectory. Both linear and quadratic growth rates were tested in each analysis and retained.

At Level 2, the person level, temperature and humidity were control variables for the RSA and SCL analyses, and child characteristics (inhibitory control, oxytocin genotype, RSA, and SCL) were examined as potential moderators of the child's rate of change and effect of intervention on behavior outcomes over time at Level 1 model, using robust standard errors. Child characteristics were group mean centered. The intercept and time slope were treated as random effects at Level 2 and Level 3, and the random effects were retained in the models.

ICP and GCP intervention conditions (ICP = 1 and GCP = 0) were randomly assigned to schools, and the school received the same intervention condition in 3 successive years (cohorts). At Level 3, we controlled intervention condition on intercept, and we detect effects of children's characteristics on intervention (indicating interactions of intervention condition and child's characteristic) on child's behavior change rate. The three-level growth curve model captured children's behavior outcome changes over time in two growth parameters (intercept and time slope). The variation in the growth parameters was partitioned into (a) the variation among children within intervention unit (school) as captured in the Level 2 model, and (b) the variation among intervention units as represented in the Level 3 model.

Results

Table 1 provides the means and standard deviations for the externalizing outcome measures by intervention condition at each of the five teacher-rated time points and six parent-rated time points. To address missing data, the HLM analyses used full maximum likelihood to estimate model parameters. The retention rates (indicating retention from the full sample at Time 1) for the Coping Power—Group Format parent data (GCP; 99%, 92%, 87%, 80%, and 79% for Time 2–Time 6, respectively) and teacher data (93%, 82%, 48%, and 23% for Time 3–Time 6, respectively), and for the Coping Power—Individual Format parent data (ICP; 89%, 91%, 84%, 78%, and 78% for Time 2–Time 6), and teacher data (89%, 76%, 48%, and 22% for Time 3–Time 6). There were no significant differences between the attrition rates for the two conditions at any of the six time points for the externalizing outcome measures (rated by parents and teachers). Attrition bias was tested by examining whether children's characteristics (gender, racial status, initial level of externalizing behavior in school, and inhibitory control) and intervention condition status differentiated attriters from non-attriters in chi square and logistic analyses for the overall sample. There was little evidence of systematic differential attrition overall, although higher levels of baseline teacher-rated externalizing behaviors predicted higher attrition levels (across both conditions) for teacher ratings at Time 4, there was greater attrition for teacher ratings for Caucasian children than African American children at Time 5 and Time 6, and there was greater attrition for parent ratings for Caucasian children than for African American children at Time 4. Within the subsamples for RSA, SCL, and oxytocin gene moderator analyses, in addition to the four child characteristics noted previously, we examined whether SCL IGT Block 1 differed by attrition status within the SCL subsample, whether RSA IGT Block 1 differed by attrition status in the RSA subsample, and whether oxytocin genotype rates differed by attrition status in the oxytocin subsample. None of these subsample-specific variables were related to attrition status at any time point. The attrition bias analyses within the three subsamples for RSA, SCL, and oxytocin paralleled the results for the overall sample, indicating no systematic attrition bias within the subsamples. Thus, there was no systematic pattern of attrition bias across time.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of behavioral outcomes across time

Note: Teacher ratings were not collected at Time 2. BASC, Behavior Assessment System for Children.

The associations among the moderator variables were examined. Because RSA reactivity and SCL reactivity involved both the baseline levels for these two constructs and the scores during the Block 1 period of the IGT, the relation among these four variables and inhibitory control and the oxytocin genotypes were assessed. Inhibitory control and the oxytocin genotype were only associated with each other, and not with the psychophysiological variables. Children with the A/A genotype had higher inhibitory control than those with the other two genotypes, t (139.3) = –1.98, p < .05. The baseline and IGT Block 1 levels within each of the psychophysiological variables were highly intercorrelated, with r (242) = .80, p < .001 for the relation between RSA baseline and RSA IGT Block 1, and r (302) = .92, p < .001 for the relation between SCL baseline and SCL IGT Block 1. Baseline RSA was also negatively correlated with baseline SCL, r (258) = –.18, p < .01, and with SCL IGT Block 1, r (249) = –.16, p < .01. Analyses also indicated that the Time 1 moderator variables were not significantly associated with the behavioral outcome variables. Overall, the moderator variables were distinct enough from each other to warrant running separate growth models for each outcome.

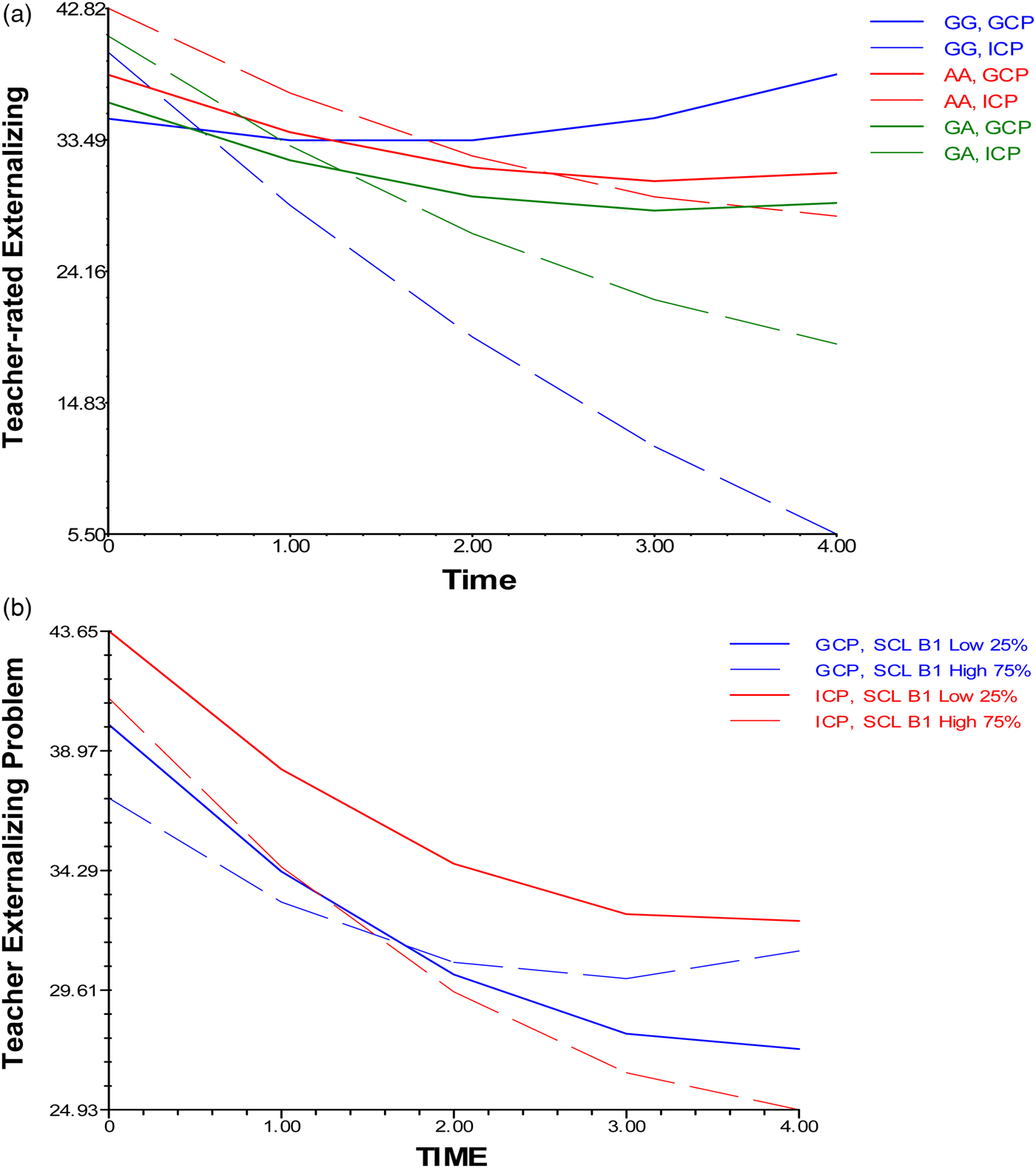

Hypothesized moderator effects of ICP versus GCP comparison

Table 2 summarizes the results of the four HLM analyses testing for hypothesized moderator effects on teacher-rated externalizing behavior. The HLM analyses examined whether children's baseline characteristics moderated the intervention condition effect in the four models for teacher-rated externalizing behavior. Two of the four hypothesized moderators were found to influence the intervention format effects on this outcome. Significant moderator effects were found for the oxytocin receptor gene (the test of the A/A vs. G/G genotype) and for SCL reactivity. The hypothesized moderation effects for inhibitory control and for RSA reactivity were not significant. As depicted in Figure 1a, children with the G/G genotype had sharply declining slopes in teacher-rated externalizing behaviors when they were in the ICP condition, in comparison to when they were in the GCP condition. The curvilinear paths for children with the A/A genotype were relatively similar for the two conditions. Figure 1b illustrates the moderation effect for SCL reactivity, with a sharper decline in the slope of teacher-rated externalizing behaviors for children with low SCL reactivity who had received ICP in comparison to similar children who had received GCP.

Figure 1. (a) Oxytocin receptor gene and (b) skin conductance reactivity moderation of intervention format on teacher-rated externalizing behavior.

Table 2. Hypothesized effects on teacher-rated externalizing: Summary of three-level growth analyses on growth rate

Exploratory moderator effects of ICP versus GCP comparison

Table 3 summarizes the results of the exploratory HLM analyses testing for moderator effects on parent-rated externalizing. There were no moderator effects on the four analyses examining parent-rated behaviors.

Table 3. Research questions on teacher-rated internalizing and parent-rated externalizing and internalizing: Summary of three-level growth curve analyses on growth rate

Leader and child behaviors predicting outcomes within the GCP condition

Table 4 summarizes the results of the four HLM analyses testing predictor effects of group leader and child in-session behaviors on teacher-rated and parent-rated externalizing behavior. The group leaders’ clinical skills were found to predict the path of teacher-rated externalizing behavior, as hypothesized. Children's degree of negative behavior within sessions did not produce a hypothesized predictive effect on teacher-rated externalizing behaviors. Group leaders’ task orientation and children's in-session positive behaviors did not predict outcomes across time, and none of these in-session variables predicted parent-rated outcomes. As depicted in Figure 2, children who had clinically skillful group leaders had greater declines in their teacher-rated externalizing behavior.

Figure 2. Group leader clinical skills predicting children's teacher-rated externalizing behavior.

Table 4. Effect of leader and child behavior within group sessions on outcomes: Summary of three-level growth curve analyses on growth rate

Discussion

The current results indicate that preadolescent aggressive children's social-emotional characteristics continue to predict their response to receiving a cognitive-behavioral Coping Power intervention in either a group format or an individual delivery format even through the 4 years after the end of the intervention. This study originated in collaboration with Tom Dishion because of concerns that a group format for aggressive youth might dampen the degree of effect of a cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention. Prior research with the current sample had found that certain child characteristics did predict response to group intervention at a short term, 1-year follow-up (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015, Reference Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell and Qu2017; Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer and Qu2018, Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Kassing and Romero2019). The current analyses used outcomes (externalizing problems) that were common across models rather than the specific types of conduct problems examined in the prior analyses, to better understand the comparability of the social-emotional-cognitive moderators. Furthermore, as indicated above, ANS reactivity was used, rather than static baseline ANS measures, to examine the ANS effects.

The current results confirm and extend the pattern of prior findings, indicating that several of these classes of characteristics (oxytocin receptor genotype; skin conductance [SCL] reactivity) continue to predict outcomes years later when the youth have moved into high school. The current results also identify child and group leader behavioral styles that predict slopes of outcomes for children who had been assigned to the group format. Consistent with earlier results, the role of moderators only affects intervention format for teacher-rated outcomes and not for parent-rated outcomes, as there were significant declines in parent-rated externalizing behaviors regardless of condition (group vs. individual format). Thus, the moderation of intervention format continues to affect teacher ratings of children's behavior in the schools setting, but these effects do not generalize to parent reports of children's behavior in the home and community settings. Overall, the results have important implications for planning preventive interventions that involve aggressive children, and for the conduct and training for group-based intervention.

Hypothesized teacher-rated externalizing outcomes

Two of the four moderators hypothesized to predict teacher-rated externalizing problems did moderate group format in the growth curve analyses through youths’ entry into high school. However, inhibitory control and RSA reactivity did not emerge as significant moderators.

Inhibitory control as moderator

Although children with lowest inhibitory control had significantly less reduction in their conduct problems at the 1-year follow-up after intervention if they had been involved in the group format rather than the individual format (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015), this pattern was not a significant finding at the longer 4-year follow-up. A nonsignificant trend (p = .095) for the inhibitory control interaction effect suggested that the pattern of moderation may have been weakly present. However, in general, children's level of inhibitory control, as measured with parent ratings, was no longer a robust marker for which children might be better assigned to individual versus group format.

Oxytocin receptor gene as moderator

Analyses using the oxytocin receptor gene SNP rs2268493 indicated, in a partially similar pattern to earlier analyses at the 1-year follow-up (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer and Qu2018), that children with the G/G genotype were most affected by placement in one format or the other. It was apparent that children with the G/G genotype who received Coping Power in an individual format with the therapist had marked reductions in their slope of externalizing problems across time, in comparison to children with the G/G genotype who had been seen in the group format. This relative benefit for G/G genotype children with the individual format was especially apparent in contrast to children with the A/A genotype who had relatively similar response to being seen individually or in groups.

In partial contrast to the results at the 1-year follow-up (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer and Qu2018), children with the G/G genotype who were seen in groups did not fare as well following group intervention. Given prior associations between this gene variant and traits related to social responding (Beitchman et al., Reference Beitchman, Zai, Muir, Berall, Nowrouzi, Choi and Kennedy2012) and reward sensitivity (Damiano et al., Reference Damiano, Aloi, Dunlap, Burrus, Mosner, Kozink and Dichter2014), these children potentially were more prone to the effects of deviant peers, and more likely to bond with other at-risk children who had been in an intervention group with them. However, as the effect of group format on teacher ratings became apparent at the 1-year follow-up and in subsequent years (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015), rather than at the end of the intervention, the potential role for deviant peer involvement could exist more in the years after intervention. Although speculative, the at-risk children may have had the opportunity for unstructured interactions with their peers from the group in these later years. However, the study only used the child component of Coping Power; the parent component provides parents with help on monitoring, supervision, and use of consistent consequences that may limit the impact of deviant peers in general. Alternatively, children who have stronger social orientations, possibly like children with the G/G genotype, may have been more involved with peers in the group condition, less able to deeply incorporate the social-cognitive regulation skills being discussed and practiced, and thus may have internalized the active mechanisms from the intervention less well.

Children with the G/G genotype assigned to the individual delivery format may have had greater potential for social bonding with the therapist. Degree of child bonding with the therapist affects children's outcomes in therapy, including individual sessions (Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, Romanelli, Ellis, Barker, Boxmeyer and Lochmanin press; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Younginer, Lochman, Vernberg, Powell and Qu2019; Ormhaug, Jensen, Wentzel-Larsen, & Shirk, Reference Ormhaug, Jensen, Wentzel-Larsen and Shirk2014). Children who are bonded with the therapist may work harder on therapy activities, remember and incorporate the strategies in flexible ways, and be motivated to receive the therapist's social reinforcement for improved use of coping skills and improved behaviors.

SNS as moderator

The SNS is responsible for individuals’ mobilization of energy when they encounter stressors (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Wells, Boisvert, Lewis, Cooke, Woeckener and Kavish2019), and is indexed by SCL. In our study, when children had low SCL reactivity, considered to be a risk indicator for externalizing behaviors among aggressive children (Jimenez-Camargo et al., Reference Jimenez-Camargo, Lochman and Sellbom2017; Posthumus et al., Reference Posthumus, Böcker, Raaijmakers, Van Engeland and Matthys2009), they declined in teacher-rated externalizing behaviors in equivalent ways whether they had been randomly assigned to the group or individual condition. Individuals with low SCL reactivity have been found to display more proactive, planful aggression in particular (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Wells, Boisvert, Lewis, Cooke, Woeckener and Kavish2019). Thus, aggressive children in our sample who may have been most at risk for increasing levels of conduct problems, especially of this functional type of deliberate aggression, had declining levels of externalizing behavior over time regardless of the format used to deliver the cognitive-behavioral intervention. However, when children had high SCL reactivity, they had greater reductions in externalizing behavior patterns over time when they were seen in the individual format than when they were seen in groups. Children who have a SNS proclivity to be hypersensitive to stressors, with higher SCL reactivity, may be overaroused by interpersonal stressors (Murray-Close, Holterman, Bresland, & Sullivan, Reference Murray-Close, Holterman, Bresland and Sullivan2017), including disruptions and conflicts that can occur during group sessions, and thus may be less able to acquire new knowledge about emotion regulation and problem solving during the sessions. In contrast, aggressive children who have hypersensitive stress responses who are seen individually may be able to understand and practice the intervention's methods for emotional regulation in the safe context of their therapeutic relationship with their therapist. Higher SCL reactivity has been found to be associated with more capability for inhibiting impulses and more ability to anticipate and be concerned about the consequences of one's behavioral problems (Schatz & Rostain, Reference Schatz and Rostain2006). This can permit highly reactive children to set in place deliberate as well as automatic methods for regulating their intense emotions and planning how to cope with social stressors in a manner that leads to increasingly better behavioral regulation over time.

Child and leader behaviors within group sessions that predict teacher-rated externalizing outcomes

Although one aspect of group leaders’ behavior, their clinical skills, and one aspect of children's behavior during group sessions, their negative behaviors, were predictive of children's outcomes through the 4-year follow-up, they differentially predicted different aspects of children's functioning. The clinical skills construct included ratings for not appearing frustrated, angry, or irritable; having a warm and positive tone of voice with students; acting in a mature and professional way (dress, type of humor, and level of self-disclosure that are appropriate for adult intervention staff); and not being overly rigid with the implementation of the manualized intervention activities. Leaders with high levels of clinical skills had children who had reduced slopes of teacher-rated externalizing problems over time, relative to children who had worked with group leaders who had lower levels of these skills. This key role for therapists’ clinical skills continued the predictive pattern we had seen at the 1-year follow-up, indicating the long-term importance of this aspect of therapist functioning. As seen at the earlier follow-up, clinical skills were perhaps surprisingly more important in predicting outcome than were group leaders’ behavioral management and “teaching” styles (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell and Qu2017).

There are at least three ways in which clinical skills, as measured here, can influence children's outcomes (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell and Qu2017). First, group therapists who handle difficult interpersonal provocations from their child clients by exerting inhibitory control over their expression of their own frustration and by effectively regulating their arousal are modeling key processes that can be instrumental for children learning to improve their own emotional regulation over time (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer and Burlingame2010; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Christner, Freeman, Christner, Stewart and Freeman2007). Second, group leaders who respond more frequently in warm ways to the children in their groups are likely providing more social reinforcement for positive child behaviors within the sessions (Follette, Naugle, & Callaghan, Reference Follette, Naugle and Callaghan1996), and facilitating sustained generalized reductions in problem behaviors outside of the group sessions. Third, in a related way, group leaders who respond to children with more warmth are likely to develop stronger therapeutic alliances with the children, and the children can become more engaged with the intervention. Children who have become engaged in the Coping Power intervention by the middle sessions of the program have been found to have greater reductions in externalizing behavior by postintervention (Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, Romanelli, Ellis, Barker, Boxmeyer and Lochmanin press). Children who are more engaged in the intervention may learn the social-emotional skills more deeply.

Clinical and research implications

There are four linked implications of the current set of findings for future research and implementation of group-based interventions for children with aggressive behavior problems. The results and the implications follow directly from our work with Tom Dishion, and indicate that group-based interventions are not as effective as individually delivered interventions for certain children. The implications below follow from our findings that current patterns of child characteristics, and by extension, certain children, have greater reductions in externalizing, and even internalizing, problems through a lengthy period after intervention has ended, and that child and group leader behaviors in group sessions predict children's behavior in subsequent years.

Tailored delivery of intervention format

The current findings extend our prior recommendations that research can assist in tailoring delivery of intervention for aggressive children, by ultimately identifying risk markers and valid screening methods that can channel children into group or individual intervention delivery formats (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer and Qu2018, Reference Glenn, Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Kassing and Romero2019). As noted above, group formats have benefits related to efficiency of delivery and opportunities for use of peer-based intervention activities, but those benefits can come at the cost of weakening intervention impact on externalizing behavior outcomes for some children. The current findings indicate that two areas of constructs may be especially important to further explore. First, aggressive children who have excessive orientation to others and readiness to develop strong social bonds, indexed in this study by an oxytocin receptor gene, appear to be especially good candidates for individual delivery of cognitive-behavioral intervention. Aggressive children without a high level of social orientation can function adequately in group settings, and may make implementation of group sessions easier. Second, aggressive children who are hypersensitive to social stressors, indexed in the current study by high levels of skin conductance reactivity, are very responsive to individual delivery of intervention, in comparison to group delivery. If aggressive children had lower levels of sensitivity to social stressors, then they appeared to have similar outcomes whether receiving group or individual intervention. Thus, future research can explore viable screening methods for aggressive children who are highly oriented to social bonding and who are hypersensitive to social stressors, and prescribe individually delivered interventions for these children.

Development and adaptation of group intervention

The findings of moderators of group intervention as delivered in this study also suggest that future research can examine whether other group-based intervention approaches, or adaptations of the current Coping Power model, could better address the risk mechanisms associated with the children who were less positively affected by a group format. Are there other interventions, or intervention components, that can better address children's tendency to fall into in-group versus out-group schemas, a pattern associated with the oxytocin receptor G/G genotype? Can a group-based intervention better address the emotional dysregulation that can occur with SNS activation to perceived social threats? For example, more relaxation practices could be planned after especially arousing intervention activities. In addition, use of alternative technologies within group settings may be useful in reducing opportunities for unstructured and stressful social interactions, including frequent virtual-reality activities, or use of Internet adjunct components that can reduce the number of group-based sessions needed (e.g., Lochman, Boxmeyer, et al., Reference Lochman, Boxmeyer, Jones, Qu, Ewoldsen and Nelson2017).

Monitoring child behavior during group sessions

Although children's negative behavior during sessions did not moderate intervention format through a long-term follow-up on children's externalizing behavior, the degree of negative behaviors did make a difference in the effect of group format on children's behavioral adjustment, at the earlier 1-year follow-up (Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu and Sallee2015). Training of group therapists can focus on having therapists’ periodically carefully assess each child's negative behavior in the group and then make planned efforts to reduce the antecedents for the negative behavior, when possible, and to increase more fine-grained contingencies for in-group behaviors. Use of co-therapists can be especially useful in regard to frequently monitoring and reinforcing children in group settings. The current findings of decayed intervention effects during the follow-up period for some children suggest that future research could use sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART; Almirall, Nahum-Shani, Sherwood, & Murphy, Reference Almirall, Nahum-Shani, Sherwood and Murphy2014) to re-randomize children who had displayed above-average levels of negative behaviors in group sessions to augmented intervention methods. One example that follows from the current trial, which used only the Coping Power child component, would be to re-randomize children with highly negative behaviors in group sessions to offering the Coping Power parent component, or not, in order to directly test this assumption. The Coping Power parent component focuses on parents’ provision of positive social reinforcement, positive support for the child, along with consistent consequences for home and in-school behavior, potentially improving children's depressive and anxiety reactions, as well as their externalizing behavior problems. Other intervention adaptations could also be used to augment the delivered program, such as mindfulness training elements, and examined within the SMART trial approach.

Group leader training

One of the key implications from this set of studies follows from Tom Dishion's prior recommendations about the critical importance of highly intensive and structured training for group therapists (Dishion & Dodge, Reference Dishion, Dodge, Dodge, Dishion and Lansford2006), as they learn to implement these cognitive-behavioral interventions. In addition to providing group therapists with precise skills in how to monitor and provide consequences for children's behavior in the groups, these findings demonstrate that therapists’ clinical skills, as rated during group sessions, predict children's externalizing behaviors during the years after the program has been completed. The simple story is that group therapists who are positive and professional in their interactions with their group children, and who are less angry or irritable with them, have children who exhibit greater reductions in externalizing behavior problems over time. In a sense, the clinicians’ behavior may provide a protective effect for children who are in a group intervention that carries certain risk for deviant peer interactions and escalating group emotional and behavioral contagion. There are several plausible ways in which group leader clinical skills may affect children's externalizing behavior outcomes, and future research can explore these processes. Therapists’ own emotional regulation, their use of social reinforcement, and their ability to stimulate child engagement in sessions can all be involved (Boxmeyer et al., Reference Boxmeyer, Miller, Henkin, Romero, Bishiop, Lochman and Williams2018; Lochman, Dishion, et al., Reference Lochman, Dishion, Boxmeyer, Powell and Qu2017).

Group therapists who handle difficult interpersonal provocations from their child clients by managing their expression of their own frustration and by effectively regulating their arousal are modeling key processes for children's own emotional regulation (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Christner, Freeman, Christner, Stewart and Freeman2007). In a related way, in a separate study, we have found that therapists who have more agreeable personality traits can implement Coping Power with greater quality of implementation and tend to be more likely to sustain their use of the program over time (Lochman, Powell, et al., Reference Lochman, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu, Wells and Windle2009, Reference Lochman, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu, Sallee, Wells and Windle2015). Therapists with an agreeable personality trait may find it easier to respond in relatively automatic, flexible, self-regulated ways, and to thus implement group cognitive-behavioral intervention in qualitatively better ways (Lochman, Powell, et al., Reference Lochman, Powell, Boxmeyer, Qu, Wells and Windle2009). Therapists with poor clinical skills and a nonagreeable personality style may also have difficulty in other aspects of their interpersonal relations and attachment to others. Muratori, Polidori, et al. (Reference Muratori, Polidori, Chiodo, Dovigo, Mascarucci, Milone and Lochman2017) found that therapists who had an anxious, preoccupied attachment style had child clients, who had received Coping Power group intervention in community hospitals, who increased in their aggression over time, in contrast to children who had received Coping Power from therapists who had a secure attachment style. A therapist with an anxious attachment style that involves excessive preoccupation with relationships may tend to intervene anxiously with a difficult child in their group, modeling poor regulation of their own arousal. Therapists with an insecure attachment style also may fail to challenge their clients’ usual interpersonal strategies (Dozier, Cue, & Barnett, Reference Dozier, Cue and Barnett1994). As children's frustration tolerance and self-regulation abilities develop due to their modeling of the group leader's management of their own emotional arousal, they may be less prone to act out.

Group leaders who respond more frequently in warm ways to the children in their groups are likely providing more social reinforcement for positive child behaviors within the group and for sustained improvement in reducing covert and overt problem behaviors outside of the group sessions. The group leader's social reinforcement value can be enhanced if children perceive the warm group leader in progressively more positive ways. Children who display high levels of oppositional behaviors have been found to have less positive and involved parents (Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, Lengua, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, Reference Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon and Lengua2000), and they may be especially likely to respond to warm, reinforcing group leaders.

Group leaders who respond to children with more warmth are likely to develop stronger therapeutic alliances with the children, and children who are thus more engaged in the intervention can learn the social-emotional skills more deeply and can display fewer problematic behaviors within the group sessions from the outset (Ellis, Lindsey, Barker, Boxmeyer, & Lochman, Reference Ellis, Lindsey, Barker, Boxmeyer and Lochman2013). Children's higher levels of engagement in Coping Power have led to greater reductions in children's externalizing behaviors over time (Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, Romanelli, Ellis, Barker, Boxmeyer and Lochmanin press).