The Bagas have no king; each village is governed by the oldest of the inhabitants, who settles their disputes…They are a jovial people, and fond of drinking…The Baga never visit their neighbors, neither have they occasion to do so, for their own country produces abundance of everything requisite for the subsistence of any really temperate man. They cannot imagine that any nation is better off, and believe themselves superior in every respect to all others. I could not gain any information as to their ideas of the Deity…they make gods of anything that comes into their hands…Footnote 1

Ethnohistories of the Baga and Temne peoples of the Atlantic coast of Guinea and northern Sierra Leone recount a journey from the Fouta Djallon mountains in Guinée Moyenne, where they were pushed out by larger hegemonic forces, westward toward the coast where they now reside. Though they are now hundreds of miles apart, these two linguistically related peoples are very much aware of each other. The Temne are a large, politically powerful group, occupying most of the northern half of Sierra Leone, with legendary conquerors, kings, and kingdoms, as well as historically large towns, one of which became the foundation for the capital city of Freetown. The Baga occupy only a thin slice of the coastal wetlands of northern Guinea, pushed against the sea, and number approximately 40,000 over five separate dialect groups. Traditionally acephalous, disunified, marooned, and, until recently, politically invisible, they live in small, isolated villages. But they occupy a place of mystique in Temne constructions of identity, and they know that they are quite a special people, as Réné Caillié observed, above, in 1830.

Along the coast of the Republic of Guinea the term Baga has been used to cover almost everyone and everything, even if much of the material culture and art is actually from other distinct groups, even linguistically unrelated groups who happen to live along the same coast. Some of these groups have been historically much more important in the political and economic spheres of the region, yet the term Baga is preeminent on the art market as having a certain cachet. Part of the problem stems from the local use of the term Baga to designate almost any group of isolated peoples, maroon groups, or “bush people” (as many Africans say), regardless of what they may call themselves or their languages. And that practice may not be unfounded linguistically.

This essay is an attempt to untangle the etymology of ethnic labels applied to the peoples of this region, based upon an understanding of the Baga and Temne languages. It considers the written history and the ethnohistories of the interaction of these two closely related peoples, their structure of kinship, the evolution of contemporary ethnicity and constructs of ancestral lineage in oral narrative, and, particularly, the ancient political construct of inherited rights versus the assumption of rights by seizure, “older brother” versus “younger brother,” and the dialectic between the metropole and the periphery.

The Broad Cultural and Linguistic Configurations in the Region

By way of situating the Baga and Temne within the larger context of the region formerly known to European mariners as the “Upper Guinea Coast,” the westernmost Atlantic coast of Africa, it should be noted that it is a region of a few very large linguistic groups and many extremely small groups, between which there is little correlation or history. The term “West Atlantic,” now simply “Atlantic,” was coined first in the nineteenth century simply to group together all the miscellaneous languages in this region, approximately 45, from Senegal to Liberia.Footnote 2 They are largely unrelated to each other except as Niger-Congo languages.Footnote 3 Most of them have noun-prefix structure, but not all, and this is simply a characteristic of Bantu languages in general; some have noun-suffix. Some are more tonal, some less. Most Atlantic languages exhibit consonant mutation, but this is a widespread characteristic of languages. Almost unique to some of these languages is a system of agreement or concordance between the noun and noun modifiers, pronouns, demonstratives, possessives, and sometimes the verb, which is most pronounced among the Baga and Temne, with approximately twenty noun classes. The northern, central, and southern groups of Atlantic are quite distinct.Footnote 4 They share almost no vocabulary except for a very few loan words. Some, such as Bijago or Limba, are quite isolated from the others. But they cannot be left hanging, so the term “Atlantic” serves to put them in a regional grab-bag. It is a term of convenience but of very little use linguistically, and the place of Baga and Temne in it is disputed.Footnote 5

It may be suggested that the distinction between Baga/Temne and the rest of the Atlantic languages is a function of their distinct histories of movement and interconnections, as well as their ethnohistories of migration. The Baga and Temne have had little historical contact south-to-north along the Atlantic coast with the groups in Guinea Bissau, Senegal, and Gambia, and they continue to be largely oblivious to them, with the exception of the Balanta, who have recently infiltrated the Baga area. Their narratives of origin trace a migration from the Fouta Djallon in the northeast in minute detail, fleeing the incoming Fulbe probably over several centuries.Footnote 6 It is clear from cultural, political, sociological, and linguistic indicators that their ties are closer to the Maninka-speaking peoples of eastern Guinea and southwestern Mali on the upper reaches of the Niger River. Historical sources beginning in the sixteenth century bear this out.Footnote 7 Likewise, there has been little cultural exchange between the northern and southern Atlantic groups, but extensive and deep cultural exchange and influence from the East. A Temne aphorism declares, “It is the East that has power,” which is the foundation theory of all ritual, the direction from which all things flow, the place of birth, the location of the gardens, and the starting place for all ritual processions.Footnote 8

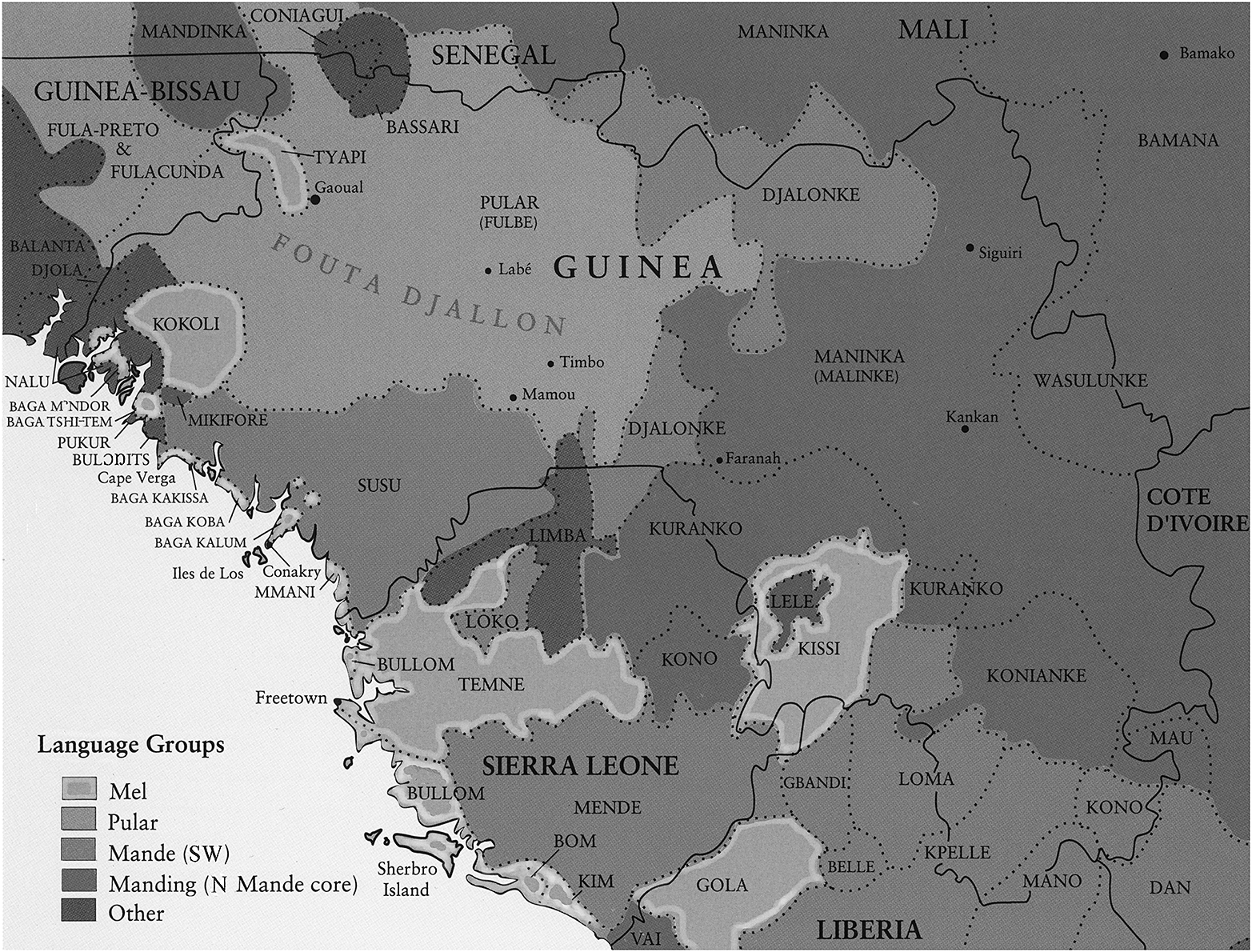

The large circle in question here includes the long semicircular shape of the country of Guinea, as well as Sierra Leone, which it almost completely surrounds (see Map 1), spreading through disparate geological, topological, and cultural zones. Haute Guinée in the Northeast is largely savanna, and is peopled principally by the Malinke (Manding language group, Maninka-speaking, the northern faction of the larger Mande language group), who extend deeply into neighboring Mali and southeastward into the Ivory Coast, and share their flanks with the closely related Mande groups of Kuranko, Konianke, and Ouassoulounke (Wasulunka), as well as the more distantly related Djalonke (Yalunka in Sierra Leone).Footnote 9

Map 1. Language groups of Guinea and Sierra Leone. Map created by the author.

To the far southeast, the inland Guinée Forestiére is occupied by the Kissi (closely related to the Bullom of the Sierra Leone coast) and Loma (Toma in French), both of whom spill over the borders into Sierra Leone and Liberia; the Kpelle (Guerzé in French) and Mano (Manon), who are found in large numbers in Liberia; and the eastern Kono (not to be confused with the Kono of Sierra Leone), extending into Ivory Coast. The Mende occupy most of the forested southern half of Sierra Leone.

Moyenne Guinée, a mountainous savanna, is occupied mainly by the Fulbe (Pular-speaking, called Peul by the French and Fula by the English) and their relatives, the Toucouleur, both of whom also extend broadly into the adjacent regions. They are here surrounded by and mixed with small populations of Badyaranke, Foulacounda, Coniagui, Bassari, Djakanke, and Djalonke extending northward into Senegal; and Limba, Djalonke, and Susu extending southward into Sierra Leone.

In the west, the area that most concerns us here, is Basse Guinée or Guinée Maritime, and the northern coast of Sierra Leone, where mixed forest and savanna is crossed by rivers and inlets from the sea, called marigots in French. This area, in Guinea, is dominated by the Susu (Soso),Footnote 10 but also includes a number of small groups such as the Djola (Yola) and Nalu (both extending into Guinea Bissau), the Baga and Kokoli (Landuma), which are both related closely to the Temne of Sierra Leone, and Mmani (or Mandenyi, called Bullom in Sierra Leone), and a few extremely small discrete groups seldom mentioned in surveys.Footnote 11

Linguistically, the circle of Guinea and Sierra Leone may be divided into three large language families (see the key to Map 1). Dialects of the Pular language are spoken by various groupings of Fulbe and the related Toucouleur in the northwest.Footnote 12 The Mande include the northern languages of the Manding (the nuclear group of Malinke, and satellite groups of Djakanke, Djola, Mikifore, Kuranko, Ouassoulounke, and Konianke), and a loosely connected group of languages that formerly were called “Peripheral Mande,” but are now called “Southern” or “Southwestern Mande,” including the almost identical Susu and Djalonke in the north of this region, and the closely-related Mende, Loma, Mano, and Kpelle in the south of this region.Footnote 13

The third group, the Mel-speaking peoples, are dispersed in small groups along the entire coast of Guinea (the Baga, Kokoli, and Mmani), along the entire coast of Sierra Leone (the Temne, Bullom, Bom, and Kim), far away on the border of Guinée Forestiére and eastern Sierra Leone (the Kissi), and, arguably, at the inland border of southern Sierra Leone and northern Liberia (Gola).Footnote 14 The dominant distinguishing feature is the extensive noun-class system using prefixes to designate a large range of categories (humans, animals, plants, inanimate objects, abstract ideas, liquids, size, loan words, etc.), the definite and indefinite, and singular and plural (for example, to use a now international word derived from the Baga and Temne: Coca Cola, from the “kola nut” = kola (sing.), tola (pl).)Footnote 15 Dalby chose the term “Mel,” in 1965 as the common word for “tongue,” with regional variations.Footnote 16

On the fringes of the Mel lie a number of small, completely unrelated language groups, the Limba, Nalu, Pukur, Bɔlɔŋits, Bassari, and Coniagui (see Map 1). Nearly all these groups have some connection to Baga political history, ethnography, and cultural history.

From the fifteenth century, Portuguese and other European trading networks began to change the cultural face of the coastal region, introducing the competing force of Christianity along with new economic and cultural alliances. Portuguese traders lived among the coastal peoples, intermarrying with them and adopting local customs. Their legacy remains in linguistic and material continuities. They also wrote many descriptions of the ritual and artistic aspects of the Mel peoples, of which one of the most detailed is that of Manuel Álvares, corresponding closely to ritual and art existing up to the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 17

Significant differences characterize the cultural spheres from the twentieth century onwards, sometimes seen between distinct ethnic groups, but more often occurring from region to region across ethnic lines. Earlier studies of African art tended to group styles of art according to ethnic boundaries, assigning to each ethnic group a definitive style – “One Tribe, One Style” – from which all departures were viewed as substyles of the given ethnic group, or lesser-quality idiosyncrasies.Footnote 18 This was a new and valuable approach, at the time, as a way of classifying the great mass of objects that lay in museum storehouses without provenance or adequate attribution. Most scholars in the field now agree that such classification is misleading and that styles tend rather to develop around particular artists and their workshops, some of whom attract a large regional following, and others not. Often this following adheres to ethnic clusters, but in other cases it may be cross-ethnic and international, and may not even be universal within any one ethnic group. The culture clusters described here are identified by their dominant ethnic designation, with the caveat given above.

The Atlantic maritime region in the west coast of Guinea is home to traditions that are generally attributed simply to the Baga who range along the coast. But a number of small groups adhere to some central “Baga” cultural principles, and can be included with the Baga in a ritual cluster: the Nalu in the north, the Kokoli (Landuma) somewhat inland, Pukur, and Bɔlɔŋits.Footnote 19 Like the distant forest peoples, these coastal peoples have created some face masks with costumes, but they have concentrated more upon large-scale wooden headdresses often weighing up to 100 pounds. These include several different types of horizontal composite-animal masks, some immense vertical superstructures such as D’mba (the huge female bust), Banda (the horizontal mask with a crocodile jaw), a-Mansho-ŋa-Tshol (the Serpent), and a great many types of female busts carried on top of the head in dance, in general characterized by brightly colored patterns. The aesthetic here leans toward a form of rather naturalistic figural sculpture characterized by large bulging eyes and a long aquiline nose, traits which may be traced through their large corpus of art in other styles. Monumental figurative drums are also important. These traditions never extended very far inland, and were shared by isolated coastal villages, serving (among other purposes) as the principal means of seeking social and political cohesion.

The Baga Groups

Various small ethnic groups occupy the narrow stretch of lowland along the Atlantic coast of the Republic of Guinea. Villages are fairly well isolated from each other by marshes and inlets from the sea, which both impede and facilitate transportation. This isolation increases in the rainy season, when travel along footpaths and roads becomes extremely difficult (virtually impossible for a foreigner, although the Baga do trudge through the mud on the footpaths).

The distinct peoples who identify purely as Baga are the most prominent of these groups, and they range along the coast from the Kalum Peninsula at Conakry northward to the Rio Componi just south of the border of Guinea Bissau. They are comprised of five distinct dialect groups (in order from north to south): the M’ndor (Mandori), tshi-Tem (Sitem/Sitemu), Kakissa (or Sobane), Koba, and Kalum.Footnote 20 These groups, together with the Kokoli of inland Basse Guinée and the Temne of Sierra Leone, form the “Temne language cluster.”Footnote 21

Cultural groupings somewhat overlap but are distinct from the linguistic groupings. Geographically contiguous with Baga are the Nalu (separating the two northern Baga groups), the Pukur (commonly called Baga Mboteni or Baga Binari), and the Bɔlɔŋits (previously known as Baga Foré – literally “the Black or Wild Baga”), the latter two separating the Baga tshi-Tem from the Baga Kakissa to the south. These are separate single linguistic units vaguely related to each other but not to the Baga and Kokoli, with which they share, nevertheless, much of a common culture.Footnote 22 What we know as the art of the Baga derives from all these groups, and is itself divided into many different linked cultural traditions. Though linguists sharply separate the Pukur and the Bɔlɔŋits from the Baga, the people of these groups, in my experience, rather ignore the linguistic distinctions, and consider themselves to be one unified cultural group with the Baga tshi-Tem.Footnote 23 Language difference is a minor inconvenience: the Pukur, who number only two very small villages, learn to speak, from infancy, Pukur, Baga tshi-Tem, and Susu (as well as French, in school), so they were sometimes puzzled by my attempt to differentiate them from their Baga tshi-Tem neighbors.Footnote 24 The Baga tshi-Tem are largely endogamous, and this further highlights the relationship between these three unrelated language groups, as the Pukur and Bɔlɔŋits are included in this endogamous scheme, but the Susu living in the same circle are not, nor are the other four Baga dialect groups.

The territory of this larger cultural grouping is now quite infiltrated by peoples from the East who speak Mande languages: the Susu (Southwestern Mande), the Mikifore, and Maninka/Malinke (both northern Manding), as well as by the Pular-speaking peoples, the Fulbe/Peul/Fula. The Mande peoples, in particular, have had a profound historical influence on Baga culture.Footnote 25 Susu and Fulbe immigration to the coastal regions has continued through the twentieth century. The Susu now really control what was once the larger Baga territory, in which the few extant Baga villages are now simple insular ethnic pockets. Susu is the language of preference throughout Bagaland, except among elders in the two northernmost Baga dialect regions, because it enables them to participate in the market system controlled by the Susu, and in the greater national dialogue. Baga villages today have no markets of their own, and all markets in the region are organized by the Susu, by which Susu has become the lingua franca of the entire coast. I have described this process as the “Susuization” of the Baga. More recently, however, since the 1980s, one continuing result of what seemed to be a renaissance among the Baga tshi-Tem is that the tshi-Tem youth speak almost exclusively Baga tshi-Tem among themselves in the villages, and it is a point of pride. Today, only the tshi-Tem and M’ndor speak Baga regularly, and the Koba mostly know their Baga dialect but generally speak Susu, while the central and southernmost groups (Kakissa and Kalum) have been almost completely assimilated to the Susu for more than a century in every way. Nevertheless, it seems that every report from the southernmost groups repeatedly contains the hopeful note that “one old woman was found to still speak the language.” And when I returned to search for what was the village of Kaporo in 2008, now almost overwhelmed amongst the clutter of expanding Conakry, I discovered the existence of a pre-Islamic shrine so sacred and so secret that no one would permit even an interview on the subject. Never say “die” and never say “the last of…”

The Baga, Temne, and Kokoli trace their origin, through numerous oral traditions, to the highlands of the Fouta Djallon in the interior of Guinea.Footnote 26 At some point (Baga traditions suggest the eighteenth century, but written history suggests sometime before the fifteenth century) the Fulbe entered from the north and spread throughout the Fouta Djallon.Footnote 27 At this point, an Islamic Fulbe aristocracy developed with contact there with the already Islamic Djalonke and Malinke. The Baga say they were driven out because of their refusal to convert to Islam, because of the superior weaponry of the Fulbe, and the incompatibility of their settled farming life with the itinerant and destructive cattle herding of the Fulbe (a conflict that continues to this day).Footnote 28

The earliest sources speak of the Baga and Kokoli in the context of a larger group, called Sapi, consisting also of the Temne and Bullom. These were said to have been united into a loose cultural confederation, according to André Donelha, “in the same way that in Spain various nations are called ‘Spaniards,’” although it is unlikely that they formed a solid political entity.Footnote 29 The earliest record of the name, Sapi, appears on the Cantino Planisphere of 1502.Footnote 30 A similar designation, Sapi (sing. Tyapi), is used by the Fulbe and others of the Fouta Djallon to designate the Kokoli, especially in the region of Gaoual in northern Guinea, into the twenty-first century (see Map 1).Footnote 31 By 1506, the name Temne was specified by both Fernandes and Pacheco Pereira.Footnote 32 Subsequent reports included also linguistically unrelated peoples in the same area such as the Limba, Djalonke, Susu, and Loko. Several other groups, unknown today, appear also in these early ethnic inventories, such as the Itale, Peli Coya, Taguncho, and Putaze.Footnote 33 It was said by Andre d’Almada, in 1594, that all of these groups understood each other, but perhaps this referred to multilingualism, as we see today. The territory of the Sapi was given variously at different times, but in the first half of the sixteenth century they were known to extend along the coast from the Rio Nunez in northern Guinea to Cape Verga in central Guinea, to present day Vai territory in the south of Sierra Leone, and inland approximately one hundred kilometers.Footnote 34

The final waves of Baga and Temne migration from the Fouta Djallon must have come by 1725 when the last remnants were defeated at Mamou, together with the remaining non-Muslim Fulbe, by the Islamic Fulbe elite. The Baga who fled at this time seem to have joined communities of Baga already in place on the coast, and this has led to a complex structure of migration ethnohistory and a resulting political stratification based upon claims of priority.

European contact that began in the fifteenth century with the Portuguese (whose vocabulary appears prominently in the Baga and Temne languages today) continued to one extent or another through the twentieth century, bringing the French, English, Belgians, Germans, and Americans (especially African Americans) at various points and times. The French transformed the Baga political system.Footnote 35 Baga society had always been quite thoroughly decentralized and acephalous throughout its recorded history. There has never been a recognized leader of all Baga peoples, or even a pre-eminant regional chief.Footnote 36 Chieftaincy itself is a foreign institution, at least for the Baga tshi-Tem. Under French colonial rule, chiefs were selected to reign over villages, and districts were set up under the control of particular chiefs who were cooperative with the colonial government. But these district chiefs were generally non-Baga (usually Nalu) and received only grudging allegiance from the Baga. Village chiefs derived their power only from the French government at Conakry and not from the people, who, until the crushing repression of the independent government since the 1950’s, continued to rely principally upon the governance of the society of male clan elders. At independence there was a movement to eradicate the system of village chiefs, but the system continues today as a convenience to the national chain of command, and the title is now Président du District.

The Origin of the Ethnonym and the Place of the Younger Brother

To understand who the Baga are and why they are so intensely in love with their unique masquerades, it is important to know something of their origins, which have been vastly misconstrued by writers throughout the colonial period right up to the present. The ethnonym, Baga is of huge importance. The first step in understanding the significance of the ethnonym is to pronounce it correctly: the five Baga dialects do not pronounce their name as “Baga,” but rather “Baka,” with a guttural “k.”Footnote 37

Many different sources have been suggested for the term Baga, but they have been mired in not only the persistent filtering of information through the neighboring Susu observers, but also by a lack of understanding of the nature of etymology, and by a lack of depth in the larger Temne language cluster, to which Baga belongs. The etymology of the term Baga is extremely complex, but too often, facile answers have been offered. Because I spoke Temne for eighteen years prior to going to Guinea to work with the Baga, I was very much aware of not only how the Temne see their relatives, the Baga, but also how they have named them. Ethnic names throughout the world historically have generally been given to a group not by themselves but by their neighbors, and this is certainly true of the Baga.

Throughout the Temne language group, there are certain appellations that appear in slightly different forms depending upon context and are spelled differently by different writers, either because writers hear the word differently or because it is spoken differently by different speakers. One of these key words is the term tem, pronounced as them. Footnote 38 This signifies “elder man,” or “gentleman,” used also as a term of address somewhat equivalent to “Sir.” Thembra is “elder woman.”

The Temne and Baga share a concept of social construction found throughout this region of West Africa, especially studied intensely among the Mande groups, consisting of the binary of “older brother–younger brother.”Footnote 39 The term “older brother” signifies deeper ethnohistory of origins, earlier arrival, prior domain, higher political status, and prerogatives of inheritance, while “younger brother” signifies more recent arrival in the oral narratives, lower political status, and lesser claims to inheritance. In the Temne language cluster, this is reflected in the ethnonym Temne (properly pronounced “Themnε”).Footnote 40 In Baga tshi-Tem, themnɛ means simply “to be old” (as in ɔn themnɛ = “He’s old”), and it likely that the Temne were called this by their Baga relatives, who regarded them as the “elder” faction (and largest group) of the Temne-Baga group. The missionary Christian Schlenker came close when he tentatively translated “Temne” as “the elders themselves.”Footnote 41 Elder/younger, of course, is situational (I am younger than my older brother, but older than my younger brother), and other ethnonyms among the Baga reinforce the meaning of them: Katema (“that of the elders” or “the area belonging to the elders”), the territory of the Baga Koba subgroup; and tshi-Tem (Sitem), signifying “the language of the elders,” a northern dialect group of the Baga.Footnote 42

Recent anthropologists, historians, and even linguists have resurrected an old amateur etymology for the term Baga.Footnote 43 It was first raised by Georges Paroisse, the French Chargé de mission en Guinée just prior to the establishment of the colony, who suggested a Susu derivation meaning “people (ka) of the sea (ba).”Footnote 44 This has been perpetuated throughout the literature ever since, and seems never to end (thus the present essay). It is simply too facile. Here is an excellent example of why one cannot simply go to a dictionary in a foreign language, especially in a language that one does not speak, and pick out words that sound like the syllables in the term in question.

There are several reasons why this etymology is faulty. First, the Baga were already noted on the coast in 1594 by Almada, and their presence was implied even earlier, in 1506–1508, under the term Sapi. Meanwhile, the Susu were still quite far inland until the sixteenth century, as documented by the Portuguese.Footnote 45 It is unlikely that the earliest Portuguese visitors had much contact with the Susu of the interior or that the Baga themselves would have been using a Susu appellation at that early date. Second, the Baga oral narratives trace their origins to the highlands of the Fouta Djallon, and therefore they think of themselves not as a people of the sea but a people of the highlands. Third, the Baga are not a people of the sea even today – they rarely even venture to the seaside either to swim or to fish, even where it is only a short walk across the rice fields. They distrust the sea, and call the shore ku-lum, “wasteland.”Footnote 46 They are a people of the swamplands, of the rice fields, a fact the Susu well know, because it is largely the Susu who fish on the sea off the Baga coast.Footnote 47 In Susu or any other language, “people of the sea” would mean people actually living on or in the water, not those living on the coastal mainland. Ba in Susu refers to the sea, not the seaside, which is dɛ.

But the fourth and most compelling reason this etymology is erroneous is that ba ka is not a Susu construction and would not make sense to a Susu speaker. Rather they would say mikhie nakhee kelikhi ba kote ma, literally “people who come from the coast” – or “beside the sea,” according to Grant H. Moore, who studied the Susu language from 1952 to 1960 and did Susu translation in Guinea for the Federation of Missions (e-mail communication, 2009). “Perhaps one could extrapolate ‘ba’ meaning sea and ‘ka’ as inhabitant – but it seems to me to be a bit of a stretch,” he adds. Literally, “people of the sea” in Susu would be ba ma mikhie, although this would be an ambiguous term with little meaning (Does it mean “people living on the sea,” “people living at the sea/by the sea?”). So the etymology that seems most obvious is simply too easy, and cannot be supported by in-depth linguistic study.

Moore continues, “The Temne people of Sierra Leone have the same root language; their similarities with Baga are most striking not only with respect to vocabulary but the tonality is almost identical. They might be able to shed some light on the true meaning or origin of Baga or Baka.” In fact, to the Temne, during my stays among them from 1967 to 1980, the origin of the word Baga was explicitly clear, although it is very complex and not easy to explain to the outsider. Bear with me while I navigate the maze of linguistic roots/routes that resemble the marigots zig-zagging and crisscrossing Baga and Temne coastal territory.

Both Baga and Temne are terms within the larger Temne language cluster, in which the two languages are not inter-intelligible, but even the distant Baga dialect, Baga tshi-Tem, shares 85 of Swadesh’s 100 key words of language with Temne, with varying pronunciations.Footnote 48 The southernmost Baga dialects, Koba and Kalum, are said by Voeltz to be closer to the Temne than they are to the Baga tshi-Tem.Footnote 49 The names by which they are known can be seen as sharing binary positions that define each other in a hermeneutic way. The Baga and Temne have named each other.

At the beginning of the twentieth century it was reported that in the tradition of the Kokoli (also of the Temne language cluster, and neighbors of the Baga), the Temne were referred to as the “elder brother.”Footnote 50 The Temne are the largest group within the Temne language cluster, numbering almost three million today, as compared to fewer than 40,000 Baga throughout the five dialect groups. In the centuries before the colonial period, they were known for their military strength, as a highly centralized and well-established people with powerful kings. They fit the pattern of the “elder brother,” and their relatives, the Baga and Kokoli, would certainly have seen the Temne kingdoms as the metropole.

Outlying areas of the Temne, and those who inhabited them, were frequently labeled Baka by the Temne. The word has a sense of a “settlement,” and, by extension, the “settlers” – literally it translates as “to have of (ba ka)” or, by extension, “to seize” or “to occupy.”Footnote 51 Wilderness that has been reclaimed and settled with villages is baka, and the people who settle them are the am-Baka, “those who have seized (the land).” Thus, the Temne to the far north in Kambia District, in a narrow stretch somewhat isolated from the Temne heartland, call themselves the Baga Temne. There are at least six Temne villages located on the colonial maps of Sierra Leone bearing the name Baga or Baka, and I received my information on the meaning of the term in one of these villages. Both the Baga and the Temne would prefix the term to indicate the Baga village or the Baga land (da-Baka or ro-Baka – “the place of the Baga”), the Baga people (a-Baka or am-Baka), Baga territory (ka-Baka – “that of the Baga” – in both languages), or the language of the Baga (kə-Baka or tshə-Baka). Sometimes these villages and territories were “seized” from the wilderness; in other cases they were “seized” from previous occupants, sometimes for payment of a debt. In 1913, the Aku (Freetown Yoruba) writer Esu Biyi said that the Baga (probably referring to the Kalum) were known as the “fugitive Têmnés” who had been expelled by a sixteenth-century Bai Farəm, or Temne king, from an inland territory across the border of present-day Sierra Leone (where they had, in fact, been located by the Jesuit priest, Baltazar Barreira, in 1606).Footnote 52 Henry Usher Hall was told continually by his Southern Bullom consultants about “Baga” settlers in their territory who appear to have been Temne in fact, judging by the descriptions of the ritual they introduced to the Bullom.Footnote 53 So the word Baga – pronounced “Baka” (with a guttural “k”) – can be translated as “the settlers” or “the pioneers.” The etymology becomes a little more complicated as an indication of status, as it can refer to lower-status, remote members of the same culture (in the same sense as the Geechee living on the southern swamp islands off South Carolina and Georgia were denigrated by other African Americans). The Baga, especially the Kakissa, were particularly singled out in a (self-servingly ethnocentric) report by the French Catholic missionaries in 1898 as toute primitive. Footnote 54 And the term can refer to an enslaved person (wuni baka, “seized person”). Robert Clarke, in 1843, referred rather unkindly to the “Baga people, a bastard kind of Temne,” in the sense of a kind of illegitimacy – in contrast to the established Temne people – “often brought here [to Freetown] as slaves.”Footnote 55 Thus, the term Baga functions in the social dialectic as a reference to the disenfranchised “younger brother.”

These power relationships are rarely discussed by the Baga, and one does not mention the foreign origins of some of the clans, nor any of the status relationships, in public. Obviously, the implications of the name Baga are not always something that the Baga themselves would want to accept. The Baga are extremely reluctant to discuss kinship and social structure, which is often based upon historical inequities and condescension, as well as rejection and acceptance with reservation. These factors may be what was behind the conversation that Ramon Sarró had in 1993 with a knowledgeable consultant on Baga history. Sarró saw the exchange perhaps as a rebuff, but more as an “example of the interactive nature of secrecy” and “part of a strategy to create a mystique”:

‘Ah, you are the anthropologist, I’ve heard about you. I feel sorry for you. You came here to obtain information, but Baga are very secretive and you will not get away with it. For instance: have you already learnt what the word baga means?’

‘No,’ I answered, stung by the realization that I had never given any thought to the etymology or meaning of baga.

‘Well, you will never do,’ he said, and walked away.Footnote 56

But as is always the case with binary categories, their attributes are situationally adjustable, as mentioned above. “Younger brother” often has powers of his own, and this is often true of societies that are politically of lower status.Footnote 57 In my experience with the Temne, their common view of the Baga positions the Baga as powerful spiritually, even feared for their access to supernatural forces. The Temne may have been seen by the Baga and Kokoli as landed gentry in the material world, but they saw the Baga as the magical masters of the otherworld. Indeed, the Baga are much better known than the Temne in the realm of the arts of mystical representation.

Conclusions

It has been my attempt here to elucidate the complexity of “ethnic,” linguistic, and cultural identities, in which the members of any group identify in a great number of ways that may seem contradictory and confusing to the outsider. European obsessions with taxonomy have obscured this complexity and made it simple, if misleading. Several linguistically unrelated groups identify as “Baga,” and they do so not only because of cultural ties, but because of their history fleeing oppression and their current status as “maroons.” Ironically, they have forged these relationships despite considerable physical isolation from each other. In a sense, they are all truly “Baga.”

Because they are most often given by others, ethnic names are frequently not flattering. Indeed, they are often meant to self-aggrandize or to demean others. In the case of the Temne, if they were given this name by the Baga and Kokoli, it was apparently a token of esteem and an acknowledgement of the established order of hierarchy and rights. It is also quite apparent that the Baga enjoy and celebrate their own status as the owners of the mystical domain, with their wealth of ritual art representing the spiritual world.

The differentiation in status assumed by the Temne and the Baga through their names is reflected in cultural conventions. The Baga own the ancestral spirits and spirits of the forest, with their towering masquerades manifesting the original guiding avian spirit, a-Mantsho-ŋo-Pɔn, who led them from the Fouta to the coast; their giant serpent headdress, a-Mantsho-ŋa-Tshol, who may relate to Manding “founding python” narratives; the very representation of the creator God and creative powers, a-Tshol, perhaps unique in Africa; female spirits of enticement for the old men and the young men called Yombofissa, Signal, and Tiyambo; and Sibondel, the devious hare who undercuts political authority.Footnote 58 The Temne, on the other hand, are better known for their royal brass masks (ɛ-Rɔŋ-ra-Bai), and the masks of Keita ruling families (ɛ-Rɔŋ-ɛ-Thoma) from Manding.Footnote 59 They have very few masks representing common ancestors or spirits of the forest, and of those, the majority are borrowed from the Mende or Bullom, such as a-Nɔwo of the women’s Bondo association, Pa Kashi of the men’s Pɔrɔ association, and Gɔngoli, the antisocial mask.Footnote 60 Others are imported from the Krio of Freetown.

In the initiation of boys into adulthood, the Temne initiates in ra-bai-da-themnɛ (“that of the Temne king”) returned to the village for their coming-out ceremonies at the end of three or four months in the sacred forest grove as “princes,” dressed in their fine embroidered indigo gowns, turbans wrapped around their heads, holding elaborately carved staffs as they marched in procession into the village.Footnote 61 Baga male initiates, on the other hand, in the final ceremonies of ka-kǝntsh, were mercilessly beaten while running the gauntlet to greet the terrifying highest male spirit (a-Mantsho-ŋo-Pɔn), and entered the village with their heads covered in a simulated conical fish trap (kə-mbakəla), and wearing only a short skirt made of stripped date-palm leaves (yɔma).Footnote 62

I do not mean to suggest that the dyads of younger brother–older brother were entirely fixed and immutable, with a one-to-one correspondence permeating all areas of Baga-Temne life, as one could point to many noble characteristics of the Baga, some of whom have reached high social status (the first lady of Guinea, 1984–2008, for example), and less-noble aspects of the Temne, most of whom live very ordinary, if not financially insecure lives as subsistence farmers and fishermen. But there remain some elements that seem to correspond to the historical significance of their names.

To be “younger brother” or “older brother” carries wide implications and deep responsibilities. One cannot know the one without knowing the other. One term does not exist without the other. One cannot know the Baga or the Temne people without understanding the words.Footnote 63 This is why it is so important for the researcher to know the language of their people of study, and, as much as possible, to interview in the indigenous language, to write a transcription of the interviews in that language, and then to translate into the researcher’s own language. Errors come when the interviews are conducted in a lingua franca, such as Susu, or in the national language, such as French or English, as each language is embedded in its own cultural context. When I speak in French, I think in French; when I speak in Susu, I think in Susu.

The errors of the past occurred because of an ignorance of the history and ethnohistory of Baga and Temne origins, their interaction, and their linguistic relationship. Without my knowledge of the Temne, their history, and their language, I would not have known the significance of the Baga ethnonym.Footnote 64