Introduction

Acquired defects of the face usually follow trauma or surgical excision of a skin tumour. The surgical treatment strategy is based on the principles of: replacing aesthetic subunits so that flaps and grafts meet where the contour of the skin changes; using separate flaps for each aesthetic subunit; ensuring the complete removal of any tumour; maintaining awareness of the main systemic and local factors that influence healing; addressing the functional aspects of the nasal airway; and being mindful of the physiology of autograft acceptance and the psychological aspects of surgery.

In this paper, we describe the main techniques used to reconstruct complex facial defects, and the complications that can occur. Composite defects are defined as those involving two or more adjoining facial units.Reference Menick1 We also critically evaluate our own results to determine how improvements might be made.

The principle of aesthetic subunits

The face is divided into several regional units. These are the nose, forehead, eye, cheek, lips and chin.Reference Larrabee, Sherris, Murakami, Cupp, Hefferman, Larrabee, Sherris, Murakami, Cupp and Hefferman2 These units are further divided into aesthetic subunits. Gonzalez-Ulloa et al. first described the facial aesthetic subunits.Reference Gonzalez-Ulloa, Castillo and Stevens3 Aesthetic subunits are segments of contour broken by a change in undulation, skin quality or shadow.Reference Menick4 Different facial regions have their own colours, textures, mobility and contour. Every region is distinguished from other regions by its quality, skin texture and pattern of hair growth.Reference Baker5 Scar placement along the border of the subunits can minimise visible alterations in contour and texture.

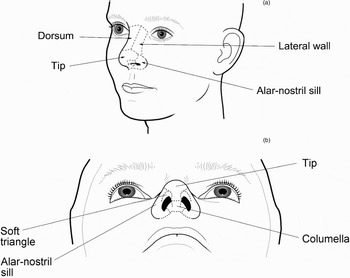

The nasal subunits comprise five convex and four concave units (Figure 1), i.e. the tip, dorsum, paired sidewalls, paired ala-nostril sills, soft triangles and columella.Reference Burget, Menick, Burget and Menick6 In order to obtain an optimum cosmetic result, Burget and Menick have advocated that the whole of the subunit is replaced in defects that involve more than half a subunit.Reference Burget, Menick, Burget and Menick6 More recently, Menick has suggested that the subunit principle should primarily be applied to central convex subunits.Reference Menick1 Menick points out that ‘trapdoor’ contraction occurs in the recipient bed of flaps and, if a convex subunit is replaced, the wound contraction that occurs around its periphery causes the flap to bulge, thereby creating a convex contour. Whilst a convex contour is desirable for the nasal tip and the alar subunit, it is not desirable for the sidewalls of the nose, where a graft may be more desirable as it is less likely to ‘pincushion’ than a flap.

Fig. 1 The aesthetic subunits of the nose.

Nasal defects may extend to adjacent facial units. The reconstruction of these facial units should ideally be done with a separate flap to maintain the segmental quality of the face.Reference Menick1 The cheek and forehead are peripheral units and are not as noticeable as those in the centre of the face, which is flat, expansive, of variable dimension and not so readily compared with the opposite side. In these units, the priority is to provide tissue of similar colour and texture. It is not necessary, and it is often impractical, to excise and replace the whole subunit of the cheek.Reference Larrabee, Sherris, Murakami, Cupp, Hefferman, Larrabee, Sherris, Murakami, Cupp and Hefferman2, Reference Menick4 Local and regional tissues are usually used to reconstruct defects of the cheek or forehead, although defects high on the forehead can be left to heal by secondary intention.

When there is a large defect involving more than one regional unit, reconstruction becomes more difficult, not only because the options for using local flaps are reduced, but also because the degree of fibrosis and contracture is less predictable. Using one big flap to reconstruct these defects will cross the borders between aesthetic units and will alter the contour of the face and require further surgery. This problem can be overcome by using a different flap for each unit. For example, when reconstructing large defects of the sidewall of the nose and the adjacent cheek, two flaps can be used and their junction placed along the nasofacial groove.Reference Tollefson, Murakami and Kriet7

In this paper, we describe our experience in reconstructing large defects of the face involving the nose, cheek, orbit and upper lip.

Principles of nasal reconstruction

A full thickness skin loss, especially of the nose, is ideally reconstructed with a vascularised inner and outer epithelial layer and a central scaffolding.Reference Danahey and Hilger8

Burget and Menick have proposed the following guidelines, based on their extensive experience: (1) rebuild or resurface the whole aesthetic subunit if more than 50 per cent of a unit is absent; (2) mirror the contralateral side; (3) design flaps and grafts to exactly fit the defect; and (4) flaps should meet at the junction of aesthetic subunits.Reference Burget, Menick, Burget and Menick9

Menick has recently qualified these principles as follows: (1) reconstruct units, not defects; (2) [be prepared to] alter the wound in site, size, shape and depth; (3) consider using separate grafts for each unit and subunit, if appropriate; (4) use ‘like’ tissue for ‘like’ tissue; (5) restore a stable platform; (6) build in stages; (7) use distant tissue for ‘invisible’ needs and local skin for resurfacing; (8) disregard old scars.Reference Menick1

Usually, whole aesthetic segments should be replaced if more than half of one segment has been lost, even if this means removing good tissue. This gives a more uniform appearance to each subunit.

Reconstruction requires the provision of an inner lining, an adequate scaffolding and an external lining with skin of the same thickness and colour as the contralateral side. The main exception to this is at the alar margin, where any reconstruction needs to be supported by a baton graft of cartilage.

These principles help to give uniform skin quality to each subunit, and also help to keep scars along the margins in order to help disguise their presence. Most texts advocate avoiding tension and ensuring an exact fit of tissue transposed into any defect, as excessive tissue contracts and ‘bunches up’ in an unsightly manner. Refining and thinning down contracted and fibrosed tissue is difficult and more likely to result in unpredictable scar tissue. When refinement is needed, particularly in the area of the alar groove, it is best to make an incision where a concave groove is required and to remove the nearby subcutaneous fat to contour the area. This method is preferable to raising the skin from an incision along the margin of the subunit, as this latter technique makes it is more difficult to reproducibly sculpt the fat. The incision in the alar groove and the scar it produces help to create a natural contour – hence Menick's advice to overcome both the surgeon's and the patient's fear of scars, as these will become barely discernable with time if they are placed where the contour of the tissue changes.Reference Menick1

The main factors that influence the planning of nasal reconstruction are: (1) the aetiology of the defect and the pathology of any tumour excised; (2) the presence of any previous radiotherapy or surgical scarring and the patient's status regarding smoking, diabetes mellitus and nutrition; (3) function; and (4) the patient's aesthetic needs and psychology.

Aetiology of the defect and pathology of any tumour excised

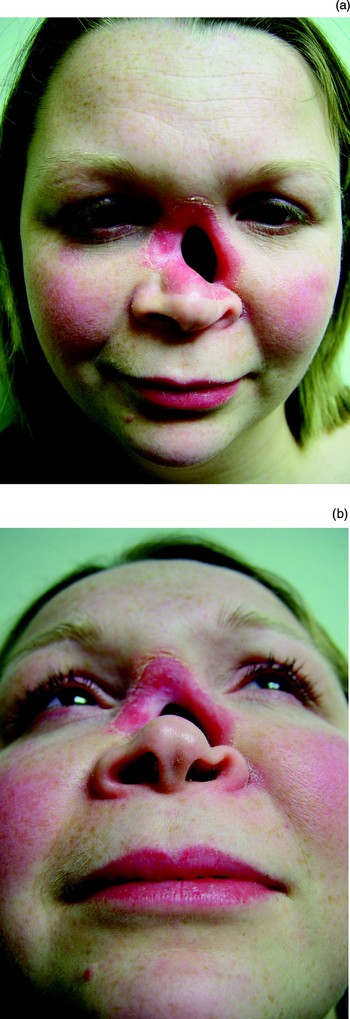

Before reconstruction, ensuring complete removal of any tumour is vital. Reconstruction should only be done when the surgeon is sure that the tumour has been completely removed. Moh's micrographic surgery should be used for morpheiform basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with unpredictable margins. These tumours have a propensity to spread unpredictably with wide, deep, finger-like extensions, sometimes along nerve fibres. The surgeon's eye is inadequate for judging the extent of the disease, and even using a wide margin of excision is unreliable (Figure 2). If Moh's micrographic surgery is not available, or the lesion is a SCC, or there is any doubt about the completeness of excision, then it is best to wait for the histological result from paraffin sections and to dress the wound in the meantime.

Fig. 2 (a) Before and (b) after excision of a morpheiform basal cell carcinoma, using Moh's micrographic surgery.

If the defect is due to the bite of animal or, particularly, a human, it is important not to reconstruct the nose until it has been debrided and cleaned regularly with dilute hydrogen peroxide and povidone–iodine solution. After several days, granulation tissue will form, but this is often a poor base to receive either a free or pedicled vascular graft. It is better to remove the granulation tissue and to start anew. Otherwise, there may be some retained organisms; in addition, the vascularity of the granulation tissue is not as beneficial to graft survival as the bleeding it produces on removal would suggest.

The vascularity of the host tissue is important for the survival of any free composite graft. If the vascularity is poor because of scar tissue or radiotherapy, any pedicled graft will contract and roll up on itself in an unsightly manner. Infection of any graft, whether it is split calvarial bone or conchal cartilage, is unusual. The exception is after an animal bite, in poorly controlled diabetics, or when there is dead space or haematoma formation.

Whilst most nodular BCCs can be excised with a 1–2 mm margin, this is not the case for a morpheiform BCC, as described above. Verrucous and well differentiated SCC with no invasion into the adjacent cartilage or bone can be excised with a 4–5 mm margin, reconstructed and then observed.Reference Dowley, Allibone and Jones10 In patients whose SCC is less well differentiated, it is usually best to give radiotherapy within six weeks of the excision.Reference Dowley, Allibone and Jones10

Healing and tissue viability

The viability of flaps is greatly reduced in heavy smokers and where there has been radiotherapy. In these patients, any flap must be thinned with care. It is better to leave the flaps thicker and to increase the depth of the defect where this is possible, but this should not involve removing the cartilaginous framework that supports the nose. Where the recipient site has had radiotherapy, it is worth considering removing tissue which has an endarteritis and replacing this tissue as well, otherwise the flap tends to contract on itself and barely gains any blood supply from its bed. This makes any further adjustment more difficult, as the tissue from the flap not only becomes firm and difficult to contour but its viability is severely compromised because of the poor vascular supply it receives from its bed. It is wise to place a tourniquet around the pedicle of a flap before dividing it in patients who are heavy smokers or where the recipient site has had radiotherapy, in order to check the degree of angiogenesis and to confirm that the flap will be viable without its feeding vessels.

Physiology

Reconstruction is done using flaps or grafts. Whilst flaps derive nutrition from their own blood supply, free grafts do not have a vascular pedicle. Grafts undergo three distinct but overlapping stages of healing, as follows.Reference Branham and Thomas11

Stage one is that of ‘plasma imbibition’. This stage begins at the time of graft placement and continues for the first 24 to 48 hours. Fluid is absorbed into the graft by capillary action, which draws the plasma into the graft itself. During this period, a fibrin deposit is being laid down between the graft and the recipient bed, which helps hold the graft in place. This process can easily be disturbed by the accumulation of clot or serum beneath the wound, separating the graft surface from the recipient bed.

Stage two of graft healing begins about 24 hours after placement of the graft. Vascular components from the recipient bed begin to meet randomly with vessels in the graft. At this stage, circulation is beginning within the graft.

Stage three includes vascular bud growth into the graft, developing a vascular network. A direct interface between the graft and the recipient bed is important, and this should be maintained during the first week.Reference Branham and Thomas11 Loose quilting may be necessary. Quilting should not be tight, as post-operative swelling can cause excessive tension and lead to pressure necrosis.

Function

The functional aspects of nasal reconstruction are often secondary to the patient's aesthetic needs, but they must not be neglected. Satisfactory functioning of the nose is determined by the nasal valve, the nasal inlet, the inner lining of the nose and its supporting cartilages.

The external nasal valve is made of the ala, the skin of the vestibule, the nasal sill and the contour of the medial crus of the lower lateral cartilage. Contrary to popular conceptions of nasal anatomy, the lateral crura of the alar cartilages do not extend to the margin of the ala. When reconstructing a full thickness defect of the alar margin, it is important to provide a baton of cartilage to run near the alar margin in order to avoid collapse of the nasal inlet. Dilator muscles are attached to the alar cartilages, and when they contract these help to flare or support the nostrils. The external nasal valve has a tendency to collapse at high flow rates even in normal individuals.Reference Shaida and Kenyon12 The upper lateral cartilages are in continuity with the superior ridge of the nasal septum. A valve-like mechanism exists at its distal end that regulates nasal airflow.Reference Wustrow and Kastenbauer13 The nasal valve area and internal nasal valve are two entities that should not be confused. The nasal valve area is the narrowest portion of the nasal passage and is bounded medially by the septum and the tuberculum of Zukercandle, superiorly and laterally by the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilages, its fibro-adipose attachment to the pyriform aperture, the anterior end of the inferior turbinate.Reference Kern14 The internal nasal valve, on the other hand, is the specific slit-like segment between the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage and the septum, and is measured in degrees and not as an area.Reference Sulsenti and Palma15 It normally ranges between 10 and 15°.Reference Thomas, Thomas and Roller16

The function of the internal nasal valve depends on the integrity and the attachment of the upper lateral cartilages, the alar cartilages, the mucosal surface of the nasal valve, the nasal septum and the intrinsic muscles of the nose.Reference Wustrow and Kastenbauer13 The main airflow resistance of the whole respiratory tract is normally confined to the internal nasal valve area. It is important to ensure that the septum and upper lateral cartilages are reconstructed with good quality cartilage in order to avoid collapse. As important is the need to avoid stenosis in this area; this is best avoided by replacing any defect of the lining with a vascularised septal flap or, alternatively, ensuring that a composite (skin and cartilage) graft is approximated to any overlying vascular flap on the blood supply of which it will depend.

Psychology

The psychology of nasal reconstruction deserves attention. The majority of patients who have a nasal tumour removed find the experience distressing. Whatever the patient's psychological profile, time spent addressing their fears and expectations will help them to adjust to their experience. Showing pictures of other patients with similar pre- and post-operative stages and results is important, in order to give some idea of what to expect, as well as to enable the patient to visualise what their appearance may be like at future stages. It is also useful if, before surgery, patients are able to see and talk to others who have had a similar experience. Some patients are curious to see the defect or pictures of it after they have undergone Moh's micrographic surgery, and this often helps them to accept the unusual appearance that they have whilst a pedicle is in place. Other patients do not want to see any pictures of their defect and may deny the process to varying degrees; these patients need more time, as well as careful and sensitive counselling, to help them to cope.

Surgical options

These are often used in combination to reconstruct composite nasal defects.

Nasolabial flap

This flap is suitable to correct skin loss of the alar subunit. It can be used as the outer lining when a full thickness defect of the alar subunit is being corrected. The flap can be based inferiorly or superiorly, and the pedicle divided at a second procedure (Figure 3). Alternatively, an island flap can be rotated into position.Reference Baker5, Reference Arden, Nawroz-Danish, Yoo, Meleca and Burio17 The perforating branches of the facial and angular arteries supply this flap. An island flap can be fed deep to its recipient site to allow primary closure (Figure 4). The bulk of the pedicle of an island nasolabial flap can fill out the nasolabial groove and cause some minor facial asymmetry, which can readily be reduced at a later date. A more medial defect will need a longer pedicle extending well down the nasolabial groove. If an island flap is used to replace the columella, it needs to be taken from low down along the nasolabial groove. Whilst an island or pedicled nasolabial flap can be used to replace the columella, such a flap is bulky and more stages will be needed to thin it down.

Fig. 3 A defect of the alar margin (a) is reconstructed using a nasolabial flap (b), the pedicle of which is divided at a second procedure (c).

Fig. 4 An island nasolabial flap is used to repair a defect of the right side of the nose. A free cartilage graft has also been used to support the repair.

Cheek advancement flap

If the defect extends onto the cheek, a cheek flap can be advanced and tailored so its edge matches the line where the contour of the nose abuts the cheek.Reference Tollefson, Murakami and Kriet7 One incision along the nasolabial crease may be enough, but sometimes another is needed in a relaxed skin tension line more than 0.5 cm away from the lower eyelid. The skin has a good subdermal plexus and can be raised above the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS). Elderly patients should be warned that they will have a lot of bruising. In order to obtain a groove around the alar margin, the nasolabial and cheek skin can be advanced a few millimetres more than might seem necessary and the rim left unsutured, so that when healing takes place the reconstructed ala contracts a little and rolls up to form a more natural edge (Figures 5 to 9).Reference Chait and Fayman18

Fig. 5 A defect overlapping the alar and cheek aesthetic units following Moh's micrographic surgery.

Fig. 6 A cheek advancement flap, used in the patient shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 7 Post-operative view of patient shown in Figure 5, showing blunting of the nasolabial groove and alar margin.

Fig. 8 (a) The area of fullness at the top of the nasolabial groove and at the alar margin needs to be contoured. (b) This is done by making an incision along the nasolabial groove and defatting the plump area. Note that the alar margin has not been sutured as scarring will cause it to contract and form a natural contour.

Fig. 9 Post-operative result for the patient shown in Figures 5 to 7.

Septal flaps

An anterior septal mucosal flap based on the septal branch of the superior labial artery (Figure 10), or alternatively a posterior flap based on the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery, can provide an internal lining. The flap will obstruct the nasal airway until it is divided at the second stage. A septal flap produces a well vascularised lining and reduces the likelihood of cicatrisation in this area, ensuring that any free cartilage graft at the alar margin will survive. It is important to raise these flaps under the mucoperichondrium to give them strength. After its pedicle is divided at the second stage, a raw donor site often still needs to re-epithelialise; this tends to cause crusting for a few weeks but will usually go on to provide a normal lining. One of the main limitations of using a septal flap is that if both nasal vestibules need an internal lining, a septal perforation may be produced. A posteriorly based septal flap can be used to provide a lining up to the area of the nasal valve if it is started very anteriorly, but it will not extend more distally. In this situation, the remainder of the internal lining is made by rolling the end of the thinned forehead flap around the margin; alternatively, a composite graft can be used, although this is less reliable.

Fig. 10 A left, anteriorly based septal flap rotated 150° to create the internal lining of the nasal valve area.

Regional and distant free flaps

When there are larger or more complicated defects including full thickness tissue loss, a free flap may be required. The free flaps previously described for total nasal reconstruction comprise the radial forearm free flap, the dorsalis pedis free flap and the retroauricular free flap. The radial forearm free flap is bulky, while the dorsalis pedis free flap is thin but causes significant donor site morbidity. The retroauricular free flap has very small vessels and therefore has a precarious vascular anastamosis, limiting its application. The use of free flaps has been described to produce the external surface in total nasal reconstruction, but they are bulky as the underlying fat is thick and difficult to thin evenly, even after several stages.Reference Walton, Burget and Beahm19, Reference Moore, Strome, Kasperbauer, Sherris and Manning20 Free vascularised flaps are best used for bulk and to re-establish a platform and an inner lining, as their colour does not match the skin of the faceReference Menick1 and their bulk and tendency to pincushion makes them less suitable for replacing the external surface.

Midline forehead flap

The reconstruction of large defects of the nose above the columella can be done with a midline forehead flap, but the use of such a flap for the columella itself is limited. This flap can be used for subunit repair, hemi-nasal reconstruction or total nasal reconstruction.Reference Day and Stucker21 The midline forehead flap is based on the rich anastamosis of branches that originate from the supratrochlear arteries,Reference Shumrick and Smith22 and consists of skin, subcutaneous tissue and frontalis muscle. A donor skin width of up to 4 cm has been described (we have used up to 6 cms width). The advantages of this flap are its excellent colour and texture match with the skin of the nose, its reliability, and the low morbidity at the donor site. The disadvantage is that the 180° twist in its base means that it has to extend to hair-bearing skin if it is to stretch near the columella without kinking its base. It is also unsightly until a subsequent procedure to divide the flap. If the pedicle is wide, it is worth replacing the skin of the pedicle at the second stage, in order to help reduce the size of any defect on the forehead and to obtain better alignment of the eyebrows. It is not necessary to repair any defect of the forehead skin if primary closure is not possible, as the appearance is better if it is left to heal by secondary intention. This means regular dressings will be required until it has re-epithelialised. It is important to keep any exposed periostium moist or it will not produce the granulation tissue required to fill the defect. If the outer cortex of the bone becomes exposed and osteitic, it can be drilled until bleeding cancellous bone is reached; this will then granulate afresh from its base. When the area of the forehead has re-epithelialised it will be red for several months, but this fades at around nine months.

Paramedian forehead flap

This is an improved modification of the midline forehead flap and is the best alternative for dealing with major nasal defects.Reference Shumrick and Smith22, Reference Menick23 The technique is very similar to that of the midline forehead flap, except that the flap is positioned to one side of the midline and is based on the ipsilateral supratrochlear artery (Figures 11 to 13). The paramedian forehead flap is not only robust but the donor site often heals well, even when it is not possible to close its upper part; this is left to heal by secondary intention. One of the main problems of this flap is its thickness, particularly if it is used to reconstruct the alar margin. It is possible to thin the skin of the distal 1.5 cm, unless there are factors affecting its vascularity. Ultrasound can be used to locate a feeding artery in the area of the supraorbital or supratrochlear artery, and if the flap is well defined it is possible to further narrow its pedicle (Figure 14). When an artery cannot be located by ultrasound, the flap still works well but it is necessary to use a slightly wider pedicle. It helps to use very sharp, curved scissors to cut off the required amount of fat. An assistant can grasp the fat with fine toothed forceps to place traction on the fat in order to lift it into the blades of the scissors. The main limiting factor in thinning the distal 1.5 cm of the flap is a history of heavy smoking, as the flap often becomes white. Leaving it for a few minutes may help it to bleed again; however, it is important to have not more than 0.3 cm of tissue with no bleeding, as this is more likely to crust and cicatrise.

Fig. 11 Pre-operative view of a dorsal nasal defect after Moh's micrographic surgery.

Fig. 12 The paramedian forehead flap used in the patient shown in Figure 11, shown just before its division during the second stage.

Fig. 13 Post-operative view of patient shown in Figure 11 after second stage.

Fig. 14 Use of ultrasound to locate the supraorbital artery. It is not always found, but when it is, the pedicle can be narrowed.

Free cartilage grafts

Cartilage from the septum, conchal bowl or rib provides a useful scaffold, and it is rare for it to resorb unless it is morselised or becomes infected. The scaffolding should be provided at the same time as the reconstruction (Figures 15 to 17). If the scaffolding is not provided in the first procedure, the soft tissue contracts causing difficulty in placing the scaffold at a later procedure.Reference Raghavan and Jones24 Menick has rightly emphasised that free cartilage and bone grafts should be placed before the wound matures; if they are placed at a later date, the fixed fibrosis of the soft tissue limits the surgeon's ability to remodel the contour of the soft tissue. Burget and Menick have advocated placing the cartilage between the frontalis muscle and the skin of a forehead flap before any contraction of the flap has occurred.Reference Burget, Menick, Burget and Menick25 However, it can only be placed distally, and this may compromise the distal vasculature. When alar subunits are reconstructed, the margin must be supported with a cartilage graft to avoid contracture. These grafts are kept between inner and external lining to provide a good vascular bed. When the defect does not involve the alar margin, the free cartilage graft has an important role in providing support by replacing any lost lower lateral cartilage, upper lateral cartilage or quadrangular cartilage.

Fig. 15 Pre-operative view after excision of a morpheiform basal cell carcinoma, leaving a full thickness defect at the right alar margin.

Fig. 16 In the patient shown in Figure 15, the lower lateral cartilage has been reconstructed with free conchal cartilage and a baton of cartilage has been placed along the alar margin. A septal flap has been used to create a vascularised internal lining.

Fig. 17 Post-operative view of patient shown in Figures 15 and 16.

Composite cartilage grafts

The free composite graft consists of skin and greater or lesser amounts of attached subcutaneous tissue. Konig first described the use of a composite cartilage graft from the ear.Reference Konig26 In 1943, Sir Harold Gilles described the use of the composite graft to provide the inner lining of a forehead flap used for nasal reconstruction.Reference Gillies27 The use of a free composite graft from the auricle for nasal reconstruction was reported by Limberg in 1935 and by Brown and Dupertuis in 1946.Reference Limberg28, Reference Brown, Cannon, Lischer, Davis, Moore and Murray29 The free auricular composite graft has been advocated for the repair of minor defects of the lower part of the nose, for the following reasons: (1) the skin of the ear is similar in colour to the skin of the nose; (2) the ear contains cartilage that gives good support, with a choice of contours to match those of the ala cartilages; and (3) the secondary defect of the ear is inconspicuous and can easily be repaired.Reference Dupertuis30

Composite grafts up to 2 cm in diameter can survive free transplantation where the vascular bed has not been compromised by smoking, radiotherapy, scar tissue from previous trauma or surgery, diabetes, or severe atherosclerosis. The shape of auricular composite grafts makes them suitable for use in nasal surgery.Reference Szlasak31 These grafts can be used to correct defects of the alar margin (Figure 18). Whilst its contour can often match that of the alar rim, an auricular composite graft can rarely replace a whole aesthetic unit, and its skin quality is often different.Reference Walter32 An auricular composite graft from the conchal bowl can be used for lining the inner surface of a paramedian forehead flap and to provide skeletal support to the reconstructed area (Figures 19 to 21).Reference Raghavan and Jones24 The donor site defect can be filled using a pedicled postauricular island flap (Figures 22 to 24). The conchal cartilage graft has benefits when combined with a paramedian forehead flap in reconstructing both nasal vestibules: it provides both the internal lining and support and thus reduces the likelihood of a septal perforation,Reference Park33 and it avoids nasal obstruction from the pedicle of a septal flap. In addition, the morbidity of the donor region is small.

Fig. 18 Post-traumatic notching of the alar margin (a), reconstructed with a free composite auricular graft (b).

Fig. 19 Views (a) before and (b) after resection of a squamous cell carcinoma.

Fig. 20 Pre-operative view of composite cartilage grafts positioned to provide an internal lining.

Fig. 21 Post-operative views of the patient shown in Figures 19 and 20 after the second stage of surgery, during which the pedicle of a large median forehead flap was divided.

Fig. 22 Taking a free composite conchal graft. The whole bowl can be taken as long as the antihelix is retained.

Fig. 23 (a) Marking out and (b) mobilising an identical area of postauricular skin for an island flap.

Fig. 24 The island of postauricular skin is fed through to replace the conchal bowl.

Microvascular free flaps

Large or composite defects with a full thickness tissue deficit may require regional flaps in conjunction with a combination of free or local flaps and grafts. Free vascularised flaps have been described for use in total nasal reconstruction, but they are bulky as the underlying fat is thick and it is difficult to thin evenly, even after several stages.Reference Moore, Strome, Kasperbauer, Sherris and Manning20, Reference Walton, Burget and Beahm34 The main use of free flaps is to provide a lining during total nasal reconstruction; skin from the forehead and face is then used to create the external surface, with bone and cartilage sandwiched in between.

Nasal reconstruction in the absence of any septal cartilage

Without the support of a septum, nasal reconstruction of the nose using any type of graft or flap is difficult. One possible technique to overcome this problem is the use of free bone and cartilage grafts sandwiched between a pericranial and paramedian forehead flap (Figure 25).Reference Brackley and Jones35 A free vascularised forearm flap, as mentioned above, may also be used. An osseointegrated replacement or prosthesis is another alternative.

Fig. 25 A pericranial flap has been used to create the inner lining of the nose, and free cartilage is then covered by a paramedian forehead flap.

Complications

Asymmetry or notching of alar margin

The main technical challenge in nasal reconstruction is to obtain symmetry of the alar margin and to create a thin, contoured lower third of the nose. The paramedian forehead flap is the main source of donor tissue. It is normally much thicker than the skin of the lower third of the nose and, whilst it can be thinned to a large extent, it is difficult to obtain a refined alar margin if it has to extend around a free cartilage graft to replace some of the missing inner lining (Figures 26 and 27). Whilst an anteriorly based septal flap can provide a vascularised inner lining and avoid the need for extension of the paramedian forehead flap past the alar margin, it is not always available. In order to avoid notching, a baton of cartilage with moderate strength needs to be placed along the alar margin, where normally there is no cartilage (Figure 28). It is important to get this right at the first stage; supplementing the alar margin at a later stage is difficult because fibrosis, once established, limits any change to its contour and the overlying soft tissue.

Fig. 26 The resulting defect one year after removal of a sarcoma-like tumour of the nose. Frozen section suggested the primary resection was complete, but paraffin sections showed this not to be the case. Further resection was undertaken, and a prosthesis was worn to allow observation for a year; only then was the nose reconstructed.

Fig. 27 Post-operative appearance of the patient shown in Figure 26. Note the thick alar rim, as the paramedian forehead flap was thinned and rolled over a baton of free cartilage, making it difficult to thin down.

Fig. 28 (a) Peri-operative view showing a baton graft placed along the alar margin. (b) Post-operative view after the second stage, when the pedicle of the paramedian forehead flap had been divided.

‘Bunching up’ due to contracture of excessive tissue

If excessive tissue is used, it will contract and roll up, and this will give an unsatisfactory contour for most areas (except the alar margin and tip which are naturally convex) (Figures 29 and 30). Bunching up is made worse if the vascular bed is poor or when the inner lining of a full thickness defect is not replaced or does not survive (Figures 31–33).

Fig. 29 A defect of the columella involving the medial, intermediate and some of the lateral crura, following Moh's micrographic surgery.

Fig. 30 Post-operative views of the patient shown in Figure 29, following division of a paramedian forehead flap. Note a slight excess of tissue has ‘bunched up’ to produce a convex tip.

Fig. 31 A defect following radiotherapy for a squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal vestibule. Note the marked radiation damage to the surrounding skin. There was also a large septal perforation.

Fig. 32 The patient shown in Figure 31, after stage one reconstruction. The end of the paramedian forehead flap is already contracting on itself, as the vascularity of the recipient site is so poor. It would have been better to remove the radiation-damaged skin and to use a larger flap.

Fig. 33 (a) In the patient shown in Figure 31, the skin contracted even more when the pedicle was divided. (b) & (c) However, local revision removed the severe fissuring that had occurred between the donor and recipient tissues.

Hair growth

If a forehead flap is used and the patient has a low hairline, or the flap needs to extend beyond the nasal tip, then it is likely to contain hair follicles which will continue to grow. The amount of growth can be reduced by thinning down the flap so that some of the hair follicles are removed, but this rarely stops them all from growing. If dark hairs grow, they can be ablated using laser; this delivers energy which is preferentially absorbed by the pigmented cells in the dark follicles (Figures 34 to 36). For light haired individuals, trimming and using a depilatory cream can help.

Fig. 34 A defect of most of the columella and lower lateral cartilages following Moh's micrographic surgery.

Fig. 35 A paramedian forehead flap (a) before and (b) after its division, in the patient shown in Figure 34; note the dark hair follicles.

Fig. 36 The patient shown in Figure 34, after the hair follicles had been treated by laser.

Stenosis and nasal obstruction

The main area where stenosis can affect function or appearance is from the alar margin to the nasal valve. Stenosis normally occurs if nonvascularised tissue is used to reconstruct more that two-thirds of the lining. For this reason, a vascularised flap is preferable, but this is not always available (Figure 37).

Fig. 37 Stenosis and collapse of the nasal valve area, due to repeated use of nonvascularised grafts to reconstruct the site of a recurrent morpheiform basal cell carcinoma. It would have been preferable for the patient to have initially undergone Moh's micrographic surgery, followed by reconstruction with vascularised tissue and cartilage for support.

Telangectasia

Skin changes can occur over grafts, especially when there has been more than one operation or when the patient has received radiotherapy. Telangectasia can be reduced with either laser treatment or hot wire cautery (Figure 38).

Fig. 38 (a) A right paramedian forehead flap. (b) Telangectasia were evident around the flap at six months post-operatively; (c) these were removed using laser.

Hypertrophic scarring

This usually occurs where fibroblasts have been primed by previous trauma or surgery. It is possible to vigorously dermabrade the skin and to reduce further scar tissue by injecting triamcinolone (Figure 39). Keloid is said not to occur in the skin of the nose, and the authors have not seen or heard of this occurring.

Fig. 39 (a) Dense fibrous tissue formed at the lateral aspect of a paramedian forehead flap. (b) This was reduced by dermabrasion and triamcinolone injection.

Intranasal crusting

This occurs when there is healing by secondary intention. It can occur at the donor site of a septal flap, or if a free graft is used for the lining and it fails to be incorporated into its vascular bed. Intranasal crusting is best minimised by regular douching and keeping the area lubricated with mupirocin or petroleum jelly. The lining will usually re-epithelialise in a few weeks.

Donor site morbidity

If a large amount of tissue is needed to repair the lower third of the nose, it may not be possible to primarily close the top aspect of the donor site on the forehead. This area heals well by secondary intention, but it remains red for several months before fading to match the surrounding skin. Skin grafts to the donor site often become pigmented and rarely look as good as if they were left to heal by secondary intention. The donor site occasionally remains red, but this normally fades after a year (Figure 40).

Fig. 40 (a) Pre-operative appearance, and (b) nine months post-operative appearance after a paramedian forehead flap reconstruction, showing how the paramedian forehead flap scarring fades after nine or more months.

Thick lower third of the nose

If the forehead flap is not thinned enough or there is excessive bulk with cartilage grafts, a slightly more convex or bulbous contour will be produced (Figure 41).

Fig. 41 (a) A dorsal defect that was repaired using a paramedian forehead flap. (b) A paramedian forehead flap has been allowed to retain some of its subcutaneous tissue, giving it a slightly convex appearance.

The paramedian forehead flap, in conjunction with other techniques, is the main method of replacing most sizeable nasal defects. However, the quality of the final result is determined by further refinement of the alar-facial sulcus, the alar-nasal sill and the alar groove.

Infection

Infection following nasal reconstruction is rare, except in individuals who are malnourished, immunosupressed or who have lost their nose because of an animal bite. Patients who have had part or all of their nose bitten off will require regular debridement and cleaning with hydrogen peroxide and povidone–iodine solution, in order to clean the site in preparation for any graft.

Below, we describe our experience reconstructing composite defects of the face involving the nose, cheek, orbit and upper lip.

Material and methods

This was a retrospective study of the methods used to reconstruct complex facial defects following resection of malignant skin lesions, in 16 patients treated at the University Hospital, Nottingham, UK.

Results

Patient one

Moh's micrographic surgery was used to excise a morpheiform BCC from the right alar region of the nose. This produced a defect involving the whole of the right ala, the lower part of the lateral subunit of the nose, and the upper part of the lateral subunit of the right upper lip (Figure 42).

Fig. 42 A full thickness defect of the right alar margin, adjacent lateral subunit of the nose, pyriform apeture and cheek, following Moh's micrographic surgery in patient one.

An island nasolabial flap was rotated to cover the upper lip defect (Figure 43). A cheek advancement flap closed the cheek defect. A cartilage graft was used to provide support for the lateral wall of the nose up to the alar margin, and was lined by a septal flap. A right paramedian flap covered the nasal defect. The flap was fashioned to replace the exact amount of tissue lost, as is customary in nasal reconstruction in order to prevent bunching up of tissue.

Fig. 43 An island nasolabial flap was used to reconstruct patient one's upper lip defect. A septal flap was used to line a cartilage graft which was then covered by a paramedian forehead flap. The nasolabial flap filled the defect of the upper lip before the cheek was advanced.

However, more cicatrisation occurred than anticipated, primarily at the junction of the flaps. This resulted in some asymmetry and a suboptimal result (Figure 44).

Fig. 44 Patient one's post-operative result at nine months. Note asymmetry because of cicatrisation at the alar base and the junction of the four flaps.

Patient two

A young girl with a haemangioma of her left cheek underwent embolisation of the lesion. Unfortunately, excessive sclerosant entered different distal tributaries to those feeding the haemangioma, and the tissue of the side of her nose and face became necrotic (Figure 45). The necrotic area extended from the left side of the upper lip to the medial subunit of the patient's left cheek, the left alar subunit, and part of the tip, dorsal and left lateral subunits of the nose. This produced scarring of the upper lip and left nasal sill with retraction of the margin of the lip (Figure 46).

Fig. 45 Infarction of the side of patient two's face and nose after embolisation of a haemangioma, due to sclerosant entering the wrong vessels.

Fig. 46 Patient two after scar tissue had formed. Note the loss of the alar region and the snarled appearance of the upper lip. Haemangioma remained at the angle of the mouth.

The avascular, scarred skin of the left upper lip and cheek was excised, along with the nasal sill and the remaining part of the tip, dorsal and lateral subunit of the nose (Figure 47). A left paramedian forehead flap was used. The tip of the flap was turned in to help create the vestibular lining, and conchal cartilage was used to support the alar margin. More tissue was used in the paramedian flap, on the basis of previous experience, to allow for cicatrisation (Figure 48). A cheek advancement flap was used to fill in the top of the upper lip and to allow the upper lip to be pulled down, in order to remove the snarl of the left upper lip (Figure 49).

Fig. 47 Patient two's scarred, avascular tissue was removed and replaced with a cheek advancement flap. The angle of the mouth was also pulled down.

Fig. 48 In patient two, a generous paramedian forehead flap was used to allow for cicatrisation at the junction of the flaps.

Fig. 49 Post-operative appearance of patient two after the second stage.

Patient three

Following Moh's micrographic surgery for a morpheiform BCC, this patient had a defect of the left lateral subunit of the nose, extending to part of the dorsal and medial subunits of the cheek and to the medial canthal subunit of the eye (Figure 50).

Fig. 50 Patient three had a defect of the left lateral subunit of the nose, extending to part of the dorsal and medial subunits of the cheek and to the medial canthal subunit of the eye.

Under local anaesthesia, the tarsal plates were divided and the remains of their medial aspect secured to the posterior lacrimal crest with 2/0 prolene thread (Figure 51). A glabellar rotation flap was used to cover the lateral and dorsal subunit defects as well as the medial canthal defect. A cheek advancement flap covered the defect of the medial subunit of the cheek (Figure 52).

Fig. 51 In patient three, the tarsal plates were divided and their medial part secured to the posterior lacrimal crest with 2/0 prolene thread. A glabellar rotation flap was used to cover the defect. A cheek advancement flap covered the defect of the medial subunit of the cheek.

Fig. 52 Patient three's post-operative appearance.

Patient four

Following Moh's micrographic surgery for a morpheiform BCC, this patient was found to have tumour infiltrating the pyriform aperture. A further resection was performed under general anaesthesia, with frozen section analysis to ensure complete removal. The medial part of the maxilla was also removed. The defect involved the full thickness of the right ala, the right half of the columella, the adjacent lateral subunit, the medial subunit of the cheek and the right part of the upper lip (Figure 53). The caudal part of the septum was also lost.

Fig. 53 Patient four underwent Moh's micrographic surgery, leaving a defect involving the full thickness of the right ala, columella, adjacent lateral subunit, medial subunit of the cheek and right part of the upper lip.

As the first step in reconstruction, a radial forearm free flap supplied by facial vessels was used to cover the whole defect (Figure 54). After four weeks, the medial part of this flap was incised and rotated medially to form the inner lining of the nose (Figure 55). Scaffolding made from auricular cartilage was used to support the nasal wall and the caudal septum. A right paramedian forehead flap was used to cover the defect of the alar and lateral subunits of the nose. A large flap was used, to account for the degree of anticipated cicatrisation (Figure 56). Three more procedures were required to thin the remainder of the free flap and to refine the contours of the nose (Figure 57).

Fig. 54 In patient four, a radial forearm free flap supplied by facial vessels was used to fill the bulk of the defect.

Fig. 55 Patient four after four weeks; the medial part of the radial forearm free flap was rotated medially to form the inner lining of the nose.

Fig. 56 In patient four, a paramedian forehead flap was used to create the external skin over a scaffold of free conchal cartilage.

Fig. 57 Patient four's post-operative appearance, after five stages.

Patient five

This patient had a SCC resected, leaving a defect of the left ala, the soft triangle and the lateral subunit, part of the dorsal and tip subunit, the left side of columella, the left alar sill and the medial subunit of the cheek (Figure 58). The resected nasal bone and part of the upper lateral cartilage were repaired with split calvarial bone secured with titanium plates and lined by a contralateral septal flap fed through an incision anterior to the septal cartilage (Figures 59 and 60). A small island nasolabial flap was used to cover the alar sill. A cheek advancement flap was used to cover the medial subunit of the cheek. The rest of the scaffolding, including the alar margins, was made with conchal cartilage. A generous paramedian forehead flap was used to cover the nasal defect, in order to allow for cicatrisation and contracture following radiotherapy (Figure 61).

Fig. 58 Resection of squamous cell carcinoma from patient five, leaving a defect of the left ala, soft triangle and lateral subunit, part of the dorsal and tip subunit, left side of the columella, left alar sill, medial subunit of the cheek, and septal mucosa.

Fig. 59 In patient five, a contralateral septal flap was fed through an incision anterior to the septal cartilage.

Fig. 60 In patient five, a split calvarial bone graft secured with titanium plates and free conchal cartilage provided the support for the lower half of the nose. Needles help to secure the cartilage in position until they are sutured in place.

Fig. 61 In patient five, a generous paramedian forehead flap was used to cover the nasal defect, in order to allow for cicatrisation and contracture following radiotherapy.

A year later, an accident avulsed the bone graft intranasally, and the bone graft then became infected. Its removal contributed to contracture of the side of the patient's nose (Figure 62). Because of the unsightly asymmetry, a right paramedian flap was used to reconstruct the defect, with the dorsal skin turned in to form the internal lining. After four weeks, the flap was shown to be non-viable when a tourniquet was placed around the pedicle, so division of the pedicle was delayed for a further two weeks (Figure 63).

Fig. 62 A year after reconstruction, patient five suffered an accident which avulsed his bone graft intranasally; the graft then became infected. Its removal caused contraction of the side of his nose.

Fig. 63 A right paramedian forehead flap was used to rebuild patient five's nose. After four weeks, the flap was shown to be non-viable when a tourniquet was placed around the pedicle, so division of the pedicle was delayed a further two weeks.

One year after the paramedian forehead flap there was some asymmetry of the alar subunit due to cicatrisation at the junction of the three flaps. At the time of writing, an alar groove had yet to be created (Figure 64).

Fig. 64 One year after paramedian forehead flap, patient five had some asymmetry of the alar subunit due to cicatrisation at the junction of the three flaps. An alar groove had not yet been created.

Patient six

This patient had a morpheiform BCC of the left medial canthal region removed by Moh's micrographic surgery. Enucleation of the left eye was necessary (Figure 65). The defect involved the eye, the medial subunit of the cheek, part of the left and right lateral subunits and the dorsal subunit. Cheek advancement flaps were used to cover the defects in both cheeks. A right paramedian flap was used to cover the nasal defect. A scalp rotation flap was brought forward to cover the forehead defect (Figure 66). Hair follicles within the flap were removed using a diode laser, and an orbital prosthesis was fitted (Figure 67).

Fig. 65 Patient six had a morpheiform basal cell carcinoma of the left medial canthal region, removed by Moh's micrographic surgery. This case illustrates how unpredictable and extensive this tumour can be.

Fig. 66 A scalp rotation flap was brought forward to cover patient six's forehead defect.

Fig. 67 In patient six, hair follicles within the flap were removed using a diode laser, and an orbital prosthesis was fitted.

Patient seven

Patient seven had a morpheiform BCC excised from the columella and adjoining upper lip by Moh's micrographic technique. The resulting defect involved the whole of the columella, the caudal aspect of the septum, the left alar sill, and part of the philtrum and adjoining left part of the upper lip (Figure 68). The patient expressed a wish to be able to grow a moustache after reconstruction. The skin of the lateral units of both upper lips and some of the skin of both cheeks was mobilised and advanced to the midline along the vermillion border (Figure 69). A crescent-shaped piece of skin and tissue was removed from the alar crease on both sides to help prevent bunching up of tissue. The junction of the two flaps constituted the left border of the new philtrum, and a superficial skin incision was made to create the appearance of a right philtral ridge. A composite graft from the pinna was used to reconstruct the columella and the left alar sill (Figures 70 and 71).

Fig. 68 The defect left following removal of patient seven's basal cell carcinoma, which comprised the whole of the columella, the caudal septum, the left alar sill, and part of the philtrum and adjoining left part of the upper lip.

Fig. 69 Patient seven wanted to keep his moustache, so both cheeks were mobilised and advanced to the midline along the vermillion border.

Fig. 70 In patient seven, a composite auricular graft was used to reconstruct the columella and the left alar sill.

Fig. 71 Patient seven's post-operative appearance, with a moustache.

Patient eight

This patient had a morpheiform BCC removed by Moh's micrographic technique, leaving a defect involving the whole of the right alar subunit, the lower part of the lateral subunit and the adjacent medial subunit of the cheek (Figure 72). A septal flap was used to form the inner lining, and the scaffolding was provided by conchal cartilage (including the alar margin). A cheek advancement flap closed the cheek defect. A right paramedian flap was used to cover the nasal defect. The lower end of this flap was turned in to form the skin lining of the vestibule (Figures 73 and 74).

Fig. 72 Patient eight underwent Moh's micrographic surgery, leaving a defect involving the right alar subunit, the lower part of the lateral subunit and the adjacent medial subunit of the cheek.

Fig. 73 A septal flap, conchal cartilage, cheek advancement flap and right paramedian flap were used for patient eight's reconstruction.

Fig. 74 Patient eight's post-operative appearance after two stages.

Patient nine

After Moh's micrographic surgery, this patient had a defect involving the right alar margin and extending to the adjacent lateral subunit of the nose and the medial subunit of the cheek (Figure 75). The alar margin was supported with a cartilage baton, and a small island nasolabial flap was used to form the margin of the nostril (Figure 76). The medial subunit of the cheek was covered with a cheek advancement flap. The alar subunit and the adjoining lateral subunit defect were replaced with a right paramedian forehead flap (Figure 77). The nasolabial flap was small and thus the degree of cicatrisation was expected to be proportionally small. Therefore, the tissue for the nasal subunits was not increased. Post-operatively, there was no cicatrisation (Figure 78).

Fig. 75 After Moh's micrographic surgery, patient nine was left with a defect involved the right alar margin and extending to the adjacent lateral subunit of the nose and the medial subunit of the cheek.

Fig. 76 In patient nine, the alar margin was supported with a cartilage batten, and a small island nasolabial flap was used to form the margin of the nostril.

Fig. 77 Patient nine's alar subunit and adjoining lateral subunit defect were replaced with a right paramedian forehead flap.

Fig. 78 Patient nine's post-operative appearance.

Patient 10

In this patient, a morpheiform BCC was excised from the region of the alar crease, producing a defect of the left alar sill and lateral part of the ala extending to the lateral subunit, and of the adjoining medial subunit of the cheek and lateral subunit of the upper lip. This was complicated by an unsightly crater in the forehead where a previous lesion had been repaired with a partial thickness skin graft (Figure 79). An anteriorly based septal flap was used for the inner lining. The alar margins were supported with cartilage grafts. An island nasolabial flap was used to replace the defect of the upper lip (Figure 80). A cheek advancement flap covered the defect of the medial aspect of the cheek. The alar defect and lateral subunit were reconstructed with a paramedian forehead flap sufficiently larger than the tissue it replaced to allow for cicatrisation. The forehead defect was allowed to heal by secondary intention.

Fig. 79 Patient ten had a morpheiform BCC excised, producing a defect of the left alar sill, lateral ala and lateral subunit, and extending to the adjoining medial subunit of the cheek and lateral subunit of the upper lip. An unsightly crater in the forehead existed where a previous lesion had been repaired with a partial thickness skin graft (these defects are best left to heal by secondary intention).

Fig. 80 In patient ten, an anteriorly based septal flap was used for the inner lining. The alar margins were supported with cartilage grafts. An island nasolabial flap was used to replace the defect of the upper lip. A cheek advancement flap covered the medial aspect of the cheek. The alar defect and lateral subunit were replaced with a paramedian forehead flap that was larger than the tissue it replaced, to allow for cicatrisation.

At the time of writing, the patient was awaiting a third stage to thin down the alar segment (Figure 81).

Fig. 81 Patient ten's post-operative appearance after the second stage. A third stage to thin down the alar segment is a further option.

Patient 11

As a result of invasive aspergillosis, this patient developed a full thickness defect involving the dorsal subunit of the upper and middle third of the nose and adjacent lateral subunits (Figure 82). The septum, ethmoid sinuses and turbinates were completely lost.

Fig. 82 Patient eleven suffered invasive aspergillosis while immunocompromised, resulting in a full thickness defect involving the dorsal subunit of the upper and middle third of the nose and adjacent lateral subunits.

In order to create an inner lining, the dorsal skin surrounding the defect was turned in. The upper lateral cartilages and dorsal strut were recreated from conchal cartilage. Paramedian and cheek advancement flaps were used to replace the skin (Figure 83). Dark hair follicles gave the skin a grey appearance (Figure 84), but these were subsequently ablated by laser treatment (Figure 85).

Fig. 83 In patient eleven, the dorsal skin surrounding the defect was turned in. Conchal cartilage was used for the scaffolding. A paramedian and cheek advancement flap was used to replace the skin.

Fig. 84 In patient eleven, dark hair follicles gave the skin a grey appearance; these were subsequently ablated by laser treatment.

Fig. 85 Patient eleven's post-operative appearance.

After several months, the left side of the patient's nose was less pronounced and a free cartilage graft was placed. This became infected and was removed, thankfully without any detrimental effect.

Patient 12

Following Moh's surgery for a basal cell carcinoma, this patient was left with a full thickness defect of the left alar area and cheek and a small defect of the right alar area, along with scarring in the nasal tip area from a previous skin graft (Figure 86). The graft and the bridge of tissue between the defects in the left and right alae were removed, along with the tip subunit. The resulting defect was reconstructed with a posteriorly based septal flap for the inner lining, conchal cartilage for scaffolding, and paramedian and cheek advancement flaps for the external skin lining (Figure 87). After two further stages, depilatory cream was used to reduce hair growth at the nasal tip.

Fig. 86 After Moh's surgery, patient twelve was left with a defect of the left alar area and cheek and a small defect of the right alar area, along with scarring of the nasal tip area from a previous skin graft.

Fig. 87 A posteriorly based septal flap, conchal cartilage for scaffolding, and paramedian and cheek advancement flaps were used for reconstruction of patient twelve's defect.

Patient 13

A young man presented with scar tissue at his left alar base and cheek, along with loss of the alar area and part of the lateral subunit (Figure 88). He had had a hamartoma removed, and two previous attempts had been made at another hospital to reconstruct his nose with free composite grafts; these attempts had failed.

Fig. 88 Patient thirteen was left with a defect following several operations at another unit; note scarring and cicatrisation of the alar base and cheek, and loss of the alar and lateral subunits.

Free conchal cartilage was placed between a septal and paramedian forehead flap (Figure 89). However, even before the pedicle was divided, the tissue started to contract because of the poor vascularity at the alar base. Following division of the pedicle, the grafted tissue contracted even more and was pale due to poor vascularity. This tissue was rotated inferiorly as far as possible and thinned down, but some asymmetry remained (Figure 90). In retrospect, more of the avascular tissue in this patient's cheek should have been removed and a cheek advancement flap used to create a new and better vascularised base, and a larger paramedian forehead flap should have been used to allow for contraction.

Fig. 89 Patient thirteen's alar defect was reconstructed with a septal flap, conchal cartilage and a generous paramedian flap to allow for cicatrisation, given the previous scar tissue.

Fig. 90 Patient thirteen's post-operative appearance after the ala had been thinned.

Patient 14

In this patient, Moh's surgery following resection of a basal cell carcinoma resulted in a full thickness defect of the left ala extending to the adjoining cheek and upper lip (Figure 91). The alar defect was reconstructed with a septal flap, conchal cartilage and a generous paramedian flap to allow for cicatrisation (Figure 92). The cheek defect was covered with a cheek advancement flap and the upper lip with a superiorly based nasolabial flap. A full thickness skin graft was used to overcome the ectropion that occurred after the cheek advancement flap (Figure 93).

Fig. 91 In patient fourteen, Moh's surgery resulted in a full thickness defect of the left ala extending to the adjoining cheek and upper lip.

Fig. 92 Patient fourteen's alar defect was reconstructed with a septal flap, conchal cartilage and a generous paramedian flap to allow for cicatrisation.

Fig. 93 A full thickness skin graft was used in patient fourteen to overcome the ectropion that occurred after the cheek advancement flap.

Patient 15

An 83-year-old woman had two defects following Moh's micrographic surgery, which involved the tip of her nose and her right alar groove into the cheek (Figure 94). A dorsal advancement flap replaced the tip defect, and a cheek and nasolabial flap was advanced over a free conchal cartilage baton that was used to reinforce the right alar margin (Figure 95). No further stages were required (Figure 96).

Fig. 94 Patient fifteen was left with two defects after Moh's micrographic surgery of the tip and right alar groove extending into the cheek.

Fig. 95 In patient fifteen, a dorsal advancement flap was used to reconstruct the tip, and a free cartilage graft was covered by a cheek and nasolabial rotation and advancement flap to repair the right alar defect.

Fig. 96 Patient fifteen's post-operative appearance at eight months.

Patient 16

This patient had had many years of problems with a morpheiform BCC which had spread over the whole of her nose and cheeks. This had been successfully removed at another unit and the defect repaired with a skin graft. However, this had left the patient with severe right ectropion, loss of both alar margins and a twisted columella. Several skin grafts had been used in attempts to correct her ectropion (Figure 97).

Fig. 97 Pre-operative appearance of patient sixteen's cicatrised nostrils, loss of nostril margins, twisted columella and severe right ectropion after skin grafting at another unit.

The patient's ectropion was repaired by attaching the medial part of her canthal ligament with 2/0 prolene thread to a burr hole just behind the posterior lacrimal crest (any further forward and there is often blunting of the medial canthus). A pedicled flap from the dorsum of the nose was then used to replace the defect in the lower eyelid and cheek. The patient's nose was reconstructed by folding her dorsal skin down to provide an internal lining, using free conchal cartilage for the scaffolding of the nose along with a robust alar rim, and covering this with a larger paramedian forehead flap. Three stages were needed to divide the pedicle and to thin down the graft, in order to create alar grooves (Figure 98).

Fig. 98 Patient sixteen's post-operative appearance after six months.

Discussion

When a defect involves the nose and adjacent subunits, meticulous planning is essential before surgery. We would generally concur with the principle that if the defect involves more than 50 per cent of the subunit, then the whole subunit needs to be sacrificed for a better cosmetic result.Reference Burget, Menick, Burget and Menick9, Reference Dowley, Allibone and Jones10 However, we make an exception to this rule when the defect involves part of the columella or alar margin, in which case we retain the skin as much as possible after the defect has been made symmetrical. As far as is possible, each subunit is reconstructed with a different flap, so that the junction of the flaps is along the junction of the subunits.Reference Tardy36, Reference Danahey and Hilger37 Most flaps used in reconstructing these defects (apart from the paramedian forehead flap) come from a neighbouring nasolabial island flap or a cheek advancement flap. The principle of reconstructing a full thickness defect with an outer and inner vascular lining with central scaffolding was used in all our cases.Reference Burget, Menick, Burget and Menick9 The inner vascularised lining was usually provided by an anteriorly based septal mucosal flap. Free auricular conchal cartilage was used to recreate the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilage and alar margin, and the alar margin was supported with a baton of cartilage to prevent retraction. We avoided alloplast materials for scaffolding wherever possible, as these have an increased risk of infection and migration especially in large or weight-bearing areas.Reference Raghavan and Jones38, Reference Raghavan, Jones and Romo39

From our series, we observed that the degree of contracture was unpredictable where three or more flaps joined. This has also been observed by Shan Baker when describing one case involving reconstruction of the ala, cheek and upper lip.Reference Baker, Baker and Naficy40 This problem was overcome when we used flaps that were slightly bigger than the defect, to allow for possible cicatrisation. Any remaining disparity was then dealt with at the second or third stage, and was then a simpler problem to resolve than a shortage of tissue.

Conclusion

If a defect requires three or more flaps to reconstruct adjoining aesthetic units, there can be unpredictable cicatrisation at their junction. This particularly applies to the alar base. In these circumstances, we recommend replacing the nasal defect with more tissue in the paramedian forehead flap than when the subunits of the nose are being reconstructed on their own.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr William Perkins and Dr Sandeep Varma, dermatological surgeons, whose excellent Moh's micrographic surgery skill gave us the reassurance that reconstruction could be done on a disease-free foundation. We also thank Lorraine Abbercrombie, occuloplastic surgeon, who helped with patients three and 14.