Introduction

Palmer amaranth is indigenous to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico (Sauer Reference Sauer1957). Despite being previously described as an edible plant (Smith Reference Smith1900), Palmer amaranth has long been documented as a serious weed problem in U.S. cropping systems (Hamilton and Arle Reference Hamilton and Arle1958). Human-driven selection has strongly contributed to the rise of Palmer amaranth as a problematic weed. In the 1970s, when cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) picking became mechanized, machinery contributed to the spread of Palmer amaranth seeds across the southern United States (Sauer Reference Sauer1972). At that time, Palmer amaranth was considered the most successful weed of all dioecious Amaranthus species as it continued to spread across cotton fields (Sauer Reference Sauer1972). The spread of Palmer amaranth was facilitated by increased equipment movement across U.S. regions. In addition, the diversity of crops at the landscape level has decreased throughout the last century (Hiller et al. Reference Hiller, Powell, McCoy and Lusk2009). Modern agriculture in the United States is composed of a few dominant row crops planted in rotations, and Palmer amaranth has shown an extraordinary ability to infest such crops (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013). Moreover, conservation agriculture is widely adopted in U.S. cropping systems, and Palmer amaranth tends to thrive in no-till fields due to its small seed size, which contributes to the rapid increase of infestations in crops (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013). Currently, Palmer amaranth is the most economically damaging weed species infesting corn (Zea mays L.), cotton, and soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) fields in the southern United States (Price et al. Reference Price, Balkcom, Culpepper, Kelton, Nichols and Schomberg2011; Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013).

The economic importance of Palmer amaranth is primarily related to its ability to evolve resistance to herbicides. The presence of herbicide-resistant Palmer amaranth in row crops leads to increased control costs (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013). The history of herbicide resistance evolution in Palmer amaranth is a reflect of intense reliance and selection pressure from herbicides over time. In the 1990s, the first documented cases of herbicide resistance were against microtubule-inhibitor (Gossett et al. Reference Gossett, Murdock and Toler1992), acetolactate synthase (ALS)-inhibitor (Horak and Peterson Reference Horak and Peterson1995), and photosystem II (PSII)-inhibitor herbicides (Heap Reference Heap2020). After the introduction of glyphosate-resistant (GR) crops, weed management strategies shifted from the use of multiple herbicide sites of action (SOA) in a single season to reliance on single SOA POST herbicide (e.g., glyphosate) within and across growing seasons (Powles Reference Powles2008). POST applications of glyphosate became widely used for weed management in soybean, cotton, and corn production, resulting in rapid evolution of GR Palmer amaranth (Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, Grey, Vencill, Kichler, Webster, Brown, York, Davis and Hanna2006). The spread of GR Palmer amaranth led to a reevaluation of the use of glyphosate as a sole means of weed control, and a push to diversify weed management strategies (e.g., additional herbicide SOA). The use of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD)-inhibitor, PPO-inhibitor, and long-chain fatty acid elongase–inhibitor herbicides increased in an attempt to manage GR Palmer amaranth. However, Palmer amaranth has also evolved resistance to these herbicide SOA (Heap Reference Heap2020). New technologies such as auxin-resistant crops may be jeopardized by the newest reports of 2,4-D-resistant Palmer amaranth (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Liu, Boyer and Stahlman2019) and the number of accessions with resistance to multiple herbicide SOA is also on the rise (Schwartz-Lazaro et al. Reference Schwartz-Lazaro, Norsworthy, Scott and Barber2017). Therefore, Palmer amaranth herbicide resistance evolution is rapidly limiting the chemical control options for weed management in corn, soybean, and cotton fields within U.S. cropping systems.

Thus far, Palmer amaranth has evolved resistance to eight herbicide SOA (Heap Reference Heap2020), which is a major concern because weed management in conventional U.S. cropping systems is largely herbicide dependent. Factors relating to the intrinsic biology of Palmer amaranth have also contributed to its fast herbicide resistance evolution (Ward et al. Reference Ward, Webster and Steckel2013). Palmer amaranth grows up to 2 m tall with many lateral branches and produces thousands of seeds (Sauer Reference Sauer1955), making it a very competitive species with crops (Massinga et al. Reference Massinga, Currie and Trooien2003; Morgan et al. Reference Morgan, Baumann and Chandler2001). Moreover, Palmer amaranth reproduces via obligate cross pollination, which increases the chances of herbicide-resistance alleles transferring via gene flow within and across populations (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Ward, Bukun, Preston, Leach and Westra2012; Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Gaines, Patterson, Jhala, Irmak, Amundsen and Knezevic2018). The spread of GR Palmer amaranth across the southern and midwestern United States is occuring through both independent herbicide selection (Küpper et al. Reference Küpper, Manmathan, Giacomini, Patterson, McCloskey and Gaines2018) and seed dispersal (Farmer et al. Reference Farmer, Webb, Pierce and Bradley2017; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Griffith, Griffin, Bagavathiannan and Gbur2014). The recent migration of Palmer amaranth into the midwestern United States poses a serious threat to the sustainability of crop production in the region (Chahal et al. Reference Chahal, Varanasi, Jugulam and Jhala2017; Kohrt et al. Reference Kohrt, Sprague, Nadakuduti and Douches2017). Palmer amaranth is now overlapping territory with another problematic dioecious Amaranthus species, waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus syn. rudis; Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Gaines, Patterson, Jhala, Irmak, Amundsen and Knezevic2018). Therefore, the monitoring of Palmer amaranth infestations and diagnosis of herbicide resistance is extremely important to agricultural stakeholders.

Recent advances in high-throughput genome sequencing methods are expediting the elucidation and detection of herbicide resistance mechanisms in Palmer amaranth and other weed species. For glyphosate, the most common resistance mechanism in Palmer amaranth is EPSPS gene amplification (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Shaner, Ward, Leach, Preston and Westra2011, Reference Gaines, Patterson and Neve2019), whereas for PPO-inhibitor resistance, the major resistance mechanism is the PPO2 glycine 210 deletion (ΔG210; Salas et al. Reference Salas, Burgos, Tranel, Singh, Glasgow, Scott and Nichols2016; Salas-Perez et al. Reference Salas-Perez, Burgos, Rangani, Singh, Refatti, Piveta, Tranel, Mauromoustakos and Scott2017). Nevertheless, novel herbicide resistance mechanisms in Palmer amaranth are still being uncovered (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Patterson and Neve2019), as evidenced by the recent documentation of two mutations in the PPO2 enzyme in the R128 site of Palmer amaranth (Giacomini et al. Reference Giacomini, Umphres, Nie, Mueller, Steckel, Young, Scott and Tranel2017), and G399A, an amino acid substitution of glycine to alanine in the catalytic domain of PPO2 at position 399 (Rangani et al. Reference Rangani, Salas-Perez, Aponte, Knapp, Craig, Mietzner, Langaro, Noguera, Porri and Roma-Burgos2019). A few reports of nontarget-site resistance (NTSR) to glyphosate have been confirmed in Palmer amaranth (Dominguez-Valenzuela et al. Reference Dominguez-Valenzuela, Gherekhloo, Fernández-Moreno, Cruz-Hipolito, Alcántara-de la Cruz, Sánchez-González and De Prado2017; Palma-Bautista et al. Reference Palma-Bautista, Torra, Garcia, Bracamonte, Rojano-Delgado, Alcántara-de la Cruz and De Prado2019) and one NTSR has been confirmed for PPO-inhibitor herbicides (Varanasi et al. Reference Varanasi, Brabham and Norsworthy2018a). Detecting NTSR mechanisms in weed species is challenging because multiple genes can endow resistance (Ghanizadeh and Harrington Reference Ghanizadeh and Harrington2017). Therefore, using genotypic assays might provide faster detection of known herbicide resistance mechanisms in Palmer amaranth, but genotypic assays fail to address novel resistance mechanisms, including metabolic resistance involving cytochrome P450 genes as well as unknown target-site resistance (TSR) mechanisms.

In Nebraska, corn and soybean growers strongly rely on glyphosate and PPO-inhibitor (e.g., fomesafen and lactofen) herbicides for weed management (Sarangi and Jhala Reference Sarangi and Jhala2018). In autumn 2017, growers in the southwest part of the state reported failure to control Palmer amaranth with glyphosate and PPO-inhibitor herbicides (R Werle, personal communication). Different strategies have been used for herbicide resistance confirmation, including herbicide application on suspected resistant plants under field conditions, harvesting suspected resistant plant seeds to conduct whole-plant and seed bioassays under control conditions (Burgos Reference Burgos2015), and/or collecting plant leaf tissue to assess herbicide resistance through biochemical and molecular techniques (Dayan et al. Reference Dayan, Owens, Corniani, Silva, Watson, Howell and Shaner2015; Délye et al. Reference Délye, Duhoux, Pernin, Riggins and Tranel2015). However, herbicide resistance confirmation can be labor-intensive, and growers typically hope for rapid screening results to make appropriate weed management decisions in the upcoming growing season. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to 1) confirm glyphosate and PPO-inhibitor resistance in 51 Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska via genotypic resistance assays, 2) validate the genotypic assay results using whole-plant greenhouse phenotypic assays of progenies in the same accession via correlation and cluster analysis, and 3) evaluate agronomic practices that may contribute to glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth accessions.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growing Conditions

The study was performed with 51 arbitrarily selected Palmer amaranth accessions infesting crops across southwestern Nebraska. Each accession was collected from a single field. Location, agronomic practices, Palmer amaranth distribution, and density of each accession were recorded (Table 1). In August 2017, green leaf tissues were harvested from 5 random plants (parent) from each of the 51 Palmer amaranth accessions, then labeled and stored at −80 C to be used in genotypic assays. Within the 51 Palmer amaranth accessions, a second sample of 19 arbitrarily selected accessions was obtained by collecting seeds (progeny) of 30 random plants from each accession in September 2017, then cleaned, and stored at 5 C until the onset of the whole-plant phenotypic assay. Seeds were planted in 900 cm3 plastic trays containing potting-mix (Pro-Mix®, HP Mycorrhizae, Premier Tech Horticulture, Delson, QC, Canada). Emerged seedlings (1 cm) were transplanted into 164 cm3 containers (Ray Leach “Cone-tainer” SC10®, Stuewe and Sons Inc, Tangent, OR). Palmer amaranth plants were supplied with adequate water and kept under greenhouse conditions at 28/20 C day/night temperature with 80% relative humidity. Artificial lighting was provided using metal halide lamps (600 mmol m−2 s−1) to ensure a 15-h photoperiod.

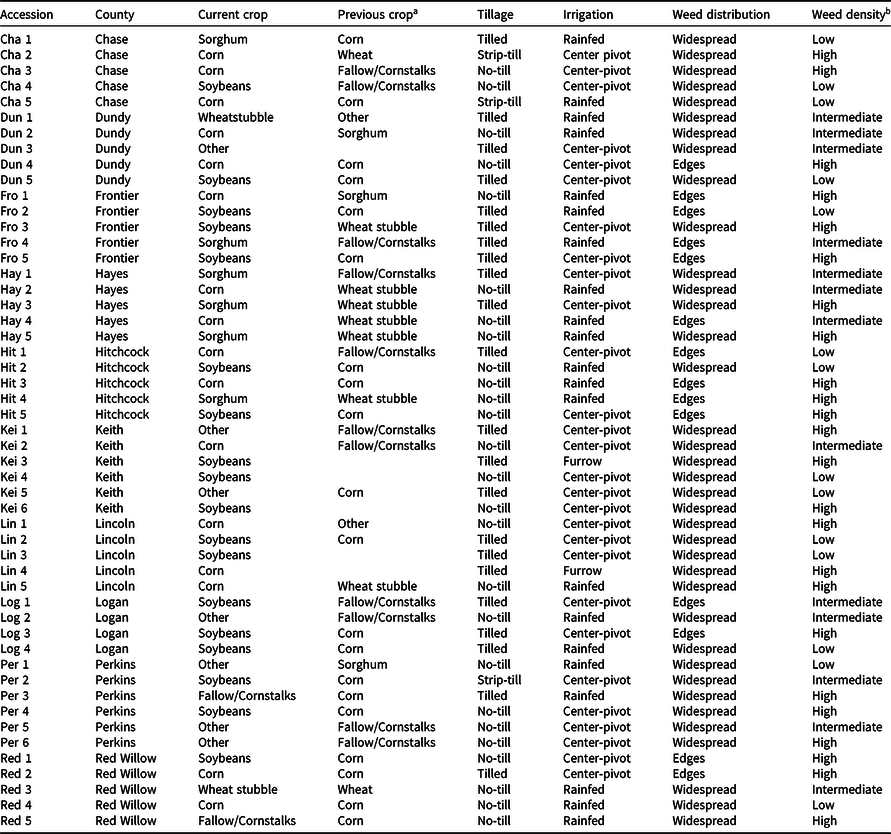

Table 1. Agronomic and demographic information of Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska evaluated in this study.

a Empty cells in the “Previous crop” column indicate unidentified crops; “Other” indicate alfalfa, dry beans, or field peas.

b Low: <3 plants m−2; Intermediate: 3–10 plants m−2; High: >10 plants m−2.

Genotypic Herbicide Resistance Mechanisms Assays

Following the standard methodology from the University of Illinois Plant Clinic, three to five leaf tissue samples were collected from each of the 51 Palmer amaranth (parent) accessions collected from southwestern Nebraska. Genomic DNA extraction from leaf tissue samples were performed using a modified CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle Reference Doyle and Doyle1987). DNA quality and quantity were checked on a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA) and any samples with low DNA yields or high protein-to-DNA ratios were discarded and reextracted. The EPSPS copy number (gene amplification) was estimated for each plant based on DNA extracted from tissue from a single leaf of Palmer amaranth. Samples were tested for glyphosate resistance via increased numbers of EPSPS genomic copies using a SYBR quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) approach (Chatham et al. Reference Chatham, Bradley, Kruger, Martin, Owen, Peterson, Mithila and Tranel2015) in which EPSPS copy numbers were estimated based on comparison with a single-copy reference gene (CPS, for carbamoyl phosphate synthetase). Although the assay was originally developed for waterhemp, the same primers and assay conditions were confirmed to be suitable for Palmer amaranth (Nakka et al. Reference Nakka, Godar, Wani, Thompson, Peterson, Roelofs and Jugulam2017). The EPSPS primers are in a region of the gene that is highly conserved between waterhemp and Palmer amaranth. TaqMan qPCR assays were used to assess for the presence of two known PPO-inhibitor resistance mutations in the PPO2 enzyme, including the glycine 210 deletion (Wuerffel et al. Reference Wuerffel, Young, Lee, Tranel, Lightfoot and Young2015) and the R128 glycine (R128G) and/or R128 methionine (R128M) mutations (Varanasi et al. Reference Varanasi, Brabham, Norsworthy, Nie, Young, Houston, Barber and Scott2018b).

Accessions with individuals containing more than two EPSPS copy numbers were considered GR, and individuals with the presence of ΔG210 or R128G/R128M mutations were considered PPO-inhibitor resistant. Other TSR and NTSR mechanisms were not tested.

Whole-Plant Phenotypic Assay of Progenies

This aspect of the research was conducted under greenhouse conditions in 2018 and 2019 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to evaluate the sensitivity of 19 Palmer amaranth (progeny) accessions from southwestern Nebraska to glyphosate and PPO-inhibitor herbicides.

The experiments were conducted in a complete randomized design and the experimental unit was a 164 cm3 cone-tainer with a single Palmer amaranth seedling. The study was arranged in a factorial design with Palmer amaranth progenies from 19 accessions and 3 herbicides with 20 replications and conducted twice (two experimental runs). Altogether, 2,280 Palmer amaranth seedlings were screened in the phenotypic assay. The arbitrarily selected 19 Palmer amaranth progenies were from Cha 3, Dun 3, Dun 4, Dun 5, Hay 1, Hay 3, Hay 4, Kei 2, Kei 3, Kei 5, Kei 6, Log 1, Log 2, Log 4, Per 2, Per 4, Red 2, Red 4, and Red 5 accessions (Table 1). Herbicides that were applied included glyphosate (Roundup PowerMAX®, Bayer Crop Science, Saint Louis, MO) at 870 g ae ha−1 plus 2,040 g ha−1 ammonium sulfate (DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, GA); fomesafen (Flexstar®, Syngenta Crop Protection, Greensboro, NC) at 226 g ai ha−1 plus 0.5 L ha−1 of nonionic surfactant (Induce®, Helena Agri-Enterprises, Collierville, TN); and lactofen (Cobra®, Valent US LLC Agricultural Products, Walnut Creek, CA) at 219 g ai ha−1 plus 0.5 L ha−1 of nonionic surfactant.

Herbicide treatments were applied to 8- to 10-cm-tall Palmer amaranth plants with a single-nozzle chamber sprayer (DeVries Manufacturing Corp., Hollandale, MN). The sprayer had an 8001 E nozzle (Spraying Systems Co., Wheaton, IL) calibrated to deliver 140 L ha−1 spray volume at 135 kPa at a speed of 2.3 km h−1. Palmer amaranth accessions were visually assessed 21 d after treatment (DAT) as dead or alive. Plants within each accession-herbicide treatment were considered alive when prominent green tissue was observed in growing plants, whereas completely necrotic plants were considered dead.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses presented herein were performed using R statistical software version 4.0.0 (R Core Team 2020).

Genotypic and Phenotypic Validation of Glyphosate and PPO-Inhibitor Resistance in Palmer Amaranth

The number of GR or PPO-inhibitor resistant Palmer amaranth individuals (parent plants) in the genotypic assays was converted to a percentage scale:

where G represents the percent of GR or PPO-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth individuals, S is the total number of Palmer amaranth individuals that tested positive for genotypic herbicide resistance, and T is the total number of Palmer amaranth individuals (n = 3 to 5) screened for herbicide resistance in the genotypic assays. Fomesafen and lactofen are PPO-inhibitor herbicides; thus, G is same for both herbicides.

The number of surviving individuals in the phenotypic assay of Palmer amaranth progeny individuals were converted into a percentage scale:

where P represents the percent of surviving Palmer amaranth individuals after herbicide treatment in the phenotypic assay (glyphosate, fomesafen, or lactofen), X is the total number surviving Palmer amaranth individuals 21 DAT, and T is the total number of Palmer amaranth individuals (n = 40) treated with each herbicide. P (%) was determined only for the 19 accessions that were screened. Data from two experimental runs were combined.

The G and P validation was performed with the 19 Palmer amaranth accessions treated with herbicide in the phenotypic assay (using progeny plants) as well as their respective genotypic (parent plants) assay results. We were interested to learn whether parental genotype within accessions correlated to their respective progeny phenotype. The correlation between G and P for each herbicide (glyphosate, fomesafen, and lactofen) and between the two PPO-inhibitor herbicides (fomesafen and lactofen) were performed with Pearson’s analysis using the built-in cor.test function in R. The correlation value varies from −1 to 1, where 1 is the total positive correlation, −1 is the total negative correlation, and 0 indicates no linear correlation. Pearson’s analysis tests the null hypothesis that correlation between two variables is equal to zero. If P-value > 0.05, the probability >5% that a correlation of some magnitude between two variables could occur by chance alone assuming null hypothesis is true; thus, there would be no correlation between variables.

Cluster Analyses

A clustering algorithm (k-means) was used to group the data based on G and P similarities of Palmer amaranth accessions studied herein. The k-means algorithm randomly assigns each individual data point to a cluster (Hartigan and Wong Reference Hartigan and Wong1979). The k-means was performed using the built-in kmeans function in R. The number of clusters (k) was performed using the gap statistic method (Tibshirani et al. Reference Tibshirani, Walther and Hastie2001). The number of k was estimated using tidy, augment, and glance functions from the tidymodels package in R (Kuhn and Wickham Reference Kuhn and Wickham2020). The appropriate number of k for a given dataset is estimated with the lowest total within-cluster sum of squares (Wk), which represents the variance within the clusters. The error measure Wk decreases monotonically as k increases, but from some k onward the decrease flattens markedly (Tibshirani et al. Reference Tibshirani, Walther and Hastie2001). The location at which Wk bends to a plateau indicates the appropriate number of k.

Random Forest Analyses: Classification of Factors Influencing Glyphosate Resistance

Random forest is a powerful, ensembled machine-learning algorithm that generates and combines multiple decision trees in an attempt to obtain a consensus. The random forest procedure is described in detail by Breiman (Reference Breiman2001) and by Biau and Scornet (Reference Biau and Scornet2016). In short, the random forest analysis is largely based on two parameters: ntree, which is the number of decision trees; and mtry, the number of different predictors tested in each tree. For each decision tree, a subsample of observations from the data is selected with replacement to train the trees (bootstrap aggregating). These “in-bag” samples include approximately 66% of the total data and some observations may be repeated in each new training data set because this sampling occurs with replacement. The remaining 33% of the data are designated “out-of-bag” or OOB samples and are used in an internal cross-validation technique to estimate the model performance error. To evaluate the importance of an explanatory variable (or predictor), the random forest measures both the decrease in model performance accuracy as calculated by the OOB error and the decrease in the Gini index value. The Gini index value (mean decrease in accuracy) is the mean of a total variable decrease of a node impurity, weighted by the proportion of samples reaching that node in each individual decision tree. Therefore, variables with a large Gini index value indicates higher variable importance, and are more important for data classification. Random forest has been used to described the incidence of crop disease (Langemeier et al. Reference Langemeier, Robertson, Wang, Jackson-Ziems and Kruger2016) and glyphosate resistance in Amaranthus spp. (Vieira et al. Reference Vieira, Samuelson, Alves, Gaines, Werle and Kruger2018).

The random forest analysis was conducted using genotypic results of 51 Palmer amaranth accessions (Table 1). The random forest was performed with the randomForest package in R software to describe the influence of EPSPS gene amplification (genotypic results), PPO-inhibitor resistance (genotypic results), location (county), agronomic practices (e.g., tillage, irrigation, current and previous cropping systems), and weed demographics (e.g., density and distribution) on glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth in southwestern Nebraska (Table 1). EPSPS gene copy number (genotypic results) was included as an explanatory variable to test the robustness of random forest because it is known to highly correlate with glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Patterson and Neve2019). For this analysis, the ntree parameter was set to 500, whereas mtry was set to 2 (default values).

Results and Discussion

Genotypic Confirmation and Phenotypic Validation of EPSPS- and PPO-Inhibitor Resistance in Palmer Amaranth

The individuals screened in the genotypic and phenotypic assays represent parents and their progeny, respectively. This methodology was chosen to simulate a real-farm scenario in which growers collect leaf samples from suspected herbicide-resistant accessions and mail them to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Plant Clinic for molecular herbicide resistance confirmation; or to represent a situation in which a suspected herbicide-resistant seed sample is mailed to a state university weed science program for herbicide resistance confirmation through whole-plant bioassays. We were interested in the correlation and clustering analyses of these two approaches.

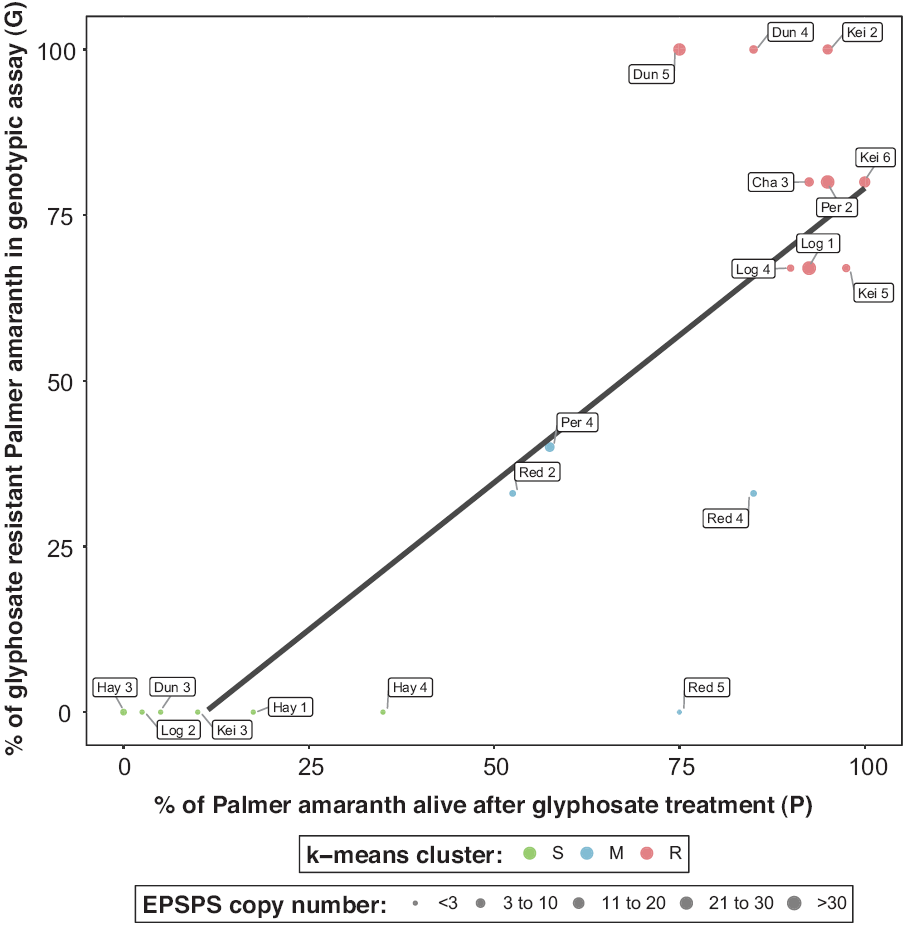

Glyphosate Resistance

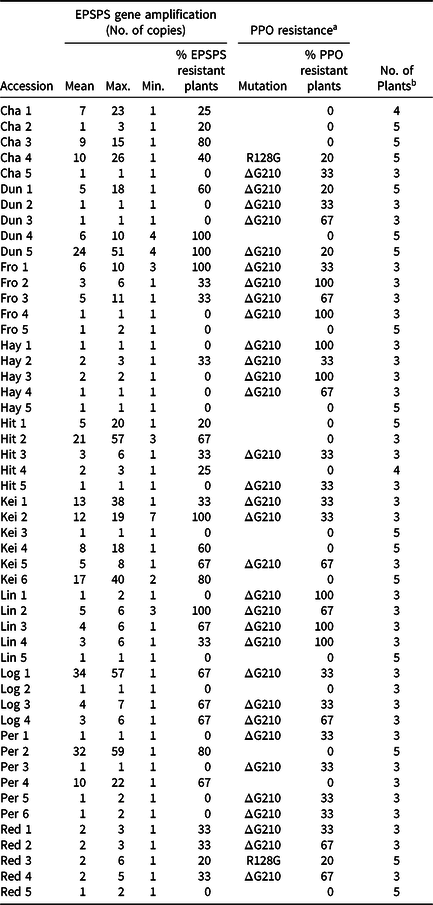

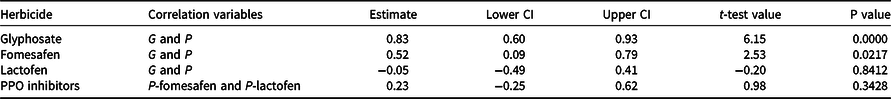

Increased EPSPS copy number was detected in 63% of the 51 Palmer amaranth accessions analyzed (Table 2). Based on EPSPS gene amplification, our study showed that 10% of Palmer amararanth accessions had all individuals resistant to glyphosate, 53% were segregating for resistance, and 37% were susceptible to glyphosate (Table 2). Phenotypic analysis of 19 of these accessions confirmed the genotypic analysis data, in that a positive correlation (0.83; P-value = 0.0000) was observed between G and P assays (Figure 1 and Table 3). The high correlation between G and P for glyphosate resistance demonstrates that most Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska are resistant to glyphosate due to EPSPS gene amplification. The EPSPS gene amplification mechanism is widespread in Palmer amaranth (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Patterson and Neve2019; Sammons and Gaines Reference Sammons and Gaines2014). Gene amplification is an important evolutionary mechanism enabling weeds (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Pettinga, Ravet, Neve and Gaines2018) and other pests (Bass and Field Reference Bass and Field2011; Remnant et al. Reference Remnant, Good, Schmidt, Lumb, Robin, Daborn and Batterham2013) to evolve resistance to pesticides. Palmer amaranth was the first identified weed to evolve glyphosate resistance via EPSPS gene amplification (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010), followed by kochia (Bassia scoparia L. A.J. Scott), waterhemp, Italian ryegrass (Lolium perenne L. ssp. multiflorum), ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus Roth), goosegrass (Eleusine indica L.), windmill grass (Chloris truncata R. Br.), and smooth pigweed (Amaranthus hybridus L.; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Pettinga, Ravet, Neve and Gaines2018; Sammons and Gaines Reference Sammons and Gaines2014). Other glyphosate resistance mechanisms have also been confirmed in Palmer amaranth, including a Pro106 mutation in the EPSPS gene and reduced glyphosate absorption/translocation (Dominguez-Valenzuela et al. Reference Dominguez-Valenzuela, Gherekhloo, Fernández-Moreno, Cruz-Hipolito, Alcántara-de la Cruz, Sánchez-González and De Prado2017; Palma-Bautista et al. Reference Palma-Bautista, Torra, Garcia, Bracamonte, Rojano-Delgado, Alcántara-de la Cruz and De Prado2019; Sammons and Gaines Reference Sammons and Gaines2014).

Table 2. Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska with EPSPS gene amplification and/or PPO resistance according to genotypic resistance assays in parent individuals.

a Empty cells in the “PPO resistance” column indicate no PPO-inhibitor resistance mutation detected.

b Number of plants screened in the genotypic herbicide resistance assay.

Figure 1. Validation between glyphosate resistance via genotypic (EPSPS gene amplification in parent) and phenotypic (glyphosate treatment in progeny) assays in Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska. Color-coded dots indicate three clusters for glyphosate resistance: susceptible (S), moderately resistant/susceptible (M), and resistant (R). Size-coded dots to represent the average EPSPS copy number for each Palmer amaranth accession.

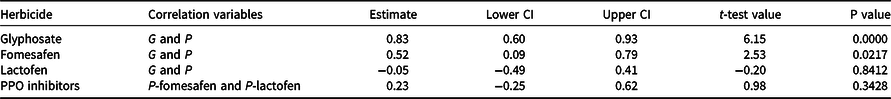

Table 3. Correlation estimates between Palmer amaranth genotypic (parent) and phenotypic (progeny) results toglyphosate, fomesafen, and lactofen, and between phenotypic fomesafen and phenotypic lactofen results (PPO inhibitors).a

a Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; G, genotypic (parent); P, phenotypic (progeny); PPO, protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase.

The k-means strongly classified Palmer amaranth into three clusters, herein described as S (susceptible), M (moderately resistant/susceptible), and R (resistant) accessions (Figure 1). Palmer amaranth accessions classified as S showed no EPSPS gene amplification in the genotypic assay, but two accessions had individuals that survived glyphosate (870 g ae ha−1) application (>15%) in the whole-plant phenotypic assay (Figure 1). For example, these two accessions showed low (P = 18%, Hay 1) and moderate (P = 35%, Hay 4) survival after glyphosate treatment in the phenotypic assays but four accessions (Dun 3, Hay 3, Log 2, and Kei 3) tested negative (G = 0%) for glyphosate resistance in the genotypic assay and showed P ≤15% in the phenotypic assays. In addition, nine accessions were correctly classified as R, having high G and P values (Figure 1). Two Palmer amaranth accessions were correctly classified as M (Red 2 and Per 4) but not the Red 4 (P = 80%, G = 33%) and the Red 5 accession, which showed high survival (P =75%) after glyphosate treatment despite having G = 0%. Other glyphosate resistance mechanisms are likely present in accessions investigated herein. It remains unknown whether the Red 5 accession, which has no EPSPS gene amplification (G) but high number of progeny surviving glyphosate application (P), harbor additional resistance mechanisms, warranting further investigations.

Our results suggest that genotypic assays represents a robust tool for rapid detection of glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska, and likely other geographic areas. The use of genotypic assays is possible largely due to the widespread occurrence of EPSPS gene amplification as the mechanism of glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth populations. Research on the molecular basis of EPSPS gene amplification in weed species is underway because additional work is needed to unveil this complex adaptative trait (Koo et al. Reference Koo, Molin, Saski, Jiang, Putta, Jugulam, Friebe and Gill2018). The genetics of EPSPS gene amplification in weed species follows Mendelian inheritance in kochia (Jugulam et al. Reference Jugulam, Niehues, Godar, Koo, Danilova, Friebe, Sehgal, Varanasi, Wiersma, Westra, Stahlman and Gill2014), and non-Mendelian inheritance patterns in Palmer amaranth (Giacomini et al. Reference Giacomini, Westra and Ward2019) and ripgut brome (Malone et al. Reference Malone, Morran, Shirley, Boutsalis and Preston2016). More than 100 EPSPS gene copies have been documented in Palmer amaranth, whereas a maximum of 13 have been observed in kochia (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Barker, Patterson, Westra, Westra, Wilson, Jha, Kumar and Kniss2016; Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Jha, Giacomini, Westra and Westra2015; Wiersma et al. Reference Wiersma, Gaines, Preston, Hamilton, Giacomini, Robin Buell, Leach and Westra2015). The EPSPS gene copy variation in Palmer amaranth is a result of the extrachromosomal circular DNA (eccDNA) being transmitted to the next generation by tethering to mitotic and meiotic chromosomes (Koo et al. Reference Koo, Molin, Saski, Jiang, Putta, Jugulam, Friebe and Gill2018), while in kochia, EPSPS copies are arranged in tandem repeats at a single locus (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Pettinga, Ravet, Neve and Gaines2018). Segregation for EPSPS copy number within Palmer amaranth families (F1 and F2) is transgressive, with individuals varying in EPSPS gene amplification levels even among clonal plants (Giacomini et al. Reference Giacomini, Westra and Ward2019). Transgressive segregation for EPSPS in Palmer amaranth might explain the variable EPSPS copy numbers across individuals within accessions screened from southwestern Nebraska (Table 2). Gene amplification coupled with its prolific and dioecious nature are valuable traits for Palmer amaranth that help to increase its genetic complexity and allow it to adapt to current U.S. cropping systems.

PPO-Inhibitor Resistance

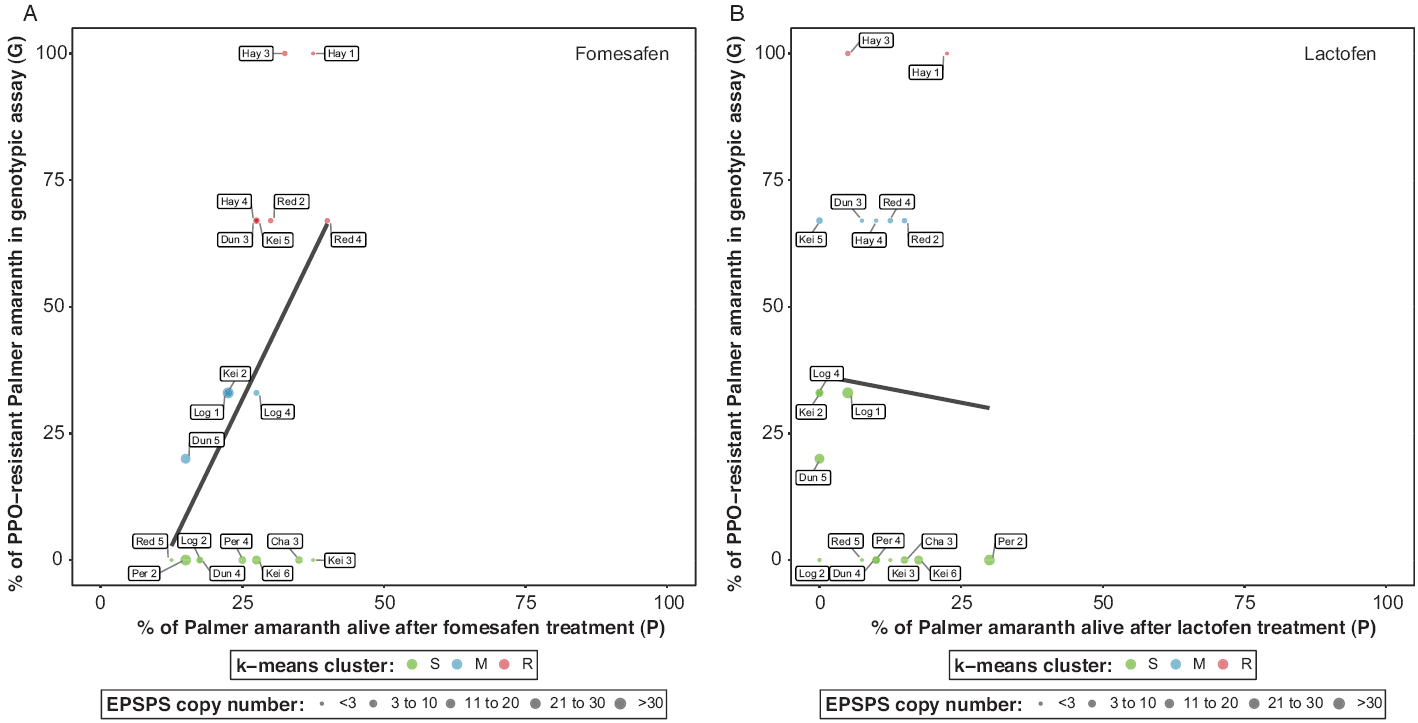

The genotypic assays showed nearly 70% of the 51 Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska were confirmed to be resistant to PPO-inhibitor herbicides (Table 2). Nearly 14% of Palmer amaranth accessions had all individuals resistant, 53% were segregating for resistance, and 33% had no mutation. In the phenotypic assays, fomesafen and lactofen treatments resulted in less than 40% survival within each Palmer amaranth accession (Figure 2). Thus, the correlation between G and P for PPO-inhibitor resistance in Palmer amaranth accessions was inconsistent (Table 3). While a higher G and P correlation (0.52; P-value = 0.0217) was observed for fomesafen (Figure 2A), no G and P correlation (−0.05; P-value = 0.84) was found for lactofen (Figure 2B). In addition, there was no correlation (0.23; P-value = 0.34) between fomesafen (P) and lactofen (P) in the phenotypic assay (Table 3). Application of fomesafen (226 g ai ha−1) and lactofen (219 g ai ha−1) provided high mortality (P < 50%) in Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska, including accessions wherein 100% of individuals had a ΔG210 deletion (e.g., Hay 1 and Hay 3). Moreover, high Palmer amaranth mortality with PPO-inhibitor herbicides negatively influenced the clustering algorithm of Palmer amaranth as S, M, and R accessions (Figure 2, A and B). The k-means likely classified these accessions based on G results only. For example, Palmer amaranth accessions were classified as S, M, and R for fomesafen with G = 0%, 20% ≤ G < 35%, and G ≥ 66%, respectively; however, P of all three clusters varied between 12% and 40% (Figure 2A). A similar trend was observed for lactofen (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Validation between protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase (PPO) resistance via genotypic (ΔG210 mutation in parent) and phenotypic [fomesafen (A) and lactofen (B) treatment in progeny] assays in Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska. Color-coded dots to indicate three-cluster analysis for PPO-inhibitor resistance: susceptible (S), moderately resistant/susceptible (M), and resistant (R). Size-coded dots represent the average EPSPS copy number for each Palmer amaranth accession.

Palmer amaranth accessions Dun 5 (20%), Kei 2 (33%), Kei 5 (67%), and Log 4 (33%) were segregating for PPO-inhibitor resistance in the genotypic assay (G, Figure 2B); however, the progeny of these accessions were sensitive to lactofen treatment (P = 0%). In contrast, Palmer amaranth accessions Cha 3, Kei 6, Per 2, and Red 5 tested negative for ΔG210 or R128G mutations (G = 0%) but more than 15% of the individuals survived both fomesafen and lactofen treatment. Also, Palmer amaranth accessions Kei 3, Per 4, and Dun 4 showed 38%, 25%, and 18% survival, respectively, after fomesafen treatment but less than 15% survival after lactofen treatment. It has been shown that a mutated PPO enzyme has reduced affinity for several PPO-inhibitor herbicides in Palmer amaranth (Schwartz-Lazaro et al. Reference Schwartz-Lazaro, Norsworthy, Scott and Barber2017); however, it has been difficult to determine Palmer amaranth resistance based on field survival because sensitive plants could tolerate PPO-inhibitor herbicides (Lillie et al. Reference Lillie, Giacomini and Tranel2020). In addition, PPO-inhibitor herbicide efficacy on PPO-resistant Pamer amaranth control can be influenced by application time (Copeland et al. Reference Copeland, Montgomery and Steckel2019). Therefore, confirmation of Palmer amaranth resistance to PPO-inhibitor herbicides using phenotypic assays is complex and needs further investigation.

In the 34 PPO-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth accessions tested herein, 32 presented the the ΔG210 in the PPX2 gene, while the R128G mutation was confirmed in two Palmer amaranth accessions. The phenotypic validation for PPO-inhibitor resistance presented here is limited by the high mortality of Palmer amaranth individuals in the whole-plant assays. This could be explained by 1) the number of individuals sampled for the G assay study may have been too low for the objective of validation; 2) the herbicide rate used herein resulting in high individual mortality; 3) greenhouse conditions were ideal and plants faced no environmental stress during and following application of PPO-inhibitor herbicides, which is different for plants under field conditions in southwestern Nebraska; and 4) plant size strongly impacts the level of resistance, with smaller plants being less resistant than larger plants (Coburn Reference Coburn2017). It is likely that Palmer amaranth individuals used herein were smaller than usual because of the small volume of the cone-tainers, which limits root and shoot development. Hence, the whole-plant bioassays failed to confirm resistance to PPO-inhibitor herbicides in Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska, making genotypic assays a necessary step for resistance confirmation.

Random Forest: Classification of Factors Influencing Glyphosate Resistance

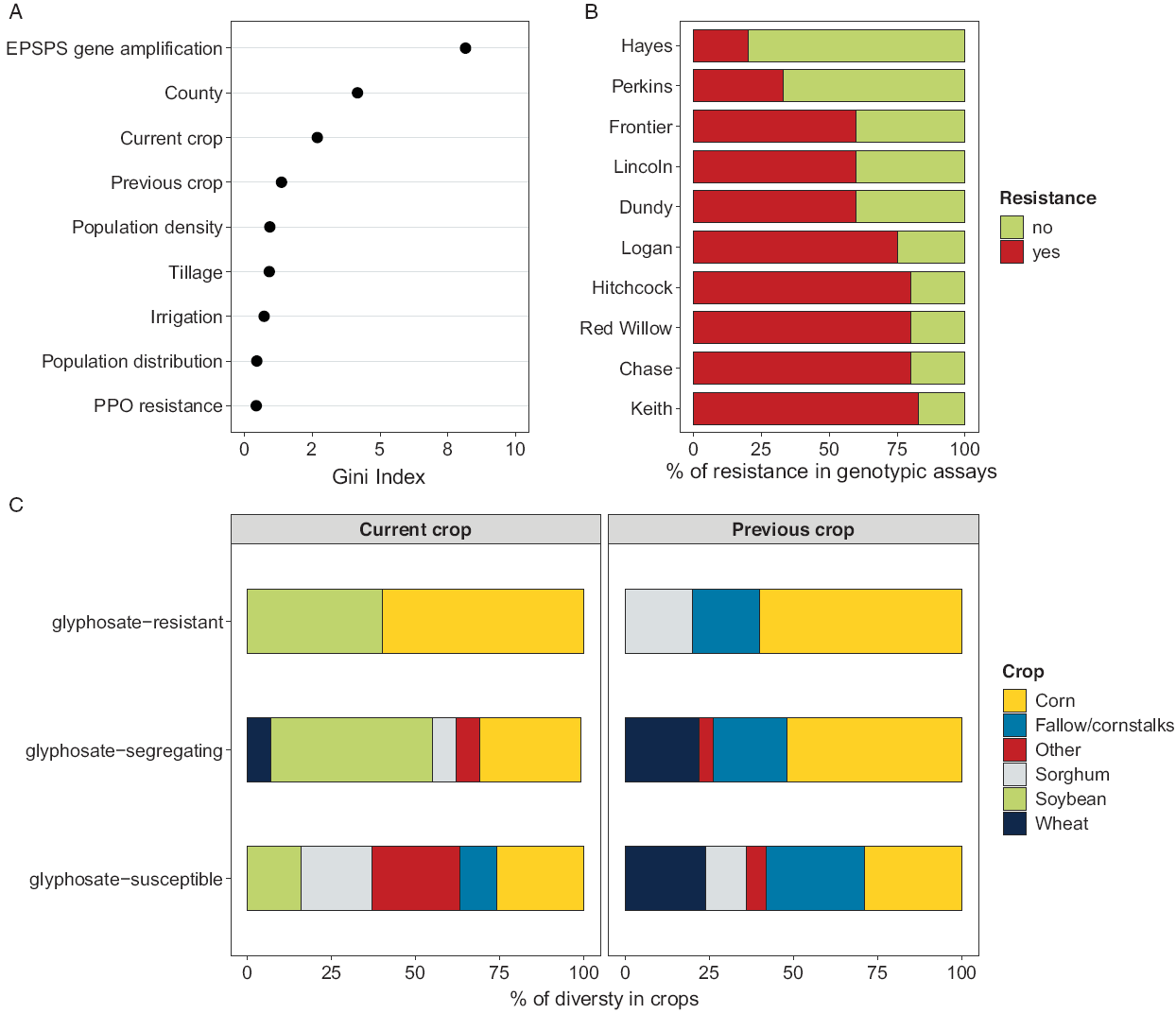

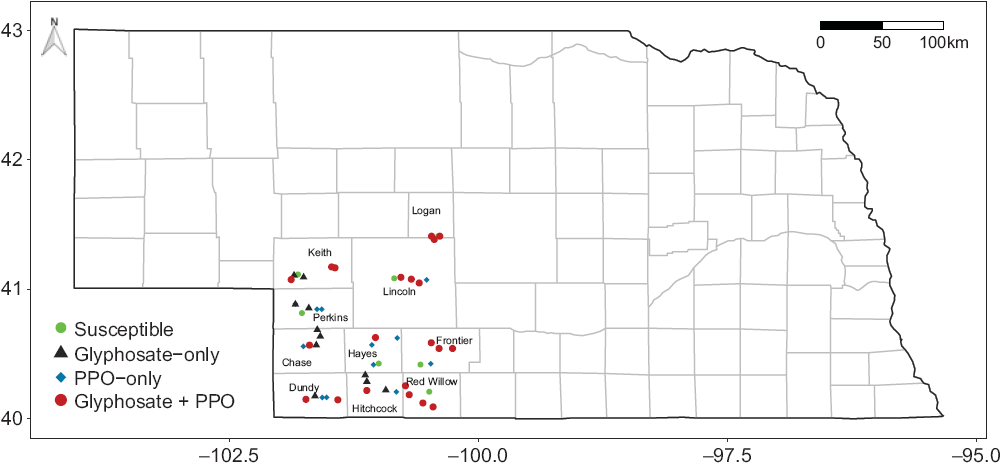

The final OOB error rate of the random forest analysis was 13.33%, meaning that >86% of OOB samples were adequately classified by the model. Results showed EPSPS gene amplification as the top predictor (Figure 3A). This highlights the robustness of the approach, with GR Palmer amaranth accessions in southwestern Nebraska containing this mechanism of resistance. In 2014, a survey with Amaranthus spp. in Nebraska confirmed widespread glyphosate resistance for waterhemp (81%) but not for Palmer amaranth (6%; Vieira et al. Reference Vieira, Samuelson, Alves, Gaines, Werle and Kruger2018). Vieira et al. (Reference Vieira, Samuelson, Alves, Gaines, Werle and Kruger2018) demonstrated the spread of waterhemp in eastern Nebraska, and Palmer amaranth in south central Nebraska, which partly overlaps territory with Palmer amaranth accessions surveyed herein (Figure 4). The rapid glyphosate resistance evolution in Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska raised questions about whether resistant accessions were introduced via seed/gene flow or they arose independently. Although we did not test this specific hypothesis, the random forest analysis did shed some light on glyphosate resistance evolution in Palmer amaranth in that part of Nebraska. The random forest analysis ranked (high to low) EPSPS gene amplification > county > current crop > previous crop > Palmer amaranth density > tillage > irrigation > Palmer amaranth distribution > PPO-inhibitor resistance as the factors influencing the presence of glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth of southwestern Nebraska (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Random forest analysis of likelihood of glyphosate resistance (EPSPS gene amplification >2) in parental Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska. Variables are ordered by importance measured using the Gini coefficient (A). Percentage of glyphosate resistance (genotypic assay) in Palmer amaranth across 10 counties in southwestern Nebraska (B). Percentage of diversty in current and previous crop where the Palmer amaranth accessions was detected in southwestern Nebraska. Based on genotypic resistance assay, accessions are grouped into glyphosate-resistant, glyphosate-segregating, and glyphosate-susceptible, representing Palmer amaranth with all resistant, mixture of resistant and susceptible individuals, and all susceptible individuals, respectively. Other crops are represented by alfalfa, dry bean, and field pea (C).

Figure 4. Presence of glyphosate and/or protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase-inhibitor resistance based on genotypic resistance assay in 51 parental Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska. County names are listed within their territory.

County was the second most important factor for the presence of GR Palmer amaranth. All counties presented at least one Palmer amaranth individual with EPSPS copy number >2. The lowest number of GR accessions was found in Hayes (Hay) and Perkins (Per) counties with one (out of five) and two (out of six), respectively (Figure 3B). County influence on EPSPS-inhibitor resistance in Palmer amaranth is likely related to crop diversity as current and previous crops strongly influenced the presence of glyphosate resistance in Palmer amaranth accessions. Five Palmer amaranth accessions (Dun 4, Dun 5, Fro 1, Kei 2, and Lin 2) demonstrated 100% resistance (grouped as glyphosate-resistant) and those accessions were all found in fields where current corn or soybean crops were preceded by corn or sorghum (Figure 3C). The high incidence of Palmer amaranth accessions with 100% resistance to glyphosate in less diverse cropping systems suggests the influence of repeated glyphosate applications. In contrast, EPSPS gene amplification was not detected in 19 Palmer amaranth accessions (grouped as glyphosate-susceptible), from which only two accessions were found in corn and soybean rotations (Fro 5 and Hit 5; Table 2). The majority of glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth accessions were found in rotations of corn, sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), fallow, soybean, and other crops (e.g., alfalfa [Medicago sativa L], dry bean [Phaseolus vulgaris L], and field peas [Pisum sativum L]; Figure 3C). Therefore, the occurrence of GR Palmer amaranth accessions is reduced in rotations with more diversified crops, most likely due to crop and herbicide rotations with lower reliance on glyphosate. For example, according to a survey, 2,4-D and metsulfuron-methyl are the most used POST herbicides in grain sorghum and wheat crops, respectively, in Nebraska (Sarangi and Jhala Reference Sarangi and Jhala2018). Crop diversity exerts a different selection pressure on weed communities, including planting, canopy closure timing, and harvest date, which help reduce the dominance of single weed species (Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Satorre, Ermácora and Poggio2017). Despite not having long-term herbicide application records for the areas we sampled from, it has been demonstrated that overreliance on a single or few herbicide SOA in areas with low crop diversity contributed to resistance (Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, Comont, Coutts, Crook, Hull, Norris, Neve, Childs and Freckleton2018). In addition, it has been shown that herbicide mixture (multiple SOA in one application) is more effective in delaying herbicide weed resistance than herbicide rotation (multiple applications, each with a single SOA; Beckie and Reboud Reference Beckie and Reboud2009, Evans et al. Reference Evans, Tranel, Hager, Schutte, Wu, Chatham and Davis2016). However, without herbicide mixtures and rotations, increased crop diversity alone is not enough to minimize herbicide resistance evolution in weed species.

The random forest analysis suggested that PPO-inhibitor resistance had no influence on glyphosate resistance, indicating that PPO-inhibitor resistance mutations (ΔG210 or R128G) and EPSPS gene amplification are not associated. An emerging concern in weed science is the ability of some species to stack genes for multiple herbicide resistance in a single accession. Accessions of Palmer amaranth have been reported to be resistant to HPPD-inhibitor herbicides (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014), PSII-inhibitor herbicides (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014), and glyphosate herbicides (Chahal et al. Reference Chahal, Varanasi, Jugulam and Jhala2017) in Nebraska. According to our genotypic assay results, multiple resistance (glyphosate and PPO-inhibitor herbicides) was present in 41% of Palmer amaranth accessions in southwestern Nebraska (Table 2); while 6%, 11%, and 13% of accessions were susceptible to both herbicides, resistant to glyphosate only, and resistant to PPO-inhibitor only, respectively (Figure 4). The 19 Palmer amaranth accessions evaluated in the whole-plant phenotypic assay were also resistant (>80% of individuals within each accession) to an ALS-inhibitor herbicide (imazethapyr at 70 g ai ha−1; data not shown). Thus, it is likely that two- and three-way resistance exists in most Palmer amaranth accessions from southwestern Nebraska.

Practical Implications

Herein we documented the distribution of GR and PPO-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth accessions in southwestern Nebraska (Figure 4). Rapid genotypic assays are important for detection of known mutations to support growers in making future weed management decisions. Glyphosate resistance via EPSPS gene amplification was highly correlated to whole-plant phenotypic assay results, mostly due to the spread of EPSPS gene amplification as the mechanism of resistance in Palmer amaranth accessions. These result supports the use of either genotypic or phenotypic assays for confirmation of glyphosate resistance in southwestern Nebraska. PPO-inhibitor resistance was also present in several accessions, but phenotypic results were less correlated with the confirmed PPO-inhibitor resistance mutations, showing the complexity of resistance confirmation with whole-plant phenotypic assays, warranting the use of genotypic assays for PPO-inhibitor resistance confirmation. Still, weeds will continue to evolve resistance to herbicides, and whole-plant phenotypic assays are fundamental for detecting populations with novel herbicide resistance mechanisms. For example, the G399A PPO mutation was not known at the time this research was conducted, and may be present in some accessions studied herein. Moreover, the GR Palmer amaranth accessions were found in crops where glyphosate was likely applied, suggesting resistance evolution was mostly due to an overreliance on glyphosate. Great progress has been made toward understanding the molecular basis of herbicide resistance in Palmer amaranth, but the continuous spread of herbicide resistance to new locations is evident. Thus, increased crop rotation and diversity, rotation of herbicide mixtures, and adoption of innovative nonchemical control strategies are necessary for Nebraska and other geographic locations to minimize selection and spread of herbicide-resistant weed populations.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency. We appreciate the help of Liberty Butts, Victor Ribeiro, and Dr. Bruno Vieira for their assistance with the field sample collection, greenhouse projects, and data analysis, respectively. The authors declare no conflict of interest.