Introduction

Tourists crossing the Tiber on the Ponte Sant’Angelo, on their way to St Peter’s, and Romans in their cars crawling through the traffic of the Lungotevere would barely notice a large triangular building nestled between the majestic brick rotundity of the Castel Sant’Angelo and the overblown neoclassical monumentality of the Palazzo di Giustizia (affectionately known as the Palazzaccio). It is the Casa Madre dei Mutilati, the headquarters of the Associazione Nazionale Mutilati e Invalidi in Guerra (ANMIG – the National Association of War Wounded) designed by Marcello Piacentini, both built and decorated in two phases between 1926 and 1928 and from 1936 to 1939. Thanks to Piacentini’s clever approach to urban context, the architecture’s external form blends in seamlessly with its surroundings, suggesting that it no longer has the power to conjure memories of the Fascist regime or the war wounded (Figure 1). The epigraphy, a series of Latin mottos curated by association president Carlo Delcroix, are too obscure for most passers-by to decipher or understand.

Figure 1 The Casa Madre dei Mutilati in Rome, (L to R) exterior with Palazzaccio in background and with Castel Sant’Angelo in background (author’s photographs, 2015).

Once inside, its decorative scheme reveals another story. From the subtle interpretation of the mutilated St Sebastian that looks forlornly down at visitors ascending the stairs of the main hall, to the highly charged frescoes of the king and Duce on horseback in the building’s more secret and more ‘sacred’ basement, it represents varying degrees of explicit meaning in its celebration of the Fascist era and its warlike culture. This has meant that in post-Fascist times, when the decorative schemes of other buildings of the preceding era were often ‘cleansed’ of overt Fascist meaning, most of the works in the Casa Madre remained untouched, thanks to their polyvalent meanings and less direct references to Fascism. Others were touched up, let pass or deliberately censured and obscured, only to be uncovered and celebrated in the late 1980s.

A society’s memory is both individual and collective: it is negotiated in the beliefs and values, rituals and institutions of the social body and shaped by public sites such as museums, memorials and monuments (Huyssen Reference Huyssen1994, 9; Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1992, 169). As Halbwachs has stated: ‘Depending on its circumstances and point in time, society represents the past to itself in different ways: it modifies its conventions. As every one of its members accepts these conventions, they inflect their recollections in the same direction in which collective memory evolves’ (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1992, 172–173). What happens when those beliefs and values are overturned or negated by a change in political regime? How does a country’s collective memory evolve when rituals take on a negative meaning and the institutions that support them no longer exist? If buildings and monuments are, as Young suggests, a matrix that emplots a story of ennobling events that define both individual and national identity (Young Reference Young1993, 2), then what of the institutions created independently of Fascism that were temporarily co-opted and then left to rebuild themselves and their identity?

After its transition from Fascist to antifascist nation Italy faced a conundrum made manifest by the conflation of heritage and identity (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1994, 41). The heritage of the ventennio (the Italian Fascist period) was created to address the common needs and embody the common traits of a Fascist nation, and much has been written about how post-Fascist society has dealt with these social and political changes. This article asks what happens when needs, traits and accompanying rituals endure across political regimes? And what happens to the art and the architecture that embody them?

The Casa Madre dei Mutilati was more than the headquarters of ANMIG: its president Carlo Delcroix called it a ‘fortress and temple’, a place for ‘battle and prayer’ (Dobler Reference Dobler2010, 2). Italy’s post-First World War monuments were given new layers of significance by the Fascist regime (Dogliani Reference Dogliani1992; Hökerberg Reference Hökerberg2017). The aftermath of the First World War was a shifting social and political landscape marked by the parallel rise of Fascism and the continued momentum of nationalism. They found a common emotional and political ground on which to build support based on worship of nation, patriotism and victory and its allied imagery of masculinity and strength. These notions were integral to the depiction of war veterans and were later integrated into Fascist ideology (Foot Reference Foot2011, 37).

Founded in Milan in 1917 by independent groups of First World War veterans, ANMIG was brought under the auspices of the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista – PNF) in 1938. Delcroix was himself both mutilato (mutilated/wounded) and invalido (with a disability): after studying law, he had campaigned for Italy’s entry into the First World War, then volunteered. After the war he travelled through Italy and Latin America delivering propaganda speeches to win war veterans over to the Fascist cause. Like d’Annunzio before him and Mussolini after him, Delcroix knew how to sway a crowd (Mosse Reference Mosse1980, 94–98). Although Delcroix’s allegiance to Fascism was at times ambivalent (he waited until 1928 to join the PNF and was arrested in 1943 for antifascist activities) he saw Mussolini as a new brand of politician who shared his belief in war and nationalism. While ANMIG was looking for a political force to meet its needs, Mussolini was looking for consolidated groups of followers. By 1922 ANMIG numbered 500,000 members and had published a manifesto declaring itself ‘in the service of the Fatherland’ – and the deal had been sealed (Cannistraro Reference Cannistraro1982, 161–200; Albertina Reference Albertina1988; Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi1999, 86). Mussolini recognised ANMIG as the only legitimate association of mutilati and made sure that each region of Italy had its own casa dei mutilati: the one in Rome was known as the Casa Madre (Mother House).

Each casa dei mutilati provided material support and symbolised, through its art and its architecture, a new and redefined role in society for all its members (Delcroix Reference Delcroix1928a, 195–197). Because they needed care for both body and spirit their political potential could be leveraged. They also needed an identity that went beyond culture, tradition, nation or ethnic group (Handler Reference Handler1994, 27). The Casa Madre, along with its decorative plan, played a crucial role in constructing this identity by giving it material, visual, spatial and – most importantly – experiential form.

Although it predated Fascism, ANMIG was brought into the climate of cultural interventionism and associationism that was driven, on the one hand, by a desire to shape and mould from above and, on the other, to attract as many people as possible (Forgacs and Gundle Reference Forgacs and Gundle2007, 268). During the Fascist period Delcroix’s efforts were co-opted by the Fascist party and ANMIG played an important role in the consent-building process as a supporter of the regime through its various phases. Soldiers supported the belligerent aspects of Fascist culture and propaganda, helping to perpetuate a warlike climate throughout the ventennio, beginning with cults around war dead and the ‘martyrs of the revolution’ and continuing into economic policies like the ‘Battle for Grain’ (Battaglia del Grano) and the autarky policy, implemented after 1936 when League of Nations sanctions were imposed on Italy for invading Ethiopia. The climate of war was perpetuated with aggressive foreign policy decisions: nearly 80,000 ‘volunteers’ sent to support Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939); the alliance with Nazi Germany (1938); the annexation of Albania in 1939; the declaration of war against France and Great Britain (1940); and the final, fateful invasion of Greece in 1941. This climate of war found visual and material expression in propaganda-inspired art conceived as part and parcel of architecture. The Casa Madre is but one example.

The post-Second World War period was marked by pacifism, antifascism and a commitment to never repeat the horrors of Italy’s triple war, in which the country had been both ally and enemy of Germany and then the scene of the civil war that followed. This did not obliterate or deny the social importance of mutilati and ex-servicemen whose needs, traits and rituals had endured through the change of regime. In the postwar period ANMIG sat between the efforts of the Catholic Church and the Italian Communist Party to fill the vacuum left by associations created under the Fascist regime to facilitate, increase and underpin consent (De Grazia Reference De Grazia1981; Forgacs and Gundle Reference Forgacs and Gundle2007, 247–268). Despite its former alliance with Fascism, ANMIG was exonerated from antifascist sentiment by connecting itself with Resistance myths so crucial to the rebuilding of Italian identity in the post-Fascist period. Martyrdom and sacrifice for the nation were much honoured, whether forged under the banner of continued war and Fascist-nationalism, or under the banner of peace and antifascist nationalism.

Afterlife of Fascism studies have followed on the heels of scholarship on the Fascist period and its many aspects of cultural production. Historical distance has made it acceptable to appreciate art and architecture with explicitly Fascist meaning and observe their pictorial quality and artistic value. We can now see them through the lens of the time, as material remains of a culture that cannot be erased and needs to be kept as a reminder of the past. However, questions about the role and meaning of more obviously charged Fascist art and architecture continue to arise, and the case dei mutilati merit more exploration under the topic of difficult heritage, to better understand how the tension between apparently unacceptable content for a contemporary audience and acceptable historic artistic expression can be resolved (Benton Reference Benton2010, 148). Italian art and architecture from between the wars are no longer automatically labelled as ‘Fascist’. They are now recognised both by the Italian government and heritage agencies as something to be preserved and restored. They are promoted as an attraction to tourists and the general public without fear of Fascist labelling, which is often underplayed.

The role played by fine art as propaganda has been reluctantly acknowledged by both historians and the public due to a rigid dichotomy dividing it from propaganda art (Pieri Reference Pieri2013a, 160 and Pieri Reference Pieri2013b, 227–228). Because it is an integral part of the architecture, fresco and mural art blurs, or rather ignores, this boundary. As Mario Sironi and fellow artists like Achille Funi and Carlo Carrà believed: ‘Art assumes a social function in the Fascist state: an educational function.’ Of all the art forms, ‘mural painting is social painting, par excellence. It works upon the popular imagination more directly than any other form of painting’, and is tied to ‘the practical nature of sites for murals (public buildings, places endowed with civic functions)’ and their ‘intimate relation to the art of architecture …’ (Sironi 2004 [Reference Sironi1932]). The 1999 exhibition Muri ai Pittori (‘Let walls be for painters’) held in Milan was a milestone in the consideration of artists’ direct intervention on the collective imagination with the aim of promoting the Fascist regime (Fagone, Ginex and Sparagni Reference Fagone, Ginex and Sparagni1999).

While Fascist art all but disappeared from the critical radar until the early 1980s, no substantial body of images of Mussolini was shown to the public until the 1997 L’uomo della Provvidenza. Iconografia del Duce (1923–1945) exhibition in Seravezza. It is still difficult for Italians to be confronted with images of their former leader, since they stand as material evidence of his cult and popularity, and it is even more difficult when these images belong to the realm of high art and were produced by some of Italy’s best twentieth-century artists (Pieri Reference Pieri2013b, 229–230; Petacco Reference Petacco2009). The erosion of public consensus can also lead to a counter-cult of the Duce, implying a certain level of public acceptance (Pieri Reference Pieri2013b, 236). There is a nostalgia cult of Mussolini fuelled by neo-Fascist groups and sympathisers that never really went away and which is facilitated by the ‘democratisation’ of information via the internet.

The material form of Fascist-era art and architecture stands in contrast to the absence of public memories and, generally speaking, it mirrors the selections, omissions and revisions of the postwar historical narrative (Malone Reference Malone2017, 446–447; Maulsby Reference Maulsby2014, 29). It can be destroyed, neglected or reused (Malone Reference Malone2017), aestheticised or erased (Benton Reference Benton2010, 156), but the Casa Madre is more complex: it straddles categories and demonstrates how public memory can be kept separate and allowed continuity. The Casa Madre manages the ‘bad’ memories associated with Italy’s Fascist regime by reclaiming its original meaning for its specific group in society – the mutilati. The Casa Madre went from ‘fortress and temple’ for injured war veterans and their families to national symbol of a belligerent nation to boost larger propaganda efforts and back again. The only part of the Casa Madre subject to critical condemnation was the Sacrario (shrine) with Sironi’s equestrian portraits of Mussolini and the king, which were covered up until 1988 and which are now celebrated as the building’s main attraction and claim to fame. The Cortile della Vittoria frescoes by the less famous Antonio Santagata have, until only recently, suffered condemnation through neglect (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Frescoes by Antonio Santagata and Cipriano Efisio Oppo under the colonnade of the Cortile della Vittoria (top). The colonnade of the Cortile and the apse of the Salone delle Adunate showing arengario with eagle bas-relief by Ettore Colla (below).

This article is about the evolution of a building’s decorative plan as an embodiment and expression of identity and meaning for a specific group in society that extends to broader contexts. The building’s form and material, the epigraphy on its façade and its art were conceived for a community of wounded war veterans and their families. They were then modified and amplified to suit the broader propaganda messages of the regime. After the war, they reverted to their original meaning and took on subtle messages of antifascist struggles by promoting continuity on the one hand and concealing what was overtly Fascist on the other.

Both construction and decoration were carried out in two phases. Plans for expansion of the Casa Madre were made in 1933 and by 1938 the building had nearly doubled in size to accommodate more offices, a chapel, and spaces for the spectacle and ritual of the Fascist regime, such as the Sacrario and the Cortile della Vittoria. The first phase of the decorative programme (1928–1932) celebrated the collective role played by wounded war veterans in the creation and continuation of a new, Fascist society; the second (1936–1939) promoted empire, glorified war and celebrated individual leadership. Spaces closely linked to Fascist ritual activities in overtly political buildings like the case del fascio were significantly altered after the Second World War (Maulsby Reference Maulsby2014, 29) whereas the Casa Madre’s main ritual space – the Salone delle Adunate – remained unchanged, while the Sacrario downstairs was converted into an archive soon after the war, its frescoes first censured and then ‘censored’ by concealing them with thin wall panels.

The Casa Madre dei Mutilati

The Casa Madre dei Mutilati is not immediately identifiable as a Fascist-style building: it is typical of a late-1920s-style architecture in the Roman tradition. Its compact triangular form responded to the shape of the site, with office spaces arranged symmetrically around a central meeting hall and ritual space – the Salone delle Adunate. This double-height space was accessed via a grand ceremonial stair and combined a Greek cross church plan with a majestic cross-vaulted ceiling inspired by the Basilica of Maxentius and the upper halls of Trajan’s markets. It was also conceived, designed and built at a time before the regime was consciously leveraging architecture as a tool for propaganda (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei1993b, 107). Italian architecture of this time was as much a chameleon as Fascist ideology. After the calls by the Futurist movement to refute the past, it transitioned from the quietly classical Novecento style to a uniquely Italian interpretation of northern European modernism, known as Rationalism. It represented a forward-thinking and revolutionary new nation until the mid-1930s,when it reverted to the classical tradition that was as severe, monumental and overbearing as the repressive, imperialist and anti-semitic regime it represented (Marcello Reference Marcello2017).

Decorative schemes heightened the experience of architecture and vice-versa, and their seamless integration was crucial to their communicative power. Architecture was both container for ritual and frame for decorative schemes of frescoes, paintings, bas-reliefs, statues and epigraphy. From the Casa Madre’s inception, art and architecture were considered as a synthetic totality to trigger an emotional response in both users of the building and passers-by. Today, the building sits in what is essentially a traffic roundabout for those driving south along the Lungotevere, and its original meaning persists only for an ever-dwindling group of people. It is still the headquarters for ANMIG, with more than half the building occupied by government offices. The Cortile della Vittoria no longer gathers adoring crowds – it is used as a car park.

The 1928-1932 decorative programme

It was important for Delcroix that as many artists as possible involved in the decoration of the Casa Madre were also mutilati, because decorating their own temple/fortress gave value to their continued role in society (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei1993a, 27). Santagata, nicknamed ‘the soldiers’ Giotto’ by Delcroix, continued to work closely with ANMIG on case dei mutilati around the country, including those in Ravenna, Genova, Palermo and Milan.

Delcroix made frequent references to sacrifice, religion and ritual in his writings, equating the ideals of war, battle and politics to a religion (Danesi-Squarzina Reference Danesi-Squarzina1993, 73). It is no surprise that he implemented a decorative plan similar to those used in churches – statues of martyrs, apse frescoes and doors with bronze bas-reliefs narrating stories of Christ or other saints. These, along with the majestic apse in a Greek cross plan, were common and recognisable elements of churches all over Italy, thus helping to guarantee its ‘survival’ in the post-Fascist period. A 1932 book entitled Mussolini e l’arte described how ‘Each architectural and decorative detail [of the Casa Madre] revealed the ardour of our conquests and the painful efforts of our victory that are consecrated in the purest and highest forms of art ... The cult of images is familiar to our people and it is therefore natural that there be artistic interpretations of crucial facts and events in all parts of Italy’ (Sapori Reference Sapori1932, 112).

The Casa Madre was inaugurated on 4 November 1928 – the tenth anniversary of the battle of Vittorio Veneto. The Istituto Luce newsreel of the ceremony showed Mussolini, the King and Piacentini looking up at the main entrance portal, over which was emblazoned the motto of the organisation, ‘Deo et patria noscimur’ (Recognised/acknowledged by God and the Fatherland) (Sinistri Reference Sinistri1928). After a parade by mutilati, they were accompanied by Delcroix, together with crowds of officials and special guests, into a small vestibule to be shown two herm statues of wounded heroes by Adolfo Wildt. A little further on, they admired a marble bust of Delcroix by Santagata, bronze copies of which were later placed in case dei mutilati around the country (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Bust of Carlo Delcroix by Antonio Santagata and Marble herm of the martyr Giulio Giordani by Adolfo Wildt (author’s photograph, 2015).

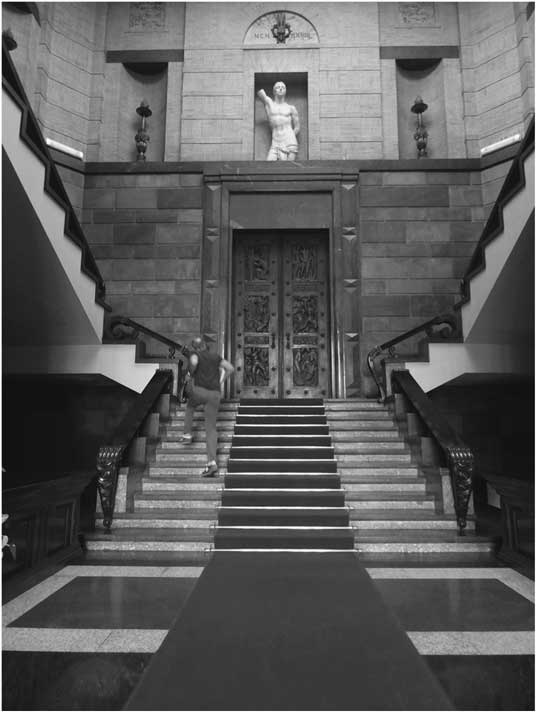

We can imagine them being taken up the grand staircase under the melancholy gaze of St Sebastian by Arturo Dazzi (Figure 4) with a surviving quote by Mussolini: ‘Qui la vittoria è vivente’ (Here victory lives on) above him. The statue of the warrior saint Sebastian has polyvalent meanings. For the mutilati he was a soldier who embodied the sweetness of pain, for the Fascists he was a martyr who neatly fit into their own myths of martyrdom to the Revolution. For today’s public he can easily revert to his original meanings or simply resemble an Apollo. He is a mutilato with no arms but he may also seem like a classical statue with broken ones. The Mussolini quote is generic enough to avoid erasure and was also used on other war memorials (Pietre della Memoria 2015; Zavatti Reference Zavatti2011).

Figure 4 Main stair with statue of Saint Sebastian and bronze doors by Publio Morbiducci (author’s photograph, 2015).

Before entering the Salone delle Adunate, the delegation passed through the highly decorated bronze entry doors by Publio Morbiducci (1928). The six bas-relief panels tell of the Passion of the Infantryman, amalgamating the passion of Christ and life in the trenches (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei1993b, 113). Again, we have a case of polyvalent meaning. For Delcroix, mutilati were heroes who deserved the same saintly status as the war dead. In his book, Sette santi senza candele (Seven Saints Without Candles), he tells the stories of seven mutilati who are not blind because they believe, who are not victims because they continue to fight and to love, and who are not beggars because they can still give. Mutilati are as worthy of envy as any man who has had a taste of victory, even if it meant irretrievable loss (Delcroix Reference Delcroix1928a, 15).

It was then time to enter the Casa Madre’s most exalted space: the Salone delle Adunate, where they could see the only fresco finished in time for the inauguration: the Assalto (Assault) (Figure 5).Footnote 1 Thanks to his established relationship with both Delcroix and ANMIG, Santagata was given the most important (and prestigious) part of the Casa Madre’s decorative scheme. Santagata was just consolidating his style and artistic career when he was wounded in the campaign along the Carso in 1916, and the war affected him irrevocably. His work was firmly Novecento in style and, though a dedicated and politically active mural painter, he was never considered part of Sironi’s set (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi1999, 83–91). Once completed in 1932, the frescoes represented four phases of war: Partenza (Departure), Assalto (Assault), Ritorno (Return) and Vittoria (Victory) (Figure 6).

Figure 5 View of the Salone delle Adunate from the gallery (author’s photograph, 2015).

Figure 6 Three dimensional scheme of the Salone delle Adunate showing location of frescoes. On the left, Partenza and Assalto; on the right, Ritorno and Victory (artwork by Qi Wang based on author’s photographs).

Partenza bears an inscription taken from the King’s 24 May 1915 proclamation of war, while Ritorno has a quote from Mussolini’s newspaper Popolo d’Italia on the third anniversary of Vittorio Veneto. The King’s quote – ‘May glory come to you in planting the Italian tricolore on the sacred confines that nature set down for our Fatherland. May glory come to you in finally completing the great work begun, with much heroism, by out forefathers’ – is politically neutral and belongs to Italian history quite independent of the ventennio. Mussolini’s quote – ‘A new era of our history begins with the celebration of the Unknown Soldier. Otherwise it would be better not to interrupt the slumber without waking those dead who, for centuries, have presided over the borders of the Fatherland’ – ushers in a new age where Italy’s borders are watched over by the war dead: it allows for alternative readings.Footnote 2 Unlike many other inscriptions by Mussolini that were erased or edited in the immediate postwar period, this one also remained intact. When a school group from Ladispoli visited the Casa Madre in 2015 their teacher remarked on the beauty of the quote, with no reference to (and quite possibly no knowledge of) the fact that he was reading a quote by the former Duce (Terzo Binario 2015).

The upper section of the Partenza fresco shows praying soldiers being blessed by a priest flanked by kneeling women; in the bottom panel they march off to war. They are led by an equestrian figure identified as Mussolini that was ‘disguised’ by Santagata in 1950 by the addition of a beard and moustache that are still visible today (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi1999, 87). Arrivo includes portraits of Santagata and Delcroix behind the coffin of the Unknown Soldier and a potentially contentious panel in the bottom centre with a number of black-shirted men giving the Fascist salute. This would have been far more problematic in a public space but clearly was not an issue here. The rest of the panels have other layers of meaning that are not specifically Fascist – in particular, the scene entitled Song, considered one of Santagata’s most successful compositions (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi1999, 87). With its crowd of workers and peasants marching towards a future symbolised by a young child held aloft, its interpretation is fluid. An audience of the ventennio may well have made an immediate association between this image and the Battaglia del Grano that aimed to counteract migration to the cities and keep bread on the table of every family (Sinistri Reference Sinistri1930; Venè Reference Venè1995). The child held aloft symbolised the new generation of Fascists who would perpetuate the regime into the future. For a post-Second World War audience these same images offered another interpretation – the triumph of the working classes and the need to rebuild an antifascist Italy with a new generation of children free from repression.

The Victory fresco in the apse (officially entitled L’offerta della Casa Madre alla Vittoria) dominates the space. Working closely with Piacentini and Delcroix, Santagata reinterpreted the established medieval apse mosaic scheme with Christ at the centre, surrounded by the saints to whom the church is dedicated, the patron and other related saints. This has allowed Santagata’s fresco to remain relevant and understandable to a (mostly) Catholic audience. Santagata painted a triumphant and wingless Victory in place of Christ. Clothed in soft folds of pink, she holds a sword in one hand and an olive branch in the other. The usual figure of a saint is replaced by a sentryman on the left and on the right, in place of the patron offering a model of the church to Christ, we have Delcroix presenting a model of the Casa Madre to Victory (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Scheme of Victory fresco in apse of Salone delle Adunate by Antonio Santagata (artwork by author).

A typical apse mosaic includes hosts of other saints (usually martyrs) and the twelve apostles, often represented as lambs – the symbol of sacrifice par excellence. Santagata instead featured pilots and sailors standing tall and proud amongst army officers and infantrymen along the edge of the apse to represent the branches of the military. Bethlehem and Jerusalem are also key elements of apse mosaic compositions and Santagata replaced the holy cities with those contested by the irredentista movement and included in the Treaty of London that promised Italy the return of Trieste, southern Tyrol, northern Dalmatia, and other territories in return for entering the war alongside the Allies. In the fresco we see key monuments from the four cities Italy was able to win back – Trento, Trieste, Zadar and Pula – and the four Croatian cities that were still contested – Split, Trogir, Sibenik and Dubrovnik (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi1999, 87–88). The città irredente were key to nationalist discourses dear to the hearts of Delcroix, Mussolini and those educated middle-class men who volunteered for the war. Both nationalism and the fraught identities of Italians in the border regions go above and beyond Fascism, beginning before the ventennio and continuing in the postwar era. In Croatia or in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, these questions are alive and well today. The Movimento Irrendentista Italiano (Italian Irredentist Movement), for example, declares itself to be an apolitical organisation that aims to defend and reaffirm Italian identities in those regions still outside the borders of the Italian republic, including Corsica, Malta, the Istrian peninsula and the Ticino (Movimento Irrendentista Italiano 2018).

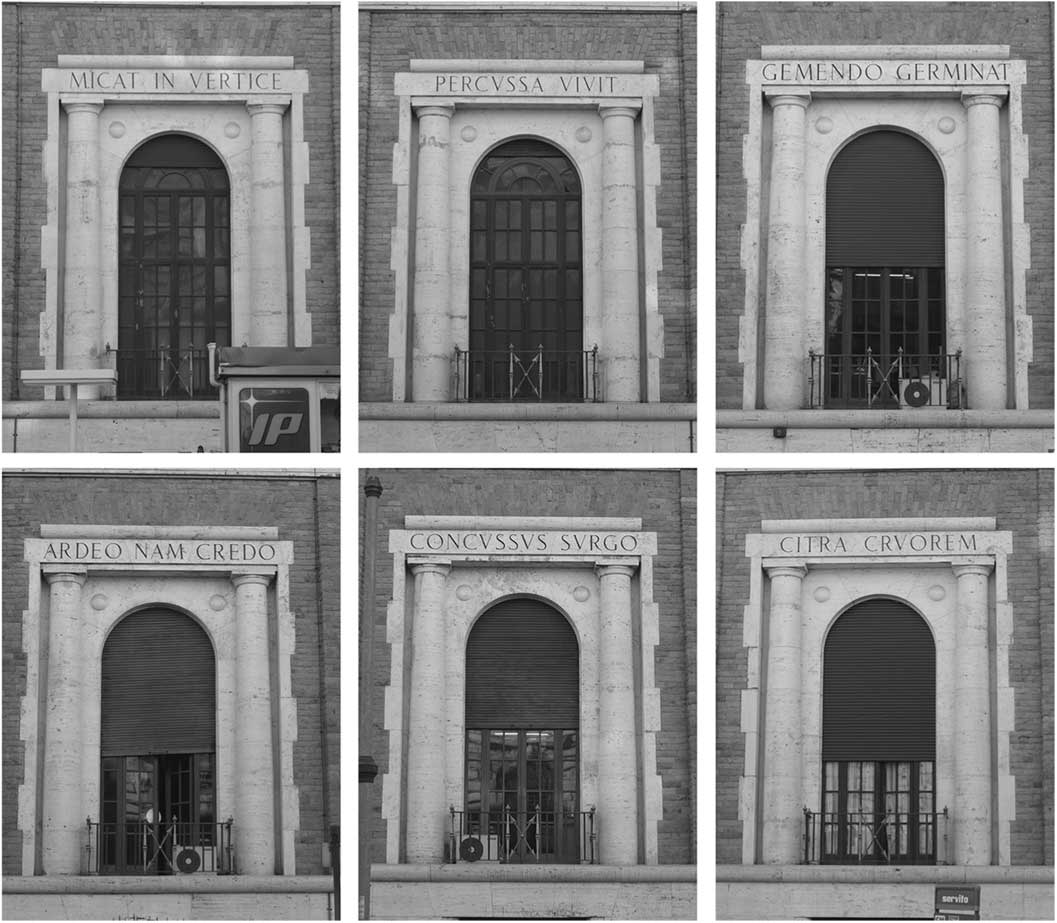

In addition to the frescoes by Santagata, the 1928 decorative programme included a series of Latin inscriptions on the exterior, statues, high relief sculptures and bronze doors with narrative and symbolic bas-relief panels (Figure 8). The Latin quotes, either composed or selected by Delcroix, form a narrative of the experiences of wounded soldiers and bore a strong connection to the characters of Sette santi senza candele, who were each given a Latin quote to describe their sacrifice (Delcroix Reference Delcroix1928a). ANMIG’s motto above the main door is by Delcroix while the other six, above the windows of the piano nobile, read: ‘(He) sparkles at the height’; ‘(Having been) Knocked down he survives’; ‘In lamenting it blossoms’; ‘I burn, for I believe’; ‘Though shaken/pierced I rise’; and ‘This side of blood’ (as flowing from a wound).Footnote 3 These mottoes echoed the slogans of battle pioneered by the ‘poet warrior’ Gabriele d’Annunzio, such as ‘semper adeamus’, as well as the more famous ‘eia eia eia alala’ and ‘me ne frego’ that later made their way into Fascist liturgy (Mosse Reference Mosse1980, 98).

Figure 8 Latin epigraphy above windows (photographs by Ian Woodcock, 2014).

The 1928–1932 decorative scheme remained on display throughout the post-Fascist period, with the minor modifications of Mussolini’s facial hair. The close association with Christian liturgy and motifs has allowed for a more flexible and open meaning that can be read differently according to the social and political context. Though the Casa Madre is technically a public building, it has never had a wide audience and this factor also contributes to the works remaining in their (mostly) original state.

The 1936–1939 decorative plan

Piacentini delegated the architectural expansion of the Casa Madre to his assistant Gaetano Rapisardi and had little involvement with the second decorative plan, which was simply applied to the architecture rather than conceived as an integral element. The new cycle of frescoes was divided up between Sironi, Santagata and Cipriano Efisio Oppo, who was better known as director of the Rome Quadriennale than as a painter. Oppo and Santagata were given the portico around the Cortile della Vittoria while Sironi, being a more prominent painter, was given the Sacrario – a smaller area to paint but in a more prestigious setting (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei2004, 361).Footnote 4 The 1936 inauguration was held, unsurprisingly, on 4 November, in the presence of the (now) emperor-king and queen, who were shown the frescoes under the portico of the Cortile della Vittoria by a party official. This time the mutilati from the Fascist Revolution and the African campaign followed those from the First World War, to give the wounded from the early Fascist era as much importance as those who had fought for their nation (Ricotti Reference Ricotti1936). Mussolini visited two weeks later to examine the Cortile frescoes (Gemmiti Reference Gemmiti1936) but would have to wait two more years to see his portrait by Sironi.

The Cortile della Vittoria

The portico around the Cortile della Vittoria was decorated with a ‘heroic’ fresco cycle depicting various scenes from Italy’s ‘theatres of war’, as pictorial interpretations of the many books, war bulletins and articles in illustrated magazines devoted to each campaign. It also included a series of battle maps complete with arrows and legends, as if to emphasise the strategic aspects of Italy at war. Ragazzi reports that it was hailed at the time as having universal appeal, able to satisfy Piacentini and Delcroix, Santagata as both artist and mutilato, and, finally, intellectuals and ordinary citizens alike (Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi1999, 88). This is regime art at its most didascalic. Although clearly painted to celebrate the constant climate of war that suited the propaganda machine, on another level it can be read simply as a series of battle scenes and maps that chart Italy’s successes in the First World War, the Spanish Civil War, and its imperialist campaigns in Libya, Ethiopia and Greece – the 1917 defeat at Caporetto is, of course, absent.

Santagata’s frescoes of the invasion of Ethiopia and Italy’s most decisive First World War battles – the campaign around the River Piave and Vittorio Veneto (24 October to 4 November 1918), which settled conflict over the contested lands of the Tyrol – were given the most prominence in the Istituto Luce newsreels of the time. Another small trace of Mussolini exists in the Vittorio Veneto fresco: amongst the war-torn wastelands of the countryside near Treviso Santagata included the ruined house that had been famously graffitied by a soldier with the words: ‘È meglio vivere un giorno da leone che cento anni da pecora’ (It’s better to live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep), a fragment of which is kept in the military shrine of Fagarè della Battaglia (Itinerari della grande guerra 2010). It was quoted by Mussolini in one of his speeches and adopted as a Fascist slogan leading many to think he was the author (Solinas Reference Solinas2016). For the audience of the ventennio the saying was very well known. Many would have heard the speech on the radio or seen it on the back of 20 lire coins, and the soldiers gathering in the courtyard may well have walked past the original graffito themselves. For a twenty-first-century audience it is easily associated with Mussolini and his slogans and in 2016 it took on another dimension when Donald Trump retweeted the slogan from the parody account @ilduce2016, not because he wanted to associate himself with Mussolini but because he wanted to associate himself with good quotes (New York Times 2016). The American press focused on the Mussolini element, while the Italian press took great pains to set history straight and ensure the quote was properly attributed to the soldier (New York Times 2016; Il Gazzettino di Treviso 2016; Solinas Reference Solinas2016; TGCom24 2016). As important as it is to get the facts right, it indicates that Italy still has an uncomfortable relationship with its Fascist past and also helps to explain why the quote was never erased (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Detail of the Battle of Vittorio Veneto fresco by Antonio Santagata (photograph by Ian Woodcock, 2014).

In the postwar period, the Cortile della Vittoria was repurposed as a place of remembrance for the eight mutilati killed in the massacre of the Fosse Ardeatine on 24 March 1944. A plaque with a rather forlorn crown of dried laurel now sits directly under the imperial eagle decorating the arengario, surrounded by the cars of the employees who work in the building (Figure 10). This suggests that the Cortile has lost most of its meaning, with the frescoes in a bad state of disrepair and, until recently, largely ignored.Footnote 5 This was not the case for the other part of the 1936-1939 decorative scheme, the more contentious frescoes of Mussolini and the King by the more famous and celebrated Mario Sironi.

Figure 10 Plaque commemorating the eight mutilati killed in the Fosse Ardeatine massacre (photograph by Ian Woodcock, 2014).

Sironi’s frescoes of Victor Emanuel III and Mussolini in the Sacrario

In January 1936, Sironi was commissioned by Delcroix to decorate the Casa Madre’s next most holy space after the Salone delle Adunate – the Sacrario, which was included in the building’s expansion to celebrate the newly-founded ‘empire’ (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei2004, 360). The choice of King and Duce together was probably influenced by Delcroix’s strong monarchist sympathies (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei1993a) but it was not uncommon for images of the King and Mussolini (rex and dux) to be presented as a pendant pair, especially after the proclamation of the empire (Petacco Reference Petacco2009) (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Sacrario delle Bandiere with frescoes of King Victor Emanuel III as Rex imperator (L) and Mussolini as Dux (R) by Mario Sironi (artwork by Qi Wang based on author’s photographs).

Portraits of the Duce were emblazoned across newpapers and illustrated maganizes and came in easily reproducible forms such as medallions, busts and bas- reliefs in wood, bronze, plaster, marble, ceramic and terracotta; statuettes in wood, bronze or painted ceramic; engravings, woodblock prints, photographs, even pocket watches, calendars and what we may now call kitsch souvenirs such as key chains and bottle openers.Footnote 6 These items and others can fetch substantial prices on eBay and Mussolini’s home town of Predappio does a good trade in Mussolini souvenirs (Hökerberg Reference Hökerberg2017, 772). Paintings, murals and public statues, however, are not as easily reduced to the realm of kitsch or memorabilia – nostalgic, ironic or otherwise.

Sironi painted Mussolini as the modern knight-warrior, with his helmet as a smooth extension of his head, though nowhere near as abstract as Thayaht’s more Futurist portraits (1929) (Pieri Reference Pieri2013a, 169-171) or Barbara’s Sintesi aeropittorica del Duce (1940). Clad in black, he stands upright on his noble white horse whose hoof appears to rest on the doorway. An allegorical female figure holds a musket and next to her is a book with the Fascist slogan ‘Credere Obbedire Combattere’ (Believe, Obey, Fight) written on it. She appears to embody the ideal of Libro e moschetto – Fascista perfetto (Book and musket – perfect Fascist). On the right, a male figure looks adoringly up to the Duce. Bare-chested and muscly (apparently Sironi had one of the construction workers model for him) he holds an ancient Roman vexillum in his hands but it has been updated with a stylised portrait of Mussolini and the word Dux. In the background we have the common motifs of a fascio and a dagger and two more outlines more directly connected with the concept of empire: a profile of an eagle and a map of Ethiopia (Figure 12).

Figure 12 Scheme of Mussolini as Dux fresco by Mario Sironi (artwork by author).

The portrait of the King as rex imperator mirrors that of Mussolini opposite. His white horse is in the same pose, his stare is resolute and he wears the same helmet. This image of a warrior king was based far more on legend and propaganda than on military prowess. Sironi also places a soldier on one side and an allegorical female figure – possibly Roma – on the other, holding an orb with ‘impero’ written on it. The background is rendered in similar tones and lists Italy’s First World War battles to echo those painted by Santagata in the courtyard above. On the right two panels show Trento and Trieste – the redeemed cities also shown on the apse of the Salone (Figure 13). Delcroix was a dedicated monarchist and was happy to have a portrait of his King in the Casa Madre but this loyalty was not shared by the postwar nation, who cast a decisive vote to become a republic on 2 June 1946. Victor Emanuel III’s departure from Rome after the 8 September armistice, leaving the country in turmoil, his questionable leadership qualities and his obvious association with Fascism (it was he after all, who called on Mussolini to form a government in 1922) did not win him public favour. His reputation as an inadequate king who never really understood Fascism continues to the present day (Carioti Reference Carioti2017). This made him as worthy of being covered up as the Dux on the other side of the room.

Figure 13 Scheme of King Victor Emanuel III as Rex imperator fresco by Mario Sironi (artwork by author).

After the fall of the regime the frescoes were neither defaced, ‘defascistised’ nor destroyed. In 1946 they were simply covered by thin walls and the space was used as an archive until 1988, when the Soprintendenza ai Beni Storici e Artistici di Roma undertook to reveal and restore the frescoes to their former glory (Barbiellini Amidei Reference Barbiellini Amidei2004, 367). The Sacrario frescoes are now celebrated and advertised but the official ANMIG website shows only the bottom half of the fresco, while other websites like Il primato nazionale (a self-styled ‘quotidiano sovranista’) only show the top half of Mussolini at a suitably aggrandising angle (Tosi Reference Tosi2018).

Conclusion

The Casa Madre is an example of integrated art and architecture that has had continuous use after the fall of the regime. In its first phase it was both ‘fortress and temple’ for invalid soldiers and their families built to honour their sacrifice and contribution in war and to give their life meaning within the new political context of Fascist Italy. The 1936–1939 frescoes were about the continued martial climate of the Ethiopian campaign and Italian involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Today, both phases of the Casa Madre’s decorative scheme are understood (and valued) for a variety of political, cultural and aesthetic reasons: for example that the past acts as a ‘monitum’ for the future, or that Santagata was a good painter. It is true, as Benton has noted, that the general public makes what it can of the art of past regimes (Benton Reference Benton2010), but it has arrived at different conclusions about each phase. The first has an enduring meaning of war and sacrifice, which despite the obvious Fascist salutes in Santagata’s Arrivo fresco, holds true above and beyond any other meanings that the regime chose to overlay upon it.

The Casa Madre did not, like many other buildings of the Fascist era, disrupt the collective memory of the community by replacing it with a set of Fascist ones: it allowed different meanings to overlap and coexist (Benton Reference Benton2010, 152). The architecture and the decorative programme reified the collective memory of the wounded soldiers and their association. This assemblage was temporarily appropriated and replaced by the imperative needs of Fascist propaganda and when the regime fell the original meaning was easily retrieved.

The Casa Madre successfully negotiates the tension between the public memory of Fascist-era architecture and the memory of individuals. The mutilati were the unseen and unworthy underdogs who therefore needed to create their own individual legacy to give themselves value within broader Italian society. The Casa Madre (along with other case dei mutilati built around the nation) was successful in achieving this above and beyond its collaboration with and co-option by the Fascist propaganda machine.

Thanks to local politics and the individual peculiarity of certain buildings and their unique decorative schemes, the aesthetic integrity of the frescoes of the Casa Madre, like many other monumental works that are part and parcel of Fascist architecture, is seen to surpass their power as political propaganda even when they continue to perpetuate Fascist mythologies (Maulsby Reference Maulsby2014, 29). Because of its continuity of meaning, the Casa Madre has not had to go through such a strong desacralisation process as Bolzano’s Victory Monument (Hökerberg Reference Hökerberg2017, 768–769). The continuity of iconography, mythical distortion and triumphalism of the war experience between the Liberal and Fascist regimes continued into the period of the First Republic, though clothed in the vestments of anti-Fascist rhetoric, and deserves more recognition, appreciation and exposure than it receives.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues at Swinburne’s writing workshops for all their feedback in the drafting of this article. I would also like to acknowledge the Piacentini Archives in Florence, the State Central Archives in Rome, ANMIG National President Claudio Betti and Dr Lorenza Fabrizi at ANMIG for her advice and a wonderful tour of the building. And finally, Qi Wang for her invaluable help with the illustrations.

Flavia Marcello is Associate Professor of architectural history at Swinburne’s School of Design and member of the Centre for Design Innovation. She is a world expert on the art and architecture of the Italian Fascist period and the urban planning of Rome. Her areas of research have recently expanded to include the political use of classicism; political manifestations in monuments and public spaces; and the legacy of Fascism in contemporary society. She teaches in the areas of design, history and theory with a particular focus on the inter-relationship between art and architecture. She is the author of ‘Mussolini and the Idealisation of Empire: the Augustan Exhibition of Romanità’, Modern Italy. 16:3, 2011; ‘Speaking from the Walls: Militarism, Education and Romanità in Rome’s Città Universitaria (1932–35)’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 74:3, 2015 (with Paul Gwynne); and ‘Rome Remembers Fascism: Considering the Monument to the Fosse Ardeatine Massacre as an Immersive Historical Experience’. Rethinking Histories 20:1, 2017. Her monograph on Italian-Istrian architect Giuseppe Pagano-Pogatschnig is due to be published with Intellect Press in 2020.