The differentiation between coagulase-positive and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) is of major relevance in routine mastitis diagnostics. Among the three coagulase-positive Staphylococcus species (Staph. aureus, Staph. intermedius and Staph. hyicus), the most important cause of bovine mastitis is Staph. aureus, which species differs from the other two by frequently having beta-haemolytic activity on blood agar plates (Kloos & Schleifer, Reference Kloos and Schleifer1975). The diagnosis coagulase-positive staphylococci has a major impact on treatment of a cow or a dairy herd, while CNS are still frequently regarded as ‘minor pathogens’.

The decisive criterion for differentiation of mastitis staphylococci is the standard coagulase tube method, in which a coagulase-positive Staphylococcus isolate gelatinizes with plasma via the activity of extracellular free coagulase. Therefore, presence of beta-haemolysin on blood agar in combination with a positive coagulase activity seems to represent the optimal criterion for the identification of Staph. aureus from mastitis milk samples (Varshney et al. Reference Varshney, Kapur and Sharma1993; Lam et al. Reference Lam, Pengov, Schukken, Smit and Brand1995; Boerlin et al. Reference Boerlin, Kuhnert, Hussy and Schaellibaum2003). Additionally, testing for the presence of surface proteins, clumping factor (CF) and/or protein-A, are helpful in routine analysis for the rapid identification of Staph. aureus. Finally, the presence of a DNase activity is often used as a surrogate marker for the identification of coagulase-positive staphylococci, particularly of Staph. aureus, in milk samples (Menzies, Reference Menzies1977; Boerlin et al. Reference Boerlin, Kuhnert, Hussy and Schaellibaum2003). Most of these test parameters have been extensively validated for use in identifying Staph. aureus from human clinical specimens.

The known specificity of all these tests has previously been used to identify atypical variants of Staph. aureus strains isolated from clinical specimens and mastitis milk samples (Kloos & Schleifer, Reference Kloos and Schleifer1975; Heltberg & Bruun, Reference Heltberg and Bruun1984; Smyth et al. Reference Smyth, Wright and Marples1988; Bodén et al. Reference Bodén and Flock1989; Fox et al. Reference Fox and Gay1993; Mackay et al. Reference Mackay, Quick, Gillespie and Kibbler1993; Laevens et al. Reference Laevens, Devriese, Deluyker, Hommez and de Kruif1996; Matthews et al. Reference Matthews, Roberson, Gillespie, Luther and Oliver1997; Personne et al. Reference Personne, Bes, Lina, Vandenesch, Brun and Etienne1997; Wilkerson et al. Reference Wilkerson, McAllister, Miller, Heiter and Bourbeau1997; Mlynarczyk et al. Reference Mlynarczyk, Kochman, Lawrynowicz, Fordymacki, Mlynarczyk and Jeljaszewicz1998; Smole et al. Reference Smole, Aronson, Durbin, Brecher and Arbeit1998; Al Obaid et al. Reference Al Obaid, Udo, Jacob and Johny1999; van Griethuysen et al. Reference Van Griethuysen, Bes, Etienne, Zbinden and Kluytmans2001; Garbacz et al. Reference Garbacz, Piechowicz, Wisniewska and Galinski2002; Malinowski et al. Reference Malinowski, Lassa, Klossowska, Smulski and Kaczmarowski2009). In fact, Staph. aureus strains showing non-expression of these major characteristics are rare but not absolutely uncommon in routine analysis. A certain percentage of Staph. aureus isolates is therefore misidentified as CNS (Ruane et al. Reference Ruane, Morgan, Citron and Mulligan1986; Neville et al. Reference Neville, Billington, Kibbler and Gillespie1991;Wanger et al. Reference Wanger, Morris, Ericsson, Singh and LaRocco1992; Vandenesch et al. Reference Vandenesch, Bes, Lebeau, Greenland, Brun and Etienne1993; Vandenesch et al. Reference Vandenesch, Lebeau, Bes, McDevitt, Greenland, Novick and Etienne1994a, Reference Vandenesch, Lebeau, Bes, Lina, Lina, Greenland, Benito, Brun, Fleurette and Etienneb).

Other diagnostic methods based on DNA sequence have been significantly improved for identification of mastitis staphylococci during recent years. Such methods, for example sequencing of 16S rRNA genes, and PCR of species-specific fragments of ribosomal RNA, thermonuclease, coagulase, clumping factor and protein A genes, were used in numerous studies (Brakstad et al. Reference Brakstad, Aasbakk and Maeland1992; Forsman et al. Reference Forsman, Tilsala-Timisjärvi and Alatossava1997; Martineau et al. Reference Martineau, Picard, Roy, Ouellette and Bergeron1998; Straub et al. Reference Straub, Hertel and Hammes1999; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Annemüller, Hassan and Lämmler2000; Akineden et al. Reference Akineden, Annemüller, Hassan, Lämmler, Wolter and Zschöck2001; Woo et al. Reference Woo, Leung, Leung and Yuen2001; Boerlin et al. Reference Boerlin, Kuhnert, Hussy and Schaellibaum2003).

To reduce the impact of errors in routine diagnostics, or at least to evaluate the dimensions of the margin of error in routine analysis due to atypical strains, control analyses are advisable using molecular characterization of a certain percentage of isolates, and in particular of suspect isolates, seems to be advisable. In the present study, two atypical variants of Staph. aureus strains isolated from milk samples of a dairy cow with subclinical mastitis were investigated using standard methods for identification of mastitis samples and subsequently confirmed with genotypic methods.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and characterization of the bacteria

During routine mastitis diagnostics in our laboratory, milk samples from two quarters of a dairy cow suffering from subclinical mastitis were subjected to the standard analytical scheme (Anonymous, 2009). From each milk sample 0·1 ml initially was spread on sheep blood agar and incubated aerobically for 24–48 h at 37°C as described previously after incubation colonies were weakly positive for beta-haemolysin. Two isolates (k54-2 and k54-3) were further tested for catalase, clumping factor reactions with EDTA rabbit plasma (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), coagulase tube test, aerobic production of acid from mannitol (mannitol salt agar, Oxoid), Staphaurex® test (Murex, Wiesbaden, Germany) for the detection of surface protein of Staph. aureus and cultured on Baird Parker agar (Merck) for lipase activity.

DNase and thermonuclease activity was performed on Toluidinblue O-DNase agar (Merck). Production of haemolysins was determined by the interaction of haemolysins with the β-toxin of a Staph. aureus strain as described by Skalka et al. (1979). Both isolates were characterized using two commercial systems, the BD BBL Crystal system (Becton Dickinson, Darmstadt, Germany) and the ID 32 Staph system (bioMerieux, Wiesbaden, Germany).

The antibiotic sensitivity test was performed as follows: four to five identical colonies were incubated in 3 ml of Todd-Hewitt broth (THB, Oxoid) for 2 h at 37°C. Bacterial suspension (0·1 ml) was plated on Mueller-Hinton agar (Merck), followed by addition of antibiotic disks [ampicillin, 10 μg; bacitracin, 10 U; cefquinome sulphate, 10 μg; cloxacillin, 25 μg; enrofloxacin, 5 μg; kanamycin, 30 μg; trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, 25 μg; tetracycline, 30 μg; gentamicin, 10 μg; amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, 20/10 μg; lincomycin at 60 μg with neomycin at 15 μg; colistin sulphate, 10 μg; penicillin G, 10 IU (Oxoid), danofloxacin, 5 μg; and cefoperazone, 10 μg (Pfizer, Karlsruhe, Germany)].

Testing for enterotoxin production

Both strains were tested for their ability to produce enterotoxins A, B, C, D and E in brain heart infusion culture (BHI (Merck), 18–24 h at 37°C) by using a commercial enzyme immunoassay kit (Ridascreen SET, R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany). Tests were performed from BHI culture material after filtration (0·2 μm, FP30/0·2CA-S, Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany).

Molecular identification of the bacteria

DNA extraction

Bacterial DNA was isolated after cultivation of the bacteria in 5·0 ml BHI. From this culture, 0·1 ml was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min, and the pellet resuspended in 180 μl TE buffer (10 mmol/l of Tris–HCl, 1 mmol/l of EDTA; pH 8·0) containing 5 μl of lysostaphin (1·8 U/μl; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, 10 μl proteinase K was added to the suspension and incubated for 2 h at 56°C. DNA was subsequently isolated with the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene

The two isolates were identified by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene using the primers 16SUNI-L and 16SUNI-R as described previously (Kuhnert et al. Reference Kuhnert, Capaul, Nicolet and Frey1996). The PCR reaction was carried out in a 30-μl total volume in a 0·2-ml reaction tube containing 3 μl GeneAmp 10x PCR Gold Buffer (150 mmol/l Tris–HCl, 500 mmol/l KCl; pH 8·0) (Applied Biosystem, Darmstadt, Germany), 1·8 μl MgCl2 (25 mmol/l) (Applied Biosystem), 1·0 μl from each primer (10 pmol/μl), 0·6 μl dNTP-mix (10 mmol/l) (MBI Fermentas, St Leon-Rot, Germany), 0·2 μl AmpliTaq Gold® polymerase (5 U/μl, Applied Biosystem), 19·9 μl sterile Aqua dist. and 2·5 μl DNA template. PCR conditions for the iCycler (BioRad, Munich, Germany) were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s and 72°C 60 s and a final extension 1 cycle at 72°C for 7 min. The purified DNA (30 μl volume) was sequenced by SEQLAB Sequence Laboratories (Göttingen, Germany) in ABI DNA Sequencer System (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). The 16S rRNA sequences of the two isolates were aligned against sequences of Staph. aureus (accession no. Y15856), Staph. intermedius (D83369), Staph. hyicus (D83368) and Staph. epidermidis (AM157417) and analysed by using the MegAlign program (DNASTAR, Inc., MadisonWI, USA).

PCR-amplification of genes encoding staphylococcal proteins and toxins

The two coagulase-negative Staph. aureus isolates were additionally characterized by PCR amplification of species-specific parts of the 23S rRNA, 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region, coagulase (coa), clumping-factor (clfA), alpha haemolysin (hla), beta haemolysin (hlb), thermonuclease (nuc), and IgG binding region and x-region of protein A (spa) genes, as well as the staphylococcal enterotoxins genes sea to selo, the toxic shock syndrome toxin gene tst, and exfoliative toxins A (eta) and B (etb). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers, the thermocycler programs, and the corresponding literature references were described by Akineden et al. (Reference Akineden, Hassan, Schneider and Usleber2008).

PCR reaction was carried out in a 30-μl volume containing the same composition of reagents as described above. PCR products were determined by electrophoresis of 12 μl of the reaction product in a 2% agarose gel (Biozym, Hessisch-Oldendorf, Germany) at 120 Volt in 1x Tris–acetate-electrophoresis buffer (TAE) [(0·04 mol/l Tris, 0·001 mol/l EDTA; pH 7·8)]. The molecular marker GeneRuler 50 and a 100-bp DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas) were used.

Reverse transcriptase-PCR

Total RNA (approximately 8 μg) was extracted from isolates after 18 h of culture using the RNeasy-Mini kit (Qiagen) as described by Akineden et al. (Reference Akineden, Hassan, Schneider and Usleber2008). DNA digestion was performed by incubating 10 μl extracted RNA with 3 μl of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) (1 U/μl) in a 500-μl RNase-free Eppendorf cap at 37°C for 30 min. DNase was inactivated by heating the solution at 75°C for 5 min. Then the solution was cooled on ice and either immediately used for RT-PCR or stored frozen at −80°C.

cDNA was synthesized with Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen) by incubating at 42°C for 1 h. The reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 2 μl of 5×Qiagen RT-PCR buffer (including 12·5 mmol/l MgCl2), 2 μl of dNTP mix (containing 5 mmol/l each dNTP), 1 μl of Rnasin inhibitor (40 U/μl; N2111, Promega), 1 μl of a random hexamer primer (Promega), 2 μl of Qiagen RT polymerase (4 U/μl), template RNA (2 μl of the RNA extract) and 9 μl of Rnase-free water. As a control for genomic DNA contamination, total RNA was also subjected to reverse transcription (RT)-PCR but without the RT step. The coa, clfA, nuc and sec cDNAs were then detected using the same primers and PCR protocol described by Akineden et al. (Reference Akineden, Hassan, Schneider and Usleber2008).

Results

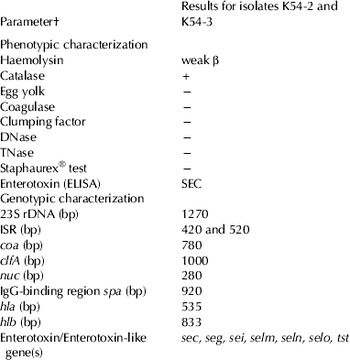

Both isolates showed identical properties with regard to all tested biochemical reactions, and were also identical in aspects of the tested genetic traits (Table 1).

Table 1 Summarized phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the two Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from mastitis milk

† See text for explanation of abbreviations

Phenotypic properties

Both isolates showed morphological characteristics consistent with Staph. aureus on blood agar, yellow pigmentation and a very weak beta-haemolysin reaction. They formed typical colonies on Baird Parker agar but were egg yolk-negative. They were catalase-positive, clumping factor-negative, coagulase-negative, DNase-negative, thermonuclease-negative and also negative in the Staphaurex® test system. The BD BBL Cyristall® system and ID 32 Staph® identified both isolates as Staph. aureus with ‘confident 0·9275’ and ‘identity 99·8%’ (ID number 36733261), respectively. Both isolates were positive for enterotoxin C in the RIDASCREEN SET EIA. They were sensitive towards ampicillin, penicillin G, cefoperazone, bacitracin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, lincomycin-neomycin, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, enrofloxacin, gentamicin, tetracycline, cefqiunom sulphate, cloxacillin, danofloxacin, and resistant towards colistin sulphate and kanamycin.

16S rRNA sequence and other genotypic characteristics

PCR of 16S rRNA gene of both isolates yielded an amplicon size of 1360 bp. These amplicons were sequenced and the sequence submitted to the NCBI GenBank [accession no. GU459255 (strain k54-2) and GU459256 (strain k54-3)]. Comparison of both 16S rRNA sequences with the corresponding sequences of Staph. aureus (accession no. Y15856), Staph. intermedius (D83369), Staph. hyicus (D83368) and Staph. epidermidis (AM157417) showed 99·7%, 96·0%, 96·7% and 98·4% similarity, respectively.

Additionally, the species identity of both isolates as Staph. aureus could be confirmed by PCR amplification of the genes encoding for 23 rRNA (1·270 bp), coa (600 bp), clfA (1000 bp), nuc (280 bp) and IgG binding region of protein A spa (920 bp), hla (535 bp), hlb (833 bp). Amplification of the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region yielded two distinct amplicons (420 bp and 520 bp) in the same PCR. Further genotypic properties of the Staph. aureus isolates revealed that certain genetic traits such as the enterotoxin genes sec, seg, sei, selm, seln, selo and tst could be detected in both isolates. None of the isolates harboured the genes encoding sea, seb, sed, see and sej.

Reverse transcriptase-PCR

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis proved that the mRNAs of coagulase, clumping factor and thermonuclease were transcribed in both Staph. aureus isolates. In comparison, both isolates were also positive for the genes coa, clfA and nuc, but were negative in the biochemical tests for coagulase, clumping factor or thermonuclease. In this context, the staphylococcal enterotoxin C gene was also used as a positive control in RT-PCR.

Discussion

Coagulase-negative variants of Staph. aureus strains were first isolated from milk samples derived from subclinical mastitis cases in dairy cattle (Fox et al. 1996; Laevens et al. Reference Laevens, Devriese, Deluyker, Hommez and de Kruif1996; Matthews et al. Reference Matthews, Roberson, Gillespie, Luther and Oliver1997; Malinowski et al. Reference Malinowski, Lassa, Klossowska, Smulski and Kaczmarowski2009). In some other clinical studies, detection of coagulase-negative Staph. aureus was described but the reported results from phenotypic tests, such as beta-haemolysin, strong DNase activity, production of phosphates and slide clumping factor, nitrate reduction, and utilization of certain sugars made the identification of Staph. aureus questionable (Golledge & Gordon, Reference Golledge and Gordon1989, Mlynarczyk et al. Reference Mlynarczyk, Kochman, Lawrynowicz, Fordymacki, Mlynarczyk and Jeljaszewicz1998, Aarestrup et al. Reference Aarestrup, Larsen, Eriksen, Elsberg and Jensen1999). Biochemical and other phenotypic tests per definition cannot consistently identify bacterial species having an ambiguous biochemical profile (Notarnicola et al. Reference Notarnicola, Zamarchi and Onderdonk1985). Amplification of the coagulase gene of staphylococci can be performed by PCR used for identification of atypical coagulase negative Staph. aureus (Luijendijk et al. Reference Luijendijk, van Belkum, Verbrugh and Kluytmans1996). However, economic reasons prohibit a broader use of such methods in routine mastitis diagnostic. Therefore, reports on the occurrence of coagulase-negative Staph. aureus in bovine milk are still extremely rare, considering the number of analyses performed worldwide. In this study, two tentative staphylococcal isolates from mastitis milk appeared negative for the clumping factor, coagulase, thermonuclease, and Staphaurex® test. In a normal situation, this would have been more than enough to ‘identify’ the isolates as coagulase-negative staphylococci. However, a very weak beta-haemolysin activity of these isolates motivated us to perform further work on identification.

PCR-based systems for identification of Staph. aureus isolates were used as described earlier for genes encoding the 16S rRNA, 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacer region, 23S rRNA, as well as the genes encoding staphylococcal thermonuclease (nuc), clumping-factor (clfA), IgG binding region encoding part of protein A and coagulase (coa) (Brakstad et al. Reference Brakstad, Aasbakk and Maeland1992; Lange et al. Reference Lange, Cardoso, Senczek and Schwarz1999; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Annemüller, Hassan and Lämmler2000; Akineden et al. Reference Akineden, Annemüller, Hassan, Lämmler, Wolter and Zschöck2001). Although all these target genes allow a rapid identification of this species with high sensitivity and specificity, it is of some importance that we could detect not only the DNA sequences but also the corresponding mRNA by RT-PCR. However, only expression of enterotoxin C was detected by protein-based tests. This again shows that even positive results for gene transcription (RT-PCR) does not necessarily mean that it is translated in quantities above the detection level. The sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene of both isolates was used as a complementary method to the phenotypic tests. Although this is still far from being a routine method, sequence analysis seems to be a promising technique for identification and differentiation of staphylococci from cases of bovine mastitis in the future.

Routine mastitis laboratories should keep in mind that identification of Staph. aureus based on the coagulase test as the decisive criterion may give misleading results, although such cases are probably very rare. As in our case, a very weak beta-haemolysin activity – in spite of negative clumping factor and coagulase reactions – may be a reason to trigger further detailed investigation. At the moment, however, it is impossible to estimate the frequency of coagulase-negative Staph. aureus in the context of bovine mastitis. However, since the consequences of a Staph. aureus diagnosis are much more serious than that of coagulase-negative staphylococci for dairy cows, a better knowledge of the epidemiology of coagulase-negative Staph. aureus strains in dairy production would be helpful.