INTRODUCTION

A diagnosis of cancer may considerably affect a patient's psychological well-being; this, in turn, may impact on treatment tolerance and outcomes, prolonging medical management and increasing health care costs. Different studies conducted in recent decades have revealed that pathological levels of distress were highly prevalent in oncology: Figures range from 5% to 50%, depending on disease-related characteristics and modes of treatment, but also on assessment procedures (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Sommerfeldt and Fischer2004).

Health care providers often fail to recognize cancer patients' psychological distress (Passik et al., Reference Passik, Dugan and McDonald1998; Fallowfield et al., Reference Fallowfield, Ratcliffe and Jenkins2001; Söllner et al., Reference Söllner, DeVries and Steixner2001, Reference Söllner, Maislinger and Konig2004; Maguire, Reference Maguire2002). Various explanatory factors, such as the clinical time available and the clinicians' skills or motivation, have been suggested. As a result, referral to psychological providers occurs mainly when the patient is severely anxious or depressed. Screening programs have thus been implemented to enable health care providers to identify patients who are at higher risk of psychological morbidity in order to initiate clinical interventions earlier and so prevent severe psychological disorders during the course of the illness (Zabora, Reference Zabora, Rowland and Holland1998). Such procedures are intended to enhance health care outcomes, preserve patients' quality of life, and improve their satisfaction with care. Alongside survival, these care objectives have been recognized as an integral part of the global care contract.

Structured clinical interviews or self-reported measures have been developed to screen for psychological distress at critical stages in the course of the disease. Given the heavy workload of oncology clinics and the ever shorter hospital stays, methods for psychological screening must be brief and pragmatic (a single global score without any additional information may be sufficient to allow for the identification of the parameters of interest and for classification purposes). A number of well-validated measures exist that can be used as screeners, including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmund & Snaith, Reference Zigmund and Snaith1983), the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis et al., Reference Derogatis, Morrow and Fetting1983; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis2000) or the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1978). However these instruments require time to administer, which may prevent their systematic use in the routine care of busy oncology clinics.

The Distress Thermometer (DT; Holland, Reference Holland1997; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003) is a brief and simple tool that has proved acceptable and useful in prostate cancer patients (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Kornblith and Batel-Copel1998) and more recently in bone marrow transplant patients (Trask et al., Reference Trask, Paterson and Riba2002; Ransom et al., Reference Ransom, Jacobsen and Booth-Jones2006), in mixed cancer populations (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Zevon and D'Arrigo2004; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005) as well as in culturally diverse cancer patient populations (Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007). In these studies, the DT was compared to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Trask et al., Reference Trask, Paterson and Riba2002; Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007), to the brief symptom inventory (BSI) (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Zevon and D'Arrigo2004; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005), and to the center for epidemologic studies depression scale (CES-D) and state-trait anxiety inventory-state (STAI-S) (Ransom et al., Reference Ransom, Jacobsen and Booth-Jones2006), demonstrating acceptable convergent, divergent (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Zevon and D'Arrigo2004) or criterion validity (Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007), as well as measurement accuracy, with a cutoff score of 4 or 5 leading to optimal sensitivity and specificity (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Kornblith and Batel-Copel1998; Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005; Ransom et al., Reference Ransom, Jacobsen and Booth-Jones2006; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007).

The DT is a visual one-item self-report distress tool using the representation of a thermometer. This was selected, in the context of cancer, by analogy with indicators of individuals' physical functioning such as temperature and more recently visual analog scales for pain. Distress could be another useful indicator, because mental well-being and good spirits may play an important role in health (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003; Bultz & Carlson, Reference Bultz and Carlson2006; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Andersen and Breitbart2007).

This study aims to assess the feasibility of a psychological distress screening procedure in two cancer centers in France as well as to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of a French adaptation of the Distress Thermometer (called the Psychological Distress Scale [PDS]), in comparison with the HADS, using the established clinical threshold in cancer patients. From responses from a large sample of cancer outpatients (n = 561), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses are used to determine the ability of the PDS to distinguish cancer patients with clinically significant distress from those without, based on the previously established HADS cutoff score of 15. In addition, the relationships between psychological distress and measures of quality of life and psychosocial difficulties are also explored.

METHODS

Participants

Between May and November 2000, 598 patients aged 18 and over, with a confirmed histological diagnosis of cancer, with no major unstable medical or psychiatric condition, able to read and speak standard French, and attending the outpatient oncology clinic in Institut Curie (n = 335) or Institut Gustave Roussy (n = 226) in Paris, France, were approached. At inclusion, patients were stratified according to site of cancer diagnosis (breast, gynecological, brain, ophthalmic, lung, prostate, head and neck, and other cancer diagnoses). Among these, 37 patients refused to participate, 24 because they felt too “stressed,” did not want to talk about psychological reactions, or found the study irrelevant, 9 because they felt too tired or presented a hearing impairment, headache, or difficulty understanding; 4 other patients because they found the questions inappropriate, had to be seen immediately by the doctor, or declared they were not available.

Procedure

Eligible patients were contacted by a clinical research associate who introduced them to the objectives and procedure of the study. Upon agreement and after providing informed consent, patients were handed the PDS, the HADS, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer core quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), and a sociodemographic and psychosocial form to complete while waiting to see their oncologists. Conditions of confidentiality were ensured in the waiting rooms.

Data Collected and Measures

For all patients, medical data (type of cancer site, phase of illness, extent of the disease, type of treatment, analgesic use), sociodemographic data (age, gender, marital status, educational level, professional status), and psychosocial information (open-ended questions on psychological treatment, psychosocial difficulties, and social support) were collected from the medical files.

Psychological Distress Scale

The PDS is derived from the Distress Thermometer (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003). In its original English language presentation, this scale shows a thermometer graduated from 0 (no distress) to 10 (severe distress) (graduation visible for the patient), enquiring about the patient's distress in the past 7 days. Pilot testing the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-developed DT with health care providers in France led to modifying the layout of the tool. Quantifying psychological distress was found not to be well accepted, especially using a picture of a thermometer, because this is associated with biological parameters. As a result, the visual device used in this tool was changed to a 10-cm vertical line.

The word “distress” was chosen by the NCCN to soften the perceived social stigma associated with psychopathological labels and thus favor spontaneous disclosure of any psychological suffering experienced by cancer patients. The French literal translation of the term “distress” does not have the same connotations as the English word. In French, the word “distress” could be translated by the words “détresse,” “souffrance,” “désarroi,” or even “difficulté” with or without the accompanying adjective “psychologique.” Although the word “détresse” includes ideas of severe suffering, danger, fear of death, and need for help (while in English a subject can feel “distress” about relatively trivial things too), conciliation discussions between clinicians specialized in psycho-oncology finally led to selecting this word, but including a reference to the psychological state (“détresse psychologique”).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The HADS is a 14-item self-report scale developed for medical patients, assessing anxiety (HAD-A) and depression (HAD-D) (Zigmund & Snaith, Reference Zigmund and Snaith1983). This questionnaire is designed as a global measure of emotional distress, evaluating mild and mixed features of mood disorders (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1990; Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Howell and Maguire1991; Ibbotson et al., Reference Ibbotson, Maguire and Selby1994; Van't Spijker et al., Reference Van't Spijker, Trijsburg and Duivenvoorden1997; Costantini et al., Reference Costantini, Musso and Viterbori1999). Subjects rate the frequency of anxious or depressive symptoms experienced over the past week. The HADS total score ranges from 0 to 42, a higher score indicating more distress. This questionnaire has been validated in French in a general medical population (Lépine, Reference Lépine and Guelfi1997) and in cancer inpatients (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1989) and is widely used in the field of cancer (Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Howell and Maguire1991; Ibbotson et al., Reference Ibbotson, Maguire and Selby1994; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Lewis and Fallowfield1995; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Hoffman and Theodoulou1999; Reuter & Härtner, Reference Reuter and Härtner2001). Using the HADS as a global scale, cutoff scores for overall psychological distress (adjustment and major anxiety/depressive disorders) vary, ranging from 10/11 (to detect emotional distress/adjustment disorders and major mood disorders) to 18/19 (to detect major mood disorders) for example, cutoff score at 10 (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1990; Costantini et al., 1999), 11 (Aass et al., Reference Aass, Fossa and Dahl1997; Kugaya et al., Reference Kugaya, Akechi and Okuyuma1998), 13 (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1990; Hall et al., Reference Hall, A'Hern and Fallowfield1999), 14 (Ibbotson et al., Reference Ibbotson, Maguire and Selby1994; Brédart et al., Reference Brédart, Didier and Robertson1999), 15 (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Kornblith and Batel-Copel1998; Kugaya et al., Reference Kugaya, Akechi and Okuyama2000), 16 (Bérard et al., Reference Bérard, Boermeester and Viljoen1998; Reuter & Härtner, Reference Reuter and Härtner2001), and 19 (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1990; Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Howell and Maguire1991).

A cutoff point needs to be chosen in relation to the screening requirements arising from the specific clinical and economic situation (e.g., choosing a low cutoff raises sensitivity, whereas an increased number of false positives would inappropriately increase the staff work load). We chose a cutoff value greater than or equal to 15 to detect patients with a significant level of emotional distress, as well as to allow comparison with the studies using both the HADS and the DT as screening tools (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Kornblith and Batel-Copel1998; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005). Our strategy was guided by the need to avoid “missing” any patient presenting a major anxiety or depressive disorder requiring specific psycho-oncological intervention. This HADS cutoff score of 15 appeared to detect significant clinical distress with an adequate level of accuracy (Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005).

EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a quality of life scale developed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and specifically designed for cancer patients (Aaronson et al., Reference Aaronson, Ahmedzai and Bergman1993). The EORTC QLQ-C30 is composed of five functional scales, three symptom scales, six single-item scales, and one global health status scale. Scale scores are calculated by averaging items within scales and transforming average scores linearly. All of the scales range in score from 0 to 100. A high score for functional or global health status scales represents a high/healthy level of functioning; a high score for a symptom scale/item indicates a high level of symptomatology or problems.

Statistical Analysis

The determination of the clinically significant “distress” cutoff value was performed using the ROC method and a HADS total score of 15 or greater as a reference. Representing ROC analyses on a curve is a way of expressing the relationship between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (1 − specificity) for different cutoff scores. The sensitivity of a test is its ability to detect cases, and its specificity refers to its ability to detect noncases. The curve is a representation of the ability of the screening instrument to discriminate between cases and noncases (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Farvacques1990). We selected the point on the ROC curve that maximized test sensitivity and specificity, so as to avoid missing cases.

Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to test the relationship between PDS and HADS total, HAD-A, or HAD-D scale scores. Nonparametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test the relationship between PDS scores and variables with two, or two or more values. Multivariate analysis was performed according to descending logistic regression methods. A significance threshold equal to 0.20 in univariate analysis was adopted for selection of variables to be included in the model.

Statistical analyses were performed using Epi-Info 6.04, S-Plus, and SAS Version 8.1 software packages.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Of the 598 patients who were approached, 561 agreed to participate in the study (94%). No difference was noted between patients who participated and patients who refused in terms of sociodemographic characteristics (recruitment hospital, gender, age) or cancer-related characteristics (tumor site, time since last medical event [diagnosis, metastasis, recurrence], current stage, or presence of disease progression, metastasis or recurrence). Table 1 lists patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Mean (SD) age of the study sample was 57.5 (14.6) years with 84 (15%) of the patients over the age of 69 years. Three-hundred and three (54%) patients had a level of education below secondary school diploma. Disease duration and severity were heterogeneous across patients; 106 (19%) patients had metastatic cancer and 125 (22%) subjects were taking analgesics.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

aHomemakers, unemployed, disabled.

bTwo missing data.

Mean (SD) and range of the HADS total, HAD-A, and HAD-D scores were respectively 13.3 (6.8) and 0–36; 8.2 (4.2) and 0–21; 5.0 (3.9) and 0–19. The number (percentage) of patients scoring 67 or less (≤75th percentile, meaning poorer functioning) on the EORTC QLQ-C30 physical, role, emotional, cognitive, social, and global health status scales were, respectively, 155 (28%), 184 (33%), 221 (39%), 215 (38%), 187 (33%), and 310 (55%).

One third of the study population was receiving professional psychological help (31%), including psychotherapy (2%), psychotropic drugs (21%), or a combination of the two (8%). One hundred thirty-one subjects (23%) reported a difficult professional, emotional, or financial situation and almost the same proportion (21%) reported lack of support from their friends and family.

Relationship between the PDS, HADS, and EORTC QLQ-C30 Scores

Convergent validity of the PDS was tested by assessing the correlations between the PDS and the HADS total and subscale scores. Pearson's correlation coefficient between the PDS scale and the HADS global scale was .64 (p < .0001) and .61 between the PDS scale and HADS anxiety subscale (p < .0001). Pearson's correlation coefficient between the PDS scale and the HADS depression subscale was .39 (p < .0001).

Statistically significant correlations were observed between the PDS scores and the EORTC QLQ-C30 “emotional functioning” and “global health status” subscales, with Spearman correlation coefficients of −.56 (p < .0001) and −.44 (p < .0001), respectively.

PDS scores were also significantly related to deterioration in the EORTC QLQ-C30 physical, role, cognitive, or social functioning scores and to increasing symptom scores (p < .001 for all correlation tests), except for the diarrhea and financial difficulty scales.

Establishment of a Psychological Distress Scale Cutoff Score

The PDS scores did not show a normal distribution (see Figure 1). The mean PDS score on a scale from 0 to 10 was 2.9 ± 3.0 with a median of 1.8. The first and third quartiles revealed scores of 0.3 and 5.3, respectively. Ninety-eight subjects (17%) reported a score of 0.

Fig. 1. Score distribution of the Psychological Distress Scale (PDS) (n = 561).

ROC analysis was used to determine whether scores on the PDS could validly distinguish whether or not a patient met criteria for clinically significant psychological distress as measured by the HADS cutoff score of 15 (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Kornblith and Batel-Copel1998; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005).

The ROC curve graphically represents the sensitivity and specificity coefficients that would be generated using each possible cutoff score in the PDS range, the accuracy of the cutoff score being determined by calculating the area under the curve (AUC). A cutoff score of 3 yielded the optimal ratio of sensitivity (.76) to specificity (.82) using the HADS cutoff score of 15 as a criterion for the presence of clinically significant distress (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. ROC curve analysis comparing the PDS scores to established HADS cutoff score; HADS cutoff value above or equal to 15.

For a cutoff value ≥3 for the PDS, we obtained a likelihood ratio for a positive test (LRP) of 4.22 and a likelihood ratio for a negative test (LRN) of 0.29. We also obtained a positive predictive value (or precision rate, i.e., proportion of patients with positive test results who are correctly diagnosed) of .69 and a negative predictive value (proportion of patients with negative test results who are correctly diagnosed) of .87, with a false-positive rate of 18% and a false-negative rate of 24% (see Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of correct and incorrect classifications when using the PDS cutoff of 3, with the HADS cutoff of 15 used as a classification criterion

For a cutoff value ≥3 for the PDS, the likelihood ratio for a positive test (LRP) is 4.22 and the likelihood ratio for a negative test (LRN) is 0.29.

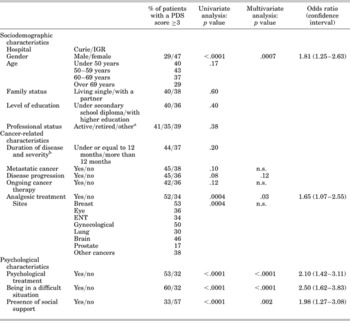

Relationship of Psychological Distress Scale Cutoff Score to Sociodemographic, Medical and Psychosocial Characteristics

The relationship between sociodemographic variables and scores that met or did not meet the PDS cutoff score of 3 evidenced gender (women demonstrating a higher PDS score than men) as the only significantly associated variable. Age was not related to PDS scores (see Table 3).

Table 3. Relationship of PDS cutoff score of 3 to sociodemographic, medical, and psychosocial variables

aHomemakers, unemployed, disabled.

bTwo missing data.

In univariate analyses, among clinical and psychosocial variables, scores above or below the PDS cutoff score of 3 were significantly related to tumor site, analgesic use, professional psychological help, perceived psychosocial difficulties, and perceived lack of social support. The psychological distress rate was 35% (195 patients) using the HADS cutoff score of 15, and 38% (215 patients) using the PDS cutoff score of 3. This prevalence varied according to tumor sites. The highest rates of psychological distress as measured by the PDS and the HADS were observed in breast, gynecological, and brain cancer patients, and the lowest in prostate cancer patients.

A nonsignificant trend toward higher PDS scores was observed for patients with a metastatic disease compared to local/loco-regional disease and for patients with disease progression compared to those in remission. Patients receiving cancer therapy at the time of the study presented higher PDS scores than those not currently receiving cancer therapy (i.e., patients returning for follow-up).

With regard to psychosocial variables, χ2 analyses were used to determine whether the scores above or below the PDS cutoff score of 3 were associated with the presence of each of the three psychosocial criteria; all were found to be very strongly correlated with psychological distress: Patients reporting financial, professional, or personal difficulties had higher scores than those not reporting such difficulties. Conversely, patients reporting support from their family and friends had lower scores.

A descending logistic regression analysis was performed, in which all order 1 interactions with tumor site were studied and including gender, level of education, professional status, tumor site, stage of disease, disease progression, ongoing cancer therapy, analgesic use, professional psychological help, perceived psychosocial difficulties, and lack of social support.

For all tumor sites, a significantly (or borderline) higher rate of distress was observed for women (p < .0007), patients presenting disease progression (p = .12), patients taking analgesics (p = .03), those receiving psychological intervention (p < .0001), those reporting psychosocial problems (p < .0001), and those perceiving a lack of social support (p < .002) (see odds ratio and confidence intervals in Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study indicate that the French version of the single-item Distress Thermometer, which we have called the Psychological Distress Scale, may be effective in detecting cancer patients with clinically significant distress. Using the HADS-established criterion for identifying psychological distress (score cutoff ≥ 15), a PDS cutoff score of 3 was found to possess optimal sensitivity (0.76) and specificity (0.82) to enable distinction between patients with clinically significant anxiety or depression and those without these disturbances.

This study provides additional information on the performance of a single-item psychological distress screening instrument on a culturally distinct cancer population compared to previous studies (Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007).

In a clinical setting, the sensitivity of an instrument is of primary importance, as it is crucial to keep rates of false negative as low as possible (Hall et al., Reference Hall, A'Hern and Fallowfield1999). However, threshold values may have to be determined by resources available to the staff. In this study, the specificity level is also good, indicating that few false positives (18%) will occur, reducing the overall misclassification rate and increasing the reliability of the clinical test in detecting cases.

The PDS screening procedure appeared acceptable in this large mixed-site cancer patient sample, distributed fairly evenly in terms of age, gender, and educational level, and approached in two major cancer centers in France serving a wide range of cancer population. The screening procedure appeared acceptable with a 94% response rate. Moreover, PDS scores varied in the expected direction with psychosocial characteristics such as perceived social support and emotional, professional, or financial difficulties. Additional findings were that patients who scored at or above the PDS cutoff of 3 were more likely to be female, to be taking analgesics, to be receiving professional psychological help, and to present progression.

The cutoff score of 3 found is this study is lower than those (cutoffs of 4 or 5) found previously in mixed cancer site samples and using the HADS or BSI as comparative screening instruments (Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007). With these clinical thresholds, these studies obtained DT levels of sensitivity and specificity of 84% and 61% (Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003), 77% and 68% (Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005), and 73% and 59% (Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007).

Linguistic, cultural, and methodological factors may be suggested to explain these differences. First, the French translation of the word “distress” connotes more intense psychological suffering than in English, and this may also differ from other languages associated with the use of the distress thermometer. In addition, although there may indeed be cross-cultural differences in terms of word meaning, there may also be differences in the actual reporting of psychological distress (Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005). Second, the adaptation of the thermometer picture to a 10-cm vertical line may affect the way in which patients respond to the instructions. Moreover, the use of different screening tools (e.g., HADS or BSI) or cutoff values (e.g., HADS ≥ 10/11 or 15) with which the distress thermometer was compared, may also explain the discrepancies with our results.

A higher DT cutoff score (cutoff = 4) has also been found in bone marrow transplant patients (Ransom et al., Reference Ransom, Jacobsen and Booth-Jones2006), highlighting the possibility that clinical factors may also influence the choice of score thresholds. Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Zevon and D'Arrigo2004) underlined the difficulty in determining a single cutoff score that could clearly maximize sensitivity and specificity across clinical conditions. The prevalence of psychological disorders varies according to patients' clinical characteristics (type of tumor, stage of disease, time since diagnosis, modes of treatment, etc.); a high prevalence would justify privileging cutoff scores associated with greater sensitivity (Razavi et al., Reference Razavi, Delvaux and Brédart1992).

With this lower PDS cutoff score of 3 associated with a low false positive rate (18%), 38% patients were identified as presenting clinical psychological distress. This psychological distress rate observed in a French cancer patient population, although more elevated, compares with similar rates of emotional distress during the course of cancer in North America (Zabora, Reference Zabora, Rowland and Holland1998; Carlson & Bultz, Reference Carlson and Bultz2003; Hegel et al., Reference Hegel, Moore and Collins2006) as well as in other European countries (Brédart et al., Reference Brédart, Didier and Robertson1999; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005; Strong et al., Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2007).

Large cross-sectional studies have identified that female gender, younger age, active or advanced disease, pain, and financial or material challenges were predictive of greater emotional distress (Aass et al., Reference Aass, Fossa and Dahl1997; Brédart et al., Reference Brédart, Didier and Robertson1999; Skarstein et al., Reference Skarstein, Aass and Fossa2000; Zabora et al., Reference Zabora, Brintzenhofeszoc and Curbow2001; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Angen and Cullum2004; Strong et al., Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2007). In this study, female gender, taking analgesics, receiving psychological/psychiatric help, perceived psychosocial difficulties, lack of social support, and the various aspects of the quality of life profile were all found to be associated with psychological distress. Concerning the relationship between self-reported measures of distress and quality of life or perceived psychosocial difficulties, the cross-sectional design of this study does not enable determination of causal relationships. However, it may be that the level of each outcome measure tends to be predictive of the other; physical and psychosocial problems and psychological distress appear largely interrelated. Moreover, other studies have underlined the distressing nature of many physical symptoms (Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005); the association between PDS scores in this study and symptom scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 may reflect this observation.

The PDS scores were more significantly associated with the HADS anxiety subscale. This compares to Gil et al. (Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005) and Patrick-Miller et al. (Reference Patrick-Miller, Broccoli and Levine2004), suggesting that the PDS assesses anxiety, whereas it explores depression to a lesser extent.

Patients receiving professional psychological help were those with the greatest psychological distress. Considering that among these patients, 75% were receiving psychotropic drugs, we might question the efficacy of this medical treatment to alleviate their psychological disorders; however, this relationship may also reflect a history of anxiety and depressive disorders, which is a risk factor for psychological distress (Harrison & Maguire, Reference Harrison and Maguire1994).

After adjustment for other factors, we did not confirm any association between psychological distress and tumor site. The few studies that have compared the prevalence of psychological morbidity according to tumor site did not demonstrate any link after taking into account symptoms such as pain. Other studies are required to determine whether there are any differences related to the disease itself or whether these differences can be explained by adverse effects of treatments or physical symptoms, for example (Pinder et al., Reference Pinder, Ramirez and Black1993).

A limitation of this study is the use of a psychometric tool (the HADS) to assess psychological morbidity and determine a PDS cutoff score on this basis, although we followed the same methodology as other investigations (Patrick-Miller et al., Reference Patrick-Miller, Broccoli and Levine2004; Gil et al., Reference Gil, Grassi and Travado2005; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Donovan and Trask2005; Ransom et al., Reference Ransom, Jacobsen and Booth-Jones2006; Ozalp et al., Reference Ozalp, Cankurtaran and Soygür2007). A clinical interview would have avoided the risk of patient misclassification. As reported previously, the HADS rate of false positives ranges from 15% to 20%. International psychometric and clinical data from the HADS indicate that the instrument's psychometric performance is good (Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Elsworth and Sprangers2004). Besides, even clinical interviews may evidence diagnostic errors because, for example, they may lack the specific criteria to diagnose anxiety or depressive disorders in the medical patients. No interview schedule is completely reliable: for instance, a reported 61% concordance in cases of psychiatric illness between the Psychiatric Assessment Schedule and the Present State Examination (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Surtees and Sashidharan1983). The aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of a psychological distress screening procedure and to provide an effective tool to detect potential cases of psychological distress to refer to the psycho-oncology service for a more detailed psychiatric assessment. We chose a HADS threshold score of 15, maximizing HADS accuracy in identifying clinical cases.

A second limitation of this study relates to the study sample characteristics, composed of relatively few metastatic patients, only cancer outpatients, and patients recruited in urban cancer centers, restricting the scope for generalizing the results.

Finally, the present study design does not inform on the efficacy of a psychological screening procedure, which is a prerequisite to early detection and referral of psychologically distressed cancer patients. To date, studies addressing the effectiveness of a psychological distress screening program have shown that, among patients receiving minimal psychosocial intervention as part of their initial cancer care, a distress screening program did not improve quality of life. Earlier, Maguire et al. (Reference Maguire, Tait and Brooke1980, Reference Maguire, Brooke and Tait1983) had found that systematic monitoring of newly diagnosed cancer patients resulted in better recognition and appropriate psychosocial management of patients with adaptation problems. Recent meta-analyses suggest that preventative psychological interventions in cancer patients may have a moderate clinical effect upon anxiety but not on depression (Sheard & Maguire, Reference Sheard and Maguire1999).

Further research should also address the overall psychometric performance (validity, reliability, responsiveness) of the PDS to enable this tool to be used as a clinical research instrument (De Boer et al., Reference De Boer, van Lanschot and Stalmeier2004).

CONCLUSION

Our study has enabled us to validate the PDS, a French version of the distress thermometer developed by the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2003) for detecting the presence and, subsequently, when necessary, the intensity of psychological distress in a cancer patient population. This tool can also be used to identify a number of factors (sociodemographic and cancer-related characteristics) liable to influence distress.

Improvement of the quality of care provided for cancer patients must take into account all aspects of the patient's daily life, particularly his or her psychological state. With growth of holistic patient management, psychosocial approaches will need to be developed and encouraged in cancer care centers. It is important to develop methods allowing detection of the patients with the greatest psychological difficulties, who are often neglected in daily medical practice due to a lack of time and resources, by using a simple and flexible methodology (Cull et al., Reference Cull, Stewart and Altman1995). As proposed by certain authors (Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Howell and Maguire1991; Roth et al., Reference Roth, Kornblith and Batel-Copel1998), a two-stage process of assessment could be used: After screening for psychological distress in all patients using simple self-administered questionnaires, patients presenting scores above the cutoff value could then be assessed further, for example, by a specialist nurse (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Akechi and Okamura2005). This would provide a practical way of identifying patients in real need of specific psycho-oncological intervention.

A generalization of this method, allowing detection of anxiety and depression disorders and quality of life assessment, is acceptable for the patient and for the oncologist and could result in more effective psycho-oncological management of cancer patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jimmie C. Holland and Dr. Andrew Roth for their permission to use the distress thermometer and for their advice.

We thank the following departments of the Institut Curie in Paris and the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif for their cooperation in this study: departments of Chemotherapy, Surgery, Gynecology, Neurology, Ophthalmology, Ear, Nose and Throat, Respiratory Medicine, Radiotherapy, and Urology. We also thank the staff of the Institut Curie in Paris and the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif for their technical contributions to this study, doctors, nursing administrators, nurses, committees, and all reception personnel. We thank all staff of the Institut Curie Biostatistics Department for statistical analyses for this study. Finally, we thank all patients for their participation in this study. This research was sponsored by Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRC), France.