Introduction

This article evaluates developments in the Cuban healthcare system throughout the 2006–20 period and their interaction with recent demographic trends. Based on comprehensive statistical series, it examines the evolution of health indicators, trends in physical infrastructure and availability of physicians, and the domestic effects of medical-services exports. The aim is to assess the long-term consequences for the financial sustainability of the system of universal free access to healthcare, recently aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic. It also considers Cuba's accelerating ageing process, given that Cuba has the oldest population in Latin America, and how ageing adversely impacts the healthcare system.

In assessing the academic healthcare literature on Cuba, we identify two contrasting perspectives regarding the accessibility, quality, efficiency and sustainability of the system.Footnote 1 The first, embraced by the Cuban government, its official media and many scholars, maintains that Cuba is a ‘medical power’ that, despite modest temporary dislocations, provides universal free access to services and sends medical missions abroad. As an early example of this perspective, in 1979 Ross Danielson asserted: ‘[…] the Cuban Revolution made possible what was impossible in the hopeless cynical and forever stymied prerevolutionary sociopolitical context, the expansion of rural services and the rationalization of urban facilities and fragmented public health programs’.Footnote 2

During the worst year of the 1990s economic crisis, but with only passing references to its adverse effects, another analyst, Julie Margot Feinsilver, concluded that Cuba became a ‘showcase for achievement in health’.Footnote 3 Such a view dovetailed with assessments by directors of the World Health Organization (WHO) and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Feinsilver further affirmed that Cuban healthcare data was ‘of very high quality’, while highlighting the importance of ‘medical diplomacy’ as a manifestation of such achievements.Footnote 4 According to Feinsilver, Cuba ‘made very impressive gains in the health sphere, not only in and of themselves but also because the government uses them successfully for symbolic advantage’.Footnote 5 A more recent book praises the primary-care system, alluding to its significance in terms of providing universal free access to healthcare but failing to note how access is reduced by Cuba's family-doctor exports.Footnote 6

A contrasting perspective criticises Cuba's system while acknowledging limited accomplishments and contends that the ‘enthusiastic’ assessment of healthcare in Cuba, ‘shared by many in the global public health community, is nourished by attention to only a few indicators and the reliance on information provided by a deceptive state’.Footnote 7 This perspective argues that Cuban healthcare achievements often come at the expense of human rights, including suppression of dissenting academic views, forceful restraint of people with HIV, and medical internationalism tantamount to human trafficking.Footnote 8 Another critical account, which originally intended to document alleged achievements, found major flaws. The author, Katherine Hirschfeld, embarked on a one-year anthropological field-research project on the island; while there, she was hospitalised for dengue and ascertained that the outbreak's severity was seriously under-reported, while seeing first-hand the poor treatment accorded to hospitalised patients. Only when doctors revealed the epidemic's real scale did the official press acknowledge its severity.Footnote 9

A more nuanced ‘balanced’ perspective acknowledges Cuba's healthcare achievements, while documenting its shortcomings. Elizabeth Kath, for example, adopts this perspective and notes the ‘paradox’ between Cuba's ‘poor record on economic development’ and its ‘exceptionally positive health indicators’.Footnote 10 She comments on the polarised views the topic generates between ‘over-optimistic and pessimistic rhetoric’, difficulties in identifying objective analyses, and how ‘a moderate position can meet with hostility from both poles’.Footnote 11 The Cuban healthcare system is – despite its merits – flawed because, as stated by Kath, ‘central state authorities […] retain a monopoly over decisions regarding public health goals and policies’, decisions which lead to unintended consequences undermining ‘the quality of healthcare and the system chances of long-term sustainability’.Footnote 12 The latter is a key point underlining our contribution as it is our contention that, despite its merits and relative advantages, the centralised nature of the Cuban public health system has considerable shortcomings.

We favour a ‘balanced’ perspective because the antagonistic positions are permeated by ideology whereas our perspective rests on official statistics and academic articles that strengthen objectivity by assessing positive and negative features of the healthcare system.

At the end of the 1980s, Cuba's health indicators were among the best in Latin America and more favourable than those of some socialist countries. They eroded badly during the severe 1990s economic crisis following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist camp (‘The Special Period in Time of Peace’). Despite a modest recovery early in the twenty-first century, healthcare continued to deteriorate, with many indicators presently performing worse than before the crisis. We draw conclusions through an analysis of the most comprehensive statistical series assembled, including data on gross domestic product (GDP) and healthcare budgetary expenditures; trends in hospital, polyclinic and personnel numbers; medicine availability; hygienic standards; and so forth.Footnote 13 The deterioration resulted primarily from the combined confluence of three factors: (i) the persistence of central planning, even with Raúl Castro's ‘structural reforms’ (transformations intended to modestly change important aspects of the economy to move it closer to the market, but that were insufficient, faced many restrictions and were halted in 2016, with some being reactivated in July 2020); (ii) the drastic decline in Venezuela's economic support since 2012–13; and (iii) the punitive sanctions imposed by President Trump to strengthen the US embargo. A more recent extraneous factor was the eruption of Covid-19 in early 2020.

Population ageing further aggravates the deteriorating healthcare situation. Contrary to the scholarly debate on the healthcare system, there is unanimity in the literature regarding the magnitude of the ageing situation and its adverse consequences. The ageing of Cuba's population, which is particularly rapid given the country's history of below-replacement fertility since the 1970s and accentuated by large-scale emigration of working-age adults, will make the country's population among the world's oldest. The healthcare expenditure implications of such transformation are massive as the elderly disease profile is dominated by degenerative and end-of-life diseases that are more costly to treat than those afflicting the young.

This article contributes to the debate on Cuba's healthcare system by: (i) showing that Cuba's system of universal free access to healthcare is financially unsustainable in the long run; (ii) demonstrating that the current healthcare resource allocation is inappropriate to address the elderly's needs; (iii) analysing the economic significance and sustainability of Cuban professional healthcare-services exports; and (iv) describing the negative impacts of ageing on healthcare. These contributions are pioneering in the Cuban healthcare-policy literature while relevant to other Latin American countries facing similar challenges.

The Healthcare System

The legitimacy of the Cuban Revolution has rested on its commitment to provide universal free access to healthcare, a pledge sustained despite recurrent economic trials. Fidel Castro vowed to make Cuba a ‘medical power’, assigning symbolic value to this oath as it provided legitimacy to the transformations promoted by the revolutionary regime.

While the healthcare system claims some noteworthy achievements, its quality deteriorated, as noted, during the 1990s economic crisis. It partially recovered in the early 2000s, largely as a result of Venezuelan subsidies and the normalisation of US–Cuban relations under President Obama. By the mid-2010s, as the economy worsened, additional setbacks occurred in terms of access to and quality of healthcare. These were partly associated with reductions in facilities and healthcare personnel, some dictated by awareness of the long-term financial sustainability of the universal healthcare system being jeopardised by resource scarcities. Challenges facing the system transcend persistent economic difficulties, as other factors are at play. A noteworthy aspect of Cuba's healthcare system is the priority assigned to physician training, a feature with ramifications beyond improving health standards, as it has become a mechanism whereby Cuba cultivates political support from other nations – through internationalist medical missions – while making medical-services exports the country's major foreign-revenue source.

Status Indicators: Positive and Adverse

The most positive development from 2007 to 2018 was an apparent 24.5 per cent decline in the infant mortality rate (IMR), from 5.3 to 4.0 per 1,000 live births, the second-lowest IMR in the western hemisphere (see Table 1). Contributing factors were extensive vaccination programmes (vaccination rates for 11 communicable diseases attained universal coverage), availability of prenatal care for expectant mothers (through the family-doctor network), deliveries in hospital facilities, and post-partum neonatal services.

Table 1. Health Indicators in Cuba, 2007–18

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on ONEI, Anuarios estadísticos de Cuba (2007 to 2018); MINSAP, Anuario estadístico de salud (2018).

Notes: aPercentage difference between 2007 and 2018

b Per 1,000 inhabitants

c Per 1,000 live births

d Per 100,000 live births

e Average of real beds per 1,000 inhabitants.

Another development behind the low IMR is a national programme, implemented since the 1980s, to detect congenital malformations and encourage expectant mothers to undergo therapeutic abortions when abnormalities are detected.Footnote 14 Abortion is commonly used as (or as a supplement to) a contraceptive method; the procedure is available on demand at no cost to women. As a result, 85,045 abortions were performed in 2018 (42 per cent of pregnant women have abortions, i.e. 73 abortions for every 100 births).Footnote 15 Moreover, findings from a study documented in various sources show significant statistical inconsistencies that suggest the low IMR is consistently underestimated:Footnote 16 Cuban estimates are at variance with biological patterns observed in a robust analysis conducted with reliable data from a number of European Union countries. In these populations, the number of neonatal deaths and foetal deaths stays within a certain range due to common determinants. Cuba's ratio of six is a clear outlier and suggests that physicians – to meet government IMR targets – reclassify early neonatal deaths as late foetal deaths, thus deflating the estimates. When adjusted for this bias, the 2014 Cuban IMR of 5.79, for example, is actually between 7.45 and 11.16. Such correction implies a corresponding downward adjustment in assumed life-expectancy-at-birth estimates, another healthcare achievement for which Cuba is praised although, in light of these biases, such life-expectancy gains appear to be less appreciable than assumed.

Despite the downward adjustment, Cuba, like some of the more advanced Latin American countries, has continued achieving minor life-expectancy gains,Footnote 17 notable because substantial gains become increasingly difficult to attain as a country approaches the highest currently attainable life-expectancy levels of Japan.Footnote 18 Such life-expectancy gains are not reflected in Cuba's rising crude death rate; higher age-specific mortality rates at older ages, combined with a rising elderly-population share, misleadingly portray a worsening mortality trend for 2007–18. On the negative side, and for the same period, Cuba exhibited a 41 per cent rise in the maternal mortality rate (as in the 1990s). Determinants of this adverse trend are not understood, but appear to be associated with differential access to socio-economic resources. A recent study (for 2002–18) found that within the overall upward trend, maternal mortality declined among ‘White’ women, whereas it rose among more socially disadvantaged ‘non-White’ women.Footnote 19 The high incidence of induced abortion as a birth-control method is likely to be implicated.Footnote 20

Some of these public health achievements are facilitated by Cuban laboratories’ capabilities to produce medications for the domestic market despite foreign-exchange shortfalls. This is supplemented by the national biotechnology industry's capability to explore the feasibility of novel medical treatments. And yet, production of medicines probably declined in the 2016–18 period (more on this later), whereas the biotechnology industry suffered a significant exodus of personnel and capture of profits by the state.Footnote 21

An Evolving Disease Profile

Outcomes regarding the prevalence of infectious diseases of mandatory reporting are largely positive. In 2007, out of 19 such diseases, three were not present (typhoid fever, rabies and tetanus) and another three had very low rates (brucellosis, meningococcus and malaria). Among the remaining 13, seven showed declining trends (blennorrhagia, acute diarrhoea, scarlet fever, food intoxication, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)) and six had increasing or stagnant trends (acute respiratory diseases, syphilis, chickenpox, viral meningoencephalitis, bacterial meningoencephalitis and leprosy).Footnote 22 However, neither the Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información (National Office of Statistics and Information, ONEI) nor the Ministerio de Salud Pública (Ministry of Public Health, MINSAP) publishes statistics regarding recurring dengue, zika and chikungunya, epidemics associated with the Aedes aegypti mosquito known to frequently occur. In 2018, MINSAP reported dengue outbreaks in five Cuban provinces, resulting in several deaths.Footnote 23 In 2017, a zika outbreak of 1,384 cases went unnoticed by PAHO and was not revealed until 2019.Footnote 24 These outbreaks usually peak in the hottest summer rainy months as mosquitos’ breeding grounds expand (in urban areas, poor maintenance of water distribution pipes and sewers also contribute) and refuse-collection systems are inadequate – allegedly, 40 per cent of the refuse-collection equipment in 2014 was non-operational.Footnote 25

Additionally, as reported by PAHO, Cuba has experienced several cholera outbreaks. An international vaccination alert noted that 700 cases have been reported since July 2012, including three deaths. One outbreak impacted six Cuban provinces and the disease was also detected among visitors returning to the United States.Footnote 26 The outbreak's origins are not certain but may be traced to cholera's presence in nearby Haiti or, just as likely, to imported cases brought by healthcare personnel stationed overseas. Haemorrhagic conjunctivitis, a disease transmitted by flies, roaches and other insects, has also been reported.Footnote 27

Like many other countries with advanced mortality regimes, Cuba is also experiencing mortality increases due to degenerative diseases associated with an older age structure, such as ischaemic heart disease, stroke and several types of cancer. Smoking prevalence among adults in Cuba is one of the highest in the world, which explains the island's high lung-cancer mortality rates.Footnote 28 Mortality rates are also high for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases associated with tobacco consumption. Overall, Cuba experiences among the highest rates in Latin America for all types of cancer. A rising incidence of Alzheimer's and other brain-related disorders currently impacts 10 per cent of the population aged 65 or over, a trend expected to accelerate with continued population ageing. From 2007 to 2017, for example, the Alzheimer's death rate increased by 28.1 per cent.Footnote 29 The number of elderly people suffering from dementias, including Alzheimer's, is projected to rise by 2030 to 300,000 cases, or 15 per cent of the adult population.Footnote 30

Trends in the Physical Healthcare Infrastructure

The economic challenges facing Cuba, together with limited access to foreign exchange and the export of medical services, contribute to a worsening physical healthcare infrastructure and a reduction in healthcare personnel. The limited investment resources available are assigned to sectors capable of generating foreign revenue and creating employment (like the development and maintenance of the tourist infrastructure, including hotels and airports), to the detriment of other national priorities (such as the neglected housing sector). Since the 1990s, this strategy has led to the neglect of Cuba's general infrastructure, including old and obsolete urban water distribution and sewer systems (mostly dating to the early twentieth century) as well as refuse-collection facilities, whose conditions have worsened severely.Footnote 31 While more investment resources have been allocated to medical-personnel training (medical exports being a major source of foreign revenue), this budget line item is only likely to account for a small portion of total government expenditures, but it is not reported separately.

A Smaller and Deteriorating Healthcare Infrastructure

From 2007 to 2018 there was a decline in the number of healthcare facilities: hospitals by 32 per cent (all rural hospitals were shut down after 2011), polyclinics by 9 per cent, and all rural and urban posts were closed after 2010 whereas the number of hospital beds decreased by 5 per cent (see Table 1). Since rural hospitals were eliminated, patients have been transferred to regional hospitals but, if far away, the health risks increase, particularly during emergencies.

The closing of some healthcare facilities could be viewed as a rational response to evolving demographic trends (declining population growth rates and increased urbanisation) and economic and education policy changes that partially altered the geographic demand for healthcare services. In particular, the closure of rural hospitals likely resulted from the deactivation of more than 80 sugar mills since 2002. Another contributing factor was the 2009 closure of the ‘Schools in the Countryside’ programme, which affected more than 500 rural-based schools, some of which included small healthcare facilities.Footnote 32 These two policies, and rural-to-urban migration due to agriculture's general neglect since the 1990s economic crisis, partly explain the reduction in rural healthcare facilities. Significantly, the closure of rural and semi-rural medical facilities disproportionally and negatively impacts the healthcare of the aged as they are less prone to migrate to urban locations than the young.

Complicating matters is the healthcare system's excess of gynaecological and paediatric hospitals. Although this was appropriate when fertility rates were higher, it is not consistent with current requirements when the country only has a single geriatric hospital. Moreover, there is a severe shortage of residential facilities for the elderly (e.g. assisted living and nursing homes).Footnote 33

Physical healthcare infrastructure continues to suffer as resources are unavailable to undertake routine maintenance and the most basic repairs. Limited investments often yield meagre results as items such as windows, taps, showerheads, light switches and bulbs are stolen for private use or sale on the black market. In addition, there is poor maintenance of basic sanitary equipment, such as toilets, washbasins and pipes, which are often clogged due to the inadequate disposal of waste and recurrent water shortages. Furthermore, contrary to the government's claim that revenues generated by internationalist medical missions are reinvested in the national healthcare system, two observers who examined ONEI data concluded that out of the hard-currency revenue generated in 2017 by the foreign missions, only approximately 3 per cent was allocated to health and social expenditures.Footnote 34

Availability of Physicians, Their Export and Effects on Domestic Access and Quality of Services

Since the beginning of the Revolution, the government has allocated a disproportionate amount of resources to revamping the national healthcare system (including developing novel primary healthcare approaches) and greatly expanded training for physicians and other healthcare personnel. This, in part, led to Cuba's policy of providing other countries with growing numbers of Cuban physicians as well offering training for foreign physicians.Footnote 35 Initially, this was done strategically for countries sharing Cuba's political and/or ideological ties. Eventually, the scheme was expanded and Cuba became a major provider of medical-services exports, the country's current main source of hard currency (13.8 per cent of GDP at its peak in 2013, although declining thereafter).Footnote 36

Physician Training Policy: Desirability and Effects on Other National Educational Priorities

Another important factor explaining the Cuban government's ability to expand physician training is that in a centrally planned economy, the state assigns resources to priority targets it chooses, often with adverse effects. For instance, an increase in medicine graduates was achieved at the cost of less training in disciplines essential for Cuba's economic development. Under Fidel Castro's ‘Battle of Ideas’, university enrolment was expanded by 208 per cent between the 1989/90 and 2007/8 academic years but, while enrolments in medicine grew by 403 per cent, enrolments in technical sciences and agricultural sciences rose by only 43 per cent and 38 per cent respectively, while enrolments in natural sciences and mathematics declined by 39 per cent.

Despite Raúl Castro's eventual structural reforms, the neglect of training for careers essential for Cuba's economic development continued in 2018. Inflated university enrolments were reduced between the 2007/8 and 2016/17 academic years: technical sciences and agricultural sciences declined by 26 per cent and 36 per cent respectively, while natural sciences and mathematics remained stagnant. The percentage distribution of enrolment by disciplines in the 2018/19 academic year shows medicine's share was the highest at 36 per cent, whereas technical sciences stood at 12 per cent, agricultural sciences at 5 per cent and natural sciences and mathematics at 2 per cent, the last two well below physical education at 7 per cent.Footnote 37 In the last 30 years, as medical exports became an increasing source of hard-currency earnings, the Cuban leadership has allocated resources away from economic development fields to expand physician training. Spending on scientific development fell from 1 per cent of GDP at the start of the 1990s to 0.4 per cent in 2016; by 2017 some measures had been taken to reverse this trend.Footnote 38

Young Cuban students find a medical career attractive not only for the high status accorded to this profession everywhere but also, in Cuba's case, for the symbolic and political value assigned to medical doctors by the Revolution's leadership. Cuban physicians receive an average domestic monthly salary of US$50 – a wage rate they could multiply manyfold while serving abroad, with the added benefit of purchasing and bringing back consumer goods not available at home. Recent developments suggest the idealised portrayal of the medical education programme and its internationalist dimensions is more complex than generally assumed. These developments include the continuous defection of medical personnel abroad and documented allegations of violations of international labour and human rights,Footnote 39 such as only partial compensation for professional services rendered and working conditions akin to forced labour.Footnote 40

Demand for Cuban Medical Services

The appeal of Cuba's healthcare system, and its ultimate developing-country desirability, is that it emphasises, although not exclusively, the provision of primary healthcare. Through this optic, prevalent maladies,Footnote 41 such as infectious diseases and other poverty-related ailments, could be diagnosed, cured or prevented with relative ease. Basic medical training, willingness to work in inaccessible or dangerous localities, close monitoring of the population being served, limited but effective essential medication lists, medical testing kits and vaccines are among the crucial tools of the family-doctor arsenal. Thus, Cuban internationalist doctors help satisfy significant under-served healthcare niches not covered by national health systems in many countries.

Currently Cuba has by far the highest physician-to-patient ratio (per 1,000 people) in the world.Footnote 42 Data culled from multiple national sources, mostly referring to the early to mid-2010s, indicates the range of physician-to-patient ratios is wide indeed, as low as 0.02 in some of the poorest countries. In contrast, better-served countries generally boast rates of around or above four. At the upper range, three countries stood out as outliers in 2014: Greece (6.26), Monaco (6.65) and, most of all, Cuba (7.52). By 2018 Cuba's ratio had reached 8.19, or double that of the majority of countries with the greatest relative abundance of doctors.Footnote 43

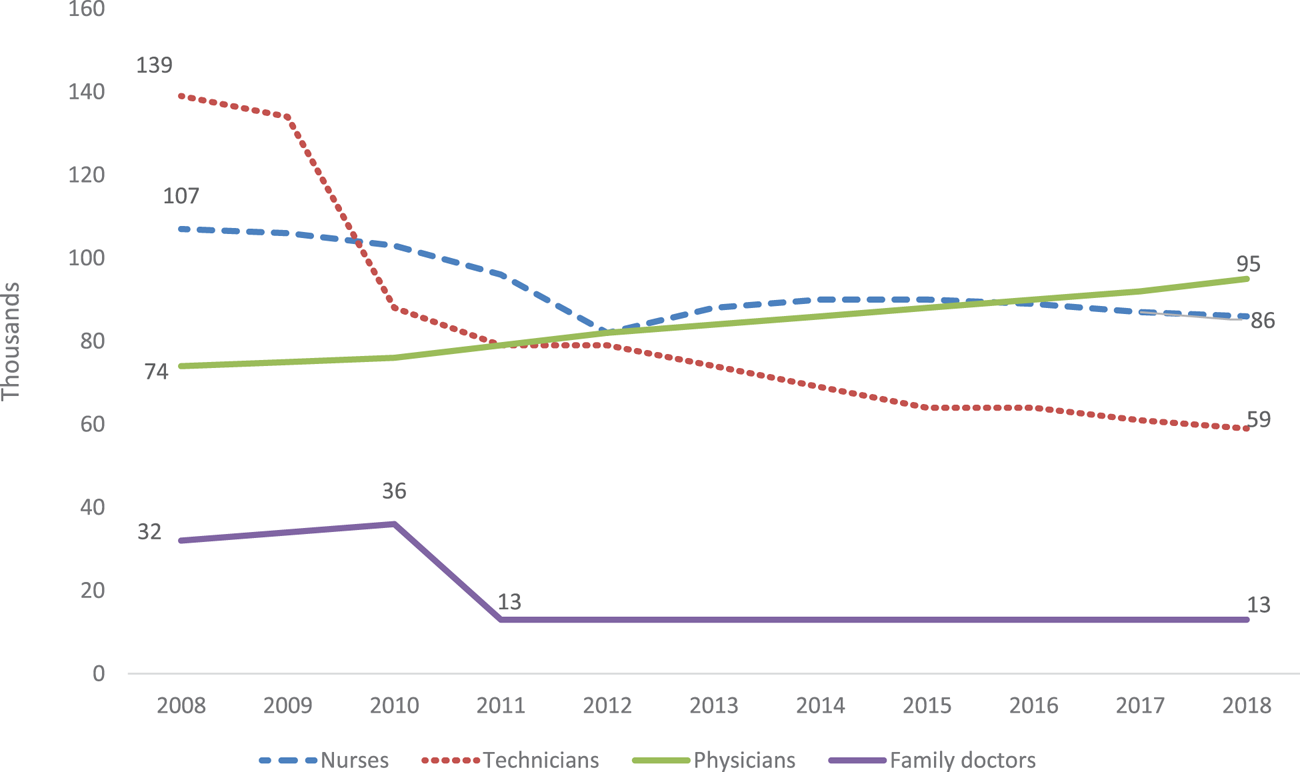

The stock of medical graduates has increased but the actual number of physicians serving the Cuban population is much lower because internationalist missions take many physicians and other healthcare personnel away. As of 2017, about 40,000 medical graduates were working in Venezuela, Brazil, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Ghana, Angola and elsewhere. As a result, rather than having a 2018 patient-to-physician ratio of 118 (conversely, a physician-to-patient ratio of 8.51), as officially claimed, the actual ratio was probably 202 (or 4.95), which is closer to the 1990 ratio (274, or 3.62), just as the 1990s economic crisis was getting underway. The relative ‘dearth’ of physicians is more acute for certain medical specialties; the share of those specialists employed overseas is higher than that of general practitioners. More problematic is the curtailment of the ‘Family Doctor’ programme, a highly successful initiative launched during the 1980s whereby primary-care physicians reside in communities they serve to monitor residents’ health. From 2008 to 2018 the number of family doctors shrank by 59 per cent, while the number of family-doctor locations declined by 23 per cent. The stock of healthcare personnel, other than doctors, also declined. From 2008 to 2018, these roles decreased by 22 per cent overall: health technicians by 58 per cent and nursing staff by 20 per cent (see Figure 1). Meanwhile, the physician stock increased by 28 per cent as national medical schools continued producing graduates, setting a new record in 2018 when the overall number reached 95,487.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Trends in Health Personnel in Cuba, 2008–18

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on ONEI, Anuarios estadísticos de Cuba (2008 to 2017).

The decline in the Cuban physician-to-population ratio must be examined in this context. In tandem with the decline in the number of primary-care doctors serving Cuban patients, the number of family-doctor offices was reduced from 14,671 in 2001 to 10,869 in 2017. In more rural provinces, the decline was more significant: 438 fewer family-doctor offices in Pinar del Río; 325 in Sancti Spíritus; 257 in Santa Clara; 236 in Camagüey; and 224 in Holguín. The number of polyclinics where secondary care is offered by medical and other specialists (type and number varying from one polyclinic to the next) in paediatrics, cardiology, dentistry, social work, etc. was also reduced by 8 per cent, from 491 in 2007 to 450 in 2017 (see Table 1).

Is There a Domestic Physician Shortage?

These changes seem to have disproportionately impacted overall healthcare, given the crucial role assigned to family doctors at the primary level of care; it is at this level where most minor illnesses are addressed, as are acute respiratory ailments, which were reported to have increased by 24 per cent between 2006 and 2017.Footnote 45As a result, Cubans, previously accustomed to more responsive levels of service, are reported to be dissatisfied and often face delays when seeking medical care.Footnote 46

Another factor contributing to the relative scarcity of healthcare personnel and facilities – other than those resulting from budgetary cuts (to be analysed later), closure of hospitals and healthcare posts, and internationalist missions – is that many physicians and healthcare workers are leaving the sector because they are dissatisfied with low wages.Footnote 47 The mean monthly state salary in the healthcare sector of 808 national pesos (CUP), or US$32, in 2018,Footnote 48 only covered 35 per cent of the basket of basic goods and services for 1.5 people (2,292 CUP).Footnote 49 Given this situation, some healthcare workers have abandoned their careers and moved to the expanding self-employment or tourism sectors, or emigrated. While the export of healthcare services brought Cuba US$6.4 billion in 2018,Footnote 50 it did little to improve domestic healthcare salaries, while constraining the availability of services. The much-diminished national stock of poorly paid healthcare workers must continue servicing the needs of the country's population. Making matters worse, as the age distribution changes, is a lopsided distribution of medical specialists. While in 2018 there were 305 children per paediatrician, there were 2,465 elderly people per geriatric specialist (see Table 2); with the physician supply relatively stable, the young cohort contracting and the old cohort expanding, the gap is widening.

Table 2. Children and Elderly per Specialised Physicians in Cuba, 2018

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data on physicians from MINSAP, Anuario estadístico de salud (2018); data on target population from ONEI, Anuario estadístico de Cuba (2018).

Notes: aPopulation 0–14 years old

b Population 60 years old and over.

Physician ‘shortages’ are likely to ease following the Cuban government's announcement in late 2018 that it was terminating the ‘Mais Medicos’ (‘More Doctors’) programme in Brazil due to a disagreement with the new conservative government there.Footnote 51 By mid-December 2018, most of the 8,300 internationalist physicians serving in Brazil had returned and it was reported that 836 did not.Footnote 52 In addition, in 2019 medical missions in Bolivia and Ecuador were terminated following political developments in these two countries. The impact this development will have on the national physician-to-population ratio is difficult to gauge as Cuba is intent on continuing to export significant contingents of doctors to other destinations. Just as the return of the physicians from Brazil was getting underway, a new contingent of 500 doctors was dispatched to Venezuela.Footnote 53 In 2020, in the context of an increasing demand for doctors in many countries due to the Covid-19 pandemic, 200 Cuban physicians were sent to Argentina, 600 to Mexico and an undisclosed number to other countries.Footnote 54

Shortages of Medicines and Other Inputs

Production of medicines steadily rose from 2007 to 2015 but declined by 15 per cent in 2016 and then the statistical series reporting their availability was discontinued, which commonly implies a further decrease.Footnote 55 Since 2014 there have been medicine shortages, partly an outcome of the inability to access foreign credits to import medications and pharmaceutical supplies due to US$1.5 billion in unpaid debt to suppliers. This situation prevents domestic laboratories from accessing inputs (85 per cent originate from China, India and Europe), including containers (92 per cent are imported) necessary to produce and package medications. By March 2017, upwards of 12 per cent of the 801 medications on the national essential medicines list were in short supply or unavailable; of these, 80 per cent could be produced locally, the remainder imported.Footnote 56 The shortages – similar albeit smaller than in the 1990s – have led to price inflation, with some medications’ costs increasing fourfold: 30 tablets of meprobamate, a tranquilliser, sell for 120 CUP, or 15 per cent of the mean state salary.

An assessment of the pharmaceutical sector, published in 2017 in the official media, based on pharmacy site visits, interviews with government officials and a MINSAP inspection of the 2,148 pharmacies in the country, concluded that many problems were endemic. According to the inspection, the national pharmacy system's deterioration, including black-market sales, was attributable to issues ranging from labour indiscipline and criminal activities, to problems related to infrastructure and organisation.Footnote 57 To confront such problems, among other measures, MINSAP introduced a revised essential medicines list. In addition, reliance on traditional medicine and herbs as well as acupuncture (as in the 1990s) is being promoted but these interventions may only be partially effective or ineffectual when treating serious medical conditions.

Disposable products such as needles, syringes and surgical tubes are repeatedly utilised with different patients despite the recommended one-time exclusive usage.Footnote 58 Generally patients and their relatives must supply basic day-to-day hospital necessities such as pillows, bed sheets, light bulbs, toilet paper and even food as they are unavailable in medical facilities.

Ageing and Its Impact on Health

For several years now, Cuba has been the Latin American country with the oldest population and among the most rapidly ageing countries in the world. Whereas in 2017 the United Nations’ Population Division ranked the island as the 50th-oldest country (with 20 per cent of its population aged 60 or over), by 2050 it is expected to rank as the 12th-oldest country (38.2 per cent will be aged 60 or over).

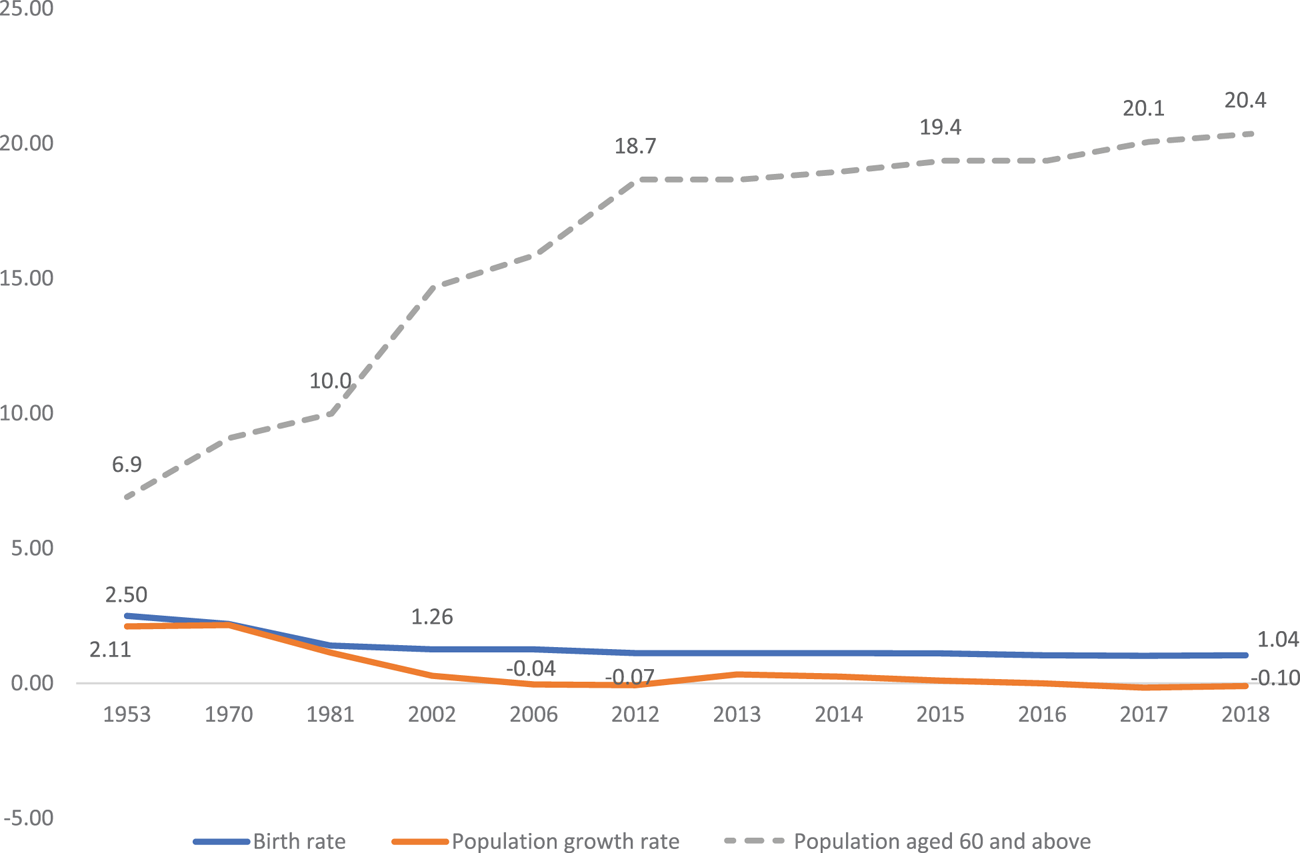

Cuba's population growth rate fell from 2.1 per cent in 1953 to −1.0 per cent in 2018 for two reasons: the lowest birth rate in the hemisphere (declining from 28.3 births per 1,000 people in 1953 to 10.4 in 2018) and consistently high net emigration rates. The total fertility rate (average number of children born per woman of reproductive age) was 1.65 in 2018, well below the 2.1 replacement rate, hence the population size started to decline in 2017.Footnote 59 Contributing to this phenomenon are high contraceptive-use rates (the contraceptive-use rate is estimated at 77 per cent); high reliance on induced abortion; relatively high female labour-force participation (even though at 37 per cent Cuba's rate is relatively low by international standards – in 2019 the global rate stood at 48 per cent and for Latin America at 52 per cent);Footnote 60 and austere living conditions (low average wages, scarcity of consumer goods and unavailability of adequate housing) that dissuade potential mothers from having children. Net migration rates have been consistently high, barring a couple of years, since the mid-1990s. In 2018, net emigration from Cuba amounted to 21,564 citizens, including a high proportion of women of reproductive age, further contributing to the low birth rate.Footnote 61 Demographic trends from 1953 to 2018 are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Ageing of the Cuban Population by Percentage, 1953–2018

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on ONEI, Anuario estadístico de Cuba (2018); Anuario demográfico de Cuba (2018).

Due to population ageing, the relative size of the aged 0–14 cohort decreased from 36.9 per cent in 1970 to 16.1 per cent in 2018 and is projected to decline further to 5.5 per cent by 2030; during the same interval, the old-age cohort (aged 60 or over) grew from 9.1 per cent to 20.1 per cent and is projected to reach 30.1 per cent by 2030 and 36.2 per cent by 2050. By the latter year, close to 1.4 million Cubans, or 15 per cent of the population, will be above age 80, the so-called ‘old-old’ category. The productive-age cohort (aged 15–59), which is crucial because it supports the other two, is decreasing: from 64.8 per cent in 2002, to 63.8 per cent in 2018 and projected to decline to 54.4 per cent by 2030. Thus, the ‘dependency ratio’ (the population younger than age 15 plus those aged 60 or over, divided by those of prime working age) increased from 53 per cent in 1990 to 56 per cent in 2018 and is expected to reach 84 per cent in 2050, a heavy and growing burden.Footnote 62

As we approach the 2030s, the 1960s baby-boom children, born at the start of the Revolution, are reaching retirement age, just as overall population and labour-force sizes contract.Footnote 63 Assuming current population projections hold, this cohort – along with 1.8 million other Cubans above age 65 – will have to depend on resources generated by four million economically active workers, whether directly or through the state.

Prevention and primary-care services were largely designed to cope with disease profiles effectively treated through preventive public health measures but with limited effectiveness regarding diseases afflicting the elderly. The shift from communicable diseases – including common infections, insect-borne diseases and illnesses associated with poor sanitation and unsanitary water – toward degenerative and end-of-life diseases will be particularly challenging, as the latter are significantly more difficult and costly to treat. Therefore, the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in the next 30 years will be critical. In these respects, Cuba faces similar challenges to other nations with ageing populations as health interventions designed to prevent/minimise chronic conditions will serve to not only improve living conditions for the elderly but also lower overall healthcare costs.

A national survey of the elderly conducted in 2017–18 revealed that 70 per cent complained about the inability to purchase basic necessities due to low incomes, while 80 per cent reported suffering from chronic diseases.Footnote 64 The former suggests the elderly are among the poorest-income groups in the population.Footnote 65 This is contrary to other Latin American countries with robust pension systems, where the elderly population is not among the lowest-income groups. In the latter, pension income is often supplemented by monetary transfers – including foreign remittances in some cases – provided by younger relatives, continued labour-market participation and co-residential arrangements with other family members.Footnote 66

The people most affected by medicine shortages are the elderly, who are highly dependent on prescription drugs to control hypertension, diabetes, prostate ailments and mental illnesses. They also confront shortages of incontinence underwear, often unavailable for months. Facing such scarcities, consumers wait in long queues or rush to pharmacies, often in distant locations, when news spreads that coveted supplies are temporarily available.

Ageing also demands elderly care. A recent comparison of adult care in the three most-aged Latin America countries (Chile, Cuba and Uruguay), based on multiple indicators, ranked Cuba behind the other two due to the scarce provision of adult-care services, the decline in social-security pensions, the rise in neglected-group territories (women, those living alone and/or not receiving external remittances and those living in rural areas) and the decrease in healthcare personnel. These problems ‘lead to a deepening of the adult-care crisis, aggravated by the incapacity of social policy to anticipate and plan for problems related to ageing, as well as the concomitant economic deterioration’, and a virtual lack of adult organisations to influence public policy.Footnote 67 A Cuban demographer reports that incapacitated adults demand the care of an average of 1.6 people. Providing adult care is a great challenge: homes for the elderly are insufficient to meet demand and the burden of elderly care mostly falls on unpaid women.Footnote 68

The Long-Term Financial Sustainability of the Healthcare System

The problems alluded to raise the question as to whether Cuba’s system of universal free access to healthcare is financially sustainable in the long run.Footnote 69 The issue came to the fore during the 1990s economic crisis and has again become a concern as the economy has deteriorated over the last decade.

As noted, from 1985 to 1989 Cuba was ahead of Latin America and many countries in Eastern Europe on health indicators, a situation that began to change during the 1990s economic crisis. Social expenditures adjusted for inflation declined, whereas healthcare investment in physical plant and equipment was halted; importation of food, medicines and their key inputs for domestic production dropped (leading to shortages of 300 medications, including antibiotics, anaesthetics and insulin); and a lack of insecticides resulted in an increase in mosquito-borne diseases. There was a significant increase in food shortage-induced malnutrition and related diseases (like epidemic optic neuropathy caused by vitamin B deficiency) and most communicable diseases (like acute diarrhoea, acute respiratory diseases, chickenpox, hepatitis, syphilis and tuberculosis). Gains in life expectancy likely slowed down between 1990 and 1996 as maternal mortality rose; on the other hand, infant mortality kept declining.Footnote 70

The economic recovery, particularly since the early 2000s, due to the beneficial relationship with Venezuela, contributed to an improvement of health indicators although some did not return to 1989 levels. Venezuela became Cuba's major trade partner, buyer of professional services, oil supplier and investor; this relationship peaked in 2012 when its total value was equivalent to 22 per cent of Cuba's GDP.Footnote 71 Cuba's economic relationship with both the Soviet Union and Venezuela entailed significant subsidies to prices of Cuban goods and services exports. Soviet prices of Cuban sugar and nickel imports were considerably higher than world-market prices, whereas the opposite was true for prices of Soviet oil exports.Footnote 72 Venezuelan salaries paid to Cuban medical professionals were about seven times higher than for Venezuela's own doctors.Footnote 73 Shifting trade to countries unwilling or unable to provide subsidies would be difficult.

As indicated, the severe economic crisis in Venezuela and the strengthened US embargo had a devastating impact on Cuba.Footnote 74 Cuban GDP growth dwindled from 12.1 per cent in 2006 (when Raúl Castro took over) to 0.5 per cent in 2019 (see Figure 3); the latter was the seventh-lowest percentage among the 33 countries in the region.Footnote 75 In July 2020, well after the Covid-19 pandemic was under way, the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) projected a negative growth rate of −8 per cent.Footnote 76

Figure 3. Percentage of Economic Growth (GDP) in Cuba, 2006–18, and Estimate for 2019

Source: Data for 2006–18 from ONEI, Anuarios estadísticos de Cuba (2006 to 2018); data for 2019 is a projection from ECLAC, Estudio económico de América Latina y el Caribe, 2019 (Santiago: ECLAC, 2019).

Declining Healthcare Expenditures

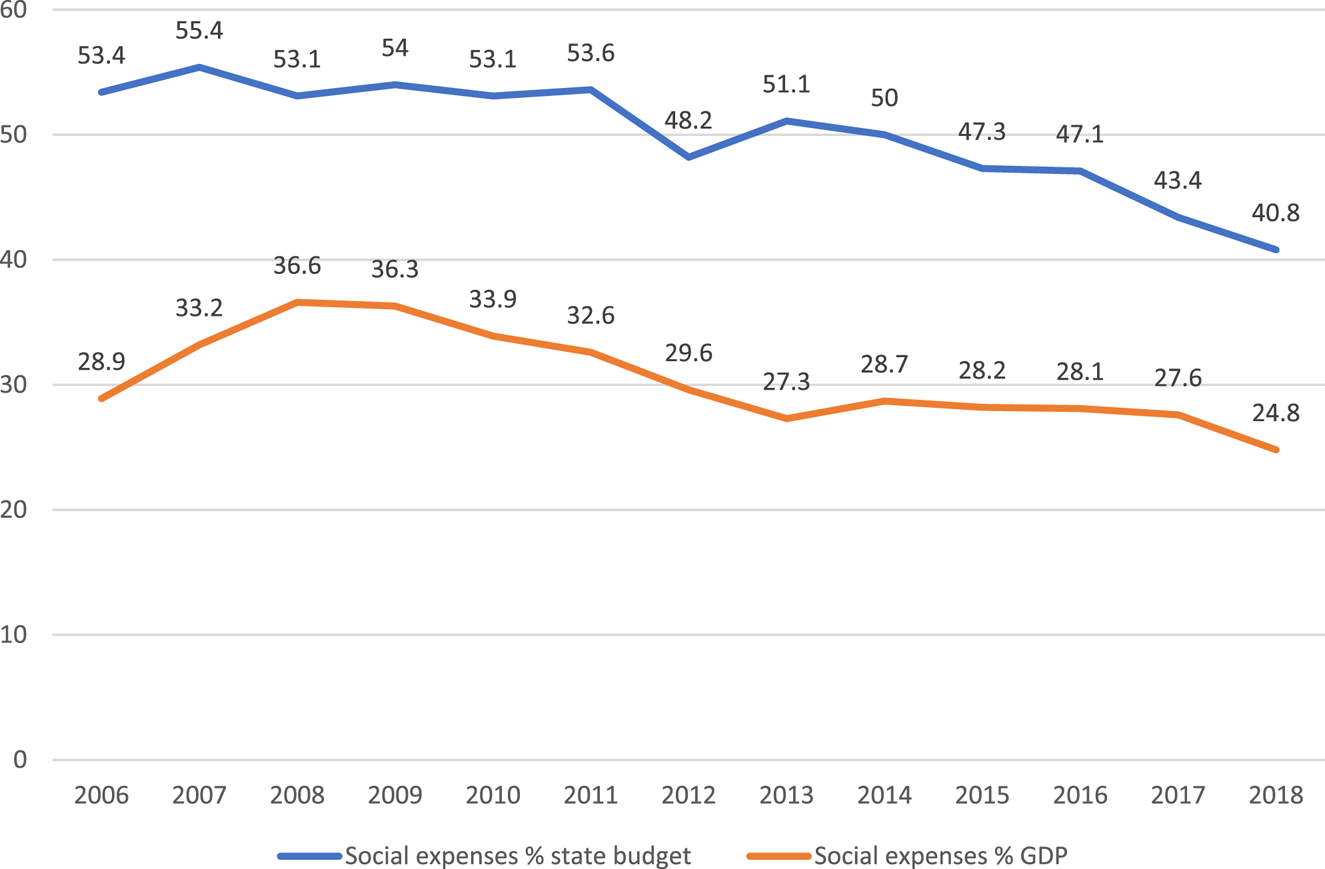

Ten years before the ongoing economic crisis, social expenditures (in health, education, pensions, housing and social assistance) – which had reached their zenith in 2007–8 when, as a percentage of the national budget current expenditures and GDP, they accounted for 55.4 per cent and 36.6 per cent respectively – began to be reduced. At that point, the government issued an alert about the heavy social costs incurred while reducing social expenditures to a financially sustainable level.Footnote 77 By 2018 the respective relative shares had declined to 40.8 per cent and 24.8 per cent (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Trends in Social Expenditures in Cuba, 2006–18

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on ONEI, Anuarios estadísticos de Cuba (2007 to 2017).

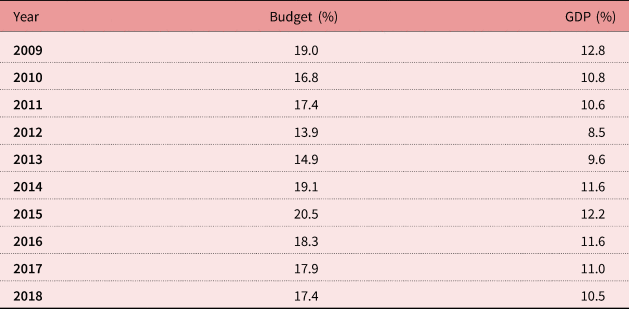

The estimation of current healthcare expenditures (in CUP at current prices) is marred by several problems:Footnote 78 (i) MINSAP statistical yearbooks provide healthcare expenditures alone – the 2018 yearbook deleted this series – but not the budget total current expenditures or the corresponding percentage for healthcare; (ii) in 2013, ONEI statistical yearbooks started merging health and social-assistance expenditures while providing separate series on the national budget total current expenditures and GDP; (iii) in the period when MINSAP's and ONEI's health expenditures alone were comparable, figures were completely different (ONEI's were considerably higher than MINSAP's, hence percentages based on the latter were substantially smaller than those based on the former). In view of the above, we decided to rely on ONEI's series because they provide comprehensive and consistent data on both expenditures and GDP for the entire 2007–18 period; social assistance does not distort the results because it is only 5 per cent of the combined total, the remaining 95 per cent being healthcare expenditures.Footnote 79 Table 3 shows the results: as a percentage of the state budget total current expenditures, the combined healthcare and social-assistance expenses reached 19 per cent in 2009, peaked at 20.5 per cent in 2015 and descended to 17.4 per cent in 2018. As a percentage of GDP, they peaked at 12.8 per cent in 2009 and later oscillated but decreased to 10.5 per cent in 2018. In addition, we calculated healthcare expenditures alone (based on MINSAP data) as a percentage of budget total current expenditures and GDP (based on ONEI data) for the 2015–17 period: relative to the budget total expenditures, the healthcare share decreased from 13.8 per cent to 11.7 per cent and, relative to GDP, it declined from 8.2 per cent to 7.2 per cent. All calculations, therefore, show a declining trend in healthcare expenditures.

Table 3. Health and Social-Assistance Expenditures as Percentage of Budget Current Expenditures and GDP in Cuba, 2009–18

Source: Authors’ estimates based on ONEI, Anuarios estadísticos de Cuba (2009 to 2018).

Management of the Covid-19 Pandemic

The onset of the Covid-19 crisis aggravated the already high trade deficit as exports decreased significantly. With little access to external credit, Cuba had to reduce imports and, at the end of 2019, halted payment of the foreign debt. Covid-19 compounded the healthcare challenge. The Cuban government did not react immediately to the pandemic; in fact, the island was touted as a safe tourist destination. Initial preventive measures were not implemented until March 2020, when 21 positive cases were confirmed, most imported by tourists. The centralised nature of the political-economic state and the existence of a unified national health system helped enforce strict preventive measures, albeit gradually. The pandemic taxed the health system, which was already under pressure due to widespread scarcities of soap, detergents, water and other sanitation inputs. Financial restrictions reduced the import of medicines, protective masks and ventilators; access to diagnostic tests increased due to a Chinese donation of test kits; and there is no data on operational intensive-care units (ICUs). Cuba promoted its nationally produced interferon drug as a treatment for the virus, despite the WHO's opinion that it is not an effective treatment.Footnote 80 MINSAP reported that homeopathy products help lift defences against the virus, while recognising that they do not prevent its consequences.Footnote 81

Queues to purchase scarce foods were frequent, often disregarding social-distancing precautions and thus facilitating contagion, although the use of masks was mandatory. In an effort to urge the population to stay at home and avoid overcrowding, authorities promised home delivery of rationed food. However, they were unable to fulfil their promise as the already sparse food supply was tightened even further by import cuts, which were partly caused by the collapse of tourism and the consequential foreign-revenue shortages. Furthermore, agriculture production decreased due to reductions in fertilisers, pesticides and fuel imports.

Because 20 per cent of the population is aged 60 or over, and 81 per cent suffer from at least one chronic condition (diabetes, hypertension or obstructive lung disease), the risk of contagion-related complications is considerable. Forty per cent of Cuban households contain an older adult and, moreover, Cuba also has a high percentage of older people living alone who, if infected, face difficulties accessing food, drugs and medical care (the government organised support teams to alleviate this problem). As elsewhere, nursing homes provide a rich environment for contagion and subsequent death, a problem exacerbated in Cuba because 68 per cent of those providing elderly care are themselves over 50 years of age and at higher risk of contracting Covid-19. While 28.5 per cent of confirmed Covid-19 cases were aged 69 or over as of late April 2020, they accounted for 85.7 per cent of all Covid-19-related deaths, a case fatality rate of 48.5 per cent.Footnote 82

Despite this adverse situation, Cuban authorities claim to have handled the onset of the pandemic quite well: on 24 June 2020 there was a total of 2,321 cases and 85 deaths, a rather benign outcome. While on 19 July 2020 no new cases were reported, 37 new ones were announced just a few days later, indicating a fluctuating pattern.Footnote 83 In addition to the universal healthcare system already mentioned, one observer attributed what the government reported as reasonable management of the pandemic to the highest physician-to-population ratio in the world, a well-structured primary healthcare system and a history of confronting emergency situations given Cuba's frequent exposure to hurricanes.Footnote 84 Conversely, the Latin American chapter of an international non-governmental organisation (NGO) funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation – as part of a regional evaluation of the pandemic – questioned Cuban official figures due to the government's consistent refusal to reveal to independent journalists ‘cases that were found positive or the situation facing those suspected of being infected’.Footnote 85 In early July, travellers originating from Cuba were prevented from entering the European Union; in Latin America only visitors from Uruguay were granted entry.Footnote 86 As the pandemic unfolded, the government was sending hundreds of doctors to 14 different countries, a decision partly dictated by the dire need to earn hard currency.Footnote 87

Could Cuba Be Facing a New Special Period?

Even before the onset of the pandemic, several Cuban economists and demographers had warned that the current economic situation could lead to another Special Period and its attendant social effects. One demographer noted ‘the possibility of a setback under specific circumstances, as it happened with several [demographic and health] indicators in the decade of the 1990s, in the midst of an acute economic crisis …’ Footnote 88 Nevertheless, there are important differences between the situation today compared with 1989: (i) more diversified trade partners; (ii) greater and more varied foreign investment; (iii) much higher foreign-exchange revenue from professional exports, foreign remittances and tourism (the first-, second- and third-highest sources of hard currency, respectively); (iv) less dependency on imported fuels; (v) an insignificant private sector in 1989 that in 2019 accounted for close to 26 per cent of the labour force; and (vi) less overall economic dependency on a foreign nation (28 per cent of GDP with the Soviet Union in 1989, vis-à-vis 22 per cent at the peak with Venezuela in 2013, down to 8 per cent in 2017). And yet, many of these favourable circumstances have eroded due to Venezuela's worsening crisis, Trump's increasing punitive actions against Cuba, and the 2020 pandemic.

Government Policies and Alternative Options

Finding solutions to the problems confronting the Cuban healthcare system is difficult and, as shown, will get progressively worse, thus requiring rapid action. The potential threat to the long-term financial sustainability of the universal healthcare system could be reduced by policies from both the revenue and the expenditure sides. Regarding the former, a guaranteed share of hard-currency earnings from the provision of professional medical services abroad could be redirected to improve the health infrastructure, purchase medications and raise the salaries of healthcare personnel. In addition, in view of the increasing income inequality and the regressive nature of taxes in Cuba,Footnote 89 it would be appropriate to consider co-payments from higher-income patients for more complex and costly procedures. The provision of cheap medical services in Cuba could be expanded, particularly by enticing people from developing countries (‘medical tourism’) and by promoting long-term residential retirement tourism cum medical services among the elderly of middle-income countries whose healthcare expenses are covered by their social-security provisions, regardless of where services are received. An additional revenue stream may materialise by sending Cuban mid-level technical personnel to provide long-term care services in rich countries.Footnote 90

Another long-term option would entail enticing elderly US citizens, including those of Cuban descent, to retire in Cuba and rely on medical services provided by the Cuban healthcare system. This option, however, is not likely in the short term given the continued bilateral animosity between the two countries and the serious deterioration of Cuba's healthcare system. But even in the long run this alternative is unlikely to generate much revenue since federal regulations proscribe Medicare, the US government healthcare programme for the elderly, to pay for services accessed beyond the confines of the United States.Footnote 91

Finally, the Cuban health and education authorities should carefully assess the desirability of continuing to pursue their medical education strategy for two reasons: the exports of health professionals are declining (due to the economic crisis in Venezuela and changing governments in Latin America); and African countries are no longer buying, or are reducing demand for, such services (other than those associated with temporary global shortage of medical personnel due to the Covid-19 pandemic). The Cuban strategy of continued promotion of medical graduates (at the expense of graduates in disciplines needed for economic development) to increase foreign exchange through medical missions could be questioned in view of economic difficulties in Venezuela, as well as the return of physicians from Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador and some African countries.Footnote 92 A Cuban economist has noted that such an export strategy carries high risks, not only in terms of the potential vulnerability of political and economic developments in receiving countries, but also because the strategy is circumscribed by modest multiplier effects: health personnel abroad represent only 1 per cent of the Cuban labour force, but generate 44 per cent of total export value.Footnote 93

There might be a future in which Cuba will have to accommodate an excess of underutilised physician stock, as well as considerable economic and social dislocations associated with potential medical-export fluctuations. Physician surpluses, even if temporary, would benefit the elderly but be disruptive to the national economy. On the expenditure side and to cope with ageing, scarce available resources should be assigned more rationally by reducing facilities, personnel and funds allocated to younger-age cohorts (mothers and their children, for example), while assigning growing shares to the elderly. It would be desirable, for instance, to assign greater emphasis to inexpensive preventive measures capable of minimising the need for more expensive curative care. Doing so would require the return of many family doctors abroad – and, to avoid their potential underutilisation, retraining in skills attuned to elderly needs – together with sufficient economic growth to acquire foreign medical inputs essential for quality care. Such economic growth might be facilitated if the relatively wealthy émigré community were to be provided with an inviting domestic-policy environment to encourage their investments in Cuba.

Options to demographically address the challenge of a growing percentage of elderly people in a contracting population are few and unlikely to yield meaningful solutions. The director of the Cuban Centre for Demographic Studies at the University of Havana acknowledges that population ageing is irreversible (it could be slowed down through immigration, but migrants are unlikely to want to settle in Cuba given its current economic situation) while other long-term demographic trends (e.g. low fertility) could hardly be reversed in the short term. Some selected policies could be devised to alleviate the current demographic predicament. The most potentially consequential, often voiced before – and unlikely to come to fruition unless the national economy undergoes a remarkable turnaround – is bringing to an end the long-standing permanent emigration trend by encouraging circular migration. Were this to happen, Cubans would continue emigrating to and working in other countries, but routinely return to their homeland to be with family and friends and spend foreign earnings there.Footnote 94

A government commission was established in 2014 to consider and propose policy options to address the challenges due to the ageing and declining population. One approved policy allows a mother returning to work following her maternity leave, but before her child is one year old, to retain her maternity-leave allowance together with her regular salary for the rest of the year.Footnote 95 In mid-2019, 76 additional measures were enacted to increase the birth rate, out of which 62 have been implemented and monitored on a quarterly basis. Pro-fertility measures include improving access to day-care centres for children of working women (demand vastly exceeds supply as only 18 per cent of potential users are served); and assigning 50 million CUP (US$2 million) to build housing for mothers with three or more children under 12 years of age (as lack of adequate housing is a major reason women avoid having children).Footnote 96 Another programme, established for couples wanting children but unable to conceive, now in its fourth year of implementation, is the ‘Service Network for Infecund Couples’, available in all municipalities (and counting) with technology centres in four hospitals.

Despite implementation of these pro-fertility measures, the number of births declined by 5.7 per cent in 2018–19 (from 116,333 to 109,707), just as the total fertility rate fell from 1.68 to 1.65 from 2014 to 2018.Footnote 97 Such modest outcomes are consistent with those achieved in comparable programmes in other low-fertility countries. When achievements result, they usually entail high price tags. In Cuba's case, the situation is rather problematic given the country's serious economic difficulties.

Our analysis shows that measures to cope with both healthcare and ageing challenges will not produce fast and lasting results unless accompanied by rapid and sustained economic growth capable of generating the resources needed to improve social services, including healthcare. Cuban academic economists agree that the solution lies in accelerating and deepening the structural reforms left incomplete by Raúl Castro. Suggested measures include an expansion of the non-state sector (particularly self-employment) to generate productive jobs, as well as an agrarian reform programme along the lines of those successfully implemented in China and Vietnam to increase food production and reduce imports. Last May, Granma, the Communist Party's newspaper, rejected such proposals as neoliberal. Shortly thereafter – during an extraordinary meeting of the Council of Ministers – an urgent call was made to ‘change everything that should be changed’, within the confines of central planning and a tightly regulated market. Hopefully, the required steps will be implemented in the near future.Footnote 98

Conclusion

This article has shown that since the economic crisis of the 1990s several key health indicators in Cuba have continued to improve, while others have deteriorated or had mixed results. The situation has been further aggravated since 2007 as the rising cost of universal free access to social services and poor economic growth have prompted a substantial cut in social expenditures such as healthcare. This led to the closure of all rural hospitals as well as rural and urban posts (primary-care stations), whereas the number of general hospitals and healthcare personnel – other than physicians – was reduced. As exports of physicians and other healthcare personnel became the country's major source of hard-currency revenue, the Cuban population's access to healthcare diminished. The strategy of continued physician training could be questioned because the future demand for medical missions is uncertain and only a small portion of the export revenue generates benefits for the healthcare sector. The small share of national investments assigned to improve the deteriorated healthcare infrastructure further clouds the picture. Medicine shortages are widespread while agricultural production has declined as basic input imports have been curtailed in favour of servicing the mounting foreign debt in a contracting economy, further aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic that halted the arrival of foreign tourists. The fiscal challenge will intensify as a growing elderly population requires more expensive treatments associated with degenerative and terminal illnesses. The conclusion is that Cuba's current healthcare system is financially unsustainable unless substantial structural economic reforms are implemented at the earliest opportunity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are responsible for this article but acknowledge help provided by Jorge Pérez-López, Pedro Monreal and Mayra Espina, as well as suggestions by JLAS editors and referees.