Introduction

Despite previous attempts, the Early Neolithic of Portugal was poorly understood until the latter part of the twentieth century. It is only when Guilaine and Ferreira (Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970) re-analysed pottery assemblages kept in museums across the country and compared them with parallels elsewhere in Iberia and southern France that they were able to distinguish between an earlier Cardial phase and a more recent stage, named ‘Furninha horizon’ after an important burial cave excavated in 1880. Essentially, most Portuguese prehistorians still use this scheme today. Though some have argued in favour of pre-Cardial phases, either of African or Andalusian origin (e.g. Silva & Soares, Reference Silva and Soares1981) or represented by impressa-type ceramics of Italic origin (e.g. Guilaine, Reference Guilaine2018), these hypotheses are still lacking sound empirical support (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Pardo-Gordó, Gómez-Bach, Molist and Bernabeu2020). It should, however, be noted that these hypotheses are still sometimes taken up in discussions of new finds. This is the case in a recently-published ovoid vase, with a flat base and impressed decoration, retrieved from so-called ‘hearth 8’ at the open-air site of Vale Pincel (coastal Alentejo), which was dated to c. 5650 cal BC. As this predates the oldest Cardial in Portuguese territory and is not a Cardial vessel, the author claims that this ‘ceramic decoration is part of the pre-Cardial impressed world’ (Soares, Reference Soares, C.T. and J.2020: 311–2 and fig. 4).

Complete vessels, some with Cardial decoration, discovered without any known archaeological context, featured in this model. Indeed, two specimens were complete (though fragmented) vessels, apparently found isolated at imprecise locations in central Portugal—the so-called Cartaxo and Santarém vessels. Since they were complete, it was possible to describe their shape and thus make formal and stylistic comparisons. Over the last fifty years a few more vessels have been found in similar circumstances, not only in the same region but also in the southern half of Portugal (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011; Gonçalves & Sousa, Reference Gonçalves and Sousa2017). The vessel recently found at the Galician cave of Eirós can now be added to this corpus (Fábregas et al., Reference Fábregas, Carvalho, Lombera, Cubas, Lucquin, Craig and Rodríguez2019).

The limited information available on the provenance of isolated ceramic vessels is also evident in most of the known Early Neolithic funerary contexts in Portugal. Large assemblages from burial caves reflect long-lasting habits of cave use throughout prehistory. In some cases abundant assemblages of human remains were also found and ascribed to later prehistoric periods, particularly the Neolithic and Chalcolithic, but without a specific chronological attribution within this broad timespan. The first case of such a context being clearly defined and radiocarbon-dated to the Early Neolithic was Caldeirão Cave (Zilhão, Reference Zilhão1992, Reference Zilhão1993), where clear, direct associations between human remains and grave goods were recorded and analysed. Despite later finds and the revision of older excavations (e.g. Oosterbeek, Reference Oosterbeek1993; Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Carreira and Ferreira1996; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2008; Zilhão, Reference Zilhão2009), this is still the best documented Early Neolithic collective funerary site in western Iberia.

Given these circumstances, the discovery of burial pits with single inhumations associated with complete vessels datable to the Early Neolithic in recent salvage excavations in the old centre of Lisbon, at Armazéns Sommer and at Palácio Ludovice, was a welcome surprise. These two discoveries represent not only new, unexpected evidence of funerary practices but also lead to a hypothesis concerning the interpretation of the isolated vessels mentioned above. Here, we shall first present the Early Neolithic burials at Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice, excavated by the private archaeology company Neoépica.

The Excavated Burial Sites

Armazéns Sommer

Armazéns Sommer is the name by which former storehouses (armazéns in Portuguese) are known in the eastern riverside area of downtown Lisbon, on an ancient bank of the Tagus estuary (Figure 1). Before the conversion of the warehouse into a hotel, extensive salvage excavations between 2004 and 2016 uncovered a long and continuous occupation sequence; its older phase, represented by the Early Neolithic burial presented here, was addressed in an extensive and detailed article (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Rebelo, Neto and Ribeiro2018).

Figure 1. Top: Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice in the city of Lisbon, with the location of the important coeval settlement of Encosta de Sant́Ana. Bottom: the sites in Lisbon's urban fabric.

Base map: open data from the Lisbon City Hall and GoogleEarth.

The burial in question is an ellipsoidal burial pit, with a flat base, c. 80 cm wide, cut into orange, sterile sandy sediments. The feature was identified because the more compact and darker, brownish sediments that filled it contrasted with the surrounding soil, and a few flint artefacts and mammal bones were present. Some stones and pottery sherds were visible around the pit's northern edge (Figure 2). The sherds belonged to a single, coarse and dark vessel. After refitting, it turned out to be a two-handled pot with a narrow neck and curved, paraboloid base, decorated in boquique technique (grooved lines obtained by stabbing and dragging with a pointed tool) arranged in garland-like motifs (Figure 3). The vessel was deposited at the bottom of the pit, on its northern side. Due to the levelling of the surface by later occupation, the upper part of the pit and its fill were destroyed, leaving only the pot and the human skeleton in a c. 10 cm-thick layer at the base of the pit.

Figure 2. Armazéns Sommer. View of the pit's base fill with the skeleton in lateral decubitus with flexed arms and legs, flanked by is accompanying vessel (red circle).

Figure 3. Armazéns Sommer. Closed, necked vessel with boquique decoration. Drawing by permission of Filipe Martins.

The pit contained a single inhumation, probably a male over 17 years old at the time of death. This individual was buried in anatomical connection, lying on its right side and oriented NW–SE, with the head to the NW and the arms and legs flexed—i.e. in lateral decubitus (foetal) position. Overall, the post-cranial skeleton was almost complete, despite the quite poor condition of the bones. The skull had been removed by later levelling of the surface. With the exception of the vessel, no other grave goods were associated with this individual.

Palácio Ludovice

Palácio Ludovice is located in Lisbon's Bairro Alto, near the top of the Colina de São Roque, a hill overlooking the right bank of the Esteiro da Baixa, a former branch of the Tagus palaeo-estuary that penetrated inland, in an area where important Early Neolithic deposits at Encosta de Sant́Ana were encountered further east (Angelucci et al., Reference Angelucci, Soares, Almeida, Brito and Leitão2007; Leitão et al., Reference Leitão, Cardoso and Martins2021) and where Lisbon would expand in Roman times (Figure 1). The 2018–2019 excavations inside the Palácio revealed several Early Neolithic domestic structures (hearths, stone and clay structures) in an archaeological level with abundant assemblages (pottery, knapped and polished stone tools), attesting to an important, possibly permanent settlement that extends under other buildings and streets in this area. A pit burial, the only one identified at the site so far (Simões et al., Reference Simões, Rebelo, Neto and Cardoso2020), was found in Sector C10, immediately to the east of the settlement (Figure 4). This suggests that both funerary and settlement structures existed side by side.

Figure 4. Palácio Ludovice. Excavation of the Neolithic pit burial. Top: the fragmented vessel in situ; centre: brownish-black fill of the grave, on which the vessel was placed; bottom: inhumation with flexed arms and legs. Photographs by permission of Neoépica Ltd.

The pit, c. 1 m in diameter, was cut into an archaeologically sterile, compact, homogeneous, orange clayey layer. Like the individual at Armazéns Sommer, the Palácio Ludovice person was buried in anatomical connection, lying in lateral decubitus (foetal) position on its right side, but oriented W-E, with the head to the W. The study of the skeletal remains, despite the poorly preserved bones, suggests an adult male (R. Granja, pers. comm.).

Large sherds belonging to a single, substantial pottery vessel were found immediately above the inhumation. The vertical spread of the ceramic fragments showed that the pot's rim and neck were located in the upper part of the pit, while the pot's body and bottom were found in its lower part, strongly suggesting that the vessel was originally placed in an upright position above the grave and probably semi-buried to avoid collapse. This may in turn suggest that it was used to mark the burial pit.

The vessel has a narrow, cylindrical neck and curved, paraboloid body and base (Figure 5). Between the neck and the body there is a marked carination decorated by a row of double impressions. Three handles with a knob on top connect the upper and the lower part of the vessel. The upper part of the vessel's body has several incised, isolated and aligned metopes. These cross-hatched incisions also occur over the handles and can be found scattered over the vessel's body; its lower part is not decorated.

Figure 5. Palácio Ludovice. Closed, necked vessel decorated with incisions. Drawing by permission of Filipe Martins.

Discussion

The occurrence of isolated vessels: parallels, chronology, and meanings

The two burials described above are the only cases of burial pits datable to the Early Neolithic so far recorded in systematically excavated contexts, not only in the present-day city of Lisbon, but also on the entire western façade of Iberia. They are therefore key sites for the study of Early Neolithic funerary practices in this vast region. In both cases the bodies were inhumed lying on their right sides with flexed legs and arms (i.e. in foetal position) and with a single pot as grave good. Similarities also exist in the vessels’ shape (both are necked vessels), but differences can be observed in the mode of deposition (inside the pit at Armazéns Sommer, on top of the pit at Palácio Ludovice), the size of the pots, and their decorative patterns and techniques.

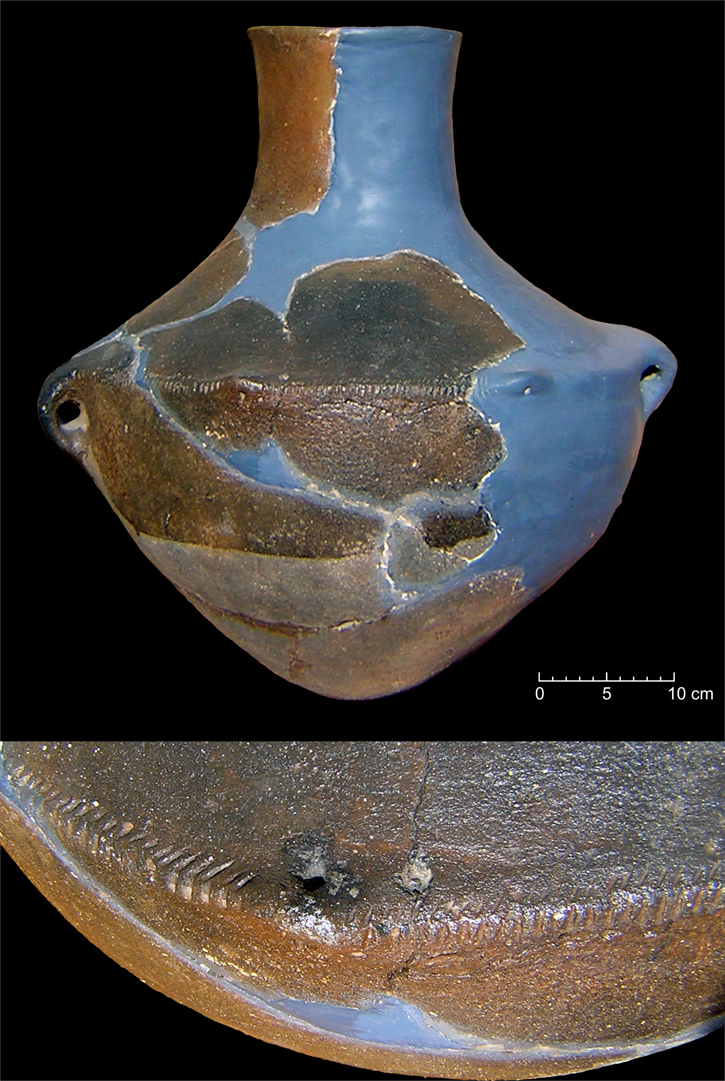

The Palácio Ludovice vessel shows strong similarities with other exemplars known in Portugal that have no archaeological context and have been considered isolated finds (Guilaine & Ferreira, Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011; Gonçalves & Sousa, Reference Gonçalves and Sousa2017). An instance of a similar vessel being found in (apparent) association with an occupation context is known from the Early Neolithic settlement of Alto da Toupeira-Pedreira das Salemas (Castro & Ferreira, Reference Castro and Ferreira1959; Ferreira & Castro, Reference Ferreira and Castro1967), located immediately north of Lisbon. The site was severely damaged by quarrying (Figure 6). A later re-evaluation indicated that this was a settlement with at least one funerary deposition (human remains associated with a pottery vessel) inserted in the more or less deep irregularities of the limestone bedrock (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Carreira and Ferreira1996). Thus, it is possible that the Pedreira de Salemas vessel was marking the location of one such burial, as at Palácio Ludovice. Similar cases of more or less complete vessels found in apparent isolation but inside or in the immediate vicinity of settlements are those of Praia de São Julião, Castelo dos Mouros, and Cabranosa, described below (Figure 7). It should be noted that in most, if not all, cases other than the three sites mentioned, no context whatsoever could be established. Indeed, at some locations—e.g. Ponte da Azambuja (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Neves and Cardoso2010) or Barranco das Mós (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011)—excavations were conducted but failed to recognize Neolithic levels. It is therefore possible, in our view, that putative burial pits (if confirmed by future research) may have been located in burial grounds away from settlements.

Figure 6. Vessel from Alto da Toupeira/Pedreira das Salemas (Loures, Lisbon) and detail of the decorative motif (impressions over the vessel's carination). Photograph by João Luís Cardoso by permission of the Geological Museum (Lisbon).

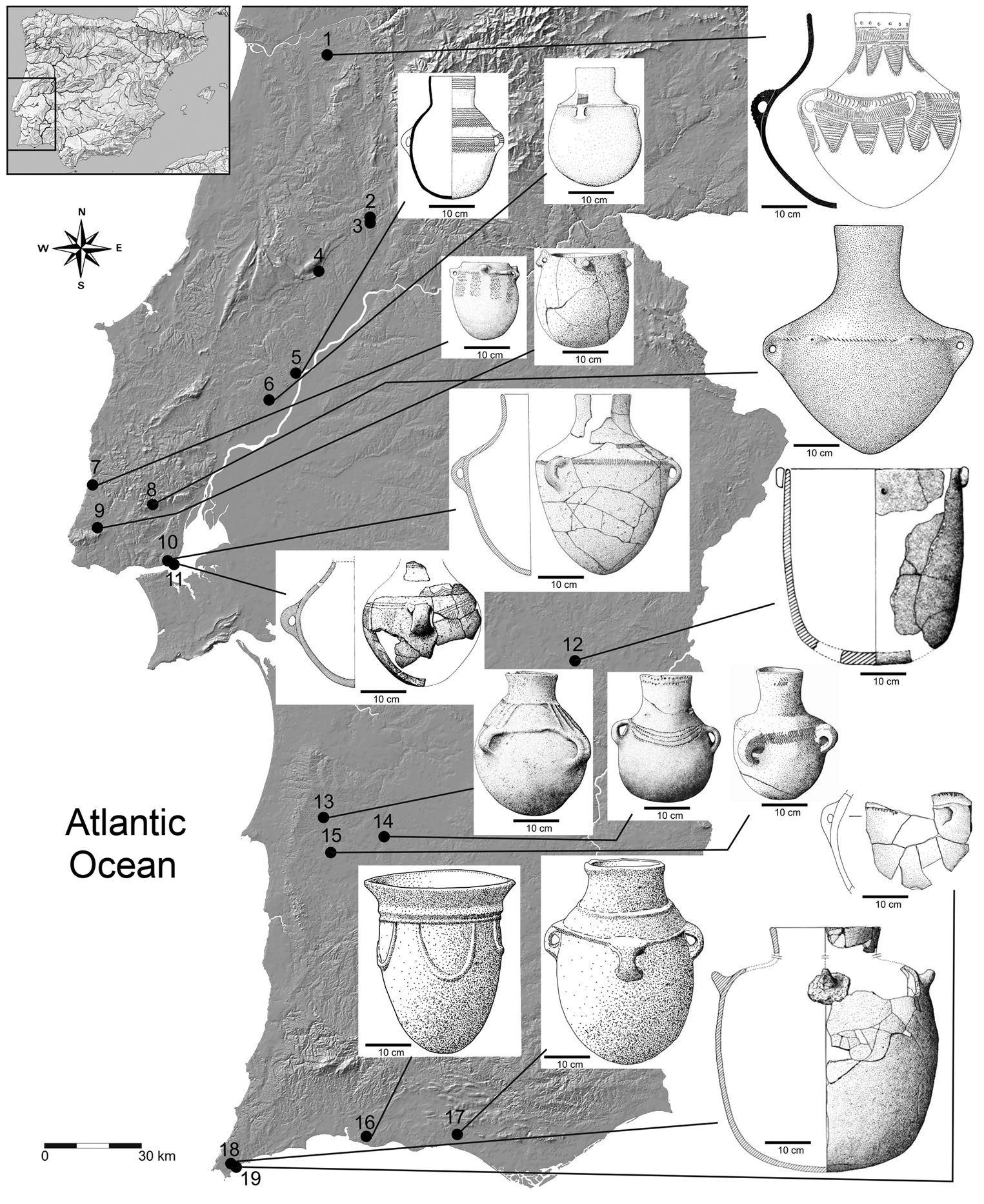

Figure 7. Location of Early Neolithic cave cemeteries and isolated Early Neolithic vessels in Portugal. 1) Casével; 2) Cave of Nossa Senhora das Lapas; 3) Caldeirão Cave; 4) Algar do Picoto; 5) Santarém; 6) Cartaxo; 7) São Julião; 8) Alto da Toupeira-Pedreira das Salemas; 9) Castelo dos Mouros; 10) Palácio Ludovice; 11) Armazéns Sommer; 12) Ponte da Azambuja 3; 13) Herdade dos Aduares; 14) Herdade do Monte da Vinha; 15) Herdade do Pego da Mangra; 16) Sobreiro; 17) Retorta; 18) Cabranosa; 19) Barranco das Mós.

The potttery drawings on the figure are based on: 1) Pessoa, Reference Pessoa1983: fig. 3; 5) Guilaine & Ferreira, Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970: fig. 3; 6) Guilaine & Ferreira, Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970: fig. 4; 7) Carreira, Reference Carreira1994: fig. 4, no. 1; 8) Spindler, Reference Spindler1981: fig. 20; 9) drawing by B. Ferreira on photograph by M. Tissot after Sousa & Carvalho, Reference Sousa and Carvalho2015: fig. 3; 10) drawing by F. Martins; 11) drawing by F. Martins; 12) Martins et al., Reference Martins, Neves and Cardoso2010: fig. 6; 13) Cardoso, Reference Cardoso2002: 169; drawing by C. Lemos; 14) GAMNA, 2005, p. 1, drawing by H. Figueiredo; 15) drawing by B. Ferreira on photograph after Santos, Reference Santos1985: 36; 16) drawing by F. Martins on photograph after Gomes, Reference Gomes2007: fig. 13; 17) drawing by B. Ferreira on photograph by J. P. Ruas; 18) Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Carvalho and Norton1998: fig. 7; 19) Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011: fig. 11.5, no. 6.

The available absolute dates for Armazéns Sommer and Pedreira de Salemas (Table 1) indicate the beginning of the fifth millennium bc, thus suggesting that this must be the time for the appearance of burial pits for single inhumations in this area and probably the whole of present-day Portugal. At Palácio Ludovice, the human remains had insufficient collagen for AMS dating, but at Armazéms Sommer it was possible to obtain a radiocarbon determination of around 4900 cal bc. At Pedreira de Salemas, the median is 4950 cal bc. These results place the two sites at the beginning of the so-called Evolved Early Neolithic, which is consistent with the stylistic features of the pottery vessels. This conclusion is particularly important in the case of the vessel from Armazéns Sommer, which is decorated in boquique technique.

Table 1. Radiocarbon determinations of Early Neolithic burial sites of the Lisbon area. All determinations on human bone samples; calibrations after IntCal13 curve (Reimer et al., Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell and Bronk Ramsey2013; mixed with Marine13 in the case of sample Wk-45573).

This decoration technique has been attributed to the earliest stages of neolithization in the eastern and inland sectors of the Iberian Peninsula (Alday et al., Reference Alday, Carvalho, Cerrillo, González, Juez, Moral and Ortega2009), correlated, in the east, with the impressa style (impressed ware) originating in southern Italy (Bernabeu et al., Reference Bernabeu, Molina, Esquembre, Ramón and Boronat2009). The same chronological framework—the second half of the sixth millennium bc—has been also proposed for the Portuguese productions (Alday & Moral, Reference Alday, Moral, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011). However, a detailed chronostratigraphic assessment of its appearance and development in western Iberia concludes that ‘[…] the appearance of the boquique technique [occurs] practically simultaneously, in the Beira Alta, Estremadura and Alentejo [provinces of Portugal] in the course of the first quarter of the fifth millennium bc’ (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2019: 13; own translation). Our results further endorse this conclusion.

The individual burials: practices and integration in the Early Neolithic

As noted, the Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice burials share some formal traits: inhumation in flexed (foetal) position inside a burial pit, associated with the deposition of a necked pot, simply decorated but with different techniques and motifs. No other grave goods were recovered during excavation, not even personal ornaments, even though these are common in other Early Neolithic cemeteries. While the poor preservation of the bones of the two individuals made their osteological study problematic, it is highly likely that both individuals were adult males.

So far, correlation between human remains and grave goods is possible (with different degrees of reliability) at only three Early Neolithic cemeteries. All are burial caves: from north to south, Caldeirão (Zilhão, Reference Zilhão1992), Nossa Senhora das Lapas (Oosterbeek, Reference Oosterbeek1993), and Picoto (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2008) (Figure 7).

At Picoto, a few incised pottery sherds were recovered in a dejection cone. The sherds are datable to the Evolved Early Neolithic and could be associated—although direct associations between individuals and grave goods could not be established—with two individuals (a male and a female), both radiocarbon-dated to c. 4900 cal bc. Nossa Senhora das Lapas yielded a single burial in its layer B, which was dated to c. 5050 cal bc. This individual, a child of undetermined sex inhumed next to an alignment of small stones, was accompanied by a rich assemblage of grave goods comprising ten flint blades, one retouched quartzite pebble, an unpublished number of plain and incised potsherds, and green mineral beads and shells of Glycymeris (bittersweet clam). Finally, the earliest Early Neolithic horizon of Caldeirão (c. 5400–5100 cal bc) varies even more in the association between grave goods and deposited (not buried) individuals: one male (R12-13) was associated with three microliths and one Glycymeris bead; another male (R11) with 120 beads made from the water snail Theodoxus, Hinia and Glycymeris shells; and a female (O11-12) with a Cardial pot. Although this may suggest that pots are not found with males, it must be borne in mind that Caldeirão is earlier in date than our burial pits.

It may be suggested that two stages are discernible within the Early Neolithic funerary evidence in Portugal: individuals buried in caves during an early, Cardial, phase (so far represented by the Caldeirão Cave alone) apparently had no material and ritual evidence for status differentiation; and burial pits for individual inhumation appeared at a later, evolved stage (represented by Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice). Despite sharing the same space and lacking any delimiting structures, the individuals deposited at Caldeirão occupy different sectors of the cave; the funerary space is not contiguous, with areas devoid of human remains and grave goods. While different, both burial caves and burial pits attest to the same practice of individual inhumation or deposition, which can be considered typical of the period. The emergence of collective cemeteries, both in cave sites and megaliths, only occurs in Portugal at the beginning of the fourth millennium bc, coinciding with the onset of megalithism (see Carvalho & Cardoso, Reference Carvalho and Cardoso2015 for a recent synthesis).

Distribution, typology, and hypothetical meanings

Twelve vessels found more or less intact but devoid of any known archaeological context have been recorded so far in Portugal. A few more intact vessels have been published (such as the vessel found in a settlement context at Alto da Toupeira-Pedreira de Salemas mentioned above) but these must not be confused with intact vessels found isolated or where no archaeological context could be established. Initial inventories compiled by Martins et al. (Reference Martins, Neves and Cardoso2010) and Carvalho (Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011) were recently reviewed and updated by Gonçalves and Sousa (Reference Gonçalves and Sousa2017). The finds can now be tentatively integrated in their supposed original contexts thanks to the evidence obtained at Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice.

The currently available list of isolated Early Neolithic vessels is presented here, site by site and from north to south (Figure 7 and Table 2):

Table 2. Typological synthesis of vessels. For descriptions and references, see text; for location, see Figure 7.

Casével (Condeixa-a-Nova): the vessel found there buried at a depth of around 0.6m is, according to Pessoa (Reference Pessoa1983), a ‘bottle’-type vessel with a conical bottom and three decorated handles. A composite decoration (corded, incised, and impressed) is arranged in two bands formed by punctures and incisions, under which there are successive triangles filled with dragged punctures.

Santarém: of uncertain origin, but apparently from the outskirts of this city, this vessel has a bag-shaped body with a prominent cylindrical neck and two handles. The decoration, which is exclusively Cardial, is arranged in three bands parallel to the rim (Guilaine & Ferreira, Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970).

Cartaxo: Guilaine and Ferreira (Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970) noted this vessel's similarities with the Santarém exemplar, both in terms of its circumstances of discovery (in the unknown neighbourhood of the village) and of its overall morphology. The main difference lies in the decoration, which in this case consists of the application of a plain cord joining the upper parts of the three handles and reticulated incisions.

Praia de São Julião (Mafra): this bag-shaped vessel is decorated with vertical bands of spine-like incisions, typical of the local Evolved Early Neolithic (fifth millennium bc), and has thick handles (Carreira, Reference Carreira1994: fig. 4, no. 1). It was found intact in sand dunes, apparently without archaeological context, although the remains of a Neolithic settlement have been identified nearby (Simões, Reference Simões1999). It is thus uncertain whether this is truly an isolated find or a piece removed from a larger context.

Castelo dos Mouros (Sintra): this vessel was found in a medieval cemetery at the Castelo dos Mouros (=Moorish castle) on the summit of the Sintra mountain range. This plain, bag-shaped vessel with knobs and bifid handles is typical of the fifth millennium bc. Given its find spot and completeness, it seems to have been intentionally buried, but, like the vessel from Praia de São, it is not clear whether it belonged to a larger context or not. Indeed, ‘since the vessel was found in an area with abundant Neolithic remains, although included in slope deposits, and therefore decontextualized, this prevents its immediate integration in the category of isolated finds …’ (Sousa & Carvalho, Reference Sousa and Carvalho2015: 282; own translation).

Ponte de Azambuja 3 (Portel): this large vessel, discovered in 2007 on the banks of a stream at a depth of about 2.5 m, has straight walls and a slightly flattened base, with two knobs and four perforations near the rim. The records from the excavation of the site indicate that this piece, deliberately buried, is devoid of any archaeological context (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Neves and Cardoso2010).

Monte da Vinha (Santiago do Cacém): this vessel, which is barely published (GAMNA, 2005; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011), is bag-shaped, with a high neck, below which there are three vertical handles. The impressed decoration is arranged in two bands, one immediately below the rim, and another, in a garland, joining the handles.

Herdade dos Aduares (Santiago do Cacém): of unknown provenance, donated to the National Museum of Archaeology in Lisbon in 1905 by Augusto Teixeira de Aragão, this necked oval vessel features corded decorations and four handles. It was published by Cardoso (Reference Cardoso2002: 169), who describes it as a vessel ‘with a decoration of plain cords in relief in the body and neck, narrow’ (own translation).

Herdade do Pego da Mangra (Santiago do Cacém): this mostly plain, necked vessel has an oval body and four handles in the body's upper part connected by a band of impressions. The context of this seemingly isolated find is unknown; the vessel is currently kept at the village's municipal museum. It was only published preliminarily by Santos (Reference Santos1985: 36 and fig. 36).

Cabranosa (Vila do Bispo): like the Praia de São Julião vessel, this find comes from an isolated position in sand dunes outside a settlement. It is likely that it belonged to the settlement's Cardial occupation, radiocarbon-dated to the mid-sixth millennium bc (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Carvalho and Norton1998: fig. 7). Devoid of decoration, this large bag-shaped pot has a short neck and four handles around it. It is interpreted as a storage vessel.

Barranco das Mós (Vila do Bispo): sherds from a vessel found on the banks of the watercourse bearing this name, in the same area as the find from Cabranosa, led to the excavation of the find spot, which indicated that the vessel was originally more than 2 m below ground surface and without associated archaeological context (Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Bernabeu, Rojo and Molina2011). The sherds belong to a large, closed, bag-shaped vessel, and the decoration consists of the application of a segmented cord that joins the handles. The upper part of the vessel (necked? open?) could not be reconstructed as the rim was missing.

Pinheiro/Sobreiro (Lagoa): in his discussion of the chronology of the menhirs of western Algarve, Gomes (Reference Gomes2007: fig. 13) mentions a vessel, apparently found isolated, attributed to the Early Neolithic. Given the similarities between its decoration and that of the menhirs, the pot was assigned to the same period as the menhirs. The published illustration shows a bag-like pot with a wide rim and decorated with several plain cords.

Retorta (Albufeira): Gomes et al. (Reference Gomes, Paulo and Ferreira2003: 16–17) refer to finding a vessel in a late Roman cemetery. Although not illustrated, the pot is described as ‘… ovoid or “bag”-shaped, with constricted neck and rim, provided with four small handles with transversal perforation, decorated by relief cords’, a type that the authors attribute to the Early Neolithic period. The vessel is kept at the Albufeira Museum of Archaeology. More recently, it has been re-analysed by Gonçalves and Sousa (Reference Gonçalves and Sousa2017).

As can be seen from their geographical distribution (Figure 7), these vessels concentrate mainly in the central and southern regions of Portugal, where the oldest Neolithic sites of western Iberia are located. It therefore seems that a very close relationship existed between the earliest farming groups in the area and the deposition or burying of vessels. Furthermore, if soil and geological conditions are taken into account, in most cases, if not all, the vessels are found in sandy soils that can be dug easily. It is thus not implausible that they are related to burial pits like those excavated at Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice in Lisbon.

A notable concentration of vessels exists around Santiago do Cacém (Monte da Vinha, Herdade dos Aduares, Herdade do Pego da Mangra, nos. 13–15 on Figure 7), an area of sandy soils also known for its numerous Early Neolithic sites (e.g. Silva & Soares, Reference Silva and Soares1981, Reference Silva and Soares2006). The hypothesis we put forward is that the vessels we have listed could originally have marked the presence of burials or were used as grave goods in rather simple funerary practices (shallow graves or pits with no built stone structures) that went unrecognized. Most vessels were not found in the course of archaeological excavations but during field surveys or agricultural work (thus preventing the identification and recording of structures in the subsoil). Furthermore, the local geology severely limited the preservation of organic materials, such as human bone (thus further preventing the recognition of such simple funerary structures). In our opinion, these circumstances led to an array of symbolic interpretations around these findings. Considering the evidence so far obtained at the Lisbon sites, the most parsimonious explanation for the vessels we have listed is that they were grave markers and/or grave goods from lost Early Neolithic pit burials.

The vessels’ typology is clear in terms of relative chronology. As Table 2 shows, there are three main shape types:

• Type 1: pots with narrow necks (Casével, Santarém, Cartaxo, Monte da Vinha, Herdade dos Aduares, Herdade do Pego da Mangra, Retorta).

• Type 2: bag-shaped pots (Praia de São Julião, Castelo dos Mouros, Pinheiro/Sobreiro, Cabranosa, Barranco das Mós?).

• Type 3: cylindrical pots (Ponte da Azambuja, Barranco das Mós?).

In most cases, the vessels feature handles of various types. Such vessel shapes are datable to the second half of the sixth millennium bc and the beginning of the fifth millennium, as shown by the available radiocarbon dates from Early Neolithic cemeteries in Portugal (Zilhão, Reference Zilhão2009; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho2018), where these vessels are usually found. Conversely, their ornamentation varies significantly, from plain pots to vessels decorated with cords, impressed motifs (including Cardial), or boquique. Although reflecting a high degree of stylistic variability, with some diachronic variation (e.g. Cardial in the sixth millennium bc and boquique from the turn to the fifth millennium bc onwards), these motifs are nevertheless all typical of the Early Neolithic and fit the internal stylistic variation of the period. In this line of reasoning, the Cardial vessel from Santarém (Guilaine & Ferreira, Reference Guilaine and Ferreira1970) may indicate that funerary practices involving individual burial pits date back to the earliest Cardial phase in Portugal, around 5500 bc.

Conclusions

Our study has addressed two aspects of research on the Early Neolithic in Portugal, which has so far been characterized by a severe lack of field data: the issue of pottery vessels found complete in isolated locations, and funerary practices. The recent salvage excavations at Armazéns Sommer (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Rebelo, Neto and Ribeiro2018) and Palácio Ludovice (Simões et al., Reference Simões, Rebelo, Neto and Cardoso2020) in the city of Lisbon, have contributed to understanding these issues by revealing burial pits with human remains belonging to single inhumations accompanied by single complete pots.

Comparisons with published evidence suggests that the Alto da Toupeira-Pedreira de Salemas site, in the outskirts of Lisbon, may also belong to a similar funerary context that went unrecognized (Castro & Ferreira, Reference Castro and Ferreira1959; Ferreira & Castro, Reference Ferreira and Castro1967). Similarly, the burial evidence seems to fit the so far only well-documented instance of formal Early Neolithic funerary practices recorded in Portugal: the Caldeirão Cave, where sparse grave goods (one being a Cardial pot) accompanied individual, not collective, burials (Zilhão, Reference Zilhão1992, Reference Zilhão1993). The difference between Caldeirão and the Lisbon burial pits is that in the former case the corpses were laid on the surface whereas in the latter they were inhumed. In both cases, the most common funerary rite was single, not collective burial. In this regard, the evidence from the western façade of Iberia is consistent with evidence from elsewhere in the peninsula, where individual, not collective, burials are characteristic of the Early Neolithic (see Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Rojo, Tejedor, García, Rojo, Garrido and García2012 for a synthesis).

In a recent article, Oms et al. (Reference Oms, Daura, Sanz, Mendiela, Pedro and Martínez2017) published the first evidence of collective practices in the Cardial period (second half of the sixth millennium bc), as observed at Cova Bonica (Catalonia, Spain). In their overview of the Cardial funerary practices in the western Mediterranean and Iberia, these authors underline two main aspects that seem to be characteristic of the Early Neolithic: a heterogeneity of practices (seen for example in the treatment of the deceased, though post-depositional disturbances may be masking the original rituals) and a rarity or total absence of associated grave goods. While this broad scenario for funerary practices in a wide geographical area in the Early Neolithic is useful, our task is complicated by the poorly documented record in central-southern Portugal, which limits our ability to retrieve meaning from seemingly isolated finds.

We hypothesize that apparently isolated vessels may have been part of burial pits that were not identified at the time, owing to their circumstances of discovery (often by non-archaeologists in farming activities) and the possible lack or other grave goods or burial structures (which may have alerted the archaeological community). The lack of human bones can be explained by the acidity of the soils, since most of the finds were recovered from sandy soils. This would also explain the relative lack of Neolithic funerary evidence in Portugal before the onset of megalithism in the early fourth millennium bc, when individual burials gave way to collective burials (Carvalho & Cardoso, Reference Carvalho and Cardoso2015). We stress that, before the discovery of the Lisbon burial pits, Early Neolithic funerary contexts were restricted to caves in the limestone massifs of Estremadura, being unknown in areas with other geologies.

Clearly, the hypothesis of a correlation between isolated finds of complete pottery vessels and burial pits needs further empirical support, but it is our opinion that this possibility is worthy of investigation, given the lacunae that still exist in the study of the funerary realm in the Early Neolithic of western Iberia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Raquel Granja for clarifying aspects of the bioanthropological traits of the individuals buried at Armazéns Sommer and Palácio Ludovice. We are grateful to four anonymous reviewers for their encouraging comments and helpful suggestions which improved our original version; any omissions or errors are our responsibility. João Luís Cardoso and António Faustino Carvalho wrote the manuscript, which was revised by Paulo Rebelo, Nuno Neto, and Carlos Duarte Simões.