Neuroticism

Neuroticism is one of the broad traits at the apex of personality taxonomy. The term neuroticism has its roots in Freudian theory, but the modern concept of neuroticism has been introduced by Hans Eysenck and contemporaries, who used a range of methods from personality psychology, including psychophysiological and lexical studies (Dumont, Reference Dumont2010).

Currently, consensus has developed that, at its core, neuroticism is the propensity to experience negative emotions (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark, Watson, Pervin and John1999; John et al. Reference John, Robins and Pervin2008; Matthews et al. Reference Matthews, Deary and Whiteman2009; Widiger, Reference Widiger, Leary and Hoyle2009), including anxiety, fear, sadness, anger, guilt, disgust, irritability, loneliness, worry, self-consciousness, dissatisfaction, hostility, embarrassment, reduced self-confidence, and feelings of vulnerability, in reaction to various types of stress, and tend to select themselves into situations that foster negative affect (Lüdtke et al. Reference Lüdtke, Trautwein and Husemann2009; Specht et al. Reference Specht, Egloff and Schmukle2011; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Riese, Sanderman and Ormel2014; Riese et al. Reference Riese, Snieder, Jeronimus, Korhonen, Rose, Kaprio and Ormel2014). Importantly, the total ‘excess economic costs’ associated with the 25% highest neuroticism scores in the Netherlands have been estimated at twice that of all common mental disorders (CMDs) combined, and about two-thirds of the excess costs of somatic problems (Cuijpers et al. Reference Cuijpers, Smit, Penninx, de Graaf, ten Have and Beekman2010).

Association with psychopathology

High neuroticism scores are strongly associated with psychopathology, in particular the CMDs, including anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Oldehinkel and Brilman2001; Saulsman & Page, Reference Saulsman and Page2004; Malouff et al. Reference Malouff, Thorsteinsson and Schutte2005; Ruiz et al. Reference Ruiz, Pincus and Schinka2008; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010). An influential meta-analysis quantified neuroticism's cross-sectional association with CMDs, ranging in magnitude from Cohen's d of 0.50 for substance disorders, to 2.00 for some anxiety and mood disorders (Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010). Neuroticism is also prospectively associated with CMDs, although the associations are typically smaller (d = 0.20–0.60, see Lahey, Reference Lahey2009; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimaki and Jokela2015a , Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Raback, Virtanen, Kivimaeki and Jokela b ; Vall et al. Reference Vall, Gutiérrez, Peri, Gárriz, Ferraz, Baillés and Obiols2015).

Neuroticism's prospective association with CMDs has fueled the assumption that neuroticism is an independent etiologically informative risk factor. This vulnerability model postulates that neuroticism sets in motion processes that lead to developing CMDs. However, five other models seek to explain the association, including the spectrum model (extreme neuroticism is called disorder), common cause model (distinct constructs that share determinants), state and scar models (CMD episodes change neuroticism levels temporarily/permanently). Recently we reviewed the validity of these models provided the available literature on confounding of the prospective association by baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, operational overlap, stability and change, determinants, and treatment effects (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013). We concluded that none of the models can account for (virtually) all findings, viz. the state and scar model cannot explain the prospective association, the spectrum model has some relevance, especially for internalizing disorders, but common causes are important as well.

Some of the reviewed findings, such as the prospective associations and interactions of neuroticism with stress (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Gardner and Prescott2003; Lüdtke et al. Reference Lüdtke, Trautwein and Husemann2009; Specht et al. Reference Specht, Egloff and Schmukle2011; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Riese, Sanderman and Ormel2014; Riese et al. Reference Riese, Snieder, Jeronimus, Korhonen, Rose, Kaprio and Ormel2014), are especially consistent with the vulnerability model. Also the higher stability of neuroticism over time than internalizing symptoms supports the vulnerability model (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Nivard et al. Reference Nivard, Dolan, Kendler, Kan, Willemsen, van Beijsterveldt, Lindauer, van Beek, Geels, Bartels, Middeldorp and Boomsma2015a , Reference Nivard, Middeldorp, Dolan and Boomsma b ). However, firm conclusions regarding the vulnerability model were hampered by limited data on the degree of confounding of the prospective association by baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, and the rate of decay of neuroticism's effect over time. The present meta-analysis aims to ameliorate this lack of insight as much as possible, provided the available data, and included studies of the prospective association between neuroticism and CMDs, to compare the strength of the prospective associations by differencing follow-up period, with and without adjustment for baseline problems. Additionally, the present meta-analytic study included some non-CMDs as well, such as thought disorders.

Thought disorders

The link between neuroticism and CMDs received most attention. Nonetheless, neuroticism also appears to be related to a set of prominent cognitive-perceptual and affect regulation problems, grouped in what has been called the schizo-affective-psychosis continuum of ‘thought disorders’ (Markon, Reference Markon2010; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Ruggero, Krueger, Watson, Yuan and Zimmerman2011; Keyes et al. Reference Keyes, Eaton, Krueger, Skodol, Wall, Grant, Siever and Hasin2013). Thought disorders are marked by idiosyncratic perceptions (or ‘positive symptoms’) that are quite common in the general population (Hanssen et al. Reference Hanssen, Bak, Bijl, Vollebergh and Van Os2005; Nuevo et al. Reference Nuevo, Chatterji, Verdes, Naidoo, Arango and Ayuso-Mateos2012), including deviant beliefs (‘delusions’), feelings, and perceptions (‘hallucinations’), which can flair up temporary (i.e. ‘schizotypy’), or decompensate into a full-blown disorder (van Os et al. Reference van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Krabbendam2009; Keyes et al. Reference Keyes, Eaton, Krueger, Skodol, Wall, Grant, Siever and Hasin2013; including schizophrenia, psychotic disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, and schizotypical personality disorders). Thought disorders are also marked by social deficits (‘negative symptoms’), including poor social skills, social anxiety, withdrawal, social disinterests (anhedonia), and impaired perspective-taking ability (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Silvia, Myin-Germeys, Lewandowski and Kwapil2008; Pijnenborg et al. Reference Pijnenborg, Spikman, Jeronimus and Aleman2011). Recently it has been argued that thought disorders represent the most general expression of psychopathology, and may account for the overlap between internalizing and externalizing symptoms/disorders (Lahey et al. Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011; Caspi et al. Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poultron and Moffitt2013; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Perlman, Gámez and Watson2015; Laceulle et al. Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2014). Although thought disorders are less prevalent than the CMDs, they represent an important domain of psychopathology, and therefore it is important to investigate the prospective association between neuroticism and thought disorders.

The present study

The current study seeks to quantify the prospective association between neuroticism on the one hand and CMDs, thought disorders, and non-specific mental distress on the other. Additionally, we seek to quantify the extent of confounding of the prospective association between neuroticism and CMDs by baseline symptoms and/or psychiatric history. To do so, we were particularly interested in studies that assessed psychopathology at baseline (i.e. concomitant with neuroticism), and reported on adjusted prospective associations. For example, prospective associations adjusted for baseline symptoms, or studies that excluded subjects with a history of and/or current psychopathology. Finally, the vulnerability model of psychopathology assumes limited decay of the association with increasing time between baseline assessment of neuroticism and outcome assessment. Therefore the temporal persistence of the prospective association between neuroticism and psychopathology was examined as well. Altogether, all studies that report on univariate and multivariate models for baseline neuroticism prospectively predicting psychopathology were identified (with and without adjustment for baseline problems and psychiatric history), and the reported coefficients were transformed, pooled, and compared in the current meta-analysis.

Materials and method

Search strategy

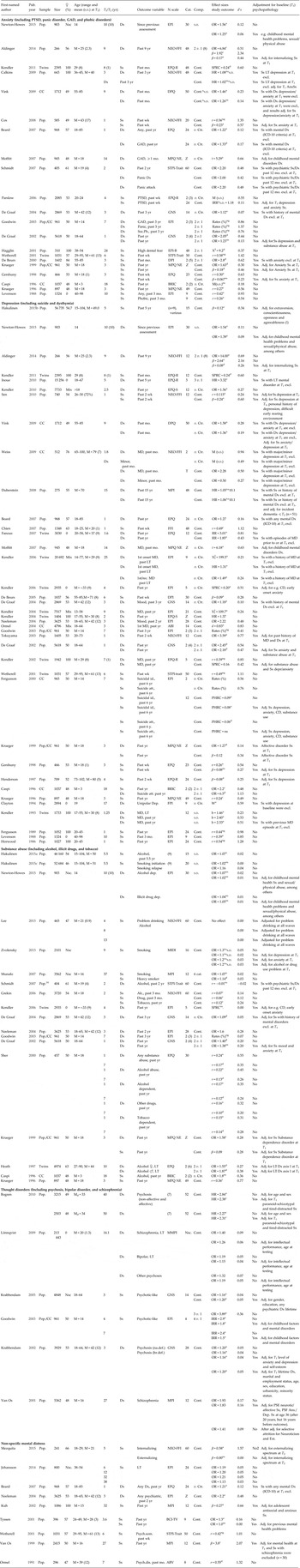

The Web of Knowledge was searched on 1 November 2015 with three search strings; (a) neuroticism, trait anxiety, negative affectivity or emotional stability; (b) mental disorder, internalizing disorder, externalizing disorder, psychopathology, mental health/illness, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, substance dependence, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, psychosis, psychoses, psychotic, psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, paranoid psychosis, schizophreniform disorder, or dissociative disorder, and (c) longitudinal, prospective or follow-up. We also searched the references of the included studies for additional studies to overcome search string limitation. From the manuscripts we coded information on sample size, history of psychopathology, comorbidities, the personality measure, and psychopathology measure (e.g. continuous or categorical/binary Sx or Dx). The application of the search strategy is depicted in a flowchart given as Fig. 1 and all included studies can be found in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the search strategy of studies on the prospective association between neuroticism and common mental disorders, thought disorders and, non-specific mental distress. The sum of all disorders exceeds 63 because some studies assessed multiple outcomes. The percentages (%) indicate the proportion for which this requirement was not met.

Table 1. Prospective population-based studies (k = 63) linking neuroticism (N) to psychopathology [symptoms (Sx) or diagnoses (Dx)]

ABI, Amsterdam Biographic Inventory; ABV, Amsterdam Biographic Questionnaire; Adj, adjusted; Anx, Anxiety; BCI-TV, Basic Character Inventory's trait-vulnerability scale; BFI, Big Five Inventory; BIS, behavioral inhibition system; br.def, broadly defined; BRIC, Behavioral Ratings Inhibited child; cat., categories (i.e. range of the neuroticism scale, e.g. 4 items with a 5-point likert scale is 20 categories); CC, case control; CD, conduct disorder; Comp., comparison (the number of neuroticism levels that were distinguished in the statistical test, e.g. high v. low); Cont, continuous; Dep., Depression; DPI, Dutch Personality Inventory; DPQ, Dutch Personality Questionnaire; DS14, Type D-personality questionnaire; Dx, diagnosis; EPI, Eysenck Personality Inventory; EPI-N, Neuroticism scale of the EPI; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; EPQ-R, Revised EPQ; ES, Emotional Stability; excl, excluded; Ext., Extraversion; FFI, Five Factor Inventory; FPI, Freiburg Personality Inventory; GNS, Groningen Neuroticism Scale; HR, hazard ratio; IR, interquartile range; IRR, incident rate ratio; LT, life time; M, mean; Md, median; MD, major depression; mo., month; Mix, mixed; MPI, Maudsley Personality Inventory; MPQ, Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire; na, not available; N, Neuroticism; na.def., narrowly defined; NE, Negative Emotionality; NEO-FFI, NEO-Five Factor Inventory; Nsc, Nescio (I do not know); OR, odds ratio; PHRC, proportional hazards regression coefficients; Pop., population cohort; Psych.dis, psychological distress; Psych.som, psychological somatization; PSE, Present State Examination; PSF, Psychiatric Symptom Frequency; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; r, correlation coefficient; rec., recurrent; RR, relative risk; s.d., standard deviation; Soc.ph, social phobia; SPRC, standardized partial regression coefficients or path coefficients; ss, subjects; STPI-Trait, State Trait Personality Inventory's Trait-Anxiety measure; Suicidal id., suicidal ideation; Suicidal att., suicidal attempt; Sx, symptoms; T, t score (mean=50, s.d.=10) or t test; v. Ctr, v. controls (without Dx); W, Wilcoxon test; wk, weeks; yr, year; Z, z score (mean=0, s.d.=1).

Notes: (1) Three waves of neuroticism form one latent variable thus the time-span between neuroticism and mental health reflects does not reflect the given follow-up time; (2) The regression equation contained a dummy variable representing inhibited children (v. controls); (3) Neuroticism dichotomized at mean score; (4) Neuroticism dichotomized so that ⅓ received an unfavorable rating; (5) Neuroticism dichotomized at its median score [e.g. De Graaf et al. Reference Gical Me, Bijl, ten Have, Beekman and Vollebergh2004, ⩾5 with scale maximum of 15 (n= 800, or 58%)]; (6) Neuroticism dichotomized above 75th percentile; (7) The Lundby ‘nervouse-tense’ cluster resulted from a mix of observable behaviors rated by psychiatrists (tense, restless, insecure, strained, vegetative, lachrymose, see Hagnell, Reference Hagnell1966) and structured questions (worried, nervous, tense, susceptible to adversity, cries easily, difficult to collect one's thought); (8) Two groups were derived with latent growth analysis and growth mixture modeling, a moderate class (77%, mean intercept= 2.1) and a high class (23%, mean intercept= 2.8), see Aldinger et al. (Reference Aldinger, Stopsack, Ulrich, Appel, Reinelt, Wolff, Grabe and Barnow2014); (9) In these analyses ten studies were pooled, and each sample used different instruments, but with a minimum of 15 items each (Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimaki and Jokela2015a –Reference Hakulinen, Hintsanen, Munafò, Virtanen, Kivimäki, Batty and Jokela c ); (10) The outcomes were measured at age 21, 25, and 30 years, or 4–16 years after baseline, and summarized, with 10 years follow-up as the mean span.

a p < 0.001, b p < 0.005, c p < 0.01, d p < 0.05, ns, non-significant, ng, significance not given.

Study selection criteria

Studies were included that comprised (a) an adult sample that was aged at least 18 years at follow-up (T 2) from (b) the general population with (c) at least 200 participants that assessed (d) neuroticism at baseline (T 1) and (e) psychopathology [symptoms (Sx) or diagnosis (Dx)] at T 2, and (f) the follow-up interval (T 1–T 2) had to be at least 1 year. This means that twin studies were included but patient groups (psychiatric/somatic) and prisoners were excluded. The included measures of psychopathology had to fit the five selected categories of interest: (a) Anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic sreess disorder (PTSD), panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and phobic disorders; (b) Depression, including suicide and dysthymia; (c) Substance abuse, such as illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco; (d) Thought disorders, including psychosis and schizophrenia, and (e) non-specific mental distress.

Non-specific mental distress

A number of studies examined symptoms and signs that either did not meet diagnostic criteria (NOS or subthreshold) or were not assessed in a way that linked them to a specific disorder (e.g. a total of all symptoms). We cumulated these data under a separate category of non-specific mental distress, which is conceptually close to high neuroticism, but importantly, assessed on a different time-frame (‘state’ v. ‘trait’, see Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013, Reference Ormel, Laceulle and Jeronimus2014). Non-specific mental distress refers to a continuum of disturbing or unpleasant emotional/mental states that interfere with one's ability to cope with daily living. Because this cluster may inform hypotheses about the personality–psychopathology association it has been included in this meta-analysis.

Conversion of outcomes

The heterogeneity of the outcome measures only allowed us to conduct a bare-bones meta-analysis in which effect sizes were converted into standardized mean difference d (Hunter & Schmidt, Reference Hunter and Schmidt2004). Conversion formulas were attained from the literature (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal, Cooper and Hedges1994; Sanchez-Meca et al. Reference Sanchez-Meca, Marin-Martinez and Chacon-Moscoso2003; Peterson & Brown, Reference Peterson and Brown2005; Borenstein et al. Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2009), and can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Odds ratios (ORs) that indicated the effect on outcome per scale unit of the raw metric of the predictor were converted to reflect ORs on standardized metric (i.e. per standard deviation of the predictor). In addition, ORs for neuroticism scales that indicated low-neuroticism with high scores were mirrored via 1/ORs to enable comparison. Four included studies reporting hazard ratios were excluded from our meta-analytic estimates, as they cannot be converted to ORs exactly. The relationship index r depicts measures of association or variance accounted for effect size. We classified correlations (r) and betas as small if between 0.10 and 0.20, moderate between 0.20 and 0.30, and large if >0.30, based on the effect sizes commonly found in social psychology (Richard et al. Reference Richard, Bond and Stokes-Zoota2003; Peterson & Brown, Reference Peterson and Brown2005).

Summary statistics

Summary statistics were calculated for each cluster of disorders separately (anxiety, depression, substance abuse, thought disorders, non-specific mental distress). If the study reported multiple outcome measures within a given category on a given sample (e.g. multiple depression scales), effect sizes were averaged to ensure that assumption of independence of observations is met, as recommended by Hunter & Schmidt (Reference Hunter and Schmidt2004). Summary statistics were sample-size weighted to obtain most accurate estimates. If a study reported data on multiple follow-ups, the longest follow-up interval between personality assessment and psychopathology assessment was chosen. Three detailed selection rules were applied for the summary statistics. (a) If manuscripts reported several effect-sizes for the same association (outcome) in the same sample but for different levels of adjustment the best-adjusted effect size was included in the adjusted summary statistic (e.g. exclusion of subjects with a history of psychopathology and adjustment for baseline Sx). (b) If manuscripts reported several effect sizes for the same association (outcome) in the same sample, but for dichotomous and continuous measures, the latter was chosen for analyses. (c) In addition, analyses were stratified by follow-up interval. To do so, we divided our estimates over a short- and long-term follow-up interval, based on the median split; which is an arbitrary decision. This median split was based on the overall median study duration (to increase comparability), but was also calculated for dichotomous and continuous measures separately. In sum, all effect sizes that could be converted into Cohen's d values were used to estimate the summary statistics reported in Tables 2–4.

Table 2. A summary of predictive effects of neuroticism as sample-size weighted effect-sizes d over K studies and N participants

K, Number of studies; N, pooled sample size; d, sample size-weighted average effect size; s.d. d, sample size-weighted standard deviation of effect sizes. Details can be found in the Method section.

Table 3. A summary of the prospective associations between neuroticism and symptoms/diagnosis as sample-size weighted effect sizes d over K studies and N participants, for short v. long time intervals

K, Number of studies; N, pooled sample size; d, sample size-weighted average effect size; s.d. d, sample size-weighted standard deviation of effect sizes. The division of studies over short interval (<4 years) and long interval (⩾4 years) was based on the median follow-up time, which was three years for dichotomous measures, four years for continuous measures, and four years overall (i.e. across all 111 estimates). When studies reported estimates for both short and long intervals both were included in the short v. long interval estimations, but only one was included in the summary estimates. Unadjusted estimates are the direct associations between neuroticism and outcome. Adjusted estimates provide the prospective associations adjusted for symptoms/diagnosis at baseline (see Method section).

Table 4. A summary of the standardized drop in Cohen d per year follow-up interval between neuroticism and symptoms/diagnosis as sample-sized weighted effect sizes d over K studies and N participants

K, Number of studies; N, pooled sample size; d, sample size-weighted average effect size; s.d. d, sample size-weighted standard deviation of effect sizes.

Results

Study selection

A total of 5086 records were screened for inclusion. The selection on title and abstracts reduced the number to 631 papers, which were further scrutinized with the study selection criteria, as outlined above. Eventually 63 studies were included, while the estimates in 59 studies could be converted to Cohen's d. This yielded 111 effect estimates. Our meta-analyses were based on 443 313 participants over almost 5 million follow-up years. At baseline the participants ranged in age from 14 to 104 years.

Some studies were performed in the eligible population and administered all variables of interest, but reported on other variables as predictor and/or outcome (e.g. Bak et al. Reference Bak, Krabbendam, Janssen, de Graaf, Vollebergh and van Os2005). Other studies adjusted the prospective association between neuroticism and outcome for the other four broad personality domains (extraversion/conscientiousness/agreeableness/openness), and although reported in Table 1 (e.g. Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Raback, Virtanen, Kivimaeki and Jokela2015b ), these estimates were excluded from the meta-analytic estimates. Furthermore, our study included two meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies of the association between neuroticism and depressive symptoms and substance abuse (Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimaki and Jokela2015a , Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Raback, Virtanen, Kivimaeki and Jokela b ).

Measurement of personality

Neuroticism was assessed with a variety of standardized questionnaire instruments, including the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (12 items), the revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (12 items), the Amsterdam Biographic Interview (14 items), Basic Character Inventory's trait-vulnerability scale (9 items), the Dutch Personality Inventory (15 items), Dutch Personality Questionnaire (25 items), Groningen Neuroticism Scales (14 items), Maudsley Personality Inventory (12 items), the Freiburg Personality Inventory (9 items), and the State Trait Personality Inventory trait-anxiety measure (10 items). These were all developed to measure negative emotionality, neuroticism, emotional stability, trait-anxiety, and/or trait-vulnerability.

Prospective associations

The large s.d.s around the averages shown in Table 2, indicate that the pool of studies is quite heterogeneous. Nonetheless, the data clearly support the ability of neuroticism to predict all symptoms and diagnoses under study. The estimated unadjusted prospective associations between neuroticism and symptom measures were comparable for anxiety, depression, and non-specific mental distress, and all quite large (about d = 0.70). When these estimates were adjusted for baseline symptoms, the effect size reduced most for non-specific mental distress (−60%), followed by depression (−55%), and anxiety (−45%). The unadjusted prospective associations between neuroticism and diagnosis for anxiety or depressive disorder were slightly lower (about d = 0.50), but the trends were similar to the effects seen for symptom scores, as well as the reduction of the association after adjustment for baseline measures. Hence, regarding internalizing symptoms and diagnosed disorders, and non-specific mental distress, unadjusted associations were about twice the size of the adjusted effects, but adjusted effects remained significant.

The estimated unadjusted prospective association between neuroticism and substance use symptoms was considerably weaker (below d = 0.10), even though estimates for diagnosis had a moderate effect size (d = 0.20). Notably, the latter effect became only little attenuated after adjustment for baseline symptoms (−15%). Although some adjusted estimates appear to be larger than the unadjusted estimates, these differences were small (d⩽0.04), and are probably insignificant. In sum, adjusted effects were reduced by half for internalizing problems, but not for substance abuse and thought disorders.

Temporal stability

A summary of the prospective associations between neuroticism and CMDs is presented in Table 3. Categorization of the follow-up interval over short and long intervals was based on the median study length (short was ⩽4 years, long was >4 years). Overall the unadjusted prospective associations were identical for studies of symptoms and diagnoses (both d = 0.15). However, the unadjusted short-term association was about four times larger than the long-term association, for both symptoms and diagnoses. This indicates a substantial decay of the association with increasing time intervals.

The adjusted effects, on the other hand, were comparable for symptoms and diagnoses (both about d = 0.25). The adjusted prospective associations for symptoms were only slightly larger over the short follow-up interval than over the long follow-up interval, while for diagnosis the long-term estimate was even slightly stronger than the short term effect (yet with d = 0.03 the difference was negligible). Note that all adjusted effects were of moderate effect size, also the long-term associations. So, after adjustment for concomitant problems at baseline and/or psychiatric history, there was little difference between the short and long follow-up interval. This result can be interpreted as concomitant problems at baseline masking the long-term stability of the neuroticism effect on the internalizing CMDs.

Disorder types

The scarcity of studies did not allow for a systematic comparison of prospective associations between neuroticism and each disorder separately. However, the studies given in Table 1 indicate that among the anxiety disorders, large prospective associations were observed for panic disorder, GAD, social phobia, and PTSD, respectively. For depressive disorders the prospective associations were observed for major depressive disorder, minor depressive disorder, and suicidal ideation. Prospective associations between neuroticism and substance use disorders, although small, were observed for smoking and alcohol or illicit drug abuse. Regarding the thought disorders, small prospective associations were observed for schizophrenia and psychosis, but no effect for bipolar disorders.

Post-hoc

The prospective association between neuroticism and the onset of CMDs differs across disorders (e.g. internalizing v. externalizing). Because so little data was available for each specific disorder cluster we combined all disorders when calculating the short-term v. long-term effects, to focus on broad and general conclusions. Post-hoc we also calculated the standardized drop in d values per year for each specific cluster, dividing the effect sizes by the number of years between assessments, as reported in Table 4. This dimensional reduction in d per follow-up year was rather small, and largely comparable across the disorders, in support of neuroticism as a robust prospective marker for the development of psychopathology.

Discussion

In this paper precise estimates are given of the predictive power of neuroticism for the development of psychopathology, as well as effects for individual disorders. Three key observations were found. First, the unadjusted prospective associations between neuroticism and internalizing symptom measures or diagnosis were quite large (d = 0.48 to 0.74, i.e. anxiety, depression, non-specific distress). An adjustment of these estimates for baseline symptoms reduced the effect size by half, but the residual associations remained substantial (d = 0.12–0.38). Second, the unadjusted prospective associations between neuroticism and substance use symptoms and thought disorder symptoms were considerably weaker (d = 0.03–0.20), but importantly, adjustment for baseline problems did not attenuate these effects (d = 0.05–0.17). Third, the adjusted prospective associations between neuroticism and psychopathology remained stable over long follow-up intervals (on average d = 0.25, with little decay per year), bolstering our understanding of neuroticism as an independent and robust vulnerability marker for later developing psychopathology.

Over the past three decades theorists proposed a set of theoretical models to explain the complex longitudinal interrelations between personality and psychopathology and to utilize their conceptual differences to infer hypotheses about mechanisms that can account for their (co-)development (e.g. Tackett, Reference Tackett2006; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Durbin & Hicks, Reference Durbin and Hicks2014). The present study was designed to test inferences from the vulnerability model, which holds that neuroticism sets in motion processes that lead to CMDs. Next to the vulnerability and common cause models (same processes), also the spectrum model (CMDs are extreme levels of neuroticism) and pathoplasty/exacerbation models (independent etiology and onset, but neuroticism influences the course, severity, presentation, or prognosis of CMDs) can account for different aspects of the prospective neuroticism-CMD association, or for different symptom clusters. Different people may even achieve the same end (function) by different means (mechanisms). Next we discuss implications of present findings for each model.

Vulnerability perspective

The vulnerability model postulates that high neuroticism causes the development of CMDs, either ‘directly’, or by eliciting other risk factors. Examples of direct processes are the cognitive vulnerabilities that are associated with neuroticism, including a pessimistic inferential style (negative attention bias and information recall), rumination, increased reactivity (psychological/physiological), ineffective coping/dysfunctional attitudes, intolerance of uncertainty/anxiety sensitivity, and fear of negative evaluation (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Goodwin and Harmer2007; Servaas et al. Reference Servaas, van der Velde, Costafreda, Horton, Ormel, Riese and Aleman2013; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2014; Hong & Cheung, Reference Hong and Cheung2014; Laceulle et al. Reference Laceulle, Jeronimus, Van Aken and Ormel2015). Examples of indirect vulnerabilities is high neuroticism increasing exposure to stressful life events (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Gardner and Prescott2003; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Riese, Sanderman and Ormel2014; Riese et al. Reference Riese, Snieder, Jeronimus, Korhonen, Rose, Kaprio and Ormel2014), and experiencing three times more interpersonal stressful events (Fergusson & Horwood, Reference Fergusson and Horwood1987; Poulton & Andrews, Reference Poulton and Andrews1992; van Os & Jones, Reference van Os and Jones1999; Specht et al. Reference Specht, Egloff and Schmukle2011).

In our test of the vulnerability model we evaluated the ability of neuroticism to predict the onset of a given disorder after adjusting for the symptoms present at baseline and psychiatric history. This was done to adjust (a) for state effects in neuroticism (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Riese and Rosmalen2012; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Ormel, Aleman, Penninx and Riese2013), which are evidenced by our results, and (b) scars that earlier episodes may have left in terms of heightened neuroticism levels (Wichers et al. Reference Wichers, Geschwind, van Os and Peeters2010; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Kotov and Bufferd2011; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013). Our unadjusted estimate of the prospective association between neuroticism and internalizing disorders (d = 0.60) was substantially lower than the meta-analytic estimate of the cross-sectional association by Kotov et al. (Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010, d = 1.65). The cross-sectional estimate was adjusted for unreliability of the included neuroticism scales (as indexed by Cronbach's α = 0.82), which amplified this difference.

The current paper showed that half of the prospective association between neuroticism and internalizing problems was due to relationships with mental state (baseline problems and psychiatric history). These state effects, in which neuroticism levels are temporarily heightened by acute internalizing problems, are temporary, and generally disappear after the episode has remitted (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Oldehinkel and Vollebergh2004, Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Ormel, Aleman, Penninx and Riese2013). A moderate but robust residual prospective association with internalizing problems remained (d = 0.30 to 0.40), in line with the vulnerability model. But not inconsistent with most other models, including common causes, provided that personality develops earlier than a disorder, even without any direct causal connections. Importantly, this control for baseline problems is a conservative test that takes legitimate variance out of neuroticism, especially from the facet traits anxiety and depression (Riese et al. Reference Riese, Ormel, Aleman, Servaas and Jeronimus2016).

For substance abuse and thought disorders the differences between the cross-sectional estimates by Kotov et al. (d = 0.97) and our unadjusted prospective associations (d = 0.20) were even slightly larger. Because baseline problems and psychiatric history did not attenuate the prospective association between neuroticism and substance abuse and thought disorders, neuroticism proves a robust vulnerability factor for their development without much conceptual overlap. Note that the small effect sizes indicate that high neuroticism only plays a modest role in their – undoubtedly multifactorial – etiology, or only for some people.

All adjusted prospective associations between neuroticism and the CMDs were moderate in magnitude and virtually equivalent for the short and long follow-up interval, which indicates that the risk effect of neuroticism did not weaken over time, which is strong support for the vulnerability model. Our results align with previously articulated differences between internalizing (anxiety, depression, non-specific mental distress) and externalizing spectra (substance abuse) of psychopathology and thought disorders (Krueger et al. Reference Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, Silva and McGee1996; Krueger & Tackett, Reference Krueger and Tackett2003; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010), and indicate that neuroticism is close to the origins of their causal pathways, via vulnerability and common causes. These observations support the argument that neuroticism forms the core of a ‘general factor of psychopathology’ characterized by negative-emotional dysregulation (distress) and thought disorders (Lahey et al. Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011; Caspi et al. Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poultron and Moffitt2013; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2014; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Perlman, Gámez and Watson2015; Laceulle et al. Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2014; Pettersson et al. Reference Pettersson, Larsson and Lichtenstein2016).

Common causes

Although our results can be interpreted as evidence for the vulnerability model, they do not falsify alternative models, including the common cause model. The common cause model assumes that neuroticism and mental disorder are dynamic phenomena that can change together in response to external forces and developmental pressures such that both become causally intertwined (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Durbin & Hicks, Reference Durbin and Hicks2014). Only mediation data can disentangle the vulnerability model from common causes, and this was outside the scope of our study. The common cause model is supported by the substantial genetic overlap between neuroticism and CMDs (e.g. Hettema et al. Reference Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott and Kendler2006), although this does not falsify the spectrum model.

Spectrum perspective

The spectrum perspective holds that neuroticism shades continuously into manifestations of psychopathology at the high end of the distribution, and both share their etiological core (e.g. Krueger & Tackett, Reference Krueger and Tackett2003; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013). Importantly, the spectrum model eliminates all conceptual distinctions between neuroticism and CMDs as they tap into the same construct. It follows that (a) the correlation between the measures should approach the reliabilities of the measures and (b) the measures should show comparable patterns of external correlates (Durbin & Hicks, Reference Durbin and Hicks2014); which does not hold for neuroticism (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013). Moreover, the spectrum model implies that psychopathology is simply a label given to extreme scores on a trait, and thus no cases of a disorder will be found below the threshold while all people above the threshold will be cases. The evidence that most people with high neuroticism scores do not experience psychopathology, whereas some people with low neuroticism scores do, contradicts this implication. Further difficulty for the spectrum account is that scoring high on neuroticism prospectively predicts lower romantic and occupational success, subjective wellbeing, longevity, and higher frequency of mental and general health service use (Hills & Argyle, Reference Hills and Argyle2001; Ozer & Benet-Martínez, Reference Ozer and Benet-Martínez2006; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi and Goldberg2007; Steel et al. Reference Steel, Schmidt and Shultz2008; Lahey, Reference Lahey2009), among others. The spectrum model cannot account for individual differences in personal resources and contextual factors that may result in the eventual non-expression of mental health problems (Duckworth et al. Reference Duckworth, Steen and Seligman2005; van der Krieke et al. Reference van der Krieke, Jeronimus, Blaauw, Wanders, Emerencia, Schenk, Vos, Snippe, Wichers, Wigman, Bos, Wardenaar and de Jonge2015), or the natural course and dynamics of personality development – among which a normative decrease in neuroticism of d = 0.77 towards middle age (see Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006), nor the bidirectional relationships between neuroticism and symptoms (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013, Reference Ormel, Laceulle and Jeronimus2014).

Co-development model

Recent reviews of etiological models of personality-psychopathology associations concluded that (a) the vulnerability, common-cause, and spectrum models are imprecise, which impedes the formulation of critical tests to distinguish them, (b) the processes are not mutually exclusive and could co-occur within the same individual or be more relevant for some people than others (Tackett et al. Reference Tackett2006; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Durbin & Hicks, Reference Durbin and Hicks2014), and (c) the models lack a dynamic lifespan perspective in which psychopathology can be conceived of as deviation from normative developmental trends (see Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1993). Additionally, processes that link traits and disorders may also vary across developmental periods (Tackett, Reference Tackett2006; Durbin & Hicks, Reference Durbin and Hicks2014), if only due to different developmental tasks, goals, needs, relationships, developmental contexts, and lifespan personality development (e.g. Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006; John et al. Reference John, Robins and Pervin2008).

Durbin & Hicks (Reference Durbin and Hicks2014) therefore proposed a personality-psychopathology co-development model that incorporates the vulnerability, common causes, pathoplasticity, and exacerbation mechanisms, and accounts for lifespan personality development and dynamic processes via which high neuroticism shapes the ways in which people structure and interact with the world around them to explain individual differences in life experiences and transitions and their impact (e.g. Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Gardner and Prescott2003; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Riese, Sanderman and Ormel2014). In line with the co-development perspective the adjusted prospective association between high neuroticism and internalizing problems can be interpreted as an independent vulnerability effect for the development of psychopathology (neuroticism→Sx/Dx) while the overlap at baseline may reflect state effects, common causes, or symptoms intervening between neuroticism and diagnosis (neuroticism→Sx→Dx). Recall that our adjusted estimate, controlling for baseline symptoms, also removes true predictive variance from neuroticism. Finally, a transition to and from a psychiatric disorder may proceed as a categorical sudden transition for some people but in terms of a smooth process of change in others (Borsboom et al. Reference Borsboom, Rhemtulla, Cramer, van der Maas, Scheffer and Dolan2016). Nonetheless, a salient difference between the co-development and spectrum models remains that the former retains conceptual distinctions between neuroticism and disorder.

Future studies

Our understanding of the etiology of psychopathology and early detection and intervention of CMD is unlikely to expand via additional studies of cross-sectional neuroticism–CMD correlations. To further clarify different perspectives we need a deeper understanding of the boundaries between neuroticism and psychopathology, such as function v. dysfunction (DSM-5), or trait descriptors as self-identity in semantic memory and mental symptoms as episodic memories (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Laceulle and Jeronimus2014). Also questionnaires without item overlap are needed (Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013). And the inclusion of potential common causes and external correlates of neuroticism and CMDs in longitudinal designs.

At least as important may be the study of individual differences in their individual developmental context and developmentally informed mechanisms underlying the independent prospective association between neuroticism and CMDs. For example, mediation of the vulnerability effect by cognitive biases inherent to neuroticism (e.g. Laceulle et al. Reference Laceulle, Jeronimus, Van Aken and Ormel2015), or moderation of effects by contextual and sociodemographic factors, ethnicity, or other personality traits. Evidence suggests that CMDs share a pleiotropic genetic susceptibility that is manifest via dysfunction in neurobiological systems, while different interactions with one's environment somehow differentiate between specific disorder outcomes (e.g. Lahey et al. Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011). This underscores the need for research designs that can account for both inter-individual and intra-individual variance, such as experience sampling, which may help answer questions about processes that underlie the neuroticism-psychopathology link (Molenaar, Reference Molenaar2008; van der Krieke et al. Reference van der Krieke, Jeronimus, Blaauw, Wanders, Emerencia, Schenk, Vos, Snippe, Wichers, Wigman, Bos, Wardenaar and de Jonge2015).

Finally, studies could improve by accounting for more hierarchical aspects of the personality and psychopathology, which may also increase our understanding of causal processes. Neuroticism comprises multiple lower-order facet traits, including anxiety, depression, angry-hostility, self-consciousness, impulsiveness and vulnerability (Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae2006). The facets of neuroticism differ in their underlying biology, developmental trends, impact on impairment, and risk factors (Jeronimus, Reference Jeronimus2015). But also specific CMD symptoms including sadness, insomnia, concentration problems, or suicidal ideation, associate with differences in external outcomes, including social relationships, work, and subjective wellbeing (e.g. Fried et al. Reference Fried, Nesse, Zivin, Guille and Sen2014; Fried & Nesse, Reference Fried and Nesse2015). Research at this level of granularity may therefore also advance the development of personalized prevention and treatment strategies (Borsboom & Cramer, Reference Borsboom and Cramer2013; van der Krieke et al. Reference van der Krieke, Jeronimus, Blaauw, Wanders, Emerencia, Schenk, Vos, Snippe, Wichers, Wigman, Bos, Wardenaar and de Jonge2015), which can impact both high neuroticism and CMD episodes (Barlow & Nock, Reference Barlow and Nock2009; Lahey, Reference Lahey2009; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013).

Implications

Our results clearly show independent prospective associations between high neuroticism and manifestations of psychopathology and mental distress. Extant work indicated that neuroticism levels are more malleable than researchers long believed, including the potential of a benign transactional cycle between positive contextual changes and decreases in neuroticism (Lüdtke et al. Reference Lüdtke, Roberts, Trautwein and Nagy2011; Kuepper et al. Reference Kuepper, Wielpuetz, Alexander, Mueller, Grant and Hennig2012; Jeronimus et al. Reference Jeronimus, Ormel, Aleman, Penninx and Riese2013, Reference Jeronimus, Riese, Sanderman and Ormel2014). Multiple studies showed the feasibility of ‘treating’ high neuroticism or specific neuroticism facets (Jorm, Reference Jorm1989; Zinbarg et al. Reference Zinbarg, Uliaszek and Adler2008; Glinski & Page, Reference Glinski and Page2010; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Oades and Caputi2014; Hudson & Fraley, Reference Hudson and Fraley2015), both via psychological and pharmacological interventions (d = 0.40–1.25). Therapists could thus focus on prevention strategies that target the vulnerability for mental disorders inherent in neuroticism, rather than only treating the subsequent manifestations of those disorders (Lahey, Reference Lahey2009; Cuijpers et al. Reference Cuijpers, Smit, Penninx, de Graaf, ten Have and Beekman2010; Ormel et al. Reference Ormel, Jeronimus, Kotov, Riese, Bos, Hankin and Rosmalen2013; Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2014). This could be implemented as aftercare of psychological counseling. From a dynamic system perspective the most promising and rigorous measure to improve future mental health might be to target the developing personality structure from primary school age onwards to smoothen the mental biases and developing belief systems that otherwise could develop into high neuroticism throughout adolescence, to alleviate the observed vulnerability for the co-development of mental disorders associated with high neuroticism.

Limitations

The present work extends earlier work on neuroticism-psychopathology associations to a critical evaluation of the prospective associations to shed light on the vulnerability hypothesis of psychopathology. Other broad personality traits have often been linked to CMDs as well, namely, low Conscientiousness, and to a lesser extent, Extraversion, although their association with CMDs is not as strong and pervasive as that of neuroticism (e.g. Clark, Reference Clark2005; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott and Kendler2005; Malouff et al. Reference Malouff, Thorsteinsson and Schutte2005; Fanous et al. Reference Fanous, Neale, Aggen and Kendler2007; Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010; Klein et al. Reference Klein, Kotov and Bufferd2011; Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimaki and Jokela2015a , Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Raback, Virtanen, Kivimaeki and Jokela b , Reference Hakulinen, Hintsanen, Munafò, Virtanen, Kivimäki, Batty and Jokela c ). Analyses of these traits are outside the scope of this meta-analysis, but we believe that the implications of our findings on neuroticism are relevant for understanding the relationship between other personality traits and CMDs as well. In this meta-analysis studies that adjusted their neuroticism effects for the other personality traits were excluded. Our aim was to control for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history to establish the likely direction of causality, and adjustment for other traits does not help with that, while it changes the nature of the effect (i.e. it is not whole neuroticism that now predicts). Nonetheless, studies that included all traits supported the primacy of neuroticism (e.g. Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Batty, Virtanen, Kivimaki and Jokela2015a –Reference Hakulinen, Hintsanen, Munafò, Virtanen, Kivimäki, Batty and Jokela c ). Finally, in this paper studies with widely different instruments were compared, and as in previous comparisons, these instruments yield different effects. For example, neuroticism as measured by instruments derived from Eysenck's tripartite taxonomy (MPI, EPI, EPQ, EPQ-R) appeared less predictive for psychopathology than the NEO scales (cf. Kotov et al. Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010).

In some categories in Table 3 the s.d. is larger than the mean, which reflects the substantial variability between the estimates. Arguably this is due to the different study groups, from different countries, administered with different instruments and methods. Although large s.d.s may suggest unprecise estimations (due to dispersion), this does not imply that the mean point estimate is not a good parameter. Furthermore, neuroticism's associations with symptom measures based on self-ratings are typically stronger than for diagnoses (Table 2). Diagnoses are typically based on diagnostic interviews. These differences were largest for the internalizing problems (i.e. anxiety, depression, and non-specific mental distress), but reversed for substance abuse and thought disorders. This suggests the existence of method variance, as both neuroticism and symptom measures are typically assessed with self-ratings, whereas diagnostic interviews are based on self-report in response to interviewer questions. Unfortunately, our estimation method impedes an estimate of method variance in the observed prospective associations with diagnoses. Note that in our overall effect estimates, these differences between symptoms and diagnoses disappeared (Table 3).

Conclusion

Our results indicate that high neuroticism and psychopathology are not only closely interwoven but that neuroticism is also an important prospective indicator of risk for the development of psychological disorders in the internalizing domain, especially anxiety, depression, and non-specific mental distress. Neuroticism is also a vulnerability factor for the development of substance abuse and thought disorders, although these effects are much weaker. Half of the prospective effect remained after adjustment for baseline psychopathology and psychiatric history. Particularly relevant is the long-term stability of the residual vulnerability effect of high neuroticism. Whereas the unadjusted short-term effect estimates were four times larger than the long-term effects (suggesting a substantial decay of the association with increasing time intervals), the adjusted short-term effect was only slightly larger than the long-term effect. Collectively, our results identify high neuroticism as a stable and significant vulnerability factor for the development of CMDs.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001653.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and reviewers for their suggestions.