Introduction

Security is usually considered to be a ‘good’ thing. State representatives often use it to justify and legitimise policy choices – if anything, security is becoming more dominant as a theme in international politics. But one of the peculiarities of the concept of security is its vagueness: it has long been recognised that ‘the term “security” covers a range of goals so wide that highly divergent policies can be interpreted as policies of security’.Footnote 1 It has always had contested – and even contradictory – meanings.Footnote 2 Debates about the meaning of security have suggested that it is essentially contestable by its very nature, and that the very ‘essence’ of security is contested.Footnote 3 Alongside this broader conceptual interrogation, the field and the pages of this journal have seen a debate emerge over the value of security.Footnote 4 At its heart this is a debate over ethics: about the extent to which security is a ‘good’ and whether or not security politics produces the kind of world we want.Footnote 5 So, the debate over the value of security is crucial to thinking about how we want to live.

However, the existing debate is limited. Traditional security scholars overlooked the normative dimension of security. Hans MorgenthauFootnote 6 and Arnold Wolfers addressed morality in security politics, and the latter also considered the ambiguities of national security politics, but even here security is considered to be ‘nothing but the absence of the evil of insecurity, a negative value so to speak’.Footnote 7 Early peace studies engaged with ethics more directly, from the World Order Models Project to Johan Galtung’s theorising of positive conditions for peace.Footnote 8 But mainstream security studies and International Relations largely failed to advance these debates until the emergence of critical security studies in the 1990s. Here, some early contributions viewed security as a ‘positive’ value to be fought for, with a strong emancipatory agenda.Footnote 9 Arguing that being secure is a fundamental human need, they made explicitly normative arguments about what security should be about. On the other hand, alongside this a growing number of authors emphasised the often problematic and exclusionary nature of national security politics, arguing that security is best avoided since it does not lead to desirable politics.Footnote 10 There is not enough space to detail the various contributions of critical security studies here, only to say that it has pushed research on security politics in important new directions. Although criticised for assuming there is a ‘universal security logic’,Footnote 11 the field has produced further debate over what characterises ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ security politics,Footnote 12 centred on what kind of world we can, or even should, strive for.

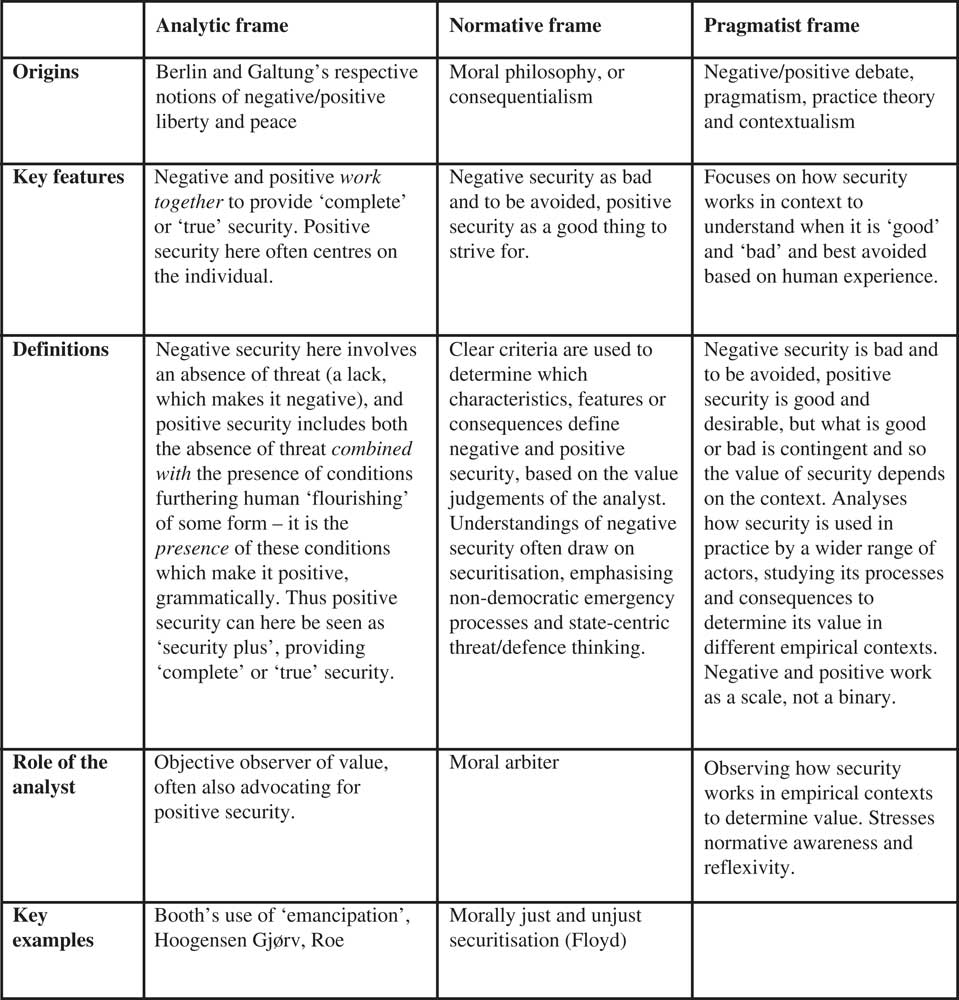

But this debate is itself confusing and unclear: authors use the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ security in different, and sometimes contradictory, ways. This article draws together and clarifies the contemporary ‘negative/positive’ debate that has been ongoing in the field and has featured prominently in Review of International Studies. I divide the debate into two uses of the terms negative and positive. The first use is based on an analytical understanding of positive and negative, drawing on Berlin or Galtung’s respective distinctions between negative and positive freedom/peace. I label this the ‘analytic frame’: here negative security represents an absence of threat, while positive security represents further enabling conditions for human wellbeing. So, in the analytic frame, negative and positive security work together to produce a more complete security. The second use is based on a normative understanding of positive and negative, and tends to draw on securitisation theory. I call this the ‘normative frame’: it makes a normative judgement aiming to understand when security is good or bad based on various theoretical criteria. Here, negative security is seen as something ‘bad’ to be avoided, and positive security is seen as something ‘good’ to strive for. Therefore, the normative frame suggests negative security should be rejected in favour of positive security (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The contemporary debate.

These frames draw on different literatures, but their differing meanings have been a source of confusion and have stalled the debate over the value of security. Although both tackle the value of security – adding valuable insights – they consider different aspects. The analytic frame analyses gradations of security and the extent to which they provide security in a meaningful sense. The normative frame, meanwhile, recognises that not all security practices are desirable and tries to understand the normative consequences of particular security practices. Both are important endeavours, but we need to recognise that in some ways they are actually different projects and dividing them into two distinct frames will hopefully encourage this. Lastly, both the analytic and normative frames focus on establishing theoretical criteria to define positive and negative as opposed to analysing how security works in practice. As a result, they do not sufficiently recognise contextual variation in the value of security.

Having clarified the different uses of these terms, I propose an alternative approach to overcome these tensions, which I label the pragmatist frame. This brings the contributions of the analytic and normative frames together, but focuses on studying the value of security in context. Although there is not enough space to introduce a fully-fledged new theoretical framework here, the final section is devoted to exploring this further. Here I draw on the pragmatist philosophy of John Dewey and William James, practice-centred approaches, and contextualism. Drawing on Ciută’s argument that security does not have an unchanging ‘essence’ or meaning,Footnote 13 I suggest that it also has no inherent value: this has serious implications for the negative/positive debate. If the value of security is contextual and unfixed, the focus should shift from defining what makes security practices positive or negative in the abstract, to studying actual situated security practices in context and using this to make conclusions about the value of security in that particular case. Reflexivity is essential here: such analysis has to be accompanied by a shift from fixed normative commitments towards normative awareness. This may in turn help practical analysis (and critique) of existing notions of security and security policy. While further research is needed to develop this, I hope this contribution will open space for exploring a new way forward for understanding the value of security.

The article’s central contribution is thus to clarify the debate over the value of security, drawing out the different uses of the terms ‘negative’ and ‘positive’, and proposing an alternative pragmatist route. Because the focus here is on the debate over the value of security and how security is currently used, it does not tackle the bigger question of what or which issues should or shouldn’t be constructed as security issues, as this is beyond the scope of the article. However, studying the ethics of security implies a normative approach, where the analyst/s is/are recognised as ‘active participants in the security discussion’.Footnote 14 The article begins with a discussion of the ethics of security, distinguishing between securitisation and the construction of security. It then examines the negative/positive debate, drawing out the analytic and normative frames in the key contributions on the topic. Lastly, it develops the pragmatist frame drawing on these uses and building on them to create a pragmatic, contextual, and practice-centred approach to the value of security. The final section discusses the implications.

Debating the ethics of security

Critical security studies emerged in the 1990s as a critique of dominant state-centred security studies and politics, to question what security is and whom it is for. Most authors writing in this tradition agree that the meaning of security is constructed. Consequently, critical security studies has engaged with ideas on the value and ethics of security directly, with two of the most influential early approaches presenting contrasting views. The Copenhagen School study security as securitisation, viewing security as negative and usually best avoided.Footnote 15 Meanwhile, the Welsh School define security as emancipation, emphasising its positive value and potential.Footnote 16 Alongside this, there have been ongoing debates over the referent of security, including attempts to attach normatively positive adjectives to security to overcome the negative aspects, from global security to human security, which have made important contributions.Footnote 17 These perspectives have provoked growing debate over the nature, or value, of security. While it doesn’t use the language of the negative/positive debate, the Welsh School’s understanding of security is closely aligned with the analytic frame, and is therefore discussed in more detail later. This section now turns to discuss the influence of the Copenhagen School’s securitisation theory on the negative/positive security debate.

Securitisation theory has played an important role in fuelling scholarship on the politics and ethics of security, and many of the contributions in the negative/positive debate explicitly use securitisation as a starting point or even as shorthand for security. The Copenhagen School argue that issues ‘become’ security when a (usually elite) actor constructs them as such and this designation is accepted by the relevant audience, moving the issue out of the realm of regular democratic politics and into the realm of security where extraordinary emergency measures are enabled.Footnote 18 Securitisation is seen to have ‘inevitable negative effects’, including ‘the logic of necessity, the narrowing of choice, the empowerment of a smaller elite’.Footnote 19 The Copenhagen School argue that security cannot escape its traditional connotations because of how it is used in the field of practice: in historical terms, it is national security.Footnote 20 They view the realm of security as opposed to normal politics and based on these assumptions they argue that in most cases ‘security should be seen as a negative, as a failure to deal with issues as normal politics’.Footnote 21 As a result, they suggest that while securitisation may sometimes be necessary most issues are best dealt with outside of the security sphere, or ‘desecuritised’.Footnote 22 The limits of securitisation theory have been covered elsewhere so will not be dealt with in-depth here.Footnote 23

Many more recent contributions to the negative/positive debate draw on securitisation theory, but the debate suffers from a lack of distinction between ‘security’ and ‘securitisation’. Following Matt McDonald,Footnote 24 I argue that securitisation only represents a particular type of security construction. While arguing that ‘the meaning of a concept lies in its usage and is not something we can define analytically or philosophically according to what would be “best”’,Footnote 25 Barry Buzan et al. simultaneously limit the meaning of security to very specific usages by particular actors. Felix Ciută discusses this in-depth, arguing that the Copenhagen School’s theoretical definition of security takes precedence over situated security practice, limiting analysis to how security works when situated actors ‘happen to act in theoretically prescribed ways’.Footnote 26 Consequently, securitisation theory neglects security when it doesn’t fit the framework, such as when it is framed using a different language of security that does not rely on friend/foe distinctions and non-democratic procedures. These do not enable emergency measures and are therefore not cases of securitisation. Based on their definition of security, the Copenhagen School broadly favour desecuritisation. However, in privileging a particular notion of ‘security’ that can only be articulated by those in a position of power, they overlook the ways in which other actors already contest dominant notions of security and threat, articulating alternative, more positive, concepts of security.Footnote 27 The Copenhagen School struggle to see security when it does not follow their rules. Therefore, I suggest that securitisation theory presents a narrow, particular understanding of security, rather than the understanding of security.

While critical approaches to security have been concerned with both the politics and the ethics of security, they have tended to assume security has a universal logic. The emerging debate on the value of security presents a more nuanced perspective, exploring which characteristics or features make security negative or positive.Footnote 28 Yet, as noted in the introduction, there are clear variations between key authors’ definitions of ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ security and these differences are not addressed or made explicit. Some of this confusion is inevitable, reflecting the fact that different approaches have developed from distinctive literatures, focus on different dimensions of security, and have different normative commitments. Most obviously some authors focus on security as a state of being, while others analyse security as a process or practice: those who focus on security as a state of being tend to be more optimistic about its positive potential, while those who study security as a process tend to point to the problematic features or consequences of existing security processes.Footnote 29 However, the two are not always easy to separate,Footnote 30 and few authors who focus on security as a state of being overlook security as a process. The different uses of the terms positive and negative matters and needs to be acknowledged, since it stalls the debate as people talk at cross-purposes. While recognising that security can be positive or negative, authors also continue to define what is negative and positive in the abstract. The debate over the value of security raises important questions about what kind of politics we desire. To move forward we need a common language, or at least open recognition when we are talking about different things. We also need to recognise that what is good is usually dependent on the context: this is discussed further in the final section.

The analytic frame: an absence of threat and ‘security plus’

The first common use of negative/positive security is based on an analytical understanding of the terms, drawing on Berlin and Galtung’s respective notions of negative/positive liberty and negative/positive peace, which are well established in the discipline. It conceives of negative security as an absence of threat, and positive security as an absence of threat combined with the presence of conditions furthering human ‘flourishing’ of some form. Positive security in this sense can be understood as ‘security plus’. This is analogous to the way that negative peace is about the absence of physical violence/war and positive peace is about the absence of war plus ‘the integration of human society’.Footnote 31 In the analytic frame, attaining negative security is about preventing threats from harming the wellbeing of the thing to be secured; in this sense negative security is essentially a lack, an absence of threat – this is why it is negative. Meanwhile, attaining positive security involves both protection from threat/s and the presence of conditions furthering active human ‘flourishing’ of some kind. Following this approach, being truly secure is not simply about being safe from threats but has to involve also advancing towards some state of the good in which one has the means for active fulfilment. Thus, the analytic frame analyses gradations of security and the extent to which they provide security in a meaningful sense. So in this usage, negative security is not seen as a ‘bad thing’: it is negative because it represents an absence, and is therefore limited rather than problematic. In this sense the analytic frame has strong ties to peace research and its attempts to understand peace as more than an absence of war.

Ken Booth was the first to use this interpretation of negative/positive security, though without the explicit use of these terms. His seminal 1991 Review of International Studies article ‘Security and emancipation’ defines security as the ‘absence of threats’ and emancipation as the enabling, positive concept: ‘the freeing of people (as individuals and groups) from those physical and human constraints which stop them carrying out what they would freely choose to do’. Consequently, he concludes that ‘security and emancipation are two sides of the same coin’, and ultimately ‘true security’ requires more than an absence of threat – it requires emancipation.Footnote 32 In his 2007 book, Theory of World Security, Booth expands on this to suggest that genuine security is more than survival: ‘[s]urvival is not synonymous with living tolerably well, and less still with having the conditions to pursue cherished political and social ambitions … In this sense, security is equivalent to survival-plus (the plus being some freedom from life-determining threats, and therefore space to make choices).’Footnote 33

Bill McSweeney presents a different interpretation, developing the first explicit notion of positive security. He draws on Berlin to distinguish between ‘security’ as equivalent to an absence of material threats, and the term ‘to secure’, arguing that the latter provides an alternative positive image which suggests ‘enabling, making something possible’ – here both images are necessary.Footnote 34 He differentiates between ‘security’ as referring to the state level or image, and ‘secure’ as referring to the (positive) human/individual image.Footnote 35 He argues that the human level has been ignored in favour of the state level and turns to sociology to argue that ‘human needs encompass more than physical survival and the threats to it’.Footnote 36 If you define security simply as the absence of material threats to the state, McSweeney suggests, you ignore ‘much that is relevant to a policy designed to achieve security’.Footnote 37 He develops the concept of ontological security to explain what it means to be secure for human beings, emphasising the ‘security of social relations’ relating to social order and ‘the conditions which facilitate confidence in the predictability and routine of everyday social life’.Footnote 38 However, external threats to the state also affect ontological security, so here positive and negative security work together to form a complete whole.

Other authors move between this notion of absence of threat/security plus and using positive and negative normatively. Roe draws on both Berlin and Galtung to explain his use of positive security.Footnote 39 In much of his 2008 article on the subject, ‘The “value” of positive security’, he presents an understanding of positive security as being about ‘having content’ (security plus) – as opposed to an absence of threat. He draws on McSweeney, aiming to take his notion of positive security beyond human or individual security. He links positive security to (state) pursuit and defence of ‘just values’, arguing that the state can and should actively ‘pursue positive security’Footnote 40 – but here it is not simply about the presence of positive conditions for human flourishing but about the type of foreign policy that is pursued by a state and the type of values that it represents/protects:

Whether we are pursuing ‘freedom to’ or ‘freedom from’, whether we are concerned with ‘security’ or ‘securing’, we are, in doing so, necessarily making a judgment that certain values must be maintained; that this has to be protected, that this is core. And many orders, including the international order after the 11 September terrorist attacks, make such judgements. Positive security is, in this way, the maintenance of just, core values.Footnote 41

Of course, protecting and maintaining just values could be seen as ensuring or enabling human development and emancipation, which fits more neatly into positive security as ‘security plus’. However, here both negative and positive security involve a judgement about what kind of values to protect. This complicates what we mean by an ‘absence of threat’, as we are no longer talking about the mere survival of a referent object. This pushes beyond the analytic frame and is discussed further in the next section.

Hoogensen Gjørv also uses the terms positive and negative in this way. She draws on Berlin, noting that negative security equates to ‘“security from” (a threat), and positive security to “security to”, or enabling’.Footnote 42 She uses this to argue that positive and negative security can work together. She suggests that negative security tends to be associated with traditional security, whereas positive security is more useful as a critical tool to examine the gaps ignored by traditional (negative) security.Footnote 43 Here, she links negative security closely with traditional state and military actors, and positive security with non-state and non-traditional actors, which makes sense in this usage of the terms. Like Roe, she is reluctant to reject negative security, suggesting negative security can also involve values of justice.Footnote 44 She suggests that positive and negative security are conceptually distinct and involve different actors and different practices, which can be complementary. Overall, the idea of positive security as being more than a ‘lack’ or absence of threat is key in both Roe’s and Hoogensen Gjørv’s work. They both link negative security with survival and an absence of threat, and often specifically with state practices (including violent practices and the use of force), and they lean towards seeing it as complementary to positive security.

From this it is clear that in the analytic frame, whether positive or negative, security is generally considered to be a good thing. Here negative and positive can be used to measure the level of security in a given situation, with negative security representing a limited version of security where you are safe from threats and positive security providing additional opportunities. Together they provide a more complete security or even emancipation. Theoretical criteria are used to define what characterises negative and positive security, such as the actors involved, the practices they use, the values they promote, or the referent they focus on.

The normative frame: Security comes in good and bad forms

The normative frame attempts to understand and analyse the normative consequences of different security practices and understandings of security. It uses positive and negative security as value judgements: here, negative security is seen as something ‘bad’ to be avoided, and positive security is seen as something ‘good’ to strive for. This category of usage is particularly tied up with securitisation theory and normative critiques of securitisation.Footnote 45 Criteria are used to determine which characteristics, features, or consequences define negative and positive security, respectively, based on the value judgements of the analyst (declared or otherwise). These could be attached to procedure: if particular security practices are undemocratic and I think that is a bad thing, then securitisation or treating an issue as security in this way is negative from my perspective. Conversely, if other security (or even desecuritised) practices are more democratic or involve a larger number of actors, these practices are positive from my perspective. Value judgements can also be attached to the consequences or outcomes of security/securitisation. Here, security is positive if the analyst deems the consequences of security/securitisation to be ‘good’, and vice versa. Roe and Hoogensen Gjørv both use positive and negative in this sense at times, though Floyd has a more distinct usage so her approach is dealt with separately below.

In his 2012 article, ‘Is securitization a negative concept?’, on the value of the concept of securitisation, Roe draws on securitisation theory and its critics to suggest that security is increasingly seen as negative because of its processes (non-democratic, fast-tracked procedures) and its outcomes (reproduction of threat-defence, friend/enemy dichotomies).Footnote 46 Here negative security is not simply an absence of threat, but rather the presence of negative (read problematic), violent/undemocratic security practices and outcomes. He suggests this understanding of security rests on a narrow interpretation of both securitisation and security, arguing that security can also be positive. Thus while recognising that security/securitisation can be ‘bad’, he argues that it is not as negative as securitisation theory suggests, and that different, more positive or ‘good’ constructions of security also exist. Here negative and positive security are defined in the normative sense.

Turning now to Hoogensen Gjørv, as has been noted she generally distinguishes between negative and positive security in the analytic sense, viewing the two as different but complementary. However, her association of the two terms with different actors, practices, and characteristics suggests a preference for positive security and at times suggests negative security can be problematic. In her approach, the role of actors is key – negative security is related to traditional militarised and state-centred security. It is hierarchical, rendering ‘passive any possible agents of security outside of the state’.Footnote 47 Meanwhile, positive security is understood as centred on trust, as ‘multi-actor’ with actors above and below the state as well as active referents. Thus rather than the concepts being complementary, in another description of the debate she suggests that negative security is ‘security as a concept we wish to avoid, one that should be invoked as little as possible … on the other hand, security has also been known to represent something that is positively valued, or as something that is good or desired’.Footnote 48 Here positive and negative security are distinct, and not complementary. Expanding on this, she argues that negative security is about survival, and ‘employs an epistemology of fear, focused on the identification of threats and the use of violence’,Footnote 49 which is clearly much closer to the Copenhagen School’s use of security/securitisation. In this usage, Hoogensen Gjørv explicitly distinguishes positive and negative by ‘the epistemological foundations of each (fear or enabling), the security practices (violence vs non-violence), and the actor (state or non-state) that is creating security’,Footnote 50 which suggests positive security is preferable in most cases.

A different normative approach to judge the value of security has been developed by Floyd. She draws directly on securitisation theory and takes an explicitly normative position on the terms, defining negative security as ‘bad’ and positive security as ‘good’, or ‘just’, in her later terminology. In earlier work she uses the terms positive and negative to describe ‘how well any given security policy addresses the insecurity in question’,Footnote 51 focusing on the consequences of constructing an issue as security. Here, the value of security depends on whether there is an ‘objective existential threat’ and a ‘legitimate referent object’ (for Floyd, it needs to be ‘conducive to human wellbeing’).Footnote 52 In this way, securitisations are judged on their consequences. In later work, she turns to the language of moral philosophy to endorse ‘human wellbeing as the highest value’.Footnote 53 Again, she argues that security in itself has no value: rather, only the consequences of securitisation matter and these can be judged as morally right or wrong depending on the extent to which they further human wellbeing. She usefully highlights the fact that the consequences of securitisation are not always exclusionary.Footnote 54 The consequences or outcomes differ in different cases, and it is these that matter.

However, her approach is closely linked with the Copenhagen School’s distinction between the spheres of politics and security. As a result, Floyd suggests that a positive securitisation is ‘faster, better’ and more efficient than politicisation.Footnote 55 She thus still subscribes to the Copenhagen School’s binary distinction between security and political processes. Likewise, she continues the Copenhagen School’s focus on elites as the ‘speakers’ of security.Footnote 56 While she puts forward a clear and useful agenda to judge security by ‘the maximisation of genuine security’ (recognising that ‘security is neither always positive nor always negative but rather issue dependent’), she nevertheless retains a narrow view of security heavily influenced by the Copenhagen School and predicated on theoretical criteria for what makes particular practices ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Moreover, focusing on consequences neglects other factors which may affect the value of security, including security processes/practices and the number and type of actors involved, which as Hoogensen Gjørv and Roe both highlight, can also affect the value, or desirability, of security and security practices.

From this, it is clear that negative security can be seen either as an ‘absence of threat’, a basic condition of survival, or normatively, as the presence of conditions or practices that we should avoid. Positive security, meanwhile, can be understood either as ‘security-plus’, an add-on to basic survival with the presence of further enabling conditions, or normatively as security in its ‘good’ form which we should strive for. Both frames have merits, particularly in starting a more nuanced discussion on the value of security. However, although both address the value of security and provide useful perspectives on this important issue, the dual use of the terms positive and negative makes the debate difficult to follow. It masks the different and important contributions of the analytic and normative frames: the former allows us to conceptualise security as a good on a sliding scale, from a more limited absence of threat to a more complete security-plus. The normative frame allows us to recognise that security politics can also be bad, as noted by a range of authors in critical security studies, not least the Copenhagen School. The dual usage of the terms also makes engagement between authors more difficult, which in turn makes it difficult to move the debate forward. Lastly, both the analytic and normative frames focus on establishing theoretical criteria to define positive and negative. As a result, they do not recognise contextual variation in the meaning and value of security. With the exception of Hoogensen Gjørv, the debate also continues the Copenhagen School’s focus on elites as the actors/speakers of security.

This article now turns to suggest an alternative that overcomes some of these tensions. It builds on the contributions of the analytic and normative frames, but focuses on studying the value of security in context. Context is mentioned by the key authors in this debate but rarely elaborated upon or taken to its logical conclusions. Roe’s 2014 article, ‘Gender and “positive” security’, draws on feminist work to emphasise context in positive security (here equated with emancipation).Footnote 57 Hoogensen Gjørv relates practice and context more closely to the negative/positive debate, arguing for a ‘multi-actor, practice-oriented security framework’.Footnote 58 However, she still largely delineates between positive and negative security based on which actors are involved. Floyd also suggests in earlier work that ‘security is … issue dependent’.Footnote 59 In her case however, this means looking at how security is used in practise by elite actors following specific criteria of securitisation and judging the value on the outcome. Thus, existing approaches still rely on theoretical definitions as opposed to analysing how security works in context. The rest of this article is devoted to exploring the possibility of using pragmatist, practice-centred, and contextualist contributions to analyse the value of security by looking at how it is used in different contexts.

Towards a pragmatist frame

The alternative frame I propose bridges the analytic and normative frames but focuses on analysing how security is used in different contexts to gain practically useful knowledge.Footnote 60 I retain the normative use of positive and negative as good and bad respectively, to recognise that security can be problematic, but use the analytic frame to suggest that while we cannot define what characterises ‘good’ or ‘bad’ security in the abstract, the ‘goodness’ of different security practices in a context should be understood on a scale rather than in binary terms. I call this the pragmatist frame, since it draws on the pragmatist philosophy of Dewey and James to shift the debate away from developing objective definitions or criteria for when security is good or bad and towards seeking practically useful knowledge about the value of security, which is contingent and context-dependent. Empirically, this lends itself to practice-centred analysis, and here I draw on a wider notion of practice following Emanuel Adler and Vincent Pouliot. Lastly, it brings in contextualism. Contextualist contributions on the meaning of security tell us that security means different things in different contexts, that it doesn’t have an unchanging ‘essence’.Footnote 61 The meaning and the practice of security is contested and produced through ‘a process of negotiation’.Footnote 62 I suggest here that if security is contingent, it cannot be inherently good or bad. Rather, we can only understand the value of security by studying how it works and what it does in different empirical contexts. Bringing pragmatist, practice and contextualist literatures together and into this debate provides an important new lens through which to understand the value of security. While the space to explore the practical implications of this is limited here, the final parts of this section considers how the framework could be used to study the value of security and tackles some of the limitations and questions it raises.

Pragmatism is a philosophical approach drawing on the work of authors like John Dewey and William James. It has grown in popularity in IRFootnote 63 but remains overlooked in debates over security ethics.Footnote 64 A pragmatic approach does not aim to uncover or produce an objective ‘truth’ that is ‘out there’, but rather to gain practically useful knowledge.Footnote 65 Dewey and James are united in emphasising the importance of uncertainty and rejecting settled ‘truths’, ‘fixed principles, closed systems, and pretended absolutes and origins’.Footnote 66 They suggest instead that truth is contingent on context and experience, and never fixed: thus the ‘quest’ for truth is never settled. Molly Cochran refers to this as a ‘weak foundationalism’ allowing contingent ethical claims.Footnote 67 Following this, James emphasises a shift away from first principles towards consequences – a practice or an idea is ‘good’ it has good results, and only for as long as it has good results.Footnote 68 Ultimately, good ideas are ideas that ‘are also helpful in life’s practical struggles’Footnote 69 and the value of a thing depends on what that thing does or leads to in practical terms: what sensations, habits or actions it will produce.Footnote 70 This will in turn vary in different cases and at different times. Dewey also emphasises practice and individual experience as necessary for ethical enquiry.Footnote 71

Pragmatism thus suggests that to understand the value of security, we need to conduct a detailed empirical enquiry to see how different actors use it in different contexts and how individuals experience it, asking what do different security practices do? What actions and habits do they produce, and how do they affect life experiences? While the answers to these questions remain contingent, a pragmatic contingent ethics allows us to suggest alternatives while emphasising reflexivity. We can therefore understand when security is good or bad in a particular situation. Methodologically, pragmatism emphasises abduction and starting at the middle level, instead of starting from abstract theoretical principles or inferring propositions from facts.Footnote 72 In this way, we can analyse when human beings experience security as a ‘good’ (and vice versa). This shifts the discussion away from the abstract potential of security to be ‘good’ or ‘bad’, towards empirical research analysing what it ‘does’ in different contexts.

The way in which pragmatism is used here lends itself to practice-centred analysis. Practice-centred approaches study practices and how they (re)produce particular ideas and realities.Footnote 73 Here I draw on a wider notion of practice following Adler and Pouliot, which fits more logically with pragmatism. Thus ‘practice’ includes discursive practices as well as ideas, power relations, policies, and physical practices undertaken in the name of security.Footnote 74 Vitally, practices are distinguished from behaviour or actions because they are ‘socially meaningful patterns of action’.Footnote 75 A wider understanding of practice allows us to study a range of security practices and processes, including contestation and resistance to dominant security practices. This means that we can study a range of actors beyond elites, while recognising the importance of power. Pragmatism is vague on research methods but practice approaches can provide a clear toolkit for how to study security in a way that is compatible with a pragmatic approach.Footnote 76 It also gives us an empirical starting point: security practices.

Combining pragmatism and the practice turn provides a fruitful way forward for understanding and studying the value of security in context. Here I draw on the contributions of contextualist arguments on the meaning of security, in particular the work of Nils Bubandt, Felix Ciută, and Matt McDonald. Bubandt’s vernacular security draws on anthropological methods to propose ‘a bottom-up, actor-oriented’ analysis of how security is created, which recognises that ‘security is conceptualized and politically practised differently in different places and at different times’.Footnote 77 Ciută argues that while a contextual approach privileges how the actors studied define and practice security, it also ‘engages the contradictions and normative consequences of contextual definitions of security’.Footnote 78 Contextualising the study of security has normative implications. Crucially, if we take it to its logical conclusions, a contextualised and conceptually open study of security necessitates an empirical focus: but if we focus on how actors use security, we may end up ‘foreclosing alternative political horizons’.Footnote 79 Ciută’s answer to this problem stresses understanding normative awareness as inherent to contextualised analysis of security: at the end of the day ‘normative judgements are inherent in the analytical evaluation of the means, ends and consequences of security measures’.Footnote 80 Simply put, we cannot and should not avoid normative judgements when we study security.

For Ciută, a ‘prescriptive observation’ endorsing a particular concept/practice of security because it is considered to be ‘better’, ‘cannot therefore be justified analytically, but only normatively’.Footnote 81 This is an important distinction. He suggests that rather than endorsing a particular version of security from an analytical perspective, which is problematic, the analyst can engage normatively by highlighting ‘the ethical implications of different contextual definitions of security’.Footnote 82 Thus, he stresses a normative awareness as opposed to fixed normative commitments. This has important consequences for understanding the value of security. We can study actors’ different understandings and practices of security and what these do, considering their ethical implications in the context studied. McDonald critiques the traditional focus on the state, suggesting that if we recognise the contextual and contested nature of security we need to study how actors beyond the state use it too – particularly since non-state actors often contest dominant security practices. If we are trying to understand security by studying how security is used, therefore, we cannot justifiably ignore alternative voices. Most importantly, focusing just on the state reifies a particular state-centred logic of security, which is often explicitly rejected by other actors.Footnote 83

So where do we look for security?Footnote 84 I have already suggested security practices as a starting point. Authors used here focus largely on discourse, while this article suggests going beyond that to consider practices more broadly. Thus, at its most basic, we should start by looking at actual security practices in a particular context and asking what they do. I have emphasised the need for detailed empirical enquiry to see how different actors use security in different contexts and how individuals experience it, asking what different security practices do, what actions and habits they produce, and how they affect life experiences. In-depth case studies lend themselves most obviously to such analysis of the value of security. They are also more likely to provide situated and practically useful knowledge. Bubandt’s study of security practices in Indonesia in an excellent example here: he analyses how state and global security notions/structures are contested or absorbed at local levels, and how local notions feed back into both. While the focus in his study is on the meaning of security, the methods could be equally useful for studying its value. An analysis could study global, state and/or non-state security practices, considering both more ‘high profile’ practices with a lot of influence and marginalised or ‘smaller’ everyday security practices.Footnote 85 This necessarily needs to include a consideration of power: where it lies and how this is reproduced. Thus, a contextualised and practice-centred approach to the value of security looks at how different actors understand and practice security and analyses what these different understandings and practices of security do. The following questions may be useful when undertaking such an analysis:

-

∙ Who are the key actors?

-

∙ Who is empowered to practice security and who is not?

-

∙ How do different actors represent security?

-

∙ What practices do they undertake, what do they do?

-

∙ What do they emphasise or call for?

-

∙ What do they want to protect, how, and from what?

-

∙ What does the practice aim to do, and what does it do?

-

∙ What effects do the practices produce?

-

∙ What actions and habits do they produce, and how do they affect life experiences?

-

∙ Are they helpful in daily struggles (the pragmatist test)?

-

∙ Do they protect, enable or constrain referents?

-

∙ What are the ethical implications of the practices studied?

This is not an exhaustive list, but it does provide a starting point. The answers to these questions will vary in different contexts. Which actors/practices are important to study will also depend on the project and case/s studied. We also need to recognise the interconnectedness of security issues.Footnote 86 For example, a security practice may be helpful to the daily struggles of some but produce insecurity for others. Thus, the wider ethical implications of the practices analysed need to be taken into consideration.

We are also left with the normative problem of which actors we choose to study: which practices do we study, whose voices do we listen to, and why? Pragmatism does not give satisfying answers to questions about power: whose daily struggles should practices be helpful to, and who gets to decide if the results of a practice are good? McDonald pursues a normative agenda drawing on emancipation, concerned with ‘locating immanent possibilities for emancipatory change’ by opening space for alternative voices.Footnote 87 While I am sympathetic to this approach, it is worth remembering that alternative is not necessarily ‘better’ in ethical terms: consider right-wing groups using security to advocate for closing EU borders to refugees escaping war, for example. So whom do we listen to and study, and on what basis do we make this decision? In most cases and contexts studied, there will be a range of actors practicing and articulating security. Covering a range of actors will help to capture different ways of practicing security, which will then allow for more depth when we consider the ethical implications of these security practices. This doesn’t mean all studies have to cover all actors: a study could focus on a single state, non-state groups, or one or more international organisation/s: but in each of these there will likely be some contestation, resistance, and disagreement. By analysing how security is contested in different spaces, we also recognise that security is a ‘situated interactive activity’Footnote 88 and needs to be understood, and studied, as such.

To give another example, Ali Bilgic studied security in Tahrir Square, focusing on how protesters experienced and practiced security during one week. He draws on feminist work to rethink emancipation, emphasising how ‘individuals and social groups’ themselves articulate security: ‘that is, their own expressions of how security is understood by them’.Footnote 89 A similar approach could be used to understand the value of different security practices in such a case. Looking at gender, resistance and human security, Hoogensen and Kirsti Stuvøy suggest that ‘the way to understand and to establish knowledge about security in empirical terms is to enter people’s life-worlds and access local experiences of in/securities’.Footnote 90 These examples both emphasise smaller-scale security practices and experiences of security, but studies could equally analyse how different actors within the United Nations practice security within that institutional setting and the value of such practices, for example. My own work has looked at how different actors within the United States and China practice energy security, and the value or ethical implications of different security practices in this context.Footnote 91

The introduction to this article noted the importance of considering the role of the analyst in normative analysis. A pragmatic focus on practice partly removes this problem, by focusing on detailed empirical enquiry as opposed to imposing analytical criteria for what makes particular security practices ‘good’ or ‘bad’. In particular, focusing on individuals’ (or groups) own articulations of security,Footnote 92 and evaluating these normatively. However, we cannot fully avoid normative judgement, which is where Ciută’s emphasis on normative awareness and reflexivity is useful. Reflexivity and positionality requires acknowledging the role of the researcher in the research process and in interpreting the data.Footnote 93 Security analysts are not neutral, and will always arrive with preconceived ideas and opinions about the concept and value of security. This only makes openness about normative commitments more important so these can be recognised and interrogated. The role of the security analyst is always political: the key is ‘to be aware of [and explicit about] the political significance of analysis’.Footnote 94 The normative commitments of the analyst will also likely vary between cases studied in contextual security analysis. For example, in my analyses of energy security practices I emphasise the connections between human wellbeing and environmental security, for the simple reason that without environmentally sustainable energy security practices in the longer term there will be no individual experiences, no human wellbeing to consider, no daily struggles to be helpful to, as the planetary ecosystems on which human survival depend will be destroyed. What is ‘good’ therefore depends on the context and what different security practices do in that context, as well as the analyst. This is why we need to be clear and open about normative commitments. Recognising the subjective and context-dependent nature of the value of security will in turn fuel and push the debate forward instead of getting gridlocked in disputes over the (im)possibility of an objectively defined ‘good’.

However, a pragmatist frame also recognises the need to keep these categories open. So how do we determine what is and isn’t security, and thus which practices to study? The focus here is on analysing how security is used and using this to further understanding of the value of security (see Figure 2). Thus the focus is on studying existing security practices, and what they ‘do’ in different empirical contexts – taking a broad interpretation of ‘practice’. Here I mean specifically practices undertaken in the name of security.Footnote 95 This doesn’t mean security couldn’t be something else, or that there aren’t further things that could or should be secured which currently are not (which is a crucial, but separate, question), but the focus here is on how different existing practices of ‘security’ in empirical contexts can help us understand the value of security. Here, I argue in favour of pluralism and diversity: rather than narrowing down what we mean by ‘security’ to very specific uses or particular (elite) actors, looking at a more diverse range of actors and a more diverse range of meanings of security (beyond survival), serves to illustrate that the value of security depends on the context.

Security studies needs to open up for the possibility that ‘security’ can mean very different things, and that in these cases it is characterised by very different processes and outcomes. Similarly, it is important to view the value of security in non-binary terms. Security is contested: consequently, to understand security it is necessary to study the full range of security constructions – from more problematic and undesirable security practices, to limited practices which secure us from threat, to more emancipatory practices, by a wide range of actors and in a range of empirical contexts, to really interrogate the value of security. In a sense this means accepting the range of existing definitions and approaches to the value of security and studying how they work in practice.

Figure 2 Different uses of negative and positive security.

Conclusion and implications

The value of security matters: both because problematic security practices can do a lot of harm and because ‘good’ or ‘positive’ security practices can help us advance towards the kind of world that we want. But the current debate over the value of security causes confusion. This article has clarified the debate by separating out two different ‘frames’ used by key authors. The analytic frame draws on positive/negative liberty and peace, and thus defines negative security as the absence of threat, and positive security as added enabling possibilities beyond survival: here positive and negative security work together. The normative frame uses value judgements and deploys the terms positive and negative in a normative sense, often drawing on securitisation theory. Consequently, this frame suggests that negative security is bad and to be avoided, while positive security is desirable. These frames have their roots in different literatures and although both theorise the value of security they look at different aspects, leading to somewhat different research agendas. This causes confusion and has stalled the debate.

This article has argued that the value of security depends on how it is used and what it does in different empirical contexts, developing a pragmatic framework for understanding the value of security in context (see Figure 2). This approach allows us to recognise that security can be bad, but that it can also be something worth striving for, while avoiding imposing abstract theoretical definitions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Mike Bourne and Dan Bulley suggest abandoning attempts to establish secure ethics, arguing that we should instead be ‘treating moral choice as explicitly unsure, uncertain and insecure’.Footnote 96 Accepting this, a pragmatist frame helps us move forward with a practical research agenda that avoids defining the ‘good’ in theoretical terms while allowing us to evaluate the normative implications of different existing security practices in a particular context. Thus the article opens space for empirically grounded research on the value of security.

The article focuses on clarifying the existing debate and suggesting an alternative, so it presents a conceptual analysis rather than an empirical application. There is therefore much potential for future research on the value of security in different contexts. Beyond this, two problems not addressed by this framework come to mind as possibilities for future research. Firstly, what about cases where some experience security as a good, but others do not? The ongoing debate over the surveillance society provides an excellent example: some experience surveillance as reassuring, while others find it an imposition on their freedom to go about their daily lives unwatched. In such cases the role of the analyst becomes much more complicated and needs to be considered in more depth. Secondly, what about those who cannot practice security? This framework is merely intended to understand the value of different existing security practices. More research is needed into the silences and gaps this creates, as it overlooks those who cannot speak or practice security but may be deeply affected by insecurity, whether this be silenced or marginalised groups or non-human elements in need of protection, such as local or global ecosystems. This article has clarified the debate over the value of security and suggested a new framework for analysing it in context, but while it pushes the debate forward it also raises new questions. Security is powerful and contains potential for harm as well as ethical progress. But ultimately, understanding the value of security is crucial in order to move towards the kind of world that we want.

Acknowledgements

This article has evolved through several drafts, and many people have kindly read it and provided helpful comments at different stages. I thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive and helpful feedback throughout the submission process. Andrew Neal, Matt McDonald, Lene Hansen, Anthony Burke, Kacper Szulecki, and Olaf Corry have all provided valuable comments on earlier drafts. Thanks also to Adam Quinn, Rita Floyd, and Liam Stanley for helping me to figure out what I wanted to say.