The two most common words used by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI) activist respondents to describe their experience of working in the movement are “rewarding” and “empowering.” Yet working as an activist in the LGBTQI movement can be extremely difficult, with great personal cost. The next most common descriptors were “challenging,” “frustrating,” and “exhausting.” Understanding how the pressures of activism impact activists is a critical question for gender studies, public policy, social movement studies, and the social sciences more broadly. We investigated the following research question: What are the emotional costs for LGBTQI activists in the United States, United Kingdom, South Africa, and Australia? These countries were selected because each has a contemporary LGBTQI history, allows for the organization of activists, and has responsive liberal state institutions. Each of these countries has evolved regarding LGBTQI rights. Although some have been more accepting than others with regard to bisexual, transgender, and intersex identities, the acronym LGBTQI is broadly used as an umbrella recognition that each identity in the activist community plays a role.

In Australia, the Australian First Peoples engaged in “homosexual practices” (Baylis Reference Baylis2015, 6). The colonial invasion of Australia 1788 set the laws that would govern homosexuality and gender for nearly 100 years. In 1970, the Daughters of Bilitis started as a lesbian group as did the Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP), demonstrating the earliest organization of LGBTQI activists there (Moore Reference Moore1995, 319). In response to organized groups such as these, laws began to change. Military service was legalized in 1992 (Rimmerman Reference Rimmerman1996, 21), and sodomy was illegal until 1997, when it was overturned following a decision by the United Nations Human Rights Committee (Berman Reference Berman2008). Same-sex marriage was legalized in Australia in 2017 (McAllister and Snagovsky Reference McAllister and Snagovsky2018).

In the United Kingdom, the Homosexual Law Reform Society was formed in 1958 to advocate for the legalization of homosexuality (Davidson and Davis Reference Davidson and Davis2004). In 1963, the Minorities Research Group was formed for lesbians to add research to the debate about homosexuality in the media (Hopkins Reference Hopkins1969, 1434). The Campaign for Homosexuality Equality followed in 1964 (Kent City Council 2011), and Stonewall UK was formed in 1989 to lobby against unfair laws (Barker et al. Reference Barker, Richards, Jones and Monro2011). In 2000, the United Kingdom lifted the ban on homosexuals in military service (Helfer and Voeten Reference Helfer and Voeten2014), and same-sex marriage was legalized in England and Wales in 2014 (Eekelaar Reference Eekelaar2014).

In the United States, the Society for Human Rights in Chicago, the first LGBTQI group, formed in 1924 (Kepner and Murray Reference Kepner, Murray and Bullough2002, 25), followed by the Mattachine Society in 1951 (Adam Reference Adam1995, 67), which organized protests. The Gay Activists Alliance of New York formed in the 1969, following the Stonewall riots (Armstrong Reference Armstrong2002, 87). Activism around human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) in 1987 also led to the founding of ACT UP (Gould Reference Haider-Markel, Taylor and Ball2009, 129). Laws began changing after the 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision decriminalized sodomy. These changes were followed in 2011 with the repeal of the ban on gay, lesbian, and bisexual service in the military (Neff and Edgell Reference Neff and Edgell Blas2013, 233). Marriage equality was granted in 2015 (Faderman Reference Faderman2015, 635).

In South Africa, LGBTQI groups formed in the 1970s and 1980s along racial or ethnic lines. The downfall of apartheid accompanied an increase in rights for LGBTQI people. In 1996, South Africa's constitution guaranteed the right to nondiscrimination to the LGBTQI community (Currier Reference Currier2010). In addition, the government allowed service in the military in 1996 regardless of sexual orientation (Cock Reference Cock2003). Sodomy was decriminalized in 1998 and gay marriage was legalized in 2006 (Currier Reference Currier2012). In terms of NGOs, the Lesbian and Gay Equality Project was founded in 1994. Notably, however, in South Africa, a level of violence against transgender people remains. A 2016 survey by the Other Foundation found that “About half a million (450,000) South Africans over the prior 12 months, have physically harmed women who dressed and behaved like men in public, and 240,000 have beaten up men who dressed and behaved like women” (7).

Our hypothesis builds on the intersectionality literature (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Hill Collins and Bilge Reference Hill Collins, Sirma, Collins and Bilge2016) to analyze the survey results from these countries.

H 1:

People from multiple minority groups experience greater emotional costs and burdens imposed on them for their engagement in the policy process than those with more positively constructed identities.

We rely on the concept of emotional taxation, which Neff (Reference Neff2016) defines as follows: “Emotional taxation or the taxation of emotions is the emotional cost, intentional or not, that a policy, program, or scheme places on an individual or group for entering into the political process or addressing a political issue.”

Emotional taxation is the emotional cost for engaging in the political process (Pepin-Neff and Caporale Reference Pepin-Neff and Caporale2018). It functions as an agenda-setting and mobilization concept because the level of taxation imposed on an individual or group can push them toward or inhibit them from political action. It is relative to power, capacity, and collective support, which means that socially constructed identities with greater power may experience less emotional taxation and may have more capacity to bear the costs of political engagement. This stress may lessen with the support of others.

H 2:

Political power of a target population is consistent with Schneider and Ingram's ( Reference Schneider and Ingram1993) analysis on hierarchies of identity and includes the way benefits and burdens are distributed to groups based on power and identity.

The variability of capacity of emotional taxation extends from the theory of emotional labor (Hochschild Reference Hochschild1983) defined as labor that “requires one to induce or suppress feelings in order to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others” (7). According to this theory, emotions are a resource that can be tapped. The individual's capacity to “pay the cost” is a function that may be hindered by oppression, discrimination, or other socially or physically debilitating conditions, connected by structural inequity (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Lang Reference Lang2000). The lack of capacity to absorb the burden makes the experience of the level of taxation higher, whereas the abundance of capacity lowers emotional taxation. As a result, activists may design less taxing activities or issue agendas. Alternatively, activism on high-taxation issues or tactics may produce burnout and/or force activists to leave the movement altogether. Collective support can also affect levels of emotional taxation in a variety of ways. It can reduce taxation when support from others lessens the degree of individual vulnerability. This may also be the case if the mobilization of others determines whether someone is initiating or following the actions within the political process. In summary, being singled out creates a more vulnerable situation and implies a higher level of emotional taxation.

The emotional taxation concept extends the work on emotional habitus by Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1977) and others. An emotional habitus is the connection between emotions and policy issues that defines the norms and the political trajectory of an issue for a community. For instance, Gould (Reference Haider-Markel, Taylor and Ball2009) looks at the role that emotional habitus plays in defining the political possibilities around HIV/AIDS. She argues that the 1986 Supreme Court decision Bowers v. Hardwick, which denied LGBTQI people any rights under the constitution, created a rupture that changed the issue of AIDS. What began as an emotional narrative of desperation toward a fatal medical condition shifted into a story in which gay men were being assassinated by the judicial and political process on the basis of their identity.

The concept of emotional taxation is also consistent with the way emotional stimuli are discussed in the agenda-setting literature, which includes theories of the policy process, crisis management, and behavioral public policy. For instance, in research on multiple streams theory, Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1984) notes the importance of public mood and Zahariadis (Reference Zahariadis2007) postulates the way emotive features may be used to manipulate actors. Policy entrepreneurs use public attraction to certain emotional issues to advance their issues in the agenda and influence policy outputs (Mintrom Reference Mintrom2000; Pepin-Neff and Caporale Reference Pepin-Neff and Caporale2018).

The advocacy coalition framework (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith Reference Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith1988) also recognizes the role of “devil shift” (Sabatier et al. Reference Sabatier and Pelkey1987) in motivating actors, in which extremely negative feelings about an opponent infiltrate an organization's way of thinking and operating. Understanding these motivations is important because of the potential for abuse in the political system. Sabatier et al. (Reference Sabatier and Pelkey1987) state, “Devil shift has all the worst features of a positive feedback loop: the more one views opponents as malevolent and very powerful, the more likely one is to resort to questionable measures to preserve one's interests” (471). In addition, punctuated equilibrium theory (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993) makes a key underlying contribution as a theory of information processing. It focuses on attentiveness, which is impacted by emotionality and influences the policy image. As True, Jones, and Baumgartner (Reference True, Jones, Baumgartner, Sabatier and Boulder2007) state, “Policy images are a mixture of empirical information and emotive appeals” (161).

Overall, emotional taxes are organized in institutions, structures, political groups, and socially recognized hierarchies of identity to confer emotional rewards upon politically preferred groups and emotional burdens upon stigmatized groups.

H 3:

Drawing on intersectionality literature, we expect that being a member of multiple minority groups has compounding effects.

We tested this hypothesis through a comparative analysis of emotional taxation rates within and between groups. In the remainder of this article, we describe our methodology and present the results of our survey. We discuss key findings and explain why these questions and results matter. We conclude with policy suggestions and future research.

EMOTIONS IN PUBLIC POLICY

This research regarding the lived experience of LGBTQI people has been conducted at a time of heightened emotional stakes for the LGBTQI community. Following victories regarding marriage equality (Ball Reference Carlos2016), significant gaps in equity for LGBTQI people remain in the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Australia. For instance, transgender people of color remain subject to high rates of violence and murder. Youth homelessness and youth suicide remain at epidemic levels, and religious exemptions (Haider-Markel and Taylor Reference Helfer and Voeten2016, 46) threaten workplace employment, housing, and commerce. Additionally, restrictions on “safe schools” programs to combat bullying are still provocative issues in many locations.

Furthermore, we believe that “groups within groups” deserve important attention in the political science literature. Resources are directed in heteronormative and homonormative ways toward issues that favor white, cisgender-male, and gay identities. One example is the way funds have been directed toward marriage equality in the United States. This issue is a luxury item for elites when compared to LGBTQI issues of homelessness, youth suicide, domestic violence, or senior isolation. Moreover, Gorski (Reference Gorski2018, 13) posits that intergroup conflict is the leading contributor to activist burnout.

This study adds quantitative data and analysis to considerations of burnout, minority stress, and intersectionality (see, e.g., Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Srivastava Reference Srivastava2006). For instance, Herman (Reference Herman2013) builds on Meyer's (Reference Meyer1995, Reference Meyer2003) model of minority stress for LGB people. Meyer (Reference Meyer1995) states, “Psychosocial stress derived from minority status” functions on the basis that “gay people, like members of other minority groups, are subjected to chronic stress related to their stigmatization” (699). Herman (Reference Herman2013) extends this analysis to the transgender population, stating that “Transgender and gender nonconforming people across the United States certainly are suffering the negative impacts and consequences of distal and proximal minority stressors” (66). Indeed, the effect of directing policies that impose an emotional tax on an already oppressed target population suggests a disproportionate impact (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). Our findings are consistent with the literature on intersectionality and the way oppressed groups with multiple marginalized identities experience acute discrimination at the intersection of those identities (see Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Pepin-Neff and Caporale Reference Pepin-Neff and Caporale2018). Fundamentally, structural and hierarchical systems render these identities vulnerable.

The utility of emotional taxation is that it allows for the interrogation of the role of emotions in social movements, interest groups, lobbying, political engagement, and other political sites of power. Marcus (Reference Marcus2000) states, “A consensus on the effects of emotion in politics remains to be achieved” (222). Incorporating emotional taxation relates not only to the literature on capacity (Lang Reference Lang2000) but also to burnout (Chen and Gorski Reference Chen and Gorski2015; Gorski Reference Gorski2018; Pines Reference Pines1994). The issue of burnout is particularly important for political activism because it involves both physical and mental stressors for long-term activists.

Pines (Reference Pines1994) notes that for people who choose political activism, “The stakes involved are very high because they are trying to derive from their work or political involvement a sense of meaning for their entire life” (390). To analyze potential burnout, “interviewers inquired about the most pressing mental health problem experienced by members of the protest movement” (ibid.). These stressors can come from external influences as well as internal ones. For Gorski (Reference Gorski2018), internal conflicts present the greatest threat to burnout within the racial justice movement: “All 30 participants attributed their burnout to how activists treat one another. Many became worn down attempting to navigate activist communities in which in-fighting and ego clashes were commonplace” (679). In their study of 1990s peace activists, Maslach and Gomes (Reference Maslach and Gomes2006) found that “relationships with other activists” were the most fulfilling, but they were also the most stressful in their activist work (47).

In the present study, we built on this research by asking activists about their mental health experience as a component of emotional taxation. Although emotions are a resource, they do not follow a simple cost–benefit calculation. A given degree of emotionality relative to available capacity is not always predictive of a level of individual or collective engagement. Sometimes there is no cost a person or group is unwilling to bear to advance their social and political aims.

METHODOLOGY

Recruitment

In this study, we employed a 37-question survey using Qualtrics software. Facebook advertisements were used as the distribution mechanism for the survey link. The Facebook advertisement was titled “2017 LGBTQI Activist Survey,” and it targeted people 18–65+ years of age. As stated, “The goal of the survey is to look at the feelings and perceptions of those on the front-line of the movement.” We sought to restrict the sample to the population of interest—LGBTQI activists. As Meyer and Wilson (Reference Meyer and Wilson2009) state, “Investigators wishing to study LGB populations must … devote significant energy and resources to choosing a sampling approach and executing the sampling plan,” and historically, “to obtain larger samples of LGBs while reducing the cost of probability sampling, researchers have targeted geographic areas with greater density of LGBs (‘gay neighborhoods’)” (23). Figure 1 illustrates the recruitment selection criteria for the advertisement, which included search terms consistent with online neighborhoods of LGBTQI activism: “gay pride,” “rainbow flag,” “same-sex marriage,” “coming out,” “LGBT community center,” “GLBT straight alliance,” and “support gay rights.”

Figure 1. Target recruitment.

Respondents were part of a digital convenience sample in which participants volunteered to complete the survey. Thus, caution should be taken in generalizing the findings to the broader LGBTQI activist community. However, despite this limitation, such concerns about the data are substantially allayed by their consistency across international locations. Regarding online surveys, Eysenbach (Reference Eysenbach2004) notes, “Bias can result from (a) the nonrepresentative nature of the Internet population and (b) the self-selection of participants (volunteer effect)” (e34). However, online sampling “can also facilitate access to individuals who are difficult to reach either because they are hard to identify, locate, or perhaps exist in such small numbers that probability-based sampling would be unlikely to reach them in sufficient numbers” (Fricker Reference Fricker, Fielding, Lee and Blank2008, 17). Data collection within the LGBTQI community is notoriously difficult, and the use of Facebook for purposive sampling has become commonplace in social science research (Ramo and Prochaska Reference Ramo and Prochaska2012; Van Selm and Jankowski Reference Van Selm and Jankowski2006, 435).

This method is consistent with a number of LGBTQI surveys. The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights research (FRA, 2012) used an online survey of self-reported LGBT respondents across the European Union and Croatia. The anonymous online questionnaire collected data from 93,079 persons aged 18 years or over who self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender regarding their views, perceptions, opinions, and experiences. “In total, 17,839 visitors to the EU LGBT survey website came directly from the Facebook domain, and 10,456 user sessions resulting in completed interviews arrived from Facebook (that is, some visitors did not proceed beyond the front page of the survey to the questionnaire). With this, Facebook was the survey's single most important referrer.” (FRA, 2012, 42). In addition, Dane et al. (Reference Dane, Short and Healy2016) surveyed the Irish LGBT community following the 2015 Thirty-Fourth Amendment of the Constitution Act, which established marriage equality. In part, the online survey also used Qualtrics and Facebook to distribute the survey to self-identified members of the queer community. Specific research into the transgender community has also been conducted. James et al. (Reference James, Herman., Rankin., Keisling., Mottet and Anafi2016) administered a survey of the transgender community in the United States. They note the difficulty in conducting this type of research: “The survey was produced and distributed in an online-only format after a determination that it would not be feasible to offer it in paper format due to the length and the complexity of the skip logic required to move through the questionnaire” (25).

Measures

Overall emotional taxation was measured with four items: (a) “Do you think it is emotionally taxing or personally intense (to a cost) working in the LGBTQI movement?” (yes, maybe, or no); (b) “On a scale of 0–10, how emotionally difficult is it for you working in the LGBTQI movement?” (0–10); (c) “To what extent would you agree that working in the LGBTQI movement has impacted your mental health?” (1–7; strongly agree to strongly disagree); (d) “On a scale of 0–10 (10 being most negative) how has working in the LGBTQI movement affected your mental health?” The latter three items were scaled and centered for comparability, then were used to create the emotional taxation scale. Although it is reliable at conventional levels (Cronbach's α = 0.78), this study marks its first deployment, and further research should be conducted to validate and optimize this scale.

Task-specific emotional taxation was measured with a 10-point scale accompanied by the prompt, “How emotionally taxed are you when doing the following tasks?” Categories included marching in a parade, handing out flyers to the public, lobbying legislators, tweeting (i.e., posting on Twitter), posting on Facebook, organizing an event, leading a protest action, and self-expression of identity through clothes, ink, hair, and makeup. Preceding the question, emotional taxation was defined as “the emotional cost, intentional or not, that a policy, program, or scheme places on an individual or group for entering into the political process or addressing a political issue.”

Issue-specific emotional taxation was measured with a 10-point scale asking respondents to rate “the way different issues place emotional burdens on you personally.” These categories included marriage equality, workplace discrimination, openly LGBTQI military service, youth homelessness, LGBTQI senior care, and LGBTQI mental health.

Participants

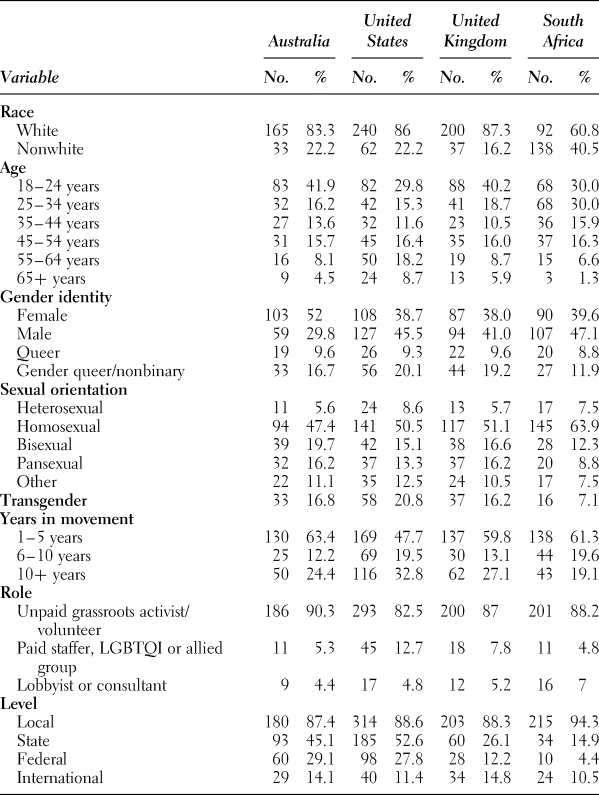

The survey was completed by 1,019 LGBTQI activists in the United States (n = 355), the United Kingdom (n = 230), South Africa (n = 228), and Australia (n = 206) between May 9 and May 16, 2017. The respondents were asked a range of demographic questions including age, sexual orientation, and gender identity. A question on race was also included. Although Australian survey research generally employs the Australian Standard Classification of Cultural and Ethnic Groups (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016), questions on race are commonplace in the United States and South Africa, where most respondents in the broader study were located. This question was included for all respondents in the interests of cross-national comparison. Questions about activist behavior, such as their role(s) and years of involvement, were also included. Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of respondent characteristics.

Table 1. Demographics and activist characteristics

*Percentages exclude nonresponse; race, role, gender, and level allow multiple answers.

Survey respondents who identified as female made up 52% of the respondents in Australia, 38.7% in the United States, 38% in the United Kingdom, and 39.6% in South Africa (Table 1). Fewer survey respondents identified as male in Australia (29.8% of the respondents in Australia), but more identified as male than as female in the United States (45.5%), the United Kingdom (41%), and South Africa (47.1%). Respondents who identified as queer accounted for 9.6% of respondents in Australia, 9.3% in the United States, 9.6% in the United Kingdom, and 8.8% in South Africa. However, greater percentages of respondents identified as gender queer/nonbinary in Australia (16.7%), in the United States (20.1%), in the United Kingdom (19.2%), and in South Africa (11.9%).

In each of the four studied countries, most survey respondents were aged 18–34 years: 58.1% of respondents in Australia, 45.1% in the United States, 58.9% in the United Kingdom, and 60% in South Africa. Survey participants who identified as transgender comprised 16.8% of the cohort in Australia, 20.8% in the United States, 16.2% in the United Kingdom, but only 7.1% in South Africa. In each of the four countries, most of the respondents reported their sexual orientation as homosexual: 47.4% in Australia, 50.5% in the United States, 51.1% in the United Kingdom, and 63.9% in South Africa. The next most commonly indicated identity was bisexual, which was indicated by 19.7% of respondents in Australia, 15.1% in the United States, 16.6% in the United Kingdom, and 12.3% in South Africa. The third most commonly indicated identity was pansexual, which was indicated by 16.2% of respondents in Australia, 13.3% in the United States, 16.2% in the United Kingdom, and 8.8% in South Africa. Survey respondents who identified as heterosexual comprised 5.6% of the respondents in Australia, 8.6% in the United States, 5.7% in the United Kingdom, and 7.5% in South Africa.

Respondents were asked how many years they had been in the LGBTQI movement. The most frequent response was “1–5 years”: 63.4% of respondents in Australia, 47.7% in the United States, 59.8% in the United Kingdom, and 61.3% in South Africa. Those who responded “6–10 years” comprised 12.2% of the respondents in Australia, 19.5% in the United States, 13.1% in the United Kingdom, and 19.6% in South Africa. Those who responded “10+ years” comprised 24.4% of the respondents in Australia, 32.8% in the United States, 27.1% in the United Kingdom, and 19.1% in South Africa.

RESULTS

Consistent with our expectations informed by the literature, more than five times as many respondents (n = 557) agreed that their involvement in the LGBTQI movement is emotionally taxing than disagreed (n = 105). Among transgender respondents, the agree/disagree ratio was more than eight to one. As shown Figure 2, compared to cisgender activists, transgender activists experienced higher levels of emotional taxation: F(899, 1) = 11.6 (p < 0.01). They also reported a greater impact upon their mental health: F(927, 1) = 27.1 (p < 0.01). Similarly, nonwhite activists reported higher levels of emotional taxation than white activists: F(900, 1) = 8.0 (p < 0.01). However, this level was not quite significantly higher when mental health impacts were considered: F(928, 1) = 2.0 (p = 0.15). Younger activists (less than 35 years old) also reported significantly higher levels of emotional taxation than older activists (more than 35 years old): F(900, 1) = 5.3 (p < 0.05). Younger activists also reported much greater mental health impacts: F(928, 1) = 22.0 (p < 0.01).

Figure 2. Age, race, and gender identity.

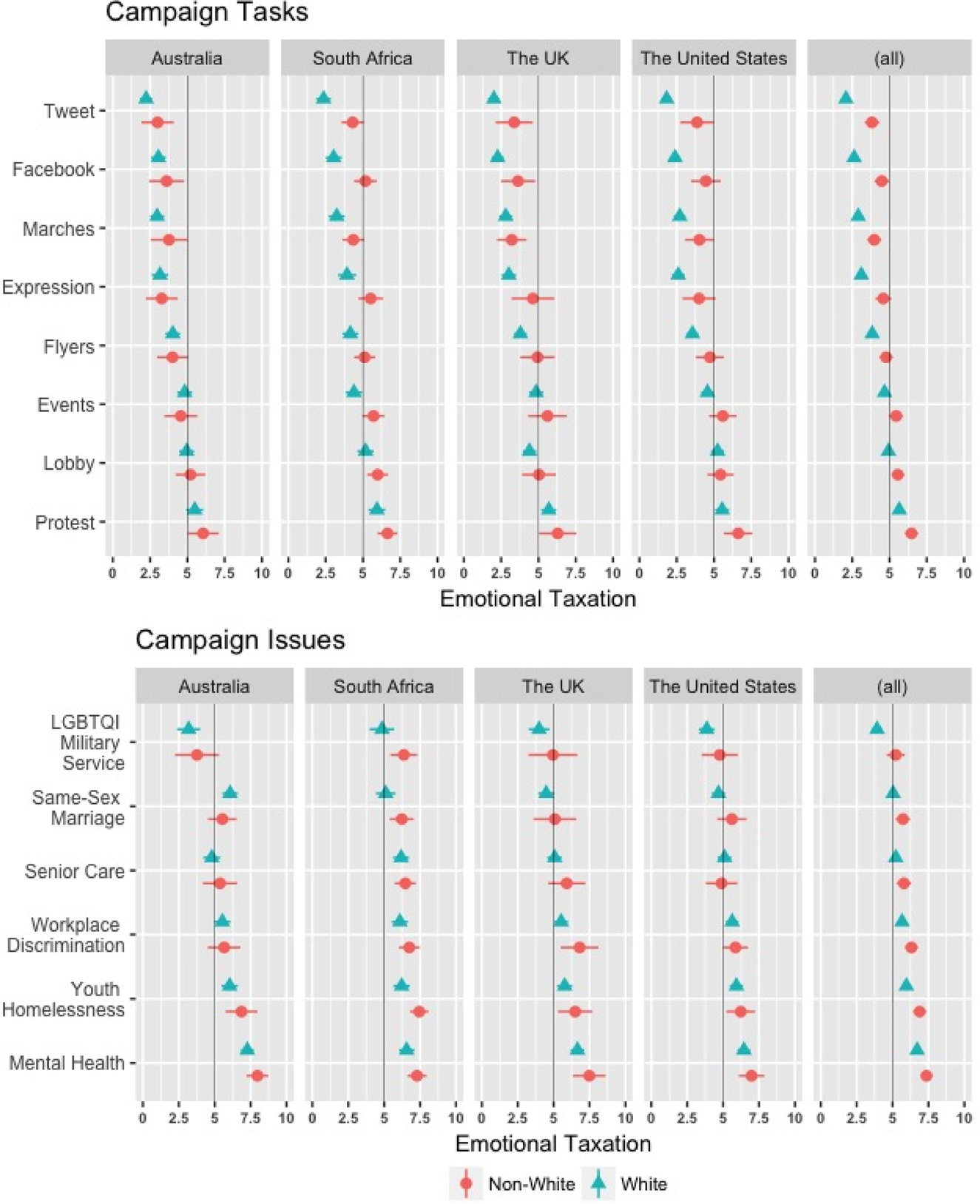

Figure 3 shows the emotional burden associated with a range of campaign tasks and issue areas broken down by country and age. The tasks included tweeting, posting on Facebook, attending marches, expressing identity, posting flyers, organizing events, lobbying, and participating in a protest. Consistent with Figure 2, the data show that LGBTQI younger activists experienced emotional taxation at a higher rate than older activists in every country for nearly all campaign tasks and issues. Only the issue of senior care in Australia, South Africa, and the United States, lobbying in the United Kingdom, and tweeting in the United States imposed greater emotional taxation on older activists. Among respondents of all ages, younger activists reported significantly higher levels of emotional taxation related to the following issues: LGBTQI military service: F(434, 1) = 16.3 (p < 0.01); same-sex marriage: F(687, 1) = 13.1 (p < 0.01); workplace discrimination: F(753, 1) = 21.0 (p < 0.01); youth homelessness: F(666, 1) = 34.6 (p < 0.01); and mental health: F(786, 1) = 71.4 (p < 0.01). However, the high level of emotional taxation did not extend to senior care [F(609, 1) = 1.9 (p = 0.17)]. Older respondents reported lesser effects related to issues. Younger activists also reported significantly higher levels of emotional taxation related to the following tasks: event organization: F(808, 1) = 5.4 (p < 0.05); personal expression: F(783, 1) = 14.8 (p < 0.01); posting on Facebook: F(781, 1) = 8.2 (p < 0.01); posting flyers: F(826, 1) = 6.7 (p < 0.01); lobbying: F(805, 1) = 5.1 (p < 0.05); and protesting: F(794, 1) = 8.1 (p < 0.01). Interestingly, the high level of emotional taxation did not extend to marches [F(805, 1) = 3.7 (p = 0.56)] or tweeting [F(721, 1) = 2.7 (p = 0.1)].

Figure 3. Age.

Race also appears to play an important role in the emotional burdens of activists (Figure 4). Conversely to the age dynamic, however, the differences were substantially greater with regard to campaign tasks compared to issues. Among all respondents, nonwhite activists reported significantly higher levels of emotional taxation on every issue: LGBTQI military service: F(434, 1) = 13.5 (p < 0.01); same-sex marriage: F(687, 1) = 5.6 (p < 0.05); workplace discrimination: F(753, 1) = 6.5 (p < 0.05); youth homelessness: F(666, 1) = 12.4 (p < 0.01); senior care: F(609, 1) = 4.2 (p < 0.05); and mental health: F(786, 1) = 7.3 (p < 0.01). Although nonwhite activists again reported significantly higher levels of emotional taxation on every task-related item, large differences were observed among tasks. The emotional effects related to several tasks were modest: event organization F(808, 1) = 8.1 (p < 0.01); lobbying: F(805, 1) = 5.8 (p < 0.05); protests: F(794, 1) = 9.6 (p < 0.01); and posting flyers: F(826, 1) = 14.6 (p < 0.01). However, these effects were moderately large for marches [F(805, 1) = 22.0 (p < 0.01)] and self-expression [F(783, 1) = 29.3 (p < 0.01)]. For online forms of activism, emotional taxation effects were extremely large: posting on Facebook: F(781, 1) = 58.9 (p < 0.01) and tweeting: F(721, 1) = 57.4 (p < 0.01).

Figure 4. Race by country.

The dynamics related to the differences between cisgender and transgender experiences of LGBTQI campaign issues and tasks are more complex. Relatively little variation was observed related to issues, but with regard to tasks, gender identity interacted profoundly with race (Figure 5). However, in direct comparison, transgender activists experienced significantly higher levels of emotional taxation from engagement in public tasksFootnote 1 than cisgender activists: F(665,1) = 6.4 (p < 0.05). The difference for online tasks (e.g., posting on Facebook or tweeting) was not significant. When considered with an intersectional perspective by gender and race, no significant difference between the cisgender-white and transgender-white subsamples remained. However, taking a conservative approach and applying the Bonferroni post hoc correction for type I error inflation resulting from multiple comparisons, strong and significant differences (p < 0.01) remained between both the cisgender-nonwhite subgroup and both white subgroups, as well as between the transgender-nonwhite subgroup and all three other subgroups.

Figure 5. Intersectional analysis of issues and tasks.

The intersectional analysis of the scale formed from the combined emotional taxation and mental health measures (Figure 5) shows the expected result, with emotional taxation increasing with marginalization. This result confirms Hypothesis 1. Importantly, although there is an approximately 0.6 standard deviation (SD) penalty associated with being nonwhite and a 1 SD penalty for being noncisgender, the penalty for being nonwhite and noncisgender is 1.9 SD, which is a penalty greater than the sum of the component penalties.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study yield profound data for our understanding of social movement organizing, lobbying, and agenda setting. If some issues and tasks are more costly to personally mobilize around, then some activists are attracted while others are pushed away. Thus, emotional taxation may act as a filter that determines not only who engages but also what they engage with. Also, groups within groups report very different experiences of activism; thus, the activist space requires greater examination. For instance, we argue that the age, race, and gender identity of activists could be powerful mediating factors on the selection of issues and tactics for a social movement because disproportionate emotional costs are levied on these groups. This is especially true at the intersections of these identities, which render them more vulnerable (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Pepin-Neff and Caporale Reference Pepin-Neff and Caporale2018). Indeed, activist campaigns with the best of intentions do not present an equal playing field for all. In turn, the direction of social movements and lobbying campaigns is influenced by the people who show up repeatedly. Although there may be little to no cost for some, others report a heavy emotional burden. This inequity biases both the makeup of community mobilizations and which issues attract the energy needed to mobilize collective action.

This research is also important because accusations have been levelled that the LGBTQI movement is overwhelmingly white and based on overt and latent racism. This study was not designed to identify racism; however, the literature makes clear racism exists in the LGBTQI movement. Our data provide evidence for Hypothesis 2, that the makeup of the LGBTQI activist community is produced by hierarchies of marginalization in which inequities in emotional taxation create structural disincentives for minority participation in LGBTQI activism. Thus, activism is not the democratic institution in which anyone can choose to battle the status quo while facing the same penalties and burdens as other activists. Instead, all movements have different costs for participation, and certain issues and tactics place acute emotional costs on certain populations. The LGBTQI community reflects these differences.

As expected, the data demonstrate that LGBTQI activists in the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Australia all experience high levels of emotional taxation (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, the estimates detailed above may be overly conservative if, as we suspect, extreme levels of emotional taxation and stress cause activists to burn out and/or leave the movement. We find systematic evidence that marginalized communities experience greater rates of emotional taxation. Furthermore, members of multiple marginalized communities experienced disproportionately higher emotional costs. These findings confirm Hypothesis 3. Although it is often treated homogeneously, the LGBTQI activist community is really a community of subcommunities, each of which faces different challenges. In addition, subpopulations within those subcommunities face challenges that compound their burdens (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Emotional taxation scale.

If more marginalized groups face higher levels of emotional taxation, then an avoidance response may result, which could manifest in a cisgender-whitewashed agenda-setting effect. If this process biases what movements focus on and who focuses on them, the movement becomes more cisgender-white not only compositionally but also in terms of its political agenda. Consequently, marginalized groups and their political interests are marginalized both outside and inside the LGBTQI movement that represents them, creating a feedback loop in which LGBTQI activism is both more difficult for marginalized activists and disproportionately less representative of their interests. Importantly, the data illustrate the kinds of political activities and issues that impose greater emotional taxation on more marginalized groups. These underlying dynamics may affect the way campaigns are run and the types of issues that are selected. Indeed, activities that attract collective support, such as protests, may still render the participants vulnerable to persecution. Activist organizers need to recognize that not all activists experience the emotional costs of participation equally, and they should take care to protect marginalized activists from disproportionate emotional stress to the extent possible.

The evidence presented here clearly demonstrates that activists working against structures of oppression are by no means immune from paying an emotional cost for their efforts. Indeed, the degree to which they are affected reflects the degree to which the identities that they inhabit are penalized. “Discrimination can be compounded by multiple stigmas,” including race (Bockting et al. Reference Bockting, Miner, Romine, Hamilton and Coleman2013, 943). As demonstrated by the results presented in Figure 5, treating transgender and cisgender activists as homogeneous groups may obfuscate important intersectional dynamics. These data affirm the theory of intersectionality (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991) and highlight the fact that people with multiple marginalized identities have different experiences of LGBTQI activism than white and cisgender respondents.

Figure 5 reveals a number of important dynamics within the data. As hypothesized, marginalized groups within the LGBTQI movement consistently demonstrate the highest levels of emotional taxation and bear the greatest mental health costs (Hypothesis 1). Specifically, emotional burdens were systematically greater for young, nonwhite, and transgender activists. Moreover, online activism was a great deal more stressful for nonwhite activists than for white activists. Given the well-documented hostility toward racial and ethnic minorities on social media, this is not altogether surprising; however, the magnitude is remarkable—more than half a standard deviation for both tweeting and posting on Facebook. This finding suggests that as the digital revolution continues, attention should be given to the emotional impact on marginalized communities, whose members may experience emotional impacts as severe as those related to other, better-established forms of activist engagement (see, e.g., Constanza-Chock Reference Costanza-Chock2010; Jenzen Reference Jenzen2015; Krutzsch, Reference Krutzsch2014; Lievrouw and Livingstone Reference Lievrouw, Livingstone, Lievrouw and Livingstone2010).

Furthermore, sources of emotional taxation vary greatly among activists. Transgender activists were particularly stressed by public engagements such as major events and marches. Although transgender respondents appeared to experience no greater burden from private activism (i.e., posting flyers and lobbying) and online (i.e., tweeting and posting on Facebook) activism, the emotional burden of public activism (i.e., self-expression, marches, protest, and events) was significantly greater for transgender activists than for cisgender activists: F(665, 1) = 6.4 (p < 0.05). This finding agrees with the minority stress model: “The stress associated with stigma, prejudice, and discrimination will increase rates of psychological distress in the transgender population” through processes that are both “external—consisting of actual experiences of rejection and discrimination (enacted stigma)” and “internal, such as perceived rejection and expectations of being stereotyped or discriminated against (felt stigma)” (Bockting et al. Reference Bockting, Miner, Romine, Hamilton and Coleman2013, 943). Hence, public activism involves complex internal and external processes associated with “hiding minority status and identity for fear of harm (concealment)” (Bockting et al. Reference Bockting, Miner, Romine, Hamilton and Coleman2013, 943), which manifests in identity suppression and/or emotional stress.

This situation is compounded when we consider the infighting and erasure that can exist within the LGBTQI movement (Ghaziani Reference Ghaziani2008). Murib (Reference Murib2017) notes that “In many cases, the privileging of sexual orientation (i.e., lesbian and gay political identities and political interests) entailed silencing the political agendas for transgender and bisexual-identified people, as well as butches, fairies, cross dressers, queer people of color, and intersex-identified people, who also compromised the margins of the new ‘GLBT’ identity” (20–21). As a result, difficult external situations are made more perilous internally as the broader marginalized LGBTQI community takes actions that further marginalize less powerful members within that group. This phenomenon was empirically validated by our data. We asked respondents to indicate the most significant obstacles to LGBTQI progress: “What would you say are the biggest obstacles to winning LGBTQI equality?” Respondents from every country nominated allies (i.e., equality groups and non-LGBTQI progressive groups) over enemies (i.e., anti-LGBTQI religious groups and opponents) at a rates of 62% versus 38%, respectively.

Finally, some important differences between the countries were revealed. For instance, few respondents in South Africa identified as transgender (7%). This finding may have resulted from continuing violence (as noted), but it was incongruent with respondents from Australia (16.8%), the United States (20.8%), and the United Kingdom (16.2%). In addition, respondents in Australia (in May 2017) felt more emotional taxation related to the issue of same-sex marriage than respondents in the other three countries that already had it. The same was true for the issue of gay military service: respondents reported less emotional taxation in each country that had already enacted legislation on that issue. In the United Kingdom and the United States, the age gap regarding concern about youth homelessness was large, but perhaps more surprisingly, it was also large with regard to overall mental health (Figure 3). Although these were the two most significant campaign issues in terms of emotional burden reported, this effect was almost entirely driven by younger activists, who were also significantly more distressed by concerns about workplace discrimination.

Overall, the distribution of emotional benefits and burdens is a core concept in social movement mobilization, in interest-group issue selection, in the makeup of coalitions, and in the activities and actions executed. It also further identifies the marginalization of oppressed groups like the transgender community. Tracking these distributions should be a standard part of social science research. Although it is not remarkable that our data are consistent with the theory of intersectionality, this is the first time this presumption has been confirmed within LGBTQI activism using quantitative survey data across four countries. Indeed, working within the movement may subject individuals to more emotional taxation than at any other point, and groups within groups may experience a compound emotional burden. These data provide new evidence to confirm the theory of negative exposure, and our analysis builds on this theory using the concept of emotional taxation. This study may be useful in further research on social movement mobilization or demobilization, issue selection within movements, and community resilience.

CONCLUSION

This study further demonstrates that LGBTQI pride comes at a cost. The data we report from 1,019 LGBTQI activists advances this effort and connects emotional taxation to agenda setting, social movement organizing, lobbying, and political instruments.

More research in this area, through the deployment of experimental survey methods and comparisons across varying emotional political issues, is needed. Understanding the burdens, punishments, negative mental health effects, and emotional costs faced by target populations based on how they participate in the political process is fundamental to political analysis. Greater understanding of the dynamics of emotional taxation may help ensure that the political process includes not only those who face few penalties for the most wide-ranging political endeavors but also those who are marginalized because of their gender or sexual identity. Politics is a team sport, but not all teams are created equal. This analysis has highlighted the emotional advantages that some receive simply by virtue of their identity. Moreover, these data suggest that the individual L-G-B-T-Q-I members of the collective community are not all impacted the same way by equality campaigns. The more adverse marginalization a group faces, the more emotional taxation they experience when they enter the political process, which has significant ramifications for their political engagement and efficacy. Leveling the political playing field in the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Australia, and elsewhere in the world will take more time, but identifying the existing inequalities in the way politics is played need not.