Within electoral systems using proportional representation (PR), two types of ballots are commonly used: in closed-list systems, voters choose among parties, and the order in which candidates take seats is fixed within parties; in open-list systems, voters choose among candidates, and the order in which candidates take seats is determined (at least in part) by individual candidate vote totals. By giving voters influence over not just the number of seats each party wins but also which candidates from a given party win seats, open-list systems introduce a measure of intraparty competition among candidates. Political scientists have argued that this intraparty competition tends to reward candidates who have more local background and experienceFootnote 1 and increases the incentive for elected politicians to deliver particularistic service to their votersFootnote 2 and even engage in corrupt activities.Footnote 3

While the literature helps us understand how different ballot types in PR systems affect legislative behavior, it offers fewer clues about how ballot type affects parties’ relative electoral success. This omission is puzzling not just because political scientists have a strong interest in the effects of electoral systems on party systems, but also because the partisan consequences of ballot type should be of first-order importance to the actors most responsible for choosing electoral systems – partisan politicians. Understanding these consequences may thus help us understand how specific features of electoral systems are chosen.

In this article we argue that an important determinant of the effect of ballot type on party support is the level of intraparty disagreement on salient issues. Disagreement among candidates within a party is typically a liability because it suggests disorganization and incoherence, but we offer two reasons why parties that are characterized by such disagreement may do better in open-list elections than in closed-list elections. The first reason is that some voters might find a particular candidate in a diverse party more attractive than the party itself, such that they would vote for that candidate under open lists but would vote for another party under closed lists. The second reason is that some voters may be drawn to the chance to weigh in on intraparty disagreement in open-list elections, such that under open lists they would vote to help one candidate in a diverse party defeat a co-partisan, whereas under closed lists they would vote for another party altogether. To the extent that these mechanisms operate, parties with intraparty disagreement would be better off in open-list competition, while relatively unified parties would be better off in closed-list competition.

We document this effect of ballot type on party vote choice in the context of a survey experiment focused on British elections for the European Parliament (EP). In these elections (as in EP elections elsewhere), the standard left-right dimension continues to organize political debate but there is a particularly salient additional dimension of conflict between pro- and anti-integration views.Footnote 4 In Britain, this second dimension is highlighted by the rise in support for the ‘Eurosceptic’ United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). The crucial point for our experiment is that UKIP is highly unified in its opposition to European integration while its competitors are more divided on this salient issue, as we document below. According to the theory we develop, a switch from the current closed-list system to an open-list system would tend to hurt UKIP, as voters who might otherwise vote for UKIP take advantage of the chance to vote for Eurosceptics in other parties – particularly the Conservatives, who are closer to UKIP on the economic dimension.Footnote 5 Indeed, our experiment shows that UKIP performs considerably worse under open lists than closed lists (19 per cent vs. 25 per cent of respondents in our survey), while the main parties perform better (particularly the Conservatives, who win about 28 per cent vs. 22 per cent). We show that this occurs because Eurosceptic voters abandon UKIP in favor of Eurosceptic candidates from the mainstream parties, particularly the Conservatives.

Understanding the partisan consequences of ballot type within PR systems is of clear policy relevance in elections to the EP, which take place under closed-list PR in some countries (including Germany, France, Spain and the UK) and open-list PR in many others. Some policy makers have called for the adoption of open lists in all European elections,Footnote 6 and our analysis indicates that such a reform would tend to bolster mainstream parties at the expense of Eurosceptic parties. More broadly, ballot type could have partisan consequences in situations where environmental parties rise to prominence (as happened in Europe with the Greens in the 1980s) or when anti-immigration parties attract support and mainstream parties are internally divided on the issue, as has occurred more recently.

Methodologically, our study departs from most previous work on electoral systems by relying on a survey experiment rather than observational data. One could address the same question with a cross-country regression, but in European elections (and other types of elections)Footnote 7 the countries that use different electoral systems typically differ in many other respects; this tends to make causal inferences depend heavily on modeling assumptions.Footnote 8 In our experiment, by contrast, we observe how similar voters behave when they face the same basic choice but a different type of ballot. Of course, there are important disadvantages of an experimental approach, of which we emphasize two: first, the behavior of experimental subjects when faced with a hypothetical ballot may differ in important ways from the behavior of voters in a real election; secondly, while our study sheds new light on how voters respond to changes in ballot type (given a set of parties and candidates), it does not tell us how parties and candidates would respond to a change in ballot type and how those responses would in turn affect electoral outcomes. Despite these limitations (which we discuss further in the conclusion), we argue that our theoretical analysis and experimental results contribute to existing knowledge of how political outcomes depend on features of the electoral system.

Which Parties Benefit from Open-List ballots?

In this section we consider reasons why a move from closed-list to open-list ballots might help some parties and hurt others. Our focus is on the role of intraparty disagreement. Although intraparty disagreement may be a liability for any party under either closed-list or open-list PR elections, we expect parties with more intraparty disagreement to attract more voters under open-list competition than under closed-list competition, particularly when ideologically proximate parties have low levels of intraparty disagreement. The logic behind this explanation applies whether we consider voters to be expressive or strategic.

Expressive Voters and Intraparty Disagreement

Suppose that voter behavior is described by the following two assumptions:

E.1 Voters are expressive, meaning that they vote for the party or candidate they find most attractive and do not consider how their vote is likely to affect policy outcomes.

E.2 Voters cast their vote in a closed-list system based on the attractiveness of the parties, whereas they vote in an open-list system based on the attractiveness of the candidates.

Under these two assumptions, it follows that list type affects a voter’s party choice when party X is the most attractive party under closed lists, while a candidate from party Y is the most attractive candidate under open lists.

An example clarifies how this might happen. Suppose that in a given setting the Green Party is associated with clear positions on both economic and environmental policy; the Socialist Party, by contrast, has a clear left-wing economic position but has substantial intraparty disagreement on environmental policy, with some Socialist candidates strongly pro-environment and others less so. In an election held under closed lists, a left-wing environmentalist voter may find herself torn between the two parties: the Socialist Party may be more attractive on economic grounds, but the Green Party is more attractive on environmental policy. Suppose that under closed lists she votes Green because she views environmental issues as more important. Now consider her vote choice under open lists. Because there are Socialist candidates who advocate strong pro-environment policies, our voter may choose to support a pro-environment Socialist candidate who shares her left-wing economic preferences. If so, the list type would have affected the voter’s party choice because even though the most appealing party under closed lists was the Greens, the most appealing candidate under open lists was a Socialist.Footnote 9 To be clear, the Socialists’ lack of unity on environmental policy is not per se an attraction; on the contrary, the party’s internal disagreement may on balance be a liability in both closed-list and open-list competition. Rather, given the party’s internal disagreement we expect it to be more successful under open lists than under closed lists because expressive voters may be drawn to the party by the opportunity to support particularly attractive individual candidates.

Figure 1 illustrates the argument in a simple spatial model. There are two parties, X and Y, each identified with its own position in two-dimensional space; within each party, three candidates occupy distinct positions near their party, though party Y’s candidates are more distinct from each other. Asked to choose between parties (as in closed-list competition), an expressive voter with an ideal point at a would choose party X, whose position is slightly closer to her own ideal point. Asked to choose among candidates, however, the same voter would choose y 1. The situation corresponds to the example given above, where parties X and Y are the Greens and the Socialists, respectively and the horizontal and vertical dimensions are economic policy and environmental policy.

Fig. 1 Ballot type and party vote choice when intraparty disagreement varies across parties

Strategic Voters and Intraparty Disagreement

We see the same relationship between intraparty disagreement and list type, although for different reasons, if we assume instead that voters are strategic. Consider the following two assumptions about voter behavior:

S.1 Voters are strategic, meaning that they decide how to vote based on how they think their vote could affect policy outcomes.

S.2 Voters believe that policy outcomes depend on which candidates are elected.

Under these assumptions, list type affects a voter’s party vote when the voter believes that her best chance of electing a more favorable candidate under closed lists comes from voting for party X, while her best chance of electing a more favorable candidate under open lists comes from voting for a candidate of party Y.

A strategic voter considers the possible ways in which her vote could affect the outcome and chooses a strategy that maximizes the expected benefit from her vote.Footnote 10 In both open-list and closed-list elections, the potential ‘pivotal events’ include all situations in which the marginal seat will go to either a candidate from party X or a candidate from party Y, for every pair of distinct parties and candidates within those parties; list type could affect a strategic voter’s party choice by changing the relative probability of these events.Footnote 11 There is also an important set of pivotal events in open-list competition that are not found in closed-list competition: open-list elections offer voters the prospect of determining which candidate from a given party gets elected, which may attract voters to parties in which candidates differ in important ways. Suppose, for example, that in a two-seat district party Y is almost certain to win exactly one seat, while the second seat will be won by either party X or party Z. Under closed lists it would make little sense to waste a vote on party Y, regardless of one’s preference ordering over the parties; a strategic voter should then vote for either party X or party Z. Under open lists, however, it may be the case (assuming the same distribution of party votes) that there is doubt about which candidate will win party Y’s seat and the voter may expect a higher policy benefit from using her vote to affect that outcome than influencing which party/candidate wins the second seat. In short, in this example voting for party Y is more attractive under open lists because the open-list system introduces intraparty competition and allows voters to participate in a ‘primary’ election for candidates from each party and thus provides a reason (absent in a closed-list system) to vote for party Y.Footnote 12 As in the expressive case, these benefits will accrue to party Y only when the candidates of that party hold policy positions that distinguish themselves from their co-partisans. If Y’s candidates are indistinguishable from one another, a strategic voter has no incentive to participate in this ‘primary’ election for the first seat in the district and will instead cast her vote for either X or Z in order to maximize her expected benefit from the second seat in the district.Footnote 13

The main implication of the foregoing analysis is that a move from closed-list to open-list elections is likely to be more beneficial to parties with internal disagreement than to parties that are relatively unified. To be clear, we do not mean to imply that internal disagreement itself is electorally beneficial under either closed-list or open-list competition; indeed, a party may suffer in both systems from internal disagreement, as voters see the party as incoherent and confused. Our point is that a party that has a relatively large degree of internal disagreement can expect to do better in open-list competition than in closed-list competition because expressive voters may be attracted to particular candidates in the party and strategic voters may be attracted by the chance to determine which candidates win seats within the party.

Which Parties Have Intraparty Disagreement on Salient Issues?

The level of internal disagreement may vary across parties in a given system for many reasons. In any electoral system, there is a trade-off between a party’s ability to offer a variety of candidates who cater to disparate tastes and goals in the electorate, on the one hand, and its ability to present a coherent and unified party brand,Footnote 14 on the other hand.Footnote 15 There may also be tension between the interests of party leaders, who value a coherent party brand and the interests of candidates, who may seek to differentiate themselves from the party in order to cultivate a personal vote.Footnote 16 The way parties resolve these tensions is likely to depend in subtle ways on their history, leadership and internal governance.

It is also important to recognize that the level of internal disagreement often varies within parties across issues; thus the effect of ballot type on a party’s electoral support may depend on which issues are salient. To use the example from the previous section, the Socialist Party may benefit from a transition to open-list competition if environmental issues are particularly salient (assuming that the Socialists have more internal disagreement on environmental issues than the Greens), while the Green Party may benefit from the same transition if economic issues are particularly salient (assuming that the Greens have more internal disagreement on economic issues).

One case where there may be particularly clear differences in internal disagreement across parties is when a ‘niche party’ competes on a salient issue against mainstream parties. Niche parties tend to emphasize issues that cut across the main dimension(s) of political competition; typically, they are highly internally unified on these issues, which helps them appeal to their ‘ideological clienteles’Footnote 17 and form a party brand.Footnote 18 Mainstream parties, by contrast, sometimes struggle to define a position on the issues emphasized by niche parties, particularly during the period when the issue is rising in salience. For example, Green parties and anti-immigration parties in Europe compete on the basis of strong and internally unified positions on issues on which the mainstream parties are internally divided. We might expect a move from closed-list to open-list competition to be damaging to the niche party when the niche party’s issue is salient to voters.

The idea that ‘niche’ parties might do worse in open-list competition would seem to apply particularly well to the case of European Parliament elections, where Eurosceptic parties have recently captured substantial electoral support. Eurosceptic parties define themselves by their opposition to the current design and operation of the EU. They compete against mainstream parties that originate from – and mainly compete in – national politics on a variety of other issues; they tend to have positions on Europe that are less salient, more vague, more variable over time and more diverse within the party. Expert surveysFootnote 19 confirm this difference, showing that parties that place a high salience on European integration are significantly less likely to be viewed as internally conflicted on the issue.Footnote 20 In open-list elections focused on the question of European integration, mainstream parties can field candidates representing the range of positions on Europe, which (following the logic outlined in the previous section) seems likely to undermine support for Eurosceptic parties.

This general pattern fits the specific case of European elections in Britain well. UKIP has recently risen to prominence as a strongly Eurosceptic party; the mainstream parties, by contrast, are characterized to various extents by internal disagreement on the question of European integration. Intraparty disagreement is most pronounced within the Conservative party, with Conservative Members of Parliament and Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) openly expressing Eurosceptic views that go well beyond the party line,Footnote 21 but elite dissent is also visible in the Labour PartyFootnote 22 and, to a lesser extent, among the traditionally strongly pro-Europe Liberal Democrats.Footnote 23 Supporters of the major parties also express a variety of viewpoints toward European integration. We observe this in our own survey, as documented in Appendix Table S4: although respondents supporting Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats show a clear pro-Europe tendency, a substantial minority in each party expresses opposition to European integration.

In conjunction with the analysis in the previous section, this variation in intraparty disagreement across parties suggests a prediction about the effects of changing EP elections in Britain from a closed-list to an open-list format. The salient issue in these elections is (and will likely continue to be) the UK’s role in the European Union. On this issue, UKIP is (and will likely continue to be) highly unified compared to other mainstream parties. As a result, we expect UKIP to suffer from the introduction of open-list competition as Eurosceptic voters take advantage of the opportunity to vote for Eurosceptic candidates from other parties.

Hypothesis 1: UKIP will receive fewer votes under open lists than under closed lists.

The direct corollary is that the Conservatives, which is the closest party to UKIP on the left-right dimension of conflict, will gain the votes that are lost by UKIP when open-list competition is introduced.

Hypothesis 2: The Conservatives will receive more votes under open lists than under closed lists.

In the next section we introduce the experiment we designed to test this hypothesis.

Experimental Design

Our experiment was embedded in a survey conducted by the research firm YouGov and fielded between 26 June and 5 July 2013. The survey was administered to a random sample of 9,096 panelists who are, according to YouGov, representative of British adults in terms of age, gender, social class and newspaper consumption. For all analyses below, we use probability weights provided by YouGov to weight the survey to the national profile of all adults aged eighteen or older.Footnote 24

For the core of the survey experiment, we asked subjects to vote in a hypothetical election for EP. All subjects were shown a ballot listing three candidates from each of five parties (Conservative Party, Green Party, Labour Party, Liberal Democrats and UKIP).Footnote 25 Half of the subjects (chosen at random) were shown a closed-list ballot and asked to pick a party; the other half were shown an open-list ballot and asked to pick a candidate. As discussed above, our principal interest is in how parties’ vote shares depended on ballot type.

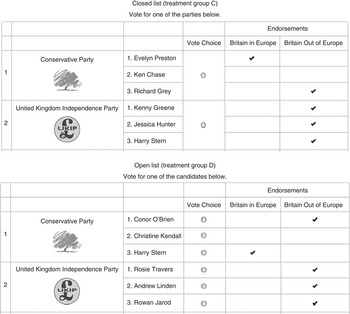

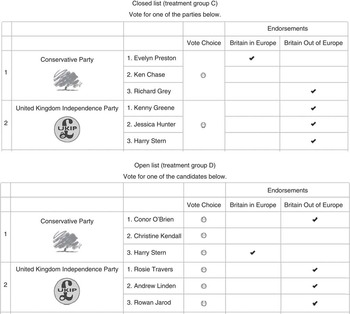

As a general matter, ballot type could affect party vote choice only if voters have preferences not just between parties but also among the candidates within parties. Given that the candidates in our experiment are all fictional, any preferences that our survey respondents had among candidates could only come from information we provide. We thus had to think carefully about what information to provide. A first question involved how much information to provide about the candidates. Ideally, we wanted to provide candidate information similar to what a British voter might acquire during the several weeks of an election campaign, when (depending on campaign behavior, which may itself depend on ballot type)Footnote 26 the voter may receive fliers from various candidates and parties, watch debates, read endorsements, etc. Unfortunately, such a large and nuanced amount of information could not realistically be communicated in the few seconds that survey respondents spent learning about fictional candidates for our experiment. Ultimately, we decided to provide a subset of respondents with limited but clear information about the candidates’ positions on Europe: in addition to a name (and thus gender) and party affiliation, each candidate was endorsed by a (fictional) pro-integration pressure group called ‘Britain in Europe’, a (fictional) anti-integration pressure group called ‘Britain Out of Europe’, or neither. Respondents received this information in two steps: first they were shown a screen explaining the endorsements and listing the endorsed candidates (as shown in Figure 2); on the next screen they were again shown the endorsements alongside the ballot as a kind of ‘voter guide’ (as shown in Figure 3).

Fig. 2 Endorsement information provided to respondents before voting

Fig. 3 Excerpts from closed-list and open-list ballots, including endorsement information Note: actual ballots (shown in Appendix Figures S7–S10) provide more detailed instructions and include candidates for all five parties.

A second question involved the nature of the endorsements we assigned to each party’s candidates. As discussed above, we argue that intraparty disagreements about European integration are likely in the major UK parties, but not in UKIP. Accordingly, for each of the non-UKIP parties (Green, Labour, Liberal Democrat, Conservative), we had one of the three candidates endorsed by the pro-Europe group, one endorsed by the anti-Europe group and one endorsed by neither. For UKIP, we assigned an anti-Europe endorsement to all three candidates. It is therefore through the provision of endorsement information that we incorporate our theoretical assumption about intraparty disagreement into our empirical design.Footnote 27

In order to disentangle the effect of the ballot type from the effect of the information we provided to respondents, we designed the experiment as a two-by-two factorial design (highlighted in Table 1) in which ballot type (closed or open list) and endorsement information (provided or not provided) are independently randomly assigned. Thus roughly one-quarter of our respondents was given ballots like the one shown at the top of Figure 3 (treatment group C, in Table 1) and one-quarter was given ballots like the one shown at the bottom of Figure 3 (treatment group D, in Table 1). Another quarter (treatment group A) was given a closed-list ballot with no endorsement information and another quarter (treatment group B) was given an open-list ballot with no endorsement information. This design allows us to address two potential objections to the endorsement information we provided as part of our experiment.

Table 1 Design Table

Note: weighted sample sizes shown.

The first potential concern is about internal validity of the study: if we only showed the endorsement information to respondents who are also given an open-list ballot, then it would be impossible to disentangle the effect of the information we provide from the effect of the ballot itself.Footnote 28 The second potential concern relates to the external validity of the study: if all respondents are shown this endorsement information and if this information is too divergent from the way in which voters typically think of the parties, then the ballot type effect we detect may be very different from the effect that would be seen if the ballot type were actually changed. The factorial design allows us to address both concerns. Clearly, because we can separately test the effects of the endorsement information and the ballot type, we can address the internal validity concern. The design also allows us to address the external validity concern by testing whether the provision of information per se affects party vote choice among respondents who are given a closed-list ballot. As we show below, it did not, which suggests that our endorsements reflect positions on Europe that are not too dissimilar from what voters might expect to see from each party.Footnote 29

Another external validity objection could be raised, which is that the endorsement information was provided in a particularly heavy-handed way. Granted, such endorsements would never appear on an actual ballot paper; the information that voters receive about candidates would tend to be much more noisy and multi-dimensional. Yet voters in a real election would have weeks to process the information to which they may be exposed and they would be able to actively seek out the specific information that may be of use to them (for example, ‘Which Labour candidate is most pro-integration?’). It is also not unusual for voters facing complex ballots to be given voter guides by candidates and civil society groups. We view our information treatment as a compromise made necessary by the constraints of running a hypothetical election with survey respondents who have limited time to process new information.

Before we proceed to the results, we first check the balance of the respondents’ covariate distributions across the four treatment groups. As expected from a randomized treatment allocation, the tests show no sign of imbalance. More precisely, the p-values calculated from a joint F(3, N−df) test of no differences between the twenty-two covariate means (all measured pre-treatment) across the four treatment conditions follow the expected uniform distribution over the [0, 1] interval. Appendix Figure S11 plots the empirical distribution of the p-values from these balance tests against the theoretically expected uniform distribution:Footnote 30 since all p-values are above the forty-five degree line, we can safely assume that randomization was successful. Appendix Table S5 shows the underlying covariate means and corresponding F-tests across the four treatment conditions.

Results

Main Results: Endorsements, Ballot Type and Party Vote Shares

To evaluate the effect of ballot type on party vote shares, we separately compare the party vote shares for the five main parties under the four treatment conditions indicated in Table 1; in particular, we run a separate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for each party in which the dependent variable is 1 if the respondent chose this party (otherwise 0) and the regressors are a binary indicator for open list, a binary indicator if information about the candidates was provided, an interaction of the two indicators and a constant. Table 2 presents the regression results.

Table 2 Main Regression Results of Parties’ Vote Shares by Treatment Conditions

Note: separate OLS regressions for Models 1–5. Regression coefficients shown with corresponding t-statistic in parentheses. All regressions are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

Note first that the constant term in each regression measures the proportion of respondents in treatment group A (closed-list ballot and no endorsements) that selected a given party (12 per cent for the Greens, 30 per cent for Labour, 10 per cent for the Liberal Democrats, 24 per cent for the Conservatives and 25 per cent for UKIP). These proportions differ somewhat from the results of the 2014 election,Footnote 31 but they are quite close to the average of six polls that took place in 2013 (the year we ran our survey).Footnote 32 This highlights the representativeness of our sample, suggests that our hypothetical ballot accesses the same preferences as more standard vote intention questions and reinforces the external validity of our survey experiment.

The regressions indicate that neither the ballot type nor the endorsement information has an independent effect on vote choice: neither coefficient approaches statistical significance in any of the five regressions. The insignificant coefficients on Open List indicate that among respondents who were not shown any endorsement information about the candidates (treatment groups A and B), ballot type did not affect party vote choice on average. This makes sense, given that respondents have no reason to prefer individual fictional candidates unless they know something about them. The insignificant coefficients on With Information similarly indicate that among respondents who were shown closed-list ballots (treatment groups A and C), the provision of endorsement information does not affect party vote choice on average. This is reassuring evidence that the endorsement information we provided roughly comports with voters’ perceptions of the parties and thus that our evidence may be informative about what would happen if open lists were introduced.

We now turn to the interaction term in the regressions in Table 2, which indicates how the effect of ballot type differs between the informed group (treatment groups C and D) and the uninformed group (treatment groups A and B).Footnote 33 The interaction term is significant only for the Conservatives (who gain from open lists) and UKIP (who lose). This finding is consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2 above, which predicted that UKIP would lose support because of its unified position on European integration while the mainstream parties would see little net exchange of votes. The Conservatives appear to benefit at UKIP’s expense because of the parties’ relative proximity on other issues; we will further examine this interpretation below. As can be expected from a randomized experiment, these results do not depend at all on whether we include a large set of respondent characteristics (respondent’s attitude toward Europe, socio-demographic characteristics and previous vote choice) in the regression.

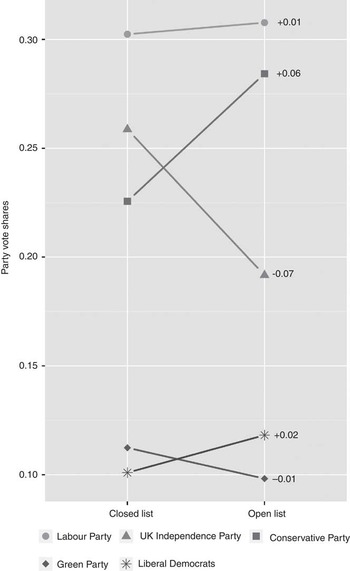

Figure 4 presents the same results graphically. Based on the findings above, we focus on comparing the vote choice in treatment groups C and D (that is, those who were given the endorsement information).Footnote 34 As seen in Figure 4, the Conservative Party gains about 6 percentage points (a 26 per cent increase in vote share, with 95 per cent confidence interval [0.12, 0.40]) from a move to open-list competition. The mirror image of this shift is a corresponding decrease in vote shares for UKIP, which loses about 7 percentage points (a 26 per cent decrease in vote share, with 95 per cent confidence interval [−0.38, −0.14]). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, we find no sizeable or significant effect for any of the other parties (Labour, Liberal Democrats and the Greens). Appendix Figure S12 depicts party vote shares in all four treatment conditions.

Fig. 4 Effect of change from closed-list to open-list ballots on party vote shares Note: changes in party vote shares when moving from closed lists to open lists, given endorsement information. While the increase (decrease) for the Conservative Party (UKIP) is highly significant, the much smaller shifts for Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens are not statistically different from 0. All estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

Subsample Analysis: Interactions with Respondents’ Party Identification and Stance on Europe

Our theoretical analysis made clear that we do not expect the effect of ballot type to be uniform across all voters. Specifically, we expect voters who have preferences close to a mainstream party on one dimension, but close to the niche party on a cross-cutting dimension, to be most likely to change party when moving from closed to open lists (assuming that the candidates of the mainstream party differentiate). This subsection examines which voters in our experiment are most affected by the change in ballot type and, in particular, if these effects interact with respondents’ party identification and stance on European integration.

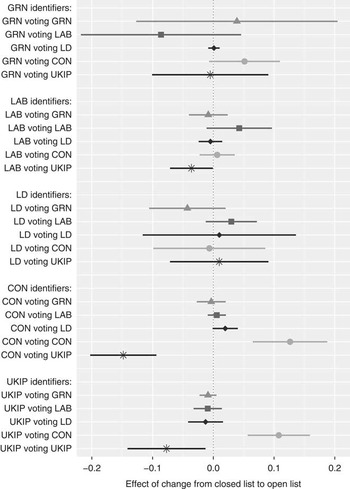

Prior to participating in our experiment, survey respondents were asked, ‘If there were a general election held tomorrow, which party would you vote for?’. To understand which voters are affected by ballot type, we run the same analysis as above (a separate regression for each party, measuring the effects of ballot type, information provision and interaction) while subsetting the analysis by respondents’ party identification. The resulting twenty-five estimates are presented in Appendix Table S6 and compactly visualized in Figure 5.

Fig. 5 Effects of change from closed-list to open-list ballots, by respondents’ party identification Note: changes in party vote shares when moving from closed-list to open-list ballots, given endorsement information. Point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals from twenty-five separate OLS regressions for each party vote share and each subsample of respondents identifying with one of the five main parties. All estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

The results for the different party identifiers give rise to a more detailed picture. Focusing on respondents who identify with the Conservatives, we see that they are 13 percentage points more likely to vote for the Conservatives in our experimental EU parliamentary election when given an open-list ballot than when given a closed-list ballot, assuming the provision of endorsements (p<0.01, two-tailed test). Similarly, the same group of Tory identifiers is 15 percentage points less likely to vote for UKIP (p<0.01, two-tailed test). Again, we essentially find a mirror image for respondents who identify with UKIP: they are 11 percentage points more likely to vote for the Conservatives under an open-list system (p<0.01, two-tailed test) and, correspondingly, 8 percentage points less likely to vote UKIP (p<0.02, two-tailed test). Hence, it is worth noting that the increase in support for the Conservatives comes not only from Conservative identifiers who can now vote for Eurosceptic candidates of their preferred party, but also (though to a lesser degree)Footnote 35 from UKIP identifiers who would vote for specific Conservative candidates if they had the chance to do so. Almost all other twenty-one regression estimates are small in substantive terms and not significantly different from zero. The only exception is that Labour identifiers appear to be marginally less likely to support UKIP, which is consistent with the idea that some Eurosceptic Labour voters vote UKIP under closed lists but Labour under open lists.

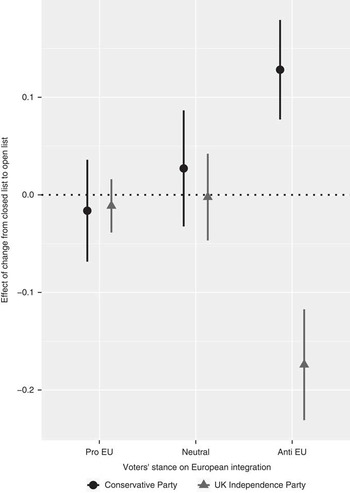

Having established that most of the action takes place among Conservative and UKIP voters, we now turn our focus to the interaction of ballot type and respondents’ position on Europe for these two parties. Respondents’ stance on European integration is measured using an 11-point question ranging from ‘strongly opposed to British membership of the EU’ (0) to ‘strongly support further British integration in the EU’ (10).Footnote 36 For the analysis, we recode this item in three binary indicators: Anti EU for values between 0–3, Neutral for values between 4 and 6, and Pro EU for values between 7–10. Figure 6 displays the results from separate OLS regressions for the three groups Anti EU, Neutral and Pro EU for the Conservative party and UKIP, respectively.

Fig. 6 Effects of change from closed-list to open-list ballots, by respondents’ stance on Europe Note: changes in party vote shares when moving from closed-list to open-list ballots, given endorsement information. Point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals from OLS regressions for the Conservative and UKIP vote share, separately estimated for pro-European, neutral and Eurosceptic respondents. All estimates are weighted using YouGov’s survey weights.

The pattern that emerges could not be clearer: respondents who support further integration of Britain into the EUFootnote 37 do not change their voting behavior depending on the ballot type at all and the effect among respondents who are neutral is small and not significant. However, among Eurosceptic respondents – about 45 per cent of all Conservative voters and 77 per cent of all UKIP voters – the shift from a closed to an open list has major consequences: the vote share for the Conservatives increases by almost 13 percentage points (p<0.01, two-tailed test) and the vote share for UKIP decreases by more than 17 percentage points (p<0.01, two-tailed test).

To summarize, the subsample analysis confirms that the shift in vote shares from UKIP to the Conservative Party comes from Eurosceptic voters who identify with either the Conservatives or UKIP. This offers further support for our argument about intraparty disagreement and ballot type.

Discussion and Conclusion

Which parties win and lose when a closed-list PR system (such as the one Britain uses to elect its MEPs) is changed to an open-list system? We used a simple framework to assess how such a change would affect parties with different levels of internal disagreement on salient issues; we conclude that whether we think of voters as expressive or strategic, a change from closed lists to open lists is likely to be more beneficial to parties that have relatively high levels of internal disagreement on salient issues. We carried out a survey experiment that assessed this prediction in the case of UK elections to the European Parliament, where the solidly Eurosceptic UKIP competes against mainstream parties that are more internally divided on European integration. We suggest that, just as UKIP lost support from the adoption of open lists in our experiment, niche parties (which mobilize on an issue that cuts across the main dimension of party competition) would likely lose support from the adoption of open lists in a broader set of circumstances.

It should be noted that our analysis only addresses the most direct and immediate effect of a move from closed-list to open-list PR. That is, we have shown how the effect of ballot type depends on existing intraparty disagreement, but we have not addressed the question of how ballot type would affect intraparty disagreement itself, or how parties would respond more broadly to the introduction of intraparty competition. By placing each party’s candidates in competition with each other, the open-list system is likely to encourage differentiation among candidates. For the reasons discussed above, a party whose candidates are more distinct from one another may attract voters from more unified parties in open-list competition; voters may, however, punish such a party for appearing incoherent and disorganized. Thus the implications of reform for parties’ electoral success become less clear when we consider that parties’ internal disagreement would likely respond to the ballot type and that this response will vary across parties. In this sense, additional observational studies should be carried out to assess the total effect of ballot type reforms in practice. Yet observational studies of electoral reforms face substantial obstacles not only because reforms are rare and endogenous, but also because it is difficult to explain how such a reform affects political outcomes given the many possible channels through which such effects might operate.

As discussed above, one clear challenge to the external validity of any experiment like ours is the difficulty of reproducing the relevant aspects of an electoral campaign within the constraints of a survey. In our case, it could be argued that our estimates exaggerate the true likely effects of a change in ballot type (even holding fixed intraparty disagreement) because our respondents are given unrealistically clear and stark information about candidates’ policy positions. To be sure, an official ballot would not include endorsement information from two opposing NGOs; in a real open-list campaign we would expect candidates to blur some policy differences and we would not expect most voters to know most candidates’ positions. (We might also expect UKIP to point out that voting for a Eurosceptic Conservative could end up giving a seat to a pro-Europe Conservative.) However, voters in a real election would have more time to process information and, given the chance to cast an open-list ballot for an individual candidate, they may be drawn into the drama of intraparty disputes, which would tend to increase the effect we measure. We look forward to future research, including observational studies of electoral reforms, that helps determine whether our estimates provide an upper bound of the actual effect. At any rate, even if the true effect were substantially smaller than our estimate it would still deserve attention: we estimate that with a swing half as large as the one we find in our experiment, the Conservatives would still have gained an additional four seats out of seventy-three UK wide.

The context on which we focus, where an insurgent anti-integrationist party competes against mainstream parties for seats in the EP, has clear analogs in other European countries. For example, the Alternative for Germany, the Front National in France and the Danish People’s Party all promote anti-integrationist policies that differentiate them from the main center-right parties in each country. Elections in these countries also take place under closed lists, but in recent years key figures have called for open lists to be adopted in all EP elections.Footnote 38 While we should be cautious about applying the results of our experiment to other party systems, our analysis suggests that such a reform could noticeably boost mainstream parties in European elections and thus cause a substantial shift in the strength of party groups in the EP; the broader effects of introducing open-list elections on the policies pursued by the various parties remains for future research.