Introduction

Should the host of a dinner party arrange the seating of their guests or leave it to the guests themselves? Ironically, this question about how to enhance social intercourse provoked a dispute between two dinner guests at a drinking party in Roman Greece around the turn of the second century CE. According to Plutarch’s Sympotic Questions (Quaestiones conviviales), the philosopher’s brother, Timon, and father disagreed over how to seat guests on the couches in a dining room, or triclinium (1.2–3). Timon believed that seating should be democratic, but his father supported a hierarchical arrangement that would recognize distinctions of wealth, rank, age, and family. The cultural contingency of these spatial conceptions becomes apparent when an arriviste appears at the entrance of the triclinium only to retreat upon finding that an honorable seat had not been reserved for him. The insulted latecomer, like Plutarch’s father, expected a Roman seating arrangement that acknowledged his wealth and status rather than a Greek arrangement. Plutarch, we soon learn, opts for a compromise: he prefers the Greek democratic mode for young guests, citizens, and friends but favors status distinctions for foreigners, elders, and rulers. He also insinuates that the proper distinction in seating should valorize someone who acquired virtue through Greek learning (παιδεία) instead of wealth and status by chance (τύχη).Footnote 1

Jewish literary texts from Early Roman Palestine contain very similar negotiations of Roman architectural forms and spatial practices. The Roman triclinium, or dining room comprising three couches for reclining, receives frequent mention in New Testament scholarship.Footnote 2 But it usually surfaces in discussions of meals and social status in the Pauline assemblies in Greece and Asia Minor or the development of the domus ecclesia.Footnote 3 Meanwhile, archaeologists of Palestine have focused on triclinia of the second and third centuries, and scholars of Judaism on the rabbinic symposia.Footnote 4 There has been very little sustained investigation into the emergence of triclinia in Early Roman Palestine (63 BCE–70 CE) and the Jewish literary responses to this new type of social space.Footnote 5

This study begins to fill this gap in scholarship on local reactions to the early stages of provincial transformation in the Levant. It thus serves as a contribution to debates over the vexed concept of “Romanization,” whose problematic binaries of acculturation and resistance, Roman and native, imposition and acceptance, and aristocracy and peasantry persist in scholarship on ancient Judaism and the New Testament despite their persuasive dismantling by a number of classical historians.Footnote 6 Instead of viewing the triclinium as a Roman spatial imposition, and Jewish literary representations of it as expressions of anti-Romanization, I demonstrate that both sets of data constitute distinctive provincial negotiations of cultural and socioeconomic shifts in the early empire.

After examining the archaeological and literary evidence of triclinia in Early Roman Palestine in two respective sections, I draw on critical spatial theory in order to synthesize and explain what this evidence indicates about changing understandings of space as Palestine gradually became a province of the Roman Empire. I focus, in particular, on spatial trialectics, or the different ways in which Jewish elites formed new social spaces through the combination of Greco-Roman and local constructions of space. This theoretical model, I contend, proves more fruitful than unilateral models of architectural, cultural, and socioeconomic change, for it recognizes social agents’ diverse and dynamic contributions to the production of provincial spaces.

The Archaeology of Triclinia in Early Roman Palestine

Archaeological evidence is our most important source for the origins of the triclinium in Early Roman Palestine. Architectural remains supply only a portion of the information required to understand the social relations implied by such spaces, however. Other forms of material culture, ranging from wall decorations to tableware, provide important additional clues as to how ancient persons construed and constructed these spaces, and consequently what these spaces represent about cultural, social, and economic change. In this section, I identify shifting conceptions of the spatial organization of social relations in the material record of triclinia from Early Roman Palestine. I note, in particular, that Jewish kings and elites increasingly produced dining spaces that implied social hierarchy, displayed lavish imported goods and styles, and boasted the host’s control over their social environment.

Before turning to the evidence from Early Roman Palestine, a brief overview of the development of the triclinium is in order. The triclinium is an Italian novelty based on Greek and Hellenistic precedents. While Plutarch’s observation about the dissimilarity between the Greek and Roman modes of dining finds support in the archaeological evidence of banqueting rooms, the history of this type of room, including its particular social dynamics, is more complex. As Katharine Dunbabin explains, with respect to the development of the Roman dining room: “The Roman aristocracy adopted the fashions set by Hellenistic royalty, and in turn were copied, less grandly and on a smaller scale, by the wealthy of a town like Pompeii, and doubtless elsewhere in Italy. In time, these fashions came back to the Greek world, to the circles of men like Plutarch.”Footnote 7 Cultural contact between Rome and the East in the late Republic induced this gradual and syncopated process, which Dunbabin has described as “mutual acculturation.”Footnote 8

In terms of the architecture of dining spaces, the transition in Greek contexts under Roman influence was from the andrōn to the triclinium. To be clear, titles such as andrōn and triclinium were used by ancient authors but not always with as much precision as modern scholars have used them to distinguish these spaces.Footnote 9 Following scholarly conventions, in the ensuing discussion, I use andrōn to designate the Greek-style dining room and triclinium for the Roman-style room, though I will also call attention to dining spaces that fall on the spectrum between these convenient scholarly types.

The andrōn, or men’s hall, was a nearly square room with an off-center door and portable couches on three and a half sides, often marked off by the design of the pavements. There are usually seven or eleven couches, each fitting one or two male guests (approx. 1.8 x 0.8 m).Footnote 10 This type of room, well known from Olynthus (fifth/fourth centuries BCE), is characterized by seclusion within the house, a considerable central space for service and entertainment, and an egalitarian seating structure. Some sources recognize special seats for the guest of honor and host, but the architecture does not entail strict hierarchical divisions.Footnote 11 In this space of commensality among men, the symposiasts’ attention is focused on the central entertainment.

Unlike the andrōn, the triclinium was a hierarchical space whose focus was the host’s wealth, status, and power. “Triclinium” is the latinization of the Greek word τρίκλινος and refers, in the strict sense, to three broad couches (κλίναι) arranged in the shape of the Greek letter Pi (Π) along the three walls of a room that opens up onto a peristyle (i.e., a courtyard surrounded by rows of columns forming a continuous porch around it), garden, or spectacular land- or seascape. Each couch (measuring about 2–4 x 1.5 m) fits three male or female guests who recline on their left elbows facing a central table in a narrow space serviced by slaves.Footnote 12 The arrangement around three walls rather than four supports a hierarchical seating pattern (see fig. 1). Literary sources designate the couches as summus (highest), medius (middle), and imus (lowest), and each position on each couch was also ranked. Typically, the third place on the middle couch was the seat of honor, or “consul’s place” (locus consularis), while the adjacent first place on the low couch was reserved for the host.Footnote 13 This pattern placed the guest of honor and host at the center of the conversation and gave them the best view.Footnote 14 In this space, entertainment was decentered and served to define—along with decoration (mosaics, frescoes, furniture), fineware, fancy foods and wine, proper service, and the view from the couches—the cultural and socioeconomic preeminence of the host.Footnote 15 In urban contexts, sight lines through the house to the triclinium made this image of the host visible to passersby.Footnote 16

Figure 1. Diagram of a common triclinium seating pattern known from literary sources. Drawing by J. R. Clarke (reproduced with permission). Footnote 17

In the Roman East, the introduction of the triclinium was preceded by the emergence of the broad-room. This is the scholarly term for rooms that emerged in the late Hellenistic period as a virtual blend of the Greek andrōn, the audience hall of Hellenistic palaces, and the Roman triclinium. Vitruvius describes these large banqueting rooms as oeci and distinguishes different types.Footnote 18 Unlike the triclinium, this room was broader than long, but like the triclinium, it was usually on the central axis of the house, had a central door, and opened onto a peristyle. At an early stage, movable couches were organized around all four walls like an andrōn (e.g., the palace in Vergina).Footnote 19 But later versions only situated couches along three walls so as not to block doors or intercolumnar spaces. The broad-rooms of the Delos mansions (late second century BCE), for instance, likely contained couches on three walls, thereby dictating a more hierarchical order in which guests seated along the inner wall were in a privileged position.Footnote 20 Given the considerable presence of Italians at Delos, it is not surprising that Greek and Roman spatial templates merged in this context.Footnote 21

The broad-room form first appeared in the Levant in the late Hellenistic period. Its earliest witness is the Late Hellenistic Stuccoed Building at Tel Anafa in the Upper Galilee (late second/early first century BCE), technically in the hinterland of Tyre. A room to the north of this building’s large central courtyard seems to have been a broad-room.Footnote 22 This mansion, which closely resembled the Delian houses, incorporated such accoutrements as Ionic and Corinthian capitals, carved and painted stucco, mosaics, and hypocaust-heated baths. Ceramic finds show that guests in this broad-room dined with Syro-Phoenician fineware and imported goods from Rhodes, Cos, and southern Italy.Footnote 23

In the late Hellenistic period, the Hasmoneans also designed dining rooms that resembled the broad-room.Footnote 24 Particularly noteworthy are those in the identical Twin Palaces, both of which were slightly broader than long (9 x 7.5 m) and opened onto non-peristylar courtyards via two columns in antis (i.e., the two columns are framed by two antae, or pillars on either side of the entrance).Footnote 25 The room featured red and black painted stucco. A variant of the broad-room also appears in the first century CE in the Palatial Mansion of Jerusalem.Footnote 26 This banqueting space (6.5 x 11 m), in one of the upper levels of this terraced house, likely boasted a view through windows across the Tyropoeon valley toward the Temple Mount. Both phases of its wall and ceiling decorations are similar to Pompeian styles, though oddly in reverse chronological order.Footnote 27 Adjacent rooms may have been additional banqueting spaces for special guests. However, few clues have survived to reveal how couches were set up in this mansion.

Herod’s palaces include numerous types of banqueting spaces that should be considered oeci or, by a broad definition, triclinia.Footnote 28 Notably, most of Herod’s dining spaces are longer than wide and thus betray a more hierarchical seating arrangement. The room (measuring 15 x 10.5 m) at Herodium that was converted into a synagogue during the Revolts was originally a Herodian oecus. Longer than wide, it opened onto a courtyard, was decorated with painted plaster wall panels and opus sectile floors (i.e., floors paved with mosaics comprising thin sections of colored stone cut into various shapes and sizes and arranged in elaborate patterns), and was surrounded by columns along its three inner walls.Footnote 29 Herod’s Northern Palace at Masada featured, among its multiple potential dining spaces, a colorful oecus (10.3 x 9.0 m) on its lower terrace with a panoramic vista of the Dead Sea.Footnote 30 In Herod’s third palace at Jericho, a Corinthian-style oecus (i.e., colonnaded with a barrel vaulted ceiling) is the largest and most accessible room (18 x 12.5 m) and provides a view of the Wadi Qelt through a portico.Footnote 31 This same palace includes another T-shaped banqueting space that Herod would have reserved for more intimate parties.Footnote 32 Herod also had a T-shaped dining room in his seaside Promontory Palace at Caesarea Maritima.Footnote 33 Each of these dining spaces displayed Herod’s supraregional decorative and culinary tastes and his power over the natural environment.

As with the broad-rooms, these long oeci would have contained movable couches and tables. Considering Herod’s tastes, they probably would have been imported, like the Delian bronze couches discovered in a wrecked ship delivering dining furniture for the palaces in the client-kingdom of Mauretania.Footnote 34 Without pavement bands or mosaics, it is unclear how many couches would have been in each room or exactly how they would have been arranged. Josephus may not have exaggerated that Herod’s dining hall in his lost Jerusalem palace held 100 couches (B.J. 5.177; A.J. 15.318). What is clear, in any case, is that Herod produced socially hierarchical and ostentatiously cosmopolitan dining spaces.

There is much less ambiguity involved in detecting the function and organization of triclinia with masonry benches than other types of banqueting spaces. Only three have been discovered in Palestine, and they are all relatively early.Footnote 35 The earliest of these is an open-air triclinium in the lower wing of the Hasmonean complex at Jericho (fig. 2).Footnote 36 It was situated in a garden between the Twin Palaces and a swimming pool.Footnote 37 The couches were constructed in a Pi shape and sloped slightly upward toward an inner ledge that served as an armrest. It was designed to fit around a tree so that the tree stood between the places for the host and the guest of honor. This provided—I suggest—the most prestigious diners with the best shade. It was perhaps because of the cut-out for the tree that the masonry couch was extended in a second phase in order to fit the customary nine diners more comfortably. The inner sides of the couches were plastered and painted in colored panels, including one in Pompeian red.Footnote 38

Figure 2. Drawing of the first phase of the garden triclinium from the Hasmonean Twin Palaces complex at Jericho. Courtesy of Hillel Geva, reproduced with permission of Israel Exploration Society. Footnote 39

Another triclinium with stone benches is also from the Wadi Qelt area outside Jericho (fig. 3). Originally identified as a synagogue, the structure at this site should be considered part of a peristyle mansion from the late Hasmonean period (built 75 BCE–50 BCE).Footnote 40 Its location suggests that it belonged to the Hasmonean family or friends. This triclinium was added in a late phase and opens onto a peristyle courtyard, but not along a symmetrical central axis. Its Pi-shaped couch is made of field stones coated with lime plaster and is large enough for the conventional nine diners.Footnote 41

Figure 3. Plan of the late phase of the mansion at Wadi Qelt, showing the masonry triclinium in the room farthest to the west. Courtesy of Hillel Geva, reproduced with permission of Israel Exploration Society. Footnote 42

The third triclinium with stone benches was not part of a royal palace but rather a rural peristyle mansion.Footnote 43 An inscription from this building at Khirbet el-Muraq (in Idumaea, near modern Hebron) suggests that it might have belonged to a Jewish elite named Ḥilkiya.Footnote 44 At the center of the house was a peristyle courtyard incorporating an open-air masonry triclinium of standard dimensions. The area between the couches of the triclinium was paved with a mosaic, while the walls of the house were decorated with stuccoed and painted plaster.

While these are the only three triclinia with permanent couches presently known from Early Roman Palestine, triclinia and oeci were surely more widespread in elite domestic settings. For instance, a partially excavated first century CE peristyle mansion with opus sectile floors in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter almost certainly had a triclinium.Footnote 45 Similarly, partially excavated domiciles at both Tiberias and Sepphoris in the Galilee contained the decorative elements typical of peristyle mansions with triclinia—that is, columns, capitals, painted and molded stucco, and mosaics.Footnote 46 Both buildings have been attributed to Herod Antipas but could just as well have belonged to other Jewish elites.

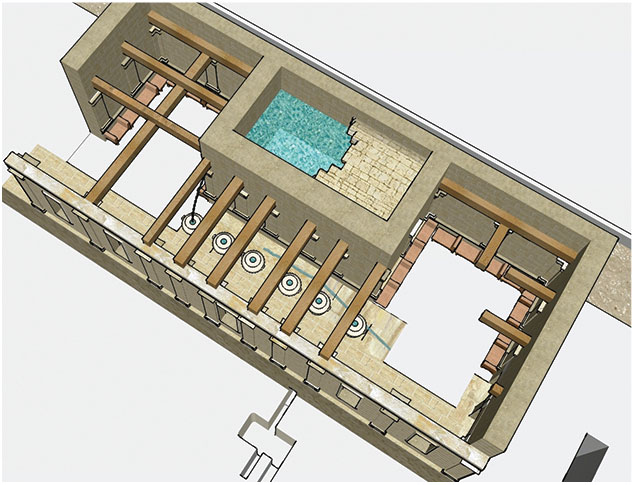

One final set of triclinia deserves special attention, for it was highly visible to pilgrims in Jerusalem. An independent structure dubbed the Banqueting Hall was built just prior to 22 BCE and used through the mid-first century CE (fig. 4).Footnote 47 It is located about twenty-five meters from the western wall of the Temple Mount and adjacent to Wilson’s Arch in the vicinity of the city’s main administrative buildings. The structure comprises two identical rooms separated by a fountain. Each room is decorated with engaged pilasters (i.e., nonstructural rectangular columns that project slightly from the wall) with Corinthian capitals. These pilasters sit on an elevated podium whose height was such that moveable couches could be situated beneath its cornice. Recesses discovered in the southern ends of walls in each room were likely used to hold the end couches in place. Although the southern part of this monumental building can only be conjectured, it must have opened onto the street with doors and windows. Diners in this independent structure were almost certainly Jewish elites who resided in Jerusalem or visited the city on pilgrimage. Its proximity to the temple suggests that it functioned like the banqueting halls of temples in cities like Palmyra and Petra.Footnote 48 If so, the space may have been controlled by the city’s priestly elites in particular.

Figure 4. Isometric reconstruction of the Jerusalem Banqueting Hall, created by Yaakov Shmidov. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority, reproduced with the permission of Zvi Greenhut, Joseph Patrich, and Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah. Footnote 49

Although patchy, the archaeological evidence of banqueting spaces in Early Roman Palestine allows some provisional conclusions. First, all known oeci and triclinia were found in elite contexts, whether palatial, domestic, or civic. This differs from other cities of the Roman Empire, where triclinia also pervaded more public contexts, such as taverns, inns, tombs, and association buildings.Footnote 50 In general, it may be assumed that non-elite Jews often sat upright while dining.Footnote 51 Second, only a few Palestinian triclinia with stone benches resemble the nine-person Roman style, and these are all relatively early. Rather than copying this Roman style, Jewish elites more typically produced banqueting spaces that combined the Roman hierarchical organization of space with Greek and local spatial practices. Third, triclinia have usually been found in buildings whose decorative schemas and material culture betray cultural and economic interaction with other parts of the Roman world, whether Pompeii, Delos, Ephesos, or Tyre.Footnote 52 At the same time, however, Jewish elites tended studiously to avoid the iconographic mosaics, frescoes, fineware, lamps, and furniture that were integral to the dining experience in other parts of the empire. This particularity did not, however, prevent some Jews from associating triclinia with the greed and idolatry of gentiles.

Triclinia as Contested Spaces in Jewish Apocalyptic Texts

No surviving literary text from Early Roman Palestine uses the word triclinium.Footnote 53 However, several imply the sociospatial politics of triclinia, whether in the broad or narrow sense of the term. They do so through the language and imagery of diners reclining on couches, meretricious décor and luxury items, and/or a hierarchical seating order. In this section, I examine triclinium scenes in texts produced by Jewish elites or sub-elites in Early Roman Palestine.Footnote 54

The earliest Palestinian text that addresses the triclinium is arguably the Parables of Enoch (1 Enoch 37–71).Footnote 55 This text only survives in a Geʿez translation of a lost Greek version, but most scholars posit an Aramaic original.Footnote 56 While an Aramaic Vorlage of parts or all of the text cannot be excluded, there can be little doubt that the Parables was circulating in Greek soon after the turn of the eras.Footnote 57 Most scholars agree that this apocalyptic text was written by elite or sub-elite scribes sometime between the beginning of Herod’s reign and Jesus’s ministry. An allusion to the Parthian invasion of 40 BCE provides a terminus post quem. Another allusion to Herod’s visit to the hot springs of Callirhoe just before his death (4 BCE) appears in an interpolated section and thus supplies a terminus ante quem for most of the rest of the work.Footnote 58

The Parables of Enoch expands a prophetic critique of monarchy into an apocalyptic condemnation of the ruling class of Early Roman Palestine. Drawing on intertexts like Psalm 2 and parts of Isaiah, the text narrates Enoch’s visions of the Lord of Spirits and his messianic vice-regent, the Son of Man, securing redemption for the righteous in an impending age. This eschatological reversal of fortunes for the righteous entails the punishment and destruction of the ruling class—“the kings, the mighty, the landowners, and the exalted.”Footnote 59 When portraying the wickedness of this class, the text represents the triclinium space as a symbol of cultural abomination and economic exploitation:Footnote 60

And this Son of Man whom you have seen—he will raise the kings and the mighty from their couches, and the strong from their thrones…. Darkness will be their dwelling, and worms will be their couch. And they will have no hope to rise from their couches, because they do not exalt the name of the Lord of Spirits…. Their faith is in the gods they have made with their hands, and they deny the name of the Lord of Spirits. (46:4–7)

These verses constitute an interpretation of the oracle against the Babylonian king in Isaiah 14, where the Lord raises kings from their thrones (14:9). There is no word for “couch,” however, in the MT and LXX versions of Isaiah 14. Where Isaiah remarks that “worms spread out beneath you, and worms are your covering” (14:11),Footnote 61 implying the image of a bed and blanket, the Parables introduces “couches.”Footnote 62 The Geʿez term for “couch” here, meskāb, likely translated κλίνη.Footnote 63

As a representation of a banqueting space, this imagery of couches has several implications. First, the text uses couches to connect the kings and the mighty as a socioeconomic and political class: couches are part of a distinctive culture shared by royal and nonroyal elites. Second, this culture of banqueting on couches is connected to the economic exploitation of the “righteous”: the “ill-gotten wealth” (63:10: Eth. newāya ʿammaḍā, perhaps from μαμ(μ)ωνᾶς/ממונא)Footnote 64 of the kings and mighty was derived by exploiting the labor of the righteous (53:2). Third, the couches of the kings and mighty represent a culture of excess that is portrayed as foreign and idolatrous.Footnote 65 Not only do the kings and mighty not exalt the name of the Lord of Spirits while on their couches, but this denial is linked to the worship of foreign gods. These gods are deemed illegitimate because they were made by hand—presumably made from the gold and silver these elites accumulated by exploiting the righteous (52:7–9).Footnote 66 In the eschaton, the wealth of this ruling class will support the authority of the Son of Man (52:1–6), but the space of triclinia will transform into a death trap.Footnote 67 Triclinia will turn to worms.

Sometime between 6 and 30 CE, the elite or sub-elite author of the Testament of Moses advanced a comparable critique of the triclinium space.Footnote 68 This apocalyptic testament survives in a single late antique Latin manuscript based on a lost Greek version. A Semitic original is possible, but Johannes Tromp has demonstrated that a Greek original is just as likely.Footnote 69 The testament contains a periodization of Israel’s history that focuses on both the violent intrusions of foreign rulers and the corruption of national leaders.Footnote 70 According to this periodization, the eschatological age will begin to dawn in the author’s present time, when a ruling class will seek to replace the distinguished leaders the “petulant king”—that is, Herod—eliminated (6:2–6).

Chapter 7 of the testament castigates the Jewish priestly elites Rome empowered as the “ruling class of Judea” when it annexed the region to Syria in 6 CE.Footnote 71 Like the Parables of Enoch, it focuses on the triclinium space in its polemic:Footnote 72

And pestilent and impious men will rule over them [i.e., the people]…. They will be deceitful men, self-complacent, hypocrites in all their dealings, and who love to have banquets each hour of the day, devourers, gluttons, who eat the possessions of the (poor), saying they do this out of compassion … from sunrise to sunset saying: “Let us have luxurious seats at the table, let us eat and drink. And let us act as if we are distinguished leaders.” And their hands and minds will deal with impurities, and their mouths will speak enormities, saying in addition to this: “Keep off, do not touch me, lest you pollute me….” (7:3–10)

This passage employs terms that clearly invoke triclinia: “banquets” (convivia) and “luxurious seats” (a hendiadys: discubitiones et luxuriam).Footnote 73 Notably, the Vulgate uses the same terms to render πρωτοκλισίαν ἐν τοῖς δείπνοις (“first place at banquets”) in Luke 20:46 as primos discubitus in conviviis. Both texts refer to the spatial politics of seats of honor for distinguished guests in triclinia.

The testament portrays the space of triclinia in some of the same ways as the Parables of Enoch. First, it uses a luxurious banqueting culture to characterize the ruling class as culturally distinctive. Second, it ties the wealthy and luxurious lifestyle of elites to economic exploitation: the goods they eat (bonorum comestores) in their triclinia are the possessions of the poor.Footnote 74 The elite culture of eating is thus inseparable from economic processes of consumption. Third, the text presents the actions of these priestly elites as selfish and deceptive but also as causing them to become impure. The idea that their hands and minds will deal with impurities suggests that their participation in the culture associated with banquets is defiling. This implies foreignness and may allude to the use of imported vessels and foods. Given the testament’s aversion to idolatrous figural images (2:8–9), it may also assume pictorial representations in the space of triclinia.

The testament’s representation of triclinium space differs from the Parables of Enoch in noteworthy ways. For instance, the testament portrays elite dining without any mention of kings. These elites are portrayed as political and religious authorities. The testament’s conception of the triclinium thus imagines a setting like a peristyle mansion or the Banqueting Hall in Jerusalem, but not a palace. Additionally, the testament focuses on the cultural contest for prestige involved in seating in triclinia and is thus the earliest definitive literary evidence of hierarchical seating at banquets in Palestine. Finally, whereas the Parables envisions the eschatological abolition of triclinia, the testament is unclear about what will happen to triclinia when God’s kingdom emerges (10:1). Will the just leaders the text envisions as the counterpart to the priestly elites recline at luxurious banquets? Will all of “God’s people” recline in the kingdom, or will no one? The text provides no resolutions.

The earliest retrievable document from Jesus-following Jews in Palestine,Footnote 75 the Q source, builds on this apocalyptic tradition of denouncing elites by invoking the triclinium. This Greek “Sayings Gospel” has been reconstructed by scholars on the basis of the common material in Matthew and Luke, but not in Mark. Q was produced (perhaps in stages) by sub-elite scribes between the 30s and early 60s CE.Footnote 76 It almost certainly originated in the Galilee,Footnote 77 although a provenance in Judea cannot be excluded.Footnote 78 The text presents Jesus’s ministry as the inception of the kingdom of God, whose culmination will come with Jesus’s return as the Son of Man on an imminent day of judgment (3:7; 12:51; 13:18–19).Footnote 79 Much as the Parables of Enoch and Testament of Moses denounce politically powerful Jewish elites as evil exploiters of the righteous, Q portrays the Pharisees as the leaders of “this generation,” whose blood will be poured out at judgment (3:7; 11:50–51; 12:51; 13:28). It is these Pharisees who are responsible for exploiting and attempting to lead astray the “children of Wisdom” who have accepted Jesus’s proclamation of the kingdom. According to Q, Jesus’s teachings (as formulated in Q) contain the hidden things revealed to Jesus by God, unlike the teachings of the Pharisees, which have been transmitted by humans.Footnote 80 Through their self-legitimating teachings, the Pharisees have allegedly blocked access to the kingdom of God (11:52).

Q undergirds its claim that the Pharisees have prevented people from entering the kingdom by identifying other ways that they control space for their own benefit: “Woe to you, Pharisees, for you love the first place at the banquets, and the first seat in the synagogues, and greetings in the marketplaces” (11:43). This indictment utilizes the language of “banquets” (ἐν τοῖς δείπνοις) and “the first place” (πρωτοκλισίαν), or seat of honor, like the Testament of Moses to represent the space of triclinia. By associating triclinia with synagogues and marketplaces, Q indicates that the Pharisees’ pursuit of power and privilege was not limited to the relatively private space of banquets. Instead, this ambition materialized in synagogues and marketplaces, perhaps implying that these Pharisees were benefactors or leaders (e.g., ἀρχισυνάγωγοι) in the former and authorities (e.g., ἀγορανόμοι) in the latter. The mention of marketplaces (ἐν ταῖς ἀγοραῖς) is noteworthy because it situates the Pharisees in an urban economic space that Q associates with the condemnation of “this generation”: “To whom am I to compare this generation? And to whom are they like? They are like children seated in the marketplaces, who, addressing the others, say, ‘We played the flute for you and you did not dance; we mourned for you and you did not strike yourselves.’ ” (7:31–32)

Wendy Cotter has shown that the words “seated” (καθημένοις) and “addressing” (προσφωνοῦντα) here imply administrative officials in marketplaces.Footnote 81 As such, the language of marketplaces supports the text’s negative view of cities (10:12–16) and especially their gentile cultural and economic trappings (7:25; 12:29–31).Footnote 82

Q’s polemic against the Pharisees is thus a feature of its skepticism about aspects of Greco-Roman culture and urbanism, which threaten to make people “slaves to mammon” rather than “slaves to God” (16:13). Another woe illuminates these aspects of Pharisaic banqueting: “Woe to you, Pharisees, for you clean the outside of the cup and side-dish, but inside they are full of plunder and self-indulgence. Hypocrite, clean first the inside of the cup, and its outside will also be clean” (11:39–41).

On one level, this woe accuses the Pharisees of transgressing the ritual purity laws they professed.Footnote 83 On another, it describes the Pharisees as concerned with the appearance of their tableware. The term that I have translated as “side-dish” (παροψίς) is revealing, for it refers to a small plate for delicacies that accompany the main course (ὄψον)—in other words, for food eaten for gratification rather than sustenance.Footnote 84 Both the dish itself and the food served on it were probably imagined as foreign (e.g., kosher Spanish garum starters served on flashy red-slipped Eastern Terra Sigillata fineware).Footnote 85 Q declares that the use of these foreign luxuries conceals acts of robbery (ἁρπαγή) and self-indulgence (ἀκρασία), intimating that the Pharisees financed their culture of excess by exploiting the people.Footnote 86 Q’s final woe about the Pharisees weighing people down with burdens (11:46) points to labor exploitation in particular. Like the Parables of Enoch and Testament of Moses, then, Q conflates the triclinium space with economic exploitation, cultural difference, and religious transgression.

Unlike the previous texts, however, Q also uses dining space to define the kingdom of God as a banquet accessible to all. The Son of Man is said to have been accused of being a glutton and drunkard for “eating and drinking” with tax collectors and sinners (7:34). While not referring to a triclinium space per se, this saying portrays Jesus’s banquet as one in which those who are social outcasts are welcome.Footnote 87 The Parable of the Invited Dinner Guests (14:16–21, 23) elaborates on this theme by having a householder send his slave to invite dinner guests to his banquet, a cipher for the kingdom of God. Because they prioritized the pursuit of mammon, the invited guests all declined, provoking the host to open the invitation to anyone who would come. Another saying details the dining posture of those granted access to the kingdom: people coming from East and West “will recline (ἀνακλιθήσονται) with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of God, but you will be thrown out into the outer darkness, where there will be wailing and grinding of teeth” (13:28). Spatially, Q thus casts the kingdom’s insiders as a global community of diners reclining at an egalitarian banquet and outsiders as those people of “this generation” destined for eschatological punishment because of their obsession with wealth and status.Footnote 88

The Jewish texts from Early Roman Palestine examined in this section display a spectrum of perspectives on the triclinium. None of these sources approves of ranking at banquets, although they differ in the intensity of their reactions. Whereas the Parables of Enoch (late first century BCE) imagines the eschatological obliteration of triclinia, the Testament of Moses (early first century CE) does not comment on banqueting in the kingdom of God, and the Q source (mid-first century CE) envisions triclinia as spaces of commensality in the kingdom of God. Altogether, these trends might seem to suggest that the triclinium space was gradually appropriated by Jews, including the first generations of Jesus-followers, in Early Roman Palestine. But this unilinear model of acculturation obscures the struggles over the meaning of space evident when the archaeological and literary data are together subjected to critical analysis.

Triclinium Trialectics

Critical spatial theory offers a useful framework for analyzing the collective evidence for the social production of the triclinium in Early Roman Palestine.Footnote 89 The idea of spatial trialectics, in particular, proves valuable for complicating simplistic models of “Romanization” as acculturation. As Ray Laurence and Francesco Trifilò have recently remarked, this theory has “obvious applications” for understanding the relationship between the local and the global in the Roman provinces.Footnote 90

Trialectic is a term that was coined by the postmodern geographer Edward Soja to clarify the Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s theory of space.Footnote 91 According to Soja, every space consists of three interconnected aspects: Firstspace (physical space), Secondspace (perceived space), and Thirdspace (space as lived and experienced). As Christopher Meredith has noted, biblical scholars have found in Soja’s notion of Thirdspace a very convenient lens for interpreting the spaces in biblical texts, and the texts themselves, as spaces of social emancipation.Footnote 92 However, Soja’s Thirdspace is notoriously “slippery” since it “is claimed to encompass everything there is to say about anything.”Footnote 93 Moreover, as Meredith avers, Soja’s postmodern interpretation sanitizes the economic underpinnings of Lefebvre’s theory.

For Lefebvre, space is actively produced by society, just like commodities. Just as Marx theorized that social relationships become concealed and misrecognized in the production of commodities, Lefebvre asserts that social relationships (including class relationships) are latent in spaces.Footnote 94 Critical analysis of space, therefore, should resist reifying space as space “in itself” and instead focus on the dynamic social and economic modes and motivations of spatial production. Social space is not a singular and static thing, but an “unlimited multiplicity” of social spaces that become superimposed or interpenetrated. Therefore, “No space disappears in the course of growth and development: the worldwide does not abolish the local.”Footnote 95 Shifting modes of economic production entail the generation of new spaces rather than the dis- or replacement of spaces.Footnote 96

In order to analyze the ways that human actions produce spaces that reproduce and transform social relationships, Lefebvre proposed the “triple dialectic” that Soja conveniently called a trialectic. These human-made spaces are the “perceived space” of popular practices and perceptions that produce and reproduce space, the “conceptualized space” that is conceived and naturalized by official or dominant parties in society, and the “lived space” by which the dominated imagination “seeks to change and appropriate.”Footnote 97 Whereas Soja tends to portray Thirdspace as a space of radical inclusivity and revolutionary agency, Lefebvre’s trialectic theorizes “lived space” as much more of a negotiation between, or reconfiguration of, perceived and conceptualized spaces. It is through this “lived space” that embodied subjects bring about change in socioeconomic relationships.

A Lefebvrian investigation of the triclinium spaces in Palestine complicates models of Romanization versus indigenous anti-Romanization.Footnote 98 Whereas a Sojan analysis would view the archaeological evidence of triclinia as Firstspace, the Roman literary representations as Secondspace, and the Jewish texts as Thirdspace, thereby equating First- and Secondspaces with Romanization and Thirdspace with resistance, Lefebvrian analysis is more attuned to the hypercomplexity of changing conceptions of space as interpenetrations of the local and imperial. As Claudia Camp remarked about Soja’s Thirdspace, “oppressors also have lived spaces.”Footnote 99 Taking this critique seriously, analysis of spatial trialectics should also identify the “lived spaces” of elites.

The archaeological remains of triclinia in Early Roman Palestine evince some of the ways in which Jewish elites produced “lived spaces” that combined “perceived spaces” and “conceptualized spaces.” As we have seen, the Roman “conceptualized space” of the dining room as hierarchical started to influence the spatial production of Jewish kings and other elites in the first century BCE. When part of a palace or mansion, the Roman triclinium was the most intimate or private space in which a Roman host would entertain friends and guests. The dominant Roman conceptualization of the triclinium situates it on (or at least in sight of) the central longitudinal axis that ties together the public entrance (fauces and/or vestibulum), atrium, and peristyle courtyard. Whereas the clients of a paterfamilias would regularly penetrate this space as far as the atrium or tablinum (i.e., the room between the atrium and the peristyle that opened onto the peristyle), spaces of economic and political affairs, only family and friends would penetrate the house to the triclinium. From the entrance or atrium, the view of a guest or client would culminate in the nine-place triclinium, where the owners broadcast their distinguished relationships and advertised their wealth. Within this space, men and women were ordered according to rank, with the guest of honor and host occupying the privileged center of the conversation and enjoying the optimal point of view. This spatial organization expresses the Roman economic modes of friendship and patronage.Footnote 100

The “lived space” of Jewish elites did not match this Roman “conceptualized space.” Notably, the only three known triclinia definitively designed for nine people are those with masonry benches. Of these, one stood alone in a garden, one was added in a late phase to a peristyle mansion, but askew of the central axis and sightline from the entrance, and one was at the center of the peristyle courtyard and faced walls and another dining space. None of these were in urban contexts. The Roman conceptualization of space is more typically evident in the positioning of couches along three walls rather than four. As noted, even this conceptualization of space is better understood as a superimposition of Roman and Greek conceptualizations than as strictly Roman.

It is in decoration and material culture, though, that we glimpse Jewish elites intercalating Jewish spatial practices with Greco-Roman conceptualizations. Palestine’s triclinia were elaborately decorated with mosaics, carved stucco, and frescoes, like Greek and Roman triclinia. However, the Jewish decorative schemas eschewed figural images, in keeping with Jewish law (Exod 20:4), and instead displayed geometric and floral designs.Footnote 101 Some triclinia also made use of Hellenistic masonry-style wall decoration instead of the more colorful Pompeian styles. This style’s wall panels represented the ashlars with drafted margins so common in Herodian buildings and the Temple Mount in particular. In this light, this decoration style may be seen as a manifestation of local civic pride.Footnote 102

The material culture of elite dining also divulges Jewish elites negotiating spaces. Jewish elites used imported luxury items, foods, and wines while dining, and their demand for these items supported supraregional trade and thus economic integration.Footnote 103 However, they also used high-quality local items imbued with ethnoreligious significance. For instance, they used locally made stone vessels that some Jews would come to believe prevented ritual impurity.Footnote 104 They also used wheel-made (“Herodian”) oil lamps made from Jerusalem clay that were aniconic and may have been symbolically tied to the temple.Footnote 105 In these ways, Jewish elites produced triclinium spaces that were very much local and conveyed popular spatial perceptions.

If those spaces that conveyed the “Roman” or “Greco-Roman” were interpenetrated by particular, Jewish space, this turns the tables on typical understandings of Jewish (and proto-Christian) texts as reactions to Roman imperialism. The literary texts were not as concerned with anti-Romanization or counterimperial protest as they were with the particular production of space by local elites. This explains why local elites (kings and landowners, priests, and Pharisees) are the target of these literary polemics rather than the empire and imperial authorities. Each Palestinian text examined claims that the spatial practices of elites in triclinia were financed by economic exploitation. But these literary representations of elite dining spaces were produced by other elites or sub-elites in competition with their opponents.Footnote 106

Each literary text imagined the space of an eschatological kingdom of God that would reconfigure social relationships with different implications for the triclinium. Only the Parables of Enoch envisions the dissipation of triclinia at judgment. While Q expresses a similar dissatisfaction about the spatial practices of Jewish elites in triclinia, its vision of the emergent kingdom of God incorporates aspects of Greco-Roman conceptions of triclinia, such as invitations and reclining. Q’s understanding of the triclinium as “lived space” is not entirely inclusive, for it excludes slaves to mammon. It does, however, discredit the hierarchical conceptualization by inviting all types of people to the banquet.

Lefebvrian analysis detects the dynamic interplay of Jewish spatial practices and imaginaries with Roman (and Greco-Roman) conceptualizations.Footnote 107 This interpenetration of spaces had implications for the incremental incorporation of Palestine into the Roman Empire and its increasingly integrated economy. The incorporation of Greek and Roman conceptualizations of space was a cause and effect of Palestine’s integration into trade networks that traversed the Roman East—networks driven by elite demand for the types of luxury goods enjoyed in triclinia. At the same time, the Jewish practices that produced “lived spaces” enabled the emergence, spread, and habituation of Roman spatial conceptions through distinctive combinations with local perceptions of space. It was only through interpenetration with local, provincial spaces that Roman spaces and their concomitant social relationships materialized.

Conclusion

The Jewish spatial practices examined in this study reproduced elements of Roman social space but also asserted distinctive local identities. Much as Plutarch produced a triclinium space that imbricated Roman social codes with Greek significance, some Jewish elites produced aniconic triclinia in which diners reclined with imported and local vessels and others produced imaginary spaces in which the privileges of triclinium dining are accessible to many. The apocalyptic literary tradition that invoked the triclinium as a space of exploitation did not blame Rome for imposing this architectural form but rather harangued those Jewish elites responsible for producing these lived spaces.

Over time, the shock of the triclinium appears to have faded among Jews in Roman Palestine, but spatial negotiations did not cease. The archaeological evidence from the second and third centuries CE indicates that the triclinium remained a relatively uncommon architectural form enjoyed primarily by elites.Footnote 108 Instead of critiquing the social and economic implications of triclinium dining, however, the Tannaitic literature often affirms the hierarchical ordering of this space and imbues it with Jewish social and religious significance. For instance, Tosefta Berakhot (compiled in Palestine in the early to mid-third century CE) prescribes the Roman seating order as Jewish law:Footnote 109

What is the order of reclining (ההסיבה)? … When there are three couches (מטות), the greatest reclines at the head of the middle [couch] (בראש של אמצעית), the one second to him reclines above him (למעלה הימנו) and the third reclines below him (למטה הימנו), and they continue to order [the reclining] in this manner. (t. Ber. 5.5)

This fascinating halakhic endorsement of the Roman hierarchical order serves as support for the rabbinic power structure and consequently shaped rabbis’ hierarchical performance of Torah debate and exposition, as Gil Klein has argued.Footnote 110 This rabbinic text constructs the triclinium as a Jewish lived space devoted to academic discussions of halakhah among Palestine’s intellectual elite.Footnote 111

Much like the rabbinic texts, the proto-Christian authors who reworked the Palestinian Jesus traditions in new contexts across the Roman East also espoused, yet adapted, the Roman hierarchical ordering that was met with disdain and ambivalence by Jewish authors in Early Roman Palestine.Footnote 112 Luke’s Gospel, for instance, embraces ranking at banquets.Footnote 113 Like Plutarch, Luke entertains the question of precedence in seating by reflecting on a late-arriving guest:Footnote 114

When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not recline at the place of honor (πρωτοκλισίαν), in case someone more distinguished than you has been invited by your host; and the host who invited both of you may come and say to you, “Give this person your place,” and then in disgrace you would start to take the last place (ἔσχατον τόπον). But when you are invited, go and recline at the last place (ἔσχατον τόπον), so that when your host comes, he may say to you, “Friend, move up higher” (προσανάβηθι ἀνώτερον); then you will be honored in the presence of all who recline with you. For all who exalt themselves will be humbled and those who humble themselves will be exalted. (14:8–11)

While the Lukan Jesus encourages taking the “last” seat, nothing in this parable or the rest of the Gospel seeks the abolition of ranking in triclinia.Footnote 115 On the contrary, Luke legitimates social stratification as a means of exemplifying distinction in discipleship and humility (see 22:24–28), much as Tosefta Berakhot does as a means of exemplifying distinction in the interpretation of Torah and Plutarch does as a means of exemplifying distinction in παιδεία.

Both in Middle Roman Palestine and in the early Christian movement influenced by Jewish traditions, then, our literary sources communicate that the triclinium was no longer viewed as an architecture of elite exploitation. Instead, its concomitant hierarchical organization of social space was appropriated. Critical spatial theory reminds us that this embrace of the Roman hierarchical ordering of space should not be viewed as the replacement of local space with global space but rather as the trialectical production of new space through the combination of spaces. The social spaces described and prescribed by the rabbis and Gospel authors expressed local religious ideologies at the same time that they naturalized imperial conceptualizations of space.

When the full spectrum of ancient evidence is taken into account, it is clear that Jews in Early Roman Palestine negotiated space in similar ways. The archaeological remains, including material culture, betray Jewish elites imbuing the space of triclinia with local cultural and religious significance. While apocalyptic sources evince contestation over the cultural and economic implications of these elite spaces, they also divulge the production of imagined eschatological dining spaces where comfort and luxury are reserved for the righteous. The Q source is a striking example of the crossroads between apocalyptic condemnations of the dining practices of certain Jewish elites and the positive reconfigurations of such spaces in rabbinic Judaism and early Christianity. It condemns certain elites for their alleged labor exploitation, greed, and honor-lust but also envisions believers reclining at an eschatological banquet.

Importantly, the eschatological banqueting space illustrated in Q was not merely a vision but would have inflected the spatial imagination of its audiences. As R. Akiva put it: “This world is like a vestibule before the world to come. Prepare yourself in the vestibule, so you can enter the triclinium (טרקלין)” (m. Avot 4.16). The spaces envisioned in literary sources, whether this-worldly or otherworldly, informed and regulated the lived spaces of ancient Jews, if only in limited and indirect ways. Analyzing these literary sources together with archaeological data illuminates how the varied and dynamic negotiations and struggles of ancient Jewish elites contributed to provincial transformation.