Although Romanian musical composition did not reach a level of professionalism that would justify its inclusion in the universal canon until the mid-twentieth century, the period of experiment and synchronization with Western music, lasting from the early nineteenth century to the 1920s, is worthy of study. The seeds of its subsequent growth can be found in this period, although the focus on creating a national language adapted to forms borrowed from European classicism and romanticism did not allow the emergence of genuinely important figures in the field of musical composition.

The central idea of romanticism as articulated by Johann Gottfried von Herder – an interest in folklore and hence national character – was particularly influential within the cultures of the Slavonic nations:

Nowhere did the seeds of Herder’s cultural-linguistic nationalism fall on more fertile soil than in East Central Europe. His few words on the future of the Slavonic peoples were to become slogans of political nationalism in the eastern Habsburg territories, as they sought to forge independent national states modelled on the bourgeois national states of the West.Footnote 1

But the same ‘seeds’ also fell on the soil of the Romanian Principalities, Wallachia and Moldavia, which were unified in 1859. (Transylvania, the Banat and Bukovina, which were part of the Habsburg Empire at that time and had been generally more open to Western influences throughout history, would not be incorporated into the modern Romanian state until 1918.) After the 1848 revolutions, the Romanian nation, like the other young nations of Eastern Europe, underwent a process of cultural modernization. Like artists, writers and scholars, composers focused on the concept of the nation. The appropriation of folk sources seemed to be the first step towards defining a separate identity and creating a national canon in music, and there had been a few attempts in this direction in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Greek-Oriental versus Western Music

Romania’s nineteenth century was not so much ‘long’ as it was delayed, its parameters marked by the rebellions of 1821 and one end and the beginning of World War I in 1914 at the other. Situated at the intersection of Ottoman, Russian and Austrian interests, by 1821 the Romanian Principalities had experienced a century of Phanariot rule. Named for the Greek Phanar district of Istanbul, whence they originated, the Phanariot rulers were controversial: the 1848 revolutionaries vehemently opposed them, seeing their rule as ‘the explanation for our lagging behind Europe culturally and for our corrupted morals’.Footnote 2 On the one hand, the Phanariots imposed Byzantine customs and Greek as the language of culture and official documents, on the other hand, they governed efficiently and took pains to modernize the Romanian Principalities. But this epoch was to end with the anti-Ottoman and anti-Phanariot movements of 1821. Local rulers were re-established, appointed by the sultan, albeit under the close supervision of the Russians. There followed a difficult period, involving numerous challenges, but this was quickly left behind and the transition was made from an oriental lifestyle to Western European values.

The speed at which Romanian society synchronized with wider European events significantly increased, and by 1848 the Romanians were part of the European revolution. The same simultaneity at the level of historic time can be perceived in the process whereby the modern nation states of Germany, Italy and Romania crystallized.Footnote 3

In the early nineteenth century, the transition from a Greek-oriental to a Western typology is detectable chiefly in the literary language, which evolved more quickly than the musical one. Soon after 1800, the Romanian language was introduced in schools and in Byzantine church music (alongside Greek) and underwent an evident process of modernization that was to be felt in literature in particular.

The temporal boundaries of nineteenth-century European music are also flexible, marked not by years but by landmark works: Beethoven’s late works, Rossini’s operas and Schubert’s lieder at one end and the emancipation brought by Arnold Schoenberg’s dissonance, at the other.Footnote 4 For Romanian musical culture in the Principalities, music at the beginning of the nineteenth century was dominated by folk and Byzantine characteristics, marked by oriental and Turkish influences and faint hints of secular ‘cultured’ music (the worldly and courtly songs composed by some boyars). In Transylvania, contacts with the Western musical style were more frequent, via German and Austrian musicians temporarily resident at the princely courts (for example, Michael Haydn and Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf). Likewise, thanks to the greater mobility of Western musicians, Italian, German and French opera companies, and foreign concert performers, cultural links to the West became stronger around the year 1820. Previously, the influences of Greek-Turkish culture had been prevalent, with local music mainly represented by itinerant folk musicians (lăutari) and church cantors.

This new-found receptivity towards Western music was due to the wish of some boyars to introduce Western sounds to local salons and to keep abreast of innovations in contemporary composition. But such attitudes did not yet prevail over local music-making customs of the Orthodox Church, the princely court, the Turkish bands such as the mehterhane, or the widespread lăutar ensembles. Pianos were purchased by amateur salons and Western music textbooks were imported, but several decades were to pass before there was what one might call Romanian composition in the Western sense. And those who were to help found ‘national’ composition would be foreign (mainly Austrian) musicians who had settled in the Romanian Principalities.

While foreign travelling opera companies were predominant in shaping the public taste, the impact of Western music was not limited to such companies, but was augmented by greater commercial links with the West, as well as to the increase, after 1829, of young Romanian men travelling abroad to study in major European cities (Vienna, Berlin, Leipzig, Paris, Pisa), and bringing new perceptions and models back with them. The foreign artists residing in the Principalities also fostered such links. If the boyars (and the then-emerging bourgeoisie) had access to operas and classical concerts, the greater part of the population was familiar with the repertoire of the 1830s bands, which played potpourris of opera, marches and dances.

The first manifestations of local ‘cultured’ composition were associated with the theatre, in the form of stage music, political couplets and melanges on national themes, which revealed a patriotic, historical spirit typical of early romanticism; the works of Josef Herfner (1795–1865), who was born in Pressburg (now Bratislava) are good examples. At the same time, the importance of the local operetta companies was symbolically marked by the first Romanian vaudeville, Triumful amorului (The Triumph of Love), by Ioan Andrei Wachmann, performed in Bucharest in 1835. Wachmann adopted a genre that was regarded as supremely French, but which at the time was widespread in Europe and was received with great enthusiasm in Romania up until the end of the nineteenth century.

The urge to synchronize with Western cultural forms was visible in the emergence of institutions of music education (that the first music school in Bucharest was not founded until 1833 is an indication of the very low level of music education), in the beginnings of music criticism and historiography, and in the study of folk music. The interest in folk music is demonstrated by the various Romanian collections published in the first half of the century. Of course, it is not possible to speak of any academic rigour in the collection of folk melodies: Romanian peasant music would not be studied using suitable tools and methodologies until the beginning of the twentieth century, in the studies of scholars such as Belá Bartók and Constantin Brăiloiu. Rather, the various collections of piano miniatures that began to be published at the time (under the general title Romanian National Arias) were eclectic in expression, combining urban folk music with sources of inspiration taken from popular foreign melodies (French chansons, salon music, Russian ballads), and quite often the line between ‘folk’ and ‘cultured’ music was unclear.Footnote 5

The emphasis that writers and musicians placed on the national cultural ‘spirit’ gave rise to a desire to study folk music, as also occurred as part of the emancipation of every other East European national school. The affirmation and fostering of folk music meant paying homage to folk creators and adapting their oral traditions to the Western manner of written composition. However, for almost a century, the price of this adaptation of folk music was the loss of many of the music’s essential features: monody, microtones, modal complexity and asymmetrical rhythms, were all subsumed under Western harmonic and rhythmic norms.

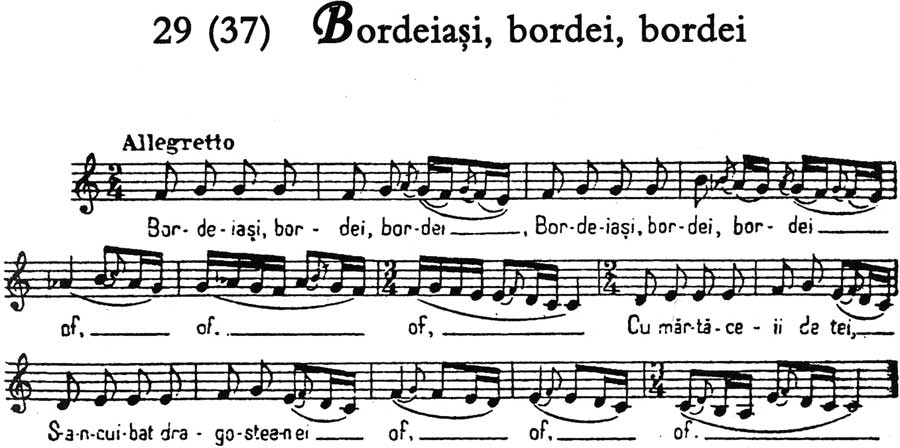

Historians of nineteenth-century Romanian music have surveyed the contributions of composers such as Anton Pann, a reformer of psaltic chant and collector of literary and musical urban folk texts of Eastern influence. Pann was the first musician to transcribe not only texts but also music in his folk collections. Indeed, he was not averse to altering the melodies he collected, ‘correcting’ or re-working them. Typical of his published songbooks is Spitalul amorului sau Cîntătorul dorului (The Hospital of Love or the Singer of Yearning), which includes village songs, Balkan melodies and ballads, songs of the mahala (artisans’ quarter), and melodies flavoured by Italian opera that were fashionable in the towns at the time (see Fig. 1).Footnote 6

Fig. 1 Anton Pann, Bordeiași, bordei

The beginnings of national composition in Romania (as also in Russia, Poland, Finland, Hungary and other lands) is indebted to foreign composers and instrumentalists. The presence of foreign musicians, especially Austrians, whether as members of orchestras or music teachers, is attested by documents dating from the eighteenth century. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the most important composers were Alexandru Flechtenmacher, the author of the first major orchestral work (The Moldavian Overture, 1846), Ioan Andrei Wachmann, who shared with his colleagues a predilection for stage music (operettas, vaudevilles) and collections of tonally harmonized folk melodies, Ludwig Anton Wiest (1819–1889), who was concerned with creating a Romanian chamber repertoire (particularly for the violin), and Carol Miculi, a student of Chopin and gifted composer of piano pieces that adapt Romanian folk melodies.

After 1821: From East to West, with Nationalist Tunes

Looking at Romanian composition in the first half of the century (up until 1859, the year of the unification of the two Romanian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia), it is obvious that musicians were exploring ways to synchronize with European composition, while trying to harness the potential of Romanian folk music. Intellectuals of the time, and writers in particular, shared the same outlook. For example, observing the success of the Italian opera companies based in Bucharest and Iaşi, Ion Heliade-Rădulescu wrote that ‘only Italian theatre can be a good model and a true teacher for national theatre’.Footnote 7 Most writers consistently advocated the collection of national songs in their musical essays and reviews:

In an epoch such as this, when our countries must fight powerful enemies who strive to cast into darkness not only our political rights, but also our nationality, folk poetry will be of great help in defending it, because however great the manifestos of the Petersburg cabinet might be, Romanians will remain Romanians and will prove that they are Romanians through their language, traditions, customs, image, songs and dances.Footnote 8

Vasile Alecsandri, the author of these lines and without doubt one of the foremost figures in Romanian literature, was inspired by the nationalism of 1848. He had an idyllic vision of the Romanian village as a product of the folk spirit and imagination. Nor were his musical counterparts indifferent to folk music; they tried to integrate them into the new theatrical genres they enthusiastically tackled. Vaudeville was a favourite genre, with its satirical themes drawn from Romanian current affairs, and its simple, dynamic plots, which alternated musical and spoken scenes. To this French genre, composers added elements of Romanian folk spectacle,Footnote 9 and it is difficult to find the dividing line between vaudeville, melodrama, and military, national or comical chansons in the works of Alexandru Flechtenmacher, Ioan Andrei Wachmann and Ludwig Anton Wiest.

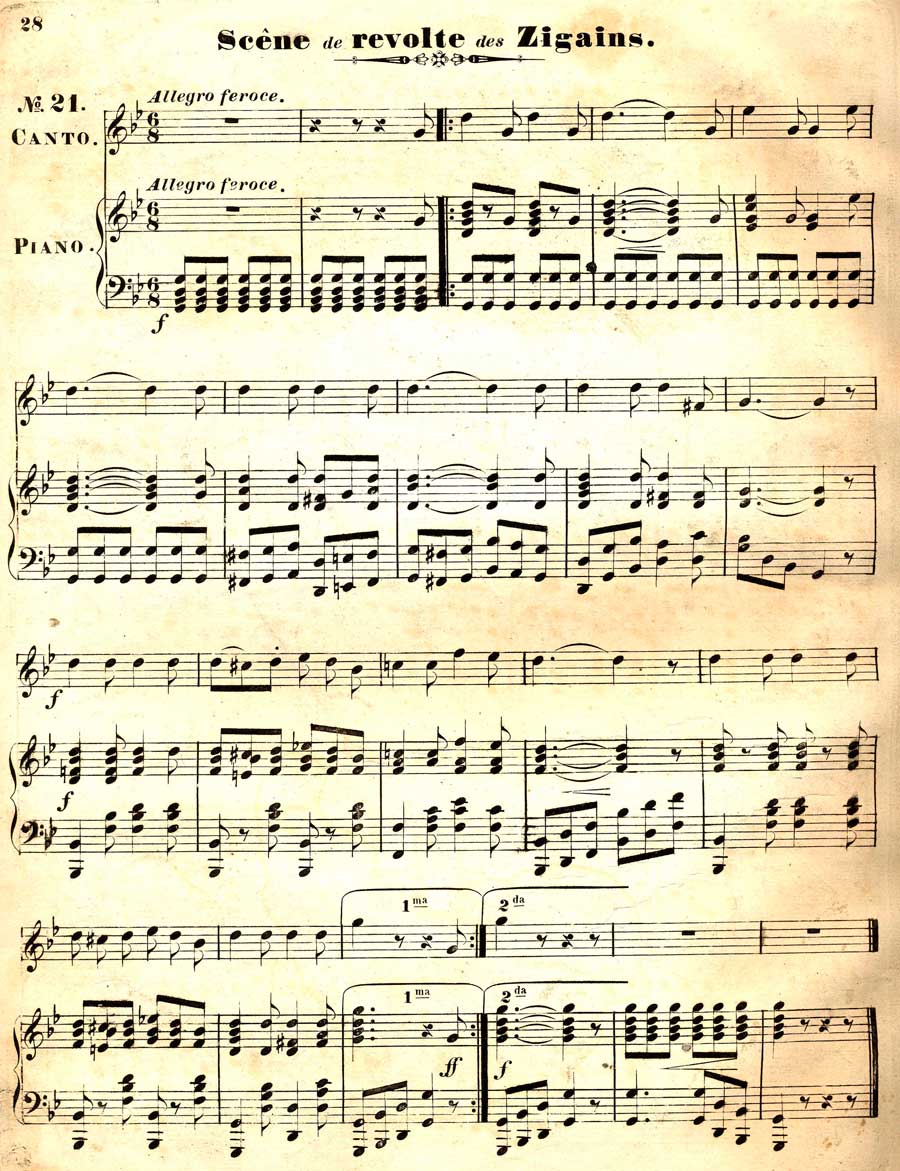

Even Romanian opera might be mistaken for vaudeville. In any event, the first work for the stage characterized as an ‘operetta-enchantment’ was by Flechtenmacher (Baba Hârca [Rawhead and Bloody-Bones], with a text by Matei Millo, 1848) and had the dimensions and appearance of a vaudeville (see Fig. 2). After 1850, Flechtenmacher and Wachmann continued to write serial operettas, following the same pattern: ‘each operetta would have an overture, numbers various in form and genre, and choreographic and choral scenes’.Footnote 10 Clichés abounded, as did copying from other composers: entire pages were lifted from Giacomo Meyerbeer.Footnote 11

Fig. 2 Alexandru Flechtenmacher, Baba Hârca: ‘Scène de revolte des Zigains’

Other stage genres, such as ballet and opera, were yet to make their debut in Romanian composition. The few fragments of Wachmann’s sparse attempts to write an opera that have been preserved suggest the influence of Romantic Italian melodrama, as well as the composer’s desire to create a national canon using local historical and mythological themes (Mihai Bravul în ajunal bătăliei de la Călugăreni [Michael the Brave at Călugăreni] and Mesterul Manole [Master Builder Manole]Footnote 12 ).

Professional choral works first appeared around 1850, and towards the end of the century they became the favourite genre of Romanian musical life, surpassing works for the stage in popularity. A certain romantic Zeitgeist marked the beginnings of Romanian choral music. We might also think of Germany, for example, where romantic nationalism stimulated a rebirth of choral composition, although it was now secular, rather than religious as it had been earlier. Choral works served either purposes of entertainment, with amateurs taking delight in meeting together to make music, or social functions, as in mass choral festivals: ‘social singing on a cosmic scale that provided European nationalism with its very hotbed’.Footnote 13 In Romania, choral singing had previously belonged almost exclusively to the Orthodox Church, and a type of monodic chant prevailed, as well as oriental scales. The influence of German chorales filtered through, thanks to Flechtenmacher and Wachmann, while harmony and homophony would transfigure Byzantine music in the second half of the nineteenth century, under the strong influence of Russian ecclesiastical chant.

But around 1850 Romanian composers developed an interest in patriotic songs. La Marseillaise and Carmagnole were widely heard, and Flechtenmacher wrote some patriotic songs that became very popular. For example, Hora Unirii (The Ring Dance of Unification,Footnote 14 Fig. 3), composed in 1856, can still be heard today, particularly on 24 January, when the unification of Wallachia and Moldova is commemorated. At school, children still learn Flechtenmacher’s anthem, which is included in the textbooks.

Fig. 3 Alexandru Flechtenmacher, Hora Unirii

Let us not forget that the current Romanian national anthem, Deșteaptă-te, române (Romanians Awake; lyrics by Andrei Mureşianu, set to a melody of unknown authorship), was written in 1848. Patriotic songs, ballads, national arias, and lieder constituted an eclectic, easily performed repertoire, in which all the preferences of the time were combined: German lieder, French chansons and Romanian urban ballads with a strong oriental flavour.

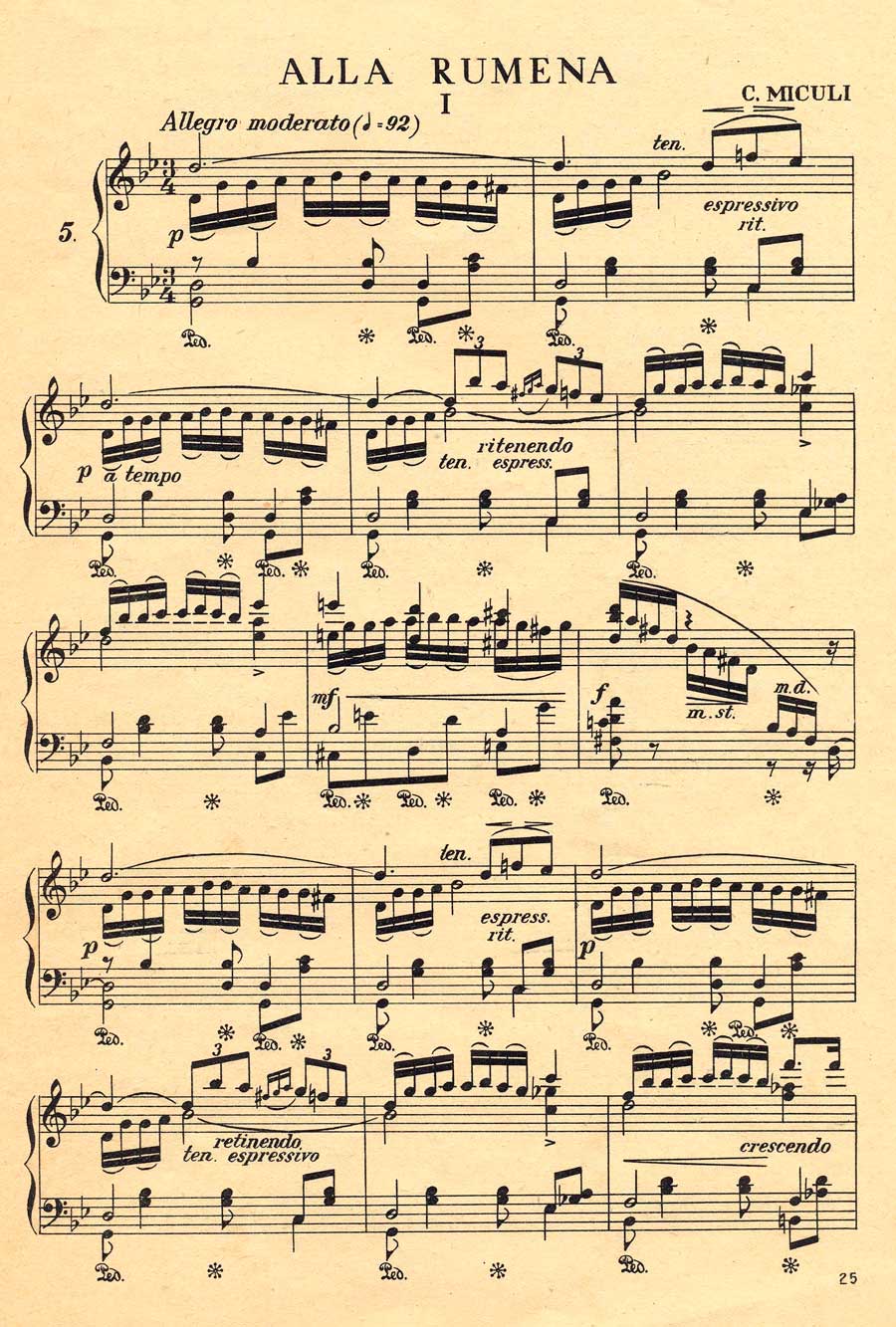

Similar combinations, but with the balance tipping towards the national side, may also be found in the genres of instrumental music. The first Romanian compositions for piano were nothing more than arrangements of folk tunes, fulfilling the function of salon music. The transition to original compositions that hinted at Romanian folk tunes was made by a student of Chopin, Carol Miculi. In his cycle of 48 airs nationaux roumains, Miculi hit upon the idea of adapting Romanian songs to miniature forms and genres (the impromptu, prelude, polonaise, mazurka, waltz, and so forth; see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Carol Miculi, Alla Rumena

Similarly, Flechtenmacher opted for another fashionable romantic model, that of Liszt’s paraphrases, when he wrote his Introduction et variations sur des motifs de l’opéra Norma de Bellini, pour violon avec accompagnement de quatuor (Vienna, 1840), while Wiest went in the opposite direction, from European classical music to Romanian folklore, when he wrote his Hora clasică aranjată pentru pian și vioară după Sonata de Clementi (Classic Ring Dance Arranged for Piano and Violin after Clementi’s Sonata), op. 46.

Orchestral pieces were not numerous, as symphonic writing techniques were still crude given the lack (up to 1860) of any permanent orchestra that might have helped composers to experiment. Many scores have been lost, and those that have been preserved merely give us the sense of a new direction: for instance in Flechtenmacher’s Moldavian Overture (1846), an unconventionally (or perhaps clumsily) constructed type of sonata form is combined with a folk quotation. Wiest attempted to write a Concert pathétique for Violin and Orchestra (1852), which is a rather flimsy response to Liszt’s Concert pathétique (1850). In all these examples, a preoccupation with striking a balance between European and national ingredients may be observed.

In ordinary speech, two types of music have been distinguished: ‘German’, a word used since the eighteenth century, which referred to European music, and ‘national’, which came into use around 1840 and refers to those works that employ Romanian folk songs.Footnote 15

Such a vision of ‘German’ versus ‘Romanian’ music was to become increasingly dominant, and it led to a number of firsts in national composition during the second half of the century.

Premieres of Romanian Music

After the unification of the Principalities, in 1859, the new state rapidly began to close the gap by which it lagged behind modern Europe. The short reign of Alexandru Ioan Cuza (1859–1866) took unification as its main goal: Cuza had been appointed ruler thanks to various cunning political machinations by both Moldavians and Wallachians, and Romanian statesmen were scouring Europe for a prince willing to occupy the Romanian throne. They finally settled upon Carol of Hohenzollern, a member of the imperial Prussian family. After his enthronement as Prince Carol I in Bucharest, and the passing of the new constitution in 1866, the new state was thenceforth called Romania. In the 48 years of Carol’s reign (he was crowned King of Romania in 1881) new laws and institutions fostered a modern state, and an avowedly Francophile society emerged that was in step with the latest European developments but also cultivated local traditions.

In terms of the influence of European music on Romanian, the period that began in 1859 was more interesting than the first half of the nineteenth century. (This is also true of literature, philosophy and the sciences.) The composers of the period have gone down in national history merely for writing the first Romanian symphony, the first Romanian string quartet, the first Romanian opera, and so on, even though such firsts do not necessarily possess aesthetic value. But they did pave the way for a ‘national language’ adapted to genres borrowed from contemporary European music. Often, the results fall short of the composers’ laudable intentions, and Western forms were still incompatible with the local modal system. Attempts to solve these problems were most successful in choral music, where the straightforward musical structures facilitated the attempts to adapt traditional modal melodies to Western harmony.

Otherwise, progress in Romanian composition was largely technical,Footnote 16 though composers also benefitted from exposure to such outside influences as classical romanticism of Felix Mendelssohn, the Russian choral tradition, and the mediaeval modal system promoted by the Schola Cantorum (where many Romanians studied at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth centuryFootnote 17 ). On the other hand, the interest in folk music, which was at first manifested in arrangements, prepared ‘the soil in which many of the principles for the treatment of folklore germinated’.Footnote 18

After a phase marked by idyllist conceptions, scholastic realization, rhetorically inconsistent content, and an amateur or, at best, semi-professional environment, a Romanian ethos gradually asserted itself in vaudevilles, operettas and operas (most of which were on historical-patriotic themes). The development of instrumental, chamber and symphonic music in the last quarter of the century resulted from several factors, including the increase in available musical instruments (especially pianos) and the resulting increase in people who could play these instruments, a rise in the general level of musical culture, the founding of state conservatories in Bucharest (1864) and Iaşi (1836), and the establishment of the first permanent symphonic orchestra (in the 1860s) and string quartet (in the 1880s). At the same time, the first choral associations fostered choral music, regularly holding concerts (beginning in around 1880).

Synchronization with Western music and promotion of the national character remained the two guiding principles for composition, although this showed patchily in Romanian scores. The first symphony was composed by George Stephănescu, a musician who had studied in Bucharest with Wachmann and in Paris with Ambroise Thomas and Daniel Auber, assimilating classical and romantic ideas, in particular from Mendelssohn. Stephănescu wrote his Symphony in A major (1869) while still a student at the Paris Conservatory, practising with a Haydn-style orchestral apparatus. His symphonic discourse in Uvertura naţională (National Overture, 1876, Fig. 5) was more sophisticated, combining the epic with folksong nuances in sonata form.

Fig. 5 George Stephănescu, Uvertura națională

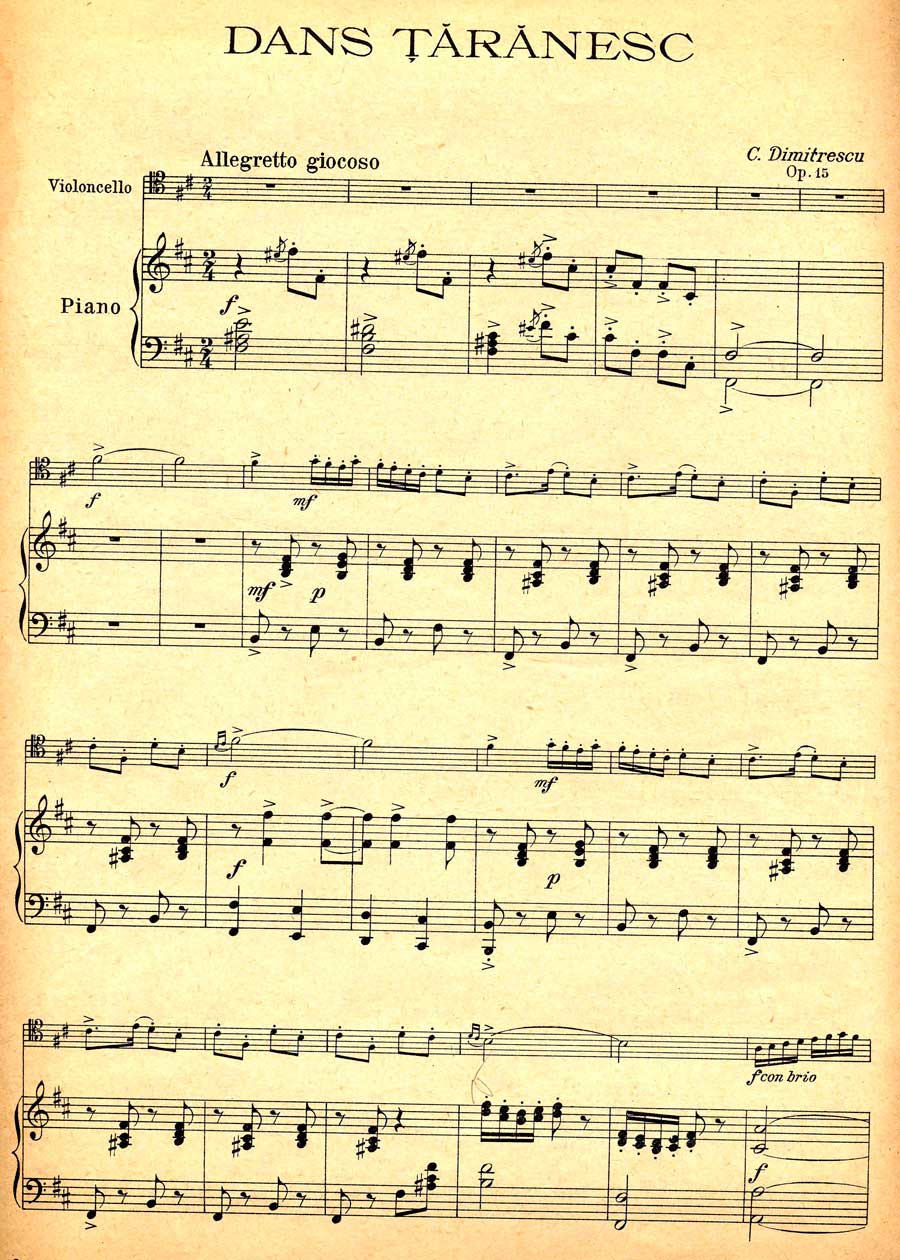

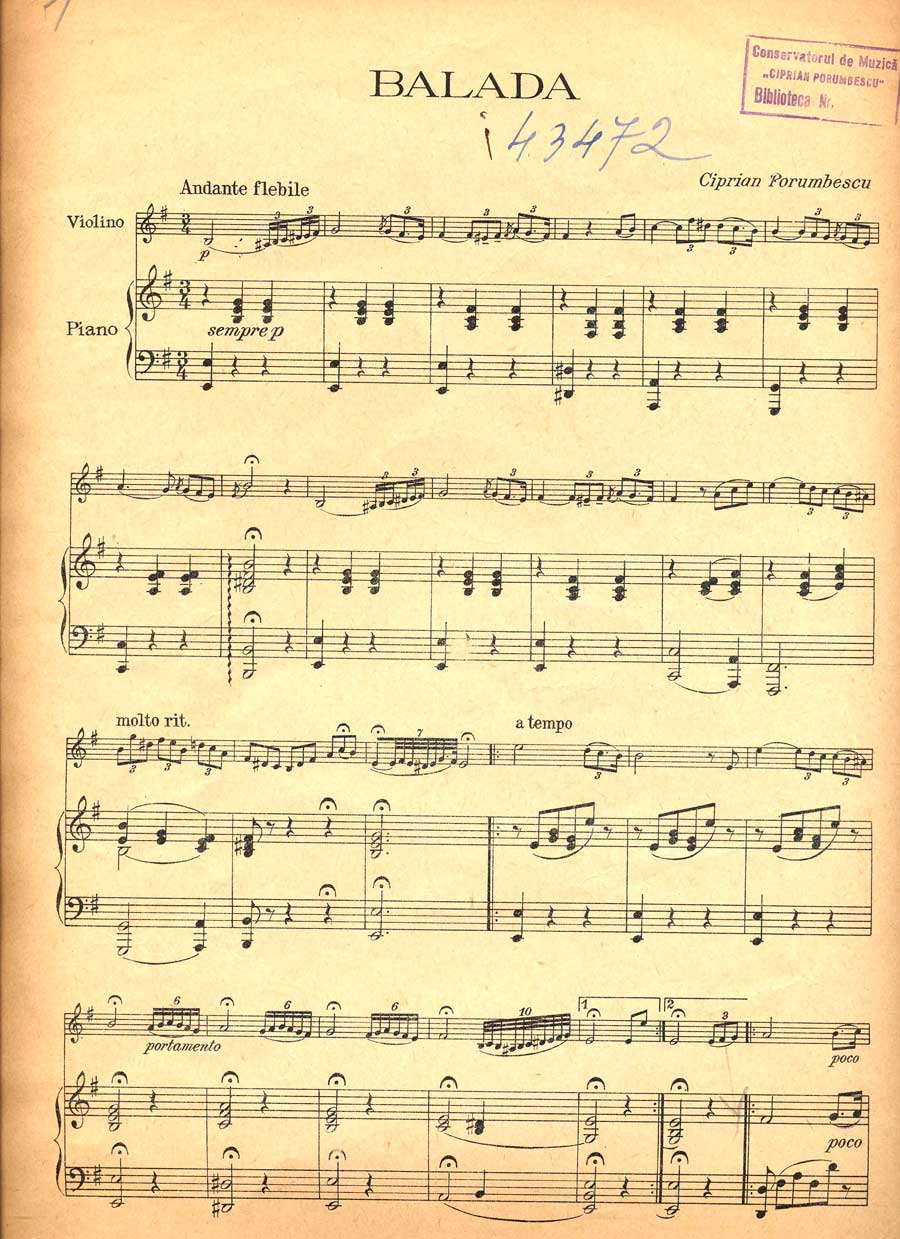

Constantin Dimitrescu was the first to attempt chamber and concerto compositions with the cello as the lead instrument. Inspired by Haydn and German romanticism in his string quartets and cello concertos, he was the only composer of instrumental concertos during this period. His three scores for cello are reminiscent of Camille Saint-Säens and Antonin Dvořák, and his Dans țărănesc (Peasant Dance, Fig. 6) for cello and piano (1893) can still be found in the repertoire of young cellists and today enjoys the same level of popularity as the Balada for violin and piano (1880) by Ciprian Porumbescu (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 6 Constantin Dimitrescu, Dans țărănesc

Fig. 7 Ciprian Porumbescu, Balada

It was Stephănescu who first tackled the genre of the instrumental sonata, while Dimitrescu wrote a series of seven string quartets (1883–1923). But the composer who truly established Romanian quotations within the European chamber and symphonic repertoire was George Enescu (1881–1955), who made his debut as a young man in the closing years of the nineteenth century.

While instrumental music got off to a slow start, choirs were very popular. Miniatures, madrigals, choral poems, and choral concertos commemorated historical events or described local landscapes. Introducing a new type of choral music in Iaşi, Gavriil MusicescuFootnote 19 reworked peasant folk music within the framework of a tonal system coloured by modality. The influence of the so-called ‘Russian Five’ or ‘Mighty Handful’ was noticeable in his efforts to collect, transcribe and suitably harmonize Romanian folk songs in a manner that was to be viewed as completely ‘wrong’ by some of his contemporaries, educated in the spirit of Western tonality. Moreover, Musicescu was also interested in harmonizing Byzantine religious songs, according to the Russian method he had studied in St Petersburg (1870–1872, see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Gavriil Musicescu, Pre tatăl

A local dimension was to leave its mark on choral music by Transylvanian composers, such as George Dima and Iacob Mureşianu, and composers from Bukovina, such as Ciprian Porumbescu. One may observe an interest in Romanian folk music in Dima’s lieder,Footnote 20 on the one hand, and an emphasis on accessibility and the educative and patriotic role of choral music, particularly in works by Mureşianu and Porumbescu, on the other.Footnote 21 The same predilection for the choral genre may be observed in musical works from a different geographical area, the Banat, represented by composer Ion Vidu.

The founding of a national opera as an institution and a musical genre became a true obsession towards the end of the nineteenth century and was reflected as such in the contemporary press.Footnote 22 After 1865 there was a fall in the number of vaudevilles produced; on the other hand, Ciprian Porumbescu’s operetta, Crai nou (New Moon, 1882), entered the history of Romanian music as the first work in that genre. Opera projects were plentiful, although many have been lost, while others were never finished. Eduard Caudella’s historical drama Petru Rareş (written in 1889, staged in 1900), which combines the grand-opéra style with the symphonism of German opera and the colour of lăutar folk music, marked the birth of national opera.Footnote 23 Romanian music historians have compared the work with other pioneering operas from Central and Eastern Europe: Ivan Susanin, Halka, Dalibor, The Bartered Bride and Bánk Bán. Moreover, it has been said that although Eduard Caudella remains unknown in Europe, there are no significant differences between him and Franz Erkel or Stanislav Moniuszko.Footnote 24

Each European national musical school has a prominent, pioneering, romantic figure, be it Glinka or Smetana, or Chopin or Liszt. But this was not the case in Romania, at least not until George Enescu, most of whose work was composed in the twentieth century. Composers before Enescu endeavoured to tick the boxes of the genres and forms of Western music, each to the best of his ability: Musicescu, Dima and Porumbescu excelled in the choral field; Stephănescu and Dimitrescu favoured an instrumental, symphonic discourse; Caudella and Stephănescu consolidated their reputation in works for the stage, and so on. But none of them rose above the others to dominate the musical scene.

In one way or another, each of these composers took part in the debates on ‘national’ music. Some used the epithet ‘national’ in the titles of their works merely because they employed quotations from folk music. But such quotations, inserted into Western formal patterns, do not guarantee that a national musical school will be viable or original. Other composers, proponents of universal music, put forward an Italian model, regarding Italy as more akin than Germany, given the Romanians’ Latin heritage.

In any event, as a result of historical circumstances, in the nineteenth century that Romania moved towards Europe. And although the move was due in large part to a German king, Carol I, and the pioneering efforts of Austrian and German musicians, Romanian society remained primarily Francophile. Two case studies – Liszt’s tour of 1847 and the music scene in Bucharest around the year 1900 – will reveal the various European accents of the country’s music.

Franz Liszt’s Tour and its Possible Effects on Romanian Composition

In the nineteenth century a number of famous European composers and performers made concert tours of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia that were celebrated at the time and for long afterwards. Franz Liszt, Joseph Joachim, Johannes Brahms, Henryk Wieniawski and Pablo Sarasate were the most important of these, and their visits to Romania are linked with several romantic myths. Details of Liszt’s tour provide a good glimpse of the ideas currently circulating in the musical scene of the time. Liszt’s emphasis on the national spirit, through folk quotations reshaped as rhapsodies, ought to have inspired Romanian musicians; let us see whether this was what happened.

Liszt’s tour of Transylvania began in Timişoara in November 1846, continuing in other musical centres of Transylvania, before moving on to Bucharest and Iaşi. The audience’s enthusiasm for the virtuoso (who travelled with his own concert piano) seems to have been fostered by their admiration for his progressive ideas at a time when the revolutionary spirit of 1848 was beginning to emerge. In Hermannstadt (now Sibiu), Liszt began to collect folk quotations for a rhapsody, among them a theme from a horă (ring dance) called the Hermannstädter. This rhapsody remained obscure until the early twentieth century, when Belá Bartók found it in a volume of 16 rhapsodies at the Liszt Museum in Weimar, and brought it to the attention of Romanian musicologist Octavian Beu in 1930. Beu located the original (the Liszt Museum possessed only a copy), and the piece was first performed in Romania by pianist Aurelia Cionca on 17 December 1931 and published by Universal Edition in 1936.Footnote 25

Liszt’s notebook from his tour, in which he wrote down the various songs he heard, has been preserved. Clearly inspired by their folk ‘exoticism’, Liszt drew upon the melodies he collected in his improvisations: the press reported that he played ‘variations on old Romanian arias’.Footnote 26 These melodies probably contributed to the final version of the score for Rhapsody no. 20, which is full of folk quotations. Liszt also recorded numerous Hungarian songs, especially from Transylvania, where he requested that he might listen to bands of folk musicians. He was obviously fascinated by the art of the lăutari, and Romanian historiography fondly recounts the episode of his meeting with Barbu Lăutarul.Footnote 27

To return to his main tour of Transylvania and the Romanian Principalities between 1846 and 1847, setting aside the flamboyant performances of Liszt the pianist and the sentimental narratives surrounding him, we must ask ourselves whether the tour had any impact on local composition, at the beginning of its process of Europeanization. Liszt’s compositions, with the exception of those included in his popular repertoire, were still unfamiliar to Romanian audiences (whose taste had been shaped by Italian travelling opera companies). Liszt wrote his first Rhapsodie hongroise in 1846 – the year of his tour – and his incorporation of folk music into concert scores would thus not have been heard by Romanians during this tour. But his incorporation of folk melodies in his improvisation during the tour sparked aesthetic debates on the appropriation of folk melodies in classical music. Some writers (fascinated by oral creation) supported the possibility of adapting Romanian folk songs to an occidental type of music, while others rejected the idea.Footnote 28 It was not until 1920 that a similar debate would lead to the definition of an individual voice in modern Romanian composition.

Liszt’s model seems to have been less significant to Romanian composers active in the second half of the nineteenth century than it was to Poles or Czechs.Footnote 29 Nonetheless, there were a few tentative attempts to write rhapsodies in the style of Liszt: Ciprian Porumbescu’s Romanian Rhapsody, originally composed for piano in 1882, was subsequently orchestrated. Zdislaw Lubicz (1845–1909), a Pole based in Bucharest, wrote other Romanian rhapsodies for piano. There were also clumsy attempts to write a symphonic poem after Liszt’s model: George Stephănescu composed Six National Round Dances, which were miniature symphonic poems with programmatic titles and folk inflections.

Audience tastes … were not very sophisticated and had a negative impact on local compositional interests …. Thus, if a piece employed an advanced language close to the contemporary one, although Wagnerian chromaticism and Franckian symphonism were not employed, but rather a style that whose sources may or may not have been identifiable in the work of Schumann, Weber, Berlioz or Liszt in rhapsodies, it was considered too bold, too advanced.Footnote 30

Only the first major figure in Romanian composition, George Enescu, was evidently interested in Liszt’s suggestion regarding rhapsody as a formula for national composition. Romanian musicology has still not sufficiently investigated the impact Liszt had on the style of the young composer in Romanian Poem, op. 1 (1897) and, in particular, the two Romanian Rhapsodies, op. 11 (1901).

The fact that the Brahms–Enescu relationship has been often discussed seems curious … whereas the Liszt–Enescu relationship has rarely been analysed …. Enescu’s relation to the folk music of his country (particularly Moldavian and Wallachian folk music) differed in intensity from, for example, the connection between Liszt and Hungarian folk music. Or to be more precise, it was more intense than that of a French composer writing a Norwegian rhapsody, a Russian musician writing a Spanish caprice or a Belgian inspired by Romanian folk music.Footnote 31

Another possible parallel might prove interesting. Liszt believed that it was Gypsies who created authentic Hungarian folk music; this is therefore where the sources of his folklorism in the Hungarian Rhapsodies lie.Footnote 32 The same romantic belief that Gypsy fiddlers were the true keepers of folk music can be found in his reported admiration of Barbu Lăutaru. Enescu never systematically collected folklore, unlike his contemporary, Bartók. The nuances of Romanian folklore in his music also come from such fiddlers, from the emotional memory of a musician who, as a child, had admired the lăutari. Enescu only rarely quotes folk music (in passing in the Rhapsodies) and prefers to recreate melodies in a folk style, as he does for example in the Sonata no.3 ‘dans le caractère populaire roumain’ (1926). Liszt’s impact on Romanian composition was delayed and is detectable only after thorough analysis. His influence corresponds to the two Romanian obsessions in the nineteenth century: synchronisation with Europe and nationalism.

Musical Bucharest around 1900

The most interesting period of the nineteenth century was undoubtedly its end, given its cultural vibrancy and creative originality. It was then that the directions of modern Romanian music were mapped, and a qualitative, selective phase in the process of harmonization with Europe began. In March 1898, the Bucharest premiere of George Enescu’s first symphonic work Romanian Poem took place. The composer was just 16 years old and the work was his first great success. The other temporal boundary, the year 1920, was to signify ‘the end of Romanian romanticism’,Footnote 33 according to traditional Romanian musicology. Although the concept of ‘Romanian romanticism’ is debatable (I shall not explore the notion here), it is true that there was a shift in Romanian composition after 1920. Whatever we might call the previous period, the post-1920 epoch may certainly be named modern. Romanian composers assimilated the styles, languages and musical attitudes of interwar Europe with remarkable speed. A modern spirit also characterized their attitude towards folk music, which increasingly distanced itself from the idyllic. Romanian composition thus became a confrontation between structural data drawn from rural and urban folk music, from the monophonic liturgical repertoire, and from European styles (impressionism, neo-classicism, expressionism).

Around 1900, reform of the main institutions of cultural and musical education began, with the country’s capital, Bucharest, setting the tone. Whoever looks more deeply at the city’s nineteenth-century history will note the privileges of the newly formed Romanian state.

Every week in this music-loving and bohemian city there was a concert and a few theatrical performances. From Franz Liszt, who came to Bucharest in 1847, to violinist Wieniawski, who was invited in 1881 and offered a ‘very attractive programme (Beethoven, Haydn, Chopin, Haendel, Bach)’, from Italian singer Adelina Patti to the actress that had stunned Paris, Sarah Bernhardt, Bucharest had the opportunity of welcoming the century’s great artists.Footnote 34

Towards the end of the century, two attitudes came to define Romanian culture and the arts, and these were to be perpetuated, in different guises, in the twentieth century. On the one hand, Europe infiltrated Romania via travel and marriages to other Europeans among the aristocracy and intellectual classes. It was present in the lingua franca, French (sometimes German) used by intellectuals speaking among themselves in conversation, and in letters and journals. A cultivated Romanian had to study in France, Austria, Germany, or, more rarely, England. On the other hand, the century of romanticism and patriotic, revolutionary drives placed an emphasis on ‘Romanianism’. Contemporary writers even mock the habit of adding the adjective Romanian to any title: ‘The Romanian Monitor, The Romanian Street, The Romanian Athenaeum, The Romanian Newspaper, The Romanian Café’.Footnote 35 As for the capital, names such as ‘Little Paris’ or, after the First World War, ‘Little New York’ highlighted a striving on the part of Bucharest, ‘a semi-Oriental and semi-Western city’,Footnote 36 to keep up to date with every cultural trend and fashion.

In Romanian composition there were fierce debates about what and how much should be appropriated from outside, but also about including music of the local oral traditions in ‘cultured’ music as the sign of a distinct voice. It was Dumitru Georgescu Kiriac, a student of Vincent d’Indy at the Schola Cantorum in Paris (like most of his Romanian colleagues), who mapped out one of the two conflicting directions at the beginning of the twentieth century: the affirmation of a national cultural autonomy through the use of folk and Byzantine sources. The other direction argued that Romanian music should be rooted in universal music, and French music in particular. This second aesthetic direction was advocated by an Italian composer based in Romania, Alfonso Castaldi, the first professor of composition at the department established at the Conservatory in 1905. Castaldi had the merit of developing a solid European symphonic tradition (be it post-Wagnerian or French-impressionist) in Bucharest, surpassing the rudimentary attempts in this genre thitherto.

One of the most famous buildings in central Bucharest, the Romanian Athenaeum, was designed by the French architect Albert Galleron.Footnote 37 Constructed in just three years (1885–88) the Athenaeum is still home to the Philharmonic Orchestra, established in 1868 under the conductorship of Eduard Wachmann (son of Ioan Andrei Wachmann). Wachmann was a core member of the Wagnerverein (an association that was active in Bucharest until 1898), and an exemplary exponent of the epoch: of Austrian descent, he became a Romanian citizen in 1876. Like Carol I, he deserves credit for educating the public taste and elevating concert life in Bucharest to European standards, although his efforts were probably not sufficiently appreciated. The accusation that he was a Germanophile, and the criticism that he did not schedule enough Romanian music (often cited by newspapers and, of course, Romanian composers), were justified only to a small extent: Romanian music in the second half of the nineteenth century was still at the level of enthusiastic amateurism. On the other hand, it was Wachmann who conducted the premiere of the young Enescu’s Romanian Poem in 1898, immediately recognizing his unique talent. The piece symbolically marked the beginning of a truly professional and European phase in Romanian composition.

While the Philharmonic remained the only major orchestra in Bucharest, other orchestral ensembles occasionally emerged without really rivalling it. Chamber ensembles were also short-lived, with a few exceptions. In 1898, Dimitrie Dinicu founded a string quartet, which in 1903 was named after the patron of the Romanian arts, Carmen Sylva;Footnote 38 the ensemble was active until 1912. Chamber music evenings were programmed at the Athenaeum, many organized by George Enescu, who performed as a violinist in duets, trios, quartets and quintets or as a pianist accompanying singers and violinists. In fact, Enescu dominated the music scene, not only in concerts and composition, but also thanks to his generous involvement in various projects. For instance, in 1912 he founded the national award for composition that is named after him and has been encouraging young composers ever since. In 1915, thanks again to Enescu’s efforts and the tour he organized to raise funds, the Athenaeum received a concert organ.

The most famous choir of the time, and probably one of the most celebrated professional choral ensembles in the history of Romanian music, was called Carmen, again in honour of Carmen Sylva. These are just two examples of Queen Elisabeth’s tireless and generous activity in support of Romanian artists. The queen knew how to gather around her poets, writers, painters and musicians. In 1900, with his students from the Conservatory and the Theological Institute, Kiriac founded a 40-member choir that performed colinde Footnote 39 and folk songs Kiriac adapted. Originally all male, the choir became mixed after 1902. Later known as the Carmen Society, the choir took part in vocal-symphonic concerts and operas, but particularly excelled at a cappella performances from the universal repertoire, as well as adaptations of folk and Orthodox music and contemporary Romanian compositions.

Bucharest boasted choirs in concert halls, churches, and popular gatherings, as well as brass bands in parks and public gardens and Western-style concerts at the Athenaeum and other concert halls, all while continuing to be a city of opera enthusiasts. In Bucharest around 1900, there were various operatic institutions and foreign companies in the city on tour, and Romanian opera singers such as Hariclea Darclée garnered international acclaim. The first Romanian opera, Petru Rareş by Eduard Caudella, premiered in 1900. Piero Mascagni achieved huge success in 1902, when he conducted the Cavalleria rusticana in Bucharest.

The history of the Romanian Opera as an institution would require an account of its own. There were difficulties stemming from the lack of a distinct opera house – the institution had been founded in 1885 as a section of the National Theatre – and state subsidies were patchy. Some journalists suggested that the state showed favouritism towards visiting foreign opera companies. Initially, the National Theatre was home to two companies that employed more or less the same singers: the Dramatic Society Troupe (specializing in songs, comedies, vaudevilles, operettas, ferias, and operas) and the Romanian Opera (with a specific repertoire, featuring mainly Italian operas, but also some Wagner, since the omnipresent Wachmann organized their programme). Having been repeatedly established and disestablished, the Romanian Opera became a stable institution after the First World War, but it was not to have its own opera house until 1953.

As one music critic wrote, ‘the audience’s soft spot was for the Italian Opera’,Footnote 40 an institution that functioned intermittently in Bucharest between 1898 and 1913. The premiere of Puccini’s La bohème was an immense success, as was Hariclea Darclée’s performance in Tosca in 1902 (two years after the world premiere). The relationship between the Italian and Romanian Opera was rather ambiguous, because although they seemed to be rivals during their seasons, they generally made use of the same soloists. For example, when in the 1901–-02 season the Romanian Opera was unable to give any performances, its singers temporarily moved to the Italian Opera.

A more diverse repertoire than the Italian was constantly demanded by Romanian musicians and partially achieved thanks to visits to Bucharest by touring opera companies from Prague, Paris, Athens, Darmstadt and Dessau (between 1903 and 1917). In this way Bucharest audiences were able to hear Smetana’s The Bartered Bride and even Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, as well as other welcome additions to the local opera repertoire by French, Russian, Czech and German composers.

But it was not only touring opera companies that kept Bucharest abreast of new music from Europe. After 1900, the Wiener Tonkünstler Orchester, conducted by Oskar Nedbal, and the Münchner Tonkünstler, conducted by Jose Lasalle, were other memorable examples, as were the performances by Felix Weingartner, Leopold Godowsky, Jacques Thibaud, Eugene Ysaÿe, Emils Sauer, Fritz Kreisler, and Pablo Casals.

Other aspects of Bucharest musical life around 1900 include the activities of the various associations and circles. There were Austrian librarians, editors and agents, as well as societies of Germans resident in Bucharest: in 1907 Eintracht celebrated 50 years of activity; in January 1909, the Schubertbund was established; other associations included the Bukarester Deutsche Liedertafel and the Vorwärts choral society.

Undoubtedly, there were signs of European modernity in Bucharest. More seldom, Bucharest could also be found represented elsewhere in Europe. For example, at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris, on the theme of ‘The World of Tomorrow’, Romania was represented by 25 painters and 74 paintings, architectural elements, traditional art, industry, cuisine, and crafts, but in accounts of the exhibition there is no mention of music.Footnote 41 It seems that, for the time being, Romanian music only crossed the national borders in a few isolated cases: opera singers such as Haricleea Darclée and violinist George Enescu.

Looking towards modernity

I have chosen two case studies to examine the specific impact Western music had upon Romanian musicians in the mid-nineteenth century (through Liszt’s tour), and at the development of a European-style musical life (in the Romanian capital around the year 1900). Nevertheless, the voice of Romanian composition did not truly become part of the European landscape until the twentieth century. Thitherto, a multitude of Western and Eastern impulses followed upon one another, superimposed each other, and blended with a fascination for oral, folk and Byzantine traditions, which became appropriate tools with which to construct a national canon. Musicians’ energies were absorbed by such experimentation with multiple possibilities, as well as by the endeavour to create institutions based on the Western model (schools, philharmonics, theatres). Rigour and professionalism in composition were not yet priorities. For this reason, the majority of Romanian scores from the nineteenth century are today of more interest to historians than audiences.

At the beginning of this article, I referred to the boundaries of the Romanian nineteenth century as defined by native historians. I examined in detail the chronological boundary of the year 1821, which marked the end of Phanariot and Ottoman influence. The other boundary, the year 1914, was (symbolically) established by the death of King Carol I and the start of the First World War. Romanian musicology emphasizes the significance of the year 1920 when it comes to a new, modern attitude on the part of composers within the ‘Greater Romania’, which resulted from the unification of the Romanian Principalities and Transylvania in 1918. If we set aside such distinctions, it is obvious that it was in the first two decades of the twentieth century that the two main movements in modern Romanian composition began to take shape.

On the one hand, Dimitrie Georgescu Kiriac attempted to define the national voice of a music that was shaped in the Western mould, but of content drawn from Romanian oral traditions. The author of a Psaltic Liturgy (1902), emblematic of the adaptation of Byzantine chant for Western listeners, Kiriac also collected folk tunesFootnote 42 and promoted modal harmony, with bourdon drones, and folk melodies and rhythms. On the other hand, Alfonso Castaldi practised romantic symphonism with his pupils at the Conservatory, as well as inculcating a neo-classical spirit that was to become predominant in interwar Romanian composition. His symphonic poem Marsyas (1907) is probably the best illustration of the way in which this composer of Italian origin was able to create work in a solid Austro-German style, while allowing himself to be seduced by impressionist sonorities.

These two compositional attitudes, in varying blends and accents, masked by either the cloak of traditionalism or the avant-garde, were to mark the entire twentieth century. Nationalism made a forceful comeback in the post-war communist period and was reflected in both composition and writing about music. The nineteenth century (as well as Romanian history as a whole) was viewed in a retrospectively nationalist, simplistic and often distorting way. The merits of the ‘forerunners’ were exaggerated, and homage was paid to those who wrote the first Romanian symphony, the first Romanian opera, and so on, and to those who composed patriotic hymns and, of course, works ‘inspired by folk tradition’. More than a century later, distorted romantic ideas were turned into propaganda, giving rise to countless textbooks, treatises and monographs. For this reason Romanian musicology is still seeking a new perspective, in the attempt to reach a balanced assessment of composers who were more amateur than professional, but who managed to achieve the critical mass necessary for a genuinely pre-eminent figure, George Enescu, to emerge.