Unfortunately, the American population is very diverse.

—Alex AzarFootnote 1We still make less, live under stresses and don’t live as long. We’re still looked upon as the other based upon skin color, as some kind of irreparable sin in the society. People try to adjust to it but, when a pandemic sets in, the data comes out.

—Rev. Jesse JacksonFootnote 2Our colonial legacy is visible every day in our [Dutch] streets. There's an inherent racism and acceptance of inequality.

—Anthropologist Mirjam de BruijnFootnote 3“The Virus Does Not Discriminate”

When COVID-19, the coronavirus, hit the United States and Europe in early 2020, many judged it “the great leveler” as initially individuals from both poor and rich backgrounds died from the virus. The senior UK Minister, Michael Gove, for example, glibly declared in a press conference on March 27, 2020 that “the fact that both the prime minister and the health secretary have contracted the virus is a reminder that the virus does not discriminate.”Footnote 4 But as the global pandemic spread and detailed data about who was dying emerged, the reality proves excruciatingly the obverse to Gove’s imperturbable gloss: infection and death rates differ greatly across age groups, across occupational groups, between urban and rural areas, and above all between members of the white majority population and minority communities in Global North democracies.Footnote 5 Gove’s remarks concerned Britain but the same patterns of disproportional impact are identified elsewhere, for example by the Chicago Urban League (Reference League2020) which found that African Americans make up 30% and 6% of the populations of Chicago and Wisconsin respectively but 60% and 39% of COVID-19 deaths in each place.

Focusing on racial and ethnic disparities is important because COVID-19 has affirmed fault lines between whites and people from minority communities not only in the United States, which will not come as a surprise to most readers, but also in Europe, which is often perceived as more egalitarian (see, for example, Pontusson Reference Pontusson2005; Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury2012). Despite the institutional variation in health care systems, social and labor market policies, and immigration experiences, in each of these Global North democracies minority communities—citizens and migrants—have been hit harder in Wave One of COVID-19 and by the subsequent economic crisis than has the white majority population.Footnote 6 The racialized patterns of COVID-19 are thus present across the Global North.

In Britain, for example, a country with universal healthcare, BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) communities have been disproportionately ravaged by COVID-19 (see Apea et al. Reference Apea, Wan, Dhairyawan, Puthucheary, Pearse, Orkin and Prowle2021; Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Walker, Bhaskaran, Bacon, Bates, Morton, Curtis, Mehrkar, Evans, Inglesby, Cockburn, McDonald, MacKenna, Tomlinson, Douglas, Rentsch, Mathur, Angel, Grieve, Harrison, Forbes, Schultze, Croker, Parry, Hester, Harper, Perera, Stephen, Smeeth and Goldacre2020; Khunti et al. Reference Khunti, Singh, Pareek and Hanif2020; Lawrence Reference Lawrence2020; Halliday et al. Reference Halliday, Kirk, Pidd and Leach2020).Footnote 7 A rigorous Office of National Statistics (ONS) study concludes that during Wave One Black Britons are four times more likely than whites to die from COVID-19 (ONS 2020; Halliday et al. Reference Halliday, Kirk, Pidd and Leach2020). This finding came after adjusting, using the 2011 Census, for age, rural-urban residence, region, level of area deprivation, household composition, household income, education, ownership versus rental property, and any recorded disability or health condition. This shows that influential explanations emphasizing underlying health conditions or socio-economic inequalities (visible in disparities of opportunities and outcomes in education, jobs, housing, income and so forth) do not provide complete accounts.

We argue that institutional racism and discrimination are key to understanding the patterns of health and economic disparities between minority communities and the white majority population in Global North democracies. Put briefly, these factors structure and maintain health and income inequalities between racial and ethnic groups. We document how the dissemination of COVID-19 falls disproportionally on minority communities across the Global North and link these unequal outcomes to our theoretical framework. Because the global pandemic and its economic consequences are unfolding, we can only present first-cut empirical evidence from four countries, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and (with less data) Sweden, that are broadly representative of Global North democracies. This evidence already shows that consistent with how the burden of racial and ethnic legacies endures in these countries, people from minority communities have worse health and economic outcomes under normal circumstances and that the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated these inequalities.

The Comparative Politics of a Racialized Pandemic

Centering the role of institutional racism and discrimination as determinants of COVID-19’s partiality deepens understanding of the pandemic and its political significance. Some commentators argue that people from minority communities are more vulnerable to COVID-19 because they are more likely to suffer from pre-existing health conditions, such as diabetes, severe obesity, or heart disease. This position was promoted by the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, who commented “Unfortunately the American population is very diverse … It is a population with significant unhealthy comorbidities that do make many individuals in our communities, in particular African American, minority communities particularly at risk here.”Footnote 8 So in effect the victims of COVID-19 are blamed for their vulnerable circumstances while the underlying structural causes are overlooked (Cooper Reference Cooper2020), such as how some African Americans are given inferior medical attention because of racism (Eligon Reference Eligon2020). Relatedly, the role of occupations is often highlighted: workers from minority communities are more exposed to the virus because they are more likely to work in “frontline” occupations, such as health care, transport, and grocery stores, which require frequent and close contact to others. For instance, by May 10, 2020, of over twenty doctors who had contracted and died from the coronavirus in the UK, only one was white (Sample Reference Sample2020).

Both health inequalities and exposure to frontline jobs matter, but neither can fully explain why people from minority communities have a higher risk to contract COVID-19 or to die from the virus than their counterparts in the white majority population, parts of whom exhibit similar health traits and hold similar jobs. Beyond any epidemiological account, understanding these racial and ethnic disparities means recognizing the underlying structural racism and discrimination that push people from minority communities into having poorer health, working in high-risk and low-paid occupations, and living in deprived neighborhoods.

The Enduring Burden of Persistent Racism and Discrimination

We argue that institutional racism and discrimination are significant vestiges from these Global North countries’ colonial and racial hierarchy pasts, determining how minoritiy communities are integrated (or not) into domestic politics, with consequences for the way COVID-19 has differentially affected citizens and migrants from minority communities (Bleich Reference Bleich2003; Hanchard Reference Hanchard2018; Janoski Reference Janoski2010). Because of persistent racism and discrimination, people from minority communities are more likely to occupy a vulnerable position in the labor market, to take up more non-standard contracts; and to face structural inequalities in housing and health (King and Rueda Reference King and Rueda2008; Lancee Reference Lancee2016; Thelen Reference Thelen2019). These patterns increase their vulnerability to the pandemic.

The health and economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis falls disproportionately on minority communities because they are disproportionately pushed into insecure and low-paid employment (which correlates with experiencing more cramped and segregated housingFootnote 9 and partial access to the social rights of citizenship). People from minority communities disproportionately occupy these vulnerable positions in the labor market and society at large in part, we argue as a consequence of enduring institutional racism and discrimination (Dawson and Francis Reference Dawson and Francis2015; Hall Reference Hall1999; Michener Reference Michener2018, Reference Michener2020; Weir and Schirmer Reference Weir and Schirmer2018; W. Williams Reference Williams2020). The root causes of these inequalities include the unequal distribution of economic resources (and therefore power) but also embedded racial discrimination. It is no coincidence that a wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests exploded during the pandemic across the Global North (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel Reference Buchanan, Bui and Patel2020; K.-Y. Taylor Reference Taylor2020a), sparked initially by recurrent police violence but then mobilized into a broader set of concerns and demands to address racial inequalities including the persistence of unequal health outcomes (Strings Reference Strings2020; Byrd Reference Byrd2020). Political scientist Michael Hanchard links the persistence of racial inequality in Global North societies to migration and inherited racial-ethnic legacies rooting the sort of institutional racism and discrimination that we emphasize here. In The Spectre of Race, Hanchard describes how “policies and practices first utilized in colonial societies to manage subordinated colonial populations found their way into domestic policy” (Reference Hanchard2018, 17). Hanchard calls these “robust racial and ethno-national regimes” built by states to differentiate “among populations within society,” particularly by distinguishing between “populations who were part of the initial citizen-state pact and those populations who were not,” thereby creating and maintaining political inequality (Hanchard Reference Hanchard2018, 22) The United States’ “initial citizen-state pact” plainly excluded then enslaved African Americans and their descendants, an exclusion with continuing ramifications (King and Smith Reference King and Smith2005), including for health care provision (LaVeist and Benjamin Reference LaViest and Benjamin2021). Hanchard explains how these processes developed historically to create present-day patterns of resilient racism and discrimination in the United States, Britain, and France. In the case of Britain, the combination of decolonization (resisted violently by the UK state) and the increased presence of subjects from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean generated both “national anxiety” about the threat to the British “way of life” and immigration reforms targeted on non-white migrants (Reference Hanchard2018, 135). Hanchard remarks on the “accumulation of racist incidents disproportionately affecting black and brown communities” (Reference Hanchard2018, 142; Hall Reference Hall1999; Murji Reference Murji2017). In France, the persistent “valorization of certain ethnic groups,” judged as “other and unassimilable” pervades the contemporary landscape and reworking of colonial hierarchies in domestic politics (Hanchard Reference Hanchard2018, 146–147).

Few will dispute the prevalence and consequences of unequal patterns of opportunity, income, housing, and access to health care experienced by communities of color in Global North democracies. Accumulated research finds that in any explanation of these patterns, once adjustments are made for factors such as age, gender, and education, there remains a distinct racial or ethnic source of inequality, variously described as explicit discrimination, implicit bias, systemic or institutional racism, or some combination (Heath and Cheung Reference Heath and Cheung2007; Heath and Di Stasio Reference Heath and Stasio2019; Kogan Reference Kogan2007; Sharkey Reference Sharkey2008; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2014; Taylor Reference Taylor2019; Sampson, and Winter Reference Sampson and Winter2016). Racial and ethnic effects powerfully interact with nation-specific factors to exacerbate disparate impact: for example, access to health care in the United States is vastly more restricted for many people than it is in the nominally universal National Health Service in Britain (though new British laws in the 2010s impose restrictions on legal and undocumented migrants’ access, and legal migrant workers’ ineligibility for coronavirus vaccination is uncertain; Mohdin, Davies, and Taylor Reference Mohdin, Davies and Taylor2021), or in the Netherlands and Sweden where migrants have comprehensive access.

However, institutional variations merely contextualize the experience and constraints facing communities of color in these different countries. They do not obviate the presence of such factors, which we divide into two broad types: the systemic organization of discrimination and health system inequities.

Systemic Discrimination

Scholars commonly describe the unexplained part of disparate outcomes as the “ethnic gap.” We prefer the notion of the systemic organization of discrimination often dubbed “structural racism” or “institutional racism” (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017; Merolla and Jackson Reference Merolla and Jackson2019; Michener Reference Michener2018)). An influential formulation of “institutional racism” is developed in Black Power by Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) and Charles V. Hamilton (Reference Ture and Hamilton1992, 4), as “acts by the total white community against the black community.” They note that these are not just acts or expressions of prejudice by individuals but actions that depend on “less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing the acts.” But subtlety does not camouflage the “destruction” achieved through the “operation of established and respected forces in society” (see also K.-Y. Taylor Reference Taylor2020b; Tesler Reference Tesler2020). In the UK the term “institutional racism” entered political discourse when it was employed by Sir William Macpherson of Cluny in his inquiry into the police’s biased and obfuscatory pursuit of the perpetrators in the racist killing of a young teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993 in London (Macpherson Report Reference Report1999). Macpherson stresses the role of racism independent of overt racist individuals acting (though individuals do act in racist ways), and how culture structures behavior. An organization’s occupational structure reproduces racist behavioral norms expressed in everyday practices. The upshot is reproduction of racism at every level of organizational actions.

Institutional racism and discrimination are a constant of Global North democracies but intensify for people from minority communities, including many migrants, during crises, as research about unemployment rates and reduced household income shows about the 2008–2009 crisis (Pitts Reference Pitts2011; OECD 2012), and now spectacularly so in the pandemic. These groups’ position is revealed as multiply vulnerable in a pandemic: low-wage and low-skill jobs with close personal contact with others at work including in front-line health posts (Fernandez-Reino, Sumpton, and Vargas-Silva Reference Fernandez-Reino, Sumpton and Vargas-Silva2020), afforced with insufficient personal protective equipment, variable health care support, cramped or dense housing that increased exposure of the healthy to the contaminated, and precarious finances with low household savings and feelings of economic insecurity. The key point is that while in periods of economic growth the effects of systemic discrimination may be less visible, they remain significant determinants of opportunity and outcome for people from minority communities, and the ballast of these cairns of racism grows during crises.

The Unequal Health System

The impact of COVID-19 on minority communities and migrants echoes how the social determinants of health are racialized, notably in the United States (LaViest Reference LaViest2005; LaViest and Benjamin Reference LaViest and Benjamin2021; LaViest and Issac Reference LaViest and Isaac2012; Sun Reference Sun2020). Lisa Cooper, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University remarked that for public health researchers, “the pandemic was simply shining a magnifying glass on structural racism as a public health issue” (Cooper Reference Cooper2020; see Colen et al. Reference Colen, Ramey, Cooksey and Williams2018; Jackman and Shauman Reference Jackman and Shauman2019; Williams and Cooper Reference Williams and Cooper2019). In an important contribution, political scientist Julia Lynch (Reference Lynch2020) finds that health outcomes in Global North countries are intrinsically linked to structural patterns of economic and social inequality, patterns that reflect legacies of racial and ethnic hierarchies. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Reference Taylor2020a) writes of the United States, the “state is failing black people,” a failure amplified by the COVID-19 culling. Native Americans have also suffered disproportionally from the COVID-19 virus: hampered by data limitations, a New York Times study nonetheless estimated that in July 2020 the infection rate for Native Americans was 1.7 times higher than the rate for white people (Conger, Gebelofff, and Oppel Reference Conger, Gebeloff and Oppel2020). Minority communities in other countries have been vulnerable too including in the Netherlands and Britain (Lawrence Review Reference Lawrence2020, Marmot et al. Reference Marmot, Allen, Goldblatt, Herd and Morrison2020).Footnote 10

These health inequalities, which may be defined as “preventable inequalities in health status between groups that are characterized by different positions in the social, economic, and political structure” (Lynch Reference Lynch2020, 27), are not simply an outcome of impersonal economic forces or individual stupefaction. They are often a consequence of persistent socio-economic inequalities entrenched in national ethnic hierarchies. Lynch remarks that “in west European countries access to medical care is guaranteed to all but the most marginalized groups” (Reference Lynch2020, 27-28). These “marginalized groups” are now quite a broad category, as state capacity proves wanting, stretching across both low-skilled migrants and many members of minority communities. For them, access is not guaranteed. The undocumented in America, cut out of the formal system, rely on voluntary health aid, while their counterparts in Europe too face significant barriers to access healthcare (Grunau Reference Grunau2020). Legal migrants in these societies, subject to no-recourse-to-public-benefits clauses, may also find themselves without coverage (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2020). In the UK, for example, one estimate puts the number of non-EU residents affected at 1.1 million people (see Wright Reference Wright2020), and another study calculates that 100,000 people will fall into unemployment because they are barred from applying for public benefits (Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity 2021). While some countries temporarily lifted these formal restrictions during the pandemic, they have a deterrent effect on those fearing deportation or negative consequences for their migration status/visa renewal (Boucher et al. Reference Boucher, Hooijer, King, Napier and Stears2020). These obstacles layer upon entrenched racial and ethnic inequalities of the sort targeted by BLM protests (Blow Reference Blow2020; Byrd Reference Byrd2020; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2020; Hirsch Reference Hirsch2020; Medina Reference Medina2020).

Even in Sweden, where the public health regime opted in Wave One for far less locking-down and fewer work restrictions than its European neighbors, migrant communities have been hit hard (Gustavsson Reference Gustavsson2020). A survey by the national Public Health Agency found that relative to their percentage of the national population, migrants from Somalia, Iraq, and Syria were overrepresented among the COVID-19 cases in Swedish hospitals. Immigrant-dense suburbs have endured the highest rates of COVID-19 infection and death in Sweden, in some cases showing infection rates three times the national average (Rothschild Reference Rothschild2020).

Minority communities and marginal groups endure what Lynch terms the “social determinants of health,” including “the living, working, educational, family, and community environments that shape individuals’ exposure to risks that ultimately contribute to health status.” Such “upstream” causes stem in part from fundamental socio-economic inequality, including systemic discrimination, and constitute in Lynch’s words “the financial resources over which individuals have command [and which] have such a large impact on the environmental conditions that they experience” (Reference Bambra, Riordan, Ford and Matthews2020, 29; and see Bambra et al. Reference Bambra, Riordan, Ford and Matthews2020). The organization and distribution of these financial resources are obviously the nettle of political struggles and party politics.

Discrimination and Inequalities in Comparative Perspective

We focus on racial and ethnic inequalities in the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Sweden.Footnote 11 All four cases have reported comparatively high rates of infection and death from COVID-19, and disproportionate impacts on minority communities. They are representative of Global North countries with embedded racial and ethnic legacies derived from colonial and enslavement pasts and discriminatory practices toward migrants and communities of color (Hanchard Reference Hanchard2018; Katznelson Reference Katznelson1976; Lake and Reynolds Reference Lake and Reynolds2008; Michener Reference Michener2018; Pitts Reference Pitts2019).Footnote 12 These states entered the pandemic with entrenched racism and discrimination.

The four cases vary on their governments’ response to the COVID-19 crisis, health care systems, welfare regimes, and (undocumented) migrant populations, with distinct national health and economic outcomes (see table 1). They also vary in history and levels of institutional racism and discrimination, but racial and ethnic inequalities in health and in economic outcomes are significant in all four cases. The comparison shows that the impact of racial and ethnic discrimination on pandemic policy outcomes is not unique to the US.

Table 1 Selection of relevant case characteristics

Notes *Each country evinces significant internal differences in their ethnic hierarchies.

a Hale et al.’s (Reference Hale, Angrist, Cameron-Blake, Hallas, Kira, Majumdar, Petherick, Phillips, Tatlow and Webster2020) Covid Response Stringency Index (0-100, 100=strictest) is based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans.

b For the United States, data are from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219; for the UK: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest; for the Netherlands: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/37296ned/table?ts=1593962858781; for Sweden: https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/pong/tables-and-graphs/yearly-statistics--the-whole-country/foreign-born-by-country-of-birth-sex-and-year-of-immigration-31-december-2019/

c OECD 2020a

Data and Measurement

Assessing the disparate health and economic impact of COVID-19 in a comparative perspective presents major empirical challenges. Since we are still in the midst of the global health and economic crisis, the range of available and comparable data is limited and subject to revision. We therefore rely on a select number of indicators, such as unemployment rates, which are available on a quarterly or monthly basis to examine the short-term consequences of the crisis. We use aggregate outcomes to illustrate broad patterns. Previous research suggests that such patterns hold in more sophisticated statistical analyses that control for individual-level factors, though the gap between people from minority communities and the white majority population may become smaller.

Our interest in racial-ethnic inequalities faces another challenge as only a handful of countries collect data on an individual’s race/ethnicity. Moreover, these categories are not directly comparable across countries, since each expresses country-specific traditions of boundary-drawing and specification of inclusion and exclusion. Yet they allow us broadly to capture minority communities in each of our cases.

For the United States, the main racial-ethnic groups are Whites, Blacks or African Americans, Asians, Hispanics or Latinos, and American Indians.Footnote 13 The UK mostly distinguishes between the following ethnicities: White, Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups, Asian, Black, and Other (including Arab). Since there is substantial variation in the socio-economic outcomes of different Asian groups, this subgroup is sometimes disaggregated. In both the United States and the UK, white migrants and their descendants, who may face different circumstances due to their recent immigration experience, cannot be distinguished from the white majority population. This differs for the Netherlands where three main groups are generally distinguished: those with a native background (for individuals with two native-born parents), a Western migrant background (for those with at least one parent born in another Western country), and a non-Western migrant background (for those with at least one parent born in a non-Western country).Footnote 14 Since “non-Western” is synonymous with “non-white”, these categories have an unsubtle racial component. Due to data limitations, we rely on a person’s country of birth for the Swedish case. This definition is both too narrow, as it does not capture the descendants of migrants,Footnote 15 and too broad because it includes white migrants who often have better outcomes than non-white migrants from the Global South (see Arai and Vilhelmsson Reference Arai and Vilhemsson2004). However, it still allows us to explore patterns of racial and ethnic inequalities in a broad fashion.

Discrimination through Pandemic Diffusion

Data on COVID-19 health outcomes are notoriously difficult to compare cross-nationally: countries have different testing policies; data on COVID-19-related deaths may be collected only for hospital deaths; and countries may include not only confirmed cases but also suspected cases. For our purposes, the greatest challenge is that few countries record ethnicity on death certificates.Footnote 16 Ideally, we would measure the impact of the coronavirus through data on excess deaths for different racial-ethnic groups, defined as the difference between the observed number of deaths and the expected number of deaths in a given period. These data are available for the Netherlands administratively only, as the country does not record the ethnicity of individuals who undergo testing or record their ethnicity on death certificates. For the other three countries, however, we have access to data on deceased individuals who tested positive for the virus.

Despite these nontrivial limits of data compilations, the racial and ethnic disproportionality of the pandemic’s distribution has garnered headlines. This is particularly striking given that communities of color generally have a younger age profile in all these countries, the age cohort less affected by COVID-19 in the first wave. In the United States, the UK, and to a lesser extent in the Netherlands and Sweden, there has been intense focus on the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus on people from minority communities. Table 2 illustrates the latter outcome. It reports the odds of dying from COVID-19 for different racial-ethnic groups compared to the white majority population in the first months of the pandemic.

Table 2 Racial-ethnic groups’ odds of dying from COVID-19 compared to the white majority population.

Notes *Classifications are country specific.

a Data from the APM Research Lab covering the period up to June 10, 2020: https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race

b Data from the ONS (2020) covering England and Wales in the period from March 2, 2020 until 10 April 2020). Note that these odds have been adjusted for age.

c Data from Statistics Netherlands covering the period from March 9, 2020 until April 19, 2020. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2020/20/oversterfte-tijdens-de-eerste-zes-weken-van-de-corona-epidemie

d Data from the Swedish Public Health Agency from March 13, 2020 until May 7, 2020. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/d6538f6c359e448ba39993a41e1116e7/covid-19-demografisk-beskrivning-bekraftade-covid-19-fall.pdf

The original data only list deaths by country of birth for those origin countries with 11 deaths or more.

Although these odds are not easily comparable across countries due to the data limitations identified earlier, two broad patterns emerge from table 2. First, we see that people from minority communities are more likely to die from COVID-19 than the white majority population in all four countries. Consistent with the outcomes described in Lynch’s (Reference Lynch2020) study of health inequalities, this suggests that racial-ethnic disparities in health outcomes exist across different institutional contexts: from the United States, where many racial-ethnic groups face severe barriers to accessing health care, to the UK and Sweden, where health care is (in principle) universal. This chilling pattern fits with previous research on racial-ethnic inequalities in self-reported health, life expectancy, and infant mortality (Bhopal Reference Bhopal1998; Blom Huijts, and Kraakamp Reference Blom, Huijts and Kraaykamp2016; Gray et al. Reference Gray, Headley, Oakley, Kurinczuk, Brocklehurst and Hollowell J2009; Olshansky et al. Reference Olshansky, Antonucci, Berkman, Binstock, Boersch-Supan, Cacioppo, Carnes, Carstensen, Fried, Goldman, Jackson, Kohli, Rother, Zheng and Rowe2012; Williams and Collins Reference Williams and Collins1995; Wohland et al. Reference Wohland, Rees, Nazroo and Jagger2015). Secondly, we find that the odds of dying from COVID-19 vary across different racial-ethnic groups and that this variation resembles the ethnic hierarchies found in other spheres, such as the labor market (see Heath and Di Stasio Reference Heath and Stasio2019). Across the United States and the UK, black ethnic minorities have the highest odds of dying while ethnic minorities from Asia and South America have outcomes closer to those of the white majority population, though they generally still face a greater risk than the latter. This also comes out in the data for the Netherlands, where minorities racialized as possessing non-white backgrounds (i.e., those with a non-western migrant background) have higher odds of dying than minorities racialized as possessing white backgrounds (i.e., those with a western migrant background). In Sweden, we find that migrants from the Middle East are more exposed to acquiring COVID-19 than the white majority population, despite their younger age profile. The higher odds of dying for Finnish-speaking Swedes stands out, though a likely explanation for this is that they have an older age profile than the white majority population, many journeying to Sweden as labor migrants in the post-World War II period.

Another way to examine racial-ethnic inequalities in health outcomes is by comparing the distribution of ethnic minorities among all COVID-19 deaths to their distribution in the total population as depicted in table 3. These profiles show that black people in the United States make up 23.1% of all COVID-19 deaths while they form 13.4% of the total population. African Americans’ likelihood of dying is thus much higher than we would expect based on their distribution in the total population if the virus infected randomly (Chicago Urban League Reference League2020). The same is true for the UK: the likelihood of black people being among the tally of COVID-19 deaths is twice as high given their percentage of the population (Lawrence Review Reference Lawrence2020). The Netherlands bucks this trend: there ethnic minorities racialized as non-white are underrepresented among COVID-19 deaths compared to their share of the population. This may well be a result of higher health spending per capita: although the United States has the highest such spending per capita ($11,072), the skewed nature of this spending and exceptional costs compared to per capita health outcomes is familiar (Lynch and Perera Reference Lynch and Perera2017); comparatively both Sweden ($5,782) and the Netherlands ($5,765) spend markedly more than the UK ($4,653) per capita on their populations (OECD 2020b), which is likely to help explain the comparative patterns.

Table 3 Main racial-ethnic groups as percentage of Covid-19 deaths and total population (in parentheses).

Notes *Classifications are country specific.

a Data from the CDC, updated to July 1, 2020: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid_weekly/index.htm#Race_Hispanic Data on the population distribution by race/ethnicity are from 2019: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

b Data from the ONS covering England and Wales in the period from March 2, 2020 until 10 April 2020:

c Data from Statistics Netherlands covering the period from March 9, 2020 until April 19, 2020. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2020/20/oversterfte-tijdens-de-eerste-zes-weken-van-de-corona-epidemie Data on the population distribution by migrant background are from 2019: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/37296ned/table?ts=1593962858781

d Data from the Swedish Public Health Agency covering the period from March 13, 2020 until May 7, 2020: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/d6538f6c359e448ba39993a41e1116e7/covid-19-demografisk-beskrivning-bekraftade-covid-19-fall.pdf

Recent findings undercut the claim that the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities is due to a high incidence of comorbidities. For example, (one of) the largest studies of health records—17.4 million NHS UK adults between February 1, 2020 and April 25, 2020—concluded that the higher prevalence of medical conditions can only explain a small portion of the increased risks faced by ethnic minorities (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Walker, Bhaskaran, Bacon, Bates, Morton, Curtis, Mehrkar, Evans, Inglesby, Cockburn, McDonald, MacKenna, Tomlinson, Douglas, Rentsch, Mathur, Angel, Grieve, Harrison, Forbes, Schultze, Croker, Parry, Hester, Harper, Perera, Stephen, Smeeth and Goldacre2020). In the United States, Strings (Reference Strings2020) decries accounts of underlining health conditions, notably obesity, which take these demographics as unproblematic, neglecting the legacy of enslavement.

More important seems to be the inequalities in health care access for individuals from minority communities who fell ill during the COVID-19 crisis. Reports from the United States and the UK suggest that, respectively, formal restrictions and the hostile environment severely limit (undocumented) migrants’ abilities to seek and receive proper health care treatment (Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity 2021; OECD 2020c). Beyond that, research from the US has shown that racism among health care providers can negatively affect whether diseases are accurately diagnosed (Paradies et al. Reference Paradies, Truong and Priest2013). Even in the Netherlands and Sweden, where formal social rights are more entrenched, equal access seems hampered by the lack of communication - information about the virus and government measures were not always offered in the languages of migrant communities.

The Maintenance of Inequalities

Previous research on economic crises reveals that people from minority communities, including migrants and citizens whose parents were migrants, are more likely to lose their jobs during crises, less likely to be eligible for generous income support programs, and less likely to gain employment when the crisis ended (Boucher and Gest Reference Boucher and Gest2018; Dustmann, Glitz, and Vogel Reference Dustmann, Glitz and Vogel2010; Emmenegger and Careja Reference Emmenegger, Careja, Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012). This effect is confirmed by survey data from the beginning of the crisis showing that African Americans and Hispanics in the United States are more likely than whites to report that they or someone in their household have lost their job or had to take a cut in their pay due to the COVID crisis. They are also less likely to have a financial buffer in case of an emergency (Pew Research Center 2020b; Hardy and Logan Reference Hardy and Logan2020).

The short-term patterns in terms of labor market disparities echo these findings. In the UK, workers from BAME backgrounds disproportionately occupy frontline low skill but heavily exposed positions (often called key or essential workers), epitomized for instance in the number of bus drivers and underground staff in London culled by the disease. The director of the non-profit Runnymede Trust, Omar Khan, highlights the disproportionate harm of COVID-19 in Britain on BAME citizens. Khan (Reference Khan2020) worries that, “even more striking than the disproportionality in critical cases is the fact that the first 10 doctors who died of COVID-19, and two-thirds of the first 100 health and social care workers, were from ethnic minorities.” He adds that “although ethnic minorities are more likely to work in these sectors, the mortality figures far exceed their representation in health and social care.” Research into the causes of their higher fatality continues, but discrimination seems likely to play a significant role, a belief that is also expressed by half of BAME healthcare workers reporting in a large survey (ITV 2020).

For citizens confronting COVID-19 the labor market context combined with levels of access to health care translates marginality and systemic discrimination into fragile vulnerability to the pandemic. Consequently, the nature of participation in the labor market are important parts of the explanation for the higher burden of the COVID crisis on workers from minority communities.

Health Care

The combined effects of the systemic organization of discrimination and inadequate health care access are vivid in the United States. COVID-19 has cut through African American and Latino neighborhoodsFootnote 17 facilitated by the structurally disadvantaged position occupied by many people from minority communities in the labor market (Medina Reference Medina2020). Disproportionately concentrated in essential but weakly PPE protected jobs (working in grocery stores, deliveries, or public transport systems), many frontline workers have been infected and sadly died. Mass transport workers in large cities have experienced high infection and death rates (George and Jaffe Reference George and Jaffe2020). Inherited inequalities of access to health care and illnesses, such as diabetes, exacerbated vulnerability in the face of coronavirus. These are longstanding inequalities, which have proved fatal yet again. One study finds that “Black people make up a disproportionate share of the population in 22% of U.S. counties, and those localities account for more than half of coronavirus cases and nearly 60% of deaths” (V. Williams Reference Williams2020).Footnote 18 Statistical analysis also shows that access to health care and employment status are more important predictors of infection or death for African American communities than underlying health conditions (Strings Reference Strings2020). This finding points to how the diffusion and consequences of COVID-19 are layered onto enduring racial and ethnic inequalities in the United States (see also Hardy and Logan Reference Hardy and Logan2020). Many Hispanic workers in the United States occupied essential frontline or densely packed workplaces but feared that raising concerns about exposure to the pandemic would result in job loss, and few knew they had rights to sick leave (Interlandi Reference Interlandi2020).

In Europe, the UK has recorded the sharpest negative infection and morbidity effect for minority communities resulting from exposure to COVID-19. As in other countries, this group is overrepresented in high-risk frontline occupations in health and social care, retail, and transport services. Although the UK’s National Health Service provides universal access, and even undocumented migrants can access the NHS for treatment for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, limited knowledge of these exemptions and low levels of trust in these institutions have created barriers to access (Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity 2021). This is the legacy of the UK’s “hostile environment” immigration framework, pursued forcefully by the Conservative government since the 2010s, which requires the NHS (and other service providers) to check a person’s legal status and makes migrants less likely to seek out medical treatment. Across Europe, many of the clusters of high infection rates have occurred among migrant workers, for example those employed in the meat packing industry or in the agricultural sector. The COVID-19 crisis has once again revealed the precarious position of these workers, who often originate from Eastern European countries, as they are heavily reliant on employment agencies for their income, housing, and even access to health care. In the Netherlands, for example, migrant workers lose their access to health care if they lose their jobs and a survey among 900 migrant workers suggests that in practice many must consult their employment agency before they can see a doctor (NOS 2020).

Labor Market Disparities

We illustrate how the pandemic’s diffusion is racialized by focusing on two labor market economic indicators: unemployment rates and the distribution of occupations amongst communities of color. Quarterly or monthly unemployment rates enable us to assess how the short-term impact of the economic crisis following the COVID-19 health crisis is distributed across different racial-ethnic groups within a country. This distribution also gives a hint of the negative consequences for the future when activist government programs such as furlough schemes and business subsidies end. It is important to keep in mind that these data most likely underestimate the extent of unemployment among people from minority communities because recent and undocumented migrants, often employed in the informal sector, tend to be underrepresented in most surveys.

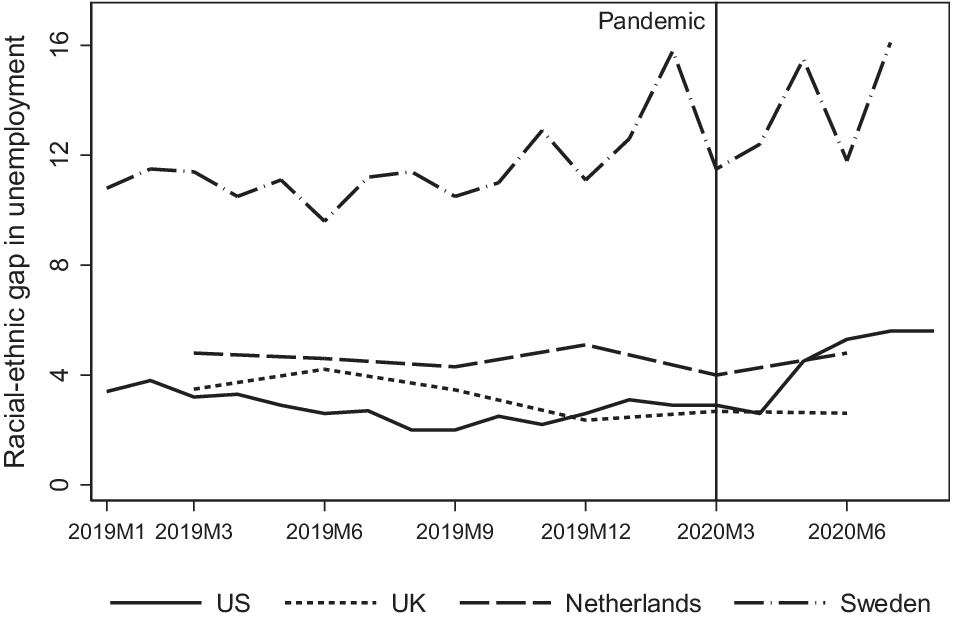

Unemployment. Figure 1 displays the unemployment rates for members of the white majority population and minority communities in the United States, the UK, the Netherlands, and Sweden.Footnote 19 We mark the onset of the global pandemic with a vertical line, corresponding to March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization first declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Despite large differences in these countries’ labor markets, government responses to the pandemic, and the extent to which job retention programs operated to cushion the blow, we find as a general pattern that people of color had substantially higher unemployment rates than the white majority population in all four countries before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. During the crisis, we find two distinct patterns for countries without extensive furlough schemes (United States, Sweden) and those with extensive furlough schemes (UK, Netherlands). Unemployment rates for people from minority communities increased faster during the crisis in the former, signifying that the furlough schemes have managed to dampen this upsurge for now in the latter.

Figure 1 Short-term effects of the Covid-19 crisis on unemployment rates by main racial-ethnic group

Panel A shows that unemployment rises to unprecedented levels for all groups in the United States, but the rise is steepest for Hispanics (Hubler et al. Reference Hubler, Fuller, Singhvi and Love2020). After reaching its peak in May 2020, unemployment rates slowly improve again for whites and Hispanics. For African Americans, however, the return to normality is much slower. They confront unemployment rates stabilizing at a level higher than they have experienced in the past twenty years. The situation is similar in Sweden, the only country in Western Europe without a full lockdown but with one of the highest unemployment rates for people from minority communities before the crisis. Panel D shows that the discomforting inequalities in unemployment rates in Sweden between the native-born and the foreign-born population have increased during the current crisis. Unemployment among the native born started to improve again in July 2020, but for the foreign born in Sweden the situation is the opposite. Their unemployment rates, which were already more than three times higher than those of their counterparts, reaches a new high of 21.2% in July 2020.

In the UK (panel B) and the Netherlands (panel C), the short-term effects on unemployment rates have been more modest, in large part due to generous furlough schemes that have supported millions of workers in both countries (over 20% of the UK workforce). The quarterly data for both countries suggests that rising unemployment has been successfully contained for the white majority population as well as for ethnic minorities, although we do see a larger increase among those with a non-Western migrant background in the Netherlands (from 6.6% in the first quarter of 2020 to 7.9% in the second quarter). We expect that racial-ethnic inequalities in the labor market will also grow in these countries once the scope of their furlough schemes diminishes or these programs end. The UK government’s comprehensive furlough scheme ended on October 31, 2020Footnote 20 (with a modified version retained), and many companies and sectors in which BAME workers are overrepresented have already announced large-scale redundancies. The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR 2020) has estimated that between 10% and 20% of these furloughed workers may become unemployed. The Dutch government has extended its generous scheme until July 2021, reverting from its earlier plans to make the arrangements more sober.

Figure 2 summarizes these broad patterns. It displays the raw difference between the unemployment rates of the white majority population and people from minority communities in all four countries. This racial-ethnic disparity in unemployment rates is substantial in all countries, dizzyingly so in Sweden. The figure also shows that this gap has remained more or less stable in the UK and the Netherlands for now, but that it has increased rapidly in the United States, where the gap has more than doubled, and in Sweden, where the difference now exceeds more than 16 percentage points. These trends vividly confirm the racialized nature of economic outcomes in Global North democracies consistent with enduring institutional racism and discrimination.

Figure 2 Racial-ethnic gaps in unemployment

Note: The gaps reflect the difference between whites and African Americans in the US; whites and ethnic minorities in the UK; native background and non-Western migrant background in the Netherlands; and native-born and foreign-born in Sweden.

Occupations. Next, we turn to the degree to which workers from minority communities are overrepresented in “vulnerable occupations.” Such overrepresentation is crucial to workers’ health because their occupational distribution, which often reflects systemic discrimination, influences their environmental probability of contracting COVID-19, and the economic impact the crisis has on their livelihoods. A focus on occupations can therefore reveal the double threat that Covid-19 poses to minority communities.

We begin by exploring the relationship between the occupational distribution of people from minority communities and occupational characteristics that influence an individual’s probability of contracting COVID-19. The ability to practice social distancing has proven vital in preventing the spread of COVID-19 and in all four countries governments have advised their citizens to maintain some distance, though the enthusiasm, timing, and precision of this advice has varied. We measure the percentage of people from minority communities in each detailed occupation, and the degree of physical proximity required for each occupation, based on data from the Occupational Information Network ( O*NET 2021). Data availability limits this analysis to the United States and UK only.Footnote 21 Since race and ethnicity are not mutually exclusive categories in these U.S. data, we present the relationship for Hispanics only here. The pattern, however, is similar when we use the percentage of African Americans instead.Footnote 22

As implied by how the systemic organization of discrimination functions to structure labor markets, we find in figure 3 a positive relationship between the percentage of people from minority communities in each occupation and the degree of physical proximity required for each occupation in both countries. The figure for the United States shows that Hispanics are more likely to work in those occupations that require physical proximity to others. These include meat packers, personal care assistants, taxi drivers and chauffeurs, and retail workers. Moving over to the UK, we find a similar positive relationship: there too, ethnic minorities are more likely to work in professions that are least suitable to practice social distancing. The occupational distribution of people from minority communities is thus an important factor contributing to the increased risk that these groups may contract COVID-19.

Figure 3 Occupational exposure to Covid-19 and racial-ethnic inequalities

Obviously, a key question concerns why workers from minority communities are more likely to end up in these riskier and often more insecure and lower-paid occupations. An extensive literature from labor economics and sociology has demonstrated that neither individual factors, such as the level of education, gender, age, or language proficiency, nor institutional factors, such as the size of the low-skilled sector and labor market policies can fully explain the occupational distribution of ethnic minorities and migrants (Dustmann and Frattini Reference Dustmann, Frattini, Card and Raphael2013; Heath and Cheung Reference Heath and Cheung2007; Kogan Reference Kogan2007). In the European literature, this unexplained element is euphemistically called “the ethnic gap.” This un-reflective term masks the reality, namely that racism and discrimination lead to a systematic disadvantage for non-white ethnic minorities in the labor market, meaning that they confront limited occupational options. Audit studies in labor markets—sending identically qualified applicants for positions but with different surnames to represent white versus ethnic applicants—have consistently turned up employers’ bias about whom to interview or to call back for interviews (Bertrand and Mullainathan Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2004; Pager and Shepherd Reference Pager and Shepherd2008; Heath and Di Stasio Reference Heath and Stasio2019).

As job retention programs unwind in most OECD countries, many more people are expected to lose their jobs in the months to come and to remain out of work even as plausible vaccines gain regulatory approval and are rolled out. These job losses will most likely be concentrated in those sectors that relied heavily on government-sponsored furlough schemes. In the UK, for example, the highest percentage of furloughed employees are in hotel and food services (77%); arts, entertainment and recreation (70%); and construction (60%).Footnote 23 Of these sectors, ethnic minorities in the UK are particularly overrepresented in accommodation and food services: they are almost 1.5 times more likely to be employed in this sector than whites.Footnote 24 Although systematic evidence is not yet available, discrimination may also play a role in who gets fired and who does not.

Welfare State Disparities

Inequalities in the labor market are reproduced in the welfare state because access to comprehensive social benefits is often based on a person’s position in the labor market (table 1). Those with low-paid, temporary, or part-time jobs are either relegated to less generous social programs, such as means-tested unemployment benefits or social assistance or have no access to income support at all (Häusermann Reference Häusermann, Bonoli and Natali2012; Rueda Reference Rueda2015; Thelen Reference Thelen2019; Weir and Schirmer Reference Weir and Schirmer2018). The same holds for racial-ethnic inequalities in the welfare state, with the additional factor that a person’s migrant status influences their social rights of citizenship (Boucher and Gest Reference Boucher and Gest2018; Emmenegger and Careja Reference Emmenegger, Careja, Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012; Hooijer and Picot Reference Hooijer and Picot2015; Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury2012). In the United Kingdom, for example, between 800,000 and 1.2 million undocumented migrants could face intense hardship due to a lack of access to public funds, loss of income, and the limited operational capacity of charities, on which many normally rely for food support (D. Taylor Reference Taylor2020). Food banks have been inundated with new supplicants in the United States and UK since the March lockdowns. Another barrier for people from minority communities is that discrimination by case workers can hamper their access to support services (Hemker and Rink Reference Hemker and Rink2017; Keiser, Mueser, and Choi Reference Keiser, Mueser and Choi2004). This has been well documented for African Americans in the U.S. health care system (Michener Reference Michener2018), and now, too, stories of African Americans and BAME citizens with COVID-19 symptoms being turned away from hospitals without proper testing and care have emerged (Eligon and Burch Reference Eligon and Audra2020; Laville Reference Laville2020). More systematic research is needed to assess the role of racial bias in the treatment of people from minority communities during this health crisis.

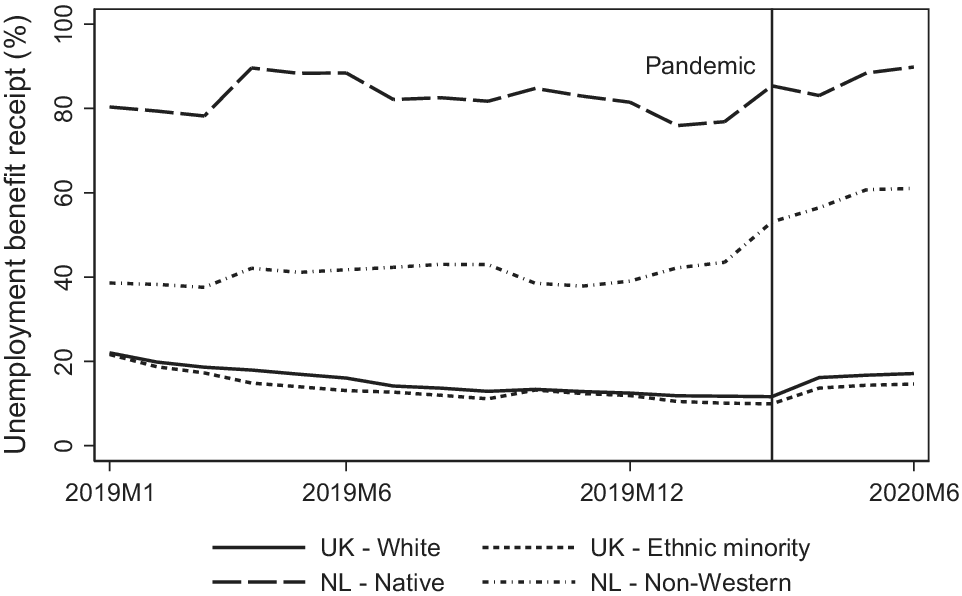

Workers may rely on a range of social programs during the current economic crisis, such as furlough schemes, sick pay, and unemployment benefits. Since recent data about the receipt of benefits by racial and ethnic background is limited, we focus here on differences in the receipt of unemployment benefits for whites and people from minority communities in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Figure 4 plots the number of (white/non-white) people receiving unemployment benefits as a percentage of all registered (white/non-white) unemployed in both countries.Footnote 25 Although coverage rates are substantially higher in the Netherlands than in the UK, we see that unemployed people from minority communities in both countries were less likely to receive unemployment benefits than unemployed white people before the onset of the pandemic. This configuration conveys the racialized patterns structuring welfare state provision in both states. The gaps are much larger in the Netherlands, where these benefits are more generous, than in the UK, where “universal credit” is meager and eligibility is calibrated excruciatingly. In the second quarter of 2020, the racial-ethnic gap in unemployment benefit mirrored these trends. However, we expect that the disparity across countries will expand as furlough schemes scale down and many people from minority communities will have exhausted their right to receive the more generous income benefits. There are already some early signs of this happening in the Netherlands where the number of people receiving social assistance has increased more rapidly among those with a non-Western migrant background (i.e., up 2.1% between March and June 2020) than among those with a native background (i.e., up 0.8% in the same period).Footnote 26

Figure 4 Unemployment benefit receipt by main racial-ethnic group

Discussion and Conclusion

How has the first wave of COVID-19 replicated racial and ethnic inequalities in the United States, the United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Sweden?Footnote 27 This question is at the center of our paper. Strikingly common shared outcomes across these four cases, independent of obvious differences in how each state’s political institutions are organized, how health care programs function, and how party mobilization occurs lead us to stress structural features shared across the countries—the cutting presence of institutional racism and discrimination—rather than to focus on comparative differences between the polities.

Our account marshals empirical evidence to show that people from minority communities are more likely to be infected by and to die from COVID-19 than the white population in these states, and that their high presence in occupations that do not allow for social distancing increased the risk of contracting the virus. The high presence of minorities in these jobs reflects enduring racism and discrimination built into Global North states. People from minority communities, furthermore, are hit harder by the economic crisis that has followed the health crisis: their unemployment rates in the United States and Sweden have increased faster than those of the white majority population, and there are early signs of this harsh trajectory in the UK and the Netherlands too, though they dampened most of the economic effects through generous job retention schemes shortly after the outbreak of the pandemic.

These patterns are present in other Global North democracies, even those that attempt not to document data on a racial-ethnic basis such as France and Germany.Footnote 28 The laudable liberal-democratic precept to treat all citizens equally (King Reference King1999) is belied by the generation of racial and ethnic disparities in socioeconomic and health outcomes, and reports from people from minority communities in these countries about encountering widespread discrimination in their day-to-day lives (Beaman Reference Beaman2017; Pitts Reference Pitts2019), including many Asian Americans post-pandemic.

Plainly, there are important nuances about the impact of racial and ethnic legacies in the four countries in need of detailed investigation. For example, the aggregate data for Sweden introduced earlier paints a picture consistent with the comparative pattern of higher vulnerability to COVID-19 infection for communities of color and migrants. But within Sweden there is variation: most of the Wave One incidents of higher infection have been in Stockholm and its satellite neighborhoods, whereas the areas around Malmo in the south of the country, which also house migrant communities, have been less exposed to the higher rates of contraction (Cookson and Milne Reference Cookson and Milne2020). The uncontrollable diffusion of COVID-19 has turned out to be non-random, felling the citizens and migrants already carrying the heaviest sinews of discrimination. In many cases, citizens whose parents were migrants have also been affected adversely. Future research may therefore look into comparing the outcomes of migrants and their descendants to isolate the role of migrant status as a determinant of greater vulnerability during the crisis.

How these patterns of racial and ethnic inequalities will unfold in the coming months and years is unknown, but previous research on economic crises can offer some guidance. This body of research has shown that minority communities, including migrants, are more vulnerable to job and benefits losses during economic crises (Dustmann, Glitz, and Vogel Reference Dustmann, Glitz and Vogel2010). Because they are more likely to work on non-permanent and part-time contracts, they are more likely to be self-employed, thus ineligible to receive government support in economic downturns (Constant and Zimmermann Reference Constant and Zimmermann2004), and to face discrimination in hiring and firing (Di Stasio and Lancee Reference Di Stasio and Lancee2020; Heath and Di Stasio Reference Heath and Stasio2019), patterns that reflect systemic discrimination.

The current economic crisis differs from the crisis of 2008–2009 in a number of ways (for example, the health dimension, the sectors affected, the degree of government support, the adoption of online working models, and the immigration restrictions), but looking back to that recession hints at what is likely to confront Global North states. To this end, we include long-term unemployment trends for the main racial-ethnic groups in the United States, UK, Netherlands, and Sweden in figure 5.Footnote 29 In all four countries the racial-ethnic gap in unemployment, which was already substantial before the 2008–2009 crisis, widened even further after the crisis. In most countries, it took several years for the unemployment rates of workers from minority communities to return to pre-crisis levels. In Sweden, their unemployment rates never returned to pre-crisis levels and instead stabilized at a higher level for the past decade.

Figure 5 Unemployment rates by main racial-ethnic group across economic crises.

It may strike some readers as unremarkable that societies in which racial-ethnic legacies already influence how health and labor markets generate inequalities replicate these dismal patterns under the force of a pandemic. The probability of working in highly exposed jobs results in vulnerability to infection and death, in a self-fulfilling cycle. But this logic does not explain why policy makers continue to underestimate the impact of legacies of institutional racism and discrimination on these Global North states outside the context of a pandemic; nor does this logic absolve governments of the responsibility to build up defenses for the most vulnerable groups who happen to be in that position because of how enduring ethnic hierarchies function. Until the 2020 election of Democrat Joe Biden as the U.S. president, none of these countries has taken additional measures to protect these vulnerable groups in society, such as making PPE available and mandatory in professions where high proportions of people of color work,Footnote 30 or providing adequate income support for workers while in quarantine.

Beyond the health and economic inequalities, the pandemic has proven to be fertile territory for xenophobia and racism. The Trump administration associated COVID-19’s emergence with China and aggressively framed the pandemic in America’s trade and political conflict with China, leading some Asian Americans to be publicly reviled. At a protest in Boston in March 2020, one placard read poignantly “My ethnicity is not a virus.”Footnote 31 The Trump administration also accelerated its already in place robust anti-migrant policy involving mass round ups and deportations of undocumented migrants by deploying dormant powers under the 1893 and 1944 quarantine public health laws to make blanket deportations of asylum seekers and unaccompanied minors at the Mexican border. By May 14, 2020, at least 20,000 people had been deported for these public health reasons, including 400 children (Guttentag and Bertozzi Reference Guttentag and Bertozzi2020).

Responding to widespread calls in the UK for an enquiry into the racialized virulence of Britain’s pandemic, Lord Simon Woolley who previously chaired a government advisory board in the official Race Disparity Unit, observed that COVID-19 “exposed and amplified areas of life that are deeply racialized such as low pay, zero hour contracts, overcrowded housing and inequality in health” (Campbell, Siddidque, and Walker Reference Campbell, Siddique and Walker2020). What Woolley might have added to this rueful inventory is the source of these racialized “areas of life” that, we argue, bleed out of the embedded patterns of institutional racism, sustained in labor market outcomes and health care disparities. The devastation of the COVID-19 Wave One pestilence has not fallen evenly on citizens in these countries but interacted fatally with national suffocating “spectres of race.” The racialized pandemic is a powerful signal of the almost boundless extent to which racial-ethnic inequality renders life perilous for many in the Global North. This fragility is commonly disregarded or played down in the short-term but––as mobilization orchestrated by the Movement for Black Lives demonstrates––is too hazardous and consequential a presence simply to fade away after mass vaccination. If the pandemic is to do more than shine “a magnifying glass on structural racism as a public health issue” (Cooper Reference Cooper2020), it must galvanize the urgent agenda to address institutional racism and discrimination (Marmot et al. Reference Marmot, Allen, Goldblatt, Herd and Morrison2020). This agenda must engage post-pandemic progressive politics.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Julia Lynch, Isabel Perera, Gina Gustavsson, and the journal’s anonymous referees for constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper. They are especially grateful to the Perspectives on Politics editor, Michael Bernhard for his editorial comments and support as the paper was revised.