Urbanisation during the Suharto regime (1967–98) transformed Jakarta into a beacon of authoritarian power as it centralised the government under the guise of ‘nation-building’ and ‘development’.Footnote 1 Succeeding President Suharto, President B.J. Habibie established an agenda to decentralise the state, encouraging the discourse of a democratic urbanism and a call to invigorate periurban areas. This article examines how urbanism in the post-Suharto era exists in the practices of contemporary artists in Indonesia. Two artworks addressing similar urban development projects are considered: 1001st Island — The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago (2015–16, henceforth 1001st Island), a multi-media artwork by Tita Salina, a Jakarta-based contemporary artist; and Dewa Murka (2016), a painting by Teja Astawa, a Bali-based contemporary artist. Both address major land reclamation projects.

Comparing the two artworks provides insight into the ways artists have been interrogating recent urban discourse in Indonesia. Salina and Astawa have both exhibited internationally yet have not received critical analysis of their practices. Urbanisation is not a new theme for Indonesian artists — it was part of the Culture Debate of the twentieth century, a national discussion among cultural practitioners motivated by an impulse to evaluate and compare the weaknesses, strengths and implications of the rapid modernisation taking place.Footnote 2 Among the artists involved in this debate was Sindusudarsono Sudjojono, a key member of the Persagi movement, which called for the end of the Mooi Indië (Beautiful Indies) style paintings of the 1930s. This dominant style in the early twentieth century was a colonial legacy that exoticised Indonesian life. Sudjojono called for art to reflect ‘reality’ and ‘truth’.Footnote 3 This inspired artists to consider everyday life as a subject. Artists such as Affandi, Agus Djaya and Hendra Gunawan began to focus primarily on human suffering. A split evolved among the leading painters of this period, over whether or not art should play a role in social and political movements. The generation of painters that followed evolved this discourse from a critique of imperialist evils to considering the suffering of those left behind during the modernisation of cities.Footnote 4 In the 1970s, the New Art Movement began to experiment with ideas from the Western avant-garde, applying commercial and mass-producing technologies to art and adapting the ideas to be contextually relevant to the region. Belonging to this movement, Djoko Pekik and Dede Eri Supria, prolific artists in the 1980s to 1990s, painted the labourers of mega infrastructural projects: train conductors, factory workers, and becak and bajaj drivers.Footnote 5 Further, writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer completed his book Jalan Raya Pos, Jalan Daendels: Essay dan narrasi in 1995 as a testament to the humanitarian injustices committed by the Dutch colonial government during the construction of the 100-kilometre-long Jalan Raya Pos (Grand Post Road, De Grote Postweg) through Java in the early nineteenth century.

Astawa and Salina's artworks are reflective of the societal problems that past generations of Indonesian artists have addressed, but both artists differentiate themselves by including environmental degradation in the problems affecting marginalised communities. This adheres to urban historian Abidin Kusno's proposition that environmentalism is a form and practice of power for the poor and middle classes in his discourse on green governmentality.Footnote 6 Comparing these two artworks provides insight into the ways contemporary art has been interrogating current urban discourse. Research into Indonesian urbanism largely focuses on Java, the most densely populated island hosting four of the nation's mega cities, including its capital, Jakarta. Hence this comparative study also challenges a Java-centric perspective in Indonesian urban discourse and art history. This article also explores the influence of the global and the local in Astawa and Salina's artistic practices, iconography, spirituality, art and activism, and their use of humour.

Urbanism in Indonesia

Pembangunan (development) is closely linked to the notion of kemajuan (progress): it has consistently remained in state discourse since Indonesia's independence in 1945.Footnote 7 Pembangunan manifests itself in visions for urban development, culture, religion, politics and the nation-state. As mentioned, urban development was predominantly undemocratic during the long Suharto era. The regime centralised the state under the guise of modernisation. Following the end of the Cold War, a seemingly prosperous and politically stable period drew to a close in Indonesia. The end of the era reduced foreign countries’ political interest in swaying the nation towards the West.Footnote 8 Suharto sought to combat this economically with a ‘Period of Liberalisation’. This changed land rights, allowing foreigners to buy and invest in new businesses. The result was a boom in the luxury market; skyscrapers were erected across major cities in Java; five-star hotels began to dot the coasts of Bali; and consumer culture adapted to international luxury brands. Economists termed Indonesia the ‘New Tiger of Asia’; inflation decreased, and the economy grew at an impressive rate of 7 per cent.Footnote 9 This prosperity encouraged a wave of rural–urban migration and a rise in protests calling for higher living standards. In an effort to combat the stress on cities, Suharto decreed Presidential Instruction No. 52/1995,Footnote 10 which called for the ‘periurbanisation’ of suburbs, to spread industry and control the population of city centres.Footnote 11

The Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 dramatically hit Indonesia's growing middle class. Adrian Vickers states that ‘Suharto's era of development and the subsequent age of globalisation had turned into the “age of crisis”’.Footnote 12 The end of the millennium in Indonesia was marked by political turmoil, violence and economic instability. The demise of an authoritarian regime led to a high turnover of presidents in the following years. The early 2000s saw the international broadcasting of the violence in Timor, Papua and several terrorist attacks across the nation — news that would have been heavily censored during the Suharto era.

Indonesia has since found relative economic and political stability. Nevertheless, it still faces challenges concerning inequality and the government has failed to significantly improve infrastructure to match demands for better living conditions. In September 2015, protests erupted across Indonesia calling for a rise in the minimum wage. President Joko Widodo (2014 to the present) has brought development back onto the agenda: in February 2016, he called for the re-liberalisation of land laws to encourage foreign investment.Footnote 13

Indonesia's major cities are continually transforming their landscapes to cater to fast-growing populations. In Jakarta alone, the population has grown from 1,452,000 in 1950 to 10,770,467 in 2020.Footnote 14 In the last three decades, green areas in the capital have been reduced from 30 per cent of the city to 10 per cent.Footnote 15 Environmental issues in the city include overpopulation, severe seasonal flooding, air pollution, a record-breaking sinking landmass and water scarcity. This has been exacerbated by the ‘back to the city’ movement wherein poor living conditions and collapsing industries in periurban areas have motivated sizable emigration.Footnote 16 The movement began in the late 2000s when periurban areas failed to provide economic opportunity.

Poor urban living conditions prevail despite regular protests against the state of the environment. The Indonesian state has adopted the concept of green governmentality in the ‘political rationality of governance’ as a means of addressing and controlling public frustration.Footnote 17 Kusno expands Michel Foucault's concept of ‘governmentality’ to be contextually relevant to contemporary Jakarta. Foucault's definition of governmentality refers to the institutions that wield power over a state's populations and mechanisms of security and knowledge production.Footnote 18 Kusno proposes a critical vocabulary that is applicable to governmentality in Indonesia, one that now strives to encourage clean and green development. Clean referring to more hospitable living conditions and green to an increase in vegetated areas. It should be noted that this does not necessarily mean environmental sustainability. Indeed, when integrated into the ‘back to the city’ discourse, ‘green development’ lures more people into already unsustainable, polluted cities.Footnote 19 Green governmentality has manifested itself in campaigns such as ‘Go Green’ in Jakarta.Footnote 20

Kusno notes the self-regulation taking place by Jakarta's residents stimulated by the contemporary forms of state power.Footnote 21 He argues that ‘a green environment requires individuals to reconfigure themselves to gain social legitimacy’, which ‘entails the displacement of those who are considered to be blocking the success of urban green initiatives’.Footnote 22 A contemporary tool of state power to encourage this self-regulation is the establishment of initiatives demanding public participation in green development. In the late 2000s, scholars, urban activists, architects, middle-class residents, investors and experts were invited as interpretative communities to engage in workshops that would form the urban policy of the nation's cities.Footnote 23 The outsourcing of urban planning from the government turned into a civic duty. This has wielded green discourse into an ‘accepted form of power’ for poor and middle-class communities.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, it has also given property tycoons the freedom to determine the landscape of their cities as long as they brand their projects as ‘clean and green’. The state has encouraged this through campaigns such as ‘Give Jakarta to the experts. If not, disaster is only a matter of time’, launched by Fauzi Bowo, Jakarta's governor from 2007 to 2012.Footnote 25 Such efforts have encouraged the proliferation of superblocks across the city, boasting luxury apartments, condominiums, entertainment and business venues, shopping centres, hotels and amusement parks in fully to semi-gated communities.Footnote 26 Ultimately, in response to early resistance against poor living conditions and the degradation of the environment, the state has used green discourse to shift the perception of accountability from the state to the public.

A recent manifestation of green governmentality has been the state's interest in land reclamation projects. Two are currently under way in Jakarta and Bali. These projects parallel a contemporary global trend. They are not just forms of territorial expansion, but also behave as sites for prestige on the international stage. Singapore, a beacon of modernity in the region, is constantly expanding its territorial reach — so much so that Indonesia had to ban sand exports to Singapore in 2007.Footnote 27 Its southern and eastern reclamation projects boast luxury homes, hotels, beach clubs and a thriving nightlife. Dubai has the Palm Islands, Abu Dhabi has its cultural hub on Saadiyat, and Hong Kong has a Disneyland theme park on Penny's Bay.

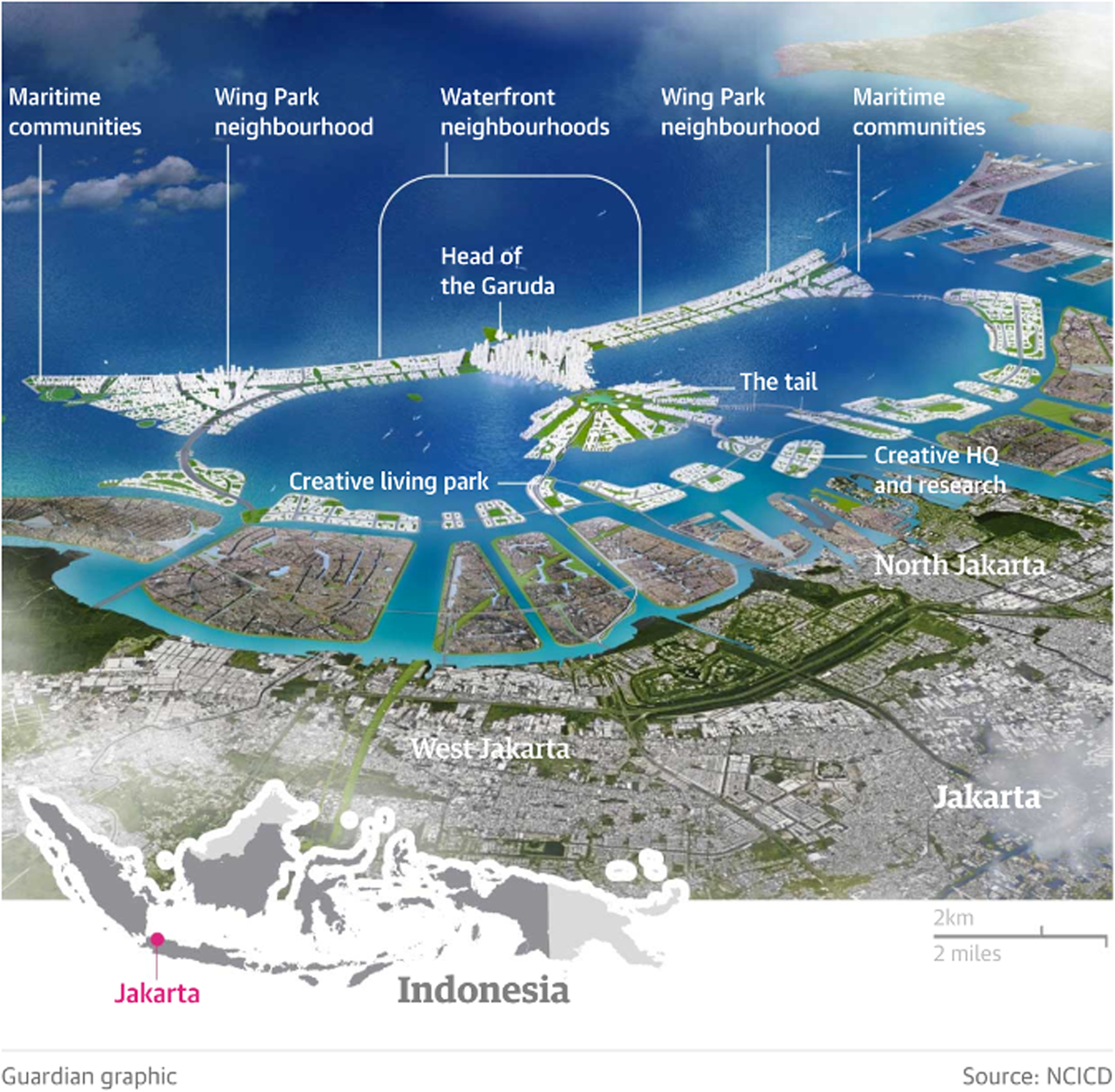

The major government land reclamation project launched in Jakarta is the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) project, also known as the ‘Great Garuda’. The project includes a 32-kilometre-long seawall and 17 islands in the bay of North Jakarta.Footnote 28 The reclaimed area will take the shape of a Garuda, the mythological bird which has had various meanings historically across the archipelago. Notably, the bird is the national emblem of the Republic of Indonesia, representing the ‘Garuda Pancasila’ (fig. 1), Pancasila being its founding philosophy. The NCICD promises to include new luxury residencies, working hubs and shopping malls. Before this scheme, Jakarta's bay had been largely neglected. During and since the end of the Dutch colonial era, this coastline has been associated with ‘imperial nostalgia’ and as a ‘contact zone’ for exploitative enterprises.Footnote 29 Since the late 1980s, the government has been working on rebranding the coast and encouraging Jakartans to come to terms with its history.Footnote 30 This reclamation project has been widely criticised since it was first proposed at the end of the Suharto era for, among other things, its failure to solve Jakarta's infrastructural and environmental problems.Footnote 31

Figure 1. Garuda Pancasila. Ari Welianto, ‘Lambang Garuda Pancasila: Makna dan sejarahnya’, Kompas.com, 19 Dec. 2019, https://www.kompas.com/skola/read/2019/12/19/160000769/lambang-garuda-pancasila-makna-dan-sejarahnya?page=all (accessed 29 Mar. 2020).

Such projects are often met with local resistance in Indonesia. Today, environmental and legal activists accuse developers of continuing the Suharto regime's legacy.Footnote 32 To confront this, green governmentality has been adopted to challenge this narrative. The government claims that the NCICD will alleviate population density and some critical environmental stresses facing the city, especially floods. Rather than solving the problems, however, critics argue that the NCICD is displacing the ecological and social problems Jakartans are facing by creating an entirely new territory for a particular demographic — namely, the middle and upper middle-classes who can afford the development's luxury housing. Further, reflecting Kusno's premise that green governmentality does not serve low-income populations, the project is displacing an entire community. The people of Muara Angke, a fishing village along that stretch of coastline, are being relocated and removed from their principal stream of income. Even reports by the Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry have concluded that the NCICD project threatens the survival of neighbouring islands and will harm the maritime ecosystem.Footnote 33 In addition to the decimation of fish spawning areas, the current plan connects seven of Jakarta's rivers in one area before they meet the sea (fig 2).Footnote 34 This will lead to eutrophication, fatally disturbing the ecosystem of flora and fauna of Jakarta Bay.Footnote 35

Figure 2. NCICD Programme plan, 2016. Screenshot from Philip Sherwell, ‘$40bn to save Jakarta: The story of the Great Garuda’, The Guardian, 22 Nov. 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/nov/22/jakarta-great-garuda-seawall-sinking(accessed 26 June 2017). Image reproduced courtesy of NCICD.

The NCICD project reflects Kusno's analysis of green governmentality. The institutions with the power to determine the urban landscape, namely the government and real estate developers, have appropriated the language of the poor and middle-class communities — demanding better living conditions in Jakarta — in order to advance plans that would predominantly serve upper-middle-class to upper-class communities. This meets Kusno's suggestion that the end result of green governmentality does not serve poor and lower-middle-class communities. In this example, the NCICD displaces the communities that may challenge the realisation of the urban development plans, marginalising the Muara Angke community from what would be considered the conditions necessary to live in a state of social legitimacy.Footnote 36 Instead of establishing social legitimacy within the existing population, it banishes those who do not reflect a prescribed standard of social legitimacy.

The second major project relevant to this article is Nusa Benoa, off the southeastern coast of Bali, currently Tanjung Benoa (fig. 3). The land reclamation project will be dotted with resorts, golf courses, tourist attractions and shopping malls, mirroring the plans of the Great Garuda in Jakarta. Nusa Benoa will increase holiday options in an already saturated tourism market. Between 1970 and 2006, the number of hotel rooms on the island rose from 500 to 130,000.Footnote 37 There is no longer the fast-growing demand to justify this scale of development as the number of visitors to Bali has reached a relative plateau.Footnote 38

Figure 3. Nusa Benoa plan. Screenshot from PT Tirta Wahana Bali Internasional, Nusa Benoa, ‘Concept: Our masterpiece’, https://nusabenoa.com/ (accessed 26 Apr. 2021).

Bali's environment, including its water and land resources, has been severely stressed by the demands of the tourism industry. The exploitation of Balinese culture (predominantly shaped by its Hindu-Buddhist religion), which is recognised as the island's ‘most valuable economic resource and tourist attraction’ has had an equally significant impact on society.Footnote 39 Threats to the foundations of this culture have fuelled social and political movements since the surge of tourism in the 1990s. Major tourist-oriented developments involving land reclamation around Serangan Island and Tanah Lot mobilised a range of groups including farmers and adat figures.Footnote 40 An additional threat to traditional Balinese culture has been the growing Islamisation of national politics. Movements have been organised to maintain tolerance between religious groups, exemplified by Ajeg Bali, which was founded following the Bali Bombings in 2002, a terrorist attack committed by fundamentalist Islamists who were not native to the island. Ajeg Bali (Bahasa Indonesia for ‘Bali stay strong’) sought to counter groups calling for revenge against fundamentalist Islam. Ajeg Bali called for the Balinese to commit to peaceful principles in their culture through ‘spiritual revitalization and cultural strengthening’.Footnote 41

A similar movement has grown in resistance to the Nusa Benoa project, calling for both environmental and cultural preservation.Footnote 42 Numerous sacred sites will be destroyed during the construction of the island. As a result, religious leaders on the island have threatened to commit puputan, a mass ritual suicide, which has not been practised since the early twentieth century, when it was enacted as a response to Dutch colonial aggressions against the Balinese rulers.Footnote 43 An anti-Nusa Benoa development resistance movement, ForBALI (Forum Bali Tolak Reklamasi, Bali's Community Forum Against Reclamation) formed in 2013, supported by religious leaders, musicians and the majority of the Balinese public.Footnote 44 In recent years, driving around the island, one will see the movement's large banners displayed along the streets, proclaiming a neighbourhood's allegiance. The organisation's official website lists the 186 traditional village councils and youth institutions in the ForBALI alliance.

Meanwhile, on Nusa Benoa's corporate website, words such as ‘revitalisation’, ‘sustainable development’ and ‘tradition’ are used to describe the multiple tourist attractions on the new island.Footnote 45 Branding the project as green reflects the discourse of green governmentality now pervading private development. As in the case of Jakarta's NCICD, Nusa Benoa's developers proclaim a narrative of green development, justified by a rationale of progress. The narrative of green development, originally demanded by the public in Jakarta for Jakarta, is being appropriated to ‘greenwash’ — the practice, mostly by corporations, of co-opting environmental credentials to cover contentious environmental records — a project that would serve a largely non-Balinese-owned tourism industry and investors instead of the local community.

1001st Island — The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago

Tita Salina (b. 1973, Palembang, Sumatra) was raised in Jakarta, where she is currently based. She studied Graphic Design at the Institut Kesenian Jakarta, graduating in 1991. In an established artist-duo with her husband, Irwan Ahmett, Salina performs in urban spaces, disrupting the everyday to question collective memory and a variety of social issues. Independently, Salina has developed a multi-media practice including performance art, installation, photography, and video art. One such body of work is Salina's 1001st Island — The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago (2015–16). Following its unveiling in 2015 at the 16th Jakarta Biennale, it has been exhibited and reproduced in various institutions around the world: including the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Street Art Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia; Kunsthal Charlottenburg in Copenhagen, Denmark; and Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

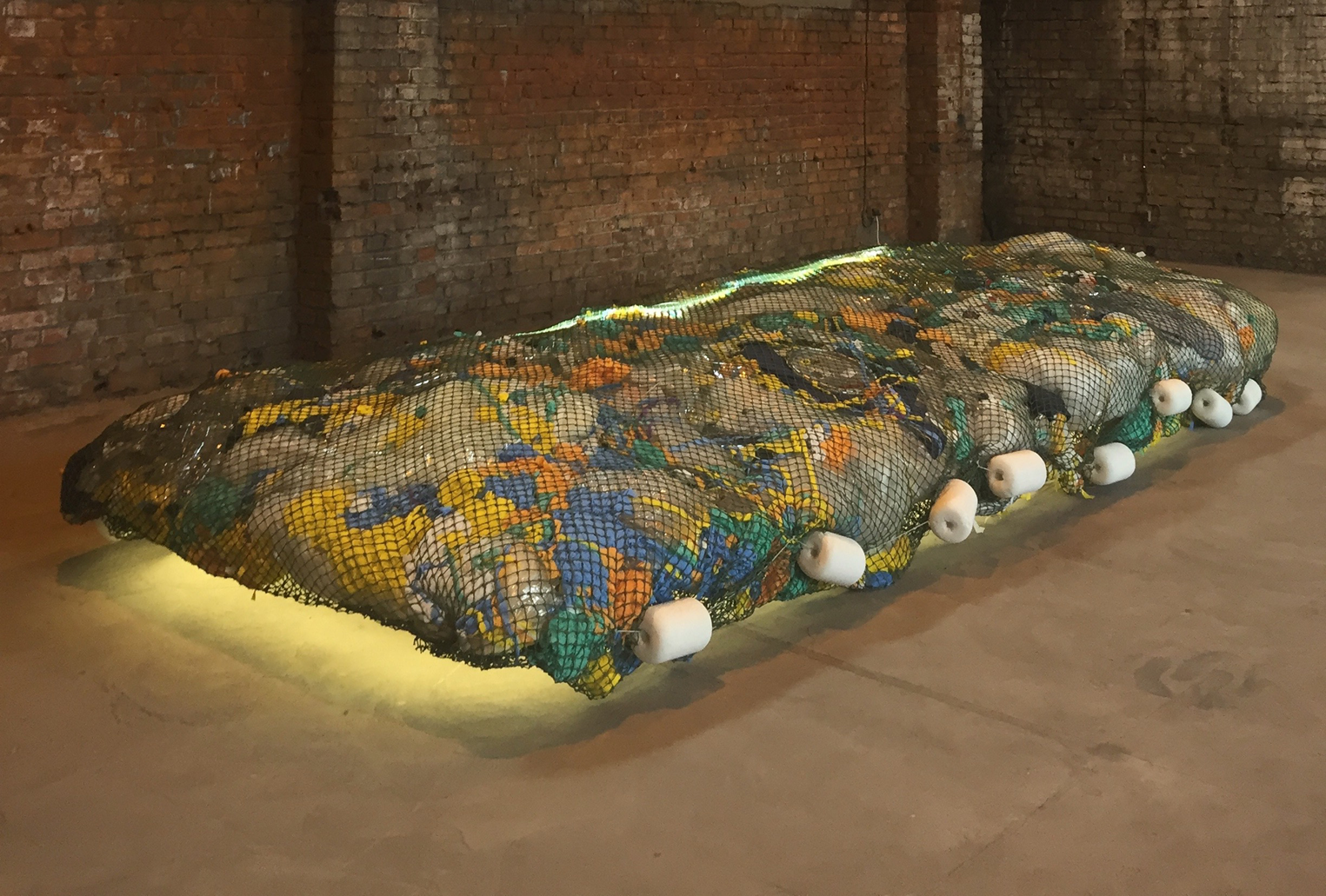

1001st Island is a multi-media artwork that includes a performance, an installation made of found objects and a video work. The video documents the performance and the making of the installation. The opening scene introduces the viewer to Muara Angke, a fishing village situated next to Muara Karang, Jakarta's main port north of the city. The bird's-eye view features the village in the middle; the river and sea that mark its borders; a vegetated wetland at the bottom; and a glimpse of urban Jakarta's skyscrapers at the top right-hand corner (fig. 4). The sound in this portion of the video is calm, with irregular and tranquil electronic beats. Next, the camera zooms in to Muara Angke's docks, which is crowded with small fishing boats. The music begins to dissolve into sounds of the everyday. The daily routine of the local fishermen at work is presented through their docking, unloading and sorting of fish on land. A break from this narrative occurs when the camera focuses on a man sorting through the rubbish that floats in the water along the docks. A camera is attached to an improvised contraption used to fork plastic out of the water, immersing the viewer into the pollution of the riverbank (fig. 5). This is the beginning of the installation's construction — the sourcing of the materials to create a raft. The rectangular raft is a fishing net stuffed with found plastic rubbish (fig. 6). It is carried out to the dock where it is towed out to the Java Sea (fig. 7). The shots are taken from different perspectives: on the boat, from the water, the raft, and from above. The boat passes part of the NCICD's reclaimed land, which is under construction (fig. 8). As it sails deeper out to sea, the recorded sounds fade into the music from the beginning of the video. This marks the beginning of Salina's performance. She boards the raft and the rope used to tow it is released. The raft becomes a floating island. Salina stands alone on the island (fig. 9). She lies down on the rubbish and the camera goes from a pan to a bird's-eye view, ascending above her. The video then closes with the credits.

Figure 4. Tita Salina, 1001st Island – The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, 2015, video and mixed media installation, 14’12’’, Still taken at 0’09’’ of video from artist's YouTube channel. Courtesy of Tita Salina.

Figure 5. Tita Salina, 1001st Island – The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, 2015, video and mixed media installation. 14’12’’, Still taken at 6’00” of video from artist's YouTube channel. Courtesy of Tita Salina.

Figure 6. Tita Salina, 1001st Island – The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, mixed media installation, Street Art Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, 2016. Photograph taken by author, 2016.

Figure 7. Tita Salina, 1001st Island – The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, 2015, video and mixed media installation, 14’12’’; Still taken at 7’43” of video from artist's YouTube channel. Courtesy of Tita Salina.

Figure 8. Tita Salina, 1001st Island – The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, 2015, video and mixed media installation. 14’12’’, Still taken at 9”36’ of video from artist's YouTube channel. Courtesy of Tita Salina.

Figure 9. Tita Salina, 1001st Island – The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, 2015, video and mixed media installation. 14’12’’, Still taken at 12’52” of video from artist's YouTube channel. Courtesy of Tita Salina.

There are three different sections in the video: a documentary of daily life in the Muara Angke community, the documentation of the installation's production, and a recording of Salina's performance. Each section calls for a separate reading. The word ‘documentary’ is employed because of the connotation it has with non-fiction. With this in mind, it is necessary to question the artist's employment of video to document the artwork and its contradiction to the ephemerality of performance art. Salina notes that she does not consider her videos as purely documentary, but a combination of a documentation tool and an artistic medium.Footnote 46 She considers it the best medium to document her ‘temporary created events’.Footnote 47

The temporary events in her practice are often collaborative, incorporating the participation of the community local to the artwork's subject. Drawing on Grant Kester's The One and the Many, where he considers the relationship several participatory artworks have with labour and power, it is relevant to question what the symbolic meaning of labour is in this artwork.Footnote 48 In the first section, the community is homogenised. This is done through depicting the landscape and fishing industry as essential signifiers of this group — Salina establishes an identity without introducing us to any individuals. In the next section, presenting the collection of plastic waste and the assembling of the installation, the viewer is introduced to the people involved in the production of the raft. The viewer is only introduced to these individuals based on their role in the creation of the installation. Salina presents an object created by a community, not by independent and self-directed contributors. They carry the installation together and launch it into the sea.

Salina is not seen in these first two sections of the video; she is extracted from the everyday. There is no verbal engagement between the artist and the community. This controls the narrative to provide the illusion of a synchronistic collaboration between the two parties involved. This echoes the division Kester remarks between the artist's labour — which is the act of creation — to the second, hermeneutic labour — which is the labour of the viewer.Footnote 49 The artist's control over the narrative disallows the potential for a third perspective — that of the collaborators, which could influence the viewer's interpretation of the narrative. The viewer has to determine the different meanings in the video's three distinct parts. In the final section, Salina literally and metaphorically detaches herself from the group in the boat, and drifts into the seascape, away from the community that provided her with a raft.

As well as the different events taking place in each section, the distinctions in the video are marked by technical and musical differences. Salina's performance in the last section has an aesthetic quality, as art and not documentary. The colours are more cinematic and the image quality is crisper. The first section seems less orchestrated. The improvised contraptions and hand-held camera quality provide a sense of immediacy and authenticity (fig. 5). The viewer feels immersed in the experience of the river, literally being plunged into the water, and is guided to think about the living conditions of the fishermen in Muara Angke.

Another conscious technical decision was the use of a drone for aerial views. It is used throughout the film, rendering bird's-eye views of Jakarta's landscape. The drone sequences contribute a sense of scale and juxtaposes realities. In the opening of the video, when North Jakarta is introduced, the drone records clashing landscapes. Central to the image is the slum-like fishing village of Muara Angke. To the left across a strait is an almost idyllic vegetated section and to the right of Muara Angke is a glimpse of Jakarta's hyper-urbanised area, with skyscrapers puncturing through the haze. The skyscrapers appear as icons of a prosperous global economy, in comparison with the hard-labouring fishermen's boats and huts. A similar juxtaposition reappears in the final segment of the video when the raft is being towed out to sea. The tiny fishing boat, tugging the floating rubbish, is almost comically small compared to the massive land reclamation project under way (fig. 8). The drone footage allows them to be seen in the same frame, and this comparative scale delivers a sense of the hierarchy of urban development.

The use of drone technology invites a sociological reading of the video and is linked to the rise and discourse of private development addressed earlier, specifically the NCICD. Throughout 1001st Island, Salina connects this land reclamation project with the plight of the Muara Angke fishing community.Footnote 50 There is also an illusion of agency, however. The fishermen are depicted as willing participants and collaborators in the creation this artwork, but ultimately, the control of the final product is in the hands of the artist. The message of the artwork is delivered through the purposeful direction of the artist. Although the second portion of the video gives the illusion of a documentary style, it has not been created from a passive observational viewpoint. Nothing occurs by chance in the frames. The viewer is led to a certain conclusion. This degree of control is masked through the juxtaposition of an unmistakably orchestrated performance in the end.

The illusion that the fishermen have agency in determining how they are represented in Salina's artwork mirrors the misconception of self-determination citizens believe they have when participating in green discourse to influence urban development. Such misconceptions and illusions are created by the state to extinguish resistance while powerful actors — such as property magnates — use their stronger resources to determine the final outcome of these initiatives by employing the same language of green discourse. While the NCICD's proponents claim that the development will improve the living conditions of Jakartans, it will solely provide an escape from the city's problems for those who can afford to live there. It will not solve the infrastructural issues plaguing the city's marginalised communities. While property tycoons and others are set to profit from this, the city's fishing and waterfront communities are being forcibly removed — losing access to their sole means of economic subsistence. Since the making of this artwork, large portions of the Muara Angke community have been forcibly evicted.Footnote 51

The installation accompanying the video (fig. 6) is also a document of Salina's performance. For each enactment of 1001st Island, she re-creates the raft and interacts with a different community of citizens local to the performance. They aid her in the sourcing of found rubbish. This collective effort is central to Salina's practice.Footnote 52 It is also deeply reflective of gotong-royong (working together), an important principle in Indonesian society.Footnote 53 The concept is a pillar in practising Pancasila, the country's founding philosophy, and speaks to the communal effort required to meet people's needs. Using this, Salina hopes to investigate what the habits and needs of a society are in the localities of her performances. When performing 1001st Island in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, Salina comically reflects on the irony of the quantity of beer cans she collected from the sea of a Muslim-majority country.Footnote 54 By revealing this observation during the exhibition through a new raft of found materials, Salina provides the local audience with an opportunity to reflect. They can question who the consumers are; why the rubbish is being discarded in the ocean; and what can be done socially, as well as in terms of urban infrastructure, to address marine pollution and the hypocrisies the artwork reveals. It is not Salina's intent to judge the situation, but rather to be a ‘message carrier’ and to encourage her audiences to reflect and interpret.Footnote 55

By exposing local environmental problems and state, corporate and societal hypocrisies, Salina is able to hand back power to the community engaging with the work, as if to say, what next? Further, because Salina encourages a non-artworld public to engage in her work, she hopes it will speak to those who need the solutions to these questions the most.Footnote 56 Her conscious approach to knowledge creation is relevant to concerns addressed by Kester regarding the difference in experiences between the participants of the artworks and the viewers in an artworld framework.Footnote 57 Salina's artwork suggests that re-enacting its production and performance in each geographical location it is exhibited in serves the participants that create it, and not the viewers. In this way, Salina ensures that the work remains relevant to its context. Nevertheless, what remains, which Kester argues to be a weakness of such artworks, is the form in which these works are re-represented. Kester argues that the weeks of effort and ‘complex social and organisational network’ involved in the realisation of such projects are rarely included in the documentation of these performance pieces.Footnote 58 This criticism can also apply to 1001st Island, which in effect leads the participants involved to be used as figures in a ‘social allegory’ instead of as collaborators.Footnote 59 The agency that is lacking in the process, that of the Muara Angke community, is in turn given to the viewer, encouraging this outside group to take action against or reflect on the hypocrisies and illusions of self-determination. As with green discourse, a marginalised community is entrapped in a power structure that uses participatory initiatives to provide the illusion of agency. The community participating in such forms of civic discourse generally has the least resources to effect the change it seeks — in this artwork, it is the fisherfolk of Muara Angke who have laboured to create its centrepiece yet are not in control of their own representation.

Dewa Murka

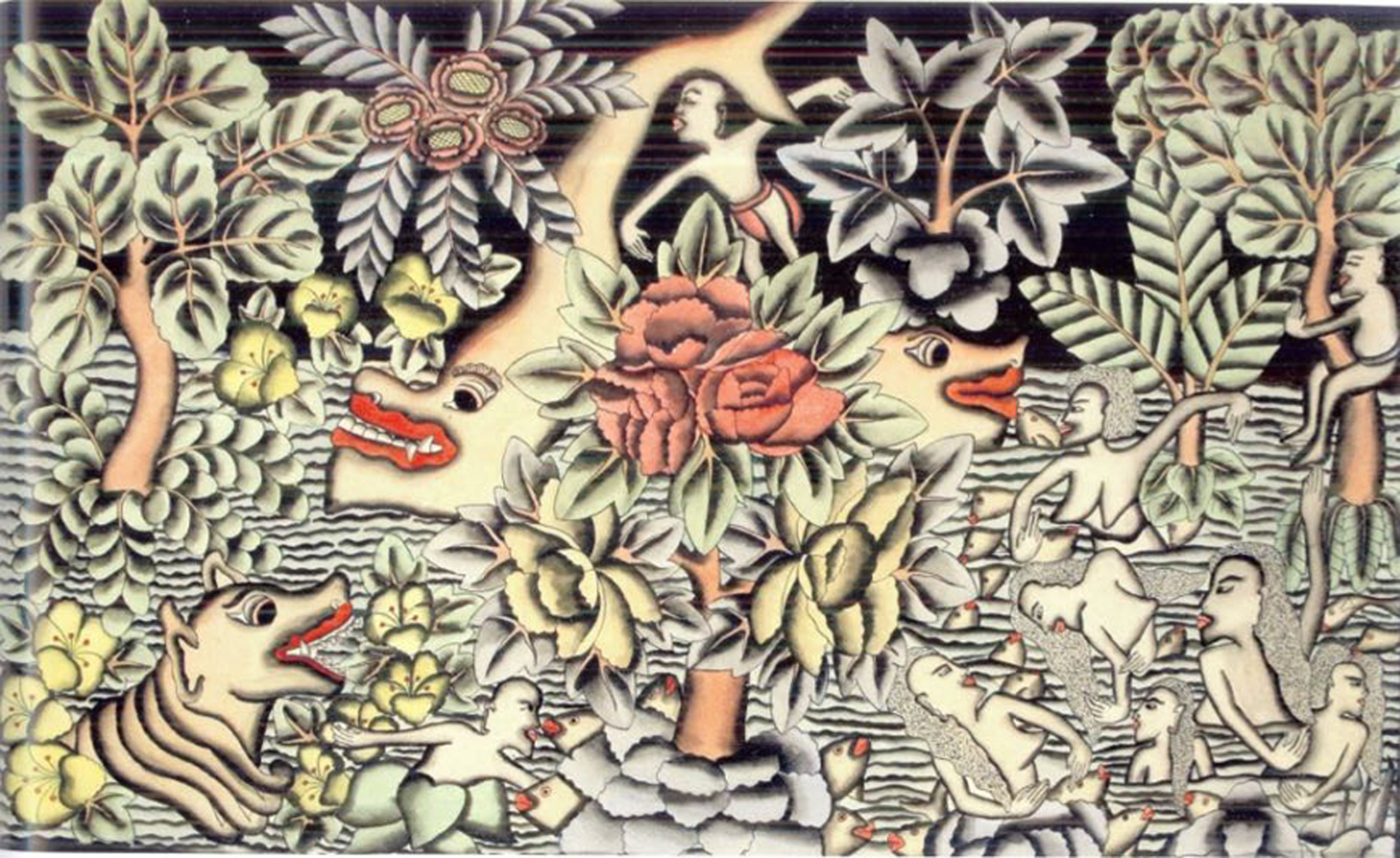

Ketut Teja Astawa (b. 1971, Bali) graduated from Institut Seni Indonesia Denpasar in 1990 and is currently based in Sanur, Bali. Working predominantly with acrylics on canvas, Astawa's paintings often include caricatured animals and deities from Hindu mythology. While Hindu myths are commonly rendered onto canvas, lontar (palm-leaf manuscripts), or paper in Balinese art, this rich tradition has a strict formal iconography. Caricaturing iconographic characters is more commonly practised in Java.Footnote 60 Astawa also draws from events in his childhood, daily life and his subconscious,Footnote 61 and his juxtaposition of mythology and the everyday deserves examination. Culturally, the interconnected concepts of sekala and niskala (the seen and unseen worlds) need to be addressed to comprehend how they operate in Balinese daily life. Typical of Astawa's style is a degree of naivety, through style and form, represented in his childlike figures, frequent representation of animals and relatively gentle colour palette.

Dewa Murka (fig. 10) is a large acrylic and ink painting on canvas that features a dynamic seascape. It is divided almost equally into a top and a bottom portion. The top portion of the piece is a dark sky, with non-figurative shapes, numerical equations, and English and Bahasa Indonesia text. It can be likened to a traditional school blackboard with text written in chalk. The bottom depicts the sea, and in the bottom left corner, a sliver of beach with two male sunbathers. A giant mythological male figure rises out of the sea in the centre-right. Based on the title, we can assume that this is Dewa Murka (‘God of Wrath’). Surrounding Dewa Murka is an energetic scene of mechanical diggers and boats ploughing through water. The sea is dotted with men dressed in traditional attire, sarongs and udeng (Balinese headgear). The men are in distress, struggling to escape the mouths of fish. There is also a small house that is sinking under the waves. What or who is causing the havoc, the diggers or Dewa Murka?

Figure 10. Teja Astawa, Dewa Murka, 2016, acrylic and ink on canvas, 140 cm x 300 cm; courtesy of the artist.

The sea's waves are painted in contrasting tones of blue and white, emphasising the motion in the water. This style is reminiscent of the Batuan paintings traditionally produced in northern Bali. The style is less rigid than the forms and narratives of the Kamasan or Ubud style. Batuan paintings often depict scenes of nature with humans rendered as small figures.Footnote 62 Depicting sakti, a magical force which permeates the visible and invisible worlds, is a priority in Batuan painting.Footnote 63 The conflict between good and evil, seen and unseen, is stressed in their strong black and white tones. They struggle against one another for balance, embodying a third space, the whole. This is reflective of a cultural philosophy that resonates throughout Java and Bali, finding a balance between good and evil by challenging the idea of them as dichotomous — a central notion in Western Christian cultures.Footnote 64 Another dichotomy challenged in Dewa Murka is night and day. It is hard to ascertain whether it is night or day as the sky is black with star-like figures, while the men on the beach are sunbathing. They appear to be depicted as occurring simultaneously, rendering time as relative.

Dewa Murka's content is also representative of the Sanur school of art. Although Astawa was not trained through a traditional apprenticeship, his use of Balinese mythology and style reflects his knowedge and lived experience of Balinese tradition and spirituality.Footnote 65 Before a formal arts education was introduced in 1970 at Udayana University in Denpasar, apprenticeships were the main pedagogical model.Footnote 66 Art historian Helena Spanjaard suggests that this is the main reason why a Balinese ‘modern’ is rooted in traditional art, in comparison to the modern art of Java, which is a product of Western art school pedagogy.Footnote 67 Nevertheless, his lessons at the fine art school may have contributed to Astawa's freedom to leave the confines of traditional rules of representation. Further, Astawa also attributes his choice of content as a means of reflecting on his childhood, during which he often made his own wayang (shadow) puppets from leaves.Footnote 68

The Sanur school, developed in the late 1930s, is the only Balinese art style wherein sea scenes were depicted. Spiritually, the Balinese believe that the sea is a place full of dark forces and depictions of it only began when they were commissioned for the tourist industry.Footnote 69 Stylistically, the Sanur style is lighter, not bound by religious iconography, and filled with decorative patterns and marine life. While reminiscent of Batuan painting, the repetitive flowing lines of the water in Dewa Murka are also common in the Sanur style (fig. 11).Footnote 70

Figure 11. Ida Bagus Sodang, Bathing People and Animals, 1937, coloured ink drawing on paper, 35 cm x 56.5 cm. Scan from Helena Spanjaard, Pioneers of Balinese painting: The Rudolf Bonnet Collection (KIT, 2007), p. 96.

With regards to the identification of Dewa Murka, we can be certain it is a deity because of the halo surrounding the body and the title. Yet, ‘Dewa Murka’ does not specify any particular god. Not only is this ambiguity typical of Astawa's practice, it is also common practice amongst the Balinese when describing their gods in Indonesian and English.Footnote 71 It is reasonable to assume that it represents Baruna, better known in Bali as betara segara (‘deity of the sea’), the Balinese rendition of the Hindu Varuna, the god of water and the cosmic underwater world.Footnote 72 The god is worshipped through offerings as big as entire ships.Footnote 73 There are too few images to conclusively compare Dewa Murka with what would reliably situate it amongst a prescriptive iconographic representation of Baruna in Indonesia.Footnote 74 In India, Varuna is depicted as an anthropomorphic elephant riding the makara, a crocodile-like figure from the Puranas. In Indonesia, there are two recorded figurations that have been linked to Baruna.Footnote 75 Further, the god is also worshipped at dedicated sites, including the Tanah Lot temple in Tabanan, Bali. The deity has been depicted in wayang puppetry with scales, shells, jewels and lotus flowers.Footnote 76 Ultimately, this deity is responsible for maintaining the marine ecological balance.

Upon initial observation, Dewa Murka presents a chaotic scene where a force is causing havoc in the ocean. The text–image relationship between the ocean's dynamism, through the numerical equations and written text, bring to mind a narrative of climate change and the documentation of changing temperatures. When asked about his use of text, Astawa stated that ‘Teks itu adalah memberi kesan suatu cerita. Pada lukisan Kamasan, teks itu sering ada. Idenya dari lukisan Kamasan’ (The objective of the text is to give the impression of a story. Text is common in Kamasan paintings. The idea is from Kamasan painting).Footnote 77 By including Indonesian and English text and numbers, Astawa has varied the legibility of the work for an international public. The legibility of Dewa Murka will be revisited in the final section, when comparing the two artworks. There is evidently a message or story attributed to Dewa Murka. Despite our conditioning by popular media to jump straight to apocalyptic conclusions when climate change is the theme, Astawa's main concern is the degree of balance between tradition and its struggle with neoliberal, capitalist values and Western science and knowledge systems that are stressing his home island culturally and environmentally.

Assigning an antagonist would be one-dimensional and reduce the work, especially if all wrongs are attributed to the deity. In a Euroamerican Christian mindset, good and evil are dichotomised and this manifests in physical traits such as obesity being automatically associated with gluttony or indolence. Benedict Anderson stresses that we should not look at the physical traits of characters in various Indonesian traditions as metaphors of good and evil.Footnote 78 Although they may seem evil at face value for having repugnant features, their morality is ambiguous depending on the caste of the character, the tale being told, and the context in which it is told. Sinful traits might lead to morally positive outcomes. This is an important facet of moralism in Javanese and Balinese cultures that should not be overlooked; Anderson cites this ‘sense of relativism’ as an oft-misrepresented tolerance.Footnote 79 Although Anderson focuses primarily on Javanese culture, relativism is still applicable to understanding Balinese culture. This is exemplified in the Saput Polèng, a plaid black, white and grey cloth, which adorns temples and holy trees. It is a visual reference to balance and the role of relativism in the universe. Night needs day and black needs white. Some of these — black and white, evil and good — live in the visible world, sekala. The distinctions between these dichotomies, or the lines between the black and the white (tonalities and moralities), preside in the invisible world, niskala. Footnote 80 Without one, the other could not exist. Relativism, understanding that good can come of a bad event and vice-versa, is a fundamental philosophy in Bali.

This relativism is necessary to consider when analysing Dewa Murka. When asked about his optimism for the future of the environment, Astawa responded ‘Kalau di Bali masih memegang kuat budaya & tradisinya, saya yakin alam akan dijaga dengan baik’ (If we hold on tight to culture and tradition in Bali, I am sure the natural environment will be maintained well).Footnote 81 Astawa invites viewers to consider what is at risk if the Balinese lose touch with tradition — the environmental well-being of the island and its sea. Using Balinese iconography, Astawa evokes the past, culture and traditional practices. Dewa Murka is in conversation with Nusa Benoa, the land reclamation project detailed earlier. Superficially, we might assume that it is Baruna who is causing havoc. Rather, there is an open discourse with the public that they are able to influence the state of the ecosystem by interrogating their own spirituality. Nevertheless, the public are not the sole carers of this environment, they are representative of the force that can take effect in the visible world, sekala. Within niskala, the invisible world, this will be effected by Baruna. They must work together. Astawa's spirituality and faith in the environment is strong, and he often links the state of one to the other in his art. Within his artistic practice, ‘adat dan budaya itu harus dicintai’ (custom and culture must be loved).Footnote 82

Comparison and evaluation

Rapidly changing city landscapes coupled with poor environmental and living conditions are encouraging Indonesians to demand a re-evaluation of urban development policies. Artists today are interacting with these challenges in a different way from their predecessors. As mentioned, urbanisation is not a new theme in Indonesian art, but contemporary artists are deviating from the primarily social justice concerns of the New Art Movement in the late twentieth century. As well as re-evaluating the problems caused by urbanisation, contemporary Indonesian artists are proposing new methods of addressing them. Although Tita Salina and Teja Astawa are both concerned with their respective land reclamation projects from a social and environmental standpoint, they use widely differing media while simultaneously engaging with their local communities. Both the artworks discussed here employ methods of crossing cultural boundaries, but each retains a strong sense of its locality. Comparing them provides insight into some of the different forms of urban green discourse in Indonesian contemporary art.

Both the NCICD in Jakarta and Nusa Benoa in Bali are projects that have been criticised for failing to address the growing inequality in their localities. The housing in the NCICD plan is primarily directed at middle and upper-middle class families, and Nusa Benoa will largely benefit the predominantly non-Balinese-owned tourist industry. In the video portion of 1001st Island, Salina not only visually juxtaposes the Muara Angke fishing boats and huts with the city's skyscrapers, but also includes the fishing community in the production and performance of her artwork. The collaborative project bears to mind gotong-royong, mentioned earlier. Collaborating with the public is prevalent across Salina's practice. In this artwork, Salina works directly with local fishermen to collect trash for the raft and to tow it out to sea. By doing so, Salina states that she hopes to lessen the distance between artists and their diverse audiences.Footnote 83 This parallels the contemporary forms of power that construct green governmentality, where the state encourages participation from Jakarta's residents, to establish a sense of civic duty. The essence of this collaborative spirit exists in Salina's practice, which seeks contributions from local communities. She has also worked with a range of relevant stakeholders, such as nongovernmental organisations, FHI360 (under the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United Nations Economic, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and Red Cross Indonesia.Footnote 84

Together with Iwan Ahmett, Salina's performances predominantly take shape in marginalised urban settings. This proposes a new space for knowledge to be transferred between the artist, the community, and the audiences of the final work. The space for the creation of knowledge is one of the reasons why Salina re-creates the raft in situ each time she re-enacts the performance, hence the observation about beer consumption in Sharjah. Similarly, during Salina's performance in Copenhagen, she found that drunken residents would often throw their bicycles into the canals.Footnote 85 She is able to interact with, interpret and present different habits and concerns in each community.

The differences between Salina's and Astawa's artistic mediums largely define the type of engagement they have with their local communities. Working on canvas, Astawa's work lives in a more conventional artworld circuit of galleries, museums and art fairs. In the artwork itself, Astawa's relationship with his community is concentrated in the depiction of the community, not in a collaborative process. A significant aspect of his practice is to draw inspiration from Balinese tradition and spirituality, however, and observe how they are mediated with the demands of contemporary life on the island. Dewa Murka does not necessarily provide a solution or judgement concerning the creation of the Nusa Benoa enclave through land reclamation. Rather, the work suggests that Dewa Murka will respond to whatever happens, based on the conditions that people offer the deity. Astawa does not oppose an intervention in the ocean per se, but specifies that the way this is done is what matters for the environment and his local community.Footnote 86 The proposition that the local community is responsible for its future is stressed in the juxtaposition of the relaxing tourists with the local men struggling in the water. The responsibility is transferred onto the public, much like when the state in Jakarta imposes responsibility on its citizens through the methods of green governmentality. The localisation of individuals in Astawa's painting is illustrated in their attire.

Although the medium and process involved in creating Dewa Murka do not reflect those employed in green governmentality in Indonesia, there is a similarity in their narratives. Kusno argues that the state has provided opportunities for local communities to begin actively participating in environmentally sound urban development.Footnote 87 Eventually, this has translated into campaigns that stress new forms of civic duty. Citizens become the parties that will determine the future of their urban landscape and its conditions. The accountability of individual citizens is also stressed in Dewa Murka, as Astawa believes in the preservation of tradition as a form of determining the future. Thus, there is an established narrative that is reflective of civic duty characteristic of Indonesian green governmentality.

Another aspect worthy of comparison is the irony and humour that exists in both artworks. Irony is a recurrent technique in 1001st Island. The title itself is a play on the work's site-specificity when performed in Indonesia and juxtaposed with the raft's inhospitableness. The number 1001 refers to the group of islands, or ‘mini archipelago’, that is known as Pulau Seribu (‘thousand islands’) north of Jakarta.Footnote 88 Salina suggests that adding another number disfigures the beauty of ‘1000’.Footnote 89 By testing the boundaries of what can be included in Pulau Seribu, it questions the artificiality of land reclamation and how such projects merge into their surroundings. Further, the irony of proclaiming it as the ‘most sustainable’ island comments on the raft made of urban trash being uninhabitable. NCICD will not be a self-sufficient urban enclave. The capital will still be the main supplier of services, labour and goods. Thus, the plans for a new ‘clean and green’ site, terms prescriptive of green governmentality, are at the expense of further economic, infrastructural and environmental pressure on Jakarta. Lastly, irony continues in the materiality of the raft and Salina's performance. The plastic rubbish is a very literal reference to inhospitableness and Salina's solitude on the raft provides no chance for sustained human existence.

In Dewa Murka, humour exists in Astawa's style through its naivety. Its light colour palette and simple shapes sidestep the gravity of the subject itself. Further, he employs caricature as a tool to play with and mock well-known cultural symbols, in this case Balinese iconology and symbols of modernity. Using humour with traditional iconography is a practice that is common in Indonesia. Astawa is heavily influenced by wayang in his practice. Vickers discusses how nationalists used stamboel (a form of comic theatre during the Dutch colonial era) as a means to discuss Indonesian independence with the masses in plays.Footnote 90 Humour is employed in order to alleviate the gravity of certain, often taboo, subjects. Astawa uses this cultural tool to relate environmental degradation to the spiritual sanctity of the island and its community. Dewa Murka invites us to consider our own impact on Bali, its culture and tradition, with regard to the demands of contemporary life and tourism.

The playfulness of both Astawa and Salina's practice invite chance in the creative process of both works. With 1001st Island, the acts of performance and collaboration open up a myriad of opportunities for things to stray from a set narrative. Astawa's practice might summon more artistic planning at face value. Dewa Murka does have a certain logical composition, with the most powerful character taking a large and central position in the painting. Nevertheless, Astawa has stressed that giving his subconscious the opportunity to come forward in his paintings is essential in his practice. In one of Astawa's exhibition catalogues, the collector and gallerist Tony Hartawan shares an anecdote about what led to the title of his 2010 work, Monkey Attack (fig. 12). Astawa had developed the work to comment on the behaviour of tourists in Bali, often representing them as monkeys in his oeuvre. When Hartawan came to visit his studio, he asked whether the work had any relation to the Bali Bombings in 2002 and 2004.Footnote 91 This came to Hartawan's mind because of the comic blast that is painted in the sky of the work. Astawa admits that he did not intend to draw that conclusion but did alter the title of the work impulsively as a result of this conversation.Footnote 92 He suggests that being open to change, and chance, during the creative process allows his subconscious to engage in his practice. Astawa's allowing for chance and the subconscious should be taken into consideration when viewing or interpreting his body of work.

Figure 12. Teja Astawa, Monkey Attack, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 150 cm x 200 cm. Photograph of work from Tony Hartawan, Fragments of subconscious memory: A solo exhibition by Teja Astawa (Bali: Tonyraka Art Gallery, 2011), p. 26. Courtesy of Teja Astawa.

With regards to Salina's art, chance is stimulated. The use of performance is a means to invite flexibility, not theatre.Footnote 93 This flexibility relates back to the collaborative nature of her work, hoping that providing a space for the unexpected will give agency to the communities participating in her performances. When interviewed, Salina compared herself to an anthropologist, hoping to learn about the habits of different societies through art.Footnote 94 Being open to chance also enables Salina to comfortably manoeuvre through different cultures. Despite societal differences, Salina believes that everyone is essentially the same.Footnote 95 By employing humour as a language, she claims communication becomes universal in a manner that is not patronising.Footnote 96 Within re-enactments of 1001st Island, the raft and performances manifest different meanings and relationships. Nevertheless, the conclusion always includes the proposition that everyone is contributing to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, also known as the Pacific trash vortex.Footnote 97 This is an immense mass, consisting of man-made rubbish, that floats in the Pacific Ocean. Natural currents drive plastic waste made globally to this major meeting-point.

In Salina's practice, chance is necessary for cultural mediation. In comparison, Astawa may use chance to influence the meaning of his work post-creation, as in the change of a title. Unlike Salina, Astawa uses text as a means of mediating culture in Dewa Murka. In an article on Balinese art versus global art, Vickers examines the difficulties artists from Bali have with the multiple modernisms that have developed over time, and the failure of academics and viewers to distinguish modern Balinese art from traditional and classical art. He argues that for a Balinese artist to find international success, they must often leave the island and detach themselves from their identity. This is the result of high culture being cast aside in favour of tourism on the island. He suggests that in order for Balinese artists to make it beyond the local, they need to make their work ‘intelligible’ to an Indonesian and international audience.Footnote 98 Although labelling Astawa's art based on his Balinese identity is problematic in itself, by including text, Astawa makes a compromise. Including Balinese iconography renders him true to his tradition while text promotes a global legibility. This has also been achieved by breaking down strict formal iconography. Textually, there are multiple forms of legibility: English, the language of the global artworld; Bahasa Indonesia, the lingua franca of the nation (instead of the Balinese script); and mathematical equations, arguably a universal language. This is a tool that appears in Astawa's practice after 2012 and can be likened to the stance of Nyoman Masriadi, the most successful contemporary Balinese artist. Vickers’ notes that Masriadi ‘does not want to be known as a “Balinese artist”’ and employs these tools to make his work legible to a more global audience.Footnote 99

Ultimately, the mediums and tools that both artists adopt influence the audiences that can engage with the works and the meanings that are ascribed to them. Dewa Murka requires a degree of Balinese iconographic knowledge to mediate the tension between human contribution and Baruna's behaviour. Nevertheless, such knowledge is not required to comprehend that the ecology of the environment is in distress. The mechanical cranes in conflict with nature can be considered as globally legible imagery. 1001st Island mediates its cultural legibility through its re-enactments. The title, original performance and video is extremely specific to the NCICD project in Jakarta, yet the collaborative nature of the work invites continual reinterpretation. Specific conclusions are drawn about the societal and consumption habits of each site without losing sight of what binds them together.

Conclusion

Urbanisation in Indonesia entered art discourse through the sufferings of those left behind during the nation's modernisation. This awareness still firmly exists in the two analysed works. In Dewa Murka, Astawa questions the sanctity of Nusa Benoa and the environmental consequences that might ensue if traditional and cultural ecological stewardship are lost to the pressures of tourism on Bali. In the video of 1001st Island — The Most Sustainable Island in Archipelago, Salina visually contrasts parallel living conditions existing within a single landscape. A key difference between these two artworks and the art of their predecessors in the late twentieth century is that Astawa and Salina are exploring it from an environmental angle. The societal problems are presented as both a cause and effect of this viewpoint.

While interrogating local socioeconomic inequality, like their artistic predecessors, they also consider the global factors at play in environmental issues. This new direction in artistic discourse on urbanisation in Indonesia places both works within the framework of green governmentality analysed by Kusno. Salina does so by engaging a medium and practice that encourages the inclusion of a wide range of participatory communities. Astawa does so by juxtaposing the local and international community against each other in Dewa Murka. This encourages the viewers to question their own role in Bali's cultural and environmental conditions.

Of the two artworks discussed here, 1001st Island is most reflective of the methods used in green governmentality. Salina's collaborative method parallels those employed by the state to engage urban citizens in green discourse. Much like the participatory methods of green governmentality, Salina has worked alongside NGOs and relevant communities. In comparison, Dewa Murka is primarily reflective of the narrative of green discourse. Astawa's painting inspires introspection on the contribution of the individual; it parallels the state's intention to place accountability for urban environmental degradation onto its citizens. Astawa also invites viewers to question what has been and what will be lost. He does so by drawing on the boundaries between the local population and the tourist, tradition and modernity, and therefore the tensions between local and global forces. Salina shows us what has already been lost and who is affected. In the version created in Indonesia, 1001st Island focuses on socioeconomic inequality. Both works differ widely despite a single point of departure — land reclamation. The different mediums and methods used by these artists to interrogate land reclamation have shaped their questions and the scope of their observations. In effect, they bring to the foreground the breadth of positions and concerns communities face when grappling with the consequences of land reclamation.

Ultimately, both these works speak to changing concerns within Indonesian urban green discourse: Salina's 1001st Island is strongly reflective of the methods used in green governmentality; Astawa's Dewa Murka, on the other hand, is less in line with the practical methods but still reflective of the state's narrative promoting civic duty. Parallels exist in the language and legibility of climate change in the text–image relationship. The disparity with green governmentality's methods might relate to the Java-centric nature of the discourse. As mentioned, Nusa Benoa is marketed in a manner that is reflective of ‘clean and green’. Nevertheless, as a tourist hub, there is a distance between the project and Bali's citizens. Promoting a sense of responsibility and belonging is challenging, and this is apparent in Dewa Murka.

For further research, it would be interesting to investigate the scale of this discourse across Indonesia and how questions explored by these artists — concerning land reclamation — might differ from those of regional artists responding to the same type of projects, such as Charles Lim's Sea State, Debbie Ding's Soil Works and Nicola Anthony's Reclamation.Footnote 100 In Indonesia, two artists to consider include Arahmaiani and I Made Bayak. Bayak's artistic practice is heavily influenced by the capitalisation of Balinese land. Notably, in 2014, at an event organised by Tolak Reklamasi in Benoa, he presented a performance piece where he stood upright meditating as a large excavator gradually released numerous loads of soil above his head until he was buried under an artificial mound.Footnote 101 Arahmaini's re-enactment of her ongoing Flag Project series in Bali in 2019 evokes ideas of protest concerning local environmental issues.Footnote 102 The flags are embroidered with words such as ‘culture’, ‘earth’, ‘capital’, ‘respect’ and ‘solidarity’. Initiated following the 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta, Arahmaini's Flag Project is rooted in initiating discourse in order to empower and rebuild communities following environmental tragedy.