1. INTRODUCTION

Environmental public interest litigation (EPIL) by non-governmental organizations (NGOs)Footnote 1 emerged in China over the last decade amidst the growing focus on environmental issues and the increasing political need for greater public participation in the area. EPIL represents the standard avenue for the public to resolve environmental disputes, supervise environmental quality, and enforce government policy.Footnote 2 Through this approach, the public is included in environmental governance to address environmental problems. By accessing environmental information, often as a precursor to environmental litigation, members of the public can defend their individual and collective self-interests, and are able to supervise government policy processes as well as the performance of industrial polluters. Similarly, NGOs often resort to litigation as a strategy to affect government policies and actions in a context in which opportunities of resistance are otherwise limited.Footnote 3

Since 2015, a number of environmental NGOs have worked to bring dozens of EPIL cases each year and these NGOs have become an integral part of the ongoing structure of China's environmental governance. As EPIL appears to have empowered NGOs to exercise some supervisory functions over issues that concern public interests,Footnote 4 there have been strong voices, from China and abroad, advocating widening access to EPIL for individual citizens.Footnote 5 From a comparative perspective, environmental litigation is an essential component of environmental law, which represents increasing demand from citizens for decentralized environmental governance.Footnote 6 There is valuable experience in environmental governance to be learned from jurisdictions with a more established litigation practice, including, for instance, the Unites States and the European Union,Footnote 7 as well as India,Footnote 8 and Brazil.Footnote 9 Such practices illustrate how, by adopting formal means, citizens may become empowered to influence environmental policies and improve environmental conditions.Footnote 10 They also raise the hope that ‘citizen suits’ could begin to play a stronger role in China's environmental governance.Footnote 11 Nevertheless, it is important to examine the effects of environmental litigation by contextualizing the social and political conditions of such citizen suits. Compared with environmental litigation in developed countries which have seen success to a greater or lesser extent, such practices within emerging powers still raise questions. While most literature focuses on assessing the legal institutions that pave the way for transparency in policy processes,Footnote 12 few have focused on the conditions under which civil society will efficiently serve public interests in environmental litigation practices.Footnote 13 One such rare example relates to discussions in the context of water management in India. Despite the fact that environmental activists have proactively adopted environmental litigation as an approach to advocate their causes,Footnote 14 heated debates have occurred examining whether such legal practices have weakened the authority of central government and thus have resulted in questionable environmental decisions.Footnote 15

Questions can be raised on how free NGOs are to participate in environmental enforcement through litigation in China. The involvement of NGOs in such litigation requires them to be financially sustainable. However, as NGOs are affected by strict government registration and fundraising regulations,Footnote 16 they are generally ill-prepared to become involved in EPIL. Furthermore, they are constrained by the principles and practice of the Chinese judicial system in which local courts, explicitly under the leadership of the Communist Party, are largely embedded within, and often dependent on, local governments.Footnote 17 When participating in EPIL cases, NGOs have to be very careful about the battlegrounds they choose. Some argue that NGOs should play a supportive rather than a confrontational role in environmental regulation.Footnote 18

Although an increasing body of scholarship has developed which examines the features and policy construction of EPIL in China,Footnote 19 few have questioned the practice of NGOs in the field of EPIL by analyzing their behaviour, approach or risk perception when participating in lawful environmental enforcement. This article assesses the current practice of EPIL by NGOs, and exposes a number of flaws and deficiencies in their participation in this relatively new field of environmental litigation.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 explores the government's intentions in promoting public involvement in environmental governance. Section 3 then sets out the legal framework of three types of environmental enforcement: (i) EPIL by NGOs; (ii) EPIL by the procuratorate; and (iii) ecological environmental damage compensation (EEDC) lawsuits by local governments. Section 4 of the article analyzes the data relating to EPIL cases available between 2015 and 2018, and goes on to evaluate EPIL by NGOs, focusing in particular on its role after the introduction of EPIL by the procuratorate and EEDC cases. Section 5 investigates the current practice of EPIL by NGOs through an examination of five EPIL cases. This critical examination exposes certain flaws, deficiencies, and causes for concern or criticism regarding the current practices of NGOs. Section 6 concludes by evaluating the current role of EPIL by NGOs and related issues within the constantly evolving landscape of environmental governance and litigation in China.

2. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AND EPIL BY NGOs

China has witnessed dramatic changes in its environmental governance in the past three decades. Along with signing the Rio DeclarationFootnote 20 and promoting the principle of sustainable development, the Chinese government has promulgated China's Agenda 21,Footnote 21 which recognizes the core principles of the Rio Declaration.Footnote 22 In addition to policy learning through China's increasing involvement in global environmental governance, the Chinese government has initiated policy reforms to promote governability with the involvement of multiple actors, enhanced information disclosure and transparency.Footnote 23 Although state agencies remain the most important actors and environmental regulation continues to rely strongly on command-and-control, they are no longer the sole actors and approaches available.Footnote 24 A market-based regulatory approach has also been established, which introduces economic incentives for market actors.Footnote 25 The public is also increasingly involved in the policy process, as discussed further below. Nevertheless, the government has been slow to implement policy reforms and substantive legal change has been slow to materialize.

2.1. Public Participation in China

The Chinese government has offered various justifications for engaging the public through policy change. Generally speaking, to a degree the practices of enhanced public participation resemble practices of decentralized governance as a global trend which features the involvement of multiple non-state actors. Indeed, the central government has shown a preference for promoting public participation for the benefits it may bring in better policy implementation. Faced with serious environmental challenges, policymakers believe that effective public engagement is beneficial because it may facilitate public acceptance of policy decisions. It also allows inputs from experts, contributes to improved compliance and supports policy implementation.Footnote 26

Chinese authorities also have had to react to a growing demand for deliberative democracy, which resonates in environmental activism. In the face of environmental activism and organized collective action, authorities are careful to try to maintain social control and control triggers to social instability. Challenges to China's political authority from environmental activism have developed rapidly. In the first quarter of 2017 alone, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) received 88,000 complaints through a citizens’ hotline. More than a half of these cases related to air pollution; the rest related to water pollution and pollution by noise and solid waste.Footnote 27

Additionally, there is a growing public demand for transparency and participation in environmental policymaking.Footnote 28 Unhappy about environmental crises such as air and water pollution, Chinese citizens, mostly from middle-class and urban backgrounds, increasingly voice their dissatisfaction. Such activism takes diverse forms, including membership of environmental NGOs (both legal and illegal) and participation in social movements, court cases, and protests, especially in relation to environmental issues that might have an immediate impact on the daily lives of the protesters.Footnote 29 These developments have persuaded the government to accommodate public participation, at least to some extent,Footnote 30 to incorporate the public in policy processes.Footnote 31 The Chinese government sees an instrumental use for public engagement – namely, strengthening party legitimacy and enhancing its political control over the regime.Footnote 32

2.2. China's Environmental Laws and Public Participation

The Chinese central government has effected substantive reforms in its environmental legal system to encourage public participation in environmental governance.Footnote 33 Most notably, the Environmental Protection Law (EPL) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) underwent major revision and expansion in 2014.Footnote 34 It declares that individual citizens are ‘entitled’ to environmental information.Footnote 35 Other enactments, such as the Law of the People's Republic of China on Appraising of Environmental ImpactsFootnote 36 and the Regulation on Environmental Impact Assessment of Planning,Footnote 37 require the public to be engaged in public consultations, while ‘empowering’ citizens to supervise environmental quality and ‘enforce’ government policy by having access to such information.

Some scholars believe that these changes improve interactions between the people and the legislature and facilitate the incorporation of public opinions into law.Footnote 38 Even before the 2014 revision of the EPL, for instance, NGOs and scientists were invited to put forward their views via open discussion in the public sphere regarding the proposed amendments to the EPL, marking the first time that state authorities openly debated with the public the revision of a national law.Footnote 39 Further, the revised EPL requires full environmental impact appraisal (EIA) reports to be made available to the public (rather than simply a summary, as used to be the practice) and that these reports must include a chapter on how the public participated in the EIA process.Footnote 40 This law also requires the government to adopt various forms of engagement when including the public in policymaking.Footnote 41 Public consultations have also been adopted in budget deliberations,Footnote 42 whereby participants have a better chance of seeing their opinions incorporated in the policymaking process.

Some commentators suggest that the decision to grant NGOs access to EPIL is an experiment by the central government,Footnote 43 targeted especially at localities that suffer from weak enforcement or non-enforcement of environmental regulations.Footnote 44 Leaders at the local level may implement environmental policy strategically,Footnote 45 and local governments may favour industries from the same region, including polluters, who contribute to local revenue. From this vantage point the EPIL system challenges the autonomy of local governments in environmental governance. Public mistrust may exist at the grassroots level if local governments have restricted the activities of environmental NGOs, particularly when such NGOs are perceived to pose a threat to the interests of the local government. Informal communication arrangements between the government and non-state actors – including NGOs,Footnote 46 experts, and technocratsFootnote 47 – are an alternative means whereby the public is involved in the policymaking process.

3. THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF ENVIRONMENTAL LITIGATION

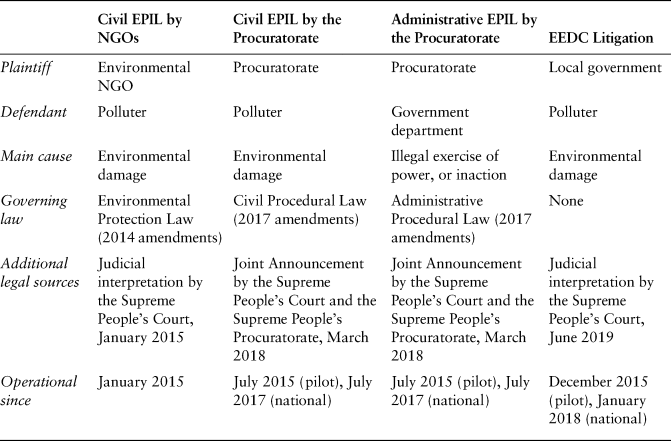

There are three categories of environmental litigation in Chinese law: (i) civil EPIL by NGOs; (ii) civil and administrative EPIL by the procuratorate; and (iii) EEDC (see Table 1). The legal framework for these categories is outlined in the three sections below. Understandably, there are some overlaps, synergies, and even conflicts in this new area of law. Additionally, but beyond the scope of this article, parties who have suffered directly from acts of pollution or environmental damage have the right to sue the perpetrators under the general law of tort.

Table 1 Different Types of Environmental Litigation

3.1. Civil EPIL by NGOs

The 2012 amendments to the Civil Procedural Law of the People's Republic of ChinaFootnote 48 first introduced the concept of public interest litigation to national law, stating that authorities and ‘relevant organizations’ as specified by law may litigate against activities that harm the social public interest, such as pollution of the environment.Footnote 49 The specification of ‘relevant organizations’ for environmental litigation purposes was introduced in April 2014 in the aforementioned amendments to the EPL.Footnote 50 To be eligible, a ‘social organization’, or environmental NGO, must be registered with the civil affairs authorities of a city at prefecture level or above, in accordance with the law. Additionally, it may litigate against activities that cause environmental pollution or ecological damage only if it has engaged in public interest activities in relation to environmental protection continuously for five years or more without any law breaking.Footnote 51 In January 2015, the Supreme People's Court issued its judicial interpretation, setting out the practical and procedural rules for ‘social organizations’ to bring EPIL actions.Footnote 52

3.2. Civil and Administrative EPIL by the Procuratorate

In July 2015, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress authorized the Supreme People's Procuratorate to start a two-year pilot run of procuratorial public interest litigation in 13 regions at province level. The decision was motivated by the need ‘to strengthen the protection of national interest and social public interest’.Footnote 53 Both the Supreme People's Procuratorate and the Supreme People's Court then issued Implementation Measures for procuratorial public interest litigation in JanuaryFootnote 54 and February 2016,Footnote 55 respectively. These measures provided that the procuratorate at any level within the pilot regions could bring either civil or administrative public interest litigation.

Civil public interest litigation concerns activities that harm the social public interest in areas such as environmental pollution, and food or medicine safety infringements that affect a large number of consumers. Administrative public interest litigation concerns the illegal exercise of power or inaction by governmental departments that harm the national interest or social public interest, including in the realm of ecological and environmental protection.

Following the pilot run, the terms of the Implementation Measures were adopted in June 2017 after some minor tweaks in the form of amendments to both the Civil Procedural Law of the PRC and the Administrative Procedural Law of the PRC.Footnote 56 The involvement of procuratorates in public interest litigation was a monumental shift in policy and practice, as it quickly mobilized the vast resources available to more than 3,600 procuratorates in China. Prosecutors outside the pilot regions wasted no time in taking advantage of this new power, and thousands of public interest litigation actions have been initiated by the procuratorate (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Number of EPIL Cases by the Procuratorate and NGOs

3.3. Ecological Environmental Damage Compensation Litigation

The latest entrant into the fray of environmental litigation comes in the form of EEDC. In December 2015, the General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council jointly issued a pilot reform plan for a new system of EEDC to be tested in seven province-level regions between 2015 and 2017.Footnote 57 The system was consolidated and expanded for national implementation in December 2017 by a full Reform Plan from the same two General Offices, effective from 1 January 2018.Footnote 58 In June 2019, the Supreme People's Court issued ‘Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Trial of Ecological Environment Damage Compensation Cases (Trial)’, marking the continuing development of the EEDC system.

EEDC cases can be brought only by governments at province or prefecture level and their designated department, and not by governments at county level.Footnote 59 After events such as sudden major environmental incidents, pollution or damage to ecology, EEDC litigation is available only if the government cannot agree on damages or remedies after negotiation with the person or entity causing the damage, or if no negotiation was able to take place.Footnote 60

Although the EEDC system has been in place for between two to four years in various parts of China, it has been based so far on policy documents and judicial interpretation and is yet to be formally enshrined in any law or regulations. The pilot plan and the full plan of the Communist Party and the State Council made no mention of any specific piece of legislation that would give effect to the new system. Given the weight of political authority that a joint plan from the Communist Party and the State Council carries, there is no reason to doubt that EEDC will become law sooner or later.Footnote 61 In any event, the lack of formal legal basis has not prevented the Supreme People's Court from reaching a decision in the majority of cases brought by local governments.Footnote 62

4. EXAMINATION OF EPIL CASES BY NGOs

From 2015 to 2018, between 53 and 68 EPIL cases were initiated by NGOs each year, with a slight increase in number overall. Although the procuratorate system of EPIL started almost a year after the NGO system of EPIL, the number of procuratorial cases very quickly dwarfed those initiated by NGOs, especially after the pilot run ended and national implementation started (see Table 2 and Figure 1). Nevertheless, a closer examination of the number indicates that the vast majority of procuratorial EPIL cases are either administrative EPIL or civil EPIL attached to criminal prosecutions.Footnote 63 In 2018, out of the 1,737 procuratorial EPIL cases, 376 (21.7%) were administrative EPIL, while 1,248 (71.8%) were civil EPIL cases attached to criminal prosecutions. Only 113 (6.5%) were civil EPIL cases unrelated to criminal proceedings.Footnote 64

Table 2 Number of EPIL Cases by the Procuratorate and NGOsa

Notes

a There are some relatively minor discrepancies among the statistics from different sources.

b Li, n. 71 below, p. 1.

c Ibid., pp. 311, 316.

d Supreme People's Court, Press Conference, 7 Mar. 2017, news report available in Chinese at: https://www.chinacourt.org/article/detail/2017/03/id/2573898.shtml. Li, n. 71 below, pp. 311–25, would indicate that the number could be as high as 140.

e Supreme People's Court, Press Conference, 2 Mar. 2019, n. 64 above.

Administrative EPIL is beyond the remit of NGOs. Although nothing in the law prevents NGOs from initiating any civil EPIL, it is arguably inconvenient or inefficient for NGOs to start civil EPIL if the claim could be attached to ongoing criminal proceedings by the procuratorate. In any case, NGOs still brought more than a third of the civil EPIL cases independent of criminal prosecution (65 out of 178, or 36.5%) in 2018. A much smaller number of EEDC cases were handled by the courts during the same period, with a cumulative total of 20 by the end of 2018.Footnote 65

Within civil EPIL the procuratorate should play a complementary role to that of NGOs, at least in theory. According to the Civil Procedural Law of the PRC, the procuratorate may bring public interest litigation only if no suitable governmental department or NGO is able to litigate, or if such department or organization refuses to litigate.Footnote 66 In practice, the procuratorate is far more active through the use of a pre-litigation procedure, which serves to identify and encourage qualifying NGOs to come forward and bring civil EPIL.Footnote 67 Moreover, the procuratorate can offer further assistance in civil EPIL brought by NGOs, such as helping with the collection of evidence or sending prosecutors to the court hearing to support the NGOs.Footnote 68 The latest report from the Supreme People's Procuratorate in October 2019 calculated that assistance was provided in 87 EPIL cases by NGOs,Footnote 69 which accounts for more than a quarter of all such cases.Footnote 70

Intriguingly, the enthusiasm of NGOs to bring EPIL seems to be significantly and positively influenced by the presence of procuratorial involvement. Under the pilot run in 2016, procuratorates in only 13 out of 31 province-level regions in Mainland China (excluding the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau) could initiate EPIL. NGOs have had no such restriction since January 2015, and could bring EPIL anywhere. Nevertheless, of the 68 EPIL cases brought by NGOs in 2016, only 18 came from outside the pilot-run regions.Footnote 71 In other words, 73.5% of the EPIL cases by NGOs were concentrated in 41.9% of the regions where the procuratorates could already bring such actions. While each of the 13 province-level regions included in the pilot run had at least one EPIL case by NGOs in 2016, 10 out of the 18 regions outside the pilot run did not see a single case, including both highly developed regions such as the municipalities of Shanghai and Tianjin, as well as large, less prosperous inland provinces such as Sichuan and Jiangxi.

This unusual concentration of cases where NGOs choose to be involved could be explained partly by the small number of qualified and interested NGOs. Although more than one thousand registered ‘social organizations’ are potentially able to bring EPIL, fewer than 20 of these come forward each year.Footnote 72 Unsurprisingly, regionally based environmental NGOs tend to launch EPIL with a clear regional focus. EPIL is more likely to materialize where more regionally based NGOs are involved in places where there is a procuratorate under the pilot run.

However, a large number of EPIL cases in practice are brought by nationally based environmental NGOs, most noticeably the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation (CBCGDF), Friends of Nature (FON), and the All-China Environment Federation. Although these organizations are registered in one region, which happens to be Beijing for all three, they operate nationally and initiate EPIL well outside their place of registration. Interestingly, even these organizations prefer to litigate in certain regions and not others, especially in view of the fact that before June 2017 many of the regions disfavoured by NGOs had no help from the procuratorate. The existence of such apparent regional preference will be revisited in the case analysis.Footnote 73

Meanwhile, although EEDC cases remain relatively few in number, their emergence could push EPIL by NGOs into an uncomfortable and further weakened position. EPIL by NGOs takes precedence over EPIL by the procuratorate, as the latter should proceed only if there is no NGO available to litigate.Footnote 74 Since June 2019, however, EEDC cases by local governments have trumped EPIL by NGOs, as the court must suspend the EPIL trial until after completion of the EEDC trial. EPIL is able only to cover issues not already dealt with in the EEDC case.Footnote 75

Similar to other rules and practice surrounding the EEDC structure currently under development, this priority rule at present is not affirmed by any law or regulation. Nevertheless, this status shift for NGOs, from being the preferred litigant in EPIL to the deferred party after the EEDC case, is a potentially crucial development. In effect, a local government may now supersede any ongoing EPIL by initiating EEDC proceedings, thus causing much delay and uncertainty for the NGO in the original EPIL. It is possible that the maturing of the EEDC system will further complicate the tasks for NGOs contemplating EPIL as they are now required to negotiate between the judicial and administrative powers even more carefully than was the case a few years ago. Such an imminent challenge is not easy for NGOs to deal with, especially at the current stage of the development of EPIL which, as we argue in the next section, already displays some notable deficiencies and flaws affecting EPIL by NGOs.

5. CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF EPIL PRACTICE BY NGOs

5.1. The Objectives and Choices of EPIL by NGOs

Although EPIL and EEDC are new labels which have emerged during the past few years, governmental or administrative involvement in major environmental incidents is certainly neither novel nor unusual. However, NGOs have struggled at times to coordinate their involvement, including in litigation, in the fast-evolving developments following major environmental crises. First and foremost, NGOs have often chosen to litigate over incidents in which the administrative powers have taken effective control of the situation, including the implementation of remedial work and the imposition of financial sanctions on the wrongdoers. In these cases, NGOs arriving later at the scene often struggle to establish either new evidence about what has happened or demand interventions additional to those already imposed by the administrative powers. This, in turn, obscures the objectives of pursuing such litigation and raises the question as to the choice made by these NGOs.

The Tengger Desert case

Media reports emerged in September 2014 about serious water and soil contamination of parts of the Tengger Desert in Inner Mongolia and Ningxia.Footnote 76 For years, various industrial operations had been disposing of hazardous elements into the environment without due processing, in a blatant breach of domestic law and regulation. The overt accumulation of serious pollution was depicted vividly in graphic material and video reporting by the national media, leading to a public outcry at a time when environmental concern was high on the list of national concerns. Authorities ranging from the State Council to the MEE took swift action in the following months and most of the clean-up and restoration work was successfully implemented by September 2015.Footnote 77

Meanwhile, the CBCGDF lodged an EPIL action in the local court in August 2015. The lawsuit was rejected by the Zhongwei Intermediate People's Court and the appeal by the CBCGDF against this rejection was again dismissed by the High People's Court of the Ningxia Autonomous Region.Footnote 78 The main reason given by both courts in rejecting the claim was that the CBCGDF charter did not specifically provide that ‘protection of the environment’ was part of its operation,Footnote 79 which disqualified the organization from pursuing EPIL.Footnote 80

The CBCGDF applied to the Supreme People's Court for a retrial in January 2016. The retrial was granted and then completed in a matter of one week, with the final judgment of the Supreme People's Court in favour of the CBCGDF, directing the local court to accept the EPIL. The Supreme People's Court pointed to various stated objectives in the charter of the CBCGDF – ranging from ‘supporting biodiversity and green development’ to ‘promoting the establishment of an ecological civilization and the harmony between human kind and nature’ – and concluded that the scope and aim of the CBCGDF did encapsulate ‘protection of the environment’, notwithstanding the absence of explicit wording to that effect.Footnote 81 The retrial judgment was later selected to be a ‘guiding case’ by the Supreme People's Court, further endorsing its authority and merit.Footnote 82

The Zhongwei Intermediate People's Court promptly accepted the EPIL launched by the CBCGDF in early 2016 against the eight defendant companies responsible for serious pollution of the Tengger Desert. Yet, this development was overtaken by events that were unfolding outside the court system, as the pollution incident had been addressed largely by the administrative authorities several months earlier. As later court documents showed, the defendants were held financially liable for a total sum of 569 million renminbi (RMB 569 million) in various fines and expenses for remedial work and environmental restoration.Footnote 83 By 2016 the remedial and restoration work either had been implemented or was in the process of being implemented under governmental supervision. Despite the CBCGDF obtaining judicial endorsement from the Supreme People's Court to proceed with the lawsuit, it was unclear what this particular EPIL could achieve.

After more than a year the CBCGDF settled with each of the eight defendant companies. The NGO was said to be ‘satisfied’ with the proof provided by the companies that work had been or was being carried out to remedy the environmental damage. Each company ‘voluntarily’ contributed a sum to be used for ‘repairing the service function of the local environment’, totalling around RMB 6 million.Footnote 84 The CBCGDF also recovered RMB 1.28 million in costs from the settlement.

It is appropriate that companies or individuals who wilfully and recklessly pollute the environment in the pursuit of higher profit margins are hit with significant financial and other sanctions, both for remedying the damage they have caused and as a deterrent for future entities contemplating such behaviour.Footnote 85 The perpetrators of the Tengger Desert pollution were made to pay RMB 569 million, and a number of their managers and executives were given prison sentences in separate criminal proceedings. There was no indication that the amount of RMB 569 million was inadequate for the purposes of penalizing the perpetrators and restoring the environment, as far as money and modern science would allow. By the time the CBCGDF attempted to initiate EPIL, and certainly by the time it was given the green light from the Supreme People's Court in 2016, the administrative process to deal with this major incident was in full motion and producing outcomes. It is unclear what was to be gained by the EPIL despite the eventual RMB 6 million settlement, as there was no sign that this ‘voluntary contribution’ accounted for anything that the original sum of RMB 569 million failed to cover.

The Hyundai Motors case

There are other examples of EPIL being pursued with unclear objectives. Hyundai Motors was found to be selling a specific type of vehicle between March 2013 and January 2014 which failed to meet Beijing emissions standards on the ground of defective fuel injectors.Footnote 86 Hyundai promptly moved to remedy the defect in these vehicles and, by June 2014, its remedial actions had been approved by the authorities. In September 2014, the Beijing Bureau of Environmental Protection imposed administrative sanctions in accordance with the law and regulations and confiscated ‘unlawful income’ in the sum of RMB 13.5 million. It also imposed a 10% penalty of RMB 1.35 million.Footnote 87

Yet, in May 2016, more than 18 months later, the FON decided to initiate EPIL in respect of the incident, demanding that Hyundai be ordered to stop selling the vehicles concerned and pay an unspecified sum of compensation ‘to be determined by experts’ for the damage to the atmosphere caused by the polluting cars. Hyundai responded that it had not sold any cars in violation of the regulation for more than two years, and that the claim was therefore groundless. After almost three years, the parties settled in May 2019, with Hyundai voluntarily contributing RMB 1.2 million towards ‘protecting and repairing the atmosphere, preventing air pollution and supporting environmental public interest activities’, in addition to RMB 200,000 to the FON to cover costs incurred in the litigation.

Similar to the settlement in the Tengger Desert cases above, there was no indication that the original sanction of almost RMB 15 million imposed by the government was inadequate, or that the EPIL by the FON established any new facts that were unknown in 2014. With no knowledge of Hyundai's decision-making process, it may nevertheless be speculated that RMB 1.4 million of voluntary contribution, mostly in the name of protecting the environment, was a modest price to pay for a multinational carmaker to terminate a long-standing dispute with a major environmental NGO. For the FON, on the other hand, RMB 200,000 could cover much of its litigation costs, so that the EPIL potentially did not result in significant financial loss.

It is notable that in both the Tengger Desert and the Hyundai Motor cases the NGO concerned chose to take action following a high-profile incident or against a high-profile defendant, even where administrative authorities had seized clear and effective control of the situation many months before the EPIL was initiated. The litigation did not uncover any additional liability or legal responsibility that had been overlooked in the consideration of administrative measures and sanctions. It is therefore hardly unexpected that no court judgment against any of the defendants was forthcoming and the cases resulted in settlement after several years with some voluntary contribution and reimbursement of costs by the defendants.

In most cases, administrative measures in the wake of major environmental incidents do, and should, take effect far more quickly than any court judgment. If the objective of the NGOs was to oversee policy implementation, EPIL brought by NGOs should arguably focus on identifying what the ‘fire-fighting’ administrative measures have not covered or have missed, rather than focusing on what has already been addressed under the scrutiny of national media.

5.2. Litigation Costs and Risk Perception of NGOs in EPIL

On several occasions the decisions by NGOs as to which form of EPIL to pursue and how to approach litigation reveal a potentially skewed perception of the costs and risks of EPIL, as illustrated in the cases below.

The ‘Poisonous Land’ of Changzhou

In September 2015, a secondary school in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, moved to its newly built campus. Over the following months many pupils started to display symptoms such as nausea, skin irritation, and hair loss. The ensuing investigation identified the cause as soil pollution of a plot of land about 200 metres from the campus. Although the land was not in use at that time, it had been the site of several chemical and pesticide factories between the late 1960s and the early 2000s. The incident was reported on national television in April 2016 as ‘the poisonous land of Changzhou’, and caused wide-ranging concern among the public.Footnote 88

The FON and the CBCGDF, two major environmental protection organizations, joined forces to initiate EPIL in May 2016. They identified three defendant companies as responsible for the pollution and demanded compensation for damage to the environment, a public apology, and the reimbursement of costs incurred by the NGOs.

The case, however, was complicated by several factors. The three companies, one of which is a large state-owned enterprise of Changzhou, had moved away from the relevant site many years before the exposure and the lawsuit. More importantly, in 2008 the plot of land had already been recovered by the local government for redevelopment, which included ongoing efforts to remedy the known historical pollution. Although at the time of their activities the companies acted in a way that would be considered blatantly harmful to the environment by modern standards, it was less straightforward to establish the illegality of some of those activities retrospectively.

Consequently, the two NGOs lost at first instance. The court acknowledged the obvious public interest in bringing the lawsuit, but found that the defendants were not in a position to implement any remedial steps, given that they no longer had control of the land. The claim also failed to establish the exact responsibilities of the defendants, given the highly complicated history of privatization of state-owned enterprises and various corporate restructurings over many years.Footnote 89

The decision caused shockwaves, not only because this was a high-profile loss for two major NGOs, but also because of how the court fees were calculated. On the basis of the monetary claim of RMB 377.3 million as compensation for the environmental damage, the court applied its standard fees of about 0.5% and arrived at a figure of RMB 1.89 million in court fees. If the FON and the CBCGDF had to shoulder the sum between them, this would have been a heavy financial burden for even large and nationally established NGOs to bear.

Fortunately for the two NGOs, their appeal was partially upheld by the High People's Court of Jiangsu Province. The Court held that the difficulty in apportioning liability to each defendant could be overcome if it exercised its judgment as to what was reasonable. Although not everything the defendant companies had done in the past was necessarily illegal at the time, they were held responsible for the continuing harmful contamination of the land and ordered to apologize to the public.

However, for several years after the companies had ceased their operations the land had been retained by the local government, which was already making efforts to remedy any remaining problems. The fact that land pollution was a historical issue made it difficult for the Court to decide on present financial liabilities. It rejected the suggestion put forward by the FON and CBCGDF to award compensation as some recognition of the costs of the remedial work undertaken by the local government over the land because the local government was not a party to the EPIL. There was no feasible way to calculate, or even to estimate, the appropriate monetary compensation for any lasting damage to the environment after ongoing restoration efforts by the local government.

On the controversial issue of court fees, the appeal court held that as there was no basis for assessing monetary compensation, the case should be treated as a non-monetary lawsuit, with the court fees at first instance and on appeal of RMB 100 each borne by the three defendant companies.Footnote 90 In essence, the NGOs won on principle and did not have to pay the RMB 1.89 million court fees; the companies lost and had to apologize, but did not have to pay hundreds of millions in compensation. Following this final decision, the FON decided to drop the case; the CBCGDF applied to the Supreme People's Court for a retrial.Footnote 91

While the Supreme People's Court will re-examine the case, the first-instance imposition of RMB 1.89 million in court fees was a timely reminder to NGOs of the risks of litigation. Given the growing support for environmental protection in society in general, there is arguably the unspoken assumption, held by both the public and those involved, that EPIL is a rightful action brought in the public interest by well-intentioned NGOs against irresponsible perpetrators who harm the environment. The losing party pays the court fees, so it should be the polluters who pay. They should also pay for the reasonable costs incurred by the claimants, including attorneys’ fees and other items of expenditure.Footnote 92 Against this background, it is largely understandable that lawyers in court proceedings ask for sensational figures of hundreds of millions of RMB.

As cases such as the ‘poisonous land of Changzhou’ case reminded claimants of the prospect of losing and having to bear very substantial court fees, many calls have been made for the fees to be set at a low, flat rate, such as RMB 50 per case, independent of the monetary value of the case.Footnote 93 The main argument for such special treatment is the public-interest nature of EPIL, as well as the fact that NGOs are not litigating for their own financial gain.

Some of the claims by NGOs, especially in relation to their attorneys’ fees and litigation costs, do not naturally support the argument for treating EPIL as special, non-monetary litigation. As things stand, the rules heavily favour NGOs in EPIL, with the court having the option of asking defendants to bear the reasonable costs of NGOs, while there is no corresponding possibility for defendants’ costs to fall on NGOs even if the claim fails. Moreover, the court can allow deferment, discount, or even waive the court fees payable by NGOs.Footnote 94 Even so, there have been multiple instances where NGOs have claimed much higher costs and attorneys’ fees than the court is prepared to award.

In the ‘poisonous land of Changzhou’ case, the two NGOs claimed costs of RMB 1.45 million between them. The Court was clearly unimpressed by the scale of these claims and awarded RMB 230,000 to each NGO, or less than a third. However, in the application to the Supreme People's Court for a retrial, the CBCGDF is again claiming not only the full costs but is also asking for the court fees to be restored to RMB 1.89 million each at first instance and on appeal, to be borne by the defendant companies, instead of RMB 100 each as set by the High People's Court.Footnote 95 It seems to be a remarkable display of confidence for any litigant to ask for court fees to be increased by almost 20,000 times the amount that the court was prepared to charge, and it suggests that any implicit message from the appellate court expressing its discontent at the high costs being claimed has been lost.

The ‘poisonous land of Changzhou’ saga is not an isolated example of judicial discomfort with the costs claimed by NGOs in EPIL. In a case about waste disposal from Shandong Province, the CBCGDF claimed RMB 300,000 in attorneys’ fees plus further ‘contingency fees’ that were dependent on the outcome of the litigation. The Jinan Intermediate People's Court presumably did not like the notion of some litigation bonus and awarded RMB 100,000.Footnote 96 On occasions the court is stricter or more forthright about the level of fees. The lowest amount of attorneys’ fees awarded could be as little as 4% of the amount claimed by a victorious NGO.Footnote 97 In an appeal on wastewater discharge from Zhejiang Province, the High People's Court gave a succinct but stern lecture on how attorneys’ fees should be ‘only what is reasonable’. The CBCGDF had claimed RMB 688,700 in attorneys’ fees but the Court took issue with the notion that this figure was based purely on what the attorneys claimed to be entitled to, with no other verification of the actual number of hours worked or the amount of work undertaken. The final award was set at RMB 200,000.

Notably, the appeal in the latter case was an outright loss for the CBCGDF as the Court dismissed it on all grounds. Nevertheless, it exercised discretion in splitting the court fees of RMB 195,995 equally between the CBCGDF and the defendant company, while granting a discretionary discount of the CBCGDF's share only of the court fees from RMB 97,997.5 to RMB 1,000.Footnote 98

The willingness of the Court to waive 99% of the court fees that it could legitimately charge for an NGO which has just lost its appeal is indicative of the generally supportive attitude of the judiciary towards NGOs in EPIL. NGOs in some cases arguably demonstrate a cavalier attitude towards the risks and costs inherent in litigation, at least until the court decides against them. It is not impossible for an NGO to lose outright in the litigation, for example, by failing to establish that the activities under scrutiny were harmful to the environment, despite committing substantial sums towards forensic analysis.Footnote 99

In September 2017, an environmental NGO based in Chongqing made national news headlines by bringing EPIL against three major online food delivery platforms simultaneously, alleging that they had failed to provide environmentally friendly alternatives to disposable cutlery. Without waiting for court proceedings to commence, this NGO also revealed to the media that it was preparing next to sue both McDonald's and KFC at the same time.Footnote 100 The news report contained no information or discussion of how a local environmental NGO would be assembling the resources required to take on five of the biggest names in the food industry at the same time, and to bear the financial consequences should the litigation fail.

It is argued that any strategy to go after the big, headline-making incidents or global commercial names, perhaps in the expectation that the court will simply grant all costs in a win or at least mitigate all fees in a loss, is not convincing as a robust long-term plan for the development of EPIL. At the same time, the suggestion to charge only nominal court fees does not sit comfortably with the practice of some NGOs of claiming costs and attorneys’ fees at a level which multiple courts have found to be exorbitant.

5.3. Questionable Practices by Major NGOs in EPIL

Some of the practices adopted by major NGOs engaged in EPIL go beyond questions of institutional choice and arguably impact upon the foundation of justice. The following two cases raise concerns that major environmental NGOs may have brought the impartiality and neutrality of the judicial system into question, and obstructed adherence to strict jurisdictional boundaries within the legal system.

The forensic public interest fund

In December 2016, the China Environmental Protection Foundation (CEPF) brought an EPIL claim against a steel processing company in Tangshan, Hebei Province, regarding air pollution. This case was remarkable for being the first occasion on which EPIL made use of funding from a newly established China Environmental Protection Fund, which awarded RMB 100,000 to the case for the cost of forensic analysis relating to the environmental damage caused by the defendant company. According to the terms of the fund, any Chinese court may apply to it for a sum of money between RMB 60,000 and 120,000 to carry out necessary investigation in any civil EPIL.Footnote 101 However, this fund was established by none other than the CEPF, the claimant in this particular EPIL. The judges in the case actually had to complete an application form to apply to the CEPF for money in order to facilitate forensic studies in the litigation, before eventually directing a settlement between the parties in March 2019.

The rationale for this new fund, as explained on its website, refers to the difficulties experienced by ‘the majority of courts’ in securing financial support to carry out their investigative duties in EPIL, which the fund seeks to address.Footnote 102 Noble as the intention may be, the current operation of the fund means that, in cases such as this, the court receives money to carry out its judicial investigations, after actively having to apply for it, from one of the litigant parties, before reaching a hopefully just and unbiased decision. This patently affronts some of the basic tenets of natural justice and the rule of law, not least that the judge should remain neutral and impartial, and that justice must be seen to be done. It was inexplicable and arguably unacceptable that the CEPF did not excuse itself from even considering the application for money in relation to litigation in which it was actively participating. The awkwardness of this course of events apparently eluded many, as news of this settlement was covered by the national newspaper for the judiciary as a good example of judicial innovation.Footnote 103 Such a mode of funding practice where an NGO acts both as the funding source to support the work of the judiciary and an active litigant in the same EPIL, without taking any note of the obvious conflict of interest, is in clear need of fundamental rethinking.

The Shandong lorry cases

NGOs seem to display regional preferences when considering EPIL. In some cases, however, this arguably has gone much further to the extent of attempting to actively manipulate the jurisdiction of the court.

In February 2018, the FON brought two similar EPIL cases in Beijing No. 4 Intermediate People's Court against two lorry manufacturers based in Shandong Province, in relation to vehicle emissions beyond the legal threshold and consequential air pollution.Footnote 104 The lorries concerned were manufactured in Shandong and had never been sold in Beijing. The FON preferred the case to be heard in Beijing rather than Shandong and chose to sue a joint defendant in each case, both being retailers based in Beijing who had signed retail agreements with the manufacturers. It offered no explanation of its choice of forum or litigation strategy. Notably, the retail agreement between the manufacturers and retailers only came into effect several months after the manufacturers had stopped making and selling the lorries, which were found to be in violation of emissions regulations. The Court found that the Beijing-based defendants had no connection with the offending lorries; nor were these lorries ever sold in Beijing by any retailer as they never obtained the necessary permission for sale in the capital.

Alongside some incisive remarks about the potential harm of jurisdiction manipulation by claimants, the Court concluded explicitly that ‘the defendant is only added to this litigation by FON for the purpose of altering the jurisdictional court’. Both lawsuits were promptly dismissed and the FON was directed to bring them in Shandong instead.

The FON's strategy of seeking to alter the jurisdictional court is unexplained and is highly questionable. If it felt that the Beijing court would be more favourable to its claims, such a move would arguably run counter to the policy motives for EPIL, such as promoting transparency in environmental governance.Footnote 105 Without any evidence or argument to the contrary from the FON, it would seem that Shandong, and not Beijing, would have been most affected by any environmental damage caused by the lorries concerned. It was arguably inappropriate for a national environmental NGO such as the FON to attempt to manipulate the jurisdiction of the court in such a manner.

The Shandong case further illustrates the false sense of security displayed by some NGOs in bringing EPIL claims. For any law-abiding, environmentally conscious company, the prospect of being drawn into EPIL by a major NGO must be both daunting and frustrating. As things stand, judicial interpretation explicitly forbids counterclaims by a defendant in EPIL against the claimant NGO.Footnote 106 Furthermore, in suing businesses, NGOs are possibly motivated by the ‘indirect’ effects of EPIL, which are to raise environmental awareness among the public and put pressure on polluting companies to comply with environmental regulations.Footnote 107 Nevertheless, given the likely consequences of EPIL in terms of reputational damage, it is possible that defendants, especially those dragged into ill-conceived EPIL – such as the two Beijing-based retailers found by the Court to be completely unrelated to the defective lorries in question – may seek formal redress against claimant NGOs in the future, for example, through separate tort proceedings.

5.4. New Directions in EPIL by NGOs

Notwithstanding some of the more questionable practices presented above, there are some genuinely exciting efforts by NGOs in initiating EPIL cases, which have the potential to better define the scope and content of environmental protection. At the time of writing, several EPIL cases are going through legal proceedings, which have the potential to answer difficult questions such as whether governmental bodies could become liable in EPIL if they cause environmental damage, or whether state-owned monopoly utility companies could be liable in EPIL in the absence of a breach of regulation.

In September 2018, the CBCGDF brought an EPIL action against the Wildlife Rescue Centre of Guangxi Autonomous Region and its superior, the Forestry Authority of Guangxi, in relation to the death of armadillos. These armadillos were smuggled into China back in 2017, when they were discovered by law enforcement and handed over to the Wildlife Rescue Centre for quarantine. The CBCGDF alleged that after quarantine was completed the Wildlife Rescue Centre failed to follow the proper procedure of not releasing eight animals found to be ‘healthy but weak’, which eventually led to their death.Footnote 108 The case covers multiple issues of great interest, ranging from the applicability of public interest standards to specific tasks of animal quarantine, to the responsibility of governmental departments and their ancillary institutions. The case may well shed light on the previously raised questionFootnote 109 of whether civil EPIL can be brought against a government department or its subsidiary.

Moreover, in June 2019, the CBCGDF brought an EPIL claim against a number of defendant companies in Wuhan, Hubei Province, in relation to the death of 36 adult and 6,000 juvenile Chinese sturgeons, a critically endangered species. The CBCGDF alleged that the defendant companies carried out the construction of a bridge and roadworks without proper environmental assessment and that the constant noise from the construction work eventually caused the death of the fish.Footnote 110 This is likely to be the first time that noise has become the focus of EPIL as a new addition to the usual suspects of air, soil, and water pollution.

Beyond wildlife protection, some EPIL by NGOs ventures into uncertain territories in terms of the scope of environmental protection. After several years of efforts and two court hearings, the EPIL by the FON in respect of wind energy against the state-owned monopoly electricity network company of Gansu Province was accepted by the court.Footnote 111 The defendant company produces no electricity itself and only contracts with various producers of wind, solar, and fossil energy. The essence of the claim is that the defendant company chooses to restrict and cut back on the full capacity of wind energy from time to time because of constraints on energy capacity and the operation of its electricity infrastructure. This results in wind energy not being harvested to the maximum as required of an electricity network company by law,Footnote 112 which in turn leads to fossil energy being used in substitution. Such activities allegedly cause environmental damage, which could have been averted had the capacity of the electricity supply network been greater to accommodate those periodic excesses in wind energy.

It is notable that the defendant company does not directly cause environmental damage as it is not engaged in the actual production of electricity. With myriad political, legal, economic, and technological moot points to navigate, it may be several years before the dust settles on this ongoing lawsuit. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to see NGOs willing to test the boundaries and make efforts to expand beyond the EPIL comfort zone.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

EPIL represents the commitment of the Chinese central government to address environmental issues and the harm caused by environmental incidents, as well as the political drive to move important, especially monetary, decisions in the fallout of environmental incidents away from the government as policymakers and towards the courts as just arbitrators. The findings in this article indicate that EPIL by NGOs is now a reasonably established part of the legal enforcement mechanism in environmental protection.

Meanwhile, the role of EPIL by NGOs among competing mechanisms in the Chinese legal system is evolving. Although EPIL has empowered NGOs to exercise some supervisory functions over public interest issues, NGOs are restricted in their choice of pathways to participate in environmental governance. Our findings indicate that although state powers such as the courts and the procuratorate have been supportive overall in substantive ways, the contribution of EPIL by NGOs is nevertheless under pressure from competing mechanisms in the form of EPIL by the procuratorate and EEDC litigation. The latter, in particular, has the potential to undermine the justification for EPIL by NGOs as local governments are arguably in a better position to represent the public interest in the case of environmental damage to a local area. EEDC litigation has also been prioritized over EPIL in recent court rulings. Such inherent competition exists despite the overall support that the courts, the procuratorate, and the government have shown towards NGOs in initiating EPIL.

Furthermore, the involvement of Chinese NGOs in EPIL reveals some of the challenges of incorporating the public in environmental governance. Our findings indicate that, when practising EPIL, some NGOs seem almost oblivious to the inherent costs and risks of litigation. This may be explained by the organizational development and financial status of Chinese NGOs. Apart from restrictive registration policies,Footnote 113 NGOs are faced with pressure to mobilize funding to secure financial stability.Footnote 114 Compared with their counterparts in western liberal democratic societies, where some NGOs have become specialists in environmental litigation, Chinese NGOs have less legal knowledge and expertise.Footnote 115 It seems reasonable, therefore, to suggest that these NGOs would need to consider a different funding and sustainability model for EPIL as they are likely to incur significant costs, even in successful lawsuits.

Similarly, as EPIL has only been established during the last decade, very few NGOs have gained a high level of knowledge and expertise with regard to China's environmental governance.Footnote 116 Accordingly, their legal approaches represent mixed practices, which show a tendency to focus litigation efforts on sensational, major incidents that have received national media and public attention. Litigation is often pursued by NGOs despite prompt and significant administrative measures having already been taken to address the problem, while their perception of the costs and risks involved in litigation would appear to be questionable across different cases. It is submitted that the problems and concerns identified in relation to the practice of NGOs in initiating EPIL would need to be fully examined in any discussion of potentially expanding the scope of EPIL under Chinese law. Hence, China's experiences in environmental litigation differs from those found in liberal democracies, reminding us particularly of the challenges in adopting a legal approach to protect the environment in the context of Chinese culture and politics.Footnote 117

NGOs are evidently learning and experimenting in new areas, such as wildlife protection and energy production, by implementing EPIL as the most effective tool to engage formally with stakeholders such as government departments or major state-owned enterprises. Alongside developing a more balanced view of the opportunities and risks of EPIL, it can certainly be hoped that NGOs will take full advantage of the EPIL mechanism as an alternative approach to the more dominant procuratorial EPIL and the emerging EEDC lawsuit. With a better understanding of the system of EPIL, more reasoned decision making and more efficient use of its resources, NGOs can certainly play an important role in China's evolving environmental governance.