Introduction

As Pierre Courroux recently observed, medieval chroniclers made use of their sources in much the same way as the Church Fathers made use of pagan traditions — that is, “by adapting them to their aims.”Footnote 1 This article analyses, edits, and translates for the first time the result of one such adaptation, the Brevis cronica compendiosa ducum Normannie. Written at the turn of the fifteenth century by Simon de Plumetot (1371–1443), the Norman scholar and early humanist most famous for his collection of autographs, the Brevis cronica offers a succinct history of medieval Normandy and its dukes, from the duchy's pagan roots in modern-day Denmark to the invasion of Anglo-Saxon England by William the Conqueror in 1066. The text, to date, has attracted almost no scholarly attention, save for perfunctory mentions in various catalogues and descriptions of the manuscripts in which it is conserved. At first glance, such neglect would seem to be entirely in keeping with a work that, as the edition below makes clear, is as short as it is scrappy. Surviving thanks only to two early modern copies, the quality of which at times leaves a great deal to be desired, the Brevis cronica is written in a style that is perhaps best described as “draft-like” and sometimes cumbersome to read. It would also appear, prima facie, to be little more than a highly-truncated copy of two of the most celebrated — and also widely-diffused — histories of the Norman dukes and the duchy over which they ruled, namely Dudo of Saint-Quentin's Historia Normannorum and the Gesta Normannorum ducum by William of Jumièges.

Closer examination suggests a potentially far more interesting story, however, one that reveals the Brevis cronica to be a considerably more involved and important text than its rather unassuming form would suggest. Not only can we show that by “authoring” the Brevis cronica, Simon interacted with his sources in ways that went beyond that of a mere copyist, but also that he may have done so as part of a much larger historiographical project, namely an extended history of his native Normandy, written in the vernacular, the text of which is now lost. As a result, the Brevis cronica stands witness not only to this lost (vernacular) chronicle, but also to the working methods that underpinned its very creation. This, in turn, sheds new light on the career and historiographical activities of Simon de Plumetot, an important figure who has not always received the scholarly attention he deserves, as well as on a range of more general issues, from the use and transmission of key (Anglo-)Norman texts such as the Gesta Normannorum ducum to early humanist book collecting and the writing of history in later medieval France.Footnote 2 Moreover, by editing and publishing the text of the Brevis cronica in full, what follows makes the work readily available to scholars with an interest in the historiography of the Anglo-Norman world, as well as of medieval France more generally, while the accompanying translation makes the text accessible to students for the first time.

The manuscripts

In a reversal of editorial norms, it seems prudent to begin by examining the manuscript history of the Brevis cronica, without which its story cannot easily be explained. Today, the text survives in only two manuscripts, both written on paper, the first (and earlier) of which is Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, MS 1094, produced in the later fifteenth century (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 3 The second is Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 12882, made in the sixteenth century (Figures 3 and 4).Footnote 4 In addition, there was once a third copy (now lost) of the text predating both of the above in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 14663, a paper codex produced during the first quarter of the fifteenth century which, as will be seen below, provided the shared exemplar for the two extant copies of the Brevis cronica. Footnote 5 For ease of reference, the following manuscript sigla will be used throughout this study:

-

A† = Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 14663, fols. 42r–47v

-

B = Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, MS 1094, fols. 150r–153v

-

C = Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 12882, fols. 168r–176r

These three manuscripts have attracted varying levels of scholarly attention, most of which has focused on A†.Footnote 6 Likely the work of a single scribe and annotator working over the course of two and a half decades (see below), A† is a composite codex that combines a range of historiographical, annalistic, genealogical, and heraldic texts, from the early medieval histories of Einhard, Nithard, and Flodoard of Reims to the works of later medieval writers such as Guillaume de Nangis, Landulphus de Columna, and Raoul de Presles, to name but a few examples. Most of the texts contained in A† relate, in one way or another, to the history of medieval France and its various predecessor states (both historical and mythical), for example, by recounting the lives and deeds of celebrated rulers from Caesar, Clovis, and Charlemagne to Philip II Augustus, Louis IX, and Charles VI.Footnote 7 The book can thus be described as something of an “historical compendium” whose main sources were written, with a small number of exceptions, between the mid-ninth and late fourteenth centuries. Such historical compendia were no rarity at that time, both within Simon's own library (as will be seen below) and within France more generally, where “[i]n the second half of the fifteenth century, the past was the focus of unprecedented enthusiasm”.Footnote 8

Figure 1: Beginning of the Brevis cronica in Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, MS 1094, fol. 150r. © Gallica. Reproduced with permission of the BnF.

Figure 2: End of the Brevis cronica in Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, MS 1094, fol. 153v. © Gallica. Reproduced with permission of the BnF.

Figure 3: Beginning of the Brevis cronica in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 12882, fol. 168r. © Gallica. Reproduced with permission of the BnF.

Figure 4: End of the Brevis cronica in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 12882, fol. 176r. © Gallica. Reproduced with permission of the BnF.

Eight of the forty-six texts compiled in A† relate to, and for the most part originate in, the Norman and Angevin periods. In order of their occurrence in the manuscript,Footnote 9 these are: a history of the origins of the counts of Anjou extracted from the twelfth-century compilations of Ralph of Diceto (“De origine comitum Andegavensium”) (fols. 1r–10r);Footnote 10 a list (or catalogue) of Rouen's archbishops from Nicasius (ca. 250) to William de Vienne (1389–1406) (fol. 24r–v); William of Jumièges's Gesta Normannorum ducum (hereafter GND) according to Robert of Torigni's twelfth-century “F redaction” (fols. 68r–132r);Footnote 11 excerpts from Robert of Torigni's Chronica (fols. 130v–157v) and its thirteenth-century continuation (fols. 158r–168v), plus an anonymous compilation on Anglo-Norman history (“De cronicis Francie et Anglie ab anno Domini 1139 usque 1238”), the latter of which might be based on the monastic Annals of Jumièges (fols. 168v–175r);Footnote 12 and some anonymous additions concerning the history of the Anglo-Norman period (fol. 175r).

Codicologically, A† is made up of ten structurally distinct units (or “booklets”) produced between ca. 1400–1429.Footnote 13 Of the eight texts listed above, all but two occur in just two of these booklets. Matthias Tischler has dated one of them (fols. 52r–132v; “Part D”) to ca. 1402–1409 × 1414–16, probably written in Paris, and the other (fols. 133r–180v; “Part E”) to ca. 1400–1402, likely written in Rouen.Footnote 14 The two texts that occur outside of these booklets are the dynastic chronicle of Anjou, which constitutes a codicological unit sui generis and might not have been part of the original volume,Footnote 15 and the episcopal catalogue of Rouen, which finds its locus amongst a range of similar “reference lists” included on fols. 21v–24r.Footnote 16 Likewise, the Brevis cronica that once occupied fols. 42r–47v, according to the book's fifteenth-century list of contents (“Brevis cronica et compendiosa ducum Normannie”; Figure 5), belonged to neither of these two booklets, but to a separate one that was produced ca. 1400 in either Rouen or Paris (fols. 38r–51v; “Part C”).Footnote 17 These six folia containing the Brevis cronica were subsequently removed from the manuscript, though precisely when this happened is difficult to determine.Footnote 18 The fact that the two texts listed either side of the Brevis cronica in the contents list (“Genealogia aliquorum regum Francie per quam apparet quantum attinere potest regi Francie rex Navarre”; and “Unde processit regnum de Yvetot et quedam alia”) have both survived intact suggests that this removal was undertaken deliberately and not without some respect for the book's material integrity. In its former location, the Brevis cronica would thus have been bookended, at one end, by Richard Lescot's genealogy of the Frankish/French kings (fols. 39r–41v) and, at the other, by an anonymous account of the mythical kingdom of Yvetot (fol. 48r), both of which are still extant in the manuscript today.

Figure 5: Table of contents in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 14663, fol. iiv (detail). © Gallica. Reproduced with permission of the BnF.

From a textual perspective, the copies of the Brevis cronica found in B and C appear to be complete. There are no obvious lacunae and the narrative does not terminate unexpectedly. Scholars have long suspected that both B and C were copied directly from A†, and this is supported by the codicological evidence. Given that reliable accounts of the codicology of these two manuscripts and their relationship with A† exist in published form, there is no need for us to go into great detail here.Footnote 19 Rather, we will build on these existing discussions and expand them by focusing on the specific evidence of the folia that contain the Brevis cronica, which hitherto have escaped detailed commentary. To begin with, Tischler has shown that A†, fols. 41r–50v were written by a single scribe — identified by him as “Scribe B,” the main, and possibly only, scribe involved in the book's production —, likely during a single writing campaign.Footnote 20 Further insights can be generated by undertaking a conservative calculation of the average number of letters per line (and page) in the texts that originally bookended the Brevis cronica in A† (fols. 39r–41v and 48r) and projecting them onto the chronicle's two extant copies in B and C. Written in the same hand and as part of the same writing campaign as fols. 39r–41v and 48r, and thus presumably sharing these folia's mise-en-page, the six interim folia now missing from A† (fols. 42r–47v) together would have accommodated some 10,500–11,500 letters in total. An identical amount of text is occupied in both B and C by a combination of the Brevis cronica (B, fols. 150r–153v; C, fols. 168r–176r) and two shorter texts that relate to it, namely some excerpts from Dudo of Saint-Quentin's Historia Normannorum (hereafter HN), one of two main sources of the Brevis cronica (see below), and two genealogies of Normandy's ruling dynasties from the Viking chieftain Rollo (911–27) to King John II of France (1350–64), one composed in Latin, the other in French.Footnote 21

Both these texts were copied straight after, and attached directly onto, the final paragraph of the Brevis cronica (B, fols. 153v–154v; C, fols. 176r–178r). There is no rubric, incipit/excipit, or other marker to help distinguish them from the Brevis cronica proper and it would thus seem that they were intended to form a single textual unit. If this was the case, it would confirm what the calculation of letter forms has already suggested: that the same three texts were found on the six folia removed from A† at an unknown point in time. As our edition below makes clear, the scribal variants that exist between B and C are both too numerous and too substantial for the former to have served as the exemplar for the latter, and instead it would seem that both manuscripts derive from a shared exemplar. That this exemplar was indeed none other than A† is corroborated further by the fact that B and C preserve not only the Brevis cronica along with the excerpts from Dudo and the two genealogies, but also many of the other works contained in the same manuscript as part of a larger textual arrangement (or “dossier”) which, to our knowledge, has no parallel elsewhere.

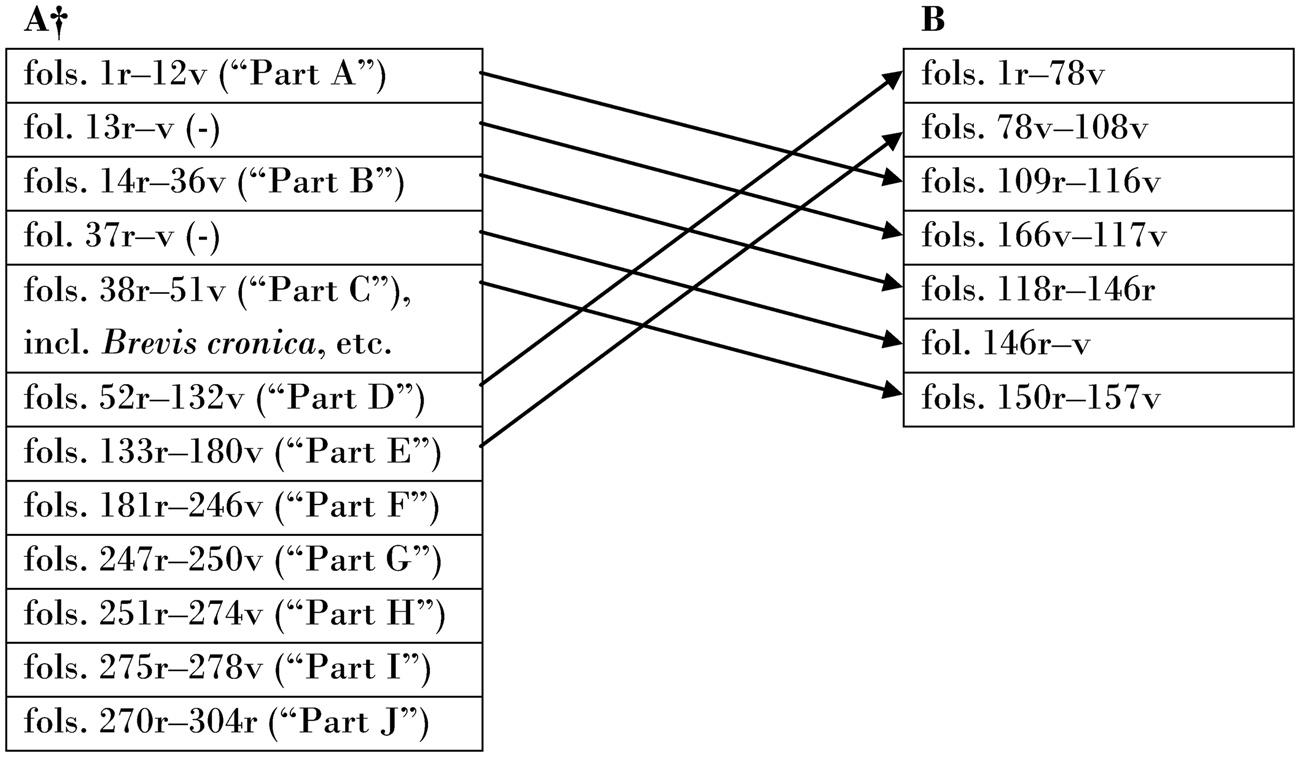

Of the forty-six texts contained in A†, no fewer than thirty reappear in B.Footnote 22 With both manuscripts essentially preserving their original order of contents,Footnote 23 it would seem that the copyist of B deliberately rearranged some of the texts by giving priority (and pride of place) to Einhard's Vita Karoli and the Anglo-Norman histories of William of Jumièges and Robert of Torigni with their thirteenth-century continuation(s) (fols. 52r–180v, “Part D” and “E”):

C condenses this selection even further by dropping the Vita Karoli altogether and instead refocussing its opening sections more or less exclusively on Anglo-Norman history.Footnote 24 As a result, the Brevis cronica in C follows on neatly (and almost seamlessly) from William of Jumièges's GND and Robert of Torigni's Chronica, copied on the basis of A†, fols. 68r–175r,Footnote 25 in effect emphasising its close relationship with both these texts.

What B and C have in common, therefore, is not only that they share an exemplar in A†, but also that their respective copyists made a concerted effort to reorganise and rearrange the contents of this exemplar so as to foreground particular groups of texts (or “textual milieus”), one of which, and perhaps the most coherent, concerned the history of Normandy and England during the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. In doing so, these copyists, consciously or otherwise, adopted an agenda that had been established, with a not dissimilar outlook, by the author of the Brevis cronica several generations earlier.

The author/scribe and his sources

Most of the texts contained in A† — and copied subsequently in B and C — are non-authorial works, that is, texts that the scribe copied from elsewhere, rather than composed himself. There are a few exceptions, however, most obviously perhaps the catalogues of secular and spiritual (and biblical) rulers provided in the manuscript's opening booklet.Footnote 26 Another exception is the selection of genealogies attached to the end of the Brevis cronica (fol. 154r–v). Of course, these can probably both be classified as auxiliary or “reference” works, rather than fully-fledged literary or historiographical compositions in their own right, and it seems likely that they were drawn up to assist with, and possibly act as finding aids for, the various narrative texts compiled elsewhere in the same volume. Their location towards the beginning of the book certainly would have facilitated this kind of auxiliary usage.Footnote 27 And yet, the production of such reference works suggests a somewhat more sophisticated scribal profile than one would expect from a mere copyist — an observation which is cemented further by the one text that can be considered “authorial” in the stricter sense: the Brevis cronica.Footnote 28

Unlike B and C, both of whose scribes remain anonymous, in the case of A† there is relatively concrete information not only about the manuscript's provenance and history of transmission, but also about its maker and original owner/user.Footnote 29 Indeed, as an erased colophon re-discovered under UV light by Gilbert Ouy on what was once the manuscript's first folio (now fol. 13r) makes clear, and which subsequent scribal analysis performed by Matthias Tischler has confirmed, we know that A† was made, in all its constituent parts, by a single individual, Simon de Plumetot.Footnote 30 A man of letters, a lawyer, and later an advisor of the French and English monarchs, Simon was born in Plumetot in Normandy (dép. Calvados, cant. Douvres-la-Délivrande) on 4 February 1371. He briefly studied at the monastic school of Saint-Victor in Paris before renouncing the life of the regular clergy to study for a baccalaureate in Law at the University of Orléans, ca. 1391–99.Footnote 31 Simon received ecclesiastical prebends at Senlis (1410), Chartres (1413), Caen, and Bayeux before becoming the advocate of King Charles VI at the parliament in Paris in 1413 — a role which he continued under the English rule of King Henry VI. Simon acted as counsellor at the Palace from 1423 and “conseiller à la Grande Chambre” from 1428. He died 9 July 1443.

As is indicated by this brief summary of Simon's personal and professional vita, he spent the majority of his adult life between Paris and Rouen.Footnote 32 While his student years at Saint-Victor and Orléans had primarily been devoted, respectively, to theological and legal matters, the period from 1399/1400 onwards saw Simon turn his attention increasingly to historical and antiquarian studies. Besides the history of France more generally, Simon's particular area of interest concerned the history of his native Normandy and its rulers, and it is in this context that his autograph volume A† finds its locus. Sitting comfortably amongst Simon's first-hand copies of the eleventh- and twelfth-century works of William of Jumièges, Robert of Torigni, and Ralph of Diceto, the Brevis cronica forms the pièce de résistance and authorial calling card of the historical compendium. Again, there are certain caveats. First, if the abovementioned colophon shows that Simon was responsible for creating A†, there is no actual disclosure of authorship anywhere in the text of the Brevis cronica itself. This, however, is hardly surprising, given the work's draft-like form, which, as will be seen below, corresponds well with what we know of Simon's working practices. On this point, it should also be stressed that labelling the text as “authorial” does not imply out-and-out originality. As far as its contents are concerned, the Brevis cronica is, if anything, profoundly derivative, being closely based on two pre-existing works: William of Jumièges's GND and Dudo of Saint-Quentin's HN.

Stylistically, however, the Brevis cronica is much more than just an amalgamation of the GND and HN that reproduces their contents verbatim. The use of word-for-word adaptation is surprisingly sporadic throughout, being limited mostly to short phrases, half-sentences, and sometimes individual words. The edition provided at the end of this study gives the text's verbatim citations (in bold for the HN, and in bold and italics for the GND) in their entirety, which is why two examples will suffice here:

Qui Robertus Rothomagensis respondit, quod nimis volebat equitare quam ultraque legem agere, et nichilominus prefatus dux Francorum contra regem rebellans fecit se in regem ungi, III.o kalendas julii. (B, fol. 150r; cf. HN, 173)

Ricardus etiam ejus filius qui Normannicam pene patriam unam Christi insignivit ecclesiam. Rusticos Normannie rebellare volentes, per Radulphum comitem castigari fecit, et truncatis manibus et pedibus, inutiles, dimisit ceteris exemplum prebens, qui ad sua aratra sunt reversi. Eadem tempestate Guillelmus ejusdem Ricardi frater ex patre, qui Guillelmus comitatum Oximensem habuerat inmunis, rebellavit contra fratrem, qui captus Rothomagi per quinquennium in carcere detrusus. (B, fols. 151v–152r; cf. GND, 2:6)

As these examples show, Simon was fairly selective in how he used the sources available to him. On the whole, he preferred to rephrase and refocus their narrative accounts, rather than copying them wholesale. Likewise, he exercised great selectivity in how he combined the different, and sometimes divergent, versions of events not only between the GND and HN, but also, and importantly, between the GND's various eleventh- and twelfth-century redactions, of which Simon appears to have used at least two.Footnote 33

For the early parts of its narrative up to the death of Duke Richard I of Normandy (942–96) (B, bottom of fol. 151v), the Brevis cronica draws more or less exclusively on Dudo's HN. This is true even in most cases where one of the GND's redactions offers an alternative or reproduces parts of the HN verbatim — as was the case with “redaction A,” whose anonymous eleventh-century redactor reproduced the four books of Dudo's work in full, and Robert of Torigni's “redaction F,” written ca. 1139–59, which re-inserted substantial passages of the HN back into the GND after they had been excised purposefully by both William of Jumièges (“redaction C,” ca. 1050–70) and Orderic Vitalis (“redaction E,” ca. 1109–1113).Footnote 34 There are two notable exceptions, however. In both cases, Simon can be seen to substitute, or at least supplement, the information provided by Dudo with a corresponding passage found in the GND. The first of these passages concerns the final years of Rollo's life (B, fol. 150v), where the Brevis cronica relies on Robert of Torigni's twelfth-century redaction of the GND, rather than on the HN directly, for its account of the Battle of Soissons in 923 and the subsequent acclamation of Rollo's son and successor, William Longsword.Footnote 35

The second passage that forms an exception to Simon's preferential treatment of the HN over the GND occurs shortly afterwards (bottom of B, fol. 150v). Here, the various events that shaped the aftermath of Rollo's death are grouped together succinctly in a single sentence closely mirroring the corresponding summary account provided in the GND, rather than the drawn-out narrative of the HN that stretches over several pages and follows a different sequence of events.Footnote 36 Apart from these exceptions, however, the Brevis cronica follows a straightforward pattern of composition in that it relies on the HN for as long as possible and only once Dudo's narrative comes to an end does it switch to the GND (B, fols. 151v–153v). Which and how many of the GND's redactions Simon used is difficult to determine, not least due to the limited amount of verbatim quotations. For the same reasons, it has proved impossible at this point to identify with absolute certainty his exemplar(s) among the surviving manuscripts of the GND and HN. Footnote 37 Given that Simon spent the best part of his career between Paris and Rouen, he presumably would have had access to the libraries of several institutions located in and around the two capital cities. One of these was Saint-Victor, where Simon had studied (briefly) as a young adult and to which he returned frequently during later decades. When leaving Paris for Rouen in the 1430s, where he had been appointed at the Exchequer by Henry VI, Simon gave most of his own treasured book collection to Saint-Victor, and A† was amongst it.Footnote 38 Another was the library at the abbey of Jumièges, some 20 km (as the crow flies) west of the Norman capital, the importance of which is discussed in more detail below.

For now, we can do little more than conclude that Simon likely used one of the following combinations of sources for his compilation of the Brevis cronica: (1) HN + GND “redaction F” + GND “redaction A”; (2) HN + GND “redaction F” + GND “redaction C”; or (3) GND “redaction F” + GND “redaction A.” Of these three combinations, the first two emerge as the most probable given the evidence discussed earlier in this article, though none of them can be verified or excluded with absolute certainty. Either way, Simon must have had access to at least two (if not more) manuscripts. These he combined creatively, and with much authorial esprit, when rewriting the history of his native Normandy in the fifteenth century.

The Brevis cronica in context

While we are thus able to date, attribute, and analyze the Brevis cronica in terms of its codicology and manuscript sources with relative confidence, establishing it in a wider historical and literary context poses more of a challenge. Indeed, while our analysis of the text reveals that Simon de Plumetot approached the task of composing the Brevis cronica with a certain amount of “creative flair,” falling somewhere between scriptor and compilator in St. Bonaventure's (1221–74) neat and oft-quoted definition of authorship, his authorial motives, which are never stated, can only be hypothesised.Footnote 39 What is more, the Brevis cronica's atypical form — it is not a straightforward copy, nor a continuation, nor a truly original work — means it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions as to its place both within the transmission of the GND and, more broadly, within French and Latin historical writing of the later Middle Ages.

We shall return to these issues below. For the moment, let us continue by setting the Brevis cronica within those wider contexts about which we can be more certain. In the first instance, we have already noted that the booklet in A† that once contained the Brevis cronica was produced ca. 1400 in either Rouen or Paris. It thus dates from the earlier part of Simon's career, when he was a man in his late 20s or early 30s, who had recently completed his legal studies at the University of Orléans. The Brevis cronica is, therefore, one of the earliest texts produced by Simon to survive in what remains of his private library, meticulously reconstructed by Gilbert Ouy over forty years ago,Footnote 40 and it certainly bears witness to Simon's first interaction with the HN and GND, the latter of which he would copy some years later (ca. 1402–1409 × 1414–16).Footnote 41 In terms of Simon's wider library, the manuscript in which the Brevis cronica was once found is one of several codices (some surviving, others not) to contain historiographical material. Of these, two are of particular interest, namely a lost manuscript once bearing the pressmark MS BBB.12 and Vatican Library, MS Ottoboni Lat. 3081, both of which we will look at in more detail below. For now, let us remark simply that A† is at once reflective of Simon de Plumetot's personal interests, which, in terms of historiography, focused on royal privilege and Anglo-French relations,Footnote 42 as well as of his private library more generally, which was formed, as far as we can tell, primarily of texts copied either by him or by others at his behest.Footnote 43 That said, if Simon's surviving library is notable for the number of copied texts it contains, as well as for its impressive range of autograph works,Footnote 44 one thing that distinguishes it is the lack of texts authored by Simon himself.Footnote 45 In this context, and in light of the observations made earlier in this article, the Brevis cronica can be said to represent something of an important exception.

Accepting this premise, however, brings us no closer to determining why Simon decided to create the text in the first place. In order for us to answer this key question, it is helpful to begin by establishing what the Brevis cronica is not. In the narrower sense, much of this has already been discussed above. Viewed more broadly, however, it is useful to compare the Brevis cronica with similar historiographical works, especially those with which Simon de Plumetot was familiar.Footnote 46 Indeed, the manuscript in which Simon's copy of the Brevis cronica was once found itself contains a number of historiographical texts similar in length and subject matter. These include the short history of the origins of the counts of Anjou extracted from the twelfth-century compilations of Ralph of Diceto, already noted above, and various abridged chronicles of the kings of France, including that written by Guillaume de Nangis.Footnote 47 Simon's interest in the history of his native land has been noted repeatedly by scholars, most recently by Isabelle Guyot-Bachy.Footnote 48 It would not be unreasonable to suggest, therefore, that, in creating the Brevis cronica, not only did Simon conceive of it as replicating for the Norman dukes that which he had seen elsewhere, but, given the volatility of Anglo-French relations in the early fifteenth century, that he also had some political or ideological motive for doing so.

Sadly, neither of these ideas holds up to closer inspection. In structural terms, both the short Anjou chronicle, which may not have even formed part of A† as originally bound, and the abridged chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis are more tightly ordered and polished texts than the Brevis cronica. Each presents the deeds of each count or king under individualized, separately headed sections, with the latter being deliberately ordered as such so as to help guide those visiting the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis.Footnote 49 By contrast, the Brevis cronica lacks any formal sense of structure, besides following a rather basic chronological outline. Stylistically, too, it is noticeably different from (and indeed inferior to) the histories produced by authors of earlier centuries such as William of Jumièges and Guillaume de Nangis, with much of its grammar and syntax being decidedly “draft-like.”Footnote 50 What is more, the Brevis cronica does not appear to have been produced with any specific political or ideological agenda in mind. It is therefore not a text that looks either to resituate the French kings within the history of Normandy, or to comment on their parentage in the way that other historiographical texts of this period, including those copied by Simon de Plumetot elsewhere in A†, sought to do.Footnote 51 It is also not a text that appears to pass judgement (or praise) on the dukes of Normandy, or on any other individual, in that the historical episodes selected by Simon do not cast anyone in a particularly negative or positive light (nor does Simon interject with comments of his own).

That said, if the Brevis cronica cannot be identified as a political or ideological text in its own right, it nevertheless forms part of a collection recognised as at once Norman and political in character.Footnote 52 If the latter of these two observations, in the light of what has just been noted, has relatively little bearing on the reasons why Simon authored the Brevis cronica, the first is central. As previously stated, the Brevis cronica is one of a number of historiographical texts contained in A† to relate to Normandy and in particular to its history during the Anglo-Norman and Angevin periods. Moreover, A† is not the only manuscript to bear witness to Simon's interest in his native land. His private library shows that he eagerly copied, collected, and/or created texts relating to various aspects of Normandy's past and that he did so making full use of his Norman contacts.Footnote 53 Both A† and the Vatican manuscript mentioned above contain marginal notes specifying the Norman repositories visited by Simon in his pursuit of texts,Footnote 54 while he was aided in this pursuit by three copyists (Guillaume de Longueuil, Adam de Baudribosc, and Hugues Berthelot), all of them Norman in both origin and outlook.Footnote 55

In the context of his “Norman” activities, the Brevis cronica as once found in “Part C” of A† was produced at around the same time (that is, ca. 1400) as “Part E” of the same manuscript, which contains a number of historiographical texts of Norman origin or focus. For our purposes, the most interesting of these is a compilation on Anglo-Norman history found in the part of the manuscript described by the fifteenth-century list of contents as “De cronicis Francie et Anglie ab anno Domini 1139 usque 1238.” It is one of two texts of this sort once found in Simon's library. The other previously formed part of the lost MS BBB.12 introduced above, which in the early sixteenth-century was held in the library of Saint-Victor in Paris.Footnote 56 Occupying the manuscript's first forty folia, the text is listed in a catalogue of the abbey's library as “Cronica Normannie in gallico, ab Hastingo, eorum duce, usque ad annum Domini 1223.”Footnote 57

This is of interest for a number of reasons. In the first instance, the fifteenth-century description of the text “De cronicis” in A† obscures its complexity and chronological scope. Comprised largely of excerpts from Robert of Torigni's Chronica and its thirteenth-century continuation, its final part (fols. 168v–175r) is formed of annalistic notes from the death of William the Conqueror in 1087 to the birth of Edward I in 1239. Unlike the Brevis cronica, Simon appears to have copied this text from the original, namely a reworking of extracts from the Annals of Jumièges, although it is not impossible he worked directly from the Annals and carried out this reworking himself.Footnote 58 What is more important, from our point of view, is the chronological range covered by these notes, for although they cannot be said to pick up precisely where the narrative of the Brevis cronica leaves off, ending as it does with William the Conqueror's return to Normandy following his successful invasion of England, they do begin in a chronologically consistent way with William's death. As for the lost “Cronica Normannie” in MS BBB.12, this, at least according to the above-mentioned catalogue, began its history of Normandy with the arrival of Hasting, just as the Brevis cronica does, and it ended at a point not too far removed from the Jumièges notes in A†, which include an entry on the death of Philip Augustus (1180–1223) and the coronation of his son, Louis VIII (1223–26), in 1223.Footnote 59

It would be misleading, of course, to suggest that the lost “Cronica Normannie” in MS BBB.12 was simply a combination of the Brevis cronica and the reworked notes from the Annals of Jumièges. Still, placed in this context, it is possible to see the Brevis cronica for what it is, namely a personal reference work, which Simon used (or intended to use) along with the Jumièges notes in relation to some wider project. This, it must be admitted, may have been nothing more than a desire to collect historiographical material relating to his native Normandy, and, as a consequence, to expand his nascent private library. It is not too far fetched to suggest, however, that Simon sought to collect and compile such texts not just out of intellectual curiosity, but with the aim of creating something new — in this instance, an extended chronicle of his native land, which, if we accept that the lost “Cronica Normannie” is this work, was written in the vernacular. Study of MS Ottoboni Lat. 3081, which is itself a partial copy of MS BBB.12, has shown how Simon collaborated with his copyist, Adam de Baudribosc, in the drafting of an historical compilation.Footnote 60 It would be perfectly within reason, therefore, to suggest that the same dynamic may have also been behind the creation of the lost “Cronica Normannie” and, by extension, the Jumièges notes and the Brevis cronica.

Whatever the case may be, the Brevis cronica is characteristic of Simon's historiographical working methods, which involved scouring libraries and compiling texts based on what he found. As noted above, we can only hypothesize as to which and how many existing copies of the GND Simon used as exemplars in his writing of the Brevis cronica. Analysis of his copy of the GND in A† shows it is from a manuscript of Norman provenance of unknown origin now at Leiden.Footnote 61 We know that Simon interacted with the Annals of Jumièges ca. 1400–1402, written at a house from whose abbot he had requested a grace expectative (that is, an anticipatory grant of ecclesiastical benefices) just a few years earlier.Footnote 62 In light of this, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that he was probably familiar with the copy of the GND, now Rouen, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 1173 (Y. 11), known to have come from this same monastery;Footnote 63 that the Leiden manuscript perhaps also came from Jumièges; and that Simon de Plumetot used either one or both in compiling the Brevis cronica. In support of such ideas, it is also worth noting that the abbot from whom Simon had requested a grace expectative in the 1390s, and to whom he would have addressed any request to access the monastic library, was none other than Simon du Bosc (1391–1418), a fellow Norman intellectual and avid collector of books. As Annick Brabant has shown, the bibliophile abbot of Jumièges and his namesake would both come to play a role in documenting early fifteenth-century attempts to resolve the so-called Western Schism, and while it has been argued that they shared no known links besides being Norman, it is thus possible, and perhaps likely, that the Brevis cronica stands as witness to previously undetected interactions between the two men.Footnote 64

For the moment, however, such things must remain the subject of conjecture. Nevertheless, one thing to which the Brevis cronica can be said with confidence to stand witness is the use and transmission of the GND across the centuries. Described fittingly by van Houts as “a living text,” the GND was revised and updated by various authors throughout the central Middle Ages for various purposes.Footnote 65 While the Brevis cronica is in no way a polished and lengthy work in the manner of those produced by some of the GND's previous adapters and continuators, such as Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Torigni, the evidence discussed above shows how it may have been used as the basis for a much larger project: a new vernacular history of Normandy, likely written in French, from the raids of Hasting to the death of Philip Augustus, to whose control the duchy had reverted in 1204. If this was indeed the case, then the period in which this work was undertaken, during which Anglo-French relations steadily deteriorated, resulting in the eventual occupation of Rouen by English forces, could not have been more apposite.

Note on the edition and translation

Given today's absence of the Brevis cronica from A†, the following edition is based on the text as it survives in B, with the variants of C noted throughout. (When both B and C contain an error, the correction has been supplied in the main text, with the original highlighted in bold in the footnotes.) This selection of B as the edition's base text is justified by both its relative location within the text's manuscript tradition (earlier than C) and its superiority (when compared to C) in terms of the textual quality, integrity, and lack of corruption. The folio numbers of B are printed in square brackets in the Latin text. Although the original punctuation of the Brevis cronica is very much in keeping with its “draft-like” form, it has here been modernized according to the norms of this journal. For the same reason, all abbreviations have been expanded silently. In terms of orthography, “u/v” and “i/j” are kept as distinct vowels and consonants, respectively. To avoid confusion, quotation marks are used to indicate reported speech, although neither scribe uses them. Within the main text, the following symbols are used:

[[ ]] indicates supply by the editors of letters/words missing from B but present in C.

< > indicates supply by the editors of letters/words omitted by the scribe.

† † indicates words transcribed as they are found in the manuscripts, but for which no known Latin word has been idenfitied or which make no grammatical sense in the context of the sentence within which they are found.

For ease of reference, the text copied verbatim by Simon de Plumetot from his two main sources has been highlighted in bold (HN) and in bold and italics (GND). Section numbers have also been introduced for the benefit of the reader. These mostly follow the rubricated paragraph marks found in B, but some of them have been inserted in the absence of such marks to avoid unwieldy and overly long paragraphs, and to facilitate study.

The translation does not pretend to offer a strict, literal rendering of the original Latin into modern English to the exacting standards that could be achieved by philologist experts. Rather, it attempts to provide a readable, modernized, and user-friendly translation of the text that can be appreciated by academic colleagues and students wishing to engage with the Brevis cronica primarily in terms of its narrative content and literary-historical context. Where possible, the individuals mentioned, and their dates of birth, death, or office, are identified in the footnotes. Place names are also identified according to the standard French practice of listing department, canton, and, where applicable, commune.

Edition

[Fol. 150r] Brevis cronica compendiosaFootnote 1 ducum Normannie.

[§1] Daci gloriantur se ex AnthenoreFootnote 2 progenitos. Dux Dacorum Hastinus Franciam cum suis appulit eamque devastat, postea Rome iter arripuit et Lunx urbem,Footnote 3 que Luna dicitur, in dolo se mortuum fingendo cepit, et gloriabatur se Romam cepisse, cujusFootnote 4 rei contrario conperto, eam incendit, et ad Franciam revertitur, et cum rege Francorum mediantibus donis ab ipso Hastino receptis pacificatur. Interea rex Dacie voluit plures de suis a regno expellere, cui expulsioni Rollo et Gurim filii cujusdam potentissimi ducis Dacie, qui quasi totam Daciam sibi acquisierat, se opposuerunt ad requestam juvenum prescriptorum, rex Dacie eos invadit. Cujus victoriam illaFootnote 5 vice habuerunt. Sed altera die subdole Gurim in bello occidit et Rollonem fugavit. Qui Rollo Stanzam insulam applicuitFootnote 6 cum sex navibus, ipseque in sompnis monitus ad Anglos perrexit.

[§2] Modus autem monitionis fuit iste: “Rollo, velociter surge, pontum festinanter navigioFootnote 7 transmeans, ad Anglos perge. Ibi audies quod ad patriam sospes reverteris, perpetuaque pace in ea sine detrimento frueris.” Quod sompnum a christicolaFootnote 8 sapiente interpretatus est hoc modo.

[§3] “Tu, vergente futuri temporis cursu, sacrosancto baptismate purificaberis, predignus <que> christicola efficieris, et ab errore fluctuantis seculi ad AnglosFootnote 9 pervenies, pacemque glorie perhennis cum illis habebis.” Statimque aliquos AnglosFootnote 10 sue dicioni subjugavit, et monitus per sompnum facta prius federacione inter Alstenum regem Anglorum. Wulgraniam non sine maris periculo appulit, et terram illam et Frisiam devastavit et sub tributo posuit, et RainerumFootnote 11 Bugicoli cepit et tandem dimisit. Et anno ab incarnatione Domini octingentesimo LXXVIoFootnote 12 per fluvium Secane apud Gimesium appulit,Footnote 13 et in ecclesia Sancti Vedasti corpus beate Hameltrudis supra altare posuit ibique cappellam ejusdem nomine edificavit,Footnote 14 et Rotom<ag>ensibusFootnote 15 securitatem dedit. Rothomagi venit sine difficultate per portam Sancti Martini elegitque in illis partibus residere.

[§4] Ad Archas ivit, post hec Meulentum cepit, et Parisium obsedit et Baiocas cepit, et eam subvertit, filiamque Berengarii principis sibi connubio ascivit, ex qua GuillelmumFootnote 16 suscepit. Rediitque Parisiis et Ebrocas aliquos de suis misit, et cepit et revertitur apud Lontessiam.Footnote 17 AngliFootnote 18 sciens RollonemFootnote 19 Parisiensem civitatem obsedisse, contra eorum regem AlstemumFootnote 20 rebellarunt, qui auxilium Rollonis petiit et obtinuit, deditque RolloniFootnote 21 dimidium regni ad hoc ut rebelles subjugaret, quibus sub jugo per dictum Rollonem positis et reconciliatisFootnote 22 medietatem regni reorum eidem Rolloni devorant sed Rollo ei reddidit, tantum requirens, ut qui eum sequi maluerint non prohiberet. Rex autem hec annuens voluit secum ire in Franciam, [[quod refutavit reversusque Rollo in Francia]], excercitus suos dividit.

[§5] Karolus rex per medium Franconis archiepiscopiFootnote 23 Rothomagensis pacem cum eo querit, et obtinet trium mensium dumtaxat. Quibus finitis consilio Ricardi et Ebali Burgundiones et Franci bellare contra Rollonem ceperunt. Rollo veroFootnote 24 Francia<m> laniare et terras usque Clarum Montem devastare,Footnote 25 et per Sanctum Benedictum quemFootnote 26 non contaminavit. Stampas devastavit, et Parisius remeando rusticos debellavit, et Carnotum [fol. 150v] obsedit et ibi bellum crudele cum Francis et BurgundionibusFootnote 27 habuit, tandem episcopo cum cruce et armis bellum intrante, Rollo declinavit ab excercituFootnote 28 ne morte preocuparetur. Ebulus qui non fuerat in bello excercitum paganorum in Monte LeugasFootnote 29 insequitur, sed non profuit. Rollo totamFootnote 30 patriam cepit amplius devastare. Franci petunt a Karolo quod pax et concordia fiat cum Rollone dando ei filiam suamFootnote 31 Gislam, et terram ab Epte fluvio usque ad mare, quod Francone archiepiscopo Rothomagensi intercedente factum est. Et a Roberto duce suscipitur Rollo de sacro fonte pacto prius interveniente, per quod BritanniamFootnote 32 donec terra prius dicta culta foret, concedebat, refutata Flandria tanquam paludosa. Non tamen voluit regis pedem osculari sed precepit militi, qui regem fecit resupinum. Sicque baptizatus fuit Rollo anno incarnationis nongentesimo XIIo,Footnote 33 et Robertus inFootnote 34 sacro fonte nominatus, et sic per XXXVI annos ab eventu suo usque ad baptismum patriam devastaverat, sed suscepto baptismate ecclesias dotavit, et residuum [[predictis]] suis gentibus divisit, et postea dictam Gislam in uxorem assumpsit. Jura et decreta leges sempiternas principum sanctitas et decretas, plebi indixit. BritannicosFootnote 35 sibi rebelles subjugavit, furtum prohibuit.

[§6] Legatos Karoli regis eo inscio cum uxore diu colloquium habentes publice jugulari fecit. Quod audiens Robertus dux Francorum pacis federa disrupta intelligens contra regem Karolum stetit, misitque legatos Roberto, qui prius Rollo dicebatur Rothomagensis, dicens se velle regnum Francorum contra Karolum acquirere. Qui Robertus Rothomagensis respondit, quod nimis volebat equitare quam ultraqueFootnote 36 legem agere, et nichilominus prefatus dux Francorum contra regem rebellans fecit se inFootnote 37 regem ungi, III.o kalendas julii. Sed rex Karolus ante finem anni regnum recuperavit et dictum ducem peremit, sed Herbertus comes ipsum Karolum cepit, et in castro Perone usque ad mortem detinuit. Cui successit RadulfusFootnote 38 filius Ricardi ducis Burgundie, dicti Karoli filiolus uxorque dicti Karoli cum Ludovico filio suoFootnote 39 ad patrem suum regem Anglie profecit, animositatem Herberti et HugonisFootnote 40 Magni, filii predicti Roberti ducis Francorum, nimium metuens.

[§7] Rollo vero defunctaFootnote 41 uxore sua, Popam, ex qua Willelmum filium susceperat iterum repetensFootnote 42 sibi copulavit, et vocatis Normannis et Britonibus dictum GuillelmumFootnote 43 illis exponit, et eum in eorum dominum prefecit,Footnote 44 eosdemque sub sacramento fidei filio subegit. Post hoc uno vivens lustro consumptus senio hominem exuit in Christo.

[§8] Post Rollonis obitum, Guillelmus ejus et Pope filius, qui Bothoni ditissimo comiti ad educandum commendatus fuerat, et voluerat se fieri monachum, et Gimesias voluerat ingredi cepit amplius crescere. Britones contra eum rebellantes subjugavit, et Berengarium eorum ducem sub sacramento perseverande fidelitatis et servicii sibi connexuit, et Alanum fugavit qui Angliam adiit. Qui GuillelmusFootnote 45 uxorem accepit, et Hugoni Magno atque Herberto se reconciliavit.Footnote 46

[§9] Post hec RiulfusFootnote 47 perfidus rebellavit contra eum, quem cum suis complicibus in Prato Belli propre Rothomagum debellavit, et redeundoFootnote 48 de bello [fol. 151r] nuncium de filii nativitate habuit, sicque exaltatus est quod Franci, Burgundi, Flandrenses,Footnote 49 Angli et Dacigene,Footnote 50 et IsbernensesFootnote 51 ei parebant. Filiam suam GuillelmoFootnote 52 Pictavensi nupsit. Herbertus vero dedit dicto GuillelmoFootnote 53 Rothomagensi, consilio Hugonis Magni ducis, filiam suam in uxorem. Rex Anglie Alste<m>us misit eidem GuillelmoFootnote 54 legatos, cum muneribus, deprecansFootnote 55 ut Ludovicum, nepotem suum, et Alstemum filium dicti Karoli regis Francie revocaret ad Francie regnum, et susciperet Alanum a BritanniaFootnote 56 offensionis culpa ejectum. Et ilico,Footnote 57 consultu dicti Guillelmi,Footnote 58 Hugo Magnus dux atque Herbertus satrapa principum, ascitis episcopis consilio metropolitanorum, revocaverunt festinanter dictum Ludovicum, et eum unxerunt sibi regem populorum Francia, Burgundiaque morantium. Alanum vero cum Ludovico regressum, Guillelmus,Footnote 59 pro amore regis Alstemi, recepit.

[§10] Elapso autem lustri spacio, ceperunt Franci contra Ludovicum rebellare, qui a Henrico rege TrasuhenanumFootnote 60 petens auxilium non potuit nisi per medium GuillelmiFootnote 61 obtinere. Cum quo Guillelmo predictus Ludovicus Rothomagi diu mansit, misitque legatosFootnote 62 idem Guillelmus ad dictum regem Henricum pro pace procuranda. Qui rex Henricus remisit legatosFootnote 63 et cum eis Cononem ducem pro obside pacem tractando, quem Guillelmus noluit retinere sed secum duxit ad placitum cum Ludovico rege Francorum in pago Laudunensi contra Hugonem et Herbertum, et ibi confederantur Henricus et LudovicusFootnote 64 reges, presentibus non tamen consentientibus Hugone et Herberto. Nichilominus Ludovicus rex reconciliatur et LaudunensiFootnote 65 revertitur. Et audito quod filium scilicetFootnote 66 ex uxore Gerberga natum haberet, fecit eum per GuillelmumFootnote 67 de sacro fonte levari et LothariumFootnote 68 vocari. Quibus peractis Guillelmus ad propria rediensFootnote 69 construxit GemesiasFootnote 70 templum mirabile et a Martino loci abbate inquisivit: “Cur christiana religio tripertito ordine ecclesiam frequentat?” Quo declarato omnino voluit fieri monachus, ibidem, Normannique et Britones sacramento fidei Ricardo ejus filio se submiserunt. Postquam Arnulphus Flandrensis marchioFootnote 71 abstulit Heluino castrum, quod dicitur Monasterioli. Qui Heluinus primo Hugonis ducis auxilio petito et denegato a Guillelmo duce auxilium obtinuit, per quod dictum castrum recuperavit.

[§11] Arnulphus vero capta pace trium mensium cum Guillelmo ad placitum convenerunt, in quo prodicione et subdole Guillelmus dux occiditur, per Arnulphum, anno incarnationis Domini no<n>gentesimo XLIIIo,Footnote 72 XVIo kalendas januarii, rege Ludovico regnum Francie tenente.Footnote 73 Quo defuncto,Footnote 74 Britones et Normanni RicardumFootnote 75 ejus filium pro duce sibi iterum constituerunt. Audito per Ludovicum obitu GuillelmiFootnote 76 venit Rothomagum, et secum retinuit Ricardum puerum, quod displicuit civibus et impediverunt et tandem habuit eum ad educandum. Finxitque Ludovicus velle capere Atrabatum et destruere Arnulphum, sed misertus est dicto Arnulpho consiliariis ipsius Ludovici muneribus excecatis, detinuitque consilio dicti Arnulphi dictum Ricardum. Quod audientes Rothomagenses processionaliter per totam Normanniam pro eo oraverunt, tandem diligentia OsmundiFootnote 77 ejus servitoris, faventibus Bernardo Silvanectensis comite et Hugone [fol. 151v] Magno duce, submovetur.

[§12] Ludovicus consulit Arnulphum quid agendum. Suadet quod Hugoni det Normanniam a Secana usque ad mare, residuo pro se retento, quod fecit et Hugo consentiit. Statimque Bernardus Silvanectensis hec Bernardo scilicet Rothomagensis remandavit, postquam Ludovicus in Caleto et Hugo Baiocas accesserunt cum magnis excercitibus patriam devastantes. Quod videns, Bernardus de CygenaFootnote 78 in dolo mandat regi ut Rothomagi veniat dominaturus ibidem, et Hugoni mandet quodFootnote 79 recedat a patria Normannie, quod et fecit. Normanni vero videntes quod Ludovicus eisdem dominaretur, miserunt ad Hailgrodum Dacie regem qui eorum auxilio veniens Francigenas debellavit .XVIII. comites, et Heluino computato interfecit, et regem Ludovicum cepit, qui tamen evasit, dum custodes spoliis intenderent. Postquam repetitus,Footnote 80 a milite Normanno Rothomagi ducitur, quamvis prius intenderet eum liberare, et †laudum ducem† regina Francorum auxilium petiit pro marito a rege Henrico ejus patre, qui omnino refutavit dicens quod merito hec paciebatur Ludovicus. Postquam consilio Hugonis Magni Ludovicus datis prius in obsidibus filio cum duobus episcopis deliberatur seu relaxatur.Footnote 81 Tandem idem Ludovicus totam Normanniam dicto Ricardo dimisit, a nemine nisi a solo Deo tenendum perpetuo. Qui Ricardus RadulphumFootnote 82 Torta principem militieFootnote 83 male administrantem et domigenas ducis inedie comprimentem, sapienter a terra fugavit, †ficte† non armis sed prudencia, qui Torta Parisius ad ejus filium loci episcopum accessit.

[§13] Ricardus vero dux, qui Normanniam nulli subjectam nisi Deo tenebat, filiam Hugonis Magni ducis ParisiensisFootnote 84 duxit in uxorem servicio dicti Hugonis se subiciens. Quod videntes Ludovicus et Arnulphus Flandrensis, predicti ArnulphiFootnote 85 consilio, Ludovicus Othoni regi TrasuehnanoFootnote 86 fratri uxoris sue totam Lothoriam dedit, ut Hugonem Magnum destrueret, sicque posset Normanniam dictus Ludovicus acquirere, que majoris precii et valencie erat quam regnum Lothoringie predictum. Qui Otho terram Hugonis usque Parisius devastavit, RothomagumFootnote 87 consilio Arnulphi obsedit, sed minime profecit. Postquam Lotharius rex Francie ejusdem Ludovici filius multum dictum Ricardum infestavit. Sed dux, Dacorum auxilio, cum dicto rege obtinuit pacem et concordiam. Dacosque volentes ad fidem converti in patria ditavit, ceteros cum muneribus ad propria remisit.

[§14] Defunctaque RicardiFootnote 88 uxore dicti Hugonis Magni filia, duos filios et totidem filias ex concubinis suscepit, quorum unus Gaudefridus, alter vero Guillelmus nuncupatur. Posteaque nobili cuidam Daci, Guinori videlicet, †ad suorum† maritali federeFootnote 89 copulatur, ex qua quinque filios et tres filias habuit; ecclesiam beate Marie Rothomagi, sancti Michaelis in Monte, et sancte Trinitatis in Fiscanno mirabiliterFootnote 90 construxit; Arnulphum comitem Flandrie cum Lothario pacificavit. Ricardum cujus filium sibi successurum ordinavit, et in pace requievit anno Domini nongentesimoFootnote 91 nonagesimo sexto, sicque post patris obitum per LIII annos regnavit.

[§15] Ricardus etiam ejus filius qui Normannicam pene patriam unam Christi [fol. 152r] insignivit ecclesiam. Rusticos Normannie rebellare volentes, per Radulphum comitem castigari fecit, et truncatis manibus et pedibus, inutiles, dimisit ceteris exemplum prebens, qui ad sua aratra sunt reversi. Eadem tempestate Guillelmus ejusdem Ricardi frater ex patre, qui Guillelmus comitatum Oximensem habuerat inmunis, rebellavit contra fratrem, qui captus Rothomagi per quinquennium in carcere detrusus.Footnote 92 Quo elapso per fenestram cum longo fune ad terram lapsus, primo voluit latitare, et tandem ad ducis pedes cadens veniam petiit, et obtinuit, ac OximensemFootnote 93 comitatum reddidit,Footnote 94 et eidem nobilem filiam Turchetilli in uxorem tradiditFootnote 95 nomine Litselmam,Footnote 96 ex qua tres filios habuit, Robertum videlicet qui ei successit, Guillelmum Suessionem comitem, et Guillelmum LuxoviensemFootnote 97 presulem.

[§16] Eodem tempore rex Anglorum Aeldebredus, Emmem ducis sororem inFootnote 98 conjugio habens, Normanniam sibi volens subjugare, misit suos ut terram devastarent, excepto Sancto Michaele, et regi ducem adducerent.Footnote 99 Qui Anglici in pago Constantiensi descendentes per milites Constantienses cum vulgo occisi sunt, quibus auditis rex erubuit insipientiam agnoscens.

[§17] Eo tempore Gaufridus Britannorum comes sororem dicti ducis nomine Haduis habuit in uxorem, ex qua duos filios suscepit, Alanum videlicet, et Eudonem, qui post patris obitum BritanniamFootnote 100 diutius rexerunt. Postquam rex AnglorumFootnote 101 <E>delredus jussit omnes Danos qui in Anglia morabantur, sine sexusFootnote 102 aut etatis distinctione, occidi, quod cum audisset rex Suenus Danamarchie per mare veniens totam Angliam vastavit. Rex vero Anglie cum duobus filiis, Eduardo scilicet et Alvredo, Normanniam adiit cum duce Ricardo qui eum honorifice recepit. Qui rex Anglie audito obitu Sueni in Angliam venit, ibi obiit. Cui successit rex Chunitus filius Sueni. Qui Chunitus Emmam Anglorum regisFootnote 103 relictam in uxorem accepit, ex qua suscepit filium †pars† Hardechunutum postea Danorum regem et filiam Gumildam que Romanorum imperatori nupsit.

[§18] Eodem tempore Odo Carnotensis comes MathildemFootnote 104 Ricardi ducis Normannorum sororem duxit uxorem. Cui dux dedit in dotem castrum DorcasiniFootnote 105 cum terraFootnote 106 flumine adjacente. Qua defunctaFootnote 107 sine liberis duci volenti terram repetere Odo contradixit nolensFootnote 108 tuicionem castri Dorcasini reddere. Sed tandem tractanteFootnote 109 Roberto rege Francorum, metu paganorum superveniencium, concordantur, sicque castrum Dorcasini remansit Odoni, terra vero et castrum Tegulense Ricardus habuit. Prefatus dux Ricardus GaufridiFootnote 110 comitis Britannorum sororem nomine Judith uxorem habuit,Footnote 111 ex qua tres filios, Ricardum et Robertum ac Guillelmum.Footnote 112 Qui Ricardus eidem in ducatuFootnote 113 successit, et Robertus Oxomensis comitatum habuit a fratre Ricardo tenendum. Obiit autemFootnote 114 Ricardus secundus anno Domini millesimo XXVIo, et per XXX annos post Ricardum primum ejus patrem regnavit. Predictus vero Ricardus tercius fratrem suum Robertum comitem OximensemFootnote 115 contra eum rebellantem in castro FalesieFootnote 116 devi<n>xit. Tandem concordia facta, [fol. 152v] veneno cum nonnullis de suis, ut retulerunt plurimi, obiit anno millesimo XXVIIIo, sicque per duos annos dumtaxat regnavit. Cui successit Robertus ejus frater. Qui Robertus dux Robertum archipresulem exulavit, et postea revocavit. Postquam Guillelmum BelemensemFootnote 117, qui ab eo castrum Alencii tenebatFootnote 118 rebellantem, debellavit, et doloreFootnote 119 animam efflavit.

[§19] EodemFootnote 120 tempore Balduinus satrapa Flandrensis petiit et obtinuit pro Balduino filio suo Roberti regisFootnote 121 Francorum filiam. Qui Balduinus filius patrem suum a solo pepulit, qui pater Roberti ducis Normannie <fretus auxilio> †resatum†Footnote 122 patrie, et cetera, et eidemFootnote 123 ejus filius reconciliatur.Footnote 124

[§20] Eodem tempore Robertus rex Francorum moritur, cui successit Henricus, cui Henrico mater insidians eum a regno expellere nititur, et Robertum ducem Burgundionum eidem subrogare. Qui Henricus Roberti ducis Normannie fretus auxilio, adjutorio Maugerii comitis Corbulensis, reconciliantur.Footnote 125 Postquam Alani comitis Britonum rebellantis facto castro apud Casnon,Footnote 126 quod CarrucasFootnote 127 nuncupatur, patriam vastavit.

[§21] Eodem tempore, tractante duce Normannorum, Chunutus, qui regnum Anglie occupabat,Footnote 128 regni ipsius medietatem duobus filiis AlvrediFootnote 129 a regno expulsis reddidit, et cetera. Postquam Robertus dux NormannieFootnote 130 Jherosolimam petiit relicto GuillelmoFootnote 131 ejus filio unico, et tandem rediensFootnote 132 de peregrinacione in Nicena urbe anno Domini Mo XXXIIIIIoFootnote 133 obiit, sicque per sex annos dumtaxat regnavit.

[§22] Guillelmus vero ejus filius eiFootnote 134 successit, tenerrimaFootnote 135 tamen etate existens. Quo tempore multi ab ejus fidelitate se subtraxerunt, comes OxensisFootnote 136 tutor ducis occiditur, dolosis ortatibus RadulphiFootnote 137 de Waceyo per manus Odonis Grossi et Roberti filii Geroii.

[§23] Eodemque tempore RogeriusFootnote 138 ToenitesFootnote 139 deFootnote 140 stirpe Malahulcii,Footnote 141 qui RollonisFootnote 142 ducis patruus fuerat, noluit GuillelmoFootnote 143 duci obedire pro eo quod nothus erat, ymo contra eum rebellavit, omnesque vicinos suos despiciebat, et eorum terras vastabat, maxime terras UmfrediFootnote 144 de Vetulis. Quod tamen dictus Umfredus egre ferens suum filium Rogerum de Bellomonte contra eum misit, qui de Bellomonte victoriam habuit, dictusque Rogerius Toenites cum duobus filiis ibi occiduntur. RogeriusFootnote 145 vero de Bellomonte abbaciam de Pratellis in suo territorio fundavit, duci Normannie fidelis extitit. Duos filios, videlicet Robertum et Henricum,Footnote 146 ex Aelina comitis MellentisFootnote 147 filia procreavit. Qui Robertus postea comes Mellentis fuit, et Henricus dono GuillelmiFootnote 148 regis in Anglia comitatum WarelhuichFootnote 149 promeruit. Postquam crescente Guillelmo duce Normannie Radulphus de Waceyo eidem tutor et princeps milicie Normannie constituitur.

[§24] Eodem tempore rex Francorum Henricus, inmemor beneficiorum sibi a duce Roberto impensorum, castrum Tegulense, GislebertoFootnote 150 Crispini pro custodia comissa invicto dicto Crispini et ducisFootnote 151 precibus victo, cepit, et igne cremari fecit, et post hec similiter Argentonum. Postmodum Turstenus, cognomento Goz AnfridiFootnote 152 Dani filius, qui preses Oximensis erat, zelo infidelitatis succensus, milites stipendiis conduxit ad muniendum FalesieFootnote 153 castellum, sed Radulphus Waceyensis magister militum partem muri corruit, et tandem Turstenus aufugit et castrum dimisit. Ricardus vero ejusdem [Fol. 153r] Tursteni filius [[duci]] optime servivit, patrem suum reconciliavit,Footnote 154 et multo majora quam pater amiserat acquisivit.

[§25] Eodem tempore Malgerus frater Roberti ducis Roberto archiepiscopo Rothomagensis successit. Nam Ricardus Gunerides mortua uxore sua Judheit,Footnote 155 aliam nomine Papiam, duxit, ex qua dictum Malgerum, et Guillelmum Archacensem, cui Guillelmo Archasensi dux GuillelmusFootnote 156 ejus nepos comitatum Talogi, ut inde illi serviret, concessit. Ipse vero [[G.]] Archacensis castrum Archiarum in cacumine montis condidit, et post hec GuillelmoFootnote 157 duci rebellavit. Dux vero pro ipso mandavit ad hoc ut exhiberet servicium, quod facere recusavit. Dux autem ad radicem montis castrum stabilivit, ac adjutorio Henrici regis non obstante, prefatus Guillelmus predicto GuillelmoFootnote 158 duci dictum castrum dimisit.

[§26] Eodem tempore rex Anglie Chunutus obiit, cui successit Heroldus ejus filius ex concubina natus. Cujus ChunutiFootnote 159 EduardusFootnote 160 audiens obitum, adhuc cum duce GuillelmoFootnote 161 degens cum XL Footnote 162 navibus militibus plenis, Hamtornam appulit, et ibi multitudinem Anglorum offendit, et in Normannia cum preda rediit.Footnote 163 Interea frater ejus Alvredus Doroberniam venit et Goduinum comitem obvium habuit, quem Alvredum idem comes in sua fide suscepit. Et post eadem nocte eum ligatis manibus HeroldoFootnote 164 regi apud Londoniam destinavit, cui oculosFootnote 165 crepuit et suis militibus capita amputari fecit. Statim post Heroldus obiit, cui successit frater ejus Hardechunutus a Dacia egressus, ex Emma, EduuardiFootnote 166 matre, natus, qui post paululum confirmatus in culmine regni fratrem suum Eduuardum a Normannia revocavit ac secum cohabitare Footnote 167 fecit, quo Hardechunuto mortuo Eduuardum Footnote 168 totius regni Anglie heredemFootnote 169 reliquit. Qui Gaduino remisit perniciem ejus fratrem perpetratam, rexitque regnum Anglorum fere XXIIIbus annis.

[§27] Post hec GuillelmusFootnote 170 dux Guillelmum, cognomento Werlencus, comitem Moritolii, a Normannia exulavit, et dux comitatum Moritomensem Roberto fratri suo concessit. Postea vero GuillelmusFootnote 171 BusaciusFootnote 172 volens subjugare ducatum a Guillelmo duce exulare cogitur.

[§28] Hoc tempore dux filiam Balduini FlandrensisFootnote 173 sibi uxorem copulavit, que ejus erat consanguinea, sed postea a papa dispensacionem obtinuit, et ob hoc duas ecclesias in Cadomo fundaverunt. Postmodumque videlicet anno Mo LIIIIoFootnote 174 rex Francie Henricus unctus, NormanniamFootnote 175 infestat, dicens quod NormanniFootnote 176 per violenciam hanc patriam sibi vendicaverant sed dux fortiter obstitit.

[§29] Postea vero EduuardusFootnote 177 rex Anglie obiit sine prole, qui antea Guillelmum ducem sibi heredem instituerat sibique Heraldum miserat qui eidem duci fidelitatem de regno Anglie fecit. Dux vero eidem Adelizam filiam suam cum medietate regni Anglici se daturum spopondit,Footnote 178 et eum in Anglia retento Vulnoto ejus fratre in obside remisit. Mortuo vero dicto EduuardoFootnote 179 regi anno Domini Mo LXVoFootnote 180 Heraldus continuoFootnote 181 regnum invasit contra fidem quam duci federat,Footnote 182 ut est tactum.

[Fol. 153v] [§30] Eodem tempore apparuitFootnote 183 cometes in partibus illis que mutacionem regni alicujus, ut plurimi asseruerunt, designavit.

[§31] Eodem anno Mo LXVoFootnote 184 Guillelmus dux Normannie per Chunanum comitem Britannie aliquantulum territus est, petiit enim sibi reddi Normanniam aut bellum inferre promisit. Sicque GuillelmusFootnote 185 effectus securus classem ad tria milia navium festinanter construi fecit, et in Pontivo apud Sanctum WalericumFootnote 186 congrue stare fecit. Ingentem quoque excercitum ex Normannis, Flandrensibus, Francis et Britonibus aggregavit, et trans mare Pevevessellum appulit, ubi castrum unum, et deinde apud HastingasFootnote 187 aliud firmavit. Tunc enim HeroldusFootnote 188 inFootnote 189 guerra quam contra Tostium fratrem suum [[habebat erat occuppatus in qua guerra fratrem suum]] et regem Northime congrue occidit. Statimque auditis novis de ingressu ducis Normannorum contra <consilium> matris et fratris sui Worth comitis per sex dies innumeram Anglorum multitudinem congregavit. Dux vero excercitum suum et legiones militum in tribus ordinibus disposuit, et horrendo hosti intrepidusFootnote 190 hora diei tercia diluculo sabbati obviam processit, et bellum commisit usque ad noctem. Ibique in primo congressu HeroldusFootnote 191 letaliter vulneratus occubuit. Angli vero de nocte fugientes a Normannis insequuntur, ibique XV milia perierunt de judice. Idem quoque judex nocte sequentis dominice Anglos vindicavit. Anno itaque Domini MoFootnote 192 LXVIo <Guillelmus dux> in regem ab omnibus tam Normannorum quam Anglorum est electus et sacro oleo ab episcopis regni delibutusFootnote 193 atque regali diademate coronatus. Locus vero ille in quo bellum fuit usque hodie Bellum nuncupatur, in quo rex GuillelmusFootnote 194 cenobium in Sancte Trinitatis honore construxit. Et in Normanniam rediensFootnote 195 ecclesiam Sancte Marie in Gemetico dedicari fecit, et Roberto filio suo ducatum Normannie tradidit, et Angliam revertitur ibique plurimos qui in capite jeiunii fideles omnes regis occidere proposuerant debellavit.

Translation

[fol. 150r] Short [and] succinct chronicle of the dukes of Normandy.

[§1] The Daci pride themselves on being descended from Antenor. Hasting, leader of the Dacians, landed with his men in Francia and devastated it. Afterwards he journeyed to conquer Rome, and through a ruse by which he pretended to be dead seized the town of Lunx, known as Luna; and bragging that he had captured Rome, but discovering that the opposite was in fact the case, he burned it down, and returned to Francia, and made peace with the king of the Franks through the receiving of gifts. Meanwhile, the king of Dacia wanted to expel many of his [own] men from his realm. Rollo and Gurim, sons of a most powerful Dacian leader, who had acquired for himself almost all of Dacia, opposed this expulsion at the request of the aforementioned youths.Footnote 196 The king of Dacia marched against them, yet they achieved victory on this occasion. But the next day Gurim was deceitfully slain in battle, and Rollo was put to flight; this [same] Rollo landed on the island of Scanza with six ships and proceeded to the English after having been advised [to do so] in a dream.

[§2] The form of the advice was thus: “Rollo, rise up with speed and make haste to sail across the sea and go to the English. There you will hear how you will return to your own country as a savior, and will there enjoy perpetual peace, free from harm.” This dream was interpreted by a wise Christian man as follows:

[§3] “In due course, you will be purified by holy baptism, and you will become a most worthy Christian: and by wandering the uncertain world you will come to the Angles, and with them you will enjoy the peace of everlasting glory.”Footnote 197 And straightaway he subjugated certain Angles by his authority, and, [as] foretold earlier by the dream, [made] a treaty with Æthelstan, king of the English.Footnote 198 He arrived at Walcheren,Footnote 199 notwithstanding the perils of the sea, and devastated that land and Frisia, and imposed tribute. And he captured Rainer [Longneck],Footnote 200 and then let him go. And in the year 876 after the incarnation of the Lord, he went to Jumièges via the [River] Seine,Footnote 201 and in the church of St. Vedast he placed the body of St. Hameltrude on the altar and built a chapel in the name of the same saint in that place. He entered Rouen without difficulty through the gate of St. Martin after he had given assurances to its inhabitants, and he chose to settle in these parts.

[§4] He went to [Pont-de-l’]Arche,Footnote 202 thereafter occupied Meulan,Footnote 203 besieged Paris and captured Bayeux,Footnote 204 which he conquered, and accepted the daughter of Prince Berengar in marriage,Footnote 205 with whom he had [a son named] William.Footnote 206 He then returned to Paris, conquered it while sending some of his men to Évreux,Footnote 207 and returned to Paris.Footnote 208 Learning that Rollo had laid siege to Paris, the English rebelled against their king Æthelstan, who asked and received the help of Rollo, and gave Rollo half of the kingdom so he would subjugate the rebels; once these had been brought under the yoke by the aforesaid Rollo and were reconciled [with the king], half of the kingdom and the culprits [as hostages] were given to the same Rollo; but Rollo gave it [sic] back, asking only that he [the king] should not prohibit those who preferred to follow him. Agreeing to this, the king wanted to accompany him to France. Rollo, who had returned to France, refused this, however, and divided his army.

[§5] King CharlesFootnote 209 requested and obtained a truce with him [Rollo] by mediation of Franco, archbishop of Rouen,Footnote 210 which lasted for three months, at the end of which the Burgundians and the Franks resumed war against Rollo on the advice of Richard [duke of the Burgundians] and Ebalus [count of Poitou].Footnote 211 Rollo, meanwhile, mutilated France and devastated the lands as far as Clermont-[Ferrand] via Saint-Benoît,Footnote 212 which he spared from ruin. He devastated Étampes,Footnote 213 and en route back to Paris vanquished the rural population and besieged Chartres.Footnote 214 [fol. 150v] Here he fought a fierce battle with the Franks and Burgundians until a bishop joined the battle with a cross and arms, and Rollo withdrew from the army in order to avoid death. Ebalus, who had not taken part in the battle, pursued the army of the heathens to Mount Lèves,Footnote 215 but to no avail. Rollo seized and completely devastated the entire country. The Franks asked [their king] Charles to make peace with Rollo and give him his daughter, Gisla, as well as the land between the River Epte and the sea, which was done by intervention of Franco, archbishop of Rouen. And Rollo was received by Duke RobertFootnote 216 from the sacred font, a treaty first being made, by which he conceded Brittany until the aforementioned land would be cultivated, Flanders having been rejected as too boggy. Moreover, he [Rollo] did not want to kiss the king's foot, but [instead] instructed a soldier [to do so], who tipped the king on his back.Footnote 217 And thus Rollo was baptized in the year of the incarnation [of the Lord] 912 and christened Robert in the sacred font, and just as he had devastated [this] country for thirty-six years between his arrival and his baptism, having accepted baptism he [now] endowed churches, divided what was left over amongst his people, and afterwards took the aforementioned Gisla as his wife. He granted the people rights and everlasting laws, sanctioned and decreed by the will of their leaders. He subjugated the insurgent Bretons and forbade theft.

[§6] The legates of King Charles who, unbeknownst to Rollo, had been meeting [secretly] with his wife for some time, he had executed publicly by cutting their throats. When Robert, duke of the Franks, learned that the bonds of peace [between Rollo and King Charles] had been disrupted thus, he rose against King Charles and sent envoys to Robert, who previously had been known as Rollo of Rouen, saying he wanted to fight Charles and obtain the kingdom of the Franks for himself. Robert of Rouen responded to this that he [Duke Robert of the Franks] was too eager to ride out and act beyond the law, but nevertheless the aforementioned duke of the Franks rebelled against the king and had himself anointed king on 29 June. King Charles regained the kingdom before the end of the [same] year, however, and he killed the aforementioned duke. Yet Count Herbert [II of Vermandois]Footnote 218 captured Charles himself and detained him in the castle of Péronne until his death.Footnote 219 He [Charles] was succeeded by Ralph, son of Richard, duke of Burgundy,Footnote 220 and godson of the said Charles, and the wife of the said Charles fled to her father, the king of England, together with their son, Louis, because she was too scared by the hostility of Herbert and Hugh the Great,Footnote 221 son of the aforementioned Duke Robert of the Franks.

[§7] Following the death of his wife, Rollo returned to and reunited himself with Popa, by whom he had [previously] been given his son, William. Summoning the Normans and Bretons, he presented the said William to them, placed him in charge of them as their lord, and subjugated them to his son by [making them swear] an oath of fealty. From then on, he lived as an old man consumed by sin, and [eventually] abandoned his mortal shell in Christ.

[§8] After the death of Rollo, his and Popa's son, William, had been commended to the wealthy Count Botho for his education,Footnote 222 and he had wanted to become a monk at Jumièges, which he wished to promote in the most generous fashion. He subdued the Bretons who rebelled against him but retained their duke, Berengar,Footnote 223 as bound to him by his oath of fealty and service, and drove off Alan,Footnote 224 who went to England. This William accepted a wife,Footnote 225 and reconciled himself with Hugh the Great and Herbert [II of Vermandois].

[§9] After this, the perfidious Riulf rebelled against him,Footnote 226 whom he vanquished, along with his accomplices, at Pré-de-la-Bataille near Rouen.Footnote 227 And, returning from the battle, [fol. 151r] he had news of his son's birth, who was thus raised so that the Franks, Burgundians, Flemish, English, Danes and Irish obeyed him. He [Duke William] married his daughter [sic] to William of Poitou. Herbert gave his daughter, on the advice of Duke Hugh the Great, to William of Rouen as his wife. Æthelstan, king of England, sent legates with gifts to this same William, begging that Louis,Footnote 228 his nephew, and Æthelstan [sic],Footnote 229 son of the aforesaid Charles, king of France, might be recalled to the Frankish realm, and that he might receive Alan, [who had been] expelled from Brittany for [his] crimes. And immediately, on the advice of the aforesaid William, Duke Hugh the Great and Herbert, leader of the princes, with the approval of the bishops and the advice of the metropolitans, promptly recalled the aforesaid Louis and anointed him king for themselves, [to rule] over the people living in Francia and Burgundy. And for the love of King Æthelstan, William received Alan, who had returned with Louis.

[§10] But after five years had passed, the Franks began to rebel against Louis, who, beseeching Henry, king of the land beyond the Rhine,Footnote 230 [was told] that help could not be obtained except through William's mediation. With this, the aforesaid Louis stayed for a long time with William at Rouen, and this same William sent messengers to the aforesaid King Henry in order to procure peace; this [same] King Henry sent these messengers back, and with them Duke ConanFootnote 231 as a hostage to bring about peace, whom William did not want to retain, but took with him to a meeting with Louis, king of the Franks, in the district of Laon,Footnote 232 face to face with Hugh and Herbert, and there kings Henry and Louis joined in alliance, in Hugh and Herbert's presence but not, however, with their consent. And hearing that he had been given a son, namely by his wife, Gerberga, he [Louis] made William lift him from the holy font and call him Lothar.Footnote 233 Having done this, William, upon returning home, built the admirably-designed church at Jumièges, and asked Martin, abbot of that place:Footnote 234 “Why are there three orders of Christians in the church?” He declared that he wanted in every respect to become a monk at that place, and the Normans and Bretons submitted themselves through fealty to Richard,Footnote 235 his son. Afterwards, Arnulf, lord of Flanders,Footnote 236 seized the castle of Herluin,Footnote 237 which is called Montreuil;Footnote 238 this [same] Herluin at first asked for help from Duke Hugh, and, having been refused, obtained assistance from Duke William, through which he recovered the aforesaid castle.

[§11] Arnulf thus secured a peace of three months with William, [and] they came together at a meeting in which William was killed through betrayal and deceitfulness by Arnulf, in the year of the incarnation of the Lord 943, on 17 December, while King Louis held the kingdom of the Franks. With his death, the Bretons and Normans established Richard, his son, as duke. Hearing of William's death, [King] Louis came to Rouen and retained the boy Richard. He displeased the citizens [of Rouen], and they impeded [him], and he [Louis] then kept him [Richard] to be educated. And Louis pretended to want to capture ArrasFootnote 239 and to destroy Arnulf, but with Louis's counsellors blinded by gifts, he had mercy on the said Arnulf, and, on Arnulf's advice, he detained Richard. On hearing this, the Rouennais prayed for him in processions throughout Normandy, and then, through the diligence of Osmond, [the duke's] servant, [and] with the support of Bernard, count of Senlis,Footnote 240 and Duke Hugh [fol. 151v] the Great, he [Richard] was carried off.