In the fall of 1939, just five months following his return to the United States after nearly a decade-long self-imposed exile living abroad, Paul Robeson's voice became closely identified in the national imagination with Earl Robinson and John Latouche's popular cantata Ballad for Americans. The work's legendary CBS radio premiere occurred in the late afternoon on 5 November 1939 as the centerpiece of Norman Corwin's newly launched Pursuit of Happiness, a variety program designed to promote the liberal ideal of America as an inclusive and welcoming land of promise and opportunity. A significant Sunday afternoon for both radio and American musical modernism, the broadcast of Ballad for Americans provoked the greatest audience response since Orson Welles's apocalyptic War of the Worlds, which almost exactly a year prior unleashed a wave of panic and fear as millions of Americans momentarily believed the nation was about to be invaded by aliens. The contrast between the two broadcasts could not have been greater: whereas Welles's infamous radio program fed upon national fears of foreign bodies, Robinson's Ballad for Americans offered a decidedly more affirmative and inclusive experience of national belonging, one that generated a wave of patriotic sentiment. With Robeson singing the lead, backed by the amateur working-class American People's Chorus, the narrative of nation at the heart of Ballad for Americans spoke not to the nation's fears but to its unrealized ideals of “freedom and justice for all.”Footnote 1

FIGURE 1. Paul Robeson performing during CBS broadcast of Ballad for Americans, 5 November 1939. Courtesy of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Used by Permission.

Pursuit of Happiness had just begun broadcasting—the premiere of Ballad for Americans appeared in the fourth program—and concerns about the political tone of the program were especially high.Footnote 2 Doing his best to placate conservative officials at CBS, and perhaps attempting to mute the aural images of racial and class injustices in the work's narrative, Corwin scripted a reassuring introduction (read by Burgess Meredith) that emphasized the earnest, celebratory tone of the program: “Democracy is a good thing. It works. It may creak a bit, but it works.” Other key contributors to the premiere broadcast were Mark Warnow (of Your Hit Parade) who conducted Ralph Wilkinson's orchestral arrangement and the young composer/arranger Lyn Murray prepared the chorus. Inside the studio an audience of over six hundred people responded with nearly fifteen minutes of applause. The response from listeners outside the studio was even more impressive: enthusiastic callers jammed the switchboards at CBS for two hours, a public outpouring that continued in the days following as hundreds of letters streamed into the station.Footnote 3 Robeson repeated his radio performance on New Year's Day in 1940, generating an equally vociferous response. The premiere radio performance was soon followed by a Victor recording with the American People's Chorus, which sold more than 40,000 copies by the end of 1940 (Figure 2 shows an advertisement for the recording.Footnote 4) Ballad for Americans also did well for the Robbins Music Corporation: the sheet music sold 20,000 copies in the first year alone. And in the summer of 1940 Robeson featured Ballad for Americans in his celebrated cross-country concert tour and sang it at numerous Congress of Industrial Organizations [CIO] and Popular Front events.Footnote 5

FIGURE 2. Advertisement for recording of Ballad for Americans on Victor Records, published in Amsterdam News, n.d.

The success of Robeson's version of Ballad for Americans is all the more remarkable as it was one of the first rare opportunities in which an explicitly progressive African American voice was given access to the national airwaves in an “educational” program such as Pursuit of Happiness. “Robeson ‘Hot’ Over the Air” ran the headline in a review of the broadcast published simultaneously in the Pittsburgh Courier and New York's Amsterdam News:

In a direct departure from anything that has happened before, the Columbia Broadcasting System presented Paul Robeson, America's most famous singer of folk songs, as the star of its Sunday afternoon program, “Pursuit of Happiness,” leading the famous Lyn Murray Chorus of white and colored voices, so mixed for the occasion.Footnote 6

The sensational popular appeal of Robeson's performance inspired countless other professional and amateur renditions, and Ballad for Americans was sung by well-known singers from a variety of musical spheres. Immediately following the release of Robeson's Victor disc, Bing Crosby recorded Ballad for Americans in 1940 for Decca and his version sold nearly 20,000 copies.Footnote 7 Yet it was, and is, Robeson's version that remains most closely associated with the piece as well as its historical moment. In fact, Robeson collaborated with Robinson in shaping Ballad of Americans as we know it.Footnote 8 His voice critically mediated—and most powerfully articulated—not only the work's narrative of nation but also the diverse formal and stylistic sonic frames through which this narrative was sounded.Footnote 9

Robeson's performances of the Ballad for Americans during this period tell us a great deal about the cultural politics of the Popular Front's vision of a national-popular and social democratic “people's music.” As an official international left movement, the Popular Front coalition of Communists, socialists, and New Deal liberals united under the banner of anti-Fascism was relatively short-lived, lasting from 1935 to 1939, becoming a victim of the anti-Communist backlash in the wake of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. However, as Michael Denning's influential rereading of the culture and legacy of the Popular Front has now established, the radical political and social issues that animated this political coalition—anti-Fascism, antiracism, and the labor movement (industrial unionism and workers' rights)—critically shaped America's cultural and political landscape throughout the decade of the 1930s, well into the war years, and beyond. Denning's account vividly underscores the overdetermined nature of issues of identity and “Americanness,” citizenship, and historical consciousness in the cultural politics of the period, a battleground symptomatically articulated through the prism and politics of race.Footnote 10 This struggle over the right to define and represent the US national body “became a locus for ideological battles over the trajectory of US history, the meaning of race, ethnicity, and region in the United States, and the relation between ethnic nationalism, Americanism, and internationalism.”Footnote 11

As the anonymous narrator of Ballad for Americans, Robeson's voice, as Denning remarks, was framed literally as the locus of such ideological battles.Footnote 12 The work's central narrative unfolds in a series of mini-musical tableaux that summon up four scenes marking moments of crisis in American history: the Revolutionary War, westward expansion, emancipation, and the Industrial Revolution. This musical-historical pageant emerges through an eclectic fusion of musical rhetoric: sonic and textual tropes of patriotic anthems and hymns and the open modal accents of Americanist symphonic style join with the Eisleresque strains of the workers' chorus, militant marches, and the lyrical sounds and lilting rhythms of turn-of-the-century popular song stylizations. Other stylistic allusions to popular music summon the melodramatic orchestral gestures suggestive of radio-drama background music and the nostalgic, tuneful melodies and stagy vernacularisms reminiscent of Broadway folk musicals. The eclecticism of this musical fabric is counterbalanced, however, by the continuous sonic presence of Robeson's voice. In addition to narrating the four historical scenes, Robeson's voice plays the role of a collective national conscious personified, the identity of which is kept hidden from the voices of “the people.” Rather, in between each tableau, Robeson ignores the chorus's increasingly strident demands to know who “he is,” instead rhetorically repeating the question “And you know who I am?” Set to an expansive melodic contour, this line became a kind of popular motto for the work as a whole; it positions the activist-singer's voice with its unembellished yet sweeping delivery and deep, resonating vocal timbre as the voice of the nation. Such a proposition reverberates—as does Robeson's voice itself—with complex racialized significations.

Proclaiming Ballad for Americans the “unofficial anthem” of the Popular Front social movement, Denning argues that the folk cantata emblematizes the “unstable” but progressive “pan-ethnic Americanism” that animated the cultural work of the Popular Front, a “paradoxical synthesis of. . . pride in ethnic heritage and identity combined with an assertive Americanism and a popular internationalism.”Footnote 13 Robeson's version of Ballad for Americans also signals the centrality of African American culture in constructions of pan-ethnic Americanism, thus reflecting the ways in which racial definitions have been—and continue to be—integral to discourses around national belonging.

The popular embrace of Robeson's embodiment of this vision becomes all the more profound when considered in light of his outright political ostracism in the postwar/Cold War period. “To denounce Robeson,” as Kate A. Baldwin has recently put it, “became tantamount to proving one's patriotism.”Footnote 14 Practically overnight, Ballad for Americans went from being a favorite anthem of school choral groups (even Boy Scouts) to obscurity; it was “literally ripped from many public school songbooks.”Footnote 15 From the other side of the political divide, postwar critics disavowed Ballad for Americans as aesthetically and politically bland, middlebrow, populist kitsch.

Denning's rereading of Ballad for Americans productively defends the work against its caricatured Cold War image; however, his recuperation focuses primarily on an analysis of the text in the work's final passages and, to a lesser extent, on the racial-symbolic currency of Robeson's voice.Footnote 16 One of the aims of this essay is to extend Denning's arguments to address musical details of form, genre, style, and performance. My project is also oriented theoretically by the work of Baldwin and Hazel Carby, whose insights into Robeson's post-1939 performances suggest additional interpretive frameworks for rehearing Robeson's Ballad for Americans in the context of his larger quest to join his musical and political voices. Both studies emphasize the internationalist contexts of Robeson's work as a singer-activist; these contexts provide fresh perspectives for reevaluating issues of race and cultural politics surrounding Robeson's Ballad for Americans.Footnote 17

During this period, Robeson transformed both the content and context of his performances to underscore an anticolonialist, global understanding of black liberation struggles. As Carby observes, his work “took a decidedly international, collectivist turn. . . . Rejecting his previous location as representative American Negro, he embraced an openly political aesthetics.”Footnote 18 Yet Robeson's persona and sound as a folksinger—a “people's artist”—and his political identity and struggles as a radical black intellectual interacted and collided with the cultural-racial politics of “people's music” and with Popular Front discourses on the folk.Footnote 19 At the end of the 1920s, for example, Robeson's interpretations of black folk sound stood as the benchmark of racial authenticity; by the late 1930s, however, the lines of authenticity had shifted considerably and Robeson's vocal style and concert repertoire did not fit comfortably—if at all—the criteria of authenticity based around southern rural folk stylistics that were being promoted in the urban folk song movement.Footnote 20 At the same time, his voice had little in common with urban black vernacular genres.

“Well, I'm the everybody who's nobody, I'm the nobody who's everybody”

The Popular Front period witnessed a significant reconceptualization in critical debates about what and who constituted the “folk.” This discursive shift had already begun in the early 1930s as the politicization of bourgeois intellectuals and artists gave rise to efforts to create expressive forms that could appeal to the urban working-class masses as well as foster a sense of collective proletarian consciousness among and between the rural and urban working class. With the rise of the Popular Front social movement, the terms of these debates modulated: reflecting the less militant, coalition-based politics of the Popular Front, political rhetoric shifted from the “worker” to the “people.”Footnote 21 This change reflected more than a strategic need to accommodate liberal, non-Communist factions of the left and New Deal; rather, it signaled a profound realignment in debates about the relationship between aesthetics and politics, specifically the struggle to reconcile Marxism with modernist aesthetics. To put the matter schematically, after 1935 the Popular Front strategy allowed artists to embrace a wide range of vernacular and popular sources, although the specific aesthetic and political values of this “populist” or “functional” orientation generated intense debates.Footnote 22

Such debates were nowhere more evident than among the young modernist composers, Robinson among them, associated with the Communist-inspired New York Composers' Collective. As is well known, the Collective included Ruth Crawford, Aaron Copland, Marc Blitzstein, Wallingford Riegger, Elie Siegmeister, Alex North, and Lan Adomian. Formed in 1932 by Charles Seeger, Henry Cowell, and Jacob Schaefer, the Collective's founding mission was to produce and disseminate a collection of mass songs.Footnote 23 To this end, the Collective sought to develop a modernist mass-song style which, in the image of agitprop art, would transform the ears of the proletariat away from “bourgeois” tonality and other forms of music that it viewed as irretrievably tied to capitalism, a category that included popular music and folk music. However, by 1935, many composers in the Collective reversed their stance towards folk song and vernacular music (although for some, urban popular music and Tin Pan Alley remained off-limits). This shift can be seen in the Collective's 2nd Workers' Song Book (1935). Robinson, for example, contributed one song, “Death House Blues” (“a contribution to the cause of the Scottsboro Boys”), with adapted verses from Lawrence Gellert's influential collection of African American work songs (published in 1936 as Negro Songs of Protest).Footnote 24

Robinson's Scottsboro-theme song signaled the reconceptulization of folk song and American vernacular music as “people's music.”Footnote 25 It also registers the mediating role of race in general and the centrality of blackness in many visions of “people's music” and “people's culture” in the Popular Front social movement. Extending an idea given its most powerful and famous articulation in 1902 by W. E. B. Du Bois in Souls of Black Folk and continued through the Harlem Renaissance, Popular Front and Communist Party cultural workers embraced African American culture and folk forms as the bearer of political freedom. Younger “guard” critics in particular promoted the idea that not only African American literature and theater but also black popular music and professional sports embodied the ideals of a democratic and progressive Americanism.Footnote 26 This shift was perhaps most dramatically reflected in the cultural activities of the Communist Party USA. After 1935, for example, the Communist Party softened considerably its hard-line prohibition against jazz and swing music and its official censuring of “bourgeois” black cultural nationalism.Footnote 27 Many young party members enthusiastically embraced the syncretic spirit of Popular Front culture, hailing jazz as “the music of the American proletariat.”Footnote 28

The varied aesthetic-political alliances in Popular Front musical life were nowhere more evident than in the diversity of forms produced under the category of folk, from the collecting of field recordings and the publication of folk song anthologies, to the creation of a multitude of popular modernist works in the arena of musical theater, film, and concert music. In New York, as in other metropolitan centers, staged performances of folk, folk-styled, and vernacular musics were regularly featured, often in combination, in a variety of performance spaces, from relatively informal contexts of political rallies, WPA-sponsored left-wing theater such as the TAC (Theater Arts Committee) cabaret, and nightclubs (such as Café Society) to more ambitious programs on the stages of concert halls (Carnegie Hall and Town Hall) and Broadway. Though at times more populist than popular, such performances constituted a prime medium through which the sound and image of a national musical vernacular—a “people's music”—was represented to and for a significant cross-section of the urban public.Footnote 29

The concert programs of two Town Hall performances of “people's music” during the 1941–42 season can give a sense of both the diverse field of folk and folk-styled sounds, as well as the political and social contexts in which they were framed. Figure 3 reproduces a program for “Songs for Democracy,” a gala “testimonial” concert for Earl Robinson held at Town Hall in support of the completion of his “people's opera,” The People, Yes, which was based on Carl Sandburg's famous text. Sponsored by Robeson and Marc Blitzstein and presented under the auspices of the New Theatre League on 29 November 1941, the concert program offered an impressive multicultural mix of national and international folk voices and styles. Although Robinson's music was the ostensible highlight of the program (which included excerpts from his aforementioned “people's opera,” his labor song “Joe Hill,” and Ballad for Americans), the first half of the program also featured topical songs by Chinese singer Liu Laing-mo, bluesmen Leadbelly and Josh White, the Almanac Singers, and baritone Mordecai Baumann. The second half included a number by Andy Razaf and Eubie Blake (“We Are Americans Too”).

Figure 3. Program for “Songs for Democracy,” a gala testimonial concert for Earl Robinson held at Town Hall, New York, 29 November 1941.

A concert held on 26 June 1942, “Folk Songs on the Firing Line,” presented a similar mix of performers and repertoire. Produced under the auspices of the Negro Publication Society of America and co-sponsored by Earl Robinson and Richard Wright, the concert program mixed nineteenth-century novelty songs such as “Hinky-Dinky Parley Voo” and the radical Civil War song “John Brown's Body” with work songs such as “Pick a Bale of Cotton” and “John Henry.” The latter were performed by an all-star folk group that included Woody Guthrie, Agnes Cunningham, Leadbelly, and Pete Seeger (the Almanac Singers), along with bluesmen Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Like the “Songs for Democracy” program, the repertoire for “Folk Songs on the Firing Line” went beyond national borders: again representing the “valiant Chinese” was the battle song “Chee Lai” sung (as before) by Liu Liang-mo, and Herman Ivarson performed a song celebrating the Norwegian underground. The final set featured Art Hodes's New Swing Band, which, according to a critic in the New York Times, “beat out a few sizzlers in celebration of the fact that Nazis don't like swing.”Footnote 30

The mix of the national and international in these programs owe much to Robeson's own innovative concert programs; indeed, his performances participated in shaping musical and political definitions of folk song for urban publics. Another important influence, especially for creating a work like Ballad for Americans, came via the more informal stages of left-wing musical-theater productions, most notably TAC cabaret revues, which often featured songs that freely appropriated patriotic musical and rhetorical symbols to promote progressive political and social ideals. Ballad for Americans, as is well known, had a prior existence: under the title “Ballad for Uncle Sam” the work originated (in a somewhat truncated version) as a finale for one of the WPA Federal Theatre Project's most elaborate and controversial productions, the 1938 musical revue Sing for Your Supper (the first production in a popular revue format presented by the FTP). It was during this production that Earl Robinson and John Latouche first met, as both composer and lyricist submitted songs and sketches for the revue. In its early version, the main character/narrator was Uncle Sam (sung by Gordon Clarke), who appears in the skit as a kind of showbiz impresario; the chorus enacted the part of unseen customers who question Uncle Sam from offstage, out of which follows the “musical history of the United States.”Footnote 31 After the show's premature demise in the aftermath of the WPA's federal de-funding, Corwin invited Robinson and Latouche to produce their “musical history of the United States” for his radio show, and he renamed the piece Ballad for Americans.Footnote 32

Robinson and Latouche called Ballad for Americans a “musical history of the United States,” a significantly ambiguous description insofar as it may imply a narrative history of the nation set to music and a history of the nation's music. Both formats—presentations of the nation's musical history in the form of variety shows and historical pageants of the nation set to a continuous musical score—were enormously popular during the Popular Front.Footnote 33 In practice, there was considerable overlap between variety show histories of American music and those that used music as a backdrop to present a narrative of American history. Although Ballad for Americans obviously matches the latter historical pageant format, it also uses generic devices associated with the former. In the Emancipation tableau, for example, the chorus hums the refrain “Let my people go” from the spiritual “Go Down Moses.” Other scenes conjure generic stylistic codes associated with particular periods: the passage narrating westward expansion features a kind of jazzy cowboy song style worthy of Roy Rogers, replete with pseudo—banjo/wagon wheel orchestral accents. Similarly, the Industrial Revolution/“machine age” section invokes the dissonant sonorities and angular syncopations associated with Jazz Age modernist musical paeans to skyscrapers and machines.

The final section ushers in a series of question-and-answer passages between Robeson and the chorus in which muted references to the labor movement and to political and racial violence mix with affirmation of the nation's democratic ideals. As with the piece as a whole, the dialogue between Robeson and the chorus during this section mixes sung and spoken passages. The vernacular speech accents of the spoken voices along with a liberal use of period slang communicate an aural image of “the people” as plainspoken, multiracial/ethnic working-class folk. “Who are you mister?” shout several voices from the chorus, their question ringing out in the demanding tones of a street crowd; “I'm the everybody who's nobody. I'm the nobody who's everybody,” recites Robeson. A succession of similar exchanges ensues, and each time Robeson defers the demands to reveal himself, offering instead three epic catalogues of identity, first as defined by occupation, then by race/ethnicity and religion.

In addition to functioning as a space for conjuring the nation's musical and linguistic vernacular, the leader-chorus question-and-answer dialogue also serves as a formal device: namely, it provides a unifying structural frame for the work's episodic, revue-like narrative format. In the final section, for example, the aforementioned dialogue between Robeson and the chorus acts as a transitional device, specifically signaling the narrative shift from the “machine age” section to the final sequence. This sense of narrative shift is, however, initiated by the passage that directly precedes the spoken dialogue in which Robeson sings a thematically important refrain that recurs in various guises throughout the work: “Still nobody who was anybody believed it. Everybody who was anybody they doubted it.” When Robeson sings this refrain after the Revolutionary War and Emancipation scenes it implies that Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln are also the “nobodies” (or at least in solidarity with the “nobodies”), as are Betsy Ross, Chiam Solomon, and Crispus Attucks, all of whom are named in the list. The privileged and corrupt “anybodies” are nowhere directly named and appear only through references to their cynicism, avarice, and acts of racial violence and class exclusion. As Robert Cantwell observes, this sets “the revolutionary dream against the class-based language of status and celebrity on the one hand and, on the other, of urban anonymity, cultural invisibility, and immigrant powerlessness.”Footnote 34

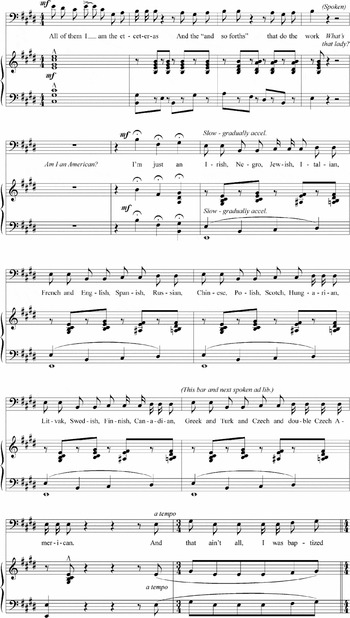

Example 2 reproduces this passage as it appears in the published piano-vocal score; on the Victor recording, however, upon which my analysis is based, Robeson sings the work transposed down a fourth from E-flat to B-flat (a revision I address later) and thus begins the refrain in B minor rather than E minor. Comprised of two-measure phrases, the second of which is a variant of the first, this central refrain draws on many elements associated with the mass-song style as developed by the New York Composers' Collective in the mid-1930s. These elements include a highly syllabic setting to convey the didactic intent of the words, a homophonic texture, and a militant four-square march-like accompaniment with open fifths and octaves in the bass.Footnote 35

A fermata at the word “And” takes us into a contesting thematic and tonal area that moves through sequentially rising one-measure phrases. With a dramatic urgency and lyricism hitherto unheard in the work, Robeson almost seems to step out of his role as the narrator to speak as Robeson the activist and artist: “And they are doubting still, And I guess they always will; But who cares what they say when I am on my way,” The final phrase, “when I am on my way,” is set to the “And You Know Who I Am” motive (shown in Example 1), a descending minor triad that spans a minor sixth followed by a lilting ascending and descending fourth. The piano-vocal score clearly suggests a dominant 13th chord here; on the recording, however, the A in the inner voice is almost inaudible, creating more the sound of a modal progression in C-sharp minor from i-v6. This difference imparts an Aeolian modal quality to this phrase, giving it a kind of archaic, folklike sound.

Example 1. Earl Robinson, Ballad for Americans: A Narrative Solo for Baritone; text by John Latouche, piano-vocal score arranged by Domenico Savino (New York: Robbins Music, 1940), m. 53. (mp3 available at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/sam2_1-barg-ex1). mp3 excerpted from Ballad for Americans, music by Earl Robinson and words by John Latouche, performed by Paul Robeson with the American People's Chorus and the Victor Symphony Orchestra, Nathaniel Shilkret, cond., Victor Records 26516, 1940. Reissued on Songs for Free Men, Pearl 9264, 1997.

Example 2. Robinson, Ballad for Americans, mm. 161–68. (mp3 available at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/sam2_1-barg-ex2). mp3 excerpted from Ballad for Americans, music by Earl Robinson and words by John Latouche, performed by Paul Robeson with the American People's Chorus and the Victor Symphony Orchestra, Nathaniel Shilkret, cond., Victor Records 26516, 1940. Reissued on Songs for Free Men, Pearl 9264, 1997.

Robeson's introspective moment dissolves quickly: muted strings play a suspended minor mode chord that leads directly into the spoken question-and-answer passage, itself a prelude to the three catalogue sections. Robinson animates the catalogue choruses with nostalgic evocations of turn-of-the-century American popular sound, a prominent feature in Popular Front–inspired musical Americana. With a legato texture and added sixth tonic-dominant chords, the first catalogue section, occupation, pays tribute to the laboring of “engineer, musician, street cleaner, carpenter, teacher, farmer, office clerk, mechanic, housewife, factory worker, stenographer, beauty specialist, bartender, truck driver, seamstress, ditch digger.” The paired racial/ethnic and religion catalogues, by contrast, are set to the infectious sing-along rhythms of a stylized square dance, a musical fabric that calls to mind the syntax of late 1930s and early 1940s folk ballets and folk film musical production numbers.Footnote 36 Together, the three catalogue sections overtly embrace a vision of America as an inclusive class, racial, and gendered body politic, an image that stands out against the emphasis on Anglo-Americana in canonical concert works, ballets, and Broadway musicals from this same period.

Despite its sunny tone, Ballad for Americans is peppered with bits of distinctly unsentimental, hard-boiled commentary that implicitly underline race and class oppression. At the finish of the first occupation catalogue, for example, Robeson sings the line “All of them I am the etceteras and the so forths that do the work” with the latter phrase “that do the work” set off by a short staccato sotto voce cadence. Two voices in the chorus respond with xenophobic overtones: “What are you trying to give us mister? Are you an American?” Robeson immediately launches into the second catalogue with a folksy three-note rubato lead-in on the words “Well I'm just an. . .” that continues slowly in the subsequent 4/4 bar with “Irish, Negro, Jewish, Italian,” then gradually accelerates with “French and English, Spanish, Russian,” then builds to a frenetic clip for “Chinese, Polish, Scotch, Hungarian, Litvak, Swedish, Finnish, Canadian, Greek and Turk,” ending with the pun-filled phrase “Czech and double Czech American” (shown in Example 3). The slow tempo of the opening combined with Robeson's emphatic delivery of the first bar draws our attention to the enunciation of the first four identities as if to displace the racial power of the old-stock, ruling-class Anglo-Saxon identities that directly follow. (Interestingly, “German” is not included.) Both the choice and ordering of identities also highlights a symptomatic ambiguity between the categories of race and ethnicity (and in the case of “Jewish,” religion as well).

Example 3. Robinson, Ballad for Americans, mm. 189–201. (mp3 available at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/sam2_1-barg-ex3). mp3 excerpted from Ballad for Americans, music by Earl Robinson and words by John Latouche, performed by Paul Robeson with the American People's Chorus and the Victor Symphony Orchestra, Nathaniel Shilkret, cond., Victor Records 26516, 1940. Reissued on Songs for Free Men, Pearl 9264, 1997.

On the Victor recording the chorus punctuates the closing moment of this catalogue with a big collective “gee-whiz” whistle (the published piano-vocal score indicates that the closing bars be “spoken ad lib”), a gesture that instantly conveys the “people's” wide-eyed amazement at the narrator's seemingly infinite pan-ethnic national body with a theatrical self-reflexive wink. Most famously associated with the writer Louis Adamic, this articulation of American universalism as a “nation of all nations” and the brand of liberal civic nationalism it inspired was of a piece with the then newly fashioned concept of “ethnicity.” By extending the promise of Americanism (read whiteness) to include the stories and identities of non-Anglo-Saxon immigrants, “ethnicity” mediated between whiteness and color, thus eliding the “race problem” or, in any case, segregating histories of racial violence and injustice.Footnote 37

The Adamic ideal promoted in the lyric here, however, is not simply an uncomplicated vision of pluralism and inclusivity. As Denning points out, the lyric can be read as a dramatizing the impossibility of containing “the people” in all their variety. Latouche's lyrics, he writes, “are precisely about the difficulty of representing the people.”Footnote 38 Robinson's setting of the catalogue section underlines this sense of uncontainable multiplicity through a diction-busting rhythmic/metrical acceleration. Robeson amplifies this effect as he audibly struggles to “name” the “whole.”

Yet even here, the racial unconscious of American universalism makes an appearance in the final moment with the double-entendre “Czech and double Czech American.” In her pioneering social history of radio and race during the war years, Barbara Savage notes that “Czech and double Czech American” would have been instantly recognized by listeners in the 1930s as a phrase made popular by the “blackface” radio show Amos 'n' Andy.Footnote 39 The reference here, audibly marked by Robeson, in many ways epitomizes contradictions of race and nation that his performances of Ballad for Americans make manifest. Ending this ode to a pan-ethnic America with an allusion to blackface minstrelsy ironically conjures a founding racial dialectic in the historical process of Americanization.Footnote 40 For it suggests, as Nikhil Singh has observed, that “at its most generic, US national identity still depended on anti-black tropes.”Footnote 41 This moment also signals the profoundly problematic racial politics of New Deal romanticism that tended to embrace all expressive traditions of the vernacular as “people's culture,” a practice that would soon be publicly contested by black intellectuals, writers, and artists, Robeson among them. In 1942, for example, Robeson announced that he would never again sing “popular folks songs or ballads that picture the Negro as ignorant or crude. . . .”Footnote 42

A different but related racialized moment occurs at the end of the third and final catalogue, which is based on religious affiliation. After a brief two-beat pause, Robeson begins, “And that ain't all, I was baptized Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, Lutheran, Atheist, Roman Catholic, Orthodox Jewish, Presbyterian,” etc. Unlike the previous catalogue, this one is sung a tempo and ends simply with a spoken comment “And lots more!” In the Victor recording (and presumably in live performance) the chorus responds to Robeson's claim to embodying multiple religious identities with the ad-libbed spoken line “You sure are big!” It is a significant moment in the piece insofar as it constitutes a pointed reference to Robeson, marking not only his large physical stature but the racialized discourse that had long framed representations of Robeson's body.Footnote 43 (In his program notes for the Victor album and in his autobiography, Robinson repeatedly calls Robeson by his popular nickname “Big Paul.”)

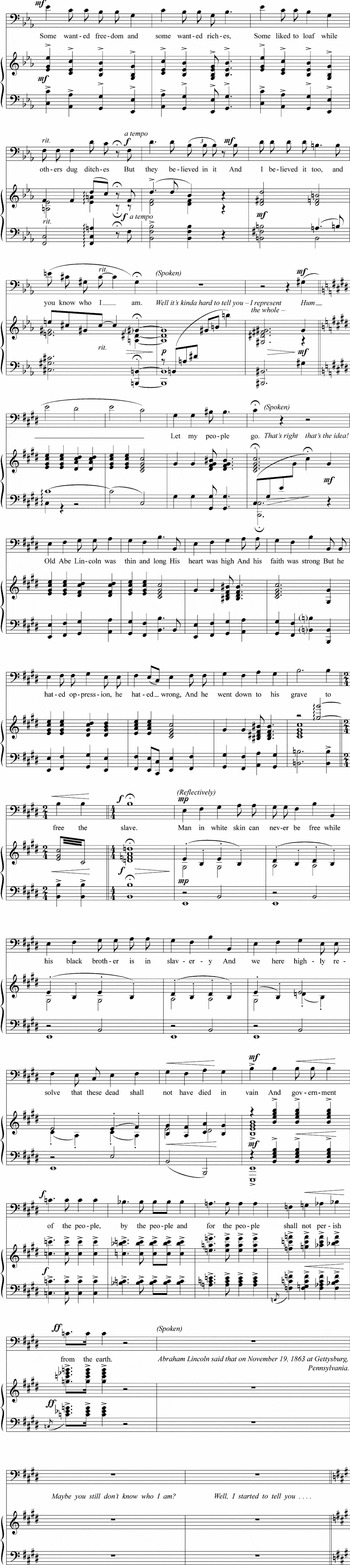

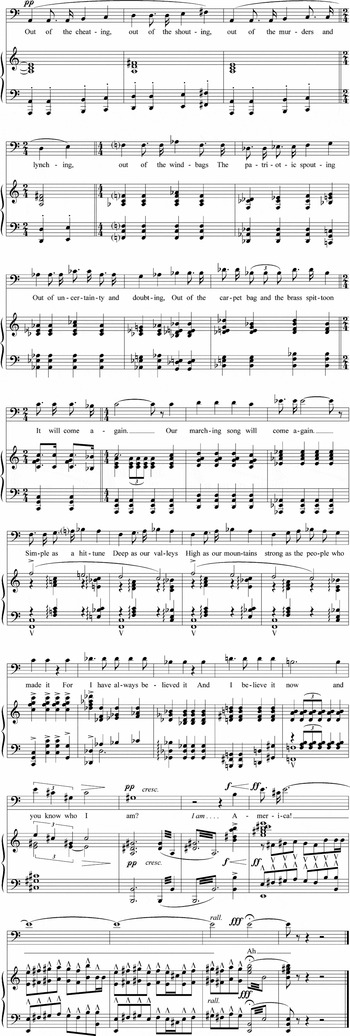

Although in the final passage Robeson triumphantly reveals his identity as the nation itself (“I am. . . America!”), Ballad for Americans ultimately leaves unresolved the history of conflict and crisis it narrates, deferring its vision of universal democracy and justice to a moment yet to come.Footnote 44 The sense of “a dream deferred” at the close of the work has formal analogues in the work itself, most obvious of which is the narrative conflict in the piece between, on the one hand, affirmative images of national inclusiveness and the at times almost painfully earnest (bordering on camp) schoolroom patriotic rhetoric and, on the other, sober passages that allude to racial injustice, violence, rapacious capitalism, and jingoism. The moment of adopting the Constitution, for instance, is juxtaposed against a passage marking the racial labor and inequalities marshaled to build the nation. “Some liked to loaf while other dug ditches,” Robeson sings, the final “dug ditches” emphasized with a brief ritardando and sweeping dominant seventh chord. After this, the narrative is suddenly suspended: subdued strings play a rising dissonant arpeggio out of which emerges the wordless refrain “Let My People Go,” hummed by the chorus in hushed, barely audible voices, a powerful prelude to the Emancipation scene (shown in Example 4). A fighting four-square march breaks the prayerful moment in which “Old Abe Lincoln” is remembered as a kind of abolitionist martyr: “[H]e hated oppression, he hated wrong, And he went down to his grave to free the slave.” As can be seen in Example 4, the setting of the phrase “down to his grave” moves emphatically upwards with stirring tremolos, climaxing on the word “slave,” which is harmonized by an unstable half-diminished seventh chord. Marked forte and set to a held whole note (marked with a fermata), no other word in the entire work receives such a dramatic—and unresolved—emphasis. The historical scene grinds to a halt. Out of the reverberant sonic traces summoning the figure of the slave comes a sparsely scored, major-key passage (marked Reflectively) that moves atop a drone on E. Robeson exhorts in a kind of defiant whisper: “Man in white skin can never be free while his black brother is in slavery.” After this, below phrases picked from Lincoln's Gettysburg address, the texture builds to a stirring fanfare. The fanfare culminates in an unexpected and dramatic tonal shift to C major (the flat-VI in E) at the words “Of the people,” after which we immediately hear jarring, chromatically inflected voice-leading supporting the lines “by the people and for the people shall not perish from the earth,” performed by Robeson in an almost shouting voice.

Example 4. Robinson, Ballad for Americans, mm. 107–45. (mp3 available at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/sam2_1-barg-ex4). mp3 excerpted from Ballad for Americans, music by Earl Robinson and words by John Latouche, performed by Paul Robeson with the American People's Chorus and the Victor Symphony Orchestra, Nathaniel Shilkret, cond., Victor Records 26516, 1940. Reissued on Songs for Free Men, Pearl 9264, 1997.

The dramatic urgency called forth in the Emancipation tableau does not return until the penultimate passage of the work—arguably its most radical moment. Coming after the three catalogue sections, it is a sobering and poignant return that links past and present injustices and, as such, suggests that the central “march” of Ballad for Americans message is directed towards the causes of racial equality and justice. (Indeed, the first iteration of the march material, which is heard in the opening Revolutionary War scene, emphasizes the Constitution's “mighty fine” words on the subject of equality: “That all men are created equal, etc.”) As shown in Example 5, the penultimate passage takes the form of a fist-clenched dissonance tinged march, one presaged by the earlier slow march sections.

Example 5. Robinson, Ballad for Americans, mm. 223–52. (mp3 available at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/sam2_1-barg-ex5). mp3 excerpted from Ballad for Americans, music by Earl Robinson and words by John Latouche, performed by Paul Robeson with the American People's Chorus and the Victor Symphony Orchestra, Nathaniel Shilkret, cond., Victor Records 26516, 1940. Reissued on Songs for Free Men, Pearl 9264, 1997.

Beginning quietly at the bottom of Robeson's vocal range (A minor in the score; transposed down a fourth to E minor on the Victor recording), the march steadily grows louder as Robeson's voice climbs, giving the sense of an approaching mass or street crowd.Footnote 45 He sings:

The intensity of this passage, its visceral sense of outrage and solidarity is abruptly interrupted: the music lurches for four measures into expansive lyricism redolent of the Broadway stage to set the phrase describing “our marching song” as “Simple as a hit tune/Deep as our valleys/High as our mountains, strong as the people who made it.” Another rapid shift occurs at the end of this passage; the return of the rhetoric of “the people” seems to precipitate a return to the march texture, although here marked by a triumphant rather than dissonant tinge (“For I have always believed it, And I believe it now”). The contrast between militant march and Broadway musical in this final section is a kind of amplified microcosm of sonic and narrative disjunctions that characterizes the work as a whole. Such disjunctions arise both in the work's rapid shifts in stylistic codes and rhetoric (which occur both within and between sections) and in the way the work's Enlightenment teleology of progress—the four historical tableaux—is continually interrupted by increasingly abrupt episodic treatment.

It bears repeating that the use of the episodic, revue-like format in Ballad for Americans points to the work's origins in the milieu of left-wing theater. Musical and textual traces of the work's radical aesthetic ancestry appear throughout. Probably the most explicit of such traces is Robinson's aforementioned adaptation of elements of the mass-song style and workers' chorus associated with the New York Composers' Collective. Robinson's decision to cast Ballad for Americans in the form of a cantata also shows the influence of radical aesthetics, in particular Eisler's theories on form and politics (Robinson studied with Eisler in New York briefly in 1935–36). That is, Eisler advocated the appropriation of older forms such as the oratorio as means to replace individual bourgeois identification of tonal harmony with collective communication.

Of course, Eisler would probably have disavowed Ballad for American's fusion of the principals of mass-song style to American popular sounds. Yet as Denning convincingly argues, such popular modernist fusions were—next to the popular sounds of swing and jazz—what the people, that is, the vast majority of the urban working class, enjoyed as “people's music.”Footnote 46 This is probably Denning's most provocative revisionist move with respect to previous musical-historical accounts of the Popular Front in which the mantle of “people's music” is conventionally bequeathed solely to folk song. In fact, a wide range of musical scenes appropriated the liberal rhetoric of “people's music” to promote their aesthetic agendas. As has been amply documented elsewhere, at one time or another during the late 1930s and early 1940s the category “people's music” was claimed, variously, by the urban folk song movement for non-popular folk song, by jazz revivalists for (also non-popular) pre-swing, New Orleans improvisatory-based styles, and by advocates of modern jazz styles and swing. The Popular Front idea of “people's music” was also invoked by composers in their quest to forge an Americanist concert music and by concert promoters and conductors hired by the FMP (Federal Music Project) to bring concert music to the masses.Footnote 47

What all these various uses of the term “people's music” shared was a bid to represent the nation's vernacular. In general, the brand of rural-based folk song embraced in the urban folk song movement as an alternative to mass-mediated, popular music never found a large working-class audience—this despite the government-supported efforts of Charles Seeger and Alan Lomax to inculcate “authentic” American folk consciousness in the “people.”Footnote 48 It is also true that even the most representative works of Popular Front vernacular modernism (Ballad for Americans included) would not have the kind of impact on postwar developments in popular music that the urban folk song revival would have, a fact that undoubtedly explains why so many historical narratives of the period privilege the urban folk song movement and, by extension, Robeson's involvement with this milieu.Footnote 49

Indeed, Robeson's involvement with folk song during the Popular Front period has usually been articulated to narratives of the urban folk song movement that find their center of historical gravity in the movement's canonical figures, most famously the circle of folk artists around the two famous father-son pairs—the Lomaxes (John and Alan) and Seegers (Charles and Pete), a group that includes Huddie Leadbetter (Leadbelly), Woody Guthrie, and the Almanac Singers.Footnote 50 Positioning Robeson as part of the story of the urban folk song movement, however, has resulted in obscuring the multiplicity of discourses around notions of black folk expressivity and folk discourse more generally. Moreover, in placing Robeson within a largely white critical and intellectual discursive sphere, such narratives elide not only African American intellectual history and perspectives but ignore Robeson's centrality in black Atlantic history. Attending to black Atlantic history and perspectives underscores how discourses on the folk addressed different senses of cultural history, racial subjectivity, and nation in black intellectual and artistic production. Most pertinent to this discussion is to register the links between Robeson and what Penny Von Eschen has dubbed the “black popular front” as a means to understand the global implications of a work like Ballad for Americans for Robeson and, more generally, to situate his performances of the piece within the larger context of his quest to merge his political and musical identities.Footnote 51

“Am I an American?”

When he returned to New York in the fall of 1939, Robeson was an international celebrity: in addition to his successes on the London stage playing Othello and his work in film, his concert recitals of spirituals had crucially shaped international perceptions of African American folk sound.Footnote 52 Throughout the Popular Front period, Robeson performed concerts in support of progressive Popular Front causes as well as, more generally, to benefit organizations on the left; and he participated in numerous theater groups, forums, and cultural organizations sponsored by the Harlem Communist Party.Footnote 53

In his first published interview with Julia Dorn in TAC Magazine immediately following his return to the United States in 1939, Robeson proclaimed: “When I sing, ‘let my people go,’ [from “Go Down Moses”], I can feel sympathetic vibrations from my audience, whatever its nationality. It is no longer just a Negro song—it is a symbol of those seeking freedom from the dungeons of fascism in Europe to-day.”Footnote 54 Robeson's framing of the spiritual as an international symbol of freedom and anti-Fascism at once reconstructs a history for the spiritual and disarticulates his voice from long-standing aestheticized constructions of the genre that elided connections between culture and politics, art and activism.

Shortly before this interview, Robeson gave one of his first public performances at a symposium benefit for Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign on 29 June 1939. Titled “Spanish Culture in Exile” the event was mounted under the joint auspices of the Musicians' Committee to Aid Spanish Refugees and the Negro People's Committee to Aid Spanish Refugees. During the three-hour symposium, Robeson explained the “need for close, united action on the part of all people if freedom and liberty are to be safeguarded. . . . And so, I am coming home again to join the fight.” The evening culminated with Robeson performing a set of folk songs and work songs drawn from Spain, America, and the Soviet Union, all sung in their original languages.Footnote 55 Robeson's repertoire for this occasion reflected well his idea and practice of folk music. After 1935, his performances embodied his intertwined commitments to the universalism of folk expression and to black cultural and political nationalism through carefully planned programs that typically combined a core group of spirituals within an international repertoire that emphasized folk and protest songs.

From 1940 throughout the war period, Robeson sang Ballad for Americans in both intimate and public stages, giving it pride of place either directly before intermission or at the end. For recitals and informal spaces he performed it in a piano-vocal version with his longtime accompanist Lawrence Brown. The political and social implications of Robeson's programs inhered not only in the choice of material but, more importantly, in the ways they imagined, however romantically, how the “sympathetic vibrations” of folk song could sonically embody a collectivity and act as a force for social change.Footnote 56 In a brief but provocative discussion of his “folk-based performative praxis,” for example, Kate Baldwin argues that Robeson's performances constituted a type of “minority discourse” in which a “simultaneous emerging of the national and international” strategically refracted a collectivity to and for listeners, one based in the sonic internationalism of the songs themselves. Robeson's performances, Baldwin thus suggests, fostered a critical consciousness in listeners that revealed “as points of commonality the political exclusions created by slavery, segregation, and imperialism.”Footnote 57

Just as Robeson designed his concert programs to create sonic-critical consciousness, his “folk-based praxis” also came to bear in his revisions to Robinson's score. Specifically, Robinson composed Ballad for Americans in the key of E-flat major but Robeson insisted that Robinson transpose it down a perfect fourth (to B-flat) so he could sing it in the bass-baritone register. Although Robeson possessed the vocal ability to sing the piece in its original key, he refused to do so, believing that the vocal demands of the higher tessitura would require him to “sing-out” in the “artificial” tones of a classically trained baritone—not a folksinger. Indeed, Robeson drove the point home by explaining to Robinson that when he sang in Russia they transposed “the already low arias from Boris Godunov down to his key. ‘Seems like you might be able to do the same for me, huh?’”Footnote 58 What Robeson wanted was to deliver the text in an assertive, informal conversational singing voice, an effect he could best achieve in the lower areas of his range where he could sing most comfortably and where his voice could take on a much more resonant, booming quality.

Moreover, I would argue that Robeson's insistence over the issue of pitch was also a means of claiming authorship due to his awareness of the performative effect of his voice. By singing the work in and through the voice he utilized in his performances of folk songs and spirituals, Robeson both heightened the narrative's antiracist themes and retuned its vernacular forms and accents towards a radical international (black) imaginary.Footnote 59 As Von Eschen has shown, the radicalization of African American social, cultural, and intellectual life during the war (and afterwards) was informed by an internationalist, specifically Pan-Africanist consciousness, one in which anticolonial struggles abroad and the international fight against Fascism crucially oriented the causes of labor and the struggle for racial justice and citizenship at home. This anticolonial, diasporic perspective cut across political divisions within black leadership and the black intelligentsia and resonated with urban middle-class and working-class constituencies alike.Footnote 60 During the war, Robeson himself worked tirelessly in support of African liberation struggles. Beginning with its formation in 1941, for example, he served as the chairman of the Council on African Affairs (CAA) with Max Yergan, an influential black activist, serving as executive director. The council was founded in 1937 for the purpose of disseminating accurate information on Africa and to serve as a lobbying force to promote the cause for African liberation.

Even before the main period of his Popular Front activism, Robeson devoted himself to exploring African culture, history, and languages as a means towards combating racist mythologies about Africa as “the dark Continent” without history or civilization. In addition to learning ten African languages (as a student in London at the School of Oriental and African Studies), he wrote numerous scholarly articles on African culture and history. Robeson believed that African cultural and spiritual values, as he understood them, would provide the path to unite people of African descent in the diaspora. Only through embracing their African heritage and maintaining cultural and political autonomy, Robeson theorized, could black people make a profound contribution to world civilization. “The thirties,” as Sterling Stuckey has commented, “was the period of his most creative insights into the nature of black cultures, the time of his most profound reflections on the state of world cultural systems. . . . Robeson's scholarship on Africa provided the backdrop for his exploration of the main lines of African American achievement and failure, for his formulation of the terms on which freedom must be won by his people.”Footnote 61

Black nationalism, then, was not an end but a means to a global liberation from colonialist structures and racial oppression. Robeson's theorizing thus in some ways anticipated the internationalist perspective that would become widespread in black political discourse in the years following the premiere of Ballad for Americans. Writing in 1943, Robeson expressed the prevailing black view on the war's stakes this way:

Other peoples. . . besides the direct victims of Axis aggression also have a genuine awareness of the democratic significance of the present conflict. . . . American Negroes have such an outlook. It dates most clearly perhaps from the Fascist invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. Since then, the parallel between his own interests and those of oppressed peoples abroad has been impressed upon him daily as he struggles against the forces which bar him from full citizenship, from full participation in American life.Footnote 62

In many ways, Robeson's performances of Ballad for Americans constituted the most direct musical statement of his dual commitment to the universal liberation of oppressed peoples and black liberation. The work's fusion of radical politics and popular sound offered Robeson, as Hazel Carby has observed, a form and a forum to combine his musical and political voices. In the process, it also popularly transformed the racial significations of his voice “to create an alternative narrative while drawing upon the familiarity of the audience with the racialized aesthetics derived from Robeson's body.”Footnote 63

“I am. . . America!”

Notwithstanding Robeson's stature within the African American community, his courageous activism as “artist and citizen,” and his role as, in historian Mark Naison's words, “the left's leading exponent of cultural pluralism,” Robeson's performances of Ballad for Americans became a target for criticism by vanguard leftist intellectuals who were heavily invested in criteria of black folk authenticity that Robeson not only did not fit but of which he was the inverse.Footnote 64 As a mass-mediated, crossover star, his image and voice could never be framed as an authentic import outside the culture industry. Robeson could not be “discovered.”Footnote 65

One of the earliest critiques of Robeson's singing of Ballad for Americans appears in James Agee's 1944 Partisan Review article “Pseudo-Folk.” Agee complains bitterly that the vigor and folk purity of “true lyric jazz” were being ruined by the twin commodified evils of modern jazz styles and Broadway populist “pseudo-folklore,” the latter a genre epitomized by Robeson's Ballad for Americans. Agee characterizes the popularity of such musical products as a “galloping cancer,” destroying the tastes and culture of African Americans, whom he calls “our richest contemporary source of folkart, and our best people en bloc.”Footnote 66 After stating that he believes Robeson “is essentially a good man,” Agee asks, “What can one think of the judgement of a man who over and over, to worse and worse people, has sung the. . . esthetically execrable Ballad for Americans?”Footnote 67

Indeed, for a generation of postwar critics and historians Ballad for Americans came to symbolize the excesses of 1930s populist art and social realism.Footnote 68 Echoing the Adornian overtones of Agee's critique, Stanley Aronowitz, for example, derided it as “the apogee of an easy-listening music that made the left the vanguard of commercial culture,” and Warren Susman judged it the sonic equivalent of Norman Rockwell's Saturday Evening Post covers, a sentimental, middle-class multicultural “pseudofolk ballad.”Footnote 69 In a word, kitsch.

The tremendous popularity of Robeson's Ballad for Americans was of course the chief evidence against it. Especially damning for left critiques, however, was the ease with which the piece had been appropriated to serve reactionary ends; for in the summer following Robeson's legendary radio broadcast, the GOP leadership famously selected Ballad for Americans to serve as the opening theme song for the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia held on 23 June 1940. But on this occasion the piece was performed with—or rather without—a difference. As a dispatch for Time magazine reported it:

Last week the Republican National Convention was opened with a performance of the Ballad [for Americans], somewhat tamer than Robeson's, by Baritone Ray Middleton. The Republicans were reported to have considered inviting Robeson to sing, decided against it because of his color. Until New Dealers twitted them about it, the Republicans were apparently unaware that Ballad for Americans was written originally for a WPA Theatre Project show in Manhattan. Nor did they seem to have reflected that Paul Robeson and the authors of the Ballad—John Latouche (words), Earl Robinson (music)—are well-known Leftists.Footnote 70

The original WPA theater production to which the report alludes was the FTP's ill-fated revue Sing for Your Supper, which was rehearsed for some thirteen months before opening at the Adelphi Theater on 24 April 1939. It closed after only six weeks, the first cultural victim of the infamous Dies Committee on Un-American Activities (the prototype for and forerunner of the McCarthy hearings), spearheaded by the Texas Dixiecrat and anti-Communist demagogue Martin Dies. According to Robinson, Dies tried to subpoena the actual sets from the production.Footnote 71 During the hearings, Dies called Robinson-Latouche's Ballad for Americans “an American version of the Internationale,” and another Dixiecrat, Congressman Clifton A. Woodrum of Virginia, chair of the House Sub-Committee on Appropriations, reportedly stood on the floor of the house and angrily barked, “I have here the manuscript of Sing for Your Supper. If there is a line or passage in it that contributes to cultural or educational benefit or uplift of America, I will eat the whole manuscript.”Footnote 72

While many stories in the mainstream press treated the Ballad for Americans' reversal of political fortune at the Republican National Convention with amusement, the radical weekly New Masses denounced the Republican's appropriation, calling it a “form of insolence” and excoriated the hypocrisy of “a party that tries to entice Negro votes in the name of Abraham Lincoln,” not letting “a Negro, Paul Robeson, sing at its convention. It selected a white man instead.”Footnote 73 Yet a number of papers told the story differently: the Republicans did reportedly invite Robeson to sing at the event but he flatly refused—and not only for political reasons. He was already engaged to perform Ballad for Americans elsewhere that same night, namely, at New York's Lewisohn Stadium before a cheering audience of 14,000.

The week following the Ballad for Americans' dueling performances at Lewisohn stadium and the Republican National Convention, The New Yorker interviewed Robinson and Latouche for a report on the “romantic and unusual musical coincidence.” With the signature breezy irony of the “Talk of the Town” section, the magazine noted:

We found that the authors were planning to hear their song at the Stadium rather than in Philadelphia. They said they were very surprised that it was chosen by the G.O.P. as a curtain-raiser. Mr. Latouche expressed himself as “flabbergasted,” while Mr. Robinson said, “It's the weirdest thing I ever heard of.” “We wrote the Ballad for Americans for everybody, not only the Republicans,” said Latouche. “Especially not only the Republicans, said Robinson.”Footnote 74

The Lewisohn Stadium concert marked Robeson's debut at the popular outdoor concert series. Robeson sang accompanied by the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra with two mixed choruses: one white, the Hugh Ross's Schola Cantorum, and the other black, the Wen Talbert Choir. Along with his performance of the Ballad for Americans, the concert also marked the premiere of two other works: William Grant Still's And They Lynched Him on a Tree and Roy Harris's “Challenge of 1940.” The pairing of Ballad for Americans and Still's And They Lynched Him on a Tree invited listeners to hear both pieces as “race music,” not only as testaments against racial injustice but also promoting interracial harmony. Writing in his column for the Amsterdam News, W. E. B. Du Bois called the concert “the greatest event of the month”; and Carl Diton, the reviewer for the Pittsburgh Courier, after commending Robeson for “using his unerring skill to ferret out the hidden potentialities of the text,” described the event as a “unique interracial concert. . . . Splendid ammunition this was for the Dies Committee.”Footnote 75

Several weeks following Robeson's Lewisohn debut concert in July 1940, the entire program received a second West Coast hearing at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, jammed to capacity with over 30,000 people, the largest crowd ever to attend a concert there. For this performance, Robeson sang with the Philharmonic Orchestra and the Hall Johnson Choir who were then located in Los Angeles.Footnote 76 In between New York and Los Angeles, Robeson attracted ecstatic audiences in Chicago, where tens of thousands crowded into Grant Park to hear Robeson and Lawrence Brown deliver a program comprising his core concert repertoire. For an encore, Robeson performed a piano-vocal version of Ballad for Americans with Brown, which one critique described as “indescribably moving.”Footnote 77 Unfortunately, there is no extant recording of this version so we can only imagine the very different effect and sonic significations of hearing Ballad for Americans in this performance context. For Robeson, as is well understood, owed much to his longtime accompanist and arranger, who played an influential role in shaping his interpretation of black sacred and secular music.

Agee's denunciation of Robeson appeared in the context of a broader critique of popular black performers and artists. Besides Robeson, Agee singled out Duke Ellington's “more ambitious arrangements and compositions” for censure along with the “pathetic vocal imitator” of Robeson at Café Society (baritone Kenneth Spencer), the “dreadful pseudo-savage” choreography of Katherine Dunham and her troupe, and what Agee saw as a sellout by Louis Armstrong.Footnote 78 Pianist Hazel Scott, however, came in for Agee's most withering criticism. Scott, who was a regular act at Café Society during the late 1930s and early 1940s, gained a following for her special brand of “crossover” jazz piano—swinging the classics and classicizing jazz standards and boogie-woogie, a practice to which Agee strongly objected: “The quintessence of this special kind of vicious pseudo-folk is Hazel Scott. She plays the sort of jazz one could probably pick up, by now, through correspondence school. . . . Her ‘swinging’ of. . . ‘classics’ is beyond invective.”Footnote 79

Agee's comparison of Robeson and Ellington is particularly apt but not for the reasons Agee would be likely to recognize. Agee's comments position both artists as simple, good folk corrupted by the capitalist culture industry, lured by “big-city” desires for fame and money. Indeed, his denunciation of Robeson's Ballad for Americans recalls strongly the critical discourse that swirled around Ellington's Black, Brown and Beige just a year prior in 1943, a discourse driven by the tastes and paternalist perceptions of many white critics and promoters of black vernacular music. On this point, it is significant that Robeson, along with Ellington, was absent from the stages of at least two celebrated Popular Front–affiliated performances of contemporary black music—John Hammond's famous 1938–39 “Spirituals to Swing” concerts in Carnegie Hall.Footnote 80

Sponsored by New Masses, Hammond's first concert proudly trumpeted that it excluded artists who, as he put it, “had made serious concessions to white taste” (such as Robeson and Ellington) while nevertheless presenting a narrative of black music history based on the perspectives of white critics and promoters like himself.Footnote 81 In an announcement in the New York Times prior to be concert, Hammond boasted that his concert would present “genuine authentic performers of African-American music. . . who, for the most part, have had no formal musical training of any kind, cannot read musical notations, and have never played before white audiences or in any formal way before colored audiences”; and an advertisement for the concert in TAC Magazine promised the concert (“conceived and produced by John Hammond”) would present the “untainted” music of the “American Negro. . . as it was invented, developed, sung, played and heard by the Negro Himself,” the “first comprehensive concert of the true and exciting music of the Negro.”Footnote 82 Among the artists presented in this way were boogie-woogie pianists Meade “Lux” Lewis and Albert Ammons, blues players Sonny Terry, Bill Broonzy, and Joe Turner, and, most problematically, the Count Basie Orchestra.

Despite its ethnographic pretensions, Hammond's narrative framed these performers as “representatives” of authentic folk expression. Here, Hammond's “Spirituals to Swing” presentations made use of what was arguably the most significant cultural innovation of the urban folk song movement of the 1930s, one pioneered by the Lomaxes through the marketing of Leadbelly, namely to move beyond collecting and recording folk songs to collecting singers for the consumption of urban audiences. As Robert Cantwell has recently argued, the fashioning of “people's music” in the urban folk song movement was in many ways continuous with both the discourses and expressive practices of modernism and the racial history and stylistics of the minstrel stage, which it effectively retuned towards radical politics. As he observes, the “high-cultural ideas, initiatives, resources, opportunities, occasions, and influences” that shaped the intellectual and aesthetic ideology of the urban folk song movement “in time defined in its own terms who were the folk and [of] what authentic folk style consisted.”Footnote 83 Ironically, Hammond's second “Spirituals to Swing” concert in 1939 coincided with the radio debut of Robeson's Ballad for Americans. Billy Rowe opened his story for the Pittsburgh Courier with a lighthearted but barbed description of the evening's racial arrangement: “White folks applauded their hearts out Sunday, and colored folks sang and played their aboriginal best.”Footnote 84

Appeals to the romantic vocabularies of folk authenticity such as those used by Hammond have long served, as Paul Anderson has remarked, “as arguments for resisting the legitimacy of African-American modernism and for withholding from African-American musicians the right to create music on their own terms.”Footnote 85 The statements of both Hammond and Agee alternately celebrate and regulate black cultural authenticity to be consonant with their own racial structure of feeling, namely to keep the kind of distinctions and determinations of difference that suited whiteness.

To be sure, Ellington's conception of the category “Negro American folk music” differed from that of Robeson's—it was firmly grounded in the urban black vernacular. Nevertheless, throughout this period Ellington, like Robeson, embraced the spirit of the black popular front. For Ellington this was achieved primarily through the heightened political and social orientation of his work and in public statements that emphasized connections between the musical and political. Moreover, although Robeson and Ellington never worked together, the public fortunes of their careers after 1939 followed similar paths.Footnote 86 Like Ellington, Robeson's return from London in 1939 inaugurated one of the most productive periods of his career; and from his participation in the cultural and political life of the Popular Front, he “crossed over” from concert stage to radio, film, and musical theater. Throughout the 1940s Robeson frequented Café Society, where he came into contact with and became an important figure for a diverse circle of African American musicians and intellectuals, including Teddy Wilson, Billie Holiday, Hazel Scott, Lena Horne, Josh White, Langston Hughes, and Richard Wright.Footnote 87 Such contacts were not merely social but often spilled over to political activities. In the summer of 1940, Robeson sang at an inaugural celebration/benefit for the Negro Playwrights Company held in Harlem at the Golden Gate Ballroom. Five thousand people attended to hear Robeson and Hazel Scott perform and to listen to Richard Wright deliver a lecture on the upcoming stage premiere of his novel Native Son, directed by Orson Welles.Footnote 88

Unlike Ellington, however, Robeson's primary performance forum was the concert hall and his popular appeal ultimately remained rooted in his concert performances. After 1934 he worked tirelessly to maintain his identity both as a legitimate people's artist/folksinger and as an activist and black intellectual. Yet his vocal style and his concert repertoire occupied a different cultural/sonic space than that of black vernacular sounds of jazz, blues, and gospel.Footnote 89 If at the beginning of the 1930s Robeson's interpretations of spirituals stood as the benchmark of racial authenticity, by the late 1930s the lines of authenticity had shifted considerably. Sacred and secular black folk sound based around southern rural stylistics was heavily promoted both by cultural brokers of the urban folk song movement, John and Alan Lomax, and by popular music impresarios such as Hammond.

Unquestionably, Robeson was a celebrated and even heroic figure in the urban folk song movement; nevertheless, his interpretation of black folk sound in general, and the spirituals in particular, could only be viewed by such cultural intermediaries as hopelessly compromised. Both in sound and image, Robeson, as Carby points out, was simply too respectable; he projected a vocal and visual aura of “unapologetic human dignity” that belied romanticized images of southern black rural life, such as the Lomaxes' infamous construction of Leadbelly as a dangerous bluesman “outlaw.”Footnote 90

“King Joe”

In 1941, Robeson collaborated with Richard Wright and the Count Basie Orchestra to record a blues, “King Joe,” a tribute to Joe Louis (recorded for Okeh and directed, significantly enough, by Hammond). It is a somewhat awkward, even stilted performance; Robeson's preference for a straightforward melodic line and unadorned phrasing only underlines the sonic and stylistic gap between his voice and black vernacular sound. Count Basie reportedly commented to Hammond during the session: “It certainly is an honor to be working with Mr. Robeson, but the man certainly can't sing the blues.”Footnote 91

Robeson's inability to “sing the blues,” however, should not, as Basie's comment implies, be taken as a referendum on his racial authenticity nor as a negation of his otherwise considerable musical accomplishments. For the politics of black musical authenticity, like all discourses of folk authenticity, as much celebrated as constrained what—and who—could and could not legitimize black musical expression. On this point, Robeson's attempt to negotiate Popular Front discourses on the folk stands as a particularly striking and sobering reminder that the impulse towards aesthetic and cultural pluralism in the Popular Front was irreducibly bound up with its mirror opposite: a preoccupation with cultural authenticity, identity, and origins. These dual impulses permeated cultural politics and aesthetic debates, crossing the sociomusical spheres of concert music, jazz, folk, and swing. In performing Ballad for Americans Robeson clearly troubled all these racialized aesthetic boundaries.

Informing Robeson's desire to find a mass audience was a belief that he could use his cultural currency as a performer to effect political and social change. He tried to use his stardom to rearticulate romanticizing discourses on blackness to a progressive, internationalist social and political agenda. This constituted the central mission of his singing and acting career throughout the 1930s and 1940s.Footnote 92 Arguably, it was through performing Ballad for Americans that Robeson most successfully joined his political identity as a radical African American and his musical identity as a folksinger and “people's artist,” as the work engages populist patriotic musical and textual rhetoric to press a progressive political vision. The pageant of American history narrated in Ballad's “ballad” articulates the symbols of national memory to construct an antiracist, pan-ethnic “imagined community” in a manner that appealed to American audiences on the eve of the country's entrance into World War II. At the same time, Ballad for Americans resonated with the emerging radical black political and cultural milieu of the late 1930s and early 1940s and, by extension, with new understandings of race and nation. A review of the premiere broadcast published in the Amsterdam News put it this way:

Ballad for Americans opens up an entirely new concept of American music with its freshness of spirit and its modern cry against racial discrimination and prosecution of all kinds. With the song, Mr. Robeson was able to call forth both his superb singing and dramatic talent. His was a role and performance seldom accorded Negroes in this country.Footnote 93

And in his review of Robeson's Victor recording, jazz critic Bill Gottlieb called the disc the “most stirring contribution to records since [Billie Holiday's] ‘Strange Fruit’” and praised it as “one of the finer products of the new ‘national consciousness’ inspired by the European war. It is a song with meat in it, a ballad that rings true in somber moments.”Footnote 94 Indeed, Robeson's Ballad for Americans stands as one of the most dramatic public representations of the Popular Front emphasis on interracial unity and black racial inclusion within the nation.Footnote 95 Robeson's performances of Ballad for Americans registered the close relationship between black citizenship and the construction of American identity as the moral bearer of universal democratic ideals. Its narrative of nation and belonging implicitly addressed, however partially, the symbolic power of this relationship, juxtaposing the nation's rhetoric of enlightenment and freedom against the realities of racism and social injustice. This contradiction would become by 1942 the key ideological fissure that black activists, intellectuals, and civic leaders exploited to advance what was up to that time the most radical drive for racial justice and equality since Reconstruction. As Robinson would later observe in tribute to Robeson's antiracist activism: “Ballad for Americans proved a powerful ally. For a black man to keep saying, ‘You know who I am,’ ending up claiming to be America, contradicted the way most people thought and acted.”Footnote 96

Yet the ideological conflict in Ballad for Americans between accommodation and protest, national affirmation and critique, the realities of racial and ethnic divides, and the promise of national inclusiveness indexed troubling contradictions of race and nation—ones that coalesced around the materiality of Robeson's voice. As Singh has astutely observed: “Americanism of this sort was an ambivalent cultural production—a contradictory distillation of a powerful new universalizing rhetoric and intensifying racial violence and division.”Footnote 97 Robeson's singing of Ballad for Americans sharpened the pitch of the narrative's ambivalent “political unconscious.” As I have argued here, Ballad for Americans, particularly when imagined as part of the performative black internationalism embodied in Robeson's concert programs, symbolized not a false unity but the unfinished business of universal democracy. That is why Robeson chose to sing Ballad for Americans “over and over” again, to borrow Agee's language.

With the US entrance into the war, however, public pledges of black inclusiveness, as Singh reminds us, did little to stop the rapidly widening sphere and power of black protest as the “hard facts of racial segregation, particularly in the military, continued to stir black dissent.”Footnote 98 Such were the immediate conditions that led to the Pittsburgh Courier's “Double V” campaign, which was inaugurated in February 1942. Citing the popular black radicalism that marked the first wave of the civil rights movement in the 1940s, film scholar Kevin Jack Hagopian invites us to hear Robeson's version of Ballad for Americans as a critical, “signifying” act on what he views as an essentially bland, “color-blind” ode to Popular Front romantic pluralism. “The grandeur of Ballad for Americans for modern. . . listeners,” he argues, “lies not in the lost dream of Popular Front unity, but in the way Paul Robeson used Ballad for Americans against itself, as a critical inquiry into brotherhood denied.”Footnote 99

But Robeson did not so much use the work “against itself” as he made manifest the contradictions of race and nation already in the work. From its radio debut in 1939 to the present, Robeson's voice critically and irrevocably mediated the musical, social, and political significations of the work; his massively popular performances of the work on radio, on recording, and in concert venues, then, represent more than one among many interpretations; rather, as mentioned at the outset, he collaborated with Robinson in shaping the piece as we know it. Robinson himself perhaps put it best: “[W]ith each singing of the piece, with Big Paul there or a thousand miles away, his America hung in the concert hall like a great fraternal, democratic aura.”Footnote 100