Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a recurrent and chronic condition that is prevalent in 1–5% of the population (Goodwin and Jamison, Reference Goodwin and Jamison2007; Hadjipavlou et al., Reference Hadjipavlou, Bond, Yatham and Parker2012; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin and Walters2005) Individuals diagnosed with BD experience mood states that vacillate between depression and mania, in addition to impairments in cognitive and psychosocial functioning, which contribute to decreased quality of life (Bourin, Reference Bourin2019; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Akiskal, Schlettler, Endicott, Leon and Solomon2005; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Schettler, Solomon, Maser, Coryell, Endicott and Akiskal2008; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015; Sole et al., Reference Sole, Jimenez, Torrent, Reinares, del Mar Bonnin, Torres and Vieta2017).

Studies emphasize that interventions that are solely psychiatric/medical are not effective enough, and thus a more holistic approach is needed (Colom et al., Reference Colom, Vieta and Moreno-Sanchez2009; Zaretsky et al., Reference Zaretsky, Rizvi and Parikh2007). Psychosocial interventions for BD are mostly studied by measuring the effect of individual therapy sessions on clinical symptoms (i.e. depressive, hypomanic and anxiety) as well as psychological variables such as life satisfaction, and psychological well-being (Mar Bonnin et al., Reference Mar Bonnin, Reinares, Martinez-Aran, Jimenez, Sanchez-Moreno, Sole and Vieta2019).

Research studies indicate that cognitive behavioral group therapies for BD reduce the frequency and duration of manic and/or depressive episodes as well as improve group members’ social functioning and their quality of life (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Cheniaux, Legnani Rosaes, Carvalho, Rocha Freire, Versiani and Nardi2010; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Cheniaux, Range, Versiani and Nardi2012; Gonzalez-Isasi et al., Reference Gonzalez-Isasi, Echeburua, Liminana and Gonzalez-Pinto2014; Patelis-Siotis et al., Reference Patelis-Siotis, Young, Robb, Marriott, Bieling and Joffe2001; Thomaz da Costa et al., Reference Thomaz da Costa, Cheniaux, Legnani Rosaes, Regine de Carvalho, da Rocha Freire, Versiani, Rangé and Egidio Nardi2011; Veltro et al., Reference Veltro, Vendittelli, Oricchio, Addona, Camillo, Figliolia and Pierluigi2008). Hence, the current study utilized the main components of the integrative cognitive model (ICM) of BD in order to develop an 8-week group therapy intervention (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007).

Group-based intervention for the integrative cognitive model

The ICM proposes that mood dysregulation is caused by extreme, personal and conflicting appraisals of changes in internal state. According to the ICM, an internal state consists of feelings (e.g. happy), physiological symptoms (e.g. high energy), behavior (e.g. pressured speech) and cognition (e.g. racing thoughts) (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007). For instance, an individual with BD in a hypomanic state may evaluate their elevated mood state both positively (e.g. feeling elated and excited) and negatively (e.g. feeling irritable and agitated) as well as their racing thoughts both positively (e.g. feeling smart and productive) and negatively (e.g. inability to concentrate and collect thoughts) (Mansell, Reference Mansell2006; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Powell, Pedley, Thomas and Jones2010; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Paszek, Seal, Pedley, Jones, Thomas, Mannion, Saatsi and Dodd2011). Therefore, the person may then alternate between ascent behaviors such as being more sociable to enhance the elevated feeling (e.g. going to parties) or trying to speed up their thinking further to be more productive (e.g. taking stimulants) and descent behaviors such as being less in contact with people to minimize agitation or to slow down their thoughts to be able to concentrate (e.g. social withdrawal) (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Powell, Pedley, Thomas and Jones2010; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Mansell, Wood, Alatiq, Dodd and Pearson2011; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Mansell, Sadhnani and Wood2012; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Dodd and Mansell2017). In summary, the ICM proposes that conflicting positive and negative appraisals of the same mood state (e.g. racing thoughts) lead to exaggerated and contradictory attempts to control that internal state (e.g. taking stimulants or social withdrawal), resulting in maintenance and exacerbation of mood fluctuations (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Powell, Pedley, Thomas and Jones2010).

The ICM has developed the Think Effectively About Mood Swings (TEAMS) approach in order to help the individual with BD become more aware of their conflicting appraisals and exaggerated attempts to control their internal states, and to acquire healthy coping skills to deal with mood swings and pursue their life goals despite changes in mood (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015). The aim of the TEAMS approach is to enhance recovery and improve quality of life by developing an image of a ‘healthy self’. The TEAMS approach argues that the healthy self is an integration of different self-states. With the help of the TEAMS approach, the individual with BD learns to integrate their conflicting self-states by identifying each one of them first, and then marking their intensity on a sliding scale and finally, realizing that all these self-states overlap and fall on a continuum (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Tai, Clark, Akgonul, Dunn, Davies and Morrison2014; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015; Searson et al., Reference Searson, Mansell, Lowens and Tai2012). The healthy self enables the individual with BD to pursue their short-term and long-term life goals despite mood fluctuations (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015).

The current research evaluated an 8-week group therapy programme based on the ICM’s TEAMS goals and objectives. The main objective of the current research was to investigate the effect of an 8-week ICM-based group therapy intervention. Changes in depressive symptoms, hypomanic attitudes and psychological processes (life satisfaction and well-being) were analysed. Secondly, individual experiences were qualitatively investigated.

Hypotheses based on the quantitative aspects of the research were as follows:

-

There will be a reliable change in depressive symptoms after the intervention.

-

There will be a reliable change in hypomanic attitudes after the intervention.

-

The life satisfaction and well-being scores will be clinically significant after the intervention.

-

Improvements made by the 8-week ICM-based group therapy will last at least for 3 months.

Method

The sample consisted of 60 patients with BD-I or BD-II and who did not attend any other treatment programme. Individuals were contacted via telephone and intake interviews were conducted with 20 patients. Fourteen out of 20 patients accepted to take part in the study. The intervention group in the first study consisted of six patients and the second study consisted of eight patients. The flow diagram in the Fig. 1 demonstrates the sample recruitment and participation process.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of sample recruitment and participation process.

Figure 2. Reliable change index results for post- and follow-up measures.

The inclusion criteria were being 18–60 years in age, being diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD-I and BD-II), being fluent in Turkish and giving their consent for participation. Exclusion criteria for the study were as follows: being in a manic state or exhibiting a mixed episode concomitant with a manic state; diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; main diagnosis being drug abuse, brain damage or cognitive impairment that might hinder the therapeutic process and surveys; suicidal thoughts and pregnancy for female patients.

In total, four patients left the study. From the first intervention group, one participant left the study because of the increase in their hypomanic symptoms related to the inconsistent use of medication. The other participant did not complete the 8-week programme due to the increase in depressive symptoms. From the second intervention group, one participant left the study due to hospitalization related to alcohol dependence. The other participant left due to an increase in hypomanic symptoms. Although the two other participants (Participants 4 and 10) did not complete the 8-week programme, they both attended the evaluation interviews and thus their scores were added to the data analysis.

The sample consisted of 10 patients with BD-I (n = 7) and BD-II (n = 3). There were six female and four male participants. The mean age of the sample was 33.9 ± 8.73 years. In terms of employment status, four participants were students, two were employed, two were self-employed, one was unemployed, and one was retired. The type of the last episode was identified as follows: major depressive episodes by six patients (Participants 2, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 10), mania by one patient (Participant 1), hypomania by one patient (Participant 3) and mixed episodes by two patients (Participants 7 and 8). The rest of the clinical characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics

Materials

The current research utilized the Turkish versions of the Beck Depression Scale, the Hypomanic Attitudes and Positive Predictions Inventory, the Psychological Well-Being Scale, the Satisfaction with Life Scale and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. The instruments and their implementation times used in this study can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. The measures used for assessment and timing of assessments

* Throughout the 8-week process, each participant’s sharing was noted down by the group assistant (A.K.).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The Turkish version of the BDI (Hisli, Reference Hisli1988, Reference Hisli1989) was used in this study (split-half reliability, .74). Scores equal to or higher than 17 indicates depression that requires treatment. The internal consistency-reliability analyses have found this scale to be reliable for its current use (α = .87). The BDI total item correlations were found to be between .23 and .67.

Data collection form

In the Demographics section, participants provided information about their age, sex, education level, marital status and employment status. In the Clinical Information section, participants provided information about the clinical diagnosis, duration of the disorder, the number of episodes they experienced, existence of psychotic symptoms during an episode, the most recent episode, hospitalization history, suicide attempts and types of medicine they are using.

The Hypomanic Attitudes and Positive Predictions Inventory (HAPPI) TR-41

The first version (104 items) of the HAPPI was developed by Mansell (Reference Mansell2006) to assess multiple, conflicting self-appraisals related to changes in internal states, and to evaluate beliefs that trigger, maintain and exacerbate hypomanic episodes. Higher scores indicate that hypomanic attitudes are more prevalent. There are several versions of the HAPPI with different factor structures and different number of items (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Mansell, Sadhnani, Morrison and Tai2010; Mansell and Jones, Reference Mansell and Jones2006; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Rigby, Tai and Lowe2008; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Powell, Pedley, Thomas and Jones2010). In the Turkish adaptation study (Maçkalı and Güneri, submitted for publication), the internal consistency coefficient of the 41-item HAPPI was .95. A six-factor structure was detected: Social Self-Criticism (α =.94), Success Activation and Triumph Over Fear (α =.76), Loss of Control (α =.74), Increasing Activation to Avoid Failure (α =.83), Grandiose Appraisals (α =.72) and Appraisals of Extreme Social Approval (α =77). The test–re-test reliability was found as r = .43.

The Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWS)

The PWS is an 8-item scale, which measures psychosocial properties such as having positive relationships and having a meaningful and a purposeful life, uses a 7-point Likert scale (originally developed by Diener et al., Reference Diener, Scollon, Lucas and Diener2009; Turkish translation by Telef, Reference Telef2013). The higher scores indicate more psychological strength and resources. The reliability analysis revealed this survey to be reliable (α = .87).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS consists of five items with a 7-point Likert scale (original version: Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985; Turkish version: Durak et al., Reference Durak, Senol-Durak and Gencoz2010). The test–re-test reliability of the scale was .85 and the Turkish version’s internal consistency was .83.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)

Çorapçıoğlu et al. (Reference Çorapçıoğlu, Aydemir and Yıldız1999) conducted the reliability and validity analyses of the Turkish translation of the SCID-I (originally developed by First et al., Reference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin1997). The current study used modules to assess anxiety disorders except the ones that are used for measuring specific phobias.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board of Hacettepe University Clinical Research gave permission to conduct the current study (decision number: GO 16/216-08). During the forming phase of the intervention group, before the first session, individual interviews were conducted with the participants wherein informed consent was obtained and the research instruments were administered.

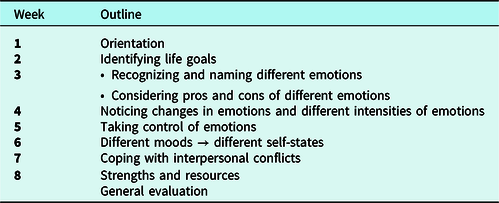

The 8-week group therapy intervention was constructed based on ICM’s TEAMS goals and objectives (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015). Each group session lasted for 1.5 hours. The main goal of the first session was to orient group members to the group process and the ICM model. The objectives of the second session were to determine group members’ short-term and long-term life goals. The following sessions aimed at making connections between weekly session goals and the group members’ life goals. Reflection activities were conducted during group sessions to address the conflicting coping strategies that the group members use when they experience a mood fluctuation. Each session started with participants sharing their thoughts and feelings, followed by a review of last week’s session and a discussion of that week’s assignment. Sessions ended with a session summary and a brief description of the next week’s assignments.

The 8-week ICM-based group therapy session goals were as follows:

-

Identifying and considering pros and cons of different emotions; recognizing and re-evaluating the mood fluctuations.

-

Identifying life goals and pursuing life goals despite mood dysregulation.

-

Identifying different self-states and understanding their impact on interpersonal conflicts.

-

Assessing personal strengths and resources.

In summary, the main objective of each session was to encourage group members to be cognizant of alternative, effective and healthy coping skills to deal with mood fluctuations (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015). Table 3 demonstrates the session outline.

Table 3. Eight-week ICM-based group therapy outline

In order to provide a safe and comfortable environment, a graduate student assistant took detailed notes regarding group discussions instead of audio recording. All scales were readministered at the end of the last session and on 3-month follow-up.

During the 1-month follow-up, participants were asked to provide qualitative feedback in a semi-structured interview. The aim of these interviews was to understand the participants’ experiences and perception about the intervention. Participants were asked to evaluate the 8-week intervention by answering the open-ended questions (Byrne, Reference Byrne and Seale2016). The open-ended questions asked during the 1-month follow-up interview were as follows:

-

Tell me about your group experience?

-

Which activities have benefited you the most?

-

Which activities were not useful for you?

-

Have you ever noticed any change in your mood, behavior or life goals?

-

In which contexts have you noticed these changes (during or following group therapy)?

-

Is there anything you would like to suggest to improve this 8-week group therapy?

-

Is there anything that I should have covered during the 8-week group therapy?

Data analysis

Quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted. Clinical significance, which is the aim of the treatment for participants, was prioritized during the assessment of the effect (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin1999).

Quantitative analyses

Descriptive analyses were used to assess demographic and clinical information. As the sample size was small, the reliable change index (RCI) (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) was used to analyse individual changes in scores. To calculate RCI, changes in scores were divided by the standardized difference (in this research, standard deviation and Cronbach’s alpha of the pretest scores) to find a change score. The change score is needed to reach a corresponding standardized Z-score of less than –1.96 or above 1.96, which means that this change would be considered to occur less than 5% by chance. As a result, the change score will represent a reliable change rather than error (De Souza Costa and De Paula, Reference De Souza Costa and De Paula2015; Zahra and Hedge, Reference Zahra and Hedge2010). Furthermore, an online calculator was used to calculate the RCI (https://www.psychoutcomes.org/OutcomesMeasurement/ReliableChangeIndex). The RCI was calculated by analysing the changes in pre–post test scores and pre-3-month follow-up scores.

Qualitative analyses

Data collected during the 1-month follow-up interview were used for analyses. Answers to the open-ended questions were analysed via thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is the process that reveals the content patterns within qualitative data and to analyse data based on the frequency of such patterns. Frequent patterns indicate categories that stand out within data. Thus the most important parts of the data can be analysed in line with the research questions (Bilgin, Reference Bilgin2006; Joffe, Reference Joffe, Harper and Thompson2012). In the current study, participants’ personal experiences regarding the treatment were investigated (Willig, Reference Willig2009), while taking into consideration how the findings could be clinically applicable and effective.

The thematic analysis process was as follows. Transcriptions of each interview were read at least three times, allowing coders to familiarize themselves with the content. Later, contents and keywords were compiled to prepare a coding sheet. Consequently, categories based on the patterns that were found in the raw data were created. A relevant piece was assigned under each appropriate category. Each category was reassessed by examining its relevance to the coded pieces and the information gathered from the interviews (Bilgin, Reference Bilgin2006; Clarke and Braun, Reference Clarke, Braun, Lyons and Coyle2015). After the initial determination of the categories, codes and coded interview pieces, three clinicians assessed the relevance of these data. The first reviewer, who has a PsyD in clinical psychology, is an expert on the individual and group psychotherapy treatments of bipolar disorder. The second reviewer, who has a PhD in clinical psychology, has expertise on group therapy practice. Finally, the third reviewer, who has a master’s degree in clinical psychology, specializes in qualitative methods.

Results

This section will provide quantitative and qualitative data of 10 participants. Ninety per cent of our participants completed the post-test measure; 80% of them attended the 1-month follow-up interview and 60% of them completed the 3-month follow-up measure.

Results from quantitative analyses

According to the results of the RCI (which compares changes in pre–post test scores and pre-3-month follow-up scores), there was a reliable change only in pre-test and post-test depression scores. However, this change could not be maintained at 3-month follow-up. Three participants (Participants 1, 5 and 9) experienced reliable improvement; one participant (Participant 7) experienced reliable deterioration and six participants had no change. Figure 2 displays the results for the RCI.

Results from qualitative analyses

Beneficial exercises

Participants have reported the most beneficial activities as follows: defining emotions, rating of emotions, determining life goals, coping with interpersonal conflicts, and assessing personal strengths and resources. Moreover, they reported that the intervention helped them to understand that the intensity of their emotions varies in different life situations and raised their self-awareness about their different self-states.

Participants reported that they especially benefited from the third session, which consisted of exercises that involved defining emotions and activities that enabled them to understand the relationship between emotion, thought and behavior. For example, Participant 7 said: ‘It was beneficial because it made me think more about my emotions, about how I feel and how much I feel…’. Participants reported that the third session, which included the idea that emotions are natural reactions to events and that everybody’s emotions fluctuate at times, was very helpful. It can be argued that the third session changed participants’ misperceptions about their mood changes and normalized their overall experience. For instance, Participant 3 stated: ‘The fact that anger, frustration or any other emotion is felt by everyone, but it is bad when an emotion lasts days or weeks, caught my attention and it stuck with me. Experiencing an emotion is fine but when it turns into a mood, it becomes problematic.’ Realizing that emotions can be negative or positive have also helped participants to regulate their reactions accordingly. For example, Participant 1 said: ‘I am not feeling good today, but I might be good tomorrow. I am not feeling well, but I will make an effort and maybe it works…’.

The fourth session, which involved rating the intensity of feelings, helped participants better evaluate the intensity of their feelings and thus enabled them to regulate their emotions as they developed a capacity to tolerate them. For example, Participant 2 stated that when they experienced a hypomanic increase, rating their emotion on a sliding scale helped them realize what they were going through: ‘Rating came to my mind. I thought about the intensity of emotion I was experiencing at the beginning of my hypomanic episode. I thought ways in which I can stop it from happening.’

Six participants stated that contemplating their life goals helped them to take the necessary steps to reach that goal. For instance, Participant 5 stated: ‘Identifying life goals… maybe I am doing it right now… Walking, doing what I want, having the motivation to work out… I think all of these helped me to define my life goals. I want to have a healthy life, for both body and soul, in the long term.’

Three participants indicated that the exercises during the seventh session raised their awareness about their feelings during an interpersonal conflict; it allowed them to use effective interpersonal skills and helped them solve their interpersonal conflicts accordingly. For example, Participant 6 stated: ‘There was a session about relationships… The exercises really resonated with me and I embraced them. Later, I put those interpersonal skills into practice. I gave myself time to think before acting. I tried to be less destructive and more constructive…’.

Talking about strengths and resources in the eighth session helped participants to manage their daily activities effectively and made them more resilient to mood dysregulation. For instance, Participant 3 stated that being more active and social was part of their long-term goals and thus, they started to use the daily activity checklist to make sure that they were on target. Moreover, Participant 1 stated: ‘The last worksheet you gave [List of Strengths and Resources] was very helpful. Questions you ask yourself on a daily basis: What have you done today? Have you taken a shower today? Even it seems that you are not accomplishing anything, you realize that actually you are doing something.’

Gains

The codes under this category are as follows: self-awareness, social support, acceptance and self-perception. It was found that the group intervention was especially beneficial in raising self-awareness and improving social support.

Self-awareness

After the 8-week group intervention, participants were able to make observations about their behavior and gained awareness regarding their needs. As a result, participants were able to take the necessary action to fulfil those needs. Participants had a better understanding about the reasons why they behaved the way they did and what they wanted in life. Moreover, participants learned to tolerate their emotions. When they experienced a fluctuation in their mood, they showed an effort to understand their feelings instead of suppressing and/or avoiding them. It can be argued that participants improve their skills to decenter. For example, Participant 5 stated: ‘I feel like I was drinking alcohol just to be stubborn. I guess I wanted to punish myself. I have realized that pursuing a healthy lifestyle is one of my long-term goals. Therefore, I decreased my alcohol consumption. I do not feel like drinking anymore. I was smoking too. Now I am smoking electronic cigarettes. I am trying to eat healthier. I started going for walks although it is not every day. I feel like I made a lot of progress.’

Social support

All participants stated that they benefited from meeting people with similar conditions. They reported that sharing their feelings and listening to others’ experiences were crucial. It can be argued that being around people who experience similar disadvantages, alleviated participants’ feelings of loneliness. For instance, Participant 6 stated: ‘It was nice to share. Everybody had a different perspective on things and that was so good. Talking to others was great.’

Acceptance

It was observed that group intervention helped participants to accept their mood fluctuations and their BD diagnosis. For example, Participant 10 stated: ‘I started to normalize my bipolar diagnosis. It was very difficult for me to accept the diagnosis at first. I have realized that I am not the only one with this disorder. Those people also have families and jobs. I started sharing my diagnosis with my inner circle. It is a biological condition after all. I feel more comfortable thinking about my condition that way.’

Self-perception

Four participants mentioned that being able to complete the group therapy sessions made them feel good about themselves. It can be argued that the fact that they continued group therapy despite adversity had a positive impact on their self-perception. For instance, Participant 6 stated: ‘I joined the group because I wanted to. I did not miss any sessions. When I don’t feel like it, I tend to slack off. I didn’t do it this time. There were times I felt tense, but I had the intent of attending.’ Participant 9 declared: ‘I couldn’t attend two sessions in between. I usually slack off, but this time I really tried. I tried not to give up.’

Discussion

The 8-week ICM-based group therapy revealed reliable change on only pre-test and post-test scores of depressive symptoms. However, this change could not be maintained at 3-month follow-up. Studies investigating BD symptoms from a cognitive behavioral therapy perspective incorporated booster sessions in their follow-ups. With the help of booster sessions, most studies reported a change after a 6-month follow-up (Castle et al., Reference Castle, White, Chamberlain, Berk, Berk, Lauders and Gilbert2010; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Cheniaux, Legnani Rosaes, Carvalho, Rocha Freire, Versiani and Nardi2010; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Cheniaux, Range, Versiani and Nardi2012; Gonzalez Isasi et al., Reference Gonzalez-Isasi, Echeburua, Liminana and Gonzalez-Pinto2014; Meyer and Hautzinger, Reference Meyer and Hautzinger2012). Thus, one reason for a lack of clinically significant effect on depressive symptoms after 3-month follow-up might have been due to lack of booster sessions. Moreover, booster sessions can be conducted monthly for 6 months. The aim of booster sessions is to help participants to continue to re-evaluate and re-integrate their different self-states and flourish their healthy self as a result. Furthermore, a statistically significant change between pre-test and post-test scores of hypomanic attitudes, life satisfaction and well-being scores might have been found if the sample size was greater; the current study was also limited by the absence of a control group (Hawley, Reference Hawley1995; Kazdin, Reference Kazdin1999).

Qualitative analysis conducted at 1-month follow-up indicated that participants benefited from the exercises conducted in the fourth session. However, participants experienced difficulty rating the intensity of their emotions during this session. It might be interpreted that the difficulty they experienced might be due to emotional avoidance. Once they built tolerance for different intensity of emotions, participants became more aware of their different mood states. The increase in tolerance enabled participants to be more cognizant of warning signs of symptoms of a hypomanic or a depressive episode. Remembering that they can feel differently at different times might help participants compile a wide repertoire of coping strategies and in return, help them to reorganize. This argument is consistent with the ICM (Carr, Reference Carr2004; Joyce et al., Reference Joyce, Tai, Gebbia and Mansell2016; Mansell, Reference Mansell2005; Mansell, Reference Mansell, Grant, Townend, Milhem and Short2010; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Tai, Clark, Akgonul, Dunn, Davies and Morrison2014).

The exercises about determining short-term and long-term life goals conducted in the second session was another activity that participants found beneficial. Thinking about life goals helped participants to define the aspects that they wanted to change or add to their lives and implement changes towards reaching those goals. Participants’ discussion about the positive changes in their lives during 1-month follow-up suggested that identifying life goals was a crucial step for the sustainability of their well-being. Russell and Browne (Reference Russell and Browne2005) and Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Suto, Hole, Hale, Amari and Michalak2010) also pointed out that determining goals to change one’s life has a positive impact on individual well-being. Moreover, the ICM argues that participants’ awareness of their inability to determine life goals is meaningful for the treatment process (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Powell, Pedley, Thomas and Jones2010). The awareness helps participants to connect with the indecisive part of themselves and enable them to make decisions progressively (Norcross et al., Reference Norcross, Krebs and Prochaska2010; Prochaska and Diclemente, Reference Prochaska and DiClemente1982).

The exercises about coping with interpersonal conflicts conducted in the seventh session was also among activities that participants found beneficial. Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Mansell and McEvoy2016) emphasized that contemplating the aspects, which one desires to change in a relationship, is an important step in the right direction. Participants mentioned that thinking about what they value in relationships helped them to become aware of their emotions during conflicts and to respond constructively. Therefore, it can be inferred that defining their core values in relationships helped participants to clarify their relationship goals and gave them the opportunity to pursue those goals.

The exercises regarding strengths and resources conducted in the eighth session were also found to be beneficial for the participants. The aim of these exercises was to strengthen the healthy part of their self and thus empower them to pursue their life goals despite mood fluctuations. Joyce and colleagues (Reference Joyce, Tai, Gebbia and Mansell2016) also emphasized that strengthening the healthy part of the self is an important aspect of psychotherapy for individuals with BD. Various researchers have suggested that focusing on strengths leads to a decrease in stress and an increase in positive emotions in the long-term (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, Reference Sheldon and Lyubomirsky2006; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Linley, Maltby, Kashdan and Hurling2011) as well as better sustainability of psychological well-being (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Snippe, de Jonge and Jeronimus2016).

With regard to self-awareness, participants reported that as a result of group therapy, they started to observe their own behavior, became more aware of their emotional and interpersonal needs, and started to take the necessary steps to achieve their life goals. Their increased awareness of what is happening ‘in the here-and-now’ might have helped them to better evaluate the changes in internal state and manage their reactions and behaviors accordingly. Consequently, participants might have developed a capacity for emotional tolerance. This finding is in parallel with studies conducted by Russell and Browne (Reference Russell and Browne2005), Chadwick et al. (Reference Chadwick, Kaur, Swelam, Ross and Ellett2011) and Joyce et al. (Reference Joyce, Tai, Gebbia and Mansell2016), which stated that the interoceptive awareness is important for relapse prevention. Moreover, the increase in participants’ self-awareness seems to have a positive impact on their goal-directed behaviors and thus improves their quality of life (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015). Future studies should investigate these effects in the long-term by using a longitudinal research design.

With regard to social support, participants reported that meeting others with similar problems and shared experiences alleviated their feelings of loneliness. These findings are in parallel with other studies, suggesting the positive effect of social contact on recovery (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Powell, Pedley, Thomas and Jones2010) and the importance of social support while taking necessary steps towards positive change (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Suto, Hole, Hale, Amari and Michalak2010). Moreover, Russell and Browne (Reference Russell and Browne2005) suggested that social support is an important factor that helps the overall well-being of an individual.

With regard to self-acceptance, it was found that the 8-week group therapy enabled participants to accept the role of mood swings in their lives. Studies support the idea that acceptance creates higher levels of tolerance for mood fluctuations (Chadwick et al., Reference Chadwick, Kaur, Swelam, Ross and Ellett2011; Joyce et al., Reference Joyce, Tai, Gebbia and Mansell2016; Poole et al., Reference Poole, Smith and Simpson2015). Chapman (Reference Chapman2002) and Russell and Browne (Reference Russell and Browne2005) emphasized the positive effect of acceptance on dealing with the challenges of illness and sustaining psychological well-being.

Finally, it was observed that 8-week group therapy had a positive impact on participants’ self-perception. The current findings support results of previous studies as Higginson and Mansell (Reference Higginson and Mansell2008) stated that experiencing positive change in the way a person with BD views themselves despite adversity has a positive impact on their self-perception. Participants reported that completing treatment and sticking to the programme made them feel good about themselves. In this way, participants broke the vicious cycle and started to take a step in the right direction (Alsawy et al., Reference Alsawy, Mansell, Carey, McEvoy and Tai2014; Higginson et al., Reference Higginson, Mansell and Wood2011; Mansell, Reference Mansell2005). This change in their self-perception might bolster the healthy part of their self and lead to internal reorganization (Mansell, Reference Mansell, Grant, Townend, Milhem and Short2010; Mansell and Hodson, Reference Mansell, Hodson and Stopa2009; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Brawn, Griffiths, Silver and Tai2015).

Recommendations for future studies

The exclusion criteria of ‘suicidal thoughts,’ which are very common amongst individuals with BD who are currently depressed, may have limited the generalizability of the current study findings and may have excluded individuals with BD, who may have derived greater benefit. Future studies should consider including participants with suicidal ideation if they do not currently require a crisis intervention.

Drug compliance should not be ignored when studying patients with BD. Using a psychometric tool that evaluates drug compliance could control for the level of medication adherence on the clinical effect of intervention. Moreover, research validity can also be improved by adding participants from different treatment centers, socioeconomic cultures, and course of the disorder into the research sample.

With regard to comparing pre-test and post-test of hypomanic attitudes, the Client-HAPPI could have been used as an additional instrument. Mansell and colleagues developed a shorter individualized version of the HAPPI, namely the Client-HAPPI, to identify and observe the change in most important cognitions for each participant (Searson et al., Reference Searson, Mansell, Lowens and Tai2012). If the Client-HAPPI is utilized in future studies, a clinical significance regarding each participant’s individual change, which is between their pre-intervention and post-intervention scores of important cognitions, might be detected.

A clinically significant change between pre-test and post-test scores of psychological well-being and life satisfaction might be found if different instruments are utilized in future studies. With regard to assessing psychological well-being, the Turkish version of the Multi-dimensional Psychological Well-Being Scale (MPWS) (Akın, Reference Akın2008; Ryff, Reference Ryff1989) could have been utilized instead of the PWS. The MPWS is a multi-dimensional scale and consists of 84 items compared with the PWS, which consists of eight items. As the MPWS assesses an individual’s psychological well-being in six dimensions, using this instrument might be more useful to detect the clinical significance regarding participants’ pre-intervention and post-intervention scores of psychological well-being. For instance, participants’ higher post-test scores in ‘purpose in life’ subscale could indicate that the 8-week ICM-based group therapy intervention may help participants identify and reevaluate their goals in life and improve their sense of directedness as a result (Ryff and Keyes Reference Ryff and Keyes1995).

With regard to assessing life satisfaction, the Adults Life Satisfaction Scale (ALSS) (Kaba et al., Reference Kaba, Erol and Güç2018) might be utilized instead of the SWLS in future studies. The ALSS is a multi-dimensional scale and consists of 21 items compared with the SWLS, which consists of five items. For instance, participants’ higher scores in ‘satisfaction with self’ subscale of the ALSS would indicate that the intervention may help participants increase their feelings of self-worth and have a better connection with their ‘healthy self’ (Kaba et al., Reference Kaba, Erol and Güç2018; Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007).

Future studies may also incorporate positive psychology (Wood and Tarrier, Reference Wood and Tarrier2010) to investigate participants’ resilience, flexibility, self-compassion and creativity. This approach may allow participants to gain new perspectives, take responsibility for their recovery and focus on their healthy parts instead of their BD diagnosis (Joseph and Sagy, Reference Joseph, Sagy and Mittelmark2017).

Conclusion

The current research attempted to investigate the effect of an 8-week ICM-based group therapy using a mixed methods design (quantitative and qualitative methods). Although the effectiveness of the model was shown in case studies (Joyce et al., Reference Joyce, Tai, Gebbia and Mansell2016; Searson et al., Reference Searson, Mansell, Lowens and Tai2012), this is the first attempt to investigate it in a group format. Moreover, much of the literature on group therapies for BD has focused solely on the outcomes (e.g. Castle et al., Reference Castle, White, Chamberlain, Berk, Berk, Lauders and Gilbert2010; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Cheniaux, Range, Versiani and Nardi2012). The current research focused on the outcomes by investigating the clinical symptoms and psychological processes as well as the process by exploring participants’ experiences at different periods of time. Finally, as the current research investigates qualitative data of participants’ experiences during and after the intervention, it provides an additional contribution to the literature.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Dr Warren Mansell for his valuable feedbacks and suggestions.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hacettepe University Clinical Research (decision number: GO 16/216-08).

Key practice points

-

(1) The 8-week ICM-based group intervention will help the individual with BD become more aware of their conflicting appraisals and exaggerated attempts to control their internal states and pursue their life goals despite changes in mood.

-

(2) The group intervention will enable participants to accept mood fluctuations and their BD diagnosis as well as encourage them to think about their different self-states and integrate them to build a healthy self.

-

(3) Talking about strengths and resources in the group intervention will help participants to manage their daily activities effectively and make them more resilient to mood dysregulation.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.