INTRODUCTION

In 2005, a small chalcedony female head, just shy of two inches high, sold at Christie’s in London for $119,000 (adjusted to 2017 dollars).Footnote 1 The catalogue described it as an eighteenth-century A.D. or earlier piece. Three years later, the same item resurfaced in New York where Sotheby’s hammered it as a classical antiquity for $962,500, an increase of almost 10 times the prior sale price. This time, the catalogue described it as a Hellenistic/early Roman Imperial piece originating in the second century. In 2005, the Christie’s catalogue did not label it as a genuine antiquity, and, due to that misattribution, it not only suffered potential foregone sales of nearly $850,000 and reputational harm, but it also exposed itself to liability toward its consignor and kept a rare and important object in the shadow of scholarly knowledge and truth.

Sleepers are works of art whose characterization is revised—for any of several reasons in any of several ways—with a resulting increase in price.Footnote 2 The quintessential notion of a sleeper is an overlooked masterpiece by a famous artist that is at first considered to be by a lesser-known painter but is eventually discovered for what it really is; the price grows by an order of magnitude overnight. For the purpose of this article, a sleeper antiquity is a particular type of sleeper whose characterization changes in a particular way: it is sold first with a non-ancient attribution and subsequently sold as being ancient.Footnote 3 More generally, when appraising an object, auction house experts identify its attributes such as the creator, period, location of creation, and its provenance.Footnote 4 Any of these elements may have attributions that change and produce a sleeper, or they may also change in a way that reduces price.Footnote 5 This article focuses on a narrow category of objects for which changes in the attributed date re-categorize the piece as an antiquity instead of an antique or a replica.

The subgroup of sleepers studied here has important legal considerations that merit the separation consideration accorded them—they highlight the critical, but fraught, connection between an object’s saleability as an antiquity and its market value. The evidence supporting a label of “antiquity” versus “antique” often rests on the object’s ownership history (listed in auction catalogues as provenance and referred to as such in this article), which in turn links the object’s attributed date to the question of whether it can be traded legally.Footnote 6 To use the example of the chalcedony head described above, the attribution of its date changed from the eighteenth century to the second century thanks to an interim sale by a private dealer who purported to clarify its authenticity once and for all. Thanks to a well-established expert’s opinion, it thereby not only “became” an antiquity in the eyes of the market but also was subject to a different set of laws. Therefore, the attribution of an antiquity as such is intimately linked to the object’s market value and its market liquidity, not to mention its art historical interest.

The connection between provenance and legality is widely studied, and there is growing research on the relationship between provenance and price.Footnote 7 But there has been virtually no scholarly discussion of the implications of an object’s attribution as an antiquity versus an antique. As the analysis shows, there are potentially countervailing effects here, with the “awakening” of a sleeper raising its market value but potentially hindering its ability to be sold. This raises the question of whether the full disclosure of everything known about an object is always in the best interest of consignors and auctioneers. Are there situations in which one party has the incentive to hide evidence that something is an antiquity? Are there situations in which one party may hide disagreement regarding an attribution? What about accidental misattributions; are auction houses or experts liable to consignors in such cases? Should they be? And of all the theoretical scenarios, do any actually occur in reality?

These questions are at the core of this article, which provides a legal and economic analysis of sleeper antiquities as a concept, supported by 12 case studies of real sleepers that have come to market in recent years. The analysis starts from the assumption of sleeper antiquities as a theoretical possibility—namely, a sleeper is an object that is first offered for sale without an ancient attribution and then later is offered for sale with one. The analysis remains agnostic about why sleepers arise on the market and, instead, treats the underlying mechanisms and their implications as the main research focus: why might sleeper antiquities arise and what do those pathways say about the market?

The analysis is divided into two parts: legal and economic theory and evidence from case studies. First, the article outlines the legal and economic incentives to perform due diligence and to publicly reveal information that “awakens” a sleeper. Overall, this analysis uncovers market incentives that have heretofore been left out of research and policy debate. In particular, incentives to perform due diligence may not always work in the direction of producing transparent, full disclosure of an object’s attribution. The legal analysis discusses how combinations of international export laws and contract law may disincentivize all of the concerned parties to perform due diligence or to “awaken” a sleeper upon discovery. The analysis focuses on the requirements of UK and US law since all of the case study objects are sold in those jurisdictions. It details the potential courses of action available to consignors when auction houses trade their property without performing the required due diligence, and it also discusses the implications of sleepers in the context of illicit trade. Most antiquities must comply with extensive legal requirements before they are traded on the international art market in order to verify that they are not the product of recent illegal excavations. Such requirements are not applicable if the object is attributed to a later period. Building on the legal analysis, the economic analysis argues that incentives to deliberately misrepresent a sleeper will differ depending on how much an awakened sleeper would be worth.

Second, based on the analysis of market incentives, the article classifies reasons that sleepers may arise in the market based on why they were originally overlooked and why they were awoken. The 12 case studies are grouped and discussed according to how well they appear to fit each category, providing a comparison for why different types of evidence point to different reasons for the awakening of sleepers. In some cases, experts may genuinely disagree on an attribution or they may make mistakes. Sometimes there is insufficient evidence to make a determination until further research provides more information. Yet other cases potentially involve the deliberate lack of disclosure of information. One hypothetical possibility is that an owner hides evidence that an object is an antiquity in order to transit the object out of the country. Possible examples of this phenomenon occur when the first sale of the object as a replica happens in Europe, where the antiquities trade is governed by strict export restrictions, and genuine antiquities are often denied an export license. The identity of the objects as antiquities is “uncovered” once such pieces reach the New York market, where higher prices can be obtained once the objects have left the country of origin. The reverse situation is one where the auction houses may hide disagreement about an antiquity’s authenticity by failing to disclose that it was previously offered for sale as a replica.

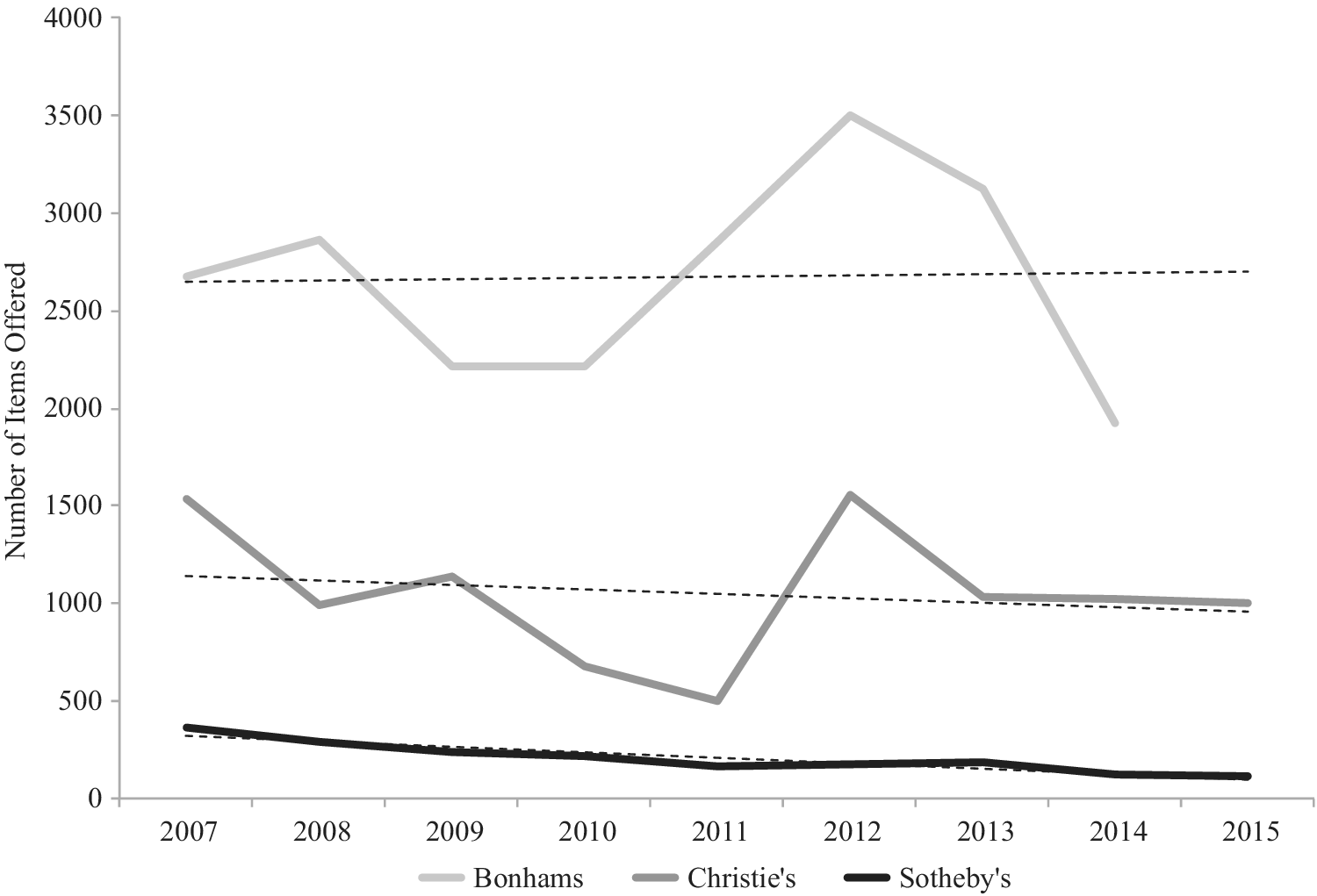

The 12 case study objects were identified in a database encompassing all antiquities sold by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams in London and New York from 2007 to 2015. It is important to note that this study only focuses on the antiquities traded through public auctions because their records are published. Even though details on antiquities sold through dealerships or other private entities would enhance the scope of this article, they were not accessible to the authors. Nevertheless, the problems that this article uncovers, including the exploitation of legal loopholes to export ancient objects out of their countries of origin, would be applicable to the private market as well.

To support the broad conclusions regarding market incentives and mechanisms, the case studies are evaluated within the broader context of antiquities sold at auction in recent years. Data from the thousands of auction sales in which the case studies were identified serve to highlight the general fact that better-provenanced objects achieve higher prices and that some of the top auction houses have invested in performing more and more due diligence over the last decade.Footnote 8 The patterns importantly also indicate that prices for genuine antiquities that can be achieved in New York greatly surpass those obtainable on the London art market, highlighting the incentive to move objects across the Atlantic.Footnote 9

It is important to note that the analysis does not make conclusive claims that any given sleeper was awakened for one reason or another. Rather, it describes the information provided in auction catalogues during the first sale of each sleeper versus the second sale and explains why the evidence could or could not support a particular mechanism being the cause. We do not claim, in particular, that any parties were definitely colluding to export sleepers or to hide disagreement about an attribution. But the legal and economic analysis shows that such actions could be rational and deliberate under particular conditions.

It is also important to note that the analysis focuses on market value since the legal and economic analysis focuses on incentives to perform due diligence and to be transparent about provenance research—activities that are rewarded in the form of price at auction. But there are other forms of value that are affected by provenance research, including art historical knowledge and, in the rare case that an object can be linked to its find-spot, archaeological or scientific value.

In light of the theoretical framework and the case study evidence, an overarching conceptual question of this article is whether the rules of the art market (including antiquities) should resemble the ones of conventional goods. Laws and policies that regulate the latter are straightforward when export or authenticity issues arise. Sellers in most secondary markets can take advantage of clear export requirements and the predictable applicability of tort law. Part of the reason for this is that information about such markets is more transparent overall. The art market has for a long time been treated differently: it lacks clear rules about what records are required for import or export licenses, and this fact, in turn, has produced an outstanding number of objects without sufficient provenance to meet museum collection standards, also known as “orphans.”Footnote 10 It has no standards on the licensing of art market professionals, which are mostly self-appointed, and there is no comprehensive database of stolen artworks, which is replaced instead by large numbers of somewhat arbitrary sampling efforts.Footnote 11 This article highlights certain aspects of more conventional markets that may provide a basis for addressing some of the loopholes identified in the legal analysis.

In arguing that the market does not fully incentivize transparency regarding an object’s attribution and provenance, the article relates to a broader debate about whether the antiquities market successfully induces due diligence in the form of higher market price. Peter Cannon-Brookes, Lisa Borodkin, and Patty Gerstenblith have suggested that participants in the antiquities market would pay a premium for provenanced objects.Footnote 12 Silvia Beltrametti and James Marrone provide empirical support for this hypothesis, arguing that court cases in the early 2000s triggered a market premium for Egyptian and Classical antiquities with good provenances.Footnote 13 James Marrone shows that this pattern, however, is complicated by the tendency to auction antiquities in large groups, or lots, which is how most objects with poor provenances are auctioned.Footnote 14 Neil Brodie argues the opposite, using data from selected antiquities auctions to show that buyers did not consistently reward provenance and that the market will therefore not regulate itself.Footnote 15 This article does not take a direct stance on the question of so-called “auto-regulation.” Rather, it complicates the link between provenance research and market transparency by arguing that full transparency of expert opinion and provenance information is not always incentivized, resulting in actions that could either raise or lower the perceived value of an object, depending on the situation. Therefore, the article indirectly argues that, while the market may reward provenance on average, in particular cases it does not automatically reward full transparency of information that would be relevant to both buyers and the public.Footnote 16

The article proceeds as follows. The second section discusses the legal framework, including export issues, repatriations, and liability in tort for failing to recognize a sleeper; the third section presents a model of economic incentives to perform due diligence to uncover sleepers; the fourth section applies the model to 12 sleeper case studies of antiquities; the fifth section evaluates the findings in the context of a decades’ worth of market data from antiquities sales; and the sixth section concludes with implications of the analysis.

DEFINITIONS AND LEGAL BACKGROUND

As already noted, for these purposes, the definition of a sleeper is somewhat narrow: a sleeper is an object that is reattributed as an antiquity when before it had been offered for sale as an antique or a replica. By “attribution,” we mean the date of the object as characterized at the time of sale, which may or may not be backed up by some evidence. The very concept of a sleeper requires an “awakening.” The awakening is the change in attribution. A key point, and one emphasized throughout the legal analysis, is that attributions are not wholly scientific or objective. Awakening a sleeper does not mean that the object has suddenly been dated with 100 percent certainty, and this lack of certainty is part of what creates a legal gray area.Footnote 17 As we describe in more detail below and exemplify through the case studies, provenance research can be critical in supporting the claim that an object is actually an antiquity. The point is that the market behavior we observe is based on the information backing up the attribution and the liabilities associated with making the attribution in the first place.

The elements of an antiquity’s attribution can be grouped into two categories: quality descriptors and provenance. Analyzing the quality of an antiquity, including its authenticity as an antiquity, involves examining the techniques used to produce the object and evaluating them in light of art historical references.Footnote 18 The operation is usually conducted by trained specialists, and the analysis begins with the assessment of the composition and the iconography of an artwork or antiquity, which are then compared with recognized works from the same period, and results in a determination about whether a work was made in such period.Footnote 19 Such eye judgments about the quality of an artwork are in most cases a matter open to debate, and different experts can, and often do, hold different opinions.Footnote 20 The case of Hahn v. Duveen was the first to formally question whether the identification of an artwork should be controlled by the aesthetic judgment of a small group of experts or whether more rigorous methods, including scientific authentication, should be employed.Footnote 21 In this case, the court held that the moral honesty and the methods of attributions of some experts were too subjective and therefore unsound, and also that in some instances the finding of an overarching truth would not be possible.Footnote 22

The use of forensic methods can help overcome subjectivity and corroborate attributions by testing the materials used to make the artwork.Footnote 23 In the context of antiquities, radiocarbon dating can help determine the age of organic material, and isotope analysis can match marble objects to specific geographical locations.Footnote 24 Dendrochronology can do the same with wood.Footnote 25 Thermoluminescence is helpful to date pottery, and paints can be tested by sophisticated pigment analysis.Footnote 26 Scientific tests are helpful at determining whether an artwork’s materials come from a certain time and place. However, such tests are not foolproof. For example, the surface of stone, as well as other materials, can be weathered artificially to simulate the effects of long-term wear and deterioration, leading modern replicas to be confused for ancient objects.Footnote 27 The fact that even scientific evidence may prove inconclusive is best illustrated by the statue of a Kouros owned by the J. Paul Getty museum, an imposing marble statue of a youth whose attribution and identification remains a mystery to this day.Footnote 28 The Getty’s website states that the statue is carved from marble that originates from Thasos, but it also notes that the use of such marble is unusual for the time the piece was purportedly sculpted.Footnote 29 The object details read: “Kouros, Greek about 530 B.C. or modern forgery.”Footnote 30

When quality judgments are debatable, and scientific evidence proves inconclusive, information tracking an object’s ownership history can be of crucial importance to finding out whether the objects at issue are genuine antiquities or belong to a different period.Footnote 31 Verifying provenance involves researching the ownership history of a given artwork, including records documenting its past whereabouts and possessors.Footnote 32 Even though the importance of researching provenance has been extensively recognized, and the work of many art historians includes references to the prior ownership of specific artworks, there have been relatively few efforts that engage in the systematic and methodical study of provenance.Footnote 33 The case studies in this article provide examples of how provenance research has been used to support the reattribution of an object as an antiquity. Provenance research is not only a useful way to enhance scholarly knowledge by confirming attributions and verifying the authenticity of antiquities, but it has also become an essential legal requirement that enables legitimate sales.Footnote 34 A more elaborate discussion of the legal principles underlying the international trade of ancient art follows below and shows that efforts to uncover solid ownership chains are often rewarded with the acquisition of objects that carry clear title.

Export Issues and Repatriations

This section discusses the legal environment in which the antiquities market operates and addresses specific legal issues associated with the illicit trade of such objects. This will help clarify why sellers may want to turn a blind eye as to whether an object is a genuine antiquity in order to bypass export rules and compliance schemes that apply to the trade of ancient pieces. One of the main issues that arises in the context of the antiquities trade is the possibility that an object is the product of an illicit excavation and that it has been stolen from its country of origin.Footnote 35 If a country has passed national ownership laws providing that the ruling government owns antiquities found in its territory, and if such antiquities are traded across borders without official authorization, they amount to stolen property and can become subject to a restitution claim.Footnote 36 If the object at issue is a later imitation of an antiquity, it faces fewer constraints when crossing borders as most of the laws discussed below apply only to genuine archaeological material.

The trade of ancient art triggers the applicability of numerous national as well as international laws. At the international level, the illicit trade of archaeological material infringes on the standards set out in the 1970 UNESCO Convention.Footnote 37 The latter commits its 140 signatories to enact national laws to seize illegally exported objects found on their territory and repatriate them to their respective countries of origin.Footnote 38 Importantly for the context of the present study, the United States and the United Kingdom, the countries where the most important antiquity auctions take place, as well as Italy and other source countries from which the sleeper antiquities we have identified originate, are all subscribers to the UNESCO Convention, and have passed national laws that condemn the theft and illicit trade of cultural heritage.Footnote 39

Regulation of the US Antiquities Market

The United States, which hosts the world’s largest market for high-end antiquities, implemented the principles contained in the 1970 UNESCO Convention through the passage of the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA) in 1983.Footnote 40 The CPIA sets up a system of import controls for ancient material regulated by bilateral agreements entered into with individual source countries.Footnote 41 For instance, in 2001, the United States entered into a bilateral agreement with Italy that restricted the import of broad categories of ancient objects.Footnote 42 In practice, the presence of such agreement allows US customs to seize archaeological artifacts that are being imported without documentation verifying that the object can legitimately be traded.Footnote 43 As a consequence of the bilateral agreement with Italy, auction houses wishing to sell classical antiquities in the United States had to formally declare that the consignments had been outside of Italy before the bilateral agreement came into force in 2001 or otherwise submit valid export documentation.Footnote 44

The requirements became stricter with the passage of time, especially since the 2005 decision in Italy v. Medici, which required antiquities to showcase a verifiable pre-1970 provenance in order to be traded.Footnote 45 This was meant to discourage the sale of recently looted objects. The case of Medici, which ultimately condemned an Italian antiquities dealer to a 10-year prison sentence and a €10 million fine for trafficking looted objects, also uncovered evidence that enabled the Italian government to track hundreds of objects that Medici had sold to prominent US collectors and claim their return.Footnote 46 By choosing to pursue the return of objects that left its grounds illegally after 1970, Italy endorsed the threshold date set by the UNESCO initiative instead of relying on the date in the bilateral agreement or other laws.Footnote 47 By establishing a new legal standard for the trade of classical antiquities, the Medici decision affected prices paid for well-provenanced objects on the antiquities market, and, in its aftermath, many museums worldwide adopted acquisition policies recognizing 1970 as the applicable reference date.Footnote 48

Another legal route to punish traffickers once the object in question has entered the United States is through the applicability of the National Stolen Property Act (NSPA).Footnote 49 The case of US v. Schultz, which was successfully pursued in the New York Federal Court in 2003, clarified the rules applicable to the trade of looted Egyptian material.Footnote 50 The court supported Egypt’s claim to the trafficked objects by holding that an Egyptian law passed in 1983 had successfully vested its government with their ownership before Frederick Schultz took them out of the country in the 1990s. Instead of referring to the CPIA or bilateral agreements, the court ruled that US theft laws could be applied to property stolen abroad if the foreign country had previously asserted its ownership rights to its cultural patrimony. The Schultz decision bound all state and federal courts in the United States to apply the 1983 threshold date in connection with recovering illicitly traded Egyptian antiquities located on US territory and affected the practices of antiquities departments of auction houses in a major way. Whereas prior to this decision the provenance of Egyptian antiquities was of little relevance, after the Schultz decision active steps were taken to corroborate the pre-1983 ownership history of such consignments.Footnote 51

To summarize, in order to import and sell ancient art in the United States an auction house must comply with strict import requirements, including filling in detailed customs forms, providing details as to the country of origin of the piece, and obtaining notarized statements from the consignors in relation to its ownership history.Footnote 52 Failure to do so can result in the seizure and forfeiture of the object.Footnote 53 Starting in 2012, consignors were further required to submit supporting evidence to verify the origin of the object, such as publications, photographs, prior sale receipts, and insurance or inheritance records.Footnote 54 Since clearing ownership of antiquities became an increasingly difficult task, auction sizes in New York have drastically decreased over time, and auction houses are known to have to regularly pull objects out of upcoming auctions as a result of potential repatriation claims.Footnote 55

Regulation of the UK Antiquities Market

A considerable number of classical antiquities sold in the United States were previously traded through the UK art market. In fact, 10 out of 12 of the sampled case studies discussed in detail in this article were first sold in the United Kingdom as Roman-style or eighteenth-century objects and subsequently traded as genuine antiquities in New York. The presence of antiquities in the United Kingdom can be explained in several ways. First, the United Kingdom is itself the find-spot of a number of classical antiquities from former Anglo Saxon Roman colonies, which can be legitimately traded internationally if local museums are not interested in acquiring them at their market value.Footnote 56 Besides being a source country, the United Kingdom is also a market country and has endeavored to create a favorable market environment for the trade of artwork, including antiquities, which we elaborate on below.Footnote 57

Another category of antiquities available in the United Kingdom consists of acquisitions made by the English nobility during extended journeys throughout Europe known as the “Grand Tour.”Footnote 58 These trips, which were in vogue from the late seventeenth century until the early nineteenth century, were mostly motivated by exposure to classical culture and the study of the legacy of the ancient world; Italy and Greece were popular destinations, and visitors who wished to buy ancient objects were able to do so with the help of local dealers that arranged for export licenses and transportation.Footnote 59 Busts and marble statues from the Imperial Roman period were particularly popular and would be prominently displayed on the estates of their collectors.Footnote 60 Of particular interest is the fact that these objects were sometimes restored to please the taste of their owners or integrated into furniture and other decorative components, and, as we will see later in this article, they are sometimes still traded in that form, which partly explains their “sleeper” status. Either way, objects collected during this period are some of the safest antiquities on the market because they were documented to belong to established collections outside their country of origin long before national patrimony laws became applicable.

UK import and export regulations differ according to whether the object is categorized as archaeological material or merely as an antique. The latter is defined as a decorative object 100 years or older that is not the product of an archaeological excavation.Footnote 61 According to such regulations, archaeological material can only be exported by means of a formal license, and the application to export must include information about the object’s country of origin, its provenance, and, at times, a statement by the art loss registry acknowledging that the object was not stolen.Footnote 62 On the other hand, if the object is categorized as an antique, and it is valued at less than €50,000, it can be exported and traded without a license.Footnote 63 It follows that if antiquities are misidentified as antiques and their value does not reach the €50,000 threshold, they can be freely exported to venues where they can be resold for higher prices. In New York, for instance, prices for antiquities are particularly high because demand is strong and supply is low.Footnote 64 Several of the cases we observe below involved items that were first traded at auction in London as relatively low-priced decorative antique objects and, once they reached the New York market, were offered for sale as genuine antiquities.

This section has shown that, in order to be legitimately traded, most antiquities must comply with extensive legal requirements and that the latter are not applicable if the object is traded as a later imitation. The fourth section of this article will distinguish situations in which sleepers are purposefully created to escape the tight regulations from those wrongful attributions that result from innocent errors. Regardless of whether there is malice at play, the above discussion has exposed a legal loophole, which allows sleeper antiquities to bypass regulation that would otherwise inhibit their trade. Such circumvention of legal standards may raise questions of legitimacy at future sales. The following section will illustrate that undertaking provenance research is the most effective way to prove that a piece was not recently looted and that there are no relevant export issues.

Liability for Failing to Recognize a Sleeper

Recently, some courts have recognized the importance of performing due diligence, including provenance research, in order not only to make determinations about the authenticity and attribution of an artwork but also to prevent claims for illicit traffic.Footnote 65 However, it is not necessarily clear to what extent experts can be liable for wrongful identifications. This section of the article provides an examination of the current case law in the United States and the United Kingdom concerning misattributions made by auction house specialists since the case studies discussed in the next section are sold through auctions in these locations.

Before inspecting the relevant law, it is important to clarify the role of the various stakeholders involved in the auction process. Auction houses are agents for consignors who wish to sell their property at auction, and, by entering into a consignment contract, the auction house agrees to act in the consignors’ best interest and sell the artwork to the highest bidder.Footnote 66 Even though they are often in possession of the property in order to showcase it to potential clients before a sale, auction houses do not own the object themselves.Footnote 67 In short, they have the authority to bind the consignor and the purchaser to a sale without being themselves party to it.Footnote 68 Auction houses generally have wide discretion as to how to market the objects in question, including deciding on attribution and quality. In case the object is misattributed or otherwise found not to correspond to the descriptions outlined in the sales catalogue, a buyer is entitled to rescind the sale.Footnote 69 This is unlikely to happen, however, in the case of a sleeper because the object will often be revealed to be more valuable than advertised and the buyer will be incentivized to keep it or resell it at a higher price. The likelier outcome of a sleeper sale is that the consignor will sue the auction house to seek redress for the undervaluation of the consigned property.

In the United States as well as in the United Kingdom, a duty of care arises in the context of an agency relationship when a professional is hired to perform a task in which he is purportedly an expert.Footnote 70 The present scenario arises when an auction house appraises the goods of a consignor.Footnote 71 What the relevant standard of care comprises has been addressed in a multitude of cases, and even though every case is different, it appears in principle that consignors are entitled to expect a transparent and competent service and the exercise of skill and care when evaluating consigned property.Footnote 72 This includes an accurate description of the item in the sales catalogue and the disclosure of other relevant information that may affect the sale.Footnote 73 Compliance with the above duties is assessed according to what a comparable auction house of similar size and expertise would have done in that same position, without the benefit of hindsight; provincial auctioneers do not have to meet the more rigorous standards of care of specialists at major international auction houses, where the expectation is that an artwork will be assessed by highly qualified staff.Footnote 74 In short, if a competent professional at a similar auction house would have reached the same conclusion under the same circumstances, the standard of care will generally be met.

A typical claim for breach of fiduciary duty involves a claimant arguing that the auction house negligently misrepresented the subject matter of the sale, thereby failing to comply with its duty to care.Footnote 75 To successfully bring such a claim, the consignor needs to show that he trusted the skill of the expert, that he did act based on the expert’s advice, and, as a result, that he suffered financial loss. He also has to file the claim in a timely manner.Footnote 76 In Cristallina v. Christie’s, the New York State Appeals Court held that acting negligently in providing estimates can give rise to a claim and that consignors have the right to see their property promoted to its full potential.Footnote 77 The latter would be applicable in the case of a sleeper, given that the undervaluation will lead to lower estimates, incorrect sale placements, and missed opportunities for better promoting the sale of the object. In the UK case of Coleridge v. Sotheby’s, the court decided that the wrongful dating of a gold necklace that resulted in a lower sale price, albeit not per se negligent, allowed the claimant to request damages for the amount of the undervaluation as determined by an external expert appraiser.Footnote 78 Sometimes, however, there may be genuine disagreement about the true nature of an artwork and insufficient evidence to make a determination, in which case the auction house will not be held liable. In Thwaytes v. Sotheby’s, the court held that the Sotheby’s specialist was not at fault for attributing a painting to a follower of Caravaggio, instead of Caravaggio himself, because there was genuine disagreement between experts as to the actual attribution.Footnote 79 In summary, auction houses may be found liable for negligence if they make erroneous attributions that another auction house of similar competence would not have made.Footnote 80

One important caveat concerns warranty disclaimers contained in consignment contracts, as they can limit the above negligence claims.Footnote 81 In short, disclaimers contained in consignment contracts release auction houses of liability in connection with the “correctness of descriptions” of the consigned properties.Footnote 82 In their standard form, they provide that auction houses have complete discretion as to decisions pertaining to the sale, including attribution, pricing, and all details about the object contained in the sales catalogue.Footnote 83 In order for a claim to be successful, consignors need to overcome the barriers imposed by such disclaimers, which is not always an easy task, as most common law courts have construed the scope of fiduciary duties to fall within the boundaries of the substance contained in the consignment contract.Footnote 84

Notwithstanding the presence of a disclaimer excluding liability for artwork misattribution, an action for fraud or reckless disregard as to the attribution remains available. This type of claim becomes actionable when the incorrect statements are material and were made with knowledge or reckless disregard of the inaccuracy.Footnote 85 Materiality (in the legal sense) ensues from the difference in value of the sleeper before and after its “awakening”: usually the price difference is such that the seller will be deprived of the very substance of the transaction if the attribution is not fulfilled. Proving that the auction house knew that the attribution was wrong or that it had no basis for making the representations is possible but rare, as auction houses can argue that they were themselves deceived about the true identification of the object.Footnote 86 This raises the question about what a reasonable auction house specialist is entitled to believe and where reckless disregard begins. New York courts have determined in some instances that dealers can be liable for selling misattributed work because the attribution is presumed to be the basis of the transaction and an express warranty of authenticity, according to the New York Art and Cultural Affairs Law.Footnote 87

Alternatively, the consignor can claim that the sale should be void because both parties were mistaken about the object’s true identity. Under US as well as UK law, a mistake must generally concern a material term of the contract, and it must be mutual in order to render a contract void.Footnote 88 In the case of a sleeper, the consignor has entrusted the auction house with the sale of an object that is much more valuable than he thinks, and, given such difference in value, the mistake is likely to have a sufficiently material effect. Given that both parties would gain from the uncovering of the sleeper, the mistake is presumed to be mutual. Even though such doctrine has limited applicability, mostly because contractual terms often require performance of the sale despite a mistake, this cause of action was successful in Richard Feigen & Co v. Weil, where both parties intended to transact a Matisse drawing, but the fact that they were both mistaken about the true nature of the drawing made performance of the contract impossible.Footnote 89

Last, statutory consumer protection laws can be helpful for some consignors. Under UK law, a disclaimer clause for attributions may be challengeable if an inexperienced seller enters into a standard consignment agreement containing a preformulated broad disclaimer. The disclaimer would likely be held to be unfair because it would go against the auctioneer’s fiduciary obligations and would therefore fail to comply with the reasonableness test set out in the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1997 as well as the requirements contained in the 2013 European Union Directive on Unfair Terms and Consumer Contracts.Footnote 90 Even if there is ample scope for arguing that consumer protection laws will apply in sleeper situations, no case law has verified whether that is the case in connection with auction house disclaimers to this date.Footnote 91 The situation is different in the United States, where it is authenticators that usually need protection from claims. In 2016, following a wave of lawsuits that resulted in an overall silencing effect of appraisers for fear of being sued, the New York Senate passed a bill to protect good faith authenticators from liability for making attributions.Footnote 92 The bill provides that only “valid, verifiable claims” against authenticators will be allowed to proceed in court and that authenticators will obtain financial compensation for their legal expenses if they win, but it still needs to be approved by the New York State Assembly before it becomes law.Footnote 93 It is unlikely that such a bill will interfere with claims based on misrepresentation or other breaches of fiduciary duties; however, it highlights that the market needs a functioning mechanism to address authenticity in order to stay alive.

This section has examined the courses of action available to consignors in the event of a sleeper sale. They may proceed in several ways depending on where and when the transaction took place and may be awarded a remedy if the attribution was made without performing proper due diligence.

A MODEL OF INCENTIVES TO PERFORM DUE DILIGENCE

This section builds on the legal analysis to model the economic incentives for market participants to respond to the risks of misattributions. It presents a model in which auction houses, in order to avoid legal claims based on negligence or the lack of compliance with export regulation, can protect themselves from unwanted outcomes by performing due diligence. Due diligence will help uncover sleepers and result in higher prices for the consignor and agent. But, depending on the location and circumstances of a potential sale, there may be incentives to deliberately cover up the true attribution in order to more easily transfer the object abroad and to resell it under the true attribution. Conversely, there could be incentives to bolster an attribution’s claim by hiding evidence of expert disagreement.

To illustrate the basic incentives underpinning the model, Figure 1 provides a conceptual visualization of the role of due diligence in the antiquities market. For the purpose of this model, we have relied on the two components of value outlined above: quality (which encompasses technical art historical as well as scientific aspects) and provenance research. Figure 1 relates quality and due diligence to price. The horizontal axis characterizes an object’s intrinsic quality—both physical condition and art historical or archaeological value. The vertical axis characterizes the value or price that the object would receive at auction. The dotted line shows the relationship between these two when there is no due diligence—in other words, it is the value of the object itself without any backstory, ownership records, or demonstrable legality. The solid line shows the maximal increase in value that would occur if the auction house (or seller) invested in due diligence. The price of an object depends on both: higher quality and better provenance both increase price, and the premium for due diligence (that is, the gap between lines) increases with quality.Footnote 94

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the returns to due diligence.

But auction houses face conflicting incentives. While it can be profitable to perform due diligence, it is costly and not worthwhile or practical for every single object. Given threshold dates and prices laid out in national and international laws, as well as the practical constraints on the costs of pursuing lawsuits, it is relatively unlikely that a government would pursue the return of objects on the lower end of the price/quality spectrum, and it is unlikely that a consignor would sue if a sleeper of relatively low value were found to have slipped through an auction house’s authentication process. This is the market segment at the lower left of Figure 1, and this segment is not just hypothetical: as discussed in later in this article, about 15 percent of objects sold in London actually have no ownership date attached to them, meaning that they came to the market with very little, if any, due diligence having been performed.

Performing due diligence to uncover information that helps avoid such claims becomes relevant when the sale of more valuable objects is at issue. Earlier, this article outlined that looting and export issues have caused sales to be prevented and objects to be repatriated.Footnote 95 We have also seen that, in some cases, consignors have a more malign incentive to deliberately create a sleeper by undervaluing an object, moving it to a higher-end market, and “uncovering” its true attribution to earn a higher profit. For example, a seller may wish to transport an object outside of London or continental Europe in order to sell it at a higher price in New York. By selling it first as a replica (rather than moving it to New York directly), it can essentially corroborate the fake attribution and corresponding low valuation (and also the true provenance) on paper, expediting its transfer abroad. In other words, malign intent to misattribute a work is possible if, by revealing the true attribution (that is, the results of due diligence work), the object’s value would have fallen above the threshold requiring export paperwork but, in the absence of such attribution, the object’s value would fall below the threshold. This defines the gray sector in Figure 1. The incentives to do so are present when the potential profit is sufficiently high, but the falsification is still feasible. Even though we should be more concerned about collusive behavior, it is important to note that even the trade of innocently misattributed objects infringes international laws and poses trouble for future sales.

For objects with very high quality, falling to the right of the gray sector in Figure 1, falsifying the results of due diligence work would not feasibly provide cover for exporting an item under false pretenses. Thus, we would not expect the very highest quality items to be susceptible to such maneuvering. However, they are susceptible to a different sort of maneuvering: when high valuations are at stake but due diligence is not conclusive, there is an incentive to hide any disagreement in order to prop up the object’s market value. In theory, this could occur at any quality level, but the benefits are greatest when the valuation differential is largest. So long as the risks are sufficiently low, selling an object’s attribution as more airtight than is true could be very beneficial.

This analysis implies three different due diligence scenarios, which are detailed below. These scenarios are not necessarily mutually exclusive but, rather, serve to highlight how incentives change depending on the physical quality of an object and show that for different types of objects an auction house is likely to make different decisions on due diligence. The descriptions also highlight the approximate alignment with the 12 case study sleepers that are discussed in the next section. The model is meant to provide a conceptual benchmark for the case studies, and so the sectors should be considered relative to each other, not as well-defined market segments with concrete value thresholds. However, for reference, the case studies imply that objects with a low, medium, and high value correspond roughly to the low thousands of dollars, tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars, and millions of dollars.

Due Diligence That Is Not Worth the Cost

Due diligence that is not worth the cost corresponds to the low-quality sector of Figure 1. Objects of unexceptional quality do not merit much due diligence in the first place because a better provenance would not appreciably raise their price, and it is unlikely that such objects would become the subject of a repatriation or private legal claim. As we saw in earlier in this article, in order for a negligence claim to be successful, a consignor needs to show that the consignor suffered a loss as a result of the misattribution. Incentives to perform due diligence or to lie about the ancient attribution in this category are limited because the increased profit is likely to be comparatively lower than for higher-quality items, and the auction house will prefer spending resources on researching the latter. Low-quality objects will be sold without much, if any, provenance research, and previous research shows that cheaper objects tend to have shorter provenance listings in auction catalogues.Footnote 96 This group may yield some sleepers, but since the lack of incentive to study these objects means that authenticity, or lack thereof, may go unnoticed, they will be limited in number. Examples of sleepers in this category include Bonhams krater (Table 1, Item no. 4); Hellenistic head (Table 1, Item no. 5); bust of a poet (Table 1, Item no. 9).

Table 1. Case Study Sleeper Antiquities

Due Diligence to Increase Value

Due diligence to increase value corresponds to the medium-quality sector of Figure 1. For objects in this sector, due diligence can generate enough value to make it worthwhile. Because of this, sleepers are more likely to be discovered in this range, and because there is greater profit at stake (compared to the previous scenario), missing a sleeper would more likely be grounds for a negligence lawsuit. As an example of a large profit forgone from missing a sleeper, see the Bonhams Satyr (Table 1, Item no. 7). In this price range, the information uncovered through due diligence often serves the primary purpose of increasing value by providing a more compelling backstory. Among our case study sleepers, this backstory includes links to the Grand Tour (see Table 1, Items no. 9–12) and to famous collections (see the marble head sold at Sotheby’s in 2007, Table 1, Item no. 6). Due diligence could also resolve expert disputes, where a consensus has not yet been reached as to authenticity (see the head of a satyr, Table 1, Item no. 3; head of a bull, Table 1, Item no. 10).

As the gray area of Figure 1 highlights, it may also happen that when due diligence information is not revealed, objects may be transported out of a country without the proper paperwork because the paperwork was not deemed necessary. This could be due to an innocent mistake—for example, due diligence just was not performed. Among our case studies, a herm and satyr (Table 1, Items no. 2 and 3) achieved nearly 10 times the original price after they were “awakened,” but it does not appear from the evidence that this lack of due diligence was a deliberate effort to deceive anyone about the true attribution.

However, a more malignant intent to deceive or to manipulate the law could also occur. Just as due diligence may uncover valuable information about an object, hiding that information may decrease value. The incentive to hide such information is strongest when moving an object to a different market would drastically change the price, but export issues do impede such movement. When the incentives are in place, a sleeper can be generated deliberately by selling the object under a false attribution to move it to another country, where it will be presented as a newly discovered authentic antiquity. Thus, we predict that such sleepers should have large differences in price and should fall in the upper half of the price distribution. The most egregious example of such cover concerns the chalcedony head (Table 1, Item no. 1).

Due Diligence to Shore Up Legality

At the high end of the market are objects that have exceptional quality and are rarely misconstrued as replicas because their unique features would prevent them from being misidentified in the first place. It is unlikely for sleepers to be found in this bracket, and, indeed, we do not have any examples of sleepers whose value after “awakening” exceeded $1 million, apart from an Egyptian queen (Table 1, Item no. 12), which failed to sell at the asking price. The primary issue in this bracket is not authenticity but, rather, legality: unless these objects were known to reside outside their countries of origin before patrimony laws became applicable, or otherwise left with the necessary paperwork, they would become likely subjects of repatriation claims. Extremely rare objects can be ideal candidates for repatriation claims not just because of their high value but also because they may have distinctive features—which is part of the reason for their high value—that link them to a particular archaeological site. Thus, the incentives to perform due diligence in this market segment are primarily motivated by the need to verify the legality of the object in terms of its sale.Footnote 97

INDIVIDUAL SLEEPER CASES

This section examines 12 sleeper case studies sold at Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams’s regularly scheduled antiquities auctions. As the top-end auction houses, these three auction houses have the greatest resources and incentives to perform due diligence and therefore are most likely to uncover accidentally misattributed sleepers. As with other categories of art, a catalogue is released prior to each sale at an antiquities auction, and this catalogue records information about each lot, including the description of the object, the provenance (where known), and the estimated sale prices (provided as a low/high range in the local currency).Footnote 98

These case studies were discovered in the process of conducting provenance research in a large database comprising all antiquities sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams between 2007 and 2015. As part of the research, the objects’ provenance listings were used to identify which objects had previously been offered at auction. Those previous sale catalogues were consulted, even if they were not antiquities auctions, and the prior sale prices were recorded. The 12 sleepers discussed here were identified when the first catalogue did not list the object as an antiquity but, rather, as a later replica or an original piece from a later period (such as Baroque or Renaissance). These 12 items were all sleepers identified in the data. It is possible that there were other sleepers sold on the market during this time since the catalogued provenance may be incomplete and since antiquities are also sold at other auctions that did not enter the database. There may also be sleepers on the market that have not yet been awakened. Nevertheless, it is also clear that, with only 12 sleepers identified out of thousands of auction sales, this is not a common phenomenon.

We group the 12 sleeper cases into categories based on the three scenarios listed above. In addition to the three scenarios is the possibility mentioned above that an attribution is marketed as more airtight than it really is—namely, some disagreements regarding the attribution are omitted in an auction catalogue. The groupings are meant to provide a framework for understanding the conflicting incentives giving arise to sleepers and for the evaluation of future sleepers in the antiquities market. The categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they do further verify the conceptual model by illustrating the incentive to perform due diligence or to deliberately cover up an attribution.

There is, of course, more to due diligence than just avoiding lawsuits. It is also profitable to gather information on an object for the purposes of raising its value in its own right—and not to necessarily to avoid a claim. Besides being an indicator of an object’s legitimacy, provenance information can directly raise an object’s desirability: museum exhibitions as well as previous ownership by renowned collectors give an object a more prestigious backstory.Footnote 99 Since provenance can affect prices through multiple channels, it is important to characterize both its qualitative aspects as well as its direct evidence of legality. In our case studies, we therefore examine both the lot’s pedigree in terms of exhibits and publications listed in the catalogue as well as the earliest provenance year. More of the former indicate higher-quality provenance overall, whereas the provenance year can be compared to relevant legal benchmark dates and help determine whether an object could be subject to a legal claim. The objects are summarized in Table 1 in the order in which they are discussed.

Overall Lessons from Case Studies

Despite their small number, the case studies show some broad patterns. The average increase in sale price (adjusted to inflation) before versus after the awakening was 336 percent (ignoring those that failed to sell the second time, the increase was 482 percent). This is roughly the market premium for owning an antiquity versus an antique or replica.

The average pre-sale estimate increased by 250 percent before versus after the awakening, indicating that the appraisers were also pricing in the reattribution the second time around. However, the premium (the percentage by which the sale price exceeds the estimate) went down. This is because, during the first sale, some objects sold for much more than the estimate. High premiums are evidence of bidding wars since at least two bidders are required to drive up the price. The high premiums here are evidence of an arbitrage effect at work: discerning buyers may recognize an object as an antiquity, even when it is not labeled as such, and be willing to engage in a bidding war to get a good deal. The buyer could then earn a profit by reselling the object with the new, presumably (in his or her eyes) correct attribution. The average time between sales is 4.3 years, with half of the sleepers being awakened in less than three years. In many but not all cases, those objects that came to market very quickly (in two years or less) do appear to have had bidding wars the first time around, indicating that they may have been identified as potentially mislabeled and purchased for a profit-making opportunity.

The majority of second sales occur at Sotheby’s New York (only two are at Christie’s and one is at Sotheby’s London). Perhaps surprisingly, in the majority of cases, the second auction house omits reference to the prior attribution, even if it references the sale. There is, however, no relationship between the auction house and the tendency to disclose the different attribution from the first auction. Whether or not this omission is deliberate, the upshot in such cases is that the object benefits from having been previously sold by a prestigious auction house, while avoiding a potentially negative appearance of having a controversial attribution. Of course, potential buyers could discover such omissions for themselves if they were to refer to the historical catalogues (after all, that is how these case studies were identified), but the auction houses are effectively placing the burden of due diligence on the buyer.

Given the much higher sale prices associated with the attribution of antiquity versus antique or replica, it is possible that disclosing prior attributions may risk quite a bit of profit if it causes an object to fail at auction. But, even still, only two objects had sale prices that exceeded their estimates the second time around. This is unusual; on average, artworks that find buyers have sale prices that exceed their estimates (see Table 2). The observed patterns in the 12 case studies could be random (especially considering the small sample), but it does suggest that appraisers are overpricing sleepers’ attributions relative to buyers’ tastes. Assuming it is a real pattern, any of several explanations are possible: buyers may be discerning enough to doubt the attribution on their own, or they may have researched the object and discovered the prior attribution. At any rate, they still appear to be paying much more than they would if the object were not attributed as an antiquity.

Table 2. Summary of antiquities market data: 2007–15

Notes: Prices are in 2017 US dollars.

a The threshold is 1970 in London and for Classical antiquities in New York and 1983 for Egyptian antiquities in New York.

b The overall estimate for each object is calculated as the geometric mean of the low and high estimated price.

Misattributions of Low-Quality Objects and Losses Due to Inconclusive Information

As the above model points out, it is rarely worth spending due diligence efforts on low quality objects, as such efforts will only yield low returns and are unlikely to prevent a claim. Misattributions on the lower end of the spectrum are often the result of innocent mistakes made by auction house specialists and do not have a large impact on the subsequent discovery of the true identity of a piece, which means that the consignor will not have much ground for a claim. This happens, for instance, when auction houses offer a sleeper antiquity as part of an estate or decorative art sale, and the experts evaluating the property would not be expected to have expertise in antiquities (nor would they be looking out for such pieces—that is, in a collection of Baroque or Renaissance objects).

One such example includes the sale of a small marble head in Hellenistic style at Christie’s in Paris in 2008, which purportedly dated to the nineteenth century and sold for the unremarkable sum of $2,700 (Table 1, Item no. 5).Footnote 100 It was said to belong to the collection of the Comte and the Comptesse de Paris, a well-known aristocratic family. In June 2009, the object surfaced at Sotheby’s New York with the same provenance, where it sold for 2.6 times the first price.Footnote 101 The head was a minor object, small and not particularly noteworthy to start off with, and this is reflected by the pricing at both sales, notwithstanding the change in identification. A claim by the consignor would not have been worth the price difference that the object achieved on the New York art market the first time around, when it was listed in an estate sale that did not include other antiquities, and the specialists that would have dealt with the sale would not have had much knowledge about them in the first place, nor would the appearance of the object have motivated them to make further inquiries.

Whereas most misattributions in this sector happen by error, this is not always the case, and there are instances pointing to negligent behavior. The sale of an attic red figure krater from the collection of Joseph Klein (Table 1, Item no. 4) is a useful example and shows the boundaries between the two. The Bonhams’s office in San Francisco sold the vase as part of Klein’s collection of Grand Tour objects in a 2012 sale of furniture and decorative arts.Footnote 102 Even though the vase was part of a sale that included almost exclusively decorative objects, the catalogue specifically stated that Klein also owned an important antiquities collection that would be sold through Bonhams’s London branch. This implies that specialists at Bonhams looked at the Klein collection and decided what was an antiquity and what was not before allocating them to their respective sales. A negligence claim could have been appropriate in this scenario because the auction house failed to differentiate between archaeological material and more recent antiques coming from the same collection, which it knew contained a sizable portion of true antiquities. It would have been unlikely, however, because notwithstanding the change in attribution, the loss suffered by the consignor was quite modest: the krater fetched $3,979 at the first sale and $9,867 at the subsequent sale at Sotheby’s in New York.Footnote 103

Another issue that frequently comes up in this sector involves the lack of incentives to spend time on provenance research, which leads to the information being inconclusive. If provenance statements cannot be corroborated, objects lose appeal, even after changing status to authentic antiquities. This happened with a Roman marble head that sold at Christie’s London in 2005 as part of a lot including four busts, all identified as eighteenth-century pieces complemented by later additions (Table 1, Item no. 9).Footnote 104 The lot sold for $17,822. In 2014, one of these heads resurfaced at Sotheby’s antiquities auction in New York as a Roman antiquity with eighteenth-century additions and with a deceptively more robust provenance history: it did not include new facts but elaborated on information that was already available.Footnote 105 Whereas the prior sale only made reference to the ownership of the McElderay family in Ireland, Sotheby’s elaborated on such prior ownership by explaining that it could have been part of the collection of Frederick Augustus Hervey (1730–1803), the fourth Earl of Bristol, a devoted collector of antiquities who bought several pieces during his trips to Italy. References to his collecting are included in a general book on the antiquities trade in eighteenth-century Rome, but details tying this specific piece to his ownership were missing. The speculative nature of this explanation may have contributed to the relatively low price; appraised at between $10,000 and $15,000, the head was hammered at $10,299. To the contrary, when provenance research reveals verifiable novel information that corroborates the true identification of a piece, the piece will rise to a higher quality rank, and this will be reflected in the sale price. This is the subject of the next subsection.

Returns on Due Diligence Investments for Medium-Quality Objects

Next, we address instances where due diligence is performed to increase the value of the artwork. Such efforts yield a higher payoff if the information is traceable and can be validated externally. According to Figure 1, auction houses are incentivized to perform due diligence and uncover new information when objects are at least of medium quality since market participants are willing to bid higher sums for items that come with a prestigious backstory or more context in general. The performance of due diligence on such objects will also uncover their status as sleepers and that is the reason why most of the sleepers we detected in our database happen to fall in this medium-quality range.

One particularly good example includes a marble portrait bust of a Roman emperor that was sold by Christie’s in London in 2005 (Table 1, Item no. 6) and was described to have been crafted “in Roman Style,” thereby implying that it was not ancient or at least that there was some doubt about it.Footnote 106 Estimated at around $11,500, the object was hammered for just over $275,000. Due to the way art auctions are conducted, such a high price is only obtainable if at least two potential buyers engage in a bidding war; the hammer price is fixed only when the second-to-last bidder drops out. Thus, at least two people in this auction felt the bust was worth much more than its estimate, likely implying that it was an authentic piece. In a way, Christie’s was letting the market decide on authenticity. The provenance descriptors in the 2005 Christie’s catalogue read “Acquired circa 1928 by the owner’s father-in-law in Berlin” without providing any detail on the latter individual.

In 2007, the same lot reappeared at Sotheby’s antiquities auction in New York as a Roman Imperial marble headFootnote 107 and sold for $629,000 (an increase of 2,700 percent), with a much enhanced catalogued provenance. The head was listed as having been auctioned in Munich in 1911 and having been part of the collection of numismatic expert Dr Philipp Lederer around 1938. That same year, the head was published by German archaeologist Anton Hekler and then again in 1942, 1962, 1977, 1981, 1982 by other European archaeologists, and it was also listed in the German ancient objects database Arachne. All of the above information can be fact-checked, and we verified some of the entries. It is clear that, in the two intervening years, Sotheby’s dedicated a great amount of resources to research the provenance of the object in order to confirm its identification, and, as our model predicted, it paid off.

In another instance, the antiquities team at Sotheby's was able to uncover an early prior sale that had been omitted in the previous listing. In 2003, Bonhams’s European Sculpture Department sold the head of a satyr “after the antique” for $10,626 (Table 1, Item no. 7).Footnote 108 No provenance information was reported in the catalogue. In 2011, the same piece sold at Sotheby’s antiquities auction in New York for 12.5 times the prior price after specialists were able to match the object with a 1975 Christie’s sale.Footnote 109 It appeared in that sale without later touch-ups, and it was the highest-selling piece in that auction (for over $3,600).Footnote 110 The prior sale rules out bad faith or implications of illicit trade by providing evidence that the object was outside its country of origin before 1975. Even if it could be argued that experts from a European Sculpture Department should be able to distinguish between antiquities and later imitations, the fact that the head was restored in various points could have been the reason for Bonhams’s misattribution. Ultimately, even if the consignor suffered a substantial loss, a legal claim would not have been available because more than six years had passed between the two sales (the time limitation to start a claim in the United Kingdom). Sotheby’s was rewarded for the remarkable job its team did at retrieving the earlier sale record.

A further example involves an Italian Baroque alabaster vase sold by Sotheby’s at their New York Important French Furniture and Carpets auction in 2009 (Table 1, Item no. 8).Footnote 111 The attractive vase sold for $6,443, and the catalogue did not include any provenance information. It was again consigned with Sotheby’s in 2016 and sold at their antiquities auction in London for £43,750 (7.9 times the first price after inflation) as a first-century Roman alabaster cinerary urn.Footnote 112 In the second sale, the lid and the pedestal had been removed, indicating that the auction house felt that these were later additions and that the ancient attribution applied only to the urn itself. Adding decorative elements to an antiquity was a typical eighteenth-century strategy. If Sotheby’s had suspected that the object was ancient in 2009, it could have marketed it as such the first time around; it was already in New York, so export licenses were not an issue. It follows that the initial misattribution was likely an innocent one, where appraisers in the decorative arts team were unable to distinguish the separate provenances of the components of the objects and thought that, in its togetherness, it was a genuine eighteenth-century piece. Subsequent research unveiled the true identification of the piece, which then sold for almost 10 times the prior sale price.

In contrast to the above examples, and similarly to the bust of the poet discussed above (Table 1, Item no. 9), when the information uncovered by subsequent research cannot be corroborated, the market will likely recognize it and penalize the seller. An example that illustrates this is the sale of a porphyry vase sold by Sotheby’s London in 2008 as part of the estate of industrialist Luigi Koelliker (Table 1, Item no. 11).Footnote 113 It was described as an Italian seventeenth-century object, with no allusion to the fact that it may have been ancient; in fact, the catalogue cites literature discussing similar art from seventeenth-century Florence. It sold for £66,050 ($95,269 in 2017 dollars). In 2011, Christie’s New York listed it as part of its antiquities sale with an estimate of $271,000.Footnote 114 The catalogue made reference to the Koelliker collection but not to its seventeenth-century status, instead explaining that the stone was likely quarried in eastern Egypt and then transported to Rome for sculpting. Provenance entries include new reference to the prior ownership of Madame Petit Cor in Paris in the 1950s, but no information corroborates the ownership or the existence of Madame Petit Cor. The vase did not sell.

It is risky to read too much into an object failing to sell, but it is suggestive that the trustworthiness of the information forms the dividing line between examples of provenance research that made a profit (Table 1, Items nos. 6, 7, and 8) versus research that did not (Table 1, Item no. 11). Read in conjunction with the other examples, the latter one illustrates the difference in public perception between verifiable and shaky provenance information, showing that prospective buyers in the antiquities market are quite discerning and are more likely to pay a premium for well-founded information. This analysis has also shown that properly conducted due diligence has been successful at uncovering sleepers and has yielded substantial rewards to sellers and auction houses, especially when the sale displaying higher returns happened after 2005. The year 2005 marked a key year in the antiquities trade; it is the year that Medici was sentenced to jail and heavily fined for illicitly trading antiquities, following which museums from all over the world who bought from him were forced to return those pieces.Footnote 115 The repatriation wave was considerable and propelled auction houses and other actors in the industry to be much more careful about the provenance of antiquities.Footnote 116

Export Issues

This subsection examines objects that would have encountered export issues if they had been listed as antiquities the first time around. In other words, their sleeper status enabled them to be traded without meeting the import and export criteria set out in national and international legislation. As discussed earlier in this article, it sometimes appears that antiquities are listed as replicas when they are sold in Europe, presumably so that they can bypass the strict export regime that governs their trade in source countries before reaching the New York market, where prices are higher as the supply is limited. Increasing due diligence on these types of objects will lead to more transparency and honesty in the market.

A marble pedestal with the head of Bacchus “in the style of the antique” (Table 1, Item no. 2) sold at Christie’s in Paris as part of an unnamed estate sale for an unexceptional price of just over $5,000.Footnote 117 The sale took place in July 2008. No provenance information was included in the sales catalogue. A mere five months after that sale, the item emerged at a Sotheby’s antiquities auction in New York as a “Blue-Gray Marble Trapezophoros, Roman Imperial, circa 1st Century A.D.”Footnote 118 The reference to Bacchus was dropped, and the Sotheby’s team marketed it as a genuine antiquity without mentioning that it was previously sold as an imitation.Footnote 119 It sold for more than 10 times as much as earlier that year in Paris. The provenance section of the Sotheby’s catalogue asserts that it had belonged to a French collector since the 1920s.

In 2008, the antiquities market was well aware of issues relating to illicit trafficking and import restrictions. Whereas it appears unlikely that the above piece was the product of recent looting, because by that time Sotheby’s New York had implemented fairly strict provenance control mechanisms and had probably verified the 1920s ownership reference, the fact that the object was first sold as a replica enabled it to bypass the strict export requirements to leave Europe. At a minimum, it would have required an export license to be traded. However, utilizing the first sale to validate its wrongful identification, a shrewd buyer was able to flip it (very quickly) so that it could become part of the world’s most exclusive biannual antiquities sale in New York, where only a handful of selected superior quality objects are sold.

In another instance, Sotheby’s London offered a marble head of a satyr from the late fifteenth/early sixteenth centuries as part of its European Sculpture and Works of Art auction in 2008 (Table 1, Item no. 3).Footnote 120 No provenance information was included. It sold for over $12,000. Five years later, Sotheby’s New York offered the same object, but this time identified it as originating in Imperial Rome and including a reference to the prior sale.Footnote 121 The 2013 catalogue explained that the head must have belonged to a European private collection during the eighteenth/nineteenth centuries and grounds this observation in arguments on restoration techniques and patina. It then suggests that the piece made its way to an English private collection in the 1990s. The new attribution and justifications as well as the change in the location of the sale resulted in a mark up: the head sold for 3.2 times the first price.

Both examples suggest that a buyer recognized the true nature of the object and bought it to sell it at a venue where the price would be enhanced, but they also call into question the applicability of export regulations. As noted in earlier in this article, archaeological material located in Europe almost always requires a permit to be traded internationally, whereas later copies valued below a certain threshold do not. The first sales of the above pieces would not have triggered the need to obtain a license if they were indeed later imitations of antiquities, but the later revelation of their true identification would have made this necessary. However, there is also an important difference between these two examples: the long time frame for the resale of the satyr makes malfeasance seem unlikely, whereas the fast turnaround of the Bacchus head points to potential collusive behavior. Even though export crimes can be committed regardless of the state of mind of the tortfeasor, intent to defraud can add depth to a legal claim. The next subsection explores the latter scenario.

Collusive Behavior

The model outlined earlier predicts that incentives to perform due diligence are the highest when the objects are at risk of being the subject of a repatriation claim, thereby requiring the owner to relinquish it to the country of origin without being provided with compensation. As we saw above when objects fall in a higher-value category, buyers become very concerned that the item in question has a solid enough provenance that would help rebut any claim of prior owners. The job of the auction house is therefore to provide as much information as they can to reinforce the object’s history to disprove potential looting issues. The below example illustrates the tensions between uncovering verifiable provenance information, the applicability of export control laws, and the deliberate falsification of attribution by the consignor.