1. Introduction

By what processes do institutions and economies undergo spontaneous, discontinuous change? How does novelty in such systems arise? For well over a century, social theorists have debated two broad explanatory frameworks for these central questions. The first can be loosely characterized as the evolutionary framework, with historical roots in Thorstein Veblen (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2004), an intellectual trajectory through Nelson and Winter (Reference Nelson and Winter1982), and a modern incarnation in the work of ‘generalized Darwinists’ such as Hodgson and Knudsen (Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2006, Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2010), Aldrich et al. (Reference Aldrich, Hodgson, Hull, Knudsen, Mokyr and Vanberg2008) and Stoelhorst (Reference Stoelhorst2008). The second can be loosely characterized as the self-organization framework, with historical roots stretching back to Adam Smith, an intellectual trajectory through Friedrich Hayek and Joseph Schumpeter, and a modern incarnation in the work of figures such as Foster (Reference Foster1997, Reference Foster2000), Witt (Reference Witt1997, Reference Witt2003) and Weise (Reference Weise1996).

In recent years, these two frames have been viewed as in competition, with ongoing debates about the ontological validity and explanatory power of each stance. Geisendorf (Reference Geisendorf2009) surveys and summarizes the modern debate (Reference Geisendorf2009: 377).

As Geisendorf (ibid.) notes, advocates of a ‘universal Darwinism’, such as Hodgson and Knudsen (Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2006), Aldrich et al. (Reference Aldrich, Hodgson, Hull, Knudsen, Mokyr and Vanberg2008) or Stoelhorst (Reference Stoelhorst2008), argue that the mechanisms of variation, selection and retention are general characteristics of open, complex systems, the economy being one among them. Critics, like Witt, disagree and claim that evolution in economic systems is fundamentally different from biological evolution because economic agents are able to change deliberately (Witt, Reference Witt1992, Reference Witt1997, Reference Witt2003). Or they claim, like Foster, that the driving force behind economic evolution is not selection but a self-organized ‘continual, spontaneous generation of novelty’ (Foster, Reference Foster2000: 326), going back to Schumpeter's ideas.

Geisendorf's assessment of this debate is that self-organization is a useful concept, but an incomplete model of institutional and economic change in important respects. The theory ‘helps to understand why there is an endogenously generated incentive to create novelty. And it describes how novelty might spread,’ but ‘the process of novelty generation remains unclear’ (Reference Geisendorf2009: 383). She views universal (or generalized) Darwinism as a more fully specified model, acknowledges that care must be taken to avoid analogizing with biology, and attributes much criticism of the theory to misinterpretation. Crucially, she finds no fundamental ontological contradictions between the two stances. She (Ibid.: 386) cites Klaes's (Reference Klaes2004) four ontological commitments shared by most evolutionary economists: ‘that there is change, that this change is caused, that there is a continuity in this change in the sense that it has to be explained how a state results from the one before, and that it takes place on several, interrelated levels’. She claims that both the generalized Darwinist and self-organization frames rely on these shared ontological commitments.

While Geisendorf sees promise in both approaches, no basic contradictions at an ontological level, and several points of complementarity, she does not attempt to resolve the dispute or integrate the perspectives. This paper will undertake that challenge by introducing a new meta-frame – information theory, and specifically the notion that evolution is a form of computation.

Information theory and related theories of computation are well suited to this task as they cut across both evolution and self-organization. As we will discuss, current evolutionary theory views evolution as a computational process – an algorithmic search through a combinatorial space of possibilities. Likewise, theories of self-organization are rooted in thermodynamics, which to modern physics is just another way of talking about information (and vice versa). Concepts such as complexity, order, emergence and novelty are defined via information theory (Cover and Thomas, Reference Cover and Thomas2008; Davies and Gregersen, Reference Davies and Gregersen2010). One cannot speak about either evolution or self-organization without fundamentally relating back to information.

Such an integrated explanatory framework is important to progress the institutional and evolutionary economics agenda. Neoclassical economics has a framework that, after a fashion, takes into account both evolution and self-organization. From Adam Smith's pin factory, to Marshellian partial equilibrium, von Neumann and Morgenstern's game theory, Arrow–Debreu general equilibrium and Lucas's rational expectations, neoclassical economics has argued that economic self-interest and price signals, mediated by rational agents, lead inexorability to self-organized optimality. And the process by which this self-organized optimality is achieved is the pseudo-evolutionary neoclassical account of market competition. Neoclassically inspired institutional economics shares this integration of self-organization and evolution. For example, transaction-cost economics (Williamson, Reference Williamson2000) is both a theory of self-organization (again, spontaneous cooperation and coordination via rational self-interest and price signals) and (pseudo) evolution via market competition. As Kingston and Caballero (Reference Kingston and Caballero2009: 161) note: ‘the process of institutional change envisaged [by transaction-cost economics] is an evolutionary one in which competitive pressure weeds out inefficient forms of organization, as originally suggested by Alchian (Reference Alchian1950), because those who choose efficient institutions will realize positive profits, and will therefore survive and be imitated’.

Neoclassical theory has continued to dominate economics despite decades of evidence on its empirical failings, its lack of explanatory power, its ontological inconsistencies and even its computational impossibility (for a survey, see Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2006). There are many possible explanations for its persistence (Colander et al., Reference Colander, Goldberg, Haas, Juselius, Kirman, Lux and Sloth2009), but the ability of neoclassical theory to integrate notions of self-organized cooperation and coordination with notions of evolutionary competition under a common analytical framework is arguably a strength. To be credible, any alternative theory must do likewise.

This paper is an attempt to start that integration project. Section 2 reviews the development of the idea of evolution as computation. Section 3 articulates a synthetic account of computational evolution – one can think of it as general Darwinism on a universal computer. Section 4 then applies this abstract account to an economic setting, and section 5 shows how this application might explain patterns of economic and institutional change. Section 6 looks at self-organization from an information theory perspective and shows how it is inextricably bound up with evolution and vice versa. Finally, section 7 argues that if generalized Darwinism is a ‘metatheoretical framework’, as Hodgson and Knudsen (Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2010: viii) claim, then information theory is a meta-metatheoretical framework, providing an ontological grounding for both generalized Darwinism and self-organization as logical consequences of the laws of thermodynamics.

If we can root a theory of economic and institutional change in modern thermodynamics, then we will have significantly sharpened Occam's razor. Neoclassical economics blatantly ignores and contradicts thermodynamics (Georgescu-Roegen, Reference Georgescu-Roegen1971; Mirowski, Reference Mirowski1989; Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2006). As Sir Arthur Eddington (Reference Eddington1927) famously put it, ‘if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation’.

2. Evolution as computation

In his influential 1932 paper, the geneticist Sewall Wright wrestled with the combinatorial problem of a typical genome with 1000 genetic loci with 10 different allelomorphs each, together yielding 101000 possible genetic combinations – a number vastly larger than the estimated number of particles in the universe (Wright, Reference Wright1932). How does the evolutionary process explore such a staggeringly large space of possibility? How does it find within that staggeringly large space the almost infinitesimally small fraction of combinations that could potentially yield coherent, functional designs for organisms? To analyse this problem, Wright proposed a theoretical construct whereby each point in the genetic combinatorial set is assigned a value for its ‘adaptiveness’, as Wright described it. This could then be visualized as a two-dimensional surface, later described as a ‘fitness landscape’ (Dennett, Reference Dennett1995), with peaks and valleys reflecting the environmental fitness of particular genomic combinations. Evolution's job then was to search that landscape for fit genomic combinations.

Initially Wright's paper (Reference Wright1932) was viewed as a modest methodological advance, only later did it come to be appreciated as a major reconception of what evolution is and does. By framing evolution as a process of search through a combinatorial space of possibilities, Wright put evolution into a realm very familiar to mathematicians and, later, computer scientists. To these researchers, the problem of evolutionary search across a fitness landscape looked like a form of optimization problem, where evolution was a process of search for maxima in a dynamically changing, high-dimensional space. Mathematically, the fitness landscape problem shared features with various kinds of multi-dimension function optimization problems, and combinatorial optimization problems (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman1993; Flake, Reference Flake1998).

These similarities were not merely coincidental, as all of these problems either are, or have the potential to be, what mathematicians call NP-complete or NP-hard problems (Karp, Reference Karp, Miller and Thatcher1972) – that is, the time it takes any known algorithm to find a solution to the problem or locate a global optima rises rapidly with the size of the problem. The classic example is the Hamilton path or travelling salesman problem where the challenge is to find the shortest itinerary for a salesman travelling through n cities, stopping in each city once, and beginning and ending in the same city. A five-city tour has 12 possible solutions, a 10-city tour has 181,440 possible solutions, and a 15-city tour 4.36 × 1010 solutions. Thus Wright's paper put evolution in the same mathematical family as these difficult search problems.

This led to attempts to use computers to perform evolutionary searches by algorithm, and De Jong (Reference De Jong2006) cites Friedman (Reference Friedman1956) and Friedberg (Reference Friedberg1959) as the two earliest instances of evolutionary computation. This then led to pioneering work in the 1960s and 1970s by figures such as Rechenberg (Reference Rechenberg1965), Fogel et al. (Reference Fogel, Owens and Walsh1966) and Holland (Reference Holland1962, Reference Holland and Tou1967, Reference Holland1975), and the birth of the field of evolutionary computation. A broad literature developed on genetic algorithms, genetic programming, artificial life and related methods, with applications ranging from communications routing, to circuit design, drug design, stock picking, machine learning and artificial intelligence (for examples, see Koza, Reference Koza1992; Levy, Reference Levy1992; Whitley, Reference Whitley1993; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1996; De Jong, Reference De Jong2006).

Within this literature, Darwinian approaches to evolution were simulated and analysed, but viewed merely as one branch of a family tree of possible search algorithms that also included simulated annealing, various hill-climbing approaches and a wide variety of genetic algorithms. These can be considered mathematical ‘cousins’ to Darwinian evolution. For example, simulated annealing (Stolarz, Reference Stolarz1992) is inspired by the techniques of controlled heating and cooling used by metallurgists to strengthen metals (samurai swords were famous for their use of this technique). The problem is to look for a stable energy state (an energy minimum) in a large combinatorial space of possible energy states. Imagine a ball rolling on a table full of pockets and depressions of varying depth corresponding to energy states. Raising the temperature corresponds to shaking the table, randomizing the location of the ball – violent shaking will keep the ball out of the pockets, flying around the surface in a high-energy state. Cooling, or slowing the shaking, enables the ball to settle into a pocket, though if it is shallow it may get bounced out again. If one cools too fast, e.g., just stops shaking, the ball may get stuck in a locally high energy state. Thus the challenge is to devise a cooling schedule that maximizes the chances of the system finding a stable low-energy minimum. While different from Darwinian variation, selection and retention, simulated annealing in its mathematical characteristics shares many common features.

Initially the field was concerned with developing algorithms and programming techniques ‘inspired’ by biological evolution for the purposes of finding good solutions to difficult search and optimization problems. But another branch of the field began to consider the possibility that if evolution was able to be simulated on computers, then, in a deep sense, following the work of Alan Turing (Reference Turing1936), evolution itself was a form of computation. Holland's (Reference Holland1975) book provided a formal framework for generalizing a computational view of evolution across both natural and artificial systems.

In the 1980s and 1990s the computational view of evolution began to be connected with emerging work on complex systems and self-organization (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman1993), with fundamental work on dissipative thermodynamic systems by figures such as Erwin Schrödenger (Reference Safarzynska and van den Bergh1944) and Ilya Prigogine (1967), as well as Von Neuman's (Reference Von Neumann and Burks1966) work on self-replicating systems and cellular automata, and the physics of information (Percus et al., Reference Percus, Istrate and Moore2006; Bais and Farmer, Reference Bais, Farmer, Adriaans and Benthem2008). This led to a further interpretation of evolution as a bootstrapping algorithm that uses free energy to create order in complex systems. In other words, evolution could be viewed as both shaped by forces of self-organization, and as a process for creating self-organization – something we will return to in section 6.

Over the past decade, this computational perspective began to link with mathematical work on the dynamics of evolutionary systems and the modern neo-Darwinian synthesis, to create an abstract theoretic, computational and analytic framework that in the 1980s and 1990s began to be applied back to biological evolutionary systems. Landweber and Winfree (Reference Landweber and Winfree2002), Crutchfield and Schuster (Reference Crutchfield and Schuster2003) and Nowak (Reference Nowak2006) provide examples of applications of evolution as computation in natural systems. This work has led to productive insights on topics ranging from macroevolutionary dynamics, to speciation, mutation, punctuated equilibrium, evolutionary drift, genome architecture, and even attempts at predictive biology.

Computational approaches to evolution have also had some impact on the study of socio-economic systems, primarily through the use of genetic algorithms as a method for simulating agent behavior and strategy search. Genetic algorithms were first applied in this context in the late 1980s by Brian Arthur, John Holland and their collaborators with the ‘Santa Fe Artificial Stock Market’ (Arthur, Reference Arthur1995; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Durlauf and Lane1997). Since then, genetic algorithms have been applied in a wide number of agent-based models (e.g., Epstein, Reference Epstein2006; Tesfatsion and Judd, Reference Tesfatsion and Judd2006), game theory models (Lindgren and Nordahl, Reference Lindgren and Nordahl1994) and other economic applications such as data mining for finance (Bauer, Reference Bauer1994). As Geisendorf (Reference Geisendorf2009) notes, however, there has been some criticism of these applications for disregarding the particularities of economic evolution.

While this work has been methodologically interesting, there has been no general attempt to apply computational theories of evolution to theories and ontologies of economic and institutional evolution. Searches of the main journals publishing evolutionary economic and institutional work yielded very few hits for foundational citations in the evolution as computation literature (e.g., Holland, Reference Holland1975), and likewise very few hits for terms such as ‘evolution + computation’ and ‘evolution + algorithm’, and those found generally addressed the use of computational techniques in modeling (e.g., Safarzynska and Bergh, Reference Safarzynska and van den Bergh2010) and not the theoretical or ontological implications.Footnote 1 Frenken (Reference Frenken2006a, Reference Frenken2006b) explores the implications of evolution as computation for technology evolution and addresses organizational evolution, but does not attempt a broader link to theories of economic evolution. Potts's (Reference Potts2000) work on microeconomic foundations of evolutionary economics touches on many of the themes raised by evolution and computation, in particular the evolution of complexity, and cites some of the literature, but he does not frame his theory in computational terms. Nor do recent survey volumes (e.g., Hanappi and Elsner, Reference Hanappi and Elsner2008; Witt, Reference Witt2008) grapple with this perspective. Sections 3 and 4 will attempt to fill that gap.

3. Algorithmic evolutionary search and the creation of order

The evolution as computation view starts with neither biology, nor a broad view of biology and culture. Rather, it starts with a perspective that evolution is a form of computation. We can begin with the notion that evolutionary processes are algorithmic processes, an idea that is by now well established in both evolutionary and computational theory (Holland, Reference Holland1975; Dennett, Reference Dennett1995; Landweber and Winfree, Reference Landweber and Winfree2002).

Evolution as algorithm

An algorithm can be defined as a process that takes some set of inputs, manipulates those inputs in a sequence of steps according to a set of rules, and then produces a set of outputs. A baking recipe, for example, fits this definition (e.g., input flour, eggs, butter, sugar, baking powder; stir together well; bake at 175°C for 30 minutes; allow to cool; then output one cake). Dennett (Reference Dennett1995) uses the example of a tennis tournament where one inputs players, grinds them through a set of rules for advancing to quarter-finals, semi-finals, etc, and then outputs a result: the winner. But as Dennett notes, a tournament process is a fairly generic kind of algorithm; it can be used equally well for golf, soccer or tiddlywinks, as it can for tennis. Dennett refers to such algorithms as ‘substrate-neutral’ as the algorithm can run in a variety of environments and operate on a variety of types of inputs – what defines the algorithm is the rule-set inside it, not the particular substrate it works on. A computer software program is an example of a substrate-neutral algorithm.

The link to computation comes from the pioneering work of Alan Turing (Reference Turing1936) who formally defined algorithms and the notion of a ‘universal computer’ (sometimes referred to as a ‘Turing machine’). In essence Turing created a general theory of computation that does not need to run on what we conventionally think of as a computer. While in practice it may be difficult to get Microsoft Word to run on anything other than your laptop (and sometimes that itself is difficult), it is not impossible – for example, in the 1980s a group of students at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) built a digital computer out of Tinkertoys that played tic-tac-toe, though it was the size of several refrigerators and not very fast. It has also been shown that biological DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is a substrate that computes in a literal, Turing sense. Adleman (Reference Adleman1994) is the first example of an experiment where DNA molecules were artificially ‘programmed’ to compute, solving a seven-city Hamilton path problem and doing so extremely efficiently.

One can likewise think of biological evolution as a computational algorithmic process that runs on the substrate of DNA and the other chemical machinery of biological organisms, but evolution itself is a more general substrate-neutral algorithm. Indeed, much of the computational evolution literature cited explores the computational properties of evolution abstracted from its biological instantiation (e.g., Holland, Reference Holland1975; Koza, Reference Koza1992; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1996; Landweber and Winfree, Reference Landweber and Winfree2002; Crutchfield and Schuster, Reference Crutchfield and Schuster2003; Nowak, Reference Nowak2006).

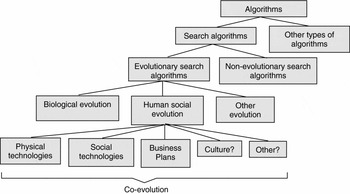

If we thus classify evolution as a member of the general-class of algorithms that can run on any Turing machine, it then follows to ask what kind of algorithm it is (see Figure 1). There are many kinds of algorithmic processes – optimization algorithms, compression algorithms, error-correction algorithms and so on. Following Wright (Reference Wright1932) and the subsequent literature, evolution can be characterized as a form of search algorithm that recursively explores a combinatorial problem space, seeking out solutions that are more fit than others according to some notion of fitness (a concept we will return to). Evolution is not the only form of search algorithm (e.g., matching routines for searching databases), nor is it the only algorithm that iteratively searches combinatorial problem spaces across a fitness surface (e.g., hill-climbing or, as previously noted, simulated annealing algorithms). Rather we can identify it as a particular form of search algorithm that uses the Darwinian operators of variation, selection and retention to search a design or problem space as discussed in the next section.

Figure 1. Evolution classified as an algorithm

Searching design space

What distinguishes evolutionary algorithms from other search algorithms are the characteristics of the problem space that they search, and the method by which they search them. Dennett (Reference Dennett1995) characterizes evolution as an algorithm suited for finding ‘fit designs’. A ‘design’ has a purpose, e.g., the purpose of the design for a chair is to comfortably support a human being in a sitting position. One can also think of a design as solving a problem, e.g., the design of an Eames chair is a candidate solution to the problem of comfortably supporting a human in a sitting position. As long as there is a variety of candidate designs, some designs will inevitably be more ‘fit for purpose’ or ‘solve the problem better’ than other designs. An Eames chair might, for example, be perceived by a user as more comfortable and more attractive than an alternative chair design and thus more fit for purpose and a better solution to the sitting problem. While the purpose of human designs is then to fulfill human needs (Georgescu-Roegen, Reference Georgescu-Roegen1971), the purpose of designs created by biological evolution is simple – to survive and reproduce in their environment. There is a near-infinite variety of possible designs that fulfill this purpose, ranging from a bacterium to an elephant. But, as Dawkins (Reference Dawkins1976) points out, any biological design that did not fulfill this purpose would by definition disappear. Another way to think of it is that a tree frog is a candidate solution to the problem of surviving and reproducing in its particular environment, and its very existence is ipso facto proof that it was a successful solution to that problem at a point in time.

For any design there are variants of that design that may be better or worse at fulfilling the design's purpose or solving the problem. What constitutes ‘better or worse’ is referred to as the fitness function and may contain any number of dimensions. For example, the fitness function for the design of a chair might include dimensions of comfort, attractiveness, cost, durability and so on, while the fitness dimensions of a tree frog might include metabolic efficiency, hopping distance, effectiveness of camouflage and so on. The source of the fitness function is the environment into which the design is physically rendered. A design variant for a tree frog might be rendered into a rainforest environment of food sources, predators, habitats, etc that shape its fitness function. A design variant for a chair might be rendered into an environment of people sitting on it, deciding whether they like it or not, whether to buy it or not, whether to use it or not, and so on. Fitness functions are dynamic and change over time as the environment changes, and there is dynamic feedback or co-evolution between designs and the fitness function generated by their environment.

In the computational conception of evolution it is important to conceptually separate the design of a thing from the thing itself – what Dopfer and Potts (Reference Dopfer and Potts2004) call the first axiom of evolutionary realism: ‘all existences are bimodal matter–energy actualizations of ideas’. A design exists as information while a rendering of the design exists in a physical environment. For example, the information for the design of a chair might be captured in a blueprint and a set of instructions for making the chair – such encoding of design information can be referred to as a schema (Holland, Reference Holland1975, Reference Holland1995; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1996). A chair itself is then a physical rendering of the design encapsulated by the schema. And while all physically rendered designs are actualizations of ideas, it does not follow that all ideas or possible schemata are or can be actualized. The set of chair designs that can possibly be physically rendered under the laws of physics is a subset of the set of all possible chair designs. The set of physical instantiations of chair designs that will ever be rendered in the lifetime of the universe is then a further subset of that. This definition applies not just to artefacts but to other forms of design as well. The design for a shiatsu massage can be encoded in a set of instructions and then rendered by someone providing such a massage. We can even make this separation between schemata and physical rendering for things that are purely information themselves. For example, one can create a schema for a possible computer code, but until it is run on some sort of Turing machine (which is subject to the laws of thermodynamics) it cannot be considered to be physically rendered.

The physical rendering of a design into an environment is sometimes referred to as an interactor (Hull, Reference Hull1988). It is the physical rendering of the design that interacts with the environment and is subject to fitness pressures, not the design itself (though this is not to imply that the unit of selection is the interactor itself; units of selection tend to be modules of design within schemata). Interactors can be composed of matter and energy (e.g., an organism in biology) or can be information themselves (e.g., in a genetic algorithm the schema may code for a bit string that is then subject to selection pressures – this is a physical rendering as well because the computational operations require energy).

The process of translating from the information world of design encoded in schemata into the physical world of interactors is an often-overlooked aspect of evolution. It is not a feature typically highlighted in discussions of general Darwinism, though Hodgson and Knudsen (Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2010: 122) include a ‘generative replicator’ in their scheme that fulfills a similar function. The process of translating from information to reality shapes important characteristics of the process. In order for a design to be rendered there must be a schema-reader/interactor-builder to do the rendering (for simplicity I will refer to this concept as a reader/builder). In the biological world, for mammals the reader/builder is a female womb, for birds, fish and amphibians it is an egg – both render from the schema of DNA into an interactor organism. For a chair the reader/builder might be a carpenter, for a shiatsu massage it might be a masseuse. The need for a reader/builder has two important implications.

First, the schema does not have to capture all of the information in the design, only enough so that the design can be reliably rendered by the reader/builder. The design for a chair has to only be detailed enough for a qualified carpenter with the right tools and materials to build it. The design for a mouse encoded in mouse DNA only has to be sufficient to be rendered by a female mouse womb into a baby mouse. This implies significant knowledge and design in the reader/builder, and one can then ask where this knowledge and design comes from. The answer of course is that reader/builders are the result of evolutionary processes themselves. In biology, schemata code for interactors that also serve as reader/builders (the reading and building is part of the design), giving biological evolution its bootstrapping character. In other substrates, the reader/builder may be the product of multiple evolutionary processes, e.g., the carpenter's ability to serve as a reader/builder for chairs may be the product of evolution across biological, technological and social substrates. We will discuss the role of reader/builders in economic, technological and social substrates further in section 4.

Second, as reader/builders must exist in the physical world, they are subject to physical constraints. This means, as mentioned previously, that there are designs that cannot be built. There are chair designs that violate the laws of physics, or cannot be built with the knowledge and technology of the reader/builder that exist at a point in time. Likewise, there are DNA variants for a mouse that cannot be built and will be miscarried by the female mouse's womb. This means that while the space of renderable chair and mouse designs may be astronomically large, it is nonetheless finite (Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2006: 233–235). The bounds of this finite space may change over time, however. As technology changes, the space of possible chair designs that the carpenter can render may also change. As the designs for female mice evolve, what their wombs can and cannot render will also shift.Footnote 2

The total set of renderable designs can be referred to as a ‘design space’. The size of a design space depends on two factors: the number of modules or dimensions that the design can be varied on, and the number of possible variants for each of those modules or dimensions. Design tends to be characterized by modularity (Holland, Reference Holland1995; Arthur, Reference Arthur2009) with modules, sub-modules and sub-sub modules. For example, a chair has arms, and the arms in turn might be made of various pieces of wood, metal or material. The number of possible variants of a design rises exponentially with the number of modules, sub-modules, etc and the number of possible variants on each of those components. Thus the number of possible variants of even a simple design tends to be very large. For designs of even modest complexity the number of possible designs, though finite, exceeds the number of particles in the universe (Dennett, Reference Dennett1995). Thus, for most design spaces, only a very small subset of possible designs will ever be rendered. The number of chairs ever built will be infinitesimally small versus the number of possibilities.

What the algorithm of evolution is particularly good at is searching such almost-infinite spaces of possible designs for designs that are fit for their purpose. The operation of the algorithm in this search process is remarkably simple – it is the familiar Darwinian mechanism of variation, selection and retention. A mechanism exists for creating a set of variants on a design and those variants are rendered into physical interactors by reader/builders. The interactors interact with their environment (which includes other interactors), and in the course of those interactions, are subject to selection pressures from the fitness function. There then exists a mechanism for increasing the probability that designs with relatively higher fitness are rendered, and decreasing the probability that designs with relatively lower fitness are rendered. The frequency of relatively fitter designs thus increases in the population of interactors, or alternatively, the share of matter and energy devoted to relatively fitter designs increases (Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2006: 291).

What the evolutionary algorithm is doing in this process is iteratively sampling sub-sets of design space in a search for relatively fit designs. Mathematically it can be shown that the evolutionary algorithm is particularly good at this sampling process, and adept at finding fit designs in design spaces where the fitness function is rough-correlated (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman1993, Reference Kauffman1995: 161–189). A fitness function is rough-correlated if small variations from high-fitness designs are also likely to have high fitness, and small variations of low-fitness designs are also likely to have low fitness. If there were a perfect correlation between fitness and variation distance, the design space would have a single global optimum and a simple hill-climbing algorithm would find that optimum more efficiently than an evolutionary algorithm. In contrast, if there were no correlation, the relationship between fitness and design would be random, and a simple random sampling of the space would outperform evolution. A design space with a rough-correlated fitness function is most effectively searched by a mixture of variation sizes across the dimensions of the fitness function – applying small variations on dimensions where there is high fitness (preserving and fine tuning successful design features), but occasionally introducing larger variations to prevent getting stuck on local optima, and applying still larger variations where fitness is low (if a design feature is not working, try something else). A remarkable characteristic of the evolutionary process is that it self-tunes to the shape of a rough-correlated fitness function to find an effective mix of variation distance. This property of evolution is explored mathematically by Kauffman (Reference Kauffman1993) in his N-K model, and by Holland (Reference Holland1975, Reference Holland1995) in the two-armed bandit problem (for a discussion and proof of the two-armed bandit problem, see Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1996: 117–125).

More recent explorations of the mathematical properties of fitness landscapes have yielded some intriguing insights. For example, Crutchfield and Schuster (Reference Crutchfield and Schuster2003: 101–134) attempt to explain key macro features of evolutionary processes, such as metastability, drift, neutral evolution, punctuated equilibrium and epochal change. He shows how topological features of high-dimensional fitness landscapes such as sub-basins of attraction and ‘portals’ (structures connecting sub-basins) may explain these stylized facts.

How evolutionary search creates order

With evolution viewed as a form of substrate-neutral search algorithm we can then move on to another key point raised by the evolution as computation view – evolutionary algorithms are recipes for creating order from disorder, and complexity from simplicity. They are themselves a force for self-organization. One of the most striking empirical features of both the biosphere and human society is that each has generated growing order and complexity over time. The arc of biological history extends from the first single-celled prokaryotes to the massive complexity and variety of the Earth's biota today. Likewise, the arc of human history is one of increasing technological and social order and complexity. Human technology has evolved from stone tools to spacecraft, and human institutions from hunter–gatherer troupes to multinational corporations. One measure of this increase in order and complexity is the variety of products and services in the economy. Beinhocker (Reference Beinhocker2006: 8–9) estimates that the number of unique products and services in the economy has grown from the order of 102 circa 15,000 years ago to 1010 today – a number higher than many estimates of biological species variety. The increase in order and complexity in both biological and human social systems has not occurred monotonically (i.e. the biosphere has experienced mass extinctions, and human civilizations have collapsed as well as grown), but that it has occurred is beyond doubt.

Mainstream neoclassical economics has largely ignored the obvious empirical fact of increasing technological, social and economic complexity and offers little explanation for it (even so-called endogenous theories of growth, e.g., Romer, Reference Romer1990, locate the process for variety creation outside of economic theory). But a variety of scholars from other traditions have addressed this fact in various ways. Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1934) locates the source of novelty and order creation in the acts of the entrepreneur. Hayek wrestled with the question of economic order (Reference Hayek1948) and eventually came to explanations of self-organization and evolution (Reference Hayek1960, Reference Hayek1973, Reference Hayek1988). However, the two social scientists who have come closest to the evolution as computation perspective on this question are Simon (Reference Simon1996) who examined order in both human artefacts and social structures and proposed an evolutionary process in the interaction of human cognition with the environment as an explanation, and Georgescu-Roegen (Reference Georgescu-Roegen1971) who saw the working of an evolutionary algorithm as the only possible explanation for the observed increase in order in the economic system.

Georgescu-Roegen's fundamental insight that ‘the economic process materially consists of the transformation of high entropy to low entropy’ fits very well with modern understandings of order and evolution. In modern physics, entropy and information are viewed as two sides of the same coin (Haken, Reference Haken2000; Bais and Farmer, Reference Bais, Farmer, Adriaans and Benthem2008). As the evolutionary algorithm does its work it reduces informational entropy as it discovers more complex designs over time in the design space, and reduces physical entropy as it uses that information to order matter and energy as the reader/builder renders the design. Evolutionary theorists point out that evolution does not have a direction, but it does have a tendency. As environmental niches fill up and competition increases in a world where resources are finite at any particular point in time, there is pressure to search new regions of design space, and new regions of design space are opened up by the recombination of modules into new systems (which then become sub-systems for larger systems) and additions of new functions, thus creating designs of growing complexity (Holland, Reference Holland1995; Arthur, Reference Arthur2009). Again, the process is not monotonic, and as niches collapse there can also be a collapse back towards favoring simpler designs, but the process of niche construction tends to drive the appearance of designs of increasing complexity. The spontaneous, self-organized reduction in physical and social entropy observed in the economy, and the use of energy inputs and creation of waste outputs in that process, are the hallmarks of an evolutionary algorithm at work – in fact we know of no other process that produces these results.

A generic computational view of evolution

Abstracting from the evolution as computation literature, we can identify the general set of conditions that a system must have for an evolutionary search algorithm to operate. The set of conditions below is from Beinhocker (Reference Beinhocker2006: 213–216) and derived from the computational requirements of evolution; Stoelhorst (Reference Stoelhorst2008) provides an alternative but largely compatible set derived from the requirements of causal logic:

• There must be a ‘design space’ of possible (i.e., physically renderable) designs;

• It is possible to reliably code and store those designs into a schema;

• There exists some form of schema reader/builder that can reliably decode schemata and render them into interactors (schemata may encode for their own reader/builders);

• Interactors are rendered into an environment that places constraints on the interactors (e.g., laws of physics, competition for finite resources); collectively the constraints create a fitness function whereby some interactors are fitter than others;

• Interactors collectively form a population;

• There is a process of schema variation over time; this can be accomplished by any number of operators (e.g., crossover, mutation);

• There is a process of selection acting on the population over time whereby less fit interactors have on average a higher probability of being selected for operations of removal from the population;

• There is a process of retention whereby more fit interactors have on average a higher probability than less fit interactors of being selected for operations of differential replication or amplification versus less fit interactors;

• The combination of these processes operates recursively.

This generic checklist could apply equally well to a genetic algorithm running on a computer, children playing a game evolving designs with Lego blocks (Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2006: 192–198), biological evolution, or as will be discussed in the next section, human social evolution.

4. Evolutionary search in the design spaces of the economy

The next step then is to ask how this generic, computational perspective might map onto the evolutionary processes of human social systems, specifically economic systems. The purpose of presenting this sketch is not to argue that this is the only such possible mapping. Rather, it is to encourage research in this area by demonstrating that such a mapping, however imperfect, is conceptually possible.

Following the generic template described in the previous section we first need a design space or spaces. In the following section I propose that there are three design spaces that are relevant to economic evolution: physical technologies (PTs), social technologies (STs) and business plans. Later in this section will describe how the evolutionary algorithm searches those spaces.

Physical technologies

While the term ‘physical technologies’ is borrowed from Nelson (Reference Nelson2003, Reference Nelson2005) and shares its spirit, I offer my own definition which also builds on the notion of techniques in Mokyr (Reference Mokyr1990, Reference Mokyr2000) and Ziman (Reference Ziman2000): physical technologies are methods and designs for transforming matter, energy and information from one state into another in pursuit of a goal or goals.

PTs are the methods and designs for what we commonly think of as technologies, e.g., ox-drawn ploughs, float glass, microchips. Some PTs result in the creation of an artefact (e.g., a stone hand axe), while others result in the provision of a service (e.g., the methods and designs for a shiatsu massage). PTs are encoded in schemata via natural language, equations, blueprints and diagrams (all of which can be translated to bit strings and thus subject to computational operations) stored in individual minds, documents, computer disks, stone tablets, and so on. These schemata are then rendered by reader/builders into physical artefacts and experiences that then become interactors in their environment (e.g., a design for a bridge is turned into a physical bridge by a team of engineers and builders). The PT schemata do not need to contain complete descriptions of the methods and designs, but rather just enough information to enable a qualified reader/builder to render the design into the physical environment. Thus, an engineer is able to oversee the building of a bridge with the inherently incomplete knowledge contained in blueprints, specifications, in the minds of her colleagues, etc. There is also a process of co-evolution between the schema and the reader/builder – as the engineer experiences more bridge designs her ability to render different parts of the design space will change. This is not unique to human social evolution, as Dennett (Reference Dennett1995) notes and as is discussed in the previous section; in biology, female eggs and wombs (schema-readers) co-evolve with the DNA (schemata) that they read. As with other design spaces, the space of possible PTs is finite at any point in time, but may expand (or shrink) over time as new physical principles are discovered and functionally captured in PTs and variations in currently possible PTs create the potential for newly possible PTs (Arthur, Reference Arthur2009). For example, the capture of physical principles enabled the creation of the laser, variations of which then led to the possibility of the CD player, and then variations of this then led to the possibility of the DVD player.

By defining PTs as methods and designs for a process of state transformation encoded in schemata that are expressible in bit strings, we inherently cast PTs in a computational framework. Algorithms are in essence state-transformation machines.

Social technologies

The second design space is ‘social technologies’. Again, the term and spirit are borrowed from Nelson (Reference Nelson2003, Reference Nelson2005) but it is useful to define the term specifically for our purposes: social technologies are methods and designs for organizing people in pursuit of a goal or goals.

Examples of STs might include a hunting party, just-in-time inventory management, or the M-form organization. STs are related to institutions following North's (Reference North1990) definition of institutions as ‘rules of the game’ but STs are intended to be broader. For example, the STs of a soccer team might include not just the rules of the game, but also the job description of the goalkeeper, the cultural norms of the team, and whether the team fields three strikers at the front or some other configuration. As with PTs we can imagine schemata to encode the methods and designs (e.g., a manual on good soccer team design, strategy diagrams, discussions with experienced players), a larger than the universe design space of all currently possible ST schemata, and a qualified schema-reader (e.g., a soccer coach) to render the design into an interactor (e.g., the soccer team) in the environment.

Once again, the notion of state transformation is inherent to this definition. The notion of ‘organizing people’ has implicit in it the transformation from one state of social interactions, relationships, behaviors and beliefs to another, and a state is deemed more or less ‘organized’ by its fitness for some purpose.

Much of human history can be viewed as a co-evolutionary process between PTs and STs. In both military and scientific history there are numerous examples of innovations in PTs leading to innovations in social organization and vice versa (e.g., new weaponry leading to changes in military organization). In economic history there is also a strong co-evolutionary interplay between PTs and STs. For example the PTs of the Industrial Revolution inspired ST innovations in creating large-scale factories, and financial markets capable of concentrating large amounts of capital, which in turn spurred further innovations in PTs.

Businesses as interactors and business plans as schemata

PTs and STs can encompass designs in pursuit of a wide range of goals, including political, military and religious. If our objective is to explain patterns of economic change, it is then useful to describe a third design space that binds PTs and STs together more narrowly in interactors that pursue specifically economic goals. Under this set-up we can define a ‘business’: a business is a person, or an organized group of people, who transform(s) matter, energy and information from one state into another with the goal of making a profit.

Businesses as defined in this way serve as the interactors in the economic system (Hodgson and Knudsen, Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2006). However, I have used the term ‘business’ rather than Hodgson and Knudsen and others’ use of the term ‘firms’ to allow for the fact that firms may be supersets of businesses in the above definition. We can then think of ‘business plans’ as schemata that code for the designs of businesses, e.g., IBM can be said to have a business plan which codes for the design of its business (similar in spirit to Hannan and Freeman's (Reference Hannan and Freeman1977) ‘organizational blueprint’). Again, a business plan does not have to be a complete description, nor even written down all in one place, as long as a business plan reader/builder (e.g., IBM's management team) can access the necessary information to render the design of IBM into the environment. And as with PT and ST design space we can have a larger than the universe design space of business plans that includes all possible variants on IBM and every other business, and in which some of those variants are fitter than others at a given point in time.

Economic evolution is then a process of co-evolutionary search through these three design spaces. As new PTs and STs are discovered and rendered they are combined and recombined into new business plans which are rendered into businesses, whose activities then change the PT and ST fitness function, leading to changes in the business plan fitness function and so on, creating a co-evolutionary dynamic.

Evolutionary search by deductive tinkering and the role of intentionality

We can then ask how the evolutionary search process proceeds in these three co-evolving design spaces. Building on Campbell's (Reference Campbell1960) and Simon's (Reference Simon1996) work on the role of cognition in human social evolution, one can make a relatively simple proposal. People pursue goals when searching PT, ST and business plan space – a better mousetrap, a better soccer team, or a better IBM. But it is not possible to deductively determine what would constitute a better mousetrap, soccer team or IBM from first principles. The space of possibilities is too vast, the interactors themselves are too complex, their interactions with their environment are too complex, and the fitness function may only be partially known. Human designers searching these design spaces are then left with no choice. They can use their powers of logic and deduction for as far as they will take them, but then at some point they need to try things, tinker and experiment, get feedback from the environment, and try again. There is a significant computational economics literature (e.g., Lewis, Reference Lewis1985; Vellupillai, Reference Vellupillai2005) showing the impossibility of approaching such problems from a purely rational deductive standpoint (which in turn provides a powerful critique of neoclassical theory).

Vincenti's (Reference Vincenti1994) study of the development of retractable aircraft landing gear provides an example where the engineers and manufacturers involved make their best efforts at deductively creating new landing gear designs from scientific and engineering principles, but run into the limits of that approach and also engage in substantial experimentation or tinkering with existing designs. I refer to this process of combining deductive insight with tinkering experimentation as ‘deductive tinkering’. It is the deductive-tinkering process of human designers that provides the source of variation in the three economic design spaces.

The process of deductive tinkering creates options and choices in the design process, for example: ‘Design A when rendered performed very well in the environment, I could try to improve it by making variations B or C.’ Competition amongst designs for finite resources at any point in time then provides selection pressures (e.g., functional performance, consumer preferences, costs), and choices are then made as to where those resources are allocated, thus providing amplification to higher fitness designs and de-amplifying less fit designs, i.e. more fit designs generally get more money, talent, energy, materials, and so on over time. The process of deductive tinkering can occur at multiple levels in the economic system. It can occur in the head of a single individual (e.g., an inventor searching PT space or an entrepreneur searching business plan space), or it can be a group process (e.g., a technology design team, or a management team). It can also include groups arranged across organizational hierarchies (e.g., the regional office generates 10 potential variants on its current business plan, selects three as promising and proposes those to the national office which turns the three into five, proposes them to the global office, etc).

It is important to note that there is nothing in our generic picture of evolution as a form of search algorithm in section 3 that says that the process of variation has to be random, or that the process of search cannot involve foresight or intentionality. The question of the role of intentionality and foresight in human systems, versus the random-blind nature of biological system has long been a point of debate in efforts to incorporate evolution in social theory. Critics of generalized Darwinism argue that human intentionality presents a fundamental problem for attempts to generalize Darwinian evolution (Penrose, Reference Penrose1952; Witt, Reference Witt2004). The evolution as computation view sees no fundamental problem with incorporating human agency. All the evolutionary algorithm requires is some process of variety creation that samples the design space – that sampling process may differ significantly in different domains. Goal seeking, deductive rationality, scientific experimentation, guessing – these are all merely strategies that humans use in the deductive-tinkering process of sampling design space, with some (e.g., science) having a better sampling hit rate than others (e.g., guessing). And again, even with our most effective strategies, it is nonetheless sampling, because finding optimal or even improved designs from first principles is impossible for design problems of even moderate complexity. Thus the computational view interprets human intentionality as just one of any number of possible strategies for sampling design space.

As PTs, STs and business plans are all defined as designs for transformation processes in pursuit of a goal, the process of evolutionary and co-evolutionary search through each design space quite naturally leads to a result of decreasing local entropy. Taking again Vincenti's (Reference Vincenti1994) case of retractable aircraft landing gear, we can see manufacturing such gear as involving the transformation of disordered raw materials through a series of steps into the ordered artefact of landing gear (using energy to go from high entropy to low entropy). The deductive-tinkering search for better landing gear led over time to a progression from simple designs for wheels affixed to wings in the 1920s, to the highly complex and sophisticated retractable landing gear of a modern jumbo jet today. One can say that as the fitness function changed (bigger, heavier, faster planes required different landing gear), it drove the deductive-tinkering process to create new landing gear variants, and select and amplify certain designs based on their performance. The result was landing gear designs that are arguably more ordered and lower entropy today than the design in the 1920s (this can be tested by measuring the length of maximally compressed bit string required to describe each design – or in intuitive terms the blueprints for a 1920s landing gear would be simpler and take fewer pages than the blueprints for modern 777 landing gear). Thus, in the process of evolutionary search through PT, ST and business plan design spaces we can see the potential for local entropy reduction over time.

Finally, it should be noted that certain inventions can have meta-effects on the economic evolutionary process itself. For example, ST inventions such as organized markets, money and double-entry accounting, or PT inventions such as the printing press, telephone or computer, have helped increase the effectiveness and speed of deductive-tinkering evolutionary search.

5. Explaining patterns in the economy

Although the description in the previous section is a bare sketch, one can begin to see how a general computational view of evolution might map onto a theory of economic evolution. Such an exercise holds out the possibility of creating a mathematical or computational model of economic evolution that, because of its relationship to the more general class of evolutionary algorithm, might yield some specific predictions that could be tested (e.g., statistical characteristics of change processes, efforts on system entropy). In principle such a mathematical model or simulation could be developed using the tools of evolutionary computation (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman1993; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1996; Landweber and Winfree, Reference Landweber and Winfree2002; Crutchfield and Schuster, Reference Crutchfield and Schuster2003; Nowak, Reference Nowak2006), the mathematical theory of design (Suh, Reference Suh1990; Braha and Maimon, Reference Braha and Maimon1998) and tools from information theory (e.g., Cover and Thomas, Reference Cover and Thomas2008; Bettencourt, Reference Bettencourt2009). While there is some debate in evolutionary and institutional economics as to the value of more mathematical approaches (Nelson, Reference Nelson2005), one of the historical critiques of evolutionary and institutional economics has been that without a rigorous (i.e. mathematical or computational) articulation of theory, it cannot be tested in the same way that neoclassical theories can be (despite the generally poor performance of neoclassical theory in those tests). This is not to say that an evolution as computation approach to economic evolution would obviate more qualitative, descriptive, case-based and historical approaches – indeed the experience of the study of other complex systems (e.g., biology, climate systems) indicates that the two methods are highly complementary.

Looking ahead one can posit some hypotheses as to how a program of computational–evolutionary research might contribute to institutional economics:

First, computational models of economic evolution might explain the explosive increase in per capita income and product and service variety that resulted from the Industrial Revolution. While the historical narrative of the Industrial Revolution is well known (e.g., Landes, Reference Landes1969; Clark, Reference Clark2007), economics offers no satisfactory endogenous theory of this period of dramatic economic change. Neoclassical theory cannot offer such an explanation, as the Industrial Revolution was a phenomenon of profound disequilibrium. Evolutionary systems, however, can and do undergo such periods of explosive growth in scale, order, variety and complexity. Mathematical and computational explorations of the evolutionary process locate potential causes of such phenomena in the shape and structure of fitness landscapes and dynamics of co-evolutionary interactions (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman1993; Landweber and Winfree, Reference Landweber and Winfree2002; Crutchfield and Schuster, Reference Crutchfield and Schuster2003). In the case of the Industrial Revolution, analysing the co-evolutionary dynamics between PTs and STs would potentially enrich our understanding of the role that institutions played in that transition.

Second, new explanations might be found for the distributional patterns of firms (e.g., revenues, numbers of employees, assets) and patterns of firm performance over time (e.g., entries and exits, growth rates, profitability, returns). Again, mathematical and computational research shows that evolutionary processes tend to produce signature distributional patterns, most notably power laws, and these have been found in relation to distributions of various measures of economic and firm performance (e.g., Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Amaral, Buldyrev, Havlin, Leschhorn, Maass, Salinger and Stanley1996; Amaral, et al., Reference Amaral, Buldyrev, Havlin, Leschhorn, Maass, Salinger, Stanley and Stanley1997, Reference Amaral, Buldyrev, Havlin, Salinger and Stanley1998; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Amaral, Canning, Meyer and Stanley1998). Axtell (Reference Axtell1999, Reference Axtell2001) explores these issues using US census and other data and locates possible explanations in evolutionary dynamics both within firms and between firms. Other researchers have found strong mean regression in firm performance over time, that sustained periods of statistically significant outperformance versus industry mean are rare, suggesting a lack of adaptive behavior at the firm level, and mean industry performance being driven significantly by firm entry and exit (Wiggins and Ruefli, Reference Wiggins and Ruefli2002, Reference Wiggins and Ruefli2005). One hypothesized explanation is a lack of adaptive capacity in firms – industries evolve but firms do not. Epstein (Reference Epstein2006: 309–343), for example, offers a computational–evolutionary model that explores how hierarchical structures and internal trading regimes may have an impact on firm adaptability.

Third, taking evolution seriously also requires one to take the Second Law of Thermodynamics seriously, as evolution, whether social or biological, occurs in a world of physical constraints. The neoclassical production function and theory of the firm is detached from such physical constraints (Daly, Reference Daly1999). The flip side of economic order creation driven by the evolutionary process is finite resource use, waste and pollution, as evidenced by dramatic jumps in all three corresponding with the spread of industrialization. By connecting firms and other institutions to the constraints of the physical world via thermodynamics, an evolution as computation perspective on economic evolution would potentially cause us to rethink the objective functions for those institutions (eventually such physical constraints will become part of the evolutionary fitness function in both economic and biological substrates) and provide normative insights for how we think about issues ranging from global warming, to resource productivity, to how we measure performance in economic and political institutions.

These are merely examples, but they nonetheless illustrate different ways in which the evolution as computation view of evolution might contribute to explaining patterns in institutions and the economy.

6. Self-organization, information and the emergence of novelty

By now it should be clear that there is much self-organizing going on under the evolution as computation perspective. The algorithm captures free energy to search enormous combinatorial spaces in search of fit designs, creating novelty through changes in design modules and recombinations of modules to discover and realize previously unrealized designs. In this way, order and structure are (non-monotonically) created.

However, the Darwinian evolutionary algorithm cannot accomplish this by virtue of its own internal logic alone. It depends on external laws or forces to create the potential for complex structures in a dissipative system. As Kauffman (Reference Kauffman1993) points out, the origin of life depended on the existence of self-organizing principles that were inherent in auto-catalytic chemical cycles to create structures that selection could eventually work on. Cast in computational terms, the evolutionary algorithm is a highly successful bootstrap algorithm that, given some free energy, can bootstrap from low to high order. But it cannot bootstrap from zero order (maximal entropy); it needs somewhere to start.

Once again, an information-theoretic, computational view can provide that starting point. Self-organization can be described equivalently in terms of energy and entropy, or in terms of probability and information (Haken, Reference Haken2000). From an information perspective, self-organization occurs when information is aggregated and becomes more than the sum of its parts (new information is created in the local system – though it is destroyed somewhere else by the heat of the computations involved, so still no free lunch). In the realm of energy and matter the same thing happens when a set of molecules captures free energy to snap together into a structure (entropy is temporarily reduced in the local system). Bettencourt (Reference Bettencourt2009) uses Shannon (Reference Shannon1948) entropy to formally show how the process of information aggregation can inherently self-generate new knowledge. In an environment where there are differentials in the uncertainty of information, and there is mutual independence of that uncertainty, pooling knowledge about Y can decrease or increase our uncertainty about X. Bettencourt calls decreases in uncertainty from pooling ‘synergy’ and increases ‘dysynergy’. He then derives the conditions where aggregation maximizes synergy: ‘The optimal requirement is simply that each contribution is statistically independent from others and that they are not conditionally independent given the state of the target X.’ (Bettencourt, Reference Bettencourt2009: 605)

This result explains the ‘wisdom of crowds’ and creates a fundamental incentive for human social cooperation – in essence there are non-zero sum information gains from cooperation. But, as Bettencourt notes, there is a central tension in the result:

. . . there are two separate ingredients contributing to the possibility of an optimal synergetic strategy: (a) the fact that the information aggregator X does not create conditional independence of the several contributors, which makes synergy possible, and (b) that given the possibility of synergy, each component remains as independent as possible from the others (Ibid.).

This possibility of synergy may then create a general selection pressure in favor of cooperation (and the evolution of higher-order structures). But within that general selection pressure, managing the tension between (a) and (b) creates the potential for differential performance in achieving synergies, and incentives to explore possible designs for information aggregators and different rules for participant interaction. Managing the tension between (a) and (b) is a classic cooperative game problem and a task for ST.

We thus have arising out of a result in information theory a fundamental incentive for self-organized human cooperation, but also an incentive to explore the space of possible designs for differentially capturing the gains from that cooperation. We are thus right back to evolution.

To summarize, from the point of view of information theory and computation, it is almost impossible to talk about evolution without referring to self-organization, and vice versa. Evolution needs self-organization to bootstrap the process of evolutionary search and order creation, while self-organization leads to conditions where the logic of differentiation, selection and retention can take hold. As Hodgson and Knudsen note, ‘Self-organization means that complex structures can emerge without design, but these structures themselves are subject to evolutionary selection.’ (Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2010: 56)

Foster argues for the relevance of self-organization in understanding processes of economic change:

In contrast [to evolution], the self-organization approach to system behavior is founded upon an observable historical process, captured in the entropy law. It deals with non-equilibrium structural change, as found in historical experience, not timeless comparative statics . . . The advantage of the self-organization approach is that it encompasses time irreversibility, structural change and fundamental uncertainty in an analytical framework which can be used in empirical settings . . . A wide range of institutionalist insights can be translated into propositions concerning self-organization (Reference Foster1997: 427).

An information theoretic perspective would say that the statement is true, except for the phrases ‘in contrast to [evolution]. . .’ and ‘the advantage of the self-organization approach. . .’. The statement is equally true of evolution as computation, and separating evolution and self-organization into competing frames merely causes both to lose their explanatory power.

Finally, information theory also provides solid ground on the question of where novelty comes from – a question that Geisendorf (Reference Geisendorf2009) found missing in her survey of self-organization. From an information-theoretic perspective there are two (and only two) sources of novelty in the universe (Vedral, Reference Vedral2010). One is quantum mechanical fluctuations and the other is the recombination of information (though there is an interesting question as to the meaning of novelty in a multiverse interpretation of quantum mechanics). There are debates as to whether quantum fluctuations have effects at the coarse-grained macroscopic level that economies and institutions inhabit, but there is no question that recombination has effects at the macroscopic level. Arthur (Reference Arthur2009) describes in detail a recombinative theory of technology evolution and shows numerous examples. Bettencourt (Reference Bettencourt2009: 598) notes that ‘information is a peculiar quantity’ because the aggregation and recombination of information can produce new information. Unlike matter and energy, it is not a conserved quantity. Vedral (Reference Vedral2010: 5) refers to this as ‘creation ex nihilo: something from nothing’. Novelty clearly comes from the recombinative process of evolutionary search in design space – as noted, evolution creates novelty by ‘discovering’ and rendering previously unrealized designs. But recombination can also occur through the spontaneous processes of self-organization (e.g., a football team spontaneously tries a new formation) feeding variety into the deductive-tinkering process of evolutionary search. Again, it is not a question of whether evolution or self-organization is a better explanation for novelty creation – it is clearly both working in tandem.

7. Ontological implications for generalized Darwinism

Underlying the debate over generalized Darwinism versus self-organization has been deeper questions on the ontological validity of the generalized Darwinian program. Those raising questions fall roughly into four camps: (1) those who advocate a ‘broad’ generalized Darwinism oriented around human cultural evolution (Boyd and Richerson, Reference Boyd and Richerson1985, Reference Boyd and Richerson2005) and with only a passing relationship to biological evolution based on some shared terminology (e.g., Nelson, Reference Nelson2006); (2) those who argue that the use of evolutionary concepts inevitably resorts to inappropriate analogies to biology and propose alternative theories such as self-organization (e.g., Foster, Reference Foster1997); (3) those who argue that evolutionary concepts do apply to human social systems such as the economy, but only as a direct extension of biological evolution – the ‘continuity hypotheses’ (e.g., Witt, Reference Witt2004); and (4) those who contend that the existence of human agency fundamentally invalidates any use of evolutionary theorizing (e.g., Witt, Reference Witt1992).

I will use the evolution as computation perspective to address each criticism in turn. First, Nelson (Reference Nelson2006) is right to be concerned about using biology as a kind of template for human social evolution, or not taking sufficiently into account the specific details of human social systems. I would argue that the evolution as computation perspective can be highly specific to the details of human social systems, and the economic instantiation can differ significantly from the biological instantiation, while at the same time still be rooted in a deeper, universal class of evolutionary phenomenon (evolutionary computation). The model sketched in section 4 is vastly different in detail from biological evolution (there are no genes, species, mutation, inheritance, etc in my account of economic evolution, and no business plan, multi-level selection or deductive tinkering in biological evolution). Yet, according to Figure 1, both are members of a more general class of system. This is ontologically no different from saying that a car's engine and a cow's digestion differ in many specifics, but both are members of a higher-level class of open thermodynamic systems. Any such classification should be empirically testable, and an important part of the evolution as computation agenda should be to devise empirical tests of this classification. Classifying the economy and institutions in this way (assuming such tests were passed) is enormously valuable because it puts a rigorous, logically consistent and, again, potentially testable frame on economics and avoids the ad hoc theorizing and just-so stories that are a risk of so-called ‘broad’ evolutionary economics.

The second critique, biological analogizing, can be viewed as irrelevant because there is no analogy to biology in the computational perspective. Again, the stance is that evolutionary computation is a universal class (and indeed a sub-class of a broader class of search algorithm) and biological evolution and economic evolution are two specific members of that class. By this definition of evolution, the economy is not like an evolutionary system, it is an evolutionary system. Saying this is an analogy makes no more sense than saying that our sun is analogous to a star. We have already addressed the point that self-organization is not an alternative but a critical complement to both economic and biological evolution.

The third critique, the continuity hypothesis (Witt, Reference Witt2003, Reference Witt2004; Cordes, Reference Cordes.2006), takes as its departure that human beings are the result of Darwinian biological evolution, and that this process and the selection pressures it operated under, produced human brains endowed with certain cognitive capabilities and certain genetically influenced behaviors, and extended the pro-sociality of our primate ancestors to new levels of complexity. As that process of social interaction increased in complexity (and was supported by biological evolution of brains, language capabilities, physical capabilities for tool-making, etc), those interactions and the culture that emerged from those interactions began to play an ever-larger role in our survival as a species versus strictly biological considerations. Also, culturally derived and learned behaviors began to increasingly override or modify innate behaviors in many spheres. Major elements of the continuity hypothesis are highly likely to be correct – most notably there is strong evidence for the co-evolutionary interplay over time between genes, morphology, brains, language, behavior, social structures, artefacts and environment, extending from our primate ancestors to modern humans (e.g., Cavalli-Sforza, Reference Cavalli-Sforza2001; Jablonka and Lamb, Reference Jablonka and Lamb2005; Richerson and Boyd, Reference Richerson and Boyd2005).

Examined through the lens of computation, again the continuity hypothesis looks more like a complementary hypothesis than competing explanation. A way to integrate the views is to note that while the generalized Darwinian logic of variation, selection and retention lies at the algorithmic heart of the computational process, the rest of the computational machinery – mechanisms for encoding and decoding schemata, reader/builders, the emergence of a fitness function, the deductive-tinkering process, and so on – requires explanations generating from the continuity hypothesis (in fact, where else could they possibly come from?). The coding of economic schemata (PTs, STs and business plans) relies on the evolution of language. Deductive tinkering is an outcome of our cognitive evolution (and may involve gene–culture interaction as well). Beinhocker (Reference Beinhocker2006: 308–314) postulates a continuity hypothesis between modern economic preferences and the ancestral evolutionary environment (e.g., our preferences for fatty foods, items signaling status, or economically supporting close genetic kin). Such biologically influenced preferences in turn influence the fitness function at work in business plan evolution in the economic system.

Fourth, and finally, the evolution as computation perspective has no problem accommodating human agency. As noted earlier, all that the evolutionary algorithm requires is some mechanism for variety creation to sample the combinatorial space of possibilities. The nature of that process (e.g., directed, random) and the specifics of how it is implemented will certainly affect the performance of that particular system, but it is nonetheless, from a computational perspective, evolutionary. An interesting feature of the human social instantiation is that our sampling mechanisms are often mediated by institutions (e.g., science, marketing, democracy), and thus the sampling mechanisms themselves evolve. For example, the invention of science dramatically upped the hit rate in the deductive-tinkering sampling of PT space. Likewise, the creation of organized markets upped the hit rate in business plan space. One can think of these as STs that have a meta-effect on the evolutionary system itself.